Salmagundi Magazine

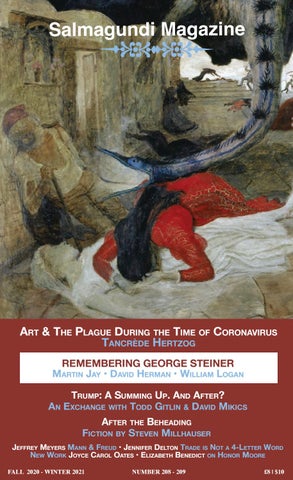

Art & the PlAgue During the time of CoronAvirus tAnCrèDe hertzog REMEMBERING GEORGE STEINER Martin Jay • DaviD HerMan • WilliaM logan trumP: A summing uP. AnD After? An exChAnge with toDD gitlin & DAviD mikiCs After the BeheADing fiCtion By steven millhAuser

Jeffrey meyers mAnn & freuD • Jennifer Delton trADe is not A 4-letter worD new work Joyce carol oates • elizabetH beneDict on honor moore FALL 2020 - WINTER 2021

NUMBER 208 - 209

£8 | $10

Salmagundi Magazine

1

Editor-in-Chief

ROBERT BOYERS Executive Editor

PEG BOYERS Associate Editors

THOMAS S.W. LEWIS

MARC WOODWORTH

Assistant Editors

CATHERINE POND JAMES MILLER

DAN KRAINES

Editorial Consultants

JAMES O’HIGGINS

DREW MASSEY

Regular Columnists

RUSSELL BANKS / STEVE FRASER DAVID MIKICS / MARTIN JAY / CHARLES MOLESWORTH MAX NELSON / DANIEL SWIFT / DUBRAVKA UGRESIC Circulation Advisor YAQARAH SAGE Circulation Staff CYNTIA ISMAEL JANE O’REILLY Social Media Manager LIV FIDLER Editorial & Circulation Assistants BRYNNAE NEWMAN ADDISON BRAVER

SALMAGUNDI

IS

PUBLISHED

Q U A R T E R LY

BY

SKIDMORE

COLLEGE.

ALL CORRESPONDENCE SHOULD BE ADDRESSED TO SALMAGUNDI, SKIDMORE COLLEGE, SARATOGA SPRINGS, N.Y. 12866. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $25 FOR ONE YEAR, $40 FOR TWO YEARS, $55 FOR THREE YEARS. INSTITUTIONS $37.00 FOR ONE YEAR AND $55.00 FOR TWO YEARS AND $75 FOR THREE YEARS. FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTIONS ADD $25.00 PER YEAR. PLEASE MAKE PAYMENTS BY ELECTRONIC CHECK OR CREDIT CARD CARD AT HTTP://CMS.SKIDMORE.EDU/SALMAGUNDI/ SUBSCRIPTIONS.CFM. SAMPLE COPIES: $8. SPECIAL RATES ON BULK ORDERS AVAILABLE TO ORGANIZATIONS AND STORES: WRITE TO SALMAGUN@SKIDMORE.EDU, ATTENTION CIRCULATION MANAGER. PERMISSION TO REPRINT ARTICLES MUST BE SOUGHT FROM AUTHORS. PRINTED BY BENCHEMARK PRINTING, SCHENECTADY, NY. DISTRIBUTED IN THE U.S.A. BY INGRAM PERIODICALS (P.O. BOX 7000, LA VERGNE, TN 37086) , UBIQUITY DISTRIBUTORS (INFO@UBIQUITYMAGS.COM), AND USOURCE INTERLINK INTERNATIONAL (27500 RIVERSIDE BLVD. SUITE 400 BONITA SPRINGS, FL 34134). MICROFILM: NATIONAL ARCHIVE PUBLISHING COMPANY (NAPC) P.O. BOX 998 ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106-0998. SALMAGUNDI IS ARCHIVED VIA JSTOR. WE WILL NEXTCONSIDER UNSOLICITED MSS. FROM JANUARY 2021 THROUGH APRIL 2021 SENT AS HARD COPY SUBMISSIONS TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS: SUBMISSIONS / SALMAGUNDI MAGAZINE / SKIDMORE COLLEGE 815 NORTH BROADWAY / SARATOGA SPRINGS, NY 12866

SALMAGUNDI is indexed or abstracted in the Information Access Database, Ebsco, Abstracts of English Studies, Sociological Abstracts, American Humanities Index, An Index to Book Reviews in the Humanities, MLA International Bibliography, Twentieth Century Criticism, Roth Publishing Poem Finder, etc. Copyright © by Skidmore College

ISSN 0036-3529

Skidmore’s

Salmagundi Magazine #208 - 209

1 A Quarterly FALL 2020 - WINTER 2021

COLUMNS Guest Column: Alternative Facts & Post-Truth Brice Particelli — 3 Guest Column: Abortion, Reproductive Justice, and Political Imagination / Erin Greer— 17 FICTION After the Beheading / Steven Millhauser —37 REMEMBERING GEORGE STEINER After George Steiner: A Personal Recollection Martin Jay — 52 Steiner on Screen / David Herman — 75 George at Chess / William Logan — 89 FICTION Qiechang / Leslie Epstein — 96 ESSAY Plague in the Time of Coronavirus: The Representation of the Black Death in the Arts / Tancrède Hertzog — 129 POEMS Two Poems / Joyce Carol Oates — 151 Needles / Marc Berley — 158 Harvest / Lloyd Schwartz — 159 Two Poems / Christina Hutchins — 161 Lot’s Wife / Claire Scott — 167 Two Poems / Ben Corvo — 169

2

Aqueous / Paul Bailey — 173 To Rome / John Poch — 174 Two Poems / Scott Harney — 176 Two Poems / Harry Newman — 180 ESSAYS Must the Father Die? Reading King Lear Over A Lifetime / Margaret Morganroth Gullette —184 Thoman Mann and Sigmund Freud: The Friendship Of Genius / Jeffrey Meyers — 203 Looking for Bucharest / Bonnie Costello — 219 Pepe, LeBron, and Trump: Sports, Literature, and Interpretation / Ronald A. Sharp — 235 BOOKS IN REVIEW Trading Places / Jennifer Delton — 250 The Memoirs of Honor Moore / Elizabeth Benedict — 258 Night and Day—You Are The One / Regina Janes — 265 Mirth and Folly Were The Crop / Paul Delany — 279 AN EXCHANGE Trump: A Summing Up. And After? Todd Gitlin & David Mikics — 284 Notes On Contributors — 296 for additional & on-line only content—including

archival material, images, audio, and video—please visit

SALMAGUNDI MAGAZINE https://salmagundi.skidmore.edu instagram: salmagundimag

The Great American Eclipse

3

Guest Column

Alternative Facts, Post Truth & The Great American Eclipse

BY BRICE PARTICELLI History is filled with solar eclipse stories. One is associated with the start of a civil war in England, when an eclipse coincided with the death of King Henry I in 1135. Another is chronicled in the Islamic text Bukhari Sharif, following the death of Muhammad’s infant son in 632. The earliest in written record was in China, 2137 B.C.E., when astrologers Ho and Hsi got drunk and failed to predict one. To miss an eclipse was a bad omen, so the emperor cut off their heads. One of the most famous was in 1919 when Arthur Eddington used an eclipse to provide evidence of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. By comparing how starlight moves past the sun, versus how it travels at night, Eddington offered proof that gravity causes light to bend. It made Einstein a celebrity overnight, and the findings were reproduced again and again until it became an accepted theory. During the 2017 eclipse, I was at the controversial Creation Museum, which uses selective science to claim that our 14-billion-year-old universe is, in fact, only 6,022 years old. I was there in part because I have family nearby, and this place has always intrigued me, but also because as a professor my research in education has increasingly turned toward how we dupe and get duped by misinformation. In a society where phrases like “alternative facts,” “post truth,” and “fake news” abound, the idea of a place that mimics science education—imitating the exhibits, placards, curricula, architecture, and children’s programming of natural history museums—to promote an

4

BRICE PARTICELLI

anti-science message was too interesting to ignore. And what better time to visit than when our country’s eyes are focused on a science-explained event—our moon passing between our planet and our star? * * * Built in 2008 with $27 million—a significant amount of money in the rolling hills of Northern Kentucky, the Creation Museum has seen more than three million visitors. With a petting zoo, ropes course, lagoon and gardens, and 75,000-square-feet of stone and glass structures, it bears resemblance to any large natural history museum. Past an armed guard and a brontosaurus statue, the glass doors open to a grand hall with a thirty-foot Chinese paper dragon hanging above. An animatronic display of a child plays next to two velociraptors, and display cases hold imitation scrolls and swords of famous dragon myths, along with a guiding question: “Were Dinosaurs Dragons?” The overwhelming answer is, “Yes.” It’ll cost you $30 to get any further, and $5 to leave, paid to a talkative parking lot attendant. These “Young Earth Creationists,” as they describe themselves, argue for a version of earth history that fits a literal interpretation of the Christian Bible. The earth, sun, stars, and humans were created on October 23rd, 4004 B.C.E. and a global flood killed almost everything in 2348 B.C.E., leaving only two of each kind of animal on a boat with eight people, including 600-year-old Noah. From that starting point, the facility crams in a few selected pieces of scientific discovery. The supercontinent of Pangaea existed, sure, but it broke into seven continents during the one-year flood rather than over 200 million years. And when the boat landed, animals repopulated the earth on rafts of fallen trees—kangaroos to Australia, tigers to India, ocelots to Mexico, dragons to Denmark. Science isn’t denied here, not exactly, but it is drastically manipulated, even putting poetry to work. Along the walls, exhibits explain that one-thousand-year-old children’s stories like Beowulf and St. George and the Dragon are proof that giants and dinosaurs roamed the earth in recent history. And because unicorns are mentioned in the King James Bible,

5

The Great American Eclipse

they existed too. (Even though “unicorn” is just a creative translation of the Hebrew word re’em, a wild ox.) It’s an exhilarating history built on the imagination of our fictions: The Flintstones, Godzilla, The BFG, Jurassic Park, My Little Pony. In fact, one of the children’s books they publish depicts Noah battling a T-Rex in a Roman-styled coliseum. It is a fascinating bit of acrobatics that forces you to recall childhood lessons. In case you missed it in school (which is surprisingly likely, you’ll see), scientific consensus tells us that the universe is approximately 14 billion-years-old, the Earth 4.5 billion, and dinosaurs went extinct soon after an asteroid strike 65 million years ago. Homo sapiens gradually evolved into our present form around 300,000 years ago, and by 4004 B.C.E. we were domesticating pigs in Europe, growing rice in Japan, farming squash in South America, and making wine in Western Asia. By 2348 B.C.E. there were expansive dynasties in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China. To cram 14 billion years into 6,022 creates an exciting story, then, but this place’s power isn’t only in imagination. While it has absolutely no influence on scientific research, its focus on schools and families influences millions. Along with more than three million visitors to the Creation Museum, Answers in Genesis (AiG), the parent organization, puts out a steady stream of public speakers, curriculum, and video content. They’ve published more than 300 books, focused largely on children’s education, as well as a self-described “peer-reviewed technical journal” for their “researchers” to publish in (that no research organization considers peer-reviewed). It’s a brilliant strategy, co-opting the educational and academic genres that scientists and science education professionals use, but using them to undermine those very groups. And their influence is growing. They recently opened a second facility, called “Ark Encounters,” which cost $100 million to build and received land grants and tax credits from the state of Kentucky. It topped a million visitors in their first year and a half. * * *

6

BRICE PARTICELLI

The sky is a grayish blue, but it doesn’t look like the moon is anywhere near the sun. I’m on the back patio of the Creation Museum and it’s a few minutes before the height of the eclipse, but the frogs are still singing. The wind rustles the cattails below as if nothing is happening. There is no silence or stillness. It’s barely any darker, to be honest, and it’s easy to see how Ho and Hsi might have missed a partial eclipse if they’d been tipping a few. The sunlight swallows the moon. There are perhaps two hundred people on patios and by the lagoon below and the crowd is growing. On the steps, a mother and her two daughters lie in the middle of the path, elbows down and legs up with their eyes to the sky, glasses on. Other families stand in small clusters, passing glasses back and forth. I flew from New York for this, but I knew that we’d only get 92% eclipse. Other areas, like Western Kentucky, are in the path of totality. I could have just as easily gone there, but I wanted to be here, in this place. While the scene is gray-blue, when I put on the eclipse glasses the world transforms. The sky becomes a backlit geometry project, a kid’s shoebox assignment—blunt shapes made stark by the tinted glasses. It is striking. On a deep gray backdrop, a black sphere sits in front of an orange one. It’s beautiful in its simplicity. Our moon, 220,000 miles away, passing in front of our star, 93 million miles away. It is a simple action on a grand scale—a toddler jumping in front of the camera—made all the more real because our sun gives us light, and life, and it is disappearing in the middle of a clear summer day. For a facility that positions itself as a natural history museum, it’s surprising to see that they don’t have any educational programming. “Our astronomer is in Oregon,” the ticket agent apologized, but there aren’t even any signs, announcements, or special exhibits. There is nothing besides two customer service representatives standing quietly in the corner, handing out glasses as if they don’t have enough. There’s no mention of timing (2:27pm), or percentage (91.9%), let alone its significance, history, or relevance to the institution’s mission. It is the most talked about natural event of the year—dubbed “The Great American Eclipse” because it cuts across the continental United States—but there isn’t even a flyer.

7

The Great American Eclipse

On the patio next to me there’s an older man in a camo hat who doesn’t have eclipse glasses. I offer mine. He looks through them quickly, hesitantly, before passing them back. He’s from Mississippi, he tells me. He’s retired and he and his wife are passing through in an R.V. “We’re wasting time,” he laughs. “No real rush.” While we’re chatting, his wife comes over and offers him glasses. “They gave them to me inside,” she says, turning around before she’s arrived. “I’m going back in.” “Are you sure?” he says, “Take a look first.” “No, you do it.” “This young gentleman offered me his. You should look.” She looks quickly before handing them back, “I’m going back to the A.C. Take your time.” It’s a sweet moment. Both are trying to do something nice for the other, but neither wants it. After she leaves, the man inspects the glasses. “Oh boy,” he says, “these don’t have the little square thing.” I ask what he means and he shows me the QR code on mine. “I heard that this is how you can tell if they’re fake. They can fake everything else, but not this.” The news was filled with reports of companies selling unsafe glasses, but I don’t have the heart to tell him that there’s nothing difficult about printing a QR code. “They have the right ISO number though,” I tell him, “and they’re made by one of the NASA-approved companies.” He furrows his brow and puts the glasses in his pocket. He doesn’t seem to trust that the Creation Museum has bought the right ones. * * * In 2007, a study published in the journal PLoS Biology found that 60% of high school biology teachers didn’t spend significant time on even basic understandings of evolution. This, despite the fact that the National Academy of Sciences calls evolution “the central concept of biology.” While the study found that community pressures pushed them to minimize evolution, the problem goes deeper. More than one in six biology teachers agreed with the statement that, “God created human beings

8

BRICE PARTICELLI

pretty much in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years or so.” One in six high school biology teachers doesn’t accept the central premise of the field they’re teaching. It should be of little surprise, then, that in a 2017 Gallup poll on human origins, 38% of Americans responded similarly, responding that, “God created man in present form.” Americans have been taught to distrust evolution, despite the fact that it’s been settled science for over a hundred years. This puts the Creation Museum in the odd situation of being a fringe element in the scientific fields it purports to represent, while also fitting securely within a broadly held public view. * * * On the morning of the eclipse I attended one of the Creation Museum’s hour-long lectures, “Noah’s Ark and the Flood” by Georgia Purdom, who has a Ph.D. in molecular genetics from Ohio State and directs AiG’s educational content and curriculum. Her talk is in the auditorium, just past the bookstore, and there are at least a hundred people in attendance. I settle into a spot in the back as Purdom walks onto the stage slowly, unassumingly, as if walking into a college classroom where her students are on their phones. She is slow to smile, and her voice is nasal but welcoming. She says hello and starts a video promoting “our newest themed attraction,” as she calls it, “Ark Encounters,” a life-sized replica of Noah’s ark. The video is flashy and well-produced, and clearly designed as an advertisement. After suggesting people visit, she sets up the problem, as she sees it, beginning with a poll AiG did of Christians 20 to 29. “Only 51% believe that the global flood and Noah’s ark are real events in history.” This is because the ark is “presented as fairy tale” by most churches, she says. The rest of her lecture is delivered like a fun-laced lecture at a science education conference, but filled with slides designed to mock the concept of evolution and provide anecdotal evidence of creationism. She leads us through AiG’s design of their ark, including arguments over which animals would have made it (and why dinosaurs made the cut),

9

The Great American Eclipse

and she tells us that “secular South Korean scientists” determined that their ark would have been seaworthy. She shows us a picture of a fossil of one fish with its mouth around another as proof that death was fast for the majority of fossilized animals. Most fossils are from a single event, she argues, from a flood in 2348 B.C.E. (Including fish, apparently….) She then shows us a tyrannosaurus rex bone with soft tissue attached, said to be 68 million-years-old in a study published in Nature, arguably the world’s most respected research journal, before encouraging the crowd to laugh at their conclusions. “No way is this millions of years old,” she says, “Trust me, I’m a molecular biologist.” Purdom then explains the stakes. The “end times” are coming, she tells us, and we want to be on the right side. “It’s not going to happen today during the eclipse, by the way,” she laughs. “And it’s not going to be flood next time. It’s going to be fire. And it could happen any time.” She pauses. “We have to be ready.” But there’s a solution. “We’ve got to stop teaching our kids Bible stories, because they happened. The Bible is history. And we have plenty of resources out there for you,” she says, pointing to the bookstore doors, “so there’s no excuse.” At the end, there’s no Q&A, but she’s available in the bookstore. When I get to her, she’s talking to a college student. He’s just started studying science at a religious university but he’s frustrated by his “Old Earth Creationist” professors. They’re teaching “secular science” alongside the Bible, arguing for Intelligent Design, that God guided the hand of evolution. He’s frustrated, he says. “But it’s inspiring to watch you.” Keep studying, she tells him, and stick to your faith, “We need more good people like you.” She offers her business card. “Call me or email me. I’m always happy to help.” * * * The entrance to the main exhibit at the Creation Museum overwhelms your senses. After walking past the Chinese dragon and the animatronic child with her velociraptor friends, past the fudge station and the Stargazer’s Planetarium, you’re asked to pause for a movie at

10

BRICE PARTICELLI

the “Special Effects Theater” (complete with shaking chairs and mist in your face), before walking down a cavernous walkway meant to look like sandstone canyons. The canyon opens up to the first room where there is a replicated, full-sized dig site. A video above shows a Young Earth Creationist and a “secular paleontologist” working at the actual site. The Young Earth Creationist explains that facts can only be seen through two “different starting points,” either “Man’s Word” or “God’s Word.” He argues that science relies on interpretation rather than fact, so we must decide which of these “starting points” to believe. The “secular paleontologist” (who is never really named) quietly nods in agreement. The rest of the exhibits lead visitors through this choice. “Man’s Word” is equated with all of the scientific traditions of archaeology, paleontology, biology, geology, and more, and it leads to suffering and confusion. “God’s Word,” on the other hand, is equated with AiG’s understanding of how science and the Bible mesh, and it leads to salvation. All knowledge is biased, they argue, so you must choose which bias to believe. In their vision, the choice is black and white, Man or God, Science or AiG. There isn’t room for discussion. You can’t consider Intelligent Design; you can’t question how Biblical texts were collected, edited, and translated; and you can’t focus your faith only on the New Testament. Those approaches—the majority of Christianity—lead to a fiery hell. To doubt one word of the Bible is to doubt the entire religion. Scientific studies are presented only to be mocked. Exhibits encourage viewers to use their own powers of observation to come to their own conclusions, rather than listen to “experts.” It’s a method that researcher P.J. Wendel, in the journal Science & Education, calls 19th Century object-based epistemology—an approach to evidence that is based on a time when objects were presented in museums without context, and viewers were asked to wonder. Scientific method, reproducible experiments, and peer review are ignored. It allows AiG to offer a singular vision that researcher Ella Butler, in the journal Ethnos, describes as “conspiracy theory epistemology,” where all data is approached with a conclusion in mind. If the facts don’t match, then they are ignored or belittled.

The Great American Eclipse

11

When I teach research methods, we talk about this approach as “confirmation bias”—a bias that occurs when we want to confirm what we believe, despite the evidence. It is one of the most common human biases, and it is why scientific method requires a skeptic’s approach that demands reproducible findings. It is also why we encourage hedging phrases like “indicates that” and “need for further study.” Good research is built on the idea that knowledge is endlessly perfectible. The Creation Museum takes advantage of this. Any hedging or adjustment is evidence that people make up their own reality. For instance, an exhibit on the radioactive dating of rocks in the Grand Canyon uses the differences between dating methods on a rock (or perhaps several rocks in a similar area; it is intentionally unclear) to conclude that all dating methods must be wrong. If we can’t decide whether these rocks are 800,000,000 or 1,200,000,000 years old, they argue, then we might as well believe that it’s 6,022. It’s an approach that should sound familiar in our “alternative facts” era. To accept facts that don’t fit your ideology is to show weakness. To embrace complexity is to accept defeat. Even engaging in a discussion that uses these rules can be problematic. AiG earned their biggest boost in 2014 when Ken Ham had a highly-publicized debate with TV personality Bill Nye, titled, “Is Creation a Viable Model of Origins?,” which has had 7 million views on YouTube. The event concerned many researchers who were worried that Nye legitimized creationism by subjecting it to a debate, rather than leaving it to the scientific scrutiny that had negated young earth hypotheses centuries before—that he elevated Young Earth Creationism by fighting it. Nye, after all, was positioned as the representative for scientific consensus on geology, biology, history, archaeology, paleontology—hundreds of thousands of scientists replicating and furthering work across generations and cultures, while Ham represented at best a couple dozen unknown researchers whose work is only published in religious journals. And the debate has become a powerful tool. AiG uses it constantly, picking apart Nye as a representation of all of scientific knowledge. He is mentioned constantly in their materials, and any question or hesitation he has is used to discredit all of science. Any change—even if it’s through new discovery—is used as proof that science is too flawed to trust. AiG’s hand is presented as steady. Strong. Unchanging.

12

BRICE PARTICELLI

* * * “I don’t remember learning anything else when I was a kid,” Georgia Purdom tells me. “God created the world in six days.” It is a month after my visit, and Purdom and I are talking on the phone. I’d asked her to talk because I needed to understand how someone goes from a Ph.D. in biology to directing content at an anti-science organization. It’s an easy answer, it seems. She’d been raised a young earther and stuck to her beliefs. Purdom attended public school, she tells me, but she didn’t encounter “the whole millions of years thing” until high school. Even then, “I don’t remember really engaging in it or thinking that much about it.” In fact, she tells me, “it wasn’t taught that much.” It wasn’t until college that she began to engage with ideas of creation and evolution, she says, and she chose to attend Cedarville University, a religious university that teaches Young Earth Creationism. After graduating, she was accepted into a Ph.D. program at Ohio State, where her doctoral studies “focused on genetic regulation of factors important for bone remodeling,” her AiG bio says. Ohio State couldn’t have been a comfortable place for a Young Earth Creationist, I say. “I definitely had friends, and people I worked with every day,” she tells me, “but most of them weren’t Christians so you just didn’t develop those kinds of relationships. But I never really had any issues.” Besides, the research “didn’t have anything to do with how all of that got there,” she says. She isolated herself from the conversations. “That was a separate question. Once in a while, obviously, those types of conversations would come up among the graduate students, and even among professors with the students, but I knew enough not to get involved. I knew that if I stated what I believed there would definitely be prejudice against me, so I typically would just avoid those conversations, and not take part in them because I knew that it wasn’t going to go well for me.” After completing her Ph.D. in 2000, Purdom took a faculty position at Mt. Vernon Nazarene University, another religious school where Young Earth Creationism is embraced. While most tenure-track professors are

13

The Great American Eclipse

expected to have a vigorous publishing agenda, Purdom’s peer-reviewed work dropped off after Ohio State. The research wasn’t what she loved, she tells me. “The lab science was a way to get where I wanted to be, which was to be a professor at college, and I love teaching.” After six years at Mt. Vernon, she took a position with AiG as they launched the Creation Museum. It allowed her to focus on science education, and she has been prolific since, with 25 books and videos attributed to her in their bookstore, and dozens of articles in Young Earth magazines. “That’s where I’m more at home than in the pure research science,” she says. “You know, I like it, and I can do it, but this is my passion and my love.” Purdom is now focused on developing Young Earth resources for young children. “I really see my role and my expertise, and ministry, in helping them understand that science supports God’s word. It confirms it,” she says, so that as these kids “continue to get older, they don’t doubt, and they stay strong.” While Ken Ham gets the most press, Purdom is at the foundation of their educational outreach. She is Chair of AiG’s Editorial Review Board, which reviews everything they produce—dozens of books and videos each year, and she collects them into curriculum recommendations. She is also a speaker, visiting schools and churches to spread Young Earth Creationism from the perspective of a Ph.D.-holding scientist. She also co-hosts a twice-a-week Facebook Live program where she, Ham, and another AiG speaker discuss “science and cultural news.” As the only Ph.D. on stage, she is the sober one, pivoting when her co-hosts drift too overtly into hate as they mock homosexuality or climate science or universities. Purdom provides an air of legitimacy, acting as a symbolic link between outlandish comments and scientific competence. Her latest project, she tells me, is working with a newly hired education specialist, hired to develop summer camps and science workshops for younger kids. “I work a lot with her,” Purdom says, “trying to bring the museum to a whole other level in educating students.” Their educational programs are expanding rapidly and Purdom talks about the future as open and expansive. She’s excited for the future. * * *

14

BRICE PARTICELLI

It is 2:27pm and according to NASA’s tracker we are at exactly 91.9% solar eclipse. A sliver of sun peeks out as a tiny crescent above the moon. I get restless on the patio and decide to walk around. I head to the lagoon path where the crowd has grown. There’s a man with a box-viewing device and I ask if I can take a look. “It’s pretty low tech,” he laughs. It’s an oversized cereal box with two holes on top. One has a piece of tinfoil taped on, with a pinhole to let in light. I put my eye up to the other hole and look where the sunlight hits the cardboard—a fuzzy crescent of light in the dark. A few feet away, a couple stands beside a dog bowl filled with water, staring into it. I offer them my glasses. “You want to try ours?” the man asks. “It’s not as good.” There’s a leaf floating in the bowl. I ask him what they’re doing. “Just stand right here,” he says, holding my shoulders until I’m where he wants me, “and look into the bowl.” I do and I’m immediately blinded. He’s set me up to look at the sun through a reflection. I’m looking at the sun, but magnified through water. I jump away as quickly as I can. “Oh, I see what you’re doing.” “You just have to kind of squint a little,” he says. “I’m not sure that water makes it safer,” I tell them. I know it doesn’t, but I say it softly, and they don’t believe me. They hand me the glasses back and continue on, staring at the sun through squinted eyes. I walk away quickly, in fear of having to witness two people’s public blinding. I imagine others saying, “but you were with them. Why didn’t you stop them?” as the couple gets rushed out, bloody-eyed and screaming. Of course, it wouldn’t be that dramatic. Retinas don’t have pain receptors, so if we aren’t educated beforehand we don’t know that we’re hurting ourselves until it’s too late. In fact, Isaac Newton temporarily blinded himself during an eclipse. He watched it through a mirror and was blind for three days, then suffered from months of afterimage blurs. There wasn’t much literature on eclipse safety at the time, so maybe he didn’t have access, or he simply ignored what he read. Today there are studies, histories, advice columns, newscasts, and warning labels. We live in an age where information access isn’t an issue. We just have to listen to the right people.

The Great American Eclipse

15

In fact, I can’t help but look at this place and attribute its power to this increasing information access. Purdom was able to isolate herself growing up in a pre-internet age, sure, and her public school teachers clearly failed her, but the opportunity for this place to create that same ideological hardening in a new generation is only growing. The Creation Museum was launched at about the same time as the most popular social media sites, and the same year as the iPhone. Print-on-demand capabilities have sky-rocketed too, allowing anyone to print as many books as they can afford. Information and production access is generally a good thing, but it has also created hardened silos. All an organization needs is funding, and a good sense of the platforms that have cultural power. Mimic the structure and language and you can replace anything with your own ideology. Use the recognizable and symbolic aspects of museums or science education, for instance, and you don’t even need the science. You’ve got a “museum” that schools can fund trips to and buy classroom sets from. Or, of course, use the symbolic forms of “news,” and you can create your own reality. The mother and daughters on the stairs stand up. The eclipse has begun to wane and the mother says, “Let’s see if anyone else wants to see.” She and her daughters walk around, offering their glasses. When she’s thanked, she responds, “God be with you.” It’s a surprising scene. Hundreds of humans are scattered around the walkways, patios, and porches, all standing in tiny circles, looking to the sky. If you didn’t know what was going on, this would look like some strange silent ritual. Descriptions of eclipses before our current understanding vary. In Western Africa, the Batammaliba believed a solar eclipse was the sun and moon fighting. It was people’s job to encourage them to stop by resolving their own conflicts. In Viking lore, an eclipse happened when one of the two wolves who chased the sun across the sky caught it. In China, a dragon ate the sun. And for the Navajo, the sun died and was reborn. The time was spent indoors for prayer and contemplation on the balance of the natural world. It is human nature to explain the unexplainable with story, but today we know what an eclipse is. This knowledge allows us to consider the grandness of our cosmos—planets and stars and galaxies spinning around each other.

16

BRICE PARTICELLI

It is to consider our own planet, spinning on an axis every 23 hours and 56 minutes, our moon orbiting our planet every 27.3 days, and our planet orbiting our star every 365.25 days. For an eclipse to happen, these objects must line up perfectly above. But it is also to consider a bigger universe. It is our solar system, sitting on the outskirt arm of a swirling galaxy so wide that it takes 100,000 years for light to cross. It is to consider a universe in which our galaxy is one of 200 billion others within our observable universe. It is to consider the vastness of what we can’t observe, and to wonder how much more we might learn. It is a humbling existence, and an awesome thing to ponder as we watch our moon pass between us and our star. It is an overwhelming idea—our tiny home among such splendor. It is a beauty that is almost unimaginable.

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

17

Guest Column Something That Would Have Been Somebody: Abortion, Reproductive Justice, and Political Imagination BY ERIN GREER

Anne Sexton’s poem “The Abortion” repeats three times the phrase, “Somebody who should have been born / is gone.” My version is clunkier in both grammar and meaning: “Something that would have been somebody / will not.” * * * I did not realize I was pregnant until after more than three weeks of intermittent bleeding, moodiness, nausea and fatigue. My symptoms began at around the same time as Donald Trump’s inauguration, and everyone I knew in Berkeley, California, was moody, nauseated, and fatigued that January. I was busy attending political meetings, trying to finish my doctoral dissertation in English literature, and obsessing about the uncertain futures of my academic career and U.S. politics. For years, attempting to ignore my body has been my primary strategy of resisting the world’s insistence that it is the most important feature of my identity. But the primary reason my pregnancy took me by surprise, and intrigued the various medical personnel who would gather to watch my ultrasounds in the coming days, was that I’d had a copper IUD lodged in my uterus for two and a half years.

18

ERIN GREER

A night of especially hard bleeding finally prompted me to visit the student health center, where a blood test detected hormones suggesting I was six weeks pregnant. There was one OBGYN associated with my university’s student health center and she was on vacation that week, so I traveled to an affluent neighboring suburb for an urgent ultrasound two days later. IUD pregnancies have a heightened risk of miscarrying or being ectopic. I was hoping that I had miscarried – that the fetus had slipped out with the blood in my underwear, and that my partner Dan and I would not need to make a decision that had been a rather abstract and political proposition for me. As an abstract, political proposition, the right to abortion had seemed almost uninterestingly basic. Of course women must have control over this fundamental aspect of our reproductive labor in order to approach having social equality. And yet, I was unable to sleep, or read, or carry on with ordinary life following that first blood test. In my head were images from the Life Magazine “Drama of Life Before Birth” photo-essay, in which serene fetuses float in a uterine sublime. I heard, on a loop, Hillary Clinton’s description of abortion as a “sad, even tragic choice.” Silence shrouds the procedure, which ends close to twenty percent of all pregnancies each year in the US, according to the Guttmacher Institute. The rate of abortion, by the way, declined between 2009 and 2016, most likely due to increased family planning resources—particularly IUDs and other “long-acting reversible contraceptives”—provided through the Affordable Care Act and by organizations such as Planned Parenthood. The political is personal. The waiting room at the suburban clinic increased my anxiety and disorientation. It was bright and cheerful, with coral carpeting, turquois upholstery, tables strewn with pregnancy magazines and a basket of children’s toys in one corner. Stylish receptionists sat behind a concierge desk. A woman wearing some sort of pregnancy yoga outfit sat across from me, tapping on her iPhone and smiling at everyone who passed by. I had dropped in on another life I might have lived. A nurse eventually led me to an examination room, where I was weighed and instructed to remove my pants. Two women entered: the nurse practitioner I was scheduled to see, and an OBGYN, who had a lull between patients and was curious about the IUD pregnancy. They directed a transvaginal ultrasound wand into my vagina and peered together at the

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

19

images it produced on a screen. “Oh yes, there’s the baby,” they said. “You said you were six weeks along? More like ten… And that – that might be the IUD.” Their eyes were bright with interest as they looked at each other and then at me. “Do you want to be pregnant?” one of them asked. “I have an IUD,” I said. “Well, if you don’t want to be pregnant, that makes things easier.” They explained that I could choose to carry the pregnancy to term, but the risks would be higher for me and the baby. I fixated on their use of the word “baby,” instead of “fetus,” waging a silent protest to prevent myself from breaking down in front of them. They told me that their healthcare network’s “scheduler” would book me an appointment for something that sounded like a “DNC.” I didn’t ask any questions, eager for them to leave the room before I lost control of the tears rising with a hot flush into my eyes. Several hours of Googling that night informed me, among other things, that they had said D and C: dilation and curettage, wherein my cervix would be dilated and everything in my uterus scraped out with a curette. The scheduler booked me for a D and C in a hospital, which I learned would cost me between $1500 and $3000, after insurance. This was more than I earned in a month through teaching. I spent a panicked, confused, and lonely day on and off the telephone, trying to learn if it was necessary for me to have the abortion in a hospital (it was not), and whether I could get an appointment at a non-hospital clinic instead. The nearest Planned Parenthoods were overbooked for at least a week and a half, but a local clinic in Oakland would be able to see me early the following week. Dan flew to California from Rhode Island, where he is in graduate school. He bought the ticket the day I called him in tears from the sidewalk outside the suburban clinic, and by the time he arrived, I felt a bit remorseful about the expense. The despair and sorrow I’d initially felt had given way to uneasy impatience, an eagerness to be beyond the period of this “choice.” The abortion clinic had two waiting rooms: the first was large and cramped, lined wall to wall with dingy grey chairs that were filled with young women and a few men. There were no magazines. The receptionist sat behind a protective plastic wall.

20

ERIN GREER

The second waiting room was for patients who had completed paperwork, given more blood, had another ultrasound, and spent some time in a counseling room featuring posters that recommended various forms of birth control, especially IUDs. The room was windowless, dimly lit by two lamps and a boxy television suspended in the center of one wall, on which a VHS of the film Finding Forester played. There was a young woman wrapped in a blanket sitting alone when I arrived; slowly, more women wearing hospital gowns joined us. Someone remarked about how chilly the room was. Someone else articulated the weirdness of the movie selection. Soon the six of us were in conversation. By the time I was called for my abortion, I had learned that two of the women were married, four had children already, and two had been blown off via text message by the men who had impregnated them. The youngest was nineteen, the oldest, probably in her early forties. Two women had had experiences with racist mothers-in-law. A Filipina woman, for instance, had a mother-in-law who had informed the woman’s husband that she didn’t want any “Asian grand-babies.” Filipinos, the mother-in-law believed, were dirty. This was not the only reason she was there awaiting an abortion, but, along with financial insecurity and existing caregiving obligations, it was among the reasons. I was the only white woman. In fact, aside from the surgeon, the anesthesiologist, and a few nurses, Dan and I were the only white people in the clinic that day. * * * The “reproductive rights” movement in the US has a problem with race. Its historical emphasis on “choice” has suppressed not only the correspondences between race and class that contour how freely a person chooses anything in life, but also the deeply racist historical intertwining of abortion, sterilization, and non-whiteness. “Black women have been aborting themselves since the earliest days of slavery,” Angela Davis has reminded us; “most of these women, no doubt, would have expressed their deepest resentment had someone hailed their abortions as a stepping stone toward freedom.”

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

21

The anti-abortion lobby originally arose in order to prevent white women from aborting. Until the late 19th century, abortion was somewhat routine in the U.S., often performed by midwives and considered permissible by religious and legal authorities until the time of “quickening,” or fetal movement. Objections were raised not because of moral concerns about the fates of fetuses, but because of xenophobic concerns about immigrants out-reproducing white people. Here is Dr. Horatio Storer, president of the newly formed American Medical Association, in 1867: “—Shall the [U.S.] be filled by our own children or by those of aliens? This is a question that our own women must answer; upon their loins depends the future destiny of the nation.” The AMA’s lobby for outlawing abortion is generally viewed as part of a broader effort to gain control over the practice of medicine, restricting the work of midwives, spiritual healers, and quacks. In other words, the reproductive freedom of women in the U.S. has always intersected with financial and racial interests, as well as (for better and worse) the tension between standardizing healthcare and upholding individual autonomy. Its conflict with religious interests began in the 20th century. Historically, mainstream US feminism has underappreciated the thread that traces from self-abortions by slaves, through patriarchal white nationalism, through forced eugenics-inspired sterilizations, through “elective” sterilizations freely provided by a State that would not provide free abortions or childcare. Winthrop Stoddard, a eugenics theorist from Harvard who authored The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy, was given a board seat in the activist organization founded by Margaret Sanger, the American Birth Control League. Sanger herself, once a radical socialist inspired by her nursing experience among the working poor to recognize the devastating convergence of economic exploitation and involuntary parenthood, gradually warmed to eugenicist rhetoric of population control: “dishygenic groups,” she said in a radio address—such as “morons, mental defectives, epileptics, illiterates, paupers, unemployables, criminals, prostitutes and dope fiends”—ought to be offered the “choice of segregation or sterilization.” Even if we temper our appraisal of Sanger with an awareness that such views were common in the early decades of the twentieth century—and considered idealistic and humane—it is worth remembering the historic links between reproductive freedom

22

ERIN GREER

and judgements about which lives are worth reproducing: judgments that in turn help to reproduce the unequal conditions of many lives. Forced or coerced sterilizations occurred throughout the abortion battle years of the 1960s and 1970s, and this reproductive injustice was largely overlooked by national feminist movements, in spite of arguments by women of color. Often, sterilizations against women of color and poor white women were carried out under the auspices of reducing the State’s welfare liabilities. According to estimates drawn from interviews and surveys conducted by Native doctors and judges, between 25-42% of Native American women of childbearing age had been sterilized by the mid-1970s, many of them without fully understanding the permanence of a procedure they were strongly encouraged to undergo. A Government Accountability Office investigation of the Indian Health Service found systemic violations of policies developed to ensure informed consent before sterilization. Sterilization rates remain significantly higher among women of color and poor women of all races; a recent study published in Social Science Research, which attempts to factor in rates at which sterilized women experience regret, offers the tentatively worded assessment that “the higher sterilization rates among some racially marginalized groups may reflect stratified reproduction rather than differential preferences.” Planned Parenthood is the current name of the organization Sanger founded. I unhesitatingly support Planned Parenthood, which continues to provide essential reproductive healthcare and education to millions of women. The history of reproductive injustice does not mean that either abortion or elective sterilization constitutes racial genocide. But as I was sitting in the windowless room awaiting my abortion under the gaze of Sean Connery, I was dismayed by what appeared to be one contemporary face of eugenics. To be sure, my minority status in that room was also a sign of segregation in healthcare; but abortion rates remain notably higher among low-income women and women of color. An individual woman’s decision to abort a pregnancy, like the conditions leading to the involuntary pregnancy itself, is shaped by social inequality that has intensified even as feminism has gone mainstream.

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

23

* * * Back in January 2017, when I didn’t know I was pregnant, I started reading Maggie Nelson’s book about queer family-making and poetry, The Argonauts. Among many things, the book charts Nelson’s experiences of pregnancy via IVF and motherhood in parallel to her partner’s physical and psychological responses to testosterone injections. The book’s narrative trajectory follows a fairly straight course from love, to marriage, to baby carriage, while also producing a lyrical and theoretical surplus, reflections about queerness, desire, poetry, parenting, academia, and politics. I accidentally left the book at Dan’s house in Rhode Island, unfinished, when I returned to California at the beginning of the spring semester. He brought my copy with him when he flew out in late February to be with me during the abortion, and I began reading again from the beginning. Nelson describes pregnancy as “inherently queer,” an experience of “radical intimacy with – and radical alienation from – one’s body.” Alienation I definitely felt. Intimacy – from the Latin intus: within – is not the word I would choose, but in the days between learning I was pregnant and getting the abortion, I certainly felt a new, astounded curiosity about things taking place within me. I looked frequently at my belly in the mirror and held my aching, swollen breasts in my hands, wondering what hidden processes were causing these pains and inflations. I had been feeling crampy and bloated for weeks, but the feelings seemed entirely new after their source was revealed to be a distinct organism growing within my body. Somewhere past the page at which I’d left off in January, I read: “Never in my life have I felt more prochoice than when I was pregnant. And never in my life have I understood more thoroughly, and been more excited about, a life that began at conception. Feminists may never make a bumper sticker that says IT’S A CHOICE AND A CHILD, but of course that’s what it is, and we know it.” I had no such “understanding” while I was pregnant. Here are the things I understood, the thoughts circulating overhead as I stood, and walked, and held office hours with my students, and attended meetings of the university’s student-workers’ union, and stared at my dissertation on my computer screen, and lay in bed without sleeping for hours: Inside

24

ERIN GREER

me was an organism that was not yet capable of surviving independently of me, but which could potentially become so, and more. Inside me was an organism (not, in my view, a “life”) scripted by a remix of my DNA and that of a man I love, who would (or perhaps will) be a generous, loving, caring and liberating father, as he is a partner. Dan, incidentally, has always wanted the opportunity to be such a father, whereas I never even imagined parenthood before we met. Inside me was a possible resolution to this discrepancy in our ideas about the future, an organism—not a child—that could develop into a person who would transform not only our two lives, but also the lives of my parents and step-parents, my aunt, Dan’s parents, his sister, our friends, and countless, fathomless others born and not-yet-born. This could be the conception of so much, I understood. And it might have been, if we’d had more assurance about the future. Nelson continues, about pro-choicers, “We understand the stakes. Sometimes we choose death.” I guess that’s not incorrect. What precisely has died, however, in order that other possibilities may live, will never be known. And every time a heterosexual pair uses a condom or an IUD or a pill, patch, rod, fertility charting app, etc., a similar unknowable transaction takes place. One future is substituted for another. But of course the decision to abort my pregnancy did not feel the same as the decision to have an IUD placed in my uterus. Nor was the choice for the abortion as logistically and financially simple as less controversial forms of birth control, which should perhaps be called pregnancy control. Abortion is birth control, in the form of negation. I don’t know when personhood begins, when an organism with human DNA gains ethical, moral dimensions. Interdisciplinary uncertainty on this question was in fact a rationale cited in Justice Blackmun’s Roe v. Wade decision: “When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus [about when personhood begins], the judiciary, at this point in the development of man’s knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer.” It is strange that the futures of so many women – or, from another perspective, the negated futures of so many somethings – hang on a lack of consensus among men trained in philosophy, medicine, and theology. In a way, my now-unpregnant body embodies interdisciplinary impasse.

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

25

As Nelson’s reflections indicate, a sort of life begins at conception from the perspective of any person who wants to be a parent and already loves the imagined future child. Women who have miscarried rightly object to certain strands of feminist rhetoric, which can intensify the difficulty of losing a fetus. As Alexandra Kimball has written of coping with her miscarriage, “If a fetus is not meaningfully alive, if it is just a collection of cells – the cornerstone claim of the pro-choice movement – what does it mean to miscarry one? Admitting my grief meant seeing myself as a bereft mother, and my fetus as a dead child – which meant adopting exactly the language that the anti-choice movement uses to claim abortion is murder.” Kimball remains a feminist, although she found that feminist theory had “nothing to say” to help her understand the loss of her unborn child. She also points out that feminist theory and activism have ignored the “socio-sexual crisis” of the ways miscarriages are handled by the medical establishment, such as “the still-standard practice of having untrained ultrasound technicians inform women of their miscarriages, or admitting women who’ve had stillbirths into maternity wards.” Kimball herself had an abortion years before her miscarriage, and in her essay she reaches a conclusion that strikes me as true and appropriately moderate, but still incompatible with the religious views of most who oppose abortion: “the personhood of the prawns we carry is a result of our relationship with our own pregnancies. Unlike the aborted fetus, the miscarried child has been spoken to, fantasized about, maybe even greeted on an ultrasound or named.” * * * Like many feminists, my unease with abortion rhetoric stems more from the language of “choice” than that of “collection of cells,” and not only because choice makes an uninspiring and misleading contrast with “life.” An obsession with individual choice broadly distributed throughout our culture is, in fact, at the roots of my ambivalence about bringing a person into the world at this time. Legal scholar Robin West argues that the logic of privacy and choice, shared by the Roe v. Wade decision and the rhetoric of the pro-

26

ERIN GREER

choice movement, implies parenting itself is a lifestyle “choice” similar to decisions like buying a sailboat or enrolling in graduate school. We assess our individual tastes and desires and resources, and then we choose, living with long-term consequences that quite reasonably fall on us alone. This logic, in other words, legitimizes the U.S.’s uniquely thin provision of public goods, which itself is usually explained as a protection of individual (consumer) choice in realms such as healthcare, education, and housing. “There is no further reason to help a poor mother […] than there is to help a would-be recreational sailor buy a boat that will allow him to sail around the world.” We have, West argues, “render[ed] parenting a market commodity.” The rhetoric of choice implicitly separates the preservation or termination of a pregnancy, as a private decision, from the conditions in which a potential child would grow up. I honestly don’t know if Dan and I would have decided to keep the pregnancy if we had felt more confident about the life the potential child would have had. Undoubtedly, our conversations that difficult week we discovered I was pregnant would have been different had we not both been in school and in debt, or if we’d been certain we’d have sufficient paternity leave and the potential child would have healthcare and a good home, community, and schools. I can imagine us having decided differently, and this act of imagination fills me not with regret, but with a kind of stillness. It’s like a mental shrug in a minor key: an ambivalence hovering between tentative desire and wariness, attachment (or possibly commitment) to the balance of friendship, love, intellectual and political work I’ve struck, reinforced by misgivings about our collective future. I realize, of course, that people in much more difficult situations than ours make it work. But for many people, things work rather badly. A focus on individual choice tends to obscure the series of collective choices that have brought us here. Since the 1990s, activists and scholars led by women of color have supplemented the reproductive rights and health frameworks with that of reproductive justice. Loretta Ross, one of the original women to develop the concept, has explained that a reproductive justice framework moves “beyond a demand for privacy and respect for individual decision making to include the social supports necessary for our individual decisions to be optimally realized.” It encompasses “issues of economic justice, the

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

27

environment, immigrants’ rights, disability rights, discrimination based on race and sexual orientation, and a host of other community-centered concerns.” Legal abortion is absolutely necessary for people with uteruses to claim equal social status. But we have work to do if we want this choice to align with something more like freedom. * * * Two conversations with my dad started running through my head when I learned I was pregnant. One of them took place on the deck at my childhood home in the Midwest, where he and I periodically smoke cigars, drink scotch, and trace the approaches and divergences of our ideas. He told me in this conversation that he would not choose to have children now, were he and my stepmother of the relevant age. Climate catastrophe was the main reason, because he believes most other social issues are solvable with time and effort. But he thinks the cascading effects of climate change make the procreation gamble a bit irresponsible: resource shortages, migration crises as shorelines disappear and new deserts take shape, a likely increase in violence and civil wars… what world might children born today live to see at the end of the century? My dad is a step-grandfather, and he fills the role beautifully. He takes my step-nieces and nephews tromping through the woods near our house, sharing knowledge he’s gained since retirement of the local trees. He tells elaborate stories in which children that resemble them have adventures with animal sidekicks. He told me similar stories when I was young: we would sit together in his velvety, ragged blue reclining chair, my body leaning against his belly, which rocked with his words as he described Erin Greckle, a six-year-old living in the woods in Canada, and her friends Hungry, a mouse, Prince, a pony, and Prickly, a porcupine. During a previous conversation on the deck, my dad had confessed that he sometimes worried he and my mom had raised me in too “gender-neutral” a way. I had been recounting stories that I thought were humorous from my most recent dating misadventures. He said – to put a finer point on the matter than he did at the time – that he was worried he and my mom had failed to socialize me adequately to patriarchy.

28

ERIN GREER

I understood many things along with his words: that he loved me and was not sure how best to prepare a woman for happiness in a sexist society that he could not singlehandedly change; that he understood at least a significant portion of happiness to issue from heterosexual domesticity; that he was happy in his own heterosexual domesticity, a third marriage that had seemed unlikely when he and my mother divorced. He had spent a few years muttering about “old dogs” resistant to the “new tricks” of cohabiting with another person, as well as the lies that (he then maintained) sustain romantic ideology. In his admission, I also heard a hope that I would settle into a lifestyle normatively recognizable as happiness, which I took to mean marriage, property ownership, children, gardening, and a car of my own. I don’t remember what I said in response, but it was probably a cranky retort about accommodationism and complicity. I was thinking, with the hyperbole that still sometimes comes over me when I’m visiting Indiana, that vision of happiness is bogus: it rests on exploitation, conformity, and a false view of love as a scarce and fixed resource. I wanted community, collectivity, love unbounded by state recognition and property rights. And I could not imagine giving birth to, or raising, children. My dad has grown more radical in his retirement. His own bootstraps-autobiography no longer convinces him of absolute American meritocracy, as he sees the significance of his whiteness, his masculinity, and the fact that his childhood poverty was situated amidst middle class prosperity, safe sidewalks, and decent schools. His father died when he was seven years old, and his mother got a low paying job bagging groceries to support herself and her three children. Dad and his siblings wore ill-fitting, threadbare clothes donated by the Pentecostal church that he resentfully attended at least four times a week. But his escape was a library, not a gang, and he now sees that this was more a matter of luck than inherent virtue. So I was interested, but not quite shocked, when he told me that he does not think it makes ethical sense to bring children into the world. Kids don’t consent to being born, he says. And particularly now, parents regardless of class cannot guarantee more than the love evolution seems to ensure. While only partially sharing his reservations about the ethics and politics of bringing children into this world, I was relieved to know

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

29

that if I don’t have children, he will not mourn grandchildren that never came into being. The second conversation running through my head in the days surrounding my abortion took place shortly after Trump’s election, as my father speculated that his sister had voted for Trump because of her strenuous opposition to abortion. My 77-year-old aunt has, for twenty years, hidden from their mother the fact that she has pierced ears, because this is a sin according to my grandmother’s more stringent version of Pentecostalism. My dad suspects that one of the reasons my aunt so frequently turns down his invitations to family celebrations is that she knows people will be drinking alcohol at them: another sin. Church, and the uncompromising God she finds there, have been among the most consistent things in her life across bad marriages, fluctuating employment, and debts incurred thanks in part to the bad marriages. Abortion is one of the primary issues through which the neoconservative-neoliberal alliance of the modern Republican Party has been forged. Both neoliberals and neoconservatives have reasons to resist the breakdown of the “traditional” family. The former could do without the latter’s moralizing, but as political scientist Melinda Cooper has explained, they nonetheless “wish to reestablish the private family as the primary source of economic security and a comprehensive alternative to the welfare state.” The Right has been selective in the religious sentiments it stokes: stern moralism and protestant individualism—within hierarchies—are encouraged, but not the forgiving pseudo-socialism of Jesus Christ. Material prosperity, like salvation, is framed as the result of individual effort and grace. In this alliance, it is less contradictory than sometimes assumed for women like my aunt—working class all her life, and mostly satisfied with what she has earned—to support the Republican Party. * * * The issue of abortion quite dramatically marks the limitations of the ideal of a liberal, deliberative democracy. It is not possible for rational discussion to close the gap between someone who believes that personhood begins at conception and someone who does not. It is not

30

ERIN GREER

possible for evidence-based argumentation to establish the meaning of personhood. But in this moment of deeply fractured U.S. political life, it feels to me as though abortion is more than a sign of democratic liberalism’s limitations—it feels as though the “abortion wars” are a synecdoche of deep problems in the U.S. political project. Liberal philosophy strives to exclude religiously founded views from the “overlapping consensus” that (in the philosopher John Rawls’ words) constitutes the political sphere. But simply excluding such views does not, as we have seen, resolve the disagreement. The exclusion instead makes some who hold these views into extremists, because they realize they are not part of the political community and therefore are not invested in working within it. Why not bomb clinics (or hijack airplanes or drive your car into antifascist protestors), if one is an exile whose point of view is (or is perceived to be) ontologically excluded from the space of political power? Rawls argues that “fundamentalist religious doctrines” are directly in contradiction with “the idea of public reason and deliberative democracy” and must therefore be excluded from liberal politics: “[Such doctrines] assert that the religiously true, or the philosophically true, overrides the politically reasonable. We [liberals] simply say that such a doctrine is politically unreasonable. Within political liberalism nothing more need be said.” Quoting this passage from The Idea of Public Reason Revisited, the political philosopher Linda Zerilli responds with the eminently reasonable observation, “But of course a lot more needs to be said—that is, if we are not to satisfy ourselves with talking publicly to people who are already part of the charmed circle of the reasonable and instead try to engage points of view that trouble our very understanding of the reasonable. And isn’t this the real political challenge that faces us today?” Zerilli turns for guidance to the philosopher who seems to me to provide the best intellectual signposts by which to navigate contemporary politics: Hannah Arendt. With traditional liberal theorists of the “public sphere” like John Stuart Mill, Jürgen Habermas, and John Rawls, Arendt views public life as a collaborative discursive project: we meet with others and talk to each other, and out of this conversation, our shared sense of the world takes shape. But unlike Mill, Habermas, and others of the liberal

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

31

tradition, Arendt does not focus on the “communicative rationality” cultivated by such talk, nor does she structure her account around the concept of a “marketplace of ideas,” in which freedom of speech is governed only by the competitive law of reason. For Arendt, the central ambition of talking with others in public is epistemological, not rational. Through conversation with others, we learn to look at the world from new perspectives, and more fundamentally, we learn that the world is always available to multiple, frequently conflicting, perspectives. When public life is functioning as befits a democracy, our “incessant talk” teaches us “that the world we have in common is usually regarded from an infinite number of different standpoints, to which correspond the most diverse points of view.” Like the ancient Greeks who figuratively model such democratic conversation for Arendt, we learn “to see the same in very different and frequently opposing aspects.” Only after we have established that we share such common ground can we begin the deliberative work of politics. Arendt’s ideal of public life evokes two meanings of the word “conversation.” People gather in public and talk to each other, making conversation in the ordinary sense of the word: they express how their world looks to them, describing the world as it has been filtered by their sets of experiences, their knowledge, desires, assumptions, and habits. In its orientation toward the world seen together yet differently, this “conversation” recalls the original sense of the word, which is compounded of the Latin roots for turning—vertere—and togetherness—com. Turning together, and telling each other what we perceive of the world, a public co-constructs the world in which we meet. The act of perceiving becomes collective and creative when combined with speech. At the end of her life, Arendt turned her focus from the epistemological to the aesthetic constitution of public life. Political judgment, she indicates, is similar to aesthetic judgment. She died before fully articulating her philosophy of political judgment, but lectures and notes from late in her life provide a blueprint that speaks to our present partisan impasses. She argues that a person’s conviction that a thing is “right” or “just” means that she understands it to be universally right or just, just as (according to Immanuel Kant) her conviction that a thing is “beautiful” means that she understands it to be beautiful for everyone. When interacting

32

ERIN GREER

with the world, we distinguish between objects and experiences that are pleasing to our senses, and objects and experiences that seem to evoke a more transcendent response. If I say that I like wearing hiking boots around town, I’m making a modest and uncontroversial claim about my personal preferences. If, however, I say that my hiking boots are beautiful, something seems discordant. It’s as though I’m claiming something about the boots that would encompass other peoples’ responses to them. In Kant’s terminology, I am invoking the sensus communis when I judge the boots to be beautiful: everyone who sees these boots will, I suggest, tap into the same “common sense” and feel equally moved. This “common sense” is what Kant calls “preconceptual,” an impulse of understanding and not the product of deductive reasoning. If you regard me skeptically when I tell you my boots are beautiful, I will not offer you logical proofs, but rather I will show you the boots again and say, don’t you see? When we apply this model of judgment to politics, the impasse of partisan disputation appears to follow less from rational obtuseness than from a more deeply rooted, preconceptual disagreement: an impulsive disagreement we feel more powerfully and prior to logic and reason. Those who disagree over political issues effectively perceive different objects. It is a baby or a fetus; it is murder or autonomy. Discussion alone cannot close the gap, and as long as we insist the other perspective is simply wrong, we have lost touch with the “world we have in common.” Perhaps in this way I must agree with Maggie Nelson, after all: it’s a child and a choice. How does a person recover the world held in common with those whose views are in extreme conflict with her own? Arendt’s recommendation is immediately appealing: “To think with the enlarged mentality”—this phrase recalls Kant’s description of aesthetic judgment—“that means you train your imagination to go visiting.” She is careful to stipulate that this “visiting imagination” is not equivalent to empathy. She describes “an enormously enlarged empathy” as a patchwork of personal feelings and prejudices unhelpful for deliberative politics. It would not be helpful for me to send my imagination into the hypothetical perspective of a person who believes abortion is murder, nor for me to spend a few imaginative hours on Incel Reddit or 4chan. Two years after my abortion, I could stomach the results of a search for the word

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

33

“abortion” in such places, but I doubt this would “enlarge” my mentality. Aesthetic judgment again provides a partial model: our imaginative travel is to be undertaken in a disinterested state of mind, and it should carry us to disinterested positions different from our own. If my hiking boots are beautiful, the aesthetic pleasure I take in them is disinterested in the sense that it is distinct from their usefulness to me on a trail. An anti-feminist, or a person convinced that life begins at conception, is not “disinterested” in the matter of abortion. (But then, who is? I will return to this problem.) In the essay “Truth and Politics,” Arendt explains that I should strive to imagine “being and thinking in my own identity where actually I am not.” She argues that I should imagine myself in different “standpoints,” bearing these alternative positions “in my mind while I am pondering a given issue,” which will enable me to “imagine how I would feel and think if I were in their place.” This is what she calls “representative thinking,” because imagination enables us to represent the perspectives of others; these perspectives, moreover, should be as disinterested as possible. This act of imaginative projection would undoubtedly improve upon many of our most dysfunctional political debates (and it would reveal political lobbying to be a contradiction in terms). But I see a few problems. Identity markers such as class, gender, and race, in this time and place, deeply influence subjective experience and the formation of judgment. If I were suddenly parachuted into a different position—say that of extreme wealth or extreme poverty—the things I would perceive from that position would most likely be different in significant ways from the things I would perceive had my standpoint been shaped from childhood by extreme wealth or poverty. Another problem—the problem at the heart of the political world in which this essay is written—is the impossibility of imagining myself inhabiting positions that are preconceptually antithetical to my own. Standpoints that I can imagine, however imperfectly, mark differences in wealth and status, geographic and even historical context. But many political standpoints are constituted through preconceptual beliefs like those expressed in theories of “ensoulment,” or views of the biology of race or gender. Differences in these types of standpoints cannot be traveled between with a disinterested yet intact personal identity. I can imagine standing in a church, but without empathetic projection and leaving my

34

ERIN GREER

own identity behind, I cannot imagine believing in the immaculate conception of Jesus Christ. Is empathy necessary after all, in order to regain a common world? This cul de sac may explain Arendt’s dogmatic insistence on the separation between public, private, and social realms, which ends up bearing some resemblance to liberalism’s marking of boundaries via secular reason. On the logic of this separation, Arendt distanced herself from civil rights struggles. For instance, she described schooling as a “social” rather than public (that is, political) issue, which meant that segregation driven by prejudice must be permitted, even if abhorred. Linda Zerilli’s response to Arendt’s strict delineation of realms is one that I share: her schema of public, private, and social life should be evaluated separately from her description of the political mode of judgment, which does not predetermine what we consider to be political. Yet, the question of what an embryo is, so important to abortion debates, cannot be “judged” in the manner she describes, by projecting one’s own mind, stripped of personal interest, into another standpoint. Arendt’s advice that we “train the imagination to go visiting” implies a more robust and responsible notion of citizenship than is implied in an abstract call for “freedom of speech”—we are enjoined to do a particularly rigorous and generous kind of work before speaking in public––but the prescription cannot help resolve certain fundamental political difficulties. Still, I find her account of political “reality” as a composite of perspectives extremely helpful. Even if we cannot vividly imagine each perspective, we can bear them in mind, acknowledge their existence and constitutive power. As a political “object,” for now, abortion is murder and it is freedom; abortion is an ambivalent necessity in the pursuit of gender equality; abortion is birth control; abortion is political leverage; abortion is tragic and abortion is ordinary. To repurpose a famous line by Wittgenstein, the meaning of a political issue is its composite uses in a culture. Meanings change over time. We can try to persuade others to share our sense of an issue’s meaning by describing how we see it, but we are unlikely to compel them via logical proof, and imaginative travel abides certain restrictions. In The Human Condition, Arendt describes another principle of public life that strikes me as a feature both urgently needed in and utterly

Something That Would Have Been Somebody

35

excluded from our contemporary political scene: forgiveness. She writes that speech and action, the components of public and political life, share two crucial characteristics: both lead to unpredictable consequences, and both are irreversible. Therefore, she argues, our political lives require two additional practices: promise-making and forgiving. If we are to live together and bear the risks that go along with speaking and acting in public, we must be able to assure each other of the seriousness of our intentions via promising, and we must also know that our own mistakes—or the unintended consequences of our well-intended actions—can be repaired. Forgiveness is necessary in order for a community to hold together. The hard work of democracy—of exposing your view of the world, being open and responsive to others who challenge it, and acting with them to change the world held in common—will not always go smoothly. There will be disagreements and mistakes, and there will be occasions of starting over again, trying new ways of speaking and acting and building the world together. In addition to helping us take risks and start over again when necessary, forgiveness might help us enter into the presence of those with whom we deeply, preconceptually, disagree. I would not apologize to someone who believes I committed a sin in aborting my unplanned pregnancy, nor would such a person be likely to seek my forgiveness for bullying women on their way to clinics or campaigning to make abortion illegal. Each of us would continue to see the other as dangerous and acting against our understandings of life and justice. I can’t imagine reaching a consensus about the essence of personhood. But I can imagine meeting in public and talking—the first step of founding a world for politics—if I knew that this person would meet me without hatred, and if I believed she, he, or they would acknowledge that abortion can also be viewed from my standpoint. I don’t have sappy hopes that such a face-to-face conversation would end our disagreement and renew democracy. But I also don’t see any better route to take. Forgiveness is different from tolerance, a liberal byword, in that it signifies a much more significant breach and a willingness to attempt political action in spite of this breach. Whereas liberal tolerance would treat the issue of abortion as a private matter—what I do in private, and what you believe in private, are not suited for the public realm—forgiveness

36

ERIN GREER