THE LEADING GLOBAL EVENT SERIES

SCALING

SAVE 20% WHEN BOOKING YOUR PASS TO ATTEND ANY SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUTURES EVENT BY USING OUR UNIQUE DISCOUNT CODE: SIMPLIFLYING_SAF20

SCALING

SAVE 20% WHEN BOOKING YOUR PASS TO ATTEND ANY SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUTURES EVENT BY USING OUR UNIQUE DISCOUNT CODE: SIMPLIFLYING_SAF20

For over 15 years, SimpliFlying has been a trusted partner to airlines, airports, and technology firms worldwide. We have been on a mission to help build trust in aviation. To empower the industry to soar to new heights through digitalisation, innovation, and a steadfast commitment to sustainability.

We're not just sought after strategy consultants, we are passionate advocates for meaningful change. Headquartered in Singapore, our global team based out of Canada, India, Spain and the UK is dedicated to equipping aviation and technology executives with the tools, insights, and strategies needed to navigate the complexities of sustainable aviation.

From major airlines and airports to aircraft manufacturers and travel technology companies, our extensive client base underscores our reputation as a trusted partner in the aviation industry since 2008.

Simpliflying are proud to partner with Sustainable Aviation Futures to bring you this special European focused report ahead of their congress taking place in Amsterdam from 21-23 May 2024.

At SimpliFlying, we're committed to helping you navigate the complexities of sustainable aviation and thrive in an ever-changing landscape. Here are some ways we can help you in your sustainability journey:

Like 80+ other CxOs in the industry, enlist your CEO or Head of Sustainability to be interviewed by Shashank Nigam. Share your vision for the future of travel on the world’s best-known sustainable aviation podcast "Sustainability in the Air". Find out more on becoming a partner.

Harness the power of our research and analysis with custom reports tailored to your unique objectives. We can help you build thought leadership on a particular topic that you would like to "own".

SimpliFlying has helped a multitude of technology firms scale up in aviation – from launching an airplane to marketing an Airbus A380 engine. We can help you amplify your brand and help build awareness with key decision-makers.

We deliver in-depth monthly or quarterly briefings to the senior leadership teams on a topic/issue of your choosing. You can also sign up for a series of briefings that cover key aspects of the present and future of sustainable aviation.

Our in-person workshops and virtual events can help you discover innovative ideas as you network with like-minded innovators, and unlock new opportunities.

Get in touch!

This report was prepared by Simpliflying for Sustainable Aviation Futures. All content and any reference to organisations included in the report is undertaken by Simpliflying and is independent of Sustainable Aviation Futures.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) has evolved from a mere option to a regulatory necessity for airlines, with mandates set to come into effect in the near future.

The ReFuel EU initiative is on the brink of implementation in the European Union. As soon as 2025, airlines will be obligated to blend a minimum of 2% SAF into their fuel mix, with this mandate expected to increase significantly to 6% by 2030.

Simultaneously, the UK is in the midst of a consultation phase that could require airlines to incorporate 10% SAF into their fuel mix by 2030.

These regulations pose substantial challenges, necessitating meticulous planning from 2024 to 2030 to ensure a smooth and gradual transition from fossil fuel-based jet fuel. This is especially critical, considering SAF currently comprises less than 1% of the total aviation fuel mix.

In conjunction with the upcoming Sustainable Aviation Futures EU Congress in Amsterdam, scheduled from 21 to 23 May 2024, we have prepared this comprehensive report to explore various SAF pathways and strategies for addressing the current significant gaps in the industry.

Specifically, this report will focus on:

• Analysing the mandates: The current status and the requirements for achieving compliance, providing a clear understanding of the regulatory landscape.

• Providing an overview of existing SAF production pathways: The various methods currently used to produce SAF, highlighting their advantages and limitations.

• Exploring innovative pathways: Cutting-edge approaches such as Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) and solar fuels, assessing their potential to revolutionise the SAF industry.

• Examining the perspective of environmental groups: We investigate the controversies surrounding SAF and why some question its sustainability, providing a balanced view of the ongoing debate.

• Discussing the intricacies involved in developing e-fuels: The challenges and opportunities associated with these advanced fuel types and the potential necessity of using nuclear energy as a power source.

• Addressing the funding challenge: The investment required to produce the necessary quantities of SAF in Europe and potential financing mechanisms, including the viability of SAF surcharges or frequent flyer levies.

• Providing a comprehensive directory of European SAF enterprises: A detailed list of companies operating in the European SAF sector, serving as a valuable resource for industry stakeholders.

This report aims to offer valuable insights and actionable strategies for airlines, policymakers, and industry stakeholders as they navigate the complex landscape of SAF implementation.

By providing a thorough analysis of the regulatory environment, exploring innovative production pathways, examining the perspectives of environmental groups, and addressing the funding challenges, this report will equip decision-makers with the knowledge and tools needed to meet the impending regulatory requirements while contributing to a more sustainable future for aviation.

As the industry stands at the precipice of a transformative era, this report serves as a vital resource for those seeking to understand the current state of SAF and the steps necessary to ensure its successful integration into the aviation sector. By embracing the challenges and opportunities SAF presents, the industry can pave the way for a greener, more sustainable future for air travel.

Dirk Singer Head of Sustainability, SimpliFlying dirk@simpliflying.com

Note on terminology: The terms e-fuels, electrofuels and Power-to-Liquid (PtL) are often used interchangeably to describe synthetic fuels produced using electricity from renewable sources. In section 3, we have used Power-to-Liquid (PtL) to describe the pathway but throughout the report, we have used “e-fuels” as a more user-friendly description of the fuel source.

The European Union and the UK are driving the adoption of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) through ambitious mandates. However, the industry faces significant adoption challenges, with SAF currently accounting for less than 1% of total aviation fuel.

The EU's ReFuelEU Aviation initiative mandates a minimum SAF blend of 2% by 2025 and 6% by 2030, while the UK is considering a 10% SAF requirement by 2030. Challenges include ensuring sustainable feedstock availability, scaling up production capacity, closing the cost gap, and financing SAF production.

Various pathways produce SAF, each with advantages and disadvantages. HEFASPK dominates due to wider feedstock availability and established technology but is controversial due to imported Used Cooking Oil (UCO). Other pathways include Alcohol-to-Jet (AtJ), Synthesised Iso-Paraffins (SIP), Methanol-to-Jet (MtJ), FischerTropsch (FT), Power-to-Liquid (PtL), Solar Fuels, and Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL), at varying maturity stages.

Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) and Solar Fuels are promising pathways that could revolutionise the sector. HTL converts wet biomass, including waste, into SAF, offering 90% CO2 lifecycle reductions. Solar Fuels harness solar energy directly for fuel production, potentially improving efficiency and reducing costs.

Environmental and climate groups criticise SAF for not addressing non-CO2 emissions and potentially delaying the transition to zero-emission solutions. Concerns exist around the sustainability of certain feedstocks and the potential for fraud. Critics argue that over-reliance on SAF may hinder investments in hydrogen or electric-based propulsion systems.

E-fuels, produced from green hydrogen and captured CO2, are a long-term SAF solution but face renewable energy challenges. Pink hydrogen, produced using nuclear energy for electrolysis, may offer a more cost-effective and efficient alternative.

Significant investments are required to build SAF refineries and bridge the cost gap with traditional jet fuel. Funding sources include government incentives, venture capital, private investors, bank debt, and contributions from corporate and individual passengers. Book-and-claim systems allow corporates to offset Scope 3 emissions by purchasing SAF. Frequent flyer taxes are also a potential financing mechanism.

The European Union and the UK are pushing forward with ambitious mandates to drive the adoption of SAF over the next two decades.

Global SAF production may have doubled to 600 million litres in 2023, but it still accounts for only 0.2% of global jet fuel use, with the majority produced in the United States, thanks to a combination of Federal and US State level incentives for SAF production.

To correct this imbalance and meet their wider climate goals, the EU and the United Kingdom intend to mandate the use of SAF, with the percentages used steadily increasing in the lead-up to 2050.

Source: Dan Fador

Source: Dan Fador

The EU's progressive ‘ReFuel’ mandate requires a minimum percentage of SAF blended with conventional jet fuel for all flights departing from EU airports, starting with 2% in 2025, increasing to 6% by 2030, and targeting 70% by 2050.

Notably, the mandate stipulates that a minimum of 1.2% of the SAF used in 2030 should come from e-fuels or power-to-liquid fuels, which are produced using renewable electricity and carbon captured from the atmosphere or industrial processes.

The ReFuel mandate's origins can be traced back to the European Commission's 2020 communication on a Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy, which aims to reduce transport-related greenhouse gas emissions by 90% by 2050.

It is, in turn, a key component of the EU's comprehensive "Fit for 55" package, a set of proposals aimed at reducing the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030

compared to 1990 levels. The package, unveiled in July 2021, seeks to align the EU's climate, energy, land use, transport, and taxation policies with its climate goals.

Not only does the ReFuel mandate contribute to the EU's broader efforts to combat climate change, but the aim is also to promote sustainable development.

As the demand for SAF increases, so will the need for sustainable feedstocks, production facilities, and infrastructure, opening up opportunities for innovation, investment, and regional development.

In fact, according to the European Commission, the development of SAF in the EU has the potential to create 200,000 new jobs

By setting clear targets and a timeline for SAF adoption, the mandate creates a stable and predictable market for SAF producers, encouraging investment and innovation in the field. The gradual increase in SAF blending percentages ensures a smooth transition for the industry, allowing time to develop more efficient and sustainable production methods.

Moreover, the ReFuel mandate can inspire other countries and regions to adopt similar measures, creating a ripple effect that accelerates the shift towards cleaner aviation worldwide.

Source: Kurt Bouda

Source: Kurt Bouda

The UK is pursuing a SAF mandate, with consultations discussing a minimum of 10% SAF blend by 2030, which aligns with the government's intention to make the mandate as ambitious as possible.

The belief is that the ambitious mandate will stimulate rapid growth in the UK's SAF industry, creating green jobs, attracting investments, and bolstering the country's competitiveness in the global market.

Furthermore, the UK's SAF mandate can contribute to developing a thriving domestic SAF supply chain, reducing the country's dependence on imported fossil fuels and enhancing its energy security.

While the EU and UK mandates share the common objective of decarbonising the aviation sector, significant hurdles remain:

Ensuring sufficient and sustainable feedstock availability is critical, as current methods rely on limited and controversial feedstocks like used cooking oil.

Scaling up SAF production capacity is necessary, as the current capacity in Europe is significantly lower than required to meet the mandates' targets. Europe risks falling behind, with the current maximum potential SAF production capacity in the EU estimated at only 10% of the amount needed to meet the 2030 mandate.

Closing the cost gap between SAF and conventional jet fuel is crucial for wider adoption by airlines.

Financing SAF production requires finding the right formula between government grants, venture capital funding, and bank loans underwritten by airline offtake agreements.

Despite these challenges, the EU and UK mandates provide a clear framework for addressing them head-on.

By creating a stable demand for SAF, the mandates incentivise the development of new, sustainable feedstocks and production methods. Governments can support this process by funding research and development, providing tax incentives, and facilitating stakeholder partnerships.

Moreover, as SAF production scales up to meet the mandates' targets, economies of scale can drive down costs, making SAF more competitive with conventional jet fuel. This, in turn, will encourage more airlines to adopt SAF, further accelerating its deployment and reducing the aviation sector's carbon footprint.

This next section explores the different pathways to achieve these targets.

SAF is currently being produced through various pathways, each with its own advantages, disadvantages, and level of maturity. Let's take a closer look at these SAF production methods:

• Feedstock: Used cooking oils, animal fats, plant oils

• Currently, the HEFA-SPK pathway is the predominant method for producing SAF due to the broad availability of feedstocks and the maturity of the technology. However, this approach has sparked controversy because of the importation of UCO from countries such as China, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Nonetheless, Airlines for Europe (A4E) states that, in the short term, "HEFA is the only viable solution".

• Feedstocks: Ethanol derived from sugars (sugarcane, sugar beets), starches (corn, grains), cellulosic biomass (wood waste, agricultural residues), or Butanol (ethyl alcohol) produced through fermentation or advanced chemical processes from biomass.

• The cost-effectiveness of AtJ compared to HEFA is debatable. In 2022, a rise in the cost of vegetable oil feedstocks made AtJ the cheaper pathway. However, currently, the cost of producing SAF via AtJ is believed to be higher than HEFA. AtJ has potential advantages, such as diverse feedstocks and room for efficiency improvements through ongoing technology development.

• Currently, only one AtJ facility is operational worldwide, the LanzaJet Freedom Pines Fuels facility in Soperton, Georgia. However, more AtJ plants are in development, including in Europe. For example, a Swedish company plans to bring 400,000 metric tons (approximately 130 million gallons) of SAF annually to the Swedish market by building three new AtJ plants, equating to around 40% of the annual jet fuel consumption at Stockholm's Arlanda Airport.

• SIP uses a similar array of feedstocks to AtJ but represents a newer pathway for producing SAF.

• SIP fuels are created through a process that typically involves the fermentation of sugars to produce an intermediate chemical (such as farnesene), which is then hydrogenated to form iso-paraffins. These isoparaffins are similar to conventional jet fuel, making SIP a promising option for SAF production.

• Feedstocks: Methanol is produced by gasifying biomass such as agricultural residues or municipal waste, or from captured CO2 and H2, similar to the PtL pathway.

• Although MtJ is still a relatively early-stage SAF pathway, advocates claim it is more efficient and less energy-intensive than other production methods.

• In the FT method, biomass (wood waste, agricultural residues, waste) is gasified, and the resulting syngas is used in the Fischer-Tropsch process to create SAF.

• FT is a well-established method for producing synthetic fuels, having been created in 1925.

• Companies turning municipal waste into SAF typically use FT. However, it is considered relatively inefficient, with 42% or more energy losses.

• Commonly known as e-fuels or electrofuels, the core idea is to use renewable electricity to produce liquid fuels.

• The basic ingredients are green hydrogen, made using renewable energy to split water (H2O) into hydrogen and air through electrolysis and captured CO2.

• The green hydrogen is combined with the captured CO2 to produce syngas, which is then put through a Fischer-Tropsch (FT) reactor to make jet fuel.

• Some e-fuel companies claim to have disrupted the FT process to create their own more efficient way of making e-fuels.

• PtL has several advantages, such as a CO2 lifecycle reduction of 90% or more (compared to 50-80% for other forms of SAF), less feedstock intensity, and the ability to be deployed in locations with abundant renewable energy and access to CO2 sources (industrial or direct-air capture).

• However, PtL also has disadvantages, including high costs due to capital and operating expenses and the need for vast amounts of renewable energy to be produced at scale. A report by the World Fund on 'Electrofuels for Aviation' projected that replacing just 8% of European aviation fuel with e-fuel by 2040 would necessitate the total electricity consumption of a country like Sweden or the Netherlands.

• Despite these challenges, policymakers are promoting and mandating the use of e-fuels. The European Union's ReFuelEU Aviation program requires jet fuel suppliers to include 1.2% of e-fuels in the overall fuel mix by 2030, increasing to 35% by 2050.

• This is a process that converts non-food biomass, such as agricultural residues (e.g. straw, corn stover), woody biomass (e.g., forest residues, sawdust), and energy crops (e.g., switchgrass, miscanthus), into synthetic jet fuel.

• This conversion process involves several key steps and can be achieved through various biochemical and thermochemical methods.

• Lignocellulosic biomass is tough to break down due to its tightly bound components. Pre-treatment helps to make the components more accessible.

• After pre-treatment, the cellulose and hemicellulose are broken down into simple sugars, often using enzymes.

• Microorganisms can then ferment the sugars to produce alcohols like ethanol or the entire biomass can be turned into syngas, which is then processed further.

• CHJ can process a wide range of feedstocks, including waste oils, fats, greases, and non-food biomass such as algae and wood waste.

• CHJ was developed by Applied Research Associates (ARA) and Chevron Lummus Global (CLG).

• It converts waste oils or other biomass into a high-quality bio-crude that can be co-processed with petroleum in existing refineries to produce SAF. The process is said to have a lower carbon intensity than HEFA.

• While CHJ shows promise as a SAF production pathway, it is still in the early stages of commercialisation and will require further investment and development.

• Pyrolysis is a thermochemical process that involves heating biomass in the absence of oxygen to produce a liquid bio-oil, which can then be upgraded to SAF.

• Pyrolysis can utilise a wide range of biomass feedstocks, including agricultural residues, forestry residues (e.g., wood chips, sawdust, bark), energy crops (e.g., miscanthus, switchgrass), municipal solid waste (e.g., paper, cardboard, organic waste)

• By utilising various waste streams, such as agricultural residues and municipal solid waste, pyrolysis can contribute to waste reduction.

• The solid residue (biochar) produced during pyrolysis provides additional value, as it can be used as a soil amendment or for other applications.

• Pyrolysis represents a promising pathway for SAF production, but further research and development are needed to address the challenges associated with bio-oil upgrading and improve the process's overall efficiency and economic viability.

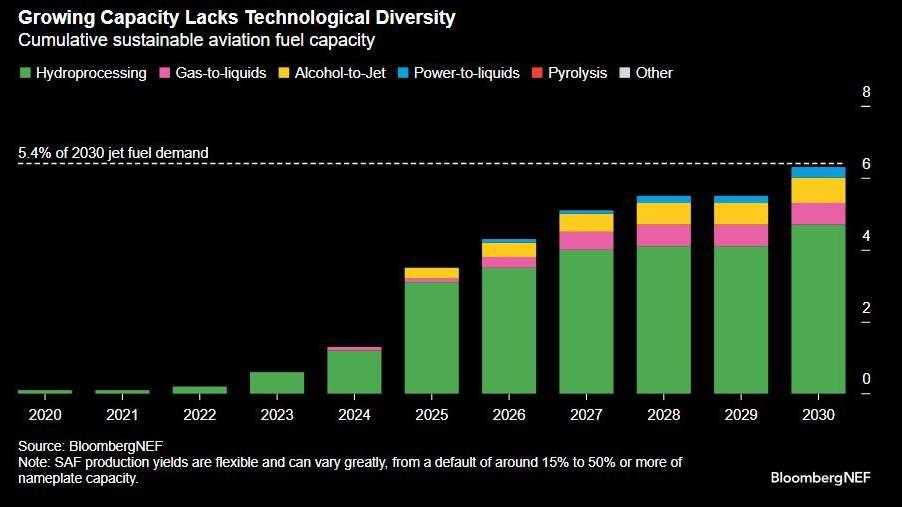

According to Bloomberg NEF, global SAF production capacity is set to surge 10-fold by 2030. However, currently HEFA is the dominant production pathway. By 2030, AtJ will only account for a small proportion of SAF supplies, with e-fuels accounting for even less.

Source: Bloomberg NEF

Source: Bloomberg NEF

This raises concerns about long-term scalability and diversification. Bloomberg NEF's 2024 SAF Outlook revealed that, given current feedstock limitations, HEFA can only satisfy about 4% of total jet fuel demand.

Not only are there concerns about where these feedstocks come from – with European countries now importing UCO from China, Malaysia and Indonesia – the industry risks hitting a growth ceiling unless it can tap into new feedstock sources and develop alternative production methods.

As a result, to truly take flight, the SAF sector must look beyond HEFA and prioritise research and development into next-generation pathways.

Commercialising these emerging technologies will be critical to diversifying the industry's feedstock base and achieving the scale required to make a meaningful dent in aviation emissions. While HEFA has provided a solid launchpad, sustained innovation and investment will be the engines that give the industry the volume of SAF it needs to meet its net-zero targets.

While much attention has been focused on HEFA, AtJ, and e-fuels, two other promising pathways are worth exploring: Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) and Solar Fuels.

HTL is a process that converts biomass into a liquid biocrude under high-pressure and high-temperature aqueous conditions. The beauty of HTL lies in its ability to utilise a wide array of feedstocks, including municipal waste, agricultural waste, algae, and even sewage.

UK start-up Firefly Green Fuels, backed by Wizz Air, is focusing on sewage as a feedstock. CEO James Hygate sees it as a "ubiquitous, abundant, and incredibly costeffective" resource.

HTL-derived SAF offers impressive CO2 lifecycle reductions of 90%, surpassing HEFA-based SAF, it also transforms a waste and public health hazard into a valuable commodity.

Firefly's solution is highly scalable, as sewage is readily available worldwide, and SAF facilities can be strategically located beside sewage treatment plants.

Denmark's Steeper Energy is another European company making significant strides in commercialising HTL technology.

Their proprietary Hydrofaction process efficiently converts various biomass feedstocks into renewable oil, recovering 85% of the input energy in the resulting biocrude, which can then be refined into SAF, marine fuels, and biochemicals.

Steeper Energy has partnered with Silva Green Fuel in Norway to build a demonstration plant showcasing the Hydrofaction technology's ability to produce renewable crude oil from wood residues. They have also signed an MOU with the city of Calgary, Canada, to process a portion of the city's sewage sludge into advanced biofuels.

Source: Firefly Green Fuels

Source: Jody Davis

Solar Fuels represent another exciting pathway, directly converting solar energy into chemical energy. While often considered a type of e-fuel, Solar Fuels differ in several key aspects:

Energy source: Solar fuels harness solar energy directly, while e-fuels fuels use sustainable electricity as an intermediate step.

Production process: Solar Fuels are produced through photobiological or artificial photosynthesis processes, whereas e-fuels require electricity to produce hydrogen which is then used to synthesise liquid fuels.

Efficiency: Solar fuels have the potential for higher overall efficiency due to the direct conversion of solar energy into fuels, compared to e-fuels, which involve multiple conversion steps.

Switzerland's Synhelion is at the forefront of Solar Fuel development, using a process they call "reverse combustion." By recombining water vapour and CO2 using solar heat, Synhelion's technology mirrors the reverse of conventional fuel combustion.

The company aims to achieve cost competitiveness with traditional jet fuel by 2030, targeting a production cost below €1 per litre. With current jet fuel prices around €0.66 per litre, Synhelion is poised to narrow the gap between solar and conventional jet fuel significantly.

Synhelion partnered with the Lufthansa Group in 2020 and is developing its 'DAWN' commercial plant in Germany.

As the aviation industry strives to embrace sustainability, exploring innovative SAF pathways like HTL and Solar Fuels is crucial. These technologies offer the potential for significant CO2 reductions, transform waste into valuable resources, and harness the sun's power. With continued investment and development, HTL and Solar Fuels could play a vital role in shaping the future of sustainable aviation.

The historic Virgin Atlantic flight on November 28, 2023, which used 100% SAF to cross the Atlantic, was a watershed moment for the industry. However, it also sparked criticism from environmental and climate groups, who claimed that the flight offered a false sense of sustainability.

Cait Hewitt of the Aviation Environment Federation called the idea of guilt-free flying "a joke," while pressure group Safe Landing dismissed the flight as a publicity stunt to lobby for more public money and subsidies for SAF.

Why do these groups object to SAF? There are three main areas of criticism:

The sustainability of SAF

Issues surrounding SAF feedstocks Claims

The Aviation Environment Federation (AEF) casts doubt on the sustainability of SAF. In their paper, "Sustainable Aviation Fuels - Hope or Hype?" they argue that the term 'SAF' has rebranded all biofuels and synthetic fuels as 'sustainable.'

AEF's Cait Hewitt has even compared SAF to carbon offsets, as the fuel emits the same amount of CO2 as kerosene when burned in an aircraft.

Hewitt emphasised the need for careful carbon accounting and pointed out that SAF does not address non-CO2 emissions, such as contrails and nitrogen oxides (NOx).

While the AEF acknowledges the value of keeping fossil fuels in the ground, they conclude that more research is needed and not all types of SAF should be treated equally.

That said, SAF can reduce life cycle GHG emissions dramatically compared to conventional jet fuel, and it is seen as a key pillar which will drive the industry towards achieving its net zero objectives.

Source: Virgin Atlantic

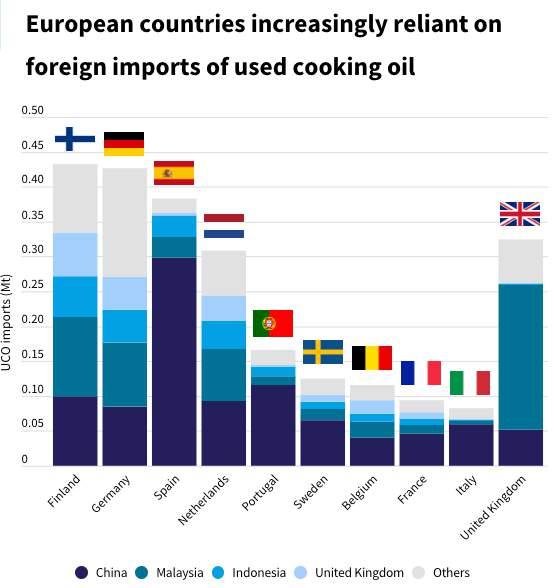

The AEF and Brussels-based environmental think-tank Transport & Environment (T&E) are two groups that have expressed concern about HEFA-based feedstocks.

Source: Transport & Environment, based on data from Comtrade (2023)

T&E has revealed that the demand for UCO for biofuels has led to massive imports from countries like China, as Europe's domestic production is insufficient. This raises issues of transportation emissions and the risk of palm oil being added to the mix.

Another point of contention is the potential use of land for fuel crops instead of food crops. Environmental group

Stay Grounded asserts that biofuels can cause serious environmental and social impacts, such as biodiversity loss, rising food prices, and water scarcity.

Even Ryanair CEO Michael O'Leary agrees, stating, "The idea that you grow food at great cost and turn it into fuel is just nuts."

T&E advocates for using e-fuels, but these come with their own controversies, as producing e-fuels requires vast amounts of renewable energy that could arguably be deployed more effectively elsewhere.

In our book ‘Sustainability in the Air’, Dr Susanne Becken, Professor of Sustainable Tourism at Griffith University, warned that if aviation "grabs all the clean energy so that aviation is net-zero by 2050, there will be nothing left for anyone else, delivering an overall worse outcome than had it just given it to the electricity sector."

Meanwhile, in an episode of the Land & Climate Podcast, Finlay Asher from Safe Landing called e-fuel-powered flights “probably the most inefficient thing you could do bar putting it into a rocket and sending Jeff Bezos into outer space.” 1

1 McEwan, Alasdair, “Is there any hope for a green aviation industry?”, September 23, 2022, Land & Climate Review, interview with Finlay Asher, podcast, https://www.buzzsprout.com/1695859/11372779

Many environmental campaigners are concerned that an overreliance on SAF may delay investments in entirely new technologies – such as hydrogen or electric-based propulsion systems.

Interestingly, some argue that aviation should just drop the use of SAF and continue using fossil fuels while the development of hydrogen and electric aircraft is ongoing.

Finlay Asher of Safe Landing said that in this scenario, the industry would "burn less and less every year, and slowly your electric and your hydrogen and some alternative fuels in limited quantities will start replacing those. That's kind of the conclusion that I end up at."

Dr. Susanne Becken concurs with Asher's assessment. "In some ways, It would make much more sense to let aviation have the kerosene and decarbonise everything else to get the biggest bang for the buck." Like Asher, Dr Becken believes this change would need to be coupled with limits on aviation growth and a potential reduction in yearly flights.

Source: SimpliFlying

As the debate around SAF continues, it is essential to address these controversies and ensure that the industry's sustainability efforts are genuine, effective, and transparent.

As the aviation industry explores e-fuels as a long-term SAF solution, concerns have been raised about the resources required to produce green hydrogen, a key ingredient in e-fuels.

Lufthansa CEO Carsten Spohr noted that powering the airline via e-fuels would consume half of Germany's entire electricity production, a reality that the government is unlikely to support.

Moreover, airlines aren't the only ones interested in e-fuels; the automotive industry sees them as an alternative to electric cars. With companies like Porsche setting up their own e-fuel plants, finding sufficient renewable energy to produce e-fuels within Europe will be a daunting challenge.

Two potential solutions have emerged:

Locate e-fuel plants in regions with abundant and cheap solar energy and land, or Consider nuclear power as the energy source instead of wind and solar

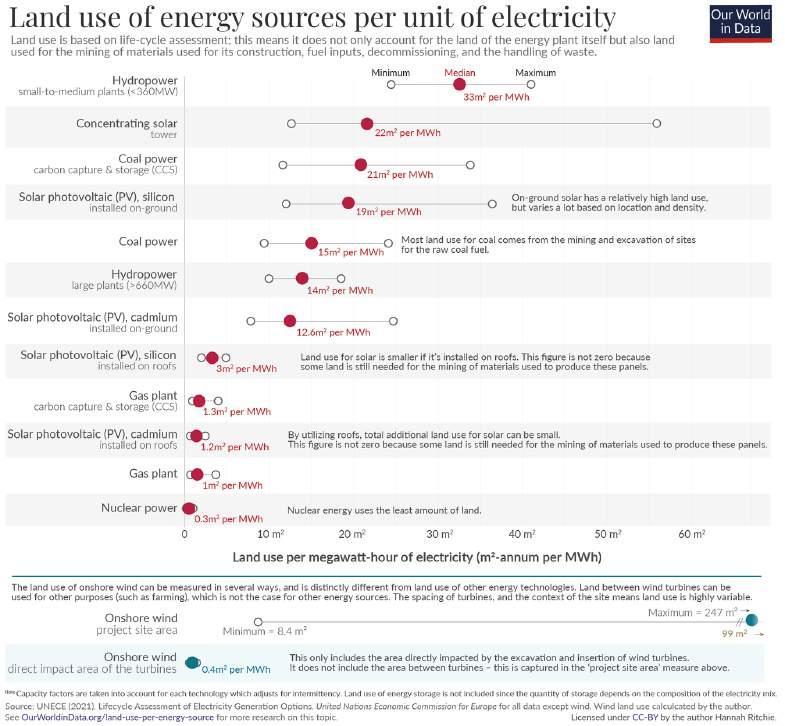

Source: Our World in Data

Pink hydrogen is produced using nuclear energy for electrolysis, offering several advantages over green hydrogen:

Zero-carbon: Nuclear power is a zero-carbon energy source.

Constant power: Unlike wind and solar, which are weather-dependent, nuclear provides a constant power source.

Land efficiency: Nuclear is the most land-efficient energy source, requiring 50 times less land than coal and 18 to 27 times less than on-ground solar PV.

Cost-effectiveness: Pink hydrogen is cheaper than green hydrogen, with unsubsidised pink hydrogen costing as little as €2.50/kg compared to €3.20-€7 for green hydrogen.

Efficiency: Pink hydrogen plants have the potential to produce 63% more hydrogen than green hydrogen plants.

Despite these advantages, nuclear power has an image problem due to incidents like Fukushima and Chernobyl. However, Alasdair Lumsden, Co-Founder of UK-based Carbon Neutral Fuels (CNF), points out that nuclear technology has advanced considerably since these incidents involved reactors built in the 1960s or earlier.

Lumsden believes that a new generation of nuclear reactors, such as Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs), which offer enhanced safety features, could generate fossil-fuel-free hydrogen. This pink hydrogen could then serve as a key ingredient in producing e-fuels.

This idea has received support from notable figures like Emirates CEO Sir Tim Clark, who believes nuclear energy must be considered the key to unlocking aviation decarbonisation.

Sir Tim will be a keynote speaker at the Sustainable Aviation Futures EU Congress and we look forward to him elaborating on these points during the event.

As the industry continues to explore e-fuels as a long-term SAF solution, the potential of pink hydrogen derived from nuclear energy may need to be seriously considered to address the challenges associated with green hydrogen production.

Source: AZoCleantech

Financing the development and production of SAF is one of the biggest obstacles to its widespread adoption. According to SkyNRG, Europe alone will require an investment of €250 billion to build 150 SAF refineries by 2050, with each facility costing an average of €1.66 billion.

Other SAF companies have reported that a minimum of $500 million is needed to bring a single plant to commercialisation, a process that can take anywhere from 3-10 years.

Airlines also face the challenge of higher costs associated with SAF, which can range from 2 to 5 times the price of traditional jet fuel. This raises the question: how can the industry secure the necessary funding to make SAF a viable and widespread solution?

Source: Dealroom.co

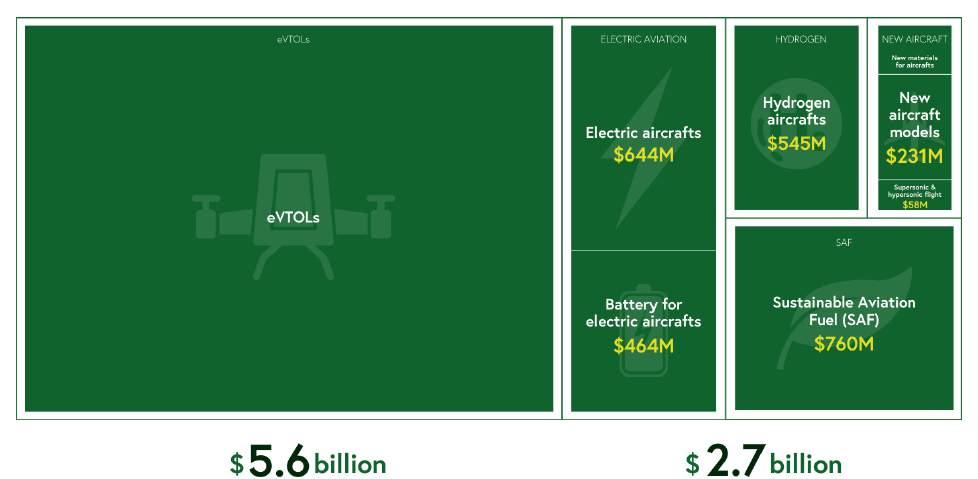

Interestingly, data from Dealroom.co reveals that while there is money in the sustainable aviation space, there are question marks about where it is going. In particular, electric vertical takeoff and landing vehicles (eVTOLs) have raised twice as much money as the rest of the combined sustainable aviation space, including SAF.

While these electric air taxi makers make various claims about their utility, they are primarily designed for short urban routes. They are unlikely to impact the industry's overall carbon emissions significantly.

In contrast, for long-haul flights, which generate 50% of the industry's emissions in Europe despite representing only 6% of total flights, SAF is the only viable medium-term solution.

To bridge the funding gap, the industry must consider government incentives, venture and private capital, bank debt, and contributions from corporate and individual passengers.

• Governments are stepping up to support SAF production, with the UK committing to a revenue certainty mechanism and the EU using the Emissions Trading System (ETS) to part-fund the bloc's Innovation Fund. However, the European Commission should consider improving its SAF incentives to compete with the US Inflation Reduction Act.

• Venture capital funds and private investors also play a crucial role in funding SAF projects, often working in tandem with bank debt to finance the construction of production facilities. Airlines like United Airlines have created their own Sustainable Flight Funds to invest in and purchase SAF, providing a potential model for European carriers.

• Corporate customers are increasingly using book-and-claim systems to offset their Scope 3 emissions from business travel by purchasing the equivalent amount of SAF, which can help finance airline SAF purchases. Companies like Neste have unveiled programs allowing corporations to buy SAF through a book-and-claim system, enabling organisations to set their own sustainability targets and determine how much SAF they need to buy to achieve these goals.

• Finally, there are calls for the aviation industry to consider frequent flyer taxes, where those who fly the most contribute under the 'polluter pays' principle.

• For example, the International Council for Clean Transportation (ICCT) has proposed a global frequent flyer levy to raise 81% of the $4 trillion needed for aviation decarbonisation, according to ICAO. Under this proposal, those who fly more often would pay more, with the first flight each year being free and subsequent flights incurring a levy ranging from $9 to $177.

• The idea behind the ICCT's proposal is to generate revenue rather than 'punish' people for flying, and the sliding scale accounts for the fact that the levy would be paid primarily by affluent individuals in developed countries, matching historical carbon emissions. The ICCT admits that the logistics behind such a scheme are very difficult but could be possible through industry bodies like IATA in the future, despite potential opposition.

As public tolerance for polluting industries decreases, aviation may need to adopt more radical measures to maintain public trust and secure the necessary funding for the widespread adoption of SAF.

Accurate as of March 2024. Please note we seek to be as accurate as possible with this list, but acknowledge that the industry is constantly changing. If you believe an organisation is missing or an amendment is required, please contact us directly.

Agrisoma

Founded: 1956

Country: Austria agrisoma.com

Ørsted

Founded: 2006

Country: Denmark orsted.com

OMV Group

Founded: 1956

Country: Austria omv.com

Steeper Energy

Founded: 2011

Country: Denmark steeperenergy.com

Topsoe

Founded: 1940

Country: Denmark topsoe.com

Neste

Founded: 1948

Country: Finland neste.com

Axens

Founded: 2001

Country: France

Engie (ReUze)

Founded: 2008

Country: France

Kaidi

Founded: 2016

Country: Finland kaidi.fi

UPM Biofuels

Founded: 1996

Country: Finland upmbiofuels.com

Elyse Energy

Founded: 2020

Country: France elyse.energy

Country: France axens.net reuze.eu h2v.net

H2V

Founded: 2016

Founded: 1993

Country: France

haffner-energy.com

Founded: 1992

Country: France

aviation.totalenergies.com

Founded: 2021

Country: France

investors.technipenergies.com

Caphenia

Founded: 2011

Country: Germany

caphenia.tech

Founded: 1991

Country: Germany

edl.poerner.de

Founded: 2011

Country: Germany

Founded: 2005

Country: Germany atmosfair.de

Founded: 2016

Country: Germany

interatec.de

Founded: 1998

Country: Germany

saria.com

Founded: 2016

Founded: 2022

HQ: USA

weflywright.com

Country: Germany colipi.com

Founded: 1998

enertrag.com

Founded: 2017

Country: Germany

Country: Germany h-c-s-group.com

hy2gen.com

Founded: 2021

Country: Germany

p2x-europe.com

Founded: 2020

Country: Germany

siemens-energy.com

Founded: 2021

Country: Germany sparkefuels.com

Founded: 2016

Country: Germany

uniper.energy

Founded: 2018

Country: Ireland tessomotechnologies.com

Eni

Founded: 1953

Country: Italy eni.com

Founded: 2019

HQ: Norway norsk-e-fuel.com

Founded: 1953

Country: Portugal

Sunfire

Founded: 2010

Country: Germany sunfire.de

IðunnH2

Founded: 2020

Country: Iceland idunnnh2.com

Founded: 2010

Country: Ireland xfuel.com

Nordic Electrofuel

Founded: 2015

Country: Norway nordicelectrofuel.no

Founded: 2015

Country: Norway

Abengoa

renewable-carbon.eu/news statkraft.com

Founded: 1941

Country: Spain

abengoa.com

Cepsa

Founded: 1929

Country: Spain aviation.cepsa.com

Greenalia

Founded: 2013

Country: Spain

greenalia.es

Repsol

Founded: 1986

Country: Spain

repsol.com

Preem

Founded: 1994

Country: Sweden

preem.se

St1

Founded: 1995

Country: Sweden st1.com

Founded: 1909

Country: Sweden group.vattenfall.com

Synhelion

Founded: 2016

Countyr: Switzerland synhelion.com

Sasol

Founded: 1950

Colabit

Founded: 2013

Country: Sweden

colabit.com

Founded: 2017

Country: Sweden

sca.com

Founded: 2000

Country: Sweden swedishbiofuels.com

Country: SA / GER / DEN / SWDN sasol.com

Founded: 2021

Country: Switzerland metafuels.ch

Founded: 2012

Country: Switzerland varoenergy.com

Founded: 1896

Country: The Netherlands shvenergy.com

SkyNRG

Founded: 2009

Country: The Netherlands skynrg.com

Founded: 1923

Country: United Kingdom avioxx.co.uk

air BP

Founded: 1909

Country: United Kingdom bp.com

Circulairity

Founded: 2023

Country: United Kingdom

-

Johnson Matthey

Founded: 1817

Country: United Kingdom matthey.com

OXCCU

Founded: 2021

Country: United Kingdom

oxccu.com

Sustineri Fuels

Founded: 2020

Country: United Kingdom sustinerifuels.com

Willis Sustainable Fuels

Founded: 2022

Country: United Kingdom willissustainablefuels.com

Alfanar Energy

Founded: 2021

Country: Saudi Arabia / UK safinvestor.com

Carbon Neutral Fuels

Founded: 2022

Country: United Kingdom cnf.energy

Firefly Green Fuels

Founded: 2022

Country: United Kingdom firefly.uk

Nova Pangea Technologies

Founded: 2008

HQ: UK novapangea.com

Shell Aviation

Founded: 1921

Country: United Kingdom shell.com

Velocys

Founded: 2004

Country: United Kingdom velocys.com

Zero

Founded: 2020

Country: United Kingdom

zero.co

GEVO

Founded: 2005

Country: USA / France gevo.com

CLG (Chevron Lummus Global)

Founded: 2000

chevronlummus.com

Fulcrum BioEnergy

Founded: 2007

Country: USA / UK

Country: USA / Poland fulcrum-bioenergy.com

Infinium (ReUze)

Founded: 2020

Country: USA / UK

reuze.eu

LanzaTech (Project Dragon, FLITE)

Founded: 2005

Country: USA / UK lanzadragon.wales

Zenith Energy Terminals

Founded: 1927

Country: USA / UK zenithterminals.com

LanzaJet (Project Speedbird)

Founded: 2020

Country: USA / UK

lanzajet.com/news

Phillips 66 (Humber Refinery)

Founded: 1927

Country: USA / UK phillips66.com

Arcadia eFuels (NABOO, Endor)

Founded: 2021

HQ: Denmark arcadiaefuels.com

Hosted by SimpliFlying CEO and Founder Shashank Nigam, Sustainability in the Air is the world’s leading sustainable aviation podcast.

Over the past year, aviation guests have included Scott Kirby (United Airlines), Marie Owens Thomsen (IATA), Tim Clark (Emirates), Amelia DeLuca (Delta Air Lines), Amy Burr (JetBlue Ventures), Adam Goldstein (Archer), Bonny Simi (Joby) and Nathan Millecam (Electric Power Systems).

Listen and subscribe to the podcast here:

green.simpliflying.com/podcast

See other episodes

Meanwhile, our Sustainability in the Air website includes weekly articles on sustainable aviation tech startups; reports on subjects as diverse as SAF and eVTOLs; and regular newsletters read by thousands of industry professionals to understand the ever-evolving space of sustainable aviation and the industry’s potential pathways to net zero by 2050.

Climate change concerns are making the aviation industry turn to sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), electric, and hydrogen-powered aircraft to cut emissions. However, scaling these technologies requires significant innovation.

Sustainability in the Air highlights the journeys of entrepreneurs, executives, and investors who are navigating these challenges and paving the way for the future of aviation.

Learn more at sustainabilityintheair.com