18 minute read

Translation & #WorldKidLitMonth: An Interview with Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

INTERVIEW

Translation & #WorldKidLitMonth: An Interview with Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

BY ALYSE MGRDICHIAN

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

I’m very excited to introduce you to Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp, if you haven’t met her already! As a translator of German, Russian, and Arabic, and a champion of international kid lit, I knew I wanted to pick Ruth’s brain. I met Ruth virtually last year, when Shelf Media Group was preparing for its Global Reads issue back in September. At the time, I was compiling a multitude of interviews with female translators and international authors, and thought Ruth would be a great addition to the piece. The bad news is that she was unavailable – but the good news is that, eight months later, we remembered one another, and now Ruth gets a whole article to herself! Below you can find our conversation, where she shares her journey as a translator and her passion for kid lit.

HOW DID YOU GET STARTED AS A TRANSLATOR, AND FOR HOW LONG HAVE YOU WORKED IN THE FIELD?

RAK: This interview feels well timed because I recently realized that it was 20 years ago that I completed my first freelance translation job. I’m sure I had no idea what I was doing back then when I boldly started touting my skills, half a lifetime ago. in my teens, I knew I wanted to work with languages. However, after a school visit to the European Parliament in Strasbourg, I saw myself as an interpreter rather than a translator. I trained as both, though, completing the very intense Masters in Translation and Interpreting at the University of Bath, UK – but while I barely scraped through the interpreting modules (my brain really doesn’t work that quickly), I found myself very at home in the role of translator: close analytical reading, research into new topics and terminology, getting drawn into Google rabbit holes, pedantic editing, and collaborating with co-translators and editors to produce the best work possible.

IS THERE A SPECIFIC REASON YOU CHOSE GERMAN, RUSSIAN, AND ARABIC?

RAK: I started learning French at school when I was 11, and German when I was 12, but it was a personal connection that made German the language I would really end up living with: after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we got to know a young family in Dresden, and I went to visit regularly from 1994, when I was 14. I can’t imagine my life without my (adopted) German family who are now in Dresden, Cologne, and Bavaria; I look forward to our next epic train journey to

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

visit them all. I started learning Russian aged 16, as it was offered as a lunchtime elective at my school, and I immediately fell in love. I went on to study German and Russian at university, accidentally majoring in literature, and again falling in love. I came to Arabic in my 20s when I was already a qualified translator, because of an unmissable opportunity to study it as part of my job as an in-house translator. I’m a life-long language learner, and if I can get paid to study, I won’t pass up that chance. Coming to a new language later in life is hard, of course. I know I have a never-ending project on my hands with Arabic, and will always be frustrated by how much I still have to learn! Over the years I’ve also had personal reasons for delving into French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Urdu, Norwegian, and most recently, Maltese and Ukrainian. For these last two, I aspire to be able to get by as a tourist (in hope of peace in Ukraine), and to read and co-translate short children’s books. At the moment, Maltese is on hold, and I’m trying to focus any spare time on co-translating samples of Ukrainian picture books with my dear friend, Ukrainian teacher and co-translator Anna Walden.

WHEN DECIDING WHICH PROJECTS TO PICK UP FOR TRANSLATION, ARE THERE ANY THEMES / PATTERNS IN LITERARY WORKS THAT YOU FIND YOURSELF GRAVITATING TOWARD?

RAK: I love this question because it makes it sound like I’m flooded with offers of work to choose from. It comes in waves: sometimes there’ll be a period where I accept everything I’m offered, at other times I’m more choosy. But most of my work comes about when a publisher has already bought the translation rights to a book, rather than me pitching proposals to publishers. Of the thirty book projects I’ve worked on, only one came about by my pitching. I’ve translated two books where I had done a sample, but it wasn’t actually me who found the publisher. There have been other times that I pitched books I longed to translate (a historical novel set in Ancient Egypt, and a Syrian prison memoir), but in both those cases the publishers that picked up the book turned out to have such a tight budget I couldn’t afford to work for them. Other translators such as Nicholas Glastonbury and Anton Hur

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

have written about the frustrations of pitching. I’m lucky to work mainly from German, where there are many literary agents and foreign reps selling rights, lessening the burden on translators to do that legwork. In other language combinations, including Arabic, the work of finding an English-language publisher falls largely to literary translators; it’s a long slog, and often only remunerated by the translation fee or royalties, if the translator ends up being commissioned to translate the book. And that’s a big ‘if.’

But it seems I’m becoming known for my interests because most translation proposals that land in my inbox are the types of work I care most about (history, historical fiction, children’s books, and fiction from under-represented perspectives), and follow themes I’m most passionate about (#ownvoices stories of refugees, of migration, of bilingual and bicultural upbringings, enabling stories of disability, and queer fiction).

YOU’VE TRANSLATED CHILDREN’S BOOKS, ADULT FICTION, AND LITERARY NONFICTION. HAVE YOU NOTICED ANY DIFFERENCES IN YOUR EXPERIENCE BETWEEN THESE THREE?

RAK: I recently realized that in one day I had looked up tools used by cobblers, horse anatomy, and radioactive isotopes ... and this was all terminology research for fiction and children’s books. In terms of process, there isn’t a huge difference between translating non-fiction and fiction, as I am still painstakingly cautious about reading around a topic to make sure I haven’t misunderstood. I compare Google images and trawl dictionaries, encyclopedias, and forums to select the most appropriate English terms, and litter the margins of my drafts with notes flagging passages I need to run by my more knowledgeable friends and colleagues once I’ve finished the first draft. The main difference is quantity: in the novel I’m currently translating (the sequel to Punishment of a Hunter), I’ll have a few horse-related questions for my expert friend Lucinda, but when I translated a 400-page book of the history of horses in art and culture, I had to book her for a whole weekend. So, the difference between fleeting mentions in fiction and an entire book on a topic might be the difference between a coffee and a quick chat with a friend, and paying a colleague for a day of their time answering my questions. To me, translation is always treading a fine line between confidence and

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

doubt. You need the self-confidence to put yourself out there, and to tell yourself that with the right support you can translate this book (I wouldn’t take on a text if I didn’t have a friend or colleague in my network with the expertise I could reasonably call on). But you also need to doubt everything, to question your assumptions about every single sentence. I even find myself looking up words I think I know inside out. Just because I’ve translated a word a hundred times, that doesn’t mean that this author is using it in the same way in this instance. And even if the meaning is the same, I’ll need to phrase something very differently depending on the context and the target reader.

OF ALL THE BOOKS AND STORIES THAT YOU’VE TRANSLATED, ARE THERE ANY PROJECTS THAT YOU’RE MORE FOND OF THAN THE OTHERS? IF SO, WHICH ONES, AND WHY?

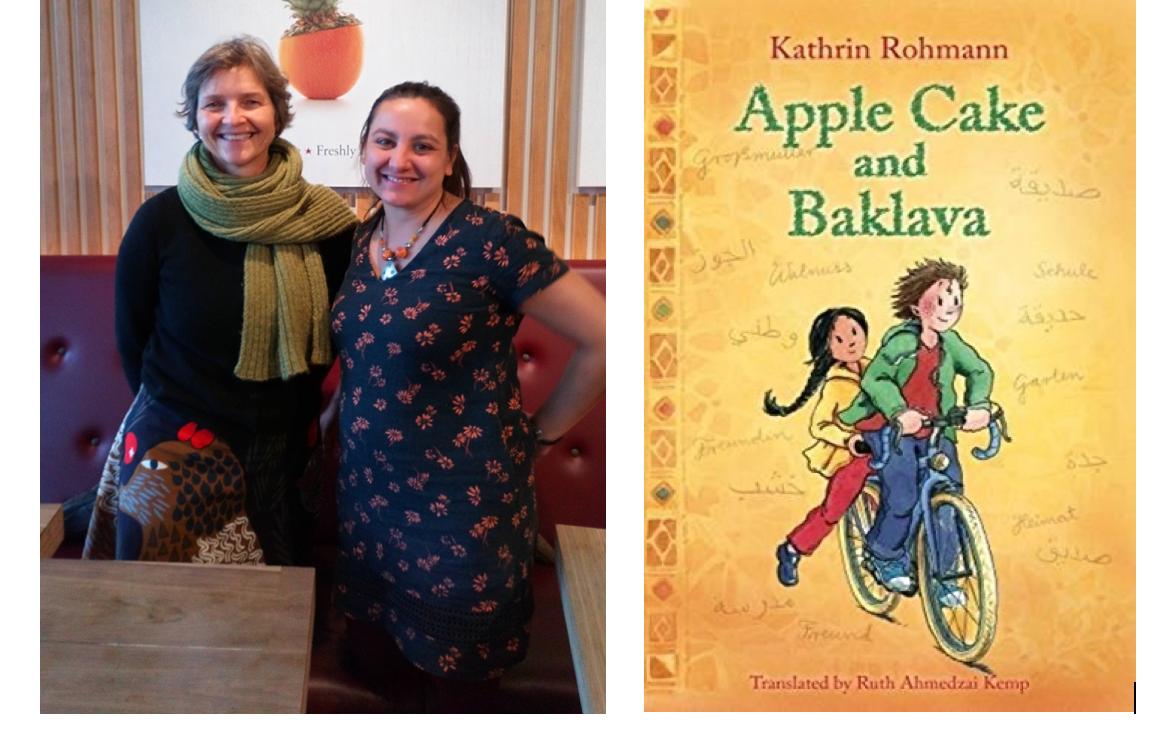

RAK: Of the children’s books, I’m most proud of having translated Kathrin Rohmann’s Apple Cake and Baklava. With loveable and convincingly flawed characters, it’s a perfectly structured middle grade story of starting out in a new country and new school, of loss and arrival. It cleverly draws a parallel between the experiences of German refugees in World War II and Syrians fleeing the ongoing conflict. My respect and admiration for Kathrin only increased when we finally met last year, when we gave a series of workshops, and even a theater performance, for primary school pupils hosted by the UK charity, the Children’s Bookshow.

Left: Kathrin Rohmann. Right: Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp.

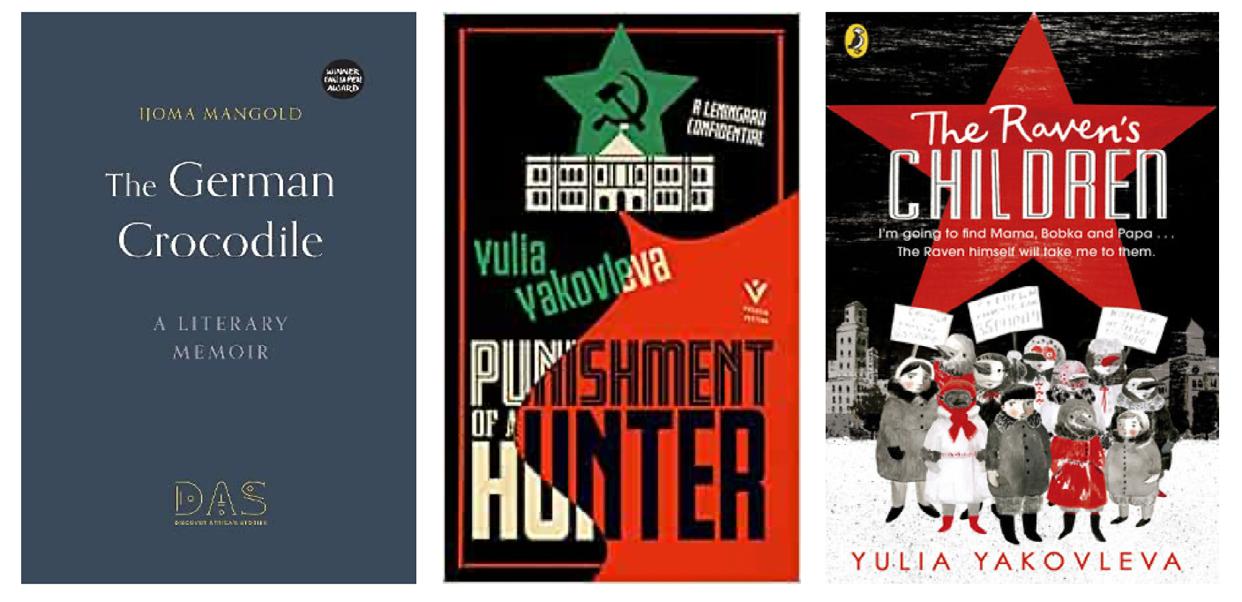

Of my longer translations for adult readers, I think the ones I’m most proud of at the moment are the two I translated during Covid-19 in 2020, when we were homeschooling our two boys, and I was translating in 40-minute chunks scattered throughout the day and night. They were 1) The German Crocodile by literary critic Ijoma Mangold, about meeting his

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

estranged Nigerian father in his 20s and growing up biracial in 1970s smalltown Germany, and 2) Punishment of a Hunter by Yulia Yakovleva – my first full-length adult novel from Russian – which, perhaps unsurprisingly, turned out to be much more challenging linguistically than her children’s novel, The Raven’s Children, which I had also translated. The second lockdown in 2020 was a tough period, and the burnout took some recovering from. Now when I look back at those books, I wonder how on earth I managed it. But both books were a glorious form of escapism from the anxiety of the pandemic. In fact, in the case of Yakovleva, it was an escapism into a much grimmer reality under Stalin that helped put my life into perspective.

IT SEEMS THAT YOU HAVE WORKED ON MORE THAN ONE TRANSLATION WITH CERTAIN AUTHORS. IS THE TRANSLATION PROCESS ANY DIFFERENT WHEN YOU HAVE A MORE PERSONAL / FAMILIAR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE WRITER?

RAK: It is certainly reassuring to embark on the second in a series (I’m currently working on the second in Yulia Yakovleva’s Leningrad noir trilogy for Pushkin Press), confident that I already have a good working relationship with the editor(s) and knowing that the author is happy to help with queries. I hope to have a shorter query list for Yulia than I did with Punishment of a Hunter, but I also look forward to having that conversation with her, whereas with a new author I’m always quite nervous about bothering the author. I never know how many questions are too many.

It can also be much quicker to translate a second or third work by an author as you become familiar with the author’s quirks, their syntax, their use of irony and rhetorical devices. Not to mention the vocabulary and metaphorical space their language inhabits: every time I come across what’s clearly an author’s pet phrase, I ask myself ‘Should I translate it in the same way each time to make a connection and highlight that repetition, or is it not

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

worth emphasizing? How much is it part of ordinary language and how much is it this author’s (or narrator’s) idiolect?’ We translators fret in this kind of detail over every single sentence, so having gone through some of the textual analysis of an author and their relationship to language and storytelling, you have a head start with book two.

WHAT IS SOMETHING THAT YOU WISH YOU’D KNOWN BEFORE GOING INTO TRANSLATION?

RAK: Having worked for years as a commercial translator, I started to specialize in literary translation (i.e. translating copyrighted works for publishers) around 8 years ago, and in the first years I certainly would have benefited from more practical knowledge about rights, licensing, royalties, and negotiating tactics. And yet, I suspect that no matter how much you know about publishing, you have little negotiating clout to start with, and you learn to secure better terms with each new contract. It took me many years to research these topics, and to feel confident enough to ask my colleagues about fees and royalties. Most of what I have learned over the years was from joining the UK’s Society of Authors, ALTA (American Literary Translators’ Association) and ETN (the Emerging Translators’ Network, a practical and collegial Google group for early-career and aspiring literary translators; the US equivalent is ELTNA), where we tend to have an admirably open conversation about translator rights. Members of the Society of Authors can send in their draft translation contracts for expert advice. I do this with every new book contract: it helps the Society update their advice on current ‘observed rates’ for translation, and I learn more about my rights as translator every time.

WHAT IS, TO YOU, THE BEST PART OF YOUR JOB?

RAK: I won’t lie – it’s the thrill of seeing one of my translations on the shelf in a bookstore, or even better, in the window! Or that special feeling when a friend sends a photo of the book their sister is currently enjoying, having realized it’s one of my translations. With social media and all the translator forums I’m part of, translation isn’t the solitary profession it once was, but the best bit is – after many, many months of hard work – finally reaching the stage where I have something to share with

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

the world. I try not to always give my books as birthday presents (sorry to all the friends and family I have done this to!) but it’s always heartening to see the interest friends show in my books, and how much support there is across the translator community for each other’s work. My Twitter timeline is full of translators reading and raving about each other’s latest books!

I wouldn’t translate if I didn’t enjoy the process itself, but it is a perverse, painful kind of enjoyment. I find the first draft agonizing, where I’m unpacking everything that the author has done and working out how to word it all in a new language. Now that I share an office with my husband, he tells me that I sigh a lot when I’m working. I’m much happier and calmer the closer the translation is to being finished!

COULD YOU PLEASE TELL ME A BIT ABOUT YOUR FORTHCOMING TRANSLATIONS?

RAK: My next two translations to be published are both from German, and they’re examples of the kinds of bicultural literature that really interests me. The literature of migration, perhaps. Swiss-Slovak author and activist Irena Brežná's The Thankless Foreigner will be published next year by Seagull Books, as a part of their Slovak Series. I started translating this mesmerizing novella in 2012 as part of New Books in German’s flagship Emerging Translators program; the sample was my first ever paid literary translation. It's a short, experimental novel about the many ways to be a refugee, about language and identity, about public service interpreting and translating other people’s trauma, about assimilation and the refusal to assimilate.

Brežná was recently awarded the Hermann Kesteren Prize by the German PEN Centre for her lifetime achievements as someone who ‘worked tirelessly throughout her life for justice and freedom and gave dissidents and the persecuted in Eastern Europe a voice.’ She has also just been awarded the Pribina Cross, one of Slovakia’s highest state decorations, given by the President to Slovak citizens who have made a significant contribution to the economic, social, or cultural development of the country.

And for Amazon Crossing, I’ve just finished translating Split by CroatianGerman novelist and fellow translator Alida Bremer: a richly atmospheric whodunnit set on the Adriatic Coast amidst the turmoil of 1930s political

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

unrest, on the precipice of war. It’s full of early twentieth century movie stars, political leaders, the sights and smells of the Mediterranean, ancient history, and above all: food. It has made me long to visit the Adriatic and read more of Croatian literature.

WHAT IS THE OVERLAP, IF ANY, BETWEEN YOUR LIFE AS A TRANSLATOR AND YOUR LIFE AS AN AMBASSADOR FOR CHILDREN’S BOOKS? WHAT, TO YOU, IS THE IMPORTANCE OF CHILDREN’S LITERATURE?

RAK: My interest in children’s publishing began as I started to translate children’s books, but as my own children grew older and I thought more about what I hoped they might experience of the world, of countries and cultures very different than our own, I realized that there is a role for translators and publishing professionals in opening up access to stories from other places, other traditions. I also taught Arabic and Russian in my local high schools for several years, alongside translating, and it seems to me that reading international children’s/YA books, and exploring the practical and creative process of translation in the classroom, can be a compelling motivation for young people to learn another language.

On a political level, 1) reading beyond our borders, 2) foregrounding children’s book creators of color, and 3) exploring literature from parts of the world we will never visit or perhaps never meet someone from, are all steps toward thinking about global citizenship, and about social justice on our planet. To me, it’s about anti-racism, anti-bigotry, and decolonization from the earliest part of the school journey: questioning whose stories we listen to the most, and where exclusionary biases skew our perspectives of the world. I think even primary school pupils are open-minded enough to challenge our received thinking, and if reading stories from other places can open up discussions about society, about the way we live our lives, then we are never too young to start exploring.

PLEASE TELL US ABOUT WORLD KID LIT MONTH, WHICH YOU HELP OVERSEE. WHAT IS THE DESIRED IMPACT, AND WHAT DOES IT ENTAIL?

RAK: World Kid Lit Month, celebrated every September since 2016, is a month to do exactly that: to

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

#readtheworld, or at least dip a toe in and start to explore world literature for kids and teens. It might be books and authors from another country or another continent, books in English published on the other side of the globe, or books for young people translated into English from other languages.

The annual event started as the #WorldKidLitMonth hashtag on Twitter, but the #worldkidlit community is gradually getting the message out to schools, libraries, and bookshops worldwide, showing how September is the perfect time to promote global reading for young people. Above all, it’s a dedicated month to shine a light on a vibrant and diverse area of children’s publishing that can be difficult to navigate; on the World Kid Lit website, we share book lists and reading maps, and link to resources to help readers choose a country and learn more about it through a book.

Why September? International Translation Day falls at the end of the month: a day to recognize the essential service performed by translators and interpreters, the craft that enables international communication and cooperation. In the US, September is also National Translation Month, so #WorldKidLitMonth is a way of advocating both for more translation within children’s publishing, and for more discussion of children’s publishing within the literary translation community.

The success, I think, of the growing World Kid Lit community is that it’s a hub for readers and advocates of international children’s literature in all sectors (publishing, bookselling, libraries, education, research), and we hope that in time it will both help readers to explore beyond their borders, while also demonstrating to publishers the interest and demand for more ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse books.

INTERVIEW CONTINUED

Please join us next year, in whatever way works for you: share a translated kids’ book on Instagram, ask your library to stock more graphic novels in translation, write to your favorite publisher and ask them why they’re not publishing more Francophone African writers, for example, or YA from South America. You could create or expand a Wikipedia page about your favorite Vietnamese illustrator, or about India’s children’s literature prizes, or go into your local school to talk about fiction from whatever country they’re studying in Geography or History. Whatever you do, please share it on social media! We love hearing the diverse ways that people pick up the idea of #WorldKidLitMonth and run with it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp is a literary translator working from Arabic, German, and Russian into English. She translates fiction and nonfiction, and has a particular interest in history, historical fiction, and writing for children and young adults. Her translations include books from Germany, Jordan, Morocco, Palestine, Russia, Switzerland, and Syria. See her full publications list. Ruth is a passionate advocate of world literature for young people and diversity in children’s publishing. She is co-editor of ArabKidLitNow! and Russian Kid Lit blogs, and writes about global reading for young people at World Kid Lit, Words Without Borders, and World Literature Today

Never miss an issue!

SIGN UP FOR A FREE SUBSCRIPTION TO SHELF UNBOUND MAGAZINE.