'Look into a flower, and what do you see?

Into the very heart of nature’s double nature — that is, the contending energies of creation and dissolution, the spiring toward complex form and the tidal pull away from it. Apollo and Dionysus were names the Greeks gave to these two faces of nature, and nowhere in nature is their contest as plain or as poignant as it is in the beauty of a flower and its rapid passing. There, the achievement of order against all odds and its blithe abandonment. There, the perfection of art and the blind flux of nature. There, somehow, both transcendence and necessity. Could that be it — right there, in a flower — the meaning of life?'

Emily Dickinson

OF RUINS

OF RUINS

“From the root, the sap rises up into the artist, flows through him, flows to his eye. Overwhelmed and activated by the force of the current, he conveys his vision into his work. And yet, standing at his appointed place as the trunk of the tree, he does nothing other than gather and pass on what rises from the depths. He neither serves nor commands, he transmits. His position is humble. And the beauty of his crown is not his own; it has merely passed through him.”

Paul KleeOne day there will be books written about art of the pandemic. They will note the surge of self-portraits. They will explore the impact of introspection, and perhaps they will also celebrate the flowering of a stubborn new breed of creativity. Persisting like a weed through a cracked pavement, the desire to find liberty inside suppression and movement within stasis permeated the dawn of this decade. In that space, the still life and the interior have regained ground. The idea of “going within” is not new to Joshua Yeldham. His landscapes are as psychological as they are physical. His line goes off-road from figurative convention and his mediums bleed into each other, often within a single work paper, paint, wood and canvas will meet. But no matter how vast their scale, even his most ambitious triptychs and murals possess a containment. A frailty. Almost a secrecy.

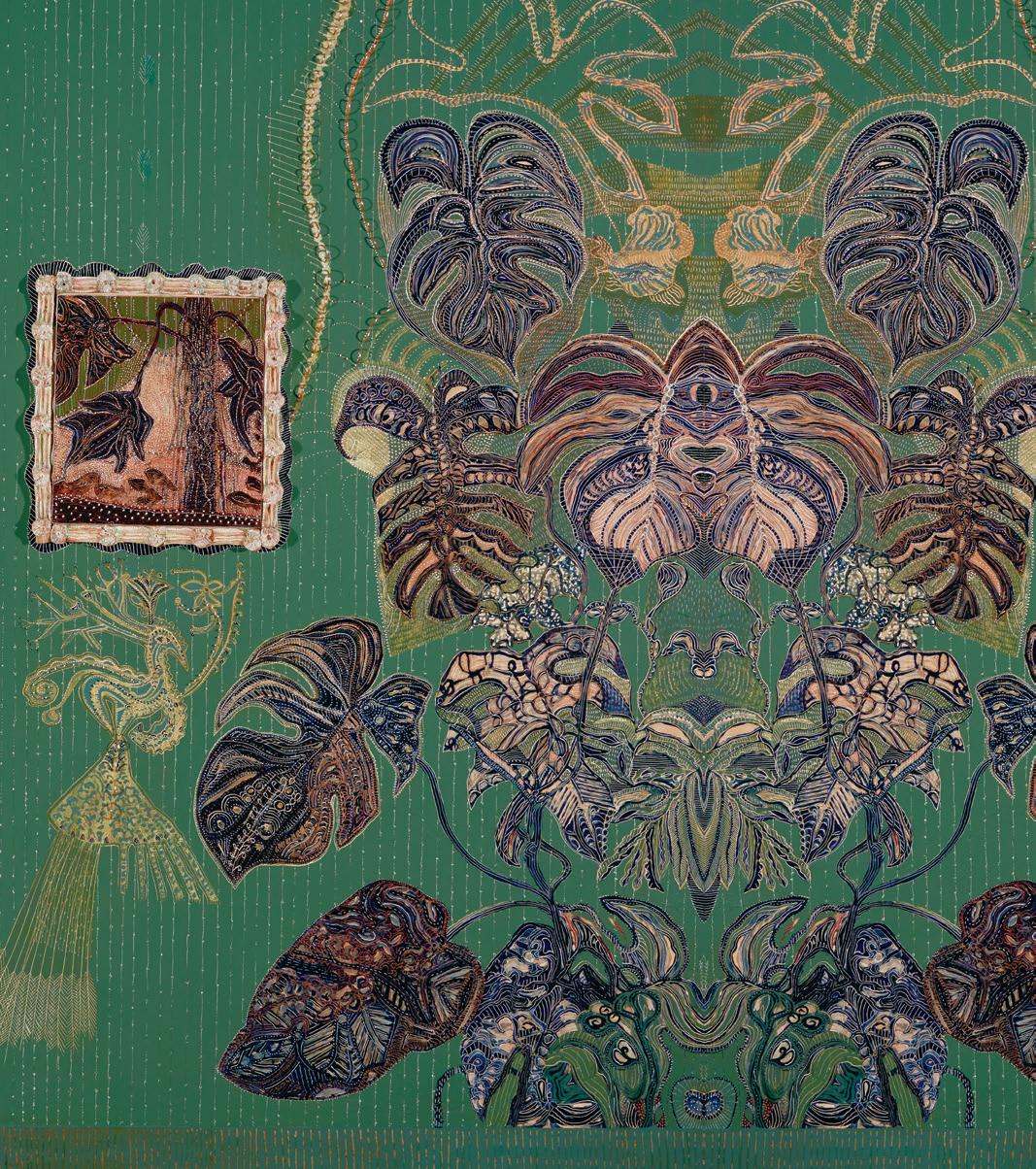

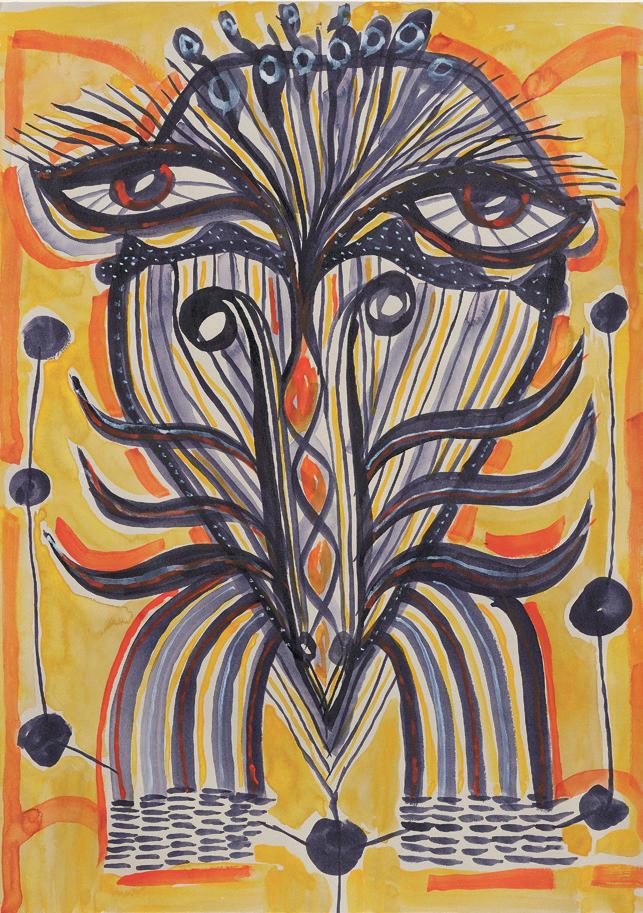

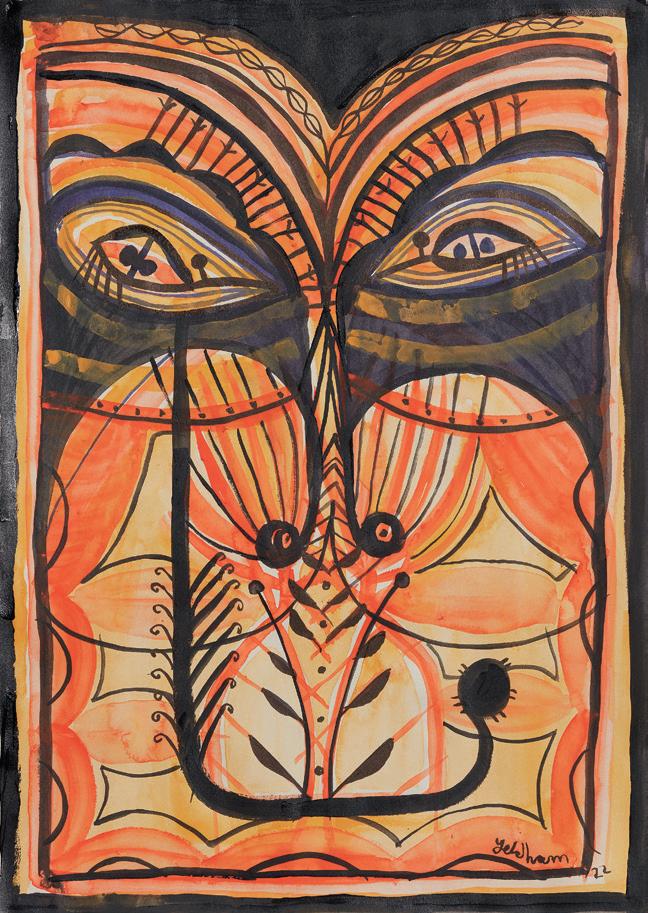

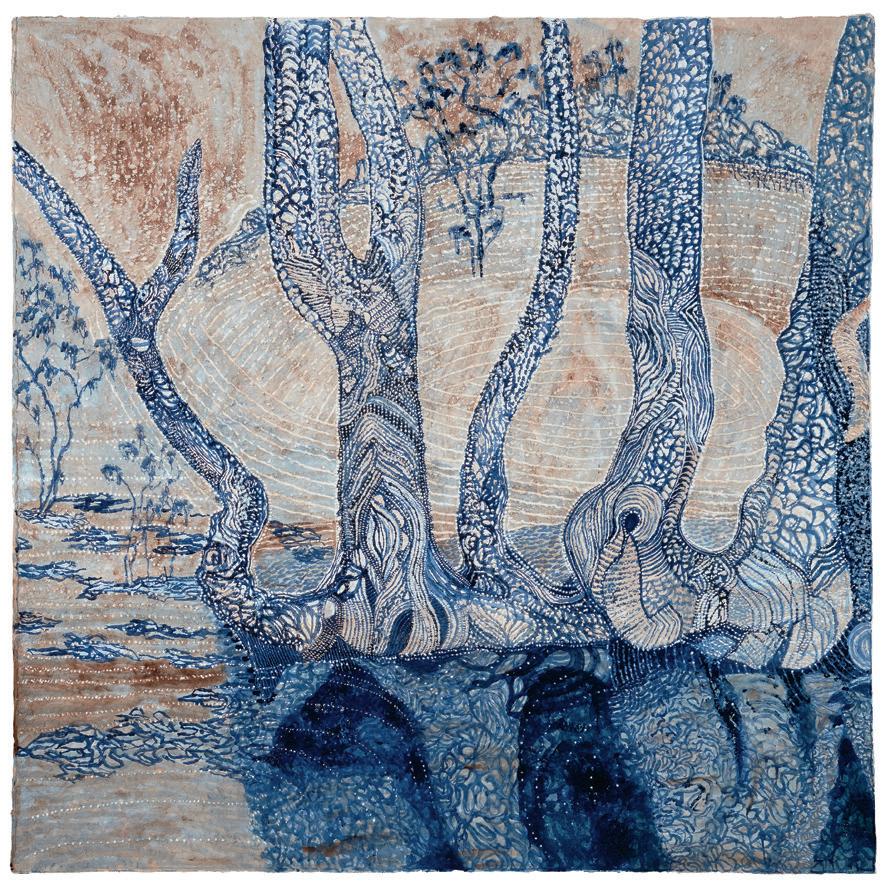

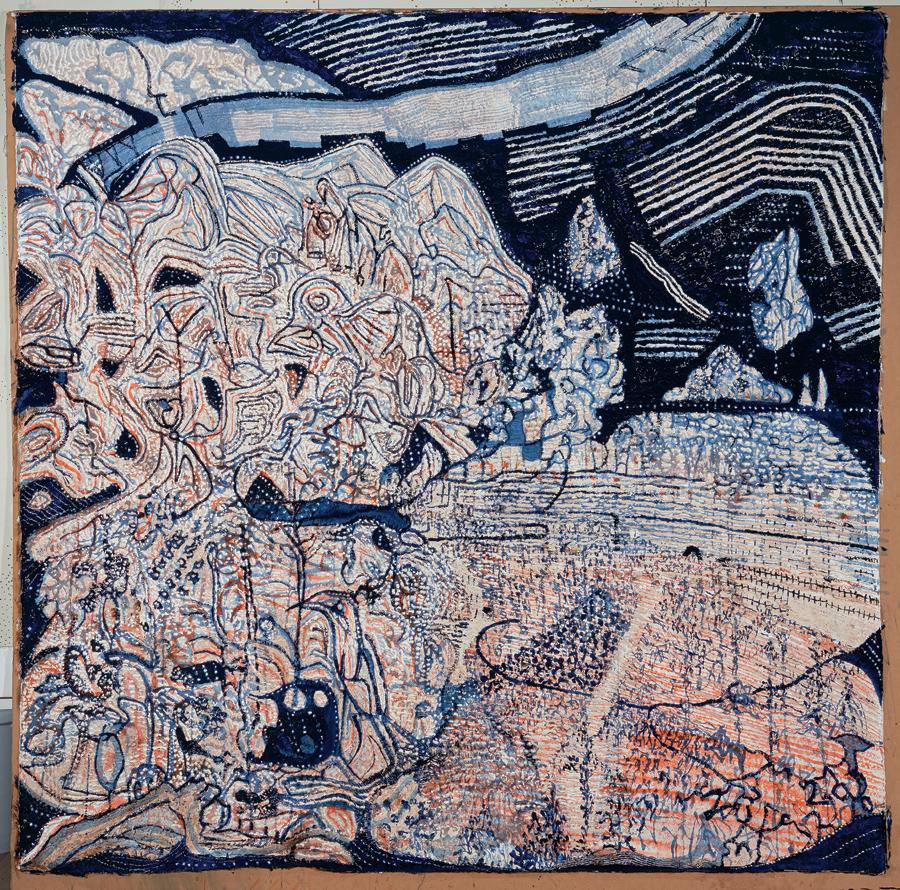

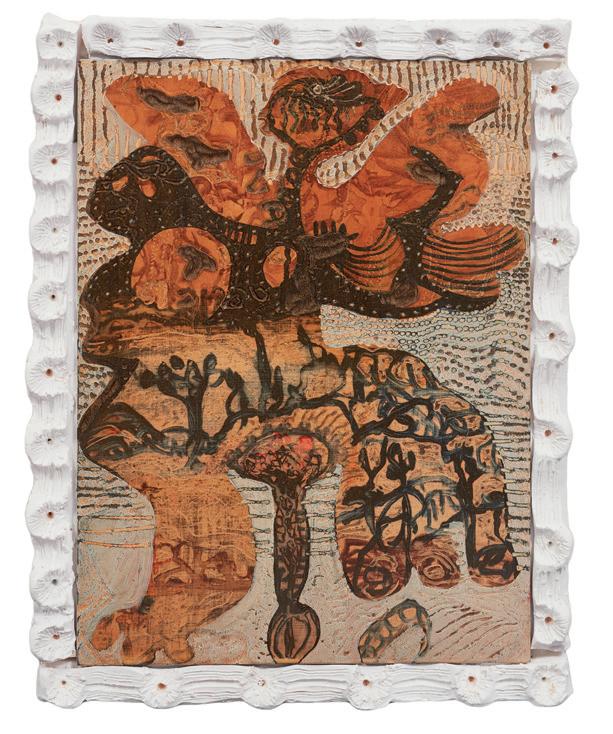

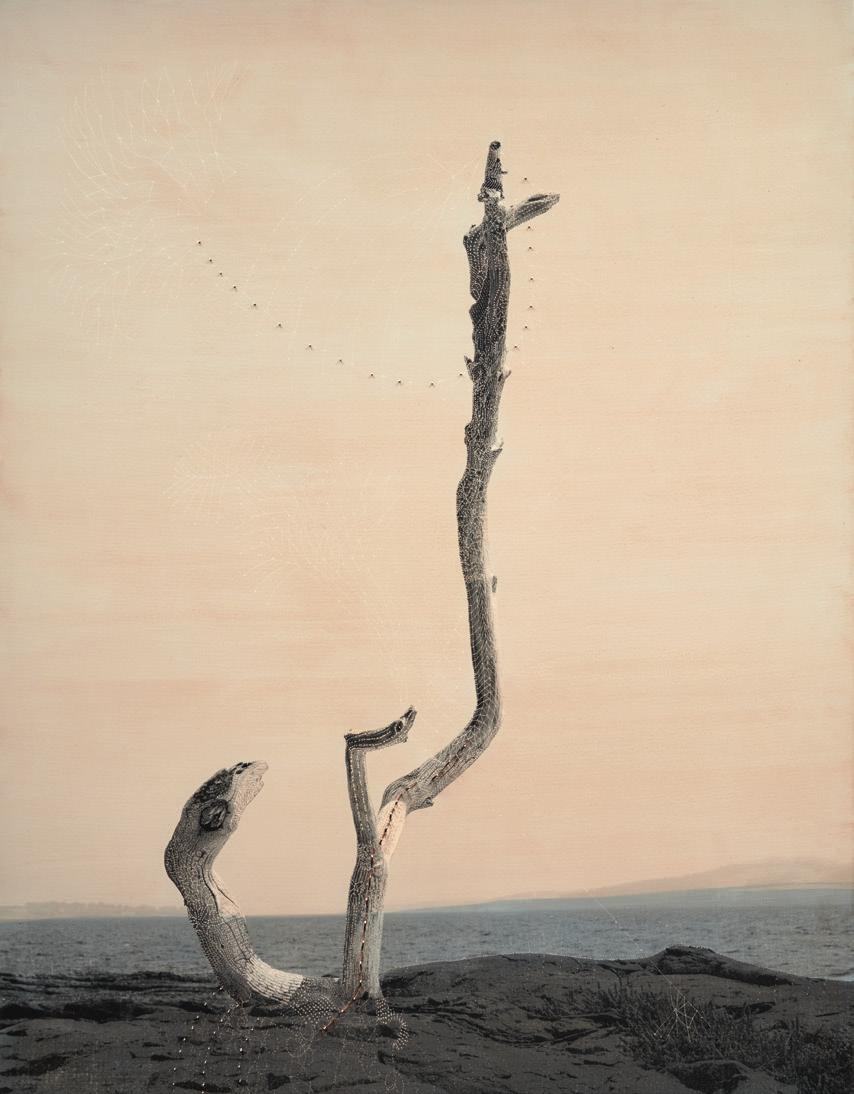

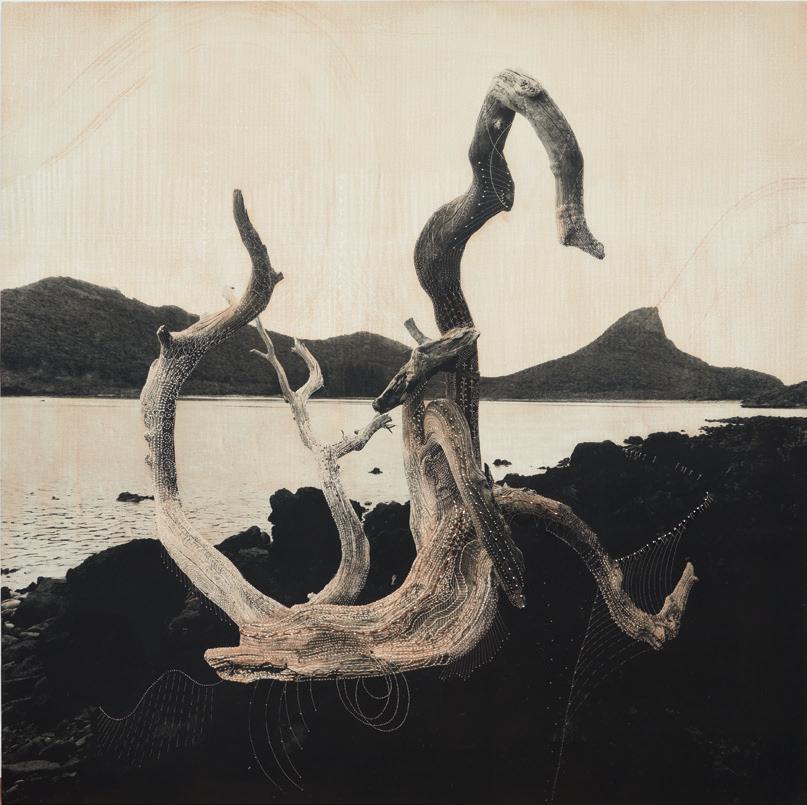

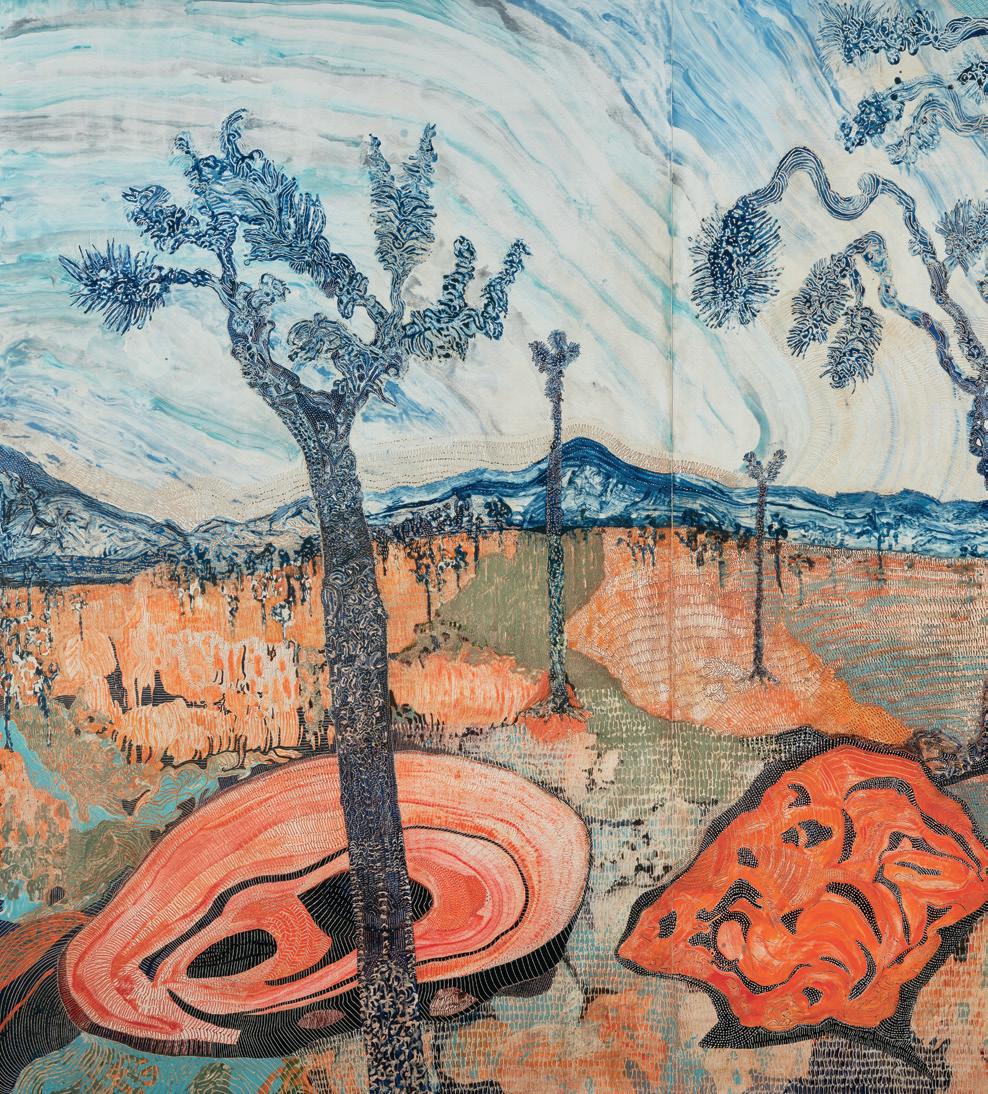

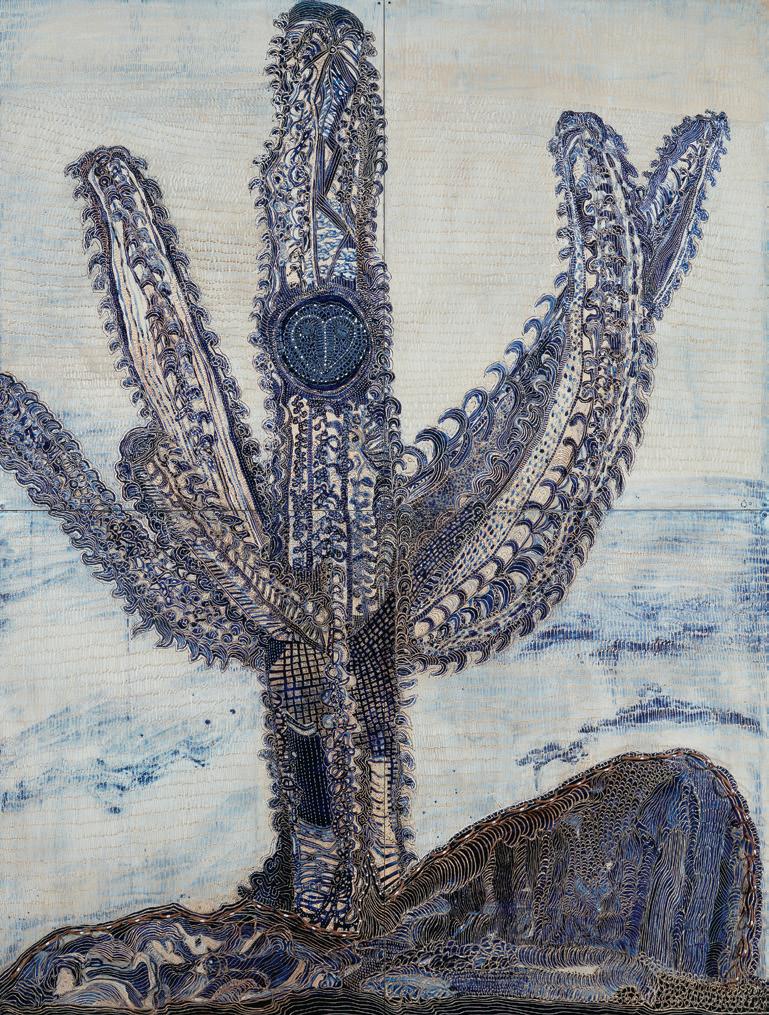

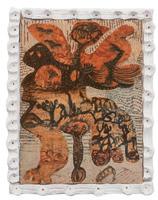

Each major work grows over months. Some take years. In some ways this very gradual process forms an elaborate cocoon for the subject coiled inside the painting. Carved, glazed and sometimes studded with bamboo or shards of porcelain, Yeldham concedes that the depth of time invested in each work is akin to the pace of plant growth. Time is one of his most precious materials and he stretches it out to contain multitudes. From the seed of an idea sprout the facets of his own cosmology with animal totems, ritual colours, recurring symbols and a deep library of markings. Each work is an undertaking without a deadline, often embellished to the point of visual exhaustion. Like a network of nerves or thread roots, his tiny griffes form the invisible web that link impossible structures; The cobweb that holds up the mountain.

For Yeldham the variety of nature is his constant and his wellspring:

“If you take one window of nature and you look at the patterning from the veins in the leaf to the bark, to the fungus, the detail is boundless. When I paint, many of my works are highly intricate but they are just the truth of what is in a leaf or what is on a rock, there are so many striations in a single stone.”

Hive-like, the carved surfaces and pulsing texture in many of his best-known landscapes share a convex quality. Many of his pictures appear to breach their perimeter, pressing on to grow beyond the frame. This burgeoning microdetail can beckon scrutiny or forge a barrier. Like Klimt’s forests, their dense skin can form a seal where the eye can go no further. The mutability of his materials form a critical aspect, because it’s hard to know what is wood, paper, canvas or bead when the force of line leads the eye. The image succeeds through convergence.

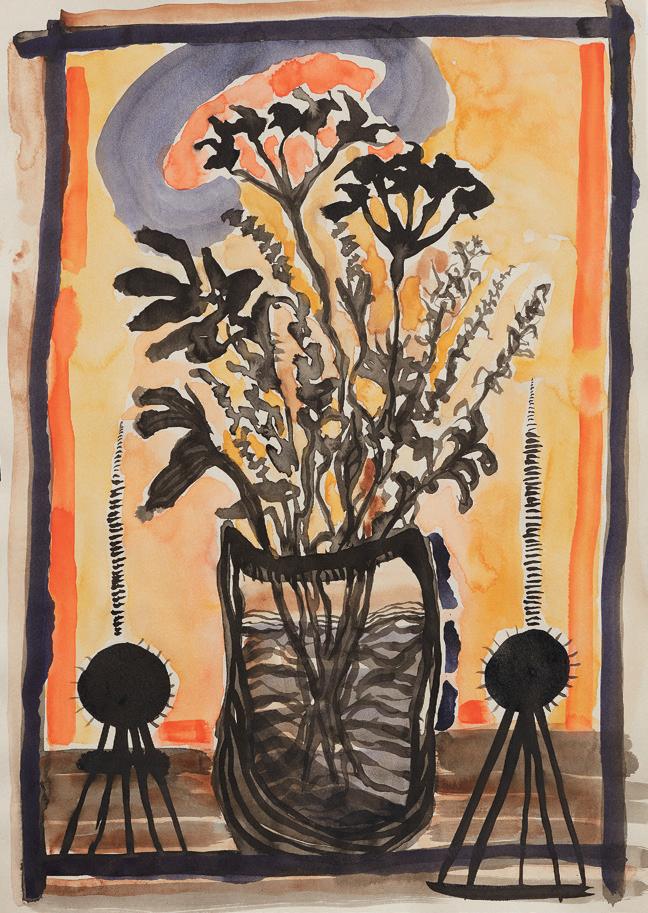

The desire to replicate the intense simultaneity of nature is a rare one. But the bounty of skill can also confine. The large paintings created during lockdown with his family swerve between the lyrical and the melancholy.

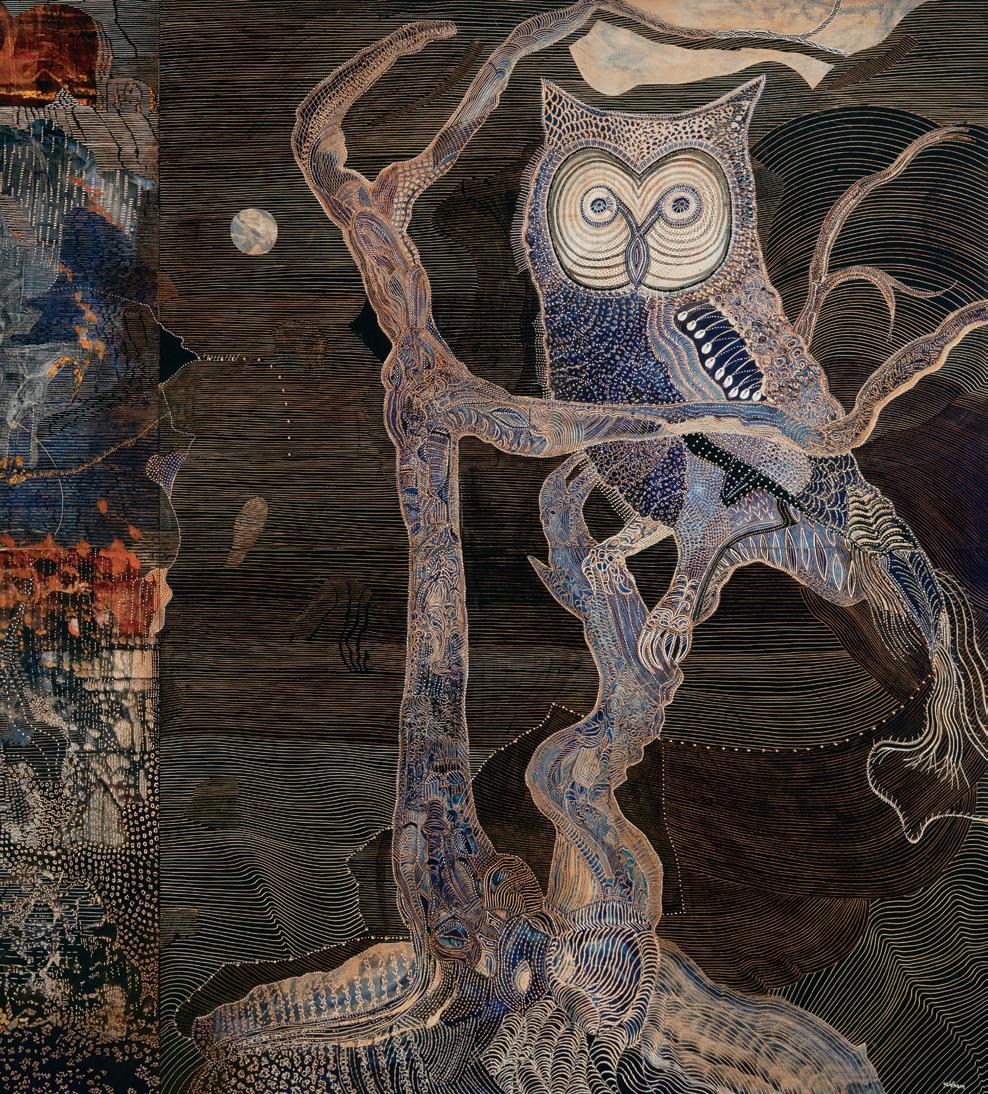

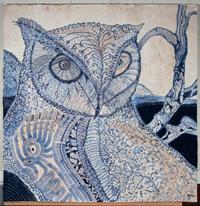

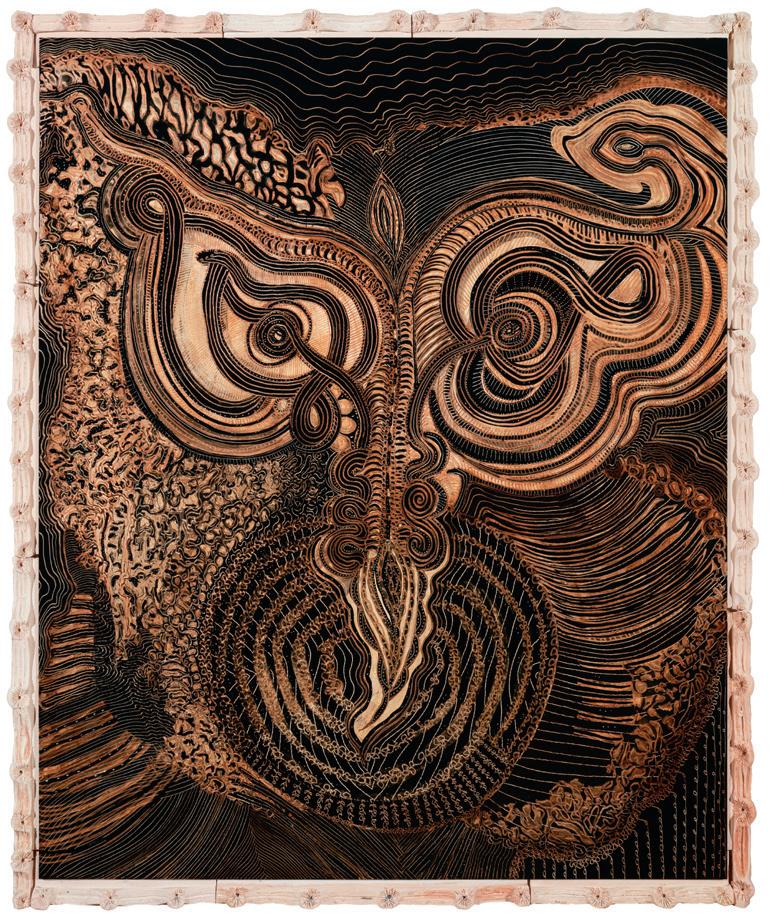

Morning Bay-Night Wave presents a mythical vegetable anatomy: part vine, part artery. The landscape that flanks The Great Burn Owl expresses its opulence and depth through rich colour. The rust of flames, the soot of ash, the quenching haze of indigo. Verging on the psychedelic, the painter admits that this concentrated time in his studio generated “epics”. Some were classical: the elegant balcony in View from the veranda - rain evokes Matisse in Cimiez. The core of its composition is an ethereal void. Was this a response to enclosure? Perhaps it is a natural evolution of his use of space. The compulsion to ‘complete’ an image by covering the entirety is receding.

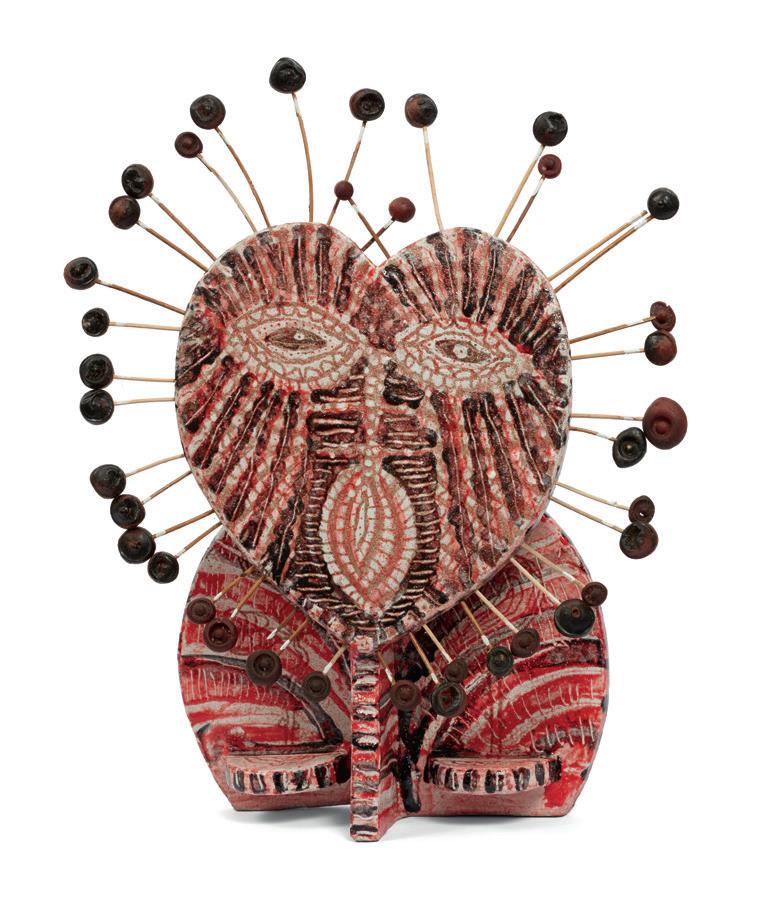

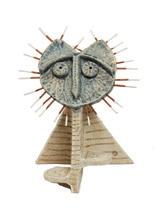

Yeldham’s pace is ceaseless as the tide. Into the mix of a large collection are also ceramics, a new branch to his metier. To the heuristic mind there is no hierarchy of materials. The challenge and temptation to converge two and three dimensional objects into the same picture plane is an ongoing quest. The pottery studio beneath his house is now a fully-ledged atelier stacked with hybrid creatures. Nothing goes to waste; on some of the paintings ruined pots served as fresh grist, jutting from the canvas like fish scales.

Moving from paintings that evoke ancient Muromachi screens to gutsy three dimensional montages is a sweep. This wide collection of pieces, like all of Yeldham’s prolific output is not easily corralled. Yet something does thread the new work together: a shared sense of yearning. Many of his lock-down compositions depict views from windows, balconies and coastlines. Constructing sculpted paintings clad in panels of antique Japanese wood, wallpaper and ceramic frames, the artist took the idea of the interior further. Literally building the rooms he imagined beyond his own. The impact is one of ultimate enclosure.

“I built a world that I craved. Like a tendril I was seeking light. The strangler fig , the monsteria, both have the capability to adapt to any experience, and it is this innate intelligence that inspires me, their projection forward.”

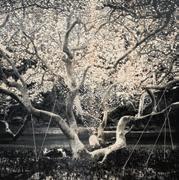

In Yeldhams’ creative space there is a floor above the main studio he calls the “breathing room”. It is here that he takes works to rest in case they over-cook and it is here that he left many of his most existential paintings when he took his family to Europe. The release of the work he made there is stark and it formed the conceptual foundation of Garden of Ruins.

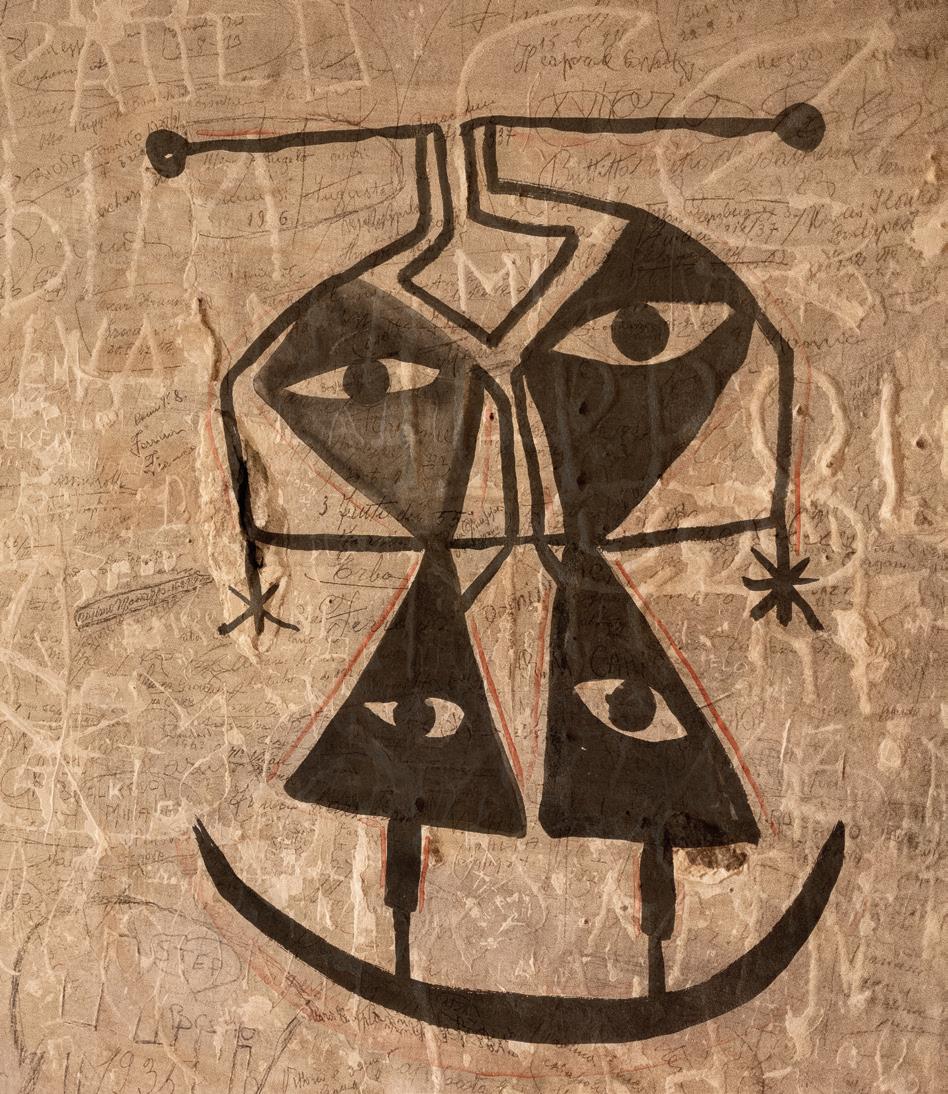

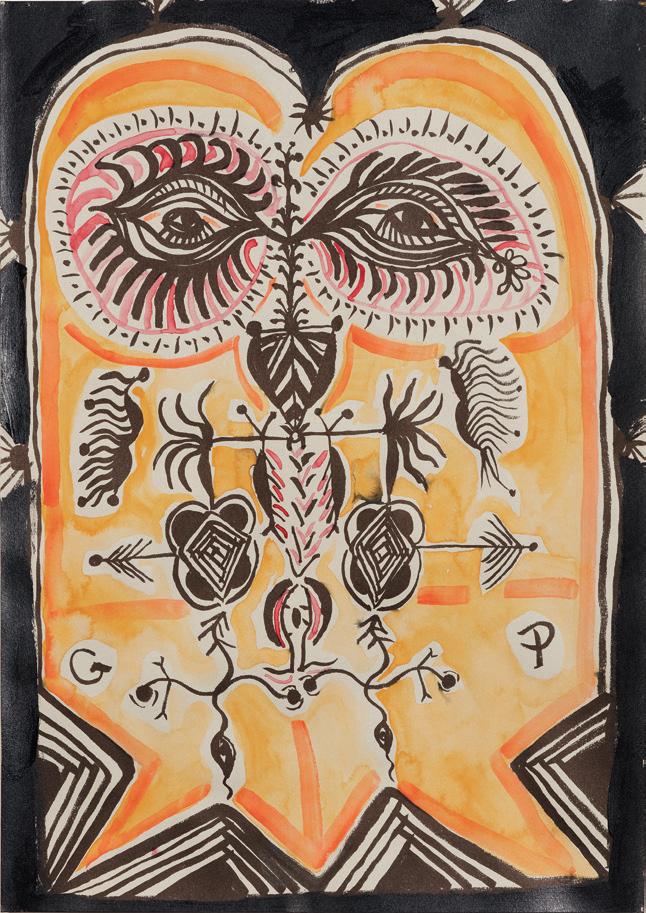

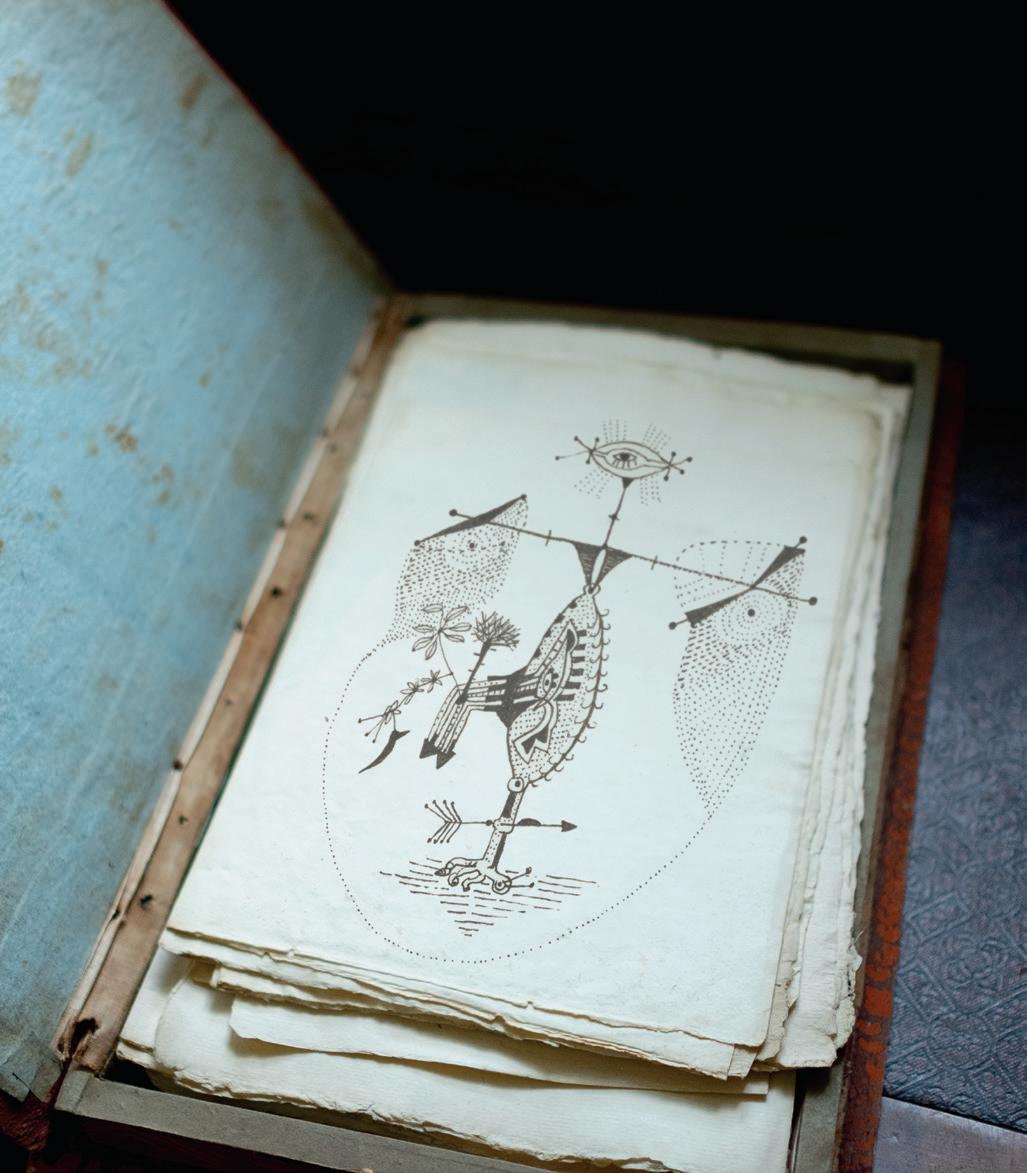

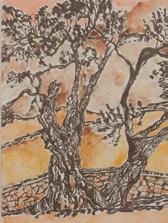

The journey began in Kythira in a house abandoned. Amongst the broken plaster and empty rooms where birds roosted, works on paper were made at speed. The ‘siesta studies’ as he calls them were his direct response to solitude. Yeldham was influenced by the rugged beauty of a patina centuries deep.

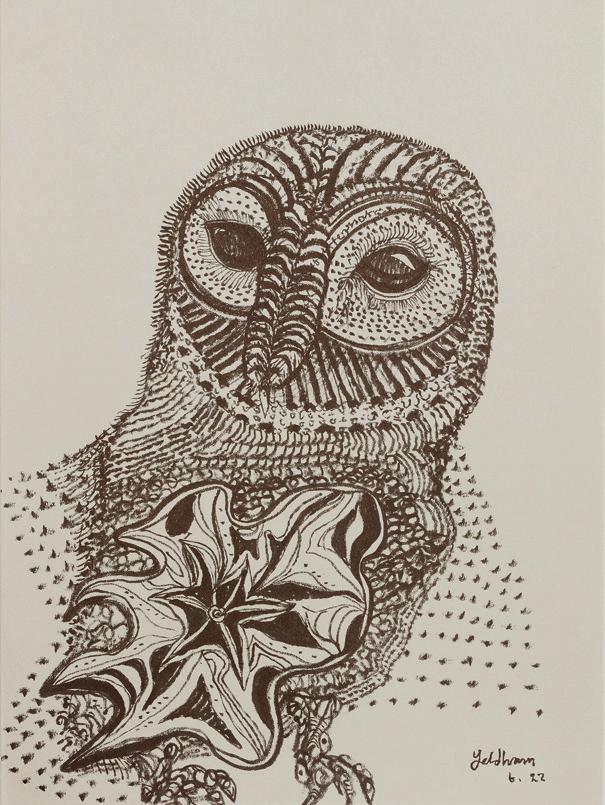

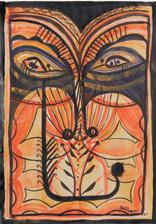

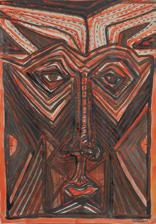

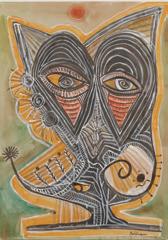

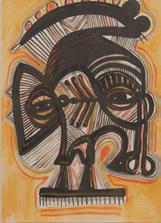

"I thought my creativity could make up for absence of humans in the ruins. To bring the human love back into the space. The forms I used came from a life of exploring polarities and all the symbolism that connects back into the natural and mythological world: the claw, the eye of the owl, sacred symmetry and recurring patterning. I drew on where I was and the reserves of my own imagery. My pictures are like ruins, they have their own codes and archaeology.”

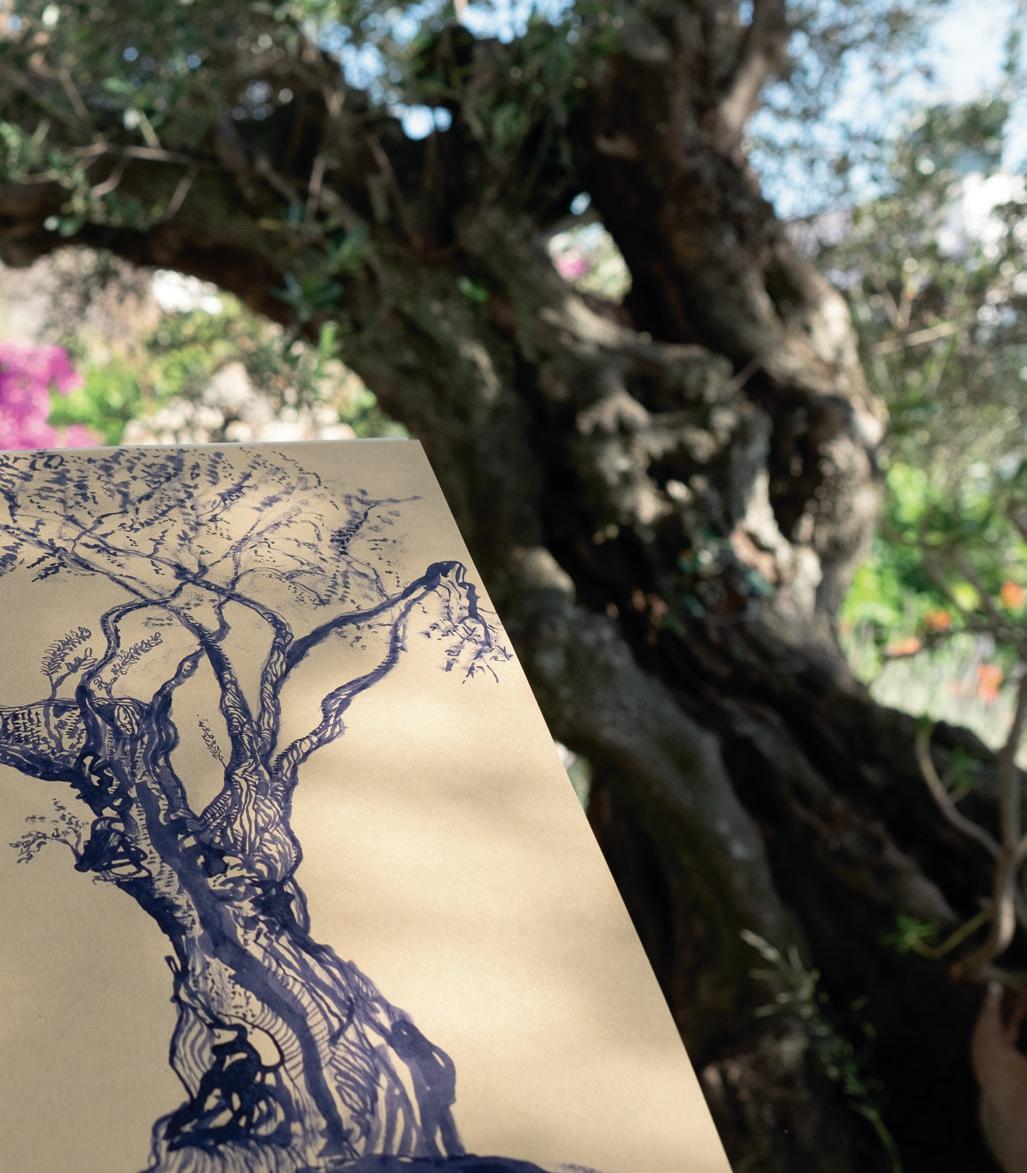

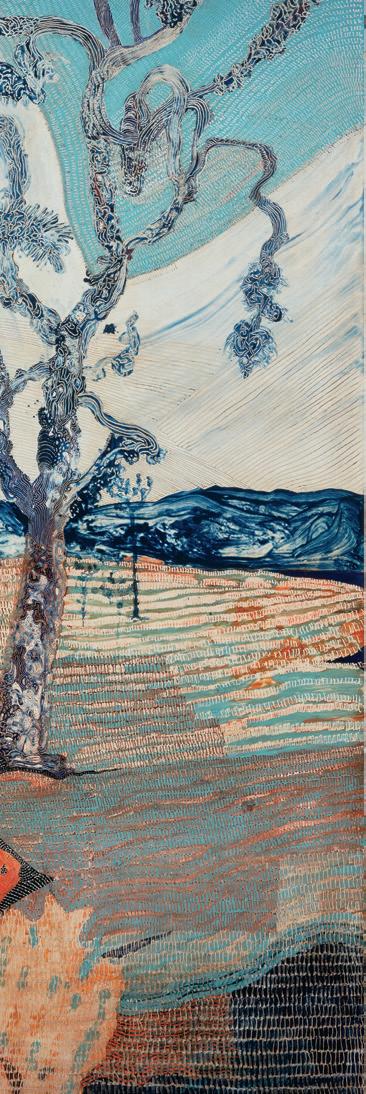

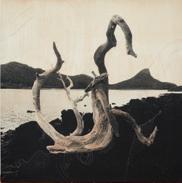

The Mediterranean landscape, marked by thousands of years of invasion, drought and contagion served as an elliptical echo. Yeldham was influenced by the tenacity of nature in the face of destruction . A gnarled tree in the stone garden of the Greek house bore a kindred lineage to the massive Monsteria that anchors the core of his own home. It was connections such as this that propelled a strong sense of both union and release:

“Art can rebuild your sense of place when there has been isolation. A lot of this show is about reaching out. It’s like a message in a bottle. Sending a signal out that we exist. Each place we stayed became a studio and it was perpetual. The art leaves a pulse, an imprint, a thread.”

The desire to join with ancient spaces and new terrains built a bridge out of watercolour paper. The drawings are raw, abandoning his signature finesse for something wilder and more immediate. The ritual of painting protective symbols upon dwellings is something he explored; Pinning his private talismans to bare walls, ravaged stone and trees and ‘tattoing’ public spaces with digital projections, the idea of marking the space was a core ritual. Brought home after time in Italy, Southern Spain and France, these studies inspired a fresh collection of carved clay sculptures designed to hold candles like a votive altar. Gathered together on sunlit tables they share a collective solidity. Replete. Carved like his photographs and paintings, the platters and bowls balance utility with ornament. Yet for this particular artist there is no such thing as ornament, as each marking is so critical to the whole.

In constant motion, it’s tempting to see the accomplishment of a mature artist as a reflex. But instead of leaning into his deepest grooves, Joshua Yeldham plunges into new mediums and finds relevant ways for them to cross-pollinate. Garden of Ruins is not a retrospective but a survey. For although chronology is not that useful in understanding such a diverse trajectory, a timeline from 2020 to the present is meaningful to everyone. Life hung suspended and not everything generated within that time could compensate for the loss. These years form an arc that remains vulnerable and raw because it is unfinished.

In that closed window of time one studio was singing a redemption song. But even the most exquisite works in this exhibition share a subtle undertow of shadow and collective doubt. The agency of creating was one artist’s survival tool, a force of budding against decay.

ANNA JOHNSON

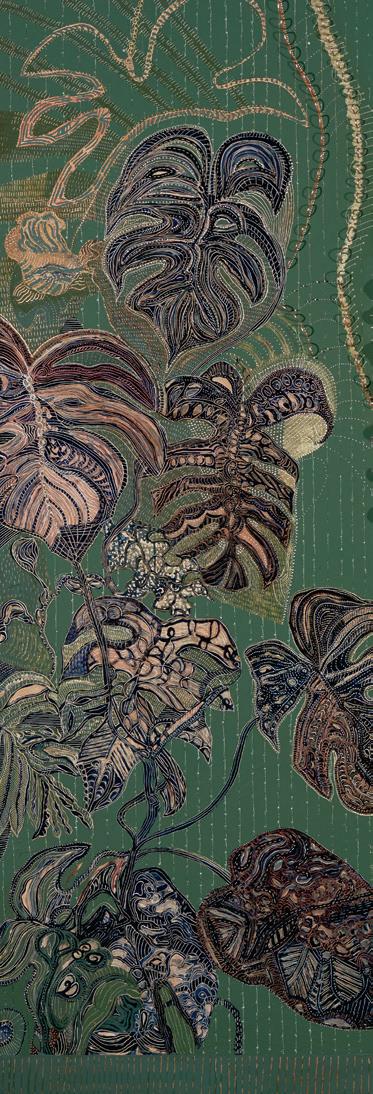

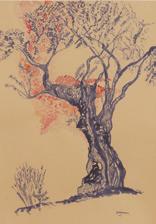

3. Olive Tree - Kythira

3. Olive Tree - Kythira

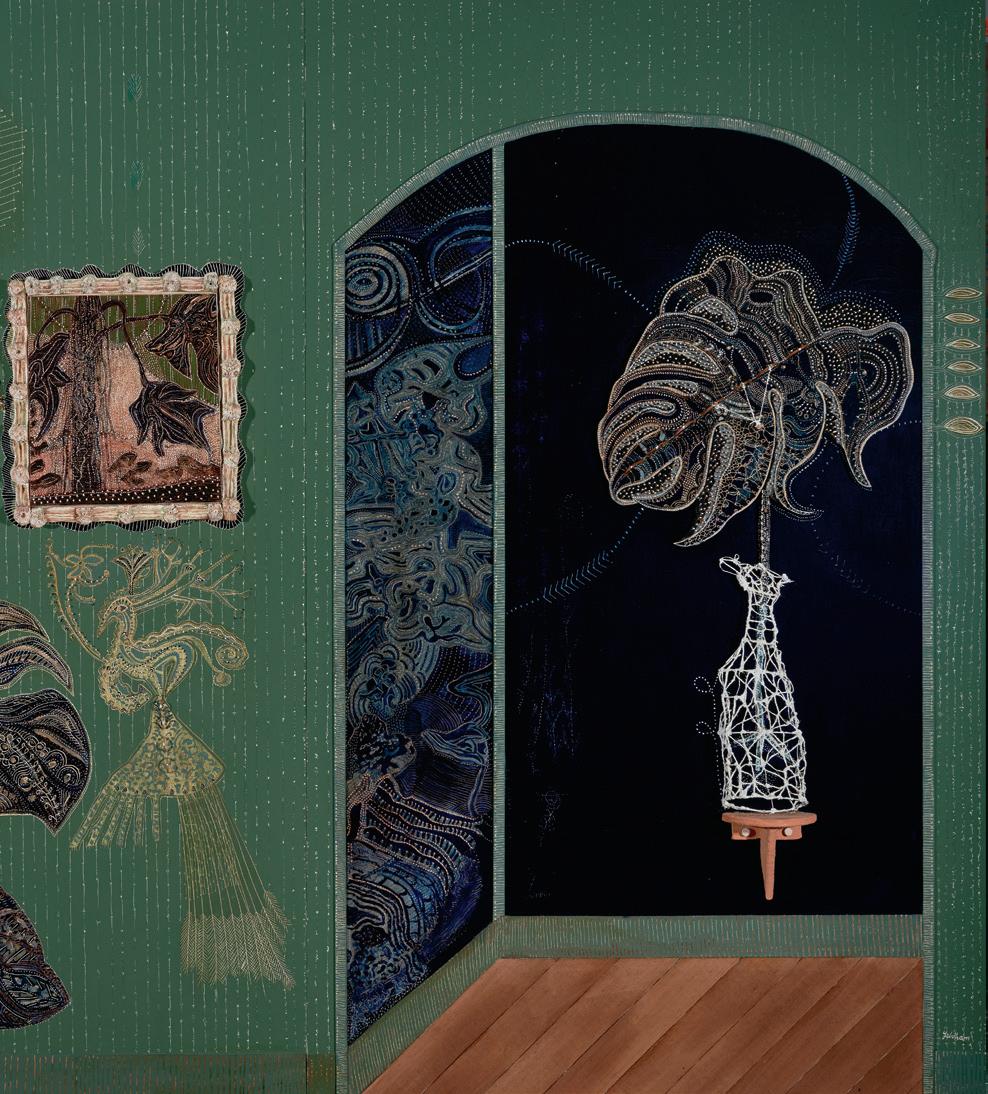

5. Interior with Monstera

5. Interior with Monstera

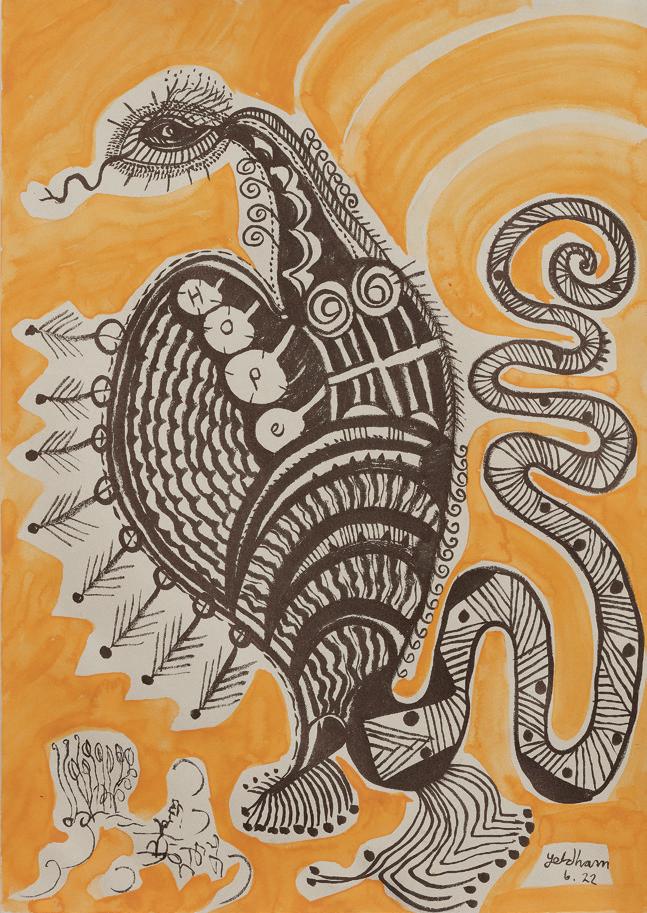

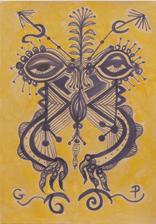

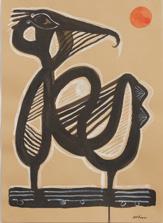

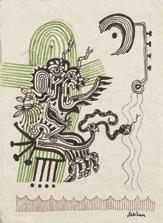

6. Dragon of Hope

6. Dragon of Hope

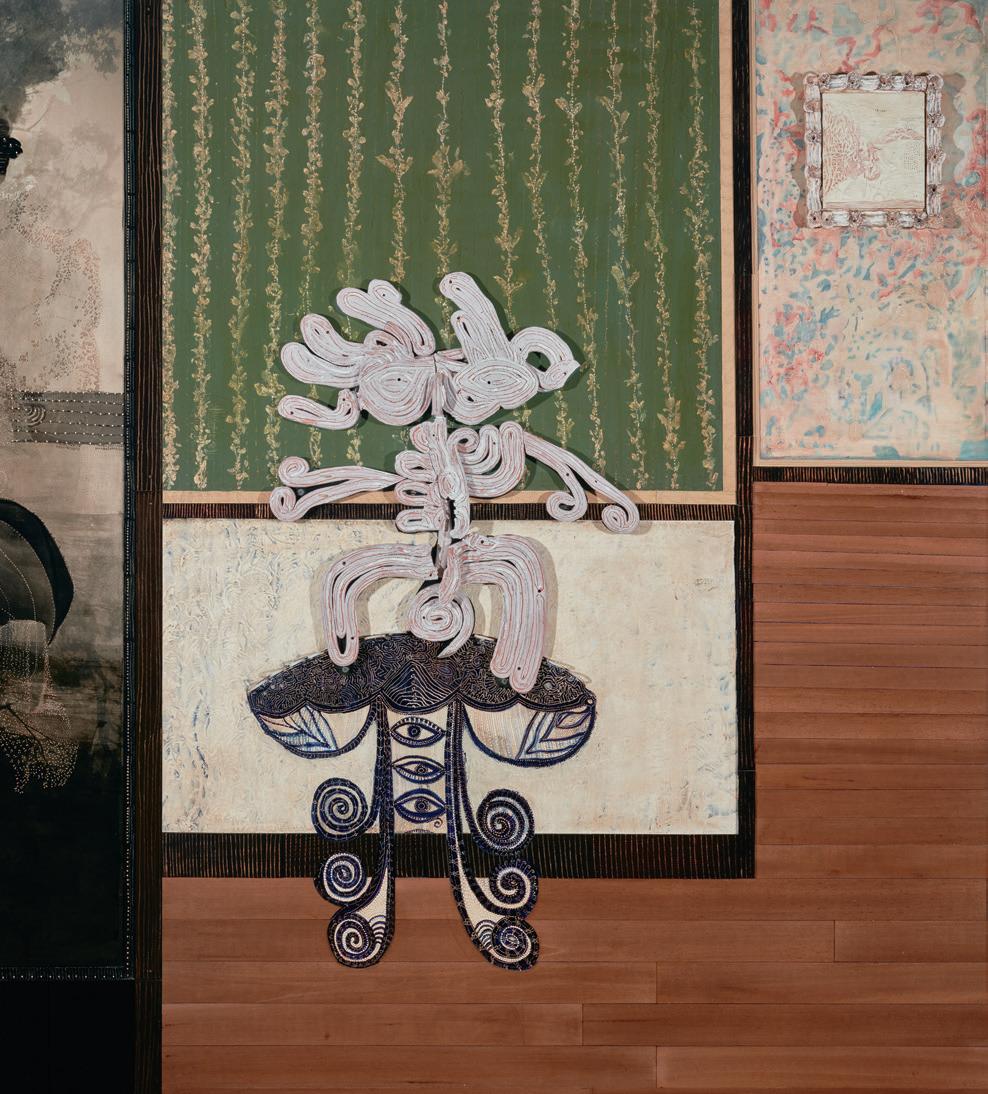

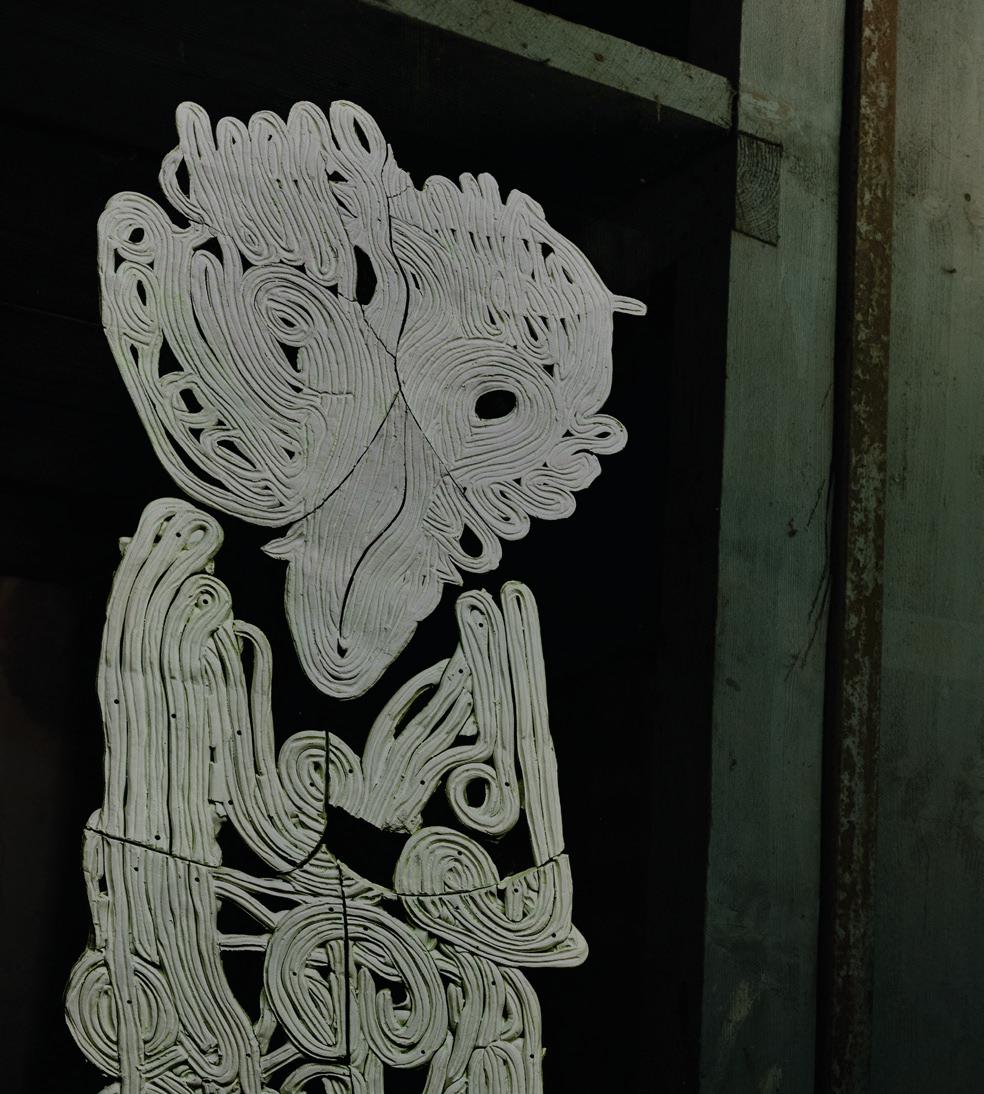

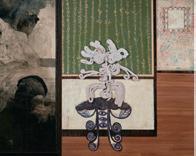

7. Three Walls with Ceramic Figure

7. Three Walls with Ceramic Figure

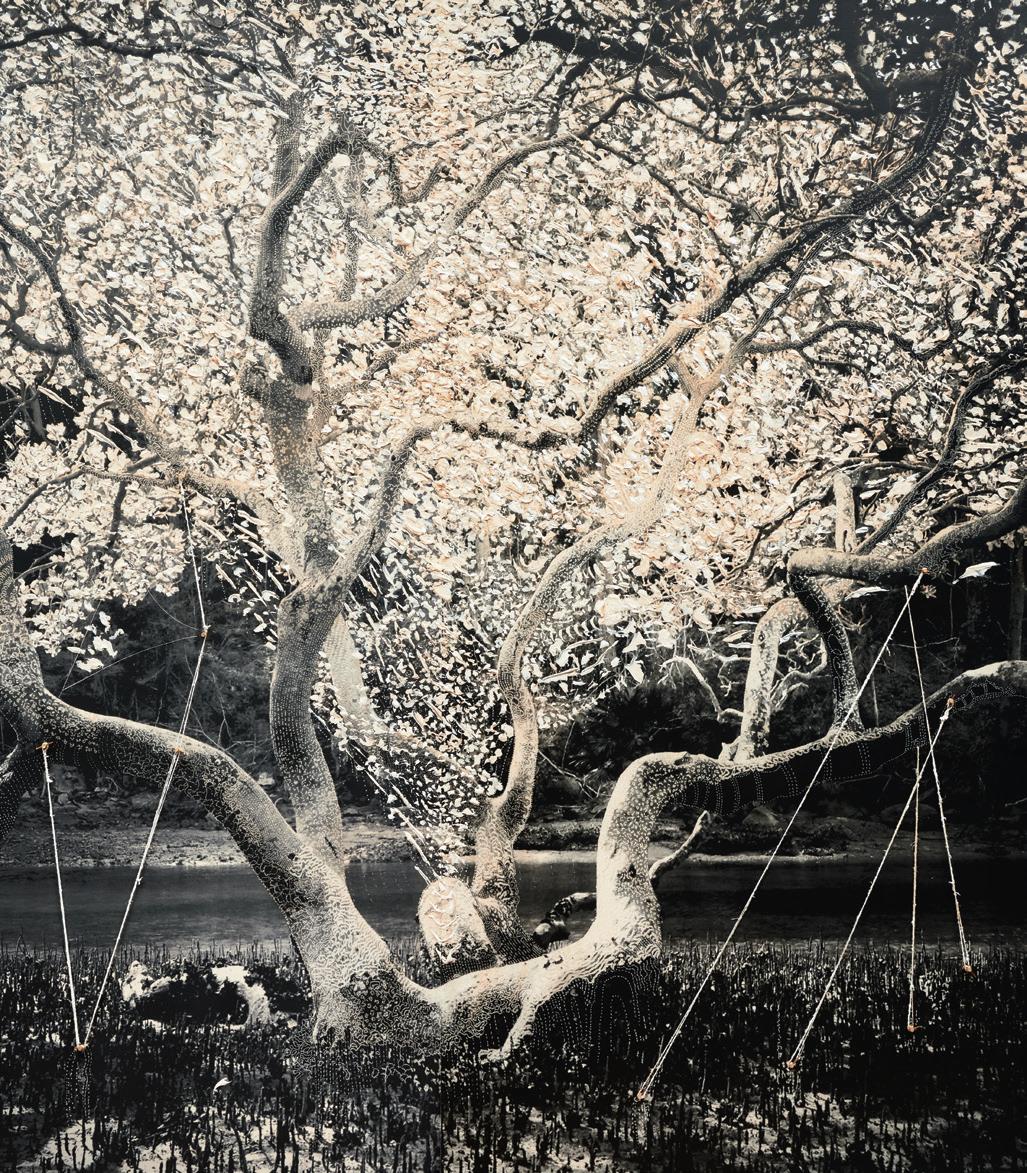

10. Studio with a View of Strangler Fig

10. Studio with a View of Strangler Fig

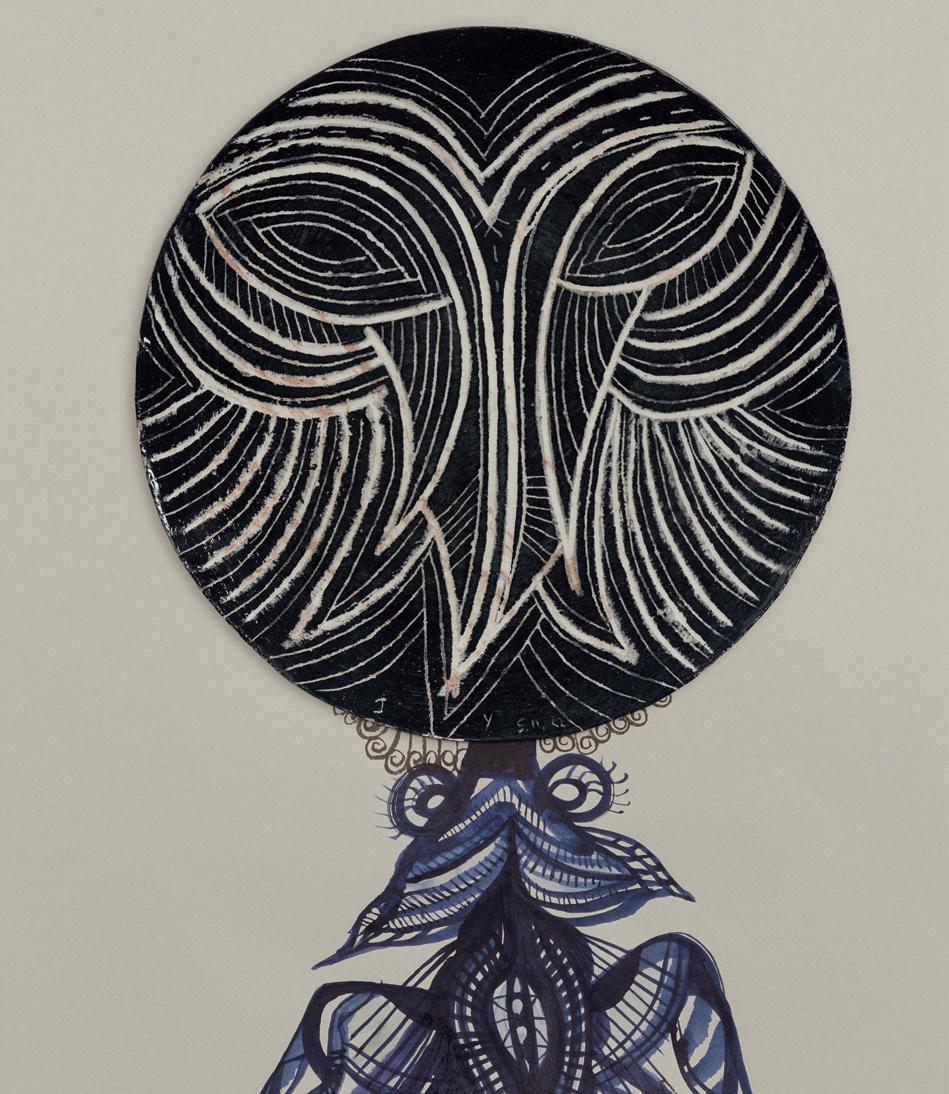

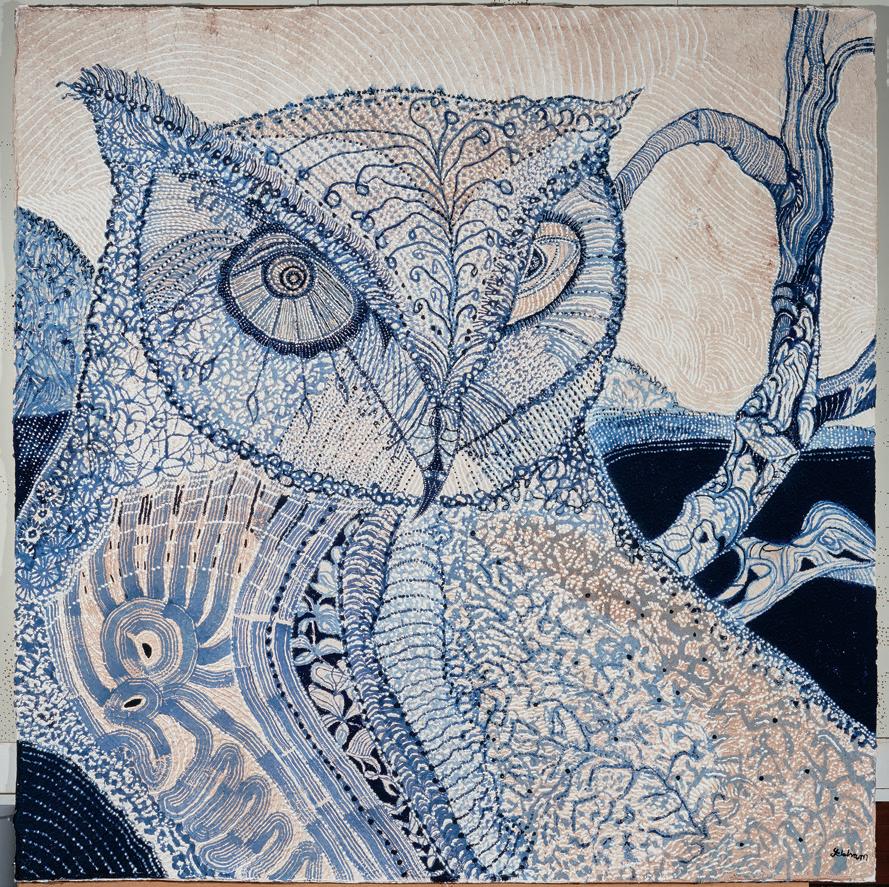

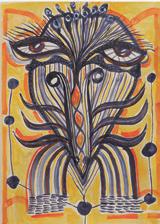

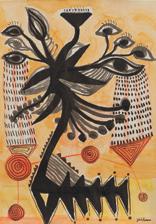

11. Owl of the Cosmic Field

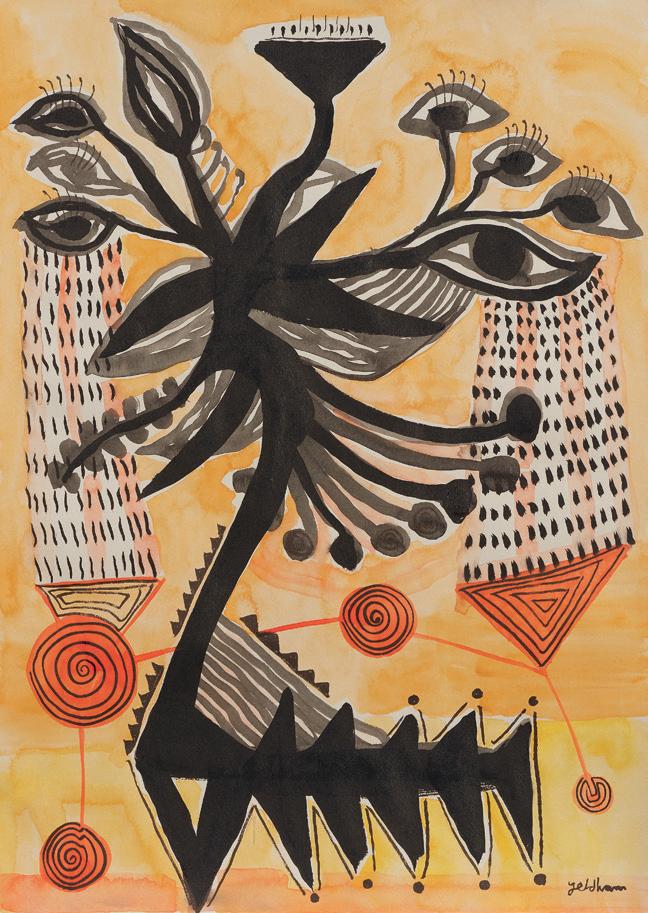

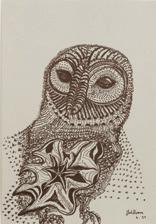

12. Study for Lantern with Many Eyes (opposite)

13. Owl of the Morning Sun

14. Study for Fertility Sculpture (opposite)

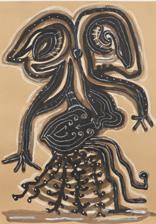

Owl of Turin

Two Sisters (opposite)

23. The Stone Gatherer

23. The Stone Gatherer

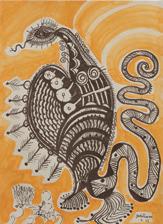

Taro Figure of Hope (above left)

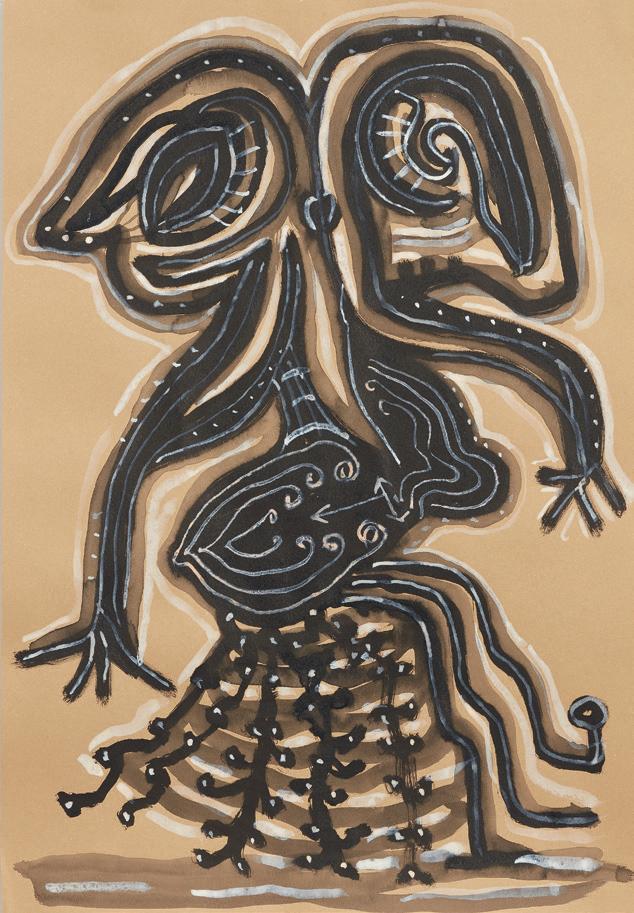

River Creature - Black Moon (above right)

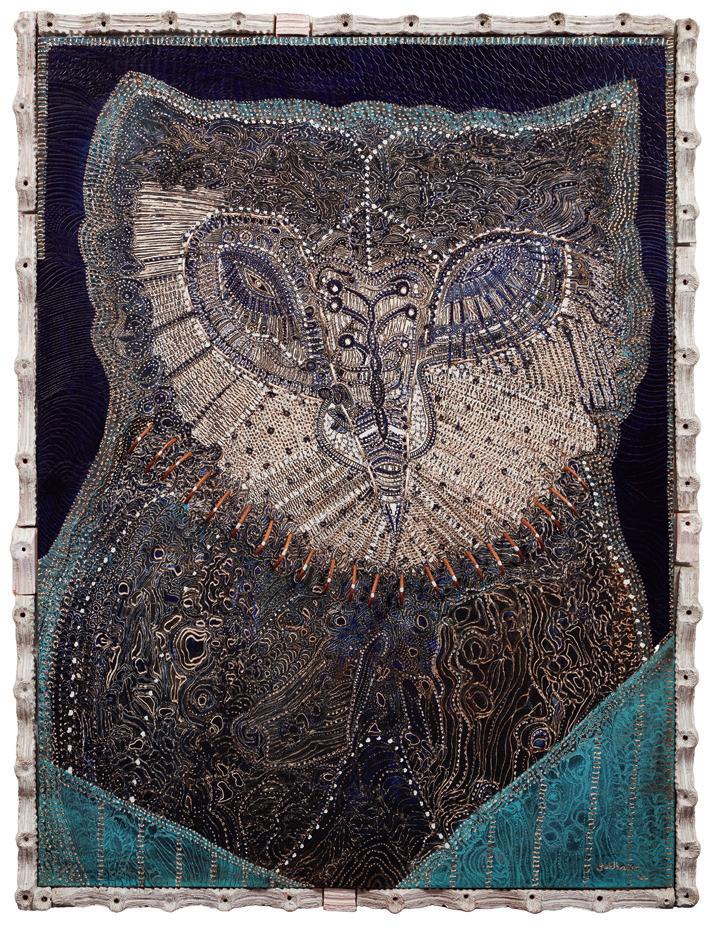

31. Owl of the Energetic Field (above) 32. Owl of Black Fertility (opposite)

31. Owl of the Energetic Field (above) 32. Owl of Black Fertility (opposite)

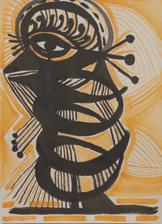

Owl Mask - Plum Tree (above)

Owl of the Orchard (opposite)

42. View from the Tinny - Cottage Point

42. View from the Tinny - Cottage Point

from the Studio - Pittwater

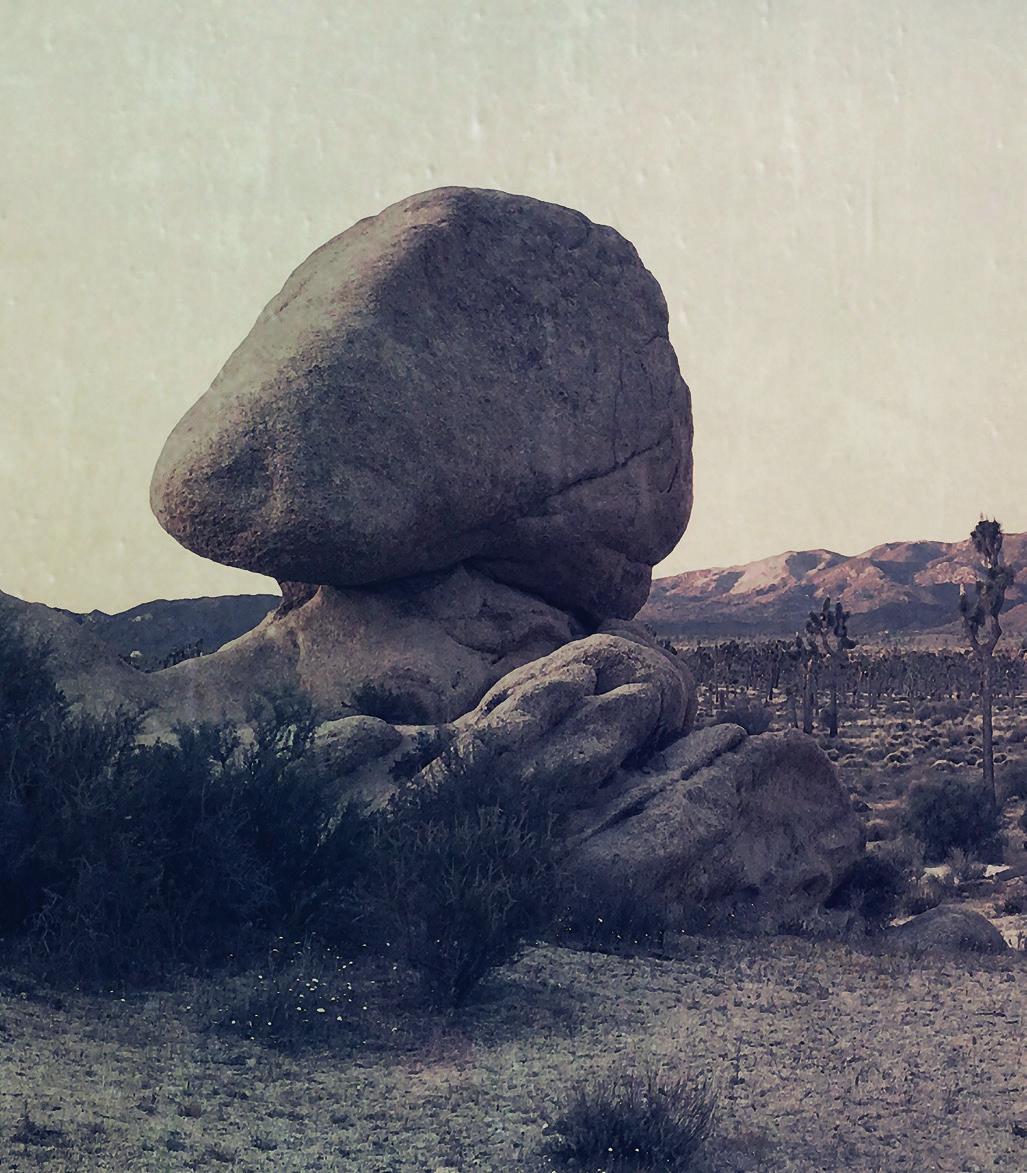

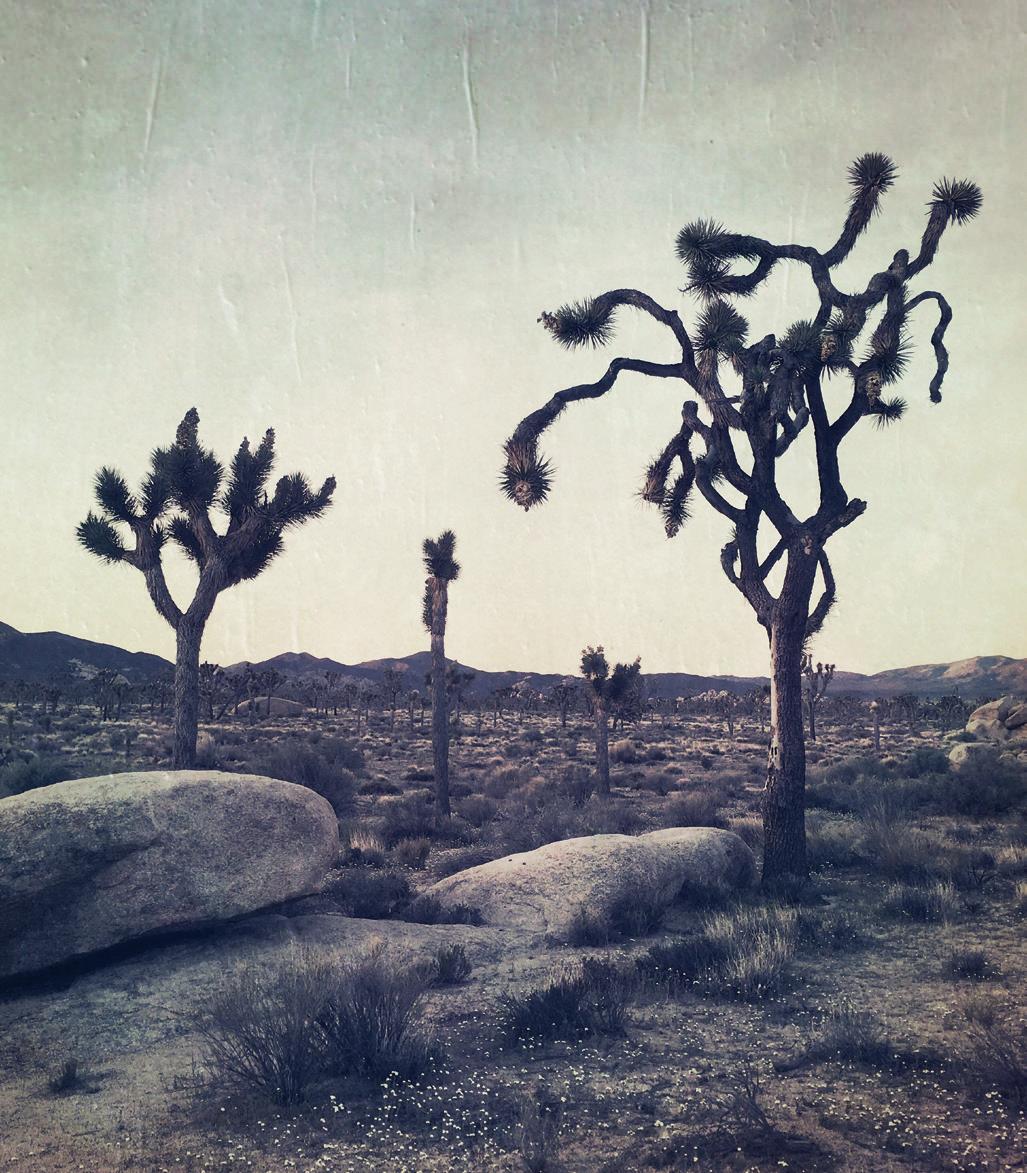

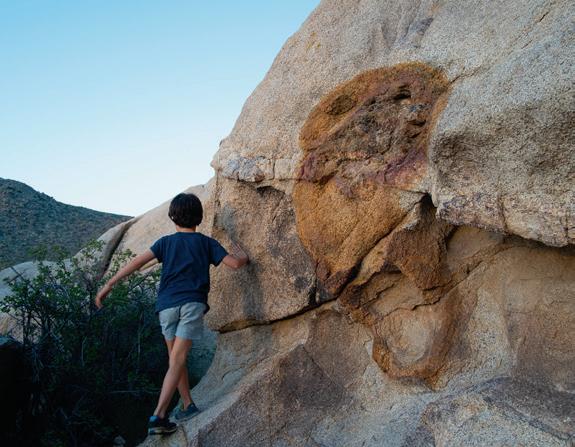

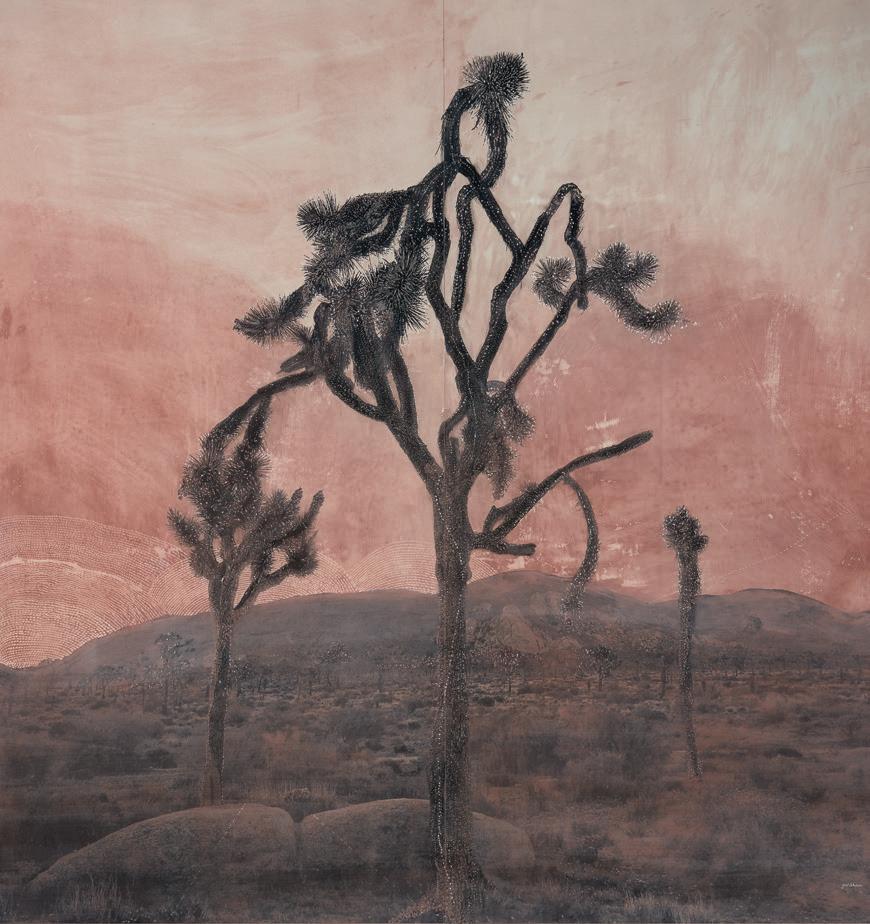

57. Joshua Tree - Snake Rock

57. Joshua Tree - Snake Rock

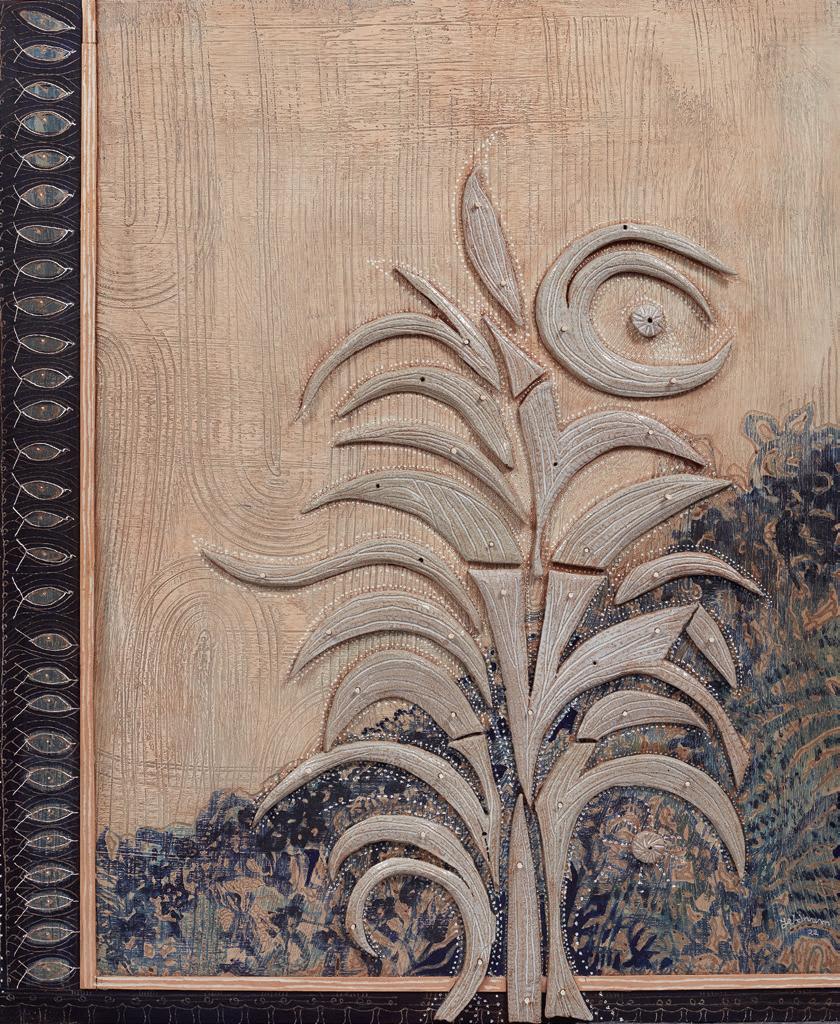

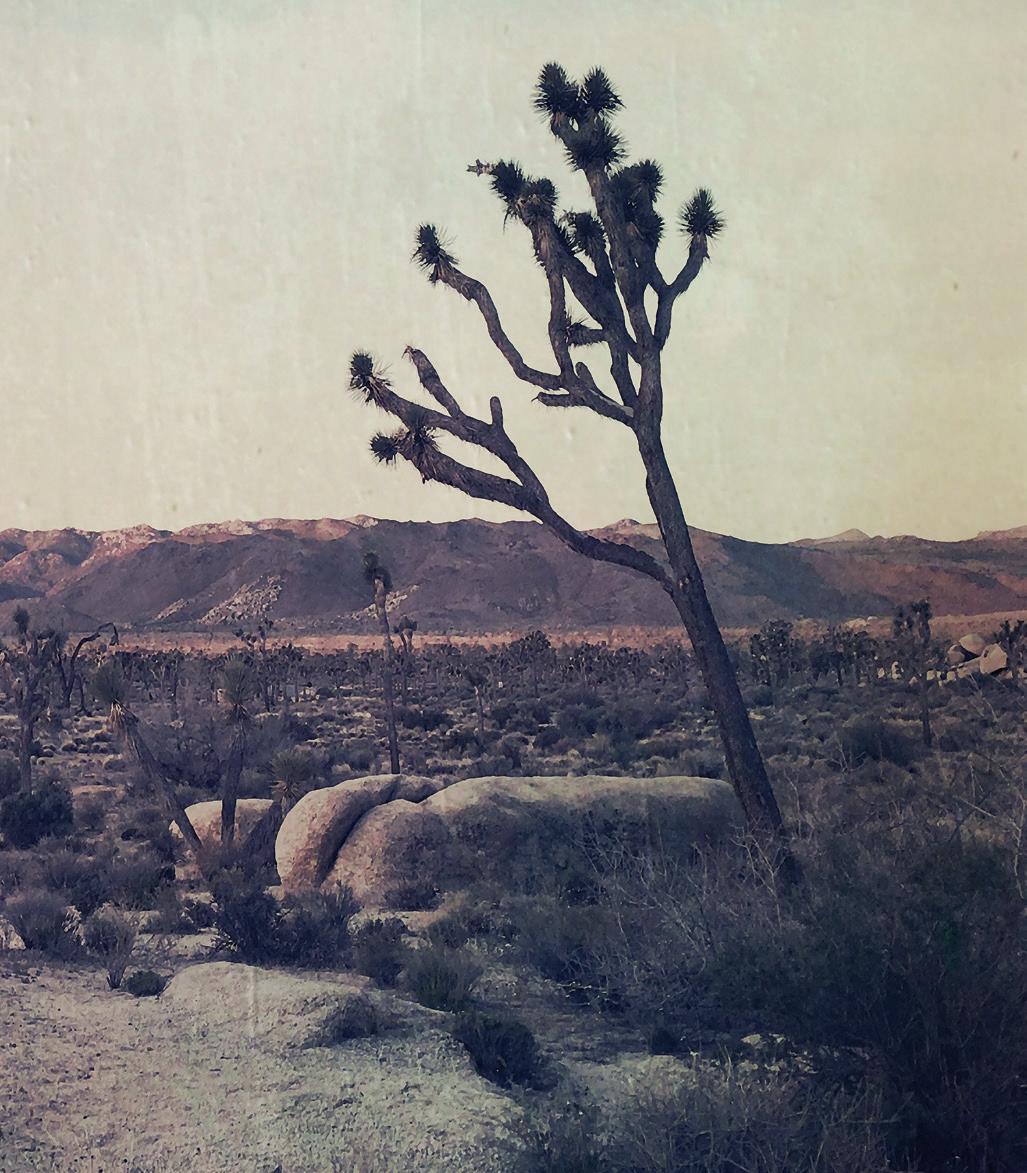

58. Growing to the Stars (above)

58. Growing to the Stars (above)

59. Owl of Blue Bells (opposite)

59. Owl of Blue Bells (opposite)

Sometimes you just want to hold something made architecture of our time here a ruin for plants to grasp refuge from those bright and perishable digits the two things rearranged 0’s & 1’s Light can embed it and emanate through its broken parts But it doesn’t make us question ourselves it reminds us who we are because we found it given attention or none

Still &

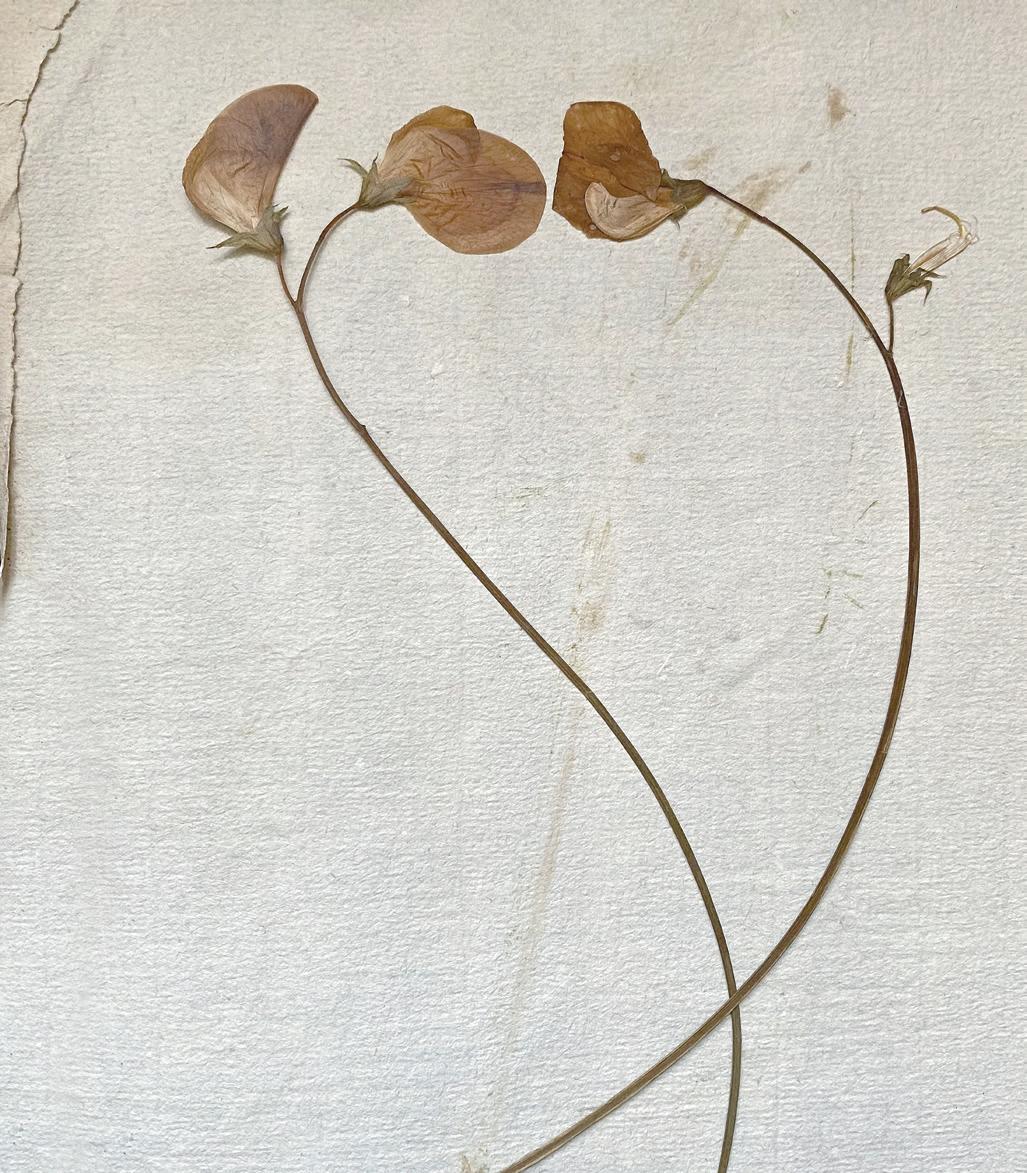

A flower pressed onto a page earth reshaped a note in a bottle pitched out to a stranger at sea time & weather and another’s hands only, influencing its course.

Jo Yeldham

105. Kythira - Acrylic on hand carved clay board with ceramic frame - 131 x 108 cm

105. Kythira - Acrylic on hand carved clay board with ceramic frame - 131 x 108 cm

The Gadigal people of the Eora Nation

The Dharug People and Darkinjung People of the Dyarubbin river

The Hopi Nation, Arizona

Scott Livesey

Jo, Indigo & Jude Yeldham

Yeldham family

Herbert family

Sophie Foley

Fidoso Picture Framing

Sam Creecy, Raphael By-The-Sea Manasseh, Ruben Bloom

Alisson Hansen

Nick Laidlaw

John Coleman

Adam Micmacher - Lowensteins

Penny Holmberg

Catalogue Design by Joshua Yeldham

Artwork Photography by Mim Stirling

Photography & Words by Jo Yeldham

Portraits by Cameron Bloom

Text by Anna Johnson

Introduction with pressed flowers by Francesca Galleani D'Agliano Andrea & Chicca Galleani D'Agliano

Colour reproduction by Spitting Image, Sydney

Printed and bound by KHL Printing, Singapore

© Copyright photography and artwork Joshua & Jo Yeldham 2022

www.joshuayeldham.com.au

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permissions in writing from the Artist.

Numerous images in this publication are imaginings by the artist and realised through a digital process. Exhibited at the SCOTT LIVESEY GALLERIES

610 High Street, Prahran Victoria, 3181 & 909A High Street, Armadale Victoria, 3143

T: +61 3 9824 7770

F: +61 3 9824 7771 www.scottliveseygalleries.com info@scottliveseygalleries.com