Sink Hollow IssueXIV

Reader,

Welcome to Issue XIV of Sink Hollow. This pocket of time, now hidden between the pages of this digital collection, is our call into oblivion. I have been beyond grateful to work with the Sink Hollow staff in the previous years, and hope you understand the amount of effort put into each publication we send into the world. We seek out writing that will stand the test of time—that will still call and stun even when all else has fallen to dust.

In the aftermath of 2020, we are all learning to reconnect. And here, in these pages, we hear the cry of those calling from abandoned places. Writers and artists across time have always found a home within each other. Now we hope they will find a home within you.

Take care in the following pages and on your own journey.

Hannah Lee Editor-in-Chief

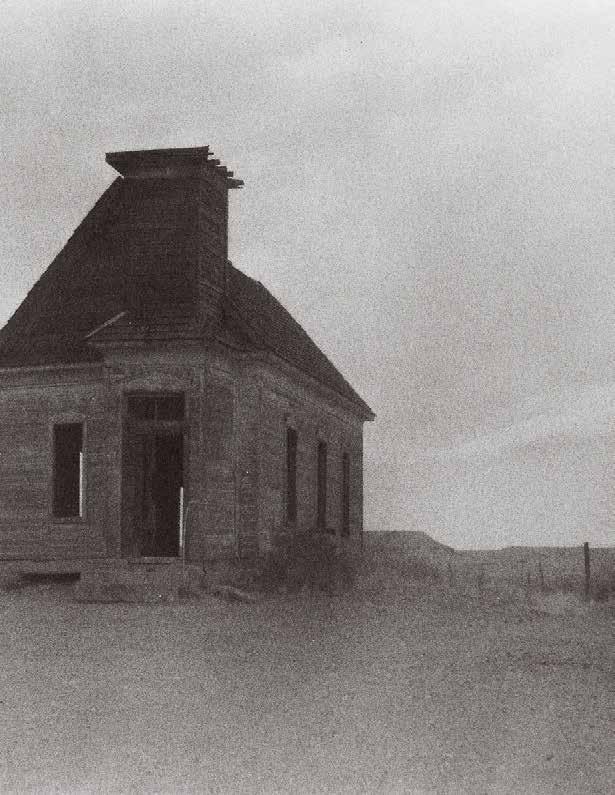

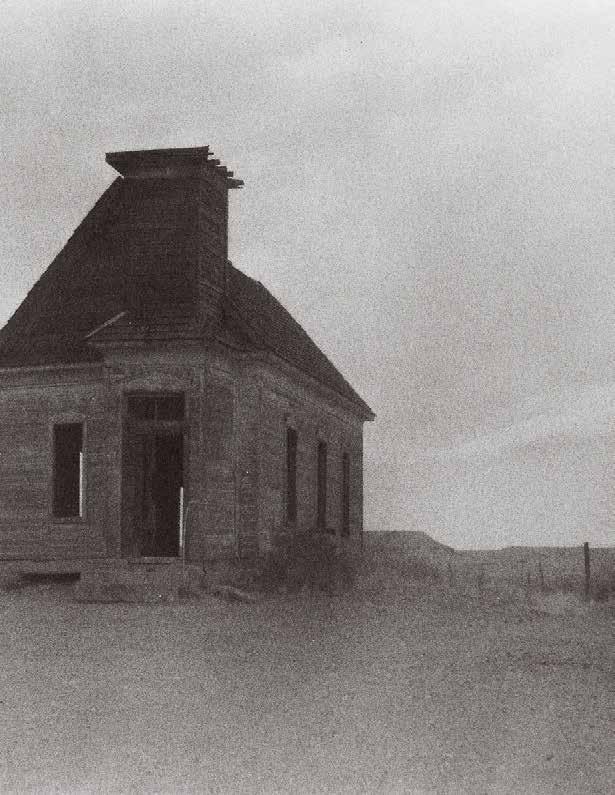

by Bailey Rigby

by Bailey Rigby

1-

The plateaus to the west are lit from within; The sun beats down, through the window, on me. I hung streamers from the car ceiling

Because she told me she didn’t want to leave the way she came, Covered in the desert dust and spooned all out. I’d made the venture before, sloping down the yellow-striped corridors, the marble-rusted walls, Watched the sun rise and set against an empty horizon with a pounding ache, This day is different: sun doesn’t swell (explode out of singed skin) but flickers like a tongue. Maybe this is the desolate desert’s gift. So I have a boot up, a hand on the wheel–

The streamers make patches of light, all purple and blue, on the passenger seat–And tell myself it is a good day, Because my sister is coming home.

2For weeks,

In my dreams, I filled a dried up river with buckets of my own water. In the wake of winter mornings, a prayer hung in the air, rang like an untouched bell, Sounded like her name.

And I window-watched the barren white

I wished there was a stronger word for I love you, one only she and I knew. And called to the Oaks and Cottonwood (dead) under another empty sky And waited (upon patient waiting) for the barren month to pass– its frigid hands held her answer, Arthritic and aching fingers cupped it closed.

Waiting (always patiently waiting) for the new year to Water dead dirt, bloom and unclasp.

I walk up the gravel pass, While the sun dances in warm circles on my shoulders, And prepare for a blast, a flood. But she comes to me with a smile on her face, Monarchs and Swallowtails kissing her goodbye, And says it is all up from here. Even in this space where nothing should grow, here you are, growing for no one but yourself. We pack up her boxes of last month’s life, Contemplate about how echoes never sound the same as the dusty call, say farewell to the valley, the cacti, the hum in the cracks of the Earth carrying its people to peace. Into the mesa, a deep breath, every dashed line taking us farther from an old truth, She tells me her new one–She is Free like the Brittlebushes, The Desert Marigolds, Or Rock Daisy–Free.

My mother wanted to be a lawyer, She went to school and learned how to speak, But they cut out her tongue and told her to read the future. She became a fortune teller, and she held a crystal ball Like it was a baby, clutched to her chest, But they cut off her hands and told her to be a mother. So her children, we learned to read each other’s palms, Read the future and pressed our hands together

Like it was a prayer. We found her old crystal ball and stared into it, but We only saw our pink mouths like open wounds, Our tongues like small animals. So she cut out our eyes And begged us to rot here with her.

I ask, do you ever wonder about the tunnels that pulse beneath us?

Only I don’t say it like that.

Really, I say, how weird that there’s a whole sewer system underground? And you say, it’s like an inner world vibrating and alive. But really, you say, it’s crazy because anything could be down there. And I agree.

Then later, I look at you and say, there’s a world beneath your eyes. But really, I don’t say anything. And you say, I like you. But I don’t know what that means.

Runoff down the old wood trail, A mess born of springtime showers.

Rushing whispers of a tale Of snowfall then of flowers. Petrichor and budding blooms, Speckled sunlight, passing clouds. Life left frozen now resumes Colors bursting back in crowds. All is fresh in sodden rain, Albeit cold and more than soaked. Stubborn roots and stones remain Deep and heavy, unprovoked.

I am not a Woman Im a God

It was the boring part of the Fourth of July, when the sun is still out and there’s nothing to do except will it to go away. I buzzed with excitement, waiting for darkness to fall over my neighborhood so fireworks could scrape across the sky. This was two years before my neighborhood got run out in a series of layoffs, divorces, and delusions of grandeur, which meant I could still go outside and talk to kids my age.

Across the cul-de-sac from my house were the Grahams, whose father worked as a garbage man and whose mother sold essential oils. They had three dogs, two cats, two hermit crabs, eight chickens, three stickbugs, a chameleon, and a one-hundred-year-old tortoise. The state of their lawn matched the state of their house, which was to say it was overgrown and covered in trash. Their daughter, Mackenzie, was a month older than me and the inheritor of the bad attitude that plagues all ten-year-old girls who do pageant shows and win them.

To the west of my house was a rolling field, and to the east were the Cooks. Their stepfather, named Matthew but known by everyone as Bubba, owned a car dealership and cared about his lawn like a third child. Their mother, Cheray, worked as a caterer-slash-DJ and was the first person to let me watch an R-rated movie. Their house had a basement and a second floor, which in our neighborhood meant that they lived in Buckingham Palace, complete with an automated garage door and a TV in every room, and Bubba kept every TV when Cheray and the girls moved out after they broke up on Valentine’s Day in 2015. Kaylee was four years older than me, the only high schooler I knew. Her advice when I

went to high school was to steal condoms from my parents instead of buying them myself. India was going into seventh grade in September and was named after her biological father’s ex-girlfriend, and if she had told me to walk in a straight line until I fell off the edge of the earth, I’d have asked her which direction she wanted me to walk in.

I loved those summers with the Grahams and the Cooks. I went to a different elementary school than Mackenzie, and the Cooks were already in middle school and high school. I had trouble making friends at school, where everyone had already paired up with each other, so during recess, I’d sit in the far corner of the playground and watch cars through the fence for an hour until the playground aid would blow the whistle and we all shuffled back inside. During the school year, my neighbors were busy, the Cooks doing homework or chores, and the Grahams deciding what mascara the judges would like best. During the summer though, they’d knock on my door and ask me to play with them. We’d jump on trampolines, where I could do the best backflips. We’d ride our bikes, where I knew to ride with only one hand. We’d watch movies in Bubba’s basement, and I would make the popcorn because I’d figured out exactly how much time would pop all the kernels without burning anything. I wasn’t alone on the playground, watching cars because no one wanted to go on the swings with me. I was their friend. It was four in the afternoon on the Fourth of July. I would turn ten next month, and India had warned me already about all the fifth-grade teachers, which ones were cantankerous bitches that gave out too much homework and which ones let

you pick your own seats. She had knocked on my door to see if I wanted to hang out with her, her sister, and Mackenzie until it was dark enough for fireworks. I was out the door with my shoes on before she’d finished asking. We cut across my lawn to hers. It was easy to see where our lawn ended and where Bubba’s began, the crisp line of his lush, bright green grass that he mowed every week standing dignified next to our wilting brown weeds. I loved it when we would play on Bubba’s lawn; the Grahams had no grass to speak of, and ours was dried and filled with creepy crawlies. Bubba’s lawn was soft and coated with every pesticide known to man. Kaylee and Mackenzie were already sitting by Cheray’s flowerbeds, lounging around and talking. When India and I got there, we didn’t sit down. India kept me standing as she looked to Kaylee and asked, “Can we play rocketship with them?” Rocketship was a game India and Kaylee had concocted with their cousins on a trip they’d taken earlier in the summer. Mackenzie and I watched as Kaylee laid back on the grass and brought her knees into her chest, leaving her feet open for India to sit on. Kaylee brought her legs back farther until India’s feet weren’t touching the ground, India’s arms crossed over her chest until Kaylee pushed off, and we watched India fly. She landed on her feet and turned toward us with a flourish.

“That’s rocketship.”

Mackenzie rushed to sit on Kaylee’s feet and flew, except she was twenty pounds heavier than the rest of us and didn’t go nearly as far as India had.

“Are you going to do it, Steph?”

India was asking me, looking directly into my eyes. It unnerved me then, when she’d look into my eyes. She had a pale face and light brown hair that went down to her waist, and the biggest, darkest eyes I’d ever seen. They were like two black holes, drawing in all matter. I was nine years old, not ten until next month, and knew nothing about black holes, just that rocketship looked fun and that India wanted me to do it, so I would. I nodded, going to sit on Kaylee’s feet.

They were warm under me. Strong, too. I was the youngest of the five of us, the smallest too, and it was the first time I’d seen a girl support someone’s entire body weight. I crossed my arms over my chest, the way we did sit-ups in gym class and leaned back in anticipation. India had gone so high, had whooped with such delight. I loved doing anything that would put me in the air. I’d climb to the top of park swingsets, staring down at all the kids that had come to watch. I’d climb ladders to bring shingles up to my dad while he worked on our roof and I’d walk around on top of our house until my mom told me to get down. I’d climb to the top of the trees in our lawn and dangle upside down by my knees while all my neighbors stared up at me. No one else could get as far up as I could.

When Kaylee pushed me off of her feet, my stomach lurched. It felt like the drop on the rollercoasters I was just getting tall enough to ride. It felt like I was flying, the way I could in my dreams sometimes. It was elating, it was dizzying, it was incredible, it was nauseating, it was wonderful, it was ending. On the airplanes we’d take to see my mom’s family, the pilot told us when we were landing, and my mom would make sure my seatbelt was fastened, holding my hand as we dropped out of the sky. When I dropped out of the sky onto my neighbor’s lawn on the Fourth of July, there was no pilot to warn me, no seatbelt to keep me in place, and my mom wasn’t holding my hand, so I fell right on it. Sixty pounds of an almost-ten-year-old girl plus the force of gravity on my left wrist. I felt it as it happened, a pop! in my wrist that radiated out over my body, whitehot heat following, like the crack of a firework before a fiery flower paints the sky. I remember swallowing down the shock, trying and failing to bite back the tears as I stared up at the blue sky, Bubba’s perfect lawn cool and damp against my back, Kaylee’s concerned voice washed out over the pounding in my ears, a sickening pop! pop! pop! still sounding in my head.

Someone went and got my parents. Someone went inside and told Bubba and Cheray, who

brought me ice and kept me calm until I was able to stand up. Someone walked me home and sat me on my bed. I only cried a little bit. It was the worst pain of my life, but I didn’t want to be seen as a crybaby, didn’t want to upset them. If I cried how I wanted, they’d see that I wasn’t as fun or as brave as they had thought, and when we started middle school in the fall, Mackenzie would decide I was too lame, India would decide I was too young, and I’d be stuck watching cars again. When the pain had subsided slightly and I could no longer hear the squelch of my bones bending and my tendons being forced backward playing over and over in my head, India came over. She brought me a slice of red velvet cake. Bubba and Cheray were going to serve it while they set off fireworks, but felt sorry for me and let me have some early. She also brought an old brace of Kaylee’s to keep my wrist steady until we could go into Urgent Care the next day. If I was up for it, she said, I could still come over and watch fireworks. Bubba always bought the most expensive fireworks, ones that could shoot out hundreds of little artilleries at a time, the ones that made the biggest explosions. Sniffling, I tugged the brace on. I walked with India, carefully, back across my lawn to her backyard. She had her arm linked in mine to keep me steady, so I wouldn’t fall and hurt myself more.

I sat on a bench in the Cooks’ backyard while I ate another slice of cake with one hand as Bubba dug into his mountain of explosives. In the stretch of sky our neighborhood could see, he was the first one to start setting off fireworks and the last one to finish. I watched as Roman candles, rockets, and barrages went off, one after the other for hours, and all of them went pop! before the fire bloomed out of them. My wrist ached, low but sharp, with each one. The group of people at the house, adults that Bubba and Cheray knew, kept their eyes fixed on the fireworks. They couldn’t look away. Earlier, on the grass, everyone had their eyes fixed on me. Even now, with the display going, the Cooks couldn’t look away from me. Bubba asked me which firework he should

set off next. Kaylee got a blanket from inside the second I started to shiver. India and her mother would regularly come sit with me on the bench, seeing how I was feeling. My wrist hurt more than anything had ever hurt me in my life, but I felt incredible. I watched our fireworks, the ones from surrounding houses as well, but I had four people who were only looking at me. It felt like there had been a big test and I’d passed, and the fireworks were my reward for being brave, like everyone in America was setting them off for my sake. They popped and exploded into flames like my wrist. They shot up into the sky like me.

The next day, at Urgent Care, they’d send me straight to the hospital. What we thought was a sprain was in fact a break, nice and clean. My mom was stunned. She didn’t think I’d cried enough for a break. She told the doctors as much, that I’d barely sniffled. The only tears that came leaked out of the corners of my eyes, like it was my body crying and not me. I’d even gotten out of bed to go over to my neighbor’s, she said. But there it was on the X-ray, both bones in my wrist split into pieces. I needed a cast, not a brace, and mine was a bright, clear blue, the color of the sky. India signed my cast before my family did. I went to her house as soon as I got back from the hospital, ready to show my cast off. Cheray came out from the kitchen while India signed her name. Her eyes bugged out of her head when she saw the cast.

“It wasn’t a sprain,” I explained. “I broke it.”

“I’m surprised,” she said. “Breaking a bone is painful, even as a grown-up. You didn’t cry very much.”

I nodded. “I know. I tried not to. It really hurt, but I didn’t want to cry in front of everyone.” Cheray frowned. “You’re allowed to cry, you know, especially if you’re in pain. That way people know you’re hurt, and they can help you. You should have gone to the hospital to get that cast last night.”

I was quiet when Cheray signed her name. Cheray and her daughters moved away

when I was twelve, but I think about them every Fourth of July. I like to think that they think about me, that they watch fireworks paint the sky every year and remember me laughing in the moments before impact. I hope they remember taking care of me the entire night. I hope India remembers fixing me with her dark eyes, watching me instead of the biggest fireworks we’d ever seen. I’d spent so long being drawn in by her eyes, and finally, they were drawn to me. I wanted her to look at me forever.

My left wrist isn’t what it used to be. It doesn’t turn all the way, and I can’t bend it for too long before it starts to burn. It’ll pop in and out of place and aches when it rains.

Summer isn’t what it used to be either. The Grahams moved away in June before eighth grade, Mackenzie’s dad forced to leave behind a life of sanitation work for the oil fields of North Dakota. The Cooks moved away even earlier, February of seventh grade when Bubba and Cheray broke up. My family stayed until my freshman year of high school before my parents decided a trailer house wasn’t the house of their dreams and took a risk on a property in the middle of nowhere. It didn’t pay off. Summers became my time to toil away washing dishes to save up for college and feed my car increasingly expensive gas. I worked every Fourth of July throughout high school.

The last good Fourth of July, I spent the day not working, but with a coworker from my summer job and his friends, setting off fireworks in an abandoned K-Mart parking lot. I felt him staring at me the whole night, his gaze a weight on the back of my head. When a sparkler burnt my fingertips, I didn’t try to keep quiet. I vocalized all the pain I felt, and he laid his cool hand on my red, bubbling skin. It felt nice, both the pressure of his hand on mine and the attention I asked for, but I found myself wishing his blue eyes were dark brown, almost black, enough to draw me into their darkness. I wished my burnt fingertips were a broken wrist.

I want a do-over. I want to be back on my

neighbor’s lawn. I want to have fallen harder, my arm bent backward and mangled, hard enough to make the bone stick out. I want to cry harder. I will be impossible to ignore, wailing in such a way that everyone will feel the depth of my pain. I want to be impossible to forget, impossible to leave behind watching passing cars in the corner of the playground. I want a girl to think of me every Fourth of July, to look up at the fireworks as they sail upwards, and when they burst, she’ll tell her friends a crazy story about a Fourth when she was a kid, a neighbor girl she’ll never forget. I want to leave her with something that’ll pop out of place and ache when it rains.

by John Scott

by John Scott

So one day we’re driving while the sun sets in front of us. We’re passing an apple back and forth, dipping it in honey between bites, and It feels like sex. I feel the grooves of your teeth in its flesh with the flat of my tongue, Memorizing the parts of you that leave a mark.

The first time you came over, you wore a lacy white bra, just in case. When I kissed you, our bodies became these things with wings. Our clothes, your white lace, became a pile near my bed, a quiet condition of intimacy. Your voice became a sea of gentleness, a mouthful of permission.

The first time you told me you loved me, at our favorite coffee shop, I almost puked Four shots of espresso with lavender syrup and oat milk all over you. My hands were trembling like freezing bodies. All I can do now is wonder how you did it

How you have contained me, How I can feel the grooves of your teeth in my flesh.

I exist inside the soft of the marrowbone with you, kneeling down beside the riverbed, hands held out stretched reaching for a reminder of the narrow moments left between us—

Summer is almost over. You have packed your bags in the back of your grandfather’s truck I’ll miss you and you’re getting ready to leave. You’ll be back next summer but it won’t be the same and we can play down by the river again —but we settle for one of those river rocks instead. We crack it open and it breaks into three: one for you the river and me

by Andrew Sowers

by Andrew Sowers

by Bailey Rigby

by Bailey Rigby

Grace must be a grandmother: her tender black knuckles to my boiling forehead, her Tootsie Roll voice bouncing over midnight stories as she ignores my weight on her aching knee. When she floats away, does Grace leave too?

Can I find it in this desk lamp: lying on my midnight poems, cupping grey words, in bright hands? Can we lose Grace when honesty is a burden, when lineage can’t be erased. Is there Grace without God, without a grandmother?

Maybe Grace is folding poem pages into paper boats to float after her. My ransom notes inked onto manilla hulls, soaking up sea salt, sinking into murky water.

I pay Him to see her; I have to learn to love them both.

My wrist blossoms with fulgid pixels. There is a space station 2 miles from here, Past the red-eyed riverbend and two moons.

Orange skies that taste like dandelions Drip deeply into purpled-leafed fig trees, Melting into iridescent mists of evergreen.

I had forgotten how beautiful it all was. In all the commotion of human expansion, We stumbled upon this lost exoplanet, and preyed like parasites upon its essence.

Tulip-colored cottage cheese plants Sat curiously in vacuous windowsills while Seven-eyed sow, as large as leviathan realms, Grazed lazily in copper carpet-grass fields.

Eventually, this land will render an artist’s masterpiece, Only to freeze or burn like gas station receipts When we pump the plump planet for oil and crystals And fill the air full of rose-rotted rabies.

When this dirt dies down to the last sediment, Newly fueled, we’ll fly back into the cosmos To create everlasting chaos and art. Stardust destinies be damned.

Tess Cahill is an undergraduate student studying art at Eastern Oregon University. She loves painting, drawing, and printmaking, and she likes to explore illustration and animation in her free time.

Jadyn Genest is an undergraduate student at University of Central Florida studying English literature and political science. She enjoys being snobby about tea, watching bad horror movies, and admiring her cat, Spot.

Erica Ivy Gilley is an undergraduate student at Radford University in Radford, VA earning a Bachelor of Science in English (Professional/Technical Writing) and Bachelor of Arts in Dance. She was born March 23, 2000, in Patrick County, VA and was raised in Bassett, VA. After graduating in December 2022, she plans to pursue a career in professional/technical writing while earning a certificate in pilates, writing poetry, and spoiling her rambunctious cats, Montoya and Grace.

Edmund Grey is a fourth-year undergraduate student at the University of Maine Orono with a major in English and a double minor in Folklore and Anthropology. As a transmasculine person, gender and sexuality play a big part in his work.

Stephanie Howard is an undergraduate student at Rocky Mountain College in Billings, Montana. She spends her free time crocheting, watching horror movies, and avoiding her responsibilities.

Ali Keiser is a senior English and Creative Writing Major at Lewis and Clark College. Ali is a poet and author stimulated by natural beauty, memory, and interiority.

Kate Mason is an undergraduate student at Northeastern University. She has a love for creative writing, film production, and the natural world and enjoys finding ways to explore and combine these passions.

Martheaus Perkins is an undergraduate at Stephen F. Austin State University in Texas. He is an African American writer, and his heroes include Maya Angelou, Billy Collins, and Langston Hughes. He has two long-term dreams: seeing a panda in the wild and publishing a poetry collection.

Bailey Rigby is a senior BFA photography student at Utah State University. Bailey has worked with digital photography since high school and has perfected the craft of shooting as if she were in a horror film. Her work largely focuses on autobiographical experiences and questions.

Andrew Sowers is a senior at The University of New Mexico, double majoring in English and philosophy. He is an easily distracted aspiring writer whose disposition somehow contains most qualities of both a four-year-old boy and an eighty-year-old man. In both his writing and in his photography, Andrew is interested in considering connections between the profound and the ordinary and arguing that they are the same thing. His work has been published in Conceptions Southwest and From the Brush.

John Scott is an undergraduate student at the University of New Mexico studying English and philosophy. He'll be quick to tell you why your favorite film sucks and likes to say that he'll trade his smartphone in for a flip phone, but he never will.

Ethan Ward is an undergraduate at the University of New Mexico. He's the kind of person to say he likes to hike, but almost never does it. Some of his favorite things to do are going to the climbing gym, drinking tasty coffee, and hiking. His poetry has appeared in Conceptions Southwest and From the Brush.

Alyson Yates is an undergraduate student at Eastern Oregon University. When she is not studying agriculture and art, she enjoys traveling, exploring the outdoors, and attending concerts with her camera in hand.

by John Scott

Editor in Chief

Hannah Lee

Managing Editor Jay Paine

Design Managing Editor

Mya Bethers

Poetry Co-Editors

Preston Waddoups Jake Perry

Poetry Staff

Isabelle Scott Hannah Lee Andrea Giles Paige Winegar McKinlee Armstrong Jay Paine

Nonfiction Editor Kyler Tolman

Nonfiction Staff

Mya Bethers

Danielle Bucio Adelaide Wilkinson Kayleigh Kearsley

Fiction Co-Editors

Deren Bott Paul Burdiss

Fiction Staff

Karissa Benson Will Clark

Melissa Cook Brian Cole Katie Thomas

Fiction

Charles Waugh Nonfiction

Russ Beck Poetry Millie Tullis

Art and Design Robb Kunz