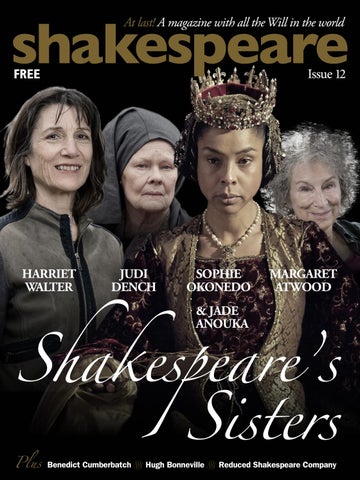

shakespeare At last! A magazine with all the Will in the world

Issue 12

FREE

Shakespeare’s Sisters HARRIET WALTER

JUDI DENCH

SOPHIE OKONEDO

MARGARET ATWOOD

& JADE ANOUKA

Plus

Benedict Cumberbatch � Hugh Bonneville � Reduced Shakespeare Company

shakespeare At last! A magazine with all the Will in the world

Issue 12

FREE

Shakespeare’s Sisters HARRIET WALTER

JUDI DENCH

SOPHIE OKONEDO

MARGARET ATWOOD

& JADE ANOUKA

Plus

Benedict Cumberbatch � Hugh Bonneville � Reduced Shakespeare Company