It was part of her routine. Every couple of days, Violet, not her real name, checked the Department of Education website to see if the updated FAFSA form was available. Some days, it was. Some days, nothing was there.

The process was similar to when she awaited the results of her Early Decision application, constantly checking to see if there were new messages.

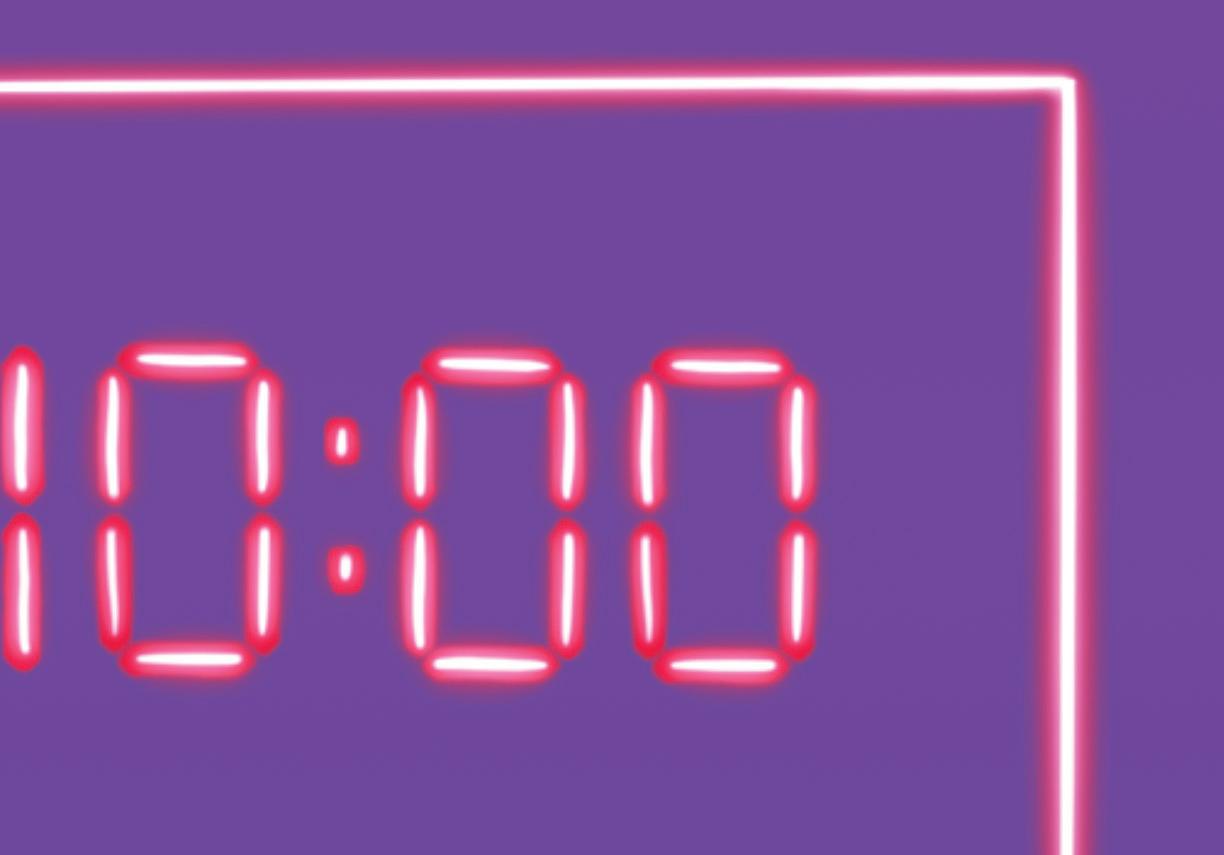

The revised Free Application for Federal Student Aid, known to applicant families as FAFSA, was originally supposed to come out on Oct. 1, giving the 17 million students until June 30 to fill out the form. But after the Department of Education made some changes to the site, the FAFSA was not released until three months later, on Dec. 30.

According to Forbes, one of the most significant changes is the new Student Aid Index, which replaces the Expected Family Contribution as a key factor in determining how much need-based financial aid students receive. While

FAFSA was launched in 1992

Almost 18 million people in the US submitted FAFSA forms from 2020 to 2021

85% of students receive some form of financial aid

There is no maximum income cap that determines your financial aid eligibility

Students must reapply through FAFSA every year

When Dean of Students Bailey Duncan sent out the weekly Spring Infographic on Jan. 22, it included a new policy:

“For safety and security, food delivery drivers (Uber Eats, DoorDash, etc.) will not be allowed on SJS campus. Please do not order food to be delivered.”

Sophomore Lachlan McFarland has ordered bubble tea and drinks on multiple occasions using DoorDash, but now he is not allowed to do so.

“I think it’s fine if it’s what’s best for the school,” McFarland said. “But honestly, it was nice to have the option to order food, and I wish we still could. It was a little thing that brightened up my day.”

The School has strict policies in place to monitor who is entering school property, whether it be parents or delivery drivers.

Richard Still, Director of Safety, Security, and Physical Plant, said that security personnel

the form has been streamlined with fewer questions to determine financial standing, students now have to report the income of the parent who provides the most support, not the income of the parent they live with the most. FAFSA also now pulls information directly from the IRS instead of asking families to fill it out themselves.

“It’s the hope of ease,” said Kenley Turville, St. John’s Director of College Counseling. “Parents being able to link to the IRS directly just eliminates a lot of forms.”

While FAFSA’s changes were meant to help students, they have caused a lot of headaches. Workarounds from previous years have been eliminated, so parents without a Social Security number cannot complete the form.

Students have also spent an excessive amount of time in a virtual waiting room because the website limits the number of people who can be on the site at once.

“That kind of thing usually happens when people are buying concert tickets, when massive

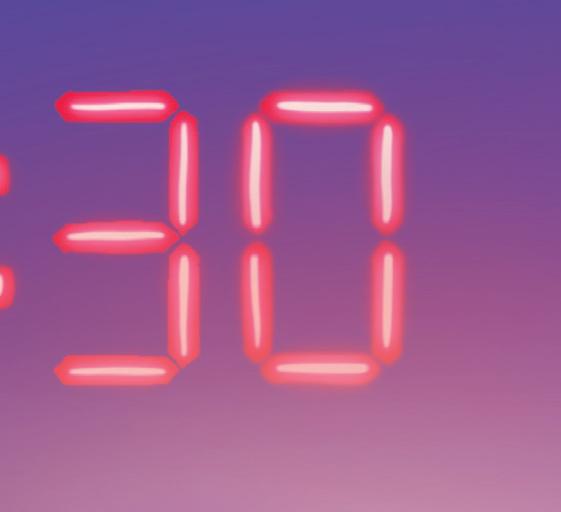

October 1 | FAFSA form scheduled for release

December 30 FAFSA form released January 30 | Dept. of Education says colleges will not receive information until “the first half of March”

June 30 FAFSA forms due

2024-25 school year | Student Aid Index will replace the Expected Family Contribution

ensured that drivers stayed in the Circle, leaving deliveries on the drop-off table. But as the number of drivers increased with the recent influx of orders, security could not keep up with all the visitors. Some delivery drivers even began wandering through academic buildings in search of whomever ordered the food.

It became an issue that needed to be resolved, and the policy needed to be clarified.

RICK STILL

“When it was three a day, or three a week, it was a lot simpler, but it got to the point where we were doing 16 to 25 a day,” Still said. “It just became too much of a risk.”

As more delivery drivers showed up at the School, notices of Uber Eats and DoorDash deliveries flooded security communication radios. Officer Still described it as a traffic jam in the Circle.

“It became an issue that needed to be resolved, and the policy needed to be clarified,” said Rick Still, Richard’s son, who conducts medical and fire assistance for the School. “We don’t know that they’re coming, we have no idea who these people are and I think that’s the biggest point.” Head of Upper School Kevin Weatherill said that in the fall, an independent campuswide audit assessed how school safety and security operated. The verdict was positive, yet the audi-

amounts of people are all trying to access a website at the same time,” senior Mia Hirshfeld said. “People have less time to gather and upload all of their information.”

Senior Bella Cantorna had to wait a few days to fill out her application, coming back to it a number of times before it let her finish. She described the process as “very inconvenient.”

“When I tried to fill it out the first four times, it wouldn’t let me move on to a different page,” Cantorna said. “Every time I put in my address, it would say it was invalid.”

This year, Congress told the Department of Education to adjust their calculations for inflation, but for unknown reasons, this change was not implemented. Without that adjustment, families needing financial aid look like they have more income than they really do, which reduces the amount of financial aid they are entitled to receive. According to NPR, the lowest-income families will not be significantly affected, but the “hundreds of thousands” of students just above those ranges will.

The Department of Education announced on Jan. 30 that FAFSA applications will not reach institutions until “the first half of March.” If a student is applying for financial aid, some universities also require students to fill out the College Scholarship Service profile — which costs $25 to send information to the first institution and $16 for each additional school, although some students can get the fee waived. However, CSS does not guarentee comprehensive financial aid for students. Tanya Cummings, Associate Director of College Counseling, said that colleges are not going to penalize students for the delay because they, too, are affected by it.

“Colleges don’t want people to pull out of ED agreements, so they will work with students,” Cummings said. “People lose their jobs, things change. FAFSA is a snapshot in time, but your life is happening in real time.”

tors recommended tightening security regarding food deliveries.

Through the window of his office, Weatherill witnessed the increase in delivery drivers entering the School to deliver food.

“We had drivers who were getting out of cars and entering buildings,” he said. “We’re not a part of the vetting process for drivers, so to have them walking around on campus is a huge concern.”

Weatherill does not blame the students, but the safety recommendation and surge in orders eventually necessitated the ban on food deliveries.

While he does not think students are directing drivers to enter school buildings, “drivers do, and we have to keep students safe.”

When asked about the prospect of students earning back the opportunity to make mobile food orders, Weatherill said, “We are open to possibilities, but we’re always going to keep people safe here on campus.”

Freshmen, sophomores and juniors may not order food during the school day. Seniors can order food and pick it up off campus.

While there will always be policies regarding food orders, they are subject to change.

odd Litton is no stranger to politics. From his rst time canvassing as a college student in 1990 to his rst campaign for o ce in 2018, Litton has spent most of his life involved with the Democratic Party.

Now, he has his sights set on the Texas Senate.

Litton was approached about running for Senate District 15 after a strong showing in his race against Dan Crenshaw for a U.S. House of Representatives seat ve years ago, in which he claimed almost 46% of the vote in a historically Republican district.

“The reason I got in this race is to stand up to the politics of fear and hate. It’s been practiced for far too long. And Texas is at the vanguard,” Litton said during a Feb. 1 visit hosted by the Young Liberals Organization.

He faces a crowded eld in the March 5 primary. Among his opponents is Molly Cook, an ER nurse who ran for State Senate in 2022. The seat had previously been held by Mayor John Whitmire, who served District 15 from 1983 to 2023.

His campaign focuses on ensuring access to abortion and gender-a rming care and investing in education, healthcare and infrastructure.

“Our people are our greatest resource. You have to invest in our people,” Litton said.

His son Jack Litton, a senior, says that recent state legislation and his distrust of those in power galvanized his father to run for o ce again.

“The issues that are most contentious right now in the Texas state legislature are the things that he has been talking about for the past ve years,” Jack said.

Litton is an attorney and mediator who runs his own practice and leads the investment organization SWAN Impact. He has served on the boards of multiple nonpro ts focusing on education and human rights, including Breakthrough Houston and The Children’s Fund.

His background in education and economics has led Litton to prioritize pushing for investment in early education and combating Gov. Greg Abbott’s proposed school voucher program, in addition to expanding Medicaid. He says his campaign intends to re ect the issues that matter to the people of District 15.

The jagged, horseshoe-shaped district wraps around North Houston and slices St. John’s in half. Its bizarre con guration is a result of the 2021 gerrymandering that grouped as many historically Democratic voters as possible.

Litton says that the more liberal demographics

of District 15 mean that in his upcoming race, he can be more vocal about his “opposition to the politics of fear and hate” than he was in 2018.

“I can be a little bit more Democratic,” Litton said. “I did have to be a little bit more thoughtful or careful about how I talk about some of my values. But I think in some ways it’s helped because, when I go to Austin, I’m going to be working with a lot of Republicans.”

Precinct Chair Ru Natarajan, who is actively involved in Harris County progressive politics and the great aunt of Upper School students Shaheen and Saira Merchant, predicts that the election will end in a run-o between Litton and Cook. She says that Litton’s experience is a potential draw for both voters and donors.

The reason I got in this race is to stand up to the politics of fear and hate.

“I worked really hard on his campaign when he ran for Congress, and I think the reason he has been able to raise money and do it so quickly is because of his level of maturity and the fact that he knows what he’s doing, in the sense that he has worked as a mediator,” Natarajan said. “He knows how to work in politics.”

Litton has been endorsed by the Harris County Tejano Democrats, the Texas Coalition of Black Democrats of Harris County, the Harris County Young Democrats, the Houston Federation of Teachers and Houston City Council Member Abbie Kamin.

His decision to run in 2018 was motivated by a surge in homophobia, xenophobia, racism and misogyny in national politics.

His children attended Roberts Elementary, where students’ families spoke over 40 languag-

es at home. While he saw the school’s mulitcultural community as a positive, politicians across the country were demonizing diversity.

“It’s this incredible school environment and learning environment,” Litton said. “When President Trump got elected in 2016, we heard so many things that were frankly contrary to that belief.”

Litton ran to help Democrats ip the House in 2018. His campaign raised over $1 million in Harris County alone, and he received more votes from Texas Congressional District 2 than Hillary Clinton did in the 2016 presidential race.

“I think I’m the best candidate in this race to get out the vote,” Litton said.

Despite District 15 being a “safe seat” for Democrats, YLO co-president Ava Mostyn says that the Litton campaign’s e orts to mobilize voters could impact future elections. She sees his strategy as “utilizing the way that the districts are drawn — even though they seem like they’re negatively drawn against Democratic voters — to try and bring out the vote.”

The pillar of Litton’s campaign is interacting with constituents. His son, who has canvassed for his father in both races, emphasizes the importance of face-to-face engagement.

“When you’re actually talking to people, they’re not going to reach into some book of extensive political theory about why we need to have a market-regulated healthcare system,” Jack said. “One of the most important things when you’re trying to kickstart a political movement is you have to really focus on life experiences because people can relate to that more.”

At the YLO event, Litton asked those in the audience who were eligible to vote to tap into their frustration at the polls.

“Be angry, get mad, get out and vote,” Litton said. “But try to do it in as constructive and positive a way as possible.”

Additional reporting by Ellison Albright

Last December, veteran trial attorney Nicole Perdue witnessed a presiding Civil Court judge fail to treat her client’s case with the care it deserved, consistently showing favoritism to the opposing side.

“My client was on the right side of the law, but on the wrong side of the judge,” Perdue said.

“The injustices were appalling.”

Shortly after, Perdue was approached to run for a seat on the 133rd Civil District Court. Recognizing an opportunity to prevent future miscarriages of justice, she accepted the challenge.

Perdue, the mother of William (’20) and John Perdue (’22) and senior Charlie Perdue, graduated from Texas A&M and South Texas College of Law. After working as an “Of Counsel” attorney for over 20 years, she decided it was time for a career change.

Perdue says that Harris County civil courts

struggle with accessibility and e ciency, extending the duration of cases and wasting taxpayer money. If elected, she plans to address these issues and facilitate a smooth and just process for those involved in the nearly one million cases that go through the Harris County judicial system every year.

Perdue’s background in employment law has provided her with the necessary experience to ensure everyone in her court is treated fairly. She hopes to run training programs for judicial employees that will e ectively manage bias in the courts.

“It’s important that all the sta members of the court go through that training to make sure that whatever they do, however they treat anybody in the courtroom, that everyone’s treated equally,” Perdue said.

She also promises to “keep her ngers o the

scales of justice” and make sure no one receives preferential treatment.

“I’ve made it clear with everyone who has given me money, and I’ve raised a lot, that simply because they have given me money to run, they shouldn’t expect favorable rulings,” Perdue said. “That’s not the way I’m going to run my court.”

Perdue says that she is uniquely quali ed for this position because of her extensive background in civil trial law and connection with the community.

“Experience matters — that’s the theme of my campaign.”

The election for 133rd Civil District Court will take place March 5.

At the beginning of her freshman year, Julia Mickiewicz did not think she would last a semester in the Speech and Debate program. Now a junior, she co-captains the St. John’s team and is a member of the elite Team Texas.

Mickiewicz competes in one of the most popular formats of international competition, World Schools Debate. WSD is a team event: up to five debaters can compete as a group, with three speaking in every round. The 2023-24 Team Texas comprises 16 members, who are divided into smaller teams when competing in tournaments.

The Texas debate circuit is one of the most competitive in the nation, and Team Texas frequently competes against Team USA, which represents the country on the global stage.

“It feels really good to be surrounded by like-minded people who care a lot,” Mickiewicz said. “It’s so much fun. Because I don’t have anything to prove to them—I already got here. They already all got here.”

SJS debate coach Jon-Carlo Canezo says that what separates Mickiewicz from others he has coached and judged is her comittment. In addition to leading after-school practices, Mickiewicz regularly attends local tournaments and competes with friends in online international events.

“You can’t teach passion, you can’t teach dedication,” Canezo said. “Her commitment shaped her understanding of the activity and how much time she poured into debate.”

Prior to her freshman year, Mickiewicz had no experience in debate. When she attended her first club meeting, she admitted to Canezo that she probably would not stick with it. She chose WSD “because that was what everyone else who was my age was doing.”

At her first tournament, she competed alongside other freshmen new to the format. Mickiewicz received a score of 77 out of 80 on one of her speeches, an unusually high score for a novice. Her team proceeded to elimination rounds but suffered a devastating loss to a more experienced team.

“Do you ever get beat so bad that you’re like, ‘I can’t live with myself being bad anymore?’” Mickiewicz said. “That’s what made me want to be better.”

Motivated by the crushing defeat and her strong individual showing, Mickiewicz decided to make debate her priority.

“I was just like, man, I’m actually really good at this,” Mickiewicz said. “So then it built in me this insane ambition to be good.”

After that first tournament, Canezo sought to nurture Mickiewicz’s talents. In addition to encouraging her to attend prestigious debate summer programs and apply to selective teams, he asked her to compete on the St. John’s WSD team at the National Speech and Debate Tournament in Louisville, Kentucky.

You can’t teach passion, you can’t teach dedication. Her commitment shaped her understanding of the activity and how much time she poured into debate.

JON-CARLO CANEZOCanezo says that her presence on the team was one of the reasons why the St. John’s team placed in the top 64 teams in the nation.

As she gained experience in the format, Mickiewicz began to focus on also teaching Middle School debaters about WSD. Beyond after-school practice rounds, Mickiewicz often brings underclassmen interested in the format with her to local tournaments. Sophomore Leetyan Chen has attended multiple tournaments with Mickiewicz. Afterward, she gives Chen feedback.

“Julia’s really good at what she does, and is respected within the debate world as a whole,” Chen said.

Mickiewicz’s team will attend the Cal Invitational UC Berkeley tournament on Feb. 17 with St. John’s teammates Shaheen Merchant, Aleena Gilani and Angela Ma. Despite Mickiewicz’s skill, Merchant says she still treats every round with equal importance.

“She’s very humble and she will always treat every competition like it’s not a guaranteed win,” Merchant said. “She’ll always be trying to prepare herself even if she has a pretty good chance of winning.”

In September, Mickiewicz and Team Texas advanced to the final round against Team USA at the Greenhill Fall Classic in Addison, Texas, one of the most prestigious tournaments in the state. In December, Team Texas won the Isidore Newman Invitational in New Orleans.

In her free time, Mickiewicz participates in international debate tournaments with teammates she met at debate camp. Mickiewicz says international competitions are notoriously unpredictable: one round she might face off against a novice team and the next she may be competing against the Korean or Mexican national teams.

“The only consistent thing throughout all of them is that they’re literally done over Discord,” Mickiewicz said.

While she has collaborated with many teams in her career, Mickiewicz describes debating on Team Texas as a unique experience.

“On Team Texas, I feel 100% supported,” Mickiewicz said. “It’s just like everything falls into place. I can tell I’m firing on all cylinders. I’m competing at my best when I’m with them.”

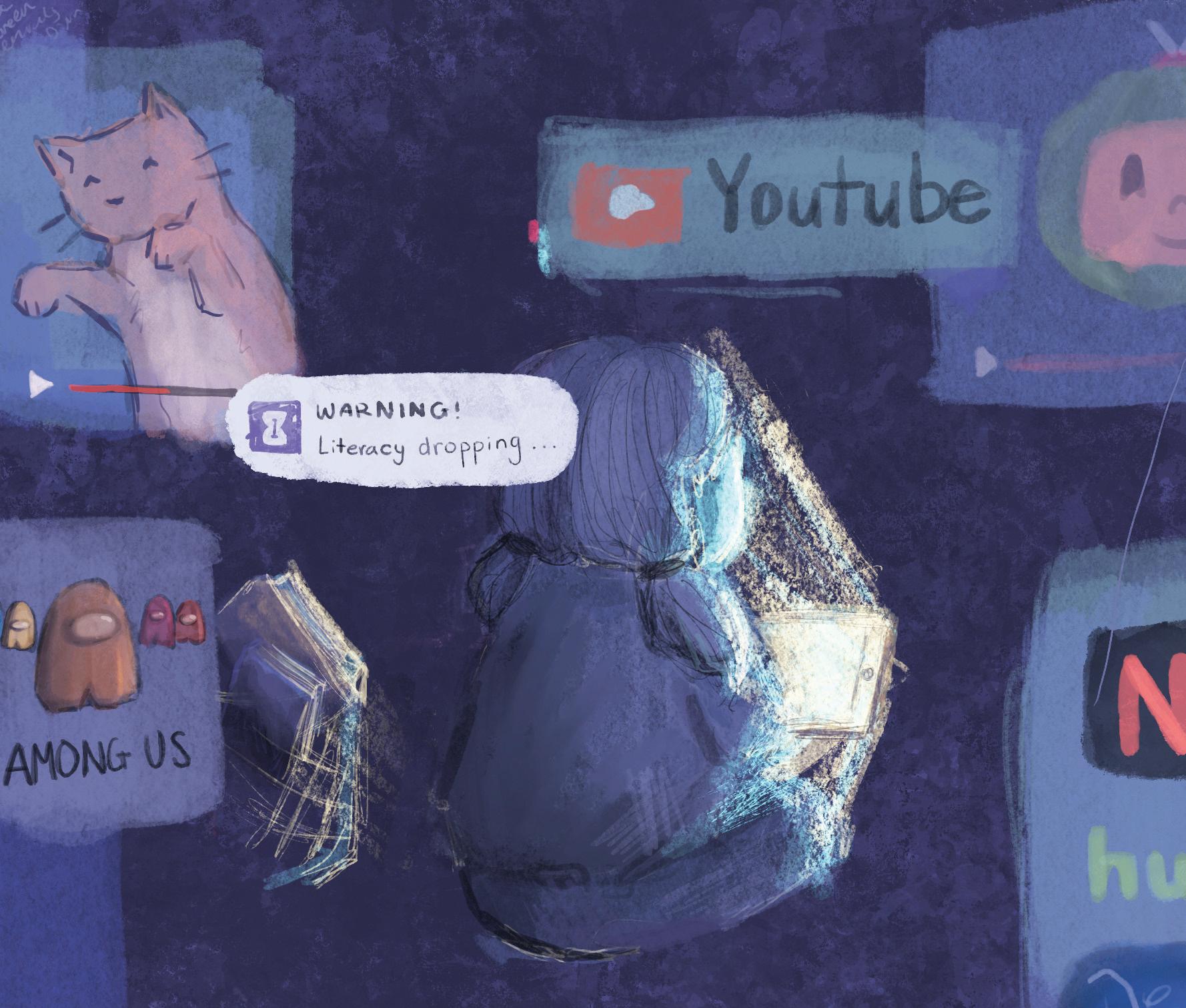

Goodbye, Tristar Web Graphics (1953–2024): We’ll miss you

Story by Lee Monistere & Dalia SandbergYou may have noticed that the paper looks a little different. That’s because it is.

The first thing you’ll notice is that we have two sections because our new printer can only print 16-page sections. So, for the first time in Review history, we have a special section: Body & Mind.

If you were even wondering how The Review was able to finish an issue at night and then have it hot off the press ready to be picked up the next morning, it’s thanks to Tristar.

Tristar Web Graphics, our previous printer, had been in business since 1953, and their business closed at the end of January. Our new printer is Blue Star Printing. So now, we bid a

fond adieu to Tristar and Ted Mazza, our printing point-of-contact for over a decade.

As we say farewell to Tristar, we reflect upon all the memories we have made. Sophia Jazaeri (’23), our previous production manager, recalls the first time she went to pick up the paper.

“I was stressed and nervous, but Mr. Mazza and his employees were endlessly kind to me,” Jazaeri said. “They treated me with respect and understood exactly what I was doing.”

Every night before The Review went to press, Mazza would contact Jazaeri to ensure that the issue was ready to go. Jazaeri, who was juggling late nights at Review with tech rehearsals for the winter play, “The 39 Steps,”

felt “frenzied because the paper was going to come out late.”

“He was supportive, excited, and truly wanted to help out The Review in any way he could,” Jazaeri said. “He has a creative, determined spirit that is infused into the paper.”

The Review appreciates everything Tristar has done to ensure that our issues — both literal and figurative — were sorted out.

“Every time we had to make a last-minute revision, edit, or adaptation to a mailing list, he was supportive and accepting,” Jazaeri said.

Although we will miss the late-night calls and early morning meetings with Tristar, we look forward to creating new memories and fostering our relationship with Blue Star.

HIT, BREAK, WIN Julia Mickiewicz, far right, celebrates with Team Texas teammates after winning 2nd place at one of the state’s most prestigious tournamentsAfter a long day at school, a dozen or so students head across the street to the dance studios to change into leggings and ballet slippers. After friendly greetings and light stretching, the dancers wait for Upper School math teacher Alice Fogler to start class with pliés and piqués. After dozens of combinations, the once tentative students have accomplished their dance routines.

But these students are not future Terpsichore or Caprice dancers. They are faculty and sta who have from zero to more than 20 years of dance experience.

Fogler has taught 45-minute ballet classes every Monday since October. Ranging from 5-15 participants, the classes are a convenient way for faculty to both exercise and connect with each other.

“My goal is for these classes to be some nice exercise, nice stretching and really just for people to have fun,” Fogler said. “It’s a positive environment where you get to learn something new.”

Consisting of a typical barre routine, Fogler’s lessons cater to the faculty’s abilities. The day before the rst class, Fogler spent several hours planning in order to make combinations that were appropriate both for beginners and the more advanced.

Fogler takes the combinations she enjoyed as a student, nds ballet playlists on Spotify and adapts them to t the music.

“It’s been several years since I’ve taken a ballet class, so it took me a second to get back into the swing of my brain working in that way,” Fogler said. “It’s an undertaking, but it is a labor of love.”

Upper School French teacher Elizabeth Willcutt has found the classes both challenging and cathartic. Once a serious ballet dancer, Willcutt’s

range of motion became restricted after a shoulder injury in 2019.

“It changed my relationship to movement and to dance — in particular ballet,” Willcutt said. “I’m nding that I have more strength now; I’m more present in my body.”

For Willcutt, Fogler strikes the perfect balance in the dance studio.

“She’s patient, enthusiastic and communicates very well,” Willcutt said. “She reminds me of some of the great ballet teachers that I had growing up and why I fell in love with it in the rst place.”

Fogler began dance training in eighth grade and was a Johnnycake regular. Although she started later than most dancers, she pursued her passion throughout high school and even taught ballet and jazz to young kids as a dance camp counselor at the Jewish Community Center.

“I was that teenager doing the side ballet so the really little kids could remember the choreography,” Fogler said.

Fogler majored in math and minored in dance at Washington University in St. Louis. Although teaching AP Calculus and ballet may seem di erent, Fogler nds common ground.

“No matter what you’re teaching, you want to share a passion of yours with your students, and that’s de nitely true for teaching math and dance,” Fogler said. “They are both things that I have loved for a very long time, and I get to share that with people who may not have experienced that same level of love.”

The class was the brainchild of Upper School counselor Ashley Le Grange. While learning cheer choreography for the faculty talent show in September, Le Grange recognized Fogler’s skill and willingness to help others. She pitched the idea to Fogler and then started to spread the word.

“Some of us just ordered our ballet shoes and tights o Amazon and we were already living our childhood dreams,” Le Grange said.

The classes, which meet every Monday after school, have been an outlet to build camaraderie and meet new people.

“I’ve gotten to know faculty in both the Middle and Lower School that I wouldn’t have gotten to meet otherwise,” Fogler said. “It’s been a really nice experience.”

In Gabryella Castillo’s rst year at St. John’s, she landed a position in both the academic and the athletic worlds — becoming both the college counseling receptionist and JV girls’ basketball coach.

Last year, Castillo was working at YES Prep White Oak when she heard about the job opening, which she initially ignored— but a friend convinced her to apply.

Castillo was a two-time all-district player from Duchesne, where she graduated in 2016. She nds that SJS shares similar values with her alma mater.

“I met Dr. Weatherill and a couple of members from the team,” Castillo said. “I liked the vibes and everything that St. John’s was about.”

Castillo is now the college counseling receptionist, a job that involves a signi cant amount of scheduling and calendaring. She makes sure college counselors keep their meetings on track and organizes College 101 sessions and seminars for upperclassmen — including creating much of the visual content seen at the sessions.

Working as Operations Coordinator at YES Prep gave her behind-the-scenes experience to organize events including catered lunches and eld trips.

Castillo’s basketball experience has also made her a valuable addition to the basketball coaching sta .

“She was a really fun basketball coach and used her background to help our team get better,” freshman Jordan Frawner said. “She always made sure we worked really hard.”

Since taking the job at St. John’s, Castillo has made many friends among the faculty, including college counselor Steven Scales.

“My immediate impression of her was that she was very smart, organized, capable and fun,” Scales said. “She just had a really good energy, and I could tell that at her old job she took care of everything.”

Castillo was recruited to play collegiate basketball on a Division II team, playing one season at the University of Arkansas-Fort Smith, and then transferring to UT Dallas, a D-III school where she played for two seasons. At 5-foot-6, Castillo was the shortest on the team, so she usually played point guard.

For two summers, Castillo played professionally in Mexico. Her dual citizenship allowed her to move back and forth between countries.

“I loved playing in Mexico,” Castillo said. “I could play the sport I loved at an extremely competitive level, I had a lot of family there to travel to my games and I was surrounded by great food and culture.”

Her collegiate career was riddled with injuries.

“I used to have a really bad problem with

dislocating my knee — it would pop out all the time,” Castillo said. “Finally, after I dislocated it for the third time, I had an invasive surgery in which they screwed my kneecap into place with a titanium rod going from my kneecap to the middle of my shin.”

After rehab, she was back on the court playing defense when a misstep snapped her foot in half down the middle. She was required to get yet another surgery on her left foot.

“When I went to the doctor, he told me that my injury was really common in linebackers because they’re always on their toes,” Castillo said. “So when he saw me, like ve-foot-nothing, he was surprised.”

Recovery was brutal, and once Castillo relearned to walk, she decided it was time to stop playing. Although her injuries proved to be stubborn obstacles, Castillo discovered ways to take better care of herself. She started stretching, went to trainers and did heating treatments.

The foot injury ended Castillo’s basketball career, but it allowed her to discover a love of coaching. She worked as an assistant at UT Dallas before joining the coaching sta at the University of St. Thomas in Houston.

Now with the Mavs, Castillo especially enjoys the basketball team’s bond.

“Everyone has their own personalities, but we all get along really well,” Castillo said.

Just before Max Melcher graduated from St. John’s in 2014, his parents gave him a “discovery ight,” a short introduction ight for those interested in getting a pilot’s license, as an early graduation present. He fell in love with aviation right away.

Melcher’s father had a commercial pilot’s license and ew corporate jets, while his grandfather had a private pilot’s license. By the time Melcher graduated, he had already soloed, or own the plane on his own.

“Once you pull back the yoke and lift o the ground and you are in full control of something that’s soaring through the air under your direction, there is no feeling like it,” Melcher said. “And when I’ve been away from aviation for a while, I get a kind of yearning to have that sensation again.”

SPREADING

HER WINGS

Jackie Thomas, who has wanted a pilot’s license since middle school, trains in a Cessna

Melcher has since bought and later sold his rst plane, a small Cessna, which he ew by himself to Canada, Mexico, and Cuba, during the brief window under the Obama administration when private ights were allowed to the Caribbean island.

Owning an aircraft is more a ordable than one might expect.

Controller.com listed 26 aircrafts

for sale under $45,000 — less than the average price of a new car, according to CBS News. But, as with any form of transportation, things can go wrong.

One time, on a ight to Oaxaca, Mexico, Melcher did not pay a service to help him navigate the landing process, assuming that he would gure it out on his own using his Spanish. The wife of the comandante at the airport ran the service, so the comandante refused to give Melcher any fuel, and he was brie y stuck at the airport. Luckily, he had just enough fuel to get to the next airport.

Melcher still dreams of owning another plane when he has more time. “You take on some risk, but when you own a plane, you have a good sense that the plane’s being maintained,” he said.

Though Melcher has a commercial license and can charge people for ying them on sightseeing tours or skydiving trips, he has not worked in the aviation industry except for a stint in fueling general aviation planes while attending Texas A&M. He credits his aviation experience with giving him the skills to succeed in the private sector.

“The cool thing about ying is

that, when you’re up in the air, you can’t ask for more fuel. You can’t ask for better weather,” Melcher said. “The kind of planning that I got from going through ight school and that preparation and mindset you get with working with other pilots has really helped me when it comes to professional work.”

Once you pull back the yoke and lift off the ground and you are in full control of something that’s soaring through the air under your direction, there is no feeling like it.

MAX MELCHERIn 2017, Melcher began working as a project manager for Chainlink Labs, a company that develops the blockchain—a ledger that recordsnancial transactions. He compared his day-to-day work to developing a ight plan.

“There’s going to be things that come up, even if you have the best ight plan in the world. You have to have the ability to adapt on the ight,” Melcher said.

Melcher enjoys meeting and working with fellow pilots. “It really is one of those things that’s going to be with you the rest of your life when you run into another pilot. You have a connection already,” he said.

When he is not working or ying planes, Melcher tries to nd time for improv comedy. “Comedy has been something, even outside of performance, that has helped me in life with meetings, with relationships and with just accepting adventure.”

Melcher dreams of one day ying his own plane around the world, becoming a “white-haired ying instructor” with an endless supply of stories.

“To have those stories — they convey a lot more when you’re teaching something,” Melcher said. “One of the things I love to do is get back in the right seat and instruct young pilots, because you get to see their emotion and excitement when they take o and when they get that ‘aha moment.’”

At the SJS Network Social in November, Melcher met Jackie Thomas, a junior training to get her pilot’s license.

“It’s very impressive that she’s able to do this on top of the St. John’s course load,” Melcher said.

“I’m amazed.”

Back when she was in Middle School, Thomas began asking her parents if she could take ying lessons. She went on her rst discovery ight at 15.

One of her neighbors at her parent’s house in Coronado, which Thomas visited every summer, was a navy pilot, so she grew up around navy planes.

“I’m gonna be honest — when I was little, I was obsessed with Top Gun,” Thomas said.

From a young age, Thomas had been gliding, or getting towed up by a small plane and then released to glide back down, which inspired her to try ying.

Today, Thomas takes ying lessons two or three times a week.

“When you’re in the air, once you understand what you’re doing, how the plane responds to it, it’s kind of like driving,” Thomas said. “You gure out what to do.”

Thomas recalls how exciting her discovery ight was. Even though her lessons require more focus so she can execute the correct manuevers, they still excite her.

“Flying was a good break from everything,” she said. She has not yet soloed, but she expects to soon.

“It’s not a joy ride. You have to focus on what you’re doing that lesson and what maneuvers you’re working on,” Thomas said.

For Thomas, the joy of ying is all about the departure.

“Even if I’ve done it a thousand times, taking o is still fun.”

CSpires is easily recognizable on campus as one of the only teachers sporting visible tattoos, including a complex sleeve on his left arm. The Chemistry and AP Physics teacher is also an avid trivia buff and, according to his students, a thoroughly engaging educator.

His other claim to fame is that he is a two-time “Jeopardy!” champion who won $33,000 in his three appearances.

Spires developed his love for trivia as a child and watched current “Jeopardy!” host Ken Jennings win 74 straight games in 2004 while in middle school.

“I pick up a lot of random knowledge, and it tends to stick in my brain,” Spires said. “I enjoy knowing a little bit about everything.”

His students find that they can talk to him about almost anything.

“Even though I’m still getting to know him, we’ve bonded over trivia knowledge,” said freshman Nathalie McDaniel, one of his advisees.

Spires auditioned for “Jeopardy!” while he was in law school. He was called for the show in February 2016 and taped his games a few weeks later. His reign lasted three episodes.

One of the questions featured his favorite book, Stephen King’s “The Stand.”

“I remember thinking as that question was

being read out, ‘If I don’t get this, I’m going to be so upset with myself,’” Spires said. Thankfully, he was first on the buzzer.

Spires’ background is as varied as his classroom decor. He earned his bachelor’s in physics at Rice in 2013 while also appearing in a number of university theater productions.

I pick up a lot of random knowedge, and it tends to stick in my brain. I enjoy knowing a little bit about everything.

Spires later earned a law degree in his home state at the University of Alabama and briefly worked as a patent attorney in Houston.

In 2019, Spires acted in a Rice student production of Shakespeare’s “As You Like It.” Mentoring the undergrads in the play eventually led him to become a teacher.

Coming from a line of educators, Spires always heard his mother tell him that he would make an excellent teacher, an idea he began to consider more seriously when he was contemplating leaving his legal career.

Also factoring into his decision to leave the legal profession was a diagnosis of ADHD as an adult. When he was younger, he thrived in the structured school system but later found it difficult to focus without the rhythm of an academic environment and the “reset” after every school year.

His diagnosis was a game-changer.

“That whole experience was transformative for me,” he said. “I learned a lot about myself and refocused on what sorts of things might make me actually happy.”

After the diagnosis, Spires took his mother’s advice and became a chemistry teacher at Houston YES Prep White Oak in 2021. He knew he had found his path.

“The first moment I stepped foot in the classroom, I knew this is what it’s supposed to be

like. And every second of it since has validated that,” he said. “I enjoyed being back in an environment where there is a joy and a purpose in knowing things and learning.”

As a first-year teacher, Spires has co-advised with English teacher Clay Guinn. Though he will likely be assigned his own advisory next year, Spires has enjoyed getting to know his freshmen and frequently pops into adjacent science classrooms to chat with other students.

If he ever runs out of stories about “Jeopardy!” or any other bits of trivia, his body art serves as a conversation piece.

“I’m a person who wears my heart on my sleeve,” he said. “I’m a very open person, and I want that to be apparent at all times.” And when he speaks of sleeves, Spires means it literally. After debating the idea for a year and a half, Spires decided to get his first tattoo one year after appearing on “Jeopardy!”— two exclamation marks in the game show’s classic font represent his two wins. His next tattoo was a Spider-Man logo on his left wrist.

I look at my arm every day and love the way my personality is visible on me.

Spires began to design his complex sleeve of tattoos that consists of motifs representing parts of his life, including the Alabama state bird, the yellowhammer; the Texas state flower, the bluebonnet; a California kingsnake, inspired by his childhood pet; Rice’s mascot, a great horned owl; and Aragorn’s sword from “Lord of the Rings.”

The skeletal formula of dopamine on his right forearm serves as a reminder of how his ADHD diagnosis helped him find a career that makes him truly happy.

“I look at my arm every day and love the way my personality is visible on me,” Spires said. “It changed my life.”

Kacey Chapman (’23) rst suspected something was wrong just before midnight on Oct. 28. The Rice University freshman had spent weeks looking forward to the school’s notorious Night of Decadence — a university-wide party, or “public” as they are colloquially known around campus, where the dress code entails wearing as little clothing as one feels comfortable. Chapman arrived at the party expecting to see all manner of debauchery, but what she didn’t anticipate was the event getting shut down with several of her peers either hospitalized or in handcu s.

medical treatment this year due to overconsumption of alcohol. Seven students were hospitalized. Although no arrests were made, six students were handcu ed and sent to Rice’s Student Judicial Programs for conduct violations. Rice shut down NOD after a few hours because school and city medical resources were “becoming completely overwhelmed.” According to the Rice student newspaper, the Thresher, Wiess Chief Justice Renzo Espinoza told students in an email that “any more stress on the campus and the city resources would have put us in a very bad position.”

In the weeks leading up to Night of Decadence, Wiess College, one of Rice’s 11 residential colleges, had “NOD” spelled out in lights in their quad. All around campus students were bombarded with silly posters decorated with eggplant emojis or quotes from the Barbie movie, all communicating one message: This was not a party to be missed.

The next morning, countless bottles of hard liquor, de ned as any beverage containing over 40% alcohol by volume, were littered around Wiess.

drinks before and during every house party she attends, about once a month.

When the tickets became available online, so many users ooded the registration form that the website almost crashed, and those who didn’t immediately RSVP were unlikely to get a ticket. Yet even students who had not secured a spot couldn’t resist indulging in gossip about the upcoming party or helping others pick out their wardrobe — or lack thereof — in the days beforehand.

Since its inception in 1972, Night of Decadence has not struggled to drum up attention, excitement and, every once in a while, controversy.

“NOD is the most anticipated public of the year,” Chapman said. “It’s a totally sex-driven, sex-inspired event. And of course, people thinking about that and wearing next to nothing is going to lead to them consuming an abnormal amount of alcohol.”

In 2012, almost a dozen students were hospitalized with alcohol poisoning the night of the popular Halloween party. In response, Rice tightened its restrictions on hard alcohol and the number of people allowed at publics. More than a decade later, excessive alcohol remains an issue.

Even though prohibiting alcohol at NOD was intended to curtail drinking, the unintended consequence is that students tend to drink excessively before the party, which is one reason why over two dozen students required on-site

Pregaming typically means you’re getting drunk, and then at the party you’re getting even drunker, which means we’re probably engaging with someone who is binge-drinking.

TIM RYAN, PREVENTION SPECIALIST

Some Rice administrators cite pregaming as a factor contributing to the NOD shutdown. Students consumed excessive amounts of hard alcohol prior to the event, enough to last them through the night.

“There have been issues at each public party this semester around pre-gaming before the event, uncivil behavior in the lines, and disrespectful attitudes toward volunteers, caregivers, and other sta working at the events,” Rice’s Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Bridget Gorman wrote to students in an email, obtained by Houston Public Media. “This cannot be tolerated.”

Jessie is still guring out how to manage the unpredictable e ects of pregaming. One weekend earlier this year, she drank shot after shot of vodka, underestimating the toll it would take. Since it was a more expensive brand, she had been told it would have less of an e ect, so she gured it would even out if she drank more. She quickly became “very far gone.”

“If I had taken it slower, I wouldn’t have gotten myself in that situation.”

Tim Ryan, a lead prevention specialist at Pathways for Prevention, which aims to educate students about substance use and abuse, is visiting the Upper School later this month. He identi es pregaming as a unique type of drinking.

“Pregaming typically means you’re getting drunk, and then at the party you’re getting even drunker, which means we’re probably engaging with someone who is binge-drinking.”

Iris cites the fear of not being intoxicated enough as the main reason why she ends up drinking too much. A few months ago, she split a bottle of tequila four ways with some friends before a party, the rst one that had been thrown in several months. She doesn’t remember much about that night, but she has not been able to drink tequila ever since.

In an e ort to curb her social drinking habits, Iris occasionally volunteers to be the designated driver. She used to drive others frequently, but lately she is reluctant to do so.

Rice is reviewing its alcohol policy for undergraduates and canceled all public campus parties until after spring break.

“I understand why the school reacted the way they did. It was such an extreme situation,” said Brandon Lozano (’23), another Rice freshman. “However, I do have this feeling that once underclassmen are allowed to go back to publics, there will be a large burst of students going all-out for those events, which could lead to something where many people go overboard again.”

About one Saturday a month, Iris heads to a nearby gas station. She’s on good terms with the 50-something cashier (he always tells her that she looks pretty), so when she approaches the counter with a 10-pack of Fireball cinnamon whiskey shooters, he never asks for an ID. Sometimes, he even throws in a couple extra, free of charge.

And so begins the pregaming process for the high school student. After that, Iris heads back home to do her makeup and maybe straighten her hair before going to a friend’s house around 4 p.m. She and her friends take inventory of the drinks they’ve collectively procured, either with fake IDs or parental assistance. Inevitably, there is never quite enough, so someone will head to a nearby gas station or back to their house and scavenge for more.

Iris’s goal is always to “get drunk enough that I’m really drunk, but not so drunk that I throw up.”

For Iris, and many of her peers, pregaming is essential to achieving this delicate balance.

Jessie, a self-described chronic overthinker, never arrives at a party sober. In an environment meant for carefree fun, she prefers to leave her usual inhibitions at home. She

“It’s just not fun unless you’re drinking,” she said. “When you’re sober, you’re just annoyed that you’re surrounded by drunk people.” Jessie has been chided for her drinking habits, even by her closest friends.

People get nervous about something that, when you think about it, is so dumb. You’re standing around with your friends in someone’s backyard. That’s not an event you need to be hyped up or nervous for.

“LIAM”

“It comes from a place of love, but it feels very judgemental because I think they take on a superiority complex about it, almost as if being a nondrinker is a badge of honor,” Jessie said. “The hardcore drinkers see it the other way around: getting wasted and blackout drunk is a badge of honor that they have that nondrinkers don’t. It’s just toxic all around.”

Data from a 2021 survey of St. John’s students conducted by the Freedom from Chemical Dependency Foundation reports that 48% of 10th through 12th graders typically do not drink alcohol, 65% either do not drink at all or typically drink only once or twice a year. And 79% of those students either do not drink at all or drink once a month or less.

Since her arrival in 2018, Upper School counselor Ashley Le Grange has partnered with FCD and Pathways for Prevention to collect this data and meaningfully communicate it to the student body in yearly information sessions. She

pared to capitalize on the rare opportunity to shake things up that parties o er. She concedes that she’s more likely to say the things that will enliven her social life if she’s under the in uence — and it’s an insurance policy in case she says something she later regrets.

Liam says this mindset is a byproduct of an environment that requires students to give the stereotypical 110% every day of the week. The constant grind leads students to feel stagnant and socially restrained. Parties are the panacea for the all-consuming monotony of academics, and so there is a pressure to make the most of them.

“People get nervous about something that, when you think about it, is so dumb,” he said. “You’re standing around with your friends in someone’s backyard. That’s not an event you need to be hyped up or nervous for.”

Based on survey data, SJS has a higher rate of pressure related to performance than it does generalized anxiety. The way many students alleviate this stress is through the use of substances.

THE NUMBERS

95% Students who have never used substances before a school event

thinks it’s important to note the discrepancy between the real statistics and the typical assumption that a majority of high school students are regular drinkers.

“When I think everyone is doing it, that’s when I’m more likely to participate,” she said. “But when I think there’s a risk associated, I’m less likely to participate.”

Le Grange disagrees with the common sentiment that high school kids must “learn how to drink” before they go to college, citing statistics that indicate a direct correlation between the age one starts drinking and the risk of alcoholism later in life.

Liam never drank in high school. He was still social and regularly attended parties, but he just didn’t like the idea of putting himself in a potentially embarrassing position.

Now in college, Liam has begun indulging in a few beers before he heads out. He feels like he wouldn’t be “sucking the marrow out of life” if he opted for an entirely sober college existence. Nevertheless, he has strong boundaries in place — only on Saturdays, and never have a headache in the morning.

“If I realize the next day that I did something out of my control, that’s a signal that I need to take a break for a while.”

But Liam doesn’t think the few drinks he partakes in once a week have that much of an e ect. Mostly, he feels a bit more relaxed and inclined to be open with new acquaintances. When it comes to hanging out with people he knows and cares about, he considers himself at his best when sober.

Jessie likens drinking to conditioning.

“I think of it like running. You can go running without running shoes, but it’s way better when you have them,” Jessie said. “That’s like a party, you can go to a party without drinking, but for me at least, it enhances everything.”

“Maybe if St. John’s kids had some mountains around, they’d go for a hike one weekend instead piddling around at a party in West U,” Liam said.

Even so, Iris and Liam agreed that alcohol use at SJS is mild compared to the behavior they have observed or heard of at peer institutions like Kinkaid and Episcopal.

Dakota usually wakes up the morning after a party “feeling like a sinner.” Like many of her peers, she cannot avoid the guilt associated with drinking, and she does not want to exist in an environment where intoxication feels like a prerequisite to connection.

Le Grange is likewise worried about the long-term rami cations of linking alcohol with sociability. She says that by drinking at all parties, students are telling their bodies and brains that they need to use substances in order to get through the night without being uncomfortable. For developmental purposes, the adolescent brain needs to do that on its own, without chemicals, before they’re introduced into the equation.

“The repercussions are scary,” Dakota said. “But right now it just feels like a part of high school. I don’t know if it’s a part I’m willing to miss out on.”

O43% Students who have never had a drink

69% Students who typically do not drink

89% Students who do not drink or drink once a month

88% Students who think SJS culture does not pressure people to drink

76% Students who say their parents do not permit them to drink

Data from 2021 Freedom From Chemical Dependency survey given to all Upper School students

ne reason Liam never drank in high school was that he didn’t subscribe to the usual philosophy of high school parties — he never saw them as an exciting opportunity for new developments in his social life. For him, it was just hanging out at someone’s house for a few hours. But he felt alone in this mentality.

“Amongst the people who can’t bring themselves out of their shells enough to start serious things while sober, they use that once-a-month excuse to put all the chips on the table,” he said.

Iris regrets her growing reluctance to attend a party without drinking rst. But without pregaming, she feels ill-pre-

Rarely do I look forward to awards shows. This season has been pretty dismal, save for Kevin Costner endearingly reciting America Ferrera’s “Barbie” monologue back to her while they were presenting at the Golden Globes. The 66th Grammy Awards were an exception. I put the event on my shared calendar half because I wanted to watch my favorite artists clean up and half because I needed to alert my family that the TV would be unavailable after 7 p.m.

Ever since Grammy nominations came out in November, I have been making predictions on who would and should win. It is a hallmark of awards season for an iconic yet repeatedly unlucky performer to take home their rst trophy for a middling performance (think Jamie Lee Curits’s Oscar for “Everything Everywhere All at Once” or Leo DiCaprio for “The Revenant”).

This year, the Grammys bestowed Record of the Year and Best Pop Solo Performance to Miley Cyrus for “Flowers.” That was a swing and a miss for the Academy. Her dance moves were oddly impressive and her hair was otherworldly, but Miley’s poor performance re ected the Liam Hemsworth-bashing single’s mediocrity. Performing live, she awkwardly blurted out things like, “Don’t act like y’all don’t know this song!” to the audience’s visible horror.

This awkward mis re was rivaled only by the reaction to Taylor Swift’s announcement of her new album “The Tortured Poets Department” during her acceptance speech for Pop Vocal Album. For a decorated vocalist, she was surprisingly tone deaf. Later, during her acceptance speech for Album of the Year, she brought her friend Lana Del Rey onstage after besting her in the category. Del Rey has not one Grammy; Swift was accepting her fourteenth.

Junior Izzy Ibarra, a dedicated Lana stan, was appalled. “Wouldn’t you want to be alone with your feelings? You haven’t even had ve seconds,” she said. “Just ve seconds. And the way she pulls Lana behind her and drags her along like a puppy…”

I am not going to give any more ink to discussing how the world is in its Eras Era, Taylor Swift is an economic powerhouse, etcetera. She is undeniably in uential and deserved some sort of honor, but “Midnights” did not. I suggest the Recording Academy make another career award category similar to the Dr. Dre Global Impact Award for this kind of accomplishment.

“Some sort of recognition was deserved because of the e ort that she has put into this industry,” junior Skylar Gross said. “But then making it about the album? It wasn’t that good.”

But not all the star-power exes were terrible; the evening’s performers were expertly picked, and the “In Memoriam” segment was essentially awless. Stevie Wonder sang “For Once in My Life” alongside archival footage of Tony Bennett, and Fantasia delivered a powerful homage to Tina Turner with an elaborate rendition of “Proud Mary.” The only thing missing was a tribute to the late Jimmy Bu et. R.I.P.

In another year, Billy Joel’s performance of his rst single in 30 years would have been the highlight of the night, but the sheer theatricality of the other acts made it almost forgettable. Stylistically, SZA’s “Kill Bill,” Olivia Rodrigo’s “Vampire,” and Billie Eilish’s “What Was I Made For?” channeled the collective fury of women in music today.

But this article would be incomplete without mention of Tracy Chapman and Luke Combs’s duet of “Fast Car.” Chapman’s quiet strength and grace is well-demonstrated by the matter-of-factness with which she delivered her anthem. This

recycling of a guaranteed hit completely decontextualizes the song and strips it of its gravity.

But his respectfulness during the live performance means I can forgive him just this once.

Junior Max Gross has been listening to Chapman’s self-titled debut album with his father since he was a kid. “I was afraid that a whole generation would only like this song because of Luke Combs, even when she gets songwriting credits and everything,” he said. “It is one of her gateway songs. But his reverence toward her was honestly healing.”

The most awarded artist of the night, Phoebe Bridgers, didn’t even appear in the live broadcast except for a few crowd shots. As part of the supergroup boygenius, she won Best Alternative Music Album, Rock Song and Rock Performance for “the record,” as well as Best Pop Collaboration for her work on SZA’s “Ghost in the Machine.” Junior Kit Haggard said she was “glad it didn’t go to something on ‘Midnights.’ It was crazy that ‘Karma’ featuring Ice Spice was even thought about as an option.”

This year’s Grammys were dominated by women — and rightfully so: the only man nominated for a major award was Jon Batiste.

In 2018, Neil Portnow, former CEO of the Recording Academy, said if women wanted to be recognized as much as men in the industry, they should simply “step up.” Today, Portnow is facing sexual assault and battery allegations. Using her air time at the Grammys post-show, Bridgers said he should “rot.” Her bandmate Julien Baker solemnly noted, “That’s pretty rock and roll.”

The Recording Academy has come a long way, backpedaled a bit, and made up for their mistakes. But they still have a long way to go.

The Grammys have become a show created and funded by music lovers, yet in their reliance on numbingly simple metrics, it caters to an audience that cares more about ratings than music.

Cultural commentary by Lucy Walker Design by Georgia Andrews Photo Illustration by Elise DiPaolo

The boygenius album “the record” won three Grammys, including Best Alternative Album

Miley Cyrus: Record of the Year & Pop Solo Performance (“Flowers”)

Billie Eilish: Song of the Year (“What Was I Made For?”)

Cultural commentary by Lucy Walker Design by Georgia Andrews Photo Illustration by Elise DiPaolo

The boygenius album “the record” won three Grammys, including Best Alternative Album

Miley Cyrus: Record of the Year & Pop Solo Performance (“Flowers”)

Billie Eilish: Song of the Year (“What Was I Made For?”)

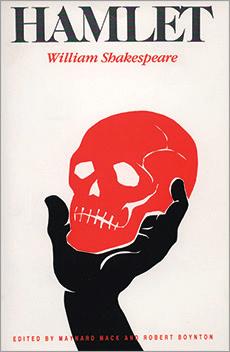

‘Ambitious’ spring musical features tap-dancing eggs, groovy Renaissance women and a litany of ‘Hamlet’ references

Story by Yutia Li SLucy Walkerweet. Stupid. Chaos.

That’s how junior Dayton Voorhees describes Johnnycake’s upcoming musical production of “Something Rotten!”

Beginning on Leap Day, a cast of dozens will take the Lowe Theater stage for four shows, including a Saturday matinee. Set in the 1590s, the musical follows a theater troupe led by Nick and Nigel Bottom (played by Dayton Voorhees and Grady McMillin) as they try to write the next big hit. Their only problem? The brothers live in the shadow of their wildly popular contemporary William Shakespeare.

While the sensitive Nigel chases after his love interest Portia (Nadiya Naehr and Eliza Dorros), Nick is desperate for a breakthrough. So he visits the soothsayer Nostradamus (Arjun Singhal), who informs him that he must write the world’s first musical in order to achieve success.

According to Voorhees, Nick is a multifaceted character. On one hand, he faces mounting pressure to support his family, yet he is also a silly person who runs around making potty jokes as he composes the musical “Omelette” — a misnomer for “Hamlet,” suggested by Nostradamus.

“Knowing when to bring out that more overwhelmed side of Nick and when to keep him completely goofy is something that I really focus on,” Voorhees said.

The two female leads are double-cast. Along with Naehr, sophomore Eliza Dorros portrays Portia — Nigel’s love interest and the daughter of a strict Puritan father (Creighton Garcia) who does not approve of her budding romance. Senior Luciana Owsley and junior Lexi Lang both play Nick’s headstrong wife Bea.

According to director Jamie Stires Hardin, the decision to double-cast the two female leads was due to “a wealth of talent at St. John’s and an abundance of females to give roles to.” Since there are four performance dates, each lead actress will star twice while playing ensemble parts on alternate nights.

When blocking a scene or practicing a number, Naehr and Dorros switch off, and when rehearsing vocal parts, they will often sing together.

“It’s definitely different to have that double interpretation of the same line and watching our differences in chemistry and interaction,” Naehr said.

After beginning in November learning music and dance choreography in the Fine Arts Annex, the cast has since moved into Lowe Theater

while Johnnycake finalizes the set. During rehearsals, actors work to prepare aspects of the show that most audience members would not notice on the VST stage.

While only about 10 members of Nick’s acting troupe appear onstage during certain scenes, up to 20 cast members are backstage singing along with them. With the wings packed full of pieces of the set and actors rushing to and fro, there is little standing room. In between scenes, crew members and ensemble actors are responsible for moving furniture and props as quickly as possible on and off stage.

Theater is incredibly freeing because there are many ways to achieve a good performance.

NADIYA NAEHR“It takes the same amount of time and effort to remember all of those things as it takes to be the lead,” Voorhees said of the stage crew.

Behind the scenes, stage managers Ally Rodriguez, Evan Gregory and Jack Faulk function as liaisons between the directors and the cast, answering questions and ensuring that rehearsals run smoothly.

After working as a stagehand in seventh grade, Rodriguez found that she enjoyed contributing behind the scenes.

“As a stage manager, you get to see the show come to life and have a really big hand in that, which is a very rewarding feeling,” Rodriguez said.

One of the stage managers typically calls the show through the half dozen headsets distributed to crew members. Stage managers control the timing of the lighting cues and sound effects — and they are the first to know when a mishap occurs.

“A lot of the time, you’re hearing ‘light cue 127, stand by, lights go.’ Or ‘sound 68, stand by, sound go.’ Or ‘What’s happening backstage?

Someone talk to me,’” Rodriguez said. “There’s only a few people hearing that in a room of maybe 600.”

Voorhees says “Something Rotten!” is the most ambitious show he has been a part of at St. John’s. While all musicals include singing, dancing and acting, one factor typically dominates a show, but Voorhees adds that all three aspects lay a solid foundation this year.

Naehr points out that “‘Newsies,’ the 2022 musical, was definitely a dance-heavy show. ‘Nice Work if You Can Get It,’ the 2023 musical, was more driven by the story. ‘Something Rotten!’ is a nice combination of both.”

Naehr, who dances with the 713 Dance Ensemble ouside of school, enjoys the freedom that theater offers.

“Ballet is very strict about the right way and the wrong way to do something,” Naehr said. “Theater is incredibly freeing because there are many ways to achieve a good performance. It’s a lot more individualistic.”

Although Stires Hardin has been putting “Something Rotten!” together since auditions in October, its humor never fails to make her laugh. For those with an inclination toward Shakespeare or musical theater, the inside jokes never stop.

Offstage, Stires Hardin recalls a rehearsal in which several members of Nick’s acting troupe were dancing through the song “God, I Hate Shakespeare.” The cast cracked up at every double entendre.

“The amount of laughter and joy that was coming out of the rehearsal room is exactly what we should be doing here,” Stires Hardin said.

Performance times for Something Rotten!! are 7 p.m. on Feb. 29 and March 1—2 in the VST, with an additional matinee at 2 p.m. on March 2.

Many a line from Hamlet appears in Something Rotten! , from iconic lamentations to niche quips only a Bard aficionado would recognize.

“Get thee to a nunnery!”

- Hamlet, to Ophelia

“Frailty, thy name is woman.”

- Hamlet, about his mother

“What a piece of work is man.”

- Hamlet, to himself

There are also numerous references to famous Broadway productions that only the theatre kids may get.

Matilda, Les Misérables, Pippin, Nice Work If You Can Get It, Cats, Cabaret, West Side Story, Oklahoma!, The Music Man, Seussical, Jesus Christ Superstar, Chicago, Guys and Dolls, A Chorus Line, Into the Woods, Phantom of the Opera, The King and I, The Lion King, The Sound of Music, Ragtime, My Fair Lady, and more!

“Frailty,

Photo byWhen preseason volleyball began, coaches were excited to use the refurbished Owsley Court. What they did not expect was dozens of Stanley tumblers leaking all over the new gym oor.

Stanleys are the popular 40-ounce water bottles formerly known as Quenchers. Students love the vibrantly colored tumblers that are capable of keeping drinks hot for seven hours or cold for even longer.

Founded in 1913 by William Stanley, the company has sold products for over 100 years, but recently the bottle’s popularity has skyrocketed, with annual revenue going from $73 million in 2019 to $750 million in 2023.

In 2022, TikTok in uencers began praising the cup for its e ective design and aesthetic features. As Stanleys went viral, the TikTok adoration translated into sales. By January, TikTok videos of Stanley cups had been viewed over a billion times.

Stanley, stating that the color is one of the reasons she enjoys bringing the bottle to school.

Others praise the Stanley’s functional design. The tumbler comes in 30- and 40-ounce options, both sporting a prominent handle for easy graband-go transport.

Because the Stanley handle restricts the bottle from tting in backpack pockets, many students carry the bottle at all times, a constant reminder to keep drinking.

“The design was annoying at rst,” sophomore Kiran Rio said. “But now that I’ve gotten used to it, it’s made me more hydrated.”

Stanleys also receive their fair share of negative coverage.

For Brantley, the Stanley is an impractical option for everyday hydration.

2018

Before Stanleys, other fashionable water bottle franchises captured the attention of students. S’wells and Hydro Flasks were two of the most popular brands over the past decade. Yeti cups also gained popularity during the late 2000s.

S’well water bottles were some of the rst to focus their marketing on fashion over function.

The stainless steel ask dominated the water bottle industry in late 2015, until the following summer when the VSCO Girl trend emerged.

The Hydro Flask, known as the “VSCO girl water bottle,” took over social media in 2016. Students loved to cover the bottles in sleeves of stickers, while others would add friendship bracelets in the making.

Junior Amanda Brantley, an avid outdoor enthusiast and Review Design Editor, appreciates the practicality of Hydro Flasks.

“They’re stainless steel and you can buy a silicone base so that they stand up after they’ve been dented,” Brantley said.

While the VSCO trend peaked in September 2019 and the Hydro Flask is still beloved by many, other bottles have gained signi cant popularity.

With increased in uencer marketing and an emphasis on hydration, the Stanley has become the hot item on campus. The insulated bottle sets itself apart from its predecessors with a mug-like style, tapered bottom and large side handle.

With bottles decked out in shades like Arctic Tundra and Rose Quartz, to limited-edition collaborations and seasonal drops, many students appreciate the Stanley’s aesthetic.

Sophomore Isabella Muñoz adores her pink

“The Stanley doesn’t seem like something people would want to deal with,” Brantley said. “The bottles are heavy, so they aren’t great for camping or cross-country runs.”

Since the Stanley straw prevents the tumbler from fully sealing, students also face problems with leaking.

During volleyball preseason, many tumblers were knocked over, threatening to damage the gym oor and leading coaches to ban the Stanleys from the gym.

“When we walked over, most of the bags and oor would be damp,” freshman Ally Hong, a sta er on The Review, said. “We would have to stop playing, grab towels and clean it up. The coaches eventually got frustrated.”

I originally got it for the popularity. But I still drink much more water out of my Stanley than I do from other bottles.

ELLIE ROSENBLATTDespite repeated incidents, many Stanley enthusiasts defend their beloved bottles.

“My Stanley will only start leaking if it’s been completely knocked over,” sophomore Ellie Rosenblatt said. “But if you pick it back up quickly, it doesn’t spill.”

The cost of popularity prohibits many prospective buyers. With a price tag of $45 dollars for the 40oz. model, the Stanley sells at a signicantly higher price than its competitors.

“They’re ridiculously expensive,” Brantley said, “so I think people are going to want to stop buying them.”

In March, concerned owners drew attention to high lead content in the bottle. A spokesperson claimed the only way to release the substance would be by damaging the circular barrier on the bottom, which is a “rare” occurrence.

Despite assurances from the company, some customers remain wary. Hydro Flask seized an opportunity to take a jab at Stanley in an Insta-

gram post that said their bottles contain no lead: “We aim for a higher standard,” the post said in allcaps. Due to their costliness and impracticality, many attribute the growing popularity of the bottles to the latest micro trend, a unique and short-lived fad that emerges through social media. Many students bought their Stanleys after seeing countless raving TikTok reviews. Similar to Hydro Flasks, once enough students purchased the bottle, the rest followed suit.

In recent months, the bottle’s popularity has led to supermarket stampedes. When limited quantities of the Stanley x Starbucks drop were released at Target stores, Stanley devotees camped outside after midnight just to get their hands on the coveted pink tumbler. Those Stanleys have been resold on eBay for upwards of 10 times their original price.

While the TikTok craze originally stemmed from the Stanley’s functionality and aesthetic, the tumbler has now capitalized on becoming a name brand. Rosenblatt thinks her purchase was a result of both.

“I originally got it for the popularity,” Rosenblatt said. “But I still drink much more water out of my Stanley than I do from other bottles.”

Many companies are attempting to emulate Stanley’s success with their own on-trend tumblers. In early 2023, Hydro Flask dropped the All-Around Travel Tumbler, which sports a handle and, much like the Stanley, tapers towards the bottom for easy transport. Even with a lower price ($35-$40), the Hydro Flask tumblers have yet to gain traction.

With numerous competitors jumping on the tumbler trend at lower price points, Stanley sales have slowed. Owalas are now poised to be the next trendy bottle.

Owala markets their bottles as easy-to-clean, with a dishwasher-safe lid and straw that allows users to choose between “sip” and “gulp” functions. Many students praise the bottle for preventing spills, keeping water cold and tting in backpack pockets.

“The Owala became a comfort item for me,” sophomore Libby Agarwal said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s the next trend.”

They’re sooo whitewashed

My parents emigrated from China in 1995. I speak uent Mandarin and take weekly Chinese lessons. Since I was 7, I have attended Chinese summer youth camp. I celebrate all the traditional Chinese holidays: Lunar New Year, Dragon Boat, Mid-Autumn and Lantern Festival.

But, because I came to St. John’s in ninth grade and wear Lululemon leggings, my former classmates claim that I am “whitewashed,” a term typically used to downplay and erase the experiences, contributions or identities of non-white communities in favor of whiteness.

Aila JiangBut whitewashing means so much more than that.

In sixth grade at my public school, I embraced the VSCO girl persona like other impressionable 11-year-olds. I carried a Kanken bag and used a tacky pink Hydro Flask. My friends and I simply followed harmless internet trends, but our classmates misread our intentions and accused us of self-hatred.

In US History classes, we often consider whitewashing when it brushes aside the accomplishments and struggles of people from other cultures.

We see it in the lm industry — white people playing non-white characters and perpetuating harmful stereotypes such as Mickey Rooney appearing in yellowface in the 1961 classic “Breakfast at Ti any’s” or Emma Stone’s portrayal of a Paci c Islander in the 2015 lm “Aloha.”

But today, as I see it, people have diminished the meaning of whitewashing. By deeming trivial choices such as getting hair highlights or wearing a certain brand of leggings, the term has been weaponized to put others down. Somehow, having a Swedish backpack (that’s made in China!) suddenly meant that I did not embrace my Chinese identity.

While people of color may use the term “whitewashed,” for white people, this is “basic.”

Not only are these assumptions false, they are both problematic.

People of color are expected to conform and assimilate to Western culture. According to the Pew Research Center, 78% of Asian Americans

have had negative experiences in which strangers have treated them as foreigners, even criticizing them for speaking a di erent language or calling them racial slurs.

People want Asian Americans to assimilate. But then, Asian Americans criticize each other for being “whitewashed,” leaving us in a perpetual state of foreignness.

People want Asian Americans to assimilate. But then, Asian Americans criticize each other for being “whitewashed,” leaving us in a perpetual state of foreigness.

Labeling fashion and beauty trends as purely Western reserves them only for white people, which only further divides minority groups.

The stereotype remains the same: non-white Americans are expected to stay di erent — they must embrace and express their culture — but only when it is convenient. I cannot be “too Asian,” but I also cannot be “too American.” I can never be one or the other.

No one should feel pressured to prove their knowledge and appreciation of their heritage in-

order to validate their own identity. Quantifying what it means to be Asian American ignores our personal, lived experiences.

Within any culture, there is a certain level of fear when it comes to being your authentic self. When I was younger, I felt embarrassed to share my Chinese middle name, and I always negotiated for Lunchables instead of homemade food to bring to school.

I have learned how to embrace my heritage, but not everyone has. Some people of color experience internalized racism. By making racist jokes about themselves, hanging out with only white friends or purposefully butchering their native languages, they downplay their racial identities.

But even labeling these people as whitewashed insinuates that it is their fault. The word is a weapon used to pit people of color against each other that does nothing to educate. The pressure to assimilate does not come solely from the non-white people, but rather the culture of white supremacy.

Stop using whitewashing for trivial fashion choices and instead focus on the type of whitewashing that actually matters. The next time you nd yourself thinking that someone is whitewashed for wearing Kendra Scott or listening to Taylor Swift, question if it comes from a place of personal insecurity or genuine concern.

insult

1. someone who is viewed as leaving behind or neglecting their culture and assimilating to a white, Western culture

2. a degradation of other people of color “that girl wearing Lululemon is so whitewashed”

Imagine a Saturday afternoon when you’re looking for something new to read. You walk into Barnes & Noble, skim the back cover of an appealing book and decide it is worth reading. So you put the book back on the shelf, pulling out your phone and promptly visiting the Amazon Bookstore. After all, you’ll get a better price online, plus free shipping right to your front door. This seemingly harmless scenario illuminates a troubling trend — the world’s dependence on Amazon.

I didn’t realize the e ects of online shopping until my local Barnes & Noble was booted from its cozy corner on Holcombe Blvd. The moment I heard of the closing, I rushed to Vanderbilt Square to stock up on murder mysteries, board games and anything else I could get my hands on, as if hoarding the store’s products could somehow keep it in business.

The 2022 Barnes & Noble closure