6 minute read

The Storyteller

Fiction writer Sandi Shelton, ’81, (aka Maddie Dawson) crafts her own happy endings.

By Beth Levine

At the age of 6, when many young girls were perfecting their double Dutch or monkey bars skills, Sandi Shelton, '81, was writing and selling her stories. You might say she was hungry for success. Her mom had refused to provide money for the ice cream man, so Shelton sold a story to a neighbor for 25 cents — enough to buy banana popsicles for the whole family. “To my utter shock, my mother was furious. She bought the story back and said I could never do that again,” Shelton says.

In this case, Shelton was not a good listener. Writing brought possibilities. She had found a way to keep herself in frozen desserts for a lifetime.

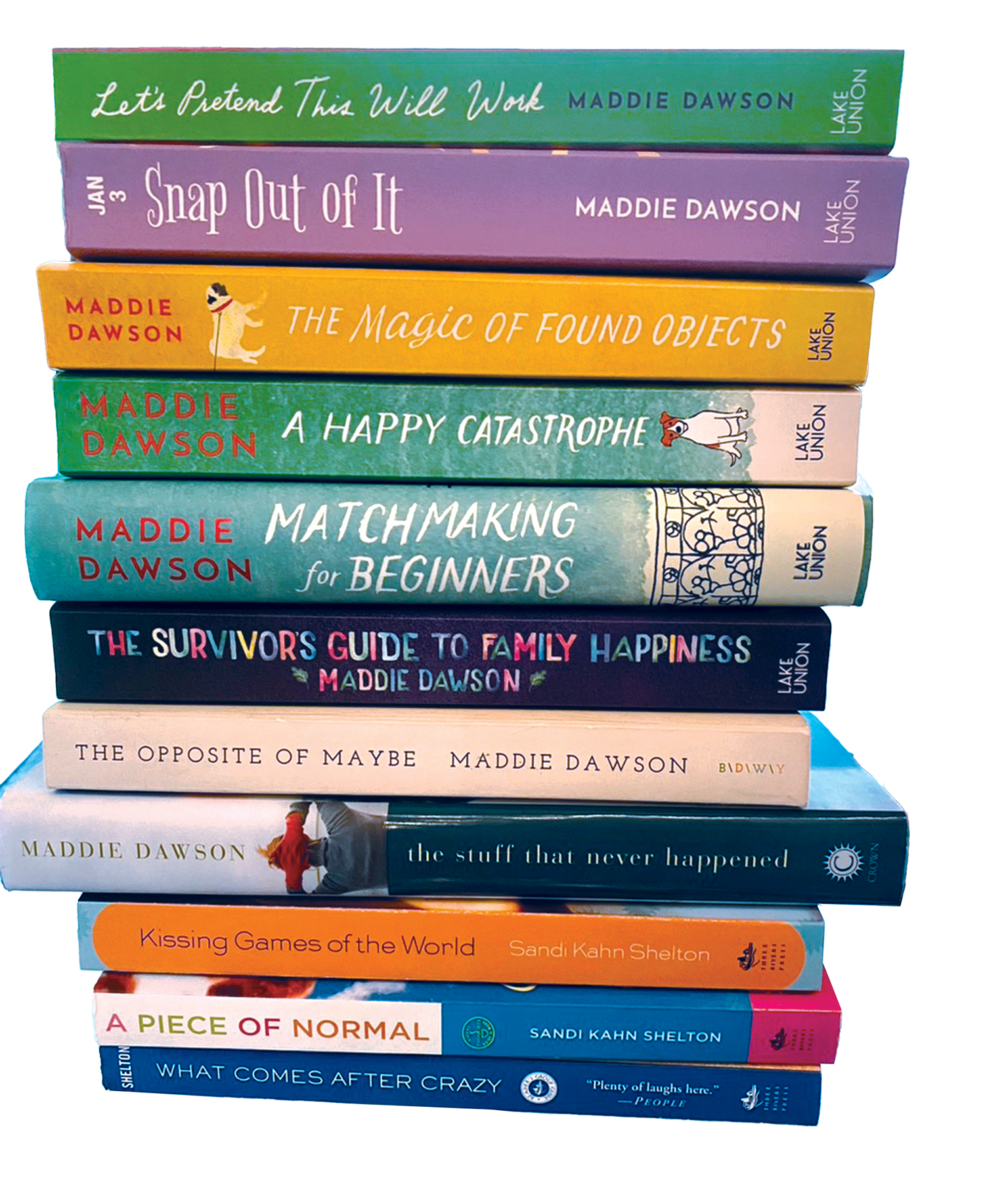

Now 72 and writing from her home in Guilford, Conn., under the pen name Maddie Dawson, Shelton has published 11 novels as well as three nonfiction humor books about parenting. (The latter are based on columns she wrote for Working Mother Magazine and the New Haven Register.)

But fiction is her bread and butter. Shelton’s books have been published in 15 countries, including three novels that were on the bestseller list in Italy. Focusing on humorous literary fiction, what she describes as “people stumbling toward love, family, connection, and hope,” Shelton has earned thousands of five-star reviews on Amazon.

Her latest novel — Let’s Pretend This Will Work — is, like several of her previous books, set in the New Haven area. It’s earned high praise: “Readers looking for a story that captures their full attention and doesn’t let go will enjoy every page of this book,” sums Booklist.

A Writer is Born

Growing up, Shelton kept crafting stories, even attempting to write a novel longhand at age 11. She got to page 100 before realizing she couldn’t remember the point of the story.

Nothing discouraged her, though, not even her first typewriter, which she received at age 12. It was an old Royal that worked perfectly except for a misaligned “e” key.

“E is a pretty frequent letter and very hard to do without, so I would type c, backspace, and do a hyphen,” she recalls. When Shelton finally got a working typewriter, she promptly named a character Reed, just because she could.

Flash forward to 1977, when Shelton, then 25, arrived in New Haven from California, with her graduate-student husband and baby. Her college career had been off and on to that point; the couple had agreed that she’d work while he attended college.

When they divorced in 1981, Shelton needed to finish her college degree to get a decent job to support their now two children. And, well, her writing itch needed scratching. Shelton still longed to be a novelist.

That’s when Southern entered her life. Shelton majored in English but decided to expand her studies and minor in journalism after meeting with Robin Marshall Glassman, then chairwoman of the department. [Glassman, a celebrated journalist and professor, died on Aug. 18, 2009. She is memorialized with an annual scholarship at Southern that bears her name.]

“She welcomed me and allowed me to take a test to skip the prerequisite Journalism 101 course. She and another professor, Jane Hamilton-Merritt, [who retired in 1997,] guided me and convinced me that I could be a journalist,” she says. Their help paid off big-time. Shelton graduated in 1981, winning that year’s journalism award.

After graduation, she was hired at a weekly newspaper, the Branford Review. Three years later, she moved to the New Haven Register, where she wrote news and feature stories for 30 years. As the only single mom on staff, she started writing a weekly column called “Wit’s End,” which won an award from the Associated Press and was picked up by Working Mother. During that time, she also wrote for other magazines including Redbook, Salon, Reader’s Digest, and Woman’s Day. She later returned to Southern to teach journalism and magazine writing for several years as an adjunct. She also taught “Journalism 101” at Gateway Community College.

But the desire to write fiction just wouldn’t let go. Shelton started a novel one summer and worked on it intermittently for the next 17 years. (She constantly had to update it, giving her characters newfangled inventions like answering machines, cell phones, and the internet.) In the meantime, she had gotten remarried to a fellow New Haven Register reporter, and they had another child.

Her life didn’t leave much time for fiction writing. “I wrote in between carpool runs, laundry loads, dioramas, story deadlines, teaching responsibilities, and looking for everybody’s socks,” she says. “I had written and rewritten that novel three separate times, and it had spent more than its fair share of time shoved in a drawer waiting for me to notice it again. I figured I’d be writing it for the rest of my life.”

But here is the crazy part: She sent it to an agent in 2004. When that agent brought What Comes After Crazy to market, it sold in two weeks in a bidding war. “I didn’t know what hit me. This thing that lived in my drawer was a hot commodity. It was surreal,” she says. People magazine called it a “deceptively bouncy, ultimately heart-wrenching novel” and the Boston Globe said it was “funny, sad, and almost painfully accurate about human failings.”

After that publication, she was on her way. Her next book was due in 11 months. A third one followed two years later. When she wrote her fourth novel about an older protagonist, a woman about to turn 50, her publisher instructed her to use a pen name so as not to confuse her usual reader.

“I didn’t really want to do it, but I wasn’t given a choice. I decided to call myself Maddie Dawson, because I was mad,” she says. That fourth novel, The Stuff That Never Happened, took off and became a USA Today bestseller So, Maddie stayed Maddie and wrote seven more novels. Her latest was published in June.

Now affectionately known as “Grammy” to six grandchildren, Shelton has come a long way from the determined young woman who first walked into Glassman’s office at Southern. She delivers a new novel about once every year and a half. Her books are humorous novels that deal with family life, kids, work, parenting, love, death, divorce, and the magic of finding the life you were meant to live, even when it doesn’t look exactly as you pictured. Which, in retrospect, sounds a lot like Shelton’s own life. In fact, aficionados say that reading one of her novels is very much like sitting down to dish with a friend. She says, “I always look for the magic, grace, and laughter of everyday life.” And, not to mention, banana popsicles. ■