Issuu Link: https://issuu.com/silencer0208/docs/g1.8.st2.issuu

ARCH_7042 DESIGNING RESEARCH 2024 PROF. SAMER AKKACH David Ebsary /A1788458 Zhuoran Zhang/A1809828 ETHICAL DIMENSIONS OF ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN AESTHETICS SOCIAL CRITICISM

2 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

‘Design always presents itself as serving the human but its real ambition is to redesign the human. The history of design is therefore a history of evolving conceptions of the human.

To talk about design is to talk about the state of our Species’.

Colomina and Wigley

CONTENT 05 / SUMMARY 07 / ARCHITECTURAL ETHICS LITERATURE 08 / AESTHETIC ETHICAL DESIGN 10 / THE HIGH ART 12 / THE NEW SCHOOL 13 / THE NEW MARKET 14 / AFFLUENT DESIGN 16 / HOSTILE ARCHITECTURE 18 / DISCUSSION & ARGUMENTATION 19 / CONCLUSION 20 / NOTES 21 / BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 / IMAGE REFERENCES 23 / CHECKLIST

SUMMARY

(99 words)

Within the architectural field of social criticism, we are introduced to the subject of ethical design. Due to the multi-dimensional complexity of ethics, design must be considered from a contextual position. For instance, the definition of design ethics differs when considered from an aesthetic standpoint to a socially reprehensible one. We argue that within ethical architecture, tension exists at the intersection of aesthetic and socially responsible design. We also argue that this ethical tension impacts design affecting human self-perception and behaviour, this relates to Colomina and Wigley’s statement that ‘the real ambition of design is to redesign the human’. 1

STUDENT: DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)/ ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828) ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM / 5

LinkedIn. February 8.

Fig 1. Angel Statue (Source:

Knezevic, Branka. 2021. “Ethics in Architecture.”

Internet)

1. Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on a Archaeology of Design (Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers), 3.

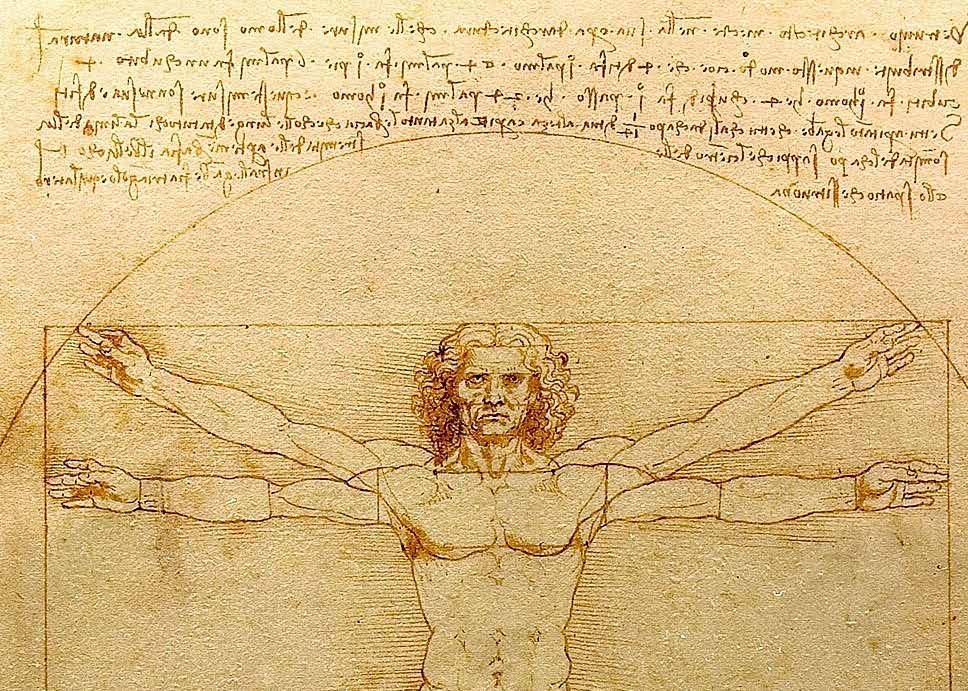

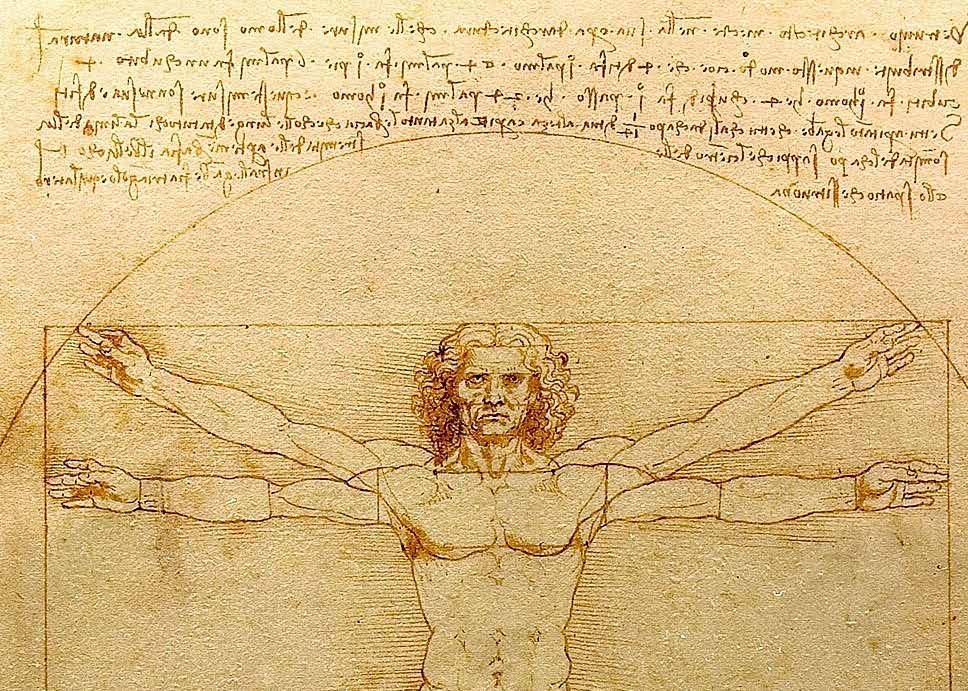

Fig 2: Vitruvian Man (Source: “Vitruvian Man.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. March 29. Internet)

Fig 2: Vitruvian Man (Source: “Vitruvian Man.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. March 29. Internet)

ARCHITECTURAL ETHICS LITERATURE

Design is a diversified and multi- dimensional discipline; it is intrinsically linked with the evolution of human society. According to the book by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, `Are We Humans? Notes on an Archaeology of Design,’ throughout history design has always presented itself as serving humans, however the real ambition of design is to redesign humans.2

In this article we aim to clarify that the multidimensionality of architectural ethics requires a distinct approach to rethinking what ethical design is. The definition of ethical design differs depending in what context design is being applied. We will focus on two dimensions of ethical design in context - aesthetics, and social responsibility, by delving into some of the social criticisms within the architectural profession.

To support our argument, we will discuss the following books and journal articles. Alberto Pérez-Gómez’ book, ‘II Philia, Compassion, and the Ethical Dimension of Architecture: Program’, focuses on the topic of ‘Ethical dimensions of Architecture’. The book emphasises architecture’s ethical responsibilities being beyond architectural production, therefore architecture’s role is to address fundamental human issues through poetic and critical means.

‘Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas’, edited by Nicholas Ray, provides background to how morality and traditional understandings of ethics in architecture are interpreted thorough aesthetics and functionality.

‘Out of Site: A Social Criticism on Architecture’ is a collection of essays edited by Diane Ghirardo, examining a diverse range of social criticism about the architecture profession. The essays criticise the production of unethical design, viewing ethics within a moral context. Within this compilation, Margaret Crawford’s essay, ‘Can Architects be Socially Responsible?’, focuses on the architecture profession being at the ‘mercy’ of the power, corporate entities and governments have over society.

‘Ornamentation and Crime’, written by Adolf Loos is a critique of 19th century ethical dilemmas, presenting his belief that European architecture is ‘primitive’ and lacking progress. Adolf Loo’s writings portray an understanding of ethics within an aesthetic and functional context. Janet Stewart’s publication, ‘Fashioning Vienna: Adolf Loos’s Cultural Criticism’, examines Adolf Loos’ formation as an architect, interior designer, and artist, who lived through Vienna’s Secession. She offers an analysis about Adolf Loos’ architectural ideology and the contradictory nature of his antiquated views.

‘The New Architecture and the Bauhaus’, written by Walter Gropius in 1935, focuses upon his core beliefs of architectural design’s function within society, attempting to address social reprehension within the architectural profession.

‘From Industrial to Artisan: Modernism’s Sleightof-Hand,’ is a chapter written by Nikos Salingaros in the book, co-written with Michael Mehaffy, ‘Design for a Living Planet,’ critiques claims that modern architecture is an evolutionary

progressive design, far superior to its predecessors. The critique emphasizes that Modern Architecture considers ethics entirely from an aesthetic perspective.

The research paper, ‘Decadal erosion of coral assemblages by multiple disturbances in the Palm Islands, Central Great Barrier Reef’ highlights the implications of design aesthetic ethics over ethical morality, like many other coral reefs around the world that may never recover to their previous condition, changing their functionalinty within the ecosystem.

And finally, ’Callous Objects: Designs Against the Homeless’, is an article by Robert Rosenberger, discussing morally unethical design that deters homeless people from sleeping rough. By using the ideas from social theory and philosophy of technology on the often-hidden reason agendas behind them. Considering the nature of technology itself, how to change it to affect the public.

STUDENT: DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)/ ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828) ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM / 7

2. Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on a Archaeology of Design (Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers), 3.

AESTHETIC ETHICAL DESIGN

Architecture’s ethical dimensions have implications for aesthetics, design, and social criticism. It serves individuals and communities while upholding ethical principles, which is a central component of architecture’s context. Architects’ practice and discourse are shaped by their ethical values; these values are diverse as ethics is multi-dimensional in nature and play an extremely important role in the design process. There are various ethical dimensions of architecture that influence how it is practised and how it affects society. According to Alberto Pérez-Gómez on his book ‘Built upon love’, he proposes that the responsibility of architectural design extends beyond production; it cannot be deregulated through legislation alone. He articulates that, ‘It is like literature and film; architecture finds its ethical praxis in its poetic and critical ability to address the questions that truly matter for our humanity in culturally specific terms.’ 3

Architectural design plays a crucial role in preserving traditional cultures and valuing those by preserving them to the best of our ability. As Nicholas Ray discusses in his book, ‘Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas’, there is a philosophical relationship between architecture and the ethical judgement of its position. He states, ‘Architectural value may thus be determined by reference to functionality: if a building is good for people and their purposes, then it is ‘moral’. ⁴

Ray talks about how this kind of thinking is ineffective as architectural value is a philosophical issue at its core. A common misconception amongst people is that functional and emotional assessments are secondary in nature, as people’s standards for ethical design are based on their desires. Similarly, Alberto Pérez-Gómez discusses the ethical dimension of architecture by emphasising concepts such as feeling, highlighting the architect’s difficulty in balancing design creativity with social ethical responsibility. In the book, ‘Are We Human?’, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley make a comparable statement, ‘design discourse acts as if human needs and desires unproblematically organise design’. 5

Humans design according to their needs and desires whilst ignoring the deeper architectural ethical issues such as social responsibility underlying the design. Colomina, Wigley, PérezGómez, and Ray’s discussion on ethical design in terms of expression, desire, and culture draws similarities to the way the arts express human emotion.

3. Alberto Pérez-Gómez, 2006, ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture’ in Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT) 204-207.

4. Nicholas Ray, 2005, ‘Ethics and Aesthetics’ in Nicholas Ray (ed.), Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas (London: Routledge),133-134

5. Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on a Archaeology of Design (Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers), 127.

8 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

The Taj Mahal is built upon love. A marble mausoleum built by Shah Jahan in memory of his wife, Mumtaz Mahal. The monument was built not only to house the queen’s grave but also to evoke the imagery of paradise on Earth.

STUDENT: DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)/ ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828)

Fig 3. Taj Mahal (Source: Mitchell, Austin Jesse. 2020. “Nobody Knows Who Designed the Taj Mahal.” Discovery. Discovery. February 25. Internet)

THE HIGH ART

Diane Ghirardo highlights the architectural profession’s inseparable connection to art, expressing the implications of this mindset. Classism is an issue that has been a continual barrier within the profession, resulting in elitist, apathetic, and sympathetic attitudes among architects. Ghirardo emphasises a comment made at an architecture conference, ‘For designers, architecture is more than just a box…Any hack … can build a dumb box…real architecture contains ideas about society and expresses the cosmology of culture.’ 6

This response highlights the industry’s perception of architecture as ‘High Art’. Many architectural professionals present an elite persona, believing that the creative architectural process is transcendental and only they can discern the meaning and apply it to design. 7 There are two implications that arise from this belief. Firstly, the primary consumers of ‘High Art’ are of high status both socially and culturally because aesthetic, ethical design is unaffordable, resulting in segregation of social class. Secondly, architects consider themselves experts on all matters, dictating what the customer’s needs, this lack of consultation results in poor design outcomes failing to meet the customer’s needs.8 Conversely, socially responsible architects, who engage clients and consider environmental impact encounter barriers when implementing ethical values within their designs. These obstacles include insufficient funding, client/ stakeholder disinterest, and political opposition. Unfortunately, architects willing to address ethical issues within design become disenfranchised and apathetic towards social injustice due to these barriers. The segregation of social class caused by the ethical tension between socially responsible,

and aesthetic design is evident in the Vienna Secession.

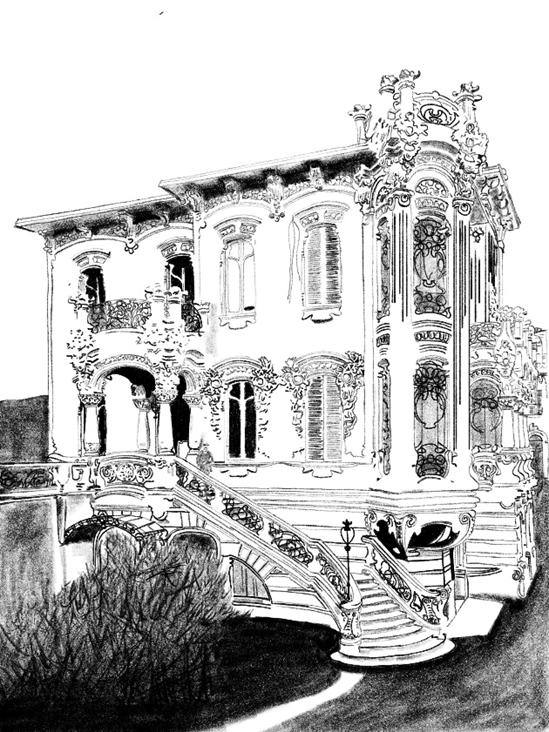

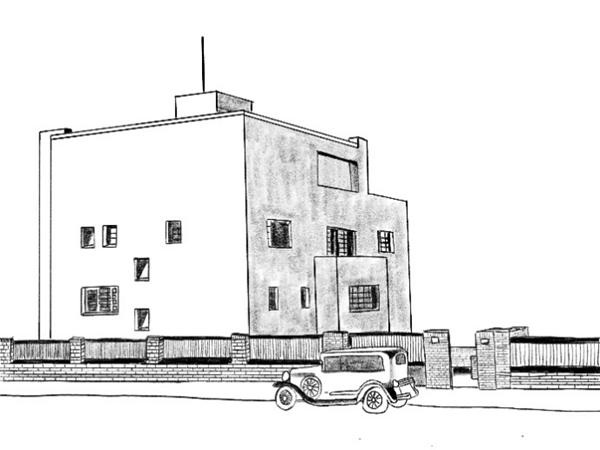

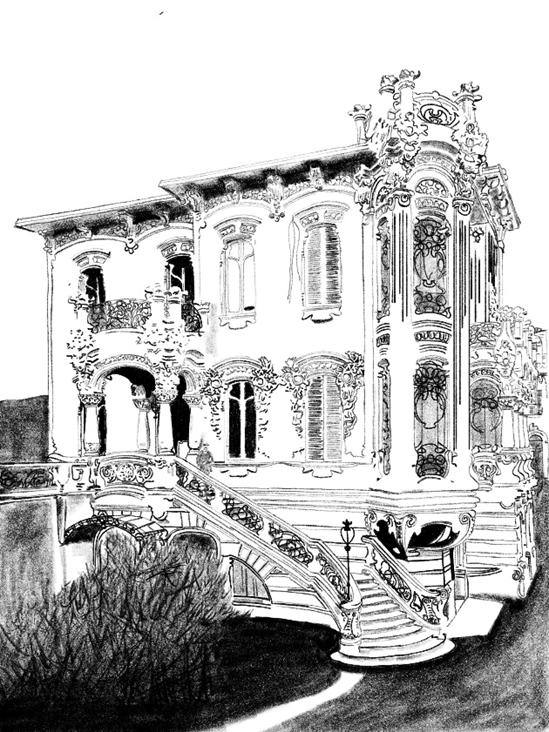

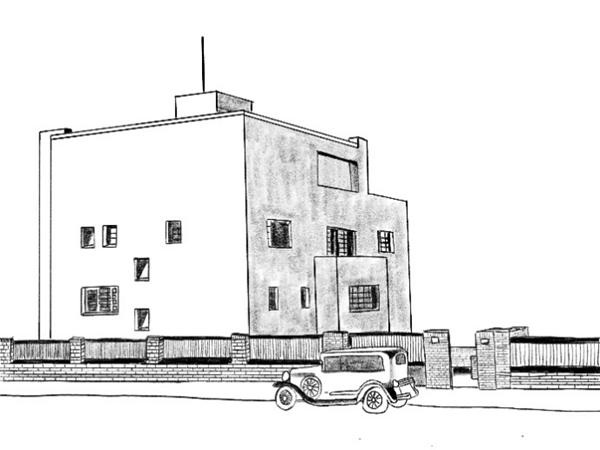

At the turn of the nineteenth century, during the shift from classical to modern architecture, ‘High Art’ was commonly employed in classical architecture. Modern Architect pioneer Adolf Loos, lived in Vienna during this era. His ideologies and design style formed in reaction to the Art Nouveau style. In ‘Ornament and Crime’, Loos expresses his distaste for decorative facades in Architecture, believing that ornamentation of facade cheapened the natural beauty of the underlying material, the true feature with aesthetic dominance.

Adolf Loos believed society had matured and evolved where Architecture had not, to him, ‘Art Nouveau’ was unevolved and primitive like the artistry of Papuans’ tattoos. As described by Nicholas Ray, for Adolf Loos, architectural value came from functionality and simplicity, if a building is good for people and their purposes it is ‘moral’. Despite Loos’ beliefs about ornamentation in Architecture, he appreciated the school of fine art but as a separate entity from the architecture profession, he believed that artisans of fine arts should be respected and handsomely compensated. 9

Janet Stewart raises Adolf Loos’ interpretation of social class in ‘Fashioning Vienna’. Vienna was a city with well-defined social boundaries separating the Bourgeois from ethnic, and Industrialist working classes, aristocrats in the inner city, middle-class around the Ringstrasse, and lower class on the fringe. Loos disagreed with Vienna’s urban design, convinced social structure should not be based upon Capitalist class structure but upon an ‘evolved’ modern structure of stratified estates giving allegiance to royalty. 10

Walter Gropius, like Adolf Loos is another Modern Architecture pioneer that demonstrates Nicholas Ray’s ethical statement regarding the importance of aesthetics and function. Like Loos, Gropius believed that ornamentation should be curtailed to give prominence to structural function and the material’s aesthetic, as this pleased the soul. However, Walter Gropius’ ethical approach to design was more nuanced than Loos, Gropius disagrees with the idea that art should be separated from the architecture profession. In contrast Gropius establishes the Bauhaus State School in 1919, combining the Weimar Arts and Crafts School with the Academy of Fine Arts. He believed that for the architectural profession to progress, design education needed a holistic approach that combined the fields of art, craft, and technology into one school.

6. Diane Ghirardo, 1991, ‘Introduction’ in Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press), 9.

7. Diane Ghirardo, 1991, ‘Introduction’ in Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press), 12-13.

8. Margaret Crawford, 1991, ‘Can Architects be Socially Responsible?’, in Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press), 38-39.

9. Adolf Loos, 1908, ‘Ornament and Crime’ in Ornament and Crime (London: Penguin), 253-278.

10. Janet Stewart, 2000, Fashioning Vienna: Adolf Loo’s Cultural Criticism (London: Routledge), 72.

10 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

STUDENT: DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)/ ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828) ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM / 11

Fig 5. Villa Muller, Prague (Source: Internet) The plain facades of Adolf Loos’ ‘Raumplan’ architecture highlight the removal of ornamentation.

4

Fig 4. The Villa Scott, Turin (Source: Internet) An example of Art Nouveau, displaying the intricate ornamentation of 19th-century architecture.

THE NEW SCHOOL

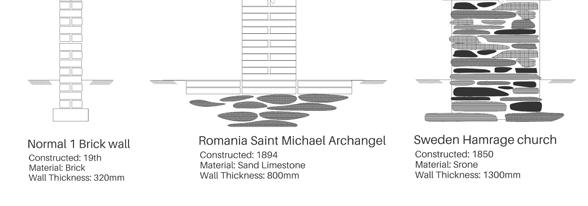

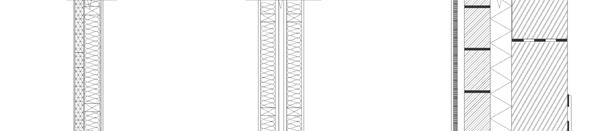

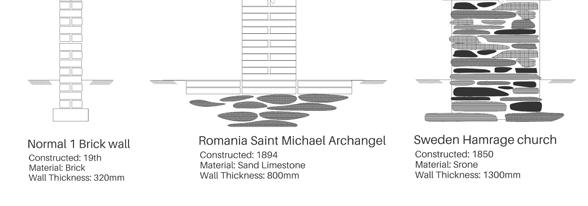

Walter Gropius’ ideologies echoed Adolf Loos’ arguments about the lack of progress in architecture, stressing the importance of utilising technological advancements and mechanical production, fearing the architecture profession would be left behind. Gropius’ aim was to adopt new technological advances to produce synthetic building materials such as steel, concrete, and glass and incorporate them into building design. These newly developed synthetic materials decreased size, weight, and bulk, and increased functional space, effectively decreasing construction costs. Another cost-effective solution suggested by Gropius was Standardisation. Construction costs could be decreased by prefabricating standard sized materials and fasteners that are readily available and minimising the unnecessary production of bespoke non-essential bespoke materials. 12

When contrasting the ethical values of Walter Gropius and Adolf Loos, there is a noticeable shift from function, aesthetics and expression being the fundamental focus of ethical design to social responsibility. This can be seen in Walter Gropius’ focus on cost effective construction utilising prefabricated materials, simplicity of design, making it the ‘ideal’ solution for social housing.

Unfortunately, this was not the case, Gropius’ vision was unviable for large scale residential construction, as it was too costly for the average person, instead prefabrication was used predominantly in commercial construction, as corporations were able to absorb the construction costs. Regrettably for Gropius, the minimalist approach to ornamentation did not deter architecture’s reputation as ‘High Art.’ In ‘The New Architecture and the Bauhaus, Gropius laments, ‘Worst of all modern architecture [has] become fashionable in several countries; with the result that formalistic imitation and snobbery distorted the fundamental truth and simplicity on which the renascence was place.’ 13

19TH CENTURY THICK MASONRY WALL

BRICK WALL

Constructed: 19th Century

Material:Brick

Wall Thickness: 320mm

Constructed: 1894

Material: Sand Limestone

Wall Thickness: 800mm

Constructed: 1850

Material: Stone

Wall Thickness: 1300mm

MODERN THINNER WALL

FOAM CLADDING ON TIMBER STUD

Material: Timber

Wall Thickness: 256mm

DOUBLE STUD TIMBER

Material: Sand Limestone

Wall Thickness: 800mm

CONCRETE WALL

Material: Stone

Wall Thickness: 1300mm

11. Walter Gropius, 1965, The New Architecture and the New Bauhaus 1 ed., trans. P. Morton Shand (London: Faber and Faber), 23-25

12. Walter Gropius, 1965, The New Architecture and the New Bauhaus 1 ed., trans. P. Morton Shand (London: Faber and Faber), 34.

13. Walter Gropius, 1965, The New Architecture and the New Bauhaus 1 ed., trans. P. Morton Shand (London: Faber and Faber), 20-21.

12 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

Fig 6: Evolution of Building Wall (Source: Zhuoran Zhang ) An example of the progress made in technology in construction at Modern Architecture’s conception.

SWEDEN HAMRAGE CHURCH

NORMAL

ROMANIA ST MICHAEL ARCHANGEL

THE NEW MARKET

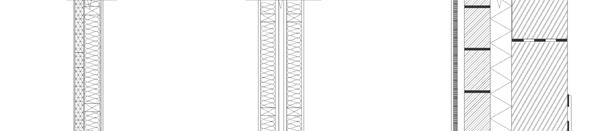

In the article, ‘Sleight of Hand’, Nick Salingaros argues about the authenticity of Walter Gropius, his Bauhaus colleagues and proteges’ values and true ambition. They claim that Modern Architecture has been framed by the modern pioneers as the ‘Saviour of the World’, in which it’s foundational principles are the solution to all issues caused by ‘defunct’ architectural styles.

Salingaros suggests that the industrial look is purely aesthetic preference that has nothing to do with simplicity, efficiency, or cost effectiveness. The idea that industrial prefabrication is superior to the ornate designs of artisans was essentially a marketing campaign by Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus, and many other modernists. The pioneers of Modern Architecture had successfully convinced the masses that the machine aesthetic and industrialisation was the latest technological advancement and the solution to provide socially just design.

Salingaros illustrates this point using images of a teapot with the “machine aesthetic” compared with a jewellery box adorned with Art Nouveau produced thirty years later. When asked which object was older, most observers falsely assumed that the Art Nouveau jewellery box was older. In finalising his critique, Salingaros states that in good design, minimalism, and simplicity act in balance with functional and aesthetics of a product. The Bauhaus marketed an image of ‘utopian’ change through the dogmatic application of minimalism. Unfortunately this was at the expense of aesthetic design within the built environment. 14

14. Mehaffy, Michael and Nikos Salingaros. 2015. ‘From Industrial to Artisan: Modernism’s Sleight-of-Hand.’ Design for a Living Planet (1-3). Portland, Oregon: Sustasis Press. Accessed 22 May 2024. https://patterns.architexturez.net/doc/ az-cf-198839

STUDENT: DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)/ ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828) ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM / 13 5

Fig 7. Two Teapot Images (Source: © Nikos A. Salingaros) (Left) Mass-produced Art Nouveau silver jewelry box by P. A. Coon, 1908.

Fig 8. Two Teapot Images (Source: © Nikos A. Salingaros) (Right) Handmade Machine Aesthetic silver teapot by C. Dresser, 1879. The machine aesthetic was an artistic metaphor of “modernity” chosen by Loos — not a true function.

AFFLUENT DESIGN

Juxtaposed to the lack of aesthetics in some Modern Architecture designs, are the monumental skyscrapers and structures of the United Arab Emirates. The Palm Islands or Palm Jumeirah is an example of exploring the intersection within ethical design between aesthetics and social morality. The project’s aim was to increase Dubai’s coastline to develop more luxurious modern hotels for more tourists, to do this, the coastline was extended by designing artificial islands in the shape of a Palm tree. The Palm Island project raised social criticism regarding its lack of concern for environmental conservation. The project aimed to be aesthetically luxurious with the latest technologies to boost tourism, contextually the ethical viewpoint for the project was a utopian vision. Critics of the project, on the other hand view the Palm Islands from a moral standpoint, pointing out the Architect’s neglect of their social responsibility to recognise the impact on the fragile marine ecosystem.

The construction process involved large scale reclamation of the sea that disrupted the natural coral reefs and the marine habitat. As a result, the sustainability of the marine environment is now threatened due to the disruption of the complex interconnectedness within the ecosystem. This project not only illustrates oversight in environmental planning and design development, but it also highlights at a deeper level the ethical tension within design. The allure of economic values and architectural aesthetics overshadows the moral values and environmental responsibility. 15

15. Torda, Gergely., Katie Sambrook, Peter Cross, Yui Sato, David G. Bourne, Tessa Hill, Georgina Torras Jorda, and Bette L. Willis. 2018. ‘Decadal erosion of coral assemblages by multiple disturbances in the Palm Islands, central Great Barrier Reef.’ Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group). 2018(8):1. Accessed 22 May 2024. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2085639983?_oafollow=false&accountid=8203&pq-origsite=primo&parentSessionId=%2B5s%2BrbTe8EW%2FdIHj1K30MYSpu83i%2B5yHwu8j1OqUClA%3D&sourcetype=Scholarly%20 Journals

14 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

Fig 9 Artificially constructed Palm Island in Dubai, UAE.

Fig 9 Artificially constructed Palm Island in Dubai, UAE.

HOSTILE ARCHITECTURE

We observed in the case of the Palm Islands the economic values are another dimension that falls within ethics. These values are often prioritised over other values that are just as important. In many situations, architects implement hostile architecture in their designs as a deterrence tool. Tools like spikes can be used to deter pigeons from excreting on vertical facades, this can be considered either useful or inhumane. Unfortunately, Hostile Architecture is a deliberate approach used in design to prevent homeless people from sleeping or lingering in public spaces. Examples of these designs are uncomfortable features built into public seating, such as armrests in middle of the benches, instalment spikes and contoured seating surfaces. Additionally, placing large rocks under bridges are employed to dissuade vulnerable people seeking refuge in these areas.

While these measures aim to maintain public order and aesthetics, it has raised morally ethical concerns regarding social exclusion. Social criticism highlights how this kind of hostile architecture impacts the vulnerable and the whole of society by marginalising the vulnerable, leaving them with no where to go, and instilling apathy among the rest of society, who ignore their plight. The most morally unethical characteristics of Hostile Architecture is the attempt to camouflage its hostile nature with aesthetic design and prioritising the aesthetics of a built landscape over the needs and lives of vulnerable marginalised people. 16

16. Petty, James. 2016. “The London Spikes Controversy: Homelessness, Urban Securitisation, and the Question of ‘Hostile Architecture’”. International Journal for Crime, Justice, and Social Democracy 5 (1):67-81. Accessed 22 May 2024 https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i1.286.

16 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

Fig 10. Concrete spikes under flyovers and bridges in Guangzhou China

Fig 10. Concrete spikes under flyovers and bridges in Guangzhou China

DISCUSSION

Ethics within architecture is multi-dimensional, consisting of multiple value systems. As Alberto Pérez-Gómez says, ‘It is like literature and film; architecture finds its ethical praxis in its poetic and critical ability to address the questions that truly matter for our humanity in culturally specific terms.’17

Alberto Perez-Gomez’s point emphasises our argument highlighting the tension within ethical design. Aesthetic design represents architecture’s poetic ability, and social responsibility represents architecture’s critical ability to address what truly matters to humanity. By applying one or multiple ethical values, design is able to provide suitable solutions for a specific context in a meaningful way. The Palm Island project in Dubai prioritizes aesthetic design and economic gain over environmental sustainability, leading to ecological destruction. As ethical design is multifaceted both value systems could have been applied to design to provide a successful outcome. This demonstrates that economic values are another dimension of ethics that clashes with moral values. Economic values are often prioritised over other values that are just as important because they are deeply entrenched in the human psyche, impacting most aspects of life. Interestingly, not only does wealth compete with morality, it is even expressed in terms of morality, if you are wealthy, you must be doing something right, but if you are poor, you must be doing something wrong.

Sadly, it is the poor who are often affected by the impacts of ethics on design, Hostile Architecture demonstrates the unethical design within architecture, provoking reflection about serious ethical concerns such as social exclusion and prioritising funds for Hostile Architecture that deters people, rather than building new homes for people displaced by Hostile Architecture.

As emphasized by Alberto Pérez-Gómez, the ethical dimension of architecture transcends mere production processes and carries inherent ethical responsibilities that must be foregrounded in practice. 18 Therefore, ethical architecture design is not just about space and configuration; it also needs to reflect social values and human conditions.

According to Margaret Crawford’s article, ‘Can Architects be socially responsible?’ The architeture profession has steadily moved away from engagement with any social issues, even those that fall within their realm of professional competence, such as homelessness, and the growing crisis in affordable and appropriate housing.19 The ethical dimension of architecture is crucial in bridging the gap between architects and society, it must ensure that an architectural project does not serve economic or aesthetic purposes, instead, it must address the needs and rights of society.

This gap will undermine the societal role of architects and diminish the impact of architecture as a tool to change society. The ethical dimensions of architecture should be extended beyond elite circles to include with the wider public, who are the end users, often the most affected by architectural decisions.

The process of architecture needs democratisation and public engagement. Democratisation ensures that design outcomes reflect and respond to the needs of those most affected by these projects. Ethical architecture, often challenged by the priority of profit over people, should focus on its ability to contribute positively to society and public life, improve living conditions, and protect the environment. This is interesting because the pioneers of Modern Architecture legitimately believed they were contributing to society; however social

criticism suggests otherwise.

Adolf Loos and Walter Gropius desired a society free of the structured confines of social class, believing that architecture should be simple and unnecessary ornamentation should be removed. These beliefs were a reaction to the upper class, who used Classical Architecture and Beaux Arts, the dominating architectural style during that period.

Their dogmatic opposition to these styles is interesting because both were heavily influenced by the Beaux Arts and grew up in upper class families, their motivations surrounding Modern Architecture appear contradictory. Adolf Loos’s yearned an evolved progressive society, believing this could be achieved through adopting technological advancements and basing societal structures on estates ruled by Lords and the monarchy rather than economics. These unprogressive beliefs and racist attitudes about Papuans seem disingenuous regarding social ethics within architecture. Walter Gropius believes simple design and using prefabricated materials lowers cost, creating a level playing field for consumers. This was not the case as it was too expensive for most.

What Adolf Loos and Walter Gropius beliefs seem to address socially responsible ethics within Modern Architecture, however in practice this is insincere and based purely on an aesthetic style. In this light, Modern Architecture was based upon selling a particular aesthetic style not a functional simplistic design. This continues to emphasise the continuous tension that exists between aesthetics and social responsibility.

17. Alberto Pérez-Gómez, 2006, ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture’ in Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT) 204-207.

18. Alberto Pérez-Gómez, 2006, ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture’ in Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT) 204-207.

19. Margaret Crawford, 1991, ‘Can Architects Be Socially Responsible?, Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press), 27-29.

18 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

CONCLUSION

Ethics is complex in nature and difficult to define as its nature is perceived differently depending on context. Normally, people consider ethics in terms of morality, although this drives much of the agenda for social criticism surrounding our responsibilities as humans, morality fails to completely define what ethics is. Ethics is multifaceted so when we consider ethics, we must clearly define the context that is applicable. Focussing on design ethics we discovered many different perspectives exist within architecture, as there are many, we focussed on a few perspectives , primarily aesthetic design, and socially responsible design.

The multi-dimensional nature of ethics requires a more nuanced approach to the way we think about architectural ethics, meaning ethics requires a unified value system that applies the same way everywhere. A unified value system must be developed and emphasised, in order to bridge the gap that exists between architects and the public. Within ethical design, at the intersection of aesthetics and social responsibility, exists an inherent tension within the architectural profession, which has the ability to alter the impact of design positively and negatively. The impact of ethics upon design is summed up well by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley in ‘Are We Humans?,’ who argue, ‘Design always presents itself as serving the human, but its real ambition is to redesign the human.’

WORD COUNT: 4490

STUDENT: DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)/ ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828) ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM / 19

NOTES

1. Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on a Archaeology of Design (Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers), 3.

2. Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on a Archaeology of Design (Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers), 3.

3. Alberto Pérez-Gómez, 2006, ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture’ in Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT) , 204-207.

4. Nicholas Ray, 2005, ‘Ethics and Aesthetics’ in Nicholas Ray (ed.), Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas (London: Routledge),133-134

5. Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on a Archaeology of Design (Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers), 127.

6. Diane Ghirardo, 1991, ‘Introduction’ in Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press), 9.

7. Diane Ghirardo, 1991, ‘Introduction’ in Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press), 12-13.

8. Margaret Crawford, 1991, ‘Can Architects be Socially Responsible?’, in Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press), 38-39.

9. Adolf Loos, 1908, ‘Ornament and Crime’ in Ornament and Crime (London: Penguin), 253-278.

10. Janet Stewart, 2000, Fashioning Vienna: Adolf Loo’s Cultural Criticism (London: Routledge), 72.

11. Walter Gropius, 1965, The New Architecture and the New Bauhaus 1 ed., trans. P. Morton Shand (London: Faber and Faber), 23-25

12. Walter Gropius, 1965, The New Architecture and the New Bauhaus 1 ed., trans. P. Morton Shand (London: Faber and Faber), 34.

13. Walter Gropius, 1965, The New Architecture and the New Bauhaus 1 ed., trans. P. Morton Shand (London: Faber and Faber), 20-21.

14. Mehaffy, Michael and Nikos Salingaros. 2015. ‘From Industrial to Artisan: Modernism’s Sleight-of-Hand.’ Design for a Living Planet (1-3). Portland, Oregon: Sustasis Press. Accessed 22 May 2024. https://patterns.architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-198839

15. Torda, Gergely., Katie Sambrook, Peter Cross, Yui Sato, David G. Bourne, Tessa Hill, Georgina Torras Jorda, and Bette L. Willis. 2018. ‘Decadal erosion of coral assemblages by multiple disturbances in the Palm Islands, central Great Barrier Reef.’ Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group). 2018(8):1. Accessed 22 May 2024. https://www. proquest.com/docview/2085639983?_oafollow=false&accountid=8203&pq-origsite=primo&parentSessionId=%2B5s%2BrbTe8EW%2FdIHj1K30MYSpu83i%2B5yHwu8j1OqUClA%3D&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

16. Petty, James. 2016. “The London Spikes Controversy: Homelessness, Urban Securitisation, and the Question of ‘Hostile Architecture’”. International Journal for Crime, Justice, and Social Democracy 5 (1):67-81. Accessed 22 May 2024 https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i1.286.

17. Alberto Pérez-Gómez, 2006, ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture’ in Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT) , 204-207.

18. Alberto Pérez-Gómez, 2006, ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture’ in Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT) , 204-207.

19. Margaret Crawford, 1991, ‘Can Architects Be Socially Responsible?, Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (Seattle: Bay Press), 27-29.

20 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archimaps, 2019, ‘Villa Muller, Prague’, Tumblr image drawn by David Ebsary, Adelaide, https://archimaps.tumblr.com/post/182230653482/the-villa-scott-turon, accessed 2 April 2024.

Colomina, Beatriz and Mark Wigley. 2016. Are We Human? Notes on a Archaeology of Design. Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers

Crawford, Margaret. 1991. ‘Can Architects be Socially Responsible?’ In Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture (38-39). Seattle: Bay Press.

Designculture, 2017, ‘Villa Scott, Turin’, image, Drawn by David Ebsary, Adelaide, www.designculture.it/profile/adolf-loos.html, accessed 2 April 2024.

Evolution of Building Elements, n.d., ‘Brick Wall’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, https://fet.uwe.ac.uk/conweb/house_ages/elements/section2.htm, accessed 5 April 2024. masonry wall

Ghirardo, Diane. 1991. ‘Introduction.’ In Diane Ghirado (ed.), Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture Seattle: Bay Press.

Gropius, Walter. 1965. The New Architecture and the New Bauhaus 1st ed. 1935. Translated by P. Morton Shand. London: Faber and Faber.

Loos, Adolf. 1908. ‘Ornament and Crime’ in Joseph Masheck (ed.), Ornament and Crime. Translated by Shaun Whiteside. (253-278). London: Penguin.

Mehaffy, Michael and Nikos Salingaros. 2015. ‘From Industrial to Artisan: Modernism’s Sleight-of-Hand.’ Design for a Living Planet (1-3). Portland, Oregon: Sustasis Press. Accessed 22 May 2024. https://patterns.architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-198839

Pérez-Gómez, Alberto. 2006. ‘The Ethical Image in Architecture.’ In Built Upon Love:Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (204-207). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT.

Petty, James. 2016. “The London Spikes Controversy: Homelessness, Urban Securitisation, and the Question of ‘Hostile Architecture’”. International Journal for Crime, Justice, and Social Democracy 5 (1):67-81. Accessed 22 May 2024 https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i1.286.

Ray, Nicholas. 2005. ‘Ethics and Aesthetics.’ In Nicholas Ray (ed.), Architecture and Its Ethical Dilemmas (133-134). London: Routledge.

Research Gate, n.d., ‘Romania Saint Michael’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Cross-section-in-the-room-of-the-neo-desert-vernacularmodel-house_fig156_247849342

Research Gate, n.d., ‘Sweden Hamrage Church’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, https://fet.uwe.ac.uk/conweb/house_ages/elements/section2.htm

Research Gate, n.d., ‘ FOAM CLADDING ON TIMBER STUD’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, http://open-haus.weebly.com/home/the-raincoat

Research Gate, n.d., ‘DOUBLE TIMBER STUD’, image drawn by Zhuoran Zhang, Adelaide, https://forum.buildhub.org.uk/topic/13558-double-stud-wall-vs-icf-party-wall/

Research Gate,n,d ‘Concrete wall’, Image,Dacher,1/2.2021 Detail Roof strcture ‘Feilden Fowles’ ,57

Stewart, Janet. 2000. Fashioning Vienna: Adolf Loo’s Cultural Criticism. London: Routledge.

Torda, Gergely., Katie Sambrook, Peter Cross, Yui Sato, David G. Bourne, Tessa Hill, Georgina Torras Jorda, and Bette L. Willis. 2018. ‘Decadal erosion of coral assemblages by multiple disturbances in the Palm Islands, central Great Barrier Reef.’ Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group). 2018(8):1 Accessed 22 May 2024. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2085639983?_oafollow=false&accountid=8203&pq-origsite=primo&parentSessionId=%2B5s%2BrbTe8EW%2FdIHj1K30MYSpu83i%2B5yHwu8j1OqUClA%3D&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

STUDENT: DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)/ ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828) ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM / 21

IMAGE REFERENCES

Fig 1. Angel statue : Knezevic, Branka. 2021. “Ethics in Architecture.” LinkedIn. February 8. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ethics-architecture-branka-knezevic/.

Fig 2:“Vitruvian Man.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. March 29. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitruvian_Man.

Fig 3: Taj Mahal: Mitchell, Austin Jesse. 2020. “Nobody Knows Who Designed the Taj Mahal.” Discovery. Discovery. February 25.

Fig 4: The Villa Scott, Turin. An example of Art Nouveau, displaying the intricate ornamentation of 19th Century architecture.

Fig 5: Villa Muller, Prague. The plain facades of Adolf Loos’, ‘Raumplan’ architecture highlight the removal of ornamentation.

Fig 6: Zhuoran Zhang, Evolution of Building wall. An example of the progress made in technology in construction at Modern Architecture’s conception.

Fig 7: Mass-produced Art Nouveau silver jewelry box by P. A. Coon, 1908. On the right, hand-made Machine Aesthetic silver teapot by C. Dresser, 1879. The machine aesthetic was an artistic metaphor of “modernity” chosen by Loos — not a true functiona © Nikos A. Salingaros

Fig 8: Tea pot: 2024. Accessed May 22. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Christopher_Dresser_-_Teapot_-_1879.jpg.

Fig 9: Palm Island:“Upscale Living in Palm Jumeirah.” 2024. Nakheel Communities. Accessed May 22. https://www.nakheelcommunities.com/en/communities/ palm-jumeirah.

Fig 10: Concrete spikes under flyovers and bridges in Guangzhou. Ruetas, Faith. 2022. “15 Examples of Hostile Architecture around the World.” RTF | Rethinking The Future. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/designing-for-typologies/a2564-15-examples-of-hostile-architecture-around-the-world/#e897eb3b47dbb2000c68bd12df1aed669aa472ed#185344.

22 / ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM

Checklist

⃝ Adhered to the word limit in the summary and the article.

⃝ Inserted the main quote by C+W on the inside of the front cover.

⃝ Followed the 5-sentence template in writing of the summary.

⃝ Inserted word count of the summary.

⃝ Inserted word count of the article.

⃝ Adhered to the prescribed number of spreads.

⃝ Adhered to the prescribed number of images.

⃝ Researched and cited the required number of sources.

⃝ Uploaded PDF file on issuu.com and provided active link on the from cover.

⃝ Inserted the checklist on the back cover.

⃝ Uploaded final PDF file on MyUni and Box.

⃝ Uploaded final Black+Blue word file on MyUni and Box.

Student 1

Name: David Ebsary, A1788458

Student 2

Name: Zhuoran Zhang ,A1089828

STUDENT: DAVID EBSARY (A1788458)/ ZHUORAN ZHANG (A1809828) ETHICAL ARCHITECTURE: DESIGN | AESTHETICS | SOCIAL CRITICISM / 23

Fig 2: Vitruvian Man (Source: “Vitruvian Man.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. March 29. Internet)

Fig 2: Vitruvian Man (Source: “Vitruvian Man.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. March 29. Internet)

Fig 9 Artificially constructed Palm Island in Dubai, UAE.

Fig 9 Artificially constructed Palm Island in Dubai, UAE.

Fig 10. Concrete spikes under flyovers and bridges in Guangzhou China

Fig 10. Concrete spikes under flyovers and bridges in Guangzhou China