For the rst time in decades, freshmen are no longer required to spend their free carriers in study hall. As of Monday, Jan. 6, students are allowed to work — or not — in a place of their choosing.

Although this change may seem sudden, administrators have been planning it for years. In the past, freshmen and even sophomores were required to attend study hall when they did not have class. Then, in 2016, Class 10 students were released from their study hall obligations. Taking into account how well the sophomores responded to the freedom, faculty decided to give ninth graders the same opportunity, according to Dean of Academics Jennifer Kuhl.

As freshmen revel in their newfound liberation, teachers have also bene ted from the extra time. Before the change, most teachers were assigned to proctor either a study hall or a testing room for at least one semester. The absence of spring study halls allows teachers to meet with students and complete more work during the school day.

“It makes a lot of sense to give freshmen the privilege and the trust in the spring after they’ve spent some time here getting used to things,” history teacher Joe Wallace said.

The “freshmen ood” began on the rst day of the spring semester, and Flores Hall, study rooms and the Atrium quickly over owed with excited ninth graders.

It’s a lot better than having study halls because it’s more flexible. I actually feel much more productive now.

VIVIAN CONNELLY

Reactions vary depending on students’ grade level. Freshmen have expressed enthusiasm towards the change. They argue that the additional freedom boosts their academic performance by allowing them to meet with teachers, study where they prefer and take breaks to get food.

“It’s a lot better than having study halls because it’s more exible,” freshman Vivian Connelly said.

“I actually feel much more productive now.”

Some upperclassmen claim the new policy is unfair because they did not have free periods as freshmen.

“It de es the natural law,” Prefect Mark Vann said.

Other students began bracing for crowded hallways, chairs and nooks as freshmen invaded their favorite study spots.

“Because there are more students in here, it’s a little louder than what it was before,” Upper School librarian Suzanne Webb said. “There are more kids in the open areas, which just means it’s a bit more active.”

More students in the Academic Commons means more responsibility for the library sta .

“I’m concerned about how freshmen are going to do in terms of academics when they don’t have that dedicated time to making sure they’re getting their homework done,” Upper School assistant librarian Erica DiBella said.

Despite concerns regarding clutter, confusion and chaos, Kuhl notes that usually only about 30 freshmen are free during a given carrier.

Webb encourages ninth graders to take advantage of the Academic Commons, regardless of mumblings and grumblings.

“Don’t let the upperclassmen intimidate you,” Webb said. “It’s your space, too.”

Story by Aien Du & Brian Kim Design by Jennifer Lin

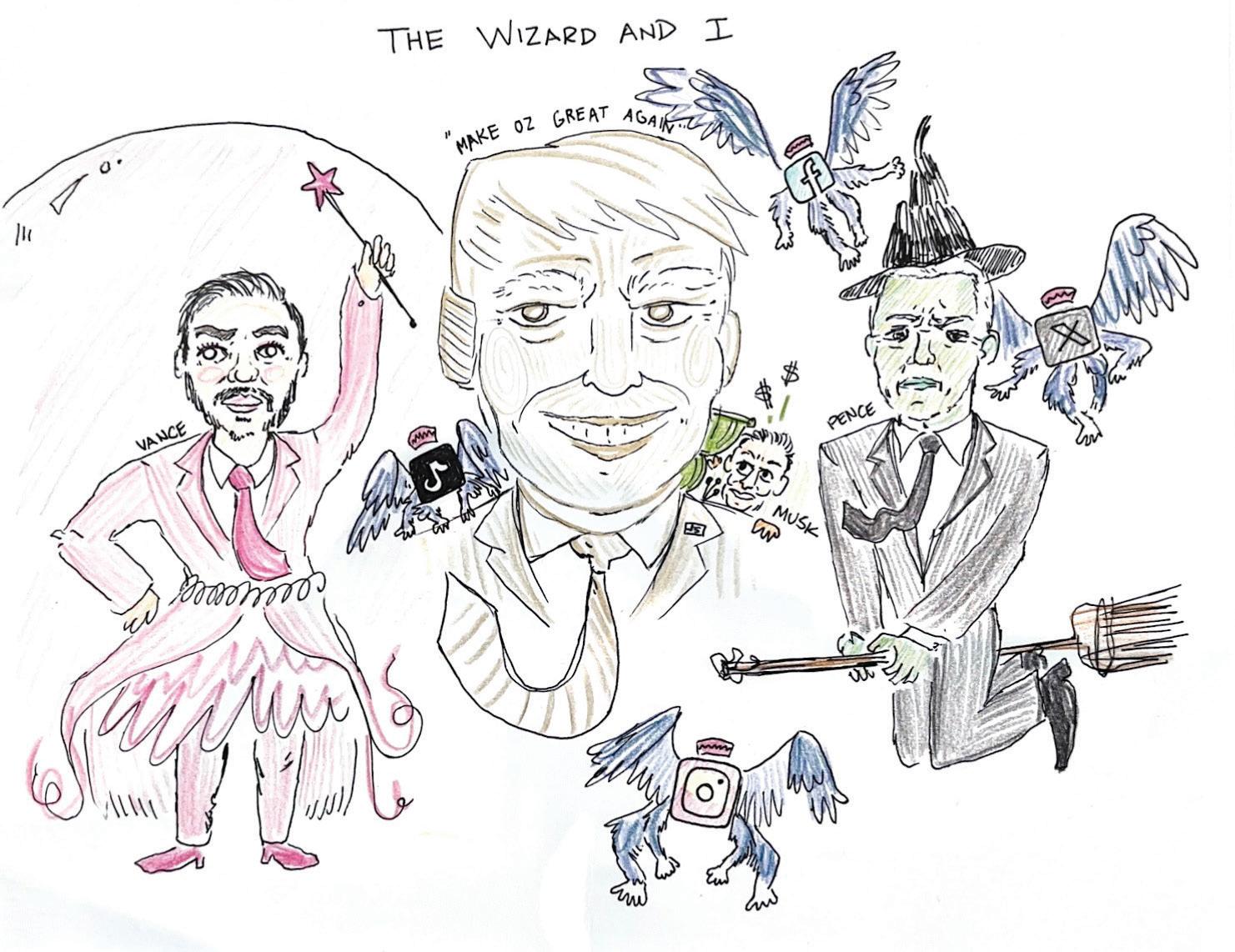

Last month, a new law aiming to eliminate alleged Chinese interference in American social media led millions of users to ock to Chinese social media.

The proposed ban on TikTok, later paused after the app had gone dark throughout the United States, caused viewers to download Xiao Hong Shu, a popular Chinese-owned lifestyle and wellness app, by the millions. By early January, Xiao Hong Shu — known as Red Note — was the No. 1 trending app for both Android and iPhone users.

“It’s so interesting that Americans moved to another Chinese app after being banned from a suspected app,” senior Emmie Kuhl said.

During President Donald Trump’s rst term, he proposed that TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, sell the app or shut it down for U.S. users. A ban was signed into law by former President Joe Biden last April. After TikTok appealed the ruling, the order was unanimously upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Government o cials cited security concerns as the reason for the ban, warning that the Chinese government might be collecting and sharing user data in ways “not well-aligned with American security interests.” According to its privacy policy, TikTok collects personal information, including location and media engagement. This policy is no di erent than those of American-owned apps such as Facebook, X or Instagram.

Red Note has continued to grow in popularity. Many new users view the transition as a way to rebel against the U.S. government, surrendering an even greater amount of data to another Chinese-owned app.

Stapleton nds this response uniquely Gen Z. “There is something about it that is so petty in a way that I enjoy,” she said.

According to Kuhl, Gen Z is already known for their distrust of authority and lack of faith in the government after years of misinformation, especially concerning the representation of other countries. Many young people perceive the attempted ban as a restriction of creative expression.

“A friend of my husband’s has been talking about how much more engagement he’s getting on Red Note,” Stapleton said. “He’ll just make dinner, and people will comment underneath, ‘Uncle, your cooking looks so great!’”

Red Note has also helped dispel myths surrounding Chinese citizens, who have historically been portrayed in American media as individuals struggling under an oppressive Communist dictatorship. Many American users have discovered that their Chinese counterparts can generally a ord homes, luxury cars and high-end products.

Chinese users have seized the opportunity to nd out whether the stories about the poor living conditions in the US are real or Chinese propaganda, even asking if the images of homelessness and run-down public transportation were AI generated.

“The government shouldn’t impose that upon people, especially when it’s silencing free speech,” said Upper School student Adella, not her real name. “The people banning TikTok are scared of it because it doesn’t bene t them and threatens their power.”

As thousands of self-proclaimed “TikTok refugees” ooded Red Note, they encountered familiar aspects of American social media, including a For You Page, a like button, a comment section and follower pro les.

“It’s as if TikTok and Instagram had a baby,” said sophomore Grace Pan, who recently downloaded Red Note.

An increasingly popular topic on Red Note is the “Letters from Li Hua.” For decades, Chinese middle and high school students have written letters during English exams to an imaginary English-speaking pen pal on behalf of “Li Hua.”

Often describing life in students’ hometowns or personal interests, these letters usually conclude, “I am looking forward to your reply.”

For years, these letters, which are addressed to Peter, Jennifer or Amanda, have gone unanswered — until now. Americans have posted on the app, penning their responses to Li Hua’s letters.

Although Red Note currently remains a viable replacement, many still question the wisdom of banning an app like TikTok.

“If there were true security concerns — and I can understand why there might be — I’d denitely want them to be laid out more clearly,” said English teacher Kristiane Stapleton. “My initial reaction was frustration because I felt as though the reasoning behind the ban was disingenuous and performative.”

The nationwide ban began at approximately 9:30 p.m. CST on Jan. 18, then ended at 11:30 a.m. on Jan. 19. American TikTok users were met with a message box stating that they could “unfortunately” no longer access the app but were reassured that the company would work with Trump, who was inaugurated the 20th, “on a solution to reinstate TikTok.”

On his rst day in o ce, Trump signed 28 executive orders, including one to postpone the TikTok ban for 75 days.

Although users can currently access TikTok,

While Red Note shares similar features with TikTok, its purpose and protocol are di erent. Those who can read the terms and conditions (written entirely in Mandarin) will nd that Red Note’s guidelines support the Communist Party of the People’s Republic of China.

China’s ruling Communist Party often censors topics such as LGBTQ+ issues and certain events in Chinese history, and many Americans have been shocked by the lesser freedom on Red Note. Moreover, some users in China nd the increasing number of Americans on the platform to be a nuisance, noting the in ux of Western-centric videos.

Despite the initial concerns, the move to Red Note has fostered an unexpected exchange of cultures. Chinese users ask Americans for help with English homework while American users request assistance with math and science. With increased interaction, users from both countries have developed more accurate views of each other.

3.4 million

Red Note gained almost 3 million U.S. users in one day, increasing their daily active users from less than 700,000 to 3.4 million.

75 days

On Jan. 19, Trump signed a 75day extension delaying the ban.

14 hours

From 9:30 p.m. on Jan. 18 until 11:30 a.m. CST on Jan. 19, TikTok went dark.

32%

In 2024, Pew Research Center found that 32% of American adults supported a ban on TikTok.

170 million

The United States currently has 170 million active TikTok users.

79-18

In April 2024, the U.S. Senate voted 79-18 in favor of legislation banning TikTok.

It’s so interesting that Americans moved to another Chinese app after being banned from a suspected app.

EMMIE KUHL

“TikTok in and of itself is not the problem, but how you use it is the problem: what you react, save, comment on curates what you see and how you use it,” Stapleton said. “I actually use TikTok quite a lot in my Body Politic class. Speci cally, when Beyoncé released her new ‘Cowboy Carter’ album, I followed a lot of music critics there.”

Like many users who see TikTok as a source of recent news, fun facts and useful tips, Stapleton downloaded the app to relate to her students.

“I primarily use TikTok for current events because that’s all my feed is right now,” Adella said.

“I read the news, but on TikTok it’s very fast and easy to see stu .”

TikTok provides a platform for millions of individuals to share their passions and interests.

Junior Claire Adkins recently started a TikTok account dedicated to informing viewers during her Spanish-learning journey on how they can achieve pro ciency.

Some viewers reached out to Adkins for advice, forming an international community of over 20,000 followers.

“I didn’t expect to receive this feedback,” Adkins said. “I just posted one video and it kind of went viral.”

Through its Creator Fund, TikTok pays content creators and businesses while allowing them to reach a wider audience.

“TikTok is a really easy way to make money,” Kuhl said, noting that many people have made a livelihood out of it.

“Society has normalized being an in uencer.”

Since the 14-hour shutdown, TikTok has since been restored, and users have been as active as usual. However, the blip revealed a much deeper issue beyond where America will get funny cat videos: How much of one freedom are Americans willing to give up for another?

From the Storied Cloisters to the altar, these couples have gone from high school to happily ever after.

When Sarah Jane Lasley and James Redding (both ’20) entered Antone’s for their rst date, the last person they expected to see was Upper School English teacher Clay Guinn (’92), who walked in to grab a takeout sandwich for lunch.

When Guinn was a student at St. John’s, he was classmates with Lasley’s parents, Mary Hamill and Stephen Lasley (both ’92). In the senior survey of their graduating yearbook, Stephen was deemed most likely to be “found with Mary.”

Guinn recognized Sarah Jane but did not initially connect the dots.

“We watched his face as he realized it was a date, and he immediately got ustered. It was so funny,” Sarah Jane said. “We were both in his class together as juniors, which was the best full circle moment.”

After dating for eight years, they got married in Asheville, North Carolina, in November.

Sarah Jane met Redding in her freshman-year biology class, taught by former science teacher Graham Hegeman. Sarah Jane often cracked “dumb jokes,” and she noticed that Redding would almost always laugh.

Jane simply “got nervous and left.”

“We then started emailing on our school accounts, which was hilarious. We transitioned to GroupMe and nally went on our rst date,” Sarah Jane said.

As teenage sweethearts, the pair partook in all the classic high school tropes. Sarah Jane wore Redding’s sweatshirt, even when it was 97 degrees, and Redding made a “promposal” in Guinn’s junior English class with a batch of home-baked treats.

“Our relationship has always been realistic — we don’t really do grand gestures, so I kept telling him he didn’t have to prompose,” Sarah Jane said. “But somehow he gured out that I did want a promposal, and he rolled up with some cupcakes.”

According to Sarah Jane, staying grounded has been integral to keeping their relationship steady, even when they attended di erent colleges.

“We don’t need to show our relationship o , but when we have the opportunities to showcase our love and celebrate each other, we still take them — even if we try to keep it pretty low-key,” Sarah Jane said.

While providing friendship and support, Redding has allowed Sarah Jane to realize her authentic self. When the couple rst met, their personalities seemed to be polar opposites — Sarah Jane was talkative; Redding was reserved.

“We both thought that we were so di erent, but what our relationship has shown is that we’re much more similar than we thought,” Sarah Jane said. “He has given me a space where I don’t have to be super loud and talkative, and I have broken him out of his shell a lot.”

We don’t need to show our relationship off, but when we have the opportunities to showcase our love and celebrate each other, we still take them.

SARAH

JANE LASLEY

“My relationship with James never would have started if I wasn’t in a class where I was comfortable and relaxed. Mr. Hegeman was actually one of the rst people we told about our engagement,” Sarah Jane said.

Since Sarah Jane was under the impression that Redding was introverted in class, she was surprised to discover he would be performing in the One Acts play later that semester. Intrigued, Sarah Jane attended the show. A few days after the performance, Sarah Jane sent Redding a congratulatory email, apologizing for not staying afterwards to talk more. Although she cited her mom as the culprit for having to leave early, Sarah

When the couple graduated St. John’s, they decided to tackle a long-distance relationship, with Sarah Jane attending Clemson University in South Carolina and Redding at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, over 600 miles away.

“Long distance was awful. I hated it, but I knew it was worth it. That’s what I kept telling myself every day,” Sarah Jane said. “I wore his varsity soccer sweatshirt all the time to let the college boys know I had a boyfriend. That was my way of keeping him with me.”

Sarah Jane also credits their relationship’s strength to mutual communication and maturity. “We put a lot of e ort into maintaining our relationship and keeping it healthy,” she said. “We are just really lucky to have each other.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the average age of marriage for Americans is around 31 years old for

men and 29 for women. Yet getting married so young should not have been a surprise to anybody who knew Sarah Jane’s parents.

Mary and Stephen Lasley dated throughout Upper School. When they graduated, Mary attended Rice University and Stephen went to Texas A&M. Technological restraints made maintaining their relationship a challenge.

“At the time, calling from College Station to Houston was more expensive than calling to New York. We really had to work hard at communication — we wrote a few letters and visited back and forth,” Mary said.

According to Mary, her relationship largely di ers from her daughter’s despite their similar romances.

“We get told a lot that our relationships must be so similar. In a way, that’s true, but the situations surrounding our relationships and the way that we ended up being together were wildly di erent.”

While Sarah Jane credits her mother with invaluable

advice navigating a high school and college relationship, she has developed some advice of her own over the years. Her mantra is “stay realistic.” Since there are many opportunities for conspicuous displays of a ection, Sarah Jane says it can be easy to get caught up in a relationship that solely “performs for other people.”

The school was such a special part of our relationship and so many of our friends today went to school there. It all just came together as a really unique and meaningful place to us.

“A big thing high schoolers fall into is wanting to t in socially and keep up with everybody, and if that is how you act in your relationship, it’s probably not going to go very far,” Sarah Jane said. A relationship does not have to “look, feel, sound or be” any certain way.

Now that they have been married for three months, the Reddings enjoy being homebodies — they consider their couch the “third member” of their relationship. In their Houston apartment, they spend their free time watching reality TV and trying out new restaurants and recipes. They still enjoy the little moments, like running errands, listening to Chappell Roan and talking about their days.

“The more situations that I’m able to see him in, the more I’m reminded of why I want to be with him in the rst place,” Sarah Jane said. “I’m never going to turn down the opportunity to just hang out with him.”

Despite the many comments regarding their youth, Sarah Jane says the age you meet your partner “doesn’t matter.”

“What matters more is your emotional maturity, your self-awareness, your ability to communicate and whether or not you just like being around that person.”

Hannah Je ers and Evan Davis (both ‘07) got married at St. John’s in October 2017, holding their ceremony by the Upper School carpool lane and their reception in Flores Hall. Although they initially considered traditional venues from California to Houston, when they learned St. John’s was an option, the search was over.

“We just loved the idea. The School was such a special part of our relationship, and so many of our friends today went to school there,” Je ers said. “It all just came together as a really unique and meaningful place to us.”

When they announced their decision, a few friends were still skeptical.

liam and Mary while Davis attended the University of Virginia. Despite the challenges of maintaining contact while living two hours apart, Je ers believes the college experience only strengthened their relationship.

“Long–distance helped us become our own people and develop interests that ended up being largely compatible,” Je ers said. “I’m glad we got a chance to be our own people and explore life on our own.”

The pair lives in Houston and are parents to two kids. Some of Hannah’s favorite memories with the kids include fun trips and activities, yet she still stresses how important it is to relax one–on–one with Evan.

“We have been lucky to nd ways to enjoy things outside of the kids and carve out that time for ourselves,” Je ers said.

When Upper School math teacher Caroline Kerr (‘01) was in high school, she was best friends with Lauren Lusk (‘02). Kerr would even join Lauren’s family on vacation, yet she did not spend much time with Lauren’s brother Andy (‘99).

“When we told them that we were getting married in a high school cafeteria, they were so surprised,” Je ers said.

“But St. John’s exceeded their expectations.”

Je ers and Davis knew of each other as underclassmen but did not o cially meet until junior year in their Precalculus class.

While they were in similar friend groups, the pair’s rst o cial date was junior prom.

“Prom was the rst time we hung out outside of a group or in the classroom setting – but after Evan took me to the movies to see ‘The Da Vinci Code,’ we o cially started dating,” Je ers said.

“Andy was always the cool older boy, and I was the nerdy younger girl,” Kerr said. “He thought he was too cool for me, but it turns out, he wasn’t too cool after all.”

Je ers and Davis also shared a senior elective taught by history teacher Gara Johnson-West, who often threatened to separate them.

“She didn’t want us making goo-goo eyes at each other, but she did let us sit next to each other, which was very nice of her,” Je ers said. Years later, at their wedding, Johnson-West was in attendance.

After graduating, Je ers attended the College of Wil-

After graduating from Vanderbilt, Kerr went to graduate school at New York University, where she kept in touch with Lauren. Once Andy moved to SoHo in 2008, they began dating six months later. At rst, Kerr was concerned that their relationship might interfere with her and Lauren’s friendship.

When Kerr broke the news to Lauren, her friend replied, “Why would I be mad?” Kerr observes that when you marry someone whose sister is your best friend, you get to spend time together.

They have been married for 12 years and have three children, ranging from 4 to 10 years old, and multiple pets, including a pig named Zelda.

As the couple navigates parenting and family life, Kerr emphasizes the importance of maintaining close contact with Lauren and her other relatives.

“The family that we’ve created is very important to us,” Kerr said. “It’s our glue.”

In 2023, Topher McCord traveled to Krueger National Park in South Africa. His classmate’s sibling commissioned him to paint a series of images for their wedding invitations.

“I was excited and sort of scared about it because it was a wedding — a big occasion,” McCord said, “I wanted the couple to like it, but I’d brought limited supplies.” He struggled to nd water to paint with and ended up using a nearby creek as his source of water. Using only colored pencils and creek water, McCord created the main photo of the soon-to-be married couple.

“It ended up working out, and I took a lot of color scheme inspiration from being there,” McCord said.

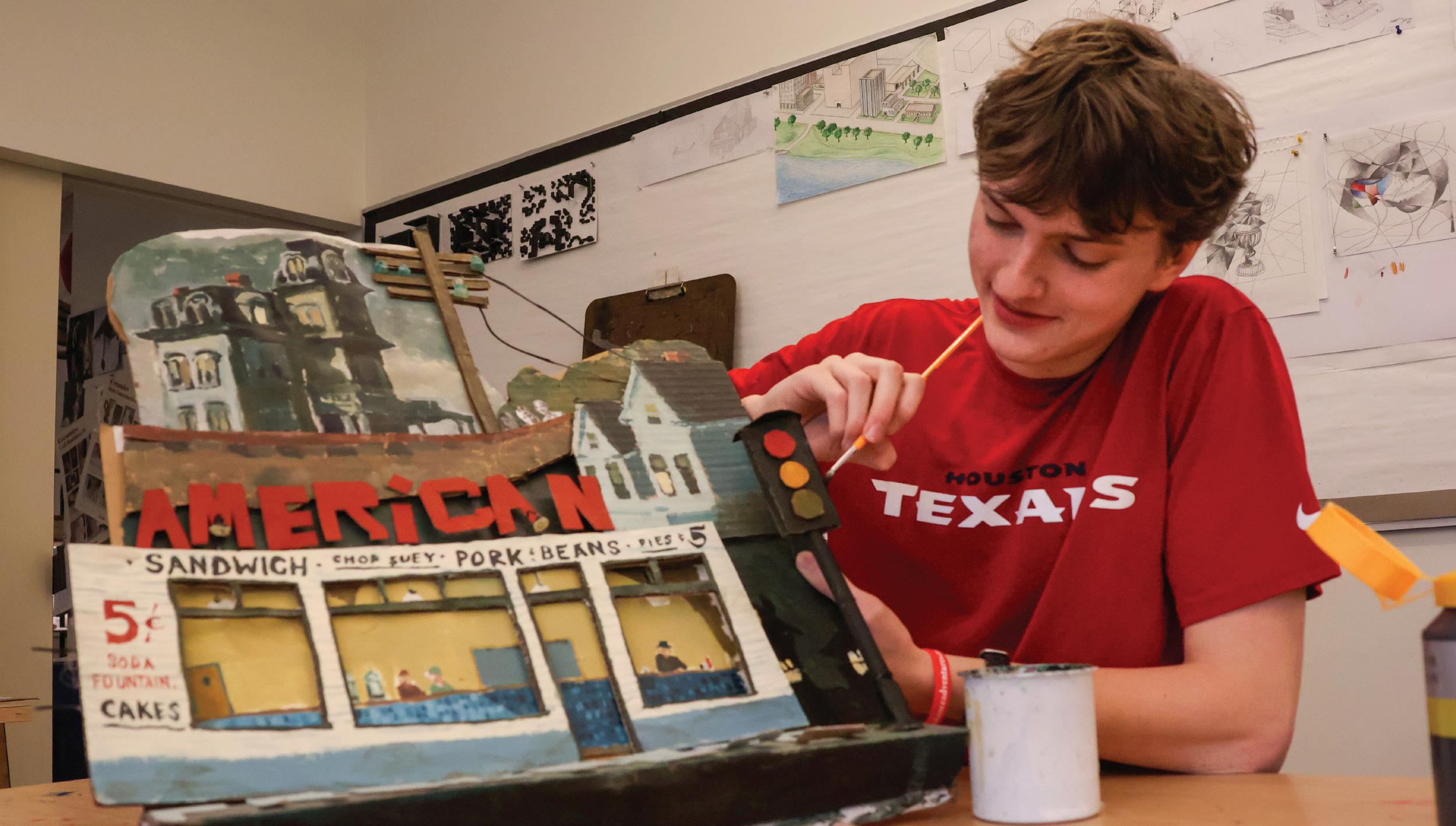

Other than a few summer programs and mixed classes, junior Topher McCord’s journey has been mainly self-guided.

“I never really had any formal art lessons,” McCord said. “It’s just been a passion of mine.”

Junior Finnian Owsley has been friends with Topher since preschool. She says art has always come “way too naturally” to McCord.

“In Middle School, he would be bored in class and draw on a dry-erase board. It would be the most insane thing I’ve ever seen, and he did it in two minutes and then just erased it,” Owsley said. McCord has taken full advantage of the Upper School Fine Arts program. He started in architecture, where “he really shined,” according to his teacher, Daniel Havel.

“He came in and did projects over the top,” Havel said. “I got to know him very well through architecture because he was hooked from Day One.”

McCord appreciates Havel’s approach to the class, where he collaborated with other students and built a strong artistic foundation.

Last year, McCord took 2D Art in the fall and Studio Art in the spring, which, according to McCord, is the “art class nal boss.”

While teaching McCord, Havel learned to instruct students that intrinsically have the gift for art. “I tell my students to be curious, explore and

build. Feeding him harder and harder things gave me a challenge,” Havel said. He’s shown me how to push students further in their abilities.”

McCord has taken the maximum amount of class o ered for Fine Arts, but he wants to experiment with ceramics and learn how to use the pottery wheel.

While biking around Houston, McCord observes past building styles in older neighborhoods and modern forms of sustainable architecture. He also explores abandoned buildings, even investigating one of the oldest prisons in Texas, the Central Unit in Sugar Land and a network of tunnels under Rice University this past summer.

He’s shown me how to push students further in their abilities.

DAN HAVEL

“I like exploring all these weird little places that we don’t really know about,” McCord said.

“He’s very adventurous and always up to something,” said Owsley, who has accompanied McCord on his bike trips around Houston. “He never sits around, and he’s always using his imagination and creativity.”

Yet, after breaking his arm last year during one of his rides, McCord decided to put his biking excursions on hold and start looking for inspiration elsewhere

McCord remembers stumbling upon his grandparents’ vintage camera from the 1960s while cleaning out their attic in 2020. After discovering the lm was still functional, he started capturing images of everyday life in Houston and posting them on his Instagram account.

“There were some photographers in the ‘70s like William Eggleston and Stephen Shore who took pictures of scenes of everyday life that people wouldn’t really look at,” McCord said. “So I try to take that approach with my photography, too, nding extraordinary in the ordinary with street scenes and stu about Houston.”

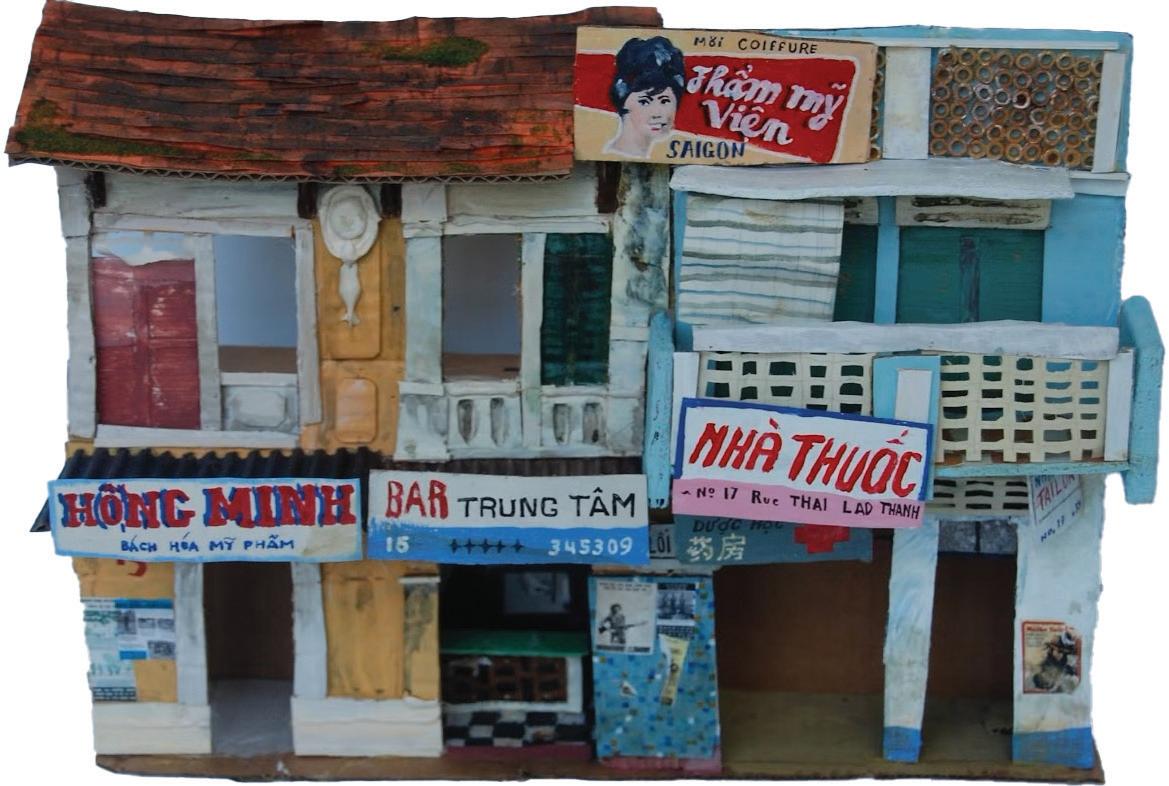

Recently, McCord has been weaving tapestries inspired by Anni Albers, who ran the textile program at Black Mountain College, using woodworking techniques and creating 3D collages and dioramas that can take up to a month to build. He likes to incorporate architectural aspects into his designs.

“Those are some of my coolest things that people tend to like the most,” McCord said. Since starting his website in 2022, McCord has been o ering architectural commisions in pain, ink or pencil of people’s houses on his website.

“Art is one of those things that everyone appreciates,” McCord said, “It’s a responsibility and an opportunity; the fact that you can do what you

like, bring some visibility to things overlooked or unnoticed and make a little money from it seems like a good option.”

McCord’s work has been featured at pop-up art shows around Houston like the new Seven Sisters gallery and the Koelsch Gallery in Montrose.

“It’s just a great way to network with artists and get your voice out there,” McCord said.

McCord is also a member of the teen program at the Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston (CAMH), where he curates and plans youth programming alongside other high schoolers from the Houston area. He is currently working on a framed panorama about living in a pre-mass consumption world, depicting how people used to entertain themselves. He is planning an exhibition at the CAMH about di erent types of media that people, especially Gen Z, consume.

McCord has been frequently recognized for his artwork, a national American Visions gold medal in 2024. He submitted a pastoral scene with 3D aspects inspired by the work of Edward Hopper. His piece, “American Progress,” is centered around ideas of “leaving the old and going into the new.”

That same year, McCord won third place in the Michael G. Meyers Architecture Competition, which emphasizes problem-solving and graphic presentation skills through architecture. The contestants were challenged with designing an educational lab in the shape of one of the letters from the acronym STEAM for a real world project.

“I teach my students pretty hands-on things, and these guys were doing computer programming and illustrations,” Havel said. “For him to stick with it — even though he might be an underdog —and then for him to get third place was pretty gratifying for me.”

McCord met frequently with di erent architects before the competition to plan out his idea, a multi-use art based library. While most contestants incorporated digital elements into their pieces, McCord created his whole project with tracing paper.

McCord plans to pursue art in college, hoping to go into the design world through either industrial or furniture design.

“He’s got the rectitude,” Havel said, “and he wants to really explore di erent ways of making art. He’s talented and can pump out a pretty fantastic piece of artwork overnight, which blows us all away.”

Sieler demands excellence in the field and the recording studio

Bianca Sieler is not one to throw away her shot. Whether she is in the discus ring or at the shooting range, the multi-sport star strives for excellence in her athletic pursuits.

The junior joined the Lone Star Select Shooting Team in seventh grade, and over the past ve years, she has moved up four ranks (or “classes”) and is currently only two classes away from reaching Masterclass, the highest level in shooting. She has competed in state and national competitions.

“It’s an odd hobby to have,” Sieler said, “but it’s really fun.”

Sieler’s favorite shooting event is 5-Stand, which simulates real-life game hunting. Participants shoot at sporting clays known as “birds” that soar over the course. Focus and adaptability are key.

“During competitions, everyone is friendly but also locked in because shooting is a very, very mental game,” she said.

At school, Sieler is a track athlete who has placed second in discus and shotput at SPC. Although she also ran sprints in middle school, she has focused exclusively on discus and shotput in high school. Track and eld captain Jackie Chapman does weight training with Sieler.

“Your o -season job is to get stronger,” Chapman said. “You don’t have to do cardio, but you have to lift as heavy as you possibly can.”

Sieler does both.

“When it’s 103 degrees, she’ll be outside, running three miles,” junior Claire Connelly said.

“She puts in way more time than anybody else.”

During the track season, Sieler bonds further with her teammates by hosting jam sessions on

the eld after practice on Fridays. She brings her guitar and sings, showcasing her original songs. Chapman, Connelly and senior Cate Adams frequently attend these sessions.

Sieler has released six self-produced singles on Spotify and Apple Music, most recently the track “Letter from Me to You” on October 23. Along with mini-concerts on Skip Lee, she performs her original songs frequently at Chapel, including her most-streamed song, “Ignite.”

The idea to launch her own Spotify platform resulted from a spontaneous song-making session during a study break in which she wrote a song in 45 minutes. That song, “Fade,” remains her fastest-written song.

“I don’t know where it came from,” Sieler recalls. “I haven’t been able to do anything like that since.”

Sieler aims to create songs that sound like a “random excursion.” She molds her work around her feelings, ranging from annoyance to sadness to hopefulness. Whenever she checks her streaming analytics on Apple Music and discovers that people are listening to her music, especially people in other countries, she feels an immense sense of pride.

“I’ve seen listeners in Nigeria, in the Netherlands, in Poland and in Brazil,” she said. “Usually it’s only one stream, but that one stream is there.”

On her fourth single, “Leave Me Alone,” Sieler collaborated with Cate Adams, whose voice, she felt, t her vision for the song. Though Adams admits she was nervous to sing with Sieler, she became comfortable.

“I love singing, but I’m working on my stage fright,” Adams said. “She is so easy to sing and have fun with. She’s not judgmental at all and

“It’s really fun to play around and sing without following certain notes or sheet music,” Adams said. always uplifts me.” Concert. too.”

Sieler began her musical journey with Les Chanteuses solely for a ne arts credit freshman year, but she ended up loving the choir program so much that she kept with it — all the way to Kantorei. This year she sang a solo during “Puncha Puncha,” a song performed at the Fall Choral

“There might be a misconception that all solos go to seniors, but that’s not true — she gave the best audition, and that’s who we went with,” said choir director Scott Bonasso. “It’s good for other students to see that a junior got a highlighted solo, because that means they can,

it’s a sacri ce that I’m willing to make to do the things that I love,” she said.

Bonasso said he is impressed by Sieler’s e ort and attitude in both of her choirs, regardless of how packed her day is. “She’s perpetually enthusiastic and unfailingly positive, and everyone feeds o of it,” he said, “In choir, the singers around her can’t have a down day because she’s just always excited and ready to go.”

Sieler came to St. John’s from Trafton Academy in ninth grade. As one of the rst admitted in many years, she was worried she would be somewhat unprepared. She nds inspiration from her father, whom she describes as an “underdog in every way, shape and form.” As the rst member of his family to attend college, her father would work during the day and take classes at night. Her mother emigrated from Durango, Mexico, and faced challenges of gaining citizenship and overcoming language barriers.

“Both of their backgrounds have made me appreciate hard work and never giving up, even when it gets hard,” Sieler said. “They work so hard for everything to give me opportunities, and I don’t want to waste that. I won’t throw that away.”

Sieler channels her determination into hyping up her friends and teammates. Chapman gives Sieler credit for helping her be less timid around others.

“I only really talked to the throwing coach during past track events because I was shy,” Chapman said. “Now it’s a lot easier for me because of her.”

Connelly turns to Sieler for reassurance during a performance or a meet. “She’s always the one who I lean on to give me some of her con dence,” she said.

Though Sieler’s childhood dream was to be a professional singer, her latest goal is to produce an album. Currently, her songs only feature voice and guitar, but she wants to incorporate di erent styles into future works.

“I want to build. I want to have drums or a violin,” she said. “I want to be pressing buttons in a studio and recording intentional lyrics and sounds.”

Sieler sings in both Chorale and Kantorei. Though they are time-consuming, she does not consider them a burden. “I have my fair share of mornings when I’m up at 4:00 a.m. nishing homework, but it’s ne because

consider them a burden. “I have my fair share of mornings when I’m up at

With the track season underway, Sieler plans to continue giving mini-concerts. “Whoever just feels like attending those can. She’s a really inclusive person,” Chapman said. “And she takes requests.”

over $10,000 a month — $38,000 adjusted for in ation.

Due to the sensitive nature of this story, we have changed the names of some interviewees to protect their privacy. To avoid speculation, we have also chosen to omit certain identifying information, including students’ graduating class and other dates.

When Noah* was in his early 20s, he watched his cousin get kidnapped — in fact, he helped.

His younger cousin, the family’s “problem child,” had been drinking and sneaking out. After she broke into a neighbor’s house and slept in their bed with her boyfriend overnight, her mother had enough. Noah’s aunt enlisted him to aid in bringing her daughter to a pickup point for a therapeutic wilderness program — “she trusts you,” she said.

“My aunt was a pretty smart cookie, but she bought into all this stu ,” said Noah, who is now in his 50s and has a child at St. John’s. “They pretty much convinced her that if she didn’t do anything, she was going to lose her daughter.”

The TTI is largely for-pro t and, according to the American Bar Association, receives $23 billion annually in public funding. Resolution Ranch Academy, a “therapeutic ranch for at-risk boys” in Cameron, Texas, costs $7,500 a month. BlueFire Wilderness Therapy, an Idaho-based wilderness therapy program, costs $21,000. The facilities actually covered by insurance make about 90 percent of their revenue from Medicaid and other federal programs.

At Challenger Camp, Cartisano implemented abusive militaristic conditions and forced marches. Olsen condemned Cartisano’s rebranding and tried to restore the industry’s image, but it was too late.

The rst reported death occurred in May 1990 at Summit Quest, a wilderness camp in St. George, Utah, when 15-yearold Michelle Sutton collapsed on a hike. Although sta claimed Sutton was given food and water, an autopsy revealed that she died from dehydration and heat exposure.

cookie, but she bought into all this stuff. They pretty much convinced her that if she didn’t do anything, she was going to lose her daughter.

Under the guise of a trip to Las Vegas, Noah’s aunt brought him and her daughter to Nevada. When the plane touched down, they met a friendly couple on the tarmac who told Noah’s cousin about a special place that could help her.

patient receives at least 20 hours of treatment weekly. Unlike IOPs and PHPs, inpatient programs like Menninger’s keep patients 24/7. Teams of therapists, psychiatrists and nurses are responsible for patient care, ensuring they eat, take medication and stay active.

Ari, an SJS student at the time, described Menninger as a “cross between juvie and an old folk’s home.” At intake, patients are required to undress and submit to a full search for anything that could harm themselves or others. Patients are not allowed to keep their phones and could only contact people on the outside with sta approval.

“I was petri ed. My parents had promised they weren’t going to do this,” Ari said. “Then they were doing it, and they said it was only going to be three weeks, and at the time, three weeks seemed like the end of the world.”

Those three weeks turned into three months.

A month later, a 16-year-old girl from Florida died from heat exhaustion during a hike with Challenger. Between 2000 and 2015, The New York Times estimates at least 86 teens lost their lives while in the care of TTI facilities.

NOAH

Her confusion soon turned into fear. They walked into a parking garage, where two men physically restrained Noah’s cousin and forced her into a white van. As it drove o , Noah’s aunt broke down.

“She just lost it. She started bawling and said she wasn’t sure if she’d done the right thing,” Noah recalled. “She had just given her child over to some stranger.”

Noah’s cousin was one of thousands a ected by what experts call the “Troubled Teen Industry.” The TTI includes a mix of therapeutic boarding schools, residential treatment centers and reformatory religious academies. These establishments claim to help youth combat behavioral issues, mental health problems, eating disorders and, in some cases, stamp out “deviant” sexual or gender identities. Wilderness schools in particular have drawn media attention for incidents of abuse and neglect. Recent exposés, including the Net ix limited series “Hell Camp” (2023) and “The Program” (2024), share stories of wilderness school survivors and the physical, psychological and sexual trauma they su ered at these facilities.

Even after devastating lawsuits, many companies still operate under di erent names. Teenagers can be recommended for these programs by their local government or school, although in some cases, like with Noah’s cousin, program sta receive parental consent to essentially kidnap their children. Several states have passed legislation over the past ve years to increase regulation of residential treatment facilities. New laws in Oregon prohibit the use of handcu s during transportation, and Utah has made inspections more frequent and thorough.

Utah’s natural beauty and strong parental rights laws make it a hotspot for the Troubled Teen Industry. Since 2015, over 20,000 youth have been sent to treatment facilities in Utah, contributing millions of dollars to the state economy according to a research brief from the University of Utah.

Utah’s draw is unsurprising considering the roots of the TTI. The industry got its start in the 1960s at Brigham Young University when professor Larry Dean Olsen started teaching wilderness survival skills to his students. When BYU deans noticed better behavior and grades from participants, they collaborated with Olsen to design a course that allowed failing students a chance at readmission if they completed a month-long backpacking trip through the Robbers Roost canyon. In 1968, Olsen established the rst wilderness therapy programs, charging $500 for a 30-day outing.

BYU alumnus Steve Cartisano took the industry to a new level in the late 1980s with the Challenger Camp, charging

A 2021 report by the National Disability Rights Network published numerous cases of abuse in wilderness camps. Broken bones, malnutrition, sexual abuse and forced isolation were widespread, with medication sometimes being used for “chemical restraint” rather than treatment. The psychotherapy o ered at these programs is not backed by science and lacks trust-based dynamics, and cost-saving measures are often prioritized at the expense of the patients.

“Trust is critical to a therapeutic alliance. I might be able to verbalize how I’m feeling and I might be willing to talk to you, but if I can’t trust you, then it doesn’t even matter,” Upper School Psychology teacher Amy Malin said. When industries are deregulated, she added, “you open the door to companies who will put pro t over humanity.”

A 2008 report by the United States Government Accountability O ce reveals that, of eight closed cases resulting in a death in these private programs, three involved prominent physical restraints: one was restrained over 250 times in four years and illegally held against his will after his 18th birthday; another died from a chest infection and had dozens of blunt-force injuries; the third, a boy with asthma, was held face-down for ten minutes by three sta members and died from an abnormal heartbeat.

Part of the GAO’s investigation involved posing undercover as parents of ctitious troubled teens. They found examples of deceptive marketing and suggestions that parents commit tax fraud to a ord the program.

We took a similar approach while researching for this article. Our imaginary child was a 16-year-old boy with ADHD named Ryan who had once enjoyed soccer and Scouting but now enjoyed drugs. When we called BlueFire Wilderness Therapy, we were told parents receive a “super bill” at the end of their child’s stay with charges including individual, group and equine therapy.

We tried multiple times to reach out to several other facilities. Most representatives promised they would call back or put writers in touch with administrators — they did not.

No matter how bad things got, Ari’s parents promised they would never send her away. Her ongoing mental health struggles became more pronounced throughout middle school, and that promise proved dicult to keep when Ari’s father found her on the second- oor balcony preparing to jump.

This sent Ari’s parents scrambling. About a week later, they sat her down and told her they were considering an intensive outpatient program. Within ten days, Ari was checked into Houston’s Menninger Clinic.

There are three main levels of mental health treatment: intensive outpatient programs, partial hospitalization programs and inpatient programs. In an IOP, patients receive regularly-scheduled therapy sessions — six hours of treatment per week for adolescents and nine for adults. A PHP

Several days into her stay, Ari was called into a family therapy session. Suddenly, another of her mom and dad’s “nevers” was coming true — her parents were divorcing.

“That’s when everything fell apart.”

When a doctor asked how she would cope with the divorce if she were at home, Ari said she might consider harming herself. The doctor replied, “That is all I needed to hear.”

Menninger kept Ari for ve more weeks before transferring her to Evolve in Mount Helix, California, where she stayed for an additional ve weeks. While she was away, Ari missed out on her middle school graduation and other milestones.

“Everyone was like, ‘you need to know the quadratic formula,’ and I just wasn’t there for that,” she said. “It was a very weird thing to xate on, but it was what my brain was attached to: Everybody did all these things and you missed out because you needed help.”

In mental health facilities, there is a lot of taboo surrounding “harm,” or as Ari calls it, “the H-Word.” In their e ort to prevent self-harm at all costs, institutions sometimes make patients feel extremely isolated. To Ari, notifying a sta member of self-harming urges felt like ipping a switch.

“If you don’t spend time and really sit in that emotional distress with somebody, then that next level of care could feel like, ‘I just got placed here, it was my fault,’” said Upper School counselor Jake Davis. “It could very well be the right decision for somebody, but there’s a way to do that that respects the person’s dignity.

I would think that a good mental health clinician should assess needs more fully before making that kind of decision.”

I was petrified. My had promised they going to do this. Then were doing it, and it was only going to weeks, and at the weeks seemed end of the world.

SJS’s other Upper School Counselor, Claire Wisdom, worked as a therapist at Menninger around the same time Ari was there. She emphasizes that treatment is a collective e ort.

“It was never just me making a decision for a person’s care,” Wisdom said. “I might see somebody that’s really struggling at this level and say to my team that they seem like they need more support, but that would always include a conversation with that client.”

Wisdom recognizes how di cult it is for people to open up. In some cases, like Ari’s, seeking help can immediately take a situation from bad to worse, but getting committed isn’t the only possible outcome.

“There are a lot of ways to approach those feelings that wouldn’t necessarily lead straight to hospitalization,” Wisdom said. “I want to be the encouraging therapist that says, ‘I hear you.’”

According to Davis and research, students at high-achieving schools like SJS have a higher risk of anxiety and depression. A recent survey of Upper School students revealed that the top source of stress was not “achievement culture,” but parental pressure. High performance expectations — whether self-imposed, parent-driven or in uenced by the broader community — were reported as a contributing factor to well-being and a primary source of student stress. In response to the data, the Counseling

department has organized workshops focused on healthy coping rather than substances, as well as monthly parent wellness co ees, but these initiatives are ine ective if parents don’t show up.

Ultimately, SJS counselors and TTI survivors agree that parents need to listen to their children. Parents want the best for their children, but those who pin their hopes on “experts,” especially in uncomfortable or specialized areas, risk endangering their relationship and the child’s wellbeing.

grant made it di cult for them to connect.

Then, one summer day when Sydney was 11, her father told her to pack her bags. She was going somewhere for a week. Her destination ended up being a wilderness camp in rural Lithuania.

thinking that somebody with the appearance of authority is promising everything they want.

Recent child abuse scandals, including executive Dan Schneider’s reign of terror at Nickelodeon and trainer Larry Nassar’s sexual manipulation of girls on the United States Olympic Gymnastics team, are further evidence that powerful people should not automatically be trusted with vulnerable kids.

appearance of authority is promising everything they want.

know what they’re doing,” Malin said. “We have to be careful not to judge the action of the parent without rst understanding where they’re coming from, since these things are

guarantee safety. Placing all types of at-risk teens in one facility does not take into account the danger some individuals may pose to others.

Ari remembers one boy at Menninger who forced another patient into her room and sexually assaulted her. Rumors also circulated of another Houston-area patient hanging that was supposed to keep us safe.”

Evolve, Ari says, was more oppressive. During her stay, one patient ran away. She’s not sure if he was ever found, but no

tients from bringing up past treatment programs, politics, religion or anything potentially triggering.

Sydney only stayed for a week, but some were at the camp much longer. The facility held children from China, Latvia and Estonia, aged 8 to 16, who had been sent for a variety of reasons — some were dealing with alcohol, smoking and addiction, but there were also teenagers who weren’t there for any discernible reason. “They seemed normal enough to me,” Sydney said.

Sydney had strong familial ties to Lithuania and visited every summer, but the camp still struck her as “very Soviet.” Amenities were intentionally sparse — they had cabins but took turns sleeping outside. Campers went on daily four-hour hikes to a lake where they could shower or swim before hiking back.

across,” she said. “I continued to act out a little bit, but not as much as before. I lost a little trust in him, but he also lost a lot of trust in me. Our relationship was de nitely strained.”

Unlike Sydney, Noah’s cousin was in her program for over a year, and her relationship with her family was irreparably damaged. It has been over a decade since she last spoke to any of them, including her mother and Noah.

Despite some of the discomfort Ari experienced at Menninger, she appreciates her time there. The people were “extraordinarily kind,” and she remains friends with some of them.

“It was de nitely a good experience because I don’t know what would’ve happened had I not gone,” Ari admitted. “I’ve just kind of accepted that it was a part of my life. It was what I needed at the time.”

Regulated treatment facilities o er more of a safety net than wilderness schools, but to stop the abuse, state and local governments need to accept their responsibility “loco parentis,” a legal term meaning “in place of a parent.”

Specially-trained therapeutic foster homes also serve as an alternative to residential therapy programs.

My parents they weren’t

One kid shut o the water — “I don’t know why, he must have just been angry” — so sta had to source potable water from a nearby village.

The teens also rotated shifts foraging for their own dinner. Groups took turns looking for wild mushrooms and berries without knowing what was edible and what was poisonous. If they could not nd anything, they did not eat.

“My dad doesn’t understand the way I think and how I interact with things because of the way I grew up,” Sydney said.

“This was his way of saying, ‘This is what it was like when I was a kid. You need to have that hard life.’”

When Sydney returned, she said their relationship was more tense than before, but in some ways, more understanding.

“Honestly, I think he got his point

A rewards system incentivizing good behavior is common the ranks, the more privileges you receive. At Evolve, Level a room alone except when showering. At Level Three, you could bring a razor in the bathroom to shave for a short period of time. By Level Five, you could go on brief, supervised excursions.

Then they they said to be three time, three like the world.

One meant you couldn’t be in a

until, at the end of the seminar, he broke down crying and let everyone hug him.

“If you didn’t give into this stu , they said you were holding back,” Noah said. “You have to admit to something, and if you don’t, it’s your fault for not letting go.”

The TTI also organizes activities to comfort families of troubled teens. Noah remembers a seminar held by his cousin’s wilderness camp in a “rinky-dink ballroom in Conroe” where he participated in exercises meant to uncover and release past trauma. One participant, whom Noah suspects might have been a plant, made a big show of not buying into the activities not their Ridge pent-

Participants also released their anger by beating their chairs with makeshift clubs made out of towels wrapped in duct tape — a practice remembered by survivors of Ivy Ridge Academy in “The Program” — and verbalizing pentup frustrations with their parents. Organizers turned o all the lights while everyone knelt in front of the chairs screaming, “I hate you, Mom!” and “Dad, go to hell!”

In any case, wilderness therapy schools should never have be an option. Experts recommend desperate parents pursue options based in trust and community — and implore them to remember that every troubled teen is still just a kid.

“I didn’t make a stink about it, but man, it was weird,”

A week before Houston teenager Sydney was sent away, she got into a ght with her father, left her apartment and slept over at her friend’s house without telling him. This was not their rst ght, nor the rst time Sydney had stormed out. Since her parents’ divorce, Sydney’s relationship with her father had grown more antagonistic, and their di erences as an American teen

“I didn’t make a stink about it, but man, it was weird,” Noah said. week left and a Soviet Lithuanian immi-

Revitalized

With 50 seconds left, sophomore Evie Laskaris knew that one mistake would cost her the game. After four hours, she slowly gained a winning position against her erce opponent who had a chess rating of over 2000. With mere seconds on the clock, Laskaris reached a checkmate with a rook and bishop, raising her chess rating by 100 points and forging her path toward a national title.

Laskaris won this match over Labor Day Weekend playing for the chess team, which placed rst at that tournament overall. She has been in the Top 100 U.S. female chess players in her age group since she was nine and currently ranks 27th, holding a 1661 chess rating with the US Chess Federation. Chess ratings range from 0 to 3000 and include the United States, international and online divisions.

When Laskaris started at St. John’s in ninth grade, most of the chess team played individually or online, developing their skills on their own. The club’s popularity wavered as players barely participated or left. This year, however, with support of faculty sponsor Amy Malin, the group started competing in tournaments across Houston as a team.

As a club leader, Laskaris planned more in-person meetings so the team could meet every two weeks.

Freshman Luca Chang joined the team this year — his rst time playing competitively for a school team — and said he appreciates the social aspect of the team.

“I really enjoy playing with my friends, especially with people who have the same love for the game as I do,” Chang said.

The team is composed mostly of underclassmen, led by Laskaris and sophomore Ronak Hiwale, who each hold chess ratings of over 1600. Hiwale started his career at just three years old, and he played frequently throughout middle school. He

has traveled to Las Vegas, California, Philadelphia and Chicago during free weekends to compete in state and national tournaments, earning multiple awards such as the title of National Master, which requires a chess rating of over 2200, this past October. He now holds a 2208 in the United States, a 2093 internationally and a 2680 online.

One reason I love chess is because it doesn’t discriminate. Chess doesn’t care about your gender, your size or your age.

EVIE LASKARIS

Most players with elite ratings like Hiwale and Laskaris are in their twenties or older, which, according to the captains, can be intimidating. Yet they agree that it is better to challenge themselves than play down.

“I play against really strong players, so it’s always a good feeling when I win because of my hard work,” Hiwale said. “But when I do lose, it’s a great thing to learn from even if I do feel emotional at the time.”

An aggressive player, Hiwale opens his matches

with the King’s Indian Attack, a strategy in which the player moves a knight and a pawn, making room for more pieces to become threats. Laskaris takes a more restrained approach and opens with the Giuoco Piano, protecting her king and controlling the center of the board.

While Hiwale and Laskaris di er in their tactics, both are passionate about chess and believe it is “more than just a game.”

“It has taught me resilience, determination, how to behave under pressure and how to strategize,” Laskaris said. “One reason I love chess is because it doesn’t discriminate. Chess doesn’t care about your gender, your size or your age.”

Since Laskaris is the only female member of the team, she wants to inspire other girls to join.

“There are and have been many female Grandmasters like Judit Polgar and Irina Krush,” Laskaris said. “My hope is to inspire other girls to play and maybe inspire another future woman Grandmaster.”

Laskaris and Hiwale host meetings every other Day 2 in Ms. Malin’s classroom (Q213) and encourage chess enthusiasts to come play.

“It’s not much pressure,” Laskaris said, “Anyone who wants to learn or has even the slightest passion for chess should join.”

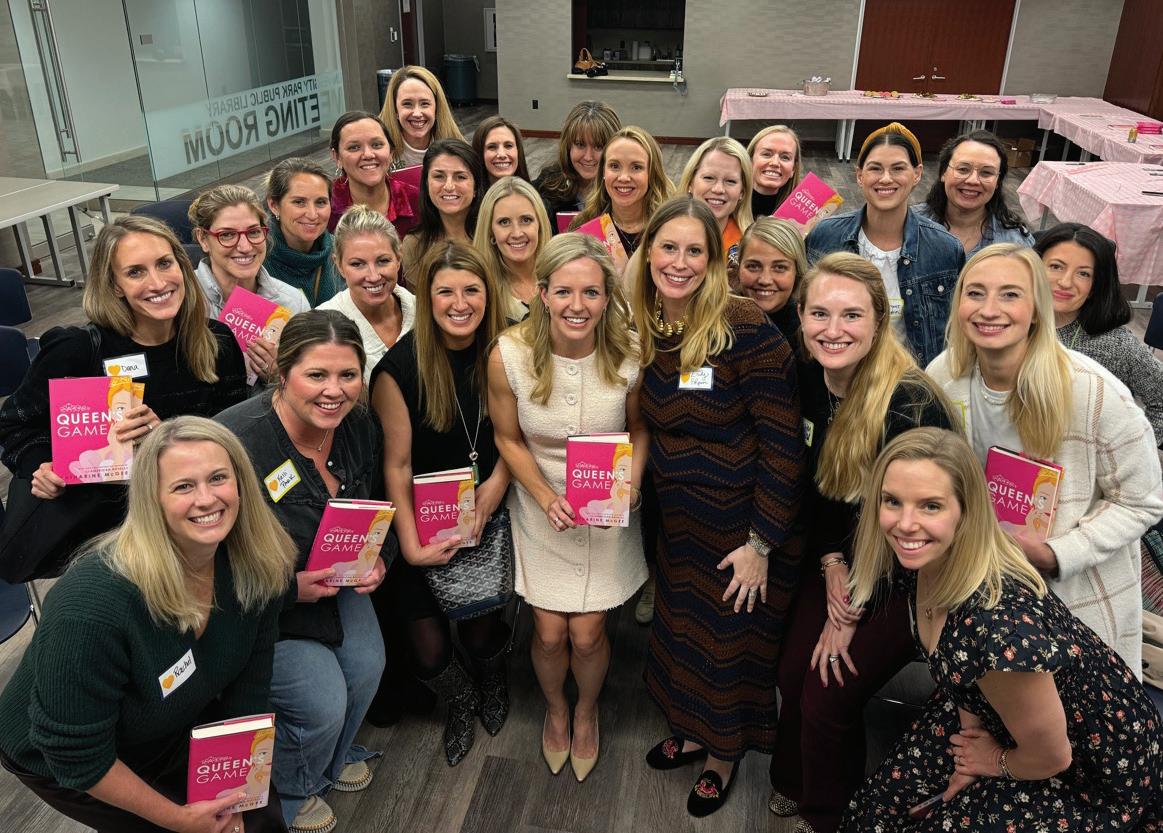

At a recent Houston event for “A Queen’s Game,” her latest novel, Katharine McGee (‘06) told her audience, “This is not your Hallmark rom-com. This is ‘Gossip Girl.’ This is ‘Game of Thrones’.”

The book explores royalty from a historical fiction standpoint. It tells the story of three princesses — Alix of Hesse, May of Teck, and Helene d’Orleans — and how their lives all intersect with the same man: Prince Eddy of England.

McGee (‘06) is also the author of the American Royals series, which explores an alternate reality in which America has a royal family full of secrets, drama and scandals. She emerged on the literary scene in 2016 with her first YA novel, “The Thousandth Floor,” a utopian fantasy set in a futuristic New York City. Freshman Ailey Takashima stayed up until 2 a.m. on a school night reading “A Queen’s Game,” resulting in a “major book hangover” the next day. “It was so amazing and developed, and it felt like a part of me,” Takashima said. “When it was over, it was like all of that ended. I want to be back in the world that she created.”

“A Queen’s Game,” like many of McGee’s novels, ends on a cliffhanger.

“I ended up writing the final chapters of my books the way TV writers approach the end of a TV season — that is, I’m trying to convince you to come back and tune in for the next season,” McGee said. “Because of the nature of my books, which have multiple narrators, they feel structurally similar to a dramatic TV show that has all of the plot lines intertwining in ways that surprise you.”

Comparisons to “Gossip Girl” stem from McGee’s stint as an editor at Alloy Entertainment, where she edited the last book of Cecily von Ziegesar’s “Gossip Girl” series and several of Sara Shepard’s “Pretty Little Liars” books. McGee knew that she did not want to work in publishing forever, so she moved west and earned an MBA at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

years before she is ready to start writing them down on the computer. “With this job, you’re writing something, but then in the back of your mind you’re thinking about the next thing, always,” she said.

McGee tries to have one book come out each year. After a book is finished, she hopes to have her next idea ready to go instead of spending a year figuring out what comes next.

The outlining process for a new book typically takes McGee a few weeks, including detailed storyboards for her main characters. When writing historical fiction like “A Queen’s Game,” she watched documentaries and read biographies and first-person sources to better understand her characters.

“I also did secretly want to write, but I was still scared at that point to even voice it, because it was such a big dream,” McGee said.

After getting into business school, she felt like she had nothing to lose, so she began working on the project that would eventually become her first novel. Her business school experience has impacted the way she thinks about all of her books.

“The books are a brand, and they are something that needs to be marketed,” she said.

Since McGee worked in publishing, she found an agent for her first book by walking down the hall to her boss’s office. “Because I knew the process of publishing, it was not an intimidating black box to me.”

McGee’s writing process begins when story ideas percolate in the background for several

Princess Samantha, set to Lorde’s “Green Light.”

Fans also break down the many romance tropes woven into the stories, including forbidden romances and amnesia plotlines.

McGee says that her writing process has become more streamlined with each new book. “Now that I’ve written nine books, I have developed my own techniques for breaking up the work and eliminating problems at the outline stage so I don’t write as many chapters that will later be cut,” she said.

The first draft, which McGee calls “the heaviest lifting,” takes her about five months. Each successive draft takes less time than the one before. Once her manuscript is finished and has gone through several rounds of editing, McGee receives a proof copy. Proofreaders often only have small edits, such as adding a comma, but McGee still reads every single word at this stage to smooth it out one last time.

During the process, McGee finds it draining to write about some of the real-life tragedies that her characters endure. “A Queen’s Game” does not shy away from the death of loved ones, debilitating panic attacks and broken engagements that leave the women devastated.

“To write such sad things, you have to access your own sad emotions,” McGee said. “It’s like the opposite of therapy.” She recalled times that she felt sad in order to accurately write the scenes, and several chapters made her cry. To clear her mind, she goes out to Houston-area Mexican restaurants with her husband and two young boys, where she drowns her sorrows in queso.

After a new book is released, McGee goes on tour for a week, connecting with new fans each day. “American Royals,” in particular, has gained a large following on BookTok. Fans debrief on shocking cliffhangers and make fast-paced edits of one of the main characters,

When asked about her favorite romance tropes, McGee laughed. “I love fake dating, and I’m also a big sucker for ‘there’s only one bed.’ It just gets me every time,” she said.

At McGee’s author event at Blue Willow Bookshop in west Houston, three generations of women attended, creating a feeling of sisterhood. McGee answered questions from a presenter and then the audience. After raffling off a romance-themed tote bag and baseball cap, (full disclosure: this reporter won), she smiled warmly and signed copies of her book with a gold Sharpie.

According to Takashima, McGee’s books resonate with so many readers because her protagonists break out of their expected roles, discovering themselves and following their passion for love.

Some fans consider the “American Royals” books to be romance novels due to their storylines and tropes, but they are different from typical offerings in the genre. People read romance novels for the emotional payout of two people overcoming obstacles and falling in love, but according to McGee, people read her books for the drama. Anything can happen in a Katharine McGee novel, from amnesia to a fake pregnancy to characters breaking off romantic entanglements that were supposed to be “endgame.”

“Just because two people are together in Book One does not mean they will stay together,” McGee said. “I often say it’s set up almost like fantasy in that way. And as in a really well done fantasy novel — people might die.”

Currently, McGee is working on the second installment of the Queen’s Game duology, and she recently sold her first adult fiction project, slated for a 2026 release.

“I got to do some things that are not as easy for me to do in Young Adult,” she said. The book will encompass a broader cast of characters than her previous series, and she wrote those characters differently because they were in their late twenties and older.

McGee’s agent in Los Angeles is working on getting the “American Royals” series adapted. “I would love to see it as a TV show,” she said.

So would her fans: “The things that she’s trying to say are strong,” Takashima said, “and they’re needed.”

Story by Sophia Kim

Biology teacher Neha Mathur can explain to you all the ingredients found in Celsius energy drinks, including their e ects. She understands the impact of limited sleep on teenagers at a molecular and anatomical level — yet seeing how sleep deprivation a ects her daughter Anoushka is still jarring.

For Anoushka, being a high school junior has been a whirlwind of academic challenges. She is currently taking seven AP classes at Seven Lakes High School. The combination of schoolwork, SAT prep and multiple extracurricular activities has led to many late nights.

Now in her seventh year at St. John’s, Mathur has witnessed students pushing themselves to the limit every day, but seeing the “other side” at home has “opened her eyes” to the struggles students face when they leave school.

“It’s a rat race — just because the person next to her is running faster, she also starts running faster — with no thought to whether it is even worth running,” Mathur said. “I want to tell her to slow down, but this year keeps building up, like a crescendo.”

Mathur loves teaching Honors Biology, widely considered one of the most di cult courses for freshmen, but Anoushka’s stressful junior year has led Mathur to ponder the pros and cons of academic rigor.

“The level of teaching is so high because we are preparing students for the challenges of the future — that’s the end goal,” Mathur said. “But I’ve begun to wonder if it’s too much pressure.”

Mathur worries that if her daughter, or any of her students, stress themselves out, lose sleep or take too many challenging classes just to get into college, they risk losing sight of the fundamental goal of education.

“Students should be pursuing a subject or chal-

As the School’s Director of Basketball Operations, Je Malone travels to tournaments with the team. His daughter Taylor, a freshman at Episcopal High School, has a similarly busy sports schedule, spending most of her time competing and traveling with the The Woodlands Skyline 15 Royal volleyball team.

“Being a high school coach while trying to attend her games becomes di cult at times,” Malone said. “When Taylor has games out of town, I have to watch her matches on television instead of in person.”

“Students should be pursuing a subject or challenging themselves because they love it,” Mathur said. “If they spend their most formative years hating learning, that’s the worst thing.” schoolwork.

Taylor has been playing club volleyball for six years, and during that time, she has learned to balance the constant tournaments with her

“When a student-athlete here tells me they didn’t have time to do homework, my rst question is how well they maximized the time that they had,” Malone said. “I’m able to draw on Taylor’s experiences to give them some pointers when they’re struggling balancing schoolwork and sports.”

Through trips to the theater and opera, former professional opera singer Colleen Kimball cultivated her daughter Autumn’s love for the ne arts at a young age.

“It was a combination of nature and nurture,” said Kimball, now the Director of Clinical Services. “I really feel like artists are born, not made — she had it in her from the start.”

As a senior, Autumn studies costume design at the Kinder High School for Performing and Visual Arts, designing unique stage out ts for each actor.

At St. John’s, Kimball works closely with Upper School counselors Jake Davis and Claire Wisdom to support students during the college application process by counseling students about their concerns.

We are preparing students for the challenges of the future — that’s the end goal. But I’ve begun to wonder if it’s too much pressure.

NEHA MATHUR

Kimball recognizes how much students feel pressure during the college application process, whether from themselves or their peers. “Then, once they get accepted, they worry about leaving their family and going somewhere they’ve never been on their own,” she said.

schoolwork and sports.” advisees, make Most of all, Malone feels like he athletes and advisees because of Taylor. things watches, in

Likewise, through interactions with his junior advisees, Malone learns about study strategies and resources — like Quizlet — that he discusses with Taylor to make her studying even more e cient.

Most of all, Malone feels like he has a better connection with his athletes and advisees because of Taylor.

“She helps me out a lot with the lingo,” Malone said. “The things that she watches, the things that she listens to, the social media, stress hacks, power hours — I’m more in tune to what’s going on.”

NATURE AND NURTURE

As Autumn began lling out college applications last semester, Kimball wanted to be as involved as possible, yet she quickly realized that seniors do not want parents constantly bugging them about their applications.

“Students will tell me things that they’re not telling their own parents, including venting about the pressure they feel from home. So, I started to understand that I had to leave Autumn alone sometimes and not ask too many questions,” Kimball said. “I tried to be on the sidelines if she needed me, and I grew better at letting her be.”

Colleen Kimball, Director of Clinical Services, shares a love of art with her daughter, Autumn.

SJS Swifties reflect on Eras Tour after 149 shows, 3 new albums and over $2 billion in ticket sales

Since the beginning of the Eras Tour, junior Sonia Chilukuri has made over 300 friendship bracelets, watched hundreds of livestreams and spent countless hours designing her out ts. Now, after 149 concerts across 51 cities and 21 countries, the record-breaking tour has nally come to a close.

The Eras Tour began on March 17, 2023 in Glendale, Arizona. Headlined by renowned singer-songwriter Taylor Swift, the performance was a blend of Swift’s 11 studio albums, re ecting each “era” of her life.

When the tour was rst announced, Chilukuri never thought she would actually be able to attend, yet only four days before her shows in Houston from April 21–23, 2023, her parents surprised her with tickets.

“I started crying,” she said. “I was a mess.”

With little time to spare, Chilukuri spent the whole weekend buying materials for a special out t that re ected Swift’s rst “Era.” The nal product, a bedazzled cowgirl hat and a jacket boasting the number 13 — Swift’s lucky number — represented her 2006 self-titled debut album.

Part of the fun and tradition of the Eras Tour experience are the out ts.

Freshman Ashley Smith wore a Speak Nowthemed out t. She attended one of the Houston shows along with classmates Anya Patel and Ainsley Bass, whose out ts were inspired by “Lover” and “Reputation,” respectively. Smith lost her voice from singing loudly the entire time.

Junior Gracey Crawford attended consecutive Houston concerts.

“The rst time, I took a bunch of videos,” she said. “The second time, I could focus on the concert instead of trying to document the whole thing.”

One year after the Houston concerts, Swift released her eleventh album, “The Tortured Poets Department,” which she incorporated into her subsequent shows. Freshman Elisa Feygin attended the Houston tour, yet when TTPD was released, Feygin wanted to return.

“I was mad I did not get to go when she was performing it,” Feygin said. “I would have loved to see that.”

On tour, Swift debuted 22 new out ts and six new songs, including “Fortnight” and “I Can Do It With a Broken Heart.” Her legion of fans — a ectionately known as Swifties — also created traditions unique to the Eras Tour, including chants for songs like “Bad Blood,” “Anti-Hero” and “Delicate.”

“As it evolved, I really wanted to go back,” Smith said.

Other students were lucky enough to experience both the earlier and later versions of Swift’s concert. Chilukuri, who hosted a Tortured Poets Department-themed 16th birthday party, wanted nothing more than to experience the Eras Tour a second time.

A few months after her party, Chilukuri’s father revealed that she was invited to see Swift once more in New Orleans in October 2024 — one of the last cities Swift visited. With six months to prepare, Chilukuri was overwhelmed with excitement. Most days, after completing her homework, she would craft dozens of bracelets to hand out at the show.

The trading of friendship bracelets began after Swift released her 2022 album “Midnights.” Her song “You’re On Your Own, Kid” features a line about making bracelets, which her fans took to heart. In New Orleans, Chilukuri traded 350 bracelets and received 250.

It was sad because I knew there wouldn’t be any more surprise songs, and that was always something to look forward to. But now that it’s passed, I’m just excited for the future.

SONIA CHILUKURI

Though the tour has ended, Chilukuri still makes bracelets to help her de-stress, giving them out to friends and attendees at other concerts.

In September, junior Melanie Chen’s parents had told her to work on her ACT preparation. As she begrudgingly opened the practice book to page 625, she was surprised with two tickets to the New Orleans show on October 26.

At the show, Chen expected to see amboyant costumes, dynamic choreography and entertaining songs. What she did not expect was for popstar Sabrina Carpenter to come on stage and perform a duet to her hit songs “Espresso” and “Please Please Please.”

Lasting more than a year and a half, the Eras Tour featured 19 di erent opening acts and 10 other special guests, which made every show unique.

With singer-songwriter Gracie Abrams opening for Swift that night, Chen felt like the Eras Tour was “three concerts in one.”

In 2023, both Chen and Chilukuri watched al-

most every livestream held on TikTok to listen for surprise songs, which varied by show, featuring two acoustic versions of songs that were not on Swift’s setlist.

Chilukuri admits that she often su ers from social anxiety, but when attending the Eras Tour, “for some reason it disappeared.” In New Orleans, she was trading bracelets with one girl who became a long-distance friend.

The Eras Tour had a massive economic impact, generating over $4 billion in the United States alone. With the average attendee paying $1,327, the Eras Tour grossed over $2 billion in ticket sales, bene tting local restaurants, hotels and other industries.

Yet Swift received backlash for exorbitant ticket prices and faced heavy criticism for her environmental impact. Some linked her private plane usage to excessive carbon emissions: Over 511,000 kg of carbon dioxide in 2024 alone.

“I feel like so many celebrities take private planes,” Chilukuri said. “People just pick on Taylor for that because they don’t know what else to pick on.”

During the last Eras Tour show on Dec. 8, Chilukuri watched the livestream with her mother from home.

“It was sad because I knew there wouldn’t be any more surprise songs,” she said. “And that was always something to look forward to.

But now that it’s passed, I’m just excited for the future.”

Story by Nathan Kim and Nia Shetty

Illustrations by Emily Yen

Backpacking in the middle of Montana for two weeks, miles away from any stable cellular service, junior Parker Moore entrusted his mom and sister with a crucial task: keeping his Duolingo streak alive.

The two set up over 20 alarms to ensure they did not forget. While Duolingo assures its users that their progress will be saved even when o ine, that was not a risk Moore was willing to take with his 800-day streak.

Today, Moore’s widget proudly displays nearly four years of uninterrupted dedication at 1400+ days.

Duolingo was an easy way to get into language practice for Moore, who has a passion for languages. With over 600 million users, Duolingo is the world’s most popular language-learning app. Through a combination of passive and sometimes outright aggressive social media advertising, user-friendly interface and free-of-charge services, the app has skyrocketed in popularity.

Yet the most de ning characteristic of Duolingo is its streak feature. Duolingo introduced streaks in 2017, tracking how many consecutive days users have completed lessons.

Through gami ed learning, Duolingo has found a way to market motivation.

of her cruise ship to keep her more than 1,700day running streak alive.

“Because I’ve had it for so long, it feels almost like an obligation to keep it up,” Moore said. “It’s not really a burden, though. There are a few modes where I can pop in a lesson in 30 seconds and ful ll the streak.”

Sophomore Evan Williams, a videographer for The Review, began his 1,800+ Duolingo day streak in November 2019 and is committed to maintaining it.

“In the beginning, I just wanted to know more Spanish than everyone else. But now, I’m stuck with it for the rest of my life,” Williams said.

“Gami cation,” a term coined by British computer programmer Nick Pelling, is the process of adding game mechanics into non-gaming activities and platforms.

To help users keep their streaks, Duolingo o ers streak freezes, which allow them to preserve progress even if they miss a day. For many, this feature acts as a crucial safety net. Williams admits to relying on them occasionally.

“Sometimes, life gets stressful. I try to rely on streak freezes as little as possible, but I probably use three or four per month,” he said.