The heavens proclaim your glory, O God, and the firmament shows forth the work of your hands.

The heavens proclaim your glory, O God, and the firmament shows forth the work of your hands.

Abbey Banner

Magazine of Saint John’s Abbey Winter 2024–25 Volume 24, Number 3

Published three times annually (spring, fall, winter) by the monks of Saint John’s Abbey.

Editor: Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

Desktop publisher: Jason Ziegler

Editorial assistants: Gloria Hardy; Patsy Jones, Obl.S.B.; Aaron Raverty, O.S.B. Abbey archivist: David Klingeman, O.S.B.

University archivists: Peggy L. Roske, Elizabeth Knuth

Circulation: Ruth Athmann, Tanya Boettcher, Debra Bohlman, Chantel Braegelmann

Printed by Palmer Printing

Copyright © 2024 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota.

ISSN: 2330-6181 (print) ISSN: 2332-2489 (online)

Saint John’s Abbey 2900 Abbey Plaza Box 2015 Collegeville, Minnesota 56321–2015 saintjohnsabbey.org/abbey-banner

Change of address: Ruth Athmann

P. O. Box 7222 Collegeville, Minnesota 56321–7222 rathmann@csbsju.edu

Phone: 800.635.7303

Subscription requests or questions: abbeybanner@csbsju.edu

Cover: Nicholas Black Elk. Portrait by Philip Bannister.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Illustration (USA) Inc.

Used with permission.

Medal of Saint Benedict: Nheyob

Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances, for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you.

1 Thessalonians 5:16–18

This issue explores how humans encounter the divine, how we pursue a holy life. For Christians, prayer is the most common avenue to communion with God. Saint Benedict, in harmony with Saint Paul’s exhortation “to pray without ceasing,” insists that his monks devote themselves “frequently to prayer” (Rule 4.56) and that “nothing be put before the Work of God (Rule 43.3). The liturgical schedule that Benedict envisions confirms that prayer punctuates each day (and even the middle of the night!). He also assumes that monks will engage in private prayer with “tears and fervor of heart” (52.4). Are there other forms of prayer, other ways to encounter God? Father John Meoska introduces us to iconography—that he calls “a form of prayer”—and explores the prayerful encounter of the iconographer and the person or reality being depicted.

Prayer is not the only expression of our faith and seeking to live in accord with the Gospel. Our relationships with others also demonstrate our understanding and commitment to the Word of God. “Mercy is what is most characteristic of the ministry of Jesus,” asserts Father William Skudlarek, who outlines the centrality of mercy in the life and ministry of Pope Francis.

“Epiphany,” said author James Joyce, is that “visionary moment when characters have a sudden insight or realization that changes their understanding of themselves or their comprehension of the world.” Father Michael Patella addresses the feast of the Epiphany, the moment that Jesus showed himself as the Messiah. Brother Aaron Raverty introduces us to Nicholas Black Elk, candidate for canonization, whose encounters with his fellow Oglala Lakota holy ones and with Jesuit missionaries convinced him that at the center of the universe dwells the Great Spirit, which in turn helped him to harmonize the cultural features of being a Native American and a Christian.

Throughout their existence, Benedictine monasteries have treasured their independence, shying away from hierarchical structures, only reluctantly forming congregations of abbeys. Prior Eric Hollas identifies the organizational reforms (impositions?) of Pope Leo XIII on Benedictines—that he famously called “not an Order” but “a disorder”! In this issue we also learn about the Congress of Abbots, the concerns and recommendations of the Synod on Synodality, the value of fire in stewardship of the land, the latest titles from Liturgical Press, and more.

Along with Abbot Douglas and the monastic community, the staff of Abbey Banner extends prayerful best wishes to all our readers for a joyous Christmas and Epiphany and a new year filled with God’s blessings and grace. Peace!

Brother Robin Pierzina, O.S.B.

The Lord lifts up spirits, brings a sparkle to the eyes, gives health and life and blessing.

Sirach 34:20

Abbot Douglas Mullin, O.S.B.

Walking into the Congress of Abbots at Sant’Anselmo in September felt like I was entering a living tapestry of Benedictine life, woven from the threads of global challenges and enduring hope. Nestled on the Aventine Hill in Rome, Sant’Anselmo is both the spiritual and academic heart of the Benedictine Confederation. This gathering offered a profound glimpse into the worldwide scope of our monastic vocation—a vibrant encounter with Benedictines from every corner of the globe.

The atmosphere was solemn yet alive with the energy of monastic fraternity. Nearly 220 abbots and priors came together to pray, reflect, and discuss the pressing issues facing our communities. We also had the sacred responsibility of electing a new abbot primate. The presence of two dozen Benedictine sisters enriched the Congress further, as they brought unique perspectives and experiences to our discussions.

The Congress was impeccably organized and technologically sophisticated. Simultaneous translations in multiple languages were streamed directly to our headphones, allowing full and meaningful participation by everyone, regardless of language. In true Roman fashion, the meals were exceptional! (While the food at Sant’Anselmo was outstanding, many of us took the opportunity to explore other culinary delights on outings with fellow abbots, strengthening our bonds over shared meals.)

Seek after peace, and pursue it.

Rule of Saint Benedict Prol.17

Psalm 34:15

Peace, that is your thing as Benedictines.

Pope Francis

Two keynote addresses left a deep impression on me. The first, delivered by outgoing Abbot Primate Gregory Polan, drew on the wisdom of our desert ancestors to offer guidance for the challenges we face today.

The second, by Dominican Father (now Cardinal) Timothy Radcliffe, titled “Pruned that you may bear much fruit,” spoke powerfully about the resilience and renewal that can come from being pruned—a metaphor that resonates with our monastic experience. Abbot Nikodemus Schnabel’s response to Father Timothy’s talk was equally inspiring, especially given the struggles his community faces at Dormition Abbey and Tabgha in Israel.

The Congress nurtured both new and renewed bonds among us as we attended to various internal matters, elected Abbot Jeremias Schröder as the new abbot primate, and designated 2028–2029 as a Benedictine Jubilee Year, marking 1,500 years since the founding of Montecassino.

A particularly moving moment was our general audience with Pope Francis. His exhortation to work tirelessly for peace—starting within our own hearts—struck a deep chord. He reminded us: “Peace, that is your thing as Benedictines. But start from the inside!” His challenge continues to echo within me, as we strive to navigate the delicate balance of monastic life in an ever-changing, often turbulent world.

Michael Patella, O.S.B.

James Joyce (1882–1941), the great Irish author, reacting to a stultifyingly bourgeois Catholic upbringing in Dublin, saw the Church as an obstacle to his desire and ability to become a good writer. He famously renounced his faith to further his growth as an artist. From that moment, and despite himself, he went on to become one of the greatest Catholic authors. Once, in speaking about modern literature, he defined “epiphany” as “a visionary moment when characters have a sudden insight or realization that changes their understanding of themselves or their comprehension of the world.”

Christians use the word, “epiphany,” too, but for them, it commemorates the moment that Jesus showed himself to the world as the Messiah. It is a manifestation that touches us personally. The Book of Isaiah describes a glorious vision of the end times, “Arise! Shine, for your light has come, the glory of the LORD has dawned upon you” (60:1). While the context suggests Isaiah is addressing Jerusalem, he does so in the second person singular, a detail that simultaneously recognizes the community at large as well as the personhood of each community member. Each of us gets drawn into this vision.

The most recognizable icons for the feast of Epiphany are the

Magi. These three, most likely Zoroastrian astrologers, do not know what to expect as they follow the star. Such portents in the heavens, they assumed, could only point to something or someone of great magnitude. Their conclusion that the star pointed to the birth of the king of the Jews was an educated guess.

Historically, Isaiah describes the restoration of the Jewish kingdom under Cyrus the Great after the disaster of the Babylonian exile. All the prophets, including Isaiah, had told the people that they would pay the price for rejecting the covenant. The people recognize this, reform

their lives, and now must make the Lord present in their lives by holding to that covenant. Divine love, however, cannot be hidden. If the people are going to live a covenantal life with God, others are going to notice it, and they will want to be in God’s presence as well. This moment of awareness on behalf of the non-Jewish world is the scene Isaiah is describing.

The intriguing part of Isaiah’s vision is that the prophet gives no material reason for the nations to come to Jerusalem. The caravans of camels, the dromedaries of Midian and Ephah, and all from Sheba come

bearing gold and frankincense— streaming toward Jerusalem because of the city’s shining radiance (Isaiah 60:1–6). It is like a lighthouse guiding sailors in a storm. Only when they arrive do they discover that the bright shining radiance is actually God’s presence within the city. What they see is the glow of divine love.

The evangelist Matthew understands this. Isaiah mentions the “dromedaries of Midian and Ephah” coming to Jerusalem. Matthew uses that reference to elaborate and connect the gospel Magi to Isaiah’s account (Matthew 2:1–12). Matthew wants the readers of his Gospel to think of the Magi as part of this stream drawn to divine love. We must remember that the Gospel is also written for us in the twenty-first century, so we have every right to think of ourselves as Magi and thus players in this story as well. We must, then, have the faith of the Magi. Unfortunately, outside of these two references, we have precious little information about them. We are left with our imaginations and the tradition to fill in the blanks.

At Saint John’s, the church environment crew is responsible for decorating the church for all major celebrations, and for years, they have placed the Christmas manger in the north end of the church. If we line up the three Magi of our crèche, one after the other, with their

feet all pointing the same way, each is gazing in a different direction! This curious detail suggests that the Magi, coming all the way from Persia, were so lost and confused that they could not even play follow the leader! Moreover, though they have come close to identifying it, modern-day astronomers and scientists still cannot figure out conclusively what combination of planets and constellations formed the star of Bethlehem.

Whatever that bright star was in the heavens, it was enhanced by God’s warm, burning, incarnate love emanating from the manger, just as Isaiah foretold. It was this combined brilliance of the heavens and incarnate love that led the Magi to Bethlehem.

Many of us can identify with the Magi. They had their wandering ways, and we have ours. They were second-guessing, and so do we. We seek Christ and want to find him, but at times we get lost. We go through life with our sureties about our faith, but the doubts keep whispering in our other ear. And then something happens! A chance encounter with someone special. Some bits of information that provide deep insight. Some experience ignites a heart. In those moments, we, too, can hear the prophet say, “Arise! Shine, for your light has come, the glory of the LORD has dawned upon you.”

When we find that love, it does exactly what James Joyce said it

would do: it changes our understanding of ourselves and our comprehension of the world. We, too, become absorbed in that love, despite our struggles, doubts, and even perhaps, antipathy toward faith.

Father Michael Patella, Professor Emeritus of New Testament and recent rector of Saint John’s Seminary, was the chair of the Committee on Illumination and Texts for The Saint John’s Bible.

O Star of Wonder, Star of Night, Star with Royal Beauty bright, Westward leading, Still proceeding, Guide us to Thy perfect Light.

Logan Lintvedt

This past summer, I spent a month in Israel, assisting at Beit Noah, an interfaith, volunteer-run retreat center near Tiberias on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. Beit Noah serves Israeli and Palestinian children and youth with disabilities. Due to the escalating conflict in the region, the center has been losing its steady stream of volunteers, leaving it understaffed and vulnerable. I felt compelled to assist. I journeyed to the Holy Land, anticipating that the experience would change me, and indeed, it did—though I’m still trying to understand what all happened.

Prior to my arrival, I felt an overwhelming sense of anger and helplessness when hearing of the violence in Gaza, Rafah, and the West Bank; when seeing

Come with me by yourselves to a quiet place and get some rest.

Mark 6:31

the haunting images of people— young and old, Palestinian and Israeli—trapped in a seemingly endless cycle of conflict. Like many, I was dismayed by the horrors and heartache of it all.

Traveling to Israel, I hoped to find something good amidst the chaos, something that might light a candle of hope in a land so often shrouded in darkness.

Most of my time was spent at the Benedictine monastery in Tabgha, the home to the Church of the Multiplication of the Loaves and Fish that commemorates Jesus’ miracle of feeding the five thousand (Matthew 14:13–21). It wasn’t just the ancient and spiritual significance of this place that struck me,

however; it was the ongoing, everyday miracles happening in unexpected corners. At Beit Noah, the monks of Tabgha provide a place for Palestinians and Israelis to escape the violence that marks their homes so they can just be human together. Here, amidst laughter and shared stories, the participants engage in simple activities that allow them to connect as individuals, devoid of the political or cultural labels and tensions imposed on them by the outside world.

Witnessing this gave me hope! Hope that despite the violence, the seeds of peace might be taking root somewhere in this troubled land. As one of the monks observed: “Peace isn’t just the absence of war—it’s about dignity, respect, and goodwill between people.” It’s about seeing one another not as enemies, but as fellow human beings, with all the complexities and dreams that make us who we are. It’s expressed through openness to others, seeking to understand others, and a willingness to see every human being as deserving of dignity and respect.

Upon further reflection, I recognize that my experience in Tabgha mirrored the philosophy of the Benedictine Volunteer Corps (BVC). In the BVC, we strive to make a measurable impact simply by listening, by being present, by serving. Benedictine Volunteers don’t merely complete tasks. Rather, they become part of the fabric

of the communities they serve. Their work is grounded in listening to the needs of the people they support, being present in their daily lives, and creating connections based on trust and empathy.

At Beit Noah, I witnessed these principles at play—through shared meals, listening to stories, being fully present to others. This is why the BVC’s efforts in places as disparate as East Africa and Israel and Newark have been so impactful. Benedictine Volunteers immerse themselves not just to offer assistance but to

form genuine, lasting bonds. The work at Beit Noah isn’t about imposing solutions or achieving grand goals; it is about small acts of bringing people together, of recognizing the humanity in each other despite the labels and conflict that surrounds them.

The children and adults I met at Beit Noah weren’t defined by violence—they were individuals with dreams, talents, and stories worth hearing.

I’m still processing everything I experienced this past summer. The good people I met, the mix of horror and hope in their

stories, will stay with me for the rest of my life. Tabgha was the best of times and the worst of times. There were moments of deep sadness, seeing the pain in children’s eyes. There were also moments of profound joy, sharing in the laughter of people who had every reason to despair but chose instead to hope. My time in Israel showed me that even in the midst of conflict, it is possible to create a microcosm of peace.

Beit Noah is a beacon of hope during challenging times. Beit Noah offers a glimpse of what could be—a world where people honor one another with dignity and respect. That’s a vision celebrated in Scripture and in the Rule of Benedict—and shared by the Benedictine Volunteer Corps.

Mr. Logan Lintvedt, who served with the BVC in Uganda and Kenya in 2021–2022, is the assistant director of the Benedictine Volunteer Corps.

They should anticipate one another in honor; most patiently endure one another’s infirmities, whether of body or of character; vie in paying obedience one to another—no one following what one considers useful for oneself, but rather what benefits another.

Rule of Benedict 72.4–7

Romans 12:10

Saint John’s Abbot Douglas Mullin, O.S.B., joined more than 200 other Benedictine superiors from around the world during the quadrennial Congress of Abbots at Sant’Anselmo, Rome, September 4–20. The superiors discussed what is happening in their monasteries and the viability of Benedictine monastic life itself, how they can work together, and how they can reach out to the rest of the world. The workshops for the assembly addressed a variety of topics, including “Overworked and underpaid: Communities under stress,” “Ongoing formation for abbots and conventual priors,” “Being a pastor for broken monks,” “How to create a sense of community in an individualistic world,” “Fostering solid Benedictine vocations,” “Brothers as superiors,” and “Perspectives of cooperation between men and women in monastic life.” Abbot Douglas also participated in a workshop for new abbots.

On September 14, the Congress elected German Abbot Jeremias Schröder, O.S.B., as the new Abbot Primate of the Benedictine Confederation. He succeeds the retiring American Abbot Gregory Polan, O.S.B., a graduate of Saint John’s School of Theology and Seminary, who has served as abbot primate since 2016. Abbot Primate Jeremias, a Benedictine monk for forty years, was serving as the Abbot President of the Congregation of St. Ottilien Archabbey (Eresing,

Germany), motherhouse of the St. Ottilien Congregation that aims to combine the Benedictine way of life with activity in the mission field.

At the time of his election, Abbot Primate Jeremias commented, “The world is on fire right now. We have here the witness of abbots who come from countries at war in Ukraine and the Holy Land. Next week, during this Congress we abbots will try to reflect together on how we can respond to the motto of our order, which is Pax, peace. We will reflect on how we can truly contribute to peace through the work of our communities, through witness, through building bridges between cultures. East and West are separating. The Benedictines have the ancient mission to be in relationship with the Eastern Churches. There is something where we can really make a contribution, and we will work on this.”

The first abbot primate was named by Pope Leo XIII in 1893 to serve as the Benedictine liaison to the Vatican, to promote unity among the autonomous Benedictine monasteries and congregations around the world, and to represent the order at international religious gatherings. Abbot Jeremias is the eleventh abbot primate to hold the position. Saint John’s Abbot Jerome Theisen, O.S.B., served as primate from 1992 until his untimely death in 1995.

During the Congress, Saint John’s Father William Skudlarek, O.S.B., Secretary General of Dialogue Interreligieux Monastique/Monastic Interreligious Dialogue (DIM•MID) since 2007, introduced his successor, Father Cyprian Consiglio, O.S.B.Cam An international monastic organization, DIM•MID promotes and supports interfaith dialogue, especially between Christian monastic men and women and followers of other religions. Its members also engage in spiritual dialogue with adherents of religions that do not have an institutionalized form of monasticism, for example—and in particular—with Muslims. A “spiritual exchange” program between Japanese Zen Buddhist monks and nuns and Christian monastic communities has been ongoing since 1979.

The (dis)Order of Saint Benedict

Eric Hollas, O.S.B.

In September 2024 the worldwide Congress of Abbots elected Jeremias Schröder as abbot primate of the Benedictine Confederation. He had served as archabbot of Sankt Ottilien in Germany and also as abbot president of the Congregation of Sankt Ottilien. He succeeded Abbot Primate Gregory Polan, the former abbot of Conception Abbey, in Missouri.

As dry and succinct as the paragraph above may sound, there is nothing in it that Saint Benedict would recognize. He can be forgiven his ignorance of the abbeys of Sankt Ottilien and Conception, since they were founded centuries after his death. As for an “abbot primate,” “abbot president,” and “congregation,” however, there is not a word in his Rule about any of these.

Benedict presumed that each monastery would be independent. Each would select its own superior, and each was answerable to God and occasionally to the monks of the community. (That changed over the centuries, however.) Benedict understood that monasteries might encounter difficulties, but he was hazy on how best to deal with them. The local bishop might intervene, but most bishops were hesitant to do so. Nor was there a provision for another monastery to come to the rescue of a failing neighbor. For centuries, then, monasteries were left to sink or swim on their own.

By the end of the eighth century, hundreds of monasteries in Western Europe were in financial or disciplinary trouble, and that led to centuries of experimentation. Some abbeys began to form congregations in which one community could come to the aid of another. In the tenth century, some 350 abbeys submitted to the abbot of Cluny and formed an impressive but sometimes unwieldy order. Still later the Cistercians introduced regular visitations, helping to achieve a uniformity of observance among the monasteries.

The French Revolution put an end to monastic life in Western Europe, but only for a while. Revival came in the nineteenth century, but the revival needed organization if it were to avoid the mistakes of the past. It was Pope Leo XIII who took on this task. Leo oversaw the formation of congregations of abbeys, imposed canonical visitations, and established an abbot primate with power similar to the Jesuit superior general. But on the latter detail, the Benedictines drew the line! Abbeys would not surrender their canonical independence, and the primate remained essentially a figurehead. Though he achieved most of what he wanted, Pope Leo XIII acknowledged defeat on this point, declaring: “The Benedictines are not an Order. They are a disorder.” And that’s the way it is, still.

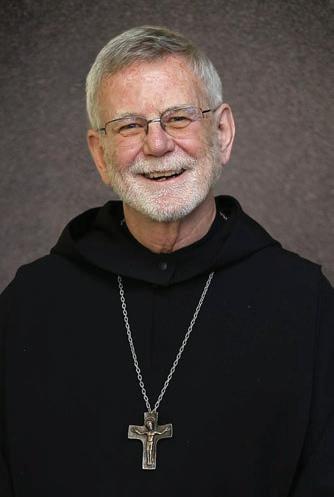

Father Eric Hollas, O.S.B., is the prior of Saint John’s Abbey.

On October 26 the 355 delegates at the Second Session of the XVI Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops (2–27 October 2024) approved the 52-page final document, “For a Synodal Church: Communion, Participation, Mission.” Pope Francis expressed his gratitude to the assembly: “With this final document, we have gathered the fruits of at least three years in which we have been listening to the People of God in order better to understand how to be a ‘synodal Church’—it is by listening to the Holy Spirit.” He went on to say, “I do not intend to publish an apostolic exhortation; what we have approved is sufficient.” Rather, “I am making it immediately available to everyone.” The pope pledged to continue listening “to the bishops and the Churches entrusted to them”—which corresponds to the synodal style of “listening, convening, discerning, deciding, and evaluating.” Excerpts from the final document follow.

Healing, reconciliation, rebuilding. The participants of the synod acknowledged the need within “the Church for healing, reconciliation, and the rebuilding of trust”—particularly “in light of so many scandals related to different types of abuse” (§46). “We cannot deny that we have faced fatigue, resistance to change, and the temptation to let our own ideas prevail over listening to the Gospel and the practice of discernment. We

Listening is a fundamental aspect of the journey toward healing, repentance, justice, and reconciliation.

identified our sins: against peace; against Creation; against Indigenous Peoples, migrants, children, women, and those who are poor; against failures in listening and in building communion” (§6). “Even our relationship with our mother and sister Earth bears the mark of a fracture that endangers the lives of countless communities, particularly among those most poor, if not entire peoples” (§54).

“Many of the evils that afflict our world are also visible in the Church. The abuse crisis, in its various and tragic manifestations, has brought untold and often ongoing suffering to victims and survivors, and to their communities. The Church must listen with particular attention and sensitivity to the voice of victims and survivors of abuse. This includes sexual, spiritual, economic and institutional abuse, as well as the abuse of power and conscience by members of the clergy or those holding ecclesial roles. Listening is a fundamental aspect of the journey toward healing, repentance, justice, and reconciliation. The Church must acknowledge its own shortcomings. It must humbly ask for forgiveness, must care for victims, provide for preventative measures, and strive in

the Lord to rebuild mutual trust” (§55).

Equal dignity of the People of God. “By virtue of baptism, women and men have equal dignity as members of the People of God. However, women continue to encounter obstacles in obtaining a fuller recognition of their charisms, vocation, and roles in all the various areas of the Church’s life. There is no reason or impediment that should prevent women from carrying out leadership roles in the Church: what comes from the Holy Spirit cannot be stopped. Additionally, the question of women’s access to diaconal ministry remains open. This discernment needs to continue. The assembly also asks that more attention be given to the language and images used in preaching, teaching, catechesis, and the drafting of official Church documents, giving more space to the contributions of female saints, theologians, and mystics” (§60).

Network of relationships. The Church “aspires to be a network of relationships which prophetically propagates and promotes a culture of encounter, social justice, inclusion of the marginalized, communion among peoples, and care for the earth, our common home” (§121).

Petrine ministry. “A synodal reflection on the exercise of the Petrine ministry must be undertaken from the perspective of the ‘sound decentralization’ wanted

by Pope Francis and many episcopal conferences.” According to Praedicate Evangelium [On the Roman Curia and Its Service], this decentralization means “to leave to the competence of bishops the authority to resolve, in the exercise of ‘their proper task as teachers’ and pastors, those issues with which they are familiar and that do not affect the Church’s unity of doctrine, discipline, and communion” (§134).

Ecumenism. “One of the most significant fruits of the Synod 2021–2024 has been the intensity of ecumenical zeal.” [The assembly calls for] “a rereading or an official commentary on the dogmatic definitions of the First Vatican Council on primacy, a clearer distinction between the different responsibilities of the pope, the promotion of synodality within the Church and in its relationship with the world, and the search for a model of unity based on an ecclesiology of communion” (§137).

Formation. “Discernment and formation of candidates for ordained ministry [should] be undertaken in a synodal way. There should be a significant presence of women, an immersion in the daily life of communities, and formation to enable collaboration with everyone in the Church and in how to practice ecclesial discernment. The assembly calls for a revision of the Ratio Fundamentalis Institutionis Sacerdotalis [Priestly Formation] in order to

incorporate the requests made by the Synod. They should be translated in precise guidelines for a formation to synodality” (§148).

“Another area of great importance is the promotion in all ecclesial contexts of a culture of safeguarding, making communities ever safer places for minors and vulnerable persons . . . offering specific and adequate formation to those who work in contact with minors and vulnerable adults so that they can act competently and recognize the signals, often silent, of those experiencing difficulties and needing help. It is essential that victims are welcomed and supported” (§150).

A synodal Church. “The local churches are asked to continue their daily journey with a synodal methodology of consultation and discernment, identifying concrete ways and formation

pathways to bring about a tangible synodal conversion in the various ecclesial contexts (parishes, institutes of consecrated life and societies of apostolic life, movements of the faithful, dioceses, episcopal conferences, groupings of Churches, etc.)” (§9). [In the synodal Church] “the whole community, in the free and rich diversity of its members, is called together to pray, listen, analyze, dialogue, discern, and offer advice on taking pastoral decisions for mission. The way to promote a synodal Church is to foster greater participation of all the People of God in decision-making processes” (§87).

The way to promote a synodal Church is to foster greater participation of all the People of God in decision-making processes.

Aaron Raverty, O.S.B.

Nicholas Black Elk (c. 1863–1950), a Native American descendant of Oglala Lakota healers and holy men, grew up in South Dakota during the so-called Sioux Wars. As a youth, he experienced personal revelations accompanied by other-than-human voices. He had his first vision at age six followed by a “solemn” vision when he was nine years old. This prolonged, twelveday childhood vision from the ancestors left a powerful and traumatic impact on Black Elk, who kept it all to himself. Black Elk records that in his vision he saw the unity of all creation in a holy flowering tree within the sacred hoop. The effects of this vision came back to haunt him during his younger life, and, as he matured into manhood, he felt disturbed about disregarding this call of the holy ones.

Human beings often view reality through “kin-tinted” lenses. In the twenty-first century, we have dulled this tendency through sophisticated technological distancing. But Nicholas Black Elk expressed his kinship to all beings in the form of prayer: “Hear me, four quarters of the world—a relative I am! Give me the strength to walk the soft earth, a relative to all that is!” (Black Elk Speaks, 6). This worldview informs the primordial practice of ancestor veneration (the Lakota “Grandfathers”) and in the Christian tradition,

the communion of saints.

Black Elk participated in many communal Lakota rites, including sweat lodge ceremonies, the horse dance, the Heyoka ceremony (featuring fools and clowns), and the summer Sun Dance. As a young man, he accompanied other Lakota in buffalo hunts. He was a cousin to the great warrior Crazy Horse and fought in skirmishes surrounding the Battle of Little Big Horn (1876). He encountered his first healing session when he was eighteen years of age and continued his healing practice thereafter.

His autobiography, Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux, was first published in 1932. Dictated to amateur historian and ethnographer John G. Neihardt, Black Elk’s home at that time was near Manderson, South Dakota. Besides narrating the details of his own life, “Nick Black Elk and his friends reminisced about the attitude of their people toward ‘the whites’ and about events in their boyhood” (Alice Beck Kehoe, The Ghost Dance, 55).

This is the world Black Elk encountered and that formed him as a youth and an adult. Even as he continued his healing practice, Black Elk got caught up with other Lakota holy men in the revitalization movement accompanying the Ghost Dance (1889–1890, a spiritual movement that was founded on the hope that whites would leave their land, the bison herds would return, and the old way of life would return) and subsequently fought with other Lakota at the infamous battle of Wounded

Knee Creek. It was at Wounded Knee that Black Elk claimed his own personal vision merged with that of the Ghost Dance, and he was invoked to reveal his vision.

Following this battle, the Lakota people were devastated and disillusioned. Some wanted to understand the ways of the white man as they searched for consolation and a better way of life. Seeking a wider world and any remnant of hope to be discovered in white ways, Black Elk and some of his people performed in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. He spent about six months in New York and two

more years traveling overseas to England, Germany, Italy, and France. In New York, “I did not see anything to help my people. I could see that the Wasichus [white man] did not care for each other the way our people did. They would take everything from each other if they could, and so there were some who had more of everything than they could use, while crowds of people had nothing at all and maybe were starving. They had forgotten that the earth was their mother” (Black Elk Speaks, 217). In England, he and his group staged a private performance in 1887 for Queen Victoria

(“Grandmother England”), who lionized the troop and left a deeply positive impression with the Lakota performers. Upon his return to Pine Ridge in 1889, he found his own people confined on reservations.

In 1887 Red Cloud, a Lakota leader, invited Jesuit missionaries to the Pine Ridge Reservation because of his trust in the Jesuits, whom the Lakota called “black robes.” Unlike most white settlers, these were considered as holy men by many of the Lakota. Through a Jesuit priest, Black Elk took instruction in the Catholic faith at Holy

Black Elk Peak. At 7,242 feet, Black Elk Peak is the highest natural elevation in South Dakota. Formerly known as Harney Peak, it was renamed in 2016 by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names to honor the memory of this Lakota holy man who experienced his “solemn” vision here when he was nine years old and in recognition of the significance of the summit and Black Hills to Native Americans.

Rosary Mission. On 6 December 1904, he was baptized with the name of Nicholas, the date being Saint Nicholas Day. Thereafter, he would speak of December 6 as his birthday, declaring that he had been born again! He was probably about forty years old when he was baptized, thereafter enlisting as a catechist at the Catholic mission on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Catechists were more abundant among the Lakota than were priests and more directly involved than the fewer black robes in teaching and in officiating at many sacramental ministries. Black Elk’s home became a kind of “house church,” a place of counseling and worship. He preached the Gospel, taught the basics of the faith, and baptized the dying.

In 2017 the Vatican authorized Nicholas Black Elk’s cause for canonization, and he was named Servant of God. In an interview with Catholic News Agency (December 2023), Father Joseph Daoust, S.J., who serves at Pine Ridge, said Black Elk is recognized among the people of Pine Ridge as a holy man in both the Lakota and Catholic senses. “We didn’t run into any opposition to canonizing him, especially among his relatives,” he said.

The first stage in the movement toward sainthood is that the candidate demonstrate “heroic virtue” and may thus be considered “Venerable.” If a thorough examination of any writings of the candidate and of the candidate’s reputation for sanctity offer further evidence of the worthiness of a holy life, the person may achieve beatification and be called “Blessed.” Finally, after beatification, proof of two miracles (related to the Blessed One) is required for canonization. Then the Church solemnly declares the candidate to be united with God in heaven and worthy of veneration.

I send my people on the straight road that Christ’s Church has taught us about. While I live, I will never fall from faith in Christ.

Nicholas Black Elk

(Nicholas Black Elk: Medicine Man, Catechist, Saint by Jon M. Sweeney, 81)

Black Elk had a gift for harmonizing the different cultural features of being a Native American and being a Christian. He converted at least four hundred of his own people to Catholicism. But “accepting Christianity did not imply to Black Elk that he must abjure all Lakota beliefs. If there is one omnipotent God in Christian doctrine, and a

universal Power in Lakota cosmology, there seemed to the Lakota a fundamental agreement between the religions: a Lakota had only to add knowledge of Jesus Christ, whose historical existence the Lakota happened to have learned of earlier” (The Ghost Dance, 62).

According to anthropologist Father Michael F. Steltenkamp, S.J., who is championing Black Elk’s cause for canonization, the Jesuits developed a unique catechism for use among the illiterate on the American plains called

the “Two Roads Map”—a chart with colorful depictions of the Old Testament and the birth, ministry, death, and resurrection of Christ. A Black Road led to perdition, while a Red Road led through the Church to salvation. “Black Elk used the Two Roads Map for 30 years and taught many generations of kids and older people what Christians call salvation history. He said, ‘I saw my vocation as leading my people from the Black Road to the Red Road,’” according to Father Michael.

Nicholas Black Elk’s work as a Catholic catechist among the Lakota people combined with his healing ministry, his personal holiness and life of prayer, and his devotion to upholding Catholic teachings and sacramental life have convinced some ecclesiastics that he should be promoted for canonization. Black Elk was faithful to the end of his life as both a Lakota and a Christian.

Brother Aaron Raverty, O.S.B., a member of the Abbey Banner editorial staff, is the author of Refuge in Crestone: A Sanctuary for Interreligious Dialogue (Lexington Books, 2014).

John Meoska, O.S.B.

Ideveloped a love for writing icons. I do it without using words. Icon writing is the term used to describe the process. While icons are painted and have all the appearances of art, we call it icon writing because the iconographer is writing of his or her encounter with God, Mary or another saint, or other spiritual reality, such as Jesus’ nativity or his depiction as the Pantocrator (Almighty). Iconography visually parallels what the evangelists did by means of the printed word.

I was fortunate to receive training in both traditions of icon writing, Russian and Greek. This article will focus on some of the elements unique to the Russian tradition, as taught by my Russian teachers. However, most of what follows is common to both traditions.

Icon writing is considered a form of prayer. Indeed, iconography is—or at least can be—the very deeply personal prayer and prayerful encounter of the iconographer and the person or reality being depicted. For this reason, an iconographer will be reluctant to change an icon

written by another. I cannot presume to correct or add or subtract from another’s encounter with the holy!

The process of icon writing may begin with days or even weeks of fasting and prayer, of confession of sins and reconciliation, so that the Spirit may guide the mind, heart, and hands of the icon writer and his or her interpretation of the particular icon being re-presented. As a way of praying, icon writing can be deep, profound, sometimes satisfying, sometimes harrowing, sometimes humiliating or excruciating. Along with the joy and consolation it can bring, it is not uncommon for the iconographer, in the process of writing an icon, to become aware of some blockage, darkness, prejudice, anger, or other spiritual malady that is lingering in one’s soul and spirit.

As a way of prayer and as a spiritual discipline, one of the primary purposes of icon writing, especially in the Russian tradition, is annihilation of the inflated ego. This is made possible through a variety of means. First of all, the “canon” or list of true icons is set. Therefore, one does not make an icon of whatever person or religious event that suits one’s fancy. (Many have made modern depictions of Martin Luther King, Saint Teresa of Calcutta, the Calming of the Storm at Sea, etc., but these are considered religious art, not iconography, by some in the Russian tradition.)

Ego annihilation is also facilitated by the circumscribed process of icon writing. For any given icon in the Russian tradition, the pattern and colors are given, the sacred geometry and proportions are established, curves and lines and shading done in a certain way, and the sequence of writing an icon, from start to finish, is a very orderly one of approximately two dozen steps. Iconography is not a “do your own thing” type of process, and yet, the process does allow for and even demands a lot of intuition and prayer and openness. The process is, or at least can be, a way of purification, of contemplation and, perhaps, of contemplative prayer.

Like the icon, which is a window or portal or channel into the sacred, the contemplative becomes a place of peace, a channel of peace, in and for the

world. This is made possible if and when we have embraced the diminishment or annihilation of our inflated egos, and have named and sought to be healed of our latent violence, anger, prejudice, greed, sense of entitlement or privilege.

In the Russian tradition of icon writing, especially, but not exclusively, every element used—from the board and the shape of the board; to how the board is prepared; how and where it is coated with gesso, clay, or gold leaf; what colors are used; where and why they are used; how lines and curves are drawn—all of these elements have deep meaning as well as function or purpose. The board, for example, typically has a raised border and a recessed center. The border signifies the body; the recessed center, the soul; and the inscribed design to be written, the mind.

The point being: each of us is a sacred and complex unity of the three. Our very being is itself a trinity (small t).

The process of writing the icon using various pigments and colors is a process of moving through the dark layers (brown or olive), such as sankhir and roshkrish, or chaos layer (underlying all but the skin) through the various applications of color until one begins to concentrate the light colors, then the white colors, and the final application of white highlights called ozhivki or the uncreated light—a breath of the Holy Spirit. The

movement is from chaos and darkness to pure uncreated light, from the earthly and natural to the supernatural, from what is unredeemed to what is redeemed, from what is human to and into what is divine.

There is a unity and harmony that encompasses every aspect of our being in the world. There is no separateness between us as people, between the human community and the community of Mother Earth, between our earthly realms and the realms of heaven, between human and divine—unless we create or perpetuate a separation. The contemplative embrace or vision is to see all as holy, all as one, all as worthy of our love and respect—just as God sees, loves, and cherishes all that God has created. This contemplative, loving, prayerful embrace creates the bedrock foundation upon which to build a spirituality that resists all attempts—past, present, or future—to separate, marginalize, degrade, dehumanize, or diminish the other. The contemplative embrace of the world

is, for the very same reasons, a prophetic stance or embrace.

Consider the fifteenth-century icon Trinity written by the hand of Andrei Rublev in Russia. There are variations such as the Hospitality of Abraham and Sarah, sometimes called the Divine Guests. What we read in this version of the icon, based on Genesis 18:1–8, is hospitality. Abraham and Sarah see in the strangers the presence of the sacred. The three beings are received as divine guests, as God. In humility, Abraham and Sarah open their hearts and home to the others and serve them.

Other versions of the Trinity icon, including that of Rublev’s, do not feature Abraham and Sarah. Still, reading the Trinity icon reveals tremendous richness. Central to the icon is the presence of the three divine beings. Rublev understood them to be the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Save for the color of their robes, each looks identical to the other, signifying the unity in the Trinity—three distinct Persons, yet one divine nature.

This icon invites us to see and honor the divine presence in each other. Though separate individuals, we share a common humanity—each of us carries within

us a spark of the divine life; each of us is loved equally and fully by God. The Father’s hand is raised in blessing, “sending” the Son and Spirit into the world to share the divine life, inviting each of us, and all people, to share in the life and love of the Trinity—the history of salvation. What is especially notable about

this icon is

that, within the sacred geometry of the circle that moves between Father, Son, and Spirit, there seems to be an opening. That opening is an invitation to each of us to enter into the sacred banquet, the conversation, the dance, the life and love of the three Persons. Infinite hospitality. Utter enjoyment. You, I, and all creation are regarded with love, are invited in!

Finally, what we see in the background is a mountain, a tree, and a building. The mountain symbolizes the spirit and the spiritual journey of climbing the holy mountain. From a Christian perspective, the tree sym-

bolizes the tree of life and the tree of the Cross—the means of our salvation. Both of these, like the Persons of the Son and Spirit below, are inclined toward the Father (below) and the Father’s house (depicted above). Simply put, we go to God together.

We can see that the sacred circle below, embraced by the Trinity, and the stylized house above, are expansive enough to include every man, woman, and child, indeed all of creation. This inclusive love, this call to communion, is the source of our strength and resilience as peacemakers. And it is our clarion call to resist all forms of violence, hatred, prejudice, exclusion, and degradation that in any way excludes anyone, or anything, from this holy communion, “on earth as it is in heaven.”

Father John Meoska, O.S.B., an iconographer and woodworker, is liturgy director at Saint John’s Abbey.

The contemplative embrace or vision is to see all as holy, all as one, all as worthy of our love and respect—just as God sees, loves, and cherishes all that God has created.

Prescribed fires in the restored prairie and oak savanna at Saint John’s Abbey Arboretum are an important land management activity, a key element of our stewardship efforts. Prescribed burns help suppress the growth of trees and nonnative species, and they encourage the growth of native prairie plants, which in turn support birds, mammals, butterflies, and more. Prairie plants are pyrophytes—they have adaptations that allow them to thrive in the presence of fire. Deep root systems (up to 18 feet) and underground new growth points allow them to come back after drought, fire, and browsing characteristic of these habitats. Fires release nutrients in decaying plant material to the soil and open up the ground layer for new plants. Following a burn, it is amazing to watch how quickly prairie plants burst forth with new growth and flowers.

John Geissler

Emily Heidick

Liturgical Press is grateful for the many awards received this year for our new prayer, academic, and monastic publications. The honored titles range from devotional prayer books, to those challenging the Church to love justice and mercy, to engrossing historical narratives rooted in the Benedictine tradition. These books encourage the development of a theological imagination as our faith grows. May they help us enter into the expansive mystery of God through prayer and learning.

Living Prayer by Alison M. Benders, Lisa Fullam, and Gina Hens-Piazza centers on care for creation through the practice of Morning and Evening Prayer. This beautiful book walks through the salvation story from Genesis to the new creation when all will be reconciled to Christ. Focusing on ecology and social justice, the authors invite us to pray and then live out our prayer. Not only does the book have prayers for creation, but it also offers directions for centering oneself and further explains the patterns of the Divine Office. An excellent resource, Living Prayer invites us to the resurrection feast.

For Eucharistic prayer, Pope Francis on Eucharist is a beautiful collection of his reflections. As we continue on the Year of Mission of the National Eucharistic Revival,

these reflections are a prayerful resource to contemplate how the Eucharist transforms us. We encounter God in the sacrament and are challenged to go out and be as Christ for others in justice and service. This resource would be an excellent tool for adoration, group prayer, or personal prayer.

Another pocket-sized prayer book is Amy Ekeh’s Come to Me All of You. These meditations are paired with the linocut artwork of Gabrielle Rowell that truly make for an impactful prayer experience. The images are unique carved prints made specifically for this book. Reading Come to Me All of You during Lent last year made me see the Passion in a new light as I developed more empathy for the suffering and love of Christ—the scriptural passages were incredibly impactful. While this short text is written as a Stations of the Cross, it could be used for group 0r personal prayer and reflection.

For those seeking a more intellectual guide, Reforming the Church: Global Perspectives is an award-winning option. Inspired by the Synod on Synodality, this book contains essays from international experts in ecclesiology and pastoral theology. Keeping in mind the global context of the Church, it addresses the issues at the synod as well as wider issues relating to the universal Church. Topics include ecclesial transfiguration

and the episcopacy, clerical sex abuse, globalization of the Church, and the theology of synodality. This book is rooted in the historical context of reform while looking toward the future. An excellent read as we contemplate how to live out synodality in our world.

For further insights on a major issue of our day, readers may be interested in Racism and Structural Sin by Conor M. Kelly. Christians have the responsibility to act justly. Dr. Kelly’s book can help us do just that. Combining academic reflection and pastoral prudence, the author demonstrates both the personal and structural aspects of racism. Writing from a deep conviction that diversity is necessary to affirm the sacredness of every human life, he humbly addresses the racial injustices in the United States in a theological manner. This

book is an invitation, especially for white Catholics, to dialogue humbly and bravely about the sinful structures of racism.

An indispensable resource for researchers, catechists, preachers, and anyone studying the Bible is the Liturgy and Life Study Bible. This amazing resource includes essays from the world’s top liturgical and biblical scholars on a variety of subjects, including Jewish liturgical traditions, psalms as liturgical prayer, early Church worship, social justice, sacraments, the Last Supper, and more. Throughout the biblical text, connections are drawn to how it is used in the liturgy. This resource helped me in the academic setting and also to develop a deeper, more personal appreciation of the connections between liturgy and the Bible.

For those interested in Benedictine studies, The “Lost” Dialogue of Gregory the Great by Carmel Posa, S.G.S., uses the hagiographical method to bring new insight to the life of Saint Scholastica. In this thoroughly researched and carefully footnoted volume, the life of Benedict’s sister is credibly imagined. While women’s stories are often omitted or erased from history, this book centers on Scholastica, providing an enriching history as well as spiritual nourishment.

Another new Benedictine title is Schools for the Lord’s Service, a detailed and inspiring

narrative history of the oldest congregation of Benedictine monasteries in the United States, the American-Cassinese Congregation. For anyone wanting to learn more about Benedictine history in the U.S., this book is for you. Extensively researched and carefully crafted, it is an important contribution to

Benedictine history and truly a work of love.

May these books and others lead us into deeper love of God and neighbor.

Ms. Emily Heidick, is the digital communication graduate assistant at Liturgical Press.

Come to Me, All of You: Stations of the Cross in the Voice of Christ by Amy Ekeh. Art by Gabrielle Rowell. Pages, 40. Liturgical Press 2023.

Liturgy and Life Study Bible edited by Paul Turner and John W. Martens. Foreword by Abbot Primate Gregory J. Polan, O.S.B. Pages, 2312. Liturgical Press 2023.

Living Prayer: A Book of Hours for Renewing Creation by Alison M. Benders, Lisa Fullam, and Gina Hens-Piazza. Pages, 240. Liturgical Press 2024.

The “Lost” Dialogue of Gregory the Great: The Life of Saint Scholastica by Carmel Posa, S.G.S. Foreword by Michael Casey, O.C.S.O. Pages, 132. Liturgical Press 2024.

Pope Francis on Eucharist: 100 Daily Meditations for Adoration, Prayer, and Reflection. Foreword by Cardinal Blase J. Cupich. Pages, 112. Liturgical Press 2023.

Racism and Structural Sin: Confronting Injustice with the Eyes of Faith by Conor M. Kelly. Foreword by Carolyn Y. Woo. Pages, 128. Liturgical Press 2023.

Reforming the Church: Global Perspectives edited by Declan Marmion and Salvador Ryan. Epilogue by Kristin Colberg. Pages, 208. Liturgical Press 2023.

Schools for the Lord’s Service: A History of the American-Cassinese Congregation of Benedictine Monasteries, 1855–2023 by Jerome Oetgen. Pages, 652. Liturgical Press 2024.

To learn more or to order any of these books, visit litpress.org or call 1.800.858.5450.

William Skudlarek, O.S.B.

On 13 March 2013, the newly elected pope from Argentina stepped onto the balcony of Saint Peter’s Basilica and greeted the immense crowd that had gathered in the piazza with a friendly and informal, Fratelli e sorelle, buona sera—“Brothers and sisters, good evening.” Those very first words suggested that we were in for a quite different style of papacy than we were used to. That impression was borne out when, at the end of his address, Pope Francis asked the people of Rome to pray for him, their new bishop, before he blessed them.

The next day there were other indicators that it was not going to be business as usual. Instead of taking a special car that was sent for him, he rode the bus with the other cardinals who were going from their hotel to the Vatican. Once there, he indicated that he intended to move into Casa Santa Marta—a guesthouse for clergy having business with the Holy See—rather than the papal apartments. The reason he gave was that he needed to be with people.

There has been a plethora of articles assessing the ministry of Pope Francis’ first years of service, the majority of which zero in on mercy as the guiding principle of his papacy. The centrality of mercy in the life and ministry of Pope Francis could already be seen in his decision

to keep the motto he had chosen when he became a bishop. He took it from a homily for the feast of Saint Matthew by Saint Bede, an eighth-century English Benedictine, who wrote, “Jesus therefore sees [Matthew] the tax collector, and since he sees by having mercy and by choosing, he says to him, ‘Follow me’” (Matthew 9:9). The motto of Pope Francis consists of three words from that homily, miserando atque eligendo—by having mercy and by choosing.

Pope Francis lives by that motto. Some may remember that shortly after he was elected pope, he granted an interview to the Jesuit journalist Antonio Spadaro, who asked him, “Who is Jorge Mario Bergoglio?” The pope answered, “I am a sinner whom the Lord has looked upon [with mercy].”

Mercy is at the very heart of the covenant God makes with all of humanity. Mercy is what is most characteristic of the ministry of Jesus. Mercy, therefore, must be foremost in everything the ministers of the Church say and do. It is to be offered preferentially to those who have been pushed to the margins and are voiceless, and it is to be offered without any trace of a holier-than-thou attitude or nitpicking criticism.

Early on in Francis’ ministry, he let us see what that kind of mercy looks like in practice. A mere two weeks after his election, he celebrated Holy Thursday at a prison for young

people—where he washed the feet of twelve residents, among whom were two women and two Muslims.

Mercy that is neither condescending nor censorious is what Jesus showed to the Samaritan woman he met at Jacob’s well (John 4:4–29). She had been pushed to the margins three times over: first as a woman, then as a Samaritan, and finally as what might be called a serial polyandrist. Jesus completely disregards the rules that prohibit a Jewish man from associating with a person like that in public. He not only speaks to an ostracized Samaritan woman, he also respectfully asks her to do something for him, to give him a drink of water. He then engages her in conversation, and that conversation concludes with her becoming the first person to whom Jesus reveals his identity as the Messiah.

Some critics of Pope Francis think he overemphasizes mercy at the expense of Church law. One of their main arguments is that the first words Jesus spoke when he began his public ministry were “repent and believe” (Mark 1:14–15). To which, Pope Francis might well reply, “That’s right! And like Jesus, the Church can most effectively call sinners to repentance and faith by first showing them mercy.”

In 2014, a year and a half after becoming pope, Francis was asked by a reporter how he dealt

with his immense popularity. He replied, “I try to think about my sins and my mistakes, lest I have any illusions, since I realize that this is not going to last long, two or three years, and then . . . off to the house of the Father.” He also said that if he no longer felt prepared to go on, he would resign as Pope Benedict XVI did. During a trip to Africa in 2023, Pope Francis was again asked about the possibility of his resigning the papacy, and he replied: “I wrote my resignation [letter] two months after I was elected and delivered [it] to Cardinal Bertone. . . . I did it in case I had some health problem that would prevent me from exercising my ministry, and I [would not be] fully conscious and able to resign. However, this does not at all mean that popes resigning should become, let’s say, a ‘fashion,’ a normal thing. I for the moment do not have [resignation] on my agenda. I believe that the pope’s ministry is ad vitam [for life].”

Let us pray that the remaining years of Pope Francis’ life and ministry be blessed with vigor, wisdom, and above all, mercy— mercy gratefully received, and mercy freely given.

Father William Skudlarek was the Secretary General of the Monastic Interreligious Dialogue from 2007 until 2024

[Jesus said,] “Go and learn the meaning of the words, ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ I did not come to call the righteous but sinners.”

Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg/Wikimedia Commons

The Lord never tires of forgiving. It is we who tire of asking for forgiveness. A little bit of mercy makes the world less cold and more just.

Matthew 9:13 Pope Francis

Cyprian Weaver, O.S.B.

Frère Jacques, Frère Jacques, Dormez-vous? Dormez-vous?

Sonnez les matines! Sonnez les matines! Din, din, don. Din, din, don. Are you sleeping? Are you sleeping?

Brother John, Brother John. Sound the [bells for] Matins!

Sound the [bells for] Matins! Ding, dang, dong. Ding, dang, dong.

Although the French nursery rhyme “Frère Jacques” has been attributed to Jean-Philippe Rameau (c. 1780), it could easily have had its origins centuries earlier. Was our Brother John a lazy, inattentive monk, or had Frère Jacques inadvertently overslept and neglected to arouse the community for the pre-dawn Office of Matins? Or had the timekeeping method used by Brother John failed?

Star Maps. Star maps, although exotic in the modern mind, were far from being agents of error given their basis in structured, orderly, and natural planetary processes. In the High Middle Ages (A.D. 1100–1200) we find evidence that monasteries improved upon and refined this approach to determine time. Saint Peter Damian (1007–1072) noted in his De perfectione monachorum that the significator horarum (sentinel of the hours) should observe the transit of the stars and mark the passage of time by alternate means when “the variety of stars is no longer visible due to the density of clouds.” In Bernard of Cluny’s Consuetudines Cluniacenses (a compilation of monastic practices), the sacristan is identified as the one whose work includes adjusting the clock, noting the time “both in wax and in the course of the stars and of the moon.” The sacristan is also mentioned by Abbot Hugh of Cluny in his Miracula where, after beholding a vision, the sacristan is said to have recalled his duty and went out to observe the stars and decide if it were time to sound the bell. Isidore of Seville likewise

assigns the nocturnal timekeeping specifically to the sacristan in his Regula Isidori (619).

Timekeeping via the heavens was a quotidian facet of the monastic horarium (schedule), which may account for the deeper interest in the subject held by many monks of this era. Gregory of Tours (538–594), in his astronomical treatise De cursu stellarum explained how to use the stars to regulate the timing of the monastic office. Having learned “to trace the course of the stars” from Martinus Capella’s De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii as well as his description of 183 parallel daily circles that the sun travels twice each year, Gregory was able to describe the constellations’ paths across the sky. In De cursu stellarum, cap. 30, for example, he describes the constellation falx (the sickle) as “taking the path which the sun follows in May or August.” He then demonstrates how the stars that appear monthly can be used to determine when monks are to sing and recite the Office of Matins. Furthermore, he instructs the sentinel of the hours to sound the signal for prayer in the month of October by stating: “In October when falx rises, he will know it to be the middle of the night. Nocturns having then been celebrated with the crow of the roosters, you would be able to sing nine psalms antiphonally. Then watch rubeola [the reddish one], so that if the sign for Matins [Lauds] is given when it comes to the second hour of the day, you can then sing ten psalms” (cap. 37). This instruction about Matins is based on yet another facet of the sun’s daily trajectory, that is to wait until rubeola (Arcturus) reaches the place that the sun occupies on the second hour of the day and further demonstrates how the changing daily arcs of the sun provided Gregory with coordinates for describing the nightly motions of the stars (Stephen McCluskey, 2015).

The Abbey of Reichenau was well known because one of its monks, Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054), wrote astronomical works including those on the astrolabe (De utilitatibus astrolabii and De mensura astrolabii). Although not as ubiquitous as the sundial, the astrolabe—an astronomical

instrument that functions as a metal star chart and physical model of the heavens—was reintroduced to Europe during the Middle Ages from second-century B.C. Greek origins. Among the scientific works of Benedictine Gerbert of Aurillac (c. 946–1003), who would become Pope Sylvester II, were those that facilitated the reintroduction of astronomical and mathematical knowledge from the Arabic-Islamic to the Latin-Christian scientific realms of inquiry including the work on the astrolabe (Liber de astrolabio). One of Gerbert’s scholars saw less practical and more spiritual value in its application: “[The astrolabe can be used] to find the true time of day, whether in summer or wintertime, with no ambiguous uncertainty in the reckoning. Yet this seems to be excessive knowledge for general use and seems most suitable for celebrating the daily office of prayer” (On the Uses of the Astrolabe)

Although many star maps and charts from this era are lost to history, one significant source of a monastic star timetable survives: the eleventh-century Horologium stellare monasticum (the only known copy is held by the Bodleian Libraries [Oxford: S.C. 8849, folios 19–23]). The timetable provides precise positions of constellations in relation to the monastic buildings on various days of the year, indicating when the lamps should be lit and the monks awakened. They may be based upon or influenced by the treatise of Gregory of Tours, with the monk using several of the stars chosen by Gregory as guides. The handwritten manuscript dates from the mid-eleventh century in a Benedictine house in France, possibly Fleury. The observations were made from a specific point, the locus designatus in section 6 of the manuscript and in a set direction. The cloister was situated to the south of

the church, with the dormitory on the east side and the refectory on the south side, connected by a corner armarium (cupboard or closet). The dormitory had seven windows, and the refectory had four, which the observer counted from left to right as he stood in the open air of the cloister courtyard, moving from an appointed place to take certain observations. A church of Saint Aignan, possibly an apsidal chapel to the south of the choir of the monastery church, was visible above the north end of the dormitory roof. Apparently from one position in the cloister, the writing over Saint-Aignan’s altar could be seen. The monk likely stood in the cloister courtyard at an appointed place, moving from it to take certain observations. For example, section 6 instructs the observer to move toward the juniper bush along the path to the well to see and count the dormitory windows, suggesting that not all windows were visible from the usual spot. Section 11 directs the observer to look from a northern point and turn south. Section 16 simply says to look south without leaving the usual point. Specific instructions follow depending upon the

feast day. For example: “On the nativity of the Lord [December 25], when you see Gemini lying almost over the dormitory and the constellation Orion above the chapel of All Saints, prepare to ring the bells. On the circumcision of the Lord [January 1], when you see the bright star in the knee of Boötes against the space between the first and second dormitory windows, almost at the top of the roof, then proceed to light the lamps.”

Nonmonastic medieval star maps would continue to become more scientifically rigorous as new constellations were identified and astronomical discoveries were made in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Abbey churches constructed at this time embodied several considerations including the importance of landscape directionality, optimal exposures to sunsets and the west, the focus on the astronomical equinox rather than that indicated by the Julian calendar and the solar position of Michaelmas (September 29) as well as the feast of Saint David (March 1).

These and similar observations of monastic foundations across Europe reveal how buildings were aligned with specific points on the horizon that synchronize with the rising or setting of celestial bodies (such as the sun, planets, stars, or moon) on particular dates throughout the astronomical or liturgical year.

Sundials. This brings us to the subject of the principal horological means of measuring time in use during this period: sundials (and water clocks mentioned early on in this series and with which we’ll conclude this series in the Spring 2025 Abbey Banner). Egyptian in origin (1500 B.C.) sundials were well known in Roman society; according to Pliny, the first record of a sundial in Rome is in 293 B.C. By the first century B.C. there were so many in Rome that one disgruntled citizen wrote: “Let the gods damn the one who invented the hours, . . . who set up a sundial in this city! . . . He has chopped the day into slices. When I was young, there was no other clock but my belly. . . . Now we [eat] when it pleases the sun.”

Both sundials and water clocks were being introduced and used in the monasteries of the later Middle Ages. Cassiodorus (A.D. 490–585), of the monastery Vivarium in southern Italy, wrote in his Institutes: “Nor have we by any means allowed you to be unacquainted with the hour meters which have been discovered to be very useful. . . . I have provided a sundial for you for bright days, and a water clock that points out the hour continually both day and night, since on some days the bright sun is frequently absent. . . . And so the art of man has brought into harmony elements that are naturally separated; the hour meters are so reliable that you consider an act of either as having been arranged by messengers. These instruments, then, have been provided in order that [monks] may be summoned to the carrying out of their divine task as if by sounding trumpets.”

Venerable Bede (c. 673–735), Anglo-Saxon Benedictine monk, made significant contributions to the understanding of time and its measurement

Roger Griffith/Wikimedia Commons

During a 1771 renovation, the 11th century Saxon sundial at St Gregory’s Minster, Kirkdale in North Yorkshire, England, was discovered. Two panels (above) bearing a rare inscription in Old English flank the sundial. Translation: “Orm Gamal’s son bought St Gregory’s Minster when it was all broken down and made it new from the ground, for Christ and St Gregory. In Edward’s day king, in Tosti’s day Earl. This is the days sun marker at each tide [division of time]. Howard wrought me and Brand (priest).”

during the early Middle Ages. His De temporibus (703) and a more detailed De temporibus liber secundus (725) were written in part for his fellow monks who needed to understand the basis of calculating the date of Easter and how to construct a liturgical calendar. In determining time by interpreting the length of shadows, he promoted the use of canonical sundials to fix the time of monastic prayers. Pope Sabinian allegedly issued a decree in 606 stipulating that sundials be placed on churches in order to designate the times for prayer. Sundials appeared on medieval churches with greater frequency from the seventh century onward, often announcing Mass times as in the case of the Mass dial on the church in Kirkdale, Yorkshire (c. 1063). Built in the eighth century, the sundial etched on Bewcastle Cross tells the time according to the five prayer periods of the day: Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers. The twelve hours between dawn and sunset are further separated on the dial.

Small, portable sundials were popular in the Middle Ages, especially among the merchant classes. Would this sign of material success have been found among monks? Alas, this may have

been the case, in particular among the lesser paragons of monastic virtue. In the “Shipman’s Tale” of The Canterbury Tales (1387–1400), the narrator relates how a rich merchant is cheated by a monk, stealing both his wife and then his money. The monk invites the wife to dinner stating: And lat us dyne as soone as that ye may; for by my chilyndre it is pryme of day. The chilyndre (cylinder) represents a form of sundial (called a pillar sundial or shepherd’s dial) that is small and easily carried in the pocket. While the monk may very well be guilty of a serious infraction of his vow of chastity, his possession of a pillar sundial considerably less so. The earliest description of a pillar sundial was written by Hermannus Contractus, the Benedictine from Reichenau, who called it a cylindrus horarius. It is a sundial that measures the height of the sun making it particularly convenient for travelers—such as monks attending to errands outside the cloister— who need only to place themselves along their own meridian.

Father Cyprian Weaver, O.S.B., a research scholar in the role of neuroendocrinology in regenerative and genomic medicine, is a retired associate professor of medicine, cardiology, at the University of Minnesota.

Gary Osberg

Fifteen years ago (16 April 2009), we buried Brother Willie in the Saint John’s cemetery. In June of 2008 we had celebrated Brother Willie’s 92nd birthday in his room in the abbey retirement center. I brought him a choice of a cold bottle of O’Doul’s or a cold bottle of Budweiser. He chose the Budweiser.

It was in 2001 that I first noticed an old man kind of shuffling toward Wimmer Hall where the studio of Minnesota Public Radio is located. I stopped and introduced myself. I asked him what he did, and he responded in a gruff voice, “My name is Brother Willie, and I work in the woodshop. I make a table and chair set, haven’t you seen them? They are for little ones.” Since I had a six-year-old granddaughter at the time, I asked him if he would make a set for me. “Oh, I don’t know; there are many orders ahead of yours. I don’t know if I will live long enough to make a set for you.” I responded, “No problem. I will pray for you every day, and I am sure that you will live long enough to make them.”

I visited Brother Willie in the woodshop many times. The first time I noticed a small wooden wagon filled with blocks. He made the blocks out of scraps of oak wood. Most likely the oak had been harvested from the abbey forest. I always left him

one of my calling cards and reminded him of my order for the table and chairs. One day the phone rang, and it was Brother Willie. My table and chair set was finished. Over the years I took delivery of two children’s table and chair sets plus eight of the small wagons filled with blocks of many shapes and sizes. Years later Brother Willie had to stop working in the woodshop, but he still would make his rounds going through the garbage dumpsters searching for aluminum cans. He donated the money from the cans to the poor.

Brother Willie was best known for his role as night watchman on campus. The pub in Sexton Commons is named after him, and George Maurer wrote a song named “The Brother Willie Shuffle.” He was a great man, and he is missed.

My friend Dave Phipps drew the caricature above, and you can purchase a T-shirt with the same at the Saint John’s Abbey Gift Shop in the Great Hall at Saint John’s.

Mr. Gary M. Osberg is senior account executive for Minnesota Public Radio.

Success has nothing to do with what you gain for yourself. Success is what you do for others.

Brother Willie (William Jerome Borgerding, O.S.B. [1916–2009])

On October 11, prior to the seventeenth firing of the Johnanna Kiln at The Saint John’s Pottery, hundreds of guests were serenaded by Mr. John McCutcheon followed by a prayer of blessing by Abbot Douglas Mullin. Master potter and Artist-in-Residence Mr. Richard Bresnahan welcomed the assembly and noted that the ceremony was dedicated to three individuals who have passed since the last firing in 2022: Bill Smith, Mary Lee Neu, and Raghavan Iyer. The firing lasted for ten days and included thousands of pieces of pottery and sculpture by some thirty artists. Dedicated in 1994 and first fired in 1995, the Johanna Kiln, the largest wood-burning kiln in North America, was designed and built by Mr. Bresnahan and honors Sister Johanna Becker, his teacher and mentor.

The kiln is ritually purified in Japanese tradition with rice, salt, and sake, then lit with handmade torches.

Photos: Tom Morris

The daily routine within the cloister is enlivened by the antics of the “characters” of the community. Here are stories from the Monastic Mischief file.

Christmas Cheer

I don’t want to dampen your holiday spirits, Brother, but aren’t these Christmas cookies a little soggy? They’re supposed to be soggy, Father. I haven’t baked them yet.

Nice Day

Have a nice day, Father. I have other plans, thank you. Pat McDarby

Wow! What a day! What a blessing! The sun is shining. The humidity is low. The birds are singing. It’s just perfect. Yah, if you like that kind of stuff. Paul Fitt

Evolution

He was born ignorant, and he’s been losing ground ever since.

Theology 102

Following a lengthy and highly detailed explanation of a complex theological issue, Father Philibert asked his audience if there were any questions. From the back of the room, a woman raised her hand and said: “Father, could you please put that cookie jar on a lower shelf?”

Religious Insight

Sister John Agnes said to us in fifth grade:

“Empty barrels make the most noise.”

Brother Richard

Brother Johann, after sixty-eight years of faithful service as a monk, was in declining health. Now bedridden, his medical team judged that he had only a few more days, perhaps hours, to live.