6 minute read

A Divine Encounter with Anne Bogart

BY LEAR DeBESSONET

This is the story of how a divine encounter with Anne Bogart changed my life.

It was 2001, and I was 20 years old. I had wanted to be a director since early elementary school, but growing up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, I wasn’t sure what the life of a professional director entailed. Mine was a theatre of church, Mardi Gras, and football games—it was JOY, exuberance, and, most importantly, community. By the time I was 18, though, I was holding a lot of wild existential questions, and an ache filled my heart. I wondered if theatre might be a place for that ache and a place where questions could be not necessarily answered but entered. When my college directing mentor, Betsy Tucker, pointed me to Anne Bogart’s essays, I knew I had found my Guide.

I’d like to phrase this gently, but I can’t—I became OBSESSED with Anne Bogart. First, I read her book VIEWPOINTS, and then I read everything else I could find about her (reviews of her shows, interviews). I got a long black sweater like one I saw her wear in a picture and felt oh-so-directorly when I wore it. Anne appeared in my dreams, usually gold and glowing, one time legit sitting on a throne (I know, I know). She spoke about directing in a way that to me signaled spiritual practice. The director was approaching the altar with fear and awe, organizing a rehearsal room to leave space for a visit from the Divine. Because Anne devised original pieces out of a question, I believed her method would allow me to crack into the longing in my spirit, the rageful despair and great hope I felt, and the questions about God in the world.

That summer, I attended the SITI Company’s training at Saratoga Springs, a rite of passage for many. There, I got to see her work. It was for me, as Anne might say, an aesthetic arrest. Never before had I understood that the languages of space, body, movement, breath, and lighting speak as powerfully as text. Her work moved me in a way I didn’t understand. I’d find myself crying at the sheer beauty of when the company held completely still. When I watched Will Bond perform his solo piece, BOB, I didn’t realize until the end that I had been holding my breath, leaning forward so far I almost fell off my chair. Anne’s work was a romance and an awakening. And I had no idea how she made it, but I knew I wanted to learn.

Kelly Maurer leading a SITI Company training

PHOTO Michelle Preston

That summer, Anne taught me that there was actual power in being scared shitless. My mom used to tell me and my sister that if we were ever in a shipwreck, we shouldn’t waste time fighting the initial sink—we should let ourselves float all the way to the bottom and then push up from the ground with all our might. If kinda scared was the float down, scared shitless was the ground from which you could rocket up.

Anne taught me that this type of fear is part of making art. It doesn’t mean you’re doing something wrong—it means you are doing something right. Terror means you have your hand on the Ouija board. It means that’s the moment when you have to act—make a choice.

Even the Suzuki method her company practiced was a physical metaphor for enduring discomfort and rising from the ashes. (Sidenote: I was never an athletic person, so the idea that a director needed physical training that involved stomping around a dance studio in biking shorts and socks scared the bejeezus out of me, but hey! I faced my fear!) That summer was a crucible in which something new could be born. Less than a year later, during my last semester in college, I faced the question of how to begin. How does a director begin? How does an artist make a life? I had no idea. I thought I might want to move to New York, but I had also grown up to believe New York was a place of danger and sin, and that a young woman from the Deep South might get smushed at her first step off the bus.

As spring approached, I felt inspired by a plan. I would take a discernment trip to New York City. I bought a cheap plane ticket (it was a strange time, so shortly after 9/11) and stayed with the one friend I knew. I mostly spent those days walking around the city, imagining what it might be like to live there.

After two days, it was time to fly home. My heart was full. I sat down in LaGuardia Airport and opened my prayer journal onto my lap. I was writing earnestly, praying God would see me in my smallness and confusion and guide me, when I glanced up—

There, standing 10 feet in front of me at the airport, reading a screen above my head, was Anne Bogart.

A fluorescent halo of light crowned her head.

Beat.

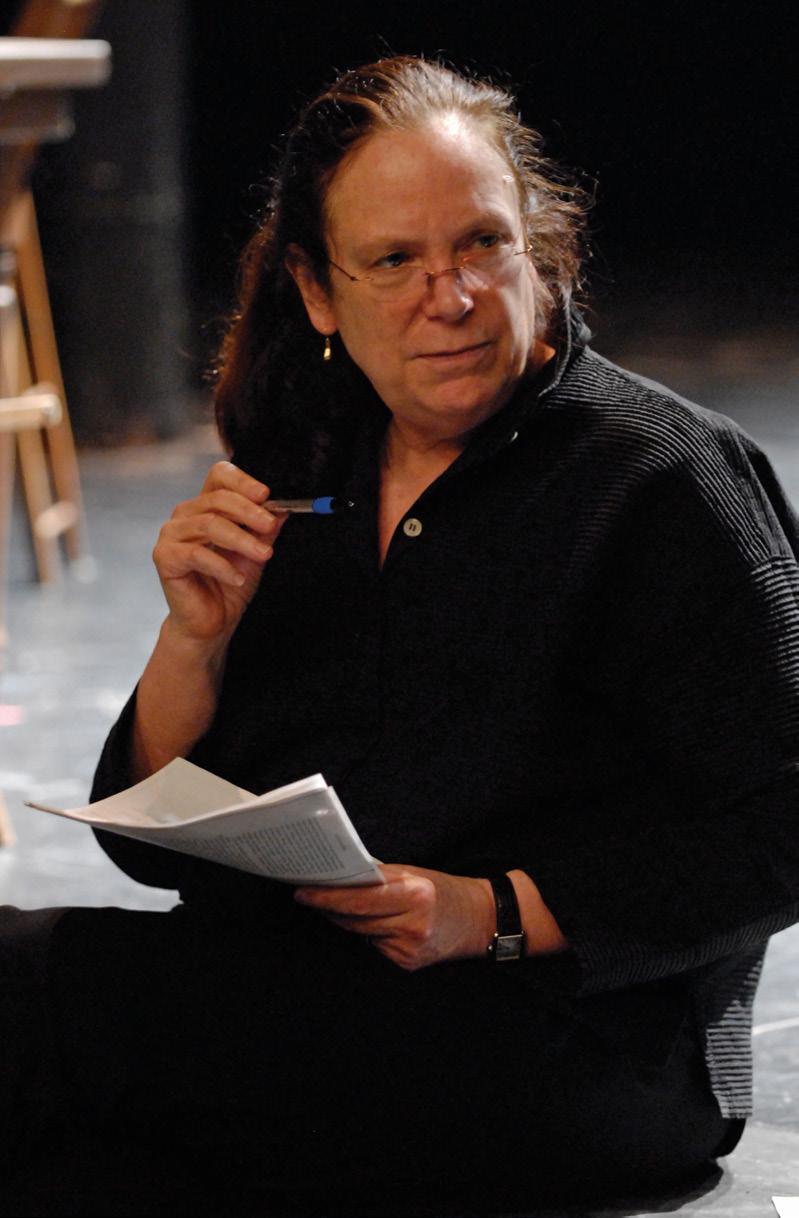

Anne Bogart

PHOTO Michael Brosilow

I thought I might be having a vision, but after blinking for 10 seconds, I determined she was actually there. Anne Bogart was checking her flight information, and I knew she would likely walk away soon. I was scared shitless, but THIS WAS MY MOMENT. The universe had opened a door for me, and I had to walk through it.

I stood and started walking toward her, hoping my head wasn’t visibly pulsating given that my heart was now beating LOUDLY in between my ears.

I didn’t know if she would remember me (that summer with SITI, Anne had also been on a European tour and most of my contact with her was in a large group), so I introduced myself before there could be a pause. Anne in her typical graciousness said she was glad to see me.

ME: What are you working on right now?

ANNE: Oh, I’m devising a new version of MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM set in the Dust Bowl. We are touring ROOM and BOB and preparing to make a new piece inspired by Leonard Bernstein.

ME: Wow, that sounds incredible!

ANNE: And what are you working on, Lear?

(Me? You want to know about me?)

ME: I’m devising an original piece exploring the question “What does it mean for a woman to pursue ecstasy?” The text is primarily Lady Macbeth’s, but I also use found text from FORBES magazine, Heidegger, and SEX AND THE CITY.

ANNE: Mmmm. That’s very interesting. Do you know the Latin root of the word ecstasy?

ME: I don’t believe I do—

ANNE: Ex-stasis. To stand outside of oneself.

[Pause for Lear’s mind to be blown again.]

[Carry on for a few minutes with Lear asking more questions about the Dust Bowl piece, but Lear becomes aware of the time and realizes this blessed window will close when Anne has to catch her flight. Lear doesn’t know what to say, but she knows she has to say something…]

ME (clearing throat, speaking louder): Anne? Do you ever take assistant directors?

ME: Can I be your assistant director?

Beat. Beat. Beat.

ANNE: When would you like to start?

Those four lines of dialogue altered the course of my life. In August 2002, I would move to New York to become Anne Bogart’s assistant director. She changed my life—first with her words, then with her work, and finally with her YES.

In the years since, I have tried to find words to adequately thank Anne (impossible)—to say “Anne! Do you realize what that moment in the airport meant to me? My whole life might have been different if it weren’t for you!!!” And she usually smiles a small smile, because she is humble and perhaps too used to hearing that she changed someone’s life.

Lear deBessonet is the Artistic Director of Encores! at New York City Center and Founder of the Public Works program at the Public Theater, where she served as Resident Director for eight seasons.