Letter from the the Editor

By Jane Montalto Montalto

By Jane Montalto Montalto

Snow days feel harder to come by as we’ve grown older. I’m not sure if it is because they have lost their sparkle, or, more likely, because of the climate doom we live within. When the campus alert was sent out announcing school’s closure for February’s snow storm, I screamed out with immense joy. I was sitting in The Press office with some of the editors. We were all waiting for that text, silently hoping for a moment of reprieve from the never-ending workload of our classes.

Getting a text is so simple. In elementary school, I would wake up early and stay glued to the TV screen as the names of closing schools would scroll across the bottom. If you missed your school, you would need to watch the entire cycle through again. In middle school, I would be constantly refreshing my school district’s Twitter page — sorry, I still can’t call it X — late at night, awaiting a closure alert with the same anxious feeling. That same excitement from my childhood squirmed out when we got that text in February. I’m grateful for that moment of childlike joy as we inch closer to commencement, where it feels like it will be time to commit to adult life forever. It is nice to let those moments peek through.

I think whenever I’m writing these letters, it is quite hard for me to imagine a reader — I guess in this case, that reader is you. An almost-complete undergraduate education in journalism has taught me a lot, but it has also left me with complicated thoughts on going forward into a career as a journalist. Oftentimes, I wonder if people even read these editor’s letters — sometimes I don’t blame them if they don’t. But throughout my years in college spent here at The Press, print journalism feels alive and well. I know that print still has a seat at the table, I’ve seen it with my own eyes — and no, I’m not only talking about the pilgrimage I took with a friend to the local Barnes & Noble to pick up the Kristen Stewart Rolling Stone issue … but I guess that counts too.

Even though it is hard for me to imagine people reading our magazine, I know it is happening right under my nose. I take note of the huge stacks of magazines I stock in the library and notice it dwindle throughout the course of the week. I’m surprised by how quickly they all vanish. I don’t mean this to wax poetic or stroke our own egos either. Maybe this is just the impending doom of a graduation day talking. I guess what I’m trying to say is — without being too much of a cheeseball — thank you, to whoever is reading this. Even if you set it down after the first page, or read each issue religiously, or only pay attention to the fun, colorful layouts like we are your own student-run edition of Cocomelon. You continuing to pick our magazines up gives us a reason to be what we are today. Without you reading this, we would have no reason to exist.

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS

Executive Editor Managing Editor Associate Editor Business Manager News Editors Opinions Editors Features Editors Culture Editors Music Editors Science Editors Satire Editor Lead Copy Editor Multimedia Editors Graphics Editors Ombud Team Jane Montalto

Cruvinel

THE STONY BROOK PRESS MARCH/APRIL 2024

Rafael

Samantha Aguirre Antonio Mochmann Sydney Corwin Anjali Vishwanath Elene Mokhevishvili Ivan Vuong Leanne Pastore Kaitlyn Schwanemann Liam Hinck Ali Jacksi Marie Lolis Aman Rahman Jessica Castagna Kaan Ozcan Sophie Beckman Layne Groom Naomi Idehen Antonio Mochmann Allison Luna Naomi Idehen Ivan Vuong Lauren Canavan

PRESS The Press is located on the third oor of the SAC and is always looking for artists, writers, graphic designers, critics, photographers and creatives! Meetings are Wednesdays in SAC 307K at 1 PM and 7:30 PM. Scan with Spotify to hear what we’ve been listening to lately:

JOIN THE

On Nov. 2, Stony Brook University (SBU) student and Undergraduate Student Government (USG) Senator Sarah El Baroudy posted an Instagram story of her vandalized car. In red paint, her door read, “terrorist” and “go to hell.”

In the wake of the Oct. 7 attacks — in which Hamas, a Palestinian militant group, launched an invasion of Israel and killed over 1,200 people — the situation in Gaza has escalated dramatically. Israel has since killed over 30,000 Palestinians, according to the Palestinian Health Ministry. In the United States, the violence has been the source of political tensions between supporters of Israel and Palestine on college campuses, and their respective school’s leadership.

At SBU, pro-Palestine students like El Baroudy say they are facing an onslaught of discrimination and disregard — and that the administration has done nothing about it.

Shortly after El Baroudy posted the video of her vandalized car, an alert was sent out via email to notify students that the University Police Department (UPD) was investigating a possible on-campus “bias incident.” El Baroudy followed up with another Instagram story, in which she clari ed that the incident was a distasteful

joke played by a friend, who she did not identify by name.

“Regardless, this brought attention to the fact that Islamophobia runs rampant on our campus and it needs to be recognized and addressed,” El Baroudy wrote in her Instagram story.

An email from SBU President Maurie McInnis condemning the “erroneous report of a bias crime,” was sent out that evening.

“While ultimately UPD determined that in this case no bias incident occurred, let’s use this opportunity to remember that demonizing those with whom we disagree poses a threat to our core values of learning, respect and the value of dialogue,” McInnis wrote in the email.

El Baroudy reposted McInnis’ email to her Instagram story and

accused McInnis of victim blaming. “You can hear the Islamophobia in her words,” El Baroudy wrote.

UPD ultimately concluded that no bias crime had been committed, and no further actions were taken by the university administration or El Baroudy. However, the damage had already been done. Students have expressed disappointment in McInnis’ lack of response to the ongoing bloodshed in Gaza, and the widespread reports of Islamophobia on college campuses across the U.S.

On Oct. 10, McInnis uploaded an Instagram post condemning Hamas’ attacks and “other crimes committed in Israel.”

Yaseen Elsayed, a sophomore at SBU, commented on the post, “Does the university have anything to say about Israel cutting electricity, fuel, food and water to over 2

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 2

Photos by Allison Luna

million civilians, 40% of whom are children, in the name of ‘ ghting terrorism?’”

A few weeks later, Elsayed received a direct message on Instagram from an SBU alum threatening to send his future employers or potential graduate schools evidence of his support for Palestine.

“Just letting you know that wherever you gain employment in 2.5 years time, I will be reaching out with screenshots to evidence your support for Hamas and terrorism,” the alum wrote.

Speaking out in support of Palestine has cost people job o ers. Moreover, many were agged by organizations like Canary Mission — which posts peoples’ names and photos alongside accusations of antisemitism, often with little evidence other than ties to Students for Justice in Palestine chapters, or attendance at pro-Palestinian protests and rallies. Still, Elsayed

says he’s not afraid to voice his discontent with Israel’s violence against Palestine. He wants his university’s administration to speak up.

“We’ve seen from the administration statements of solidarity for what happened on Oct. 7, but we haven’t heard anything about what’s happened since then,” Elsayed said. “I’m sure there are Palestinian students on campus who are in need of that solidarity right now.”

SB4Palestine, a coalition of SBU students that is not o cially a liated with the university, held an on-campus memorial on Nov. 20 for Palestinian martyrs killed by Israeli forces. The memorial’s intention was to provide students with the solidarity Elsayed spoke of, organizers said.

Iman Hayee, a senior at SBU and an organizer of SB4Palestine, said UPD ofcers were heard laughing and making jokes while supervising the memorial. Meanwhile, she saw students crying in fear for their family members, who live in the Middle East

and are threatened by the violence.

Coalition organizers say they’ve been followed and made to feel uncomfortable by UPD on several occasions. On Dec. 4, organizers held a demonstration during the last University Senate meeting of the year, held in the Wang Center Theater and broadcast on Zoom. They interrupted the agenda and gave speeches that accused the State University of New York system of complicity in the face of genocide against Palestinian people. Zubair Kabir, a sophomore at SBU and organizer with the coalition, said he was followed by UPD even after being escorted out of the University Senate meeting.

“It’s clear that [UPD] are here because they’re obligated to,

THE PRESS VOL. 45, ISSUE 3

and don’t feel any need to protect our students,” Kabir said.

UPD has not responded to requests for comment at this time.

The coalition, which is on track to become a recognized club a liated with the university by spring 2024, published an open letter to McInnis via Instagram on Dec. 16. The letter urged her to call attention to Palestinian issues — especially amid the resignation of University of Pennsylvania President Liz Magill, who faced pressure from do-

enous practices across the Americas and globally.”

Additionally, the coalition’s letter accuses the administration of trying to “police and silence” the organizers behind the SB4Palestine Instagram account. According to organizers, the administration initiated a UPD investigation into the account upon its inception, resulting in organizers clarifying in their bio that they are not a liated with the university, and changing their username from “sbuforpalestine.”

sentiment that multiple students have echoed.

Following the November shooting of three Palestinian college students in Vermont — leaving one victim paralyzed — students say that Stony Brook administration and UPD have fostered a hostile environment for Arab and Muslim students, which has left them feeling unsafe.

Students at other schools are facing similar hostilities. At Harvard University, trucks brandishing the names

nors and politicians who accused her of a tepid response to antisemitism on college campuses. The letter also targeted McInnis’ previous emails and cited their failure to “explicitly name the people currently facing genocide: Palestinians.”

“As Stony Brook celebrates the inauguration of the new Native American and Indigenous Peoples Studies minor, it fails to acknowledge the ethnic cleansing of Indigenous Palestinians from their land,” the letter reads.

SBU announced the launch of the minor program in an article published on Oct. 9, describing the curriculum as responsive to the “communities whose land the university occupies, and to the history of settler colonialism and Indig-

“We actually got a [direct message] from one of the deans saying that we’re not allowed to use the name,” Hayee said. “So we had to do an entire meeting about that … which is a little insane if you ask me.”

Namal Fiaz, a coalition organizer, said a university administrator sent the account a direct message three days after it was created, urging them to promptly remove any association with the university.

The letter alleges multiple anti-Islamic hate crimes swept under the rug by administration, but does not specify which. It calls on McInnis to take up her responsibilities as the university’s president and to condemn the Israeli aggression against Palestine — a

and faces of pro-Palestine students labeled “Harvard’s Leading Antisemites” were driven around campus. Columbia University, Brandeis University, George Washington University and several public schools across Florida have banned pro-Palestine groups altogether. In Florida, two of the largest universities in the state did not follow Gov. DeSantis’ order to deactivate Students for Justice in Palestine groups.

“The least we can do is raise awareness,” Hayee said. “And historically, campuses have been a place of activism and solidarity with liberation movements all over the world … we can’t be complacent.” g

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 4 NEWS

5 FEATURES THE PRESS VOL. 45, ISSUE 3

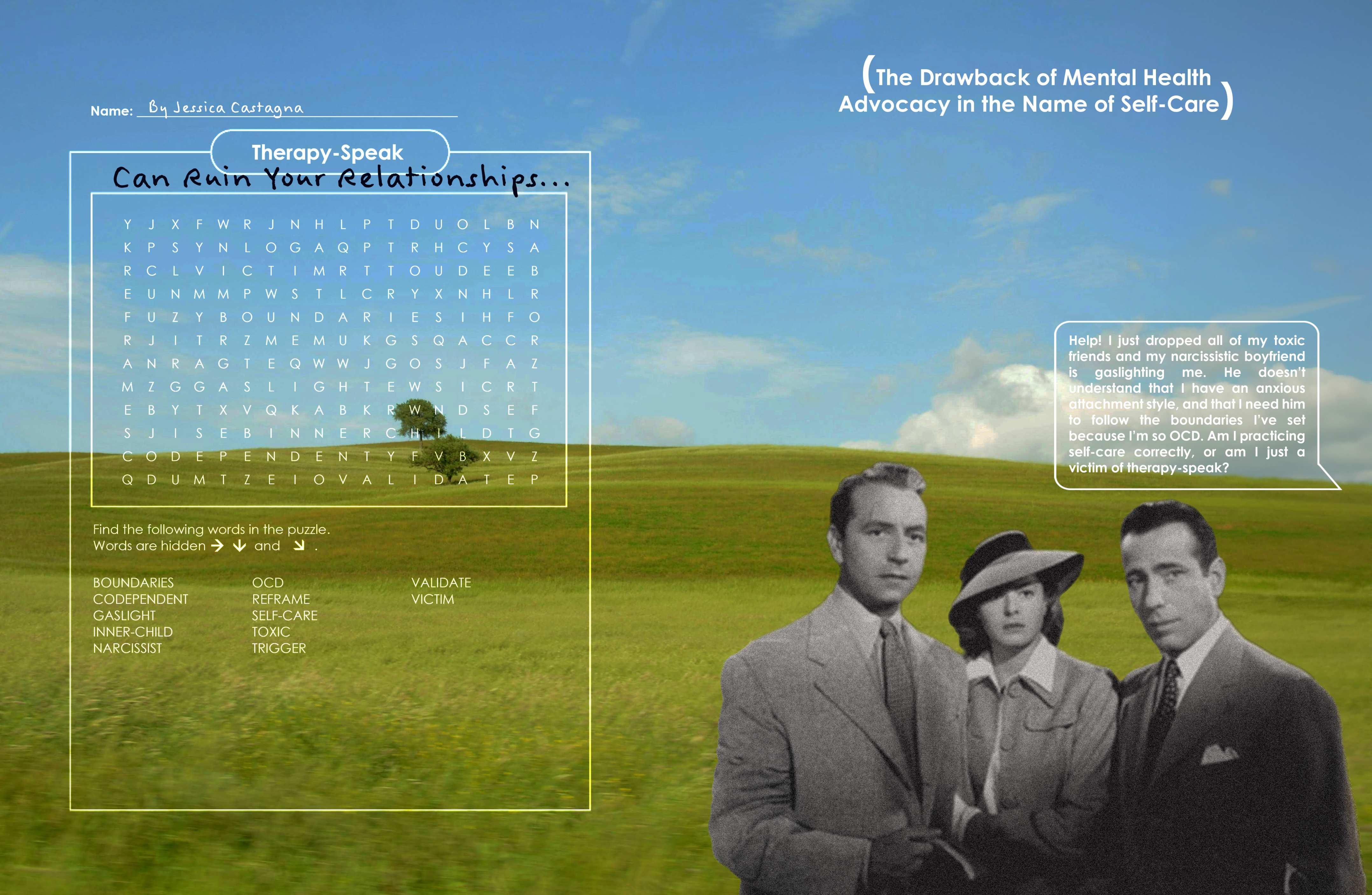

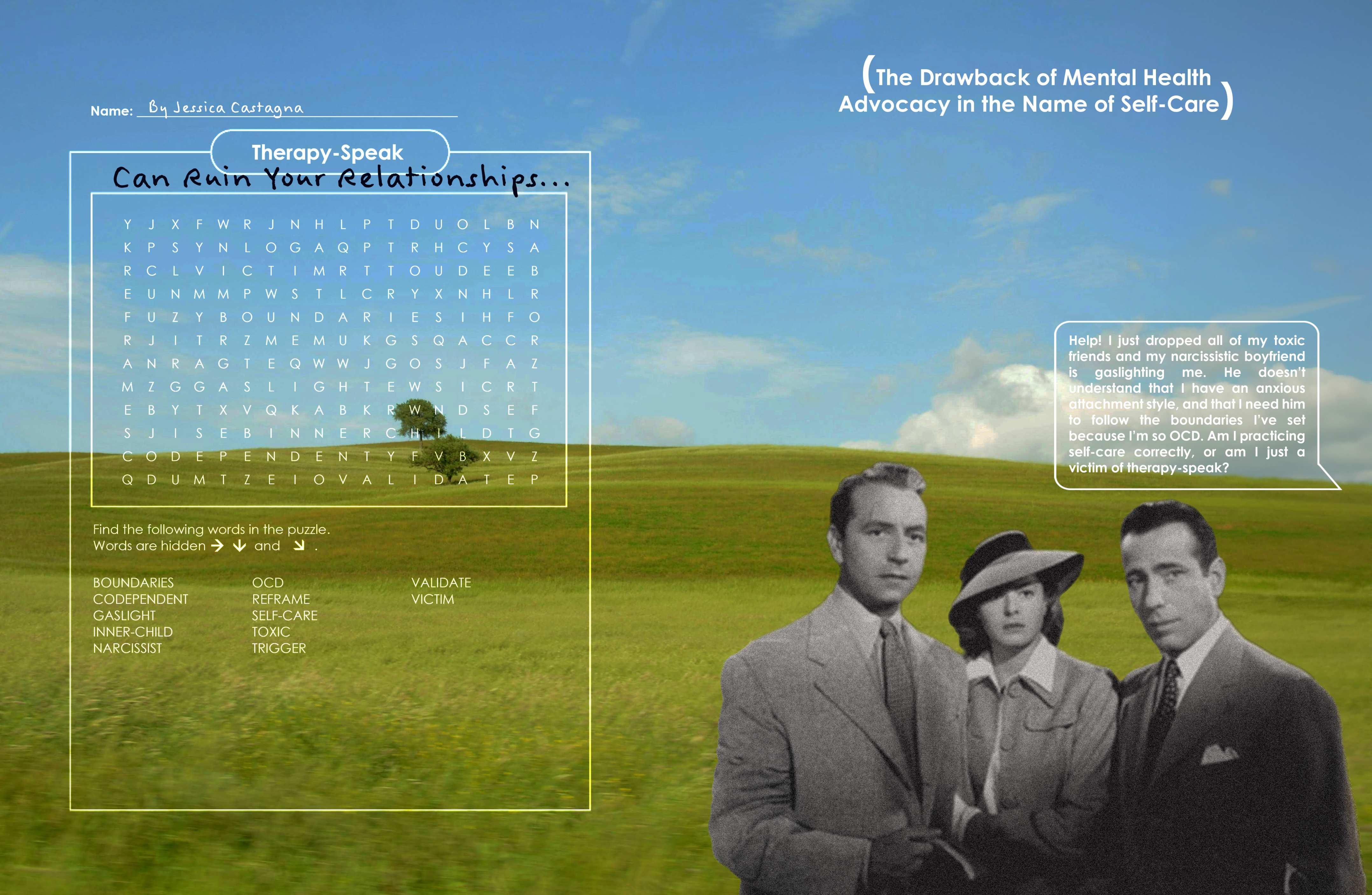

Help! I just dropped all of my toxic friends, and my narcissistic boyfriend is gaslighting me. He doesn’t understand that I have an anxious attachment style, and that I need him to follow the boundaries I’ve set because I’m so OCD. Am I practicing self-care correctly, or am I just a victim of therapy-speak?

Mental health advocacy is booming online. Licensed therapists and psychologists are growing roots outside of their brick-and-mortar o ces and into the digital world as TikTok therapists provide therapeutic advice to their followers. But, in the age of misinformation, what happens when psychological jargon is misused? What impact does this have on interpersonal relationships?

There is a term for this improper use of therapeutic language — coined as therapy-speak. The phenomenon occurs when prescriptive language, which describes behaviors or psychological conditions, is used improperly outside of therapy. The expansion of mental health advocacy has allowed people to more accurately describe their feelings, better communicate with those around them and ultimately nd the psychological support that they need. However, as a consequence of this expansion, more people have engaged in therapy-speak, which can open up a potentially destructive can of worms. Misunderstanding, and therefore misusing, this language can destroy relationships that could have been salvaged.

“Therapy-speakistheuse of clinical and psychological language in regular, day-to-day conversations, often outside of the context within which those words were meant to be used,” Israa Nasir, 36, says. Nasir is a mental health pro-

fessional, author and speaker residing in New York City who has amassed over 35,000 followers on TikTok. “An example of therapy-speak is when somebody might accuse their partner of gaslighting them, which is a very serious, emotionally abusive dynamic, when in fact, their partner was lying to them. So therapy-speak sometimes is weaponized, and intentionally or unintentionally.”

Christine Johnson, a 31-year-old therapist based in New Orleans, Louisiana, breaks down the larger notion of therapy-speak into two components. “One is the folding in of words into our general vernacular like ‘gaslighting’ or ‘narcissist’ that originated from the world of psychological sciences,” Johnson says. “The other refers to a speci c tone that relies on owery language to muddy the waters of what

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 6 FEATURES

someone is actually saying, often in an impersonal way.”

The terms and concepts associated with therapy-speak often require their users to fully comprehend them, and use them with careful consideration, to avoid sounding like a sanitized, cold and disconnected HR email. Self-help books and online mental health advocates can only provide a framework for handling situations that arise in personal relationships. Regurgitating prescriptive language without the key ingredients — human compassion and intellect — can lead to an unfortunate collapse of those relationships.

What does weaponized therapy-speak actually look like? In April, an article on Bustle — “Is Therapy-Speak Making Us Sel sh?” — examined some real-world examples of its destructiveness. In the article, a 24-year-old girl named Anna discusses how her lifelong friend abruptly ended their friendship over text.

“I’m in a place where I’m trying to honor my needs and act in alignment with what feels right within the scope of my life, and I’m afraid our friendship doesn’t seem to t in that framework,” the friend wrote. By using one-sided, vague language, Anna’s former friend left her in a position that closed the conversation from further discussion.

A more satirical example comes from Sabrina Brier, a comedian and TikTok public gure. In a skit, Brier acts as a friend who uses therapy-speak. When asked by the person behind the camera if she will attend a housewarming party the coming weekend, Brier responds in a satirical, dramatic example of how therapy-speak may feel for the person on the receiving end.

“To be radically honest, upon further re ection, it has come to my attention that I’m no longer able to spend time with your friend group because I nd them to be insu erable and, quite frankly, toxic,” Brier replies in an exaggerated, matterof-fact tone. “In order for us to spend more time together, it’s going to have to be one-on-one outside of them.”

“Therapy-speak is the death of proper communication,” reads a comment on Brier’s video. Other comments claim that she sounds like a robot.

Therapy-speak has been criticized for encouraging people to place their wants and needs over those of others. In actuality, relationships require much more tenderness than this black-and-white thinking. Therapeutic concepts like self-care and boundary setting are important for maintaining mental health, personal growth and healthy relationships, but real-life situations are far more nuanced. Relationships sometimes require sacri cing one’s own needs and wants when the other person’s are more serious or substantial.

Self-care and mindfulness can provide numerous bene ts — higher-quality sleep, boosted self-con -

dence, improved focus, stronger immune system and more stability when managing stressors. However, therapy-speak, and even self-care a rmations, can lead users down a dark rabbit hole. While constantly building up self-importance, someone may

7 FEATURES THE PRESS VOL. 45, ISSUE 3

also be — inadvertently or not — strengthening feelings of sel shness under the guise that the self is always the priority.

Nasir contends that while therapy-speak has helped expand emotional vocabulary, it has also harmed mutuality in relationships. “Mutuality is this concept of there being an ‘other’ in a relationship, so we grow in relation to others,” she explains. “The biggest task of a therapist is to help people see that, and help negotiate these things within healthy relationships. But this proliferation of social media and therapy-speak has incorrectly and erroneously taught us that mutuality doesn’t exist.”

Dr. Raquel Martin, a li- censed clinical psychologist and professor based in Nashville, Tennessee, posted a video to her TikTok account that explains the ne, but crucial di er- ence between a “rule” and a “boundary” in

personal relationships. “A boundary guides your behavior,” Martin says. “A rule guides someone else’s behavior.” She uses an example of two people engaging in a conversation, and one person raises their voice at the other. Martin says that telling the person to stop raising their voice would be considered a rule.

“A boundary would be more like, ‘When you raise your voice at me, I will not be engaging in that conversation,’” Martin says in the video. “He can keep on yelling, you’re not telling him not to yell. You’re not controlling his behavior. You’re saying what you are going to do in response to his behavior.”

A public example of this weaponized misunderstanding of boundaries came from actor Jonah Hill in July, when his ex-girlfriend, Sarah Brady, posted screenshots of their text messages to her Instagram story. In the messages, Hill demanded that Brady conform to the “boundaries” he set for their relationship. Among other things, Hill insisted that Brady — who is a surfer — needs to stop posting photos of herself in a bathing suit, and that she must not surf with men.

“He had a very strong preference for the way his girlfriend dressed,” Nasir says, in response to the Jonah Hill controversy. “But he used the term ‘boundary’ to communicate that. Boundaries are not meant to police other people’s behavior. People don’t understand that, and they kind of present their own preferences, or their own desires, or their own likes, or you know — what they expect out of the other person — and label that as a boundary.”

Why has the information age brought on this pervasive misunderstanding of therapeutic language? A possible explanation could be that the internet and social media made this language hugely accessible. People who cannot a ord therapy can now do their own research on mental health. Online resources — including a scroll through TikTok — have opened this once-closed door.

“I think that society has latched onto therapy-speak in this exaggerated way because there was a huge gap in our emotional vocabulary at a societal level, and also at an individual level,” Nasir explains. “So for a very, very long time, these concepts that people really feel — people do feel a lack of boundaries, people do feel like someone is overstepping, or people do feel like someone is emotionally abusing them — they don’t really have the language for it. For many, many years, this was all gate kept behind the doors of therapy. And if you couldn’t a ord it, you didn’t know it.”

People are hungry for more precise language to accurately describe their emotions or circumstances. This blending of diagnostic and therapeutic language into the vernacular allows for people to place labels on other people — or on their own feelings — as a form of catharsis, even if those labels are inaccurate. “In a world where our social and digital communication is shortening into smaller and smaller soundbites, it becomes important to nd communication shorthands,” Johnson says. “Labeling someone else as a narcissist, for example, creates a communication shorthand that immediately implies a level of severity that a description of traits and behaviors might not capture as easily.”

Amanda Stern, author of Little Panic and writer of the How to Live newsletter, was in therapy

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 8 FEATURES

for 23 years. “I can’t think of one time that my very excellent therapist ever used any of these words or expressions,” she says. “These terms help us locate the general area of di culty. It gives us a name or a phrase for the entire sentence that we lack. This word, this phrase, is a great place to start. But people don’t start there. They nish there.”

The existence of therapy-speak is an indicator that our society is moving in a direction that is far more conscious of mental health than ever before. Stern interprets the usage of therapy-speak as a signal: the user has either just started going to therapy, or they have just begun researching mental health conditions or self-care.

“It’s a double-edged sword,” Stern says.

Stern’s 2018 memoir, Little Panic, is a re ection on growing up with an undiagnosed panic disorder. “After I published Little Panic … I noticed how many people would con ate having anxiety with having a panic disorder,” she says. “People have this need to sort of heighten or embellish or exaggerate their struggles in order to be taken seriously, or in order to be heard. But that actually back res.”

Incorrectly self-diagnosing a mental health condition or falling victim to misusing a therapeutic buzzword creates a wall between a person and the personal or relational growth that they may be craving. While words like “gaslighting,” “trauma” or “narcissist” are not always used incorrectly, therapy-speak is a signier that someone needs to dig deeper, rather than block o further exploration with one word.

“If you’re overlooking the actual tools needed in which to access your emotions and articulate them, and you’re actually bypassing them, and in place of all that work, you’re just tagging things with a word to signify a larger issue, you’re not creating a deep and meaningful relationship,” Stern says. “You’re just creating a show of being very well read on the internet.”

How can

we avoid this harmful misuse of therapeutic language? Therapy-speak is an indicator that there may be more complex, nuanced emotions hiding below the surface of a buzzword that is being used. Instead of viewing that connection—with a particular phrase or term that is oating around the social mediascape — as an immediate x, view it as a means to beginning a self-discovery journey.

“I’d love to see a greater respect for the ways therapy language can help a person de ne their own experience and a greater caution for the harm it can cause when used to dene someone else,” Johnson says, while weighing the bene ts and drawbacks of therapy-speak. The key to using this language accurately might lie within mindfulness, conversation and careful consumption of information online.

“We need to become conscious consumers,” Nasir says. “We need to look at the credentials, we need to look at their training, we need to look at their overall messaging. More than anything … If you’re struggling, try to seek one-on-one care, because what’s happened is a lot of us think that this access to information is treatment itself, but it’s not.”

Because individualized care is sometimes inaccessible due to cost, Nasir encourages people who are struggling to nd a ordable therapy to explore every option. She suggests checking to see if there is a community clinic in your area, looking into group therapy — as it is usually cheaper than one-on-one — and asking therapists for a sliding payment scale based on income. “There are a lot of free community services provided around mental health care,” Nasir says. “It’s still not as good as one-on-one care, but it’s still better than just passively consuming information on the internet.”

Aside from taking mental health concerns directly to a therapist, therapy-speak can be used as a starting point for individual growth. “Everyone should say to themselves, ‘Say more,’” Stern says — her rule of thumb for engaging with therapy-speak. “Say more, get your own words. Trace it back to the root.”

While a singular term or phrase may feel fully-encapsulating of a person, emotion or relationship, that prescriptive language may not perfectly t the bill. Before hitting send on that break-up text to a friend who violated a set “boundary” at brunch, or whispering about a partner’s “narcissistic” tendencies behind closed doors, think twice. What colorful, multi-dimensional emotions are buried beneath that buzzword? Therapy-speak expands emotional literacy — it can help people identify serious disorders or legitimately dangerous relationships. But this language may require a warning label: use with well-educated caution, or else risk collateral damage to healthy communication and interpersonal relationships. g

9 FEATURES THE PRESS VOL. 45, ISSUE 3

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 10 FEATURES

“I went there, and it was everything I wanted. It was sweaty. It wasn’t dirty, but it [had] frayed edges, and I loved every second of it. Everybody’s super friendly. Everybody’s gonna have a good time.”

The walls of the small basement venue are scribbled with tags from bands who played in the past and fans. Phrases such as “Respect Existence or Expect Resistance” and “SUPPORT OUR LOCALS” encapsulate why The Cave was started — to give local artists a space to express themselves freely without fear.

On Nov. 11, 2023, four bands performed at The Cave, each with their own style of alternative rock.

Leaves crumpled under my feet as I walked toward the house. For a moment, I felt out of place, standing alone as a crowd formed. “I’m really scared,” I frantically texted my friend in a panic.

I stood in the dark backyard, waiting for the concert to begin as a blue glow poured from the open basement door. Regardless of how nervous I was, the warmth of the basement was inviting on such a cold evening. Plus, the friendliness of the strangers around me made me excited to descend into the concert with them.

That night I stepped into the depths of The Cave, one of Long Island’s hidden treasures. It may

The rst acts, The Knottie Boys and FEELSGOOD, brought a pop-punk vibe to the concert. They were then followed up by Pseudobliss and Ringpop! who both had an emo, shoegaze sound. Regardless of who was playing, the crowd moshed wildly in the ever-tightening space.

“You want to book the shows that you want to see,” Cameron Wustenho , The Cave’s sound technician, explained. “If you want to see energy at shows, you’ve got to make the energy.” Throughout the night, Wustenho was moshing with the crowd and singing along with the vocalists.

Wustenho is glad that The Cave’s

seem like just a dark, decrepit basement, but it’s a place that fosters the local punk music scene by providing smaller artists with a space where they can rock out and their fans can thrash.

Since its rst concert in January 2023, The Cave has created a dedicated community of concertgoers with monthly shows. The all-ages venue is located in Medford, but the address is only given upon request through Instagram direct messages or word of mouth. It creates an exclusive scene for those in search of one.

The Cave is for “anyone who’s ever dreamed of underground punk shows or basement shows,” concertgoer Connor McGlone said.

13 MUSIC THE PRESS VOL. 45, ISSUE 3

owner, also known as the Caveman, has helped to create a space for local artists to perform. “He really knocked it out of the park,” Wustenho said. “He made the kind of venue that most people in this scene want to see.”

The two knew each other in high school and found that they both were passionate about Long Island’s music scene.

“I saw that he was just doing shows, I knew bands and he needed a PA system,” Wustenho said. “Soweendedupbecomingfriends and booking as many shows as we could.”

The Cave gives musicians the opportunity to make a name for themselves and those interested in performing can apply on-

line from anywhere. Ringpop! and FEELSGOOD are from Boston and the Greater Philadelphia area respectively. In an April 2023 concert, the Cave welcomed Robot Civil War from Chicago and a May 2023 concert had Connecticut band rake re.

“I would say The Cave probably does the best at supporting the local scene, [more] than almost any other venue on Long Island,” Nikky Tannenbarf, bassist of The Knottie Boys, said. “It feels like anyone, whether you’re a little tiny baby band or an out-of-state band that is doing really good, he’s gonna let you come in. He’ll let you play with the bigger guys, and it feels good. It brings everyone together.”

Throughout the show, the crowd

moved and headbanged as the music blared. As one performance ends, the sweaty attendees reemerge into the cold air of the backyard to mingle while the next band sets up. Even in the condensed space, concertgoers were able to crowdsurf and push each other around. One of the walls reads “The Cave’s rule #1: When someone goes down you pick them up.”

Despite being in a place where anyone can seem like a stranger, everyone is united by their love for the space The Cave provides. When The Knottie Boys played “I Gotta Feeling” by the Black Eyed Peas, the audience screamed the lyrics. The Cave is an authentic hardcore show experience right in someone’s basement.

“It feels more approachable,” Wustenho said. “Anybody can

come to these shows and everybody ts in. ... It’s been really surreal watching this grow. It’s really been just the best time in the world.”

The Cave has big plans for this year. Following their one-year “cave-versary” in January 2024, they are looking to redesign the layout and make the venue safer by removing hazards such as overhead lights or anything that someone could crash into. They intend to book more bands to perform, all while trying their best not to annoy the neighbors.

As long as The Cave exists, Wustenho promises that they will put on as many cool lineups as they can, with hopes of hosting more than one show a month.

“We’ll probably do this until we’re dead,” he said. g

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 14 MUSIC

It is the 1980s: “Gay” is a dirty word, many LGBTQ+ stories are absent from mainstream media and same-sex marriage is illegal. A new disease — known rst as a “gay man’s pneumonia,” then as the “Gay-Related Immune De ciency Disorder” andnally as AIDS — is proving deadly. The abstract from a 1986 study deemed the federal response to AIDS to be “uncoordinated, insu cient and inadequate in particular with respect to the support of public health education and the nancing of health care for AIDS patients.”

It is the 2020s: Florida education policy blocks topics of sexuality and gender from schools, LGBTQ+ stories are disappearing from bookshelves, gender-a rming care is banned for youth aged 13 through 18 in 23 states, transgender people are being barred from sports teams, anti-LGBTQ+ extremism is on the rise and Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has mentioned revisiting Obergefell v. Hodges — the landmark Supreme Court case a rming the right to same-sex marriage in America. Revisiting it with the intent to overturn it would put the legality of same-sex marriage in the hands of states. At the university level, LGBTQ+ students are ghting against gender-segregated housing. In April 2023, freshmen students living in Stony Brook University’s Gender-Inclusive Housing (GIH) corridor in Wagner Hall sent a long, detailed email to Campus Residences. The email addressed inequalities transgender and gender non-conforming students experience in on-campus housing at Stony Brook. In addition to protesting the comparatively few GIH dorms, the students described the unsafe environment of the Wagner GIH corridor.

“Within the rst week of being at Stony Brook, a cisgendered man sexually assaulted one of our trans dormmates and the resulting events led to the survivor transferring out of the school while the led Title IX did nothing about the assaulter,” the students wrote. “Another case of sexual harassment includes a cisgendered woman accessing the code-protected, gender-inclusive bathroom and committing an act of indecent exposure onto two of the trans residents. On top of these incidents, the attitudes of our cisgendered peers who live right next to and walk through the GIH hall indicate a lack of respect; the people we shared a oor with had a history of misgendering and looking down upon the visibly gender nonconforming residents in the very space we were supposed to feel safe in.”

When the students met with a representative from Campus Residences, they asked for more GIH dorms and stronger protections for LGBTQ+ students to be added, especially those who choose to live in GIH. After the meeting, the school added a group of GIH suites near each other in Tabler Quad.

“I know that it’s not enough,” said Stony Brook sophomore Hayoung Song. “It’s like a bandaid to a bullet wound. It generally worked out as I had expected, but what I really wanted … [was] to set this precedent of asking for complete desegregation by gender, of at least suite style housing, because that’s the root of the issue.”

Song was one of the leaders of the group of students. He said that, while they mentioned the abuses which had taken place in the GIH corridor, and proposed increased screening of candidates for all-gender dorms to ensure applicants do not have ulterior motives for entering, he hasn’t seen much come of the meeting with Campus Residences. There is a ne line, he acknowledged, between protecting LGBTQ+ people in GIH and keeping the option accessible. Still, he invited more conversation on the topic, as he saw a lack of action from the university on the matter.

“I can attest to the fact that they just don’t … take GIH seriously,” Song said. “[In Wagner Hall’s all-gender corridor] we were one hallway surrounded by a hallway of cisgender women and cisgender men, and we faced a lot of covert transphobia from both of them, just having them in our space or passing by and looking at us while we were in the lounge and kind of just giving us that look, that look of disgust and annoyance that we were there. I was always on edge

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 16 FEATURES

because I didn’t know who was going to pass by our hallway, and who was going to give us dirty looks.”

Director of Campus Residences Jeffrey MiWe has been in charge for about two and a half years. In that time, the program has changed dramatically. The 2021-22 school year introduced the freshman GIH corridor in Wagner Hall.

“[The freshman GIH corridor] has typically been in the Benedict community, because Benedict has three bathrooms down [on the B0 oor where all-gender dorms are typically placed], which allow a more variety of privacy,” MiWe said. “So that can allow a student to have a single-use, or a shared-use bathroom depending on what their level of preference was.”

MiWe said that the Benedict B0 oor was unavailable last year due to isolation housing for COVID-19 and mpox.

“That was the rst time we placed it in the middle of a wing, whereas in the past, it had been on the ends of a wing,” MiWe said. “So I think that created some di erences in how the experience was. And so when that feedback came back in, we were like, okay, we’re denitely shifting this back down to Benedict B0 as the primary community.”

According to MiWe, the needs of the GIH community are constantly evolving. Currently making up 1.79% of the population of students living on campus, the number of students in all-gender dorms goes up every year. Over the years, the program has become much more accessible. MiWe explained that the program was not really advertised in the past, and interested students had to talk to the Director of Housing Administration at the time.

With the introduction of the freshman cluster,acommunityhasformedamong LGBTQ+ students at Stony Brook. Where their predecessors hardly knew of each other’s existence, LGBTQ+ students in non-gendered housing now form lasting friendships. This spurs an interest in having non-gendered clusters in returning student housing, which is a departure from the existing structure. The evolving needs of the community have been met with slow, steady change in the organization of the program. Song and his friends’ GIH cluster in Tabler Community is proof of that.

In the same vein, on Oct. 30, 2023, Campus Residences circulated an email that invited students to ll out an anonymous form to provide feedback on GIH.

The form consisted of questions re-

garding the current state of all-gender accommodation options and whether or not there should be changes as to how the suites and apartments are allocated.

“The form will have a very direct impact on how we do things,” MiWe said. “When we solicit speci c information like that, we will use it to make changes or see what’s possible or explore further options.”

In its current form, returning student GIH amounts to one suite or apartment in each residence hall. This is intended to maximize options for students in the GIH program. However, in some cases, this can make housing-related programs, such as the various Living Learning Communities (LLC), restrictive for LGBTQ+ students, as it only leaves one suite of spaces for them. The LLCs — which include Lauterbur Hall, Tubman Hall and Chávez Hall — have unique programs that feature community-building required events. They are also housed in some of the newer residence halls on campus, making them popular among students. MiWe shared that only 40% to 50% of those eligible for LLCs live in those communities. With only about six all-gender spaces per building in the LLC halls, the percentage would be even lower for LGBTQ+ students. MiWe said that they are aware of this concern, and are currently gauging student interest in adding more GIH spaces in LLC halls.

“We’re starting to look at that to explore it,” MiWe said. “But if we increase that, then you are reducing the amount of male and female spaces in that area, which also means there will be more to GIH in general, as students have to participate in the program and won’t have housing options elsewhere.”

Any consideration of adding more all-gender dorms to LLC buildings, MiWe said, would depend largely on student interest as reported in the form from the Oct. 30 email. They also oated the idea of adding an LLC community speci cally designed for LGBTQ+ residents centered around the same concepts as other LLCs through an

17 FEATURES THE PRESS

Stony Brook’s GIH program is one of around 450 in the country, according to the nonpro t Campus Pride. The National Center for Education Statistics reported that there were 5,916 postsecondary educational institutions across the country in 2021. This makes gender-inclusive housing programs a rarity in America. Because of this, it is one of the categories LGBTQ+ applicants use to determine whether a prospective school is LGBTQ+ friendly.

The debate regarding Gender-Inclusive Housing at Stony Brook comes at a time when the worst parts of queer American history are repeating themselves.

“2023 is on pace to be a record-setting year for state legislation targeting LGBTQ adults and youth, with legislation that targets healthcare, education, public places and services, and drag performers or entertainment,” says the LGBTQ+ advocacy organization GLAAD. “Each of the previous two years —2022 and 2021—were record-setting years for anti-LGBTQ legislation.”

Anti-LGBTQ+ laws target queer children and young adults under the guise of protection. The most egregious example of this is in gender-a rming care for youth aged between 13 and 18. Conservative politicians are xated on a misleading narrative of helpless children who are brainwashed into undergoing surgeries and hormonal treatment for gender ideologies that they don’t understand.

In reality, gender-a rming care is not, as they suggest, limited to irreversible surgery on minors. Such procedures are

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 18 FEATURES

LGBTQ+ lens.

quite rare. What is common, however, is gender-a rming mental health care and reversible hormonal treatments similar to those offered to cisgender patients experiencing hormone imbalances. For example, a short list of hormone replacement drugs used as gender-a rming care includes norethindrone, a form of progesterone. This drug is also on a list of medications used to treat polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Gender-a rming care is not only recommended by experts — such as the American Medical Association and the American Psychological Association — but also requires mental health benchmarks to be met and physician recommendations to be made. In other words, these are not treatments that are available on a whim or coerced.

Anti-LGBTQ+ legislation has also left the doctor’s o ce and arrived at schools, rst in the form of book bans. In 2021, Texas Republican Rep. Matt Krause presented a list of 850 books to the Texas Education Agency and school o cials across the state, asking them to investigate if these books were present in school libraries. This list, which included LGBTQ+ ction and non ction, as well as titles about race and U.S. history, opened the oodgates of book banning. PEN America, the U.S. chapter of the PEN International network, found in their annual report on banned books that, of 874 individual books targeted by book bans, around 229 contained “LGBTQ+ characters or themes” — 26% of the unique titles targeted. Censoring these books stemmed from an inherent sexualization of queerness that doesn’t exist with heterosexuality. This is the stated reasoning behind such book bans: queer experiences are inherently sexual content, and therefore they must be kept out of children’s hands.

This argument is at the core of most conservative challenges to sexuality as a topic of conversation in schools. Florida schools notori-

ously have one of the strictest rules regarding sexuality and gender in the country: 2022’s House Bill 1557, or the “Don’t Say Gay” bill. This bill, which originally only applied to K-5 elementary schools, now applies to grades K-12. Framed as a “Parental Rights in Education” bill, it prohibits “classroom discussion about sexual orientation or gender identity in certain grade levels.” Some schools interpret this law to require teachers to out LGBTQ+ students, should any of them feel safe enough to share their sexuality or gender identity with a teacher. Keeping these topics out of the classroom doesn’t stop LGBTQ+ children from existing. It merely tells these students that they are not welcome in the same spaces as their heterosexual peers, and that their existence is something shameful and un t for discussion. The “Don’t Say Gay” bill tells school-age children that their queerness is something that must be reported, like a crime.

We live in a country where states are graded against human rights standards to determine their status of basic equality, where that equality is a matter of heated debate and where falsehoods can be at the heart of legislation stripping away human rights. However, the government has seen an uptick in representation; there is a record number of openly-queer elected o cials in o ce. Cherelle Parker was elected as the rst female mayor of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Gabe Amo as the rst Black man to represent Rhode Island in Congress. It is only the beginning, one step on a long and winding road to equality. As long as this ght may take, it should be remembered that back in 1980, at the height of the AIDS/HIV crisis, it would have been a fantasy to imagine that same-sex marriage would be legalized by the Supreme Court and codi ed by Congress, or that there would be over 200 openly LGBTQ+ people in elected government positions. g

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 20 FEATURES

It’s 10 p.m. in the enclosed rooftop venue of Our Wicked Lady in Brooklyn. The crowd is just over two dozen people, all friendly and bubbly. The nal act is a minute or two into their second song when the frontwoman goes from drawing the bow across the delicate strings of her violin to screaming directly into the body of the instrument. Now, completely captivated by the unconventional performance, not one set of eyes in the room is diverted away from the band. But what many onlookers might not be aware of is that less than a week prior to this show, that same person perched above them on the tiny stage was across the country playing to an audience nearly 700 times the size, and a billion times as loud. The mastermind behind this chaos is Lily Desmond.

Originally from Los Angeles, Desmond, 29, has been playing violin since the age of 7 — an amount of time that she says “is scary to think about.” Curiously, Desmond’s connection with music dates to even earlier in her life — her mother recalls her “screaming melodies” in the backyard starting at the age of 2. Her parents, both musicians in their own right, have been well

disposed to Desmond’s decision to take a professional route in her musical career. “I’m very lucky to have parents that are both very into the arts,” Desmond said. “They really supported me going into basically the hardest life route possible.”

Upon graduating high school, Desmond moved across the country to New York to attend Sarah Lawrence College where she studied music, anthropology and writing. After earning her liberal arts degree in 2016, she decided to remain in New York. “Weirdly, everybody encouraged me to — they were just like, ‘You’ll like the East Coast.’” She always took part in family bands or school performances, but she branched out and started playing with other artists during her time at Sarah Lawrence. She performed her rst solo show in 2018, two years after graduating.

“Ifeltveryshyaboutworkingwithother people for the majority of my young adulthood,” she said. “Mostly because I felt like I wasn’t really a cool kid. I was hanging out with anime nerds and going to conventions and playing video games with people and stu . And my music was a very solitary thing for me for a long time.”

Nowa-

days, you can nd Desmond ambitious-

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 22 MUSIC

Photos by Layne Groom and Leanne Pastore.

ly working with four to seven groups at any given time. Currently, she is closely involved with the avant-garde, chamber pop group Sloppy Jane and queer country star Brian Falduto, whom she plays violin for. She recently started collaborating with and writing string arrangements for the Brooklyn-based animator, musician and Stony Brook University alum BenBen. She is also the maestro and sole composer for the original theatrical performance The Tiger’s Bride created by the Theatre Uzume. Through these collaborations, she has traveled coast to coast, overseas and even underground.

Last Halloween, Desmond and her violin accompanied Sloppy Jane and eight other band members onstage at the Hollywood Bowl in her hometown of Los Angeles. “It was so chaotic,” she said. “It

was amazing.” Opening for the hyper-pop dyad 100 gecs and indie su-pergroup boygenius, the sta-dium was lled to capacity, accommodating over 17,000 screaming fans — the largest crowd she had ever performed for.

“I never experience nerves when I’m playing in a band,” she said. “Especially in Sloppy Jane, because it’s such a huge group, and I feel it’s like camaraderie among numbers. But I felt like I was about to throw up before going on that stage. And then as soon as I got on, I was like, ‘Oh, I can’t see most of the audience. It’s gonna be ne, it’s gonna be great.’”

Desmond also works in smaller projects with Concetta Abbate, another Brooklyn-based violinist and composer. She has played in several of the ensembles that Abbate frequently runs. Recently they have put together — along with viola player Alec Santa Maria — a chamber group that has each member

write songs for the performances.

“It is a di erent muscle,” she said. “I think that I kind of have to put a little bit more of an academic hat on when I’m doing that, or I have to kind of fall back a little bit more on theory than what I’m intuitively used to. Though, I still very much fall back on singing melodies that I think sound good and then translating that into something else to still make it feel compelling.”

Her career also extends well beyond performing. In October of 2020, she began giving online violin lessons, having taught students as young as 6 to as old as 64. But managing her job alongside end- less hours of

hero on an adventure. In his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, where he rst showcased the theory, Campbell describes the Hero’s Journey: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Each release in this project will represent a di erent character typically depicted in the monomyth. “OMEN is sort of like the dark or villain of this whole Hero’s Journey concept world I’m in, and then I’m going to release another one from the hero’s perspective,” she explained. “From there, I think I want to do a full album that’s probably going to be like 12 plus songs.”

projects, rehears- als and tutoring doesn’t come free of challenges, leading to restless weeks and many uphill battles. “My funds are very low, but thankfully my students understandIhaveavery exiblescheduleand I let them know I’m a touring artist,” she said. “I gotta take time o sometimes. Basically I just can never get sick.”

Her newest release OMEN came out on July 1, 2023. The short, but richly inspired, four-song EP is the rst in a collection that will make up a larger body of work. Desmond is constructing this project around Joseph Campbell’s theory the Hero’s Journey — which is conventional to the world of literature, but provides a unique foundation to build her euphonious ideas o of. In the 1940s, Campbell was studying the fundamental structure of mythology and folklore. While doing so, he found a pattern unique to stories involving a

Desmond has been sitting on the idea since 2014, but only started working on the tracks in 2019. She nished the songs during the COVID-19 lockdowns and the recording was completed in 2021.

The release show for OMEN was held at the pinkFROG cafe in Brooklyn on July 1. At about 6:30 p.m., attendees started to shu e into the co ee shop. As they made their way from the drink counter to the assorted wooden tables under dimly-lit chandeliers made of stu ed animals, they were greeted with printed programs to guide the experience. Inside them were not only the lyrics to the EP’s songs, but also charts and excerpts that went deeper into the process and inspiration behind the project. Once Desmond stepped onto the stage and captured the audience’s attention, she did not sing. Instead she spoke. She traded in her string instruments for a PowerPoint presentation.

23 MUSIC THE PRESS VOL. 45, ISSUE 3

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 24 MUSIC

25 MUSIC

This wasn’t a performance of her new project, it was a self-described TED Talk.

Desmond went slide-by-slide to discuss the themes and ideas in OMEN, which included a lesson on Campbell and a discussion of psychologists’ dream theories. These lessons led into the songs from the EP being played over speakers. After each song concluded, members of the audience were encouraged to ask questions regarding the lyrics, composition or anything that came across their minds while listening. The event was well received, with many members of the audience joining in on the discussions. To conclude the show, Desmond played an unreleased song that will be included on the next part of the project.

This release show was preceded with a performance by BenBen. Since then, the two have turned into what he calls a “crazy partnership.” Desmond recorded 12 di erent string arrangements for BenBen’s new album, Sincere Gift, and joined him in the United Kingdom on a six-show tour in late November.

“When I found Lily’s music, my jaw hit the oor,” BenBen, also known as Ben

Wigler, said. “I felt a connection. We are the same kind of weird. Just an immense sense of kinship and identity. Like a spiritual twin or lost sibling.”

While nishing the production on Sincere Gift, Wigler found himself in an arduous situation where a handful of songs had to be scrapped, and brand new tracks were now needed to ll in the gaps. However, he saw this event as a “cosmic opportunity” to see how he and Desmond would work together co-writing songs. In only a few days, the two produced the new songs just in time for the vinyl pressing of the LP.

“She jumped right in the ring line with me,” Wigler said. “Lily is one of the truly most celestially gifted musicians of our generation. It seemed as though she was decades ahead in experience for someone her age.”

Despite her extensive list of talents, Desmond has — much like any other artist — struggled with self-doubt throughout her career. “In the pandemic, I de nitely had a crisis of whether or not I wanted to be a musician, as a career,” she said. “Much like everyone else around me, I was like, ‘Should I go back to grad school?’ I was thinking of

actually going back for religious studies because that’s a subject I’m really interested in. But I decided if I did that, I would probably die.”

Deciding not to go through with the career pivot has seemed to fare well for Desmond. She’s non-stop touring and has made many new collaborations since then, all while also working on her solo projects.

“It’s actually pretty recent that the self-doubt kind of stopped, and I think it was because of the OMEN EP release party,” she explained. “I think because the format of that event was so odd. And yet, people came and they told me how much they enjoyed it afterwards. It was like there is a place for my weird ideas. There are people who will connect to it.”

Several months have passed since then, and that connection has yet to fade. As Desmond and her bandmates carried on with the show at Our Wicked Lady, anyone momentarily looking away from the performance would have glimpsed at a sea of utterly engrossed faces — an image destined to be replicated across many concertgoers in the years to come. g

Leanne Pastore contributed reporting.

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 26 MUSIC

Corals are not colorful in real life. The water column lters the colors, making them look duller than they do in wildlife documentaries and high school science textbooks. This is only one out of the many things I learned from the scuba diving side of my life.

I dove in the ocean for the rst time in May 2015, when I was 12. The boat cut the rough surface of the dark blue ocean around Ilha Grande, an island o the coast of the state of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. I focused my gaze on the water, occasionally looking up to the horizon full of little islands covered by bright green treetops.

Although I had easily gone through the trainings, I was anxious. The ocean was di erent from the pool. It was wider, darker and scarier. Also, I wasn’t there as a tourist. My parents and I had taken an introductory scuba diving course three months prior, and it was time for us to be evaluated in the ocean and eventually certi ed as Open Water Divers.

I was sitting alone in the bow of the boat when an older woman approached me. She was probably in her 50s and wore a hair scarf stamped with pictures of hammerhead sharks — the ones she saw when she dived in the Galapagos, as she explained.

“I’m scared,” I told her, after we

had talked for a few minutes.

“Everything we do for the rst time is scary,” she replied.

That was a sentence I kept with me for every rst time after that.

My rst attempt was miserable. When scuba diving, the water pressure compresses the air in the middle ear, which is painful. To avoid damaging them, it is necessary to restore middle ear air volume by doing what we call “equalizing.” There are many methods to do that, and I failed at every single one of them. The instructor told me to go back to the boat and that I would have another chance after my parents were done.

I returned to the bow of the boat, where I silently cried for the next hour. When the instructor came back from the dive with my parents, he encouraged me to try one more time.

“It’s the hour of the sea turtle,” the captain of the boat said, trying to convince me to give it another shot.

I decided to go because I could not bear the possibility of not being good enough. This time, I succeeded not only in equalizing but also in doing all the required exercises. More interestingly though, I saw a sea turtle. It calmly and gracefully ipped its ns, as if time didn’t exist underwater. From that perspective, sea creatures don’t look like they are swimming, they look like they are ying in the in nite blue back-

ground.

Coming back from the dive, I wrote a narrative about it in my diving log. I remember writing it in all caps because I thought capital letters were prettier than lowercase.

GREAT DIVE! FIRST I HAD TROUBLE WITH THE EQUALIZATION OF MY EARS AND HAD TO COME BACK TO THE BOAT, BUT AFTER THAT I CAME BACK AND WAS ABLE TO DO ALL THE UNDERWATER EXERCISES AND STROLLING THROUGH THE DEEP WATERS I WAS ABLE TO SEE MANY RAYS AND FISHES THAT I HAD NEVER SEEN PERSONALLY. I LOVED IT!

Attheendofthattrip,Iwascerti edas a Junior Open Water Diver — the most basic certi cation of the diving world. Still, I was far from what I wanted. Scuba diving isn’t as simple as putting on equipment and throwing yourself in the water. You can do it that way, sure. But if you value your life and your safety, you probably go through a course before every new type of dive you’re trying. And that’s why my parents and I returned to the pool of our non-coastal Brazilian city. We wanted to go deeper, dive during the night and explore the possibilities that an Advanced Diver certi cation would give us.

However, at the time, I didn’t know that was what I wanted. I was doing it because my parents made me. On the second day of training, I had

29 OPINIONS THE PRESS VOL. 45, ISSUE 3

trouble uctuating and, when I complained about it to my father, he laughed. I was infuriated. I didn’t want to be there, in that uncomfortably warm pool on a Saturday afternoon. He had made me. And now he was laughing at me? I slapped his face.

“Get out of the pool right now,” he yelled.

I took my equipment o and ran to the bathroom. Locked inside the cabin, I loudly cried over my black and red neoprene wetsuit. We made up later.

The rst step to our Advanced Diver certi cation happened in July 2017. It was my 21st dive. We dove in Lagoa dos Ingleses, or Lagoon of the English, which is a muddy lake in my home city.

This dive was excellent because I was able to dive in my home city (which has neither a sea nor a river).

In the following years, we got extra certi cations in Wreck Diving and Enriched Air Diving. These allowed me to dive near wrecks and make my dives longer, respectively. Scuba diving wasn’t always fun, but, slowly, the uniqueness of it enchanted me.

My high school friends couldn’t say they survived a tropical storm right after diving with sharks in the Bahamas. They couldn’t say they spent their winter break watching the sunset in the Caribbean Sea in Honduras.

I logged every single dive I did. Some of them, like number 14, don’t have a description at all and others, like number 19, have a very short one. “Six turtles, I WILL ONLY SAY THAT!” On number 50, I wrote, “These 50 dives added to me a lot of things that I could never have imagined.”

Number 60 is the one with the lengthiest narrative. It happened on Jan. 2,

2020 — two months before the pandemic hit. On that day, I dove in a turquoise lake at the bottom of Abismo Anhumas, an abyss located in Bonito, a small town in the countryside of Brazil.

I wrote down every detail about it, from rappelling down the abyss to seeing the skeleton of a tamanduá bandeira on the bottom of the lake. On the top of the page, I wrote, “W.O.N.D.E.R.F.U.L.” in small handwriting — proof that I was trying to make everything t. The notes on the margins prove it wasn’t enough.

On number 86, I vented. The year was 2022. I was in Fernando de Noronha, Brazil, with my parents. First, I felt like I couldn’t keep up with their rhythm. Then, I was frustrated because I thought my father didn’t take my dive log seriously.

I don’t think he understands how important this dive log is to me, he doesn’t understand that I use it as a diary. On that note, I want to leave a thought here: I DON’T love to scuba dive. Okay?

From the beginning, logging my dives was something that I liked doing. Even if I didn’t want to dive, I did, just so I could come back and write more. I documented eight years of scuba diving in those pages. My calligraphy changed. My grammar certainly improved. But what I nd most magical is that I changed. My descriptions of every single one of those dives re ect the person I was at the time. In January 2023, I logged my 100th dive.

Century diver! Scuba diving continues to add to me in many ways that I could never imagine (see dive 50). Recently, I started a diary. I was unfair to you, diving log. But, in this text that I write on the boat’s table, I wanted to thank you for being such a loyal companion during these eight years as a scuba diver. I wanted to give up many times, but coming here to narrate my adventures with

a tank was what gave me strength.

I focused my gaze on the water as the boat cut through the rough surface of the ocean.

Technically, we were in the Abrolhos Archipelago, o the coast of Bahia, Brazil. But there were no islands on the horizon. We had sailed to more open waters. All I could see was the vast Atlantic Ocean.

I put on my suit, tightened my mask and adjusted my yellow ns. I jumped in the water and made a downwards thumb with my hand, signaling that I was starting to go down. With me were my parents, my uncle, my aunt and my 11-year-old cousin — who was only on his third scuba diving trip.

It wasn’t a dive with many creatures. Instead, we swam in a coral formation named Chapeirão Faca Cega. It translates to blind knife hat and was named after its skin-cutting sharpness. It’s the only of its kind.

It can be whatever you want. A cathedral, a castle, a forest—it’s mutable according to the perception of each person. Just like scuba diving.

What even is scuba diving? An extreme sport? An outdoor activity? A lifestyle? I have done it 101 times, and I don’t know yet. How can something so abstract in meaning be so distinguishable in the making?

For now, I’m ne not knowing the answer. The unknown calls for adventures, and adventures lead to magnificent sea creatures, cries and writing sessions. They make me feel alive. They make me grow. The corals might look dull, but they de nitely have something that keeps me coming back to them. g

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 30 OPINIONS

Illustration by Jane Montalto.

ennessy Garcia led a Black Lives Matter march through Washington Square Park in New York City during the summer of 2020, toting a loudspeaker and hair scrunchies. As she handed the megaphone o like a torch to people who wanted to voice their thoughts on police brutality and the justice system, a woman una liated with the march made her way to the front and stripped naked. Garcia laughed.

Journalists, cops and marchers stopped to scan Garcia’s face — wondering how she would handle the unexpected event. She kept laughing and walked a little faster. Hundreds of people behind her walked a little faster too, shrouding the naked woman and the awkward situation in the bodies that followed Garcia’s steps.

Three years later, 25-year-old Garcia is still as down-to-earth as she was then. Nowadays, she is more cautious — but her impact on New York City communities has increased exponentially.

Born and raised in the South Bronx, the Indigenous Afro-Latina was ushered into a climate story, which is a personal experience with the e ects of climate change. They’re often more prevalent in underprivileged communities.

In the Bronx, the poverty rate was 26.4% in 2021, according to data from the NYU Furman Center. This is 8.4% more than the citywide poverty rate. The statistic is even higher in the South Bronx, where 36.3% of its residents live in poverty.

“I would not be where I was if I didn’t grow up in the South Bronx, like I didn’t realize I have what’s called a climate story,” Garcia, who now lives in Queens, said. “So realizing now, at 25 years old, ‘Oh, wow, this place has a lot of pollution, a lot of litter,’ — and then now having the language like, ‘Oh, that’s like, environmental racism.’”

As a rst-generation student and eldest sibling, Garcia felt pressured to get an education for socioeconomic mobility. She enrolled at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry to study environmental science in 2016, but never nished. Nearly seven years later, Garcia is still working on her bachelor’s, at a di erent college — her work as an activist derailed her from the more conventional track she was previously on.

Despite the change of plans, Garcia loves academia just as much as activism. She attends not one, but two colleges — one in person and one online. At the in-person college, she studies environmental science. She stud-

ies data analytics at her online college.

She plans on pursuing a doctoral program in the future, and she has taught herself code, data programs and software programs on the side. The interdisciplinary nature of her education has made her a better and more well-rounded activist, she said.

“Sometimes I get a little embarrassed about being 25 —I’m still working on my undergrad,” Garcia admitted. “It’s been a struggle just kind of balancing activist work and my schoolwork.”

Garcia is an activist for a variety of causes, and works with multiple organizations. She started out in 2020 with the Black Lives Matter movement, but has increased her bandwidth over the years.

“I kind of pivoted in 2021 towards the [reproductive rights] space. And I didn’t expect that, because I grew up in a Catholic household,” Garcia said.

She learned more about reproductive rights, which she calls “repro,” as she progressed through her career, further fueling her interest in the subject.

“My mom is like — she’s loosened up now that I tell her everything — but my mom was very anti-abortion and would have the mindset of normal antis. ‘Yeah, I don’t kill the baby.’ Bla bla bla bla, whatever.”

In a concerted e ort with other students on the State University of New York and City University of New York campuses, Garcia worked for more than three years on a bill to gain access to abortion pills on public campuses in New York. In May 2023, Governor Kathy Hochul signed it into law. The bill mandates all these campuses to either have abortion pills on-site, or have a plan to refer students to a clinic that can o er it.

Garcia also works as a lobbyist for Sixth Street Community Center (SSCC), a community program oriented

towards ghting for environmental justice in the Lower East Side in Manhattan.

“I don’t like talking to politicians, but, for some reason, ever since I got this job at Sixth Street Community Center—I’m really good at it,” Garcia said with a laugh.

With SSCC, she has provided mutual aid in the form of free food, youth programs and lobbying for climate justice in Albany. At one point, Garcia had 75,000 people come out to march against the lack of climate action with SSCC.

However, not all of her work has been as rewarding, Garcia is careful to mention. A month after the Black Lives Matter protest she led in 2020, a woman ran over several of Garcia’s friends at a protest against Immigration and Customs Enforcement. They were hospitalized and one was treated with broken limbs, but all ultimately recovered. She’s received death threats — prompting her to remove her family from her social media accounts for their safety, get a Virtual Private Network to ensure online security, and privatize her Instagram ac-

count.

She’s simultaneously hopeful and apprehensive for up and coming activists. Garcia explained that people are getting nervous as the e ects of climate change materialize more rapidly, but this could also be what pushes them to the streets to protest.

“I feel very gaslit by the government, by politics and shit,” Garcia said. Ultimately — she does it for her siblings.

“I don’t want them to experience the stu I have experienced,” she said. “I don’t want them … knowing a future [without] bodily autonomy,” she said. g

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 32 FEATURES

I’m afraid of endings, and I think about them constantly. I suppose I have a disposition for worry. I worry about the end of relationships, the end of school and even the end of seasons.

Sometimes, the seasons fade so seamlessly into each other that I don’t realize when I’ve left summer for fall. That delicate, nearly unnoticeable shift means I don’t grieve for what I’ve left behind in summer like sunshine in late afternoon and mornings without the necessity of hot co ee. I nd that summer has learned to linger deeper into the later months of the year, but, when I notice this, I’m lled with dread. When I realize how unnatural it is to be enjoying the spectacle of heat so late in the year, I get nervous. I think of climate news: record levels of carbon dioxide, methane leaking from arctic ice and sea levels rising. My worry shifts from speculating about the end of summer to the

the cycle restarted. To cope with it, I called out of work and got on a train.

Melchor, a New Jersey-born singer-songwriter that resides in Los Angeles, released his newest EP FRUITLAND just after starting a North American tour with Laufey. The opening track “BIGTIMEGOODTIME” demonstrates that Melchor is on a similar wavelength as me. The lyrics create a frantic kaleidoscope of the ways in which the world overwhelms: “Rising tides and mudslides / Gender rights and antisemites / Wonder why I just can’t sleep at night.” Thisshiftingofworldlyanxietybetween the environmental, political and personal is something I share with Melchor. I too have trouble falling asleep when anxiety comes. But Melchor’s answer to worrying — at least in this track — is di erent from mine. In the chorus, he

end of humanity.

This year, the grasp of summer didn’t last too long. November arrived with a sudden, uncompromising cold, and with that cold I arrived at Adam Melchor’s opening for Laufey at the Town Hall in Midtown Manhattan.

When I’m faced with a domineering and shapeshifting worry, I tend to escape to music. This is how I found myself watching Adam Melchor perform live on stage. In the days before his performance, I felt burdened by the reminders of all that’s wrong with the world. Not just headlines of climate catastrophe, but also depictions of war, poverty, injustice and monumental suffering. I registered to vote and thought about how insu cient my actions were compared to the issues that preoccupied my worrying. I reminded myself that my education is oriented around preparation for tackling issues at a larger scale — then, my worries shifted again to a midterm and two papers due within a week. I checked my phone, and

repeats that he’s “looking for a big time, good time now.” That lyric shift is accompanied by an adjacent sonic shift. As Melchor moves from his listing of concerns to the track’s titular anthem, the sound goes from a stripped down melodic line, accompanied by guitar, to swelling vocals and the entrance of other instruments. In this chorus, he answers the problem of worry with revelry. At the same time, he sounds almost resigned — as though reveling is all he can do, as though it’s the only option.

My response to worry isn’t a disillusioned pursuit of good times. Of course I want to enjoy life, but looking for an escape doesn’t make my worries go away — it lets me forget for just a moment. I do turn to music to ease my anxieties — just in a di erent way.

On nights when I just can’t sleep, I sometimes play especially soft songs to calm down. These songs, which soothe my restlessness, become lullabies. But when I listen to a lullaby, I’m not trying to feel nothing. Instead, I’m giving myself time and space to feel a particular

feeling. I can acknowledge where my worries come from and accept them. I can make peace with them for just a moment.

Melchor also has a habit of making music into lullabies. On his Instagram pro le, there is a phone number—973264-4172 — which, when texted, puts the sender on a list to receive acoustic covers of his and other artists’ works.

Through that project, he honed a tender, acoustic sound. His rst album, Melchor Lullaby Hotline Vol. 1, is devoted to that soft yet hearty style. In this way, “BIGTIMEGOODTIME” is a departure for Melchor where he embraces a lyric restlessness that complicates the nature of his songwriting. His new EP, speaking more broadly, is noisier than his earlier music, and his lyrical xation on endings is ampli ed by a more percussive and irregular soundscape which is, at times, staticky or invaded by murmuring background voices.

On the November night I saw Melchor perform, he didn’t sing “BIGTIMEGOODTIME.” He sang his lullabies. The only tracks he did sing from the new EP, “ADELAIDE” and “PEACH,” t the description of a lullaby. The set was stripped down and consisted of just his voice and guitar. He opened the set with a brief cover of Judy Garland’s “Over the Rainbow,” and with just the rst two notes — that grandiose octave leap from “some-” to the cloud-scraping “where” — Melchor’s tenacity as a musician became clear. The quality and control of his vocals were striking, and I’d learn later that he had studied opera in school.

Melchor’s true answer to dealing with the overwhelmingness of the world has something to do with love. Every song he performed was simultaneously a lullaby and a love song. In “ADELAIDE,” Melchor returns to the thread of the overwhelming introduced in “BIGTIMEGOODTIME”ondi erentterms.Here,it

VOL. 45, ISSUE 3 THE PRESS 34 MUSIC

Photos by Aman Rahman.

is embodied in the subject of the song. In singing that “there’s a world outside your door,” Melchor’s frame becomes smaller. This isn’t the kaleidoscopic view of the world from the opening track. There’s only Melchor and Adelaide. As he sings, “There’s a way to ask for more / So, ask for more, Adelaide,” his view of the world shifts. There is tenderness in these lyrics — the world is something we can, and should, be a part of.

In “PEACH,” Melchor turns to a feeling of helplessness or powerlessness when in love. He becomes weak to the subject of the song, and submits to just taking what he can get. In a sustained, higher register, Melchor sings: “Who knows when this life ends / When it stops or starts again?” Suddenly, we return to Melchor’s xation on endings, and his uctuating frantic responses to them. In his EP, noise and outburst are a response to the aggressions of the world. However, in the lullabies of his set, he invokes a more tender and soothing style of music. Melchor is a romantic — love is never far from his mind as made clear from his set — but the subject of FRUITLAND is not love itself. Rather, the EP is oriented around what to do with love. That is, it levies love against the stubbornness of life. The pursuit of love, expressed especially in “ADELAIDE,” is a kind of bravery. To love is to resist the overwhelmingness of the world that “BIGTIMEGOODTIME” introduces.

But where does this leave us? Melchor’s responses to an overbearing world are contradictory. In “BIGTIMEGOODTIME,” his answer is to party. In “ADELAIDE,” it’s to practice love in the face of worry. In his lullabies, it’s to simply let himself feel what he feels.

The last track of Melchor’s EP, ttingly titled “RESOLUTION,” ties these threads together. There’s a restlessness that pervades the song: swirling synths in the background, a simple percussive melody and quiet plucked strings. Melchor’s voice shifts to a lower register that sounds earthy and comfortable. He’s still circling this idea of endings, repeating the phrase “this is the end,” but it seems he’s ready to just give in and accept the pessimism of worry. Then, about halfway through the track there’s a huge tonal shift—electric guitars and a pervasive crunching sound enters. As the song nears its end, the backing vo-