For D’Hania Hunt, election night was not just about tracking who would represent her in Congress. As votes rolled in, the watch party she attended quickly became a victory party. By the end of the night, she had become the proud sister of Congressman-elect Wesley Hunt (‘00).

The celebration was especially sweet because Hunt was defeated in 2020 by fellow St. John’s alum Lizzie Fletcher (‘93).

When Hunt's 2022 race was o cially called, a live band played the “Top Gun” anthem, which honored his eight years as an Army aviation branch o cer and helicopter pilot, as well as his political success.

“The rst time around it wasn't his time, but he grew a lot as an individual,” Director of Community Engagement D’Hania Hunt said. “A lot of people have been supporting Wesley for the last three years, so it was a very joyous occasion.”

Due to redistricting in fall 2021, Fletcher and Hunt

avoided a rematch: Fletcher remained in TX-07, and Hunt ran in TX-38, one of two new congressional districts granted to Texas. The redistricting was a major point of dispute during the election cycle. Both districts include small, densely populated swatches on land inside the Loop o set by large plots of land in the suburbs. Senior Luke Romere saw redistricting as a positive.

“It works to the bene t of the majority of people in those districts,” he said. “Most of them are going to be represented by a candidate that they feel actually represents their values.”

Although redistricting bene ted both Hunt and Fletcher, it remains a point of contention. History teacher Eleanor Cannon sees gerrymandering as a bipartisan issue that rewards the political fringe.

“When parties are controlled by the extreme elements, it's not healthy for the parties,” Cannon said. “If the district is contested, you have to moderate your views to win over moderate people.”

Fletcher’s opponent, Johnny Teague, ran as a “pro-Second Amendment, Pro-Life, small-government candidate.” He also gained national attention for self-publishing a book, “The Lost Diary of Anne Frank," in which he imagined her irtations with Christianity while in a concentration camp.

Hunt’s opponent, Duncan Klussmann, a long-time Spring Branch ISD superintendent, ran on a platform based on education, mental health services and voting access.

Both Fletcher and Hunt won handily, by 29 and 28 points, respectively.

calling voters.

“The e ective conversations really make the time worth it,” Mostyn said. “Just reaching out from a candidate's team can make them feel special.”

History teacher Amy Malin works as a Volunteer Deputy Voter Registrar. Every two years, she attends a certi cation training session to register voters and also coordinates a voter registration table at Club Fair.

Ru Natarajan, precinct chair and great aunt of junior Shaheen Merchant, just completed a stint as Community Outreach Liaison on the Hidalgo campaign. She focused on getting more Democrats elected to local positions, working not only for Hidalgo but supporting candidates across Harris County.

AVA MOSTYN“Elections are important everywhere,” Natarajan said. “But it's the local elected o cials that make the decisions in your neighborhood.”

Now that all Senate and House races have been decided, Republicans picked up eight seats in the House, a far cry from the “red wave" that many predicted. The Democrats have extended their Senate majority to 51-49 after John Fetterman’s victory in Pennsylvania and incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock’s runo win in Georgia.

In Texas, very little changed. The races for state leadership all went to incumbent Republicans. In Harris County, Hidalgo narrowly won a second term despite a massive ad campaign supported by Jim “Mattress Mack” McIngvale and an endorsement from the Houston Chronicle of her opponent, Alexandra del Moral Mealer.

Hunt and Fletcher represent opposing ideologies and, quite literally, the geographic division of St. John’s — The Upper School Campus is located in Hunt's district, while the Lower and Middle schools reside in Fletcher's domain.

Romere says the civil manner of both representatives re ects the political diversity at St. John’s. Even though he has di erent opinions with some of his closest friends, it has not impacted his friendships.

Romere has volunteered on both Hunt campaigns. After the disappointment in 2020, he started working toward the next election by phone-banking and block-walking.

Although most high school students cannot yet vote, there was no shortage of political involvement. Junior Ava Mostyn and senior Lia Symer recruited students to phone-bank for County Judge Lina Hidalgo through the school’s Young Liberals Organization, which also organized letter-writing events to support local Democrats and gubernatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke.

Mostyn strived to have meaningful discussions while

After most races were called, YLO encouraged their members to stay informed with the election results. A week before the runo election in Georgia, they organized an event to write postcards and show students easy ways to get politically involved.

Mostyn observes a “vibrant political community” at St. John’s with “lots of di erent ideas and lots of active people.” She points to the Student Political Education Club, which teaches students how to have “civilized political discussions,” as well as YLO and the Young Conservatives Club, which allow students to “be around like-minded people” and support their party.

Mostyn also lauded the e orts to extend courtesy to people with di erent beliefs, speci cally by the rst two alumni representatives.

She noted that while Fletcher and Hunt aren’t always aligned, “they are able to communicate when needed,” which could be partially due to their St. John’s education.

“We’re taught to have powerful political conversations,” Mostyn said, “even with people that you don't agree with.”

Elections are important everywhere, but it's the local elected officials that make the decisions in your neighborhood.

RUFI NATARAJAN, PRECINCT CHAIR

We’re taught to have powerful political conversations, even with people you don't agree with.

For the last two years, St. John’s ranked as the best Houston-area private high school according to Niche. But when the rankings came out in September, the School dropped to 7th.

Awty International School jumped to rst, while SJS fell seven spots — behind John Cooper (2nd), The Village School (3rd), Kinkaid (4th), Strake Jesuit (5th) and St. Agnes (6th).

Niche is a ranking site that annually publishes lists of the best schools, from kindergarten to graduate school, attracting interest from prospective students and parents — and confusion from those who feel their school has been snubbed.

Niche rankings take into account student, teacher and parent reviews, along with data and other user-generated input to make their rankings and “report cards,” which distill various aspects of campus life into a letter grade. Niche compares the average standardized scores and generates their grades based on standard deviation.

On the Niche report card, St. John’s dropped in only two of the 12 categories: Teachers and Clubs & Activities, going from an A+ to an A, even though there is no quanti able di erence on campus. Assistant Dean of Students Lori Fryman tracks the number of clubs and their leaders, but she does not track student participation, and is "not sure how they quantify student participation in clubs."

“All I can think of is that they check the student life section of the website to see how many options are o ered,” Fryman said.

When asked to clarify how they arrive at their rankings, Niche’s Senior Public Relations Specialist Natalie Tsay said the company “considers data points such as expenses per student or student-teacher ratio alongside parent/student surveys” to determine the Clubs & Activities grade.

Regardless of Niche's ranking, we continue to attract far more applicants than we have spots.

COURTNEY BURGERCourtney Burger, SJS Director of Admissions, said that her team does not put stock in school ranking websites because of a “lack of transparency in how those rankings are established.”

“Keep in mind, one revenue stream for Niche is to charge a fee to the schools in return for promotional placement,” Burger said. “For many schools, Niche is an important marketing tool to increase the

number of applicants.”

Burger said that St. John’s uses its budget to support its students and teachers rather than to inate its ranking.

Niche partners with schools “to help them achieve their enrollment goals” because it acts as a bridge between schools and students and, according to Tsay, “a school being a partner has no e ect whatsoever on that school’s grades or rankings. We remain committed to evaluating all schools consistently.”

St. John’s has fewer user reviews than many similar area private schools, so any unfavorable review has a larger impact on its ranking. SJS had 106 user reviews compared to Awty (172) and St. Agnes (313). Additionally, many reviews are outdated. One negative review from 2015 blamed the school for their son’s substance abuse problem and eventual decision to drop out of college.

Reviews are, according to Niche, “in some cases, a small part” of their methodology, but they rely mostly on data points, Tsay said, citing their primary source as the U.S. Department of Education.

“Because user reviews have always been an integral part of our platform, we stand by our decision to factor those voices into our rankings,” Tsay wrote in an email with the Review. “It's the main di erence that sets Niche rankings apart.”

Niche stands alone as the only one of the major ranking sites, which includes the Houston Chronicle and Houstonia magazine, that does not place St. John’s at the top of the private schools in the Houston area.

Niche allows anonymous reviews so users feel comfortable speaking truthfully about their experiences, and it claims to moderate reviews to ensure accuracy.

“Quality control is a constantly evolving process at Niche,” Tsay said. “We employ a number of quality control measures when incorporating self-reported user data and user reviews, including automated scripts that account for anomalies and suspicious activity,” she said.

Although the drop in Niche ranking sparked some student discussion, the number of ninth-grade applicants increased over the last ve years.

“Regardless of Niche’s ranking,” Burger said, “We continue to attract far more ap-

plicants than we have spots.”

While local K-12 rankings are rather niche, college rankings are Big Business. Since 1984, US News and World Report has made a name for itself with their annual Best Colleges list. Its methodology factors not just data but also prestige, creating potentially awed — and controversial — rankings.

On Nov. 17, both Yale and Harvard law schools withdrew from US News and World Report rankings. The next day, they were joined by Stanford, Georgetown, Columbia and UC Berkeley law schools, which all cited questionable ethics and methodology.

According to The Washington Post, rankings favor schools with money and notable reputations — a full 20% of a school’s ranking is determined by its reputation among college presidents.

The rankings create a vicious cycle in which employers hire graduates from top schools, increasing the school’s reputation and ranking. It also tacitly rewards schools that in ate their data.

In March, Columbia University was caught falsifying data submitted to USN&WR. Many critics saw this as proof that the rankings system was broken.

“Most colleges do actually report truthful-

From Oct. 10–13, members of The Review attended the National Scholastic Press Association’s Fall Convention, held this year in St. Louis. Fourteen Review editors and Drew Adams, a Quadrangle editor-in-chief, promenaded through the city, ate copious amounts of Thai food and took top prize for one of the most prestigious awards at the culminating awards ceremony.

The October issue of The Review won rst place Best of Show, marking the third straight year and fourth time ever The Review has won. The golden Best of Show trophy (for schools with less than 1,800 students) is awarded to the best publications entered at the convention.

“We were at this terribly long awards ceremony with these amazing schools,” sub-editor Lily Feather said. As each of the Top 10 publications were listed on the big screen, editors were relieved that they did not place low — but they also knew that their chance of victory diminished with each school announced.

When “First place: The Review” graced the wall-sized screen at the front of the hall, Feather wasn’t even watching, “but all of a sudden everyone was jumping up and down and screaming like crazy.”

The Review Online followed with a Top 10 nish in the Best of Show small-school website category, an increas-

ingly impressive feat as more high school publications expand their online presence.

Online section editor Serina Yan won rst place for Editorial Cartoon of the Year for an illustration that featured a Supreme Court justice with a Texas-shaped face declaring, “Your body, my choice." The cartoon was published in the rst semester of her freshman year.

Multimedia Editor James Li earned three awards: Broadcast Journalist of the Year (honorable mention), broadcast feature with Annie Villa (5th place) and broadcast feature with Section Editor Richard Liang, Photo Editor Lexi Guo and Drew Adams (honorable mention).

Print editor-in-chief Wilson Bailey and former executive editor Ella Chen won a 3rd place Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Award for their article on Hurricane Ida.

Print editor-in-chief Diane Guo won an honorable mention for Designer of the Year, and Online Section Editor Lucy Walker, who has drawn, designed, written and photographed for The Review, received an honorable mention for Multimedia Journalist of the Year.

The rst piece that copy editor Lauren Baker ever wrote, “Help a cancer patient: Get vaccinated,” won an honorable mention for Opinion of the Year.

ly, to help with the rankings,” said Shawn Miller, an SJS college counselor. “The issue is the rankings are generated and created through di erent means. Niche is a great example: there is a lot of user interaction that can generate ratings that might not be totally truthful.”

A disproportionately high ranking could scare a potential applicant away from a college that would best t them, but a ranking that is too low could ward o prestige-conscious students.

When students generate a potential list of colleges where they might apply, they often begin with Top 10 rankings, forgetting to take into account whether they would actually be happy there.

Niche and other ranking sites can be useful tools for families to make informed decisions, but Miller said that students should not use them to curate nal application lists or become obsessed with name-brand colleges.

“Rankings are usually generated in ways that aren't positive for building a college list,” Miller said. “It can cause more harm than good.”

Anna Fisher did not wait to start a family until after her space career.

She joined NASA in 1978, had her rst daughter, Kristin ('01), in 1983, and ew on the Space Shuttle Discovery in 1984, becoming the rst mother in space.

When Fisher was 12, the rst manned space ight was set to launch on May 5, 1961. She and her classmates gathered around a small radio as Alan Shepard spoke to Mission Control in Houston. Listening to the broadcast in the school gym, “a seed was planted,” and no matter how unrealistic it was for a woman at that time, Fisher was determined to become an astronaut.

“My whole story was centered around serendipitous events,” Fisher said.

She started a career in emergency medicine in the mid1970s. One day, Fisher had lunch with a colleague and found out by chance that NASA was looking for astronauts. After her application, a series of interviews and physical tness tests, she became one of the rst six women selected for the U.S. space program.

Fisher compared her NASA experience to a surfer catching a wave at just the right moment “when societal norms were starting to change.”

In the '70s, NASA nally committed to diversifying their Astronaut Corps, and its women gained more visibility.

“It was hard because you wanted to make sure you did a good job for the sake of the women that came after you,” Fisher said.

“Because things don’t always go as smoothly as you would like them to,” Fisher advises young people to “believe in themselves.”

These days, Fisher speaks at Space Center Houston and the Kennedy Space Center several times a year. She encourages travelers to explore the world like the godmother of the Viking ocean ship, Orion. The State Department also invites her to inspire young women around the world to pursue STEM careers.

Fisher’s groundbreaking work in space travel paved the way for future female astronauts.

“Being the rst mom to go to space, there were so many people who thought it was wrong for me to go on this risky journey,” she said. “For women, you can have a demanding career and you can have a family — you shouldn’t have to choose.”

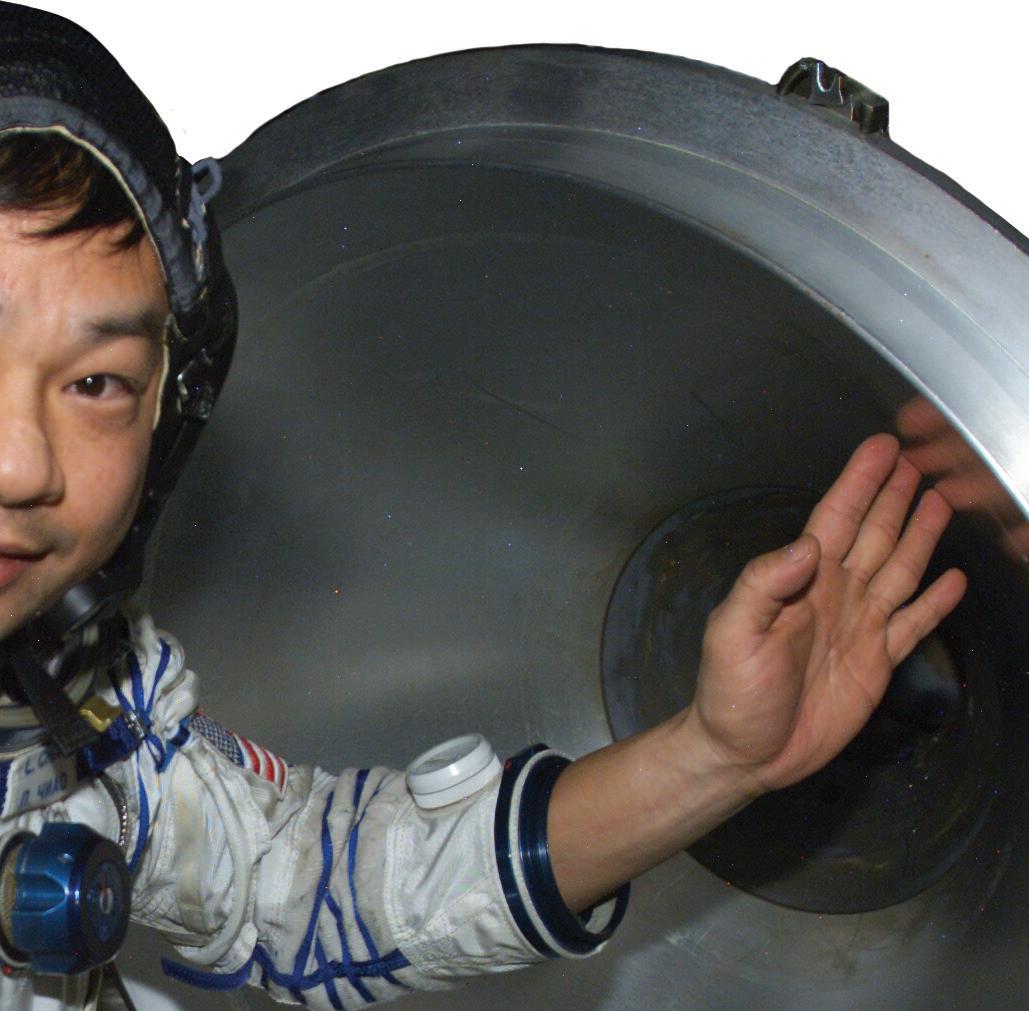

When twin sophomores Henry and Caroline Chiao were still in strollers, their parents rolled them up to NASA Mission Control Center in Clear Lake, where they met many of their father’s astronaut friends and colleagues.

At 8 years old, Henry and Caroline were introduced to their father’s friend Alexei Leonov at a Rice University function. The late Leonov was the rst to conduct a spacewalk.

A former NASA astronaut and International Space Station Commander, Leroy Chiao traveled into space four times over the course of his 15-year career, logging 229 days in space. When his twins were ve, the family traveled to Florida to see one of the last space shuttle launches before the program was retired in 2011.

ANNA FISHER

Fisher served as a ight engineer and robotics arm operator during her rst mission on the Space Shuttle Discovery. As a mission specialist, Fisher also assisted in the deployment of two communication satellites and the retrieval of two other multi-million dollar satellites that had fallen into the wrong orbit, rendering them useless. According to Fisher, “No one had ever done anything like that before.”

Six weeks before her second scheduled space ight, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after lifto on Jan. 28, 1986. Knowing it would be years before Fisher could return to space, she took a leave of absence that lasted until 1996.

During her time away from NASA, she had a second daughter, Kara ('07), in 1989.

Fisher got involved with St. John’s by chaperoning her daughters’ eld trips, attending football games, participating in Senior Tea and speaking to students about space.

“It felt like such a family environment,” she said.

After returning to NASA, she assumed command of the Space Station branch. By then, international relations between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union had improved, leading to the Shuttle-Mir Program, a collaboration between the two countries. Fisher volunteered to stay on the job so that she could build relationships with the Russian team before making her second space ight.

“I wasn’t in the space program just for myself and going into space,” Fisher said. “I believe strongly in space travel, and I was happy to be able to make a contribution.”

After working to help establish the International Space Station, which became fully operational in 2009, Fisher was eager to visit. But when the Space Shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon re-entry on Feb. 1, 2003, her return to space was delayed yet again.

In 1969, Chiao was 8 years old, and Apollo 11 became the rst manned space ight to land on the moon. “That’s when the dream started for me,” he said. “It was always in the back of my mind — I was going to at least try to become an astronaut.”

From ying T-38 jets to learning vehicle operation in simulators and attending classes, astronauts are always training. Chiao’s NASA career started in 1990, with his rst space ight in 1994. He began with a research mission in which he spent two weeks in a laboratory module. While he was expected to keep t, his preparation also included emergency procedures and mission-speci c training, such as robotic arm operations, spacewalks and experiments.

Chiao brought several NASA-approved items with him on his space expeditions, including a wristwatch, mechanical pencil and family photos — mementos he still keeps today.

He performed two spacewalks on his second mission in 1996, which tested and evaluated tools and construction techniques. The ndings were later used to install two major pieces of the ISS on his third mission in 2000.

On his fourth and nal mission in 2005, Chiao copiloted the Russian spacecraft Soyuz TMA-5 to the ISS. He served as Space Station commander for over six months, conducting research and overseeing maintenance.

Having trained with cosmonauts, Chiao performed two Russian spacewalks in Russian-made spacesuits, and when the mission was completed, he landed in Kazakhstan.

Chiao says that “being up there and looking at the Earth” is a surreal experience.

As one might expect, not everything goes exactly to plan on a space mission. On his nal voyage, the spacecraft was approaching the ISS when alarms began blaring because the autopilot had failed. After almost losing sight of the station, the astronauts brought the spacecraft to a stop just 50 meters from the ISS and docked their craft manually.

“We were well trained for that kind of an emergency,” Chiao said. “Training prepares you to deal, as best as possible, with anything that can go wrong.”

After his last mission, Chiao spoke in 2005 at a school assembly about his experiences in space.

Today he serves as co-founder and CEO of OneOrbit, a company that promotes corporate leadership and sponsors student events.

Last November, he spoke with the Space Technology, Economics and Policy club. “Everyone was really eager to hear about his life," STEP Club leader Sebastian Vlahos said. “His stories were so interesting."

Chiao made the decision to leave NASA at the end of 2005: “I had done everything I could do in a ying career,” he said. “It was a natural time to leave NASA — leaving on a high note.

Leroy Chiao, SJS parent and former International Space Station commander, has been to space four times.As she awaited her next mission, Fisher helped improve the display panels for the Orion Space Shuttle.

Fisher retired from NASA in 2017; she never returned to space.

Not only was Fisher the rst mother in space, her then-husband Bill went into space a year later, becoming one of a handful of married couples to do so.

After graduating from St. John’s, Kristin worked as a White House correspondent for Fox News and currently works as a senior space and defense correspondent for CNN. Her sister Kara earned an MBA at Southern Methodist University and works in the private nancial sector.

While in the space program, Fisher faced scrutiny from the press. At the start of her journey, Fisher said that she had “zero con dence.”

Anna Fisher, the first mother in space, took her NASA photo with her daughter Kristin ('01).Irene Vázquez has weathered storms her entire life. Growing up in New Orleans, she was used to “ ood days” cancelling school and fallen oak trees littering streets.

But Hurricane Katrina changed everything.

When the Category 5 storm hurtled toward Louisiana in 2005, her family followed the usual plan of attack: riding it out with her grandmother in Alabama.

This time they didn’t return back home, relocating to Houston months later.

Vázquez, now 24, still feels a strong connection to New Orleans.

By Lillian Poag

By Lillian Poag

After Ariana Lee's recitation of “Falling," one of the audience members was brought to tears.

The poem was inspired by the 442nd Infantry Regiment, a U.S. Military unit consisting of Japanese American soldiers during World War II. The audience member was the descendant of a soldier in the 442nd.

“I read that they were the most decorated military unit of all U.S. history,” Lee said. “So how come we never learn about them?”

Lee was inspired by a time when the regiment climbed a cli to launch an attack on German forces, and many of the soldiers fell o the edge. As they plummeted to their deaths, the soldiers remained silent because they did not want to give away their position. Lee thought this act was so powerful that she used the falling as inspiration for the choreography in her performance.

On Nov. 3, Lee was named the seventh Houston Youth Poet Laureate at a ceremony held in her honor. After the 2022 laureate, Avalon Hogans, passed down the prestigious golden pen and journal, Lee gave her acceptance speech and performed ve poems.

Lee hopes to one day become United States Poet Laureate.

Through her poetry, Lee explores what it means to be Asian American and the child of immigrants. Many of Lee’s poems focus on uplifting stories that are often overlooked.

Slam poetry originated in Chicago in the ’80s when poet Marc Kelly Smith, who believed that poetry had become “too structured and stu y," hosted his rst competition. Today, spoken-word poetry is de ned by its emotional delivery and powerful writing.

Paraphrasing one of her favorite poets, Sarah Kay, Lee explained that spoken word “is best described as poetry that can’t stay on the page. Something about it demands to be spoken aloud.”

Lee is a member of Meta-Four Houston, a youth poetry slam team coached by renowned performer Blacqwild owr and Outspoken Bean, the current City of Houston Poet Laureate. Over the summer, the team won the Skylawn slam at POST Houston.

“Katrina is just a very large part of who I am, and how I make sense of the world,” she said. “It is something that I’m always coming back to, whether I know it consciously or not.”

These days, Vázquez (’17) lives with another St. John’s alum and a tortoiseshell cat named Gemini in New Jersey. She works as a publicist and assistant editor for Levine Querido, an independent publisher. She also freelances as a journalist and poet. Her articles have appeared in the Texas Observer, Houston Chronicle and Pulitzer Center, and her poetry has been featured in Brooklyn Poets, Muzzle Magazine and the Hennepin Review.

She returns to her experience during Katrina in her debut poetry chapbook, “Take Me to the Water,” published in October by Bloof Books. Since then, she has been “hodgepodging together a tour” across America.

“A common narrative that happens after hurricanes — especially destructive ones like Katrina and Harvey — is, why should we rebuild these places? What’s worth going back to?” Vázquez said. “I write to answer that question and show how much beauty and life is there.”

Vázquez, a Johnnycake alumna, is a performer at heart, so spoken word was “this perfect medium, where I could marry this beautiful writing and performance,” she said.

In the Upper School and at open mics across the city, Vázquez shared her spoken-word poetry. During her time at Yale, she was accepted into the selective WORD poetry group.

English Department Chair Rachel Weissenstein, who taught Vázquez sophomore English and Creative Writing, remembers her spoken-word performances during class.

“When she performed original spoken word poems, it was apparent that this is what she was meant to do,” Weissenstein said. “She seemed to feel that, and the people who saw her perform felt that as well.”

Even as a teen, Vázquez had a lot to say. She saw herself as a hurricane, a force of nature, “large and monstrous and destructive” because of all the feelings churning within her. Through poetry and journalism, she found a way to channel them.

Vázquez joined The Review as a freshman and became editor-in-chief her senior year. Review adviser David Nathan dubbed her “the editorial voice of the paper” for her ery opinion pieces, including “An open letter to Donald Trump” and “How can meager millennials manage?”

“She was about getting heard — love me or hate me, but do not ignore me,” Nathan said. “And you couldn’t ignore her. It was impossible to ignore Irene.”

I feel the best in my body when I’m dancing, and spoken word gives me that same feeling. I feel the best when I’m creating.

Since she began publicly reciting her work a year ago, she has performed original pieces in city-wide grand slams and symposia.

“I started writing poetry because it touched me,” Lee said. “And now I can touch others, too.”

A few months into quarantine, Lee came across a slam poetry video by the Los Angeles Youth Slam Poetry Team. Without even realizing, she spent hours bingewatching the content, becoming more inspired to explore her identity through spoken-word poetry.

Lee is no stranger to the stage. She began dancing at four and performed with the Houston Ballet for ten years in front of hundreds of people.

“I feel the best in my body when I’m dancing, and spoken word gives me that same feeling,” Lee said. “I feel the best when I’m creating.”

Lee uses her experience in dance to choreograph some of her poetry performances herself.

ARIANA LEEOnly two years after discovering slam poetry on YouTube, Lee now runs her own channel, where she posted her Independent Study Project, a dance lm of “My Boy” by Billie Eillish. She performed, directed, choreographed and edited the lm. Lee also uses Instagram (@ari. purplecrayon) to update her followers about public appearances. The account includes a link to her performance of “Through the Eye,” a poem written about Lee’s experience during Hurricane Harvey, which caught the eye of One Breath Partnership, an environmental non-pro t organization.

“Something that I learned from the slam community is that you speak from your lived experiences,” Lee said. “I've learned a lot about myself and other people through just getting involved in this community, so I hope people can use others' experiences to re ect on their own.”

Lee’s goals for her career include becoming the rst Asian American National Poet Laureate, as well as bringing poetry into the mainstream.

“I want people to know that spoken word is super, super diverse,” Lee said. “It's a very vibrant community, and it's not the rigid, structured, traditional poetry that is often taught in school."

Vázquez, who is Black Mexican American, features Black, Latino and Indigenous perspectives in her poetry. She says the poem that best sums up the terrain traversed in the book is “The Black Shoals,” a narrative piece about colonialism and natural disasters. It was the rst poem Vázquez wrote for the collection.

Writing “Take Me to the Water” was a yearslong endeavor: she began composing the poems as a student at Yale. Her writing process involved months of editing, countless workshops and a Spotify playlist curated for inspiration. Vázquez usually began writing before dawn, fueled by French press co ee and buoyed by pictures taped to the wall above her desk.

“I got to really appreciate writing in the morning because very few of my friends were awake. There's no distractions. There’s nobody else’s thoughts in your head,” she said. “I feel like the world can be very loud sometimes.”

Because of her day job, Vázquez was able to plan the chapbook’s launch herself. The book cover was printed and its pages handbound by Bloof Books, which has already started a second printing.

Vázquez has quickly gained prominence among young poets and won a plethora of awards, including Brooklyn Poets Fellow, Best of Net nomination and, just last week, a second nomination for the Pushcart Prize. She received her rst nomination in high school.

Vázquez began writing poetry in seventh grade at St. John’s. Her self-proclaimed “emo” phase coincided with her time as an editor for the Middle School literary magazine, The Diamond Window. Poetry soon became a way to express all of her “very big feelings.”

During her freshman year, a classmate introduced her to spoken-word poetry.

Vázquez said her current journalistic work explores Black and Indigenous experiences of colonization and environmental racism. One of her pieces, which she wrote with support from the Pulitzer Center, sent her back to Louisiana to report on the Sacred Waters Pilgrimage, a journey along the Mississippi River designed to heal Black and Indigenous participants’ “relationship with water.”

“She’s perceptive and hilarious, but she’s not frivolous. She’s trying to change the world,” Nathan said. “She’s trying to get people to notice what’s wrong in the world, and she does it in a way that makes you want to listen.”

Senior Ariana Lee performs spoken-word poetry at the Climate Justice Museum & Cultural Center.

By Elizabeth Hu & Katharine Yao

By Elizabeth Hu & Katharine Yao

Brick by brick, senior George Donnelly’s replica of the Daily Bugle began to take shape. Measuring almost three feet tall, the 3,772-piece skyscraper took more than eight hours to complete.

The Daily Bugle — the ctional workplace of photographer Peter Parker, AKA Spider-Man — was a surprise birthday gift from his aunt and is now one of many builds displayed in Donnelly’s personal Lego Hall of Fame: the shelves in his bedroom.

As co-founder of the Lego Club, Donnelly has also built the McCallister house from “Home Alone,” multiple Star Wars sets and various structures of his own design.

“With Legos, there are no limits, no rules to what you can do,” Donnelly said. “You can just bring in all types of stu and really do whatever you want.”

Although following a step-by-step guide results in easier, more straightforward building, Donnelly prefers to create his own unique designs, changing his vision to accommodate the constraints of having a limited array of pieces.

“Usually it comes out looking pretty ugly,” Donnelly said. “So I have to change it a couple of times and evolve the idea.”

Danish carpenter and Lego founder Ole Kirk Kristiansen started making wooden blocks and toys for children in 1932. Four years later, he o cially started the company, deriving its name from the Danish words “leg godt,” meaning “play well,” which is synonymous with both its name and mission. Ninety years later, that goal still holds true.

Upper School Neuroscience and Anatomy teacher Paula Angus is the faculty sponsor of the Lego Club. Even as an adult, Legos still have an important place in her life. A longtime tradition in her family involves building sets with her daughters during Christmastime.

“Legos do a good job of bridging the gap between adults and kids,” Angus said. “It gives adults a chance to be kids again.”

As people grow older, those who stick with Legos sometimes move away from free-building, which is a process of assembling, dissembling and rebuilding creations over and over. Eventually, prefabricated sets hold more appeal — the fun is still there, just with a little more structure.

“It's the building process that di erentiates Legos from other types of toys or model-making,” Donnelly said. “Even if you don't take something apart and rebuild it, just slowly assembling it and seeing the di erent techniques to build something is where the value comes from.”

Free-building takes signi cantly longer than building from a pre-made set; Donnelly has spent less time creating Lego structures since entering high school — a sentiment common among other Upper School students who played with Legos as kids.

been playing with Legos since she was ve. In just a few years, she was building sets meant for ages 14 and up.

“People would assume that I wouldn't be able to do something so complicated because I was so little,” Walker said. “And then I would whip out this awesome spaceship and be like, joke’s on you.”

Walker has been underestimated not only for her age, but also her gender. Lego is the rare activity that is perceived as gender-neutral and inclusive. But with the advent of ridiculously easy, obviously female-oriented sets such as Lego Friends, it’s hard not to see a gender divide taking shape.

“Why are you going to assume that I want something that's branded to be feminine?” Walker asked.

Walker recounts a Toys “R" Us trip where she gravitated towards a Lego Chima set, complete with zombie ravens and ice hunters, yet her mom suggested a Lego Friends set with a baby seal.

“My mom was like, but look, it's so cute,” Walker said. “And I was like, but zombie ravens, that's so awesome!”

AJAY CLARK-DESAIJunior Ajay Clark-Desai is currently working with his younger sister on a 2,316-piece Lego model of Vincent Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” Clark-Desai said that piecing together the famous painting helped him understand Van Gogh’s process: “I’m starting to realize exactly how the pieces coincide with the art itself.”

Playing with Legos has also inspired Clark-Desai to pursue other interests. In particular, Lego Mindstorms, a line of robots that can be programmed to dance and play sports, kickstarted his interest in coding.

“Not to make a pun or anything, but my love for Legos just kept building upon itself,” Clark-Desai said.

Clark-Desai continued experimenting with Legos via building techniques like sliding doors and revolving cannons. His interest in Lego Robotics eventually turned into a love for engineering, robotics, and STEM courses, and while they were originally meant as a children’s toy, they have also created a lot of interest and opportunities.

You would be hard-pressed to nd anyone at St. John’s who has ever had an interest in engineering or STEM who didn't play with Legos as a kid.

For Lucy Walker, an online editor, Lego Technic was a way to bond with those who loved to make things.

“I could call my friend and tell them to hand me a 12-stud beam and two 6-stud axels, and they knew right away what I needed,” Walker said.

“It was a couple of mad scientists working on this project they were just super psyched about.”

Walker had

As popular as Lego is today, it’s easy to forget that the company almost went bankrupt in the early 2000s. A decision to shift more towards digital entertainment instead of their trademark colorful blocks led to disappointing sales. Thankfully, fan devotion towards the iconic toy company kept them from going under. Legos have remained an enduring staple of American childhood ever since.

“There's just something about Lego that has cemented it in the childhood memories of several generations,” Walker said. “They’re instantly recognizable and really satisfying to snap together.”

After all, what other childhood toy could have people outside their stores lined up for blocks?

Not to make a pun or anything, but my love for Legos just kept building upon itself.George Donnelly's replica of the Daily Bugle. Piece count: 3,772 PHOTO | Alexander Donnelly At his regular Lego Club meetings, senior George Donnelly designs custom Lego builds. PHOTO | Isabella Diaz-Mira Lucy Walker spent 15 hours building a model of Hogwarts Castle Piece count: 6,020 PHOTO | Lucy Walker

By Lydia Gafford

By Lydia Gafford

harness for the climax of Act I.

Gray portrayed Mr. Hart, a sexist boss kidnapped and held hostage in his own garage by three of his female employees. The scene was supposed to end with the automatic garage door opening and lifting Watson above the stage.

One night it didn’t go as planned.

“During the transition,” Tanner said, “we couldn’t get the harness on in time.” Mild panic ensued.

boss desperately

Behind the scenes, the cast and crew desperately tried to communicate that they could not do the stunt because it was not safe, even though it meant that a significant plot point was omitted. Fortunately, they called off the lift before some greater calamity could befall the production.

Backstage mistakes can cause panic, while others deflate the morale of cast and crew.

For Thomas Murphy, technical theater combines feats of engineering with art and drama. He teaches young thespians how to operate saws, screw guns, soundboards and spotlights, among the many other gadgets that help create a show.

Murphy, Johnnycake’s Technical Director, hosts Saturday crew in the Lowe Theater every week, in which students build the sets for every Middle and Upper School production. Junior Maggie Whelan, Johnnycake Vice President, loves crew because it makes her feel accomplished and involved with the production.

s soon as the cast of “Clue” took their final bows, the actors skittered off the stage in all directions. Ava Steely, who played Miss Scarlet, slammed a door shut behind her — and the wall came crashing down.

“I stood there like a deer in the headlights,” Steely said, “completely shocked.”

“Clue” was one of the most logistically difficult shows the theater department has attempted recently, with nine backstage crew members managing five moving platforms and sliding walls. The technical aspect was nearly as chaotic as the frantic action on stage.

Shaan Patel, a senior backstage technician, considered this production the most complicated and challenging he’s ever done.

“Pretty much the entire set was moving,” Patel said, “Things had to fly on stage, roll off — it was just a lot.”

Before the curtain call calamity, there were more minor technical difficulties. Unbeknownst to the audience, the set was damaged little by little during transitions. Armed with a hammer and nails, Patel strategically repaired the set without the audience knowing.

“I waited for bits of laughter, or loud dialogue, or lots of screaming — wherever I could to mask the hammering,” Patel said.

A troublesome sliding wall was yet another headache for the backstage crew.

“I tried to close it,” Steely said, “and that was just the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

In the Oscar-winning film “Shakespeare in Love,” producer Philip Henslowe remarks on the state of the theater: “The natural condition is one of insurmountable obstacles on the road to imminent disaster,” he says. “Strangely enough, it all turns out well.”

The mishaps of “Clue” are but the latest addition to a long and comical history of Johnnycake productions. Although Steely said she felt terrible about literally bringing down the house, “it was better than the Zipline Incident.”

In the 2019 production of “The Three Musketeers,” the hero D'Artagnan, played by Tanner Watson (’22), was supposed to swing over the stage from one VST balcony to another via zipline, strapped into a harness.

On the final night, D’Artagnan was prepared to swoop in and save the day, but just as he reached the balcony, Watson’s foot slipped, causing him to slowly roll backwards until he was stuck high above the audience, unable to move.

“I hung there like a ragdoll," said Watson, a former Johnnycake President.

Without stopping the show, his fellow castmates rescued him and pulled him to the other side with a rope until Watson reached the balcony, and the dramatic fight scene resumed.

Some people in the audience tried to comfort Watson by telling him the incident appeared purposeful, but Watson says it was very obviously a mistake.

Today, Johnnycake refers to the Incident as simply “Zipline.”

In the spring musical production of “9 to 5,” Tanner worked backstage crew and was tasked with helping his older brother Gray Watson (‘19) into a

“Oh God, it's morbid,” Tanner said. “When you make a mistake, it’s dead silent because nobody knows what to say. Should I say sorry? Should I console you?”

Performing in front of a live audience limits communication backstage. Patel says that because the stage is so large and dark, messages often get confused, likening it to a game of telephone.

Regardless of mistakes on stage, audiences tend to be sympathetic.

“It’s live theater; there’s always a chance of people making mistakes or something being off,” Steely said, “It’s part of the experience and part of the risk you take with theater, and that’s what makes it so exciting. The audience is part of the experience, so when they come, they understand that aspect of it.”

deflate the morale of cast and crew. Tanner limits often whatever

In “Clue,” the directors complimented the crew’s ability to stay calm and deal with whatever issues arose.

“Puffs” was especially challenging since it was the first live performance during the pandemic. The 2021 production relocated from the Black Box to an outdoor stage before ultimately being performed in the Lowe Theater for a low-capacity audience.

To further complicate matters, there was no backstage crew due to Covid safety measures. All the actors were responsible for their own props and made costume changes without any assistance.

“That show was a madhouse,” Steely said, “People could tell that it was difficult. But there was no way they could have known the absolute chaos that was going on backstage.”

Nearly every actor portrayed multiple roles and had several costume changes. At one point, Owen Paschke (‘22), who played both Cederic Diggory and Lord Voldemort, also served as a temporary backstage tech to operate the fly rail, which raises and lowers objects on stage.

While a smooth performance would make life much easier for everyone, Steely embraces the impact that chaos has on Johnnycake.

“Something going wrong really can bring you closer together,” Steely said. “It's a funny thing to bond over.”

Those bonds keep casts connected long after the final curtain call. The Zipline Incident is as much a part of Watson’s theatrical legacy as are his leading roles and tenure as Johnnycake president.

“I get to tell that story for the rest of my life,” Watson

St. John’s thespians find that mistakes and occasionally going off-script are part of the appeal of live productions. With so many potential variations happening every night, each performance is truly a unique audience experience.

“I’m a believer that sometimes a script is a suggestion,” Watson said, “Part of theater is that things go off-script — it’s live, and things can go wrong. That’s

beautiful in its own right.”

Whelan started as an Assistant Stage Manager on “Into the Woods” as a freshman. Covid restrictions limited the number of people who could tech the show, so Whelan also worked as a lighting tech. Behind every shine of a spotlight is a tangle of cues, commands and nods.

“They just threw me on lights, lamb to slaughter,” Whelan said. “For the final scene, there was a sequence of six light cues that had to be on certain lines, and I had to get the rhythm down. You just learn as you go.”

For Willy Wonka Jr., the Middle School musical, sophomore Ally Rodriguez worked as a stage manager. Rodriguez said she had an “intimidating” amount of responsibility — she spent weeks coordinating between tweenagers, Upper School crew members and directors, overseeing every aspect of the production.

“It’s easy to get the idea that you have to shoulder everything on your own, but if that’s never the case,” she said. “Johnnycake is a place to be yourself while you're still working as a part of a team. You have this sense of community — we’re all in it together.”

Techs of this year’s fall play, Clue, managed rooms on wheels, a falling chandelier and very finicky microphones. A floor-ridden Mr. Green found himself face-to-face with the chandelier as fly rail tech Katherine Pearson lowered it to the ground. The klutzy FBI operative, played by senior Jack Aitkens, rolled out of the way just in time.

“We rehearsed that one a bunch of times,” said Theater Manager and Technical Director Thomas Murphy. “There were specific cues in the lines for Katherine to know when to speed up and slow down. She knew, even if she couldn't see the actor, that he was out of the way.”

But techs have more minutiae to worry about beyond the massive moving parts. Mics alone offer a world of complications: the battery pack has to be strapped onto the actor under their clothes, which proved difficult for Ava Steely, who wore a fitted dress. Techs strapped the mic pack to her thigh and ran the wire connecting to her microphone up her back.

Freshman Raka Agrawal was a backstage tech on Willy Wonka Jr. who coordinated actors, set pieces and machines behind the curtain.

“You are making sure everything works smoothly,” Agrawal said. “What goes on behind the scenes is a lot of setting up and organizing.”

In the week before opening night, tech week, the cast and crew stay after school every day to rehearse, troubleshoot and fix. It’s “frantic,” Agrawal said, but the late nights and chaos bring the crew closer together.

“Everyone is so tired and kind of unhinged in a great way, so it's a very fun community to come into. You are all a team,” she said. “Every person counts.”

Sophomore Vivian Kwoh has been attending Renfest since she was a tiny 3-year-old in a fairy costume. She advised rst-time attendees to “watch the budget.”

To prepare for this year’s outing, Kwoh spent hours working on a detailed estimate, complete with a slideshow, for her four friends and her parents. She tried to break down the cost of every activity, but became frustrated with the Renfest website, which did not list the exact price of activities — a tactic Kwoh says will make guests believe they are inexpensive.

“I gave the barest of bones estimation,” Kwoh said, “and we spent double that.”

The group budgeted almost $400 on activities with an additional $60 for food. Their favorite activity — throwing tomatoes at a man who stands onstage and insults festival-goers — costed $40. The budget did not account for anything sold in stores.

This year, Kwoh decided to allocate a sizable chunk of her own money on a professional photo of herself and her friends in costume. She keeps a small copy of the picture in her wallet: “They’re worth it because you get to preserve the memories.”

According to Wan, Renfest’s main demographics are D&D players, nerdy teenagers and middle-aged dads. She says that with the in ux of younger attendees, Renfest “will have to cater to a new audience.”

Still, Wan considers Renfest a “cult classic” that is here to stay, thanks in part to a growing interest in fantasy, including in “LARPing” or Live-Action Role Playing.

Wan plans to keep attending Renfest. She says the festival is “a novelty” because it gives Texans a limited window to attend.

“It ful lls a niche I’m interested in that I don’t get to engage with a lot,” Wan said.

By Lily Featherhen over a dozen D&D Club members descended on the Texas Renaissance Festival

last fall, the outing quickly became a corset-buying quest. Fueled by oversized turkey legs, they wandered about the tiny town of Todd Mission, admiring centuries-old fashion.

After one adventurer bought a black, embellished, faux-leather number, the rest followed suit, making their ye-olde purchases in a fantasy shopping spree.

The festival-goers returned this year on Nov. 26, renewing their annual quest to throw knives, buy cloaks and hunt for iced co ee.

The Dungeons and Dragons Club members are among fans who consider any Renfest outing incomplete without costumes, both homespun and store-bought.

D&D club member Thomas Center, who has attended almost every year since middle school, makes costumes by hand whenever possible. This year, Center’s pirate out t included a corset, a tricorn hat and a belt that held two knives, a telescope and an empty potion bottle.

Last year, Center sported an elven look, complete with wood-patterned fabric and a leaf cloak that they glued together themself.

Center completed the look with a two-foot steel sword and scabbard, secured with a leather cord — in compliance with Renfest’s safety rules.

“There’s not really much of a point going to Renfest if you’re not going to do something fancy,” Center said.

This year, senior Adele Wan’s plague doctor costume came together at the last minute. It was complete with a birdlike mask and steampunk-inspired goggles. Last year, Wan hand-sewed her costume: an all-black leather-and-lace oor-length dress with sheer pu y sleeves and metal embellishments.

“It’s mostly an excuse to dress up,” said

Wan, who also makes her own Halloween costumes. “I’m always going to use this as an excuse to create.”

Out ts factor into festival-goer expenses, along with merchandise, food and tickets ($15 for kids 12 and under, $30 for adults). Depending on one’s frugality, or lack thereof, a trip to Renfest could cost thousands.

The D&D Club realized that going as a group earned them a slight discount — a windfall that lessened concerns about cost.

“I don’t want to be spending quite as much as I am,” Center said. “But if I’m going to, at least I’m spending it somewhere that I care about and giving money to very talented individuals, not just a random corporation.”

The Texas Renaissance Festival began in 1974 on an old strip-mining site 50 miles northwest of Houston. It now claims to be the nation’s largest Renaissance theme park. Its founder, George Coulam, bought the land and formed Todd Mission, his own municipality (population 123, according to the 2020 census).

Over half a million people regularly attend Renfest during its nine weekends. Each week has its own theme, such as All Hallows’ Eve and Pirate Adventure. Attractions include a jousting performance in a Colosseum-style arena, high tea and four escape rooms.

Part of the appeal is its support for small businesses and handcrafted items.

“People get the cheap baubles from wherever in our globalized network of cheap things that you can get from any supplier," said history teacher Joe Wallace, “but then there are people that make things, and they’ve done so generation after generation.” Wallace attended the festival in 2021 with his family.

Wan expressed trepidation about the future of small businesses at Renfest. When she returned to the festival post-pandemic, she noticed that some businesses were reselling fast fashion pieces, only slightly nicer than the quality found at large costume stores like Party City.

For Wan, Renfest is now an expensive endeavor that hawks overpriced items. Some

D&D club members spent upwards of $100 each on corsets alone.

“I don’t want to break the bubble, but all of those corsets could have been found on Amazon,” said Wan, who actually found hers on Amazon for a much lower price.

Wan would prefer the festival follow the Nutcracker Market model by hosting unique vendors from the Houston area.

“There are a lot of small businesses that could assuredly bene t from the publicity that Renfest has,” she said.

Renfest boasts 400 on-site shops in its many districts, yet Wan noticed a sameness to those shops across the districts.

“I de nitely see that there’s a need to ll space,” she said. “Each of the districts is very much the same thing, but with vaguely di erent cultural aspects pushed into it.”

Center also anticipates Renfest’s growth. “As things like D&D become more mainstream, it’s going to draw more people into engaging with fantasy,” they said.

For Center, the event embodies fantasy worlds they have always dreamed of.

“I was very much one of those kids that thought I would get an acceptance letter to Hogwarts,” Center said. “So getting to have a space where all these fantasy things come to life is really great.”

Center’s favorite part of Renfest is the look of wonder on friends’ faces when they arrive in Todd Mission for the rst time and see adults as well as small children running around with swords.

“There’s so much freedom to be who you want to be without worrying how you’re going to be perceived.”

Additional reporting by Lydia Gafford

Additional reporting by Lydia Gafford

When sophomore Talulah Monthy founded the Fashion Club this year, she had one goal: to create a space where anyone could explore their love of fashion. But the desire to remain ahead of the curve clashes with the increased awareness about the wastefulness of the fast fashion industry.

“All the customers want is something they can wear a couple of times while it’s trendy and then throw away,” Monthy said.

Shein, a major online fast-fashion retailer, boasts over 43 million active shoppers and claims in its mission statement to be environmentally friendly. But to accommodate its rapidly growing customer base, the company adds around 2,000 styles daily to its catalog — a pace that is much too fast to remain environmentally sustainable.

The fast fashion industry began in earnest in the 1990s and has fueled rampant modern consumerism. But avoiding inexpensive, mass-produced clothing in favor of styles that are manufactured ethically and sustainably is an expensive proposition.

Sophomore Aspen Toussaint says companies that prioritize fair labor practices and sustainability are signi cantly more expensive than fast fashion outlets like Old Navy and Target.

“For a lot of people, buying that $10 t-shirt that's trendy right now seems like a great option,” Toussaint said. “The problem is that it's cheap because it's bad quality.”

In a world where two-day shipping is the norm and microtrends pop up weekly, companies have begun competing to locate ever-cheaper sources of fabric and labor. According to the International Labour Organization, such companies tend to employ young children from countries with well-established textile and garment industries. In these regions, child laborers frequently slip under the legal radar.

In 2020, there were approximately 160 million child laborers, with nearly half of them performing work that endangered their health and safety. Up until 2016, the annual rate of child labor had decreased by an average of 1.6%, but progress stagnated from 2016 to 2020 for the rst time in decades. Child labor is especially prevelant in Sub-Saharan Africa, where one out of every four children are exploited

for work.

Because she was born in Cameroon, Edna Ngu, mother of three St. John’s students and one graduate, has always been aware of these practices in her home region, though the child labor there typically relates to agriculture and mining as opposed to the fashion industry.

In 2018, Ngu found an opportunity to take action while volunteering to work at the School’s used uniform sale. Although the majority of the uniforms donated are resold at discounted prices, damaged or outdated uniforms are, for the most part, given to local charities like Goodwill. Uniforms with the school logo are not allowed to be redistributed beyond the school community, so they went in the trash instead.

“I just hated the idea of those uniforms going to waste,” Ngu said. “They were deemed unsellable, but most had tiny rips and

tears or a couple of buttons missing.”

So Ngu converted her garage into a temporary shop and began taking uniforms home to x them up and send them to orphanages in West Africa.

“Being able to support children from the region where I was born is so meaningful to me,” Ngu said. “We have so much, and these kids have so little. It was just natural for us to help in whatever way we could.”

Ngu’s project ful lls her desire to give back to the community while shedding light on the issue of conservation.

“Clothing sustainability is such an important topic,” Ngu said. “Its absence a ects not only those who buy fast fashion, but our entire planet.”

Sophomore Maxwell Gross tries to shop from sustainable brands. To combat the high cost, he buys only a few pieces at a time and wears them over and over.

But that does not mean Gross is unaware of current trends. As an avid fan of high-end couture, he watches fashion show livestreams and particularly enjoys Nadeem Khan and Alfredo Martinez.

In short, he loves fashion — but he “abhors" fast fashion.

“It represents everything I’m against in the fashion industry,” Gross said. “It is hurtful to the environment and perpetuates a short-term vision of fashion, and therefore forces companies to produce cheap and poorly-made clothing.”

Social media ensures that fashion trends are more mercurial than ever, pressuring many aspiring fashionistas to frequently refresh their closets — so they ock to fast fashion.

“As a country, our way of dress and the way that we view clothing has changed so dramatically,” Gross said. “I know people that buy new wardrobes every season, and then they throw away perfectly good clothing.”

Toussaint found a way to stay sustainably fashionable

was by making her own clothing. Sewing gives her the oppurtunity to “have expensive types of clothes for cheap” while combating the deleterious e ects of the fast fashion industry. She also has the freedom to design clothes according to her taste, rather than the trends of the season. While companies like Shein may currently dominate, switching to sustainability is gaining traction. A swath of brands from Gap to Gucci have begun o ering sustainable lines and collections in response to rising demand.

Aspen Toussaint found a way to stay sustainably fashionable by making her own clothing.

PHOTO | Katie Czelusta“I alone am not going to have a great impact,” Toussaint said. “But if a lot of people have that attitude, it does.”

Senior Ethan Tantuco said that, while most people are familiar with the practices of popular online retailers like Shein and AliExpress, they still regularly shop at brick-andmortar stores like Zara, Uniqlo and H&M that use the same inexpensive methods to produce their clothing. Tantuco noted that fast fashion is so cheap and easy that most people overlook its downsides in the name of a good deal.

“There are a lot of everyday stores that people don't realize are fast fashion,” they said. “They think that, just because the clothes are priced a little higher or because they’re not from some no-name brand on the internet, that it's okay. But it’s not. It’s not okay at all.”

Gross did not mince words when asked about the wider impact of fast fashion: “We’re destroying our environment and looking bad doing it.”

By Lucy Walker

By Lucy Walker

Talulah Monthy often spends long nights working. Keeping her motivated — and occasionally exasperated — is her friend, Bertha, with whom she has a “rocky relationship.”

“We clash a lot,” Monthy said.

Bertha is a sewing machine.

Monthy, a sophomore co-founder of SJS Fashion Club, has been designing clothes since she could draw. She received Bertha from her grandmother when she was nine and has used her to make everything from dresses to quick thrift ips.

While producing intricate pieces in late-night sewing fervor, Monthy’s whirlwind approach can make her patterns hard to understand.

“They make sense in my mind,” she said. “But if anyone else [saw] them, they would be like, what is this?”

Monthy employs two blue mannequins named Violet and Indigo (she claims they are distant cousins with “unspoken beef”) as well as a fussy serger, an automatic hemming machine that she considered naming Sergio but decided that it was “too cool” for such an antagonistic device.

Building on her experience making ball gowns according to an established pattern, Monthy plans to create her own ensemble from scratch for Cotillion in January. She is also coordinating exactly what her date will wear. She refused to divulge much about her plans for her dress, but she did dispense one clue: mesh.

Monthy is one of a handful of student seamsters who create their own clothes — at times out of necessity — to challenge their creative limits and express their personal style.

At Johnnycake’s Saturday morning crews, senior Adele Wan usually wears her black “crew pants,” peppered with sheer panels and paint. Wan’s all-black-all-the-time wardrobe embraces the monochromatic style of theater techs outside the VST. As a veteran tech, Wan prizes utility and regularly adds compartments to her clothes for carrying tools. She laments the small size — or

complete lack — of pockets in women’s clothing. Even if she turns to the men’s section, the cut is “large and oversized in an un attering way,” she said. “Apparently, men don’t have hips.”

To achieve her “very speci c aesthetic,” Wan designs and constructs her own clothes, drawing from years of experience altering Halloween costumes. She also tailors and modi es costumes for friends. When she began sewing during the pandemic, she bought most of her materials online. She didn’t mind

Beyond achieving her desired look, Wan sews in order to replace clothing that inevitably goes missing, like a few pairs of cargo pants that vanished in a recent wash cycle.

“They have mysteriously disappeared,” Wan said. “So strange. I was really a fan of those.”

Making a good pair of pants, she said, will take a few hours.

Senior Kacey Chapman has been crocheting since she was young. Much of the allure of crocheting, Chapman said, lies in being able to wear and use something she made herself. Turning a ball of yarn into a fashionable item is both rewarding and sustainable, and she enjoys displaying her pieces and sharing her talents with others.

“I’ve always wanted to do something bigger, something that I could show o ,” Chapman said.

Chapman’s current pride and joy is a huge ower sweater made up of 50 individual “granny squares” crocheted from the inside out in a traditional pattern. Instead of sticking to the classic form, she made each individual square look like a ower. The project took her the better part of last school year.

“It’s very therapeutic, you know? I was pushing a lot during junior year,” Chapman said. “It is just a nice time that I set aside to go and relax and do something creative.”

the occasionally subpar fabrics because they were suitable for a beginner like herself. She now does most of her shopping in person but bemoans the surprising lack of inventory inside the Loop. Michael’s, for instance, has absolutely no fabric selection, and the Joanne’s that used to be across the street is closed.

Wan said there is one decent fabric store, Stitches ‘n Such in Rice Village, “but it opens at 12 and closes at four on weekdays.”

Monthly loves the exibility of crocheting: “If you hate something that you made or something that you bought that happens to be crocheted, you can just take it apart. Then you don’t have to buy new yarn.”

For those who might be inspired to add some air to their closet and begin making their own clothes, Monthy has one crucial piece of advice: Never go on a hemming spree. One of her projects ended in disaster when she had to salvage a botched argyle sweater vest by turning it into a scrunchie, which led strangers to comment, “I didn’t know you could tie your hair up with a sock!”

utility

their

Violet of —

subpar

young. school pushing loves the you making

I’ve always wanted to do something bigger, something that I could show off.

KACEY CHAPMANTalulah Monthy

Even when he only had $20 in his pocket, musical artist Macklemore could famously a ord a velour jumpsuit, gator shoes, leopard mink and zebra-patterned jammies — as long as he bought them at thrift stores.

Back in 2012, Macklemore was on the cusp of a trend that environmentally and socially conscious millennials and Gen-Zers have embraced as an alternative to the fast fashion industry. Thrift stores have minimal environmental impact and do not manufacture new products or outsource labor to developing nations with lax child labor laws.

Thrifting attracts people who want to buy cheap, buy vintage, buy green and buy en masse.

Second-hand clothing stores have existed as early as the 1890s, with thrift stores and charity shops run by organizations like the Salvation Army becoming a mainstay in American culture by the 1920s. But thrift stores have long carried the stigma of poverty and uncleanliness. In recent years, increasing scrutiny of fashion companies has turned thrifting into a near-ubiquitous trend.

Social media platforms are some of the biggest in uences when it comes to fashion — TikTok and Instagram sway people to conform to styles that do not re ect their individuality.

“If people see a person who has 2 million followers thrifting, then they want to do that too,” sophomore Justin Wright said.

While some people have capitalized on the popularity of vintage clothing and thrifting by reselling their old clothing, others exclusively buy from thrift stores to resell online through trendy sites like Depop and Poshmark at marked-up prices.

Adding to the thrifting craze are videos highlighting thrift hauls and ip tips from in uencers and everyday people who show o their skills at sourcing items from the local Goodwill or Family Thrift.

Ethan Tantuco recently found a signed orange University of Texas Earl Campbell jersey at the Goodwill bins on Long Point. At checkout, the cashier asked if they were a reseller because “she recognized the item and its value.”

Last summer, TikTok led Tantuco into a “phase of self-exploration” to discover their own style. With little money to spend, they began thrifting.

“I picked up a bunch of items for cheap, saw what I liked, and my style just evolved from there,” they said.

For thrifters, wallet-friendly, sustainable and ethical second-hand stores or even yard sales are ideal places to buy clothes.

Tantuco said, “Thrifting is a step in the right direction because it is one of those avenues that is nancially accessible for everyone.”

Thrifting also allowed senior Aspen Collins to forge her own style, freeing her from the trends set by retailers like Forever 21. When buying clothes, she asks herself if she is attracted to a particular item because it aligns with her eclectic style, which is “kind of hard to explain,” or because it is trendy.

Sophomore Ryan Paschke began thrifting after her parents told her she would have to spend

“You don’t know what you’re going to get,” Paschke said, “and that’s what’s appealing.”

Despite thrifting’s many bene ts, its rising popularity has led to a spike in prices for what used to be a ordable clothing. This in ation has led some to request that consumers who can a ord pricier yet sustainable and ethical brands like Everlane and Reformation shop at those outlets while leaving the charity shops for those who depend on

“If you’re wealthy enough, I think it’s de nitely a good choice,” sophomore Julia Mickiewicz said. “Usually those people have money owing — why not use it well?”

In big cities like Houston with so many thrift stores and an over-abundance of clothing, people from every socioeconomic level can shop at the same place without concerns about scarcity.

“In the long run, there is so much product that I don’t think getting a haul of clothes that costs

you $50 instead of upwards of $600 at the mall is making as much of a di erence as people think,” Paschke said.

When someone donates an old garment to Goodwill, the store only keeps it on their shelves for three weeks. If it does not sell, it is moved to a Goodwill outlet, also known as the Goodwill bins, where clothing sells by the pound.

So-called boutique thrift stores like Crossroads in Rice Village and Pavement in Montrose have cropped up to cash in on the thrifting craze, drawing a line between those who thrift out of necessity and those who thrift to stay trendy.

While thrifting is increasing in popularity, the fast fashion industry is also booming, capitalizing on the short trend cycles and seasons driven by social media. As a result, clothing from fast fashion brands lled up the racks in resale shops. Because these pieces are, as Mickiewicz said, “made to decay,” their presence in thrift stores further drives the overconsumption of clothing.

In July, the New York Times declared, “the golden age of thrifting is over.” Poorly made clothes mindlessly donated to thrift stores, they claimed, will quickly be tossed in landlls, mitigating any alleged environmental bene ts.

The question now becomes: do the bene ts of thrifting outweigh the costs? For thrifty students, they do.

“I’m glad I found thrifting because it allowed me to nd clothes that t my style at a good value,” Paschke said. “Without thrifting, I probably would have turned to fast fashion.”

By Annie Jones, Jennifer Liu & Mia Hong

By Annie Jones, Jennifer Liu & Mia Hong

Bach Mai’s career as a fashion designer began at St. John’s when he started sewing his friends’ formal dresses. Back in 2017, while he was working for couture house Maison Margiela in Paris, The Review reported on his growing fame — just four years later, he was featured in Vogue after the launch of his own fashion label.

Fresh o the release of his second line, Mai (’07) centers his work around a Texan interpretation of luxury. His father, a Vietnamese immigrant and engineer at an oil renery and chemical plant, is the chief inspiration for Mai’s latest collection. He combined glitzy stilettos and iridescent organza with baggy orange trousers and structured tweed skirts to evoke his father’s humble origins.

“We live, eat and breathe glamour down here,” Mai said at an exclusive reception in Neiman Marcus’ Galleria location to celebrate his nomination as the CFDA Emerging Designer of the Year. “It's not just a fantasy: we have an understanding of glamour that’s innate. It’s an irreverent approach to glamour.”

His father’s blue denim coveralls inspired the color palette of the collection — and the matching hair color Mai sported at the premiere. After he was interviewed by Vogue, Mai predicted that the rst line of the article would mention his turquoise blue hair. It did.

“Manic Panic, if you haven’t tried it,” he said. “Great color.” Mai has always known he wanted to be a designer. His passion for evening wear stretches back to high school when, beyond sewing dresses, he explored the closets of his friends’ moms. Real Texas women were his earliest inspiration, which he said makes his couture more appealing and familiar.

“These women understand where I'm coming from,” Mai said, “because where I'm coming from is inspired by them.”

As a sophomore at St. John’s, Mai created his rst collection as an Independent Study Project with faculty advisor and former history teacher Bela Thacker. Famed couturier Paul Poriet was the main inspiration of the ISP, but he called John Galliano’s Dior Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2004 collection “the beginning of my love for couture.” Thacker kept the rst item from his collection, which Mai called “a terrible little skirt” and Thacker called

“One of my friends stole it from me,” said Thacker, who also mysteriously lost a bag that Mai had designed especially for her. “He was in so much demand.”

Even as a high school student, he was “very entrepreneurial,” Thacker said. She most admired Mai’s con dence that he would achieve his ambitions.

“It’s always nice to see students grow and become successful,” she said, “but with Bach, it’s a little extra special.”

Mai earned his bachelor’s in fashion at Parsons School of Design in New York City, which is among the best fashion schools in the country. In college, Mai said he slept only six nights a week, every week. He has worked with some of the most prestigious fashion houses in the world. After graduating, the budding couturier moved to Paris to assist in the fur studio at Oscar de la Renta and earned his master’s in fashion design from Institut Français de la Mode. After graduating, he worked for Prabal Gurung, and then under the tutelage of his longtime idol, John Galliano, at Maison Margiela.

In October 2021, Mai held the showroom presentation of his rst collection in his friend’s living room. Vogue called the collection, which featured custom lurex jacquard fabric and velvet made from metallic threads, an embrace of “unabashed femininity.”

When his publicist sent out invitations for the event, they initially received no replies from Vogue. That is, until the global director of

Vogue runway, Nicole Phelps, emailed back to reserve the next available appointment slot.

“My rst ever presentation appointment was with a director at Vogue.”

Five days later, his name was splashed across Vogue’s homepage for six days.

“My life has been insanity ever since then,” Mai said. “I haven’t stopped running.”

Since then, a slew of Hollywood A-listers have donned his dresses for star-studded events. Only a few weeks later, Venus Williams wore a silver dress from Mai’s inaugural collection at the closing night premiere of “King Richard” at the American Film Institute Festival in Los Angeles.

Most recently, Heidi Klum wore a blush silk-and-organza suit from the same collection on an episode of “Making the Cut,” a fashion competition TV series produced by Amazon Studios, while Lupita Nyong’o wore a blue moiré pantsuit and tweed bralette from Mai’s latest collection to kick o the “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” press tour.

It's one thing to talk about it, to hear about it. But to actually feel the power of Vogue behind you is a totally different level of craziness.

BACH MAI

“It’s one thing to talk about it, to hear about it,” Mai said, “but to actually feel the power of Vogue behind you is a totally di erent level of craziness.”

Mai’s soaring success allowed him to recruit a creative team in May. He said that building his own brand is one of the hardest things he has ever done, especially since he has to spend less time designing and more time leading.

“I've spent my whole life making clothes, not learning how to run a company,” he said. “Even though I have more people, it seems like there's more to do than ever.”

The video on Mai’s website showcasing Collection 2 takes place in a sparsely decorated room divided by clear plastic tarps. Many models have blue or white lipstick smeared across their mouths; one has branch-like twine glued around her eyes, and all move in slow motion to ethereal lo- music. Exposed pipes decorate the ceiling, illuminated by white neon poles.

The clean-but-industrial backdrop calls to mind his roots as a child of immigrants. He partners with Paris textile supplier Hurel to source fabrics reminiscent, in his words, of steel and oil spills, and prioritizes inclusive and diverse representation in his promotional material.