Royal Provenance

S.J. Shrubsole

Photography by Steven Tucker and James McConnaughy

Text by Ben Miller with contributions from Tim Martin

ROYAL PROVENANCE PROPERTIES AND GIFTS FROM KINGS AND QUEENS S.J. Shrubsole 26 East 81st Street New York, NY 11216 Tel: 212-753-8920 inquiries@shrubsole.com www.shrubsole.com

Copyright 2023 S.J. Shrubsole,

©

Corp.

Around the time I joined the firm in 2015, Shrubsole window displays used to include little signs in front of each object, announcing “George III”, next to a Hester Bateman epergne; “Charles II”, announcing a capacious tankard; or “Queen Anne”, describing a sleek octagonal teapot. You, oh erudite reader of catalogs, know what we meant: the epergne was made during the reign of King George III (1760-1820), the tankard while King Charles II ruled (1660-1685), and the teapot under Queen Anne (1702-1714).

Our windows and our shop, however, are open to the public, even to neophytes who sometimes inferred a different meaning, one often expressed with wide eyes and mouth agape: “Did all this stuff really belong to King George??” These inquiries increased over the years until we finally acquiesced. Today our labels report pedantics like a year and city of origin, a maker’s name, and even crass details like the price.

But the truth is, the neophytes’ astonishment was not always misplaced. Because while much of the fine English silver we handle was merely made during the reign of one or another King or Queen, it’s not uncommon to find pieces on our shelves that really did belong to a Royal. And sometimes these pieces really do warrant wide eyes and gaping mouths, even among erudite catalog readers.

Though Shrubsole began in England, we are today an American firm. Despite occassional whiffs of anglophilia, none of us awoke at 3am to watch the coronation. The mere mention of royalty does not set our hearts aflutter. What does set

our hearts aflutter is the artistry of the very finest pieces of silver in the world. It so happens that the wealthiest patrons, and therefore the owners of the finest pieces, were often those who had command over the full resources of the state. In other words, royalty.

Silver, don’t forget, could be an astonishingly expensive investment. The sums regularly exchanged with and among silversmiths were so large that in 1668, Samuel Pepys writes of using a smith’s £600 paper note in lieu of currency (one of the early recorded uses of paper money). In 1674, King Charles II ordered a silver bed for his mistress Nell Gwyn from the silversmith John Cooqus at a cost of around £1000. By comparison, in 1672, a chief bailiff in Warwickshire earned an annual salary of £4 ½.

For the King, a significant purchase of silver was often more than just a personal luxury. It was a necessity of leadership. Authority, and therefore political stability, depended on the aura of power and prestige. The trappings of the throne were conceived around one goal: cow anyone in the presence of the monarch. Gifts given by the King or Queen similarly needed to communicate the largesse and opulence of the position. Silver with its inherent sparkle and spectacle was arguably the very best medium to deliver that message, especially as the material itself was instantly convertible to money. When Nell Gwyn needed to settle her considerable debts, that wonderful bed went straight to the smelter.

These qualities of fungibility and transience explain a great deal about the history of silver, including the frequency with which these

royal pieces left their original homes. Some were commissioned by the crown to be given as gifts, recognition of services rendered by some ambitious (but not too ambitious) noble. Others were inherited over successive generations of royalty until they slipped the clutches. Despite all this attrition, the Royal Collection and the National Trust comprise millions of objects and more every day. I don’t think today’s monarchy is worried that they haven’t enough fine silver—though if you are reading this, your Highness, please know that we have reserved a special discount just for you.

Ben Miller Director of Research

S.J. Shrubsole | New York 3

TEA URN, 1790

BY EDWARD FERNELL

GIFT FROM QUEEN CHARLOTTE TO JULIE DE MONTMOLLIN

Height: 23 in.; Weight: 117 oz.

The first marital instruction King George III gave to his newly minted German bride was “not to meddle” in politics or the affairs of state. Only seventeen, and not an English speaker, the new Queen of Great Britain and Ireland might have found this patronizing order redundant. But with time, Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz—Queen Charlotte— developed a voice and an influence. Even before her husband’s descent into illness, she catalyzed British involvement in the War of Bavarian Succession. And as George lost his faculties, Charlotte feuded with her son (the future George IV) over the right to be the King’s Regent.

One of Charlotte’s principal occupations was the raising of her children, and she maintained close relationships with their tutors and attendants. Among these was Julie de Montmollin (1765-1841), who instructed the youngest daughters (Sophia, Amelia and Mary) in needlework and French. The girls became quite adept at lacemaking, crochet work and all kinds of fine embroidery.

In 1790, Charlotte gave Julie this superb tea urn, engraved with Charlotte’s monogram on the front and Julie’s on the back. It was no small token. The material value of the silver alone amounted to around £30 at a time when annual income for the comfortable middle class was in the range of £100.

We can’t know why the urn was presented. French was obviously an important subject, and needlework too was dear to the Queen‘s heart. Many of the women in Charlotte‘s inner circle at court were

members of the Blue Stockings Society, intellectual wom en, like Elizabeth Harcourt, Fanny Burney, and Mary Cavendish, who met over needlework to discuss literature and art, sometimes with male guests like Edmund Burke, Horace Walpole, and Dr. John son. Charlotte funded a school of needlework work from 1772 to 1818, so clearly this aspect of her daughters’ education was important to her. Finally, it’s possible, given the date of the gift, that it was presented out of gratitude for Julie’s company and support during King George’s first, terrifying bout of illness at Kew in 1788–89.

Shrubsole acquired this piece first in the 1950s, then selling it to the Lipton Tea Company, which included it in a series of exhibitions of tea wares at museums across the country. It’s a superb example of neoclassical design, and we’re delighted to offer it again, now seventy years later.

The Lipton Tea Company, Hoboken, NJ, since

The Lipton Collection, The Portland Museum of Art, Feb-March, 1954, no. 74

An Exhibition of the Lipton Collection of Antique English Silver, Henry Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, CA, Jan-Feb. 1956, no. 43, p. 21

The Lipton Collection: Antique English Silver Designed for the Serving of Tea, The Dayton Art Institute, Oct. 1958, no 83

5

PAIR OF CANDELABRA, 1774

BY THOMAS HEMING

BY THOMAS HEMING

CHRISTENING GIFT FROM KING GEORGE III TO THE EARL OF JERSEY

Height: 14 1/4 in.; Weight: 118 oz. 4 dwt.

Gifts are a crucial tool in the diplomatic kit, a way to cement good relations or salvage bad ones. Even after the erosion of feudalism in England, the order and stability of society depended on strong and reliable relationships between royalty and aristocracy. Thus gift giving remained an important component of statecraft, from diplomatic gifts to foreign leaders,

to courtesy gifts for members of the nobility.

These candelabra are an exceptional example of the latter: a gift from George III to the son and heir of the Earl of Jersey upon his christening in 1774. It wasn’t unusual for the King to give an extravagant christening gift to one of his godchildren, but these large, heavy, and beautiful candelabra must have been a gratifying gesture.

A record of this gift, together with a pair of snuffers and pan, survives in the Jewel Office Accounts and Receipt book, 1767-1782, as follows:

Itm. Rec’ed one pair of gilt Candlesticks and Branches and Nozzles and one pair of Snuffers and Pan wt. 130oz 7dwt at [£]10 3d per oz [Total] [£]66 16[s] 2[d]

6 S.J. Shrubsole | New York

They are also recorded in the Jewel Office Delivery Book, 1732-1796:

June 14th [1774] Delivered to the right honourable the Earl of Jersey as a Gift from His Majesty at the Christening of his Child. Impris one pair of Candlesticks and Branches gilt wt. 119[oz]7[dwt]Itm one pair of snuffers and Pan gilt wt. 11[oz] John Webb for The Earl of Jersey

You will notice they are no longer gilt, and we presume the gilding was removed by a subsequent owner—miraculously not leaving a trace.

Their design is based on a French model by the famous silversmith Robert Auguste (one of which, from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is pictured below). They were executed by one of King George’s favorite artisans, Royal Goldsmith Thomas Heming.

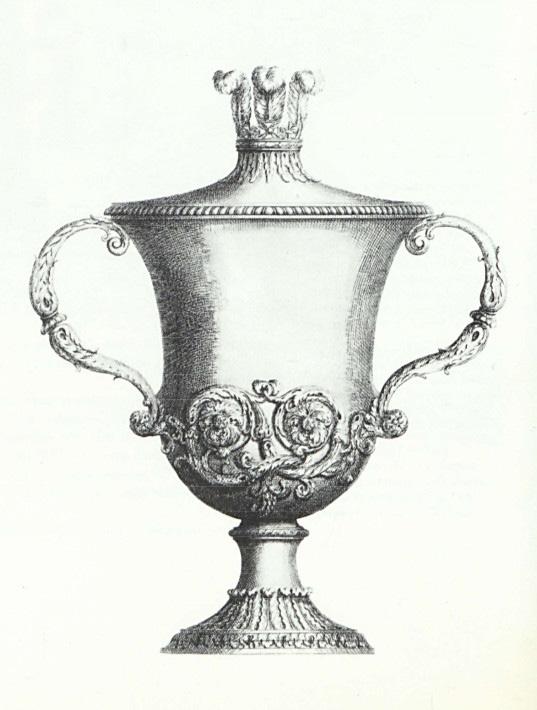

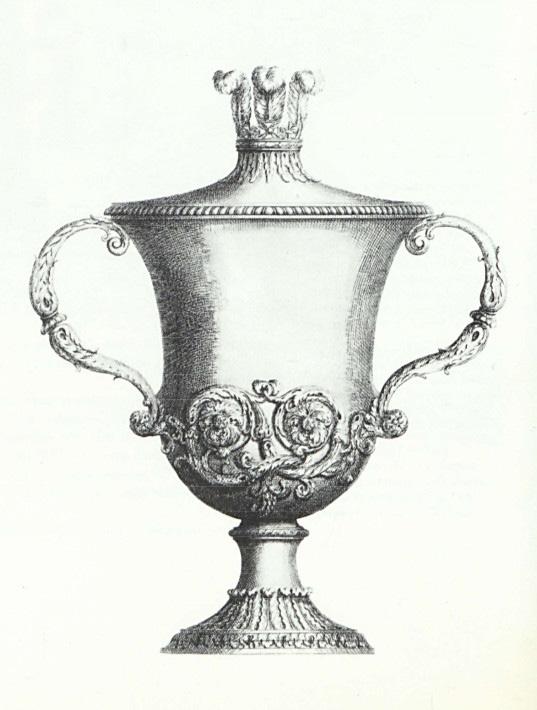

CUP & COVER, 1761

BY THOMAS HEMING

BY THOMAS HEMING

GIFT FROM KING GEORGE III TO GEORGE FERDINAND FITZROY

Height: 13 in.; Weight: 73 oz.

This stately christening gift is based on a design (right) by famed architect and designer William Kent. Its recipient was the newborn son of Lt. General Charles FitzRoy, 1st Baron Southampton. Charles had become a member of parliament in 1759 and then Groom of the Bedchamber. This position close to the King probably explains the monarch’s selection of such a beautiful gift, which is recorded in the Jewel House records:

Decr 17th [1761] Delivered to Charles Fitzroy Esqr. as a Gift from his Majesty at the Christening of his Child, impris one gilt Cup and Cover wt 73[oz] 3 [dwt]...

Inside the cover is engraved the following:

This Cup was Given by George the 3rd to George Ferdinand FitzRoy Born August ye 7 1761. His Majesty Standing Godfather Sept 16

The design, first executed by George Wickes for Colonel Pelham in 1736, remained a favorite for royal christening gifts through the 1770s. The plumed finial on the original design is the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales. This example, having been given by the king, has the royal crown instead.

The royal arms are engraved on one side (above left), while naturally the other side bears the arms of Fitzroy (below left).

Attesting to the extraordinary condition of this piece, its weight has been reduced by a mere three pennyweights over 250 years.

S.J. Shrubsole | New York 9

MAHOGANY AND BRASS BREAKFAST TABLE, C. 1820

BY JOHN MCLEAN

BY JOHN MCLEAN

FROM KING GEORGE IV’S FURNISHINGS AT WINDSOR CASTLE

Length: 60 in.; Width: 44 ½ in.; Height: 28 ¾ in.

King George IV purchased this table for Windsor Castle. It bears his monogram “G IV R” and an inventory mark (55) on the underside. Around 1845 it was brought to Brighton Pavilion and was used there until Queen Victoria sold the property to the city of Brighton in 1850. The table returned to Windsor, where it remained until sold by Queen Mary, sometime in the 1950s. In 1880 the table was photographed in the Audience Chamber at Windsor (below right), likely by photographer John Wesley Livingston. The table is visible in front of the sofa.

John McLean (1770 -1825) was an English furniture maker and designer who is recognized as one of the best of his era. His clients included the 5th Earl of Jersey (see pp. 6-7), for whom he worked extensively at Middleton Park, Oxfordshire, and the Earl’s London mansion in Berkeley Square. McLean gained a notable mention in Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet Dictionary in 1803: one of the “fashionable Pieces of Cabinet Furniture” included a “Pouch Table”, whose design was taken and “executed by Mr. M’Lean in Mary-le-bone street, near Tottenham court road, who finishes these small articles in the neatest manner”. Examples of his furniture can be found in the Victoria & Albert Museum, The California Palace of the Legion of Honor and the Library at Saltram, Devon.

We are grateful to Dr. Alexandra Loske, Curator of the Royal Pavilion, Brighton, for her assistance in researching this piece.

Provenance:

• King George IV thence by descent to

• Queen Mary, by whom sold to

• Mallet, Ltd.

• Lord Leverhulme

• Jonathan Harris, Works of Art, Ltd., London

• American private collection

10

BUN” TRAVELING CHAMBERSTICKS, 1809

BY WILLIAM GOULD

BEARING THE MONOGRAM OF QUEEN CHARLOTTE

Diameter: 6 ½ in.; Weight: 40 oz. 11 dwt.

The origins of the term “Brighton bun” to refer to this distinctive form of traveling chamberstick seems to have been lost to the mists of time. Perhaps when screwed together for storage, their toroidal shape resembled some fashionable pastry from Brighton. There is indeed such a thing as a Brighton bun pastry, but today at least it is a rough scone-like concoction, not a smooth donut like these chambersticks. A donut historian may be needed to shed light on this puzzle.

In any case, the form seems to have emerged in the 18th century. It was a clever solution to the problem of transporting breakable and difficult-to-pack chambersticks. Examples in wood and brass are common, while silver ones are much rarer. All were originally fitted with an interior of wood or baize and an outer leather case, but we’ve only rarely seen such fully intact examples. These are among the largest and heaviest such chambersticks known.

“BRIGHTON

PAIR OF CUFFLINKS, C. 1950 BY

ZIVY FRÈRES

BEARING THE CROWN OF THE LAST KING OF EGYPT

Farouk bin Fuad was only sixteen when he succeeded to the throne of Egypt in 1936. He couldn’t have known then that his reign would end not only in disgrace, but the complete dissolution of the Egyptian monarchy. And while it’s true that his expulsion stemmed from political and cultural forces beyond his control, it probably didn’t help that Farouk became an indefatigable spendthrift. His indulgences included a $2 million private train, hundreds of cars, jewels from Harry Winston, endless palaces, a world-famous numismatic collection, and an oyster-eating habit said to amount to 600 a week. Farouk may not have been well suited for the throne, but the throne certainly suited him.

In 1954, the deposed and exiled king’s coins were sold by the new government of Egypt in a hurried and chaotic auction which is estimated to have earned perhaps 10% of the true value of the collection. Numerous coin dealers built careers off that sale.

Among Farouk’s lucky jewelers were Zivy Frères, based in Alexandria with offices in Cairo and Paris. The firm made this pair of cufflinks with the royal crown for the King, either for his personal use or to be given as a gift. In gold and platinum and set with rubies and diamonds.

S.J. Shrubsole | New York 13

A picture worth a thousand words.

CIBORIUM, 1686

BY

JOHN COOQUS

FROM THE ROYAL CHAPELS OF KING JAMES II

Height: 10 in.; Weight: 28 oz. 2 dwt.

This beautiful and perfectly preserved ciborium is one of the most exciting discoveries we have made in recent years.

A ciborium is a vessel used to hold the host during Catholic communion services. It is exclusively a Catholic vessel, so to find one in England, where Catholicism was (with certain exceptions) practiced furtively for centuries, is extremely rare. Among hundreds, perhaps thousands of communion cups and patens, there are only five surviving English silver ciboria prior to 1700.

But what makes it royal?

Well, the evidence is circumstantial, but we are in no doubt that this object was made in 1686 as part of a large commission for the last Catholic King of England, James II. As Polonius would say, perpend:

The silversmith who made the ciborium was John Cooqus, son-inlaw of the great Dutch silversmith Christian van Vianen, one of the Royal Goldsmiths to Charles II. On van Vianen’s death in 1667, Cooqus became a Royal Goldsmith himself, serving under Charles II and subsequently James II.

Upon his accession in 1685, James set about converting the Chapels Royal at Whitehall, Dublin, Windsor, and Holyrood to Catholic chapels, partly by provisioning the chapels with the altar plate necessary for Catholic ritual. We know from the records of the Secret Service (a seventeenth century network of espionage and finance that managed certain personal expenses for the King) that his agents ordered much of this plate, naturally, from Cooqus.

In the tumult leading up to the Glorious Revolution, these Catholic chapels were dismantled, in some cases looted and defaced, and most of the altar plate was lost. Prior to the discovery of this ciborium, the only altar plate known to survive from these chapels was the set from Holyrood, which had been saved by a daring and indefatigable priest and hidden in a nunnery for nearly three hundred years. That set includes two pieces

marked by Cooqus.

It’s almost impossible that anyone other than the King would have been the customer for this ciborium. Even if by some remote chance another of England’s small number of wealthy Catholic families had ordered a ciborium just at this time, the odds of their ordering it from Cooqus are next to nil.

Add to these weighty circumstances the additional fact that a Royal commission is the best explanation for an object to bear the maker’s mark only, as this does, and the conclusion is inescapable: this ciborium is a long lost part of the last royal Catholic commission, once part of the altar plate for the either Windsor, Whitehall, or (less likely) Dublin.

A final detail: on the outside of the cup, in line with the crucifix below, there is faint but unmistakable evidence of an erasure. Originally, we believe, the royal monogram was engraved here, removed at a later date to reduce the odds of the object’s being recognized.

Also not wishing to be recognized, the King fled to France. He was deemed by Parliament to have “vacated” the throne. His sister Mary, and her husband, the Protestant William of Orange, took the throne in 1688, and England’s slow and painful renunciation of Catholicism was complete.

S.J. Shrubsole | New York 15

BRAZIER, C. 1695

BY DANIEL GARNIER

FOR GEORGE LOUIS, ELECTOR OF HANOVER, LATER KING GEORGE I

Length: 16 1/4 in.; Weight: 67 oz.

This massive piece, made in London around 1690 by a great Huguenot goldsmith, was sold some years ago from the royal house of Hanover. It bears the monogram of Georg Louis, elector of Hanover and later King George I of England.

Braziers are generally very rare in English silver. Having been replaced entirely by the dish cross and dish ring by the middle of the 18th century, the vast majority were melted down.

16 S.J. Shrubsole | New York

PAIR OF CANDLESTICKS, AUGSBURG, C. 1720

FROM THE ROYAL HOUSE OF HANOVER

Height: 8 in.; Weight: 25 oz. 13 dwt.

German silver comes through our shop now and again, but of course it isn’t our area of specialty. Nevertheless, this pair is beautiful, rare, and à propos. Like the brazier opposite, they were made for the Electors of Hanover, who were to become English monarchs.

This pair was sold from the Royal House of Hanover in the early 2000s and bear the monogram CL beneath an Elector’s bonnet. Were it GL, we would know they were for Elector Georg Louis (King of England from 1714). Any attributions of this monogram would be appreciated.

SCULPTURAL MODEL OF THE GREYHOUND EOS, 1841

BY ROBERT GARRARD

GIFT FROM QUEEN VICTORIA TO PRINCE ALBERT

Length: 10 in.; Weight: 39 oz. 2 dwt.

This remarkable statuette, representing Prince Albert’s beloved greyhound, Eos, was commissioned by Queen Victoria from Garrard in early 1840. She presented it to Albert on his twenty first birthday, August 26th, 1840. The couple had been married only six months, and this was the first birthday she shared with him. Albert was utterly devoted to Eos; he had written ahead from Germany to “introduce” her to the Queen, noting that “Eos is particularly friendly when there is plumcake in the room.”

The Queen hired Garrard, who in turn hired a sculptor named Edmund Cotterill, to produce this perfectly faithful rendering.

It was a success. Victoria mentions it in her private diary on August 26, 1840: “These I give him (from myself), a fine opal set with diamonds, a silver figure of Eos, a Field Marshal’s Baton… with all of which he was much pleased”. A good thing too, as the Queen had already hired the artist Edwin Landseer to begin work on a portrait of Eos, now in the Royal Collection, which she would give Albert for Christmas.

This being a very important commission for Garrard, Cotterill took special care with it: the delicacy and exactitude of the modelling is superb. Garrard took pride in the piece, stamping it with both the sculptor’s name and the date. No doubt the success of this commission

helped Garrard become the Royal Goldsmith in 1843.

Eos was one of the most beloved dogs in the history of the royal family. In addition to several portrayals by Landseer, her figure was incorporated into other silver pieces by Garrard, including an inkstand of 1842 and a massive table centerpiece of 1843, which was designed by Albert and featured not only Eos but three of Victoria’s favorite dogs.

The order for this piece is recorded in Garrard’s ledgers (now kept at the Victoria & Albert Museum) and reads:

A model of a greyhound in silver on a black stand – 40 oz - £42 5s

With case (morocco leather with 2 gold buttons, lined in silk velvet) - £4

Next to that is the name of the client—that minor detail which makes this not just a beautiful little statuette, but a token of one of history’s greatest love stories.

SET OF SIX PLATES, 1725, BY DAVID WILLAUME

MADE OF SILVER FROM THE INDENTURE PLATE OF THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS

Diameter: 9 ¾ in.; Weight: 112 oz. 16 dwt.

It was common practice for high public officials to receive “indenture plate” on taking office. This was a loan of silver from the crown meant to assist these officials in executing their duties, which of course included wining and dining. By law this silver was to be returned at the end of their term, but by custom it was often kept as a (prestigious and very expensive) memento of public service.

These six plates date to 1725 and bear the crest of John Smith, who was Speaker of the House of Commons from 1704-1708. But they are also engraved with the royal arms of Queen Anne, whose reign had ended eleven years before the plates were made. The reason for this apparent anachronism is another custom that can sometimes be seen vis-à-vis indenture plate: the original silver was melted and refashioned (to keep up with the times), but the new pieces were engraved with the original royal arms to maintain the memory and prestige of their origin.

Smith had received 4000 ounces of silver on his election to the Speakership. These six plates account for a little less than 3% of the total.

20 S.J. Shrubsole | New York

ARGYLE, 1775

BY SEBASTIAN & JAMES CRESPEL

GIFT FROM KING GEORGE III TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE AMERICAN COLONIES

Height: 5 1/8 in.; Weight: 13 oz. 15 dwt.

Michael Clayton writes of the argyle: “Today, many would question its effectiveness.” As one might say the same about an Italian sports car, I interpret this remark as a compliment. Certainly the form was popular and successful for many decades, beginning with their ostensible invention by the 3rd Duke of Argyll in the mid-18th century. Its function was to keep gravy warm at the table through the use of a separate compartment full of hot water.

This argyle’s original owner was William Legge, Secretary of State for the American Colonies during the runup to the Revolution. Though sympathetic to the colonists, he failed to reach an accord between them and Parliament, finally resigning his position when war seemed inevitable.

Provenance:

• Issued by the Jewel House to William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth (1731-1801), by descent to

• Gerald Legge, 9th Earl of Dartmouth (19241997) who married, as his 1st wife, Raine, later Countess Spencer and step-mother of Diana, Princess of Wales

• The Albert Collection

• Sotheby’s, London, 4 June 2008, lot 238

S.J. Shrubsole | New York 21

SAUCE LADLE, 1765

BY JOHN HARVEY

BY JOHN HARVEY

BEARING THE MONOGRAM OF KING GEORGE III AND THE ROYAL ARMS

Length: 7 ½ in.; Weight: 3 oz. 1 dwt.

A fine sauce lade, engraved on the wide heel with the royal crown and the initials GR (George Rex) flanking the royal arms.

Provenance:

• The Eric N. Shrubsole Collection

(Opposite)

FOURTEEN TABLESPOONS, 1744

BY PHILIP ROKER

BEARING THE CYPHER OF KING GEORGE II

Length: 8 in.

Each engraved with a mirror cypher GR within the garter motto and below a royal crown.

22 S.J. Shrubsole | New York

BY THOMAS HEMING

BY THOMAS HEMING

BY THOMAS HEMING

BY THOMAS HEMING

BY JOHN MCLEAN

BY JOHN MCLEAN

BY JOHN HARVEY

BY JOHN HARVEY