Maritime Defense of America

The Creesys' Record-Run Mutiny and the Naval Academy

Efie M. Morrissey to Greenland

Minneapolis

MINNESOTA

Red Wing Dubuque

WISCONSIN

Davenport

Fort Madison

Minneapolis

The Creesys' Record-Run Mutiny and the Naval Academy

Efie M. Morrissey to Greenland

Minneapolis

MINNESOTA

Red Wing Dubuque

WISCONSIN

Davenport

Fort Madison

Minneapolis

From the French Quarter to the hometown of Mark Twain, experience the best of this legendary river. On an 8 to 23-day journey, explore Civil War history and travel to the epicenter of American music as you cruise in perfect comfort aboard our brand new American Riverboat™.

Small Ship Cruising Done Perfectly ®

Hannibal Alton

MISSOURI

Red Wing Winona

MINNESOTA

IOWA

Dubuque

Davenport

Fort Madison

WISCONSIN

Cape LOUISIANA

ARKANSAS

ss

St. Paul Mississipp i R i rev

ILLINOIS

Hannibal Alton

MISSOURI

Memphis

New Madrid

MISSISSIPPI

St. Louis

Baton Rouge

Houmas House

ARKANSAS

Greenville

M ississipp iRiver

Natchez Vicksburg

LOUISIANA

Baton Rouge

Houmas House

TENNESSEE

Memphis

MISSISSIPPI

Greenville

Vicksburg

St. Francisville

Natchez

St. Francisville

Cape Girardeau New Orleans

Oak Alley

24

44

21

Return of the Ida May

by Bill Bleyer24 Mutiny Aboard the US Brig Somers

by William H. White30 A Secret Mission in Wartime Greenland

Louise Arner Boyd aboard the Efie M. Morrissey by

Joanna Kafarowski36 Captain and Navigator, Husband and Wife: Josiah and Eleanor Creesy’s Record Run

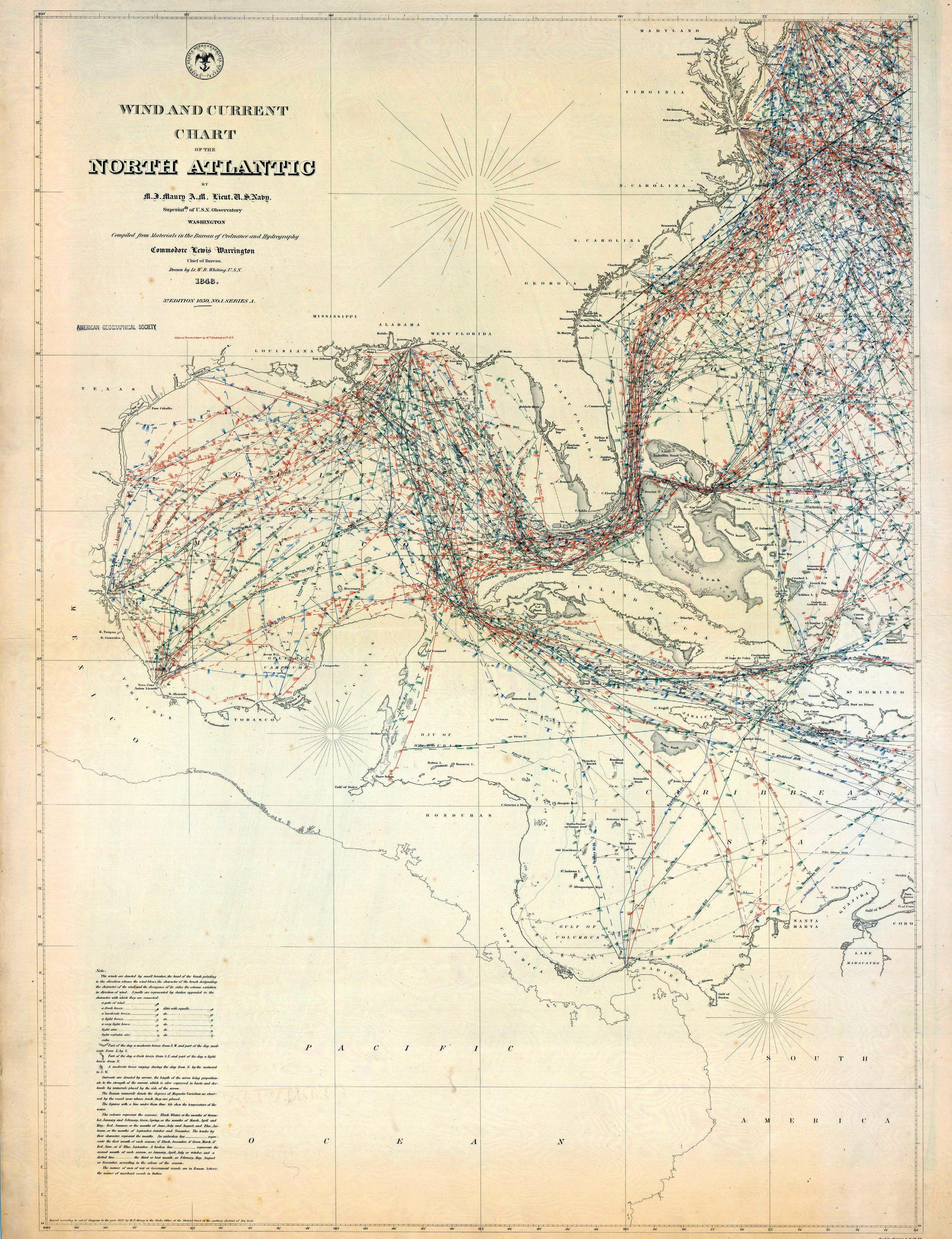

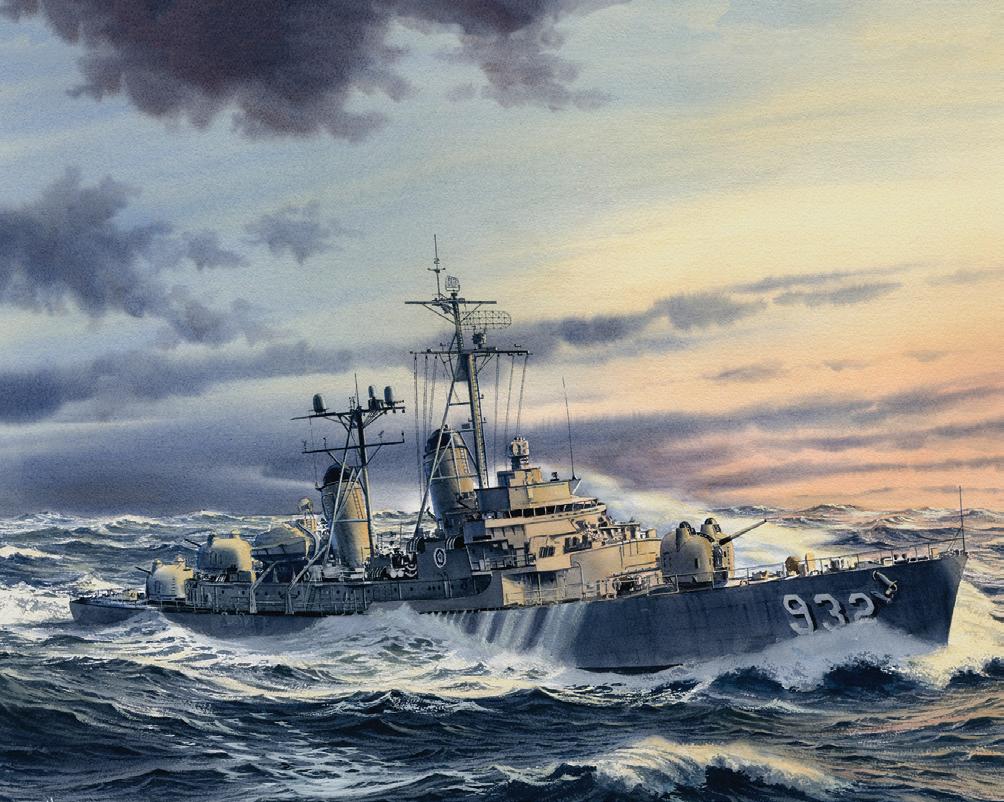

by David Hirzel44 A Maritime History of the United States: The Creation and Defense of a Nation by Charles Raskob Robinson and Len Tantillo

illustrated by the American Society of Marine Artists

4 Deck Log

6 Leters

10 NMHS Cause in Motion

18 Fiddler’s Green

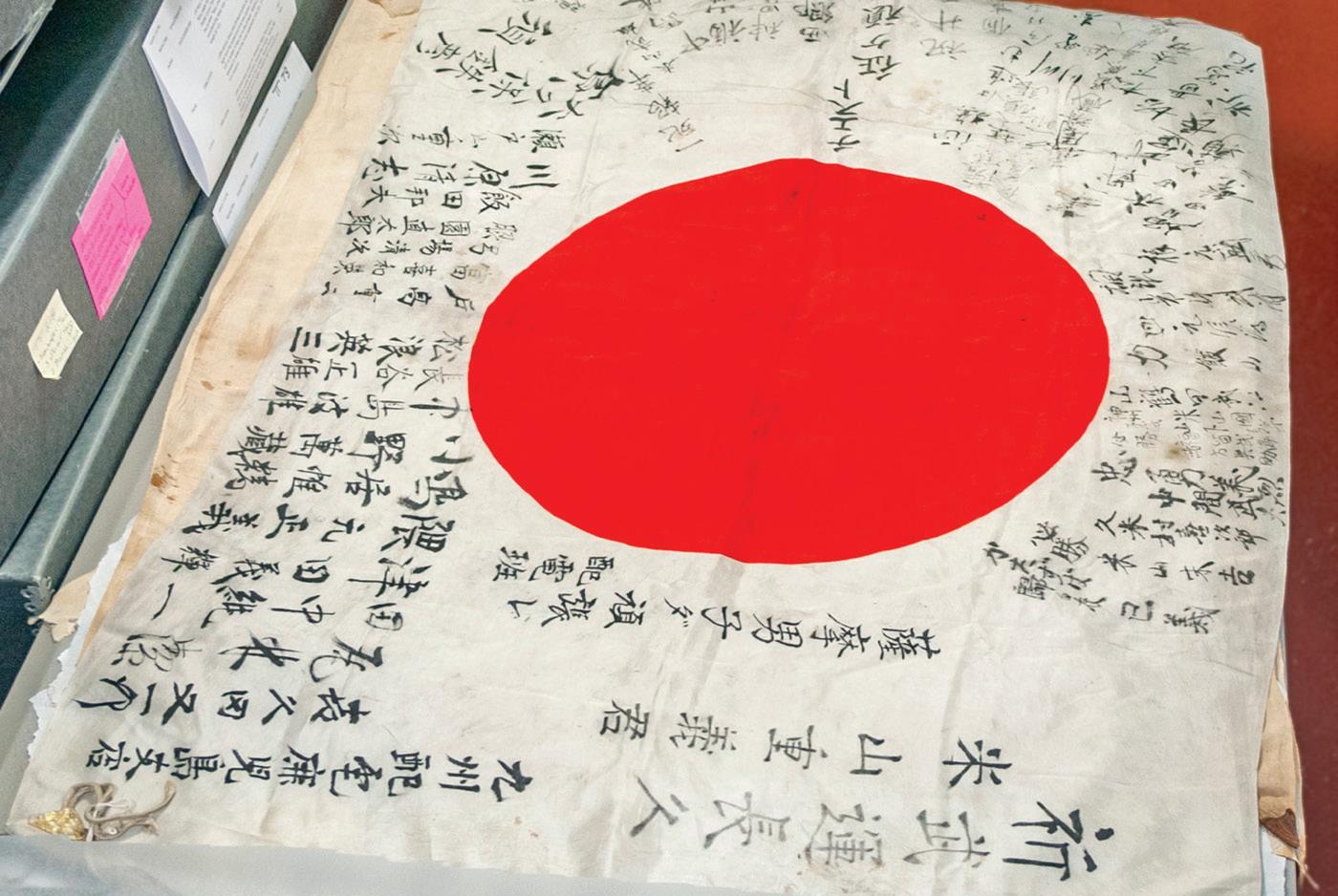

42 Curator’s Corner

54 Sea History for Kids

60 Marlinspike News

63 Ship Notes, Seaport & Museum News

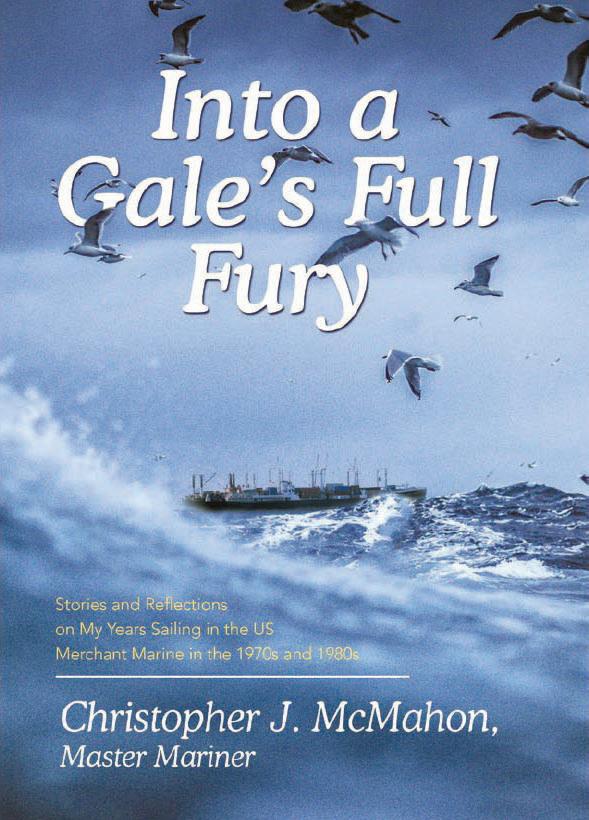

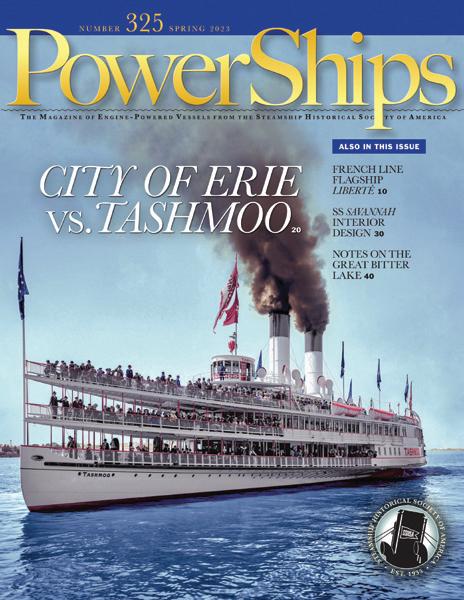

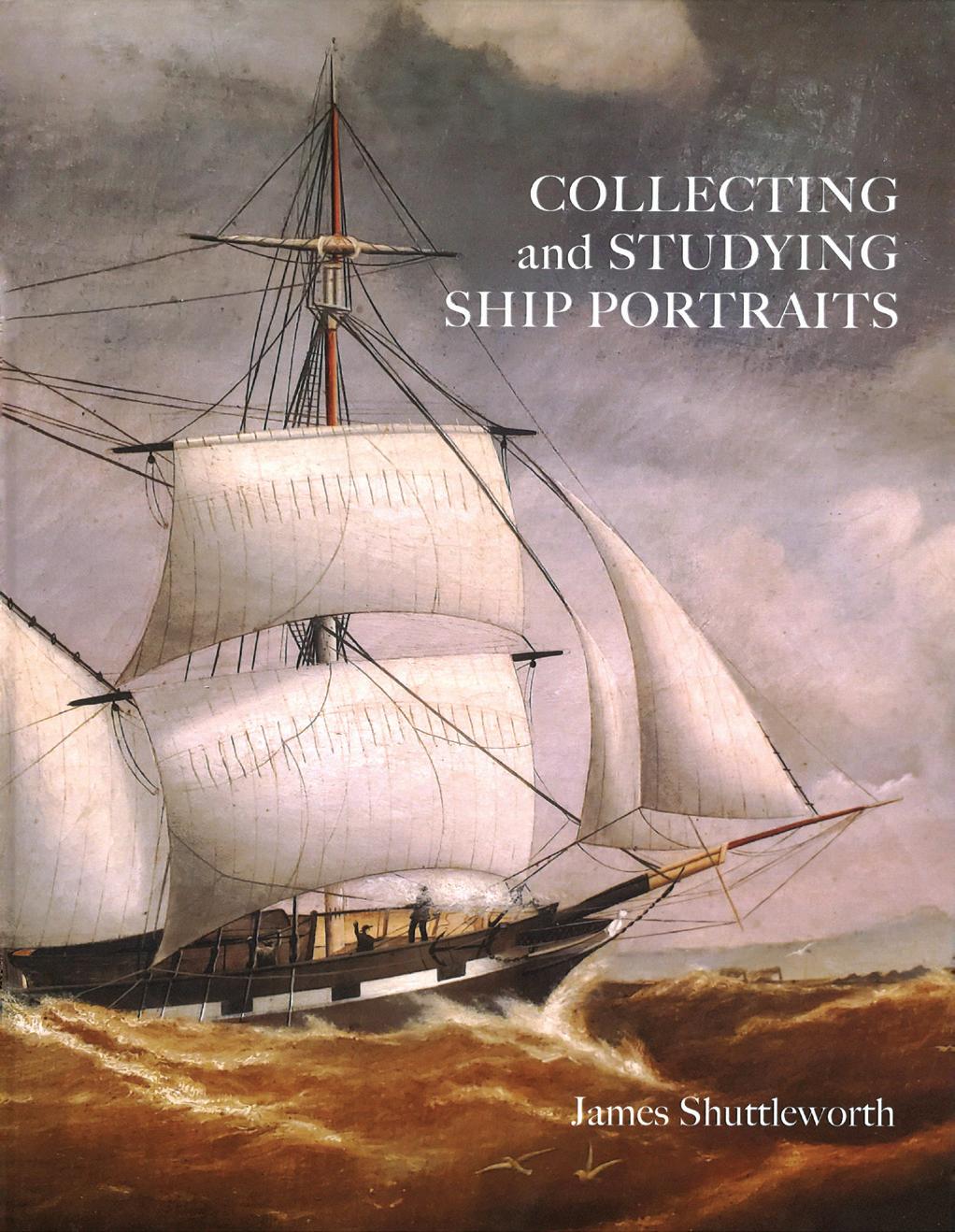

73 Reviews

Cover: Supercarrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) by Robert Gant Steele watercolor, 14 x 18 inches (see article pp. 44–53)

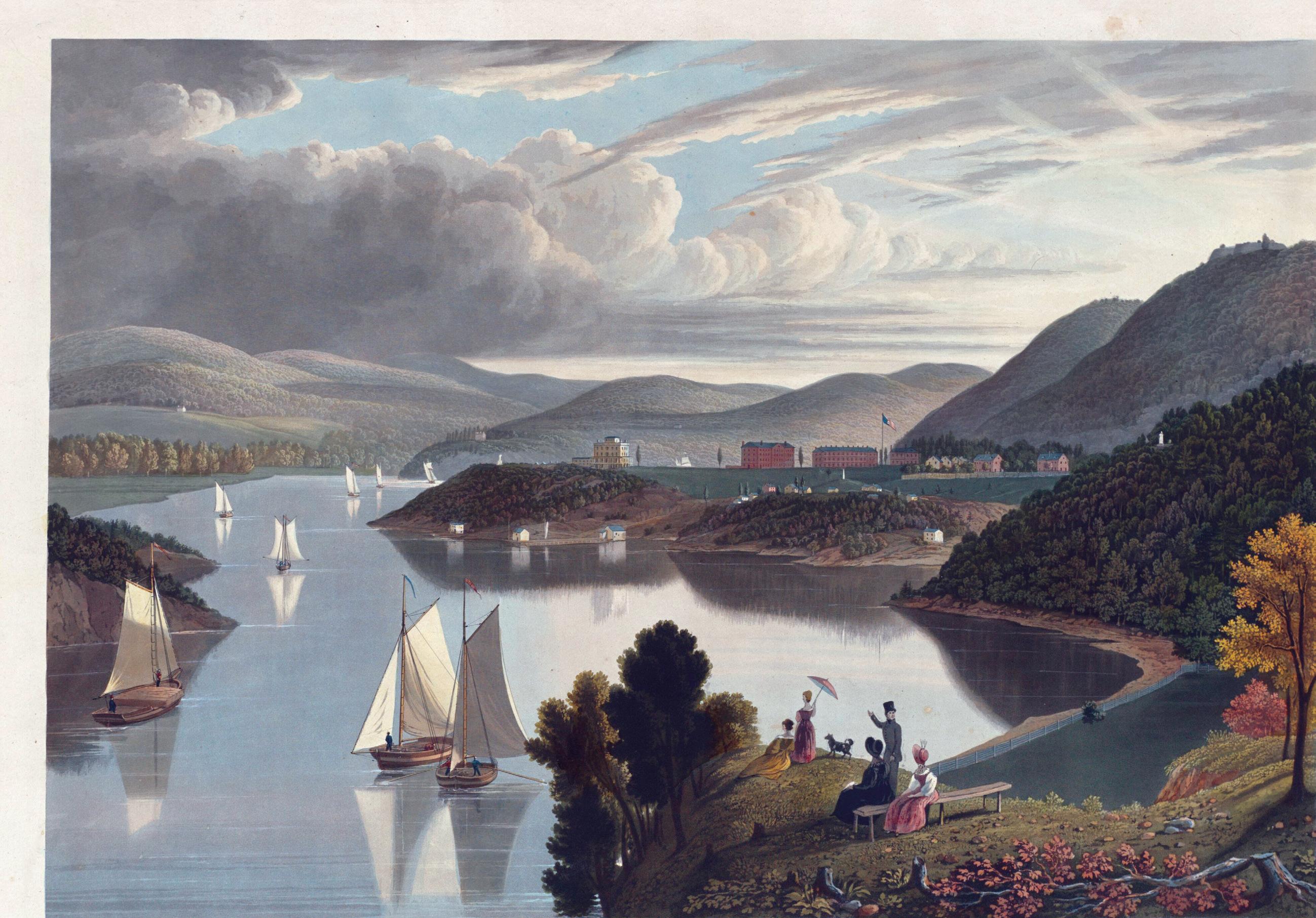

In all the years NMHS has been based in Peekskill, New York (more than 30!), we have never held our annual meeting at our headquarters. We are excited to invite you to join us this year to visit the Hudson River Valley and tour our ofce, which is also home to the new Ronald L. Oswald Maritime Library.

For millennia, libraries have served a critical role as repositories of knowledge and culture. Since its founding more than 60 years ago, NMHS has been collecting and accepting donations of maritime books and collections, and now has a library fully accessible to the public. On Friday afternoon (4:30–6:30 pm), 19 July 2024, we invite our members to visit our headquarters and check out the new Ronald L. Oswald Maritime Library and join us in the celebration of its debut. With more than 5,000 volumes, it is one of the largest maritime libraries in New York State—and what a treasure it is. You can peruse the collection online at www.seahistory.org/education/library/ and we look forward to your joining us in person for the celebration.

Te Hudson River Valley is so rich with history and beauty it is hard to pare down what we can cover in a weekend. We have secured a block of rooms at the Overlook Lodge of the historic Bear Mountain Inn, within the beautiful Bear Mountain State Park. We’ll be hosting our trustees’ dinner there on Saturday night for those who care to join. T is annual dinner is an intimate and casual a f air where we welcome our new trustees and get to know our local presenters and members.

Friday morning we will enjoy a boat excursion on the Hudson, after which many of our business neighbors at the Hat Factory, the 1870s historic brick building where we are headquartered, will open their doors to you before our afternoon library celebration. Saturday morning starts with a continental breakfast followed by the annual business meeting, local maritime history presentations, and lunch at the Cortlandt Yacht Club. In the afternoon we will make our way over to the US Military Academy at West Point and enjoy a tour of this historic and renowned institution.

If you can stay for Sunday, there are so many places in the area that you will want to visit: Washington’s Headquarters in Newburgh; FDR’s home and library at Hyde Park; the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring; Bannerman’s Island, the renowned modern art museum Dia Beacon, historic homes open for tours, plus kayaking, or hiking the Appalachian trail. Te list of things to do in the region is endless and we will be happy to provide ideas and help organize your visit to speci fc sites, depending on interest.

One place I want each of you to join me at is the last block of Peekskill’s own yellow brick road. Some claim it was the inspiration for Frank Baum’s yellow brick road when he wrote the Wizard of Oz. Whether or not that is true, it has come to represent the importance of following our dreams, of going into our adventures with hope and curiosity. Standing on the yellow brick road, you can see the river, the railroad, and the highway, and you too will believe that to follow the yellow brick road leads you to the world and adventures beyond.

I look forward to greeting you, our members from around the country and around the globe, at our 61st NMHS Annual Meeting.

—Burchenal Green, NMHS President EmeritusPETER ARON PUBLISHER’S CIRCLE: Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald, William H. White

OFFICERS & TRUSTEES: Chairman , James A. Noone; Vice Chairman, Richardo R. Lopes; Vice Presidents: Deirdre E. O’Regan, Wendy Paggiotta; Treasurer, William H. White; Secretary, Capt. Je f rey McAllister; Trustees: Charles B. Anderson; Walter R. Brown; CAPT Patrick Burns, USN (Ret.); CAPT Sally McElwreath Callo, USN (Ret.); William S. Dudley; David Fowler; Karen Helmerson; VADM Al Konetzni, USN (Ret.); K. Denise Rucker Krepp; Guy E. C. Maitland; Salvatore Mercogliano; Michael Morrow; Richard P. O’Leary; Ronald L. Oswald; Timothy J. Runyan; Richard Scarano; Jean Wort

CHAIRMEN EMERITI: Walter R. Brown, Alan G. Choate, Guy E. C. Maitland, Ronald L. Oswald; Howard Slotnick (1930–2020)

FOUNDER: Karl Kortum (1917–1996)

PRESIDENT EMERITUS: Burchenal Green, Peter Stanford (1927–2016)

OVERSEERS: Chairman, RADM David C. Brown, USMS (Ret.); RADM Joseph Callo, USN (Ret.); Christopher Culver; Richard du Moulin; Gary Jobson; Sir Robin Knox-Johnston; John Lehman; Capt. James J. McNamara; Philip J. Shapiro; H. C. Bowen Smith; Capt. Cesare Sorio; Philip J. Webster; Roberta Weisbrod

NMHS ADVISORS: John Ewald, Steven Hyman, J. Russell Jinishian, Gunnar Lundeberg, Conrad Milster, William Muller, Nancy Richardson

SEA HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY

BOARD: Chairman, Timothy Runyan; Norman Brouwer, Robert Browning, William Dudley, Lisa Egeli, Daniel Finamore, Kevin Foster, Cathy Green, John O. Jensen, Frederick Leiner, Joseph Meany, Salvatore Mercogliano, Carla Rahn Phillips, Walter Rybka, Quentin Snediker, William H. White

Sea History e-mail: seahistory@gmail.com

NMHS e-mail: nmhs@seahistory.org

Website: www.seahistory.org

Phone: 914 737-7878

Sea History is sent to all members of the National Maritime Historical Society.

MEMBERSHIP IS WELCOME: Afterguard $10,000; Benefactor $5,000; Plankowner $2,500; Sponsor $1,000; Donor $500; Patron $250; Friend $100; Regular $45. Members outside the US, please add $20 for postage. Individual copies cost $5.99.

NMHS STAFF: Executive Director, Burchenal Green; Vice President of Operations, Wendy Paggiotta; Senior Sta f Writer, Shelley Reid; Business Manager, Andrea Ryan; Manager of Educational Programs, Heather Purvis; Membership Coordinator, Marianne Pagliaro

SEA HISTORY: Editor, Deirdre E. O’Regan; Advertising Director, Wendy Paggiotta

Sea History is printed by Te Lane Press, South Burlington, Vermont, USA.

Experts on the 1813 US landing at York will have noticed historical inaccuracies in the scene that I provided for Dr. Bill Dudley’s article on the amphibious raids on Lake Ontario (Sea History 185, Winter 2023–24). T at Photoshop sketch was an early version and my updated transmission for its correction went awry. My fault with apologies. T is art efort has undergone numerous historian-guided corrections, all done with multiple layers on Photoshop as part of the process; the f nal large oil painting had not yet been completed. Here is the corrected and more accurate version, and readers will be relieved to note that the Battle of York was not smokeless.

Pete R indlisbacherKaty, Texas

Mike Rauworth was such an incredible and important person to the maritime heritage community; he will be well missed. I loved his features in Sea History and have been known to quote his quirky phrases. He was always fun. I snapped this shot of him with our chairman (now chairman emeritus) Ron Oswald when he received our award for the best feature article in Sea History in 2017–18.

I encourage the maritime community to support the leadership of Tall Ships America as they chart their course after the loss of both Bert Rogers (executive director of Tall Ships America at the time of his death in 2018), and Mike in such a short time. (Read about Mike Rauworth on page 18 of this issue.)

Burchenal GreenNMHS President Emeritus

I would like to commend Sea History for the article on USS Tampa and the e fort to bestow, posthumously, the Purple Hearts that are due the 130 men who were lost with their ship when it

was torpedoed by a Uboat in 1918. Who was Frank Garrett/Charles Green? In some ways, he was a nobody. A runaway teenager who joined the Coast Guard during World War I under an assumed name. But does that make his sacri fce less important than others whose names we might be more familiar with? Not at all.

This is a photo of a 17-year-old Charles Parkin, his Purple Heart medal, and the American flag presented to his family in 2019. Parkin was a shipmate of Charles Green (whom he would have known as Frank Garret) when the Tampa was sunk with all hands in 1918.

We honor our war dead as a reminder of true American patriots who willingly serve their country with honor and who made the ultimate sacri fce. Tat some of our fallen servicemen (and women) have no family to keep their memory alive should not devalue their service. I applaud the author of the article, Charles Meyer, and Green’s relatives (two and three generations later), who kept up the e fort to restore his name, to see that his Purple Heart is awarded, and for bringing us his story.

M artin C ameron Purchase, New York

Shop for Nautical Gif s, Marine Art Prints, and Books at the NMHS Ship’s Store

www.seahistory.org/store

We carry: 100s of , , in basswood, mahogany, and cherry.

of sailing ships, power vessels, and pond models.

All our contain: a pre-carved instruction guidebook, display base, and pedestals.

See our catalog online at:

1 Strawberry Lane, Norfolk, MA 02056 978-462-4555

The Descendants of Whaling Masters encourage you to honor your whaling ancestor with a membership. DWM celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2024 and is eager to hear from anyone who had a relative who served on board a WHALER.

The Descendants of Whaling Masters encourage you to honor your whaling ancestor with a membership. DWM celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2024 and is eager to hear from anyone who had a relative who served on board a WHALER.

The Descendants of Whaling Masters encourage you to honor your whaling ancestor with a membership. DWM celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2024 and is eager to hear from anyone who had a relative who served on board a WHALER.

www.whalingmasters.org

www.whalingmasters.org

www.whalingmasters.org

Inquiries to:

Inquiries to: whalingmasters@yahoo.com

whalingmasters@yahoo.com

Inquiries to: whalingmasters@yahoo.com

J.P.URANKERWOODCARVER

THETRADITION

WWW.JPUWOODCARVER.COM

Foundation Franklin

An excellent article in the last issue (“Tugboats to Remember” in Sea History 185) on the hardworking vessels that are all too often ignored in concentrating on the beautiful, or famous, or heavily armed. I was particularly pleased to see the painting of the former HMS Frisky, known as Foundation Franklin, during her career as a salvage tug. Her dramatic story is retold in Farley Mowat’s book Te Grey Seas Under (1964). Parts of Foundation Franklin are preserved in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and her bell is located in the ofces of Svitzer Canada Ltd. at the same wharf from which Foundation Franklin operated all those years ago.

Charley Seavey Rockport, Massachusetts

Corrigenda: Foundation Franklin

As a marine researcher, illustrator, lecturer, writer, and editor on shipping and tugs in particular, I feel obliged to point out some errors in the winter issue regarding the salvage tug Foundation Franklin, which was based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where I reside. Te cargo ship Firby ran ashore in the Strait of Belle Isle, a narrow body of water separating the northern peninsula of the island of Newfoundland from the Canadian mainland. It is assuredly not in France, which would explain why it was a relatively short tow of 625 miles to Quebec City.

Te name of the primary port in Newfoundland is St. John’s (with an apostrophe). It is important to give it the correct spelling to avoid confusion with the port of Saint John, New Brunswick. Foundation Maritime did not purchase the Bustler -class tug Samsonia, but rather it was chartered from the Admiralty from 1946 to 1952. It was renamed Foundation Josephine for the duration of the charter then reverted to Samsonia when returned.

Te artist/author presumably relied on the books Grey Seas Under and Te Serpent’s Coil, written by Farley Mowat. Mowat was well known for not letting facts get in the way of a good story. Despite the reverence tug enthusiasts have for Mowat’s works, they are not holy writ. Fact checking is essential using his works—and the works of others, too. I do admire Sea History. I read it regularly and wish you and the magazine best wishes for 2024.

M alcolm B. (M ac) M ackay Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

On a cruise you can tour museum spaces, bridge, crew quarters, & much more. Visit the engine room to view the 140-ton triple-expansion steam engine as it powers the ship though the water.

Reservations: 410-558-0164, or www.ssjohnwbrown.org

Last day to order tickets is 14 days before the cruise; conditions and penalties apply to cancellations.

Te photo of the Victory Chimes departing Rockland Harbor under tow and the accompanying write-up in “Ship Notes, Seaport, and Museum News” on p. 69 of the winter issue of Sea History inspired this poem.

R ichard Dey Needham, MassachusettsFrom the Editor: Te historic three-masted schooner Victory Chimes was sold at auction last year to Alex and Miles Pincus, owners of Crew NY, which operates two other historic schooners that they have converted for use as foating oyster bars in New York. (www.crewny.com)

With three masts all sky-writing, there was no mistaking her along the coast, among the coastal islands, not from afar,

nor near with mattresses spread out on cabin tops and many passengers spread out on them without their tops,

beneath the sun, the schooner aslant, making her way, the tall white sails all drawing, drawing, drawing, across the bay.

“Sin ships!” Cap called ’em, the schooners out of Camden and Rockland. Youngsters in the school-ship Tabor Boy, we hardly understood why with such joy we laughed so hard.

Having hauled out of Baltimore fertilizer, coal and lumber, then out of ports in Maryland and Maine passengers escaping lives mundane, from Rockland Harbor

she’s being towed to North Moore Street, still undefeated, to join a feet of oyster bars freshly painted, rigging taut and tarred, sails still bent on, all drawing, drawing, drawing f rm white collars

under awnings. From Maine she’s gone but not her kind; and for these windjammers, the mattresses she leaves behind.

—Richard DeyNational Maritime Awards Dinner chairs, Samuel F. Byers and Kristen L. Greenaway, along with NMHS Chair CAPT James A. Noone, USN ( Ret .), and Founding NMAD Chair Philip Webster, invite you to join us for our annual gala in Washington, DC, to honor three esteemed individuals: Major General Charles F. Bolden Jr., USMC (Ret.); Dr. William S. Dudley ; and Dawn Riley

America’s ambassador of sailing, Gary Jobson, will be our emcee. NMHS Vice Chairman Richardo Lopes and Voyage Digital Media will provide video introductions

on the awardees. Guests will enjoy a special performance by the US Coast Guard Academy Cadet Chorale, directed by Dr. Daniel R. M. McDavitt, DMA . Te Combined Sea Services Color Guard will present the colors.

In addition, the NMHS Maritime Art Gallery, hosted by American Society of Marine Artists President and award-winning artist Patrick O’Brien, will feature a selection of contemporary maritime art for sale (preview on pages 14–17). We look forward to welcoming you to this special evening as we pay tribute to these remarkable honorees.

Major General Charles F. Bolden Jr., USMC (Ret.)

General Charles Bolden will receive the NMHS 2024 Distinguished Service Award for his extraordinary career in service to our country and his e forts to explore and understand the universe. T is award recognizes his accomplishments as a US Marine aviator and astronaut, and for his leadership roles as Deputy Commandant of Midshipmen at the Naval Academy, Commanding General of Operation Desert Tunder in Kuwait, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Administrator.

Bolden grew up in Columbia, SC. Following his graduation from the US Naval Academy in 1968, he joined the Marine Corps. He was based at the “Rose Garden” in T ailand during the Vietnam War and few more than 100 combat missions.

He later earned his Master of Science degree at the University of Southern California and graduated from the US Naval Test Pilot School in Maryland. As an astronaut from 1986–1994, Bolden logged over 680 hours in space and completed four missions as either pilot or commander.

Your perspective really changes when you see the thin blue line that is our atmosphere. You get an opportunity to see that we live in a single ocean. We live on a water planet. The continents are just bodies of land that manage to just stick up high enough that they protrude above the ocean.

His space shuttle f ights include the Discovery mission that deployed the Hubble Space Telescope and the Atlantis mission that carried the f rst space lab dedicated to understanding

Earth’s climate and atmosphere. His f nal f ight was aboard Discovery in 1994, the f rst joint US-Russia mission.

After completing his service as an astronaut in 1994, he served as the Assistant Commandant of Midshipmen at the Naval Academy, and in 1998 as the Commanding General of the Marine Expeditionary Force attached to Operation Desert Tunder in Kuwait. He served as the Commanding General of the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, California, prior to his retirement from the Marine Corps in 2003 after 34 years of devoted service.

President Barack Obama nominated Bolden to head up NASA in 2009. “Te combination of my leadership training at the Naval Academy and what I learned in the opera-

tional forces of the Marine Corps prior to becoming an astronaut stood me in good stead. It prepared me very well to lead.” Bolden oversaw the Mars Curiosity Rover landing, the Juno Space Probe orbit of Jupiter, and the development of the James Webb Space Telescope, launched in 2021.

Refecting on his career, Bolden stated, “I am an ordinary human being who has been a forded the opportunity to do some incredible things. I have had the gift of working with some of the most phenomenal people in the world–both in the Marine Corps and in NASA.” Te important part of his work, he reminds us, is the people, and he encourages young people to follow their passions and be persistent in pursuing their dreams.

Dr. William Dudley will receive the David A. O’Neil Sheet Anchor Award in recognition of his inspired and dedicated service to NMHS and its mission to promote awareness of maritime history. A prominent naval historian, Dudley has served as a trustee for the Society since 2012 and is the trustee liaison for Sea History.

NMHS is like a second family to me. There’s always a challenge—that is a given. But that is what it is about, enjoying the challenge, and I have always been happy to be a part of it.

Dr. Dudley and his wife, Donna, are past co-cha irs of the National Maritime Awards Dinner (NMAD), and he has been an active member of the NMAD committee.

Dudley’s love of the sea and all things naval has been a lifelong passion: “I am devoted to sailing, devoted to the Navy, and that has been a good part of my life... I’m a saltwater guy. I’ve got it in my blood.”

Dr. Dudley started his relationship with the Navy through active duty, serving on a destroyer and in the Selected Reserve from 1960 to 1963. After earning a PhD from Columbia University in 1972, he taught history at Southern Methodist University and became a supervisory historian at the Naval Historical Center in Washington, DC, in 1977.

Dudley was the Director of Naval History for the US Navy from 1995 to 2004, concurrently serving as Director of the Naval Historical Center, Curator for the Navy, and

Coordinator of Navy Museums. He was promoted to Senior Historian in 1990 and later became the Director of the Naval Historical Center (now known as the Naval History and Heritage Command), a position he held until his retirement in 2004.

He is the author of many reviews, articles, monographs, and documentary editions. Renowned as a preeminent scholar of the War of 1812, he is the original editor of the fourvolume series, Te Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. His published works include Maryland: A History (2010), which received two best maritime heritage book awards; Te Naval War of 1812: America’s Second War of Independence (2013), co-authored with Scott Harmon; and his latest book, Inside the US Navy of 1812–1815 (2021). Current projects include a book on the antebellum US Navy 1816–1861.

Dudley served as president of the North American Society for Oceanic History (NASOH) and the Society for History in the Federal Government. He is the former Chair of the Maritime Committee of the Maryland Historical Society, a past member of the Board of Directors of the Naval Historical Foundation, and the Board of Governors of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

He is the recipient of the US Navy Superior Civilian Public Service Award and the NASOH K. Jack Bauer Award for Scholarship and Service. In 2014 he was honored with the Dudley W. Knox Naval History Lifetime Achievement Medal from the Naval Historical Foundation.

Dawn Riley will be presented with the NMHS 2024 Distinguished Service Award in recognition of her remarkable sailing career, particularly for her role as a mentor and educator training premier-level sailors for future Olympic, America’s Cup, and other world-class sailing competitions. Riley has overcome barriers that previously excluded women from such pinnacle events in the sailing world. As the executive director of Oakcli f Sailing, she is leading the movement to invigorate the sport of sailing and fulf lling Oakclif ’s mission: Build American Leaders T rough Sailing—

We are building American leaders through sailing— yes. But what we try to do above everything is teach them what’s the best practice. How are you a leader? How are you contributing? No mater whether you are in the Olympics, sailing around the world, or running for ofice, you have to be a good human being and be counted on to do what’s right.

As a young teen, Riley declared that she was going to sail in the America’s Cup and race around the world. She has achieved the dreams of her youth and much more as a competitive racer, a champion sailor, and now a powerful role model to aspiring young sailors. “ Tere is no better way to be on a team than on a boat; you all have to work together to get to the f nish line. You literally can’t go home. You can’t go to the sidelines. You are on a boat!”

Riley was part of the f rst-ever all-female crew in the 1989–90 Whitbread Race aboard Maiden, which was documented in the 2019 f lm also named Maiden. She was a crewmember onboard America 3 when it successfully defended the 1992 America’s Cup, and she raced around the world a second time in the Whitbread Race as skipper of Heineken in the 1993–94 campaign. As CEO and captain of America True, Riley was the f rst woman to manage an

America’s Cup sailing team, a team that made the semi-f nal round. In 1999 Riley was named Rolex Yachtswoman of the Year for her victories on the match-racing circuit. She served as president of the Women’s Sports Foundation and has served on many governing boards, including that of the US Sailing Association. Riley’s stellar reputation, excellence as a sailor, and dual induction into the National Sailing Hall of Fame and America’s Cup Hall of Fame as the youngest and sole female “dual-famer” is an inspiration to many.

In her 2013 autobiography, Taking the Helm (written with Cynthia Goss), she makes the case that women can be equally competitive with men in of shore sailing. Her accomplishments continue to inspire countless individuals and have signi fcantly advanced women’s participation in the sport.

You’re Invited!

Please contact us to reserve your place: seating is limited. Tickets start at $400. Attire is business/cocktail.

Hotel Block : NMHS has reserved a block of rooms at the Hilton Garden Inn at 815 14th Street NW, two blocks from the National Press Club, 17–19 April, at $309 per night (plus applicable taxes). T is rate is available until 27 March or until sold out. To reserve

your place at the dinner, make a hotel reservation, or for more information, visit us online at www.seahistory.org/washington2024, or call Wendy Paggiotta at 914 737-7878, ext. 557. Special thanks to Commodore Sponsor William H. White.

Trustees of the National Maritime Historical Society invite our members to join us for a weekend of celebration, adventure, and fellowship at our 61st annual meeting in Peekskill, New York, home to NMHS headquarters in the heart of the beautiful Hudson Valley. Join us to toast our chairman emeritus, Ronald L. Oswald, as we celebrate the oficial opening of the Ronald L. Oswald Maritime Library. This is a wonderful time for our members to come together to share our achievements and ofer their ideas as the Society plots its course ahead.

Join us on the morning of Friday, 19 July, for a Hudson River cruise aboard the Evening Star. Later that day we’ll gather at NMHS headquarters to christen the Ronald L. Oswald Memorial Library. Registration for the Friday boat tour with lunch and the library reception is $80 per person.

On Saturday, 20 July, we’ll enjoy a continental breakfast at the Cortlandt Yacht Club in nearby Montrose, followed by the annual business meeting, lunch, and presentations by leaders from the local maritime heritage community. We’ll hear from award-winning artist Len Tantillo on “Colonial Dutch & New York Waterways” and Tom Johnson, co-founder of Bannerman’s Island Trust, on “Bannerman’s Island Arsenal,” Michael J. F. Sheehan, senior historian, Stony Point Battlefeld State Historic Site, on “ Te American Revolution in the Hudson Valley,” and a talk on climate changes efecting the Hudson River and Valley.

Afterwards, members will meet at West Point to embark on a two-hour History and Tradition bus tour that highlights the rich story of the forti fcation at West Point, the US Military Academy’s role in the Revolution, and its continued in fuence on American military policy. Saturday evening we’ll meet at the Overlook Lodge at Bear Mountain to enjoy a group dinner. Registration for

the Saturday annual meeting is $100 per person and includes breakfast, the business meeting, presentations, lunch, and the West Point tour. Dinner at the Overlook Lodge is $90 per person (cash bar).

Sunday, 21 July, join us as we tour the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, an hour north of the Overlook Lodge.

We encourage you to extend your visit to take in a hike or kayak, or visit Bannerman’s Island, George Washington’s Headquarters, and the Vanderbilt Mansion.

NMHS Chair CAPT James A. Noone, USN (Ret.), and Program Chair Walter R. Brown encourage all NMHS members to join us. For more information and to register, please refer to the magazine wrapper, visit us online at www.seahistory.org/annualmeeting2024, or contact Heather Purvis at administrator@seahistory.org or (914) 737-7878 (ext. 0). If you can join us as an Annual Meeting Donor, Sponsor, or Underwriter, your support goes a long way and is much appreciated.

NMHS has reserved a block of rooms at the Overlook Lodge at Bear Mountain located at 55 Hessian Drive, Highland Falls, for $259 per night plus applicable taxes. To reserve your room, call 845 786-2731 (ext. 0) and use the code “National Maritime.” T is rate is available until June 4th, or until the block is full

Te National Maritime Historical Society is excited to host the 2024 Maritime Art Gallery as part of the National Maritime Awards Dinner at the National Press Club in Washington, DC, on 18 April 2024. As a Sea History reader, you have the opportunity to purchase one of the paintings before the gala during this special preview. To view additional paintings not presented here, please visit the gallery online at www.seahistory.org/artgallery2024. And if you can join us at the dinner in Washington, DC, you’ll have the opportunity to view the art in person and meet some of the artists. Under the leadership of marine artist Patrick O’Brien, president of the American Society of Marine Artists, a select group of artists has been invited to participate. New works by Patrick O’Brien, Brad Betts, Poppy Balser, Steve Bluto, Marc Castelli, Austin Dwyer, Lisa Egeli, Neal Hughes, Leonard Mizerek, Jeanne Rosier Smith, and Stewart White will be on display— and for sale. After the event, the exhibition will continue through 31 May 2024 at the Annapolis Marine Art Gallery in Annapolis, Maryland (www.annapolismarineart.com). 25% of proceeds will beneft NMHS and is tax-deductible to the buyer—shipping is included. Purchased paintings will be displayed as “Sold” during the event. To purchase a painting, please contact Wendy Paggiotta at vicepresident@seahistory.org or call 914-737-7878, ext. 557.

Onward! by Poppy Balser • 12 x 16 inches • watercolor • $1,300

I am both an artist and a sailor. I spend a lot of time looking at water to fgure out how to paint it. One of my favorite parts of painting boats is to show how the light refects of the water and up onto sails, and then bounces back and forth between sails and decking. It is a visual treat for an artist, and I do my best to make those efects visible to all in my paintings. I was fortunate enough to fnd myself on the water as the boats racing in the Eggemoggin Reach Regatta entered Camden Harbor. It was an immense treat to be surrounded by these magni fcent boats as they cruised by with all their sails aloft. —PB

Te painting depicts a fushdeck tugboat with a tripleexpansion steam engine. She is venturing into strong winds and ferce seas to rescue a freighter of 6,000 tons nearly six times her size! Some who crew these tugboats are born courageous … others soon learn to be! —AD

x 48 inches • oil on canvas • $5,800

Te Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, Maryland, is home to a working shipyard with an intensive master-apprentice program. On the far left under the canopy is the Maryland Dove, a re-creation of a 17th-century vessel that has since been completed. Over towards the right side of the painting, the shipyard crew is rebuilding the museum’s 1912 river tug Delaware. —SW

12 x 17 inches • watercolor $1,800

In this painting (above), artist Neal Hughes is working on a painting of a wooden yacht during the Easton Plein Air Festival. He’s placed his easel against the afternoon sun and, because the vessel he is painting is behind him, he has to turn around frequently to observe his subject. Te splash of red is the collapsible wagon he uses to carry all of his gear. —SW

Before Dawn by Neal Hughes

12 x 16 inches • oil • $1,600

My emphasis for Twilight’s Edge was to create the mood and atmosphere of a typical turn-ofthe-century harbor. Te open sky gave me an opportunity to create patterns of light and shadow, which refect throughout the piece. I chose the palette and the efects of light before sunset as it strikes the sails and refects in the water to heighten the mood and atmosphere. —LM

Gretel II is a 12 metre-class racing yacht designed and built to compete in the 1970 America’s Cup in Newport, Rhode Island. She raced against the American yacht Intrepid, which ended up winning the series 4-1. —SB

Te sail training community is grieving the loss of an important leader in the death of maritime attorney Michael J. Rauworth in December. Among his many roles, Mike served as president and board chair for Tall Ships America for more than 18 years and continued on as a board member after he stepped down in 2021. His career as a mariner started in the US Coast Guard; he served as an ofcer in the Coast Guard and Coast Guard Reserves for nearly 30 years. His civilian career at sea included service on just about every type of vessel: square rig and schooners, icebreakers, cargo, military ships, passenger vessels, pilot—you name it.

Mike threw out the anchor after more than 200,000 miles at sea to become a maritime attorney focusing on Jones Act cases and those involving issues such as marine insurance, port security, marine construction and surety, and crisis management. On his LinkedIn page, he stated: “I help solve problems, mostly maritime. Sometimes in court, sometimes in better ways. And I help f nd solutions (mostly maritime), and steer around problems, which is even better. It’s quite gratifying.”

On the water and ashore, Mike was dedicated to promoting sail training and the opportunities it can ofer both trainees and crew. In that role he was dedicated to a fault. He was also very much interested in making maritime topics and law accessible and understandable to the lay person. In that spirit, he wrote articles for Sea History on the history and interpretation of the Jones Act, and, when maritime incidents made the regular news cycle, he would call and ask if I would like an article on related topics, such as the Limitation and Liability Act (after the fatal f re aboard the dive boat Conception in 2019) and the Law of General Average (in discussing MV Ever Given getting stuck and blocking passage through the Suez Canal in 2021). You can read his articles in Sea History 159, 160, 175, and 179. Mike was recognized in 2018 with the NMHS Rodney N. Houghton Award for the best feature article in Sea History in the preceding year.

I asked his long-time fellow sea captain, collaborator, and friend Captain Jonathan B. Smith for a few thoughts on Mike’s legacy, and he provided me with the following reminiscences.

—Deirdre O’Regan Editor Sea HistoryWe first met 40 years ago, in the summer of ’83. He was chief mate in the four-masted barque Sea Cloud; I was skipper of the schooner yacht Marie Pierre. We were anchored together of Rhodes, in Greece. It happened to be my birthday, so the mood was festive. I finagled an invite over to Sea Cloud’s sundowner, over which Mike was presiding. He was a welcoming and gracious host. We enjoyed a few tots and sea stories together and then went our separate ways. How strange it was, then, that two years later we found ourselves co-captaining the newly built schooner Spirit of Massachuset s in Boston! So began a long-time friendship.

I have been thinking about what will stand out and remain whenever I think of him—beyond his expertise and experience in numerous realms. What are the descriptive words I’m looking for? “Af able, generous, forthright, welcoming (again), modest, dedicated, open, professional, likable…” all of these rolled into one, and more. It could be argued that Tall Ships America might well not exist today without Mike’s hand on the helm and checkbook at the ready. Through his seagoing background, knowledge of maritime law, and tireless eforts, he steered the organization through varied troubled seas for many years to the present. His influence has positively afected many.

I’ll always remember him as emblematic of the best qualities of a shipmate—dependable, kind, selfless, able—and expressive of a certain joy and humor. His unique smile lingers on as will his tireless eforts on behalf of those who go down to the sea in ships. Farewell, Mike.

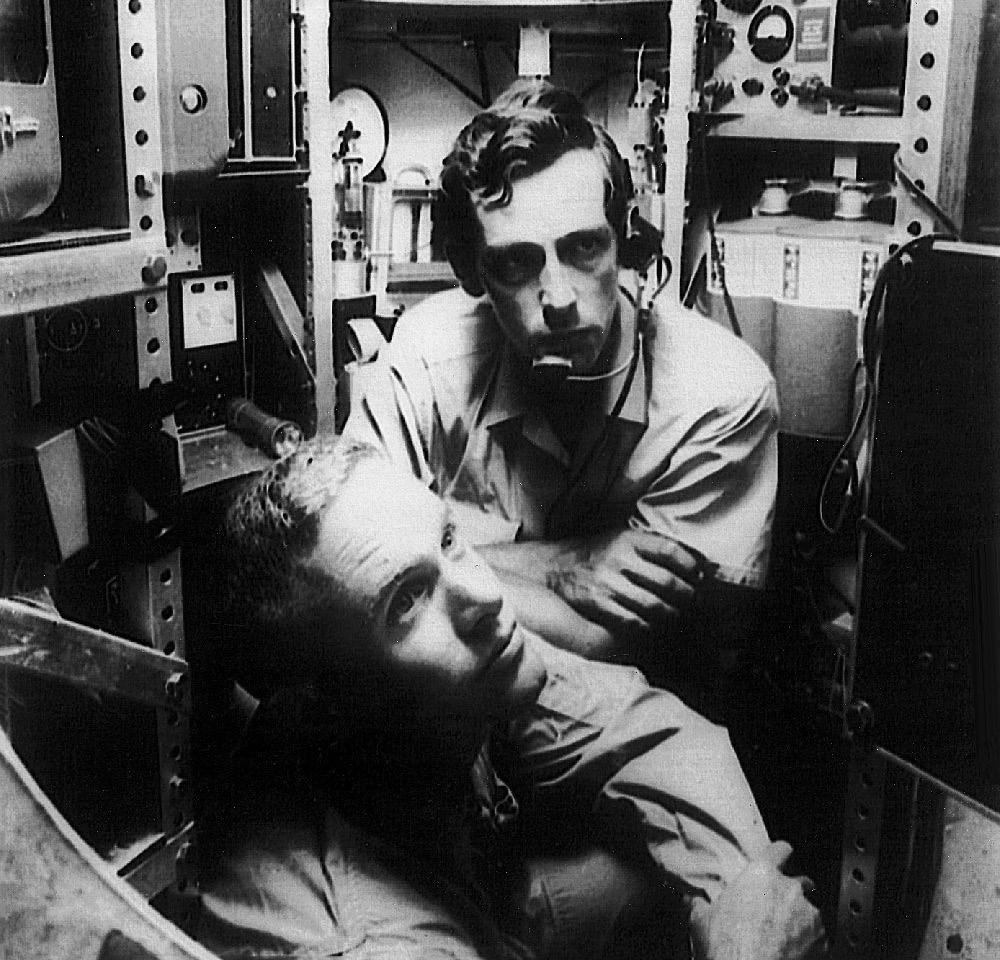

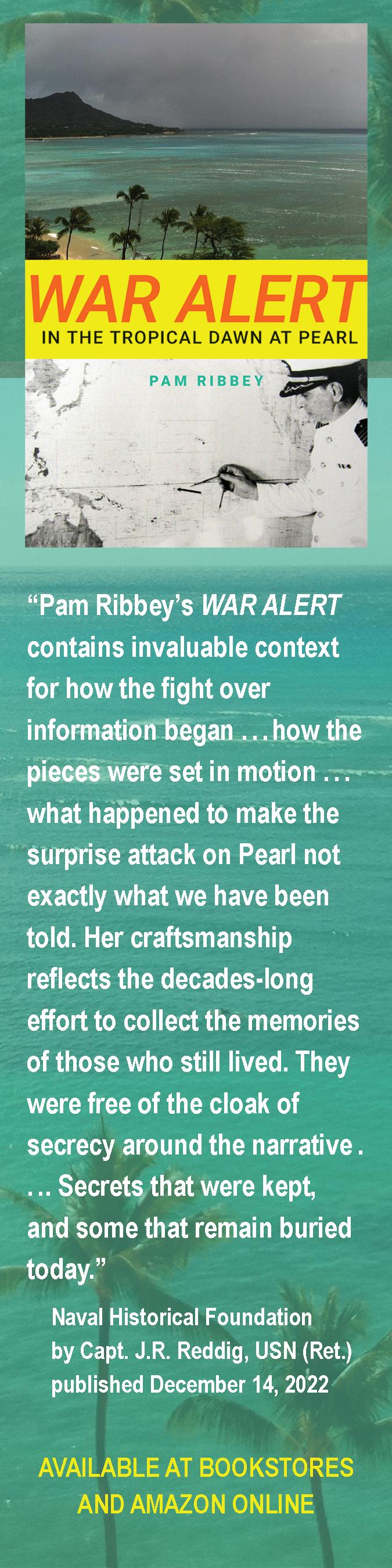

—Captain JB Smith“A decade of exploration capped in July 1969 by Neil Armstrong and Edwin E. ‘Buzz’ Aldrin stepping onto the moon began with the equally daring accomplishment of Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard in January 1960 descending to the botom of the Marianas Trench.”

Lieutenant Don Walsh made history in January 1960 when he and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard piloted the bathyscaphe Trieste to the deepest place on earth—Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench. Teir groundbreaking descent stood unmatched for 52 years. Born in Berkeley, California, Don Walsh joined the US Navy in 1948 and served as an air crewman in torpedo bombers until he entered the US Naval Academy in 1950. After graduation, he served two years in the Amphibious Forces, followed by service in submarines and then aboard the Trieste from 1959–62. His 24-year naval career included service in both the Korean and Vietnam wars. During this period, Captain Walsh pursued a PhD in oceanography from Texas A&M University, focusing on remote sensing, and in 1969 he earned a masters in political science from San Diego State University, where he studied law-of-the-sea issues.

In 1975 Captain Walsh retired from the US Navy and in 1976 he founded the consulting company International Maritime Inc. He participated in more than 50 polar expeditions and piloted dives to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge near the Azores, the RMS Titanic wreck site, and the WWII German battleship Bismarck. Active in the design, manufacture, and operation of manned and unmanned submersibles, Captain Walsh also served as technical advisor for f lmmaker James Cameron’s deep-sea explorations.

—Dr. David F. Winkler, Naval Historian

(l–r) Lieutenant Don Walsh, USN, and Jacques Piccard in the bathyscaphe Trieste, 1960.

Captain Walsh was elected to the National Academy of Engineering. He was the recipient of numerous awards: the Explorers Club’s Lowell Tomas Medal and Explorers Medal, the Jules Verne Adventures organization’s Étoile Polaire medal, and the National Geographic Society’s Hubbard Medal. In 2001 he was also selected as one of the world’s greatest explorers in Life magazine’s Te Greatest Adventures of All Time.

In recognition of this remarkable record of research, achievement, and service, in 2012 the National Maritime Historical Society awarded Don Walsh our Distinguished Service Award. He was an engaging, approachable, and personable recipient. He was enthusiastic about sharing his life’s work and honored to be recognized.

Don Walsh continued to play a key role in underwater discoveries. T rough his international consulting practice, he focused on ocean-related projects throughout the world. In 2020 his son Kelly Walsh completed a dive to the Challenger Deep, repeating the feat his father had achieved 60 years before.

Fair winds, Don Walsh, from your friends at NMHS and from an appreciative global community.

—Burchenal Green, NMHS President Emeritus

We are mourning the recent death of Pam Rorke Levy, an enthusiastic and generous supporter of the Society who, with her husband Matt Brooks, received the 2019 NMHS Distinguished Service Award for their restoration of the historic yacht Dorade, regarded as one of the greatest yachts ever produced by Sparkman & Stephens. A vibrant and accomplished woman in many arenas, Pam was an Emmywinning television producer and creative director, creating a wide range of f lms and TV programs on subjects at the intersection of art, culture, and history for PBS, National Geographic, the Discovery Channel, A&E, and the History Channel.

She was a supporter of the St. Francis Sailing Foundation, which supports young sailors at all levels of the sport. “It was important to both of us to make a positive social impact, and important to encourage youth to come into the sport,” said Matt.

Purchasing Dorade in 2010, the couple restored the historic yacht to racing condition. Pam shared her thoughts on her f rst experience underway aboard their new yacht.

The moment we walked onboard Dorade we fell in love, not knowing what we were geting into. Afer a first sail aboard Dorade, we realized this was not a boat we were going to be sailing around San

Francisco Bay by ourselves; it was a race car— designed to go in a straight line for a very long way.

Of her many wonderful qualities, it is her courage that stays with me. I remember a quote she gave us some years ago that epitomizes the thoughtful, generous, interesting person we have lost.

Absolutely, Olin Stephens is my role model. We were extraordinarily lucky to fall in love with his very first boat—the only boat he ever owned. He lived to be 100 years old and designed eight America’s Cup winners. Dorade meant a tremendous amount to him and it launched his career. There isn’t a time when I am on the boat when I don’t think about Olin being onboard. He was able to commit himself to excellence and discipline in every way, and he did it with an extraordinary sense of humility and gratefulness. No mater how many races we win, I want to have that kind of humility—that there is something more to learn and be generous in sharing the credit and the experience with as many other people as we can.

Fair winds, Pam. You will be long remembered and missed. From all of us at the National Maritime Historical Society. —Burchenal Green, NMHS President Emeritus

A Replica of Long Island’s First Motorized Oyster Dredge Launched in Oyster Bay Afer 12 Years

PHOTO

by Bill Bleyer

PHOTO

by Bill Bleyer

Building a replica of the historic Oyster Bay shell fsh dredge Ida May took a dozen years, about $1 million, 35,000 hours of mostly unpaid labor by 70 volunteers and a few professionals, plus a lot of perseverance in the face of fundraising di fculties and COVID-19 complications. While the project took a full decade longer to complete than anticipated, the vessel is on track to carry paying passengers on Oyster Bay and Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island’s north shore.

Last spring, Ida May was launched by trailer into Oyster Bay after the boat was completed in a shed on the southern edge of the harbor by the Christeen Oyster Sloop Preservation Corp., the organization that had previously restored the 1883 sailing oyster dredge Christeen.

Te volunteer group, called the Ida May Project (IMP), has since turned over Ida May to another nonproft, the WaterFront Center, which runs marine educational programs onboard boats, in the classroom, and along the

waterfront. Te center also operates the Christeen for harbor tours.

Te IMP started out with plans to restore the original Ida May, which was launched in 1925 by Frank M. Flower & Sons. “It was built by Frank M. Flower on the beach in Bayville,” said George Lindsay Jr., president of the volunteer group. “ Te story [goes that] he did it after he thought he had lost his three sons on a smaller boat when they were making a routine trip to the Fulton Fish Market in Manhattan. Tey almost sank the boat and had to put into City Island. For four days Frank Flower didn’t know where his sons were. So, he decided to build a bigger boat. It was the f rst oyster dredge built to be motorized, as far as we know.”

Te 1925 Ida May would dredge for oysters and clams and then transport them to the city f sh market, usually with a crew of two or three. Te boat was designed with a broad beam and shallow draft. “A lot of the oystering is done in fairly shallow water,” Lindsay

explained. “It was [built] wide to make a stable platform. Virtually the entire hull was a hold for clams. Everything forward of the pilot house was just cargo. Tere were a couple of berths on either side of the diesel engine so two or three people could spend the night there, but it wasn’t designed for cruising.”

Te boat was engaged in oyster dredging for 75 years. Te Flower company retired her and brought her ashore in September 2003. But the dredge, as designed, would not have been able to carry paying passengers under current Coast Guard regulations. Having deteriorated beyond repair while the restoration efort was being organized, it was demolished in 2010.

Instead, they adjusted the goal and made plans to build a replica. Starting in November 2011, volunteers worked part-time with a professional shipwright as money became available. Te original Ida May was 45 feet long and 15½ feet on the beam, constructed with bent oak frames and cedar planking. Te

replica is a foot wider, to meet Coast Guard requirements for carrying paying passengers. Construction got underway with a $125,000 contribution from singer-songwriter Billy Joel, who owns a harborside home on Centre Island on Oyster Bay, and who worked on a dredge owned by Flower & Sons as a teenager growing up on Long Island Sound.

Te new iteration of Ida May is framed with two layers of three-inch white oak, some of it left over from the Christeen project, and the rest was obtained in Virginia. Her planks are 1¾inch white oak, the pilothouse frame is white oak, and the exterior is red cedar. Te interior is black walnut paneling with cherry trim. Te original 45-foot Ida May was constructed with bent oak frames and cedar planking.

Several weeks after the f nal hull plank was installed, the widow of Clint Smith, a former town harbormaster who organized the Christeen group, smashed a bottle of champagne against the bow and Ida May slipped into the harbor. It was a breezy May morning with the Christeen and bay constable boats standing watch. In celebration, a f re truck sprayed water into the air—and accidentally on town ofcials and other people watching from the dock(!).

“It’s very exciting because, for me, it’s been a seven-year commitment,” Lindsay said. “It’s been a tremendous learning experience. And it’s been really fun. But the goal was always to get the boat f nished and launched, and here we are.” After the launch, the punch list included getting the engine and some other equipment running, Lindsay said.

Te f nal steps—sea trials and Coast Guard certi fcation for carrying up to 44 passengers—are currently underway. “ Te plan initially is to introduce her to the community to get people familiar with the vessel,” said George Ellis, executive director of the

WaterFront Center. “We also expect her to be an active participant in the current resurgence of oyster farming. We’ll do educational cruises and perhaps get involved in research. We hope to partner up with some of the universities and other groups engaged in oyster farming.”

“She’s very maneuverable,” Lindsay said. “Her steering worked out very well. She cruises very comfortably at about 6½ knots, and we got her up to about 9 knots.”

With the recent sale of the Flower company’s remaining wooden dredge, Ida May is now the only wooden oyster boat in Oyster Bay, and, as such, she is preserving the history of commercial shell f shing in Oyster Bay, both by actually doing the work itself, and by representing what was once a thriving industry in the region so that this generation and generations to come are aware of their local history.

(www.thewaterfrontcenter.org)

Bill Bleyer, a retired award-winning reporter for Newsday, is the author of six books on Long Island history. During his 33-year career writing for Newsday, he also wrote the “On the Water” Sunday column for five years. He contributed a chapter to Harbor Voices—New York Harbor Tugs, Ferries, People, Places & More (published by Sea History Press, 2008). Bleyer continues to write articles as a freelancer and is a frequent speaker at venues across the Northeast.

Mutiny. Not a word a sea captain ever wants to hear aboard their ship—naval or merchant, large or small. A mutiny could, and often did, prove fatal to some of the ship’s company—the captain and perhaps ofcers if a mutiny was successful, the mutineers if it did not.

I doubt there is anyone who has not heard someone referred to as a “real Captain Bligh.” William Bligh was the commanding ofcer of the Royal Navy Armed Vessel Bounty and in 1787 was sent to Tahiti to gather breadfruit trees for transplanting to the British Caribbean. Breadfruit was cheap and easy to grow in a tropical environment, and it was thought the sugarcane plantation owners could use it as a staple to feed their slaves. Bligh was sailing short-handed, with no other ofcers aboard—just three master’s mates, one of whom, Fletcher Christian, was given a brevet promotion to midshipman so he could act as f rst lieutenant (2nd in command). Te long trip from England to Polynesia was arduous, to say the least, (30 winter days spent trying to claw around Cape Horn before giving up and taking the longer route east around the Cape of Good Hope) and the crew was inexperienced and diffcult. T at said, Bligh had only one man lashed during the entire trip. So… cruel? Not so much!

Once they arrived in Tahiti, they had to wait months for the breadfruit trees to be mature enough to dig up and transplant to pots for the ride to the Caribbean. In the meantime, the men became enamored with the somewhat promiscuous local ladies; some even

by William H. White

married them. When it was time to leave, most preferred to remain but went out with the ship like good British sailors. Tat’s when the trouble began. Te men missed their girlfriends and wives, and Fletcher Christian, using partly imagined and partly valid complaints about Bligh, led the men in a revolt, putting the captain with eighteen of his supporters overboard in the longboat, while Christian and his cohorts sailed the Bounty back to Tahiti. Mutiny!

In a stunning feat of navigation and seamanship, Bligh successfully sailed the overloaded longboat 1,500 miles to Indonesia with the loss of only one man—a truly remarkable feat in an open boat. In the meantime, Christian, realizing that staying in Tahiti would almost guarantee their capture when the Royal Navy returned, took the ship, nine British sailors, fve Tahitians to help sail her, and twelve Ta-

hitian women to a mis- charted and uninhabited island called Pitcairn. Sixteen mutineers preferred to remain in Tahiti and, proving Christian’s surmise correct, were ultimately captured or killed when HMS Pandora arrived to bring them to justice. Books have been written (including one by your humble scribe) about this mutiny and the aftermath. It’s too long a story for this article, but (spoiler alert) ultimately a few of the mutineers were caught, returned to England, tried and hanged. Christian was convicted, but in absentia . Bligh’s reputation was smeared forever, quite unfairly. He was not cruel—perhaps guilty of being a poor administrator, but ultimately he was held blameless by a Royal Navy court-martial.

Bligh went on to command other ships, one of which was involved in another pair of notorious mutinies when much of the enlisted cadre of the Royal

Navy rebelled while in harbor in Britain. Te so-called Spithead and Nore Mutinies involved little more than a modern-day strike. Even so, they roiled the British Fleet in 1797. Te Spithead Mutiny lasted about a month and involved sixteen ships in the Channel Fleet, of concern given the ongoing war with France. Te issues involved living conditions, pay, victualling, and compensation for illness or injury. While the sailors remained relatively peaceful, and, indeed, promised to go to sea if the French were spotted near the coast, negotiations became stalled and several small incidents occurred. Admiral Lord Howe intervened and brought a peaceful solution to the issue.

Te coincidental mutiny in the T ames Estuary, the Nore Mutiny, was a di ferent story. Tere, the crew of HMS Sandwich took control of the ship and were copied by several other vessels in the anchorage. Due to the feet being spread out across the anchorage, little consistency or union was possible. Each ship elected a representative to try to coordinate the efort. One man, Richard Parker, was elected “President of the Delegates,” apparently without his knowledge. Te demands were ridiculous, including the dissolution of Parliament, immediate peace with France, and a pardon of all participants. Violence bubbled up, killing many, and a blockade of London followed. Some 50 ships of the Royal Navy, with loyal crews, ultimately put down the mutiny. Parker was hanged along with 29 others, another 29 were imprisoned, nine were fogged, and some others were sent to Australia.

Tere were other mutinies in other nations (Russia had a famous one in the early 20th century, the so-called Kronstadt Mutiny), but until the mid-19th

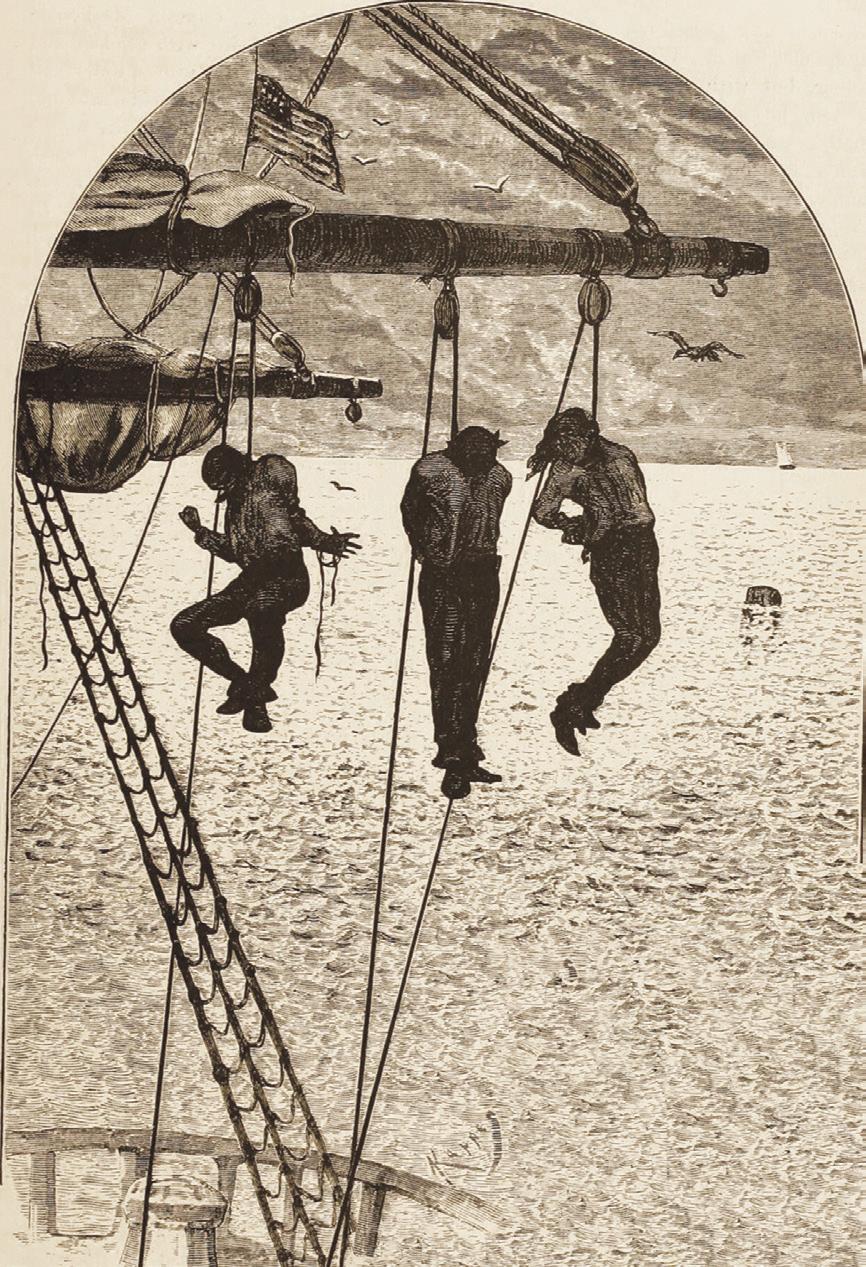

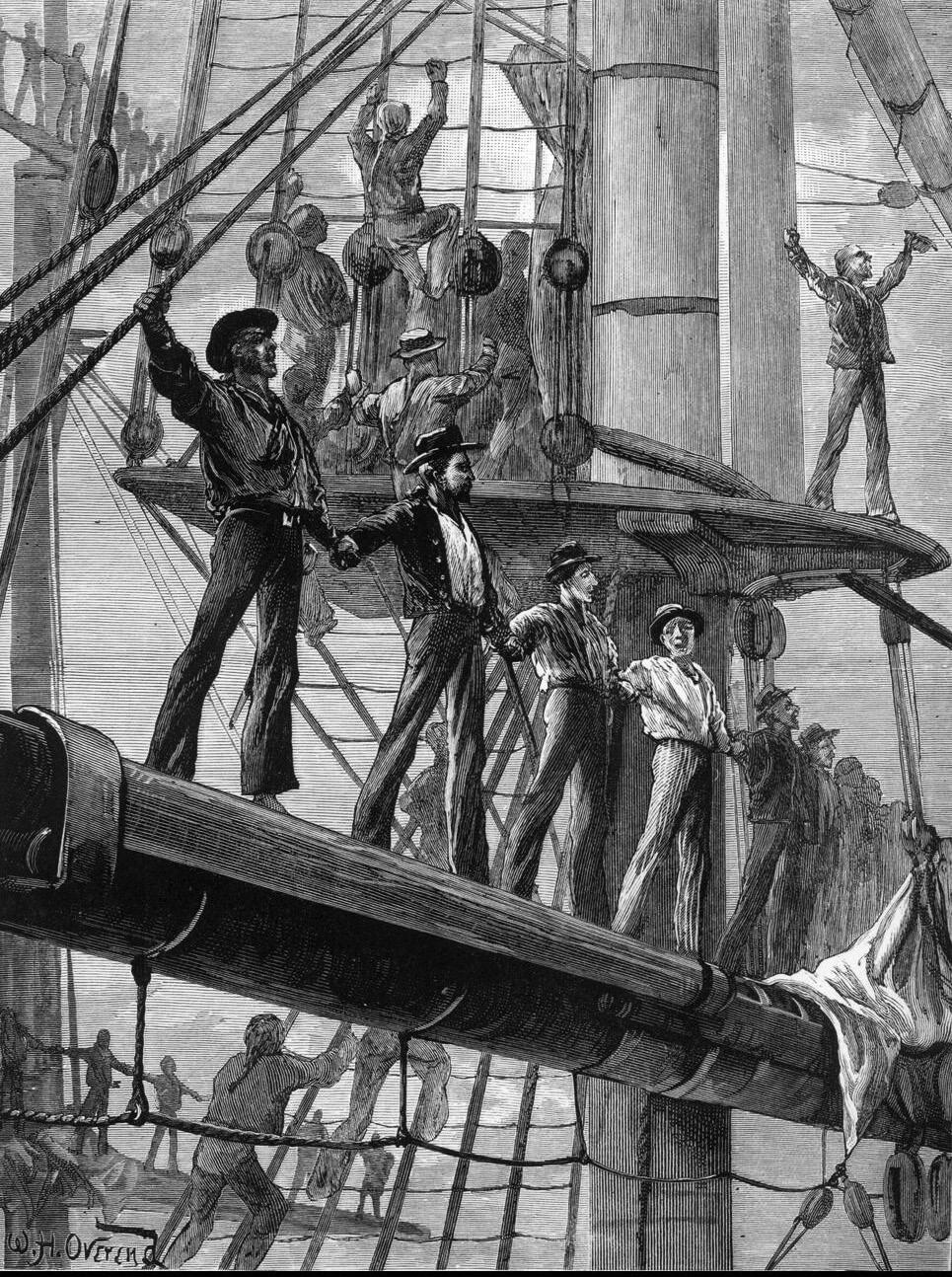

Spithead, 1797. Mutineers man the yards to voice their demands to the Admiralty. Steel engraving by W. H. Overend, 1890.

century, the American navy had experienced none. Enter US Brig Somers.

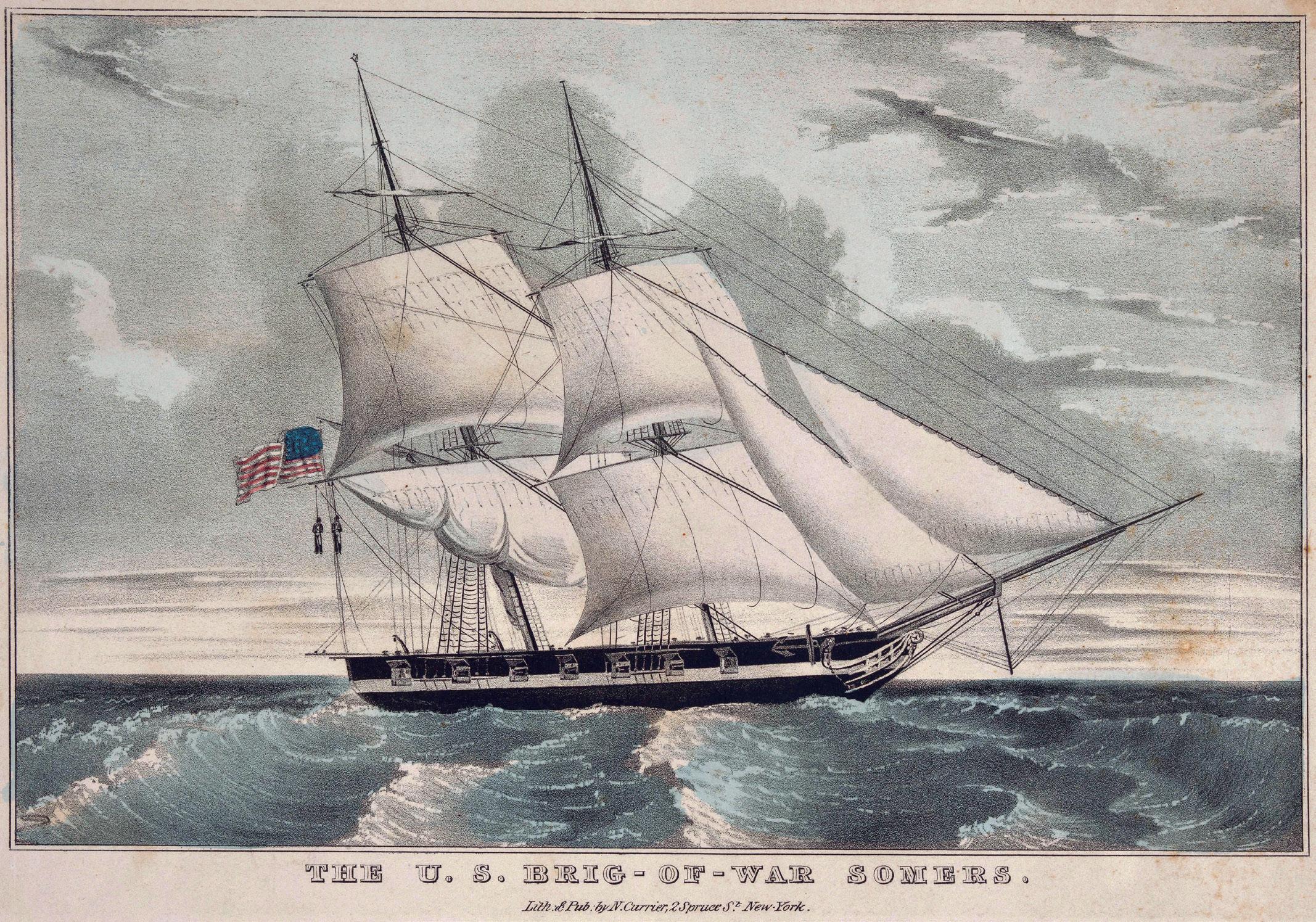

Somers, a new ship designated as a training vessel and captained by Alexander Slidell MacKenzie, had been sent to sea by Commodore Matthew Perry in September 1842, following a summer shakedown cruise from New York. MacKenzie was tasked with carrying dispatches to another ship, Vandalia , then on anti-slave patrol of the coast of Africa. MacKenzie missed Vandalia at multiple ports on the Atlantic coast and ultimately arrived in Monrovia, Liberia. Tere he learned he had missed

her again and quickly left to recross the Atlantic, hoping to catch up with her at St. Tomas in the Virgin Islands.

Te brig’s crew consisted of the usual gang of sailors, mostly young inexperienced “landsmen,” plus four midshipmen and one ofcer, Lt. Guert Gansevoort. Before we get too far into the story, let us look at how a young man might become a midshipman and then achieve a lieutenant’s commission in the United States Navy.

Tere was, of course, no Naval Academy at the time and, should a lad of 14–16 years of age wish to join the

Navy as other than a fo’c’sle hand, he had to be sponsored by someone with political clout to obtain an appointment from the Secretary of the Navy as a midshipman. After serving three or four years in that role, he had, presumably, learned the skills necessary to ascend to lieutenant. He would then be examined and tested by senior offcers and, if found competent, would be promoted to lieutenant. Fail twice and he would be passed over, precluded from attaining ofcer rank.

Should a lad have no sponsor and still wish to become an ofcer, he could sail in the merchant feet for several years (at least three) to gain the seamanship skills necessary, post for master’s mate (still in the merchant feet), and then seek a midshipman’s berth in the Navy. A lengthy and arduous path, indeed.

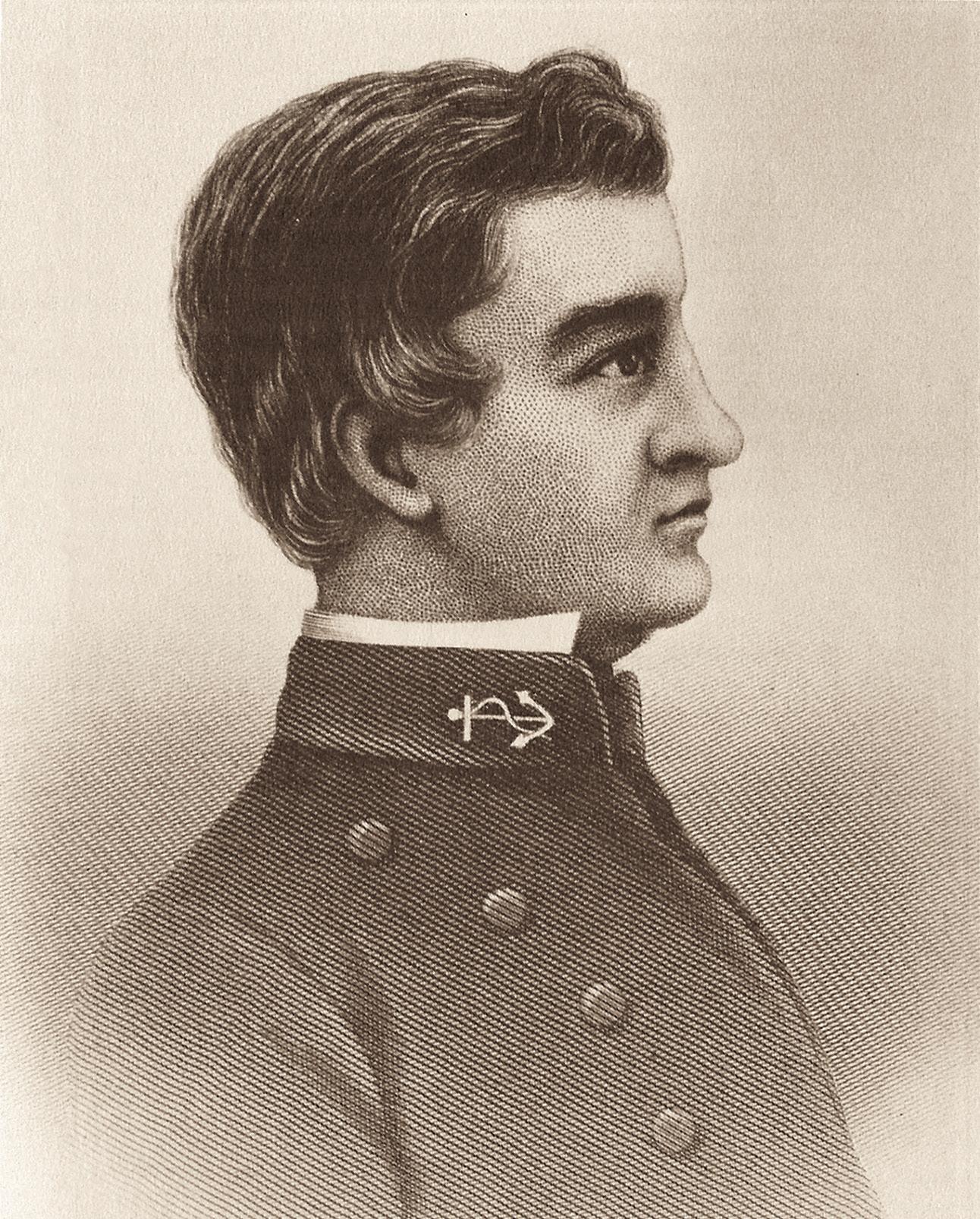

Now, back to the Somers mutiny. By the time the brig had returned to the Caribbean, Captain MacKenzie saw that his crew’s morale was dismal. Te men were sullen, unresponsive to orders, and generally slack in their duties. He heard a whisper from Lieutenant Gansevoort, his f rst lieutenant, that there might be trouble brewing, possibly instigated by one of the midshipmen—Philip Spencer, who was, interestingly, son of the Secretary of War John C. Spencer.

Young Midshipman Spencer had, to say the least, a checkered past. He had been invited to leave two di ferent colleges (Geneva and Union) due to his wild and uncontrolled behavior and then signed aboard a Nantucket whaler. He subsequently was told by his father that if a life at sea was his choice, then it should be as a “gentleman” (a com-

missioned ofcer). Using his political in fuence, the elder Spencer obtained a midshipman warrant for his son.

Young Spencer was as fractious a sailor as he had been a student. He remained undisciplined and impossible to control, assaulting f rst a senior offcer aboard the North Carolina and then a British ofcer while on a port visit in Rio de Janeiro. To avoid a courtmartial, he resigned his commission but, due to his father’s position, his resignation was not accepted. Te Navy then assigned him to the training ship Somers, thinking the training might be a help in turning the young man into a productive member of the naval ofcer corps.

A charismatic young man, Spencer curried favor with many of the crew by, among other things, providing them with tobacco and liquor. In August

1842, he told the purser’s steward, J. W. Wales, of his plan to lead about twenty of the men to take over Somers, and then sail as a pirate in the Caribbean. It should be noted that piracy in the Caribbean, for all intents and purposes, had been extinguished since about 1830. A shipmate, seaman Elisha Smalls, was also involved in the planning. Te following day, Wales told his boss, Purser Heiskill, and the f rst lieutenant, Guert Gansevoort, about the plan. In turn, Gansevoort tipped of Captain MacKenzie.

MacKenzie took the information with a grain of salt but told his f rst lieutenant to keep an eye on the

men and listen for any rumblings. Mr. Gansevoort learned that Spencer held nightly meetings with his loyalists, including Smalls and Bosun’s Mate Samuel Cromwell, both of whom had sailed in slave ships before joining the navy. Cromwell was a known troublemaker with a deep hostility towards his superiors. Gansevoort also noticed that Spencer seemed to spend a lot of time studying charts of the West Indies and sketching ships with the black fag used by pirates. Crewmen loyal to the captain also reported Spencer seeking information about the Isle of Palms, reputed to be a pirate hangout. Over the course of a few months, it became

apparent that Spencer and the other midshipmen, along with some of the seamen, were going to cause trouble.

Captain MacKenzie confronted Spencer, mentioning the information from the purser’s steward as well as Gansevoort’s observations. Te midshipman responded that he told Wales the pirate story as a joke, but MacKenzie was unmoved. He had Spencer arrested and placed in irons—hands and feet—and kept on the quarterdeck, while his cabin and belongings were searched. Discovered in the search were two documents, written in Greek (later referred to as the “Greek Papers”), which another midshipman translated. Tey ofered absolute proof that Spencer was fomenting a mutiny. His intent, clearly spelled out in the Greek Papers, showed that the rest of the crew would join—or be forced to join—and those who refused would be “disposed of.”

Te tenor of the ship immediately changed. Te crew’s loyalty was divided; the smallest deviation from normal caused concern to the two ofcers, and everyone was suspect. An accident aloft that damaged the rig seemed suspicious. When questioned about it, Cromwell,

known to be one of Spencer’s confederates, blamed Smalls, who immediately confessed. Both joined Spencer in irons on deck. Te same evening, as a new t’gallant mast was being hoisted into place, several crewmembers rushed the quarterdeck but were stopped when Lieutenant Gansevoort pulled his pistol and pointed it at the sailmaker, Charles Wilson. Further incidents occurred among the men, from an attempted theft of liquor for the prisoners to an attempt to gain access to the arms locker, while still others refused to stand their watches. Tey were summarily fogged.

MacKenzie realized his ship was in danger and arrested four more men, bringing to seven the total in irons. In his growing concern, he acknowledged he did not have the resources to secure

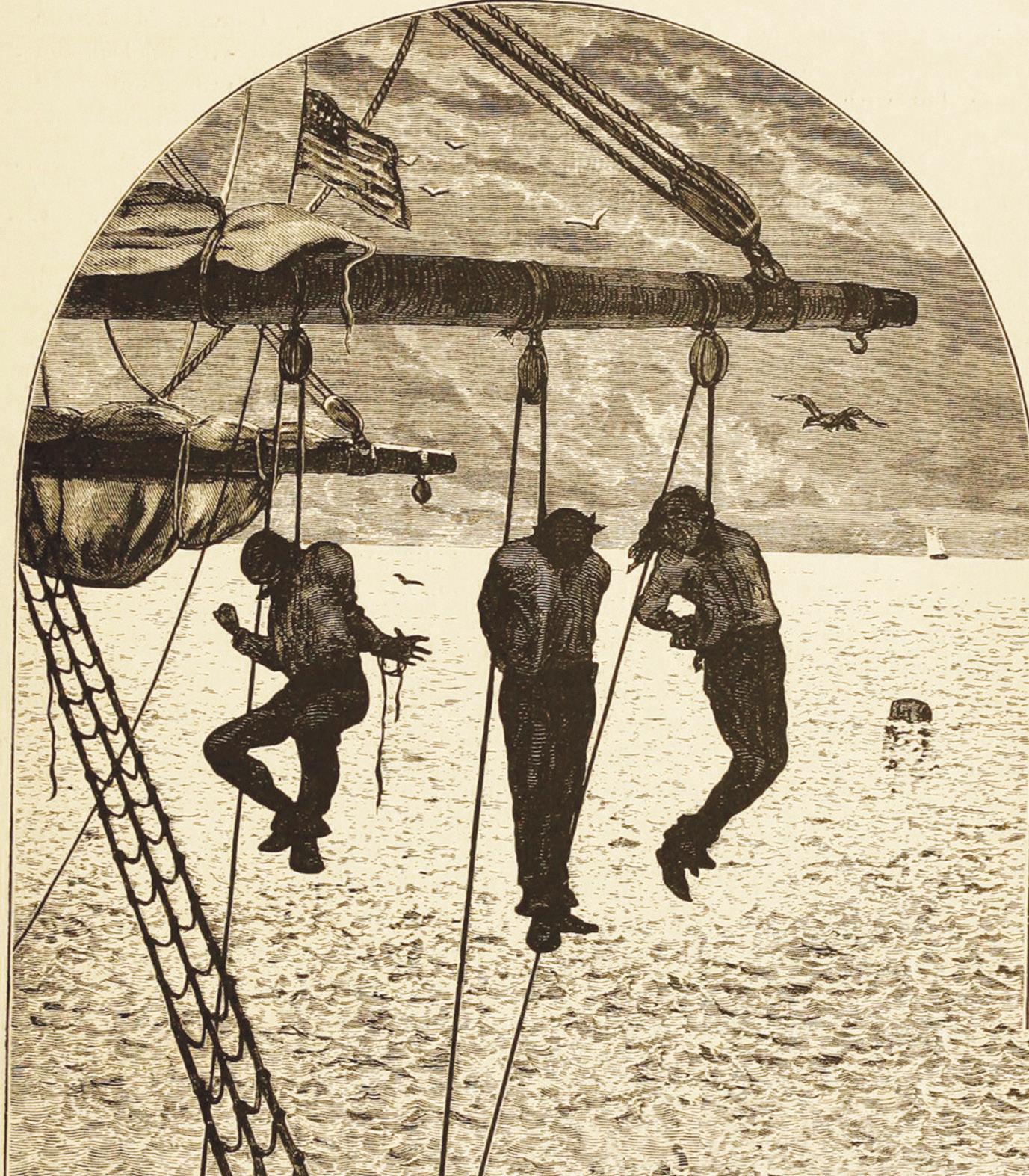

the prisoners he already had in irons, let alone more. He wrote a letter to his senior sta f —the surgeon, purser, sailing master, and three remaining midshipmen (loyal to him)—requesting their opinions and a resolution to the situation. Further crew interviews resulted and, in a matter of days, a unanimous decision was reached that Spencer, Smalls, and Cromwell were indeed guilty of “intent to commit mutiny on a United States Naval vessel.” Tey suspected more were in league but recommended that the three be hanged to make an impression on any who might be sympathetic to their cause. Mackenzie took the recommended action that same afternoon: 1 December 1842. Without a court martial or trial of any kind.

Te bodies were buried at sea and Somers sailed for St. Tomas and then New York City, reaching there on 15 December 1842.

Of course, the news spread quickly and a court of inquiry was convened to investigate the mutiny and MacKenzie’s solution. (MacKenzie had requested a court martial to clear his name.) He was charged with oppression, illegal punishment, and the “catch-all”—conduct unbecoming a naval ofcer. Te captain defended himself and witnesses supported his claim of justi fcation under the circumstances. Te court declared him innocent of all charges and cleared his name, deliberating from late January to the end of March. Public opinion, fueled by novelist James Fenimore Cooper’s writings on the subject, remained f rmly against MacKenzie, but seemed to have little impact on his career. MacKenzie died ashore of heart disease in 1848. He left a mark on the literary world with several published books including: A Year in Spain, by a Young American (1829), Popular Essays on Naval Subjects (1833), Te American in England (1835), Spain Revisited (1836), Life of John Paul Jones (1841), Life of Commodore Oliver H. Perry (1841), and Life of Commodore Stephen Decatur (1846).

As an aftermath of the mutiny and court-martial, it was readily apparent that proper midshipman’s education was an important need and using a naval ship—in this case, US Brig Somers as a school ship was not a viable way forward without proper classroom instruction.

Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft found appropriations to establish a naval school at a ten-acre Army post named Fort Severn in Annapolis, Maryland. On 10 October 1845, with a class of 50 midshipmen and seven professors,

Ringleaders Hanging From the Yardarm by Alfred Kappes (1850–1894)

the Naval School became a reality. Te curriculum included mathematics and navigation, gunnery, steam, chemistry, English, natural philosophy, and French. Captain Franklin Buchanan was its f rst superintendent.

In 1850 the Naval School ofcially became the United States Naval Academy. A new curriculum went into efect requiring midshipmen to study at the Academy for four years and to train aboard ships each summer. Tat format is the basis of a far more advanced and sophisticated curriculum at the Naval Academy today.

As the US Navy grew over the years, likewise the Academy expanded. Te campus of ten acres increased to 338. Te original student body of 50 midshipmen grew to a brigade size of 4,000. Modern granite buildings replaced the old wooden structures of Fort

Severn. One of the main buildings at the Academy is named Bancroft Hall, in honor of the founder of the school.

A further result of the Somers situation was the abolition of fogging in the US Navy, efective 1850. Interestingly, Herman Melville used the mutiny and resulting executions as fodder for his novel Billy Budd , having gained most of the original details from his f rst cousin, Guert Gansevoort, f rst lieutenant in Somers

Te US Brig Somers, under di ferent commanders, continued in service, experiencing several tragic events in the Mexican War. In 1846, under the command of Raphael Semmes, she was lost in a storm of Mexico with about half the crew. Semmes would go on to become a Confederate naval ofcer, captaining the most successful Confederate raider, CSS Alabama .

William H. White is a former United States Navy oficer with combat service. He is also an avid, life-long sailor. As a maritime historian, he specializes in Age of Sail events in which the United States was a key player and lectures frequently on the impact of these events on our history. White has eight historical novels and one nonfiction history to his credit, each set in the early 19th century and centered on the young American Navy. He has also writen two books centered on the Royal Navy in the late 18th century, one dealing with the capture of the Bounty mutineers and one focusing on a major shipwreck on Grand Cayman, where he used to live prior to moving to Florida. More information can be found on his website, www.seafiction.net. Mr. White is a trustee of the National Maritime Historical Society.

Today’s US Naval Academy spans 338 acres and is home to 4,000 cadets who are pursuing bachelor of science degrees and commissions as ensigns in the Navy or second lieutenants in the Marine Corps.

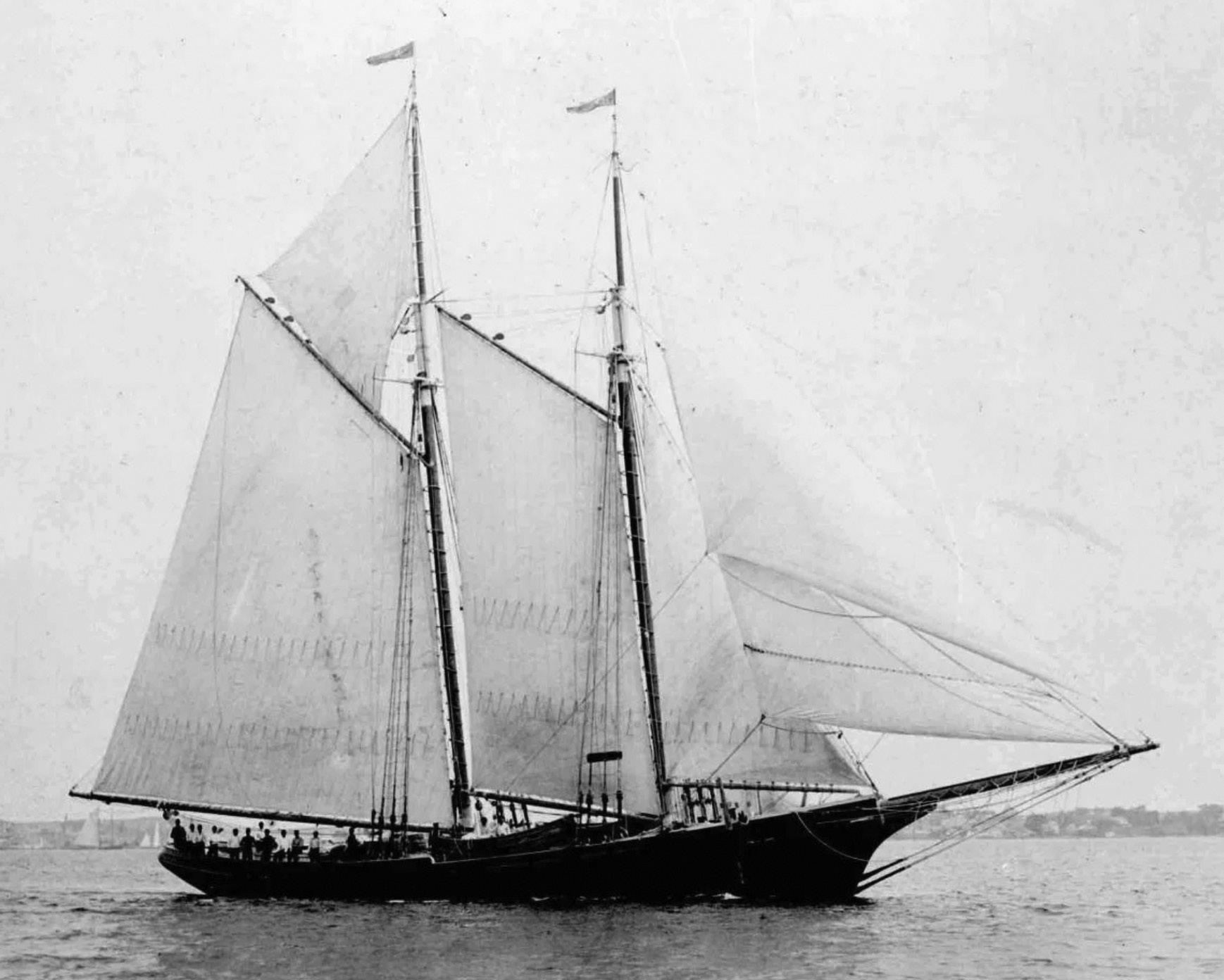

With a cheery welcome, I was waved aboard the Ernestina-Morrissey, moored at her berth in New Bedford, Massachusetts. I had been looking forward to visiting her for over a decade, since my research began into the extraordinary life of American explorer Louise Arner Boyd, who sailed in this ship during her 1941 Arctic expedition. Te schooner has only recently opened to the public following the completion of a seven-year multimillion-dollar restoration project at the Boothbay Harbor/Bristol Marine Shipyard in Maine. As I stepped on the deck, I was greeted by Captain Ti f any Krihwan and, by chance, Sea History editor Deirdre O’Regan, who were keen to show me around.

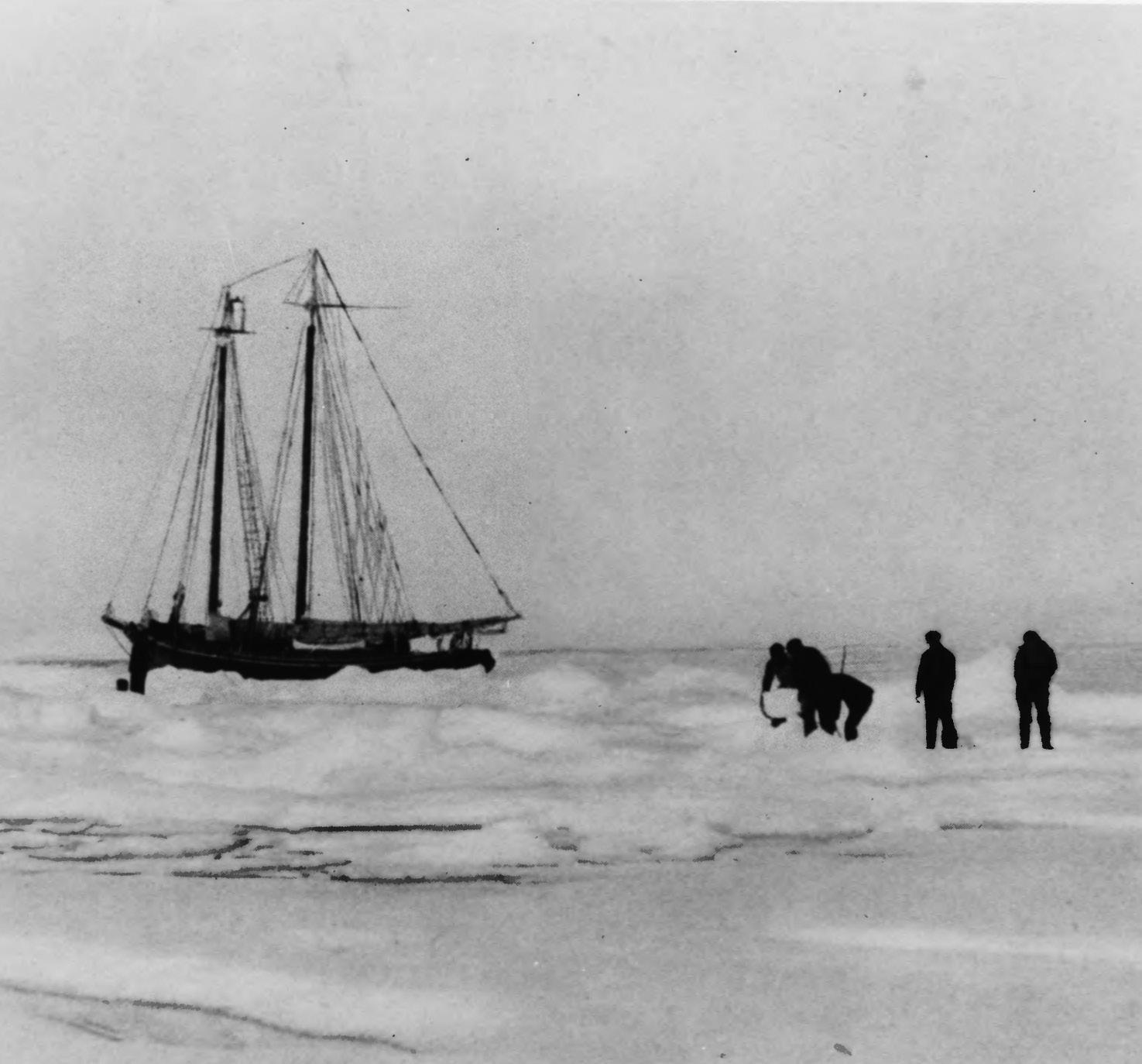

Built in just four months at the John F. James and Washington Tarr Shipyard in Essex, Massachusetts, and launched on 1 February 1894, the schooner was originally christened Efe

by Joanna KafarowskiM. Morrissey. She saw service as a Grand Banks f shing vessel out of Massachusetts, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland before Arctic explorer Captain Bob Bartlett purchased her in 1925. It was the beginning of a lifelong love a f air.

No more graceful, trim, staunch nor able craft than the Efe M. Morrissey was ever launched from this famous shipyard and the men who built her knew it. In that day shipwrights built sailing vessels with a real pride in their work and with more than a touch of genius. She was just a good, honest, beautiful craft.…I loved that schooner the f rst minute I clapped eyes on her and the feeling has grown ever since.

Captain Bartlett was by then already a renowned Arctic explorer who had skippered the vessels that took

Robert Peary to the Arctic, including the expedition when Peary reputedly conquered the North Pole in 1909. A few years after that, Bartlett’s legendary status grew when, in 1914, he almost singlehandedly saved the crew of the ill-fated Karluk during Vilhjalmur Stefansson’s Canadian Arctic Expedition. Between 1926 until the start of the Second World War, he sailed to the Arctic fourteen times.

Captain Tifany Krihwan has commanded the Ernestina-Morrissey for nearly three years and is the ship’s third female captain. Currently, only twelve percent of captains in the American tall ship feet are women. She is well acquainted with the vessel’s illustrious history: “I have a strong sense of connection to the people associated with the vessel and feel the spirit of the previous captains.” Due to the scale of the renovation project, not a lot of the ship’s original fabric from Bartlett’s era has survived, but the helm, windlass, stem, and the bowsprit from that era are still there. Te billet head, freshwater tank, and a few dozen other items from the original ship are stored in a nearby warehouse. As I walked the deck and went below, it was easy to imagine life on an Arctic voyage with Captain Bartlett bellowing orders during a gale.

After participating in the 1928 international rescue mission to locate South Pole conqueror Roald Amundsen as well as leading four of her own daring expeditions to East Greenland in the 1930s, Louise Arner Boyd was about to undertake one f nal Arctic mission. She was the best-known female explorer of her time and, as a result of her scienti fc contributions, had received accolades and awards from around the

Efie M. Morrissey, 1930, Ford–Bartlet East Greenland Expedition.

world. Asked by J. H. Dellinger of the National Bureau of Standards to undertake a secret mission on behalf of the American government, Boyd never hesitated.

During the Second World War, Greenland held a position of strategic importance. According to a publicity statement, the expedition planned to carry out radio and geomagnetic investigations focusing on studies about the ionosphere, but this was only partly true. In fact, Boyd was also tasked with providing the US government with information about potential military landing sites and other sensitive data, but she kept this to herself. As in her previous voyages, she was also the sole photographer, f lmmaker, and botanist. Te 1941 Louise Arner Boyd Expedition would be the f rst time she worked directly with Bartlett, although their paths had crossed many times before. Boyd was sure that they would work well together but nothing could be further from the truth.

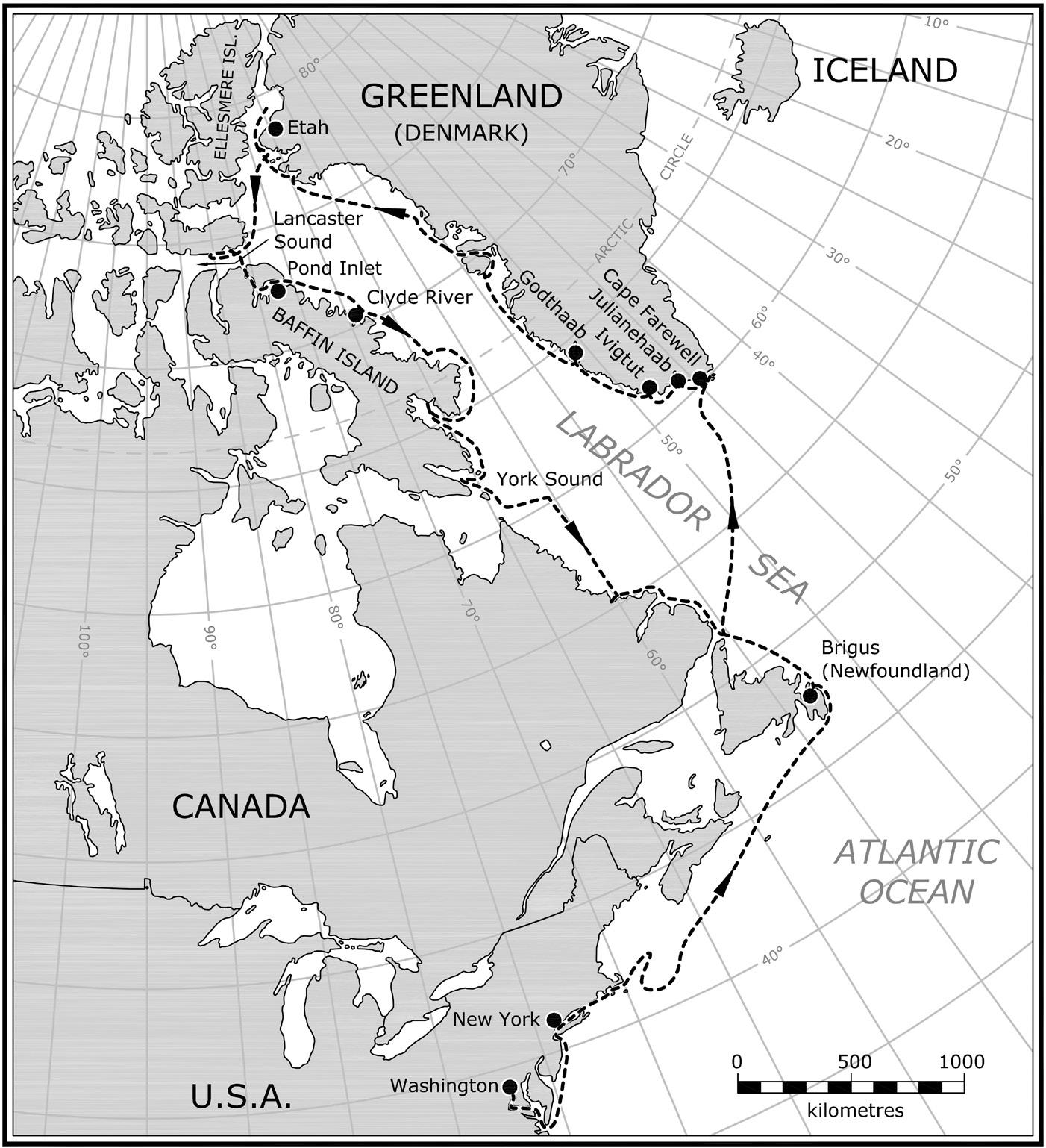

When the Efe M. Morrissey left Washington, DC, on 11 June, Boyd had high hopes for the voyage, but the ship was barely underway when hostilities between her and Captain Bartlett erupted. Both were of a mature age and in the latter stages of their careers and had f rm—some might say intransigent—views of how the mission should proceed. Te Morrissey was unfamiliar to Boyd and she made the mistake of comparing her unfavorably to her previous expedition ships—the Norwegian Veslekari and Hobby Te Morrissey’ s Newfoundland crew were fercely loyal to their ship and to Captain Bartlett, with whom they had sailed on many previous voyages. Tey did not

(top lef) Captain Bob Bartlet was a veteran Arctic expedition leader and navigator.

(lef) Ef ie M. Morrissey, 1930, Ford–Bartlet East Greenland Expedition.

take kindly to Boyd’s assertive manner. While the scienti fc sta f —physicist Archer Taylor, engineer Frederick Graceley and radio operator Tom Carroll—remained loyal to Boyd, the young ship’s doctor, John Schilling, openly undermined her authority as the expedition’s leader.

I don’t give a damn about her or her whole scientifc project which is so insincere on her part, her motivation being purely sel f sh and self-promoting. Well, it takes all kinds of people to make a world, and I suppose the Miss Boyds with all their money, scattered brains and loose tongues have their place.

T roughout the summer of 1941, the Morrissey worked her way north from Newfoundland to the west coast of Greenland, thus entering an active, volatile military zone. Before their departure, the Navy released a general advisory relating to the expedition:

“ Tere may conceivably be some jeopardy in connection with their operations and that any attendant risks are taken entirely upon their own responsibility. Conditions may make it impossible for the Navy Department to render assistance in the event of unforeseen contingency.” Tey were on their own. Louise Arner Boyd was never one to be dissuaded by the possibility of danger. Her strong sense of patriotism would not allow it.

After experiencing stormy weather of Cape Farewell at the southern tip of Greenland where Captain Bartlett displayed the full range of his vocabulary of profanities, the Morrissey dropped

anchor in Julianehåb (now known as Qaqortoq). Teir arrival was fortuitous as several ships, including the schooner Bowdoin, USS Bear, and USCG cutters Northland and Comanche were moored nearby. Te Northland was commanded by Commander Edward “Iceberg” Smith, who became a good friend of Boyd’s . All the other vessels were part of the Greenland Patrol—a US Coast Guard operation designed to defend Greenland against Axis forces and escort and supply Allied ships. Frank Meals, who became the commanding ofcer of Comanche, later wrote to Boyd to express his thanks for her work on Greenland, stating that it allowed him and his crew to “safeguard our navigation of these largely unsurveyed waters.” Boyd also met up with Colonel Benjamin Giles of the US Army Corps and ofered him assistance. He later wrote:

I was very glad indeed to receive the photographic negatives of KIPISAKO air feld and position of the main base, both as to longitude and latitude and magnetic declination. Both the pictures and the exact position of the air base serve a very useful purpose and on behalf of the War Department, I wish to personally thank you for your splendid spirit of cooperation in obtaining these data.

Te Morrissey continued sailing further up the Greenlandic coast, stopping next at Ivigtut (now known as Ivittut), which held special importance during the war. Ivigtut was the home of the world’s largest reserves of naturally occurring cryolite used in the aluminum smelting process. Te site was heavily protected

by American forces. Here they encountered USCGC Modoc, which was another member of the Greenland Patrol. Captain Bartlett had not been briefed on Boyd’s secret government mission and was impatient with her regular “socializing” in each community. Miss Boyd spent time meeting with Modoc’ s commander as well as with the mine administrator. Nearly eight decades later, I visited the abandoned remote Greenlandic community while working as guest lecturer on a cruise ship. Te mine closed in 1989, but many dilapidated buildings were still standing and I glimpsed unruly muskoxen roaming the hills. It wasn’t hard to imagine Louise Arner Boyd conversing with the authorities about wartime matters in such an evocative place.

Boyd and her team continued onwards to Godthåb (now the capital city Nuuk), where a new American consulate was being established. Crossing the Arctic Circle, the Morrissey stayed a short time in Tule before spending four days in Etah. Captain Bartlett’s journal of the entire voyage is housed in the Robert A. Bartlett Archives in the Bowdoin University library and presents his colorful account, but most of Louise Arner Boyd’s logs are missing. One sole exception is volume three of her 1941 expedition log (in the Marin Public Library, San Rafael, California). In it she wrote:

We left McCormick Bay after breakfast and set our course following this southern shore of Prudhoe Land. Ten, Good Bye! Adieu to Greenland! Leaving her shores bathed in brilliant sunshiny blue skies. Glassy waters studded with countless icebergs and the ripples and shoals of countless little auks!... I do so with the

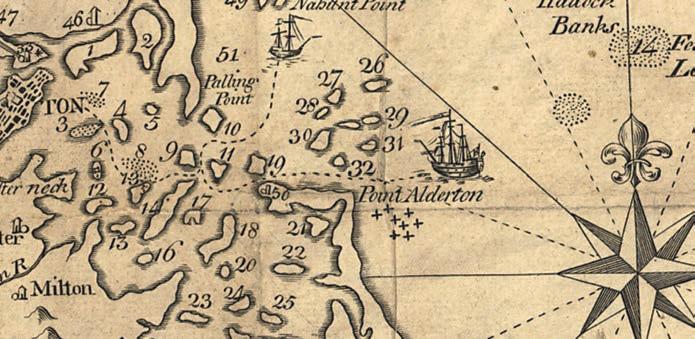

Map showing the route taken by the 1941 Louise Arner Boyd Expedition.

same prayer now for the f fth time repeated: “May my Arctic Gate again open and let me pass to the lands beyond in the Polar world. May I again return to Greenland!”

Te Morrissey navigated through Lancaster Sound and continued southwards, stopping at Pond Inlet, Pangnirtung and Clyde River in what is now modern-day Nunavut, Canada, before carrying on to Hopedale, Turnavik, and Battle Harbour in Labrador. Te Efe M. Morrissey arrived at the Coast Guard

pier in Washington, DC, on 3 November. Te United States formally entered the war only days later on 7 December 1941.

Captain Bartlett and Louise Arner Boyd bickered for months afterwards about petty details related to the contract and good relations between them were never restored, but the National Bureau of Standards and the United States government were delighted with the f lms, photographs, maps, and data generated by the expedition. Boyd received thanks and congratulations from various agencies,

including the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution, which informed Boyd that her data had solved many Arctic transmission problems with which his department had grappled. Te Radio Section of the National Bureau of Standards stated: “ Te data gathered within the auroral zone constituted the missing link in the NBS emerging radio weather forecasting service.” Boyd was retained as a military consultant by various branches of the US government. She never sailed on the Efe M. Morrissey again. T is was the last expedition of Louise Arner Boyd’s distinguished career as an Arctic explorer. After six Arctic voyages, she never made it back to her beloved Greenland again.

Dr. Kafarowski is a Fellow of The Explorers Club, a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and a board member of the Society of Woman Geographers. She is the author of The Polar Adventures of a Rich American Dame: A Life of Louise Arner Boyd (Dundurn Press, 2017) and Antarctic Pioneer: The Trailblazing Life of Jackie Ronne (Dundurn Press, 2022). She is currently working on her next book about women and exploration in Greenland, which will be published by Princeton University Press in 2026. She can be reached at joannakafarowski@gmail.com

Captain Bob Bartlet led four more war missions to the Arctic on behalf of the US government but died a few years later in 1946. Afer his death, the Morrissey caught fire while undergoing repairs in New York and was scutled. In 1948, Captain Henrique Mendes of Cape Verde Islands and his sister, Louisa Mendes of Massachuset s, purchased the ship and re-named her Ernestina, afer the captain’s daughter. For the next several decades, Ernestina carried goods and passengers between New England and the Cape Verde Islands. In 1982, the Republic of Cape Verde ofered the schooner to the Commonwealth of Massachuset s as a gesture of goodwill. She was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1990. Ernestina–Morrissey is now an education and training vessel for Massachuset s Maritime Academy, while simultaneously maintaining her role as a public educational vessel in New Bedford.

Coming Soon! Voyage Digital Media / Richardo R. Lopes, in collaboration with the National Maritime Historical Society, is in the final production stages of the documentary Sails Over Ice and Seas the Life and Times of the Schooner Ernestina- Morrissey. Release date will be announced by NMHS later this year.