4 minute read

RSP: MEASURE DRAWING OF A TRADITIONAL SETTLEMENT

Advertisement

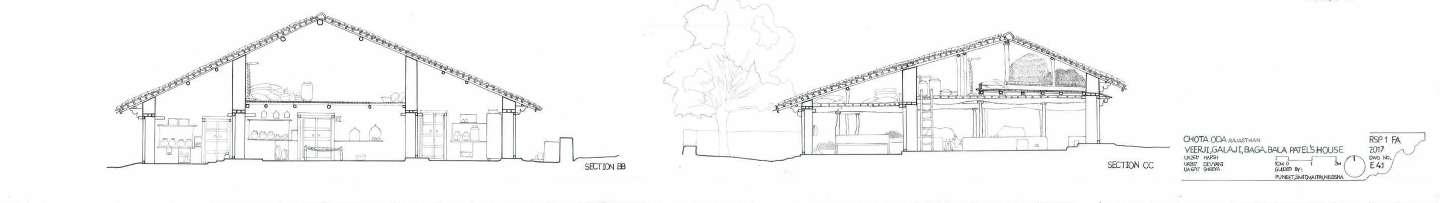

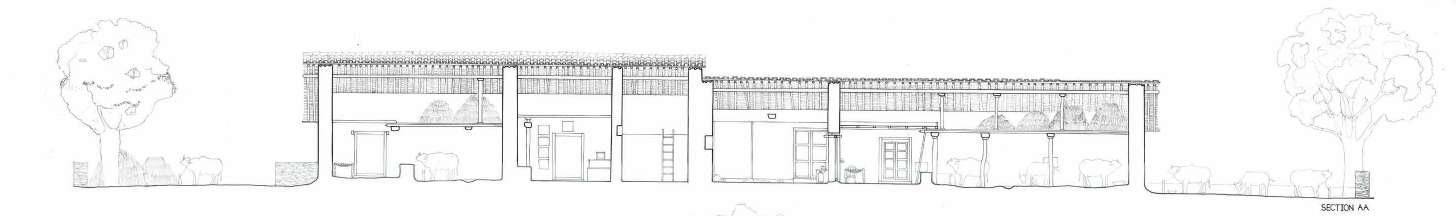

Chota Oda, Rajasthan

The study attempts to introduce students to both -the overall landscape and topographical relationships of the settlement as well as understanding the house form. For the former, a prominent clearing (village square) and one major street (streetscape) are measure drawn to study the characteristics of open spaces between houses, gradients, ground cover, etc.

For the latter, detailed plans, sections and elevations of the houses are drawn with great emphasis on mapping activity and peopleanimals-paraphernalia relationships.

In a major departure from the generic house within and yard or shed for animals outside the situation, here the interior assumes a microcosmic dimension to support living, cooking, storage as well as accommodation of livestock.

A Reflection of my work through “Where do we Stand?” by

Marcel Breuer

Preface

What is simplicity and what is complexity? If simplicity is a thread of wool, then, is complexity a tangled mess of an unkempt ball of wool? If this mess was to be unravelled, wouldn’t it become a simple thread? But then again, isn’t this thread constituted of finer fibres, wound and woven with each other to make this seemingly simple object? Just like the thread and the knot, simplicity and complexity exist and are interwoven with one another; it takes a layering of complexities in order to generate something that may appear to be simple.

while designing the mass housing, I was of the same opinion. I did what seemed to be the simplest approach- get rid of all the problems they had and give them a new, similar slate for them to personalize and regenerate complexities. The output of this sort of an approach led to a formally complex organization, a different one from what already existed; one which was a lot clearer functionally.

Upon reflection, had I taken a more complex approach and intervened surgically in strategically chosen areas, the interventions themselves would’ve seemed simple and small, but underneath the surface would’ve been layers of decisions and processes, both simple and complex. The output may not have exuded clarity functionally, but the identity of the space may have remained.

Reduce, Rationalize, Revolutionize

In his book “Where do we stand?”, Marcel Breuer states that though modern architecture is a many sided complex, ideologically speaking, its aim is simple- to revolutionize, create contrast and generate clarity. When Breuer talks about new architecture trying to revolutionize, the fundamental idea he speaks of here is seeking rationality through objectivity. The only parameters he looks at here to evaluate the ‘containers of men’s domiciles’ (Breuer, 1935) are those which are either functional or possibly programmatic in nature. Simply reducing a work of architecture to its functions may increase its clarity, but eradicating other complexities of the context most certainly cannot make a project simple. In trying to be objective, we remove all subjectivities of the context, and reduce everything to binaries- blacks and whites. A want for rationality makes one become selective about the issues that they are choosing to address.

In some situations, this sort of a ‘rational’ approach may be beneficial in streamlining one’s thought processes. While designing ‘A Place for Wellness, Wellbeing and Mindfulness’, the site that I worked with in Lonavala was almost a tabula rasa. Here, I could afford to choose what Breuer considered to be a rational approach. By using the functional and programmatic requirements to determine a simple method of organizing the plan, I could then layer this with temporal complexities, such as the transient nature of light in the space and openings framing the shifting landscape.

However, while developing a mass housing strategy for migrant workers at Kumbharwada (Dharavi), choosing a rational approach actually ended up eradicating all temporal complexities. What was once a tapestry of materials now got reduced to ‘simple’ standardized housing units, doing away with specificities and a personalized way of building. The layering of complexities was removed and what remained was an imitation of simplicity.

Contrast: The Newer the Better?

Breuer quite rightly talks about a change in our method when it comes to approaching a project. Instead of family traditions and force of habit, we employ scientific principles and logical analysis. He mentions that novelty is a powerful commercial weapon, but as architects, it is our responsibility to create something that is suitable, intrinsically right and as relatively perfect as possible (Breuer, 1935). We are usually of the opinion that newer is better. All processes instantly become more streamlined with newer technologies- a lot simpler in utilitarian terms. In terms of a process,

Breuer defined clarity as the definite expression of the purpose of a building and a sincere expression of its structure. (Breuer, 1935) But can a structure ever sincerely express the complexities of the processes and decisions that went into its making?

In ‘A Place for Wellness, Wellbeing and Mindfulness’, the internal spaces seem quite clear and uninterrupted. One is free to focus on the quality of space, the light, the textures of the materials. It is a space in which Breuer would ‘feel at ease’, which to him, defined a simple building. What one can’t see is the number of elements, materials, members, agencies, decisions… the list goes on. As seen in this example, as well as other examples of modern architecture, as simply as a structure may be expressed, it will never be reflective of the complexity of processes, decisions and involvement of agencies that went into the planning of it. All seemingly simple forms are built on a foundation of complexities.

Clarity: Of the Surface and the Underlying Conclusion Bibliography

As stated before, one does not achieve simplicity simply by ignoring other complexities. Of course, during the Modernist movement, all emphasis and focus was on the functional clarity of a building, reducing it to the core needs. But if one starts removing the very fibres that constitute a thread, they’re going to end up with a weak, much thinner thread, not strong enough to hold itself together, let alone weave a fabric. Can a building then ever truly be considered simple or complex? Perhaps, while trying to fit a project into a box that’s neatly labelled as either ‘simple’ or ‘complex’, it will ultimately end up losing the very simplicities that make it complex, or the very complexities that make it simple. Maybe, a project should be like a cloth. For after all, a cloth seems seamless, simple and utilitarian when viewed from afar, but up close, it is a complex weave of warps, wefts, threads and colours systematically and precisely woven together to create a tapestry. Breuer, M. (1935). Where do we Stand? Architectural Review Smith, K. H. (2012). Introducing Architectural Theory: Debating a Discipline. New York: Routledge.