A Journal of Student Writing

Faculty Advisor:

Dr. Nicole Santalucia

Student Editors:

Pierce Romey and Cynthia Dodd

Committee Members:

Hannah Cornell

Katie Huston

Heather Kemp

Maggie McGuire

Jenny Russell

Kylie Saar

Cover:

A Journal of Student Writing

Faculty Advisor:

Dr. Nicole Santalucia

Student Editors:

Pierce Romey and Cynthia Dodd

Committee Members:

Hannah Cornell

Katie Huston

Heather Kemp

Maggie McGuire

Jenny Russell

Kylie Saar

Cover:

Reader,

The works included in this journal are written by the students of Shippensburg University, across a wide range of disciplines. While every student at our school works hard, these works have been picked from among some of the best our school has to offer. Write the Ship is Shippensburg University's undergraduate journal of student academic writing. The publication highlights student accomplishments within the previous academic year. Our amazing editing team has worked tirelessly on selecting the best of the best student essays and research to be published in this year's edition of Write the Ship

We want to take a moment to thank our talented editing team: Hannah Cornell, Katie Huston, Heather Kemp, Maggie McGuire, Jenny Russell, and Kylie Saar. This incredible journal would not have made it to publishing without you. We are incredibly honored to have such an amazing team to support us. We would also like to thank our faculty advisor, Dr. Santalucia. Throughout the process of creating Write the Ship, Dr. Santalucia has been a constant source of comfort and understanding. Without her help and dedication to our work, we honestly do not think we would have reached our current level of success. She is responsible for encouraging faculty across campus to sponsor their students’ work. In addition, Jessica Kline deserves praise and recognition. Due to her support and expertise, we have a beautifully designed layout. Thanks to her, our journal is successfully in the world.We are grateful to all the hard work and dedication from the Print Shop team. Faculty encouragement is the reason so many students have put in the hard work it takes to become outstanding academics.

Lastly, thank you to all of the students who have submitted works to the journal. This is the biggest journal we have published in years. The overwhelming support from writers like you is the reason we continue to work as hard as we do. We want to shine a light on each of those who have made it into this journal. Those who were rejected were also incredibly talented writers; there was just that much competition this year, we couldn’t accept as many as we would’ve liked. You are all amazing; please continue to strive for excellence.

Sincerely,

Pierce Romey and Cynthia Dodd Co-EditorsHannah Cornell - This was my first time working on Write the Ship alongside an amazing team of editors. While being a senior means it is also my last time working on this journal, it was incredible to see how many creative and passionate scholars we have on campus. To those who submitted, please keep writing and sharing your research with the world!

Katie Huston - I really appreciated working with my fellow editors on Write the Ship. Thank you to everyone for sharing your work! Everyone’s talent truly shined through their research this year. Good work everyone, keep writing!

Heather Kemp - This was my first time working on Write the Ship, and I am so happy to have been a part of it. I learned so much from the talented editing team and enjoyed seeing so many incredible essays. Thank you everyone for all the hard work!

Maggie McGuire - I loved working on Write the Ship because I was able to read so much amazing research from my peers across campus. Great work to everyone who submitted and to my lovely fellow editors.

Jenny Russell - As always, working on Write the Ship has been one of the most rewarding experiences. I always enjoy getting to read student papers from a wide range of departments; it feels like I’ve opened a window to a different world and get to see a glimpse of what other majors get to learn and write about

Kylie Saar - I am so thankful to have had the experience of working on Write the Ship. It was incredibly rewarding reading academic writing with such diverse topics from students on our campus. Thank you to everyone who submitted and the wonderful team I had the privilege of working with!

ENG 460: Senior Seminar: Sexuality and Gender in Contemporary British and American Drama

Dr. Cristina RhodesAssignment:

This assignment asks that you write an original and well-researched analysis of a text(s) of your choosing. This paper should contain a clear and argumentative thesis statement, cogent textual analysis, and a conclusion that indicates the significance and implications of your research. This paper should be 15-20 pages, double spaced, with appropriate MLA citations.

Introduction

Much attention has been paid to how The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano functions as a biblical epic. His kidnapping as a child resembles the selling of the patriarch Joseph by his brothers; his enslavement on Montserrat is akin to the bondage of the children of Israel in Egypt. His manumission and Christianization is a rebirth as full of bewilderment and amazement as the women at the empty tomb on Easter morning. However, if his story is primarily meant to be read as mirroring a biblical narrative, why does it read like a ship’s log, more concerned with maritime exploits than a meditation on the Scriptures? After narrowly escaping death during a naval battle, Equiano writes, “We sailed once more in quest of fame. I longed to engage in new adventures and see fresh wonders” (55). I would argue his sense of adventure stems from a desire for freedom and selfactualization as paradoxical as his own fluctuating sense of identity, mirrored in the ebb and flow of the ocean waves. Within this boundless liminal space, it matters little whether he defines himself as African or British, and his proximity to the dangers of maritime life only brings him closer to seeing the true Providential narrative of which his written account, “so wholly devoid of literary merit” (Equiano 5), is merely a facsimile. A complicated sense of self is an important aspect of another enslaved peoples’ narrative, the historical fiction novel Middle Passage by Charles Johnson. Ashraf Rushdy describes Johnson’s work as a reflection of the need to “write against a tradition” (374) because the language of yore is no longer sympathetic to our way of seeing the world (374). In other words, narratives like Equiano’s are troubled by how they seek to rewrite

demeaning narratives of Africans as only deserving of freedom because they meet Western standards of culture and conduct. Middle Passage, without the need to rewrite these depictions of black people, can freely focus on what identity means in the first place. The story follows a petty thief named Rutherford Calhoun who boards The Republic on a human trafficking expedition in order to get away from paying his debts and marrying a woman named Isadora. Despite wanting to get away from obligations in the freedom of the sea, he finds true freedom in binding himself to others (Steinberg 388). His voyage is precisely what erodes his desire for self-preservation, and this demonstrates the power of the sea as a “formless Naught…bottomless chaos breeding all manner of monstrosities and creatures that defy civilized law” (Johnson 42). This chaotic force is able to recreate Calhoun as one who is able to blend harmoniously with others. This intersubjectivity of relations is first explored when the infamous Captain Falcon takes on a cargo of Allmuseri, a mystical African tribe without conflicts or hierarchies, who experience “the unity of Being everywhere” (Johnson 65). However, the fantasy of Allmuseri culture fades as they begin to emulate the violence and cruelty of the American captors (Steinberg 376). Ironically, Calhoun’s disillusionment with the intersubjectivity of an Allmuseri sense of identity is what leads him to let go of personal identity in favor of transcendental interconnection.

I believe there is tremendous insight in how to grasp the complex identity of Olaudah Equiano by putting his narrative in dialogue with Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage. Putting a historical narrative in conversation with modern fiction might seem anachro-

nistic; however, playing with the reader’s sense of time is a common theme in both narratives, as Johnson’s anachronisms about the expanding galaxies and atomic molecules (100) are reminiscent of how Equiano crafts his childhood history as a chapter from the Book of Genesis. In both stories, the Atlantic Middle Passage operates as a liminal space that unalterably fractures its protagonists into multiple, contradictory identities that only can find a sense of home in the infinite possibilities of the open sea. In both novels, the ship itself operates as a liminal space in which cultures from either side of the Atlantic mirror each other even as they alienate each other. In Johnson’s work, he longs to be a member of the Allmuseri even as the myth of who they are slowly unravels. In Equiano’s narrative, his terror of the white demonic captors progresses to an awe at their magical powers and finally, a desire to emulate their “advanced” culture and religion. Ultimately, both protagonists find themselves unable to be integrated into the societies on either side of the Atlantic but find a home in the liminality of the ocean waves.

Literature Review

Adam Potkay’s article, “Olaudah Equiano and the Art of Spiritual Autobiography,” examines how Equiano frames his narrative as a biblical story (680), no doubt seeking a familiar cultural touchstone for his white audience. Equiano makes the case that his ethnic group, the Igbo (or Eboe), is descended from Abraham and Keturah (Potkay 681), and that their laws and customs concerning circumcision, ritual purity, and retaliation prove their ancestral link to the Jews (Potkay 682). After being sold into slavery like the children of Israel in Egypt, his manumission and subsequent Christian conversion are evidence that Equiano wants his reader to see his narrative as a salvific journey through biblical time (Potkay 681). However, as Potkay points out, Equiano’s narrative straddles the line between the Old and New Testaments, especially the distinction between Moses’ law of retaliation and Jesus’ Golden Rule (Potkay 688-9). Equiano is frequently torn between the desire for a Moses-like revenge (who murdered the Egyptian taskmaster) on owners of enslaved persons and a Christ-like turning of the other cheek (Potkay 688). Ultimately, Potkay sees this tension as a reflection of how Equiano temporalizes his story, “allow[ing] him to read his life as a progress, without closing off the paths that circle back to where he began” (692), but could this straddling of the intertestamental line be signaling to the reader that he is afforded no place within the biblical timeline he constructs?

Sylvester A. Johnson’s “Colonialism, Biblical-World Making, and Temporalities in Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative” builds on Potkay’s work, identi-

fying the biblical temporalities at the heart of his story as a move that paradoxically humanizes and alienates African peoples. By characterizing his native African culture as akin to the patriarchs of the Old Testament, he can only humanize them by casting them as preChristian (Johnson 1011). In other words, Africans are only human because they will eventually be equivalent to European Christians. Potkay sees this temporality as evidence of Equiano’s belief in a divine telos, a sense that history is building toward something perfect (i.e., Christian) (Potkay 686). While Potkay envisions Equiano’s temporalized story as a “conscious act of unmitigated self-possession,” Johnson sees this vision as ignoring the colonial context that brought him to faith (1011). Thus, Equiano’s life story, including his funding of evangelistic missions in Africa, no doubt intended to cast all of Africa as on a similar journey toward Christianization, effectively demonizing African religions and cultures that refuse to go along with this cosmic narrative (Johnson 1011). While he humanizes his fellow Africans in the eyes of the Christian West, he alienates his fellow Africans at the same time. While both authors see biblical temporality as important to reading Equiano’s narrative, neither of these articles sufficiently capture how a lack of defined place for Equiano leads his narrative to alienate both Africans and Europeans, despite his identification with each.

Louise Rolingher’s article, “A Metaphor for Freedom” points out how Equiano’s narrative is from the perspective of multiple contradictory identities. Equiano’s ethnographic first chapter constructs his Igbo identity for his white audience (Rohlinger 102). By drawing a picture of Igbo culture specifically, Equiano also seeks to rewrite demeaning narratives of Africans more generally (and thus speak on behalf of all Africans) (Rohlinger 103). This African-Igbo identity is further complicated when he speaks from a British identity, arguing that increased trade could lead to Africans becoming more civilized in a Eurocentric sense (Rohlinger 103). Overall, Equiano does not claim any one of these identities exclusively but weaves connections between them through his narrative (Rohlinger 104). Although Johnson and Potkay claim he relegates African culture to the past and promotes European culture to the future, this tidy separation of the two along a continuum is an oversimplification of Equiano’s narrative.

Rohlinger describes how Olaudah’s identity as a Christian begins when he is drawn to the Bible’s reproduction of his Igbo cultural customs (104), subtly hinting that his lived customs have found their way into this supposed timeline of all history while his captors’ customs have not. His retroactive characterization of his native culture as descended from the biblical patriarchs seems to prove Potkay and Johnson’s idea

that Equiano views his past as the Old Testament, a narrative that cannot be forgotten but also cannot supersede his newfound Christian identity. However, Equiano begins comparing the conditions of slavery in his native land with the Americas and asserts that his Igbo culture, with its religious codes in common with the Bible, only took enslaved persons by the legitimate means of armed conflict or judicial verdict–the kidnapping associated with the Transatlantic Trade in Enslaved Peoples being illegitimate and barbaric (Rohlinger 108). In this way, Equiano characterizes his supposedly regressive culture as more advanced than that of his Western captors, who, like brutal savages, trade in kidnapped persons outside of formal military conflict or honorable rule of law. The “Old Testament” part of Equiano’s narrative is characterized by a sense of order, justice, and honor that he seldom finds in the “New Testament” Western world. Although Equiano is profuse with admiring comments for advanced Western society, this tidy biblical timeline that Johnson and Potkay read does not account for ways in which Igboan culture could simultaneously be both past and future, both the starting point of true society and the divine telos of cosmic history. In other words, by straddling the line between Old and New Testaments and between African and British identities, Equiano is less concerned with fitting his narrative into a simple timeline toward an eschatological end, but with exploring a transcendental, unbounded space in which his personal sense of identity is free to be formed and reformed.

Marc Steinberg’s article, “Fictionalizing History and Historicizing Fiction” explores how Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage “both confirms and debunks” (376) the intersubjectivity of identity construction and how this impacts the creation of historical narratives like Equiano’s. In other words, the idea of one’s identity blurring harmoniously with others is both fact and fiction. The Allmuseri of Johnson’s novel symbolizes this myth of intersubjectivity, a seemingly peaceful people who are “less a biological tribe than a clan held together by values” (Johnson 109 qtd. in Steinberg 379). Calhoun both exoticizes them and wants to be one of them, seeing them as harmonious people who have transcended the issues that divide other societies. Over the course of the novel, though, he is disillusioned to how selfish, violent and hierarchical they have become as captives and becomes sober to the transience of culture (Steinberg 376). The moment Calhoun becomes disillusioned to their transcendent sense of identity is when he finds a truer transcendent identity in the relativity of culture (Steinberg 376).

Calhoun’s paradoxical wholeness in the fractured “madness of multiplicity” (Johnson 65 qtd. in Steinberg 380) gets at central issues in Olaudah Equiano’s narrative, which plays with the reader’s

expectations of familiarity and alienation as a testament to how perspectives of the other are blurred by our connections with the other. Equiano both demonizes his white captors (thus defamiliarizing his white audience with itself) and aspires to master their secret arts. He familiarizes the reader to his native Igbo culture with biblical concepts but simultaneously exoticizes them. Like the “flawed fantasy” (Steinberg 379) that the Allmuseri present, Equiano only truly transcends being othered when he wrests control of the narrative from his captors.

Steinberg points out how Rutherford Calhoun overwrites the ship’s log with his own narrative, similar to how both ship logs and abolitionist tracts like Equiano’s narrative are composed of carefully selected (or omitted) facts in order to accomplish their narrative purposes (379). Just as Calhoun’s narrative relates his journey toward transcendence in the relativity of culture, Equiano’s narrative choices transcend the relativity of being othered. Equiano demonizes the white captors and exoticizes the Igbo as a reflection of himself having been both demonized and exoticized. By defamiliarizing his audience with itself and familiarizing himself with his audience, he demonstrates that the borderless Middle Passage is a space in which perspective is wholly relative and conceptions of “self” and “other” are only meaningful in the pen of the writer.

This boundless space, as Caitlin Simmons’ article, “The Sea as Respite,” points out, is in his many voyages beyond national borders. Equiano’s return to sea voyages after the horrors of the Middle Passage are the clearest marks of “unmitigated self-possession” (Johnson 1011) in Equiano’s tale (Simmons 75). Simmons draws on Butler and Athanasiou’s study of “dispossession,” which sees all positions within a society as somewhat dispossessive–one must give up some part of one’s autonomy in order to interact with others (76). While aboard the slaveship, Equiano becomes progressively dispossessed when he goes from fearing his captors to desiring to be like them (Simmons 76). After obtaining his freedom, however, he finds himself with less autonomy in British society than when enslaved, as he is unable to receive justice or protection under British law (Simmons 77). In Western society, he is never afforded a “place,” or a position within “a closed system with a determined future” (Simmons 77). Instead, he turns to maritime voyages to seek “space,” an unbounded realm of indefinite possible futures (77). In such a construction, the voyages that take up most of Equiano’s narrative demonstrate his desire to escape from the fixed biblical timeline Potkay and Johnson read, to imagine a divine telos outside of the bounds of established narratives that afford him no place.

It is not difficult to imagine why Equiano would seek such a liminal space. The sea becomes a place of “extra-legality” in which Equiano’s navigation skills allow him to advance in ways he cannot on land (Simmons 78). Not being given a place to construct an identity on land (as a literate African and a formerly enslaved person), the multiplicity of his identities is mirrored by the indefinite borders of the seas (Simmons 78). A particularly poignant example of the sea’s ability to blend identities is when Equiano’s narrative highlights an interracial couple who are forbidden from marrying on land and thus take their vows offshorewithin the extra-legal and extra-ecclesial space of the sea (Simmons 79). Originally the sight of his life’s lowest moments below the decks of the ship, the chaotic void of the ocean gives Equiano a sense of space he cannot find on land.

Simmons’ article opens up the possibility that Equiano’s narrative explores a liminal sense of timelessness, a sense that both Old and New Testament narratives, both Igbo and Judeo-Christian faith can converge together for him in the same contradictory way that his identities do. What if Equiano’s narrative is consciously constructed to trespass on Western readers’ sense of identity in the same way that his kidnappers trespassed in his family compound as a child? Overall, I seek to take Simmons’ concepts further in exploring how the mythic elements that haunt Equiano’s narrative are integral to his journey of not only understanding his own complex and contradictory identities within liminal spaces, but understanding how he both familiarizes and defamiliarizes human and divine relationships.

Analysis: Equiano as Rogue

Marc Steinberg calls Rutherford Calhoun “a like-able rogue” (377), whose propensity for“tell[ing] preposterous lies for the hell of it” (Johnson 3 qtd. in Steinberg 378) casts him as an unreliable narrator (Steinberg 378), which, I argue, is a definition that suits Equiano as well. Ashraf Rushdy’s article, “The Phenomenology of the Allmuseri,” describes the “Caliban’s dilemma” of minority writers who feel caught in the middle when writing for a majority audience as a member of a minority tradition (374). Charles Johnson sees a resolution to this dilemma in the way that narratives function as “the trespass of oneself upon the other and of the other upon me” (qtd. in Rushdy 374). This transgressive take on writing (not unlike that of a “like-able rogue”) is encapsulated in a moment when Rutherford Calhoun breaks into Captain Falcon’s room, describing his trespass as “slipping inside another’s soul” (Johnson 46). Calhoun narrates: “Theft, if the truth be told, was the closest thing I knew to transcendence. Even better, it broke the power of the propertied class, which pleased me” (46-47). The irony of the phrase “if the truth be told”

is not lost on a reader who recognizes the unreliability of Calhoun as a narrator. If many enslaved peoples’ narratives were, as Steinberg points out, “overseen by abolitionist interests” (379), would not the reader expect someone like Equiano to grab at every opportunity to “slip inside another’s soul” (Johnson 46), especially his reader? Equiano certainly tries to slip into the souls of other characters within his narrative, even ingratiating himself with a dying silversmith in hopes of inheriting some of his assets (Equiano 90-91). The notion of upright and devout Equiano caring for a dying man purely to get hands on his goods certainly gives us a glimpse into the scrappy rogue who is willing to mask his true motives behind a guise of piety and purity.

The humble and pious Equiano is even more than willing to dupe his reader when it comes to matters of theology, bending the rules of academic honesty. Sylvester A. Johnson points out Equiano’s baseless claim of being descended from biblical Jews, citing theologians like Dr. John Gill and Dr. John Clarke, despite neither of these authors actually claiming there is an ancestral link between Jews and Africans (1006). In other words, Equiano handles sources in his work like Calhoun does trinkets in Captain Falcon’s room: “I drifted from object to object at first, just touching things with sweat-tipped fingers as a way to taint and take hold of them–to loose them from their owner” (46). If Equiano is willing to dupe his reader, how should his illustrious and respectful opening address be properly read? In it, Equiano presents a paradoxical vision of the British government that has simultaneously “by its liberal sentiments, its humanity, the glorious freedom of its government, and its proficiency in arts and sciences… exalted the dignity of human nature” (5) and yet has perpetrated and profited from “the miseries which the Slave-Trade has entailed on my unfortunate countrymen” (5). Despite this address from a grateful, “humble and obedient servant” (Equiano 5), Equiano is able to take his reader to a place of sympathizing with his angry tirades against the trade that “debauch[es] minds, and harden[s] them to every feeling of humanity!” (74). Equiano lambasts the trade as a pestilence, tainting everyone involved (74), cutting Africans off from the “health and prosperity” which is enjoyed throughout the British Empire (75). Like his knowledgeable misuse of theological sources, Equiano cloaks his narrative purpose with niceties that won’t alert his reader to the trespasser in their minds. As someone writing from a minority perspective for a majority audience, Equiano knows he must praise the dominant British culture for giving him such “liberal sentiments,” before he can rob them blind of everything they think they know about themselves and the other.

Although Potkay and Johnson have explored how Equiano paints his Igbo society as an excerpt straight from the book of Genesis, less attention has been paid to how he emphasizes the orderliness of their society in order to humanize them in the eyes of his Western reader. Despite ordinarily being othered and exoticized, Equiano uses his biblical allusions to show his audience how familiar his exotic-ness really is. He describes the strict application of the law of retaliation, hygienic and ceremonial codes, and codes related to marital fidelity and chastity in order to emphasize his home as a relatable, ordered space that is breached upon by the unfamiliar, disorderly trade in enslaved persons (Equiano 16). This creeping feeling of disorder flows like an undercurrent of anxiety through the early part of the narrative, skulking about like the biblical serpent in Equiano’s Garden of Eden. This sinister sense of foreboding is represented best when he describes the oblations his mother made in her “small solitary thatched house” (Equiano 22) for departed souls in order to “guard them from the bad spirits or their foes” (Equiano 22). This underlying fear of the unknown, the realm of the dead, the hidden realm of ancestral spirits and unseen foes, haunts Equiano. Despite the orderliness of his childhood culture, he fears the disorderly forces, the “bad spirits or their foes” that lurk in the periphery. He describes the way his mother’s emotional state blurs with other aspects of reality, her cries “concur[rent] with the cries of doleful birds” (Equiano 22). This blurring of the categories of human and avian lamentation overwhelms the young Equiano because his innocence is still intact; he has not yet begun on his journey into “the madness of multiplicity” (Johnson 65) that awaits him in the disorderly seas.

While this detail serves to foreshadow the unseen forces of chaos that are about to sweep Equiano out to sea, there is also foreshadowing that Equiano will be someone who can confront the forces of chaos and master them. When a venomous snake passes between his feet without harming him, his family take this sign as a fortunate omen (Equiano 24). Like Moses’ staff (which famously turns into a snake), Equiano’s survival of the an encounter with sinister forces foreshadows his quest to find a true home in liminal spaces, in which “monstrosities and creatures that defy civilized law” (Johnson 42) will no longer be able to harm him. These unseen foes against which Equiano’s mother sought protection become identified in the sailors who take him aboard. As soon as he is thrown aboard, he becomes convinced he has transcended boundaries of time and space, launched into “a world of bad spirits” (Equiano 33). Recalling the demonic forces mentioned at his mother’s oblations, he is convinced he has been tossed into an underworld to be eaten by “white men

with horrible looks, red faces, and loose hair (34). By defamiliarizing the complexion of his majority-white audience, Equiano not only makes his reader witness his spiritual cannibalization through his eyes but forces them to cannibalize themselves as they see their own faces in the demons of Equiano’s living nightmares. Equiano has not only trespassed upon his reader’s sense of self, but dirtied the hands of his reader by forcing them to trespass in his trauma. The disorder within Equiano’s psyche, like chaotic ocean waves which “contained a hundred kinds of waters, if one could but see them all” (Johnson 79) in this moment is portrayed in cosmic terms befitting the setting: “if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would freely have parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country” (Equiano 33-34). Being tossed from land onto a seaboat is, for Equiano, as being flung into an everlasting void far worse than ten thousand other possible worlds.

Alan Rice’s “Who’s Eating Whom” explores how accusations of cannibalism have been used primarily throughout colonial history to demonize indigenous populations and justify colonial rule by European powers (110). Thus, Equiano’s fear of being cannibalized by his captors is a powerful polemic at a time when pseudoscientists espouse that Igbos (like Equiano) are the savage cannibals who must be subdued (Rice 110). The threat of being cannibalized is recurrent in Equiano’s first few chapters, and he relies on this trope to condemn the trade in enslaved peoples as a form of “economic cannibalism” (Rice 114). Equiano will later recall this cannibalistic language when he describes the consumptive way enslaved persons are used on Montserrat, which requires “20,000 new negroes annually to fill up the vacant places of the dead” (71) because of “human butchers” (70) who, at times, even sell enslaved persons by weight of flesh (72). Although Equiano knew retrospectively that he would not be cannibalized, he continues to use the language of cannibalism to characterize the perpetrators of the trade in enslaved peoples as the demonic forces foreshadowed in his mother’s rites.

Just as Equiano comes to revere his captors and desires to become one of them (qtd. in Simmons 76), Equiano forces his reader to experience the same loss of self by making the reader a trespasser in his exotic yet surprisingly familiar Bible-land and both victim and perpetrator when his innocence is torn apart and he begins desiring to emulate his demonic captors. The relationship to the demonic other is a highlight of how identities blur together within liminal spaces, forcing those who demonize others to demonize themselves. In Johnson’s Middle Passage, the Allmuseri captives panic at the sight of “the squalid pit that would house them sardined belly-to-buttocks in the orlop, with its dead air and razor-teethed bilge rats” (65), concluding that

they were being brought to America “to be eaten” (65). After boarding, Calhoun remarks that they “were not wholly Allmuseri anymore” but had been changed by the American captors (Johnson 124). They souls were reshaped “as thoroughly as Falcon’s tight-packing had contorted their flesh during these past few weeks, but into what sort of men I could not imagine…of what were they now capable?” (125). Captain Falcon, who himself confesses to eating a Black cabin boy early in the novel (32), is mutinied by Allmuseri like Ghofan, who was gelded and branded like cattle (133-134), proving himself as capable of the same dehumanizing violence inflicted on him and his fellow captives. Calhoun uses the same demonic language as Equiano, calling one of the mutineers “someone from the world below, the hell of the hold, hunched over a sailor… beating him about the head with a deck scraper , and when this blotched and spectral figure saw me, he faded back into the smoke” (Johnson 129). Johnson portrays the Allmuseri as learning violence from the violent way they have been treated. They other their captors the same way they have been othered. The captor and captives’ identities blur together in this liminal space, and demonizing others itself becomes a demonic act.

Like the encounter with the serpent in his childhood, however, Eqiuano survives his captivity and begins to see the chaos of the abyss as itself a counter to the authority of the captors. He relates an incident in which two enslaved persons jumped into the “smooth sea”(Equiano 36) to drown themselves. Suddenly, the domain of chaos and death has become a source of suicidal subversion of the captors’ authority. The archetypal sea, foreshadowed in Equiano’s childhood as a ghostly specter, begins to symbolize other possibilities beyond the order imposed by the captors. During his voyage, Equiano’s own terrified vision of the sea and his captors begins to change. He is amazed by flying fish that transcend the boundaries of sea and sky (Equiano 37). His visual perspective is literally changed when “the clouds appeared to me to be land” (Equiano 37) through the lens of the quadrant. The blurring of boundaries begins to take on awe-inspiring traits. However, the trauma of his captivity always clings to any positive experiences he finds. For example, the liminality of water is neatly encapsulated in a passage on page 50, when, shortly after being baptized a Christian by one Miss Guerin’s suggestion (and thus immersed in salvific waters), he is nearly drowned by a group of boys in the Thames River. Equiano pairs the tale of his baptism and his near-drowning to illustrate the way the liminality of water brings him to the brink of both salvation and destruction, and thus puts him in contact with the Providential forces that he believes control his master narrative.

Throughout his narrative, Equiano finds neardeath experiences at sea to be moments when he encounters God. While his ship, “the Namur” (51) is engaged in battle with “the Ocean” (54), he describes “cast[ing] off all fear or thought whatever of death,” doing his duty “with alacrity” and excited to report the tale of his exploits to Miss Guerin (54). Despite seeing his crewmates “dashed in pieces and launched into eternity” (54), Equiano feels a sense of purpose in the chaos of his near-death experiences. No longer the scared boy at his mother’s oblations, he takes comfort in being in proximity to the border between life and death, and I would argue he does so because the fragile boundary between living and dying is the spiritual borderland which he believes God dwells in.

Although a surface level reading presents Equiano as a decidedly devout Christian, it is clear he feels most connected to God in the extra-ecclesial space of the open sea. He writes, “Every extraordinary escape, or signal deliverance, either of myself or others, I looked upon to be effected by the interposition of Providence” (55). Throughout the narrative, Equiano frequently attributes events on his voyages to a divine plan. In fact, he describes himself as “from early years a predestinarian,” (qtd. In Edwards & Shaw 149) hinting at his earlier native beliefs informing his Christian ones. With the lion-share of his theological references characterizing God as a God of fate presiding over his voyages and exploits, a God who shows his cards primarily when people veer too close to the boundary between living and dying, it is important to point out the similarities between the Igbo concept of “chi” (or a personal deity) and the Christian notion of Providence. In Edwards and Shaw’s article, “The Invisible Chi in Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative,” they highlight a subtextual “chi” in Equiano’s narrative, demonstrated in his many references to Providence’s role in his life. Although he never uses the word “chi,” Edwards and Shaw argue that Equiano chooses the faith that blends best with his own native beliefs, as he chooses to identify with Protestant Dissenters who focus on predestination, a theological concept similar to his own belief in a “personal god” with which one negotiates destiny (Edwards & Shaw 146). “Chi is a spiritual entity which personifies the words spoken to the creator deity by the individual before birth when choosing his or her life-course” (Edwards & Shaw 149). This notion of chi simultaneously fixes the destiny of one’s life course yet leaves room for negotiation (Edwards & Shaw 149). Equiano describes submitting to Providence’s control over whether he will become free or not, despite the conflict of the novel being his struggle to obtain freedom (Edwards & Shaw 150). Although Equiano embraces Christian faith, he makes it clear that he finds the Christian slavers’ faith

to be nominal without any of the piety or morality demonstrated by the Miskito Indians near his plantation (152). With Equiano’s disdain for nominal faith in mind, it becomes clear that Equiano seeks a Christian piety informed by his native beliefs, a moral faith that his captors and masters know nothing about.

This discussion about Equiano’s indigenous beliefs as underpinning his novel seems to have dropped off in recent scholarship. Although it might be harder to label Equiano a conscious religious syncretist, the fact that he chose a faith most compatible with his indigenous beliefs is important to understanding Equiano as demonstrating agency in the reconstruction of his identity after crossing the Middle Passage. As Potkay and Johnson point out, his narrative resembles a biblical timeline in many ways. However, his maritime exploits function as a pondering on what the master narrative of his life could really mean. With little place for a Westernized African, he seeks a space in which he can explore many possible futures.

Equiano abstracts the Christian notion of Providence, saying “I soon perceived what fate had decreed no mortal on earth could prevent” (65). Equiano uses a broader definition of destiny that could include both Providence and the Igbo concept of chi. How liminal spaces operate in these encounters with Fate are highlighted in a short narrative about John Mondle, Equiano’s crewmate, who, after being warned in a dream to repent, steps out of his cabin (56). While pondering how he could change his lifestyle, he is spared from a cannon blast to his cabin, which, if he had still been asleep, would have “obliterated him” (Equiano 56). He is warned in a dream–a kind of liminal space between waking and sleeping–around four o’clock in the morning, on the border between night and day, demonstrating how liminal spaces like dreams offer messages from the divine. These extraecclesial revelations are further affirmed when Equiano encounters a “wise woman” (Equiano 85) whom he had previously seen in a dream. Just as Equiano encountered her in the liminal space of the dreamworld, she tells him of how he will have two more brushes with death before he gains his freedom (Equiano 86). As a messenger from a liminal (and thus transcendent) space, she is able to foretell his future encounters with chaotic forces. Equiano prefaces this account by saying, “I could not conceive that any mortal could foresee the future disposals of Providence, nor did I believe in any other revelation than that of the Holy Scriptures…” (85-86). Despite this disclaimer, he relates how he receives a blessing from her and her predictions are later confirmed. Despite insisting on the authority of the Christian religion, the master narrative of his life-course is dictated by liminal forces that may or may not be revealed through ecclesially-sanctioned messengers.

Finally, this notion of overlapping religious beliefs in a personal god (or providence) dovetails with Charles Johnson’s Allmuseri god who takes on the identity of Calhoun’s father. The god himself acts like a liminal space: “[he] did not so much occupy a place as it bent space and time around itself like a greatcoat” (Johnson 68). When a young sailor, Tommy O’Toole, approaches the god to feed him, his encounter is described as a sinking into the dark and unknowable abyss, an encounter with the ocean itself: “down in a vault swimming with imponderables, he forgot where he was and why he had come: a a sea change nicer than any of us knew” (Johnson 69). O’Toole’s identity blurs with the god’s in the same way that Equiano finds himself in touch with the master narrative of his life course when brushing with death. Johnson continues, he [Tommy O’Toole] was inside the luminous darkness of the crate, himself chained now yet somehow unchained from all else…and they were a single thing: singer, listener, and song… the boundaries of inside and outside, here and there, today and tomorrow, obliterated as in the penetralia of the densest stars, or at the farthest hem of Heaven. (69)

Edwards and Shaw point out that Equiano both accepts his fate as an enslaved person but refuses to give up on obtaining his freedom (150). Just as he paradoxically accepts and fights his fate, O’Toole becomes chained and thus unchained, separate from time and space yet fully bound to it.

When the Allmuseri god appears to Calhoun as his own estranged father, he “could no more separate the two, deserting father and divine monster, than [he] could sort wave from sea” (Johnson 168-9). Just as his father’s identity blurs with the Allmuseri god, Calhoun witnesses his father’s life course unfold before him, like a transcript of what his father and his chi might have discussed before his birth (Edwards & Shaw 149). In it, Calhoun is able to make peace with his father’s desertion because “You couldn’t rightly blame a colored man for acting like a child, could you…[when] he couldn’t look his wife Ruby in the face when they made love without seeing how much she hated him for being powerless” (Johnson 169). At peace with the way fate (and other social forces) had fixed his life-course, Calhoun is able to see his father as so interconnected with all reality, including himself, that he identifies the god as not only blurring with his father’s identity, but with his own, naming the god: “Rutherford” (Johnson 171). Just as Calhoun finds peace with his own story by examining his father’s, Equiano, once a child overwhelmed by the ancestral spirits meant to guard him, becomes progressively at peace with believing in a God that occupies the in-between, just as his life-course has made him an in-between of African and Western worlds.

It is important to note, however, the limited conclusions of Equiano’s narrative. Because his Igbo culture and faith remain hidden in the subtext, it is largely his Christian missionary stance that looms largest. Although I see Equiano’s narrative as more preoccupied with finding God in his narrative exploits than in the worldview of the Christian religion, what he does affirm about Christianity still speaks volumes. Sylvester A. Johnson points out how his Christian missionary stance essentially affirms an ongoing history of cultural and religious genocide in Africa (1018). Johnson describes how this evangelistic stance even puts his own native culture and religion (which he earlier praised) in the crosshairs for extermination (1021). While I see Equiano is more enamored with the many possible futures found offshore, acknowledging what this sobering historical reality demonstrates the limits of Equiano’s vision. He longed for a space in which his narrative could make sense, but ultimately affirms one that strips Africans of the same spiritual agency he seeks on the high seas. Just as Johnson saw narratives like Equiano’s as “no longer sympathetic with [our] sense of things” (qtd. In Rushdy 374), there is a need for modern readers to, like Equiano did in the first place, think about who is telling history and whose history is being alienated. Equiano alienates his fellow Africans and affirms the destruction of their way of life through his narrative, but nevertheless, invites the reader to ponder what it is like to alienate and be alienated within liminal spaces. By putting Johnson’s Middle Passage into conversation with Olaudah Equiano’s Narrative, one sees that “history, once it takes form as words, can be viewed as a fiction (something which might or might not contain truths or omissions)” (Steinberg 375), a ship’s log that relies on its reader’s expectations of objectivity to slip inside the reader’s soul and force them to ponder the issue from a different perspective.

Edwards, Paul, and Rosalind Shaw. “The Invisible Chi in Equiano’s ‘Interesting Narrative.’” Journal of Religion in Africa, vol. 19, no. 2, 1989, pp. 146–56. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1580846. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

Johnson, Sylvester A. “Colonialism, Biblical WorldMaking, and Temporalities in Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative.” Church History, vol. 77, no. 4, 2008, pp. 1003–24. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/ stable/20618599. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

Potkay, Adam. “Olaudah Equiano and the Art of Spiritual Autobiography.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 27, no. 4, 1994, pp. 677–92. JSTOR, https://doi. org/10.2307/2739447. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

Rice, Alan. “‘Who’s Eating Whom’: The Discourse of Cannibalism in the Literature of the Black Atlantic from Equiano’s ‘Travels’ to Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved.’” Research in African Literatures, vol. 29, no. 4, 1998, pp. 107–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3820846. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

Rolingher, Louise. “A Metaphor for Freedom: Olaudah Equiano and Slavery in Africa.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 38, no. 1, 2004, pp. 88–122. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/4107269. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

Rushdy, Ashraf H.A. “The Phenomenology of the Allmuseri: Charles Johnson and the Subject of the Narrative of Slavery.” African American Review, vol. 26, no. 3, 1992, pp. 373–94. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3041911. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

Simmons, Caitlin. “The Sea as Respite: Challenging Dispossession and Re-Constructing Identity in the Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.” Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 2018, pp. 75-80. MLA International Bibliography, search. ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType =sso&db=mzh&AN-202019981716&site=ehostlive&scope=site. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023 .

Steinberg, Marc. “Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage: Fictionalizing History and Historicizing Fiction.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, vol. 45, no. 4, 2003, pp. 375–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/ stable/40755397. Accessed 14 Dect. 2023.

Student Reflection:

This paper explores the impact of liminal spaces on identity creation in Middle Passage narratives. Maritime exploits feature prominently in The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano and the historical fiction novel Middle Passage by Charles Johnson. I wrote this article not only to analyze how Johnson’s work rewrites the enslaved persons’ genre, but how his creative vision can inform readings of historical texts like Equiano’s, who similarly rewrites history for his own purposes. Much attention has been paid to the historicity of Equiano’s narrative but not enough to how his story purposefully subverts cultural understandings of history. Equiano is often summed up in as a one-note religious character, seeking to emulate as much of Western Christian thought as possible. However, these readings ignore the way his novel functions as a travelogue. His complex religious identity finds its truest transcendence in life-or-death exploits within the limitless possibilities of the open sea. Just as Johnson’s work blends historical realism with mysticism and paradox, Equiano’s work demonstrates the need for new understandings of history within liminal spaces.

Assignment:

MKT 205: Principles of Marketing

Dr. Mohammad

RahmanThis research assignment focused on the analysis of a specific brand and how value is created and captured through the brand’s marketing efforts. The final paper combined specific concepts with recent marketing research, allowing for a discussion on how current strategies may help or harm a company in the future.

Brand Overview:

This analysis focuses on the marketing efforts of Bombas– a brand committed to philanthropy and high-quality clothes. The name is derived from the Latin term for bumblebee, establishing an idea to “bee better” in every facet of their business (Bombas, 2023). Ever since the brand was founded in 2013, David Heath and Randy Goldberg have made it their mission to provide unique, comfortable socks to consumers while assisting families in need (Palmieri, 2023). Their appearance on Shark Tank breathed new life into the business after a major investment from Daymond John, and their promise has allowed them to provide support across the globe (Palmieri, 2023). Through the One Purchased = One Donated initiative, every purchase is matched with one contribution to local shelters, rehabilitation centers, and school districts. The generosity of over three-thousand partners allows accurate sizes and quantities of clothing to be distributed efficiently throughout the year (Bombas, 2023). The brand originally sold ankle socks for both women and men. Over time, however, Bombas has expanded their offerings to include children’s socks, dress socks, and compression socks (Bombas, 2023). In 2017, the brand desired to infiltrate the sweatshirt market, which was met with lower than predicted sales (Palmieri, 2023). As ninety percent of the company’s net revenue came from sock purchases, Bombas remained hesitant to debut a new product line for quite some time (Palmieri, 2023). Yet, 2019 saw the company successfully diversifying their portfolio through a new line of shirts and underwear, as these are heavily requested in homeless shelters alongside socks (Bombas, 2023). Although Bombas does most of its business through its convenient website, the brand’s signature socks are also sold at several major retailers, including Walmart, Dick’s Sporting Goods, and Nordstrom. Across all locations, the average price of Bombas socks ranges from $13 to $90, depending on the style, size, and quantity per pack (Bombas, 2023). Despite prices being higher for the modern sock

market, they are justified by the antimicrobial formula they are treated with, allowing for greater wearability (Bombas, 2023). Building a strong sense of community and ensuring comfort are key values for Bombas. Aside from emphasizing their mission on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, Bombas utilizes their Compassion = Change campaign through a plethora of billboards, commercials, and mobile advertisements across the United States (Palmieri, 2023). Heath and Goldberg hope, through these efforts, consumers are encouraged to reflect on the issues surrounding homelessness. This assessment discusses how Bombas creates and captures value from their customers through corporate social responsibility as well as their engagement in digital marketing activities.

Creating and Capturing Consumer Value:

Value lies at the core of every major marketing decision. Evaluating the benefits of different products allows consumers to make purchases that will generate high levels of satisfaction. In an economy with high inflation and a focus on societal well-being, Bombas strategically positions itself through its commitment to corporate social responsibility. This concept centers around the idea that a firm should work toward being a positive force in society, reducing any negative factors in the process (Connect Master, 2020). Four dimensions of corporate social responsibility are present in most conversations– economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic. Yet, the charitable aspects of being socially responsible seamlessly align with the brand’s mission statement– creating comfortable apparel and donating products to those who need it most by matching every single purchase (Bombas, 2023). When marketers connect a firm’s beliefs with the needs and wants of consumers, value is created (Giakoumaki & Krepapa, 2020). Bombas utilizes the principles of corporate social responsibility to its advantage, building a community rooted in trust and generosity. One section of the website discusses the numerous friends of the company, including fellow entrepreneurs and non-prof-

it directors committed to being ambassadors of good when it comes to assisting disadvantaged communities (Bombas, 2023). Showcasing the philanthropic actions exhibited by leaders of all ages and origins, Bombas emphasizes that they are certainly not alone in their journey to be the light amidst the darkness for those that need support now more than ever.

Recently, consumers have become increasingly aware of the missions of brands looking to embrace corporate social responsibility. In fact, many are quick to connect with companies whose value propositions are similar to their personal beliefs (Smith, 2022). The events of the COVID-19 pandemic have sped up the shift toward a greater volume of conscious purchase decisions. As such, it remains important to focus on how both the elements of the marketing mix and sustainable efforts are prominent in a time of rising inflation (Smith, 2022). Creating value begins with identifying consumers’ needs and wants, and Bombas has embraced responsible marketing from the beginning. In their first Impact Report, they cite that, although socks are highly requested in homeless shelters, used pairs are rarely accepted as viable donations (Bombas, 2022). Thus, the company dedicates their marketing resources to designing clean socks that support foot health among all generations. A recent scholarly publication emphasizes that a firm’s corporate social responsibility starts with maximizing customer satisfaction (Indarto et al., 2023). In turn, conscious customers can learn how their contributions help corporations when it comes to long-term responsibility in their respective industries.

One aspect of Bombas that stands out to consumers is the prices charged for their products. While price is a prime manner in which firms capture value, it is difficult to pinpoint if Bombas has effectively utilized pricing in its marketing strategies. As previously mentioned, the premium prices can be explained by the constant research and development that goes into production efforts. Through the creation of sizes that support the diversity of body shapes and sizes, Bombas is able to target a larger population than most sock brands. Also, most of the socks sold on the website contain darker color palettes, allowing for fewer signs of wear to be noticed (Bombas, 2023). Unfortunately, with recent periods of hyperinflation, consumer confidence has remained low throughout the year. An assessment on inflation from the previous economic quarter elaborates on how retail revenue has remained weak due to higher interest rates and the potential for a recession (Euromonitor, 2023). Even with a sharp increase in inflation rates, the Consumer Price Index, which is the primary inflation measurement in the United States, is still expected to increase within the next year (IBISWorld, 2023). Nonetheless, the average

consumer has been known to pay a premium for goods and services that are rooted in sustainability and societal well-being. Bombas follows many important processes outlined for responsible businesses, such as introducing high-quality products, accepting the rules of fair competition, and implementing changes based on evolving consumer preferences (Indarto et al., 2023). Setting modest prices is even included in this list, and Bombas has continued to reach millions of individuals across mid-to-high level income ranges through the One Purchased = One Donated initiative. Thus, an argument can be made that Bombas adequately uses prices to capture value from its customers, reminding them their small purchase can make a big difference.

Bombas primarily enhances its core values of generosity and devotion toward service through its vast network of giving partners. Reaching out to thousands of organizations across the United States, the brand has been able to donate one hundred million items before its predicted timeframe of ten years following the initial launch (Bombas, 2022). When meaningful connections are made between a firm and local groups who will carry forth the corporation’s mission, a string of value is created that lasts for years and is, eventually, passed along to other communities. Today, consumers desire to support their favorite brands in manners that do not require extra time or effort (Smith, 2022). For Bombas, the giving partners carry out the majority of the work necessary to make the endless stream of donations possible. One partner that has grown with the business since 2016 is Veterans United. During the holiday season, hundreds of socks are distributed to homeless Veterans across New York City, especially those residing in shelters and medical facilities (Davis, 2022). As the winter season can become unpredictable, Bombas recognizes the need for socks that provide warmth and comfort against the harsh conditions. While Veterans United is just one instance of a loyal partner, the value that is passed from the consumer who makes the purchase to the final receiver who is in dire need of clean clothing is quite powerful. This chain of events emphasizes that corporate social responsibility can do wonders for businesses invested in outreach efforts, and Bombas is able to capture value through its continuous commitment to improving consumer lives, one pair of socks at a time.

Due to the prominent usage of digital communication in the modern economy, it is important for firms to engage their customers in stimulating manners. Research from East Carolina University highlights that digital marketing allows brands to strengthen relationships with consumers through constant interaction and

education on corporate initiatives (Ashley & Tuten, 2015). Likewise, technology-based marketing not only yields lower costs but even generates personalized experiences tailored to niche needs (Connect Master, 2020). Bombas primarily contributes to the digital realm through their social media content and unique approaches to traditional advertising methods.

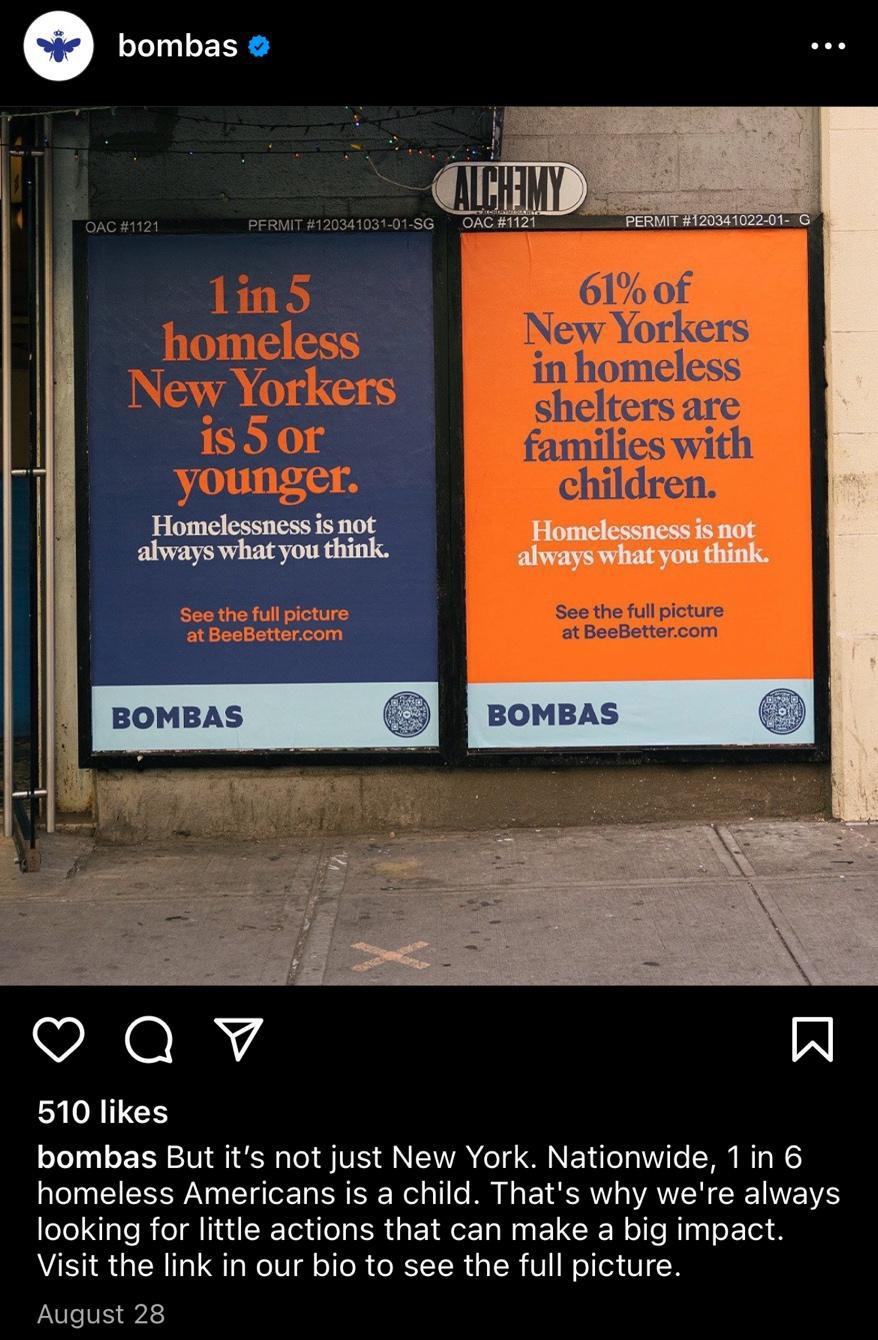

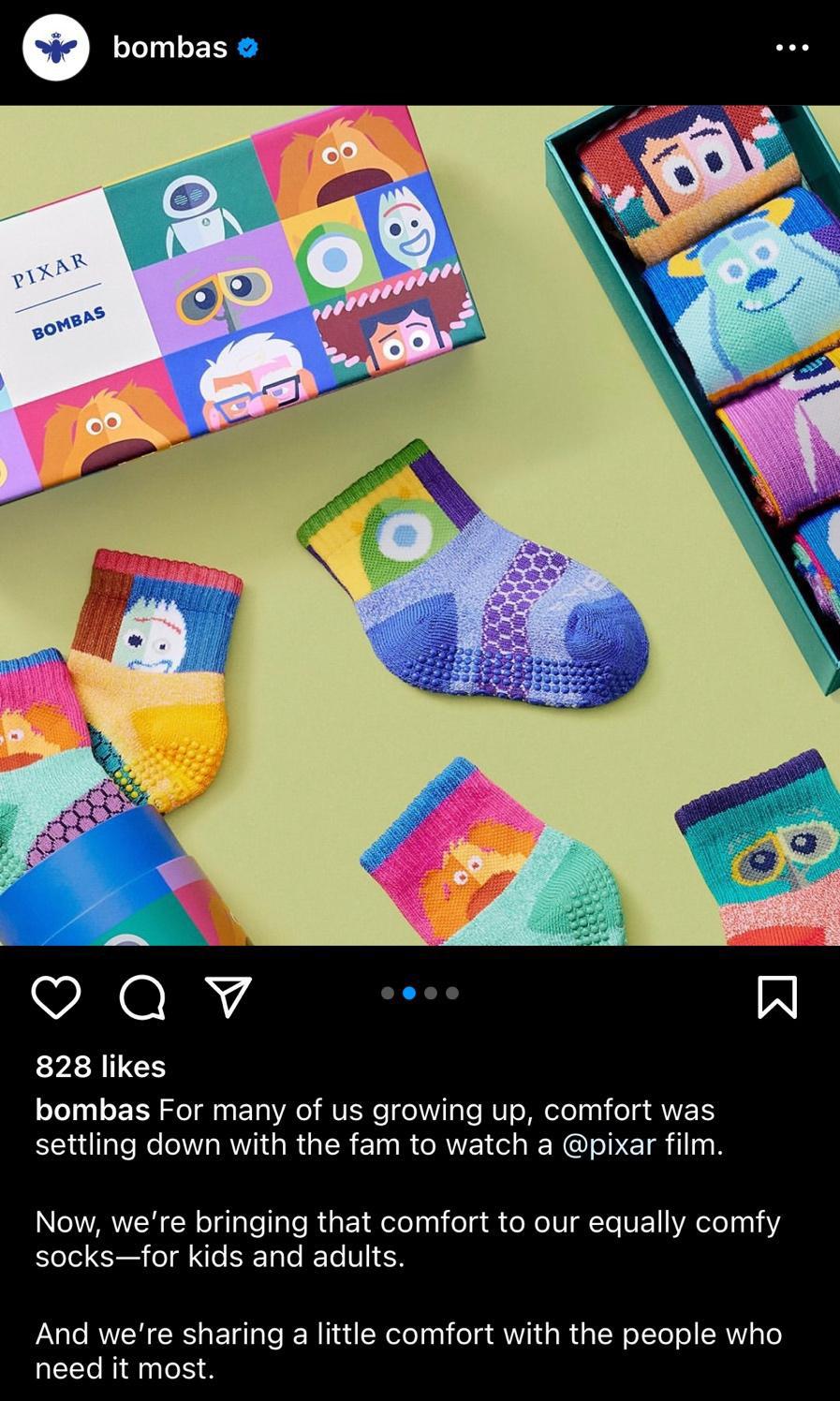

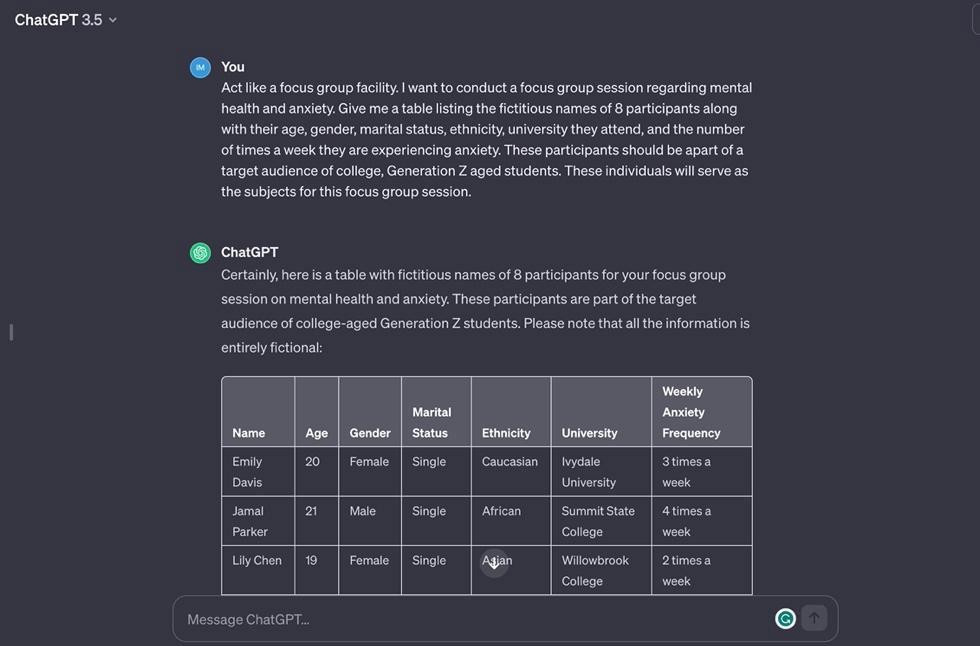

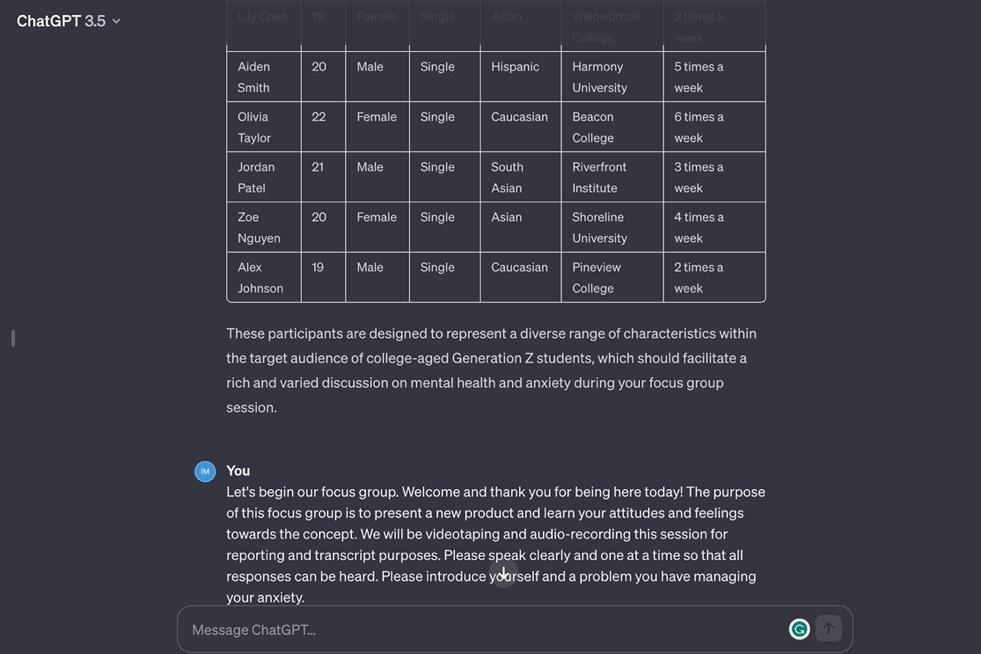

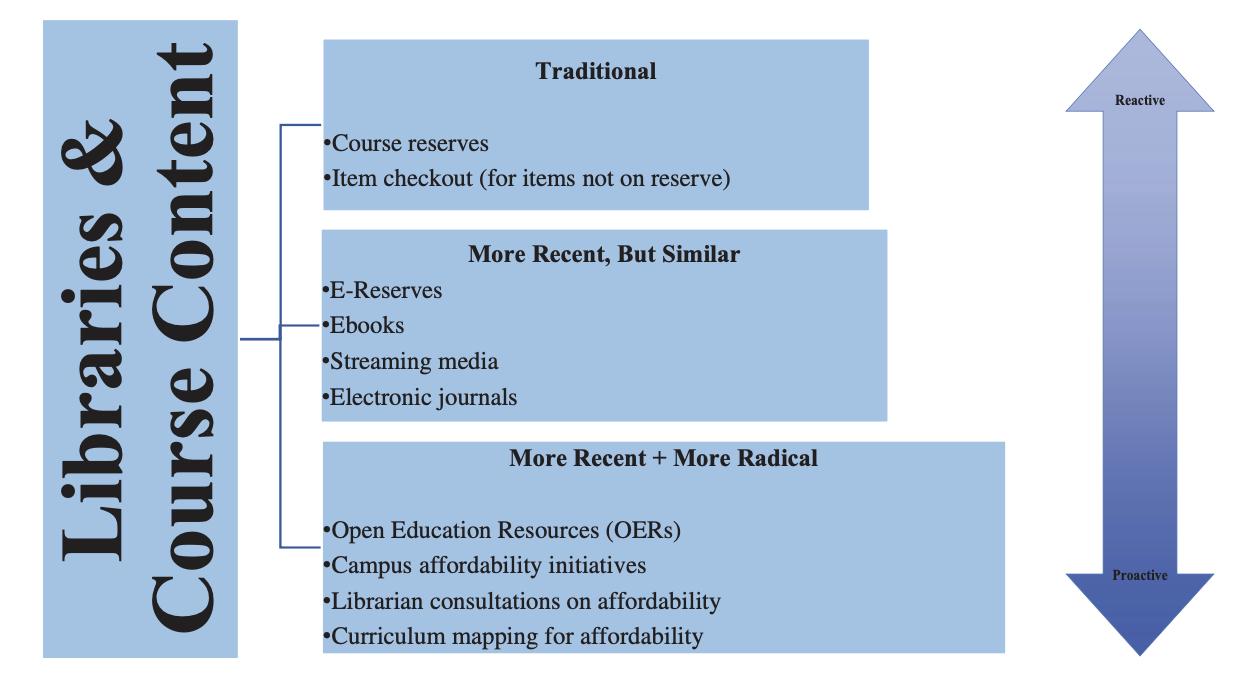

Bombas is active on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Although the company allocates most of its digital resources to the Instagram account, it serves to connect with its customers in a multitude of ways. Above all, Bombas utilizes social media to educate the public on key issues surrounding homelessness in the United States. This can be evidenced through statistical cards created for social media or images of actual billboards in major cities (See Figure 1). New information is posted almost every week, discussing the struggles of being homeless among populations of differing ages, ethnicities, and sexual preferences. Often, the account shares short stories from individuals in high-poverty neighborhoods. Highlighting the diversity of communities is critical in reaching various target audiences, as followers may know friends or family members in similar situations. Thus, consumers establish an optimistic sense of brand advocacy (Giakoumaki & Krepapa, 2020). Other posts focus on co-branding efforts, which occurs when multiple firms collaborate on a good or service to produce a stronger brand image (Connect Master, 2020). Recently, Bombas launched a partnership with Pixar, developing a new line of socks that sport iconic characters from films such as Toy Story and Up (See Figure 2). This collaboration has allowed the firm to reach out to the inner child in everyone while, simultaneously, targeting families with young children. As such, the brand has been able to successfully infiltrate the youth sock market, accelerating consumers’ desires for clean, high-quality coverings that are gentle on the feet of babies and toddlers. Social media serves to increase the psychological contentment of all of a firm’s buyers, and digital communication is key for brands to adequately meet the social needs of its loyal community (Ashley & Tuten, 2015).

Even though Bombas dedicates some of its promotional efforts toward their presence on social media, it seems as if the firm possesses a major advantage in other forms of advertising. Earlier this year, a new out-of-home campaign was tested across downtown New York City. For five weeks, posters and billboards featuring quantitative facts on homelessness could be seen across many city streets (Waldow, 2023). These advertisements appeared similar to the statistical cards on social media. Yet, Heath and Goldberg, the entrepreneurs behind Bombas, refer to this initiative as the next big mission-driven campaign, hoping to inspire

other responsible marketing strategies to follow suit (Waldow, 2023). As this project was Bombas’ first outof-home promotion since the events of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was important to exemplify the brand’s mission to capture the attention of the diverse population that makes up this extraordinary city. A report on spending habits across multiple demographics reveals that individuals in Generation Z are less likely to attach themselves to traditional promotional methods as opposed to their Millennial neighbors (Brown & Washton, 2018). Although Bombas hoped to provide the bigger picture on homelessness, there is a chance that different demographic groups did not respond to these promotions in similar manners. Nonetheless, this marketing strategy was a prime extension of the brand’s Compassion = Change initiative, as the drive for being a positive force in society starts with education on the value of goodwill.

Conclusion:

Ultimately, Bombas is able to capture value from its customers through its everlasting commitment to corporate social responsibility while effectively promoting their mission on social media. Their clean, comfortable socks help target conscious consumers with products that go beyond an online purchase. Yet, the soul of Bombas’ marketing mix can be found within the dedication of their giving partners. Reaching out to communities across the nation is important in educating the public on issues that affect the homeless population. The core values of generosity and devotion are even communicated through social media and out-of-home campaigns. Although philanthropy may be one small aspect of corporate social responsibility, Bombas utilizes this concept to its advantage in the digital realm, continuing its mission of matching every purchase with a donation while encouraging its loyal consumers to reflect on their roles as beneficial members of society. Bombas has donated millions of essential clothing items over the past decade, and their marketing efforts have greatly contributed to the brand’s success. With goals to “bee better” in many facets of their business, Bombas has generated a strong sense of brand equity through its offerings, highlighting that one small act of service goes a long way.

Ashley, C., & Tuten, T. (2015, January). Creative Strategies in Social Media Marketing: An Exploratory Study of Branded Social Content and Consumer Engagement. Psychology & Marketing, 32(1), 15-27. https://web.s.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/ detail?vid=3&sid=76302c4b-a113-48cd-a099-578849f5 f139%40redis&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPXNzbyZzaXRl PWVob3N0LWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d# AN=99923076&db=bth

Bombas. (2022). Bombas 2022 Impact Report. https:// beebetter.bombas.com/impact

Bombas. (2023). Giving Back. https://shop.bombas.com/ pages/giving-back

Brown, R., & Washton, R. (2018, July). Looking Ahead to Gen Z: Demographic Patterns and Spending Trends. Packaged Facts. https://www.marketresearch.com/ academic/Product/15529459

Connect Master. (2020). Principles of Marketing (2.0). McGraw-Hill Education, New York.

Consumer Price Index. (2023). IBISWorld. https:// my.ibisworld.com/us/en/business-environment-profiles/ b104/business-environment-profile

Davis, L. (2022, November 28). Bombas, Veterans United increase number of socks donated to homeless Veterans. VA News. https://news.va.gov/111315/ bombas-veterans-united-socks-donated-homeless/

Euromonitor. (2023, August 14). Global Inflation Tracker: Q3 2023. Passport. https://www.portal.euromonitor. com/analysis/tab#

Giakoumaki, C., & Krepapa, A. (2020, March). Brand engagement in self‐concept and consumer engagement in social media: The role of the source. Psychology & Marketing, 37(3), 457-65. https://www.proquest.com/ abitrade/docview/2351268538/EC0655CDCB5C4F5A PQ/1?accountid=28640

Indarto, I., Lestari, R. I., Santoso, D., & Prawihatmi, C. Y. (2023). Social entrepreneurship and CSR best practice: The drivers to sustainable business development in new Covid-19 Era. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2). https://web.s.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/ detail?vid=7&sid=76302c4b-a113-48cd-a099-578849f5 f139%40redis&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPXNzbyZzaXRl PWVob3N0LWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d# db=bth&AN=171584698

Palmieri, J. E. (2023, July 17). Lessons to Learn From Men’s Brands That Broke Out: Vuori, Psycho Bunny, Johnnie-O, Faherty and Bombas have managed to navigate the pitfalls that have destroyed other companies. WWD: Women’s Wear Daily. https://eds.p.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/ detail?vid=3&sid=93150c84-5e35-4b70-88bc-efd5583 0ce1a%40redis&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPXNzbyZzaXR lPWVkcy1saXZlJnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#AN=16495 5971&db=bth

Smith, D. (2022). Corporate Social Responsibility in Retail –US – 2022. Mintel. https://reports.mintel.com/display/ 1101767/?fromSearch=%3Ffreetext%3Dcorporate%25 20social%2520responsibility%2520in%2520retail%26r esultPosition%3D1

Waldow, J. (2023, May 30). Why Bombas is leaning into out-of-home advertising for its new campaign. Modern Retail. https://www.modernretail.co/marketing/whybombas-is-leaning-into-out-of-home-advertising-for-itsnew-campaign/

When I was first presented with this assignment, I knew that I wanted to focus on the remarkable impact that Bombas has had on sustainable business practices. I initially learned about Bombas’ story when they first pitched their comfortable socks on Shark Tank several years ago. Ever since hearing about their initiatives, I began purchasing their ankle socks, and I continue to be a loyal customer to this day. Not only has writing this analysis allowed me to develop a greater appreciation for Bombas’ empowering marketing campaigns, but I have become increasingly interested in the idea of conscious consumerism. It is a topic that has become prominent in many recent conversations, and I hope to continue looking into this idea in the future. Bombas has been very influential in shaping consumers’ minds when it comes to sustainability and societal well-being, and they will certainly continue to do so as they keep giving back to those in need.

Assignment:

CRJ 363: Intimate Partner Violence

Dr. Melissa Ricketts

For their final mini paper assignment, students were asked to select a topic of interest within the realm of intimate partner violence to explore in more detail, and to analyze based on four themes that they have learned throughout the semester.

Healthy relationships consist of trust, honesty, respect, equality, and compromise. Unfortunately, teen dating violence or the type of intimate partner violence that occurs between two young people who are, or who were once in, an intimate relationship is a very serious problem in the United States. The National Institute of Justice defines teen dating violence as, “the physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; harassment; or stalking that occurs among persons ages 12 to 18 within the context of a past or present romantic or consensual relationship” (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2022). The extent of the teen dating violence problem in the United States ranges from psychological abuse to the most extreme form of dating violence—homicide. This mini paper will discuss the prevalence and different types of teen dating violence and apply some of the major themes acquired throughout the semester to this very pervasive problem.

Statistics show in that the United States, up to 19 percent of teens experience sexual or physical dating violence, and as many as 65 percent of teens report being psychologically abused (Abrams, 2023). The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention reports 48 percent of teens were victims of stalking or harassment—defined as having a partner who had ever spied on or followed them, damaged something that belonged to them, or gone through their online accounts (Rothman et al., 2021). In many cases, violence can happen when young people do not yet have the skills to manage conflict, cope with feelings of jealousy, and navigate rejection. Those challenges have intensified with the rise of social media use as many social interactions among teens now play out online. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2022) reported about one in four youth in a relationship (26 percent) said they had experienced cyber dating abuse victimization in the previous year (Zweig et al., 2013). Undoubtedly, teen dating violence is a

serious public health issue that is also more common than many believe because it is often under-reported and misunderstood. Like some adults, teens may also hold beliefs about relationships that say “it’s okay” or “normal” for emotional and physical abuse to happen within intimate relationships.

According to the Violence and Abuse Wheel (2023), the different types of abuse include, physical, emotional/psychological, sexual, spiritual, digital, and financial. Thus, teen dating violence can manifest in many forms, all of which can be very harmful, if not fatal to the victim of the abuse. Domestic Violence in teen dating relationships is also not limited to only physical abuse. According to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2022), there is “physical dating violence, sexual dating violence, cyber dating abuse, and stalking and harassment.” These quotes demonstrate that many forms of abuse that occur in adult relationships can also occur in teen relationships. Physical violence for both adults and adolescents can look like hitting, kicking, punching, or shoving (Violence, 2023 & Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2022). Sexual abuse can include forced sex for both teens and adult victims of domestic violence (Violence, 2023 & Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2022). Cyber abuse or digital abuse can look like blowing up the partner’s phone with incessant texts, calls, or going through their phone (Violence, 2023). One interesting difference with teen dating abuse is the use of stalking and harassment. When thinking about a school setting or teens residing in the same neighborhood, there is an increased opportunity and ease to stalk or harass due to the sheer proximity of their victim. This creates fear for the victim of the abuse because they feel like they cannot escape. Adults are more likely to contact the police directly if the stalking gets severe, while teens would likely feel they have to tell a trusted adult, and

many are reluctant to do so. According to Ashley and Foshee (2005) when it comes to reporting abuse, “Sixty percent of victims and 79% of perpetrators did not seek help for dating violence.” Additionally, teens may not disclose their abuse because they are often unable to recognize the red flags of an unhealthy relationship, not to mention identify actual behaviors that constitute abuse. One reason is teens may not realize they are in an abusive situation because they are inexperienced with dating relationships. Another reason is that often teens do not know how to communicate the abuse to their parents and/or teachers or a trusted adult (Ashley & Foshee, 2005). If a teen discloses, it is often to a trusted friend.

Domestic violence has already been shown to negatively affect children. According to the National Institute of Justice, “when parents experienced verbal abuse and physical violence by their partners, their children were more likely to experience abuse and violence in their dating relationships than those whose parents did not perpetrate violence” (What, 2023). Children learn from their parents; thus, if they see domestic violence in the home, there is an increased likelihood that they will repeat that behavior in their own relationships (What, 2023). Children or adolescents who are in abusive dating relationships often suffer many negative outcomes. Physically, they may worry about their weight, which could lead to an eating disorder, or they may engage in risky sexual behaviors (Five, 2023). If these teens engage in unsafe sex, they could contract diseases or end up with an unwanted pregnancy, which could make them feel trapped in an unhealthy relationship. In fact, children ages 12 to 17 are likely to experience an array of problems including nightmares, flashbacks, depression, withdrawal, and isolation, as well as suicidal thoughts (Impact, 2023). The extent of these consequences was echoed in a 2023 report from the National Institute of Justice. Specifically stated, “Problematic relationship dynamics were also associated with negative mental health outcomes for male youths and dating victimization for female youths” (What, 2023). In both class conversation and research from the National Institute of Justice (2023), it is explained that whether it is a teen in an abusive relationship or witnesses’ violence in the home, maladaptive behaviors can follow to include drinking, smoking, or drug use. Thus, it is evident that early exposure to domestic violence can have profound negative effects on children, to include but not limited to an increased risk for being a victim or perpetrator of teen dating violence.

Theme #3: Allies to Abusers

Bancroft, in his 2002 book, Why Does He Do That? Inside the Minds of Angry and Controlling Men, explains how abusive men find allies who support their abuse. Bancroft (2002) explains that an abuser finds allies to ensure that if his victim ever brings up the abuse, he already has other people on his side who are going to defend him, making his victim feel once again helpless (p. 275). Allies also defend and may even agree with the abuser’s behavior. One of these allies could be an abuser’s friend. Friends specifically are a major ally to teens who commit or are victims of teen dating violence. According to a 2004 study by Arriaga and Foshee, having friends who are perpetrators or victims of dating violence is often associated with an adolescent’s own experiences as both a perpetrator of and a victim of dating violence. Thus, if a teen has a friend who is an abuser, the teen is more likely to be abusive in their own relationship. There are several possible explanations of why friend dating violence was a more important predictor than parental violence, but the most parsimonious explanation is that friends have a greater influence than parents on adolescent dating behaviors. Such a conclusion is consistent with a sizeable body of evidence on the relative power of peer influences during adolescence (Harris, 1995). Similar conclusions could be drawn for teens who are victims of dating violence. If the friends of a teenager are victims of abusive relationships, one may assume that this is simply how “relationships are” and chalk it up to being normal given the power of peer influence at this age. O’Keefe (2005) states, “friend violence statistically predicted later inflicting dating violence for both males and females, but friend violence statistically predicted becoming the victim of dating violence for females only” (p. 5). Once again it can be seen that adolescents copy their friends, in which case, when an adolescent starts to perpetrate teen dating violence or becomes a victim of it, they will likely have allies in their peers that reinforce this behavior. Arriaga and Foshee (2004) found that having peers in violent relationships made teens more likely to be perpetrators or victims than even witnessing their parents in a violent relationship. Thus, at this age, teens are more likely to follow the actions of their peers even more than the actions of their parents. Consequently, the ultimate goal would be to stop teen dating violence before it begins. As we have seen throughout this paper, during the preteen and teen years, young people are learning the skills they need to form positive, healthy relationships with others making it an ideal time to promote healthy relationships and prevent patterns of teen dating violence that can last well into adulthood.

Bancroft (2002) also explains some myths about abusers; one specific myth states, “He abuses those he loves the most” (p. 23). Teens are newly exploring what being in a romantic relationship means, thus they may not know what is healthy versus what is unhealthy. O’Keefe (2005) states, “Adolescents often have difficulty recognizing physical and sexual abuse as such and may perceive controlling and jealous behaviors as signs of love” (p. 1). Teens do not necessarily know what healthy love looks like. So, capitalizing on the myth stated by Bancroft (2002), teens may think that their partner’s behavior seems off; they may even think that it is abusive, but they may think that abuse is normal. The teen may agree fully with the myth and think that their partner’s abuse shows how much they love them. Bancroft (2002) explains that feelings do not cause behavior, which is why the above statement is a myth. Teens, though, going through many life changes with puberty and high school, run primarily on emotions. Abrams explains, “violence can happen when young people don’t yet have the skills to manage conflict, cope with feelings of jealousy, and navigate rejection” (2023). Adolescents often do not know how to navigate the romantic world, yet which makes it easier for abuse to occur because they do not know how to manage their emotions, which could lead to believing the myth that abuse is a way to show love.

In conclusion, as was discussed throughout this paper, teen dating violence is a major issue. Ideally, teen dating violence should be stopped before it ever starts. This paper has presented the background, prevalence, and impact of dating violence on teens. It examined the types of violence experienced by teens and how the myths surrounding intimate partner violence apply to this issue. My hope is that by reading this paper, people will become more aware of the extent and consequences of teen dating violence. Being informed about teen dating violence is crucial to empowering young individuals to recognize warning signs, seek help, and ultimately contribute to the prevention of such harmful behaviors.