A man who sold his company to inspire others.

An outsider who put her head down to outwork her competition.

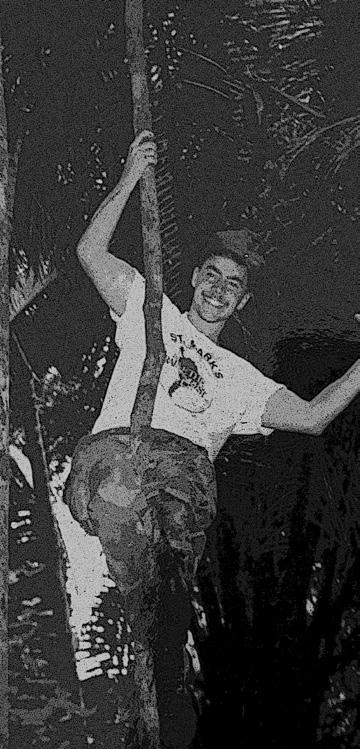

A man shaped by his communities: football, St. Mark’s, and family.

A doctor who found his passion late in life.

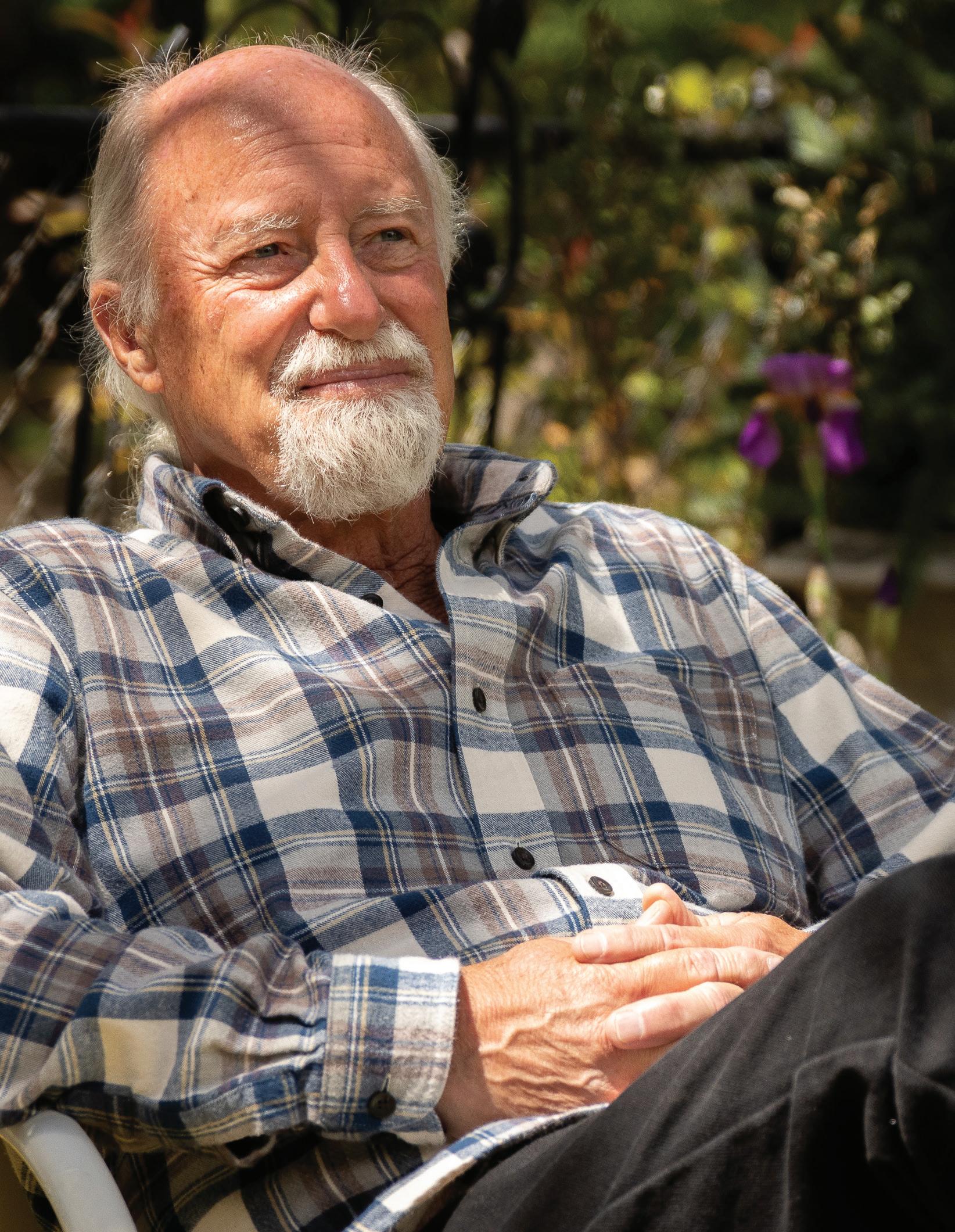

A biologist who vows never to miss another event after missing too many.

A former English teacher tested and trained by his experience teaching in Africa.

KYLE WALDREP

CARLSON ‘05

SARAH CHOI

SCOTT

KOREY MACK ‘00

MARK ADAME

CURTIS SMITH

An adventurer who found his reason to smile and laugh.

A security guard who never lost faith.

Editors-in-Chief

Dawson Yao

Linyang Lee Writers

Noah Cathey

Weston Chance

Matthew Hofmann

Arjun Poi

Hilton Sampson

Joseph Sun

Eric Yi

Josh Goforth

Winston Lin

Doan Nguyen

Kayden Zhong

Adviser

Jenny Dial Creech

The background of the man recording every moment through his lenses.

A woman dedicated to caring for other people to the best of her ability.

Cover Illustration: Josh Goforth

Focus, a magazine supplement to The ReMarker covering a single topic, is a student publication of St. Mark’s School of Texas, 10600 Preston Road, Dallas, Texas, 75230.

staff

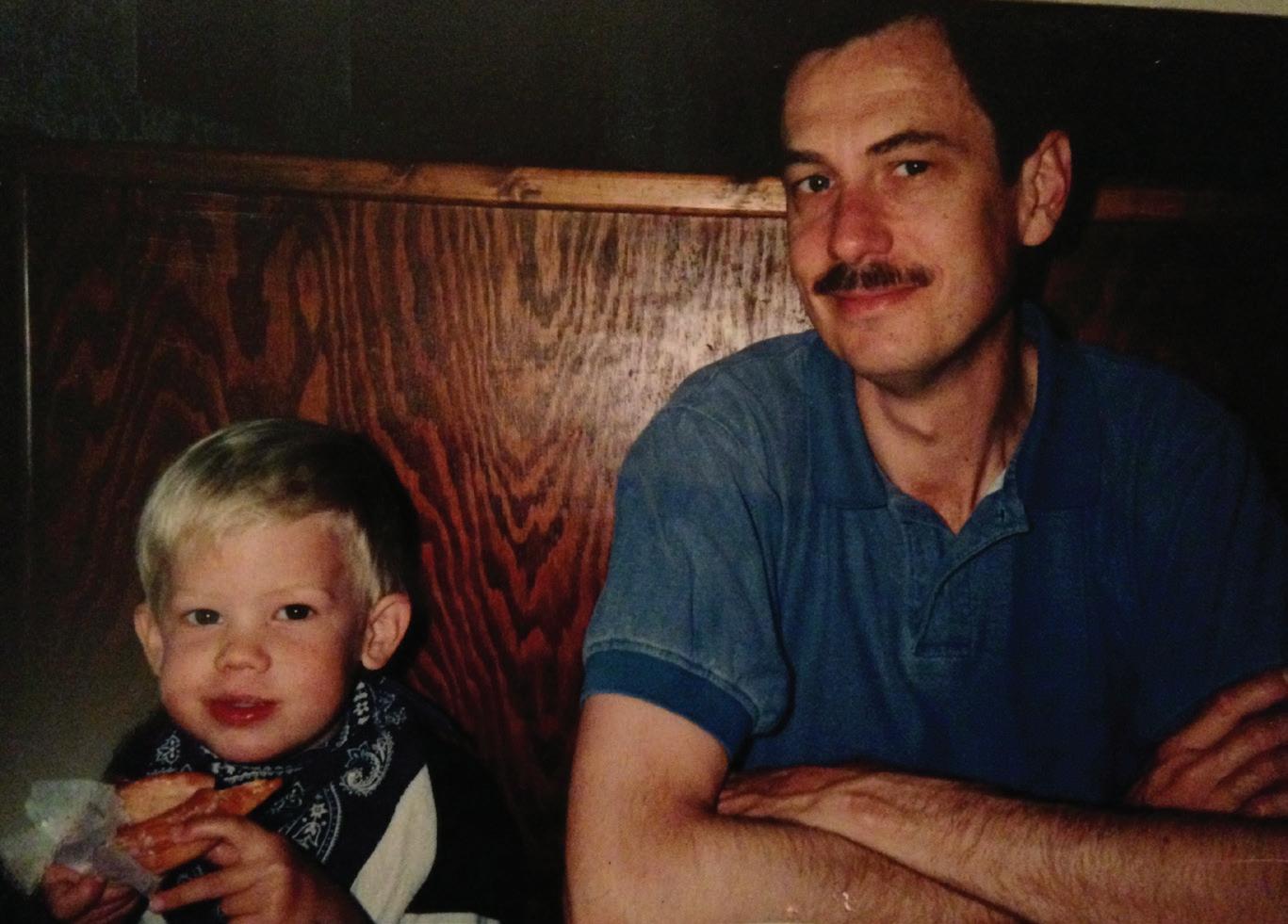

DOUG BRADY DAN NORTHCUT

‘81

DAVE CARDEN

LORRE ALLEN

How do you become somebody?

A lot of people say, “find your passion.” But how exactly do you find your passion? How do you build your character? How do you become fulfilled?

At an age where most of us can’t know exactly who we want to be, it’s hard to know what to pursue next.

We talked with 10 members of our community to find out how they made it happen. How they built the people they are today. We take you through their journeys through life, the victories, the losses and the turning points.

We asked them questions you might find as prompts for college essays. We asked them what they are most proud of. In what way are they least understood. What they would want with one wish.

We asked them to figure out what the “path to manhood” really looks like. Because everyone is on that path.

And everyone can become somebody in this world.

Dawson Yao and Linyang Lee Editors-in-Chief

K K

6

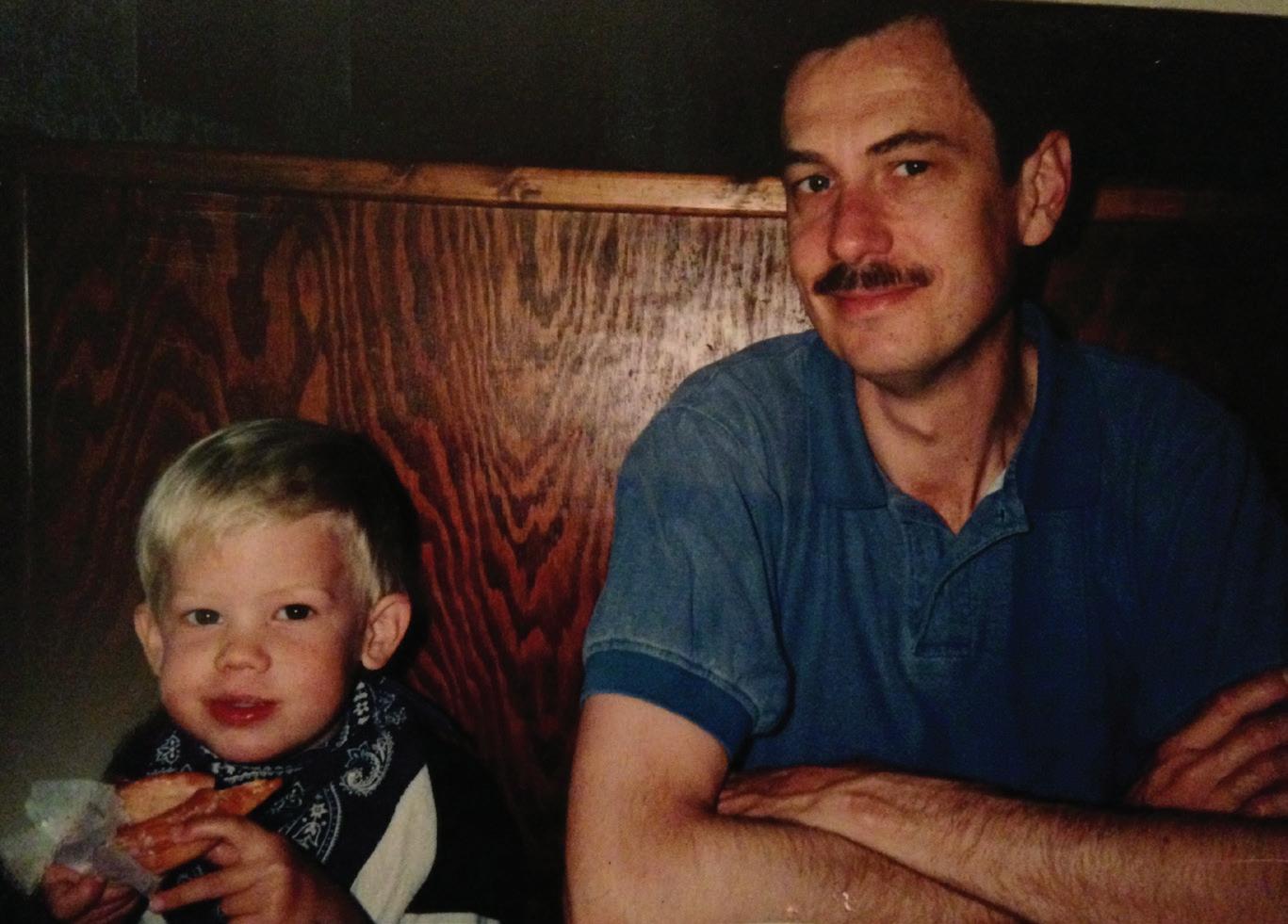

Among the objects that decorate Admissions Officer Korey Mack’s office—which includes dozens of photos, a variety of different plaques, and his high school diploma—sits a humble book: worn at the seams, with a torn leather sleeve born out of years of use and review. Emblazoned on the cover are the words ‘Purdue Football.’ The book may seem like a typical Bible for others looking in.

But for Mack, this Bible reminds him of a family: a family built on winning. Behind then-quarterback Drew Brees, Mack and his team dominated on one of the biggest stages in college football, winning the Big Ten Championship in 2001.

Mack’s entire life has revolved around the concept of family. His life began with family.

His immediate one was everything. He had his grandmother, who was likely the biggest influence in his life: a woman who had grown up on a rural farm in Centerville, Texas, and had taken the bold decision and opportunity to conquer the world. Taking her talents first to Booker T. Washington in 1949 and then to Prairie View A&M University in 1953, she catalyzed Mack’s journey, changing his journey 35 years before it even began.

Of course, his influences didn’t stop there. There was his aunt, who had taught at St. Mark’s for a while. His parents were his role models, and they seemed to know everyone. This connection with others carried onto himself, where Mack now tries to emulate the same level of influence on other people he meets.

“Years later, those small moments really made me think about their influences on my life and how I approach the world,” Mack said.

But though his family certainly played a major role in his development, they weren’t the only ones. When Mack thinks back on his time as a student, there is no reminiscing on grades, activities, or effort. There is no ‘I wish I could’ve done this differently,’ or ‘Maybe if I had put in a bit more work.’ His next family came in the form of boys: about a hundred of them, who, grouped together, were collectively known as the Class of 2000.

An alum shaped by and dedicated to family.

OREY MACK ‘00 K K

They were a group that shared everything with each other. They were a family, born outside each of their own blood relationships - a quintessential St. Mark’s class. Nearly thirty years later, these bonds have remained.

“We want to share [now] just like we did when we were students,” Mack said. “We want to share everything that’s going on in our lives.”

And even despite each of their individual growths, their group chat was still flooded with endless updates, photos, and conversation.

Updates for alumni events, for major events, and for total solar eclipses.

Photos of newborn babies, of reunited families, and of daring adventures.

Conversations that reminisce, which spark trash talk, and were barely different from the ones they had during their time at 10600.

“There’s a group of 18 boys—we’re men now—who are on a group text, and we text each other,” Mack said. “We text each other every day about something. We want to share everything that’s going on in our lives.”

And his bonds with the people of 10600 don’t stop there. He has his generations of advisees, who Mack routinely checks on, just to see how they’re doing. He has his colleagues, who encourage and spur him to challenge himself, each and every day. He has his four generations of senior buddies, ranging in years from Jordan Young ’11 to Osmond Cao ‘33. Mack’s journey through St. Mark’s is a spitting image of the Path to Manhood Statue: carried by his parents, grandparents, and his family, while carrying his buddies, advisees, and new student admittees.

“Every day is an opportunity to grow and mature in manhood,” Mack said. “It means the world to be at a place like St. Mark’s, to have the experience of others continue to influence mine.”

Story and photo by Dawson Yao

7

The spiritual leader with a newfound purpose.

KYLEA AWALDREP

8

A A

s Kyle Waldrep woke up sick in his dorm room on August 20, 2012, Walrep didn’t initially think too much of his illness.

But as hours turned into days of no improvement, he began to realize something more serious was going on.

After visiting the doctor, Waldrep learned he had contracted West Nile Virus, leaving him bed-ridden for the following week.

But hopes of a fast recovery quickly faded as Waldrep strangely lost short term memory as his condition only further deteriorated, later learning he had brain encephalitis, a rare form of brain inflammation in his case caused by his initial infection.

In just weeks, Waldrep’s ability to play six hour tennis matches out in 110 degree heat, his five minute, 30 second mile time had faded away.

To Waldrep’s dismay, he was off the tennis team weeks into his sickness, but at the time, his primary focus was regaining his own health.

“My whole world changed,” Waldrep said.

In the early months of his recovery, Waldrep remained confined to his bedroom, sleeping roughly 14 hours a day to provide his brain the opportunity to rest.

It would take roughly two years for Walrep to fully recover.

“The hardest part was having to figure out who I was again and what I believed in, where I wanted to be in life, who I wanted to do it with,” Waldrep said. “All those things into one.”

While his illness kept him out of physical activity and social interactions on campus for much of his early time at SMU, Waldrep turned to his faith, Christianity, to guide him through this challenging time.

Up to this point in his life, almost everything had gone the right way, and while he had always been a Christian, the first two years of college was the first time Waldrep’s faith was tested.

Rather than taking steps back on his faith journey during his illness, Waldrep dove deeper into his faith, embracing Christianity more than he ever had before.

Life had been good to Kyle Waldrep from his early childhood through high school.

Living in north Dallas with parents and two siblings, Waldrep enjoyed the nurturing environment he called home.

As the youngest of the three, Waldrep had the opportunity to look up to his siblings’ academic

“

The HARDEST PART was having to figure out who I was again and what I BELIEVED IN, where I wanted to be in life, who I wanted to do it with. All those things into one.”

-Kyle Waldrep

and athletic achievement, setting his sights on emulating their success.

Waldrep found a love for tennis at an early age, and heading into high school at Episcopal School of Dallas with the goal of playing at the collegiate level, weekly lessons and practice sessions became more frequent, and trips to tournaments around the country began to take up all of his spare time.

On those long weekend trips, outside of their respective hectic school and work environments, Waldrep had the chance to spend valuable time with his parents.

With his mom making sure he was staying on track of his school work and his dad reinforcing his focus on tennis, Waldrep could feel the pressure coming from all directions, yet these words of encouragement only fueled him to perform at his best.

It was great for my game,” Waldrep said. “I wouldn’t trade it for the world. It was fun. It was lively. It was energetic. We laughed. We cried. We drove on every Texas Highway possible and took every plane flight across the country.”

As tennis grew more intense and his shot at college athletics became more clear, Waldrep still found time to learn from his parents, recognizing their wisdom in his youth.

“My parents have nurtured and spirited the way they grew me up and taught me and loved me and given me opportunities and told me no,” Waldrep said. They have ultimately taught me how to learn, lead people and listen well.”

When the chance to take his game to the next level at Southern Methodist University (SMU) finally came, just a 20 minute drive from the home he grew up in with his parents, Walrep knew his work had paid off.

In the fall, heading off to college, Walrep was excited to begin the next chapter of his life while continuing his passion for tennis.

But on August 20, 2012, everything changed.

9

Story by Hilton Sampson

Photo courtesy Kyle Waldrep

Through his sickness, Waldrep made every effort to stay on top of his studies, and he was able to graduate with a double major in political science and communications in just four years, leaving him prepared to move on to his professional career.

While his classmates moved on to jobs at big accounting and consulting firms, Waldrep took a different path: founding his own business.

With the idea to make an easy workflow management software platform, Waldrep founded Dottid, and immediately went to work.

Over the past 10 years, Waldrep has raised more than 20 million dollars, hired over 40 employees and built his idea into a large scale company–all before the age of 30.

But it wasn’t an easy process.

For Waldrep, starting a business right out of college came with a learning curve.

“I had to learn how to fund raise, how to pitch, how to sell a vision,” Waldrep said. “I was making no money, living at home, and I cashed out my savings. I was either going to do it, or I wasn’t. I had to show up at people’s doors, put letters in the mailbox, and do all the things that I did to get it done.”

Despite all of his effort, challenges still arose.

The first time the Dottid product was brought out to be tested by the user, Waldrep received a troubling phone call.

“July 30, 2019,” Waldrep said. “At 3:45. I’ll never forget. Our product guy at the time called me and said, ‘our first user hates our product.’ Those were the first words. Not off to a great start. But that just led us to be really tenacious about how to build and how to listen well, how to understand what our product should be and why.”

By adjusting the model, Waldrep and his team set Dottid down a path to success. Walrep’s experience starting his own company has giv-

and learn from other business leaders, diversifying his own perspective and knowledge.

“Last September when I got to have breakfast with the Global Head of real estate for Blackstone,” Waldrep said. “I got to learn about how she views investing and sees the world and manages a family. Seeing someone at that high of a level in the business world, getting to have an hour long breakfast with her and her family to just hear, listen, absorb and learn was a really special day.”

But like any challenge Waldrep has faced, building a business has come with unexpected challenges, and he has found that as the direction of the company evolves, personal changes are sometimes necessary to maintain the best path forward.

“It’s hard having to let go of somebody that you’ve built a company with and worked hard with and who I’ve grown and who has also grown me,” Waldrep said.

As he continues to build and develop his business, Waldrep learns and grows himself.

Outside of his work life, Waldrep has emphasized continuing his involvement with Christianity. But outside of his own independent faith, Waldrep has become a YoungLife campaigners Bible study leader, guiding St. Mark’s high school students on their own faith journeys.

Having worked with students in alternating grades over the last several years, Walrep has become a valued member of the 10600 community and a trusted advisor for many students here.

TAKING THE COURT

While his collegiate tennis career was cut short, Waldrep spent much of his childhood on the court, and now in early adulthood, he still enjoys playing the sport.

Waldrep is a trusted mentor and friend not only to many Marksmen, but also other individuals in his life.

He was even entrusted in 2019 to transport a friend’s engagement ring from Nashville back home to Dallas for the engagement party.

Now, at age 30, working with a group of current juniors of the class of ‘25, Waldrep continues to garner trust, hosting weekly meetings at his home, where he leads discussions on faithbased applications of the Bible’s teachings to the group members’ lives.

“I want the boys to remember that I was someone that told them the truth,” Waldrep said. “That they came here and didn’t just hear what they wanted to hear, but they were challenged and edified and reviewed to know and understand truth.”

For his current stage of life, Waldrep hopes his legacy is that he worked tirelessly to build a great company and spend as much time as possible with his YoungLife group.

He knows it is difficult to have all the an-

10

Photos courtesy Kyle Waldrep

swers for his campaigners group members, but group member junior Henry Estes believes Waldrep always knows what to say.

“If you have a question, whether it needs a Biblical answer or not, he can point you to the scripture, call out the right chapter of the right book,” Estes said.

Estes has been attending Waldrep’s Bible study group since the fall of 2022, when a group of classmates joined Estes to participate.

While his father had initially coordinated the meetings with another parent to kickstart the group, Estes soon found that Waldrep’s imparting of wisdom was more than enough to get him hooked.

“It went from an obligation to a desire to go,” Estes said.

Over the past year and a half with the group, Estes has learned not only how to address issues in his own life, but also how to be a better friend to those around him.

Estes has been particularly impacted by a phrase Walrep often uses in the group sessions, “‘you are who you surround yourself with.”

Hearing this saying over and over has changed the way Estes views his relationships, giving him a broader perspective on the people he cares about, especially guys in the group.

“The guys are going through the same experiences as I am, the same struggles, so having a close group of guys I can have deep conversations with is important,” Estes said.

And the group of guys in the Bible study, Estes believes, are developing bonds that will outlive their time together in high school, creating a lasting connection they can all turn to and rely on.

“Kyle is someone who has gone through the same things as us, gone through the same experiences as us,” Estes said. “He tells us things he wishes he hadn’t done, or things he wishes he had done.

Like many in the group, Estes hopes he’ll stay close with Waldrep for years to come, developing their relationship even deeper.

In the meantime, for his YoungLife group, Waldrep intends to bring everything he knows to the table to move the group toward their ultimate goal of figuring out what they believe in and why –he’s just there to help them along the way.

BUILDING CONNECTIONS

Waldrep travels around the country to build his business, meeting with customers and investors (top). Waldrep attended the graduation of his YoungLife group members, fostering relationships he hopes will last a lifetime (bottom).

11

MARK

ADAME

The Biology teacher who isn’t letting anything go.

Story by Doan Nguyen

Photo Illustration by Joseph Sun

12

Mark Adame wants to be there for everything.

Behind his cheerful personality and playful demeanor, there’s a man who regrets missing some of the biggest moments of his life.

Too many times have things just slipped out of his hands. Too many times have there been people who trusted him, just for him to not show up. Too many times has he let things just slowly drift away.

And now, Adame has made a point to show up. Whether that be for something as mundane as classes, or something as fleeting as a once-in-a-lifetime solar eclipse, he’ll be there.

And maybe, just maybe, he won’t have to miss another moment.

Adame spent the first 12 years of his life on the move. First it was San Antonio, then an Air Force base in Florida, then Las Vegas — he attended primary school in Great Britain for a couple of years. A brief look into his scrapbooks and USB drives reveals years worth of fond childhood memories from all over the country.

But even with these unique experiences, moving can be a curse. Acclimatizing to a new house, scenery and faces gets tiring quickly, especially when Adame found himself stranded all the way on a different side of the nation every two years. Now, he holds on tight to every souvenir and gift he receives because as a child, he was always forced to let go.

“I keep everything,” Adame said, motioning to the walls of Hot Wheels cars in his office. “My wife is always like, ‘You need to get rid of it,’ but I can’t. I don’t want to.”

Both his parents worked exhausting jobs. His father was a navigator in the Air Force, and his mom was an English teacher. Each day at work sapped their energies. And after they finally returned home, they were met with four kids and a grandmother in the house. A sea of responsibilities filled their plates, but they tried their best to make everything work out.

But when Adame turned 12, he learned that it wasn’t working out.

“My childhood had stressful moments, mostly because my parents always fought,” Adame said. “Those were some bad days I’d love to get rid of.”

Adame and his siblings

stayed with their mom in Texas, and the children visited their dad in Florida every chance they could. The emotional separation hurt, but having a parent live a 15hour road trip away only made the sudden but inevitable divorce more difficult to handle.

His father was hard to live with. He’d grown up in a generation where making dinner and washing the dishes weren’t his problem. But despite their troubles, his father’s influence on his life is still very apparent: specifically on his love for the outdoors. Hiking, bike rides, sailing boats — they lived right out on the water and explored anything they could find.

“I miss the outdoors; I think about it everyday,” Adame said.

He doesn’t participate in triathlons and bike races anymore, but he still loves biking the 22.2 miles to St. Mark’s whenever he can, and Pecos is the highlight of his summer -- a love that stemmed from his dad.

But as Adame and his siblings started getting older, they visited him less and less, seeing him only once or twice a year. In 2022, Adame couldn’t see his dad at all anymore. His father passed away, leaving a void in Adame’s life that he was forced to navigate through.

“He drove me crazy,” Adame said. “But I miss the luxury of knowing that he’s there and I can just give him a call. He influenced my life the most, for better or worse.”

But in times of familial struggle, there was one person who was always there for him, a constant in his constantly changing life.

His grandmother was essentially his second mother. With two of his siblings in college and his dad a thousand miles from Tyler, Texas, Adame was the man of the house. Out of all of his family members, he was the closest with her. Throughout highschool, he lived with his grandmother, taking care of her as well as any highschooler could. He and his grandma fought and cried and laughed with each other just like teenage boys and mothers do. But after Adame left for Texas A&M University, his grandmother lived by herself for only a year before getting moved to a nursing home. When Adame was in his fourth year at college, he got a call.

“I heard the doctors moved her to a different room, which is never a good thing,” Adame said.

In the hospital diagnosed with old age and heartache, she wasn’t doing well, but it’s not like his grandma was gonna die. She’s been sick before, and normally this stuff just comes and goes.

Still, he drove the full three hours to Tyler from Texas A&M, and by 11:00 p.m. he was drowsily talking to his bed-ridden grandmother. He hadn’t seen her in a while, not nearly as much as he used to, so he ate his yawns and held his grandma’s cold hands.

“I remember her being scared to death,” Adame said. “She asked me to stay.”

But coming off a 150-mile drive was tiring, and staring at his grandma in her hospital bed made the thought of sleeping on his own that much more enticing. When the time passed midnight, he kissed his grandma, exchanged an ‘I love you’ and drove home with his eyes half-lidded.

Just three hours later, Adame woke to the news of her death.

“I hate that I wasn’t there,” Adame said. “I hate that she was alone.”

Whether he’s walking around on campus, teaching biology in his classroom or committing his early mornings to his passion for cycling, there’s always a lighthearted aura around him. He’s funny. Upbeat.

But even for him, there’s something else that lies behind his outgoing personality, lingering in the corners of his consciousness.

Despite the gravity of some of these thoughts, he lets his sense of humor shine whenever they happen to come up.

“Right now, I’m failing at keeping myself in shape,” Adame said, still managing to crack a joke and flash his trademark grin. “I’ve failed on that more than a couple times.”

Still, no facade can conceal reality: the pressure to meet others’ expectations, to make everyone around him laugh. To be there when needed.

There’s a constant presence. But when his anxieties emerge, they don’t dim the light of his optimism. Every time he wanders into his hidden insecurities, he grapples with them, and the twinkle in his eye overshadows his doubts. Nobody ever really notices the brief internal struggle — his personality brightens, uplifting the people around him, and he simply continues with the life he is so grateful to have.

13

SARAH

CHOI

14

Story and photo illustration by Arjun Poi

“At my new school, academic excellence was no longer valued,” Choi said. “I didn’t look like anybody else. The school was much more homogeneous, and so I really stuck out. I was made fun of for

But being bullied didn’t stop her drive

“It only solidified my desire to do

who were all interested in and excelled at their little things, in addition to being good at school. I was like, ‘Oh my God. I was not the only one.’”

Finally, Choi had found a group of people who were just as passionate about their interests as her.

“And then these were my people,” she

I’m not FINISHED, and I’m doing this job now. When I’m finished with this job, I think I still have OTHER THINGS I still want to do. It might be a job in healthcare or it might be something else. But I have not decided that that DREAM is over.

-Sarah Choi

academic pursuits. Over the summer, Choi picks up new hobbies to make use of her free time, like learning to row or curl. Even when she had to drag herself back into the boat after flipping the boat or wear enormous purple bruises after slipping on the ice, she gave 100 percent effort. Choi has more activities planned for future summers, whether that’s joining a handbell choir or playing pickleball.

“I feel that there is a lot more I still want to do, and I’m not worried about being uncomfortable, starting from the beginning, failing, or not knowing,” Choi said. “I think that stems back to when I was younger, and I was forced to be in situations that I didn’t want to be in, that were completely new, out of my control,

Even though Choi hated her elementary school, she says it made her more resilient. After her fifth-grade year, she stopped caring what others thought of

In high school, Choi quietly embraced her new role as one of the

One summer during high school, she attended a monthlong STEM camp, and from there, everything changed.

“I basically went to nerd camp,” Choi said. “And suddenly, I was surrounded by people

said. “That idea that you go out and do and find your people that whatever it is that you’re interested in, holy cow, that changed my life. Then that gives you the confidence to keep doing what you believe in, and you don’t hide it.”

For a brief month over the summer, Choi had at last found a community where she belonged. Luckily, she found a similar one when she switched from playing the cello at her local orchestra to playing for the Toronto Youth Symphony.

“Again, they’re high school kids my age, and not only are they amazing at their instruments, but they’re also doing well in school, or they’re athletes –– just super cool people. And then I was no longer the weird one. I was with other people like me. I was not an outsider. I was just one of them.”

Choi shares her advice for anyone who could be going through the same situation that she went through.

“You find the little thing that you have discovered you’re into, and you click with it,” Choi said. “And even if most people don’t understand it, you pursue it. And if you don’t have anybody else to talk to about it, you’ve got to then go and find your people. You’ve got to find the other people who are into that one little thing that you’re into, and that can change your life right there.”

“ 15

The Orchestra conductor who stopped worrying.

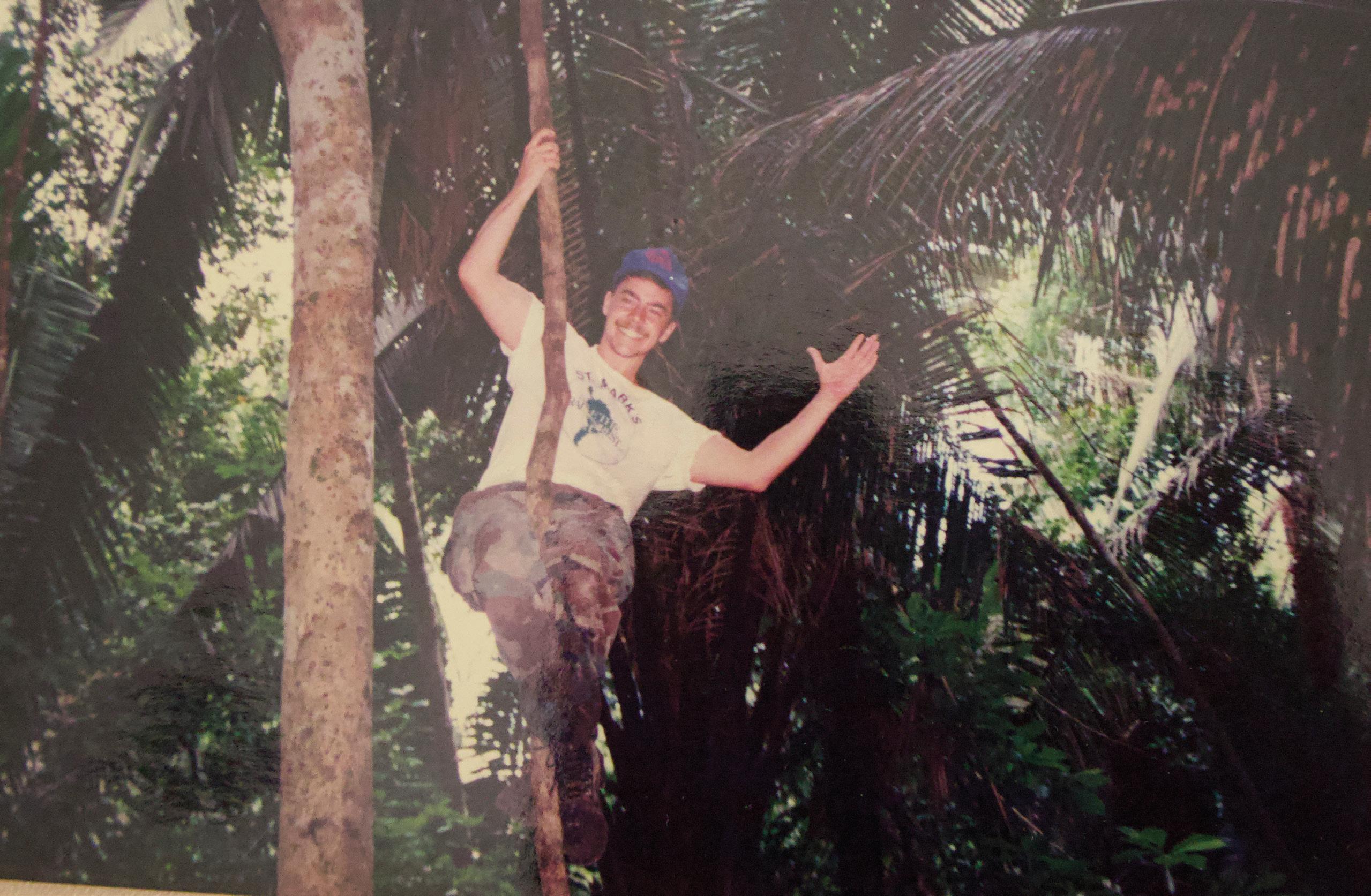

The former adventurer turned English teacher.

Story by Weston Chance

Photo by Winston Lin

The former adventurer turned English teacher.

Story by Weston Chance

Photo by Winston Lin

Chesterton. He believed that extended familiarity with an environment incurred boredom, and that an overly exotic environment tends to overwhelm.

Armed with Chesterson’s wisdom, a twenty-year-old Smith studied abroad in both France and Morocco. In France, he developed a keen interest in the French language, and in Morocco, he realized his affinity for an exotic environment.

In 1973, fresh out of college and hoping to fulfill his belief that national service is vital to developing young Americans, and also hoping to find an environment exotic enough to push him outside of his comfort zone, Smith enlisted in the United States Peace Corps.

Smith spent about two and a half years in the Peace Corps, primarily in a small village located in the West African country of Benin, then called Dahomey. Here, Smith could further explore the French language rooted there by colonization, and entrench himself in an unique environment.

It was almost 3 p.m. Smith’s lunch break was coming to a close. As he walked down the blistering-hot dirt road back to his school, he smelled something in the air. The atmosphere became thicker and thicker as he walked. A frantic commotion. Arriving at the scene and peering over the shoulders of his students, he saw it. Huge piles of ashes littered the ground where the classrooms stood just hours before.

Why would kids do such a thing? Why would they attack their own school?

In the ensuing months, government officials from both the village and the capital met to uncover the truth.

After vigorous investigation, the school board made the shocking realization that the children were coaxed into these protests by their own parents, who resented the tribe of the school’s new headmaster.

At the time of Smith’s residence, Dahomey was just the size of Kentucky, yet it possessed upwards of 50 different tribes with their own unique languages. The school’s headmaster was capable and intelligent, yet because he was of a different tribe than the majority of the area, many villagers resented him.

The people of Smith’s village set themselves back by dwelling on their differences rather than their similarities. They all wanted the same thing, for their children to learn, yet they quite literally set that opportunity ablaze because they saw the headmaster as different and as an outsider.

The protests that occurred at Smith’s

school and the following investigations led Smith to appreciate that similarities in a community must outweigh the differences and to recognize that we are more alike than we often believe. Different languages, cultures, tribes, and location do not change the fact that we are all a part of humanity.

“I think going to the Peace Corps in Africa was what enabled me to solidify the idea that yes, the self is important, but others and people who are different from you are also important,” Smith said. “And a part of this whole wonderful world is that we need to take care of other people, and not just ourselves, not just our families, not just our neighborhood, not just our schools, not just our cities, not just our states, but everyone.”

During Smith’s year career at St. Mark’s, he strove to instill that lesson in his students. And while he always acknowledged the differences between Marksmen, he understood that everyone in the community possessed the same intellectual curiosity and in that way were alike. It was this fundamental belief that helped Smith to so thoroughly enjoy his tenure at 10600 and to become a school legend.

“He served the needs of a lot of different people,” Cecil H. and Ida Green Master Teaching Chair Scott Gonzalez said. “For example, he wanted and still wants to give students in the Dallas public school district, who just need to know they could be successful, the opportunity to engage in an academic program here at St. Mark’s.”

As part of this program, Smith enlisted Marksmen to partner with public school students to perform community service work. Together, they formed boat crews and headed out on the Trinity River to collect trash. Gonzalez, who developed not only a professional bond, but also a close, personal friendship with Smith, sometimes came along to the Trinity clean ups.

“There were some kids who had some real opportunities and then there were some that didn’t necessarily have as many, but when you get out there on a boat, and you got to work together in the Trinity, which is not the easiest river to traverse, nor is it the cleanest, I think it makes you start understanding that we’re all in this together,” Gonzalez said.

So whether Smith was traveling down the Trinity River in Dallas or the Niger River in Africa, he was always armed with his MO. The fundamental knowledge that regardless of how unique an environment may be, we are more alike than different.

17

The art historian turned doctor because he wanted to make an impact.

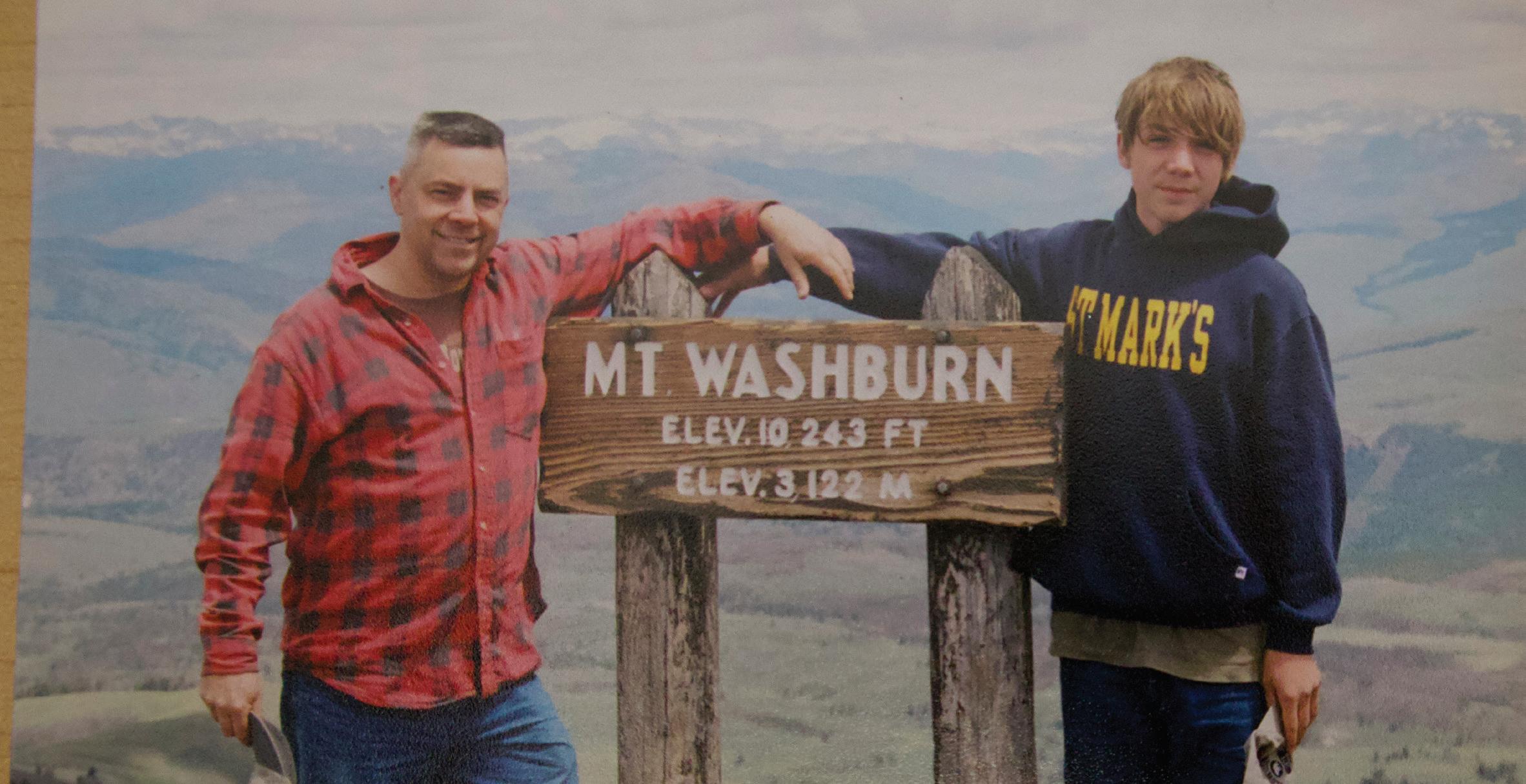

HIS WINDING PATH

Carlson received his first “white coat” after deciding to switch to medicine from art history (top). Carlson at Cory Martin’s first SPC championship (middle), and he’d invited Martin to his wedding (bottom).

A

Story by Linyang Lee

Photos courtesy Scott Carlson

Story by Linyang Lee

Photos courtesy Scott Carlson

18

AAlot of parents were skeptical when Scott Carlson ‘05 came into town. Who’s this privileged kid who doesn’t know anything about Galveston to come down to teach and take care of our kids for 10 hours a day? Who does he

Carlson didn’t really know who he was either. He was fresh out of Princeton with a degree in Art History, and unless you count volunteering as a camp counselor, he didn’t have any experience teaching or working with kids.

But there he was on the first day of school. In a new school he’d helped form in the wake of the Hurricane Ike, in front of 24 kindergarteners with attention spans he guessed were no longer than 23 seconds, and in the dilemma of how exactly he could best “escort” a screaming, kicking and crying 5-year-old to the principal’s office for attacking another student. What a first day.

Throughout much of college, he’d thought he was going to pursue a PhD in art history and teach. But something about spending so much time in the art library reading and writing didn’t really feel right. He started to feel like he was keeping himself in an ivory tower — disconnected from the world.

And especially when he talked with his parents about what they’d done in each of their lives, with his mother about teaching and father about criminal defense, he just felt this itch to pursue something more socially engaged.

Teach for America and the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) had been advertising and recruiting heavily around campus, and Carlson wanted in. It gave him the opportunity to spend a year or two teaching in an underserved area, letting him get an idea of what life was like outside his bubble. It also gave him time to think.

He took an offer to teach at a new charter school in Galveston that was starting up to help draw families back to the island after Ike had hit — because it had been devastating.

Even as Carlson went door to door recruiting through the neighborhoods the summer after the Hurricane had hit, there were people in the summer who still didn’t have windows or a front door.

And paired with the 2008 recession, Galveston struggled. Parents would ask Carlson all sorts of questions that he didn’t know how to answer.

Where can I get dental care? Where can I get health care?

It was hard to hear some of their stories. What they’d lost. What they needed.

It was also hard to gain their trust.

He had to make school fun for the kids, but he wasn’t there just to be their camp counselor. He was there to be their teacher, and he had to teach them a lot too. His task? Bringing each and every 5-year-old who could barely stay in their seats from totally non-proficient readers to avid ones.

He taught 10 hour days. And he was pretty much isolated in

a community where he barely knew anyone. He would work weekends and some more after school too, taking time to do the extra curriculum planning and to talk to families about how their kids were doing in school.

If the kids got lice, Carlson got lice. If the kids got ringworm, Carlson got ringworm. It’s just the nature of being an early-age educator.

It was the hardest year of his life. But, looking back, it was one of his most formative, rewarding and eye-opening years.

That 5-year-old kid who’d had a tantrum the first day of school didn’t have much by way of resources at home and had really started out, from an academic perspective, at zero. He hadn’t had the luxury of parents or grandparents reading to him at home. And yet that same 5-year-old who’d cried, screamed kicked his heart out soon became one of Carlson’s best students.

That year showed Carlson that anyone can be taught intelligence and perseverance. Everyone has the same potential.

And even though it was tough, he knew he wanted to continue making an impact on an individual level in people’s lives.

“

I was spending a lot of time reading and writing in the ART LIBRARY, and I would come back home and just started to feel like it was a an IVORY TOWER experience.”

- Scott Carlson ‘05

It was pretty isolating not having people in town to talk to, so he’d been making the 4 hour drive from Galveston to visit his friends in Dallas pretty regularly. His friends were at UT Southwestern and would tell him about medical school — what they were learning, how it was like working with cadavers, and what it was like seeing patients in the hospital.

College was almost a sort of science break for Carlson. Having spent so much time with STEM in high school, he wanted to pursue areas and fields he hadn’t been able to study — sometimes responsible for some of the lowest grades he’d ever gotten in life.

But he missed the sciences.

To most of his friends and family, he was crazy for suddenly pivoting from writing Art History PhD applications to finding out how he could do a post-baccalaureate and start any pre-med courses he would need.

To Carlson though, it was the right choice. The physics and biology courses he was taking affirmed that.

As part of Carlson’s learning, he also shadowed and watched how the supervising physician at the Agape Clinic, a free clinic where any patient could walk in or make an appointment, regardless of whether or not they had insurance, worked. And just seeing the way he interacted with patients, his breadth of knowledge and his intellectual curiosity with which he approached basic primary care — Carlson knew that was how he wanted to practice medicine.

19

20

Photos courtesy Scott Carlson

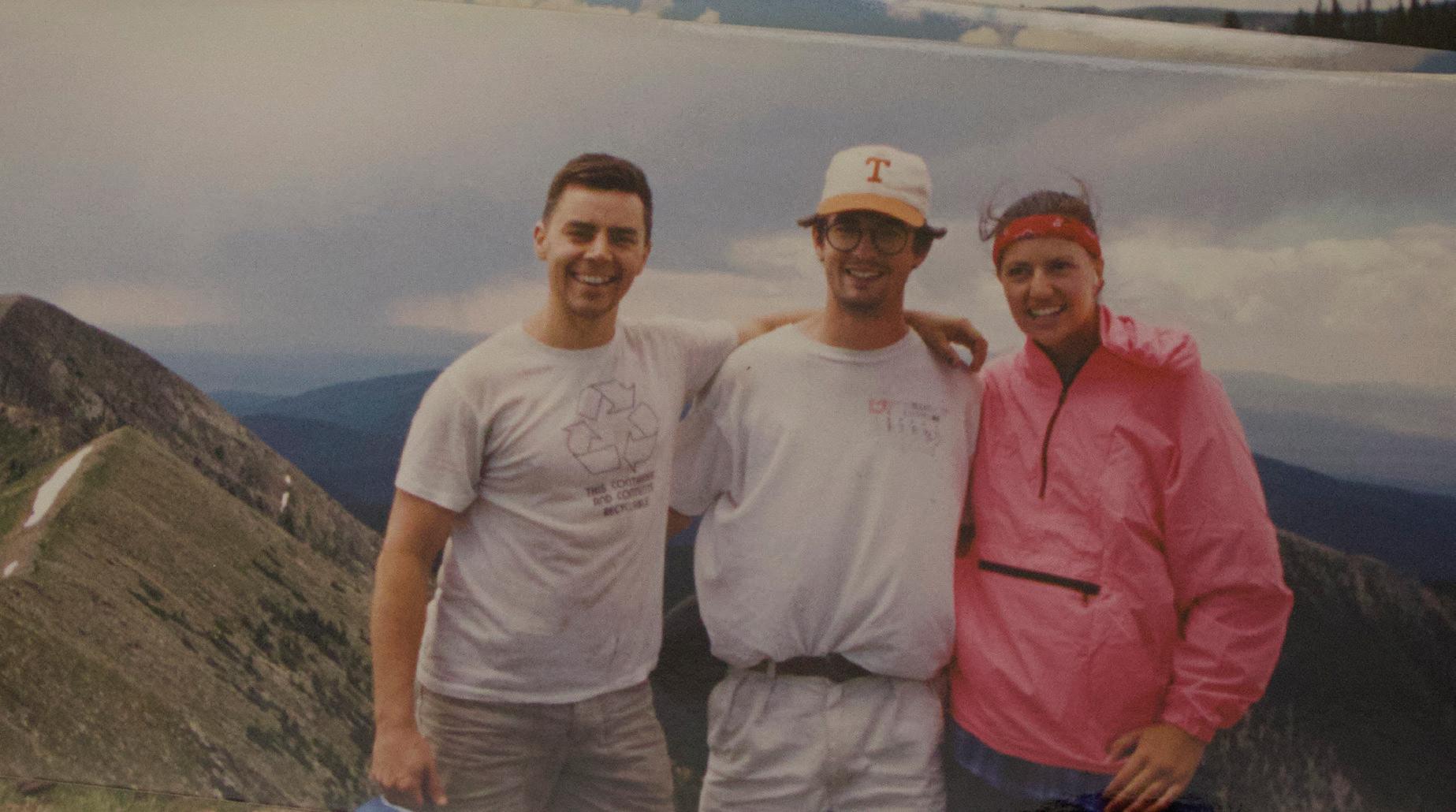

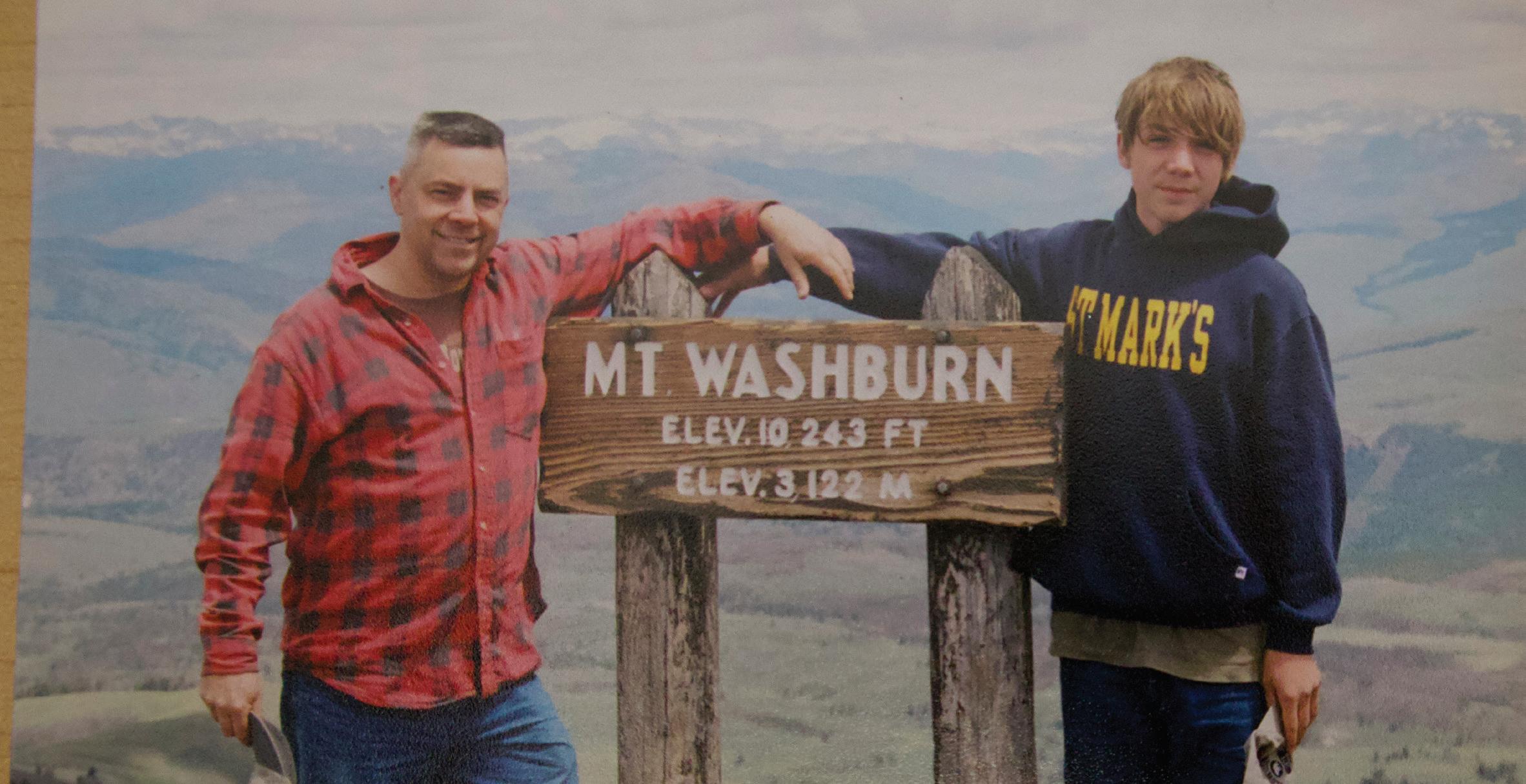

A JOURNEY OF A LIFETIME

A young Carlson with his dad (top left). Carlson love for music began as a child, and he took up the guitar (top right). Carlson at his wedding (middle left). Carlson with his new family (center). As an only child, Carlson grew up trying to get attention from his cousins (middle right). Scott Carlson became an endocrinologist by chance and had originally wanted to be an art historian (bottom left). Many parents told Carlson their children would miss his classes (bottom center). Carlson with Martin (bottom right).

The supervising physician was an endocrinologist and dealt with all things related to hormones — diabetes, hypertension, PCOS and amenorrhea. And with his expertise, he taught Carlson and the other volunteers how to become masters of treating patients with these conditions. That was when Carlson wanted to be an endocrinologist.

It gives Carlson the opportunity to do a lot of primary care and work with people of all walks of life. It gives him a chance to help people feel their best. It gives him a place to impact people every single day.

A fourth-grade Carlson wasn’t quite sure what drew him to Cory Martin.

Martin, varsity soccer coach and math instructor, was coaching Carlson’s fourth grade soccer team — and he could get pretty intense.

All the fourth-graders were amused by his sense of humor and terrified of him on the soccer field too.

“He’s someone who’s intensely passionate about life, whether it’s music, math or soccer,” Carlson said. “He’s someone you can hear through the walls.”

Even now, over 20 years later, you can still hear him through the walls.

I like fishing grandpa!

POIII!

Carlson’s favorite saying was just the way Martin could be a lyrical repository — his ability to just throw out song lyrics that fit whatever situation he was in.

Carlson had once prided himself in being a lyrical repository too — a human Shazam. Bob Marley, Reggae, blues, you name it, Carlson thought he could name any song. Martin introduced him to one of his blind spots though, and introduced him to U2.

He brought Carlson to his first concert — a U2 one, probably Carlson’s favorite band then. He would bring Carlson and his other advisees to lunch all the time.

Carlson just felt that Martin cared.

Martin was almost like a third parent — someone who he could seek, be mentored by, ask for wisdom — without the barrier of all the ways teenagers can feel at odds with their parents time to time.

Sure, Martin taught Carlson Algebra. He taught him to learn about a system and to understand how it works instead of just relying on memorization. It’s how Carlson works in endocrinology today — understanding the process.

But Martin taught Carlson how he wanted to carry himself — to do the best that he could in his job, as a friend and to his family whether the spotlight was on him or not.

It’s not about the accolades. It’s not about the recognition.

One poster on Martin’s wall sticks out to him.

He who dies with the most toys still dies.

And out of high school, Carlson would ask Martin about those

One of the hardest things about FAILURE is it’s a painful and HUMBLING experience. But it’s only humbling if we ALLOW it to be and learn from it.”

-Scott Carlson

‘05

big transitions in life — those more challenging things in life. Going off to college. Finding a job. Having relationships.

Just the other day, he had an errand to do and figured that he hadn’t called Martin in a while. The next thing he knew, he was already back home, 45 minutes later, his wife was giving him a look that said, ‘Hey, I need help with our one-year-old,’ but they were still chattering away like not a minute had passed.

“There are people that you meet in your life who you feel like if you’d been born at a different time you would have always been best friends,” Carlson said. “That’s the way I feel about him.”

His Citizenship Cup sits on a bookshelf in his office.

The J.B.H. Henderson Citizenship Cup is awarded by the faculty and presented by the Head of Upper School to the senior who has genuine concern for others and is dedicated to the ideals of honor and justice.

Seeing it there everyday, in the office that’s become a second bedroom because of his son’s nursery, reminds him to live up to the values he’s set out for himself in the craziness of life.

Have I really been a patient dad to my whiny one year old today? Was I a good enough listener to my wife last week?

Because sometimes, Carlson can forget. Like in his senior year of cross country.

Carlson had been injured for half the year, but he’d come back and at the SPC final, he’d performed better than the other two cross country seniors — two of his best friends.

He’d assumed that there were going to be three captains — there’d been three captains the last year after all.

There would only be two that year. Carlson was not one of them.

How could this be? I performed when it counted?

But Carlson didn’t build the relationships with the underclassmen like he could have. He’d been absent for a lot of the long runs. He just thought that he could earn it by default.

“One of the hardest things about failure is it’s a painful and humbling experience,” Carlson said. “But it’s only humbling if we allow it to be and learn from it.”

Carlson finished his endocrinology fellowship last year. Now, he’s moving back to Dallas to work at Baylor in his first year “on faculty.” He’s been in school for 28 years now. For him, having worked so hard for so long and being able to see the next phase of life, he knows he might fall into the trap of taking things for granted. And as a new parent with his one-year-old and a wife of seven years, he knows it’ll probably be easy for him to be impatient.

And if he could have one wish, it would be the infinite capacity to have patience and listen.

Because he knows he’s going to be needing a lot.

“

21

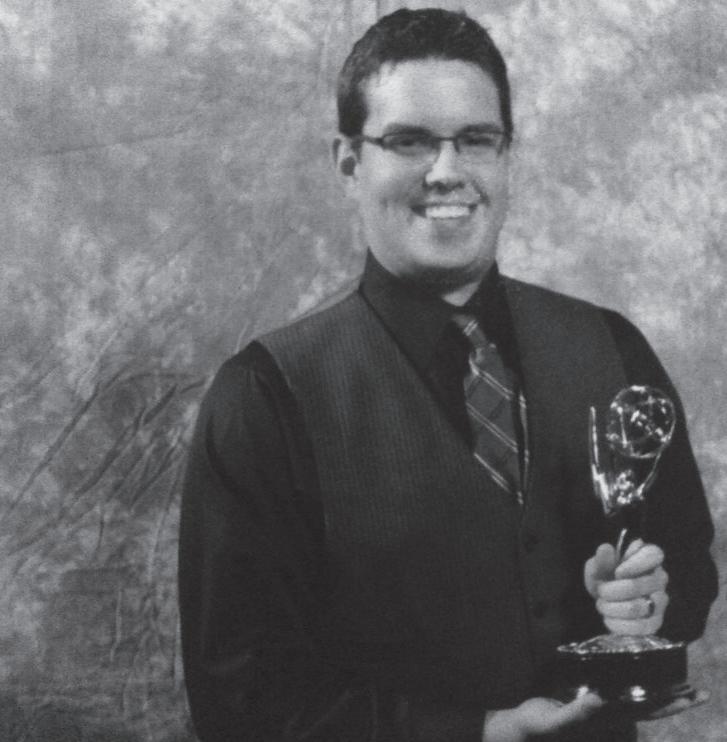

D DAVE CARDEN

Dave Carden is not worried about missing a moment.

He will never have to think hard to remember an event or rely on others’ stories; he captures every moment himself. Whether remotecontrolling a drone camera over pickup soccer games in the Quad or filming his daughter opening gifts from Santa, there isn't a moment where the school's Creative Director is without a camera of some kind. With phone at home and cameras at 10600, nearly everything he sees is documented in some form.

And he likes it that way.

"Obviously, it's my job to document things at school," Carden said. "But I find enjoyment in that. [Wanting to capture every moment] is not something that you just lose when you get home. I feel like it naturally seeps into my personal life."

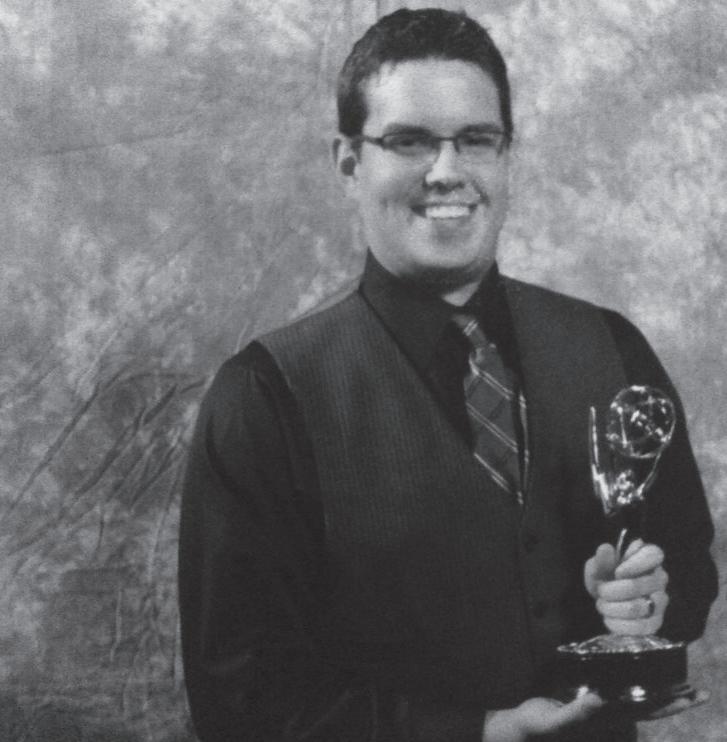

Carden joined this community in 2011 as the Assistant Director of Communication after graduating with his Bachelor's of Arts in Radio, Television and Film from the University of North Texas. While there, Carden worked for the school's ntTV network, where he rose to the rank of News

The personality behind the camera.

Producer and Senior News Photographer. In 2010, his work on ntTV earned him a Lone Star Emmy for Student Production.

But despite his technical knowledge and hands-on experience, nothing could prepare him for trying to tell the story of this community.

"I had a lot to learn," Carden said. "You're kind of thrown into this really unique space. And my job was to tell the story of that space, but I didn't really know it. And it's hard to tell the story of a space you don't know. Katy Rubarth helped me grow into that."

Katy Rubarth, the former director of Communcations, hired Carden to work under her to help create content for the school. Joining the community first as a parent to three sons and then becoming a part of the administration, she knew the school really well and was able to help him find his footing at 10600. She transformed his mere skills and knowledge into true storytelling ability.

"She basically taught me everything I know now," Carden said. "When you don't fully understand St. Mark's, it can be hard to capture the best parts of it. Mrs. Rubarth helped me find those parts and capture those moments."

Part of Rubarth's teaching was giving Carden freedom to tell stories as he saw fit. Of course, this liberty led to some early mistakes, but she saw them as an integral part of growing. She never let Carden feel isolated or vulnerable after his missteps.

"Sure, I made some mistakes," Carden said. "I did somethings I should not have and didn't do somethings that I should. But she never let me feel like the mistake. If it ever got to administrators or other people, she helped cover for me. She used mistakes as a lesson, not a weapon."

Although Carden is commonly known on campus as "the man with the camera," he feels like both members of the 10600 community and his family and friends don't fully understand what he does and why it's important.

"I feel least understood in that I don't think people get what I do," Carden said. "I'm more than a photographer.

22

It's not that simple. My wife is a teacher. People ask her, "Oh, what do you do?" She responds "I am a teacher," and they get that. People don't fully understand what a Creative Director does. They don't get what stragetic communications or school development is. I don't think a lot of people at school understand that either. I'm a storyteller."

The biggest plot twist in his personal and professional life came when Rubarth passed away on Feb. 4, 2021. Her death came after a long battle with cancer. After having a close relationship with his mentor of more than a decade, Carden would enter a new era of his career at St. Mark's where he would be without the woman who gave him his start at the school and empowered him to tell its stories.

"Mrs. Rubarth's death was a shock to my life," Carden said. "I had grown the most working with her and trying to do the job she taught me to do without her was hard."

Luckily for Carden, another important lady emerged in his life before Rubarth passed away. He and his wife Kristi, who were married in 2010, welcomed their daughter Kate in June of 2018. This gave Carden the opportunity to capture the equally important moments in his personal life.

"It's been fun to take photos of all the things we've do together," Carden said.

One of the experiences that he cherishes the most with Kate is Christmas. Watching her open presents from Santa and decorate cookies has brought him immense joy over the last few years.

"[If I could relive one day in my life], it would be Christmas with Kate as a 5-year old," Carden said. "She's at the age where magic is real and where Santa exists, the Easter Bunny exists and the Tooth Fairy exists. That's fun for me as a dad to watch her enjoy all of it. I would not want to relive Christmas with Kate as a 1-year old. That was chaotic and wild."

As a content creator and natural storyteller, Carden began documenting these moments with Kate and their dogs Arya and Rhysand (named because of Game of Thrones and ACOTAR, respectively). His followers on Instagram and Facebook have responded well to his daughter and the dogs.

"I'm not a social media guy, but I do post my daughter on Instagram sometimes," Carden said. "When I take a picture of my daughter doing something, I get more likes on those posts. I also post our dogs which I think some people like, too."

Carden's love for his own pets in real life extends to a passion for dogs on screen as well. His family loves the show "Bluey." "Bluey" is an Australian animated television series made for children. The show's titular character is a joyous, energetic and imaginative 7-year old blue-heeler puppy that the Carden family has fallen in love with."

"You know, the chances of me ever getting a tattoo are slim to none, but if I had to, it would be of Bluey," Carden said. "I think I would get matching tattoos of Bluey and Chilli with my wife."

Between his personal and professional lives, almost every single thing that Carden sees or experiences, he captures with a camera and stores on his hard drive.

"If there was a fire and I had to save one thing, it would definitely be my computer," Carden said. "Everything is on there. I don't feel like I miss many moments. Pretty much everything I see or do, I have. It's all on there—work or otherwise."

Carden doesn't spend a lot of time thinking about huge causes, metaphysical meanings or big fears (although he is deathly afraid of roaches). Instead his wishes and aims in life are simple.

"I'm not to good with the big questions," Carden said. "I just want to be a good dad. I want to be a dad my daughter can be proud of. I want to have fun with my family and never miss a moment."

Story

Noah Cathey

“ I don’t feel like I miss many moments. Pretty much everything I see or do, I have.

-Dave Carden

and photo illustration by

23

Officer Doug Brady was on alert that morning. He’d gotten the report from the evening unit, and the situation looked bad.

Six hours ago, the department got a call - it was a barricaded person with hostages.

Patrol units sped to the scene. A few officers made their way into the apartment.

Under the dimming street lights, there was silence. Then, shots. Three officers were hit. The others reported back. Two people were already dead. An exwife and three young children were held hostage.

The evening SWAT unit positioned itself. The suspect was prepared for a shootout. Through the night armored men moved about furtively. Then another wave broke upon the house. Deafening sound–gunshots, shouts, screams, bangs–then calm again.

Brady’s unit took over. Brady stood in the tension with his officers, pacing, whispering, readying themselves, feeling noise and light swell around them

Then it all erupted.

Brady rushed in with his officers. He fought through the gas, stepped over bodies, cleared hiding spaces, heard shots, called for backup–then was face-to-face with the suspect. Brady pulled the trigger, and then felt his arm go slack.

Now, a little over 20 years later, Brady gingerly moves his hand down his right shoulder and traces a long raised scar down to his forearm. When asked about the wound, he brings his shoulder around and raises his elbow up.

As you take it in, he himself looks it over as if in

mild disbelief, following the jagged cuts with keen eyes.

Then he grins a little, and he marks out his arm chunk by chunk and tells you the surgeries done to each one: here, there’s a steel plate about this wide; there, they sewed the skin back together.

“Oh, I’ve also got photos from the doctors of the screws going between the plates.”

And then he rolls his sleeve back down and says, “That changed my life for the better.”

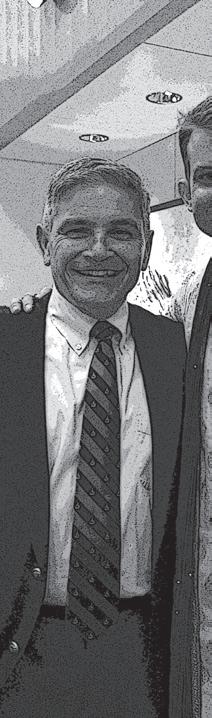

Doug Brady joined the school security staff in 2019 after 27 years of work with the Dallas Police Department in the Special Operations SWAT Unit and the Gun Range. A tall man with an imposing frame, he’s now best known for his gentle guidance of the rough morning traffic that flows through the chaotic mess of a parking lot each morning. Amid students hurrying tirelessly to avoid tardies, Brady’s steadfast demeanor and friendly Southern accent has made him a welcome sight to each weary student.

But even now, at 63, behind good-natured features lies a sharp mind and a spirit that burns as doggedly as it did 50 years ago when he was a young farmhand.

Brady grew up on 6,000 acres of open land around six siblings, slow grazing cattle, blazing yellow wheat and the roars and whistles of dusty wind that carried the song of equipment and his father’s voice, calling to pick up the pace.

24

Story and Photo by Kayden Zhong

BRADY DOUG

25

The security officer caught by crossfire.

B

26

Photo courtesy Doug Brady

HBe shifts a little, stretching his arms, the muscles rippling. Apparently, spending your childhood carrying pails and working cattle is one of nature’s most effective bulk plans.

Strength made him cocky, Brady continues, shaking his head. He didn’t care much for education. Often, he contested his siblings in scrappy games of basketball, roughhoused them in games of football, left dust in their eyes in races.

But he was respectful about it, of course. His mother, a third grade teacher, taught her children the Bible. Every word she spoke was carefully chosen, meant to instill ethics, tradition and proper behavior. Every Brady child knew better than to do something rash in front of Mom. Brady laughs. His father taught him to drive when he was in third grade.

But sadly, life on the ranch would have to end. During Brady’s eighth grade year, in the middle of Christmas break, the family up and moved southeast to Mineral Wells. And as someone who felt as though his life had been ripped away, Brady took it badly. Mischief turned into rebellion, pride transformed to arrogance, troublemaker became troublemaker-in-the-principal’s-office. Neither parent knew what to do.

Brady stops, turns. You can’t see his eyes, but you feel their pierce.

“I think it was the Holy Spirit.”

He pulls his sunglasses off.

“I can tell you exactly what the Spirit told me. He said, ‘You shut your mouth. You’re bragging, you’re being arrogant, just because you can play sports. You’re proud in a bad way. Change that.’”

So Brady changed. He excelled. By his graduation, Brady had a long list of athletic achievements that sent him to North Texas State University with a full scholarship.

But he still didn’t care about school. He goofed around while he was there. After two years, he was gone. Once he regretted that, he went to Cameron University. Then he met his wife, and he left again.

Brady brushes his forehead.

Now, there’s some gaps here,” he admits. “But in 1992, I joined the Dallas Police Department.”

He swept through his patrol time. When it was time to specialize, he went straight to SWAT. Now, Brady could box for something nobler.

By early November of 2003, he had been a part of the SWAT team for six years.

He’d seen a lot already, and he wasn’t exactly excited about this call.

But when the tear gas went in, he too charged in with his men. He strode through the hazy rooms, gun at the ready, tense, waiting for a shout, a sign.

Then he was looking right at a man clutching a gun.

“I ended up confronting that guy,” Brady said. “Actually ended up having to shoot that guy.”

Then Brady felt a searing pain in his right arm. He clutched at it, staring at bloody strips of muscle and white bone where a dark sleeve had been moments ago.

The fog overwhelmed him. Brady knew he was being rushed to the hospital. Unfamiliar faces hovered in and out of his vision.

When the surgeries were completed, Brady’s arm was completely different. His strength was gone. He felt the metal plates they had screwed in. His skin was unevenly cut with holes and marks. Apparently his shattered bones had been replaced with cadaver bones.

Recovery took a long time. He occupied his time with basic exercises and thought about the future. He’d be a left-handed shooter now. Maybe he needed to learn how to snipe. Above all else he would have to work his arm back into a usable condition.

So he started over. After a while he could lift weights again. Then he adapted his shooting form, and before long friends were asking him when he would go back to SWAT. Brady wasn’t so confident.

In the middle of working out one day, Brady thought it was time to move.

“I could’ve passed the SWAT test and everything else required but for me, I just wasn’t full speed,” Brady said.

So he went to the gun range. Now, he had to learn. Dallas was one of the first to adopt the usage of patrol rifles, and Brady needed an instructor’s license.

He threw himself into the manuals. It was one of the few times he had enjoyed learning.

Then, the gun range also wanted somebody with paramedic or EMT qualifications present. They asked Brady if he’d be willing.

“You know what, that’s great,” Brady said. So he got that training.

“Going from no education to two qualifications,” Brady motions a gap with his hands. “There’s this change in my atti-

tude towards education.”

One day, a large gruff man pulled Brady aside while he was training recruits. Brady had talked with Captain Jack Bragg a few times before, but why he wanted to talk now Brady had no idea. Bragg clapped him on the back. Good to see you, hope you’ve been well–normal from Bragg. Then, voice lowered, “Is it true you’re only 26 hours away from your bachelor’s?”

Brady hadn’t even given his degree a second thought after he left Cameron. Sure, he was 26 hours away, but he had kids to worry about. To Brady, they mattered more, and he let Bragg know. The captain shrugged.

“He never stopped asking,” Brady chuckles. “He said it was just like eating an elephant, one bite at a time.”

And Brady felt empty enough once his boys went off to college.

He called up his old counselors at Cameron. They asked Brady what he wanted to do his last hours in.

“I’m police, so I go ahead and ask them if I should get my degree in criminal justice,” Brady said. “Then they were like, ‘no, don’t do that.’ I had gone to school in physical education and they said just to finish that degree in physical education, get your bachelors, then you can do what you want.”

He laughs, and leans in a little closer.

“I walked off that stage with my bachelors at 50. When I saw Captain Bragg next and told him about it, he loved it,” Brady smiles. “Actually, when I retired from the police, I wanted to coach.”

Instead, he kept learning. He went to Grand Canyon University and decided that he wanted a masters in general psychology, and he got it.

“I always wanted to know what was going on with the mind. Very interesting stuff, and it got me thinking.”

Then he decided he wanted to study criminal justice. He left the police in 2016, and started taking courses again. Now, he’s only a mere 15 college credits away from starting on a PhD dissertation.

“So I’ll take a break after that until October.” Brady’s eyes grow dreamy. “Lord’s will, I'll pick it back up then, so by April of next year I should be all done with the dissertation.”

Brady touches his elbow, rubs his eyes. Dr. Brady. That’s a different sound. Nice one, though.

27

Lorre Allen

The Director who cares.

The bedroom was completely dark and cold, the fan spinning at high speed above the beds of D’Andre and Darius Allen. All was quiet throughout the house. Outside their sons’ door stood Lorre Allen and her husband Mark. In their hands was a large hose sprinkler attachment, the green serpent of the hose snaking through the house and out to the back porch spigot behind them.

Silently opening the door and dragging the thick green hose quietly behind, the couple snuck into the center of the room and placed the sprinkler on the floor.

Next, with the flip of the hose handle, the couple unleashed joyful havoc, water erupting out of the sprinkler, dousing the room and its occupants.

The boys leapt out of bed, water streaming down their bodies and comforters half-wrapped around them. First confusion, then smiles spread across their faces as they looked at their drenched parents laughing in a happy moment of family horseplay.

This simple prank, just a single memory, characterizes Lorre Allen. She is someone who loves people. Someone who loves to have fun. Someone who builds connections. Someone who cares. And this care led her to the position of Director of Human Resources at the school. A position that has allowed her to take her love of family and relationships into the workplace to contribute to the community.

Allen’s love for others was a quality that was nurtured by those surrounding her in her youth. Born and raised in Detroit, Allen grew up as an only child. She describes her childhood in three words.

The absolute best.

And to Allen, four memories, beginning in her “amazing” childhood and ending in adulthood, define her life. A life full of music. A life of family bonding. A life full of faith. A life of caring of others.

1 2

Music is one of the most important factors in Allen’s life and is something that still strongly influences her to this day. And one artist stands above all in her mind: Prince. Avid cannot do justice to her love for Prince.

A massive Prince fan since the 70s, Allen has his first album — For You — on vinyl. For Christmas, despite her mom’s disapproval of Allen’s love of Prince, Allen walked downstairs and saw the distinctive shape of a vinyl album under the Christmas tree.

After unwrapping the present and opening the box, Prince’s second album on vinyl rested in her hands. This was one of the best Christmas presents ever.

So when Prince announced his Purple Rain tour and included Detroit as one of the cities, she immediately asked her mom if she could go get tickets. The catch: the tickets were being sold during school.

Deciding to err on the side of caution, Allen ended up staying in school, sitting through the entire day, and going home like usual, with no Prince tickets in her possession. She was extremely saddened. But despite a torrential downpour that relentlessly soaked the city the entire day, Allen’s mother waited in the long line, soaking wet, to buy two tickets for Allen and her cousin.

A profound example of familial love,

Allen’s mom’s selflessness instilled a powerful example within Allen’s mind. It inspired a deep desire to give back to those whom she loves. This facet of her character is something that she strives to exhibit every single day. And it all began with her love of one of the most influential and popular artists of the 20th century.

With typical heavy snow falling in the wintertime in Detroit, Allen lay in bed, bundled up in warm covers. Suddenly, her mom walked into the room and told her to get up quickly.

Hurrying Allen to get up, who was only wearing her pajamas and a coat, Allen’s mom led her outside into the bleak frozen land of wintertime Detroit.

Crunching their way into the center of the front yard, Allen’s mom

In that one moment, I knew I wasn’t a kid anymore. Lorre Allen “

Story by Matthew Hofmann

28

Photo by Zachary Bashour

turned to Allen and introduced a new tradition.

“‘We’re going to make some ice cream,’ she said,” Allen said.

Scooping the top layer of snow from the ground, the two created big piles of fresh powder before returning inside and flavoring it, creating homemade ice cream. This memory fully demonstrates the spontaneous environment Allen grew up in, taking each moment for what it was.

But in comparison to the wisdom of her mother, the snow ice cream itself was not nearly as meaningful. When describing why she made the snow ice cream, Allen’s mom created a beautiful metaphor for life.

“You know how important the top layer of snow is compared to the bottom layer,” she said. “The bottom layer has touched the ground. We can’t we can’t eat that. But before it touches the ground, it has so many opportunities to land on the top.”

With this comparison of the opportunities of life to the infinite possibilities of landing locations of a snowflake, Allen learned the importance of seizing the moment in front of her and valuing each and every opportunity life gives.

This idea shaped her mindset into what it is today, one that appreciates all the ups and downs of life, and has influenced how she approaches her current work at the school.

Not only has this memory influenced her mindset in regard to work, but it also has reinforced an idea that she felt she experienced — letting kids be kids. Growing up in a household and family full of moments like making ice cream from snow or biking 20 miles to surprise her uncle at a restaurant or having her dad pull her out of school to go watch the Detroit Tigers game are all moments that define this idea that she now holds so dearly and continues to practice when raising her own kids and mentoring Marksmen on campus.

is one of the most influential components of her life. A home away from home, her local church — St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Highland Park, a suburb of Detroit — was one of the places she spent the most time during her youth.

And in a perfect way of blending her love of music and this deep faith, Allen heavily involved herself in gospel music and the church choir. The second new gospel songs would come out, she would rush to go learn them with her fellow choristers, making lifelong friends in the process.

The church community she joined was not only a place of serious worship but served as a center of neighborhood pride and connectivity. During Halloween, the church would be decorated and made into a haunted house for the kids. Allen even spent the night in the church with a bunch of other kids in the neighborhood.

Her church was a lively center of community and a haven of close relationships across the neighborhood.

So that’s why when Allen began working for her Church’s summer school —Vacation Bible School — as a leader, she expected nothing other than the peaceful and joy-filled community she had enjoyed her entire life.

This reality was destroyed when someone fire-bombed the house of one summer-school students, which was close to the Church itself. The special, safe-haven feeling of her town came crashing down in one day.

“The girl who passed was one of my students,” Allen said. “In that one moment, I knew I wasn’t a kid anymore.”

Now an adult, Lorre Allen walked down a sidewalk on the way to dinner with her husband. Passing the street vendors on the corner, one specific object caught her eye — a leather elephant.

With elephants being one of Allen’s favorite animals, her husband noticed the elephant and Allen’s gaze and, without missing a beat, approached the vendor and purchased one of the little leather elephants.

Returning with her gift, Allen’s husband asked if she wanted him to take the new elephant to the car before heading to dinner. Allen had other plans. The elephant was coming with them to the meal.

However, it wasn’t long before two boys and a girl politely walked up to the cable and asked to hold and play with the elephant. Allen’s answer: absolutely. While holding the elephant in her arms, the little girl asked for the elephant’s name.

“I actually just got her and I don’t have a name for her yet,” Allen said. “Why don’t you name her for me?”

The girl named the elephant Ellie. Eventually, the kids, tired of playing with the little elephant, returned it to Allen and went back to their own table. After placing Ellie back in the middle of the table, Allen turned to her husband who had watched the entire interaction unfold.

“There is something about you and kids,” he said. “They gravitate to you and you gravitate to them. You meet them where they are.”

5

This moment was Allen’s snowflake, her opportunity. And like she had her entire life, she seized it. At that time, she was in the process of searching for a new job. Her previous work included Director of Human Resources at corporations like Boeing and university HR work.

But the next day, when she fired up her computer, she saw her next move: Director of Human Resources at St. Mark’s School of Texas.

The position had been posted online for a good bit beforehand, but Allen had never noticed it. This was because her focus had been on what she had excelled in her entire professional career: work in corporations and higher education.

But after the seemingly trivial interaction with Ellie the Elephant yet an incredibly pivotal moment in Allen’s life, Allen decided to go all in on the school. She interviewed in November. She was offered the position in January. She packed up in Seattle in February. Moved to Texas in March. Started her new job in April.

Allen has always told people to have a plan B. But according to her, she had no plan B this time. And when she finally stepped foot on campus, she knew she had found her new family-like community.

In one day, Allen’s childhood innocence was shattered.

To Allen, her deep faith in Christianity

Walking into the restaurant, Allen clutched the elephant in her arms as they approached the front desk before sitting down. Now seated at the table, the couple began talking while the elephant rested in the center of the table.

“I never thought that I would be working at an all-boys, grades one through 12 school,” Allen said. “I just had never envisioned it or even looked. But now here I am. I got the best job in the world. This was the best decision I’ve ever made in my entire career.”

3 29

4

30

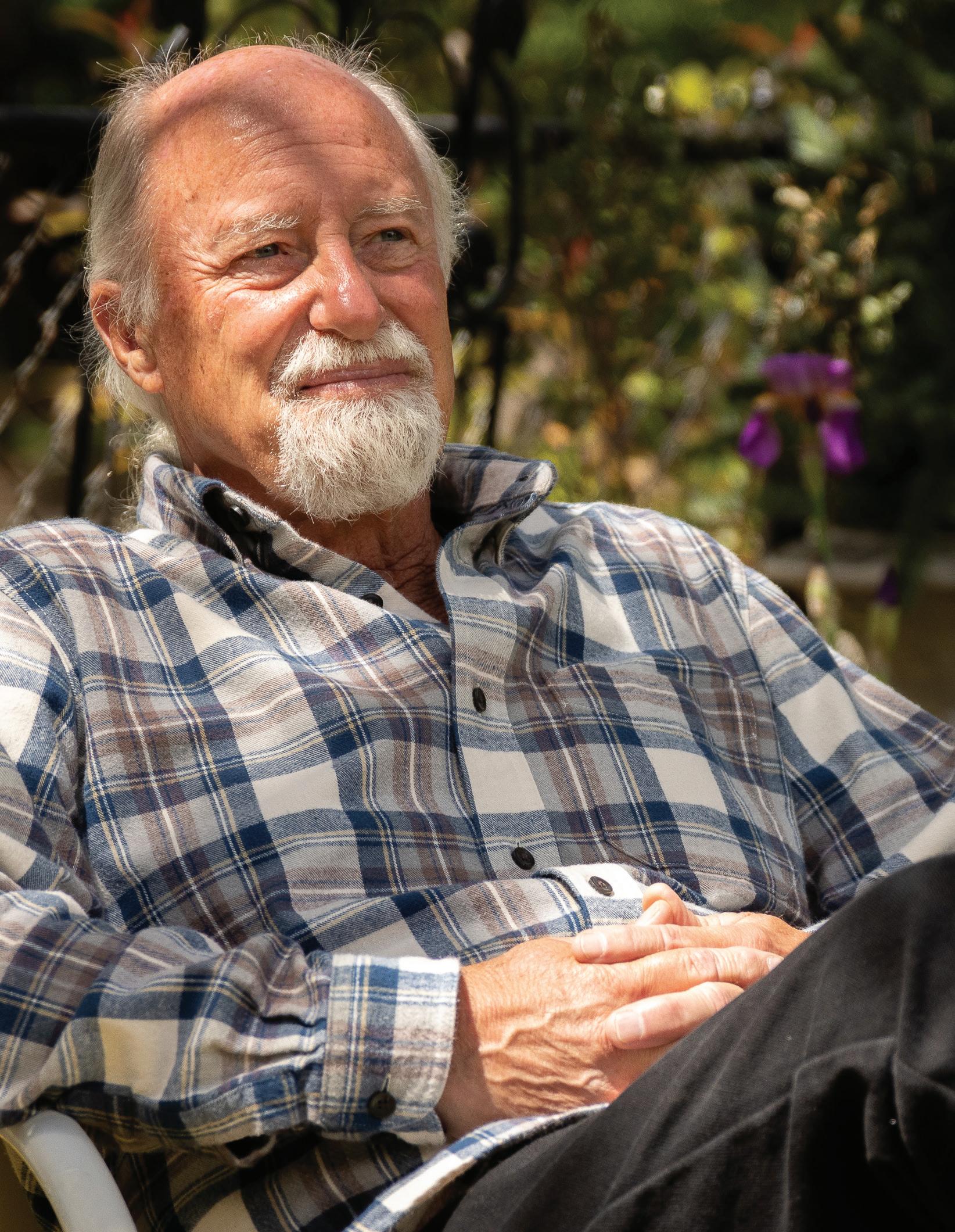

Dan Northcut ‘81 didn’t smile in a picture until college.

Sure, he forced a smile for picture day, but looking back at those old club photos, it was obvious that he was purposely keeping a straight face. He didn’t want anyone to see him looking happy.

He’d lost his father young. It was tough for that 8-yearold. But Northcut had to carry on. His mom was in rough shape for the year after that, and he had to make sure that she was going to carry on. He didn’t want to lose both of them.

Northcut never really got over losing

someone he loved. But he knows they wouldn’t have wanted him to be depressed all the time.

He just tries not to make it something that keeps him from having a full life — living in a way that, he hopes, would’ve made his father proud, making the progress that needs to be made without his father there to guide him.

Old friends would tell Northcut about his dad — always good things. How well his dad had treated people. How he could put anyone at ease. How his dad would talk to anybody, whoever it was and whatever class they were.

Northcut always wanted to be like that.

Hopping the back fence and cutting across his neighbor’s backyard, a seventh-grade Northcut made the 200-yard journey to the creek.

It was after dark, and he didn’t have a flashlight, either because he couldn’t find

one or was just stupid — he can’t really remember.

What he knew, though, was that his silkworms needed to eat. No matter what.

Muddling around the big mulberry tree, he picked up rocks and whatever else he could find and threw them at the tree. And snatching randomly at those bright green leaves that he couldn’t really see, he gathered whatever he could find in the dark.

To this day, he still can’t figure out how he managed to get those leaves.

But those silkworms depended on him. Rain or shine. There was no excuse.

It was his responsibility.

Responsibility.

That was Northcut’s turning point.

For years, he’d looked into the mirror and seen the same person. He didn’t feel any different. He didn’t really feel like a man. He just kept kind of…waiting.

The adventurer who learned how to smile.

Story by Linyang Lee

31

Photo by Noah Cathey

He’d started teaching when he was 22, and he’d already been leading Pecos trips during his college years — certainly doing the things he’d pictured a man doing. When will I feel like I’m a man?

But as he put his new firstborn child in that dang car seat, drove home from the hospital with his wife and son in the back and watched his son in the little carrier,

Northcut felt it.

“All of a sudden, in a way, your life is no longer yours,” Northcut said.

He’d had responsibility before — holding down a job and leading kids through the wilderness. But there was something different about having a kid.

Now he was responsible for another life — another person. And everything became making sure that the responsibility was met.

Looking around his classroom now, Northcut figures his childhood home couldn’t have been much bigger. Growing up blue collar in Oak Cliff, he’d always had to watch out for whoever was coming down the street when he was out — some folks might take your bike or whatever else you’ve got.

Not many people went down to the creek though. That was Northcut’s sanctuary.

Catching minnows and tadpoles, Northcut can’t count the number of mom’s strainers he’d ruined there.

“I always like to say I was born in a barn and raised at the creek,” Northcut said. If he wasn’t doing busy homework or the kids in the neighborhood weren’t playing ball in the streets, Northcut was at the creek exploring.

And ever since he’d gone fossil hunting with his dad, who’d been a geologist, Northcut knew he wanted to be a geologist too.

Being outside was always a part of his existence, and it naturally lent itself to earth sciences. What’s going on outside? How do all these systems fit together?

Northcut could have gone into petroleum geology — spending his life looking for oil. But it always seemed so much more tedious and unfulfilling than

32

Photos courtesy Dan Northcut

working with people. Watching people understand something. It meant a lot more to him than making five or six times his salary now.

The woman he was dating at the time didn’t feel the same way.

You’re just not going to be making enough money.

“I was like, is this a TV show?” Northcut said. “Are we in an episode? Do people really feel that way?”

But looking back, Northcut knows if he’d kept up with her, she would’ve just been constantly wanting more money.

A lot of people ask Northcut why he didn’t get a doctorate. For him, even his master’s degree was getting a bit too focused. He likes understanding how everything fits together. He likes seeing the big picture.

Like in his geologic timeline he does every year in the back alley — 4.6 billion years mod eled on 460 meters of asphalt.

Sticking out his thumb and measuring out about two centimeters, he points out that those two centimeters represent the entire existence of Homo Sapiens. And in just the last one 50th of one millimeter of our species’ existence — just about half the diameter of a human hair — Northcut points out that we’ve al ready messed up the world with climate change.

“Most people don’t understand that we’re just a flash in the pan, and we’re already screwing things up,” Northcut said.

Other than his wife’s coffee, of course, that’s the reason he wakes up in the morning. That’s the reason he’s been teaching the past 38 years. So that he might get all these messages about the real world — from just rocks and minerals to climate change — in front of people.

To

him, it’s his responsibility.

“If I don’t explain these things, then I feel like I haven’t done my part,” Northcut said. He would feel like he hadn’t done his part in this world to help the next generation. His part to help them make better decisions in their lives. His part to teach them how to live the world.

So that, maybe, just maybe, the world might change for the better.

33

Even after reading all these stories, you probably haven’t gotten any closer to finding your passion.

You’ve learned how others have done it, but it’s time for you to do it yourself.

Take out the shovel and start digging your own path forward. You might hit a rock sometimes. If so, take out the pickaxe and keep on digging. Like you’ve read, it probably won’t always be sunshine and rainbows. After all, digging a path is grueling work.

But if you stick to it, you won’t have to just read about how others have done it. You’ll have your own story to tell.

Because right now, you hold the shovel to dig the path. You hold the pen to that story. Write it.

Dawson Yao and Linyang Lee Editors-in-Chief

The former adventurer turned English teacher.

Story by Weston Chance

Photo by Winston Lin

The former adventurer turned English teacher.

Story by Weston Chance

Photo by Winston Lin

Story by Linyang Lee

Photos courtesy Scott Carlson

Story by Linyang Lee

Photos courtesy Scott Carlson