Story by Genevieve Ederle & Nia Shetty

For two weeks after Hurricane Helene, Mary and Stephen Lasley’s (‘92) daily routine was to drive to a creek a quarter-mile from their home, set up a sump-pump and distribute water to their neighborhood. The Lasleys even created an Instagram account to inform their neighbors when water would be available.

“One day, we attempted to keep track, and we gured we pumped over 500 gallons that day,” Stephen said in an email.

Hurricane Helene made landfall in North Carolina on Sept. 29 as a Category 4 hurricane. The Lasleys recently moved to Asheville, which is 250 miles inland.

“Hurricane season didn’t really exist in Asheville – until now,” Mary said. “This was something unheard of and completely unpredicted.”

The Lasleys endured a host of issues after Helene including losing power, lacking clean running water and su ering from blocked roads. In the immediate aftermath, the Lasleys launched e orts to alleviate the e ects of the hurricane

Even though drinking water allowed the Lasleys to do a little cooking, non-potable water ended up being in high demand, encouraging the Lasleys to begin their water-pumping operation.

“We now have water running through our pipes from the city, but it is being sent, untreated, straight from our very murky reservoir,” Mary said. “We have been traveling to our friends who live in nearby towns to bathe and do laundry.”

Hurricane season didn’t really exist in Asheville — until now. This was something unheard of and completely unpredicted.

MARY

LASLEY (‘92)

Meanwhile, in Davey, Florida, Audrey Liu (‘24) was in the middle of preparing for midterm exams at Nova Southeastern University when she received news of Hurricane Milton’s imminent landfall. The Category 5 hurricane hit Florida’s west coast on Wednesday, Oct. 9, and although Nova Southeastern was not directly in its path, Liu was still a ected.

Classes were canceled the next day to ensure student safety, and because so many students evacuated campus, including Liu, midterms were

postponed. She managed to get a ight back to Houston before the storm made landfall.

Although evacuation was not mandated, Liu and her roommates left campus to reconnect with friends and family at home. If they had stayed, they knew they would be con ned to their dorms for the duration of the storm and its aftermath.

The hurricane ended up grazing Nova Southeastern University, bringing rainfall and strong winds but sparing the campus from severe damage. The Lasley’s community in North Carolina was not so lucky.

The businesses around Asheville su ered damage from ooding and downed infrastructure. To restore homes, storefronts and morale, those a ected by Helene banded together to pool resources. Residents contributed to GoFundMe campaigns, neighbors shared power from generators and friends gathered to cook communuty meals.

“We mostly feel gratitude that we are safe and that our friends and neighbors are so wonderful,” Mary said. “But it is also tragic and disheartening; there is so much loss and at times the recovery e orts seem endless.”

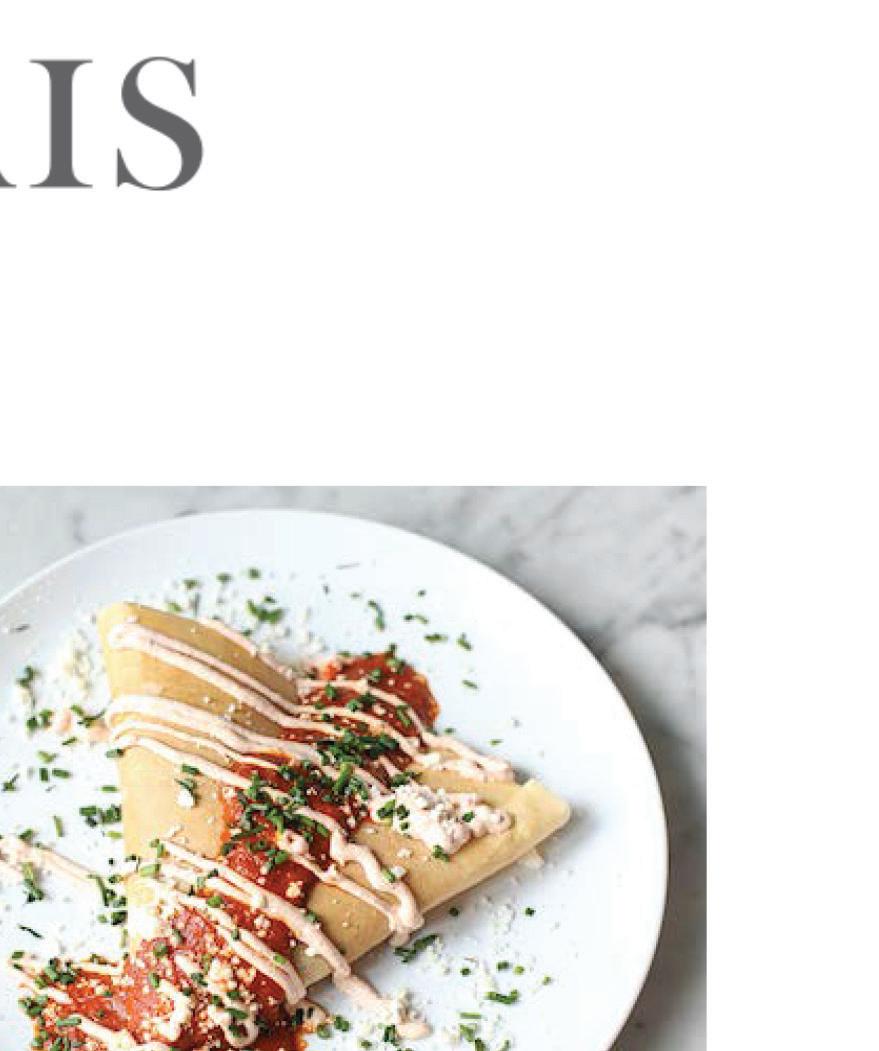

Two years ago, then-mayor Sylvester Turner announced the city would relocate volunteers who, for decades, had been serving free meals to homeless individuals outside the Downtown Public Library. In February 2023, the City of Houston posted a notice that volunteers would be violating the law if they continued serving near Smith and McKinney. The warning signaled an impending showdown between the organization and the city — and the battle is still ongoing.

Food Not Bombs, founded in 1980, provides healthy, vegan meals to homeless individuals in over 1,000 cities and 65 countries. In Houston, they distribute dinner four times a week. Full disclosure: I have volunteered with Food Not Bombs every week for the past ve years, and the last time I wrote about this topic in October 2023, the city was routinely issuing citations to volunteers.

After issuing over 100 citations totalling more than $25,000 in nes, a federal judge ruled in February that the city should temporarily cease its crackdown. The city agreed to stop issuing tickets until the court decides on the constitutionality of

the city ordinance limiting “charitable feeding.” The next hearing is not scheduled until 2025. At the heart of the controversy is the 2012 enactment of the Charitable Feeding Ordinance, which prohibits groups from distributing food to ve or more people in need on public or private property without approval from the property owner. Under mayor Annise Parker (2010–2016), Food Not Bombs was permitted to ful ll their mission, which remained unimpeded until last year.

The problem, and the fines, began when the city decided that feeding people so close to the library was a bad look.

The problem, and the nes, began when the city decided that feeding people so close to the library was a bad look, thus the catalyst to move Food Not Bombs to a less conspicuous location. Then, the city began funding its own food services program, Dinner to Home, located a few blocks from the Downtown Public Library at 61 Riesner Street. Dinner to Home was launched just before the

city began ning Food Not Bombs volunteers, all part of Mayor Turner’s plan to discourage the homeless from congregating in front of the library.

When the city nally stopped funding Dinner to Home, at the cost of over $200,000 a year, the crowds of hungry individuals have been returning to Food Not Bombs.

I have witnessed rsthand the substantial increase of impoverished recipients who gather outside the library for a hot meal. In July, around 140 individuals waited in line, yet by October, as many as 250 were showing up. It used to take an hour to serve everyone in line, but now it takes upwards of 45 additional minutes. Thankfully, there have been enough volunteers — and food — to cover the extra load.

As John Whitmire wraps up his rst year as mayor, he has yet to release the full details of his plan to combat homelessness, so, for now, we await the results of the Food Not Bombs federal court case.

In the meantime, people are still food insecure, which has not changed — regardless of who runs City Hall.

Story by Elizabeth Hu & Brian Kim

On Sept. 30, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed legislation prohibiting legacy and donor admissions for both public and private in-state universities beginning next fall, including Stanford University and the University of Southern California.

The change in policy is a response to the U.S. Supreme Court overturning a rmative action in 2023 (Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard).

With race-based admissions out of the picture, advocates for increased diversity in higher education have turned their attention to colleges that accept students based on wealth or where their parents or grandparents went to college — but not every state waited until the Supreme Court ruling.

In 2021, Colorado barred legacy admissions for public universities, with Virginia and Illinois followed suit earlier this year. Maryland prohibited legacy and donor preferences back in May.

“California and Maryland took it a step further and made it for public and private colleges,” college counselor Steven Scales said. The University of California school system — consisting of public schools like UC Berkeley and UCLA — eliminated legacy preferences in 1998.

With California private colleges joining the rest of the state, there will likely be an increase in lower-income students on campus. There is already a notable di erence in the number of students on nancial aid between public universities and St. John’s School. The University of California, Irvine General Catalogue states that about 75% of students receive some form of nancial aid.

By contrast, only 16% of St. John’s Upper School students received nancial aid in 2023-2024.

“Just being exposed to people from a wider variety of socioeconomic backgrounds makes me a lot more conscious about how I spend my money,” UC Irvine sophomore Eden Tantuco (‘23) said. “I never had to think much about budgeting or spending money on groceries, which sounds pretentious, and I know I’m lucky to have parents who made it that way. But here at UCI, there’s a lot of kids who have to pay for their own tuition, and it just makes me grateful.”

Residential life also di ers from what many Upper School students expect. Less than half of UCI students live on-campus or in campus-a liated housing, while most live o -campus with at least one roommate — one apartment often houses four or ve people to save on rent.

“That’s de nitely a big change from how a lot of students at St. John’s envision their college life to be,” Tantuco said.

Although most colleges only consider legacy status for the early decision pool, legacy and do-

nor admissions represent a substantial part of the college campus community. In 2022, the private universities with the highest percentage of preferential admits were USC (14.4%), Stanford (13.8%) and Santa Clara University (13.1%).

Smaller schools like the Claremont colleges, which consist of Pomona, Scripps, Claremont McKenna, Harvey Mudd and Pitzer, rely more heavily on donor admissions. According to ProPublica, Pitzer received 4.4% of its total revenue from such “contributions” in 2023. The bulk of the school’s revenue (88.9%) came from “program services,” which include tuition and application fees, while every other source of revenue had a lower percentage than “contributions.”

People who are desperate and people in positions of power are always going to find a way.

STEVEN SCALES

From a socioeconomic perspective, ending legacy and donor admissions can further diversify a student body and level the playing eld for those from lower-income backgrounds. However, schools would then need to have more resources to o er nancial aid for students in need, which typically comes from endowments.

Stanford estimates its cost of attendance at over $80,000 while boasting an endowment of $36.5 billion.

Courtney Burger, St. John’s Director of Admissions, notes that “schools like Stanford are sitting on an endowment so large that they could never collect a dollar of tuition ever again and be just ne. They have plenty of endowment for nancial aid. But for schools that struggle with enrollment or don’t have that kind of endowment, being able to meet families’ needs may be more di cult.”

Although a sizeable endowment is typically an unfair advantage in the college admissions process, endowments serve a wide array of purposes such as funding faculty salaries and nancial aid and increasing the diversity of student bodies.

“All schools have strategic priorities,” Burger said, “and the goal of admissions is to meet those strategic priorities.”

In terms of endowment, Harvard leads all American universities with over $50 billion. Among public schools, the University of Texas ranks rst with around $45 billion, while the entire University of Houston System has just over $1 billion.

Scales is optimistic that the changing admissions policy will not signi cantly impact donations.

“I would hope and choose to believe that many people who give back to their alma mater do so out of a sense of honor, obligation, duty, loyalty and nostalgia,” he said. “They give back to their alma mater because of what it did for them, not what it can do for them in the future.”

No matter the status of the applicant, Burger says that the most important aspect is academic t. Although the process di ers between St. John’s and colleges, Burger stresses that all institutions want students to feel successful and supported.

“The big caveat of our job is to do no harm,” she said. “We don’t want to put a child in a classroom where they’re not going to be successful.”

Even though college admissions policies have changed, loopholes persist, including colleges targeting students who live in wealthy zip codes and using public information about people’s philanthropy to determine who is more likely to donate.

Beyond the application process, wealthy families have repeatedly found ways to tip the scales in their favor. In the 2019 Varsity Blues scandal, a uent families participated in an elaborate scheme to pass o less-quali ed applicants as athletic recruits. There have also been reports of families manipulating résumés and paying for medical diagnoses that would grant students extra time on standardized tests, with some even going so far as to pay others to take the ACT or SAT for their children.

In the quest for fairness, Scales acknowledges that there will always be people who game the system.

“People who are desperate and people in positions of power are always going to nd a way.”

Clara University Percentage of first-year admits with legacy connections in 2022

In early October, Director of Purchasing Susan Medellin stopped by the Dennis Uniform store, just a few blocks from campus on West Alabama. Two days later, Medellin was informed that the store had closed, leaving St. John’s — and dozens of other schools — without a uniform supplier.

After the closure, Medellin, who also manages the Spirit Store, elded several emails from parents who had not received online orders from Dennis that they had placed months ago. In retrospect, these delays hinted at the inventory and shipping issues that would lead the company to declare bankruptcy.

On Oct. 19, Dennis Uniform, which acquired Sue Mills in 2022, closed over 35 stores nationwide. After struggling nancially for months, Dennis went out of business by conducting a “permanent mass layo ” and letting go of all its employees from its Portland, Oregon,

headquarters. The closure has a ected more than 40 local schools, including Kinkaid and Awty.

According to Medellin, the school reached out to several companies before deciding on FlynnO’Hara, a company that other Houston schools, like Duchesne, have used for decades.

“They were really easy to work with, and we were able to secure the partnership within a few days,” Medellin said.

FlynnO’Hara has made their entire stock, including khaki shorts, pants and navy polo shirts, available to St. John’s students during this transition period. Yet skirts will not be available until June because St. John’s uses a “proprietary plaid” that is unique to the School.

“FlynnO’Hara is currently utilizing the same mill where our school’s plaid was originally manufactured,” Medellin said. “They are in the process of obtaining

our plaid fabric and preparing for the upcoming school year.”

In light of a potential skirt shortage, the Used Uniform Store, which typically sells skirts for $5, has made its skirts with broken zippers free to community members.

“Replacing a zipper on a skirt is a lot easier than buying a new one,” said Catherine Smith, the All-School Used Uniform Co-Chair.

As of early November, Smith has heard more concerns from parents than the store has seen in sales. She anticipates a greater in ux of customers in the spring, when students have had time to outgrow old uniforms.

“We really haven’t had a demand yet, but we’re prepared to help people in the event that there is one,” Smith said.

Story by Lee Monistere & Dalia Sandberg

Photo by Katie Czelusta

Design by Amanda Brantley

Two weeks after her eighteenth birthday, senior Emarie DiBella left school during a free carrier on Nov. 5 to cast her vote at Pumpkin Park.

“It was a lot easier than I thought it would be,” DiBella said. “All of the poll workers cheered and were very excited that I was there.”

DiBella brought along two friends who were curious to see how the process worked.

“The problem with a lot of people my age is just trying to nd the time,” DiBella said. “But even if we had waited in a long line, the process of voting itself is easier than people make it seem.”

DiBella stresses the importance of exercising the right to vote. She points out that voting is not just limited to the presidential election every four years, and it is important to get involved in any way possible — particularly for young women.

“There are so many women that live in countries where that is never going to be an option, and I’m just a teenager getting that opportunity,” DiBella said. “Even if I am a very small part of a very large process in America, I feel like I am a large part of what has always been a freedom that people have fought for me to have.”

Senior Chloe West, who is too young to vote, says she would “1000 percent vote if I could.”

“It’s hard for me when people are judgemental and hateful about any sort of political choice and then don’t vote,” West said. “It’s not valid to try and have a voice and then not vote.”

DiBella underscores the importance of young people being politically active.

“We are the future. We are the next generation. The people among us are going to be the people that run

important to make sure that we’re aware of what’s going on.”

History teacher Amy Malin heads up the voter registration drives on campus. She reinforces the importance of teen participation. “If they want change or have an idea of what the future should look like, but they don’t vote, then they are basically throwing up their hands and saying, ‘Somebody else deal with it.’”

Voter apathy is real.

“People say, ‘It doesn’t matter to me, I’m tired of hearing about it, I don’t like either candidate, I’m just not going to vote,’” Malin said. “But when they do that, they will still be discontent with the way things are because nothing has changed.”

Senior Daniela Laing echoes Malin’s feelings, saying voter apathy is a “really dangerous ideal.”

“You’re removing yourself from things that a ect you, and you’re taking away culpability.”

The recent general election o ered proof of voter apathy. According to USA Today, voters aged 18-24 cast 14% of all ballots, a steady decrease from 2020 (17%) and 2016 (19%). According to the Texas Tribune, despite record registration numbers, all voter turnout in Texas fell by 6% in 2024.

St. John’s Political Education Club President Jacob Green recently published the club’s Perspectives magazine, which aims to provide a platform for students to share their opinions and educate themselves on various political issues and idea. At the end of the day, if people do not like either candidate and still choose not to vote, “I think that’s completely their choice and it’s not a bad thing by any means,” Green said.

generational trend based on how people tend to vote for the same party in their rst few elections.

According to the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, around 42% of eligible youth voted in 2024. Of those, 52% favored Kamala and 46% favored Trump. Yet, like with every age group this election, there was a notable shift towards Trump this year as compared to 2020. About 56% of young men, a group clearly targeted by Trump’s campaign, voted for him, a ip from the 56% of young men who voted for Biden in 2020. Young women also demonstrated a substantial increase in voting for Trump, from 33 to 40%. Although overall that means a 10-point jump (36% to 46%) in youth support for Trump between elections, young people aged 18–29 were still the age group with the highest support for the Democratic candidate this year.

It’s hard for me when people are judgemental and hateful about any sort of political choice and then don’t vote.

A week before the election, History department chair Russell Hardin predicted that a large turnout of young voters could signi cantly impact the election.

“If polling is correct, it could be signi cant, especially in terms of what we’re seeing with gender and the growing movement of young men to the Republican Party,” Hardin said, noting the possibility of a conservative

Before the election, the Pew Research Center said roughly two-thirds of registered young voters (18-24) aligned themselves with the Democratic Party, while Republicans tended to skew older. Across all seven key swing states, Harris lost on average 10% of voters under 30 that President Joe Biden won in 2020, according to NPR. Although Trump won all the swing states, the majority of the youth preferred Harris over Trump in these states—except Michigan, where both candidates were essentially tied.

The data may indicate a generational shift towards the GOP, but if young people had voted in greater numbers, the results may have been di erent.

DiBella says that voting in the United States is a privilege — especially when compared to other countries where citizens cannot vote.

“Just look at what’s going on in other countries in the world right now and how if you were to be a part of that country, how desperately you would want to be able to use your voice.” DiBella said. “Just the ability to have that choice is very, very special. But that comes with responsibility — and part of that responsibility is to use your voice to vote.”

Malin emphasizes the responsibility of living in a democracy: “Lots of people have come before us and fought for us to have that right. So to just throw it away seems like you’re kind of devaluing all of the work that they did.”

“If you look at the history of the United States, there have been people that have made huge sacri ces to ensure that everyone has their right to vote to participate, particularly the history of people of color,” said U.S. History teacher Jack Soliman. “It’s a big deal. I don’t take that lightly.”

For Soliman, whether or not one votes is more important than who they vote for. “You need to gure out which of the two parties t your interests and your beliefs. If you’re not satis ed, nd a way to force your party to include your voice. If that means voting for a third-party ticket, then vote for a third-party ticket, but I would do that before I would not vote.”

“In Texas, they’re making laws about what men and women can do with their bodies. They’re making laws about how parents can treat their children. They’re passing legislation at local school boards on what books are going to be allowed in the libraries, or whether or not they’re going to have librarians on their campuses. And part of the reason that you get individuals there who may be on the fringes of what most people think is because they’re the ones going to vote in those o -term elections.”

Hardin says that whether going to school or voting, one should do their homework. For elections, that could include looking at websites to understand a candidate’s position or talking to friends. For Malin, it meant reading from the League of Women Voters Guide.

DiBella stresses the importance of going to unbiased websites to see how the news is reported from di erent perspectives, and then talking to other adults.

“Ultimately, come to a decision that you feel comfortable with, not a decision that was made for you by someone else in your life,” DiBella said.

West emphasizes not only being as “well educated as you can” but also broadening one’s mind and shifting viewpoints.

“Try to put yourself in a di erent perspective, maybe people of lower income or di erent race or di erent sex,” West said. “Because you’re not only voting for yourself, you’re voting for the country.”

Daniela Laing credits her perspective to Hardin’s U.S. Government and Politics class where she has learned about the way politics work. Soliman hopes that taking American history classes will encourage students to participate in democracy.

To abstain from voting, it’s not that you’re just not choosing between Harris and Trump, you’re also not choosing the people that affect your life on a more day-to-day basis.

RUSSELL HARDIN

Like Malin, Soliman emphasizes the importance of young voters especially. “You’re 18. It’s time to be an adult. Step up, get over the skepticism, and start doing a little more reading and start participating. It’s time to grow up.”

Hardin argues that voting in local elections is as important as participating in the presidential election.

“It’s not just about the top of the ticket,” Hardin said. “It’s the down ballot, meaning all of the local o cials and all the other races that are happening at the same time. And so, to abstain from voting, it’s not that you’re just not choosing between Harris and Trump, you’re also not choosing the people that a ect your life arguably on a more day-to-day basis.”

Local elections usually receive less media coverage than national and state-wide elections, yet Malin says that local elections can be more impactful. They also receive less turnout, too. The 2018-2022 estimates in State Senate District 17—the one SJS is in— there were 685,722 eligible voters. For the 2024 state senate district 17 election between Joan Hu man and Kathy Cheng, 369,937 people voted, a 54% turnout.

“I hope people come away from their social studies and civics classes with a sense that it’s part of their patriotic duty,” Soliman said. “ I hope they will feel a sense of excitement to go and express themselves for the rst time. ”

Now that the election is over, Soliman implores students to “not just peacefully coexist, but live together, talk and disagree comfortably with each other” whether their candidate won or lost.

“Why not start with the present?” Soliman asks. “The person is going to be president for the next four years whether you like it or not.”

Hardin notes the array of complex variables that impact a person’s politics and says that how one votes is not necessarily a re ection of their personality.

“Usually, people vote with self-interest in mind, but that doesn’t mean sel shness,” Hardin said. “That self-interest could be based on things that they have seen or experienced that are profoundly important to them. There is usually no single reason why people vote, so just understand that the same person you care about who walked into that voting booth is the same person you care about who walked out.”

When interviewed before the election, DiBella said that even if her preferred candidate did not win, life would go on.

“The sun is going to rise the next day,” DiBella said. “And it is still my job to continue to use my voice. There are other ways that I can make a change in my country.”

Lizzie Fletcher (‘93) won reelection for her third term representing the TX-07 congressional district over Caroline Kane, receiving 61.2% of the vote.

turnout among voters aged 18-29 in 2020

cast by voters aged 18-29 in 2024

share of total ballots cast by voters aged 18-29 in 2020 17%

share of total ballots cast by voters aged 18-29 in 2016

share of female voters aged 18-29 supporting Harris in 2024

share of female voters aged 18-29 supporting Biden in 2020

share of male voters aged 18-29 supporting Trump in 2024

share of male voters aged 18-29 supporting Trump in 2020

Wesley Hunt (‘00) was reelected for the TX-38 congressional seat over Melissa McDonough with 62.9% of votes cast. Source:

Cultural commentary by Caroline Thompson

Suddenly, being a “slut” is all the rage. Trends like “hot-girl summer” and “sluto-ween” appear to encourage young women to embrace their sexuality, yet the s-word enforces an ever-present double standard. But does the increasing normalization of the once-taboo word empower or undermine women?

“Slut” is an undeniably powerful tool for dehumanizing women, and it should not be used lightly. Or ever.

The crude epithet gained traction in 1990’s pop culture with Riot Grrrl bands and third-wave feminism. Activists intended to reinforce women’s power by reviving the word, yet their sentiment hinged on using a profoundly misogynistic insult.

That jarring juxtaposition ensured that the word retains its sting. More often than not, “slut” is whispered with a pointed glare, wielded as an all-consuming label that simultaneously debases and dismisses women. Its well-intentioned infusion into the mainstream may have done more harm than good.

Across six centuries, “slut” has consistently belittled women and de ned them by their value to men, pushing aside their autonomy. Demeaning some women with such a descriptor uplifts the pervasive standard that an ideal woman is untouched, without her own agency.

It is worth noting that there is no male equivalent. Terms like “stud” and “player” lack the same sting and seem playful, even aspirational.

While less overt today than in the 1500s, puritanical culture lives on. It’s especially noticeable in traditional religious institutions where girls are taught, through patronizing and heavy-handed similes, that their virtue is akin to a piece of chewing gum or an ice cream cone. Once girls are metaphorically chewed, licked or otherwise spoiled, they will no longer be of value to men.

There are hundreds of belittling platitudes invented to shame sexually liberated women, including charming expressions like, “Why buy the cow when you can get the milk for free?” or “Who

wants damaged goods?”

Today’s teenage girls feel the pressure to both own their bodies and show skin, to not be prude but to not come o as easy. America Ferrera’s famous speech in “Barbie” nailed it: it is literally impossible to be a woman.

St. John’s tacitly endorses this narrative by pushing girls to wear longer skirts and keep shirts tucked, all to appear more modest. The implication correlates skirt length with the ability to be taken seriously.

By keeping the word in circulation, men retain their power over women’s reputations.

If a girl has a short skirt, the fear is that those extra two inches of leg will cause pandemonium for distracted male students. There is no speci ed length (or tightness) for boys’ uniform shorts.

The dress code gives teachers the responsibility to examine and call out inappropriate skirt lengths, an invasive practice that normalizes the scrutinizing of women’s clothes. Society feels emboldened to inspect women’s lives through a microscope and judge their character, extending to reproductive rights and access to birth control. That entitlement comes in part from words like “slut.”

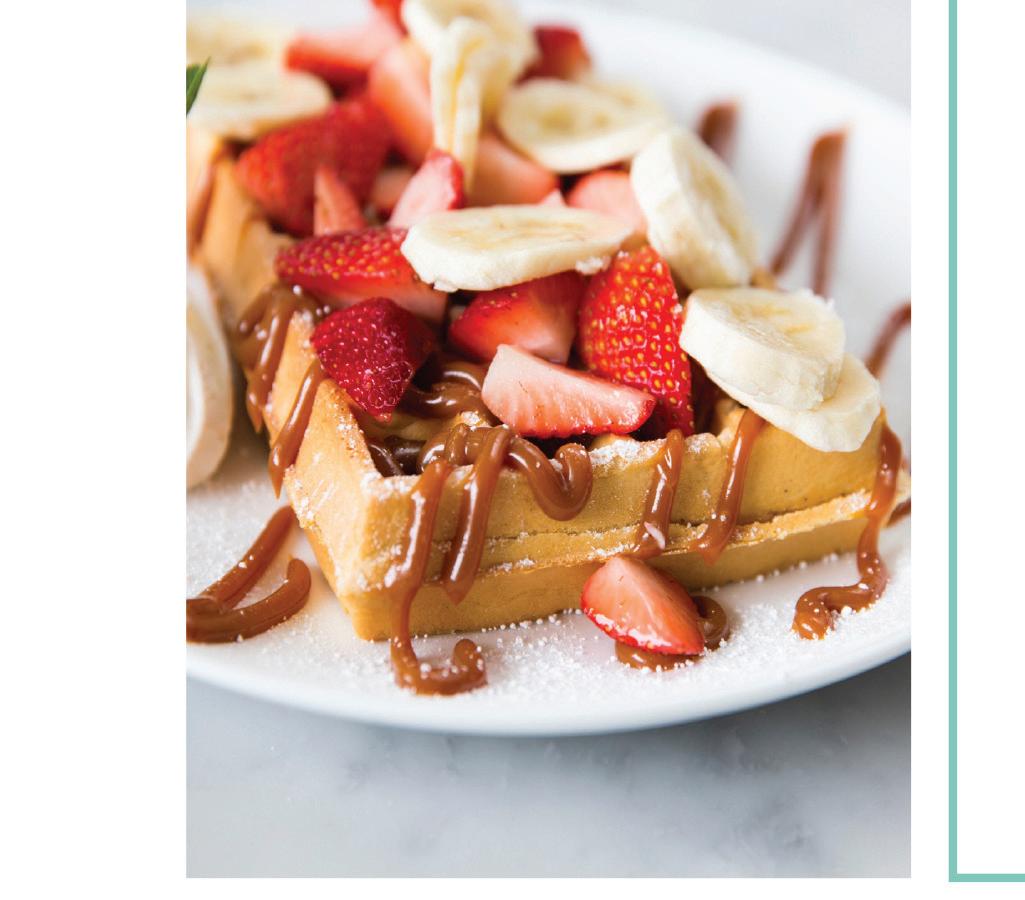

FEEDING OUR ST. JOHNS FRIENDS AND FAMILY FOR OVER 40 YEARS

Unwillingly, it is a statement for women to either show o or hide their bodies. Even though modern women have the ability to make choices for themselves, sometimes that means choosing to serve the male gaze. Objecti cation has been rebranded as empowerment, and women remain on display to please others.

The fact is, the word “slut” erases a woman’s credibility. By keeping the word in circulation, men retain their power over women’s reputations. Women also fear that being sexually free means their experience with harassment or assault will be written o as an example of “she was asking for it.” “Slut” is a one-word excuse for sexual predators. Simultaneously, the word is weaponized in the movement to abolish abortion and birth control. Planned Parenthood states that the stigma around abortion comes from “the transgression of a gendered norm,” essentially when women do not ful ll imposed expectations of female sexual purity. Men can walk away from fatherhood while women are shamed for not accepting the consequences of their promiscuity.

Ultimately, “slut” is part of a desperate e ort to perpetuate outdated gender stereotypes. Instead of tearing down women’s con dence through misogynistic vocabulary, re ect on the word’s warped mythos and its very real impact. We need to continue dismantling the rampant double standard against women and dissolve the language that upholds it. By abolishing the s-word, we abolish an instrument of hypocrisy and promote true equality.

Story by Nathan Kim

by Kenzie Chu

All work and no play makes Middle School a dull place — or so say administrators who are experimenting with no-homework units.

Following a comprehensive audit in which students, faculty and parents were surveyed, the School’s wellness team concluded that the majority of students are overscheduled. Led by counselor and wellness coordinator Cynthia Powell, Director of Clinical Services Colleen Kimball and Medical Director Scott Dorfman, the team discovered that students are specializing in extracurricular activities at increasingly younger ages. As parents look toward an increasingly competitive college admissions environment, they push their children to find their niche even earlier.

Head of Middle School Megan Henry says she is concerned that homework may further reduce the time that middle schoolers can spend “being kids.”

“We cannot dictate what parents sign their kids up for outside of school,” Henry said, “but there are a number of things that we are trying to do to respond to these concerns about our students’ well-being.”

Henry recalled how students lost seven days of school following Hurricane Harvey in 2017, yet students recovered well academically.

After discussing with faculty members, administrators developed the no-homework unit policy. Essentially, grade-level teaching teams would choose one to two units per semester to instruct without homework. These units would be spaced throughout the year to provide students a small break.

“We obviously can’t change everything,” Henry said, “and we are not going to be a school that does not have homework. That’s not a part of our philosophy.”

Homework serves a particular purpose for each department. For math, textbook problems help solidify concepts. For science, reading at home leaves more time for in-class experimentation. For world languages, vocabulary practice allows students to read and speak more in class. For English and history, assigned chapters and writing assignments contribute to more in-depth classroom conversations.

Students interviewed in the Middle School were excited about the new policy, but praised the benefits of homework.

Seventh grader Sanaa Narasimhan quoted her science teacher Madelaine Doherty about the importance of homework: “What’s in the textbook is the glue, and what’s said in class is the glitter. If you don’t pay attention to the homework, it doesn’t stick.”

We obviously can’t change everything, and we are not going to be a school that does not have homework. That’s not a part of our philosophy.

MEGAN HENRY

Narasimhan is also grateful that the Middle School administration is paying attention to extracurriculars. Playing club soccer in The Woodlands means that car rides become homework time, and getting home late means Narasimhan sometimes stays up until midnight finishing assignments.

Fellow seventh grader Aiden Koo, who commutes an hour to school, participates in football, wrestling, golf and after-school tutoring. He says that the no-homework policy has made things easier, but he admits that homework does serve an important purpose.

“During some classes, the learning style that the teachers provide doesn’t work for all students, so when they give homework, it gives us another chance to understand the concepts,” Koo said. While administrators are optimistic about the potential of the reduced homework program in its inaugural year, the concept is not new. When the School was on a set five-day schedule, some departments would alternate ceasing homework to give students a break. But for many students and teachers, this just pushed more homework to the following day.

Seventh grade English teacher Jason Kirkwood appreciates the current plan to reduce stress. Kirkwood likes to remove homework from creative writing and grammar units, preferring to teach that content in class.

“It’s cognitive overload,” Kirkwood said. “There’s this notion that if we assign a lot of homework, we teach kids to be responsible, but it often ends up having an adverse effect in that we’re throwing too much at them. They’re not able to focus and compartmentalize their learning.”

According to Henry, in a community full of “Type A, highly motivated overachieving people,” it is easy to get swept up in the culture of maximizing every second. Sleep is sacrificed for that extra hour of extracurriculars. Weekends and breaks become essential for “getting ahead.”

“As adults, as parents, as educators, we are trying to be much more aware of what kids are going through and encouraging kids to speak up, so we can listen and address it,” Henry said.

Only three months into the school year, Henry is appreciative of the feedback from parents and students, comparing anecdotal data to families with students who have already gone through the Middle School. Henry is aware of the logistical hiccups that come with implementing a new idea.

Moving forward, the administrative team is excited to hear more from faculty and other members of the community.

“We’ve had some bumps, as one might expect whenever you try something new, and that’s okay,” Henry said. “I’m not trying to move a needle from 0 to 60, but if we can be doing little things over time to push a needle in a healthier direction, then I think we’re on the right path.”

OVER-SCHEDULED busy Thursday

School -> 8:15 - 3:35

AFTER SCHOOL:

- Basketball Game - Violin Lesson - Soccer Practice - Return home at 10:45 - Start Homework at 11 - Sanaa, Class 7

On Sept. 24, Marcellus “Khaliifah” Williams, a Black man convicted of murdering a white woman, was executed by lethal injection at the Potosi Correctional Center in Mineral Point, Missouri.

“It felt like we’re going back in time,” said junior Adaobi Achugo, who cried when she heard the news. “I was numb because I could not fathom the fact that we’re still in a day and age where innocent Black people are getting murdered. It felt like another lynching.”

In 1998, reporter Felicia Gayle was stabbed to death in her St. Louis home. Three years later, Williams was charged with her murder, but according to his lawyers, there were myriad problems with the trials: allegations of racial bias during jury selection, witnesses incentivized by promises of leniency and money, and an absence of forensic evidence linking Williams to the crime. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to death.

For 23 years, Williams sat on death row and professed his innocence.

In the weeks leading up to his execution, the case captured national attention. People across the country shared Instagram posts and TikTok videos about Williams, which contributed to over 630,000 signatures on a Change.org petition to stop his execution. U.S. Representative Cori Bush (D-MO) took the Williams case to the House floor in an impassioned speech to save his life.

In their application to the U.S. Supreme Court for a stay of execution, attorneys wrote that his conviction and death sentence “were secured through a trial riddled with constitutional errors, racism and bad faith, much of which only came to light recently.”

After the Supreme Court refused to grant Williams a stay, Missouri Governor Mike Parson said that none of the “real facts” of the case proved Williams’s innocence.

The damage we to a family and by

“Capital punishment cases are some of the hardest issues we have to address in the Governor’s Office, but when it comes down to it, I follow the law and trust the integrity of our judicial system,” Parson said. Senior Justin Wright, who has long been an activist for criminal justice reform, says it is disheartening to see state governments acting against the will of the public, especially when it comes to executions.

“It is exhausting to fight for people and then not have your work be validated,” Wright said. “How many times can people rally around trying not to get somebody murdered? How many Marcellus Williamses can people fight for, and they still die anyway?”

Just a 90-minute drive up I-45, before Sam Houston State University, is the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville, where Robert Roberson is set to be executed. He is one of 178 inmates currently on death row in Texas.

On Jan. 31, 2002, Roberson woke up to the sound of crying and went to his daughter Nikki’s room to investigate. He found the two-year-old unconscious on the floor. Thinking she had suffered a fall from her bed, he took his daughter to an emergency room in Palestine, Texas.

At the ER, Nikki’s temperature spiked to 104.5 degrees, and she soon died from substantial head injuries. Unaware that Roberson had autism, the medical staff thought he lacked emotion, considering the circumstances.

At his trial, one nurse testified that his daughter was bruised and had a handprint mark on her face. The doctor assumed Roberson had been abusing his daughter and pronounced Nikki’s cause of death as shaken baby syndrome, an injury caused when a child is so forcefully shaken that they get brain damage.

Lead detective Brian Wharton accepted this diagnosis and arrested Roberson, who was charged with capital murder and sentenced to death.

Last year, a judge in New Jersey deemed shaken baby syndrome junk science. Research indicates that the symptoms Nikki was experiencing were likely due to pneumonia and her fall. However, the Texas Junk Science Law — which allows defendants to challenge their convictions if they rely on non-credible evidence — was not applied in Roberson’s case.

Roberson’s execution was initially set for Oct. 17, but just hours before, the Texas Supreme Court issued an order to stay the execution. On Nov. 15, this temporary stay was lifted.

At the time, the stay was an 11th-hour victory for Roberson and the state lawmakers who fought for his acquittal. Roberson’s case is unusual: according to Laura Arnold, co-founder of Arnold Ventures and former Innocence Project Board Member, it is rare for dozens of State Republicans to rally against the use of the death penalty.

“I think that has enormous potential for a policy awakening,” Arnold said. “A huge number of legislators in the state have said, ‘I believe in the death penalty. I’m a Christian person. I am as conservative as they come — and I don’t think we should execute this person.’”

we end up doing and community someone is so greater than the of revenge.

MORENO-EARLE, SENIOR

death penalty, yet in the 1930s, all but two had reinstated it. The argued that capital punishment for Black Americans would somehow reduce the number of lynchings.

From 1910 to 1950, roughly three-quarters of those legally executed in the South were Black. The most common capital offense was rape because Black men were often stereotyped as sexual predators who preyed upon white women. Between 1930 and 1967, 90% of men executed for rape were Black. In 1972, the landmark Supreme Court case “Furman v. Georgia” resulted in a moratorium on capital punishment. According to Dow, the scholarly consensus on the ruling was that the death penalty was applied in an arbitrary manner.

“Many people in 1972 thought, that’s it, we’re done with the death penalty. The states will just move on to some other form of punishment,” Dow said. “But, in fact, the states were quite anxious to have capital punishment.”

States began rewriting laws to supposedly decrease inconsistencies, and by 1976, five death penalty cases reached the Supreme Court. They were discussed under the name of the lead case “Gregg v. Georgia.”

This time, the Court ruled in favor of capital punishment: “Furman v. Georgia” was overturned.

From 1976 to 1994, 40% of those executed were Black, even though Black Americans constituted just 13.6% of the population. According to a 2006 study examining cases during this period, “in cases involving a White victim, the more stereotypically Black a defendant is perceived to be, the more likely that person is to be sentenced to death.”

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Wright, who researched mass incarceration for an Independent Study Project last year, says that racism has infiltrated every part of the criminal justice system, from arrests to sentencing.

White: 25.3%

Hispanic: 26.4%

There aren’t many examples of things in the world where the whole of society wants to kill you. And they want to do it in a grotesquely horrible way, as a sort of ritual sacrifice to some imaginary god of deterrence.

“It’s hard to come to any other conclusion than that the justice system targets and disproportionately affects different groups of people,” Wright said. “When it comes to the death penalty, it’s very easy to fall into unabashed and unconditional support. But you have to keep in mind, who does this disproportionately affect?”

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH, DEATH ROW LAWYER

President-elect Donald Trump recently shared his plans to extend the death penalty to drug traffickers and migrants who kill American citizens. Moreno-Earle says that this policy is a step in the wrong direction.

“The death penalty is going to be used as a tool against people who can’t defend themselves properly,” he said.

Clive Stafford Smith has been opposed to capital punishment since he was a teenager. As a lawyer, he has worked on over 400 death row cases.

100,000).

For many Americans, capital punishment is a moral issue. Some students, like Wright, do not think states should have the right to kill — under any scenario.

“When considering the history of this country and its continued history of using state-sponsored violence as a means of controlling minority populations, we as citizens have to be very careful with the powers that we give it,” Wright said. Other students trust the process. “I think we haven’t been fully successful,” said Bryce, an Upper School student who wished to remain anonymous. “But I do have faith in our justice system.”

Bryce notes that he hopes to become more educated on capital punishment in the future.

An Upper School faculty member, who wished to stay anonymous, recounted how her uncle was murdered while working at their small family business. She was eight at the time. The perpetrator was promptly prosecuted and sentenced to death, yet there were a number of appeals as he fought his punishment.

“The process of putting someone on death row seems like a waste of resources,” she said.

Decades later, the teacher does not subscribe to the Hammurabi ideal of an “eye for an eye.” She doesn’t even remember the name of the person who killed her uncle nor the outcome of his case.

“He can be in jail and pay for his crimes in that way,” she said. “If the Parole Division feels that he has rehabilitated, learned from his experiences and is going to be a contributing member of society, I also believe in that process. I sometimes feel like our judicial system is at the point where there are a lot of prosecutions that happen without adequate evidence or false evidence.”

the person should be sentenced.”

Arnold adds that the maintenance of death row is also pricey. Death row cells have a different design than standard prison cells and require far more security.

Texas has also paid $192 million to compensate for wrongful convictions since 1985. Dow says that all the expenses stemming from the death penalty have significant ramifications for rural counties; they have less revenue, so capital trials can eat up a sizable percent of their budgets.

If you’re going to believe in an eye for an eye, it behooves you to ensure that the system is perfect. Death is irreversible.

With capital punishment, there has been a pattern of innocent people being executed. Countless cases of potentially innocent individuals on death row, including Williams and Roberson, have cast doubt on the dependability of the system. The Death Penalty Information Center reported that, since 1973, at least 200 innocent people have been sentenced to death.

“That’s the most heartbreaking part. You’re completely denying justice to these people who are put there and staged by the federal prosecutors,” Yu said. “We’ve seen so many cases of this, where people are just wrongfully on death row for years. It’s a very, very sad part of our justice system.”

Arnold says that proponents of the death penalty should be especially concerned about the number of wrongful convictions.

“If you’re going to believe in an eye for an eye, it behooves you to ensure that the system is perfect,” Arnold said. “Death is irreversible. And the minute you execute somebody who’s proven innocent, it all falls apart.”

The unreliability of the system, Arnold argues, casts doubt on the entire American government since “a government is only as credible as its institutions.”

Morality aside, Bryce considers capital punishment economically practical. “I think there’s a certain limit where they’re not contributing to society,” he said. “At that point, why should we put resources into their livelihood?”

Arnold disagrees with the premise that the death penalty saves taxpayer money, noting that capital punishment “requires a whole set of circumstances that are very, very expensive for the carceral system.”

A 2014 study found that a death penalty case costs an average of $3.8 million dollars in Texas, while the average life sentence in prison costs $1.3 million.

Dow, who has worked over 120 death row cases, says that trials involving the death penalty typically take longer than the average criminal trial, with the jury selection process being especially lengthy. As a result, the state has to pay for two defense lawyers, an investigator, two prosecutors and a judge — for months on end, at the very least.

“We don’t want to make a mistake,” Dow said. “So we spend an enormous amount of money investigating whether

“The cost that you’re absorbing, given the lack of benefit, just does not make logical sense,” Yu said.

Despite the controversy, states like Texas still regularly execute individuals. Dow says that inertia is the reason why the practice has not been abolished.

“The states that have the death penalty cling to the idea that they can identify which [cases] are the worst and then reserve the death sentences for those. And that turns out to be a failed experiment,” Dow said. “But a lot of times, an experiment can be failing and people will still think that it has a chance of working one day.”

When asked how to make St. John’s students care about the death penalty, Achugo admitted, “I don’t think you can.”

Last April, Upper School students gathered for an assembly on mass incarceration led by Arnold and Yale professor Emily Wang (‘93). During their discussion, Arnold pointed out that Texas was incarcerating more individuals than any other state. Some students applauded the statistic. Others gasped in horror.

Arnold, the mother of three SJS students, says she tried to give the students who applauded the benefit of the doubt, but she described the moment as “very disturbing.”

Achugo, who is African American, observes a lack of empathy in the Upper School towards Black incarcerated individuals — whether or not they are on death row.

“It depends on your background,” she said. “And I feel like people can’t identify with it because they don’t know the circumstances. They can’t really relate to it.”

Arianna Doss (‘23), a sophomore at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, says that prejudices against incarcerated people also contribute to this apathy.

“The general non-incarcerated public underestimates the intelligence and helpfulness of people who are incarcerated,” she said. “The way we dehumanize incarcerated individuals is truly insane.”

Dow worked his first death penalty case in the early 1990s after meeting a death row inmate who did not have legal

Source: Death Penality Information Center

representation. The inmate’s execution was just two weeks away, yet Dow agreed to be his lawyer.

“Honestly, I wasn’t even against the death penalty, but I didn’t think this guy should be executed without a lawyer,” Dow said. “I just found it to be satisfying both intellectually — because it’s extremely complicated, and I like complicated problems — and emotionally. It’s very rare that as a lawyer, you actually have a chance to save somebody’s life.”

While working the case, Dow met with his client’s family and got to know him “as a human being.”

“One case leads to two, two leads to four, four leads to eight and so on,” Dow said. “And you wake up one day and you are a middle-aged death penalty lawyer.”

Dow, a parent of an SJS graduate, has written four books on the death penalty. NPR listed his memoir, “Things I’ve Learned From Dying,” as one of the best books of 2014. Clive Stafford Smith began working on death penalty cases after he graduated from Columbia Law School in 1984. Despite the emotional lows of the job, he says that he “wouldn’t do anything else.”

“I’ve had to watch six people die, and I wish that didn’t happen. But in one way or another, I’ve won 98 percent of my cases. You get to give people their life back and do all sorts of extraordinary things along the way,” Stafford Smith said. “I think we are there to look around the world for the people who are being the most hated and then to get between them and the hatred.”

Stafford Smith has written five books and has received numerous accolades not only for his work on death penalty cases, but also for representing detainees at Guantanamo Bay. He has been named an Officer of the Order of the British Empire and received both the Gandhi International Peace Award and the International Bar Association Human Rights Award. In 1999, he founded Reprieve, a non-profit dedicated to fighting the death penalty, indefinite detention without trial, extraordinary rendition, and extrajudicial killing. For Dow, a difference between being a death row lawyer and practicing other forms of law is the stakes.

“If you lose, your client gets executed,” Dow said. “So if you screw up, you don’t have a chance to fix it later.”

Dow advises those in his line of work to have a support network. “For some death penalty lawyers, it’s other lawyers in the community,” he said. “For me, it’s my wife, my son and my dogs.”

So when does it all end?

According to Dow, the death penalty will eventually disappear, possibly in his lifetime.

“The reason will not be that people have had a sudden shift in their moral thinking. What I think is going to happen is that people are going to realize it’s a waste of money.”

For more information on the death penalty, follow organizations like the Innocence Project, National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, American Civil Liberties Union and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Death penalty No death penalty Temporary moratorium

Story by Kate Johnson & Brian Kim

Design by Amanda Brantley

After a seven-hour ight from Boston to San Francisco, Hailey King (‘24) nally returned to her Stanford dorm room at 2:30 a.m. A defender on the Cardinal eld hockey team, King had no time to rest and recover from a 2-0 loss to new Atlantic Coast Conference opponent Boston College. A morning exam was hours away.

Stanford moving to the ACC from the Paci c-12 Conference was part of a wave of NCAA conference realignments this year. ACC teams compete sometimes over 3,000 miles away, which translates to ights over ve hours each way.

The Stanford eld hockey team, which previously played in the Big East Conference because the PAC12 does not include eld hockey, is used to traveling across the country for matches. With time zones also working in their favor, the team is granted an advantage over other teams dealing with conference realignment.

“It’s worse for the teams on the East Coast. When Duke and UNC came here, they took a red-eye back home, got back at seven in the morning and had to go to class,” King said. “When we come back, we’re gaining three hours, whereas other schools are losing three hours.”

Despite the challenges, Stanford displayed considerable potential in its rst ACC season, nishing as the No. 6 team in the conference.

For athletes in other sports, the realignment experience varies. Ella Flowers (‘22), who swims for the University of Southern California, has yet to see many changes from USC’s move to the Big Ten Conference.

“We’re still mainly competing with the same [schools] because, even with the conference realignment, a lot of teams are not wanting to travel the distance of their new conferences for meets,” she said.

“It’s the same kind of competition we’re used to.”

Flowers acknowledges that her sport will see adjustments in the coming seasons. Because conference realignment is primarily driven by exposure and media deals for college football, a multi-billion dollar industry, smaller sports like swimming are often overlooked.

It’s a litttle annoying because it’s very obviously only for football.

ELLA FLOWERS

Long commutes take time away from already-packed schedules, despite e orts to aid student-athletes via extensions and online lectures. Teams typically leave for road trips midweek and return Sunday, playing at least two games and training on days o .

“You have scouting, meetings, lm practice and meals, and it all kind of builds up,” King said. “Growing up playing club eld hockey helped with time management because we would travel a lot, but I’m de nitely not used to cross-country ights or the time di erences.”

The ACC is signi cantly more competitive in eld hockey than the Big East, and ve of the conference’s nine teams are ranked in the Top 12 including No. 1 North Carolina.

“Our team is de nitely in a building era, so we have a long time to grow together to get there,” King said.

“We’ve yet to see how it’ll a ect swimming, but it seems inconvenient for us and even more challenging for all the other non-revenue sports,” Flowers said. For fans of college football, conference realignment o ers new opportunities. Sophomore Ziyad Gilani, a lifelong University of Texas fan, sees the Longhorns’ move from the Big 12 Conference to the Southeastern Conference as a positive.

“Even though we’re probably going to lose more games in the SEC, it gives us a better chance of making the playo s because it’s thought of as a better conference,” he said.

Gilani looks forward to grudge matches against fellow Big 12 transfer and longtime rival Oklahoma and rediscovered rivalries against Texas A&M and Arkansas, former members of the Southwest Conference.

“We had a lot of pseudo-rivalries in the Big 12 like TCU, Baylor and Texas Tech,” he said. “But now, the SEC rules for protected rivalries mean that we get to play Oklahoma every single year for the foreseeable future.”

2,792

Several major conferences welcomed new members for the

16

When freshman wrestling phenom Alex Choo was deciding on a high school to attend, the St. John’s wrestling program checked all the boxes. After attending a few team practices and having several discussions with head coach Alan Paul, Choo was all in.

Yet he still had to meet other academic quali cations before he could call St. John’s home.

“I know a couple of people who went to St. Thomas and Kinkaid to wrestle, and they denitely had to put in a lot of work to get into those schools,” Choo said. “But I feel like their overall process was a little bit easier.”

It is no secret that to get into St. John’s, student-athletes must meet the same academic standards as non-athletes, no matter how much they could help the Mavs.

“St. John’s can ‘recruit’ people and say, ‘We want you to come here,’ but they have to have the test scores to get in,” said former basketball captain Adley Halligan (‘24), whose aunt, Kathy Halligan, is the girls’ head basketball coach. “It’s like a walk-on position.”

Even when athletes are accepted, some are hesitant to attend due to the pressure of balancing academic rigor with sports.

“No one’s gonna be like, ‘Oh, I want to go to St. John’s to get recruited to play sports,’” said eld hockey captain Chloe West. “A lot of the decision comes down to what you want in academics.”

For students seeking both academic and athletic achievement, SJS is often a better t.

“A lot of the public schools that I wanted to go to didn’t have the academic standards that I wanted,” Choo said.

The admissions requirements, along with St. John’s reputation of academic rigor, mean that many competitive athletes often choose to go elsewhere.

immediate impact on a program provides a selling point to athletes seeking a balance between school and sports.

“If you come to a school like St. John’s, you can take the lead and probably start sooner,” Halligan said. “The decision depends on the person.”

The coaches also in uence the decisions of athletes who will apply or attend. In basketball, Halligan has seen several instances in which, after a coach leaves, players recruited under that coach follow suit. In some ways, high school sports mirror the college athletics mindset in which players increasingly commit to a coach.

“Now that the coach is gone, what does the school have to o er you still?” Halligan asked.

Although many other schools can promise a higher level of athletic competition, less experienced athletes can see more playing time with the Mavs instead of sitting the bench behind a team of recruited starters. The incentive of playing more minutes and making an

On the other hand, St. John’s students, who tend to be more academics-oriented, are unlikely to leave if their coach does not return.

“I value wrestling, but my academics come rst,” Choo said.

According to West, coaches are also a major factor in drawing eld hockey players to certain schools. After the departure of head eld hockey coach Becky Elliot last year, St. John’s hired Emily White from Episcopal to lead the program. White

led the Mavs to another SPC championship.

“With Coach White now at SJS, and after our SPC win, I de nitely see more people coming here for eld hockey,” West said.

West says the Maverick eld hockey team, which has been ranked as high as No. 2 in the nation by MaxPreps, has found other ways to work around the no-recruiting policy. St. John’s high schoolers who play for Pride Field Hockey Club will encourage the younger players there to apply. Once a player receives an acceptance letter, all the Mavericks who play for Pride will push for them to attend.

“Once, this awesome player was choosing between Kinkaid and St. John’s, so we brought her a cake at club practice, took her out to lunch and were like, ‘please come, please come,’” West said.

“And it worked.”

Similarly, when Choo attended wrestling practices over the summer, the team welcomed him with open arms. “They were really nice and inclusive, which de nitely swayed me a little bit more to come here,” Choo said.

West says that ultimately, where an athlete chooses to attend depends on numerous factors — not just a school’s sports program.

“What do you want in academics?” West asked. “Where do you live? What do you value in a school community?”

St. John’s School

2401 Claremont Lane Houston, TX 77019

review@sjs.org

www.sjsreview.com

Facebook SJS Review

Instagram @sjsreview

Member National Scholastic Press Association

Pacemaker: 2015, 2018, 2023, 2024

Pacemaker Finalist: 2019, 2020, 2021 Best of Show: 2017, 2021 (Spring), 2021 (Fall), 2022

Member Columbia Scholastic Press Association

Gold Crown 2015, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024 Silver Crown 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019

Writing Excellence 2022

First Place Editorial Leadership (PSJA) 2022, 2023

SNO Distinguished Site 2018-2024

Print Editors-in-Chief

Aleena Gilani, Elizabeth Hu, Lucy Walker

Print + Online Editors-in-Chief

Amanda Brantley and Serina Yan

Managing Editor-in-Chief Lily Feather

Online Editors-in-Chief

Eshna Das, Aien Du, Aila Jiang

Print Deputy Editors

Lee Monistere, Dalia Sandberg, Katharine Yao

Copy Editors Kate Johnson, Nathan Kim, Yutia Li, Riya Nimmagadda

Design Editors

Jennifer Lin and Michelle Liu

Assistant Design Editors Ella Hughes and Emily Yen

Multimedia Editor Katie Czelusta

Online Section Editors

Bella Dodig, Genevieve Ederle, Amina Khalil-Zegar, Nia Shetty

Business/Production Manager Lex Langlais

Sta Isabella Adachi, Ainsley Bass, William Burger, Colin Caughran, Jayden Chen, Kenzie Chu, Khoi Chu, Rebekah Costa, Juliet Dow, Rian Du, Viv Fox, Maddie Garrou, Sophia Giron, Melody Han, Maggie Hester, Angel Huang, Zain Imam, Derek Jiu, Mikail Khan, Brian Kim, Sophia Kim, Nicholas Laskaris, William Liang, Lev Macpherson, Emily Matthews-Ederington, Katelyn McCollum, Neve Merideth, Sarah Nguyen, Georgia Pulliam, David Qian, Noa Shaw, Mabrey Stokes, Caroline Thompson, Horatio Wilcox, Evan Williams, Preston Wu, Wanya Zafar, Brayden Zhao

Advisers

David Nathan, Shelley Stein (‘88), Sam Abramson

Mission Statement

The Review strives to report on issues with integrity, recognize the assiduous e orts of all and serve as an engine of discourse within the St. John’s community.

Publication Info

We mail each issue of The Review, free of charge, to every Upper School household, with an additional 1,000 copies distributed on campus to our 709 students and 98 faculty.

Policies

The Review provides a forum for student writing and opinion. The opinions and sta editorials contained herein do not necessarily re ect the opinions of the Head of School or of the Board of Trustees of St. John’s School. Sta editorials represent the opinion of the entire Editorial Board unless otherwise noted. Writers and photographers are credited with a byline. Corrections, when necessary, can be found on the editorial pages. Running an advertisement does not imply endorsment by the school.

Submission Guidlines

Letters to the editor and guest columns are encouraged but are subject to editing for clarity, space, accuracy and taste. On occasion, we publish letters anonymously. We reserve the right not to print letters. Letters and guest columns can be emailed to sjsreviewonline@gmail.com.

Opinion by Lily Feather

It was a headline perfect for rage bait: “I Paid

My Child $100 to Read a Book. And You Should

Too.” Or at least it was, until the New York Times, perhaps realizing that not every parent has $100 in x-my-unreasonable-children money, removed the last bit.

I don’t know why this article was the one that got my attention. After all, I’ve managed to keep my cool in a sea of iPad kids and 12-year-olds rampaging through Sephora. People take for granted that today’s children are little monsters, and the parents let them get away with it. But at some point, someone needs to say: Enough! Close your wallet and send your kids to the public library.

At rst I decided to disregard pearls of wisdom from a guest writer who referred to her preteen daughter as a “monosyllabic blanket slug” in the New York Times. Then I realized she was not just another “mommy blogger” — she was featured in the New York Times. So this bribery was not an isolated incident; it was a symptom of an epidemic.

Though large-scale studies on reading bribery are far and few between, I located one from the Daily Mail: A survey of 500 families with children aged 3 to 8. Sixty percent of parents admitted to bribing their children with money, sweets, or even trips to theme parks. In a survey I sent out to our newspaper sta , 6.5% had been paid to read a book, 12.9% had a sibling who was paid to read, and 19.4% knew a friend who had been paid to read.

What’s worse is that these parents celebrate their ingenuity, claiming they have “tried everything” and nally found the solution. Going back to the NYT article, Mireille Silco noted that her daughter had read a few graphic novels and even listened to the entire Harry Potter series through audiobooks. But that wasn’t “classic deep reading,” which she de ned as “two eyes in front of the paper and nothing else going on.”

Parents like Silco berate their children when they don’t read, but they also discount reading if the child picks up the “wrong” kind of books, or if the child reads the “right” kind of books but in the “wrong” format. With all that pressure to read, it’s no wonder the kids don’t want to do it.

“Classic deep reading” is an excellent turn of phrase, reminiscent of “collaborative learning environment” or “critical thinking skills.” It’s too bad that “classic deep reading” doesn’t exist — there are no psychologists, reading specialists or educators who have de ned, studied or encouraged it. There is no Tooth Fairy, there is no Easter Bunny and there is no Classic Deep Reading. Scrolling on a Kindle, listening to Audible and reading manga are all perfectly legitimate ways to enjoy a good book. Cece Bell’s

graphic memoir of growing up deaf, “El Deafo,” was named a Newbery Honor Book in 2015. I wonder if Silco would tell blind people that reading Braille or listening to audiobooks isn’t “classic deep reading.”

One of the aspects of my childhood that I appreciated most was that my parents didn’t force me to stick with activities I disliked. There was some hand-wringing about my refusal to try yoga and my abandonment of swimming and piano lessons, but, in the end, my parents gave me plenty of unstructured time to discover my own interests. No $100 bills were exchanged for ballet lessons. If there had been, maybe I never would have viewed myself as an active participant in my own interests.

Lily Feather

Turns out, I wasn’t alone in my thinking. Days later, the New York Times compiled responses to the article from teenage readers. One astutely noted, “Paying children to read does not mean they will comprehend the book’s story, feel the emotions, or picture the scenery the author described.”

In a sentence beyond parody, Silco suggested, “other parents of reluctant readers open their wallets and bribe their kids to read, too.” These parents are a familiar archetype to me. They are readers themselves, they want the best for their children and they clutch their pearls over the amount of time that children spend on their phones — and then they hand over the money, ignoring other root causes for reluctant reading. By trying to replace the instant grati cation of the Instagram reel-induced dopamine hit, these parents instead reinforce entitlement: everything must come with a reward.

Even if these parents somehow succeed in inspiring a love of reading, they can’t change the core of what they are doing: throwing money at a problem — and encouraging their children to do the same.

“I can’t say I’m proud — but I am extremely satis ed,” Silco wrote. Yet a growing number of children won’t be. They will be driven by extrinsic motivations — behavior caused by external rewards or punishments — instead of intrinsic motivations, which leads to the undertaking of an activity for its inherent satisfaction.

So, what can we do with reluctant readers? First, don’t nag. Some children simply don’t like to read, so try encouraging other o -screen hobbies. Second, people (including librarians, teachers and independent bookstore owners) devote their careers to nding the perfect book for each child, and kids may be more inclined to listen to them than their parents.

Reading is a deeply personal experience, and kids need freedom to discover its joys on their own terms.

We have never experienced a day like November 6th.

The sense of division on campus was palpable. Some of our peers were gleeful; others were overcome with despair. During lunch, despondent students crowded into Quadrangle classrooms to grieve en masse. As the day went on, the number of students in class dwindled, preferring to commiserate with the school counselors or in the English department o ce.

With the Upper School a shell of its former self, some of us on The Review had an opportunity to escape.

Thursday morning, a small group of editors ew to Philadelphia for the National Student Journalism Association Fall Convention along with thousands of student journalists who crammed into the Downtown Marriott, just down the street from the Liberty Bell, to learn more about our craft.

But the election found a way to creep into our trip, too.

Pennsylvania was the biggest battleground state — a place where the Harris and Trump campaigns each poured over half a billion dollars into swaying the state’s 8.86 million voters. The political debris was strewn across the city in the form of weather-worn campaign signs and a handful of protestors outside the Planned Parenthood.

During our sessions, we learned about election coverage. Speakers highlighted the important role

that student journalists play during times of intense polarization and stressed our responsibility to tell every side of the story.

As students noted during the SPEC assembly, if we shy away from discussing a topic, it becomes taboo. That is why The Review chose to cover the election (pg. 4-5). Not because it was easy, but because it was necessary.

The country will survive this political polarization. During our trip, we visited Independence Hall, where the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were signed. Visiting one of the most important places in American history reminded us of how much our country and its inhabitants have endured — and how we will continue to do so.

No matter what happens next, The Review will continue to platform those making positive change, whether they are feeding the hungry (pg. 2), advocating for reform in the criminal justice system (pg. 8-10) or supporting each other in the wake of a hurricane (pg. 2). After an election that has taken so much energy out of everybody, we need people who uplift those around them more than ever.

As your editors, we ask that you be a part of this movement, regardless of your political leanings. Support your peers, whether that means o ering a shoulder to cry on or showing up to a forum. We are all in this together.

by

I don’t know, I’m a freshman.

how

Why, the last time I saw you, you were [extends arm] this tall! Where does the time go?

Their old Dell desktop is still running Windows 8, they’re locked out of their AOL account and they can’t find the slip of paper with their password written on it.

Even if you’re not a football fan, you will pretend you are, just to get out of this conversation.

The shared fence needs repairs, and the neighbors won’t pay their fair share. They play music after 8 p.m. They park in front of our house. It’s too hot. It’s too cold. It’s too wet. It’s too dry. It’s too dark out. It’s too light out. It’s not so much the heat, but the humidity.

Have you met a nice [insert religion, gender] yet?

Aren’t you cold in that? Did you get a discount on those ripped jeans? The nuns would’ve never let us wear that.

Did you see that picture on Facebook? It’s so nice that the chihuahua and the alligator could be such good friends.

[nods head]

Honorable Mentions: What is brat? Is Taylor Swift married yet? Are you eating enough? Do you still like Wild Kratts?