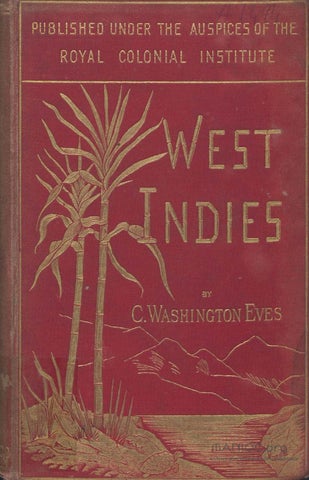

PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE ROYAL COLONIAL INSTITUTE

WEST INDIES BY C. WASHINGTON EVES

MANIOC.org Archives départementales de la Guadeloupe

PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE ROYAL COLONIAL INSTITUTE

WEST INDIES BY C. WASHINGTON EVES

MANIOC.org Archives départementales de la Guadeloupe