Pickering; Sam Christmas; Katie Barker;

Point Images; Cory Texter; Larry Pegram; Scott Brelsford; Sammy Sabedra; Dan Stanley; Jonas Hendrix; Manel Rosa; Alex Carbonell; Ryan Quickfall; Scott Toepfer; Death Spray Custom; Co-Built; Dee Johnson; Nick at Fartco; Jim Koch; Manel Portugal; Lucia at 5Special; Todd Marella; Shogo Nakao; Larry Lawrence; Mick Ofield; Fab Biker PR; Prankur Rana; Carl CFM; Cheetah; Dave & Kathy at Flat Trak Fotos; Leftie; Lenny Schuurmans; Egor at Anker; Semen Kuzmin; Kristen Lassen, Scott Hunter, Giselle, Helen & all

American

Track; the DTRA;

who

and

Kristina Fender.

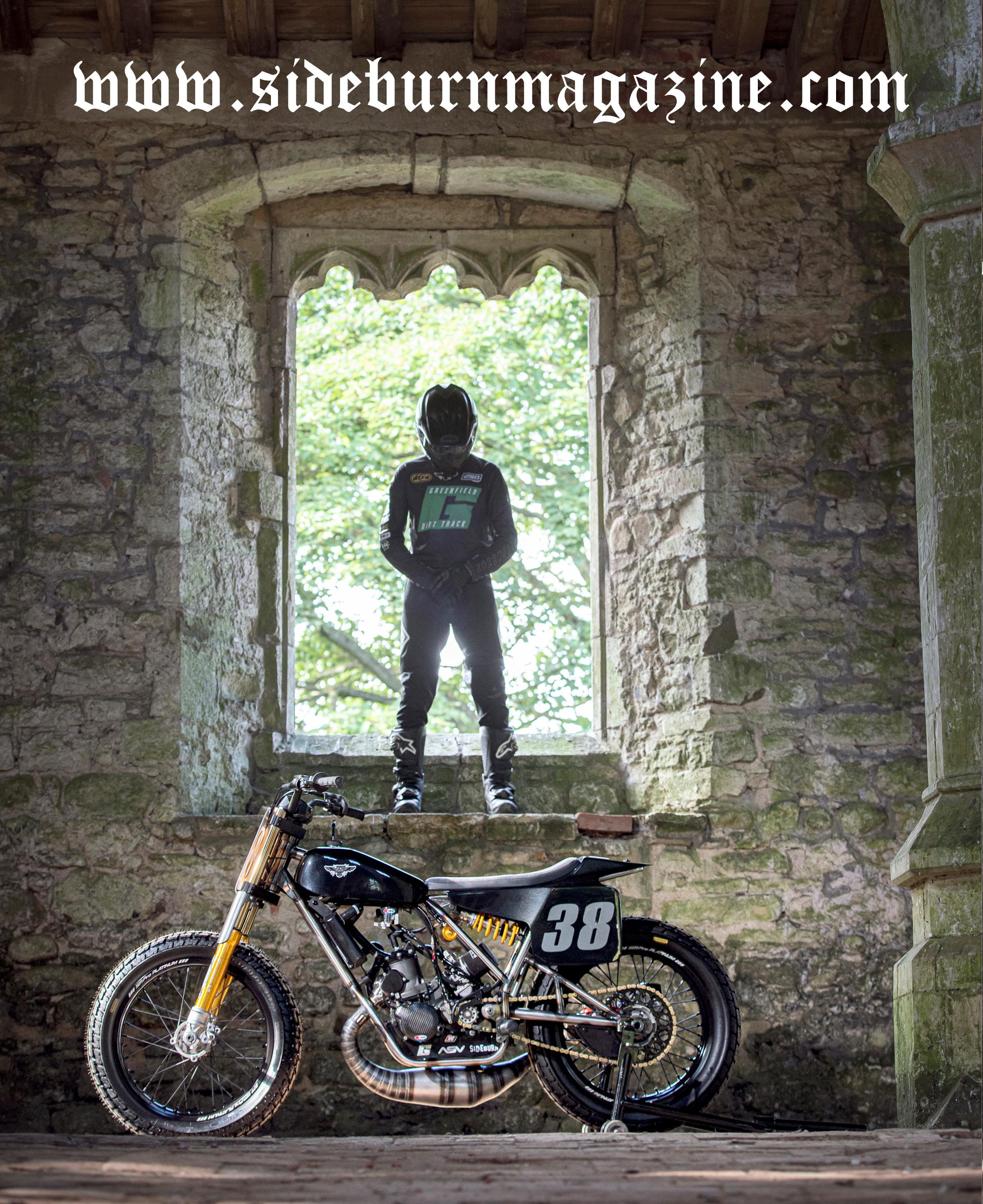

Mutate to survive. American Flat Track emerges into a pandemic-gripped world. See p28 Cover: Survivor 250 SX & George Pickering by Sam Christmas @sideburnmag sideburnmag sideburnmagazine.com SIDEBURN IS THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF AMERICAN FLAT TRACK This issue of Sideburn was created under lockdown conditions thanks to these stars: George

Braking

at

Flat

a thousand thank yous to all our advertisers old

new. Support those

support the scene. This issue is dedicated to

The opinions expressed in Sideburn magazine are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the magazine’s publisher or editors. Sideburn is published four times a year by Inman Ink Ltd Editor: Gary Inman Deputy editor: Mick Phillips Art editor: Kar Lee For advertising/commercial enquiries please email: sideburnmag@gmail.com ©2020 Sideburn magazine None of this magazine can be reproduced without publisher’s consent sideburnmag@gmail.com SIDEBURN 43 will be published in November 2020. To subscribe go to sideburn.bigcartel.com

Made in the USA • sscycle.com • @sscycle • #sscycle Race-ready parts for your Hooligan build

6 GO! At last, 2020 is underway 8 DIVINE. LIGHT. Survivor KTM 250 stroker 20 LARRY PEGRAM SuperTwins wild card and colossal weed farmer 28 AFT VS THE NEW NORMAL Masks and alligator head trophies – Florida welcomes the pros 34 PAYBACK Why a freelance photographer sponsors a privateer racer 38 SX APPEAL Super-classy 1970s Harley two-stroke short tracker 49 CHAMPION KAWASAKI 750 H2 Blueprint of a mythical beast, Kanemoto’s triple 56 LEATHER QUEEN The artistry of D’s Leathers 64 MOTORCYCLES SAVED MY LIFE Mental health check 67 MANUEL PORTUGAL Portfolio of the Portuguese photo pro 76 5 STEPS TO SUDO Stunning Sudo Co-Built Rotax 86 SUPER POWER Russia’s only Trackmaster Triumph twin (plus an oddball IZH stroker) 5 #42 sideburn Regulars 24 C-Tech: Geometry 94 Have Fun!! Japanese Flat Track 97 Schuurmans’ Backflash 98 Project Bike 100 Racewear 103 Sideburn merchandise 104 Death Spray Custom 106 Trophy Queen Illustration: Death Spray Custom

GO!

THE DIFFERENCE SOME white paint and 24 hours make. The rescheduled AFT season got underway on 17 July at Volusia, a track the Grand National Championship had never previously visited. Night one of the double-header took place on a narrow groove, with few overtaking opportunities. For the early sessions of day two, painted lines on the outside of the previous night’s groove forced riders further up the track, widening the racing surface as they laid down more rubber. For the race, the paint was removed, reinstating the inside line. It was one of the ingredients that created a classic Singles race that fans will talk about for months, if not years. As riders pushed ever harder, a fog of excess adrenaline hung in the hot evening air. A red flag led to a fourlap dash that hotly-tipped teenager Dallas Daniels, #32, (battling here with #13 Mischler and #15 Rush) grabbed by 0.02s from Shayna Texter. The 2020 Singles class is totally unpredictable.

7

Photo: Kristen Lassen/ American Flat Track

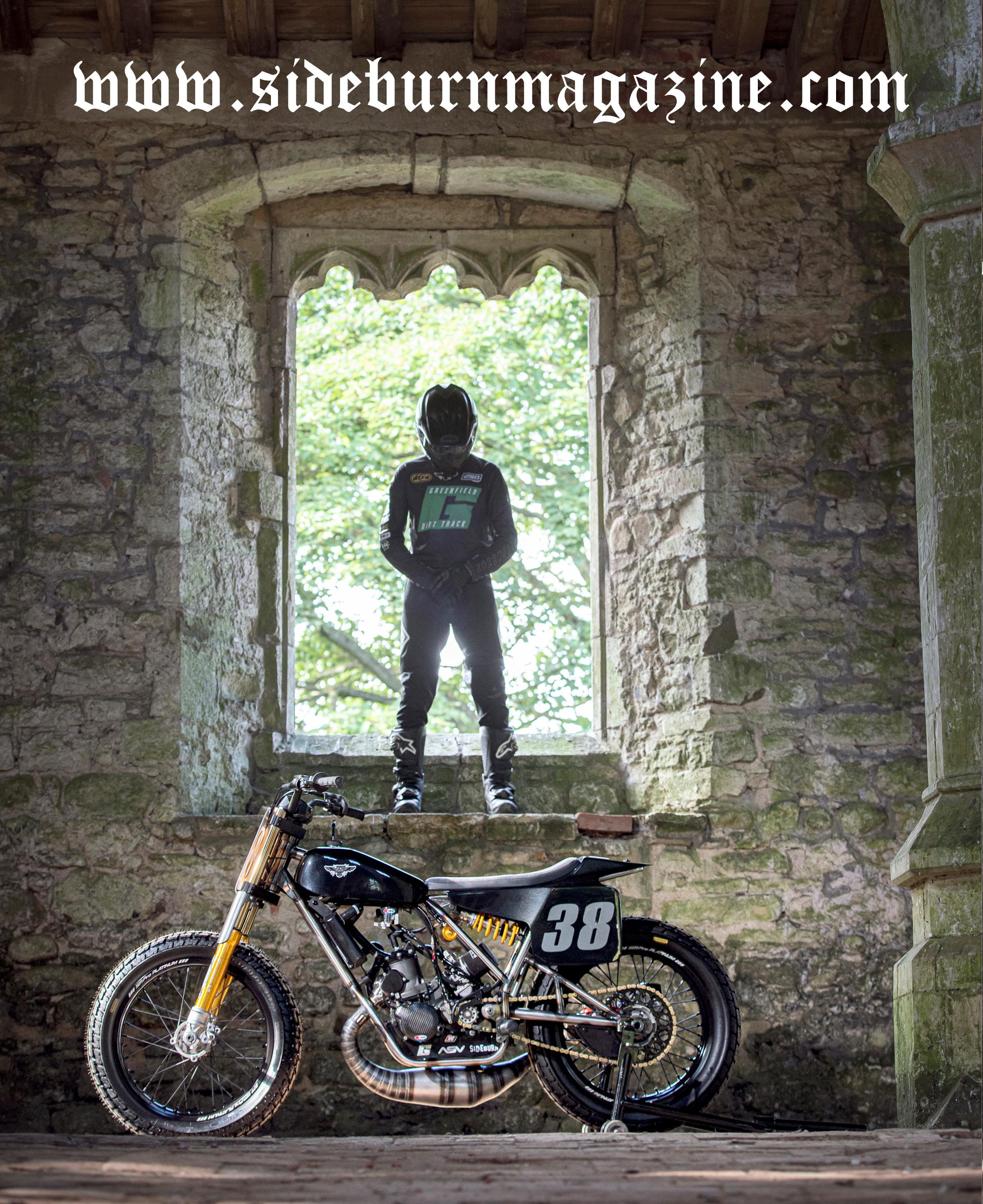

Divine. Light.

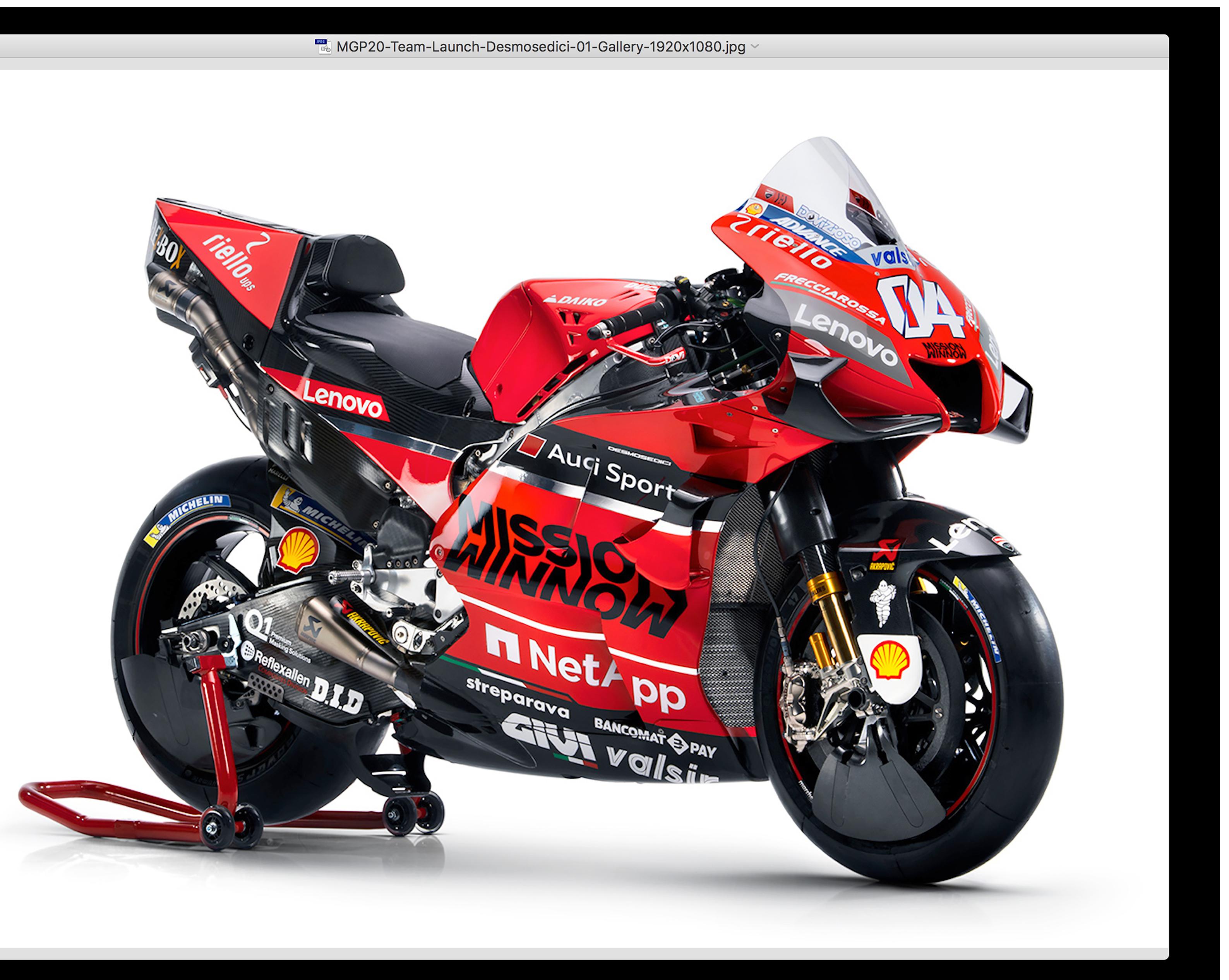

And we mean light. A Brit-built, sub-90kg 250 framer with Pro class 450s in its sights. Time to prey

Words: Gary Inman Photos: Sam Christmas, Braking Point Images (track action)

9 >

‘S

IMPLIFY, THEN ADD lightness.’

That line from Lotus racing supremo Colin Chapman is one of a handful of motorsport quotes that have lodged in my brain, along with ‘See God, then brake’ and ‘They don’t pay me enough to ride that thing’.

When it comes to competitionready vehicles, dirt track motorcycles are as comparatively complex as a cheese sandwich. The rules have stunted development for 60 years. Here’s one example: at the very pinnacle of the sport, American Flat Track’s SuperTwins class, aluminium frames are not allowed. It’s fair to say the sport has simplicity in abundance. There are no aerodynamic winglets, active suspension systems or carbonfibre brakes. That means half of Chapman’s ethos is embedded in the very DNA of the sport. Now to add the lightness.

‘I was baling some hay in the field next to Greenfield Dirt Track when a friend messaged to say he was selling a standard KTM 250 SX,’ says George Pickering, the young farmer who, on his family farm, created the oval that has become the focus of UK dirt track1. ‘I thought it would be fun to do some racing with and, because I’ve raced KTMs in the past, I already had some wheels and suspension set up for a KTM. Let’s give it a go.’

George bought the two-stroke motocrosser in mid-2019. After a couple of practice days, he entered a rare UK race with prize money up for grabs, the DTRA’s Friday night before DirtQuake at Eastbourne on England’s south coast.

‘I managed to take the win! The 250 engine was actually really

good and worked surprisingly well against the field of 450 DTX bikes on the short 275m (300 yard) speedway track,’ says George.

On the drive back north, a few riders stopped at Rye House, another speedway short track. George continues, ‘Me and Mike Hill of Survivor Customs pitted next to each other. He had the custom-made CRF450 framer2 he’d made his own frame for and asked if I wanted to have a go. Of course I did.’ In return, George let Mike ride the 250 twostroke DTX he’d won on a couple of days before.

George has plenty of experience on different race bikes, from 125s and 250s to 650cc singles and hooligan twins. ‘The frame Survivor made handled very well but the punchy 450 carbed engine took some hanging onto after the two-stroke I’d just jumped off. When we got back in the pits Mike said how good the KTM two-stroke motor felt and we joked that we should stick my motor in his chassis. Imagine how light it would be, we thought.’ Eyebrows raised, thoughts lodged, plans germinated.

‘About a month later, a friend of mine was selling a 2016 SX250 engine, carb and wiring loom. It was too good to be true,’ says George. It’s not luck, he puts himself in this position by buying, selling and having a few quid in his pocket to take a punt on a bike for sale and acting quickly. ‘I messaged him straight away, bought it and drove 200 miles up north the next day to give it all to Survivor Customs.’

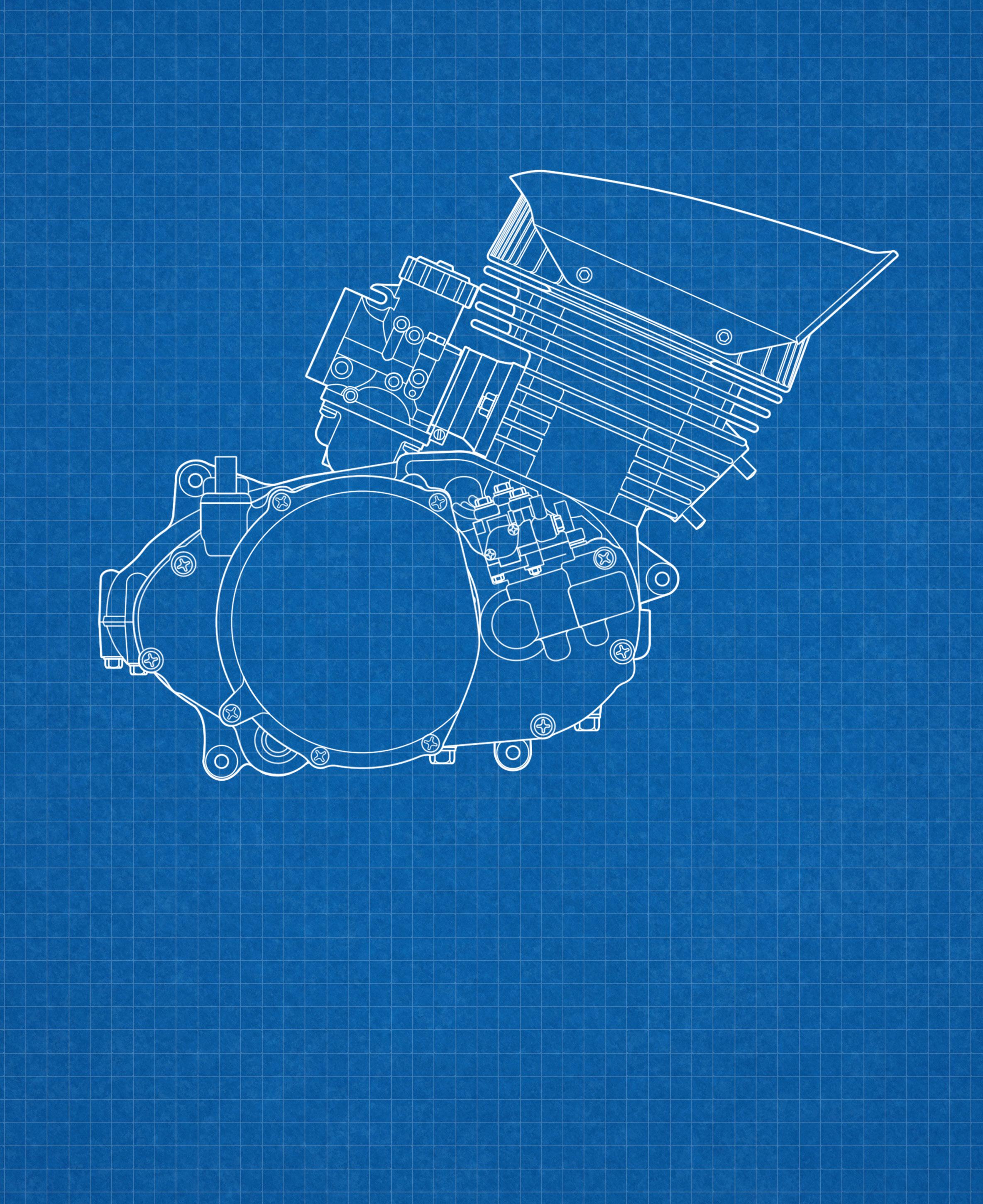

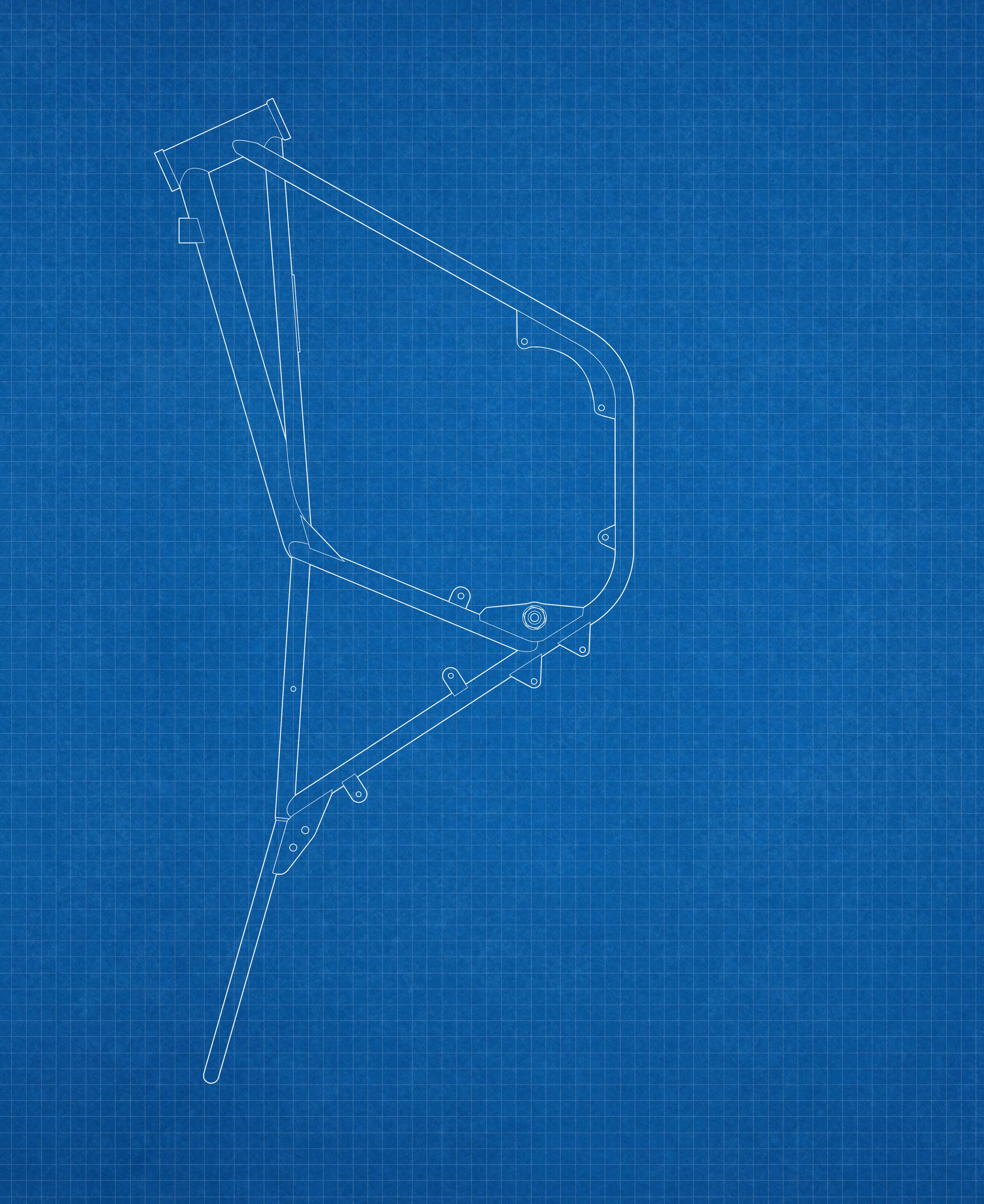

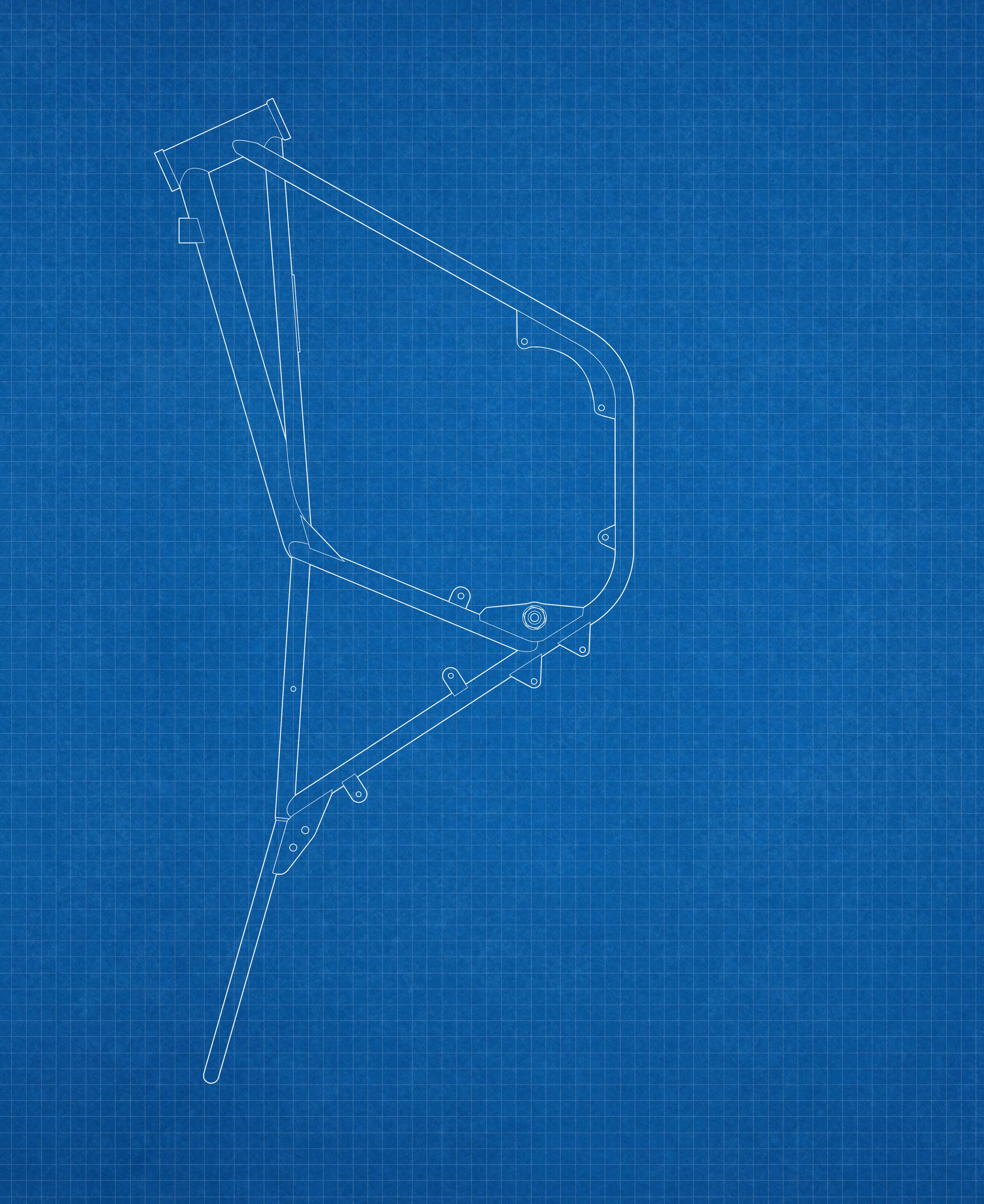

There are a number of widely agreed-upon fundamentals to flat track chassis design. They relate to wheelbase, fork angle and swingarm angle, but even if you stick to those there is plenty of room for interpretation. Survivor’s most recent frames don’t look like any others I’m familiar with. The

Appendix 1. George and his Greenfield track were featured in SB38. George also modelled to help us recreate the famous Ray Weishaar Harley piglet shot for SB40.

>

engine appears closer to the back wheel than with a lot of dirt track framer chassis, leading to a short swingarm and more real estate between the front wheel and the front of the engine. The appearance is exaggerated when a modern, compact, two-stroke motor is fitted.

This frame is made from TIGwelded, 16-gauge, BS4 T45 tubing. This is part of ‘adding lightness’. T45 is seamless manganese steel, used in aerospace applications. Because it’s stronger than mild steel, fabricators can use a thinner wall thickness without compromising strength or rigidity. It also helps that it doesn’t need heat treatment after welding.

‘We went with a steering head angle [rake] of 24.5 degrees,’ says George, ‘and added another inch [25mm] of wheel adjustment in the swingarm, so we could make the wheelbase extra short or extra long. It can be adjusted between 52.5in and 55.5in [1333 – 1410mm]. I also fitted a set of Survivor Customs adjustable offset flat track yokes which can be changed from 40mm to 60mm in 5mm increments3.’

Modern 250 framers are uncommon, because there are very few places pros can race them, so there isn’t a lot of knowledge to rely on or refer to. George used the bike’s suspension to create extra adjustment possibilities. Ben Flick at B&G Motorsport in Silverstone made a length adjuster for the Öhlins TTX rear shock, so the swingarm angle can be quickly adjusted between 4 and 9 degrees4 to suit different track conditions. He also supplied the Öhlins RWU front forks longer than they might need, to give extra adjustment each way in the yokes.

Appendix

2. Featured in SB38. 3. See this issue’s C-Tech to read what difference this makes.

4. The angle the swingarm sits at. The 5-9 degree figure is below horizontal and is the line between the centres of the swingarm pivot and rear wheel spindle. On a swingarm like this you’d place your measuring device on the top of the swingarm. Many smartphones have an angle-measuring app as standard. >

‘Once I picked the bike up it was rideable and looking beautiful. Mike had done far more than I expected, lots of the little time-consuming bits as well. My friend Steve Nicholls and I totally stripped it and sent all the engine components off to Factory Coating in Chesterfield to be powder coated. I opted to clear lacquer the frame to show off the craftsmanship and quality of the welding.’

George wasn’t in the mood for cutting corners. He fitted a KTM PowerParts 300cc kit and renewed the whole bottom end; installed a Rekluse clutch; ordered brand new SM Pro 19in wheels and had JS Performance make custom cooling hoses. Survivor made the tank and seat unit. The tank is a fibreglass cover over an alloy cell. Pro-Carbon and Sudo Cycles carbonfibre parts supply further lightness and a factory racer feel.

‘It was important to me to have such a nice exhaust, because it’s always the main feature of a two-stroke, and I wanted it to look special.’ Two-stroke expansion chamber design is much more complicated than for a four-stroke, because the internal pressures and waves of the exhaust gasses leaving the engine can be used to suck the fresh charge – the fuel and air mix –into the combustion chamber. John Riley of Redspeed Racing, Redcar, more used to making racing kart exhausts, created the beautiful front exhaust system.

So, how light is it? ‘The finished bike has a dry weight of only 89kg,’ says George, still sounding a bit surprised it’s as low as just 196lb. ‘We’re happy with that figure, because the little Honda CRF125s we play around on are 91kg.’

KTM claim a ‘weight without fuel’ of 96kg [212lb] for the stock 2020

250 SX. And George’s bike is 21kg [46lb] less than the kerb weight5 Honda claim for a stock 2020 Honda CRF450 – 110kg [242lb], the kind of bike he’ll be racing against in the DTRA series. For further comparison, the minimum weight for an AFT SuperTwin is 140kg [310lb] and for the singles is 104kg [230lb]. So yes, George’s 89kg 250 is seriously light.

‘This obviously has its pros and cons,’ he explains. ‘The bike is very manoeuvrable and turns in very well and it has so much feel in the middle of the corner. It works well on a loose track, but it’s a real handful on a grooved track with lots of grip. It’s all you can manage to keep the front end down. We used a Honda CRF450 front brake caliper for the rear brake, and this is possibly too sharp for the weight of the bike, it’s something I’m going to have to adjust and make changes to. It’s taken around eight months to build the bike and there’s still a lot of setting up to do as we get more time on the track.’

Even though he’s won titles, built bikes, created the UK’s favourite dirt track from scratch, organised events, run race teams... George still reckons, ‘It’s a mammoth task to have an idea in your head and then transform it into real life.

‘There are too many people to thank for their time helping me with this build, but I think we’ve created a real head turner and I hope once we have it set up it’ll be a weapon on the track.

‘It was a bigger job than I realised when I first thought it was a good idea, but we’ve learned a lot along the way and I’m very pleased with what we’ve built.’

We think the weight was well worth the wait.

Appendix 5. Car and bike manufacturers quote different weights: dry, wet, kerb, shipping... and they’re not standardised. Kerb normally means ready to ride with fuel tank 90% full. Dry can sometimes be stretched to mean without even battery acid.

George on the bike he built, riding the track he created from nothing, in the shirt of the team he runs (all while managing the family farm)

>

A disused 13th century church in the wilds of Lincolnshire was a dream location. We just had to wait for the fetish shoot to wrap up

Always wear a helmet, protective eyewear and clothing and insist your passenger does the same. Ride within the limits of the law and your own abilities. Read and understand your owner’s manual. Never ride under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Copyright © 2020 Indian Motorcycle International, LLC. All rights reserved. BOOK YOUR TEST RIDE INDIANMOTORCYCLE.CO.UK/FIND-A-DEALER @indianmotorcycleuk @indianmotorcycleuk Always wear a helmet, protective eyewear and clothing and insist your passenger does the same. Ride within the limits of the law and your own abilities. Read and understand your owner’s manual. Never ride under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Copyright © 2020 Indian Motorcycle International, LLC. All rights reserved. BOOK YOUR TEST RIDE INDIANMOTORCYCLE.CO.UK/FIND-A-DEALER @indianmotorcycleuk @indianmotorcycleuk

SCRAMBLER STYLING

WITH MODERN PERFORMANCE.

Who? What? When? Why? Where?

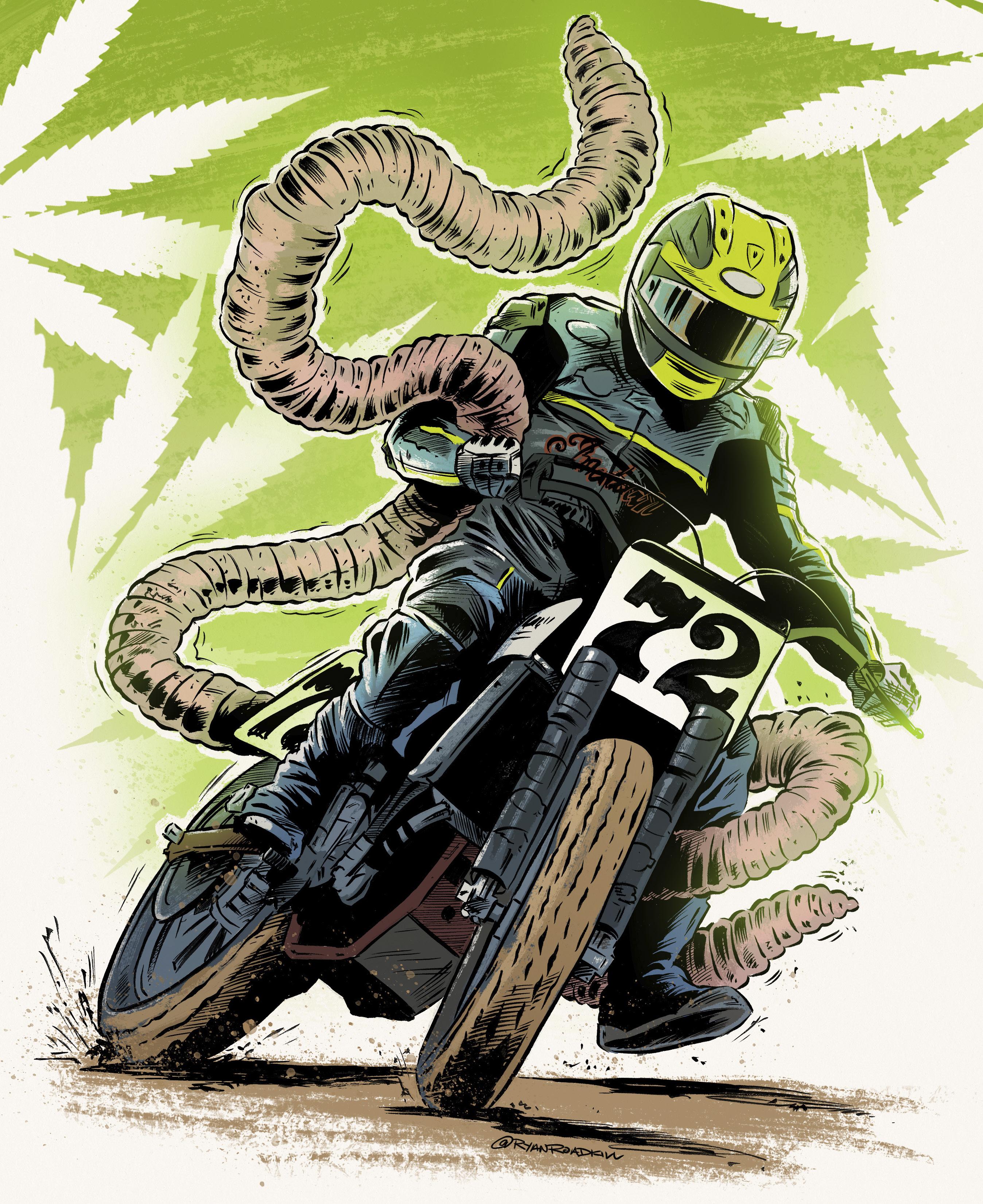

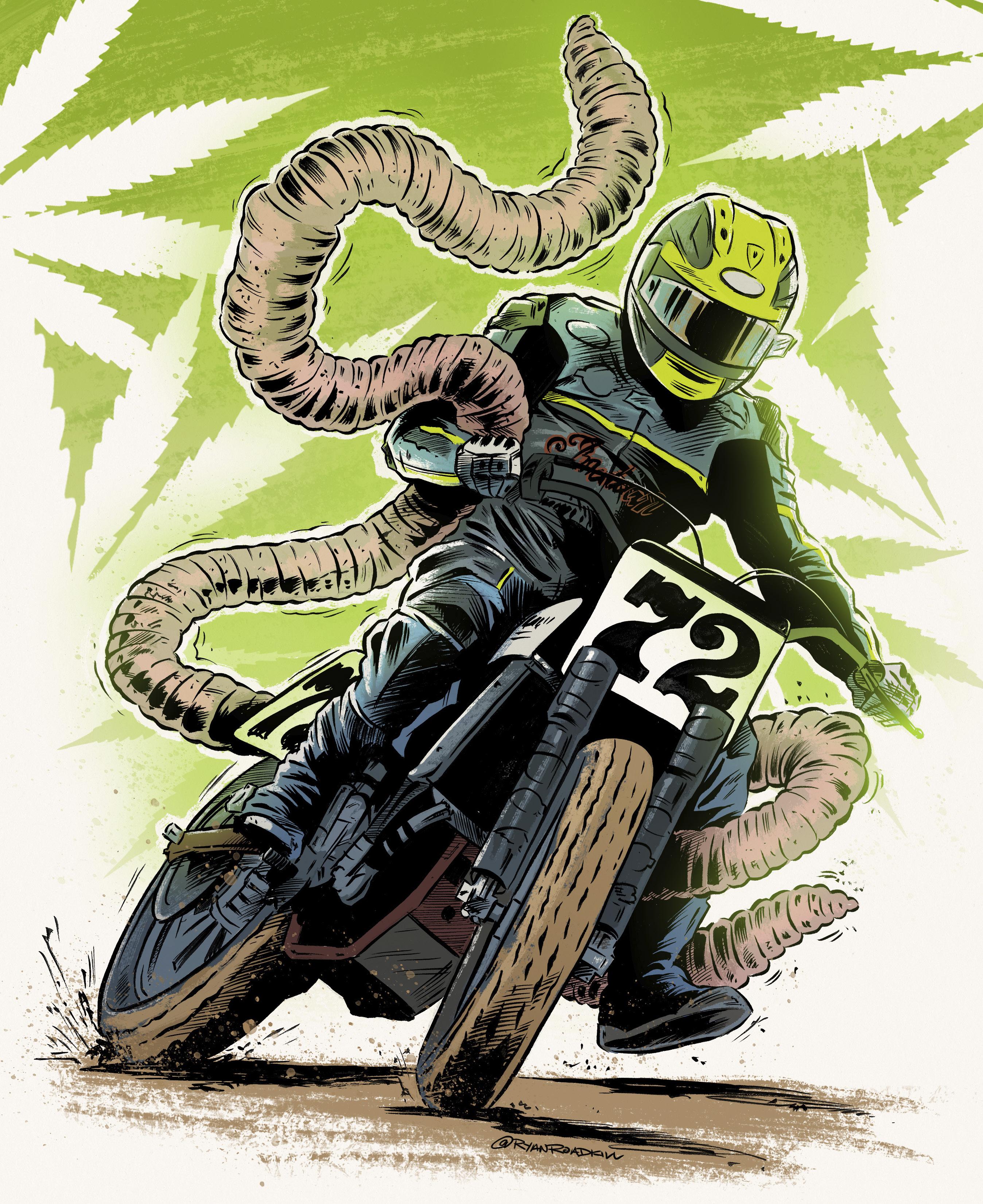

Larry Pegram

Interview: Gary Inman Illustration: Ryan Quickfall

You’ve won AMA dirt track and superbike races, and, at 47, you’re still racing in American Flat Track SuperTwins, but what do you remember of your first race?

I had an Indian 50 that I rode when I was three and when I turned five I got my sister’s Honda MR50. She’s five years older than me. I thought I rode on the ice first, because we live in Ohio and in the winter the lakes freeze up, but my dad said I rode the hare scramble first, through the woods on a closed course. It was me and one other guy in the class and I was on an old, three-speed, two-stroke Honda. I won, because the other guy’s bike broke. I would say from that race until now that’s all I’ve done, race motorcycles, every weekend pretty much. If I wasn’t racing, I was thinking about racing.

Was your family into racing?

Yeah, my grandpa raced, my dad raced professionally. He was a flat track and road race guy back in the 1960s and ’70s. He got tenth in the Daytona 200 once, back in the ’70s, when it was real hard, so he was a very good racer. We would go to the local track called Honda Hills, which was owned by a guy named Dick Klamfoth1. Dick had a dealership there and motocross and flat tracks. I’d ride the motocross track but kept sneaking up on the flat track. Dad had a flat track background, so he said, ‘Hey, do you want to do this?’ And I said, Yeah, I like going fast. So

Appendix

I started racing flat track and I never went back to motocross. Back then, you could race pretty much every weekend and never leave Ohio, though we did. We went to amateur nationals. I just got really good at it. It would be very seldom that I’d get beat and I won the amateur nationals every year. I had the record for the most amateur nationals ever won in AMA history at the time. All I wanted to do was race motorcycles, turn pro and follow in the footsteps of Jay Springsteen.

Where and when did you turn pro?

The day I turned 16, which was the rules back then. I turned pro at Zanesville, Ohio. There were Novice, Junior and Expert classes2, and I won the Novice race on my birthday, racing a Wood Rotax. Ron Wood was sponsoring me then.

Did you always plan to leave flat track for road racing?

I knew I wanted to be a world champion, and I honestly think I had a pretty good opportunity to accomplish that. I was on my way, I’d won the amateur stuff; I was winning dirt track nationals at 17, 18 years old; then went into road racing and immediately did really well, but then got hurt in ’93. That was only my third Superbike race ever, third road race ever, and broke my hip and knee. The hip was what got me because I lost a lot of my range of motion, so I couldn’t hang off the bike and stuff, but, you

know, things happen. So I just gritted my teeth and kept racing. I still won dirt track nationals and Superbike races.

Why did you return to pro flat track?

I raced the X Games [flat track] in 20153. Then Brad Baker got hurt, not when he got paralyzed, but he got hurt the year before. Indian had called me up and I filled in, so it kinda got me back in. Even though I went road racing, flat track was always my love.

You have one of the least flattering nicknames in racing, The Worm, where does that come from?

I’ve got a lot of different stories on that, but the real story is my sister used to call me Worm when I was little, so I used to have it on the butt of my leathers and it kinda stuck.

What’s the most memorable win of your career?

There are two. Winning the Hagerstown Half-Mile in 1991 when I was 18, in my rookie year [as an Expert]. That was my first Grand National win and probably my most memorable. But also, in 2009, winning the AMA Superbike race at Road America. That was with my own team, my own bike, my own crew that I’d put together. I went head-to-head with Matt Mladin4 , who’s the biggest dick on the planet, and beat him, heads up. We passed each other seven times on the white flag lap. To do that with my own team was pretty neat.

1. Three-time Daytona 200 winner, when still held, partly at least, on the beach itself. Klamfoth first won on a Norton in 1949. He died in December 2019, aged 91. 2. At the time, a rider turned pro at 16 as a Novice. They had to earn enough points to progress to Junior, and then Expert. This has been replaced by AFT Singles and Twins classes. 3. Pegram was rider/team manager for Erik Buell’s Hero-backed EBR World Superbike team in 2015 until the company folded. Larry was the first rider to score points in WSB on an American OEM bike, as a wild card at Laguna Seca, 2014. 4. Australian Superbike racer, seven-time AMA Superbike champ between 1999 and 2009. Also raced the Cagiva 500 in MotoGP for one season in 1993. Global dick status unconfirmed at time of going to press.

>

21

What’s the best bike you’ve ever raced?

The Skip Eaken5 Honda RS750 I won Hagerstown on. They were all ex-Shobert bikes. When Honda pulled out of AMA flat track, Skip ended up getting the bikes from Honda and started his own team with Mike Sponseller as sponsor. Either that bike or my Ducati [1098R] in 2009, that I won on at Road America. My bikes that season were Troy Bayliss’s factory World Superbikes from the year before.

And what’s the worst bike you ever raced?

A Suzuki TL1000 superbike. The first year I rode for Yoshimura, they had me on a GSX-R750 and the next year, they said, ‘You’re riding this new bike, it’s a TL1000 V-twin.’ I thought, Oh, that’ll be good. And it was not, it had that rotary damper system6. I lived, but barely.

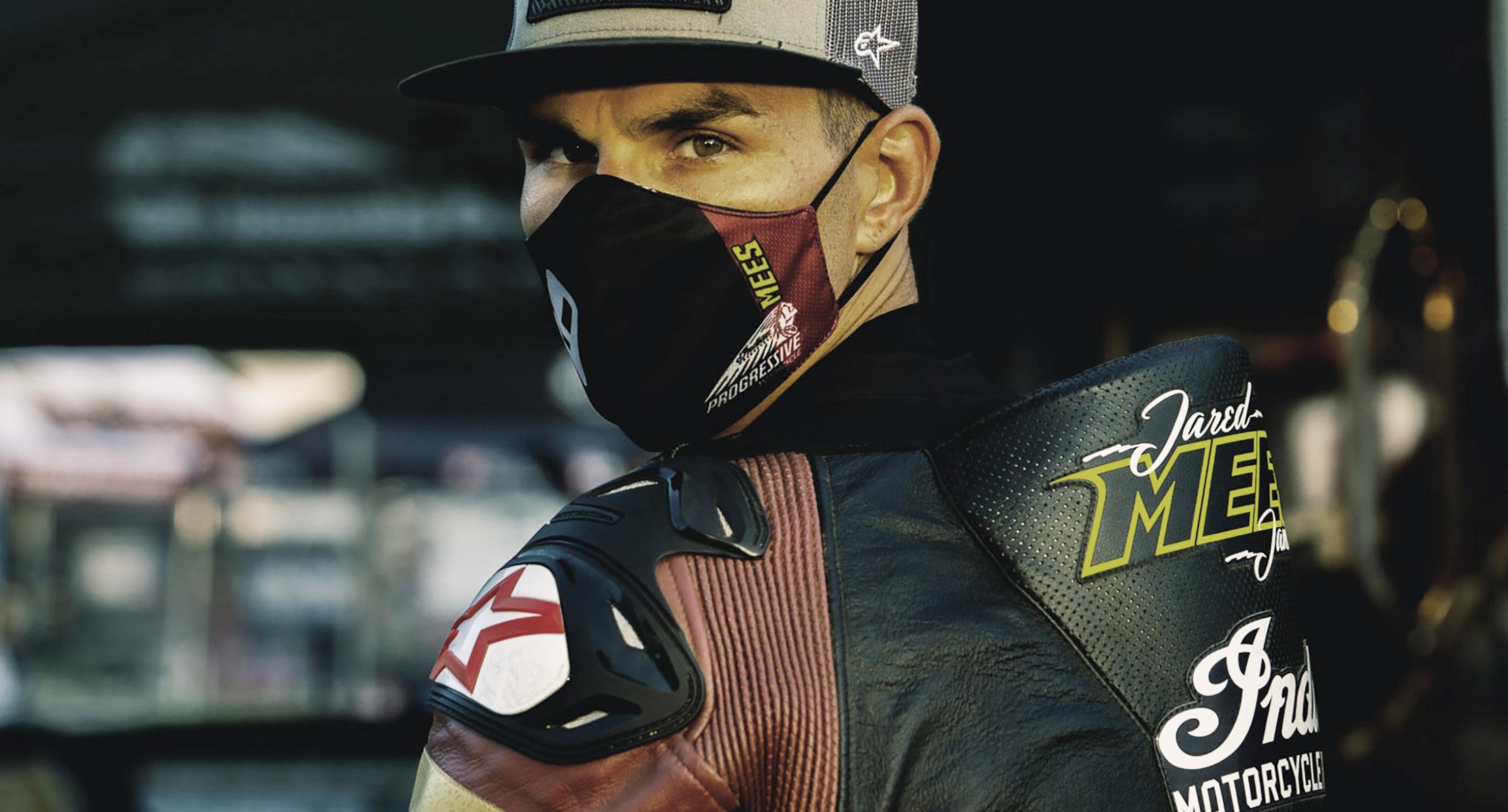

Are you still racing as an AFT wild card in 2020?

Yeah. The bike is Indian’s and the guys from S&S prep it for us. David Lloyd7 has been a friend for long time and we show up and work on it at the racetrack and we kind of prep it between races sometimes, get it cleaned up. It’s a good bike, but it doesn’t have the effort behind it that their full factory bikes do. It’s basically a stock Indian, which is a pretty good advertisement, because we won a couple of heat races [in 2019] on it. I just couldn’t keep up the pace for 25 laps.

Why is a 25-lap main a struggle?

After all, you were fifth at the 2019 Texas Half-Mile.

It’s down to two things. Number one, I just got beat, I’m not afraid to say that. The other thing is, I’m 47 years old and I’m just not able to train the way I should, ’cause I’m sitting in this weed

Appendix

Back to the bikes for the final question: what do you think of the SuperTwins9 evolution of AFT?

I think they’ve done a phenomenal job. Five years ago, nobody was talking about flat track and now people are. It’s hard as a racer, team owner or manufacturer to step back and look at the big picture, but I think that’s what AFT has done. I’ve always said that you need to be a show that has a race involved, not a race that you’re trying to make into a show. You’ve got to make people want to watch the individuals and that’s what they’re trying to do. NASCAR could have an event where they’re all racing tractors and they’d get 30,000 people turn up, so it’s not about the vehicle that they’re racing.

business all day long, trying to figure out how to make [enough for] my kids to go to college. I try to race just to have fun, but my real goal is to try to win a race or two, that would be really cool.

Wait. Weed farm?

I own one of the largest marijuana cultivation facilities in Ohio8. We’re about a year into the programme and have a 53,000sq.ft facility growing cannabis, and three dispensaries as well. I was completely illiterate to what the whole cannabis industry was about because I just believed the ‘Just Say No’ type stuff. Then I got into it and realised that there’s a ton of medical issues it helps with better than any conventional medicine. Our median customer is 55 years old and it relieves their pain without them being in a fog all day, like they would be with opiates. You take the correct doses and you don’t get high. I actually became a real advocate for it.

You gotta make the racing close. In my opinion, if a guy wins eight races in a row, turn them around backwards on the back row for the main event, you know, make a show out of it. If you’re in tenth place at the halfway and you win the race, you get five extra points.

A monster truck show and WWE wrestling can fill 100,000-seat stadiums and people say, well, flat track racing is way better than that. It is to me. It is to you, but obviously it’s not, or we’d have a 100,000 people at our races. How do we make this into a show? You need rivalries. You gotta have two guys that don’t like each other. You don’t even need anybody else in the race. You know what I mean? You’ve got to have two guys and everybody gets on one side or the other, and it’s no different than football or baseball or anything else. We know the Springfield Mile is the greatest sports spectacle we’ve ever seen. You’ll have 120 lead changes in 25 laps with 15 different guys, but we don’t have 100,000 people standing around to watch it. So we’ve got to figure out how to think outside of the box.

5. Racer, factory Honda flat track tuner and privateer team owner/tuner. Won multiple dirt track and superbike titles as a tuner. Eaken died in 2012. 6. Instead of a regular piston-and-spring-style rear suspension unit, Suzuki fitted their Superbike with a rotary damper, more like those used for closing doors. It was universally derided and dropped from production shortly after release. 7. Of Lloyd Brothers Racing, most wellknown for campainging Ducatis in AFT. 8. Pegram, with no previous agricultural experience, saw an opportunity after the collapse of EBR. He can only sell his crop in Ohio, where marijuana is legal for medical, not recreational use. 9. For the 2020 season, American Flat Track’s premier class has been renamed SuperTwins. The main difference is that all entrants will make the final, qualifying is simply to determine grid position. This brings AFT in line with major motorcycle race series like MotoGP and World Superbike.

MAX28 EXPANDABLE BACKPACK Utilising Kriega’s groundbreaking Quadloc-Lite™ harness, combined with high-tech construction materials to meet the demands of the modern-day urban rider. • 100% WATERPROOF ROLL-TOP LAPTOP POCKET • FOLD-DOWN COMPARTMENT WITH ORGANISER POCKETS • MAIN SECTION EXPANDS TO CARRY A FULL-FACE HELMET KRIEGA 10 YEAR GUARANTEEKRIEGA.COM #RIDEKRIEGA NEWphoto credit @gorm_moto

Flat Track Geometry

I HAVE NEVER been a great math student. At school, I didn’t want to know all the inbetween steps on how to solve a problem, I just wanted to get the right answer and move on to the next task, or a subject I was better suited for, like physical education or recess. I relate this outlook to some of the things I know when it comes to setting up the geometry of a flat track race bike. I don’t always understand the science behind why a certain change to the front end of the motorcycle reacts the way it does, but I know what works for certain racetracks and I can simplify it enough to explain it.

CLAMP DOWN

One major area of geometry adjustment is the triple clamps [aka fork yokes]. Many flat track race bikes are fitted with adjustable triple clamps that allow racers to change fork offset relatively simply. Offset is the distance between the centre of the steering stem and the centre of the fork legs. Lots of companies make adjustable triples clamps. Some are altered by changing the spacer plates in the clamps, but more commonly by changing the eccentric inserts that hold the steering stem. Changing the offset alters the way the bike handles and steers going into the corner, and, more importantly in my opinion, how the bike keeps its wheels in line when you get on the throttle. Adjusting the offset changes the front end trail without altering the rake. Whole books have been written about motorcycle geometry with all sorts of graphs and all that stuff, but I’m trying to make it simple for you, so I’ll leave it to that statement.

GET INTO OFFSET

Every twin-cylinder flat track motorcycle that I know, and I’ve ridden pretty much all of them, starts with 60mm offset. This is ‘zero offset’ and the eccentrics are usually marked with a zero on the top. If you’re happy with how the bike is behaving, leave the eccentrics at the ‘zero’ setting of 60mm. If you feel forced to make an improvement, here’s my advice. When adjusting the triple clamps, I usually use 2mm increments, because only changing it 1mm isn’t enough to feel a real difference. Putting in a 2mm insert with the number forward changes the offset to 62mm. Putting the same insert

in backwards changes the offset to 58mm.

There are two eccentrics and you have to pop one in both the top and bottom triple clamps.

I’ve run as far out as 65mm and as far back as 55mm, depending on the bike I’m riding and track conditions. Adjustment is simple, but sometimes it takes two people if they’re clamps where the front end has to come off the bike while changing the eccentrics.

STEERING AND STABILITY

Some mechanics have a different theory on what the feel of the bike should be when adjusting the triple clamps, but I’m describing my seat-of-the-pants experience. Generally speaking, on cushion racetracks, where the bike is steered with the throttle, I like to have my front end pushed out with a 62mm offset. This helps keep the wheels in line when I’m accelerating out of the turn and gives me less chance of highsiding off the corner. The bike seems to drive off the corner better, because I’m not chasing the rear end. One negative of running with increased offset is the bike doesn’t turn as sharply, but on a cushion you steer with the rear wheel while twisting the throttle, so that’s less important. If I ran a 55mm offset on a cushion track, I would most likely be fishtailing everywhere. It might look cool in photos, but it’s quite a bit slower, because I won’t be driving forward off the corner if the tail end of the bike is dancing around. Sometimes this varies when riding a street bike, but another negative I’ve found from having your front end pushed out is less stability down the straightaway. On some mile tracks that are rough or with high winds, this might cause the bike to wobble and the bars to shake a bit, or tank slap. This term reminds me of a pretty sweet podcast available for free on iTunes called Tank Slappin’! [Co-hosted by our man Cory and, originally former GNC number 1, Jake Johnson, not Sammy Sabedra. Widely available and well worth a listen. Ed]

On clay tracks, and surfaces that have some grip, I typically reduce the offset. Remember when I said pushing the eccentrics out on a cushion track helps keep the wheels in line when I pick up the throttle? This is where things are bit confusing, because I feel like the wheels stay in line best entering a corner with eccentrics

pulled back, running a 58mm or less offset. So, on cushion or loose tracks we typically increase the offset to 62mm or more. On the clay or hard-packed tracks we’ll reduce it to 58mm or less.

FRAME FACTOR

Every motorcycle handles differently, even with the same offsets. The handling of my Harley-Davidson XR750 feels way different with 58mm offset than when we run the same offset on the G&G Racing Yamaha MT-07 I won the 2019 AFT Production Twins championship with. Basically, every time you ride a new bike, you have to start from scratch and find what works best from testing and experience on the bike. Frame ergonomics have a lot to do with the different feel in offsets, as well as where the motor sits in the frame, the wheelbase and so on.

DTX 450s have leading-axle forks, so the geometry is quite a bit different. I can’t ride a DTX 450 with negative offsets, it has to be stock or increased offset. Those bikes already dance around through the corners, because they’re designed to hit jumps and bang ruts, so pulling back the offset makes them almost impossible for me to ride.

RAISE ’EM OR DROP ’EM

Another way of adjusting the front end is to effectively change the length of your forks by raising or lowering them through the clamps. Doing this affects both the rake and trail. Raising the forks through the clamps, so the top of the fork legs is closer to the handlebars, gives similar results to reducing the offset, so going from 60mm to 58mm or less.

Confusing? Too many options? Welcome to my life as a motorcycle racer. I would add that if you’re making wholesale adjustments on race day, you’re most likely riding the struggle bus and your mechanic is probably saying, ‘Let’s try it. What do we have to lose at this point?’ A good day at the track is maybe a tyre pressure adjustment and 1-2 teeth on the gearing.

THANKS to long-time mechanic Brent Armbruster who has tuned for guys like Jared Mees, Brandon Robinson and Jake Johnson; Bob Weiss of Weiss Racing.

25

You’re chasing the perfect set-up with your fancy adjustable triple clamps, but what do they do? AFT champion Cory ‘C-Tex’ Texter is here to explain

Illustration: Prankur Rana

C-TECH

©2020 H-D or its affiliates. HARLEY-DAVIDSON,

HARLEY, H-D,

and the

Bar

and

Shield

Logo are among the trademarks of H-D U.S.A., LLC.

Iron out your soul.

The IRON 883™ is stripped down, blacked out and ready for the streets. Learn more at H-D.com. It’s time to ride.

Ryan Varnes The Rider

aft vs

the new normal

The 2020 American Flat Track season finally got underway in mid-July. With the paddock in lockdown, we relied on insider Sammy Sabedra to take the sport’s temperature

Words: Sammy

Photos:

Sabedra

Sammy Sabedra,

Scott

Hunter, Kristen

Lassen

Brian Willis The Team Principal

Sammy Sabedra

Sammy has been embedded in flat track since he could balance on two wheels. Now he is a mechanic for AFT Production Twins contender Ryan Varnes and co-host with Cory Texter of the Tankslappin’ podcast

Kevin Varnes The Mechanic

Kevin Varnes The Mechanic

29 >

FTER WHAT FELT like an eternity of waiting, we were finally on our way back to Florida for the opening two rounds of the American Flat Track series at Volusia Speedway Park. We’d been in Florida – Daytona to be exact – back in March, when the original season opener was cancelled with just 24 hours to go. It felt almost unbelievable to be heading to a race again, 290 days since the last AFT round.

We left our Pennsylvania race shop at 6am for the 15-hour drive. Here in the States, local governments can step in at a moment’s notice and shut things down fast, so we had doubts if the event would even take place due to the recent spike in coronavirus outbreaks. A few hours down the road we spotted another team, heading south and, just like that, things felt normal again. Horns honked and social media posts were tagged as we drafted past each other like we were on the Springfield Mile’s straightaway.

(top left) Varnes junior and senior discuss set-up; (far left) Socially distanced crowd on a sweltering evening; (left) Cory Texter, Production Twins number one, said he was happy to be racing again, but was also nervous of the possibility of infection and didn’t take chances; (above) Varnes, Texter, Rispoli, Armstrong make the front row

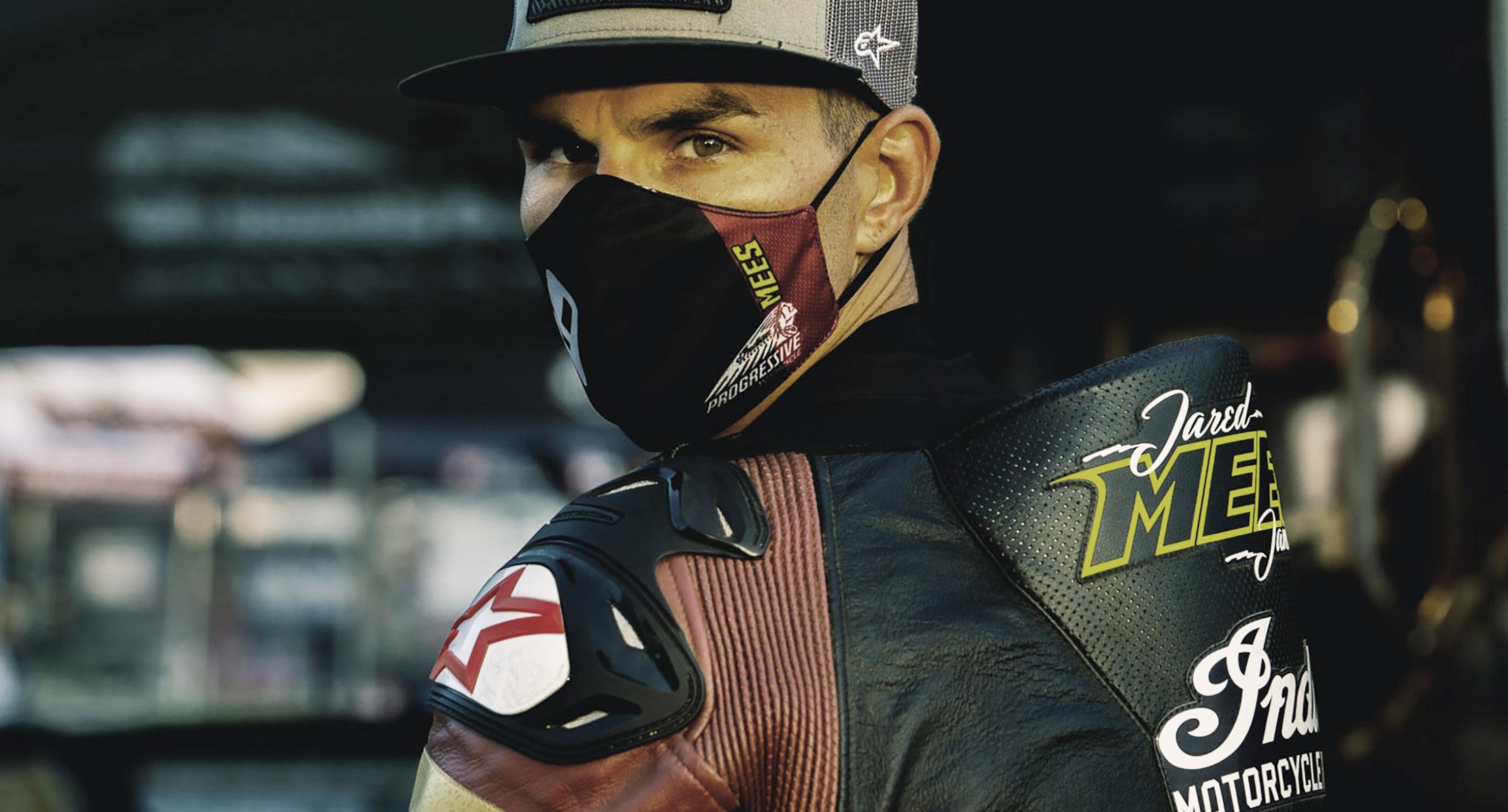

(left) New season, new control tyre and longer, timed races add a chance for race strategy to make a difference; No one uses Kawasakis in the SuperTwins class, but they can still win in Production Twins. Varnes uses Big A frames; (bottom) There is new normal and there is just normal – Mees winning races is the latter. He won both nights; (bottom left) Varnes lining up Rispoli on the Harley for a lastlap smash and grab

>

By the time we arrived in town to start the weekend double-header, emails were arriving from AFT with new health and safety regulations and protocols. The new process was more on a par with an international border crossing than the usual smile and simple credential check it usually took to enter a race facility.

Traditionally, we would arrive at the track by 8am for a night event, but in this new era teams were given orders to arrive in a specific slot to avoid everyone showing up at the same time. The Ryan Varnes Racing Production Twins team was slated to arrive at 1.15 in the afternoon. After being cleared from the initial arrival zone, we navigated through a series of three additional checkpoints. No one in the vehicle was allowed to set foot outside through the entire process. Safety personnel checked our temperatures at the first stop. The last two checkpoints were for further health evaluations and credential scans. After clearing all the checkpoints, we were finally permitted to enter the facility. The AFT crew did a great job with the whole entry process.

Once inside the gates, the general vibe in the paddock was far from the usual social event we’re accustomed to. Teams were encouraged to keep social interaction to a minimum and race fans would not be permitted to enter the paddock at any time, meaning the popular pit walks, prior to the day’s main event, were off the schedule. Interacting with the fans is usually one of my favourite parts of an event, but while they were missed it was nice not to have any outside distractions. In another effort to help maintain social distancing, the paddock layout for the weekend was split into three distinctive sections for each class – SuperTwins, Production Twins and Singles – with additional space between each team. Another big change for the weekend was the use of video links for mandatory rider and crew briefings by AFT operations.

than making a few fine-tune adjustments to both our primary and back-up motorcycles, our test day went extremely well. By day’s end, the team knew Ryan would be tough to beat come race time, 24 hours later.

Race day, and months of preparation would be put to the test. Our efforts as a team would now be measured by race results. As one of two team mechanics, my job is to make the rider feel as comfortable as possible on the motorcycle so he can ride to his limits. At this level, it is already a given that all riders have a very high level of riding talent. Short of writing a book, it would be hard to sum up the amount of hard work and dedication it takes to be competitive at any level in this series.

I raced in Florida and all I got was a pickled ’gator head nailed to a plank of wood

On night one of the double-header, the team made all the right decisions. We gave Ryan the best motorcycle possible and he went out and did his job perfectly, making a last-lap outside pass for the win. When it all comes together for a team, the feeling of victory is like no other. Perhaps the greatest reward a rider can give his mechanic is a wave to hop on the back of the motorcycle for a victorylap celebration. And that’s what I got on that Friday night. It’s a feeling I wish everyone could experience at least once in their life. I felt on top of the world waving that chequered flag, then seeing our rider standing on top of the podium.

Our race weekend began with the first official test day of the year. Ryan’s mandatory skeleton crew was made up of team principal Brian Willis, mechanics Kevin Varnes (Ryan’s dad, who was racing the Bultaco Astro Cup support race, too) and me. Although Volusia has never hosted a national, it’s a track we’re all very familiar with, because there are races there in the runup to the regular Daytona season openers. Thanks to the combined experience the team has at this fast, half-mile oval, we had a pretty good idea of what to expect. Other

As good as some nights are, others can be the complete opposite. Night two was a rough one for the team. We were once again on pace and fighting for second [behind Cory Texter] when, with just a few laps to go, Ryan coasted to stop a few feet from the very same spot where he’d stood on top of the podium the night before. The cause: a broken intake valve. To add insult to injury, Ryan’s dad, Kevin, [himself a former national number] would also suffer mechanical problems while leading the Bultaco Astro Cup race on the last lap. He still had a big enough lead to coast to a third-place finish.

Leaving the track and thinking about the weekend on the drive home, I was happy. It felt good to get back to racing. Even though we had one bad night, the weekend was still a success for us and the sport. The American Flat Track crew proved they could deal with just about anything thrown at them in a time of huge uncertainty. They did a great job with track prep and the level of professionalism within the paddock made it clear it was a world class event. I can’t wait until the next one.

MOTORCYCLE GEAR ENGINEERED BY RIDERS FOR UK INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: WWW.DPC-DISTRIBUTION.COM | +44 (0)870 122 0214 PANDOMOTO.COM @PANDOMOTO

Payback

Sideburn contributor Scott Toepfer explains his move into sponsorship

Photo: Kristen Lassen/American Flat Track

EVERYONE

LOVES AN underdog. In motorsport, the privateer racer is the ultimate example. Going up against the better-funded and corporate factories, the privateer stands quietly and proud.

Somewhere between my final crash racing my Champion Triumph [featured in SB38] and the announcement of the AFT SuperTwins class, I decided I wanted to support dirt track racers. I’d never amount to much aboard a bike, nor am I able to turn wrenches well enough to fill a crew member’s role, so sponsorship came to mind. A little funding for tyres or fuel, a couple of stickers and an exuberant ‘Good luck this weekend!’ seemed like a decent start to a simple programme. Thus, SGT Racing was born.

I don’t sell roofing, nor do I have a logistics monolith, but my professional skill set is in photography and video production. Riders don’t just need money, they also need the means to help attract bigger sponsors so that they can make the next race and the next season. My goal with SGT Racing (SGT are my initials by the way) would be to serve the riders in two ways: traditional monetary sponsorship and a media package of photos and video I would create.

Now, which rider to support... The idea from the outset was to focus on a rider or two that I’m inspired by (we artsy types love to be ‘inspired’) and see if my sponsorship programme would be of interest. This was a much easier choice due to the creation of the AFT SuperTwins class. Knowing I wanted to work specifically with a privateer racer, and the field of riders for the season being more or less decided before the season began, I immediately landed on Jeffrey Carver.

I’d met Jeffrey, photographed him during at least two or three races, and seen him whoop on the famed Wood Rotax at Willow Springs, but we weren’t anything more than passing acquaintances. I’d seen him ride, and win, and take a chance at going it alone in SuperTwins against the better-funded outfits. That was all I needed to reach out.

Carver was nothing but classy and cool, and despite the humble beginnings of my first foray into sponsorship support, he has been patient with me. Just to be clear, I take photographs for a living, which means there isn’t always a lot of extra cash floating around at any given point in time, so the SGT Racing fund will have a humble beginning. If I was going to put money directly into any corner of the competitive, two-wheeled sporting world, it would be for the privateer dirt track racer. I owe a lot of my work to the motorcycle industry, and if I’m going to give back, it’s going to be to the industry that has helped to keep my family fed, and my head clear.

Visibility

SGT Racing could be a vanity project, but who wouldn’t get a buzz from seeing their ‘company’ on the grid?

35

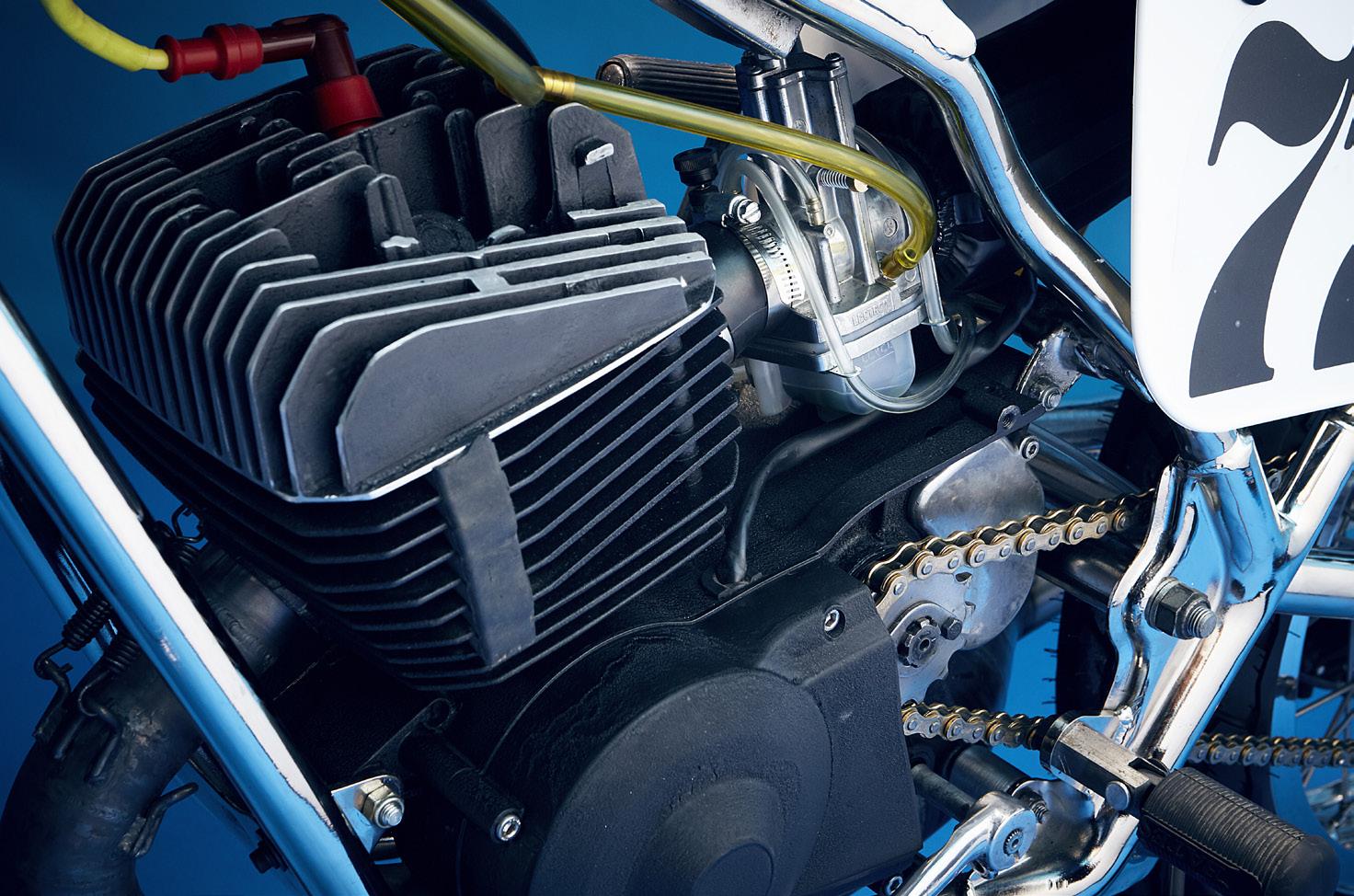

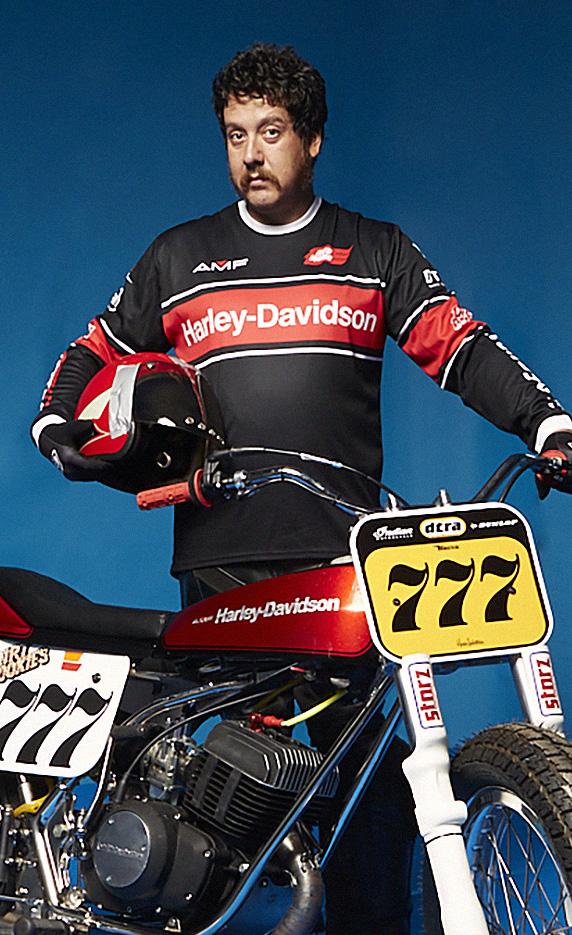

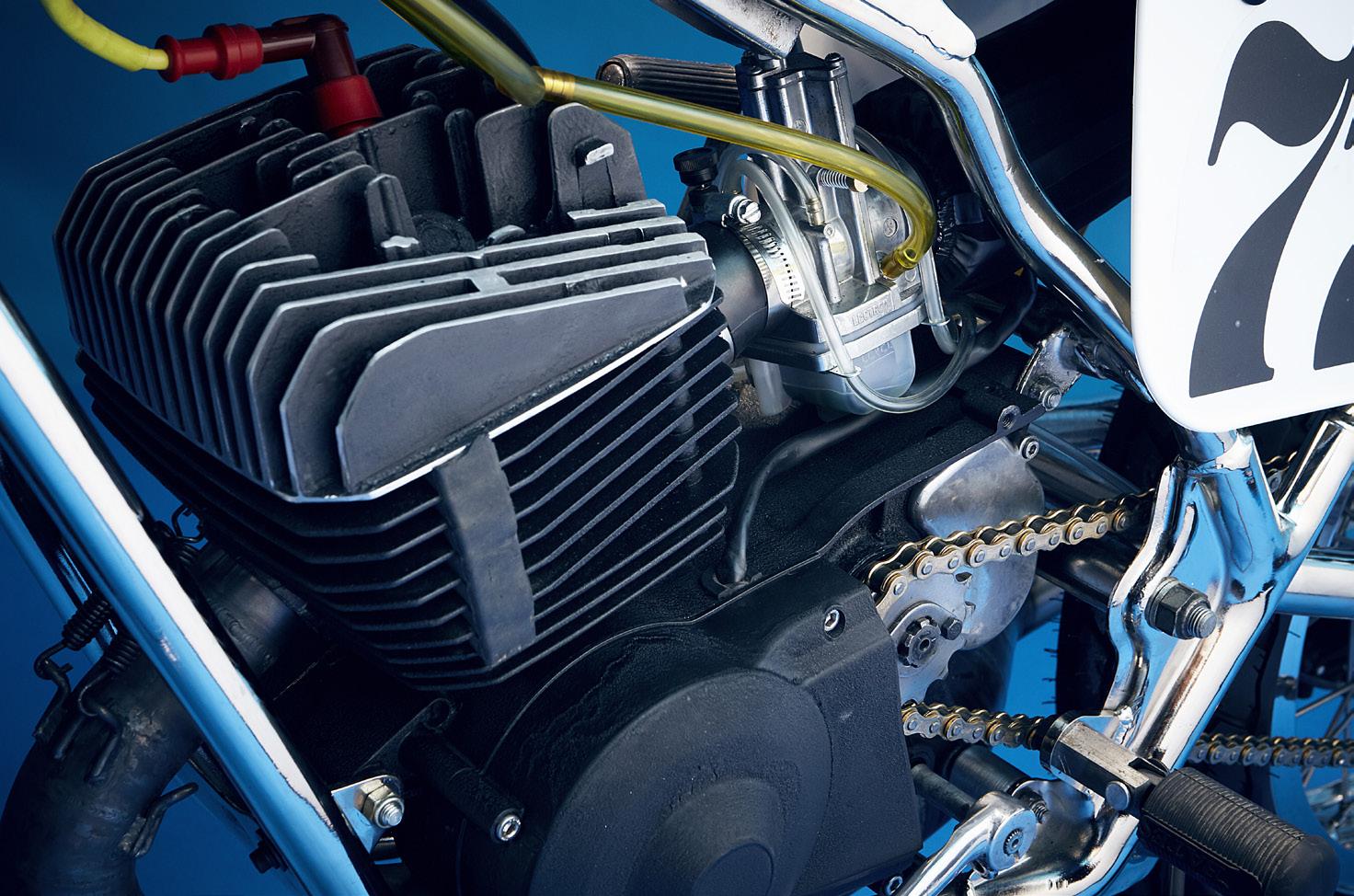

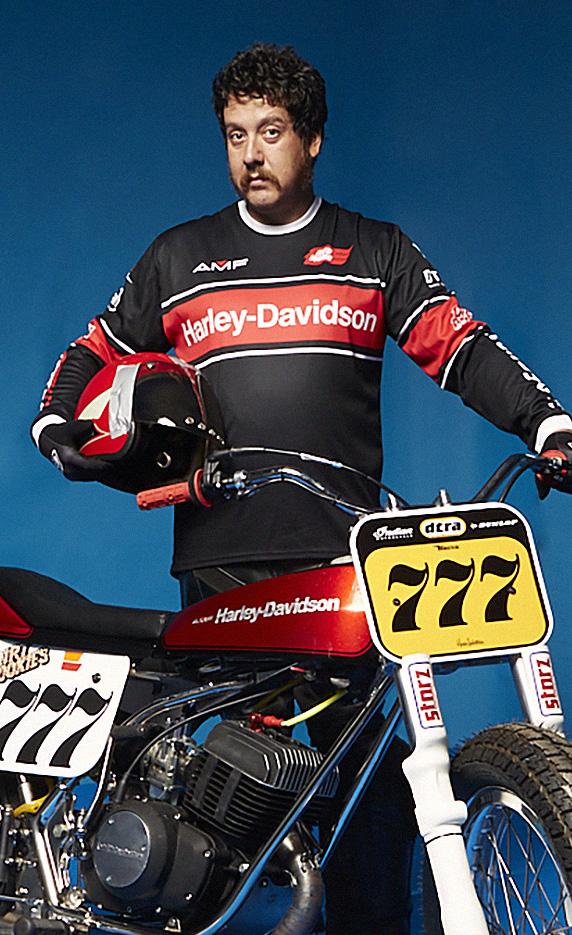

SX APPEAL

ARE YOU READY for a long story? OK. When

I lived in Amsterdam, back in 2002, I went to a family gathering at my uncle’s house. While mooching in the shed I found a 1974 Suzuki TS250. He’d bought it from American oil rig contractors when he worked in Yemen and brought it back to the Netherlands in ’79 or ’80. When he got it back he realised it had two bullets lodged in the forks where it had been shot. My uncle said he hadn’t started it for a couple of years, but we put some gas and oil in it, gave it a couple of kicks and... tadaaaa! It started! My uncle decided to give me the bike and I’ve had it ever since, even though it’s been stolen, then found again, five times in Amsterdam.

Once, I went to get parts for it from a big vintage motorcycle and car show and found a similar bike to mine, but it was all black and with Harley-Davidson on the tank. The price tag was pretty high, they were asking about €7-8000 ($8-9000 at current exchange rates) for what I

found out was an SX-250. I wanted one, and eventually found a rolling chassis with paperwork and slowly started to find all the original parts to rebuild the bike.

While accumulating the parts, often having to order them by fax using the exact part numbers from an old guy in America, I started to acquire extra engines, a second frame with papers, more tanks…

Then life changed course when I met a beautiful lady while working in Barcelona and decided, in 2007, to move to Spain with all the bikes and my dog. The TS250 came and the two Harley frames; three Kawasaki Zeds; a Honda XL500S; 1961 Vespa GS150… I finally finished the Harley SX-250 at the back of our terrace in the middle of Barcelona. Then I met Ferran Mas1, who asked if he could do some pics of the bike for a classic bike magazine. Since then, a full decade ago, the Harley has been pretty much unridden and stored in my workshop.

By 2009-10 I’d become busy with La Corona Motorcycles2 in Barcelona – four guys, including me. We’d built

Jonas Hendrix is a Mexican-born, Argentinian-Dutch guy living in Spain. This is his complex story of building a Harley-Davidson SX-250 race bike. Strap in!

Words: Jonas Hendrix Photos: Manel Rosa (studio), Alex Carbonell (action)

Appendix 1. Ferran Mas, amateur flat track racer, precision rider for TV and film and builder of ‘brand new’ Bultaco Astros, as seen in SB41. 2. One of the many bike builders, inspired by the Wrenchmonkees, that sprung up at the time.

39 >

five or six bikes and done mods for clients, more as a hobby. Then when Wheels and Waves started we all went crazy and got motivated about rebuilding and modifying bikes. The next Wheels and Waves introduced the El Rollo flat track race and I got my first taste of the dirt oval. Then I went to the Noyes3 family flat track school with a group of friends and that was it, I was hooked.

I modified my Honda XL500S and was invited to join Dirt Rookies, a group of Spanish flat track riders on modified bikes. Then I built a Yamaha XS650 with a Co-Built frame. I’d fly to England and rent bikes to race. I bought a Sunday minibike too. Like I say, I was really bitten by the bug.

Now it was time to make all the leftover Harley SX-250 parts into a flat track project. I had a frame; two spare engine blocks; two sets of wheels… I got in touch with Brandon at Ancient Warriors4 who was selling some used flat track parts, and bought his Ceriani GP35 forks, A&A triple clamps and two hubs. I used the front hub on the Harley and the rear on my XS650. I sent the hubs to Jerry of Cheney Engineering in Iowa. He serviced them, supplied new, quick-release rear hub nuts with a 12in rear disc and a few rear sprockets. It was nice to discover that someone still knew the offsets and measurements of the original 250 Harleys. Jerry told me he had done quite a lot of Harley 250 modifications, even frames, back in the ’80s. The hubs were laced with new-old-stock 40-hole Akront/Morad alloy rims, then fitted with Dunlop DT3 tyres that I’d bought from the Cardus Brothers of Rocco’s Ranch, based in Barcelona.

Once all the parts were gathered, my friend Xarly at Vintage Addiction helped me get the frame ready for nickel plating. He’s built some outstanding flat track bikes in the

Appendix 3. Spanish-based American Kenny Noyes was instrumental in growing Spain’s

flat track scene and involved with Marc Marquez’s

Superprestigio, where Noyes was a podium finisher. He was also a Superbike

racer

and

was seriously injured in a testing crash in

2015. 4. Flat track Instagram feed: @ancientwarriors

> >

(clockwise from above) Why the long face? Jonas designed the shoot to copy Harley ads of the 1970s, including moody blue steel expressions; Lectron carb and nickel plating; Period Red Wing shocks and modern Brembo caliper, yum yum

‘Aesthetically, I wanted to use the same Staracer seat and tank that they used on some versions of the Harley DT-250’

>

last few years. We cleaned the frame, welded new tabs for the number plates and exhaust, then rebuilt the engine – not once or twice, but four times – because I was still mixing original Italian Aermacchi parts with Cagiva ones I had5. Now the engine is 100% Harley-Davidson from 1975 and we managed to make a back-up engine with the Cagiva parts in it .

Xarly fine-tuned the engine and covered the crankshaft holes with nylon. We balanced all three crankshafts I had, polished the cylinders and installed a

decompressor in the second sparkplug hole. I discovered old racers are really good at answering questions that you post on forums and Facebook groups.

Aesthetically, I wanted to use the same Staracer seat and tank that they used on some versions of the H-D DT-2506 and, funnily enough, I had the tank of my XS650 that had started to rot from the inside from the effects of modern gasoline. I had seen Dimitri Coste would always drain his tank after a race, but I didn’t see why I should do it on mine. I’ve learned my lesson. The tank was

ruined, so we cut the bottom out of it to use as a cover for a new alloy tank that Xarly made. Kilian Ramirez did an amazing job with the paint, but I’ve already upset him because I really love stickers.

Now, thanks to Covid-19, before I return to England to race with the DTRA I have time to practise and get used to riding this 250 two-stroke with a decompressor that I can’t get on with yet. I also want a gear shifter on the right, like the factory bikes had.

It’s been a long journey, so I can wait a few months more.

drought

Appendix 5. In the 1960s, Harley bought into Aermacchi to fast track into road racing. In the 1970s, they were in a long

of short track wins, losing out to European and Japanese two-strokes, so they began using Aermacchi 250 two-strokes to compete in motocross and the AMA Grand National Championship, to score points at the short tracks. Cagiva bought Aermacchi from Harley in 1978. 6. Harley-badged 125, 175 and 250cc Aermacchis made up the the SX range and there were SST road versions. The motocross-spec bikes were MX-250, while the factory short track racers, ridden by Springsteen and Randy Goss among others, were given the DT prefix.

THE GOOD OLD DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN

Desert racing is a wildly enigmatic sport generally associated with the Fast, Rich or Dumb. You just gotta figure out which one you are. The endurance required is the long-format sort. It’s not the skills that win Supercross that gets one through the harsh terrain encountered in this kind of racing, it’s the thousands of micro-decisions that happen over hours and hours of riding that makes the difference. This sport was built on the backs of hearty individuals who did their best work hundreds of miles away from other humans. You’ve got to love it unconditionally, because it does not love you back. The desert can smell arrogance miles away and takes crafty pride in humbling the most talented riders, no matter their previous success or accomplishments in other arenas.

As tough as it may sound, the Biltwell 100 will be one of the easier races in the Southern California desert for 2021. Our goal is simple: make offroad racing fun again. Through the years, bigger, faster and better-funded teams tend to eclipse the underdog, blue-collar people who exist at the core of off-road racing. Those high-end teams can fight for television coverage and sponsorship contracts– we’ll help you out when you snap your chain in a sand wash, or have a beer with you around the campfire after the race. We’re here for the good times, not the lap times. Did we mention camping and spectating is totally free? Or that there’s a party and BBQ on Saturday night? Anyway, you are invited!

RIDGECREST, CA / APRIL 10-11 2021

information as things evolve:

More

www.biltwell100.com & @biltwell off-road race ridgecrest, cal. off-road race ridgecrest, cal. off-road race ridgecrest, cal. 2021 off-road race ridgecrest, cal.

MIGHTY MO R M I G H T Y M O S H O P . C O M We are MightyMo and so are you. Dedicated to the Greater Moto Good. MIGHTY MO R M I G H T Y M O S H O P . C O M We are MightyMo and so are you. Dedicated to the Greater Moto Good.

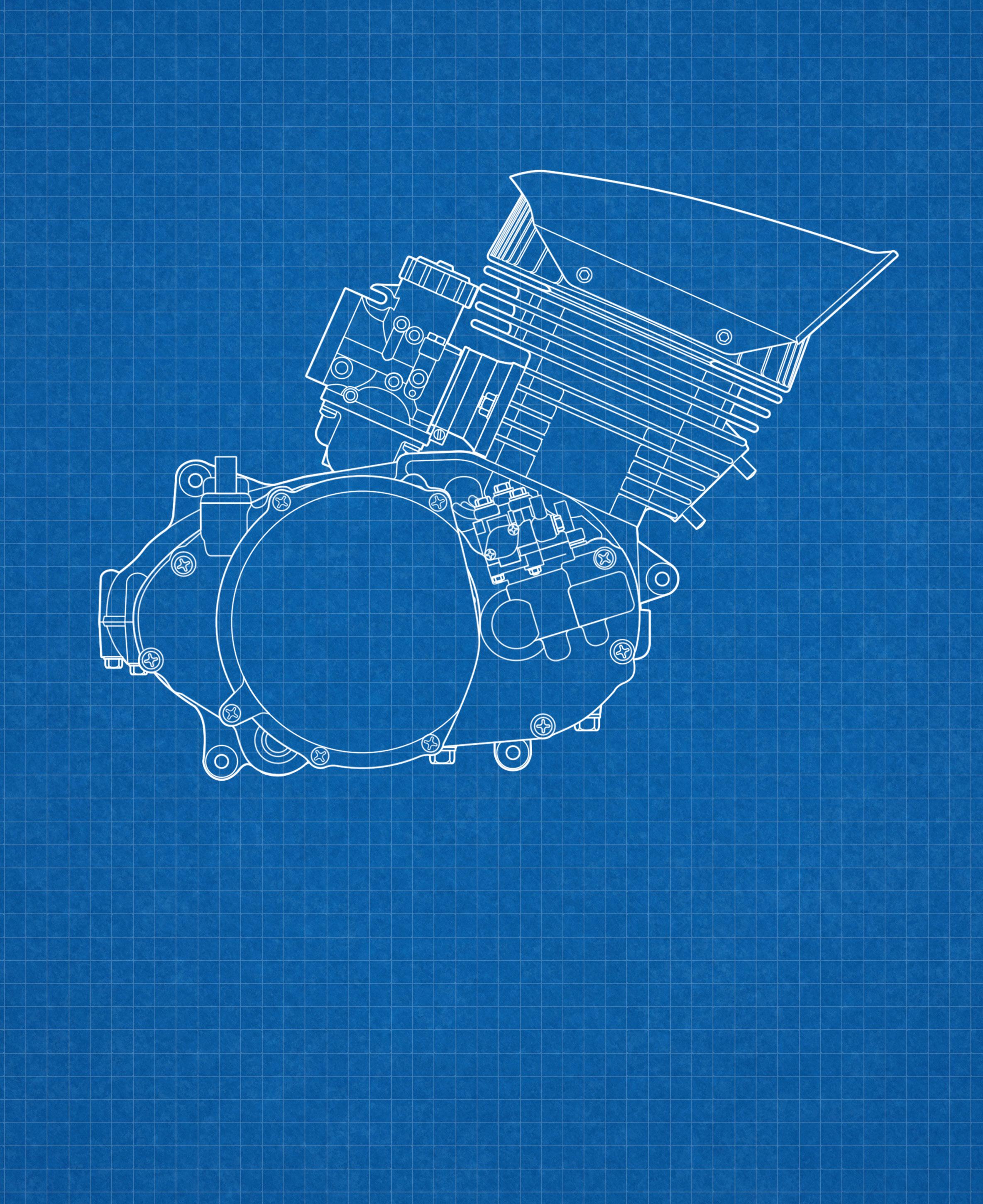

Words: Gary Inman Illustrations: Mick Ofield 49 > The ‘other’ 750cc multi-cylinder two-stroke that screamed in and rattled the the mid-’70s AMA flat track hegemony 1/3 ENGINE 750cc SIDEBURN #42 2020 CHAMPION KAWASAKI H2R

Kanemoto made the scoop for the head to help cool the middle cylinder, always the first to seize 2/3 SIDE ELEVATION 750cc SIDEBURN #42 2020 CHAMPION KAWASAKI H2R

THERE HASN’T BEEN much written about this bike, and a lot of what has been posted seems to be wrong. That’s the opinion of the rider who won on it, Scott Brelsford. For a handful of races over two seasons, Japanese 750cc twostroke framers shook pro flat track till its teeth came loose. Kenny Roberts’ win at the Indy Mile on the yellow and black Champion-framed Yamaha TZ700 was an emphatic exclamation mark that ended the era of the big strokers when it had barely started. The establishment, those with a vested interest in American and British bikes, banned two-strokes from dirt track competition with, looking back, few very good reasons.

‘Kenny sided with [Harley], saying, “They don’t pay me enough to ride this thing,” like he was Superman,’ says Brelsford. ‘But there were other guys who could ride them if they had them, but only a few guys did, and they didn’t have the set-up or special tyres that Kenny had.’ What gives Brelsford the confidence to offer this iconoclastic opinion? By the time of Roberts’ now-famous quote, Scott had already won a big mile race on a 750 two-stroke at Stockton, Ca. Plus he was in the same Indianapolis race as Roberts. ‘I was on the front row, I’d won the heat race, I thought I was going to win that thing, but I blew up the first lap. Then Kenny wins it from the last row.’

The Stockton Mile that Brelsford won wasn’t a national, it was a regional championship race. ‘That’s why people didn’t know I’d won a mile race on the Kawasaki before Kenny Roberts won Indianapolis,’ says the younger brother of Mark Brelsford, the 1972 Grand National champion. Still, that Stockton race was

>

packed with talent and former champs. ‘Dave Aldana, Mert Lawwill, Rex Beauchamp, Gene Romero, a lot of the top guys. Kenny Roberts wasn’t there, he was testing the road racer in Ontario, I think. But I won the race in his hometown.’

Brelsford had raced smaller Champion-framed twostrokes as a Novice, so he got along well with the Doug Schwerma-built chassis that tuner Erv Kanemoto1 built his Kawasaki flat tracker around. ‘I was familiar with the geometry, it was pretty much the same. [Champion Yamaha 250s] were pretty easy to ride, and the Kawasaki was similar, just with a bigger engine. It didn’t get the traction I would have liked, but it was ridable.’

The Californian was 1973 AMA Rookie of the Year, but had fallen out with Harley and their racing director, Dick O’Brien, over a fateful trip to New Zealand to race factory Harleys without O’Brien’s permission 2 . With few options left to him, Brelsford agreed to race the Kawasaki.

‘When I was on the Kawasaki, I planned to get vengeance on the Harleys. I was committed, I hung it out, but the thing just kept blowing up.’

The engines were ex-Gary Nixon H2R road race triples, says Brelsford. ‘Gary Nixon rode the [dirt track] bike before I did. He rode it at San Jose, but he didn’t make the programme 3. He was afraid to shift

championships] but they were planning to get the water-cooled Kawasaki, the KR750, and that’s what I wanted for the road races the next year.’

While things didn’t pan out, Nixon and Kanemoto moving to Suzuki, Brelsford claims the honour of being the first two-stroke to make a mile national main event, when he qualified through the semi for Golden Gate Fields, Albany, California.

‘I could’ve won the race, the first I rode on it, if I didn’t suck sand through the carburettors. It was my fault. We had to have nine filters [for the day] and I put three on that hadn’t been prepped right.’ The win at Stockton, in the regional race, came shortly after.

‘The tyres, back in 1975, weren’t great. Dunlop didn’t have the big new tyre they came out with for 1976, that was quite a bit wider and deeper cut, but Erv found a 4.50 Carlisle tyre for Stockton. I didn’t even know they had a 19in Carlisle that big, so that might have helped me get in the winner’s circle. The front tyre was a Pirelli, they worked really good. Stockton was a sandy surface, not that deep, but I had to try to keep the bike as up and down as possible, I couldn’t really lay it over. I wanted to keep as much tyre on the track as possible.

‘After I won the Stockton race, Erv hired Don Castro, who had ridden for him back in the ’60s as a novice. I didn’t like the idea I was going to have a teammate after I just won a race, but Erv didn’t know where I was at. I figured I could out-ride anybody on that thing. I don’t think Castro ever made the programme in five attempts, but those things weren’t easy to ride.’

After Roberts won the national at Indy, the AMA’s competition committee moved to neutralise the twostroke threat, and it came as a shock to Brelsford.

it and you had to shift to make them work, you had to use that five-speed and downshift for the corner. He’d broken his leg real bad on a three-cylinder Triumph in 1969, by missing a shift [at Santa Rosa], and it pretty much ruined his dirt track career.’

Being young, skilled and driven to beat the factories meant Brelsford was ideal for the Kawasaki, but, he remembers, ‘Everybody was scared of the thing. It was pretty scary to ride a [two-stroke] on a mile or a half-mile. I never got to ride a half-mile because Erv didn’t have time to get the thing ready. We didn’t have the money to develop it or test it.’

Brelsford had his eyes on a Japanese 750 for the road races that made up the Grand National Championship at the time 4 . ‘Erv was working with Nixon [the pair had won the 1973 road race

‘All the old-timers were afraid to even think about riding one of them. They didn’t want their stuff to become obsolete. They were trying to protect their legacies. The guys on the competition committee who chose to ban them were all protecting their own deal. [The two-strokes] had so much potential. Soon there wouldn’t have been any four-strokes in the main event. The young guys coming up were used to riding two-strokes as Novices. My brother, and all the guys before him, had [grown up] riding Harley-Davidson Sprints on short tracks. I was pretty much ruined. I really didn’t think they’d do it.’

Instead, the Champion Kawasaki H2R has become an almost mythical oddity, a flash in the pan never given a chance to at least try to fulfil its potential. The last word on it has to go to Scott Brelsford. ‘It was fun to ride the thing, but it was a challenge.’

the 250 and 500 Rothmans Hondas. The list of racers

races, where he’d be given good start

worked with

Rayborn died after crashing a borrowed

famous Harley racer

and heat races to the semis and main event, the day’s final

the Grand National Championship on dirt tracks and road

‘All the old-timers were afraid to even think about riding one of them. They didn’t want their stuff to become obsolete’

Appendix 1. Kanemoto is most famous for masterminding Freddie Spencer’s GP championship titles on

he’s

is a who’s who. 2. Brelsford shipped a Harley race bike to New Zealand to compete in

money just for turning up. At one of the races, in December 1973 at Pukekohe, the

Cal

race bike. 3. ‘Making the programme’ is flat track jargon for progressing from qualifying

race. 4. Through the 1970s and into the ’80s, riders earned points towards

races. Specialists could score well, but all-rounders had a much better chance.

www.facebook.com/roadracemotorcyclesSimple but effective doublecradle frame by Doug ‘Champion’ Schwerma 3/3 FRAME N/A SIDEBURN #42 2020 CHAMPION KAWASAKI H2R

Brelsford already in the tuck off the turn in a battle with the Shell Racing Yamaha XS650 of Hank Scott

‘135, 137mph, in fifth gear, and the thing was still pulling pretty good’

Scott Brelsford gives us a seat-of-the-pants recollection of racing the Kawasaki 750 triple Words: Gary Inman Photo: Gary Van Voorhis

‘You couldn’t gear the Kawasaki to run in one gear [like you would with a four-stroke]. You needed the lower gear to come off the corner, because the Kawasaki didn’t have the torque of the XR750s.’

The bike had very similar horsepower to an XR, says Brelsford, about 90bhp in 1975, but the Kawasaki was much lighter at 290lb (130kg) according to some sources, compared to around 310lb (141kg) for an XR.

‘I had to be straight up and down when I changed gear, I didn’t want to shift when I was leaned over. And you didn’t want to make a mistake downshifting or you’re

dead. In a 25-lap mile race you’ve got 100 shifts to make. I was shifting not quite halfway down the straightaway. After getting off the corner about the same as the Harleys, I could pass them around the start-finish line, but then the corner comes up and I really had to drive it into the corner hard to make the most of the advantage of the top speed. The corner wasn’t a problem, because I felt real safe on it.’

And what was that top speed? ‘I think I was doing 135, 137mph, in fifth gear, and the thing was still pulling pretty good.’

55

Leather Queen Dee Johnson of D’s Leathers made a race suit for her husband and didn’t stop making dirt track leathers for nearly 50 years

FLAT TRACK LEATHERS have always been an important part of the sport’s draw for me.

Two-piece, zip-together, straight-leg-overthe-boot, those huge numbers on the back...

At the time I got seriously into flat track, all that made them so different to what was being worn in World Superbike and MotoGP. Plus, they were made to last, so sturdy they could stand up by themselves. Since the dawn of the AFT era, European brands, specifically Dainese and Alpinestars, have moved into flat track and now outfit the majority of the pros. Before that, and dating back to the 1960s, the vast majority of pro racers’ leathers were handmade in the USA by Vanson, Bates, ABC, NJK and, of course, D’s. Now, leathers are thin, made to be light and flexible, with inbuilt air bag systems. They’re made to protect, of course, but not necessarily to survive multiple, or even one, highspeed crashes. D’s Leathers were trusted by the stars, and were paid for, not given by the manufacturer as part of a sponsorship package.

We tracked down the now-retired Dee Johnson, who has made some of the greatest leathers for the greatest riders, and also helped run her family-owned race team.

How did you start out in business?

I started the leather business because my husband, Larry, wanted to go flat track racing and he needed a leather suit. We had three kids and money was tight,

but because I made all the clothes they wore I told him I would give it a try. I called every pattern company in the US and no one could make me a pattern for the race suit so I set out to make my own. That project took me about a month, using cloth material as a pattern, trying it on my husband when he came home from work, then altering it to make it fit. It finally did! Then I needed a machine. My friend had one and loaned me it, but of course it didn’t work, so I had to get parts and fix it. I ordered leather from a place called Tandy Leather, and the sewing began. Larry wore the suit (which I still have) to the races and the orders started to pour in. I had no idea it would turn into a job, but it did, and it has given me a very happy life. I got to stay home and sew from my basement and raise my kids.

How long were D’s Leathers in operation?

I was in business for nearly 50 years and I would make at least 100 suits a year. I had to quit making suits last year [2019] due to an eye condition. I tried continuing after a year of surgeries, and made a couple of pairs of pants for Scott Parker and an easy drag racer suit, then came the suit with four quarter-inch stripes and a quarter-inch separation. It was a struggle to finish it, taking me two weeks when it would normally have taken two days. That made my decision to retire. It was hard for me to quit the job I loved so much. I had planned on working to noon on the day of my funeral.

Words: Gary Inman Photos: Shogo Nakao (opposite); Flat Trak Fotos (all others)

Words: Gary Inman Photos: Shogo Nakao (opposite); Flat Trak Fotos (all others)

Dee Johnson, as resilient as the suits she’s famed for. It took an eye condition to force her to finally quit

57 >

Why concentrate on leathers for dirt track racers?

In the early days I made road race and drag race suits too, but got so busy with the dirt stuff I had to make a decision. It was easy, as dirt track was, and still is, my favourite type of racing.

To start my business I needed money, so my husband sold his boat, as he had quit racing because we didn’t have the money to buy a 750 bike and he had made Junior status. So, with the first money I made I surprised him with an XR750 race bike that I bought over the phone from a guy in Indiana. Larry was helping kids build bikes at the time and what a thrill it was for him and the kid that he was helping, named Randy Raker. Over the years we had lots of kids ride for us. We had two Harleys, so we always had a Junior kid and an Expert. I would sell Pirelli tyres to make gas money, so we didn’t have to take prize money from our riders.

It seems like the custom leathers business would be very focused on the off-season.

I was always booked for the season by January or early February, non-stop sewing till late in the night. I am proud to say I never let a customer down. When I told him he would have his suit by a certain date, no matter if I didn’t sleep, he got his suit. I knew what work I could accept, sometimes underestimating the time it would take me to make the suit. I never missed a race, but I did miss a lot of sleep.

I was blessed to have a friend that could sew to do all my repair work till he had to retire and that’s when my daughter, Debbie, took over and she has done my repairs for 20 some years now, and has made a name for herself in the business.

How many employees did you have?

In the beginning I did it all myself, then it got out of hand and a friend of mine offered to help, which she did for about ten years, but was forced to retire because of illness. That’s when my daughter, Vicky, who is married to Randy Goss, stepped in. What a dream come true she was – and still is. She loved racing too, so it was a labour of love for her like it was for me. She had a natural knack, and she cut out all my letters and logos till the day I retired.

Who was your favourite customer or racer?

Now that’s a question too hard to answer. I loved all my customers and knew them all personally from going to the races and sponsoring a team. To mention a few: Scott Parker. I was the only one who ever made his suits, except for the one plastic suit his mom made for him when he was about eight. Joe Kopp is special, he lived with us during race season for about five years until he got married. I was so proud to be asked to make his son, Kody, a suit when he started racing a few years ago. Then there’s Randy Goss, who is my son-in-law, so I can’t leave him out. Kenny Coolbeth. As with Scotty, I was the

‘my daughter, Vicky, who is married to Randy Goss, stepped in.

What a dream come true’

> >

(clockwise from top left) George ‘Geo’ Roeder and Dee in 2005; Check out Geo Roeder at Lima, 1995; Another of the Roeders, Will, road racing an XR1000 at Daytona, 1985; Kevin Atherton and Dan Butler in mid’90s high fashion; Scott Parker in one of the dozens of D’s suits he had; Kenny Coolbeth, one of a long line of Harley champs who trusted D’s leathers

(clockwise from left) Steve Morehead in 1998. Now race fans can see him mopedmounted as AFT’s Track Director; Randy Goss in classic H-D colours; Joe and Garrett Kopp; How many champions have worn D’s Leathers?; Eric Rausch styling it out on Daytona’s short track in 1988

It’s 1990, Sturgis. You’ve got a hot Rotax, neat leathers and shades on. Time to haul ass

only person to make Kenny’s suits. Ricky Graham was a great friend and I was proud to have worked for him. Corky Keener was my third customer, and he gave me my company name. He said, ‘There was ABC Leathers and now there’s D.’ He even drew me my first logo. He wore the suit I made him to Houston Astrodome races for the first time [in the mid-1970s]. At that race, I presented Dick O’Brien (H-D factory team manager) the bill for the suit, he asked where the rest of the bill was and I told him that was the total bill. From then on, till Vance & Hines took over the flat track programme three years ago, I made all their racing suits.

I can’t leave out Bart Markel and Neil Keen. They were the ones who introduced me to Wanda Pico, who had made leathers in California, but was retired. She had been looking for six or seven years to give the business to someone and I was the lucky one to be picked. She gave me her pattern, which was better than mine, and all her connections of where to buy supplies. Remember, this was way before the time of the internet. She even gave me the sewing machine that I still sew on and made everyone’s suits on. I was forever grateful to her and her husband, Ernie.

And I can’t forget to mention one of my all-time favourites, Steve Morehead. He rode for our team for most of seven years. He’s a great guy and still a wonderful friend.

Are there any designs that stick in your mind as being your favourites?

Oh, another hard one. I always hated to make the same thing twice, so when I worked on the Harley suits I would make one, then do another racer’s suit, then go back to the next Harley suit. The year before he retired, I had to make about 12 suits for Scott Parker, so I made them all different and he let me have freewheel, which was fun.

Another memorable suit was for the KTM factory riders, Coolbeth and Kopp. KTM sent me a design and it was terrible, with everything on it but the kitchen sink: checks, flames, stripes... I didn’t want to do it, so I called the team manager and had a discussion. He was hard on me and was sticking to his guns, so I made him a proposition that I would design the suit and make it and if he didn’t like it, he didn’t have to pay for it. I had never made an offer like that before, but knowing Kenny and Joe, I knew they wouldn’t want the design KTM had sent me to do. Eventually, the manager accepted. The kids went to Daytona with my new suits and that week Cycle News came out and they were in the paper with lots of photos. That’s when the team manager called me, said I did a good job and that the cheque was in the mail.

How do you feel when you see racers still competing in leathers you made years or even decades ago?

Very proud of my product. I tried to give the kids the best I could and I think I must have succeeded as they’re still around after all these years. My daughter gets 15- to 20-year-old suits in from racers who have decided to go Vintage racing, but for some reason their leathers don’t quite fit around the waist anymore. She enlarges them, has them put oil on them and makes them like new again.

What do you miss about running your business?

There was never a day I didn’t love my job. Yes, it was tiring at times, but always fun to please my customers and they always appreciated what I did. I don’t go to the races every week like we used to, but I still keep in touch with my customers. Like I said, there was never a thought of retiring, but when my eye failed I had to quit. Now I spend my time sewing costumes, you can make a mistake on fabric, but there is no forgiving a mistake on leather.

Motorcyclessaved

Words: A Dirt Track Racer Illustration: Nick Simich

IT’S MORNING. THOSE precious couple of seconds between my mind fully waking and reality hitting pass all too quickly. During that brief window, I feel alive, invigorated and so positive, like anything is possible and life is as easy as it used to be. Then, like the vignette on some early photographs, it closes in and that’s it, until sleep again.

My life is by no means matched to the hardships that some people suffer. It could never be compared to those suffering severe illness or injury, experiencing poverty or war. However, it is the world in which I live, cannot escape... every single day. I’ve read comparisons to heavy weights bearing down upon people; dark clouds or fog; overwhelming oppression. It’s different for everyone, but the effects it has on dayto-day life are all absolutely real.

It’s only now, after some particularly difficult years, that I have pieced together and begun to understand what goes on in this mind, the one we try to protect with our wellused helmets.

As a child, I was well cared for and raised in a family with a lot of love, but also a lot of bullying, conflict and manipulation. The two halves could not be more opposite.

I was timid, chubby and terrible at ball sports due to lacking depth perception. This all went against me at school and the mental bullying and belittling continued relentlessly at home. Each day, all of the traits I hated about myself were continually reinforced, exacerbating my feelings of inadequacy and inferiority. On top of that, my childhood was made up of a series of false hopes. We would be tantalised by a holiday, day trip or being allowed family visiting, only for it to be withdrawn at literally the last minute, sometimes in the car about to set off. My whole world was so insular, with no overseas trips and very few away from the village I grew up in. I was taught that xenophobia, homophobia and racism were all traits that should be continued down the dark side of the bloodline, along with

mental/physical abuse. There was no reasoning other than it was what previous generations had championed, so it was clearly right.

All of this led me to cope by shutting out as many feelings as I could, no feelings equals no pain, right? Well, at least that’s how I thought it worked. When I was able to become independent, I entered a very physical, masculine industry, to prove to myself I wasn’t the weak embarrassment so often referred to. I threw myself into overseas volunteer work in difficult countries or provinces – small South American islands run by cartels being one that sticks out – again, to

We all feel good when we get on a bike, that’s why we do it. But for some, a motorcycle is a true life force

my life

prove I could. Each time I moved somewhere new, took up a new hobby, started a new job, it was always something daunting and scary, something that made me toughen up and stay that way. This was my Forrest Gump period. I had some incredible experiences, alongside those that were not so good, but none that I would change.

In an effort to protect myself, I had successfully blocked out so many negative feelings, but at the expense of becoming numb, thereby feeling very few positive feelings. Throughout my adult life I have always felt like a fraud, or an imposter, living in dread of being found out – every single second. It is relentless and so overpowering.

In my mind I’m still the timid boy. All that I have achieved since then I see as pure good fortune and dumb luck. I don’t for a second feel deserving of any of it.

I am no angel and would not claim to be. Drinking heavily led to various lapses in judgement, in turn crushing people I love dearly. I have been an asshole in the past, although most of my life has been spent trying to avoid becoming one of the assholes in my life, or those in the all-too-large asshole demographic.

THERE AREN’T MANY experiences in life that can offset this. In fact, only one that I am fortunate to have regular access to.

When time and money allowed, there was motocross and enduro, adventure riding overseas, messing around with little bikes... With each turn of the wheels, the polarity of unhealthy mind and riding mind became ever more obvious. The noise, the dirt, the tastes, the smells, the pure freedom, all combined to make another world, one that I could feel at home in. Even now, all of my senses relish even just minutes in the seat.

Clutching a strap in each hand, pulling slightly apart, then ducking my head, I put the helmet on. It’s grubby, got a few scrapes and chips and, well, smells like a combination of sweat, joy, fumes, fear and dust. The feeling I experience then is one of excitement, trepidation and of a mind finally filtering out the deafening noise that predominantly fills it. A final run through of mental bike checks, swing a leg over, clutch in, shift into a gear, pick up the revs, then let all the feelings in!

Whether racing or trail riding, the countless positives are always there. The adventure, the buzz, the friends, the pain,

the smells and sounds, the visceral decisions made by muscle memory before the brain even processes what’s going on. For me, even crashes and injuries differ from those elsewhere in life. They happen in pursuit of something special and meaningful, so although in themselves not something to be taken lightly, they can be dealt with in my mind. Once recovered from, they can be looked back on as hurdles overcome or challenges bested.

I’m certainly not a naturally talented rider, or engineer, I am a slow learner, but I learn – slowly. Each minor accomplishment is quite the opposite when you have a lid on. Thankfully, this isn’t a big deal when you have such friendly, like-minded people around you. Anything is possible. In life, I avoid people as much as possible, always feeling that inferiority. In my bike-related world, it’s the opposite. Never have I felt so comfortable with other people as I do with those in the DTRA. This UK flat track series, this lifestyle, is one that hasn’t been affected by commercialism and the modernday fakery a lot of other organisations see. It is accepting of everyone – pro or first timer, big or small, male or female, brand new or shed built. It’s like the convergence of two great lines into the perfect berm, hooking up and giving that immense drive forward.

The benefits of people like this in one’s life are immeasurable, benefits that extend away from the track to off-season days on rainy green lanes, to invites for a session in a garage with someone willing to give their time to help repair a bike or teach you something.

The legacy of a good ride or race meeting lasts days – not just the sense of achievement and general buzz, but the calm it brings in the mind. Alongside the love of bikes, fittingly, is my love of dirt. Digging it, moving it, getting covered in it. It’s just a basic, natural, simple material; no hidden motives or meanings.

I’m numb most of the time. I don’t mind it now I understand it better. It’s something I have looked at logically, almost too calmly. Over the years, things have become so dark on occasions that the obvious end to it all would come to mind. Not in a melodramatic way, not seeking attention, more a calculated solution to a lifelong problem. Like a lot of depression and mental health issues, this really takes hold in the winter – the darkness, crap weather, general dampness. The winter, for a lot of riding, is generally the off-season, a major downer for me. A few years ago, mid-winter, more than the usual excess of whisky was consumed, too many sad memories were mulled over and the last two verses of a track called The Train, the Drink, and the Dawn by Kill County, went round and round in my head. I got closer than ever that night… Since then, I’ve got back into winter riding on MTBs and enduros, and I’ve shared the best experiences on winter days.