OMNIA Penn

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

Solutions Sound Solutions Sound Solutions Catalysts for Basic Science 24 Seizing the Moment 28 Guardians of the Gallery 46 Online and on Point 36

Arts & Sciences researchers are turning to sound for answers on subjects from birdsong to music exposure. PAGE 16

Sound

OMNIA | ALL THINGS PENN ARTS & SCIENCES 16 COVER STORY Sound Solutions Understanding the world by studying sound Lessons in Philosophy Teaching high schoolers to ponder 42 Addressing Tough Topics A Living the Hard Promise series recap 40 Just Right Four LPS online certificate experiences 36 Seizing the Moment The powerhouse that is Africana studies 28 Catalysts for Basic Science The enduring legacy of the Vageloses 24 Guardians of the Gallery Three alums on working in the art auction world 46 FEATURES

Omnia is published by the School of Arts & Sciences Office of Advancement

EDITORIAL OFFICES

School of Arts & Sciences

University of Pennsylvania

3600 Market Street, Suite 300 Philadelphia, PA 19104-3284

P: 215-746-1232

F: 215-573-2096

E: omnia-penn@sas.upenn.edu

STEVEN J. FLUHARTY

Dean, School of Arts & Sciences

LORAINE TERRELL

Executive Director of Communications

MICHELE W. BERGER

Editor

SUSAN AHLBORN

Associate Editor

JANE CARROLL

Staff Writer

LUSI KLIMENKO

Art Director

LUSI KLIMENKO

DREW NEALIS

KRISTINA PAGGIOLI

Designers

CHANGE OF ADDRESS

Alumni: Visit MyPenn, the Penn alumni community, at mypenn.upenn.edu. Non-alumni: Email Development and Alumni Records at record@ben.dev. upenn.edu or call 215-898-8136. The University of Pennsylvania values diversity and seeks talented students, faculty, and staff from diverse backgrounds. The University of Pennsylvania does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, creed, national or ethnic origin, citizenship status, age, disability, veteran status, or any other legally protected class status in the administration of its admissions, financial aid, educational or athletic programs, or other University-administered programs or in its employment practices. Questions or complaints regarding this policy should be directed to the Executive Director of the Office of Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity Programs, Sansom Place East, 3600 Chestnut Street, Suite 228, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6106; or 215-898-6993 (Voice) or 215-898-7803 (TDD).

2024 12 OMNIA 101

SPRING/SUMMER

On the value of polling in 2024

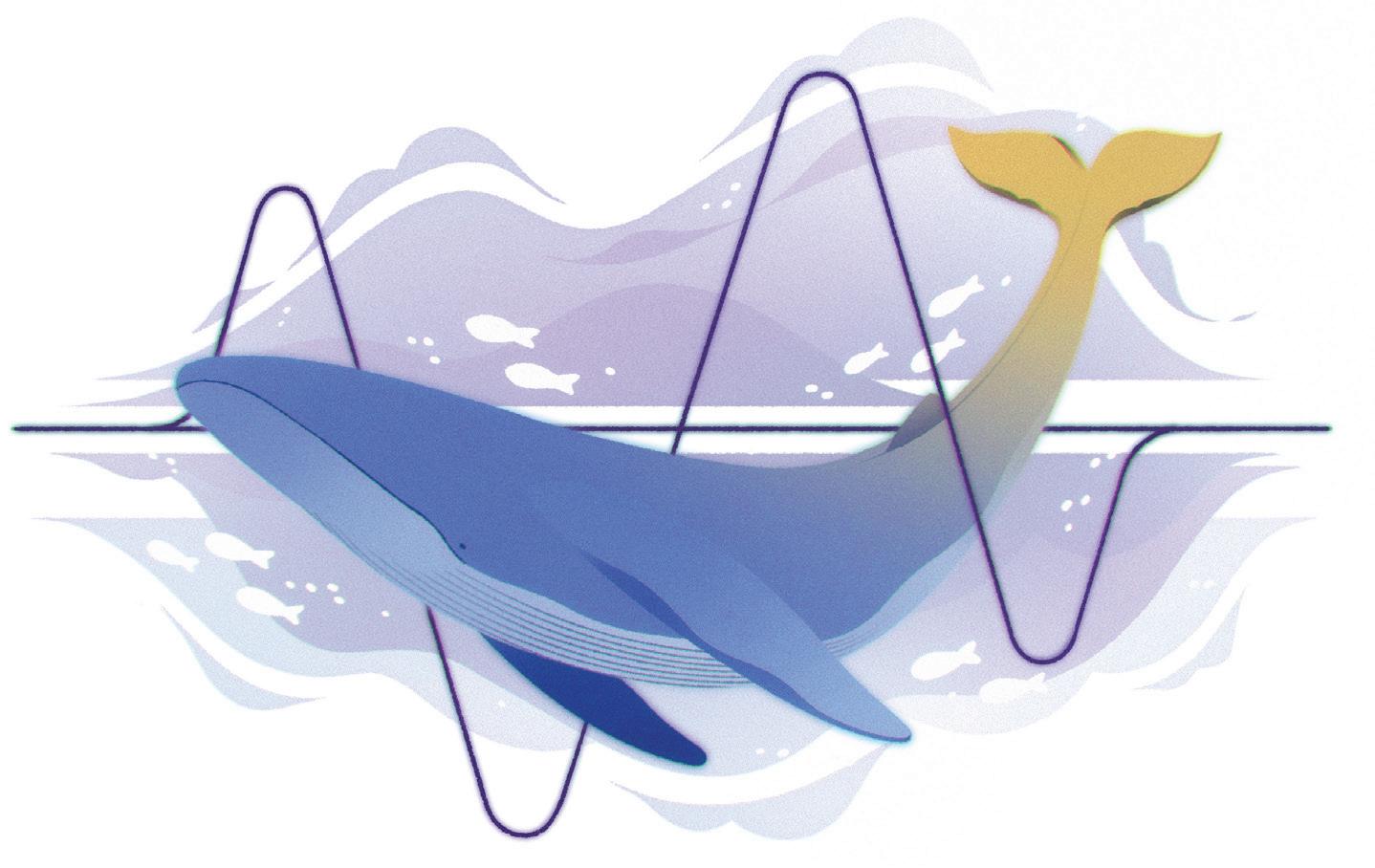

Cover Illustration: MAGGIE CHIANG SPRING/SUMMER 2024 4 SCHOOL NEWS An fMRI machine, awards, more LAST LOOK Translating a Medieval manuscript 65 ORIGIN STORIES The path of professor Ayako Kano 62 ONLINE CONTENT Bonus multimedia content 64 SECTIONS 52 STUDENT SPOTLIGHT Violins, Penn Grad Talks, and more 58 MOVERS AND QUAKERS A College for Women scrapbook 14 IN THE CLASSROOM Learning history via rivers CONTENTS 8 FINDINGS Notable faculty research and books

Affirming Our Purpose

Spring at the School of Arts and Sciences is typically a time of celebration, when my colleagues and I can look back at the year and appreciate the people, projects, and accomplishments that define us as a great institution. This year is no exception: We have achieved much, both individually and as a School. We started 2024 with the announcement of a transformative gift—the largest ever in the School’s history—from P. Roy and Diana Vagelos (p. 24). Their generosity and vision will be shaping the future of science research and education at Penn Arts & Sciences for generations to come.

Our faculty have distinguished themselves through a series of honors, ranging from teaching awards to appointments to prestigious academic societies, even a Pulitzer (p. 7). They continue to produce scholarship that is shaping conversations within and beyond the academy. And our students continue to demonstrate potential that is truly inspiring.

But there is no looking back at the past year without acknowledging the profound impact on our community of the horrific Hamas attack on Israel and the continuing war in Gaza. We witnessed reactions to world events descend on our campus, along with campuses across the country and globally, in a way that has not been seen in more than a generation.

Why have campuses become ground zero for unrest? In no small part, it stems from our commitment to hearing diverse voices, and our conviction that it is the job of institutions of higher learning to uncover truth, even when the questions get hard. We aspire to a high standard of open discourse—a standard that, at times, tests us. But while these conversations are hard, it has never been more clear that opening ourselves to challenging discourse is our greatest strength,

where our ability to advance and create knowledge is rooted.

Our vibrant campus life this spring is a testament to how our community values discourse, in events that brought us together on a range of topics. Our Living the Hard Promise series (p. 40) has continued, including a series of 60-Second Lectures exploring related themes and an Alumni Weekend Hard Promise event featuring Paul Sniegowski and Beth Wenger. An audience of 1,500 people listened to Margaret Atwood’s discussion with Professor Emily Wilson during the annual Stephen A. Levin Family Dean’s Forum (p. 6). Alumni came to hear faculty discuss climate and sustainability at our Ben Talks events in New York and California (p. 57).

In May we closed out this academic year at our School’s three graduation ceremonies—celebrating the accomplishments of nearly 400 graduate students; 500 lifelong learners from the College of Liberal & Professional Studies; and more than 1,300 undergraduates, representing some 50 majors, from the College. Despite a year of hard discussions, we all came together as a community for these celebrations. As we sent our graduates out into a complex world, where there are many difficult questions and few simple answers, we took away with us an affirmation of our purpose and the fundamental importance of our work. I look forward to continuing engagement and discussion with these graduates, with all our alumni, and with the rest of us on campus as we return in fall and begin again.

Steven J. Fluharty, C’79, GR’81, PAR’07, Dean and Thomas S. Gates, Jr. Professor of Psychology, Pharmacology, and Neuroscience

Steven J. Fluharty, C’79, GR’81, Psychology,

OMNIA | ALL THINGS PENN ARTS & SCIENCES

DEAN’S MESSAGE

Lisa J. Godfrey

00FFFFFF 2

Illustration by Kate Miraglia

ITaking Your Feedback to Heart

Omnia and

want to start by thanking the more than 600 of you who responded to our reader survey from the Fall/Winter 2023 issue, providing us with your opinions about thoughts for our future coverage. We’ve taken the feedback to heart, contemplating ways we can incorporate into our storytelling what you’ve told us you want to read.

One request we could tackle immediately was for more pieces about Penn Arts & Sciences alums: In this issue, you’ll see a full Movers & Quakers section, which combines existing features with some new content. It starts on p. 56 with our Penn at Work profile of Sharon Kim, C’05, of the Mount Airy Community Development Corporation. We also showcase several of the events that took place since the fall (p. 57) and include a photo essay highlighting student life in the College of Liberal Arts for Women (p. 58), which merged with what is today’s School of Arts & Sciences 50 years ago. Beyond that, we have a feature, “Guardians of the Gallery” (p. 46), about three alums in the art auction world. They are using their platforms to champion underrepresented artists, start conversations about art and antiquities reparations, and enrich the narrative around objects.

Development Corporation. We also showcase since

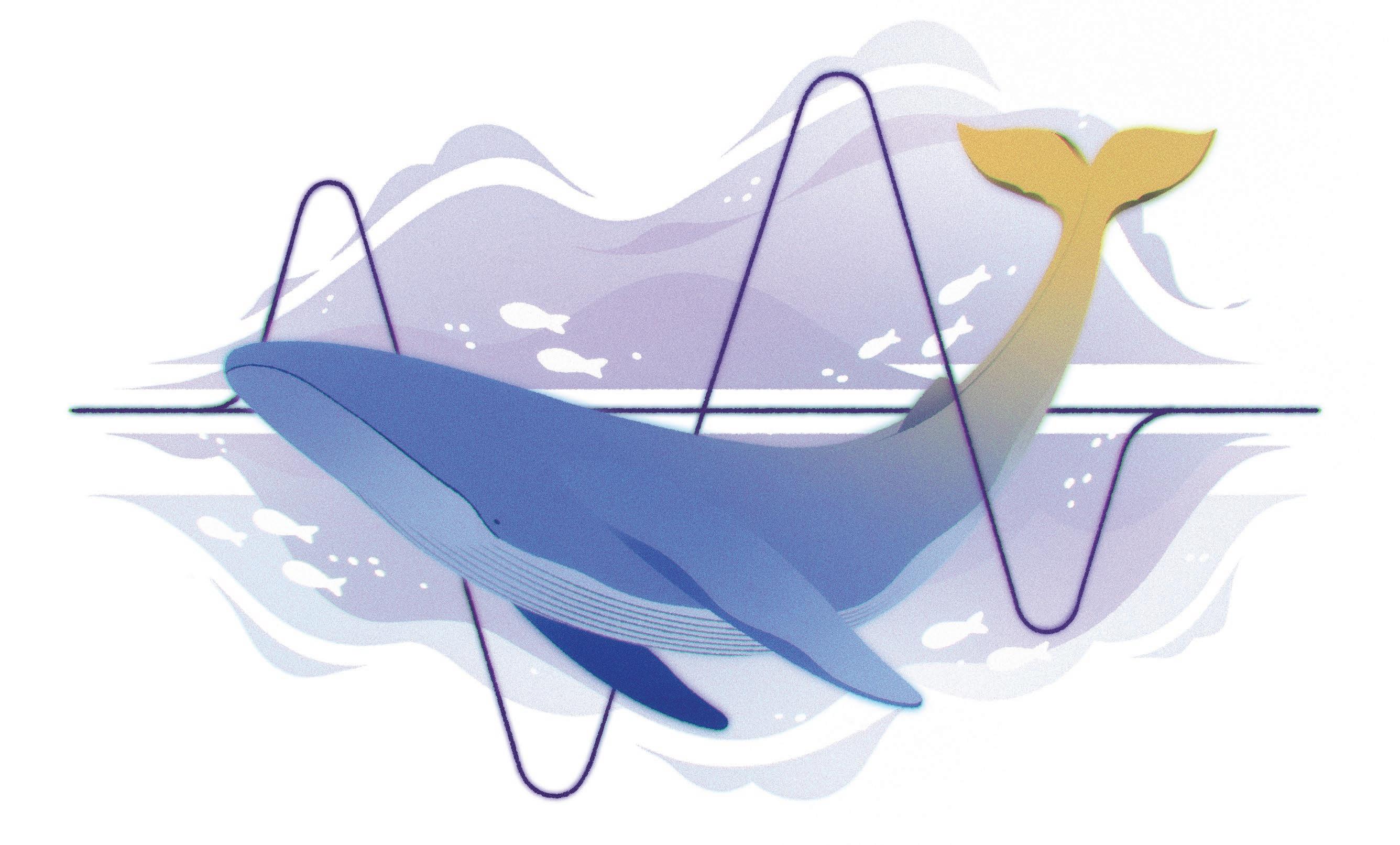

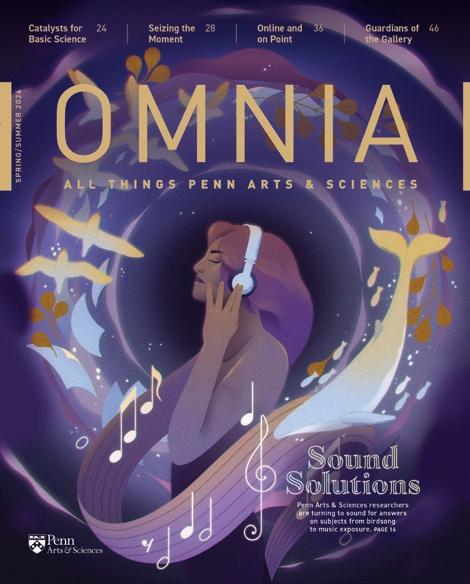

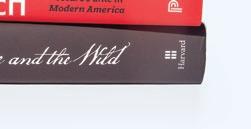

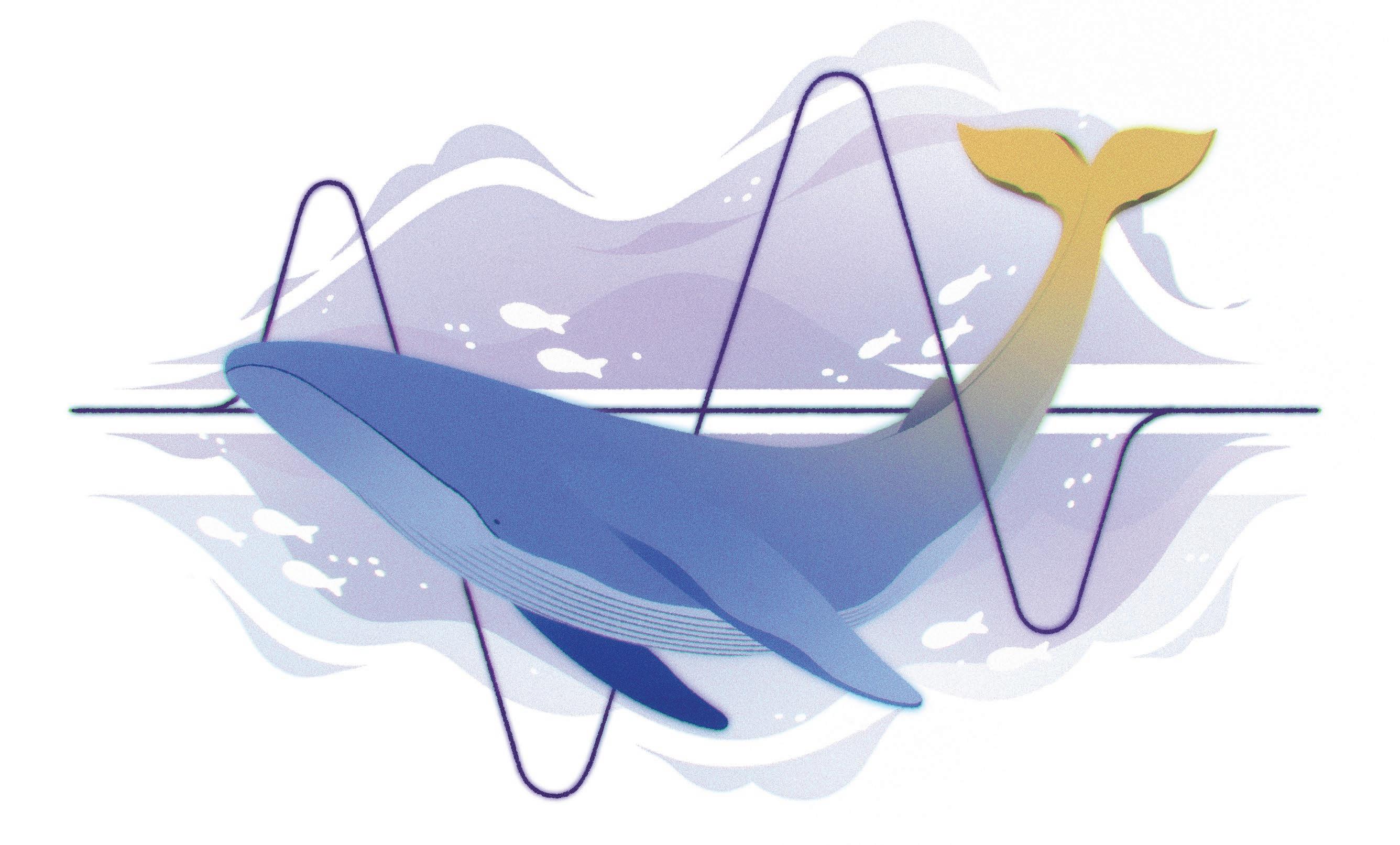

BEHIND THE COVER

Other features in this issue include our cover story, “Sound Solutions” (p. 16), about researchers turning to sound to answer questions on subjects like birdsong or the benefits of music exposure; “Seizing the Moment” (p. 28), which shines a light on Africana studies at Penn and its emergence as a leader in the field; “Addressing Tough Topics” (p. 40) about the Living the Hard Promise series, the chance for frank conversation about subjects like free speech on campuses and the role of universities; and “Just Right” (p. 36), about the certificate program from the College of Liberal & Professional Studies, which has awarded 468 certificates since it began in 2018. Today, 556 students are taking courses in more than a dozen programs. Plus, in “Catalysts for Basic Science” (p. 24) we look back at the contributions of P. Roy Vagelos, C’50, PAR’90, HON’99, and Diana Vagelos, PAR’90, who recently gave Penn Arts & Sciences

$83.9 million to fund science initiatives—the largest single gift ever made to the School.

$83.9 million to fund science initiatives—the

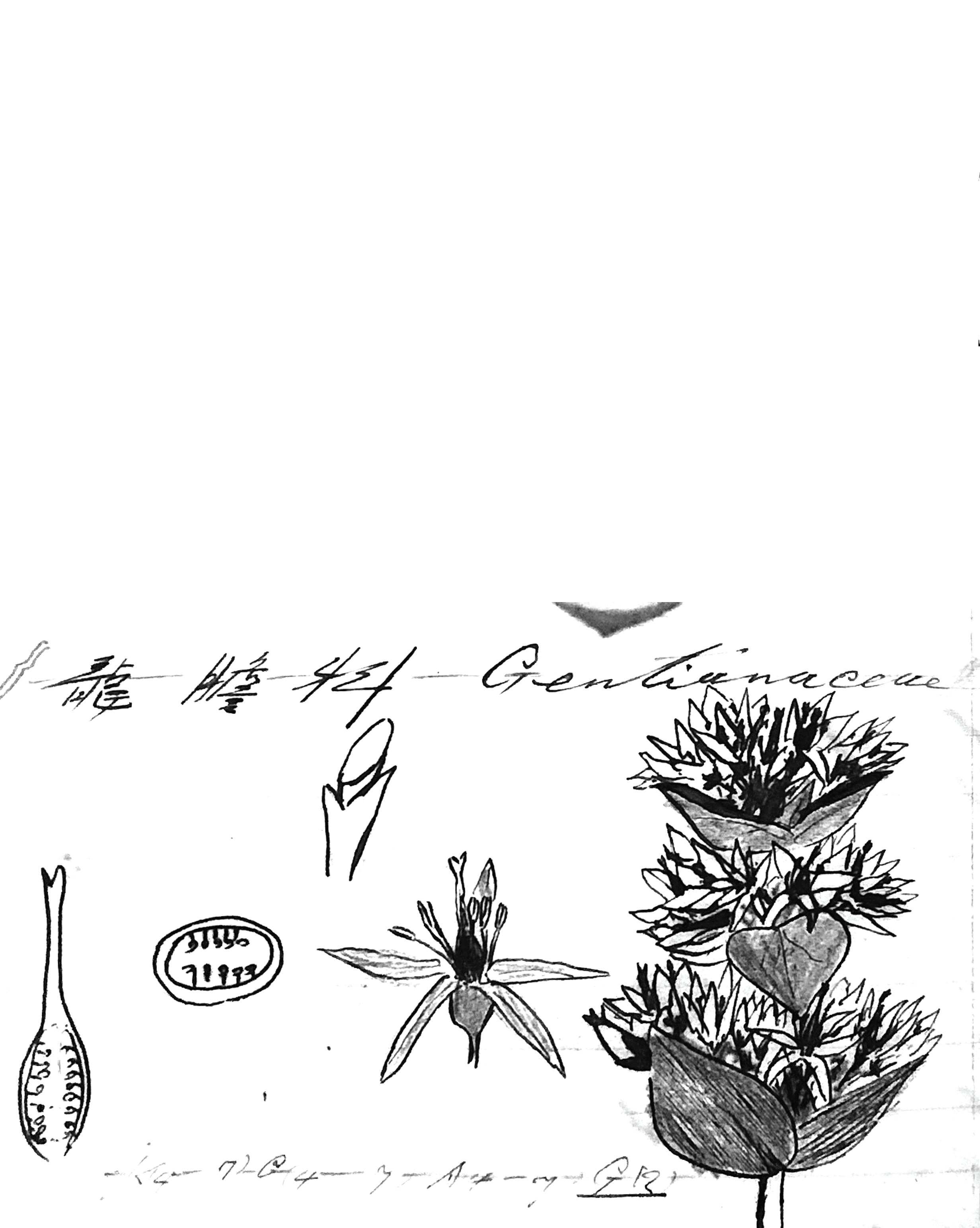

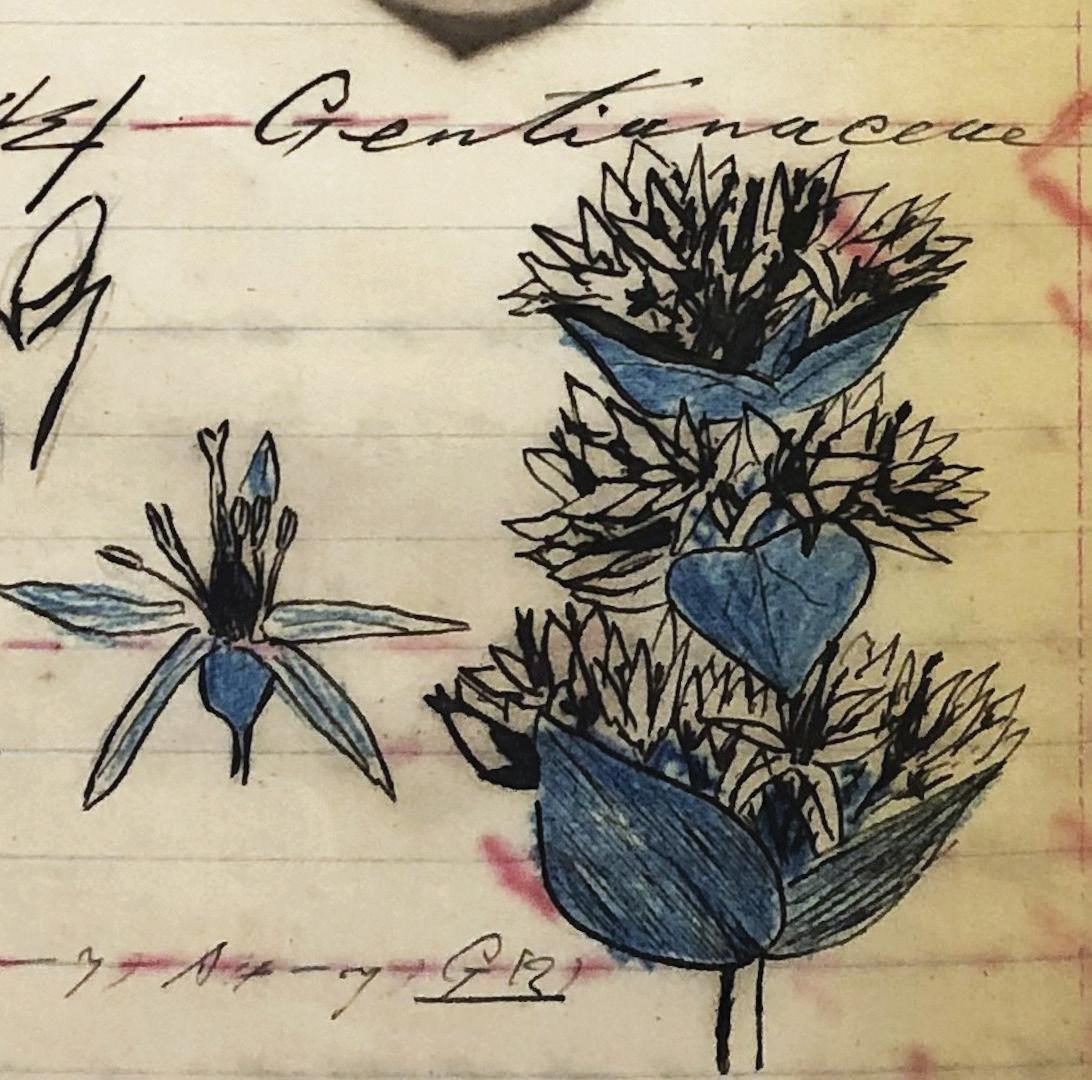

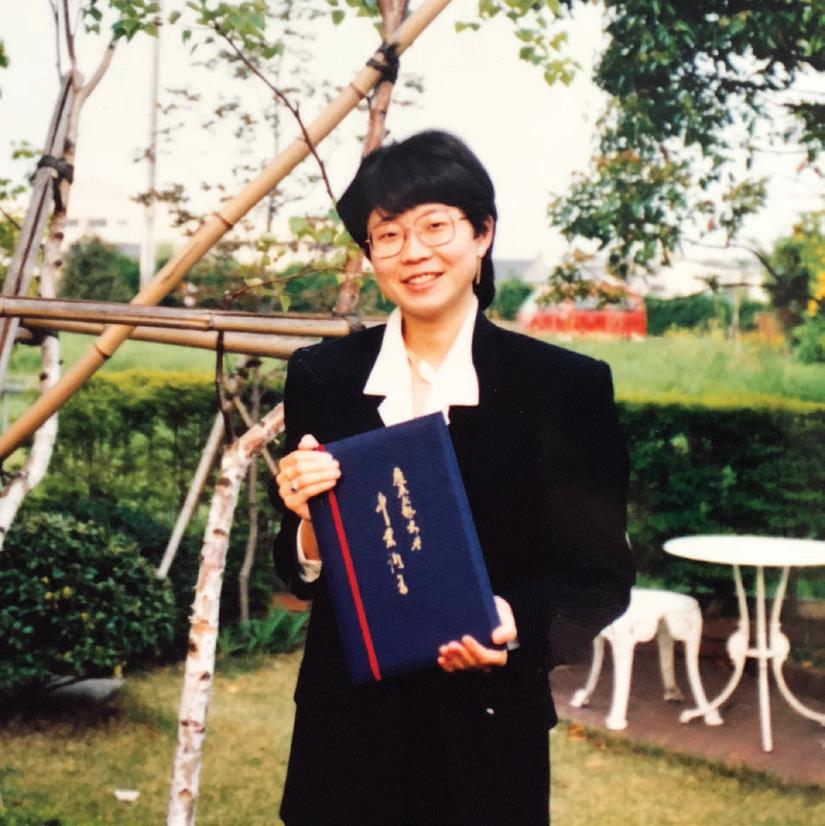

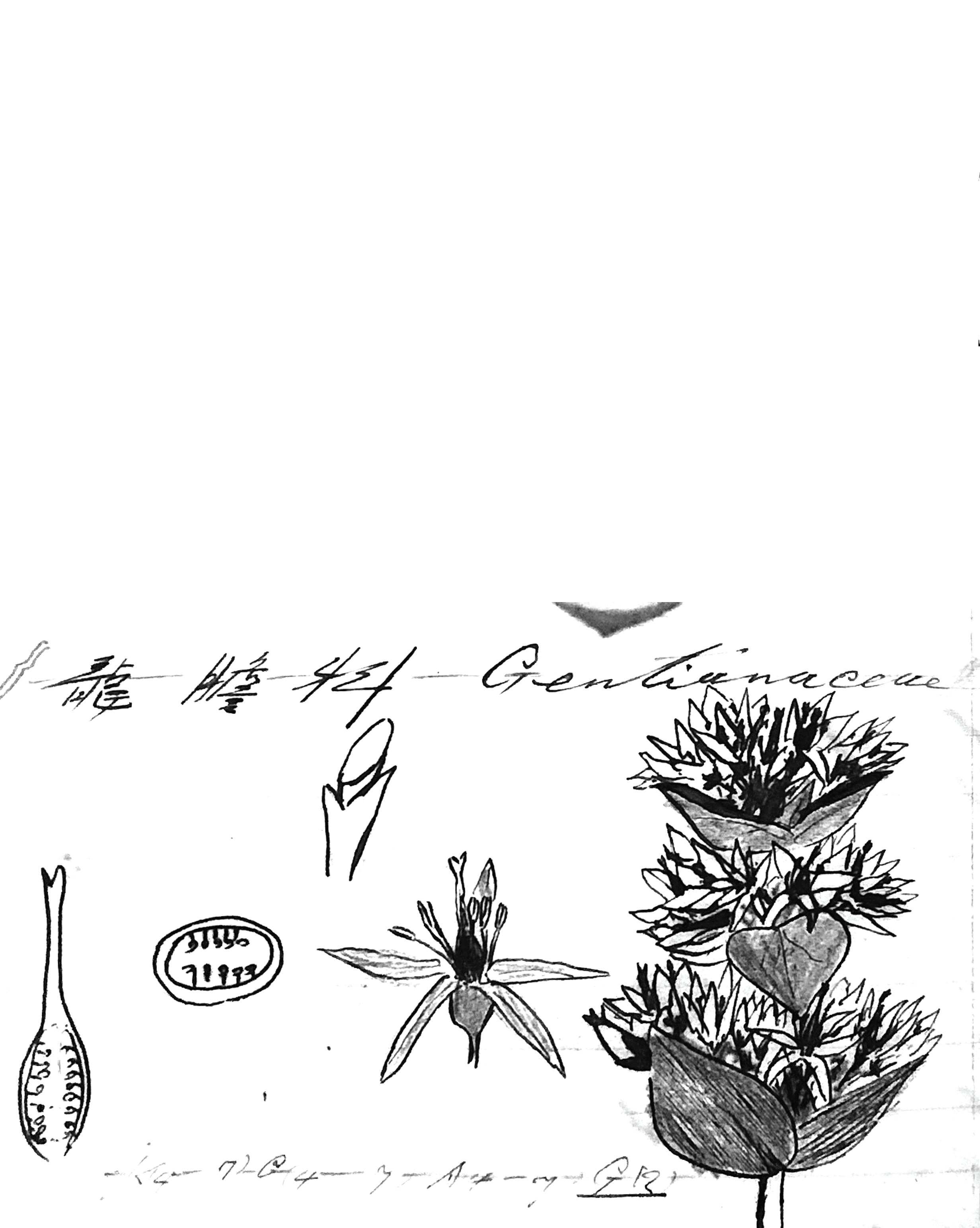

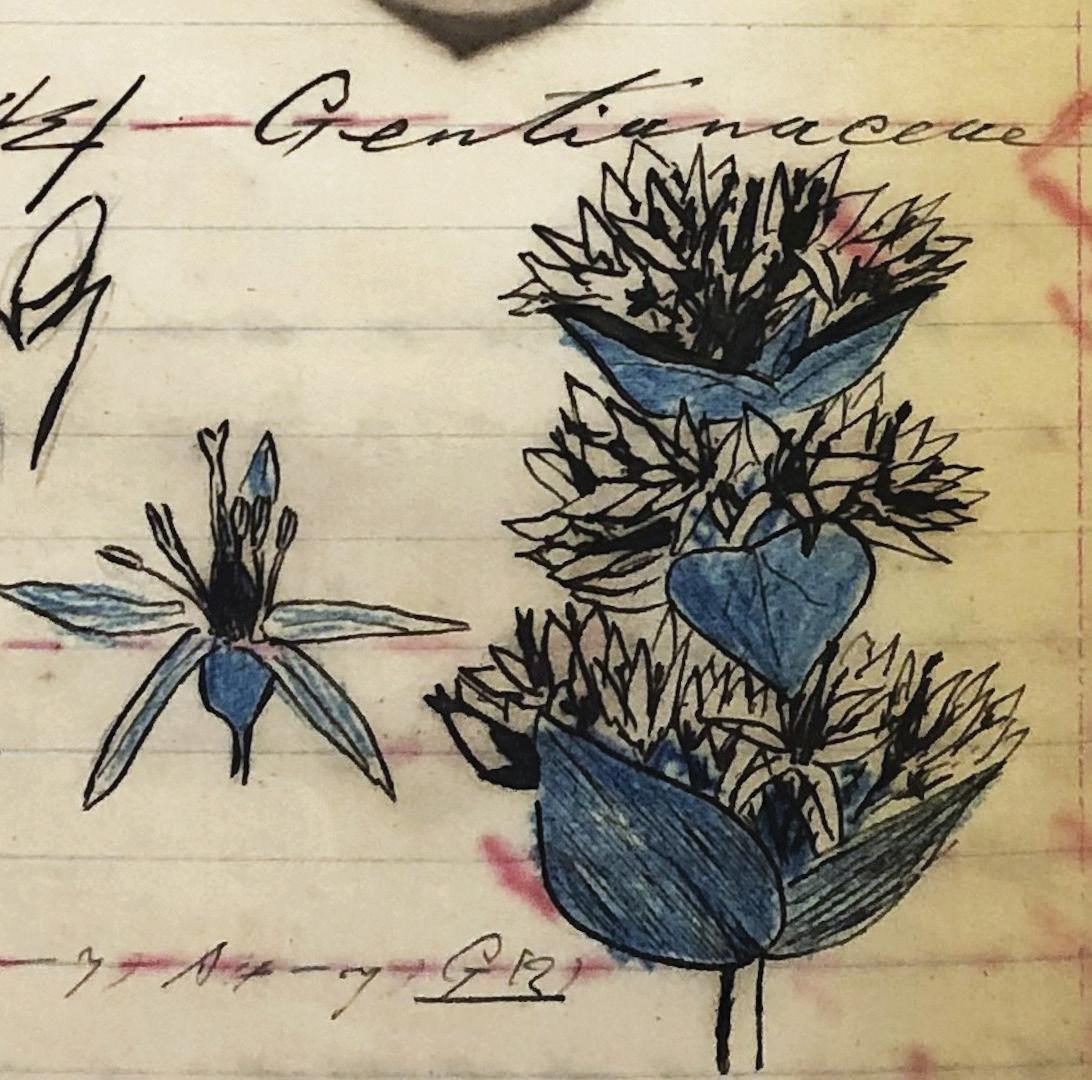

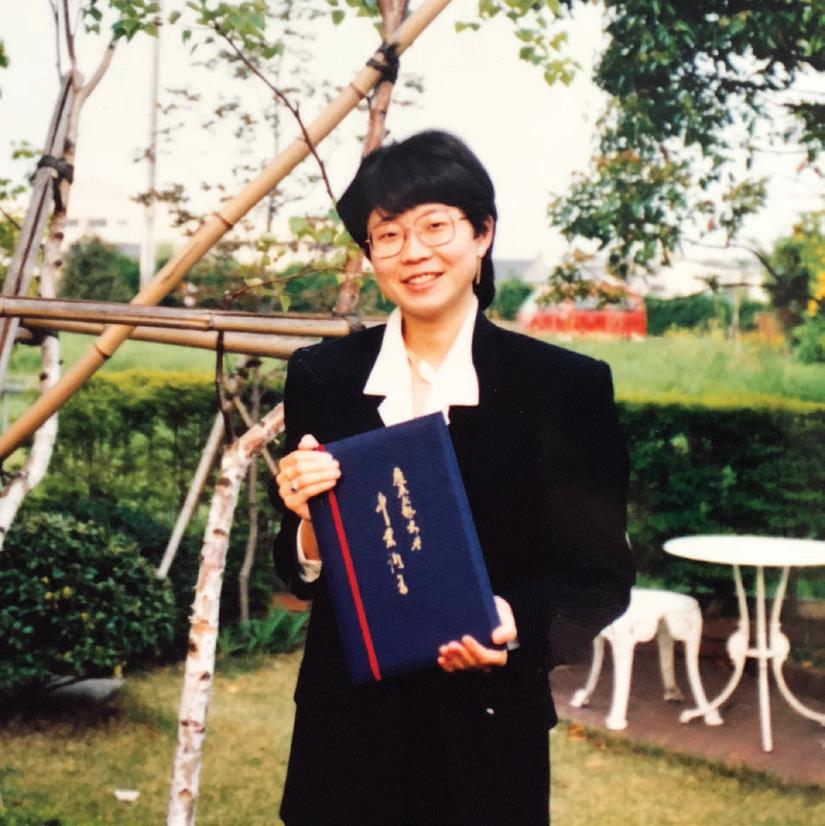

There’s much to digest in other sections of Omnia, too. “Omnia 101” (p. 12) looks into what polling can actually tell us in this 2024 Presidential election year. We’ve added a Faculty Bookshelf (p. 9) and a Research Roundup (p. 11), and our Student Spotlight section, which begins on p. 52, covers a Ph.D. student studying violinmaking and an undergraduate using linguistic models to analyze conversations, plus the winners of the Penn Grad Talks. And for the first time, we brought our long-running digital series, “Origin Stories” into the pages of the magazine (p. 62), focusing on the path Ayako Kano, a professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, took from a childhood in Japan—by way of Germany and New York—to Penn.

We’d always love to hear what you think, no reader survey required.

Michele W. Berger, Editor

Michele W. Berger, Editor

Top right: On June 20, 1934, the College of Liberal Arts for Women graduated its inaugural 11 students. Five came from Philadelphia, with the farthest—one Mary Ann Fees—hailing from some 300 miles away in Kane, Pennsylvania.

asked

to come up with a way to visually capture the idea of sound, the subject of Laura Dattaro’s cover story for this issue. “My creative journey began with unique challenges,” Chiang said. “The experience of perceiving the world through sound is inherently non-visual. Thus, I crafted this piece to offer viewers a glimpse into the auditory world, using visual elements that mirror the essence of sound.” —Drew Nealis, Graphic Designer

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

EDITOR’S NOTE

We

illustrator Maggie Chiang

3

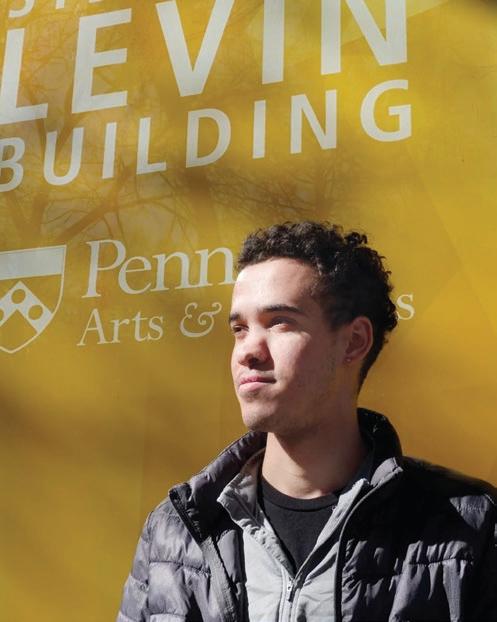

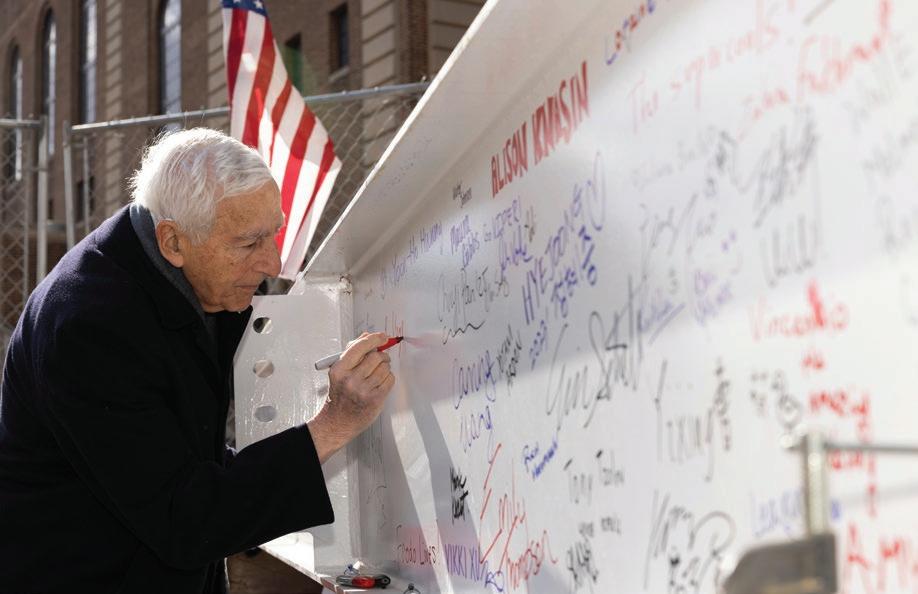

A Graduation Celebration for Penn Arts & Sciences

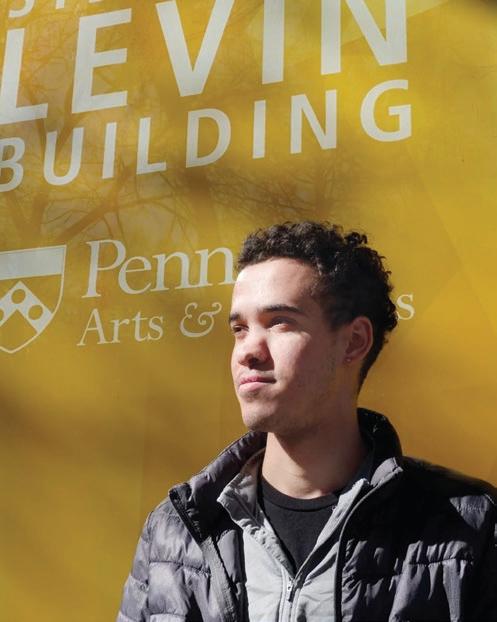

The College of Arts & Sciences Graduation Ceremony for the Class of 2024 was held on May 19 at Franklin Field. The featured speaker, James “Jim” Johnson, C’74, L’77, is a member of the School of Arts and Sciences Board of Advisors and the inaugural chair of the College External Advisory Board.

Johnson served as General Counsel of Loop Capital Markets, LLC, an investment banking firm located in Chicago, from 2010 until his retirement in 2014. Prior to that, he served as Vice President, Corporate Secretary, and Assistant General Counsel of the Boeing Company from 1998 to 2009. Johnson earned a B.A. in history and a J.D. from Penn, and he returned in 2021 for a certificate in climate change from the College of Liberal & Professional Studies.

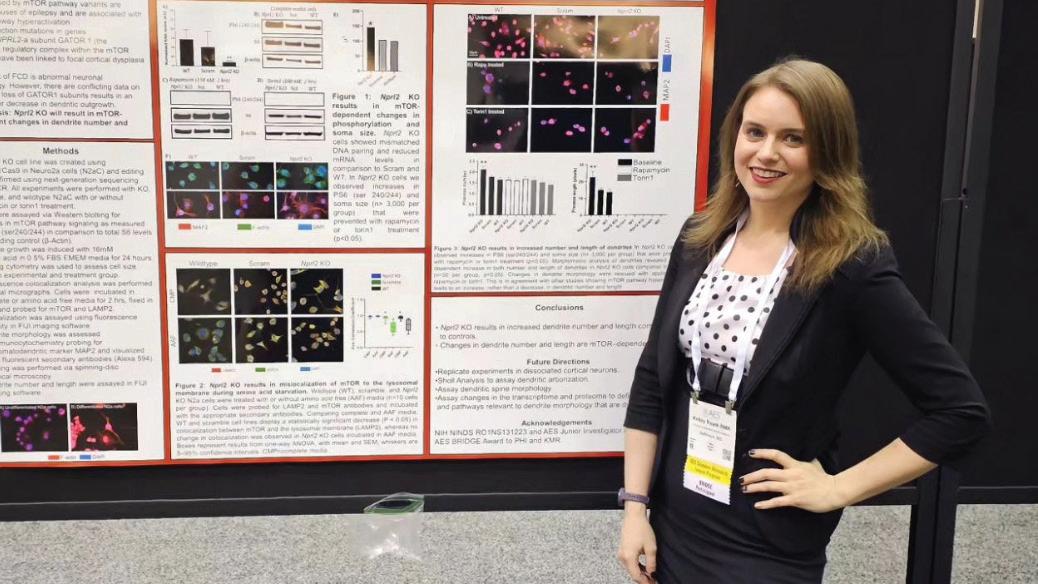

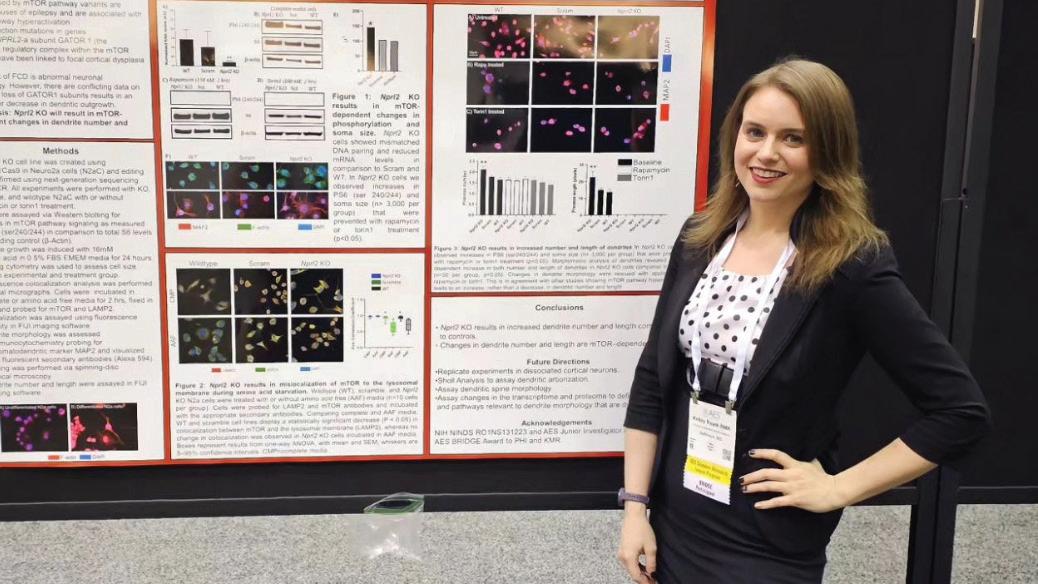

Student speaker Katie Volpert, C’24, majored in philosophy and political science and minored in survey research and data analytics. As president and captain of Penn Mock Trial, she won 15 outstanding attorney awards. After graduation, Volpert will work as a deputy clerk at the General District Court in Charlottesville, Virginia, before applying to law school.

The Penn Arts & Sciences Graduate Division held its ceremony on May 17 in Irvine Auditorium, with Dorothy Roberts, George A. Weiss University Professor of Law and Sociology, as the featured speaker. Roberts, an internationally acclaimed scholar, public intellectual, and social justice activist, is also founding director of the Penn

Program on Race, Science, & Society.

Student speakers for the Graduate Division Ceremony included Marielle Ong, GR’24 (Math), Caroline Hodge, GR’24 (Anthropology), and Daniel Morales-Armstrong, GR’24 (History and Africana Studies).

On May 18, the College of Liberal & Professional Studies celebrated its graduating class at the Kimmel Center. Michael Weisberg, Bess W. Heyman President’s Distinguished Professor and Chair of Philosophy at Penn, gave the address. Weisberg, a philosophy of science scholar, is also director of the Galápagos Education and Research Alliance, interim director of Perry World House, and a senior negotiator at United Nations Climate Conferences.

OMNIA | ALL THINGS PENN ARTS & SCIENCES Lisa J. Godfrey; Edward Savaria SCHOOL NEWS

4

(Clockwise from left) More than 1,300 students, including Communication majors Crystal Marshall, C’24, Rene Chen, C’24, and Oscar Vasquez, C’24, received degrees from the College of Arts and Sciences on Sunday, May 19. Ceremonies for the Graduate Division and the School of Liberal & Professional Studies took place on the Friday and Saturday prior, with Dean Fluharty (top right) speaking at all three celebrations.

Paul Sniegowski Named President of Earlham College

Paul Sniegowski, Stephen A. Levin Family Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and Professor of Biology, will leave Penn this summer to assume the presidency of Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, as of August 1.

Sniegowski has headed the undergraduate programs of the College since 2017. “His achievements in that role, and his commitment to educational excellence throughout his 27 years at Penn, make clear why Earlham has sought out his leadership,” says Steven J. Fluharty, Dean and Thomas S. Gates, Jr. Professor of Psychology, Pharmacology, and Neuroscience. “As College Dean, Paul has ensured that the undergraduate curriculum is always evolving, adding new minors and this year initiating a review of our longstanding General Requirement.”

In addition, Sniegowski has promoted inclusion in the undergraduate learning experience in a number of ways: He has led several inclusive teaching initiatives in the College, has been a strong partner in Penn’s programs for first-generation, lowincome (FGLI) students, and established a College advisory board for FGLI students. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Sniegowski facilitated moving the entire College quickly to online instruction, engaging with faculty, students, and staff to ensure the continued quality of instruction in an unprecedented time.

“Being named to a college presidency is a tremendous honor, and Paul’s appointment at Earlham is a well-deserved tribute to his devotion to student learning and to liberal arts education,” Fluharty adds. “He will be greatly missed at Penn.”

In Recognition of Outstanding Teaching

Each year, the University and the School of Arts & Sciences recognize faculty, lecturers, and graduate students for their exemplary teaching. The 2024 honorees include 21 people from 11 departments and programs.

At the University level, five Penn Arts & Sciences faculty received recognition:

Christian R. and Mary F. Lindback Award for Distinguished Teaching

Gary Bernstein, Reese W. Flower Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics

David Wallace, Judith Rodin Professor of English

Provost’s Award for Distinguished Ph.D. Teaching and Mentoring

Holly Pittman, Bok Family Professor in the Humanities

Arjun Yodh, James M. Skinner Professor of Science

Provost’s Award for Teaching Excellence by Non-Standing Faculty

Judith N. Currano, Head, Chemistry Library

In addition, Penn Arts & Sciences recognized the following faculty, who were celebrated at a school-wide reception on May 2:

Ira H. Abrams

Memorial Award for Distinguished Teaching

Charles Kane, Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Physics

Michael Weisberg, Bess W. Heyman President’s Distinguished Professor of Philosophy

Dennis M. DeTurck Award for Innovation in Teaching

Simon Richter, Class of 1965 Term Professor of German

Dean’s Award for Mentorship of Undergraduate Research

Melissa Wilde, Professor of Sociology

Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching by an Assistant Professor

Julia Alekseyeva, Assistant Professor of English

Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching by Affiliated Faculty

Michael Kane, Senior Lecturer, Neuroscience

Jenine Maeyer, Senior Lecturer and Director, General Chemistry Laboratory

Liberal and Professional Studies Award for Distinguished Teaching in Undergraduate and Post-Baccalaureate Programs

Virginia Millar, Faculty, Penn LPS Online Certificate in Applied Positive Psychology

Liberal and Professional Studies Award for Distinguished Teaching in Professional Graduate Programs

Sarah Willig, Advisor and Lecturer, Master of Environmental Studies

Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching by Graduate Students

Meredith Hacking, Francophone, Italian, and Germanic Studies

Matty Hemming, English

Tessa Huttenlocher, Sociology

Ethan Plaue, English

Daniel Shapiro, Political Science

Derek Yang, Chemistry

Youngbin Yoon, Philosophy

SPRING/SUMMER 2024 SCHOOL NEWS

Brooke Sietinsons 5

Paul Sniegowski, Stephen A. Levin Family Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and Professor of Biology

Students Honored as 2024 Dean’s Scholars

Penn Arts & Sciences named 20 undergraduate and graduate students as this year’s Dean’s Scholars, a recognition bestowed annually on students who exhibit exceptional academic performance and intellectual promise. They were celebrated at the Stephen A. Levin Family Dean’s Forum on April 17.

College of Arts & Sciences

Natascha Barac, C’23, English and Physics

Rema Bhat, C’24, Political Science

Sophie Faircloth, C’24, Linguistics, submatriculant in Linguistics

Andreas Ghosh, C’24, ENG’24, Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research

Sophie Mwaisela, C’24, History

William (Zijian) Niu, C’24, Biochemistry, Chemistry, and Biophysics

Liam Phillips, C’24, Russian and East European Studies and Comparative Literature

William Stewart, C’25, Music Yijian (Davie) Zhou, C’24, Philosophy and Psychology, submatriculant in Philosophy

College of Liberal and Professional Studies –Undergraduate Program

Joe Daniel Barreto, LPS’23, Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences

College of Liberal and Professional Studies –Professional Master’s Programs

Abigail P. Blyler, LPS’24, Master of Applied Positive Psychology

Graduate Division –Doctoral Programs

Adwaita Banerjee, Anthropology

Charlie Cummings, Physics and Astronomy

Cianna Z. Jackson, Classical Studies

Ryann Michael Perez, Chemistry

Rashi Sabherwal, Political Science

Timmy Straw, Comparative Literature and Literary Theory

Elena Gayle van Stee, Sociology

Christine Soh Yue, Linguistics

Oscar Qiu Jun Zheng, East Asian Languages and Civilizations

with Emily

College for Women

1963 Term Professor in the

in the Department of Classical Studies. In front of an audience of 1,500 people—some 900 in Irvine

,

for

styles, how to decide which narrative voice to use, feminism, revisiting works decades

,

OMNIA | ALL THINGS PENN ARTS & SCIENCES

Lisa J. Godfrey

SCHOOL NEWS

The 2024 Stephen A. Levin Family Dean’s Forum featured acclaimed author Margaret Atwood, in conversation

Wilson,

Class of

Humanities

Auditorium and 600 online—the two discussed writing

later, The Odyssey

and more. Atwood, best known

her dystopian classic The Handmaid’s Tale

has written more than 50 books during a career spanning six decades. Wilson won praise for her translation of Homer’s The Iliad, which published in 2023, and The Odyssey, which published in 2018.

6

Pushing the Boundaries of Human Brain Imaging

To study the human brain, really study it, and its relationship to the human mind, relatively little compares to using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), according to Joseph W. Kable, Jean-Marie Kneeley President’s Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Marketing and director of MindCORE, Penn’s hub for the integrative study of the mind. “fMRI is a work-horse technology for trying to understand the relationship between the human brain and behavior.”

As of this past May, MindCORE has in its toolkit its very own fMRI machine, the centerpiece of the new MindCORE Neuroimaging Facility established under the Mapping the Mind goal outlined in the Penn Arts & Sciences strategic plan.

The machine, a MAGNETOM Cima.X 3 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging wholebody scanner, received FDA approval in early 2024. It’s the newest fMRI iteration from the company Siemens Healthineers and offers incredibly high-resolution images quickly, with a unique GEMINI

gradient coil system that makes visible previously hidden underlying structures.

“The goal here is to provide access to the resource for a large community of people” across the University, Kable says.

Bringing the magnet to MindCORE has been several years in the making. Excited conversations began in 2019, but then the pandemic, coupled with the desire to wait for the “next generation” of fMRI, stalled the plans. Once FDA clearance came through, the installation itself was its own undertaking, says Andrew Jones, Engineering Projects Manager in the School of Arts & Sciences’ Facilities Planning and Operations.

“The space to hold the fMRI is underground, so we dug a pit outside of the building. It’s a concrete vault,” explains Jones, who oversaw the project. “Because these machines are so heavy, you often put them on the ground floor of whatever building they’re in. Sometimes you have to get creative in how to get them there.”

Tyshawn

Sorey Wins Pulitzer Prize in Music

Presidential Assistant Professor of Music Tyshawn Sorey, a multiinstrumentalist and composer who has performed around the world, won the 2024 Pulitzer Prize in Music for “Adagio (For Wadada Leo Smith).” The saxophone concerto premiered on March 16, 2023, at Atlanta Symphony Hall. In 2023, Sorey’s composition “Monochromatic Light (Afterlife)” was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in the same category.

In this case, that meant using a crane to lift and lower the fMRI into the room—one where the floor had been isolated from everything around it to prevent vibrations from affecting the machine’s functionality—then sealing the space from above. Should the machine need future servicing or updating, the “lid” should allow for easier access, Jones says. All told, the install took three weeks.

Penn is one of just a few universities with such a machine strictly for this kind of research. “The time had come for Penn to have a facility dedicated to basic research on the human brain,” says Kable.

Because the work of many MindCORE researchers includes children, there are plans to purchase a mock MRI to acquaint these youngest of study subjects with the technology. MindCORE also hired an executive director of the new facility, Brock Kirwan, who began May 1. “Our researchers are eager to use this tool,” Kable says, “to push the boundaries of human brain imaging.”

—MICHELE W. BERGER

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

SCHOOL NEWS

Brooke Sietinsons

7

In April, the new fMRI machine at Pennovation Works was lifted and lowered by crane into the Pennovation Lab building.

Bob Dylan as Modern-Day Prophet

In his new book, political theorist Jeffrey Green takes a unique view of the famous musician.

BY MATT GELB

Bob Dylan was just 22 when the Emergency Civil Liberties Union recognized him with the Tom Paine Award for his contributions to social justice. His activism in the progressive causes of the time—December 1963— was unmistakable. But as Dylan accepted the award, he ranted against those in attendance. He mocked them and disavowed politics, calling it “trivial.” He was subsequently booed off the stage.

A few months later, Dylan wrote a song called “My Back Pages,” which laid bare his internal conflict. “Fearing not I’d become my enemy / in the instant that I preach,” Dylan sang. He was testifying to the notion that individual freedom opposes social justice, a clash central to Jeffrey Green’s new book, Bob Dylan: Prophet Without God

Green, a professor of political science and director of Penn’s Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy, spent eight years analyzing Dylan’s words from a political theorist’s perspective. He finds that Dylan is a modern-day prophet of a special kind: “a prophet of diremption,” in Green’s words. Or, metaphorically, a prophet without God.

“He inherits three values,” Green says. “He speaks in his music and in his statements to issues of individual freedom, to social

justice, to adherence to God. But he’s at his prophetically most distinct when he testifies to the collision between these values, and then derives some ethical consequences from those collisions.”

Green says this makes Dylan an unusual visionary—not a prophet of salvation, telling people what to do or what direction to follow, but rather a prophet constantly dealing with those three values and never solving them.

“He was affiliated with the left, but then he withdraws and owns it and sings it,” Green says. “He doesn’t say, ‘I’m now a conservative’ or ‘I don’t actually have any moral obligation.’ He says, ‘I recognize those things, but I also have a competing desire to do what I want. To be free.’

And I find that unusual in the history of political thought.”

In three sections of the book, Green traces Dylan’s evolution: his rebelling against the mid-1960s civil rights movement, his sudden conversion to evangelical Christianity in the late 1970s, and the political pessimism that runs through the entirety of Dylan’s work.

The third part of the book is called “Strengthen the Things that Remain,” which comes from the Book of Revelation. But it’s also a line from one of Dylan’s songs, “When Are You Going to Wake Up?”

In the song, “he accuses both political idealism and political realism of being asleep,” Green says. “I see this as a conflict between God and justice. Rather than see the world as something redeemable in this life or in a life to come, or as something masterable in its fallenness, I think Dylan invites us to see how an ordinary person might confront a world permanently gone wrong.”

Green admits this is a project out of the ordinary for political theory. Dylan, often in harsh language, has railed against those attempting to interpret him. “You’re wasting your life,” Dylan told his critics in a 2001 interview. And still, more than a thousand books have been written about Dylan. Green’s was a “labor of love,” prompted by the memory of a 16-year-old version of himself who, in 1990, bought a Dylan box set and was transfixed.

“A lot of it was too much for me,” Green says. “It was over my head. A lot of it still is over my head. But I think what’s gratifying about Dylan is 10 years later, you can suddenly understand a lyric that escaped you before. He’s had a big influence on me as a person.”

Matt Gelb, frequent contributor to Omnia, is a Philadelphia-based sportswriter whose work has been featured in The Athletic and The Philadelphia Inquirer

FINDINGS 8

Impressionism and Time

A new book from History of Art Professor André Dombrowski connects the works of artists like Claude Monet with the emergence of modern-day timekeeping.

BY KATELYN SILVA

or many Impressionist painters, capturing a fleeting moment—what’s known as “instantaneity” in Claude Monet’s own words—became a popular theme for their work, especially during a period in history when society was grappling with the emergence of modern timekeeping.

In his new book, Monet’s Minutes: Impressionism and the Industrialization of Time, André Dombrowski, Frances Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Associate Professor of 19th Century European Art in History of Art, delves into the subject, arguing that Monet’s celebration of instantaneity was more than just a simple aesthetic choice. Rather, it was deeply rooted in the shift during Monet’s lifetime toward a world increasingly concerned with keeping accurate time and the technologies invented to do so.

The book’s inspiration came to Dombrowski while studying the early work of Paul Cézanne. “I came across a fantastic book by Peter Galison called Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps, about the relationship between modern bureaucratic time and the theory of relativity. At the same time, I was teaching an

undergraduate lecture course on Impressionism. Going through the major dates associated with Impressionism, I realized just how incredibly parallel they were to the development of modern timekeeping,” he explains.

The birth of Impressionism, an art movement focused on capturing the transient effects of light and color in the natural world, and widely known through the work of artists like Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, occurred in the mid1860s, with the first major exhibitions taking place in the 1870s. The movement marked a significant departure from the traditional, detailed, realistic representation of subjects previously prevalent in art.

At about the same time, the world started reconsidering the nature of time. Around 1865, Dutch physiologist F.C. Donders began to think about whether reaction time in humans was measurable. In 1884, in Washington, D.C., a gathering of nations voted to establish Greenwich as prime meridian and create what would become the modern global time zones. And in 1886, the final of eight Impressionist Exhibitions occurred.

In the book, Dombrowski knits together these histories to unearth their concrete intersections. Monet is his central player, an artist who, as Dombrowski notes, “registers this profound change toward a much more artificial, cultural, standardized approach to time.” Dombrowski uses as examples Monet’s paintings of trains and train stations, with their exacting schedules, and his “series” paintings that depicted one subject—a haystack, for example—at many times of day.

Dombrowski says he hopes readers come away from his book with a different understanding of Impressionism, one rooted in the context of time habits shifting away from more natural ones, like rising with the sun, to what exists today, a clock- and schedule-based standard and uniform time that garners almost universal agreement regarding its function, meaning, and value.

Katelyn Silva is a freelance writer based in Providence who covers a wide range of topics for colleges and universities including Penn Arts & Sciences, Northwestern, Johnson and Wales University, and the University of Chicago.

FACULTY BOOKSHELF

Recent books from Penn Arts & Sciences faculty

Sounding Latin Music, Hearing the Americas

JAIRO MORENO

Professor of Music

Behind the Startup: How Venture

Capital Shapes Work, Innovation, and Inequality

BENJAMIN SHESTAKOFSKY

Assistant Professor of Sociology

Merze Tate: The Global Odyssey of a Black Woman Scholar

BARBARA D. SAVAGE

Geraldine R. Segal

Professor Emerita of American Social Thought

Slouch: Posture Panic in Modern America

BETH LINKER

Samuel H. Preston Endowed Term Professor in the Social Sciences

The Tame and the Wild: People and Animals after 1492

MARCY NORTON

Associate Professor of History

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

FINDINGS

F

Illustrations by Nick Matej 9

The Global Supply Chain’s Surprising Linchpin

When massive cargo ships arrive late to port, the delay sets off a domino effect that influences U.S. inflation, according to research from economist Jesús Fernández-Villaverde and colleagues.

BY MICHELE W. BERGER

n late March, a 985-foot-long cargo vessel called the Dali lost power, hitting the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore. The resulting collapse was deadly, killing six people. It also closed the Port of Baltimore—which generates billions of dollars and supports more than 15,000 direct jobs—for more than a month.

“Dozens of ships had to be re-routed, causing delays in all the North Atlantic logistics,” says Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, a professor of economics and director of the Penn Initiative for the Study of Markets. “The accident highlights the fact that even small disturbances in the global supply chain can have large consequences.”

Around the world, there are some 5,500 cargo ships like Dali on the move at any one time; 500 are so large that a single one carries more cargo than the large convoys did during World War II. Delays at port set off a chain reaction. “Say you have a container ship coming from Shanghai that was supposed to arrive to Los Angeles on December 7th. Instead, it arrived on the 9th, and suddenly, a lot of downstream production could not be completed,” says Fernández-Villaverde.

He and colleagues wondered whether such delays might affect the global supply chain and, in turn, U.S. inflation rates, a

question spurred by inflation hikes during the pandemic. “There was a lot of discussion about why inflation was going up so much during COVID,” he says. “Some people said it could be because of all of these global supply chain disruptions, but the problem was, we didn’t have a very good measure of them.”

To address this, Fernández-Villaverde and colleagues from Tsinghua University, the University of International Business and Economics, and the University of Oxford developed a machine-learning algorithm that included location, speed, and other publicly available data every ship sends from its transponder to a satellite. Using their algorithm, the researchers could then determine how many of the massive container ships were stuck outside of ports trying to get in and what happened because of the logjam.

“Why is this a good measure?” FernándezVillaverde says. “Because it turns out that these gigantic ships operate like buses on a fixed schedule.”

The researchers found that arrival even one day late could be costly: Such delays clogged ports, deferring when goods could be removed and when ships could leave. Inflation rates took a hit in the process. “We found that most of the reason inflation

spiked in 2021 was the global supply chain,” he says. “By 2022, the global supply chain had normalized and yet inflation was still high. We realized this was the Federal Reserve System dropping the ball, that it was a little too slow to react.”

Understanding this domino effect could help the U.S. prepare for a future disruption to the global supply chain from, say, a war, Fernández-Villaverde notes. “Beyond that, I’ve been disappointed that not a lot of researchers have done COVID-19 follow-up. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of interest in saying, ‘Let’s review the game from last Sunday to think about how we are going to play the game next Sunday.’ That’s always less attractive to publish, but to me, it’s really important.”

Down the line, Fernández-Villaverde says the ship data he and colleagues tapped into could be used for applications like measuring traffic through waterways such as the Panama and Suez canals. It’s important to better understand this system, he says. “We have become dependent on a global supply chain that is incredibly efficient but also extremely fragile.”

Michele W. Berger is editor of Omnia and director of news and publications for Penn Arts & Sciences.

FINDINGS

I

10

Colorful Language

Biology and psychology researchers reveal that the way colors have been described historically constrains how they might be described in the future.

BY ERICA MOSER

magine you and a friend are playing a guessing game: Using descriptive words alone, you challenge your friend to correctly identify the hue of individual color swatches. If your friend frequently guesses right, that means your shared language has what’s called an efficient color naming system.

These vocabularies are constrained both by how people perceive colors and by how much they want (or need) to discuss a given color. For example, in a 2021 study led by Joshua Plotkin, Walter H. and Leonore C. Annenberg Professor in the Natural Sciences, and Colin Twomey, then a postdoc and now interim executive director of the Data Driven Discovery Initiative, researchers found that the need to communicate about reds and yellows is high across languages; greens are more important in some.

For that work, they collaborated with David Brainard, RRL Professor of Psychology. Now, the three have identified another constraint on efficient color vocabulary: history.

In a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they show that a language’s past color vocabulary shapes its ability to evolve. The starting point places the initial restrictions, with the possibilities of how many directions it can go narrowing as the vocabulary itself continues to expand.

To draw these conclusions, the researchers used the publicly available World Color Survey, a large database of color-naming terminology that includes speakers from 110 language backgrounds naming 330 color stimuli. Specifically, Twomey and colleagues explored the introduction of new terms and the probability that a given word would change meaning as the size of the color vocabulary increased. For example, one efficient color vocabulary might combine green and blue—in other words, green-blue—and another might separate them as individual colors.

“In principle,” Plotkin says, using this information, “we can infer what ancestral color vocabularies were and then compare that to the historical record.” This historical constraint doesn’t apply only to colors, he adds, but to other categorization, like for consumer products or weather conditions, for instance.

Broadly, Brainard says, the study represents the idea that communication needs, historical constraints, and efficiency result in linguistic categories that are constantly refined. “The ideas, we hope, will apply to how we name and categorize and communicate about all kinds of things.”

Erica Moser is a science writer in University Communications at Penn.

RESEARCH ROUNDUP

Shape Shifters

Archaea, single-celled organisms once thought to survive only in the most extreme environments, actually exist in lakes and oceans, in soil, even in the human gut. Yet despite their ubiquity, little is known about them, not even what determines their shape. Biology Professor Mecky Pohlschröder and colleagues have unshrouded some of the mystery. Studying the cells of an organism called Haloferax volcanii, the interdisciplinary research team identified a diverse set of proteins that help determine whether the organism will be rod-shaped, diskshaped, or transition from one to the other—a factor that affects how the organism can function in and adapt to its environment. The findings appeared in Nature Communications.

Domestic Violence Laws

Intimate partner violence affects millions of women and girls across the globe, but the laws that protect them vary widely. Jere Behrman, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Economics, and colleagues from UCLA and Stony Brook University wanted to understand how such variations influence certain life decisions for women and how those decisions factor into what’s known as “wasting”—when children weigh too little for their height. In findings published in PLOS One, the researchers showed that having domestic violence laws in place increased women’s decision-making autonomy in healthcare and finances by almost 17 percent and 6 percent, respectively. This directly affected wasting, dropping the probability it would happen by about a third for children up to age 5.

Stable Glass

Though stable glass takes millennia to form naturally, researchers have been trying to better understand this aging in an effort to speed it up. One way to do so is to make a glass from vapor instead of cooling a liquid. Now, work from the lab of Zahra Fakhraai, a professor in the Department of Chemistry, and colleagues from Brookhaven National Lab has revealed that forming the glass on a softer, more flexible surface “dramatically accelerates” the timetable—by decades—and creates more rigid, denser glass. The findings, published in Nature Materials, could result in new methods to precisely engineer glass films and have possible implications for applications like semiconductors.

I FINDINGS

Illustrations by Nick Matej 11

WHAT CAN POLLS TELL US IN 2024?

John Lapinski, Robert A. Fox Leadership Professor of Political Science and director of the Robert A. Fox Leadership Program and the Penn Program on Opinion Research and Election Studies, talks polling in this Presidential election year.

By Jane Carroll

By Jane Carroll

If there is one thing Americans can count on during any Presidential election year, it’s the constant commentary about polls. But how has polling changed in the digital age? How accurately can polls predict election outcomes? What purpose do they serve?

Omnia put these questions to John Lapinski, Robert A. Fox Leadership Professor of Political Science and director of the Robert A. Fox Leadership Program and the Penn Program on Opinion Research and Election Studies (PORES). Lapinski also directs the Elections Unit at NBC News, where he is responsible for projecting races for the network and producing election-related stories through exit polls.

OMNIA 101 Gracia Lam 12

Why do polling?

There has been a lot of discussion within network news and other media outlets about whether we should continue to run polls and in the same way we’ve been doing it. There have been misses with polling recently, primarily in election polls. Is it critically important that people have a sense of who may or may not win an election before election night? I don’t think so, but it is important, given that we live in an electoral democracy, that we have some way of measuring public opinion; otherwise, the people elected to represent us won’t know what we want. Polls are the best way to convey that information. For a healthy functioning democracy, public opinion is important, and the best way to measure public opinion is through polls.

How has polling changed in the past few decades?

It’s tremendously different. At NBC, it used to be that a large percentage of people we called wanted to take our polls. That’s not true now. So, the question is, is the small percentage of people who answer representative of the population we’re interested in studying? Are we able to statistically weight the data? A lot of public opinion researchers have been astonished that as response rates have plummeted, our polls still seem okay, so that’s a puzzle. Polls have lots of problems, but we’ve had success with them, too.

How do pollsters reach people?

The gold standard used to be that we’d use agreed-upon sampling techniques and then do a telephone poll on landlines and cell phones. We’ve seen big differences in response rates when using online methods versus telephone.

There are differences in subgroups within a population, and it’s very pronounced with younger people.

We’re doing a huge experiment right now at PORES, running five different surveys, including telephone interviews with both landline and cellphone interviews, a text survey, and two different online methods. We’ll be asking exactly the same questions at the same time. Then we will pull them all together and try to assess whether different respondents answer different survey modes or if the content of respondent answers differ based on mode. You need a multi-method approach to reach a representative group of people today, and then you have to figure out ways to essentially put the people back together into one survey.

What is a poll aggregator?

Aggregators take publicly available polls and average them. RealClearPolitics is an example. Proponents of aggregators say that, given the variability among different polls, an average will yield a more accurate picture. But critics say that aggregators, by including polls of dubious origins, can manipulate the results.

Does polling affect turnout?

In general, polls can’t predict turnout. People say that Biden voters this year are not enthusiastic, and, given that recent elections have been decided by so few voters, that could be pivotal. But polls can’t predict what people will actually do on Election Day. People make assumptions about what the electorate will look like and then bake them into their poll results— it is important to remember that. Sometimes those assumptions

are right and sometimes they are wrong, but they are always important to the poll’s results.

You’ve said you think some recent polls have been wrong. How do you know?

Let’s take the February 2024 New York Times/Siena poll that had Trump up five points over Biden. We use a statistical technique called multi-level regression with poststratification, or MRP. It’s a methodology that allows us to take a national poll, break down the results, and come up with state-bystate estimates. Using that technique, Trump leading by five would mean that he would win well over 300 Electoral College votes, probably more than 320 or 330, but that’s completely implausible. We’ve already seen that polls were off in the primaries. We can go state by state and see where polls predicted Trump winning by quite a bit more than he actually did.

One of the beautiful aspects of election polls is that you can determine whether they’re accurate or not because elections happen. Here’s what the poll said, here’s what the results said. Of course, there are data in these polls that certainly are correct—and to me, they are telling us that people aren’t satisfied with their choices on either side.

Any predictions?

This will be a super-close election. I am confident I will be working 100-plus hours at NBC News during election week to project who will be the next president of the United States. And I don’t know who that person is yet.

Jane Carroll, CGS’00, is associate director of donor relations for the Penn Arts & Sciences Office of Advancement and writes frequently for Omnia

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

OMNIA 101 13

HISTORY ON THE RIVER

John Kanbayashi’s new seminar frames the past not by time or place, but through a natural feature that humans use but can’t fully control.

By Susan Ahlborn

John Kanbayashi is walking backward and talking about the Schuylkill River. The small group of students enrolled in his River History seminar follow attentively. Beside them is the river itself, brown and slow under a cloudy sky. On their other side are railroad tracks—a freight train drowns out Kanbayashi for a few minutes—and across the water, traffic on the Schuylkill Expressway moves almost as slowly as the river.

The original banks of this section of the Schuylkill are long gone, replaced by concrete as humans molded it to their needs.

But the river hasn’t always cooperated— it flows too slowly to carry away the waste dumped into it in the 19th century. Schuylkill means “hidden river” in Dutch, and for a while it was hidden from most Philadelphians by the refineries, factories, and abattoirs around it.

“You couldn’t always see the river,” says Kanbayashi, an assistant professor in History and Sociology of Science, “but you could smell it.”

Rivers are multifunctional by nature. They provide resources and transportation, often gateways to prosperity for societies, but they resist even the most sophisticated attempts at human control. They can also be political and religious symbols, technical objects, and historical

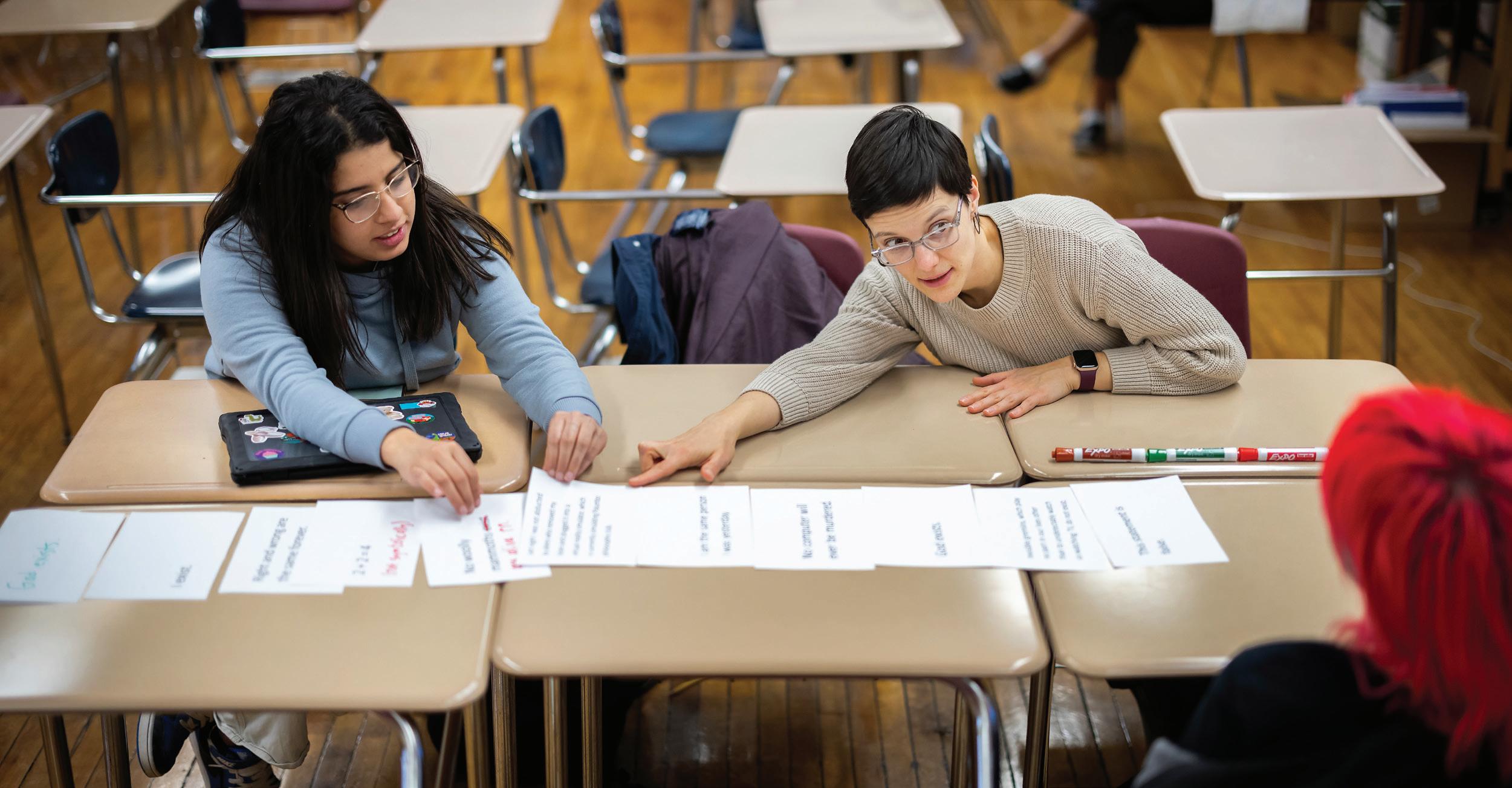

John Kanbayashi, Assistant Professor of History and Sociology of Science (left), on the east bank of the Schuylkill River with students in his River History class, including Nika Sadeghi, C’26 (far right). The class studied rivers all over the world, finding surprising connections.

IN THE CLASSROOM

14

Brooke Sietinsons

forces. Students in Kanbayashi’s seminar are using literature, film, and historical sources to explore these functions, examining rivers around the globe and how diverse societies have understood and employed them. Now, Kanbayashi is going a step further and bringing the class from Williams Hall to the Schuylkill to take in the river and its surroundings as he describes its role in the narrative of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania.

A historian of environment, science, and technology, Kanbayashi was inspired to create a history seminar organized not around a place or period, but a theme. “I thought it could be an opportunity to get students to cut across a lot of contexts and think about what might be distinctive or unique and what seems to be broadly shared,” explains Kanbayashi. He’s also introducing them to “the work of doing history, looking at primary sources and into difficult debates.”

out there and just explore and fully engross yourself in the material. Everyone contributed and built on each other.”

In one of these exchanges, the students held an in-class debate on the Three Gorges Dam in China that drilled down into many of the issues covered by the class. They looked at the hydroelectric power and opportunities the dam would provide but also at concerns ranging from compensation and new housing needed for displaced people to loss of cultural artifacts, environmental effects, and national security implications.

Kanbayashi assigned students to be pro or con for the in-class debate, but they eventually had to choose their own side for a written opinion piece. “The op-ed was different from a normal paper where you’re just stating and analyzing information,” says Sadeghi. “It was hard to choose to be for it or anti it because we learned so much about the advantages and the down sides.”

RIVER READING (AND WATCHING)

Select items from the syllabus offer a taste of the content students consumed in the River History course:

The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter

BY LI BAI, TRANSLATED BY EZRA POUND 8th Century

Ballad of the Dnieper

A SOVIET PROPAGANDA FILM 1943

Through the Johnstown Flood BY

DAVID J. BEALE

1890

When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts BY

SPIKE LEE 2006

One of the easy takeaways about history is that it offers a lot of lessons in humility. But there are lessons of success and hope as well.

Each week or two the class focused on a different river around the world. After examining related literature and film, the students each wrote a blog post that facilitated a group discussion during class time. “I really, really enjoyed the structure of the class, because it allowed me to fully immerse myself and understand the material,” says Nika Sadeghi, C’26. The small seminar size also gave each student more “airtime,” she says. “We got to where we embraced that opportunity to put yourself

For their final project, students selected a river and wrote its biography, deciding how they wanted to organize their histories, and then finding and interpreting resources, but, says Kanbayashi, “also trying to be critical of them or maybe asking a question that is different.” Sadeghi focused on the Ganges River in India. “It is a huge cultural symbol, and it has great meaning in Hinduism, but it’s one of the most polluted rivers in the country,” she says. “I was really excited to explore that juxtaposition.”

Beyond looking at ways humans and rivers have interacted in the past, Kanbayashi also addressed new issues related to climate change, given that this generation of students will be faced with a range of environmental issues—no matter what path they end up taking.

“One of the easy takeaways about history is that it offers a lot of lessons in humility,” Kanbayashi says. “But there are lessons of success and hope as well.” While studying the Bengal Delta, for example, they learned about people there who move constantly among islands that are formed and reformed when the rivers shift course.

“Thinking about how people live amidst changing environments is becoming more critical with climate change. But that’s something that has always been the case,” Kanbayashi continues. “The stories we can tell are not just of hubris. There are all sorts of stories of adaptations as well. We need to resist master narratives and bring a multiplicity of perspectives.”

Rivers aren’t just bodies of water that flow through environments where people live, Sadeghi adds. “They are multifaceted and have so many different roles and purposes for communities, individuals, states, and countries. We’ve learned how rivers can create enormous distress by flooding or by being dammed. The reverse can be true, too; they can be used for development or be religious symbols. Before this class, I never thought about the pivotal presence rivers can have in global conflicts and in global resolution.”

Omnia Associate Editor Susan Ahlborn has worked as a communications professional in healthcare and academia, and loves learning cool things and writing about them.

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

IN THE CLASSROOM

15

Sound Solutions Sound Solutions Sound Solutions

Researchers across Penn Arts & Sciences are turning to sound for new answers to questions on subjects from birdsong to the benefits of music exposure.

By Laura Dattaro

Illustrations by Maggie Chiang

Deep in the waters of the Indian Ocean is a system of underwater radar discreetly listening to its environment. These “listening stations”—intended, in theory, to monitor government activity—are shrouded in mystery; it’s possible they aren’t even real. But when Jim Sykes first heard about them, he was struck by the message the very idea of them sent.

“It’s very hard to confirm that these radars exist. Mostly it’s just rumors and promises, though probably some do exist,” says Sykes, an associate professor in the Department of Music. “But by announcing the

intent to use this kind of system, one government is signaling to another, ‘We’re listening to you.’”

Hearing, rather than seeing, is the surveillance medium of choice, he adds, showing that in some cases, “governments believe sound is a better way to access the truth.”

Today, across Penn Arts & Sciences, a similar sentiment about the power of sound fuels researchers and students in disciplines from music history to neurobiology who are using it as a lens to understand the world. They’re tracking the movements of fin whales and the behaviors of songbirds. They’re building algorithmic ears and musical video

games. And through it all, they’re demonstrating that sound is central to language, communication, history, and culture.

Most of their work fits collectively under the umbrella of “sound studies,” a term first coined in Jonathan Sterne’s 2003 book The Audible Past to describe a field that seeks to understand how sound shapes society. The book set off a flurry of interest in this space, Sykes says. And its publication happened to coincide with a new ability to digitize sound, making it ubiquitous, storable, and shareable. That environment amplified opportunities to look at sounds as worthy of study in their own right.

OMNIA | ALL THINGS PENN ARTS & SCIENCES

16

The “Fundamental” Importance of Sound

To study sounds, they must first be accessible. In 2011, that mission drove Al Filreis, Kelly Family Professor of English, to co-found the poetry archive PennSound.

Working with Charles Bernstein, a poet and professor emeritus at Penn, Filreis reached out to living poets and estate managers for poets who had died, asking to digitize any recordings they could get their hands on— sometimes trying for years, like they did with acclaimed 20th-century poet John Ashbery. Shortly before Ashbery died in 2017, his husband, David Kermani, finally agreed. Bernstein met Kermani at a diner, where he showed up with two plastic grocery bags full of cassette tapes—the only existing copies of Ashbery reading his works until PennSound digitized them.

So far, no one has said no to such records of their work, according to Filreis. And after 15 years, PennSound is the world’s largest audio poetry archive, comprising 80,000 individual files from more than 700 poets—all of them downloadable, for free.

The files in the archive are largely from live poetry readings, making them historical artifacts that retain not just the poem itself but also the sounds of a particular moment in time, down to the clinking of glasses at a bar. Filreis says it’s upended the way poetry can be taught.

When he was a student, for example, he remembers learning Allen Ginsberg’s iconic 1956 poem “America” by reading it from the thin pages of a bulky poetry anthology. It was in the same font as poets spanning centuries and styles. “It looked like every other poem that had ever been written,” Filreis says. But even as Filreis struggled with the words on paper, recordings of Ginsberg himself reading the poem—one a live version from 1955, upbeat and mischievous and before the poem was actually finished, another from a 1959 studio session, sorrowful and pleading—sat in the basement of a San Francisco poetry center.

Instead of that thin anthology page, Filreis’s students learn the poem by listening to both recordings. “They’re two completely different understandings of the tone and his relationship with America,” Filreis says. “There are still people thinking sound files are fun add-ons. I would contest that; they are fundamental.”

Exposure to Music

Mary Channen Caldwell knows from experience that sound is fundamental. Caldwell, an associate professor in the Department of Music, teaches a music class for students who aren’t majoring or minoring in music. Called 1,000 Years of Musical Listening, the course begins in the year 476 with the earliest notated Western music and ends with contemporary composers, including some currently working at Penn, like Natacha Diels, Assistant Professor of Music, Anna Weesner, Dr. Robert Weiss Professor of Music, and Tyshawn Sorey, Presidential Assistant Professor of Music.

Sound is a better way to access the truth.

Caldwell teaches the class almost entirely through sound. In the classroom and at home, students listen to the chants of medieval monks, French trouvère songs from the 13th century, operas from the 18th century. They must attend two concerts—the first time some of them have experienced live music—and Caldwell pushes the students to interrogate the ways in which historical prejudices and biases influence which music exists today.

The course’s textbook, for example, largely features white, male composers. Caldwell complements this narrative with extra readings that dive into music written and published by women and people of color, sometimes under

OMNIA | ALL THINGS PENN ARTS & SCIENCES

18

pseudonyms out of necessity.

“Knowing that is important and helps you be a better consumer of cultural products,” Caldwell says.

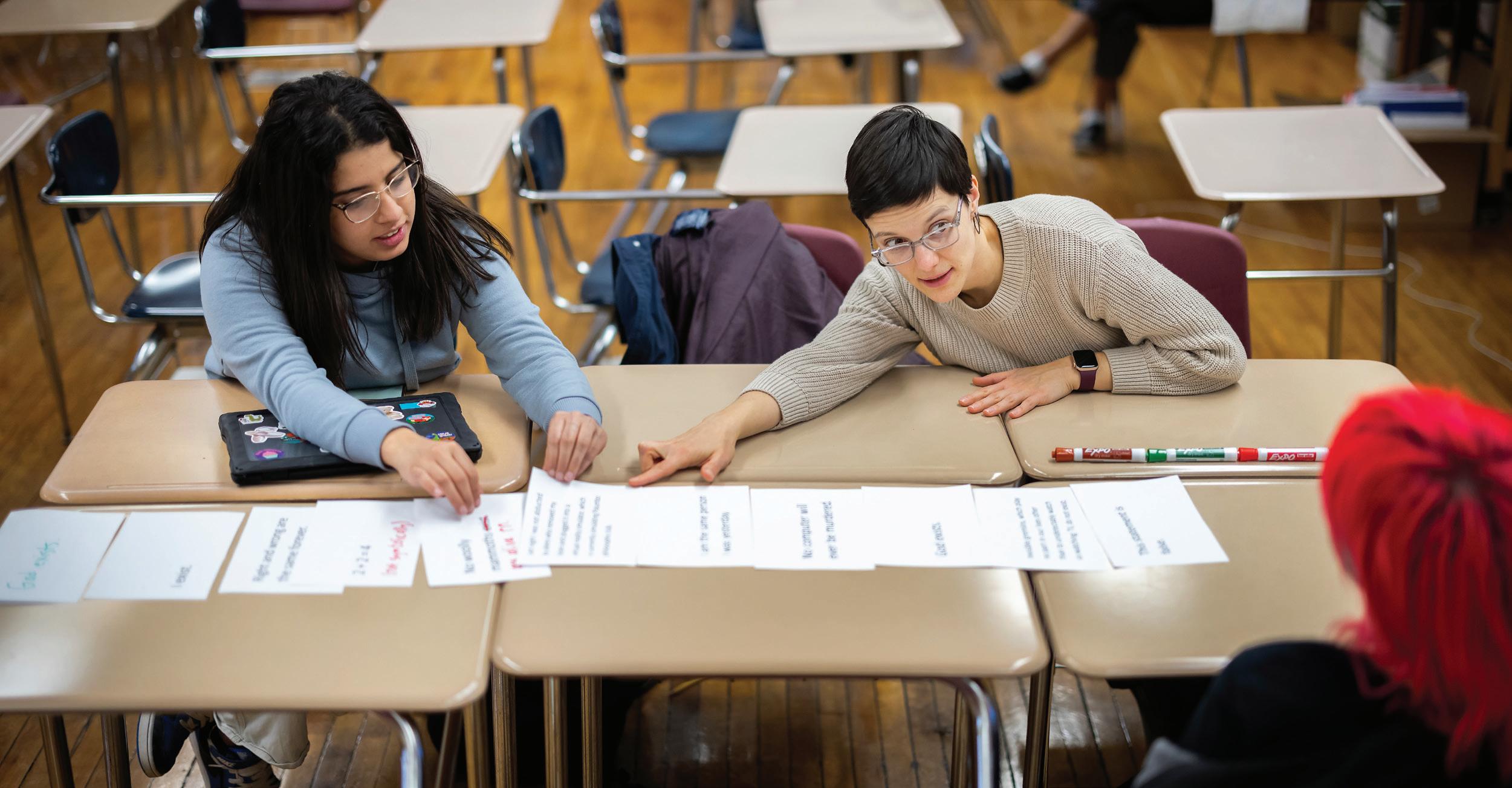

Exposure to music can also encourage the development of language itself. That may be, in part, because language has its own melodies and rhythms. And those melodies and rhythms, known as prosody, can change how people interpret and understand words, says Jianjing Kuang, an associate professor in the Department of Linguistics. “We’re like composers in real time,” she says.

Adults with greater musical proficiency often excelled at language and reading in childhood; Kuang wants to understand why the brain links the two, in the hopes of creating music education programs that can support language development.

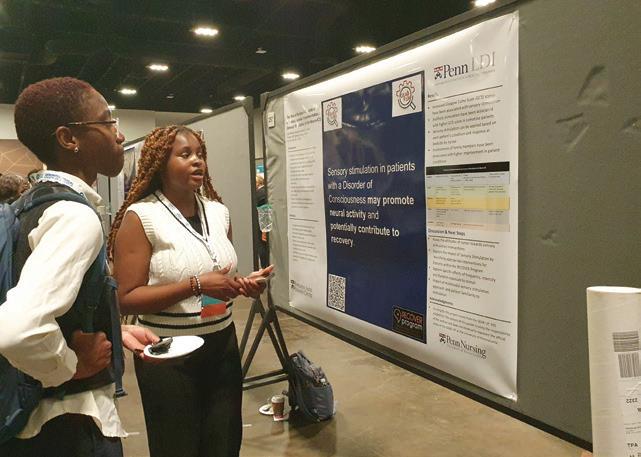

To probe this question, Kuang, her graduate students, and several undergrads developed a video game featuring a musical elephant named Sonic. Children playing the game press keys along with Sonic’s rhythm or guess which instrument Sonic is playing. During the summer of 2023, Kuang brought laptops loaded with the game to a camp and scored how the children did. She and her students then tested the children’s language abilities by asking them to act out and guess emotions.

Early results suggest that younger children who do better with the musical games also have higher language abilities. But in older children—around age seven—the differences are less stark, suggesting that the brain finds multiple ways to get to the same end result of language. “There is not one

path to achieve language development,” Kuang says. After all, she adds, some people are nearly “tone deaf,” unable to sing or identify a pitch, but can speak just fine.

“Language is so central in our daily life,” Kuang says. “If you want to understand our social behavior or cognition, language and speech are core.”

Language Development and the Cowbird

Sometimes this is true even for animals, like the songbirds biology professor Marc Schmidt studies. Research has shown that unlike most animals, songbirds learn to vocalize in similar ways as people do, by listening to the

19

20

adults around them and receiving audio feedback from their own speechlike sounds. That makes them an excellent model for understanding the neural pathways behind speech development, Schmidt says.

Language is so central in our daily life. If you want to understand our social behavior or cognition, language and speech are core.

Songbirds—a category that includes crows, cardinals, cowbirds, warblers, and robins, among others—make up almost half of all bird species on Earth. All birds vocalize to some degree, but songbirds use more complex patterns called songs.

In an outdoor “smart” aviary behind the Pennovation Center, Schmidt studies the songs and behaviors of 15 brown-headed cowbirds. One song in the male cowbird’s repertoire is nearly identical each time it’s sung. In fact, it’s one of the most precise behaviors in the entire animal kingdom, Schmidt says. “If you want to understand how the brain controls behavior, you want to choose a behavior that you can really rely on,” he adds.

The song is exceedingly complex to produce. Songbirds vocalize by pushing air through an organ called a syrinx, which sits at the juncture of the trachea, splitting into a V shape and connecting with the left and right lung. By alternating airflow between the two sides, the songbirds produce intricate, continuous notes. The male cowbird can switch sides every 25 milliseconds, indicating “incredible neuromuscular control,” Schmidt says.

Some birds are better at this than others, and Schmidt has found that female cowbirds pick up on quality. A female listening to recordings of the song will dip into a dramatic posture of approval, tilting her chest forward and raising her head, wings, and tail feathers—but only if she decides the song is coming from a worthy male. The male cowbird, on the other hand, changes his posture depending on whether his audience is another male or a female, puffing his feathers and spreading his wings for the former, holding completely still for the latter.

By recording activity from the muscles involved in breathing, Schmidt discovered that staying still actually requires more

energy for these birds. These subtle behavioral changes suggest that when the brain processes information about sound, it takes in more than just basic features such as frequency and loudness. It also considers the social context in which the sound is heard.

“You cannot understand behavior in a vacuum,” Schmidt says. “You have to understand it within the behavioral ecology of the animals.”

Using Sound to Understand How We Learn

To study this behavior in a more natural context, Schmidt has partnered with colleagues to develop a chip that could be implanted in a bird’s brain to record activity continuously. One of his collaborators is Vijay Balasubramanian, Cathy and Marc Lasry Professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

Balasubramanian, a theoretical physicist with a curiosity about biology, once wanted to understand learning so he could build more intelligent machines. Today his interests are more fundamental: He wants to understand how animal brains learn from their environment, and he is using sound to do it.

Animals, Balasubramanian points out, learn incredibly efficiently. A brain runs on about 20 watts of power—less than a single living room lightbulb. Training one large language model of the kind on which ChatGPT runs, on the other hand, requires more power than 1,000 households use in an entire year. What’s more, a brain can learn largely on its own, whereas an artificial intelligence model typically requires humans to manually label objects first.

How brains manage this self-directed learning is one of the big questions in behavioral and neural science, Balasubramanian says.

21

In a crowded room filled with noise, a person’s brain can pick out distinct sounds—say, her name— from the background cacophony. This phenomenon is known as the “cocktail party” effect. But how does the brain actually distinguish one sound “object” from another?

Balasubramanian theorizes that a sound object can be defined by two features that change over time: coincidence and continuity. Coincidence describes features of an object that appear together. In a visual object, such as a book, coincidence would describe how the edges of the front and the back covers coexist. Continuity describes how the edges move in concert if the book gets flipped over. For a sound, temporal continuity might mean the way pitch changes as a person speaks.

To understand how the brain uses this information to identify a sound, Balasubramanian, postdoctoral fellow Ronald DiTullio, GR’22, and Linran “Lily” Wei, C’25, are studying vocalizations made by people, a type of monkey called a macaque, and several species of birds, including the blue jay, American yellow warbler, house finch, great blue heron, song sparrow, cedar waxwing, and American crow.

Wei and DiTullio developed a machine learning model that mimics the cochlea, the hair-lined cavity of the inner ear that makes the first step in auditory processing: The hairs vibrate in response to sounds, sending signals along a nerve directly to the brain. Instead, Wei and DiTullio use an algorithm to extract certain features from the responses of their model cochlea—changes in frequency, for example— then a simple neural network uses those features to guess the sound’s origin.

The team has found that frequencies that change slowly over time are sufficient to distinguish among species. They can also differentiate vocalizations from individuals of the same species, as well as different types of sounds, say friendly coos or angry grunts.

To Wei, the model is a way to break down auditory processing into its most basic parts. “One thing I’ve learned from physics is that simplification is a virtue,” Wei says. “We have very complicated theories about how our auditory system might work, but there should be a simpler way.” These studies take a step in that direction, she adds.

Learning from Fin Whales

Even more complex than bird, macaque, or human auditory systems are those of marine mammals, who use sounds not only to communicate but also navigate. A single fin whale—the second largest whale on Earth—can make nearly 5,000 calls every day and can produce sounds up to 190 decibels, as loud as a jet taking off from an aircraft carrier.

To grasp how a fin whale might react to, say, the construction of a wind farm, researchers first need to know the animal’s typical behavior, says John Spiesberger, a visiting scholar in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science. Of course, “you can’t interview a fin whale,” he says. And spotting one visually is also serendipitous; they dive deep and can stay under for 20 minutes. Instead, researchers often track the whales’ movements by following their sounds.

The files in the archive are largely from live poetry readings, making them historical artifacts that retain not just the poem itself but also the sounds of a particular moment in time, down to the clinking of glasses at a bar.

The process is similar to the way a smartphone knows its location. A phone measures the difference in signal arrival times between pairs of broadcasting GPS satellites, then uses the differences to calculate its location. Similarly, researchers drop into the water receivers that pick up whale calls, then calculate the whales’ locations from the differences in the times the calls arrive at the receivers.

But the process doesn’t work exactly the same underwater as in the air. The atomic clocks that GPS satellites carry and the speed of the GPS signal both

OMNIA | ALL THINGS PENN ARTS & SCIENCES

22

precise locations.

In the ocean, though, it’s much murkier, in part due to inexact receiver locations and clocks that can be off by minutes. In recently published research, Spiesberger showed that estimates of a whale’s location using the GPS technique can be incorrect by up to 60 miles.

For decades, he has been developing new methods to reliably locate sounds in the face of these errors and use the improved techniques to survey whale populations. There is often no way to identify an individual whale from its call. That means 100 fin whale calls could originate from one, seven, or even 100 whales. Spiesberger’s methods yielded a surprising result: The reliable locations made it possible to compute the fewest number of whales heard.

That information could help researchers better understand how whale populations respond to environmental changes, says Joseph Kroll, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy and Spiesberger’s collaborator since the 1970s, when they were both studying at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “It doesn’t

looking for these animals to count them,” Kroll adds. “We want to know what’s happening to these populations.”

A Field Expanding

Spiesberger’s research is a clear demonstration of the ability to learn about a creature through the sound it makes, a principle underlying the work of just about all of the sound study happening across Penn Arts & Sciences. For Jim Sykes, the sound studies researcher, the next step is applying this principle across human cultures more broadly.

About a decade after sound studies became more established, a growing sentiment started to develop: The field had focused too much on people in the West. New branches of inquiry emerged, including Black sound studies and Indigenous sound studies. That’s the subject of Sykes’s book Remapping Sound Studies, an anthology he co-edited with Princeton’s Gavin Steingo that suggests a global model for studying the ways sound contributes to cultural and technological development.

Sykes conducted his dissertation research in Sri Lanka, around the time its 26-year civil war ended in 2009. He was interested in the way the sounds of war—beyond militaristic bangs of gunfire and bombs—shaped the experience of the country’s citizens.

He found that for many, sound defined both their day-to-day lives and their long-term memories of the conflict. They might notice, for example, that the playground yells of schoolchildren shifted to a different time of day or location as the education system tried to adapt to eruptions of violence. They might hear soldiers stopping cars at checkpoints, or a mother yelling her son’s name outside of a prison.

“That should be included in thinking about the sounds of war,” Sykes says. “Yet somehow, if you’re just focusing on military equipment, that gets left out.”

It’s a sobering example of the way society can be experienced, and thus understood, through sound. Sound is, after all, everywhere. It fills homes and cities, connects people to one another and the world, drives animal behavior and ecosystems. It’s one of the key ways a brain learns about the environment in which it finds itself. That means researchers tackling just about any question can potentially find a solution in sound.

Laura Dattaro is a New Jersey–based freelance science journalist who writes about the brain, genetics, and physics, among other topics. She has written for many outlets, including Columbia Journalism Review, Quanta, Spectrum, and The New York Times.

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

23

Catalysts for Basic Science sts

P. Roy Vagelos, C’50, PAR’90, HON’99, has been connected to Penn for 75 years, starting as an undergrad. He and his wife, Diana T. Vagelos, PAR’90, recently gave Penn Arts & Sciences $83.9 million to fund science initiatives—the largest single gift ever made to the School.

By Ava DiFabritiis

| ALL THINGS PENN ARTS & SCIENCES

Tommy Leonardi

24

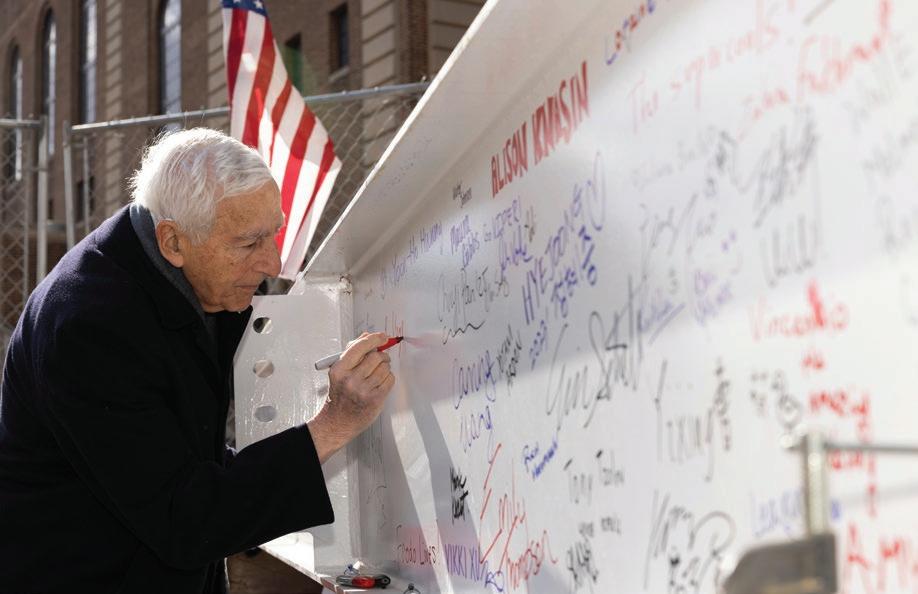

In January 2024, the University announced that P. Roy Vagelos, C’50, PAR’90, HON’99, and Diana T. Vagelos, PAR’90, made a gift of $83.9 million to fund science initiatives across the School of Arts & Sciences—the largest single gift ever made to the School and among the largest in Penn’s history.

This transformative gift includes $50 million to enhance graduate education in the Department of Chemistry, including funding 20 Vagelos Fellows. It also establishes a permanent endowment for the Vagelos Institute for Energy Science and Technology. To bolster excellence in chemistry research and teaching, the Vageloses have also directed a portion of the gift to fund their seventh endowed professorship at Penn Arts & Sciences. In addition, the gift is funding student awards honoring leaders of three undergraduate programs that carry the Vagelos name: the Roy and Diana Vagelos Program in Life Sciences and Management, the Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research (VIPER), and the Roy and Diana Vagelos Scholars Program in the Molecular Life Sciences.

The Vageloses’ longtime support of Penn Arts & Sciences now totals $239 million and represents an extraordinary investment in innovation and basic science.

“This monumental new gift caps off the incomparable impact that Roy and Diana have had on scientific research and education at Penn Arts & Sciences,” says Steven J. Fluharty, Dean and Thomas S. Gates, Jr. Professor of Psychology, Pharmacology, and Neuroscience. “From supporting and recruiting exceptional chemists to educating future experts in top-notch research facilities and interdisciplinary undergraduate programs, we will continue to make great strides thanks to the partnership and incredible generosity of Roy and Diana.”

The campus that welcomed Roy seven decades ago as an undergraduate has experienced vast transformation—shaped in no small measure by the visionary involvement of the Vageloses.

A Passion for Science Ignited

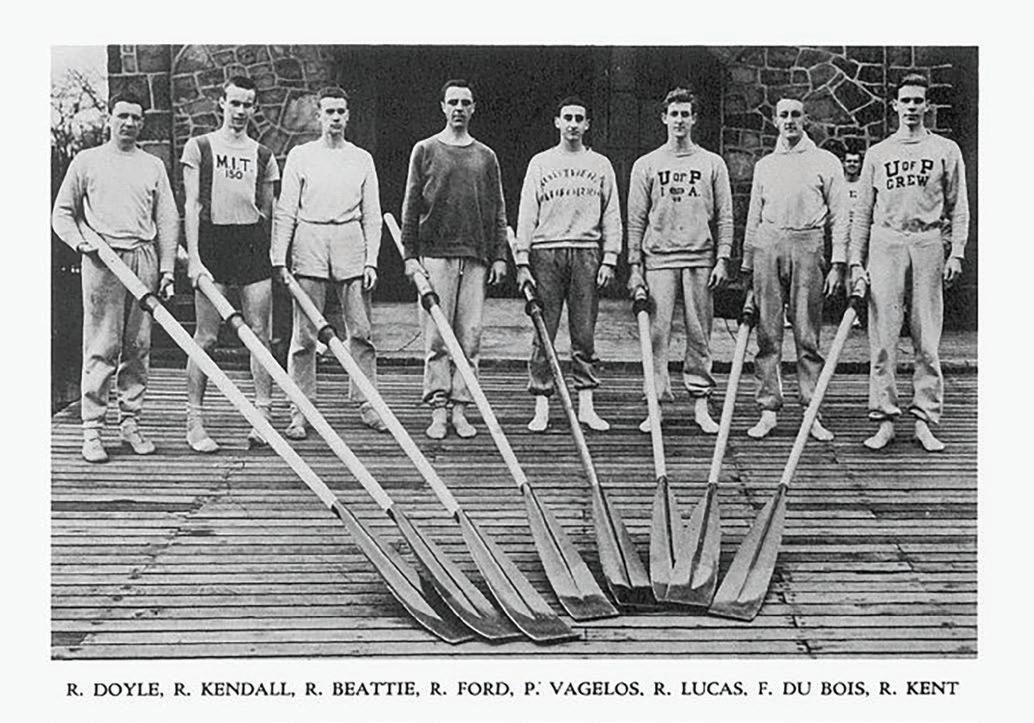

Roy Vagelos’s noteworthy career began at Penn as a chemistry major. Following his graduation in 1950, he completed his medical degree at Columbia University. As a physician-scientist at the National Institutes of Health, he discovered a key protein in the process of lipid metabolism. He spent nine years as chair of the Department of Biological Chemistry at Washington University in St. Louis. He joined Merck & Co. as Senior Vice President for Research in 1975, later becoming CEO and leading the company through a period of stunning innovation. He is best known for leveraging Merck’s discoveries to address health needs in the developing world. During his tenure, Merck made the breakthrough drug ivermectin freely available with the goal to eliminate river blindness globally.

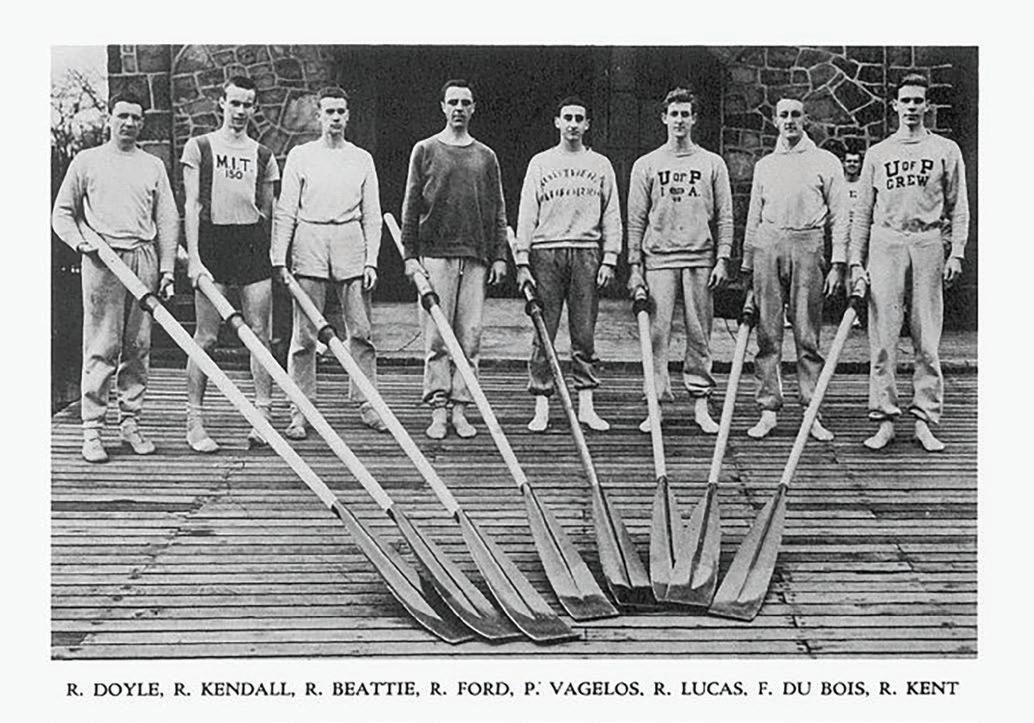

The connection to Penn that he formed as a top chemistry student and rower burgeoned when he became a proud Penn parent and later Chair of the Board of Trustees—a position he held from 1994 to 1999. As founding Chair of the Committee for Undergraduate Financial Aid, he galvanized support for student aid, and he and Diana personally established scholarships that support more than 20 students in the sciences every year.

Ava DiFabritiis, C’13, associate director of stewardship for Penn Arts & Sciences, is a frequent contributor to Omnia.

SPRING/SUMMER 2024

(Top to bottom) Roy Vagelos, fourth from right, rowed on the lightweight crew team during his time at Penn; Roy and Diana Vagelos with recipients of their two endowed scholarships, the Vagelos Endowed Scholarship in the Molecular Life Sciences and the Roy and Marianthi Vagelos Scholarship.

Courtesy of The Record ; Ben Asen

25

Fueling

Innovation and Discovery

From his time at Washington University in St. Louis in the 1970s, Roy knows firsthand that innovative and intellectually curious scholars are essential to the success of research institutions. He and Diana have strengthened Penn’s faculty through seven endowed professorships in the sciences, provided substantial support for graduate education—a recognition of the critical importance of training the scientists of the future—and created a hub for interdisciplinary collaboration in the Vagelos Institute for Energy Science and Technology.

Cementing the future of energy research at Penn, Roy and Diana made a spectacular investment to construct a dedicated home for the Vagelos Institute and VIPER. The Vagelos Laboratory for Energy Science and Technology will be an essential incubator for scientists and engineers to collaborate on sustainable energy solutions.

VAGELOS GRADUATE FELLOWS

With a substantial portion of the recent gift from the Vageloses—$50 million—being utilized to enhance graduate education, the Chemistry Department will begin admitting Vagelos Fellows this year, building to 20 named fellows.

“Supporting talented graduate students and bringing them together with the best faculty is the most promising path to breakthrough discoveries,” says Fluharty, “addressing not only the challenges that are facing us today, but ones that we have not yet imagined.”

THE VAGELOS INSTITUTE FOR ENERGY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Through founding support from Roy and Diana, the Vagelos Institute for Energy Science and Technology launched in 2016, positioning Penn as one of the premier energy research and technology centers in the nation. Today, it engages more than 35 faculty from across the University, along with postdoctoral fellows and graduate students. The recent gift from the Vageloses establishes a permanent endowment for the Institute.