BEETHOVEN AND STRAUSS

Former SCO Conductor Laureate Sir Charles Mackerras had the vision to help the SCO by leaving the legacy of his royalty payments from his SCO recordings in perpetuity. We remember him with the utmost respect, fondness and gratitude.

As a small way to show our appreciation, we have created The Sir Charles Mackerras Circle for those who wish to pledge by making a legacy gift to benefit the SCO.

To recognise their generosity during their lifetime, circle members will be invited to an annual behind-the-scenes event to hear about how legacies are helping to make incredible live music accessible to as many people as possible.

To learn more about the Sir Charles Mackerras Circle, contact Mary at mary.clayton@sco.org.uk or call 0131 478 8369

With special thanks to Summer Tour sponsors

Eriadne and George Mackintosh, Claire and Anthony Tait and The Jones Family Charitable Trust

Wednesday 13 September, 7.30pm, Holy Trinity Church, St Andrews

Thursday 14 September, 7.30pm, Troon Town Hall

Friday 15 September, 7.30pm, Cumbernauld Theatre

Mendelssohn The Fair Melusine

Strauss Duet-Concertino for clarinet and bassoon

Interval of 20 minutes

Beethoven Symphony No 4 in B-flat

Jonathon Heyward Conductor

Maximiliano Martín Clarinet

Cerys Ambrose-Evans Bassoon

The internationally celebrated Scottish Chamber Orchestra is one of Scotland’s National Performing Companies.

Formed in 1974 and core funded by the Scottish Government, the SCO aims to provide as many opportunities as possible for people to hear great music by touring the length and breadth of Scotland, appearing regularly at major national and international festivals and by touring internationally as proud ambassadors for Scottish cultural excellence.

Making a significant contribution to Scottish life beyond the concert platform, the Orchestra works in schools, universities, colleges, hospitals, care homes, places of work and community centres through its extensive Creative Learning programme. The SCO is also proud to engage with online audiences across the globe via its innovative Digital Season.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor.

The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in November 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. The repertoire – Schubert’s Symphony No 9 in C major ‘The Great’ –is the first symphony Emelyanychev performed with the Orchestra in March 2018.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen, François Leleux, Pekka Kuusisto, Nicola Benedetti, Richard Egarr, Andrew Manze and John Storgårds.

The Orchestra enjoys close relationships with many leading composers and has commissioned almost 200 new works, including pieces by the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Sir James MacMillan, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly, Anna Clyne and Associate Composer Jay Capperauld.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle is made up of individuals who are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Hedley G Wright

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Productions Fund

The Usher Family

Bill and Celia Carman

Anny and Bobby White

Christine Lessels

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Kenneth and Martha Barker

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Double Bass Nikita Naumov

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe Robin Williams

Hedley G Wright

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

First Violin

Stephanie Gonley

Afonso Fesch

Stephanie Baubin

Kana Kawashima

Aisling O’Dea

Siún Milne

Fiona Alexander

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Second Violin

Gordon Bragg

Michelle Dierx

Rachel Smith

Niamh Lyons

Sarah Bevan Baker

Stewart Webster

Viola

Max Mandel

Katie Perrin

Brian Schiele

Steve King

Cello

Philip Higham

Donald Gillan

Eric de Wit

Kim Vaughan

Bass

Nikita Naumov

Jamie Kenny

Flute

André Cebrián

Marta Gómez

Oboe

Robin Williams

Julian Scott

Clarinet

Maximiliano Martín

William Stafford

Bassoon

Information correct at the time of going to print

Horn

Benjamin Hartnell Booth

Ian Smith

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Shaun Harrold

Timpani

Louise Lewis Goodwin

Harp

Sharron Griffiths

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Alison Green

Aisling O’Dea

First Violin

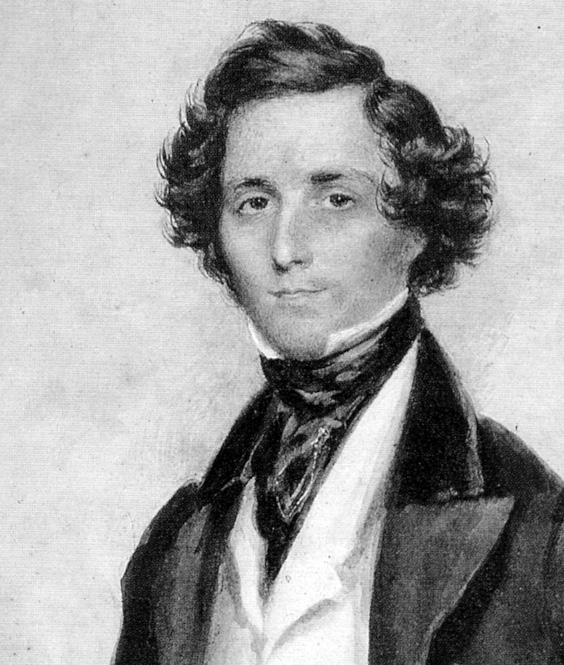

Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

The Fair Melusine, Op 32 (1834)

Strauss (1864-1949)

Duet-Concertino for clarinet and bassoon (1946/47)

Allegro moderato

Andante

Rondo

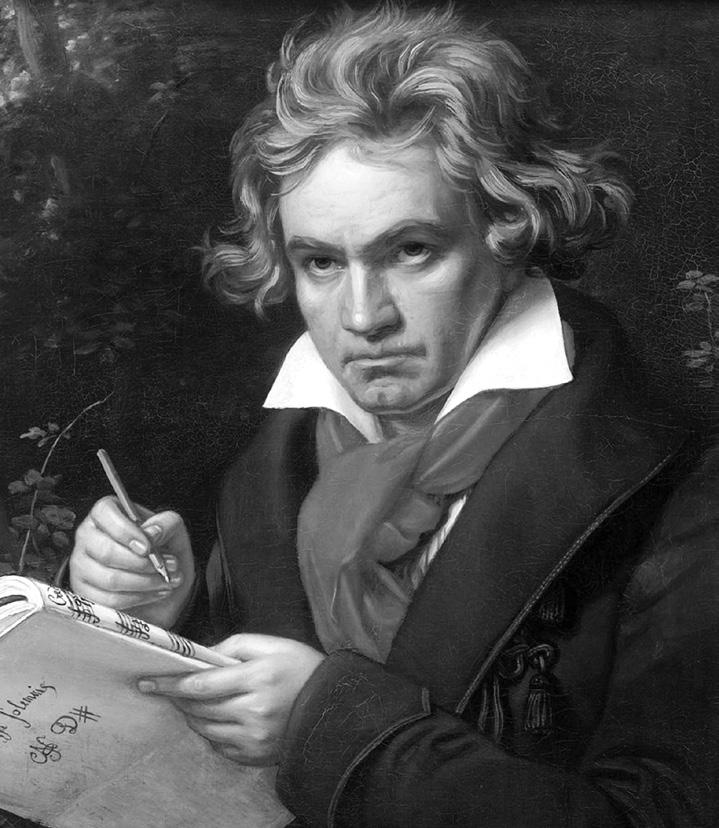

Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No 4 in B-flat, Op 60 (1806)

Adagio – Allegro vivace

Adagio

Scherzo: Allegro vivace

Allegro ma non troppo

You probably weren’t thinking much about Walt Disney on your way to tonight’s concert. You might be, however, by the time we reach the interval. Two of the great film maker’s (or at least his studios’) more recent animated features – The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast – provide a modern-day thread running through the first two pieces in tonight’s concert. More importantly, however, those pieces demonstrate just how far back in time these fairytales stretch in our imaginations.

The fishy subject matter of Felix Mendelssohn’s The Fair Melusine Overture certainly bears an uncanny resemblance to the plot of Hans Christian Andersen’s tale The Little Mermaid (which, by coincidence, the Danish author was writing around the same time that Mendelssohn was composing his Overture). It was the Andersen tale, too, that supplied Disney Studios with the raw materials for its 1989 animated movie – even if a few of the Dane’s darker touches got brightened up in the process.

In fact, it’s a tale that’s been around since at least the Middle Ages: the legend of the mermaid Melusine is first recorded in a medieval French romance as far back as 1387. According to the original story, the waternymph Melusine marries the dashing knight Count Raymond of Poitiers, on the condition that he never enters her room on Saturdays, the one day of the week when she must take on her original mermaid form. Predictably intrigued by what she gets up to at the weekend, Raymond spies on her in her bath, with the result that she disappears forever from the sight of all humans, leaving nothing behind but the distant sound of wailing.

For Mendelssohn, the specific inspiration for his Overture came not so much from

the tale itself, but more from a sense of disappointment and disapproval at another composer’s attempt to convey it, and the knowledge that he could do so much better. He’d seen one of the few performances of Conradin Kreutzer’s opera Melusina, in Berlin in 1833, and was deeply unimpressed. He wrote to his beloved sister Fanny that the opera’s overture ‘was encored, and I disliked it exceedingly, and the whole opera quite as much: but not [the singer] Mlle. Hähnel, who was very fascinating, especially in one scene when she appeared as a mermaid combing her hair; this inspired me with the wish to write an overture which the people might not encore, but which would cause them more solid pleasure.’

Mendelssohn wrote his Overture in 1834, as a late birthday present for his Fanny, and it was premiered in London in April of that year, one of a trio of works commissioned from the composer by the Philharmonic Society of London (so close was their relationship that

Mendelssohn even sent them a fourth piece, free of charge: his ‘Italian’ Symphony, No 4). And though Mendelssohn denied that he was explicitly attempting to tell the story of Melusine in his music, there are nonetheless clear references to the tale. It opens with a gently rippling figure that moves across the orchestra, surely evoking Melusine’s watery home, and its second main theme – far louder, brusquer and more dramatic – can only refer to Count Raymond, and perhaps even to his shocking discovery. After the Overture’s central development section combining these two themes, they return again at the end, and Melusine’s watery music brings the piece to a gentle, somewhat melancholy close.

There’s a fairy-tale inspiration behind Richard Strauss’s Duet-Concertino, too – or at least there might be. Strauss himself was never entirely clear, to the point of being downright contradictory. He wrote to the Concertino’s dedicatee, Hugo Burghauser – who’d been principal bassoonist with the Vienna

For Mendelssohn, the specific inspiration for his Overture came not so much from the tale itself, but more from a sense of disappointment and disapproval at another composer’s attempt to convey it, and the knowledge that he could do so much better.Felix Mendelssohn

Philharmonic Orchestra – explaining that the first movement depicted a dancing princess cavorting with a bear, who later magically transforms into a handsome prince (surely a reference to Beauty and the Beast). However, conductor Clemens Krauss – a close friend of Strauss and a noted early interpreter of his music – swore that the composer told him the Concertino was based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale The Princess and the Swineherd, about an impoverished prince who disguises himself as a humble pig-keeper to win the heart of a haughty princess. It’s even been suggested that Strauss might have really had in mind an episode from Homer’s Odyssey.

Whatever its specific inspirations, however, it’s a magically evocative work in the unusual form of a concise double concerto for clarinet and bassoon. They’re accompanied by an orchestra of just strings, plus occasionally a harp (whose contributions are infrequent but important). Strauss enriches his sonic palette

even further by occasionally asking principals from his string ensemble to play almost as a chamber grouop – first demonstrated at the Duet-Concertino’s intimate opening.

It’s also Strauss’s very last purely instrumental piece, completed in 1947 when the composer was a remarkable 83. It’s one of a clutch of distinctive works from the very end of his life – alongside the Oboe Concerto and Four Last Songs – that display a remarkable autumnal richness, a nothing-left-to-prove mellifluousness, and also a certain nostalgia. Strauss had remained in Nazi Germany during World War II, though he was generally lying low at his Alpine hideaway in GarmischPartenkirchen. Because of his continued dealings with the Nazis, however, he found his bank accounts frozen and his assets seized by the victorious US forces following the conflict, while his involvement with the regime was investigated (he would be cleared of any wrong-doing in 1948). As a result, the octogenarian was left in the unexpected

It’soneofaclutchof distinctiveworksfrom theveryendofhislife –alongsidetheOboe ConcertoandFourLast Songs–thatdisplaya remarkableautumnal richness,anothing-left-toprovemellifluousness,and alsoacertainnostalgia.Richard Georg Strauss

position of needing to earn money urgently: hence a three-week visit to London to conduct many of his pieces in the autumn of 1947, and grateful acceptance of commissions for new works.

When a request for a new piece came from the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana and its conductor Otmar Nussio that same year, Strauss had already begun laying out sketches for what would become the Duet-Concertino, though the commission served to crystallise his thoughts. What he finally produced is a compact, deeply lyrical work that highlights its soloists’ skills both separately and together. It’s nonetheless extraordinary to consider that just a few years after the Duet-Concertino’s premiere in April 1948, Strauss’s compatriot Karlheinz Stockhausen would unleash his first experiments in electronic sound into the world, and change what we consider music forever.

A sextet of solo strings launches the DuetConcertino’s gentle opening movement, creating a mood of wistful nostalgia that ushers in the clarinet’s own plaintive melody. After a more dramatic, almost recitativelike section, it’s the bassoon that takes over the movement’s faster-moving second main theme. A rich reimagining of the opening melody serves to lead the music without a pause into the second movement, which places the bassoon centre stage, accompanied by sparkling tremolos from the strings and harp. Strauss’s final movement is the DuetConcertino’s meatiest, and its perky theme –which makes its presence felt again and again – is shared between the two soloists, growing steadily more impassioned as the music heads for its confident conclusion.

neglected, there’s no denying that his Fourth is probably his least well known. That’s very likely for the simple reason that it sits between his grander and more exuberant Third (the ‘Eroica’) and the heroic triumphalism of the Fifth. None other than composer Robert Schumann famously described the Fourth as ‘a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants’. But despite its sunny disposition and its modest, Haydn-esque proportions, we might be wrong if we simply consider it as a musical throwback between two pioneering masterpieces.

A lot of the Fourth Symphony’s lighthearted mood and humble proportions may come down to the circumstances of its commission. Beethoven spent the summer of 1806 away from the bustle of Vienna, at the Silesian country estate of his friend and patron Prince Karl Lichnowsky. The Prince invited the composer to visit a nearby friend – and, it turned out, Beethoven super-fan – Count Franz von Oppersdorff in Oberglogau (now Głogówek in Poland). So passionate about music was the Count that he not only kept his own private orchestra, but also insisted that every single person in his household learnt to play an instrument. And he demonstrated his enormous admiration for the visiting composer by asking him to write a new symphony for his private band, in return for a generous fee.

We depart from the land of fairytales for tonight’s final piece. And, however strange it might feel to call a Beethoven symphony

Given the flattery and the substantial sum involved, Beethoven was hardly likely to decline. He’d already started work on what would become his Fifth Symphony, but sensed that it wouldn’t suit Oppersdorff’s petite, Haydn-loving orchestra. Instead, he offered an entirely different piece, the Fourth Symphony – perhaps written expressly with Oppersdorff’s players in mind, though there’s substantial evidence to suggest that

Beethoven had already composed the work, and it was simply good luck that it chimed with the Count’s expectations.

Despite Beethoven giving Oppersdorff exclusive performance rights for six months, the Count graciously allowed the private premiere to take place in Vienna, at the city mansion of Prince Lobkowitz, another of the composer’s patrons, in March 1807. The public first heard the Fourth Symphony in April 1808 at Vienna’s Burgtheater, though it wasn’t much of a success, despite its relatively listenerfriendly, conservative tone. Even fellow composer Carl Maria von Weber found it all a bit too radical and outlandish for his personal tastes, writing sarcastically that Beethoven, ‘above all things, throws rules to the winds, for they only hamper a genius’.

To modern ears, the Fourth might sound quite a bit more conservative, even backwardlooking, than the ‘Eroica’ or Fifth Symphony that stand either side of it. But that’s to

Evenfellowcomposer

CarlMariavonWeber founditallabittoo radicalandoutlandish forhispersonaltastes, writingsarcasticallythat Beethoven,‘aboveall things,throwsrulesto thewinds,fortheyonly hamperagenius’.

disregard Beethoven’s continuing innovations, in terms of the music’s power, its tautness, and its ruthlessly rigorous structures. The first movement’s slow, brooding introduction manages to avoid the Symphony’s ‘home’ key of B flat for all of 42 bars, and when its main faster section bursts into life, it represents a wholesale change of mood. The slower second movement pulls a characteristically Beethovenian trick of contrasting a long, slowly unfolding melody against an accompaniment of almost military-style precision. The third movement – apparently a minuet dance, but really more of a sparkling scherzo – flickers constantly between light and darkness, with prominent woodwind writing in its central trio section. Beethoven closes with a dose of infectious jollity in his dashing finale – though spare a thought for the orchestra’s principal bassoonist, thrust unexpectedly into the spotlight alone towards the end of the movement.

© David Kettle Ludwig van BeethovenJonathon Heyward is forging a career as one of the most exciting conductors on the international scene. He currently serves as Music Director Designate of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and will commence his five-year contract in the 2023-24 season.

Jonathon made his debut with BSO in March 2022 in three performances that included the first-ever performance of Shostakovich’s Symphony No 15. From summer 2024, Jonathon will become Renée and Robert Belfer Music Director of Lincoln Center’s Summer Orchestra. This recent appointment follows a highly acclaimed Lincoln Center debut with the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra, in summer 2022, as part of their Summer for the City festival.

Currently in his third year as a Chief Conductor of the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, in summer 2021, Jonathon took part in an intense, two-week residency with the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain which led to a highly acclaimed BBC Proms debut. According to The Guardian Jonathon delivered “a fast and fearless performance of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, in which loud chords exploded, repeating like fireworks in the hall’s dome, and the quietest passages barely registered. It was exuberant, exhilarating stuff.”

Jonathon’s commitment to education and community outreach work deepened during his three years as Assistant Conductor of the Hallé and has flourished since he arrived in post as Chief Conductor of the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie in January 2021. He is equally committed to including new music within his imaginative concert programs.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

Spanish Clarinettist and international soloist Maximiliano Martín is one of the most exciting and charismatic musicians of his generation. He combines his position of Principal Clarinet of the SCO with solo, chamber music engagements and masterclasses all around the world.

Maximiliano has appeared as a soloist and chamber musician in many of the world's most prestigious venues including the BBC Proms at Cadogan Hall, Wigmore Hall, Library of Congress in Washington, Mozart Hall in Seoul, Laeiszhalle Hamburg, Durban City Hall in South Africa, and Teatro Monumental in Madrid. Highlights of the past years have included concertos with the SCO, European Union Chamber Orchestra, and Orquesta Filarmónica de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, amongst others. He performs regularly with ensembles and artists such as London Conchord Ensemble, Doric and Casals String Quartets, François Leleux, Pekka Kuusisto and Llŷr Williams.

Born in La Orotava (Tenerife), he studied at the Conservatorio Superior de Musica in Tenerife, Barcelona School of Music and at the Royal College of Music, where he held the prestigious Wilkins-Mackerras Scholarship, graduated with distinction and received the Frederick Thurston prize. His teachers have included Joan Enric Lluna, Richard Hosford and Robert Hill. Maximiliano was a prize-winner in the Howarth Clarinet Competition of London and at the Bristol Chamber Music International Competition. He is one of the Artistic Directors of the Chamber Music Festival of La Villa de La Orotava, held every year in his hometown.

Maximiliano Martín is a Buffet Crampon Artist and plays with Buffet Tosca Clarinets.

Maximiliano's Chair is kindly supported by Stuart and Alison Paul

Born in London, Cerys started playing the bassoon when she was 15, after first playing the double bass. She studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. After participating in the Erasmus scheme in Amsterdam and graduating, she continued her studies at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague.

Since moving back to the UK, Cerys has enjoyed a varied freelance career, performing with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Hallé, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and The Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. She joined the SCO as Principal Bassoon in September 2021.

Cerys’ Chair is kindly supported by Claire and Anthony Tait

For 50 years, the SCO has inspired audiences across Scotland and beyond.

From world-class music-making to pioneering creative learning and community work, we are passionate about transforming lives through the power of music and we could not do it without regular donations from our valued supporters.

If you are passionate about music, and want to contribute to the SCO’s continued success, please consider making a monthly or annual donation today. Each and every contribution is crucial, and your support is truly appreciated.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Hannah Wilkinson on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk