Where does it begin?

Where will it lead?

Where does it begin?

Where will it lead?

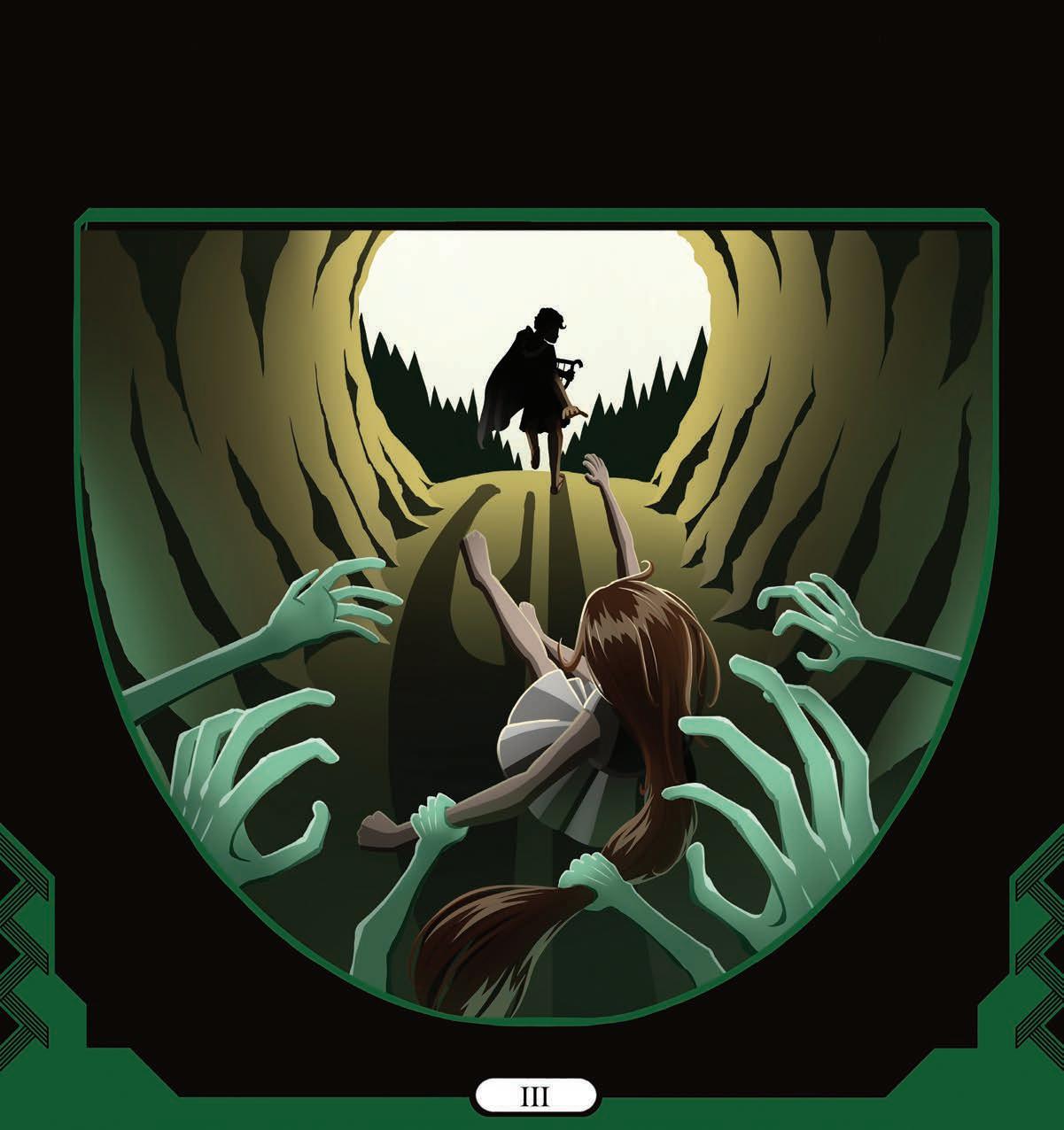

Lifeyields endless opportunities to know, to change, to create. Trailblazing advanced humanity to its golden age, building new tools from preexisting rocks and branches, turning ideas into reality. But the inevitable always looms over us: the things we “can’t do,” the things we’ll “never accomplish.” For Orpheus, this absolute is the death of his lover, Eurydice. e rule of the Greek gods is unmovable: whoever perishes must stay in the underworld, apart from their living family. But instead of accepting this tragic statute, Orpheus creates another option. To bring back Eurydice, he challenges the inevitable, the divine itself. Orpheus descends to the underworld in a mythic journey known as a “katabasis,” using the power and poignance of his music to persuade both his enemies and the gods. ough going to a place where mortals have never been before—pioneering the unknown—is riddled with challenges, his ironclad devotion gives him strength to persevere. Finally, when he reaches the depths of the underworld and confronts Hades, the god lording over it all, Orpheus manages to persuade him to change the rules. Orpheus plays an emotional piece on his lyre, bringing the god to tears. After he sees Orpheus’s conviction, Hades agrees to let Eurydice go back to the mortal realm with the condition that she walk behind Orpheus as they leave Hades. If Orpheus turns back to look at her, Hades stipulates, she will forever belong to the underworld. Orpheus eagerly agrees, sure that he can ful ll this condition. He and Eurydice stride ecstatically up toward the surface, but they encounter one last enemy blocking their happiness: doubt. Orpheus can’t bear the possibility that Eurydice might not be following him. is seed of doubt causes a lethal mistake—he turns around to make sure Eurydice

is there, and at that moment, she’s thrust back into the underworld. His insecurity and doubt cause him to fail in his quest, and his lover is now permanently lost to him. Orpheus goes on to live a life of sorrow, playing his lyre so powerfully that he can move landforms. In the end, a band of worshippers dismember him, ending his grief- lled life. e myth of Orpheus emphasizes the importance of decisiveness. Dedication leaves no room for doubt. Orpheus’s inhibitions ruin him; mortals’ indecisiveness and insecurities can severely restrict their lives. We should go all-out in our pursuits, stamping out our worries about whether there’s a precedent for what we’re trying to do, if it’ll turn out well, or how others will react. If we have a new idea, we have the freedom to realize it. Above all else, the myth highlights the possibility of changing the present. With enough dedication, anything can be improved, from ourselves to the universe around us. ey say that you can never complete a painting; one day, you just stop adding layers. Likewise, the world is an enormous canvas; there is no nal version.

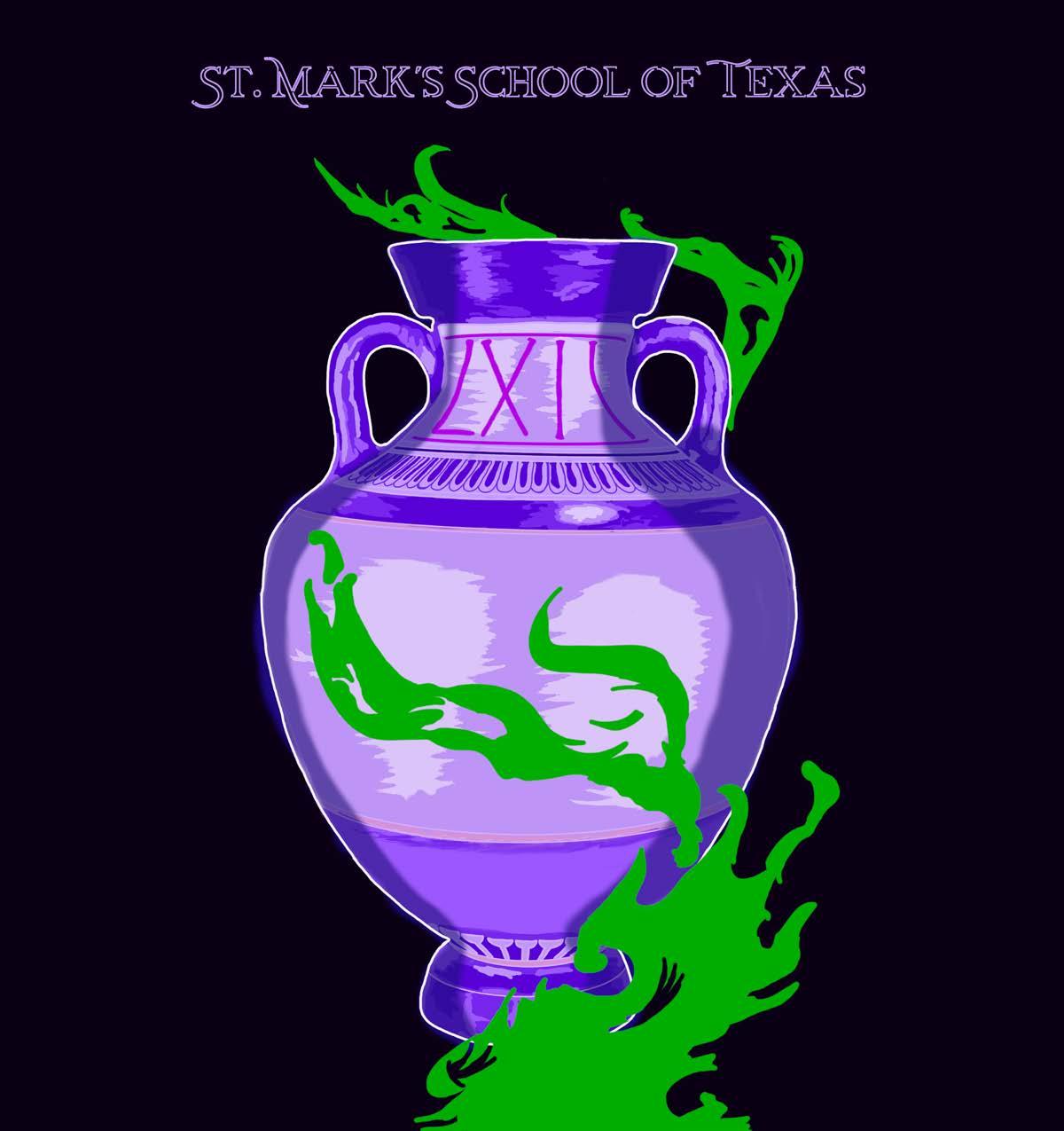

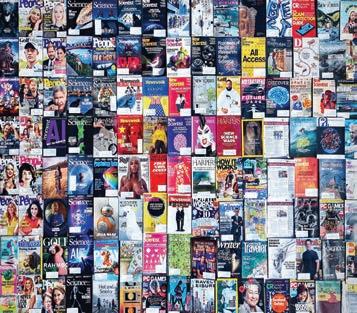

In the sixty-second volume of this magazine, we have united endless possibilities—writings, illustrations, photographs, and more—to create one new outcome: the 2024 Marque. Each intersecting node of a skillset, each point on the plane of imagination, converges into a new one, and those into more, doubled and then doubled again, producing myriad forms from just two. Each pixel, each character, brought from the imagination into existence, re ects our contributors’ constant e ort to spearhead new combinations, new ideas—ideas that, like Orpheus’s, will shape the world.

Welcome to Orphic, the 2024 Marque.

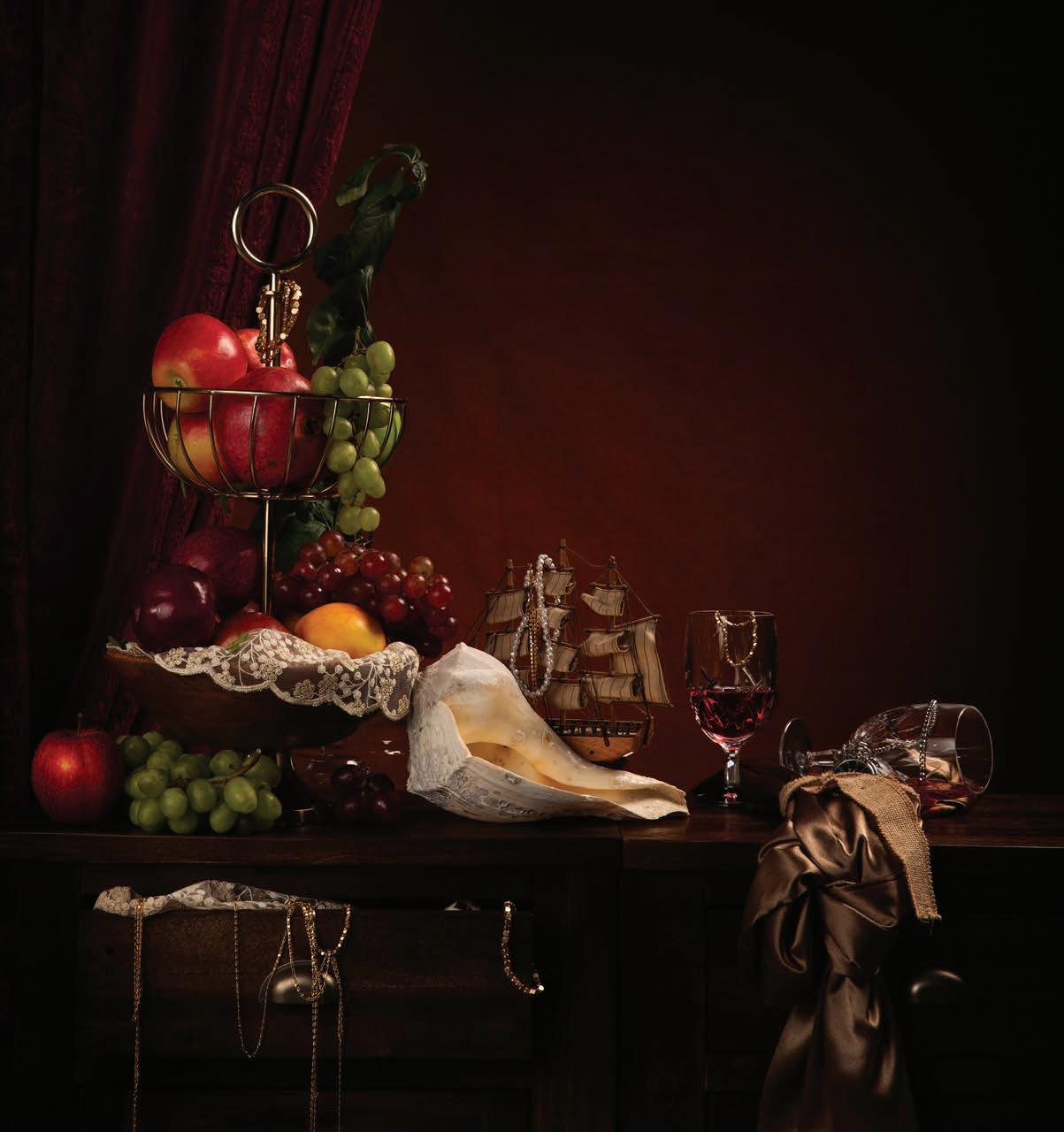

Wood & Metal Exhibition

P

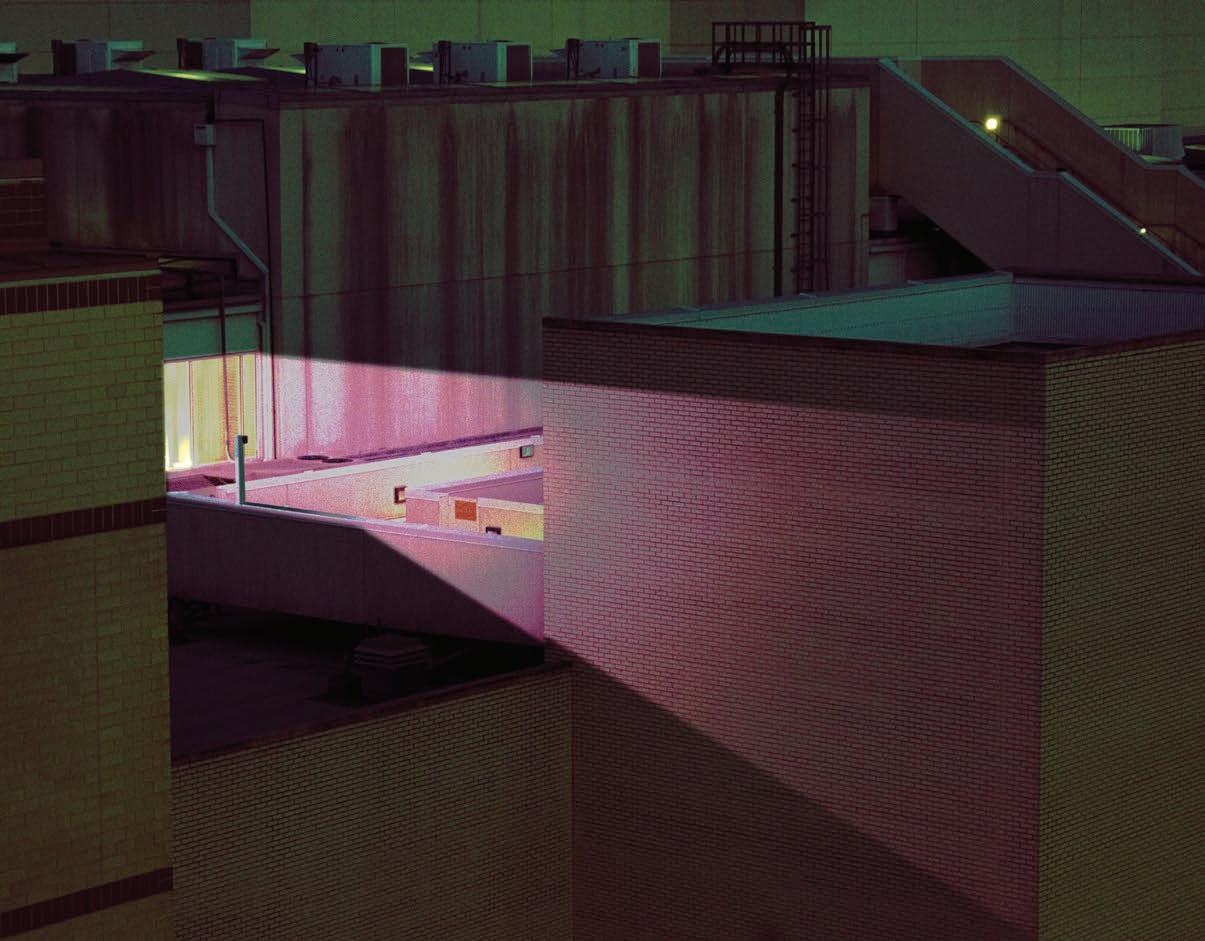

Photography Patrick Flanagan ’24

Fiction Nate Wilson ’24

Poetry

TCarson Bosita ’25

’25

Aditya Shivaswamy ’24 by Mason Bosco ’24 by Arnav Lahoti ’24 by Akul Mittal ’25 POEM by Grayson Redmond ’24 by Hudson Brown ’24 POEM by Ethan Bosita ’24 by Aidan Moran ’25 by Leo Hughes ’27 SHORT

by Charlie Hill ’24 by Akul Mittal ’24 by Drew Wallace ’26 ESSAY by Amogh Naganand ’24 by Drew Wallace ’26 by Reed Sussman ’24 by Nathan Meyer ’24 POEM by Grayson Redmond ’24 by Akul Mittal ’25

SHORT STORY by Justin Tong ’24 by Nathan Meyer ’24 by Nathan Meyer ’24

by Hudson Brown ’24

SHORT STORY by Miller Wendorf ’24 by Drew Wallace ’26 by Nathan Meyer ’24 by Hale Peterson ’25 by Preston Ghafar ’24 and Matthew Freeman ’25

POEM by Nathan Aldis ’26 by Akul Mittal ’25 by Akul Mittal ’25

POEM by Mitchell Galardi ’24 by Aidan Moran ’25

POEM by Tyler Tang ’24

POEM by Michael Chang ’27 by Hudson Brown ’24 by Reed Sussman ’24

SHORT STORY by Sanjay Bohil ’26 by Nathan Meyer ’24 by Hudson Brown ’24

POEM by Ethan Gao’24

POEM by Hayden Meyers ’24 by Nathan Meyer ’24 by Jacob Lobdell ’25

SHORT STORY by Ashrit Manduva ’24

SHORT STORY by Zack Goforth ’24 by Zachary Bashour ’24 by Arnav Lahoti ’24

POEM by Aryan Mishra ’26

by Akul Mittal ’25

POEM by Carson Bosita ’25

SHORT STORY by Nate Wilson ’24 by Patrick Flanagan ’24 by Tiger Yang ’25 by Tiger Yang ’25

POEM by Aditya Shivaswamy ’24 by Burns Houston ’27

POEM by Baker Lipscomb ’24 by Hudson Brown ’24 by Nathan Meyer ’24

POEM by Ethan Gao ’24

SHORT STORY by Lukas Palys ’25 by Zachary Bashour ’24

SHORT STORY by Arnov Lahoti ’24 by Asher Ridzinski ’27 by Arnav Lahoti ’24 by Peter Clark ’27 by Jacob Lobdell ’25 by Nathan Meyer ’24 by Jacob Lobdell ’25

POEM by Mason Briscoe ’24 by Drew Wallace ’26

POEM by Raja Mehendale ’24 by Tiger Yang ’25

Mr. Brown’s contributions to the school community through the Litfest, Creative Writing, and his leadership as the Victor F. White Master Teaching Chair in English are all massively impressive. But, perhaps his most valuable e ect is on the students he teaches and develops every day.

Mr. David Brown. Our impartial, impassioned English teacher. Striking down errors with the power and precision of Zeus’s lightning bolts, he ingrains upright grammar with a godly aura. But aside from his authority over the ten Rules for Avoiding Common Mistakes, Mr. Brown always o ers an open ear to our ideas. Regardless of whether he agrees with them, he listens to and o ers valuable help for our writings. In addition to being an amazing English teacher, Mr. Brown is also a baseball bu and Broadway connoisseur.

With his unique, creative assignments ranging from villainous sonnets to pensive re ections, Mr. Brown creates myriad opportunities for us to learn new techniques. In his creative writing class, he even assigns us to write and perform songs of our own! And on top of organizing these activities, he even plans St. Mark’s Lit Fest each year. Like Atlas holding up the Earth, Mr. Brown is an integral character to many of our stories.

But Mr. Brown is hardly an unreliable narrator. Holding the Bedford like a glinting Bible, a light in the dark of folly, he’s fully mastered the art of English. And for the avoidance of doubt, he’s compiled a list of ten of the most useful, yet neglected rules: his iconic RACM. With this almost magical sheet in our hands, we raise our writing to the next level. Explaining subjects ranging from e Great Gatsby to “Howl” with infectious enthusiasm, Mr. Brown is always a glowing light of exuberance in our lives.

When we play our lyres, pour ourselves into our writing, Mr. Brown is always there to listen and help us grow. Like Hades, who was originally against the resurrection of mortals, but eventually gives Orpheus a chance and accepts his music, Mr. Brown treats every idea as equal. He’s the pillar of justice, the balanced scales, in the otherwise subjective English language.

Orpheus was unexpectedly thrown into a quest of recovery when his wife, Eurydice, was bitten by a viper and killed by its poison. He began his journey in sadness, desperation, and longing.

Like Orpheus, there are times in our lives when we are unprepared for what lies ahead, despite being called into action anyway.

But it’s up to us to react in a mature, appropriate, and responsible way. When we’re given a righteous path, we need to take it with full conviction.

And despite our feelings of despair or fear of failure, we must push on, following our destiny.

As Orpheus approached the gates of the underworld, he was a man determined.

By Dawson Yao ’24

Towardsthe end of my junior year, I caught wind of a story from one of the sophomores working under me in the journalism program. e story was about the sudden death of one of our school’s most beloved sta members: former cafeteria worker Steve “Hollywood” Walker, a man I had never met. ere was no way for me to walk through his lunch line, excitedly high- ving him on the way to my meal. ere was no way for me to see rst-hand his unparalleled dedication to the school that was his home. ere was no way for me to be in his presence. Yet, through people who knew him, I was determined to try to do so anyway.

To say that what followed was an emotional rollercoaster would be an understatement. ough I acted merely as a reporter in a scene of remembrance, I nevertheless felt as though I myself was mourning. My rst interviewee for the story was Mr. Ron Turner, Sr., a hard-nosed former football coach whose rough exterior has withstood the test of time. Rarely smiling, his facial structure rested in what I perceived to be a “mean-mug” expression. As the interview date drew near, I grew increasingly nervous at the task ahead. I was afraid that he would question my right to write about his dear friend, a man I had never even known in the rst place. What if he pushes back? What if he refuses? What if he doesn’t speak to me?

As I posed my rst question, the same thoughts from a week of anticipation ashed through my mind

in a whirlwind. When the last word left my mouth, I sat nervously in my seat. A long pause, and I began to crumble. But as his words owed in response to my questions, I caught a glimpse of the true Ron Turner. With every word he spoke, fresh cracks lined his rough, armored exterior. Inside a battle-tested shell of grit was a man: a man who was simply broken by the death of Hollywood: a coworker, a mentor, and ultimately, a friend.

As the interview progressed, my con dence grew. My questions probed deeper and deeper as I dug at the aspects of their relationship that made it special. e interview turned into a conversation. His posture also relaxed, and before I knew it, he was opening up about stories that he might not have told to anyone anywhere else. All the jokes they’d told, all the challenges they’d faced, and all the memories they’d shared came pouring out in what was a massive exhale for Turner. I learned of the great man Hollywood was from his day-to-day interactions with teachers and students to his unwavering dedication to the job he did best. A gentle six-foot-two man who barely knew how to sign his name, Hollywood took it upon himself to work, walking half a mile to school each day with a bad leg, taking care of his family, and even learning as an adult to read and write – essentially from scratch. Even when the pandemic struck, his chopwood-carry-water attitude never wavered but grew ever stronger.

en, precisely an hour into the interview, I asked,

“What was it like, on the day he died?”

Once again, a pause set in. My nervousness came back, and I was left hoping and praying that he would answer my question. But before the panic crept in, his shell broke completely. His voice cracked, and he broke down. Finally, tears streamed down his cheeks. It seemed that years of pent-up emotion nally broke down the oodgates. rough watery eyes and carefully chosen words, I learned of the day it happened, exactly as the events played out. But as I listened, one thought ran through my mind: What am I supposed to do when someone so resilient cries in front of me?

I’ve faced situations like this before. In the past, it’s always been the same: “What do I say?” or “Why does it always have to be so awkward?” Every time, from watching

friends mourn loved ones to watching family members break down at gravestones, I’ve sat idly by, unsure of what words to say or how to show empathy. But this time was di erent. is time, as I watched the man cry, I realized that repeating questions or o ering my condolences wasn’t going to help. So, instead of inputting my thoughts, I let the man speak. I spoke no words, yet the conversation owed freely. All I did was sit quietly and try to listen to the many memories of Hollywood he held so dearly in his heart.

When conversations become tear- lled, witnesses often have di culty nding the right response. But, sometimes, the best response is silence. Sometimes, all mourners want is for someone to take in the moment with them and just listen to what they have to share.

“The

By Aditya Shivaswamy ’24

Clive had not actually seen the remains of the village, but he found it unimportant to truly report the “facts” of the occasion to the Lieutenant-Governor. e administrator whom he had sent to actually check on the fatalities had fallen deathly ill upon the visit to Saugor, sending only a brief letter to Clive detailing his “utter disgust and unwillingness given the proposition of sifting through the piles of bony rib cages and legs fed upon by the vultures.” Clive knew that the young administrator had never been cut out to do his job, as that administrator, soon to be shipped back to the mother country, had the blood of the lazy Irish owing through his veins, courtesy of the man’s miscegenating mother. us, Clive gave a solid estimate of three hundred or so dead ragheads in his report to Sir Wellesley, as well as a recommendation of dismissal for Administrator O’Brien. Clive knew that Lieutenant-Governor Wellesley did not necessarily care either, as both were well-educated Oxford men, learned in the ideals of Malthus and his “Essay on the Principle of Population” -- it was only nature that the famine was to hit the overpopulated and primitive villages of the North-Western Provinces. As Sir Wellesley, a far more Christian man than Clive, liked to say: “If God wills it, who shall disturb it?” Clive signed the letter, tucked it into the ivory white envelope, and, grasping the wax stamp, sealed it. Looking up from his wooden desk, he rang for a servant. An old, plump brown man, a turban on his head, rushed in and bowed. He meekly took the envelope and

was preparing to make his way out when Clive stopped him. Clive, barking, ordered: “Ask the cook to prepare the barasingha I brought in yesterday.” With no indication of demurring, the servant scurried out of the door and into the servant’s quarters. Clive sighed and reclined in his chair.

Clive signed the le er, tucked it into the ivory white envelope, and, grasping the wax stamp, sealed the envelope.

As the wooden chair creaked under the strain of the administrator’s weight, the tightly woven jute padding that served as its backrest snapped, dumping Clive backward onto the dusty ground. He lifted himself o the ground, peeling o a little of his hand’s epidermis on a rusty nail lazily hammered into the wooden oorboards. Grasping the mangled chair in both his hands, his blood dripping down and soaking into the jute, grunting in pure rage, Clive threw it across the room. As the shoddily made furniture crashed into the corner, Clive bellowed, to no one in particular, for both a bandage and a person to clean up the mess. Moments later, a few servants jostled into the doorframe to gain favor from their sahib. After throwing the thronging group out of the room, Clive bandaged the nick on his hand, then sighed and rested on the couch near the desk, stomach grumbling. He quickly fell asleep.

When the bloodhounds had exhausted themselves, the shikari beckoned Clive and his hunting retinue, the most physically t of the servants, to follow him. e evening under the canopies of the forest was restless. e dry ground was cracked, delirious beetles and ants crawling out of the parched earth, seeking wildly for

some moisture. e normally inviting sounds of rhesus macaque hoots and bird calls were absent -- in their place, an odd, syncopated rhythm of col legno buzzing insects compounded with dry, rustling leaves from the hot wind and the incessant, primordial hum of the forest. Clive tilted his head and drank from the ask of water, sloshing it about in his mouth and then spitting it out onto the ground. e heavy, parched air seemed to suck every bit of moisture out of his mouth. e dirt greedily reclaimed it -- a worm, seemingly waking out of some dehydrationinduced stupor, broached the surface, hoping for an indication of precipitation or moisture, then retreated into its subterranean home. Clive cleared his throat and moved on, stepping on a massive beetle on the forest oor. e men behind him sidestepped the insect, dark, maroonblack blood oozing out of the crevasses of its cracked exoskeleton, its knobby legs isolated from the rest of its body, buried in the granular soil. As soon as the blood reached the dirt, matting it into a wet, muddy muck, smaller beetles, antennae moving about, broadcasting pheromones into the aether, hobbled towards the body, a chalice of bubbling wine, clambering over each other to get a taste. Using a fallen tree, Clive angrily scraped o the eviscerated guts that had splattered over the bottom of his black hunting boots, muttering some obscenities directed toward the dratted animals that infested both the forest and, increasingly, the dak bungalow in which he had been living ever since his transition from a commander of the Bengal Army to bureaucrat. He wasn’t unfamiliar with this land of, as he saw it, wild animals and animalistic men. He had been stationed here, in the Upper Doab, during the Mutiny,

essentially administrating the land while the soft desk-job men had ed back to England. He thought the work suited him.

He wasn’t unfamiliar with this land of, as he saw it, wild animals and animalistic men.

Soon the party, led by their dogs, reached a clearing that showed a small, rain-blackened, ancient temple on top of a weed-strewn, grass-covered knoll. e stone structure featured statues of various syncretic gods -- a large relief sculpture of some tribal god with a deer’s head stepping on and crushing a homunculus-like dwarf was anked by multiple indentations of a carved bodhisattva. Clive felt uneasy. Something felt familiar about this place. As he scanned the surrounding landscape -- the temple’s crumbling carvings, the drying grass, the inexplicably full temple tank of brown, muddy water covered in bright pink lotuses and their deep green lily pads, the skeletal trees in the thicket -- from a cavernous niche of his memory, Clive tried to retrieve an image that resembled what he was seeing with his own eyes, spelunking deeper and deeper until everything he thought of was dark and barely outlined at all. ere was something missing.

Just as Clive was musing on his remembrances of things past, a bloodhound went berserk, freeing itself from the leash of the shikari by ripping o the collar on its neck along with a sizable amount of esh from its own nape. It bounded towards the temple tank, its movements erratic and frenzied. Clive, unfazed, followed, gun leveled to shoot the apparently rabid mongrel. (Truthfully, Clive was a bit disappointed, as this dog was a pure-breed English bloodhound, and he hated to get rid of the thing). But the zigzagging of the dog didn’t make for good shooting on Clive’s part. Cursing, he followed.

Clive watched in disbelief as the dog struggled against the water, its desperate cries echoing through the clearing.

e crazed dog leaped into the temple’s stagnant pool, disturbing the serene surface of owers and murky water as it thrashed about. e water churned violently, owers and lily pads scattered in all directions, leaving a trail of chaos in their wake. Clive watched in disbelief as the dog struggled against the water, its desperate cries echoing through the clearing, not because of the yelps of the dying dog but because of what lay right beside it. A massive golden barasingha drank from the tank, lapping up the water, which was muddy, an earthy, almost brownish-red, as though the iron content of the soil had seeped into the water. As he leveled his gun to shoot, he noticed the ripples from the deer drinking from the tank bouncing o something in the center of the body of water. en he noticed the tendrils and roots of the aqueous owers, which stretched out radially from a central nexus. He followed those until he saw the organism.

Floating amidst the disturbed waters was the limp form of what seemed to be a young boy, his lifeless body adorned with owers, a sole crimson lotus protruding from his mouth. Its roots owed through his bloated, almost milkily transparent body like nerves, erupting from his head into the stalk of the crimson lotus. Clive pulled the trigger in re ex shock.

e majestic barasingha bellowed in panic and pain, its antlers catching the sunlight as it attempted to ee, blood freely owing from its rear. e wounded deer limped and dragged its body under a nearby copse of trees, where it expired in what seemed to be a eld of white minerals like apatite. Clive recognized the tree. He recognized the nooses hung from the branches like sinister ornaments, the branches from which strange fruit had been plucked. He had been here only four years

before. Clive smiled grimly as he looked more closely at the minerals beneath the tree. Dried bones lay underneath the ropes. He chuckled. He red one more shot into the moaning deer, then traipsed over to the trees to retrieve tomorrow’s lunch, whistling to his retinue, which hung back behind him. ey didn’t move. eir faces were set in unmovable catatonia. ey didn’t want to go near the killing elds where the bodies of their cousins and sisters and uncles lay, their bodies torn apart and deposited such that they would su er eternally, never receiving funeral rites to put them at rest. ey remembered Clive, a commander in the Bengal Army, torturing and killing those who had mutinied, killing their sons, killing their families, leaving the women for his men. Clive whistled again, shooting his ri e into the sky. e shikari slapped a few of Clive’s men in the face, ordering them to follow him and bag the result of the day’s hunt.

e party left, but Clive stood in the temple clearing, confused. He did not remember there having been a temple here. He remembered marching those who had found refuge in the forest (o cially still rebelling against the Company) to this clearing. But the temple hadn’t been there, had it? Clive shrugged, making his way back to the group that wound its way back to the bungalow.

Clive woke up. He didn’t understand why he was reliving yesterday’s odd happenings in his dreams. He wasn’t particularly scared; they were just replaying in his mind, again and again. e servants called out to him, reminding him of the meal awaiting him. He went into the dining room, where he was served a wonderful venison and a ne wine from Bordeaux. He feasted.

Once done with his meal, Clive told his servants to tell the driver that he was going to depart for Saugor. e

The walls were adorned with gruesome depictions of torture and su ering, each image more horrifying than the last.

damned fool administrator had not nished his job, so he needed to at least check up on the place himself.

Upon reaching Saugor, Clive was greeted by the rancid smell of rotting esh. e famine had clutched Saugor by the neck and throttled it. Vultures circled overhead, their sharp cries piercing the air as they feasted on the remains of the dead. One carrion-eater stood over the small body of a child that seemed to be naught but a ribcage, two sticks for legs, and a face on which the vulture was busy feasting, plucking out his eyeballs to get at the aqueous humor. e birds of prey are thirsty too, Clive thought. He walked amongst the devastation until his heart nearly stopped in shock.

Standing in the town square was the temple. ere was no mistaking it; it was the same rain-blackened, stone temple that he had seen in the clearing near the killing eld. Not the same architecture, not similar designs. e same one. e deer-headed god crushed the homunculus. Clive clambered up the temple steps in his boots and kicked open the sanctum sanctorum.

Entering the shrine, Clive was met with horror. e walls were adorned with gruesome depictions of torture and su ering, each image more horrifying than the last. Red men with cannons and muskets and knives, and it was him on these walls -- he knew it -- he needed to get out, he needed to leave -- it had nally come to him. In the place of the idol was a deer-headed god, its eyes blazing, neck strung with faces that kept changing. Brown men and women and children that he recognized somehow were projected in some slideshow of torture. eir faces were like Greek masks of tragedy, bent in awful

proportions in pain and su ering. Clive rushed from the sanctum sanctorum, this nightmare realm that seemed to have ensnared him. But as he turned to run, Clive found himself in a dark, dank compound seemingly underneath the ground, unable to break free from the su ocating grip of his own fear. He struggled against unseen forces, his pleas for release falling on deaf ears.

He rushed into a small, enclosed room. He looked around, but saw nothing but dark walls around him; he looked up at the ceiling, and he could swear that he could see through it. It was through the hard wood oor of his bungalow. He had somehow come back home. He rejoiced, trying to climb out of the pit he was in. But then he saw himself. He saw Clive pacing back and forth above him in the bungalow. Clive screamed, begging himself above him to set him free, to release him from this nightmarish prison. Clive paid no notice. Clive ung a chair against the wall. Clive heard the splinters from above. Clive wailed. Clive bled. Clive saw his blood dripping down into the oorboards onto him. Clive felt his own blood dripping onto his face.

Clive was thirsty, his throat parched, su ocating in the pit. He welcomed the cool blood into his mouth.

But the tendrils plunged into his body, rooting him to the ground. Clive felt every bit of it.

He felt the roots envelop his spinal cord, making him unable to move. He felt the stalk of the ower climb up the esophagus. He felt the lotus bloom. He saw the deer around him eating the vegetation around him. He saw himself getting called from above to feast on his barasingha. He felt it all, until he could no longer feel.

By Christian Neisler ’24

In the shimmering dust, a band Of infrared light was the only clue from afar of the fuse Between the yellow and orange dwarf stars. e stellar tree Connecting the Alpha Centauri star system sort Of collapsed as Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman became one. Reverberating through the interstellar medium, the shockwave made a run

Past solemn echoes of a star’s death, a run Into the icy Oort cloud lled with planetesimals which banded Together under the in uence of gravity, passing not one Neighboring star without dumping ionized gases that would fuse And release coronal mass ejections, the sort Of bursts of magnetic eld that disrupt entire trees

Of life. Sol’s geomagnetic storm assaulted Earth’s biosphere, no tree Left untouched by the deluge of radiation which decided to run Rampant among carbon-based life. An attempt to sort rough the surviving satellite data revealed a band Of intensely a ected trees in the Amazon which could fuse Together into a constantly growing superorganism, one

Massive, thirsty, tangled knot of roots that one Might confuse for an underground ball of hardened spaghetti. Tree After tree joined together, igniting the fuse Of a hyper accelerated evolutionary process run By a mutated allele. eir faulty DNA lacked the bicolored band at keeps plants from uniting roots with trees of other sorts.

e conglomeration of organic matter consumed every sort Of particle from the air, scrubbing the air clean one Pollutant at a time. Slowly, the atmospheric band Of smog began to clear as the mutant tree Species replaced impurities with diatomic oxygen; continuing to run, is highly e cient puri cation process fused

Undesirable compounds and buried them underground, lighting the fuse

For a climate solution. e problem scientists had tried to sort Out for years had been trivialized by a stellar explosion run Rampant. By some adventitious circumstance, one Distant supernova had created an alien on Earth: a tree Symbiotic with all plant species. Forming a band

Of foliage that could fuse together, the anomaly eliminated the band Of contaminants caused by industry run awry. e one World capable of sustaining any sort of life was saved: saved by a tree.

“Dale”

By Ethan Bosita ’24

Randall’s crumpled form lay sobbing on the ground, his muscles and ironclad Physical fortitude blindsided by the Xenoform’s mental assaults. Like a sneak In ltrating a citadel through an unguarded sewer, its brainwaves subverted Randall’s logic, Tearing apart his patterns of thought and destroying his perception of reality. Besieged By an incomprehensibly ancient force, the man retreated from reality, ying Away into his own headspace, supposedly protected from the meddling of cosmic

Beings. e Xenoform looked upon the prone man, the prey it had subdued. Life-giving cosmic Evolution seemed to have failed this creature. It had in its possession no ironclad Carapace to protect itself with, no ability to cast projectiles and down ying Prey, and no innate abilities to ambush, exhaust, pursue, or sneak. And yet this horror survived the gauntlet of life. Its ancestors assailed and besieged By all manner of natural predators, somehow the bloodline survived. Logic

Dictates that these defenseless creatures should have passed into extinction. Poetically, abusing logic Proved their saving grace. In all the universe’s myriad corners, beings operate upon cosmic Constants, aspects of reality that are constant, sacrosanct, and inviolable. And yet minds are besieged In perpetuity by logical inconsistencies, surviving solely through ignorance and ironclad Fortresses of obstinacy. rough evolution’s ukes, Xenoforms gained abilities to remotely sneak Into brains and lower their defenses, essentially short-circuiting sanity. “Natural” adaptations like ying seem weak and useless compared to this natural superweapon; “Good luck ying away when your very brain bows to my command,” the Xenoform seems to taunt. Human logic has no home in the aliens’ realm of madness. Insanity must counter insanity. Xenoforms sneak into humans through logical gaps; without logic, they lose access to the mind. Exposed to cosmic rays at a young age, Tim had never been a stable person. Sealed into an ironclad straitjacket and dumped into a deep space mental asylum, the man had developed a besieged

mentality, believing literally everything was after him. Most avoided the besieged man, fearful of his instability and proclivity to go ying into a psychotic episode at the slightest provocation. And yet, as the ironclad asylum found itself under attack by a creature that preyed upon logic, the survivors found that the only man with a chance to destroy this cosmic horror was Tim. Approaching Tim’s cell, these desperate few sneak

past the resting Xenoform; entrusting one among themselves to free Tim, the chosen sneak in ltrates the cell and frees the insane man from his shackles. Quickly besieged by Xenoforms alerted by Tim’s shouts and screams, Tim felt their cosmic waves washing over his mind, but he had no reaction. Roaring and ying at them with his bare hands, Tim tore into the swarm of aliens. eir overemphasis on logic and subverting minds left them vulnerable to a threat with no logic, no mind to subvert. An ironclad

defense against their evolutionary path, one of a few things that sneak Underneath their otherwise invincible cosmic assaults.

e Xenoforms all perished to Tim’s assault, their physical forms falling as dictated by logic.

“Mr. LaBrodeur” | Leo Hughes ’27

By Charlie Hill ’24

RustyKraken was not in a good mood. It was Monday again. After a weekend of neglecting his responsibilities, he had to go back to work. After a year of working the same job, Rusty was tired of it. He was still young, having just turned twenty-three, and he wanted a fresh start somewhere new. Unfortunately, his dreams would have to wait until tomorrow as his boss was expecting him. After throwing on a worn-down gray hoodie, Rusty grabbed his backpack from the oor and exited his small apartment in upper Manhattan. He trudged down the steps of his decrepit building and walked to the subway station a block away. As he waited for the train to arrive, he looked around at his fellow commuters. Men and women with zombie-like expressions attempted to prepare themselves for another week of work.

Finally, the train arrived, and Rusty was able to grab a seat for his ride to work. As much as he wanted to put his headphones in and take a quick nap, he didn’t trust the other passengers to ensure the safety of his belongings. When the conductor announced that Rusty’s stop in the Upper East Side was approaching, he got up from his seat and edged closer to the door. He was running late. e doors nally opened, and Rusty hustled up the stairs and out onto the street. He ran the last block to the o ce and burst through his door right as the clock struck nine o’clock. He was supposed to be there at eight. Rusty was

struck by an unpleasant scent: e strong odor of cigar smoke permeated the o ce. His boss, Mr. Michaels, was seated in a large leather chair, reading that day’s newspaper. He looked up from his oversized desk.

“You’re late again.”

“I know I’m sorry, I overslept my alarm. It won’t happen again, “ Rusty said.

“I don’t care about your excuses, Rusty. I’m tired of the tardiness. Here is your shopping list for the day. Get it done.” Mr. Michaels glared at Rusty and pointed at the door before reopening the newspaper he had been reading.

Rusty, ustered, picked up the list on the desk and walked out. He glanced down at it, and his eyes widened. He would need to go to Lower Manhattan to get everything from the list. He exited the building and walked back towards the subway. Rusty hoped he could get through at least half of the list by noon so he could get a nice lunch. By the time Rusty arrived in Lower Manhattan, it was a quarter until ten. He got started right away. Before he even got o the train, he began to scan the crowd. After a moment of searching, he noticed a man, no older than thirty, in a custom suit. He had a leather briefcase with gold latches and a Rolex poking out from the cu of his shirt. Fortunately for Rusty, the man appeared to be preoccupied with the music playing from his headphones.

The look of rage and the surprising strength in the man’s grip convinced Rusty to cut his losses.

Rusty attempted to approach the man from behind until he was only a step behind him. As the man exited the station, Rusty brushed up against him, mumbled an apology, and kept walking, though much faster than before. A moment later, Rusty felt a hand on his shoulder. He immediately broke into a sprint, but the hand was able to grab hold of his backpack and yank him back.

“Where the hell is my watch?” said the man. e look of rage and the surprising strength in the man’s grip convinced Rusty to cut his losses. He reached into his pocket and tossed a Rolex watch at the man’s face before sprinting o into the crowd of people on the street.

Rusty did not have much more success with unsuspecting commuters that morning. He had spent the entire time patrolling the streets of the nancial district, and his only successful theft had been the wallet of an old man who was too slow to chase him down. It contained a credit card, a ten-dollar bill, and a bus ticket to Florida. Not a great haul. Rusty pocketed the ticket and the cash, but the credit card would have to go to Mr. Michaels. All the other rich businessmen around were too protective of their belongings or Rusty just lacked the skill to steal from them.

Soon it was time for lunch, and the ten-dollar bill from the old man’s wallet wouldn’t cover anything more than a sandwich and coke. Mr. Michaels’ shopping list included three Rolex watches and ten credit cards by ve o’clock that day. Rusty had a lot of work to do in the afternoon.

Despite his best e orts, Rusty didn’t fare much better. He got one credit card from a woman who was screaming on a phone, but other than that, he struck out

completely. Rusty got back on the metro and headed back to Mr. Michaels’ o ce. When he arrived at the o ce, Mr. Michaels’ was still sitting behind the same desk with the same look of annoyance on his face.

“What’s the haul?” he said.

“Well, I didn’t quite get everything that you asked for, but I still got some good stu ,” said Rusty. He gingerly placed the two wallets he had stolen on the desk.

“Are you joking?” Mr. Michaels grumbled. “I gave you a very simple list. If this is all you are going to bring back, we are going to have some problems.” Rusty attempted to mumble an apology, but Mr. Michaels cut him o . “I have a job for you. Tonight. is is your last chance. You better not fail me again. All the information is right here. I will meet you at eight tomorrow morning.” He slammed a folder on the desk and gestured at Rusty to pick it up. Rusty grabbed it and left without waiting for a dismissal.

Rusty opened the folder once he arrived at his apartment. e target didn’t seem too di cult at rst as he was supposed to break into a nearby convenience store. Upon closer inspection, Rusty realized the target was not the cash register but rather a safe. e safe was in the back room; he was supposed to break into the store and crack it. e only problem was that Rusty didn’t know how to pick a lock. Rusty also didn’t know how to crack a safe. He wasn’t very good at his job. After trying to think of a solution, Rusty went to the hardware store and bought a blowtorch and a crowbar. Hopefully, that would do the trick.

At midnight, Rusty gathered his things and headed towards the convenience store. When he arrived, most of the lights were o inside, and the “closed” sign had

been put up. Not only that, but the bars on the doors and windows would make his crowbar useless for breaking inside. Frustrated, Rusty sat down on the front step and leaned back against the door. His head banged against the oor. e door was unlocked, and it had swung right open. Rusty, confused, stood up and walked inside.

After surveying the store, it appeared that he may not have been the only visitor that night. A display of sunglasses had been knocked over, and the doors to the coolers were wide open. Flustered, Rusty decided to continue with the break-in. He walked towards a door in the back that looked like it might be the back o ce. He looked inside and found a small desk, a lamp, and some metal cabinets. On top of those cabinets sat a rusty safe. Upon closer inspection, Rusty realized that the door to the safe had been cracked open. Rusty couldn’t believe his luck. He lifted the safe o the cabinet and placed it on the desk. Inside, he found several thick rolls of cash. It looked like several thousand dollars. Rusty quickly stu ed the money inside his backpack. He put the safe back on the counter and walked out of the store. Worried about the wads of cash in his backpack, Rusty hustled back to his apartment and locked the door behind him. He decided he should get some sleep before meeting Mr. Michaels in the morning.

“You’re late,” Mr. Michaels said. “All of it had better be there.” Rusty placed the backpack on the table and opened it. He pulled the cash out and handed it to Mr. Michaels.

“Is this all of it?” Mr. Michaels asked.

“Yup, way more than I expected. Really easy job, too,” Rusty said.

“Do you think this is funny? Where is the rest of it? Where is my damned money?”

“ at was everything that was in the safe, I swear.” Rusty exclaimed. “I think someone might have taken some of it before I got there, but-”

Mr. Michaels didn’t wait for him to nish. He pressed a button on the phone resting on his desk. “Roger, bring me my briefcase, please,” Mr. Michaels growled. Rusty knew that wasn’t a good sign. He had to do something.

Rusty dug around in his pockets, but he had forgo en his wallet in the rush to leave that morning.

When Roger opened the door, Rusty made a run for it. He slid around Roger and ew out the front door. He kept sprinting once he made it to the street. He heard a loud pop behind him. And then another. Rusty didn’t dare look back, but kept running for what felt like hours until he approached a bus stop. He jumped onboard just as the doors were closing.

“Ticket, please,” the driver said.

At the sound of a car honking outside, Rusty woke up and rolled over to look at his alarm clock. It was fteen minutes until eight. Rusty threw on the same clothes from yesterday and sprinted to the subway station, hoping that by some miracle he could make it by eight.

When Rusty arrived, he burst through the door of the o ce and exclaimed, “I have your money!”

Rusty dug around in his pockets, but he had forgotten his wallet in the rush to leave that morning. He felt a piece of paper and pulled out a white slip. It was the bus ticket to Florida he had stolen from the old man yesterday. As the doors closed behind him, Rusty breathed a sigh of relief. He handed the ticket to the driver, who took a short look before handing it back to him. Rusty took a seat in the back of the bus and settled in for a long ride.

By Amogh Naganand ’24

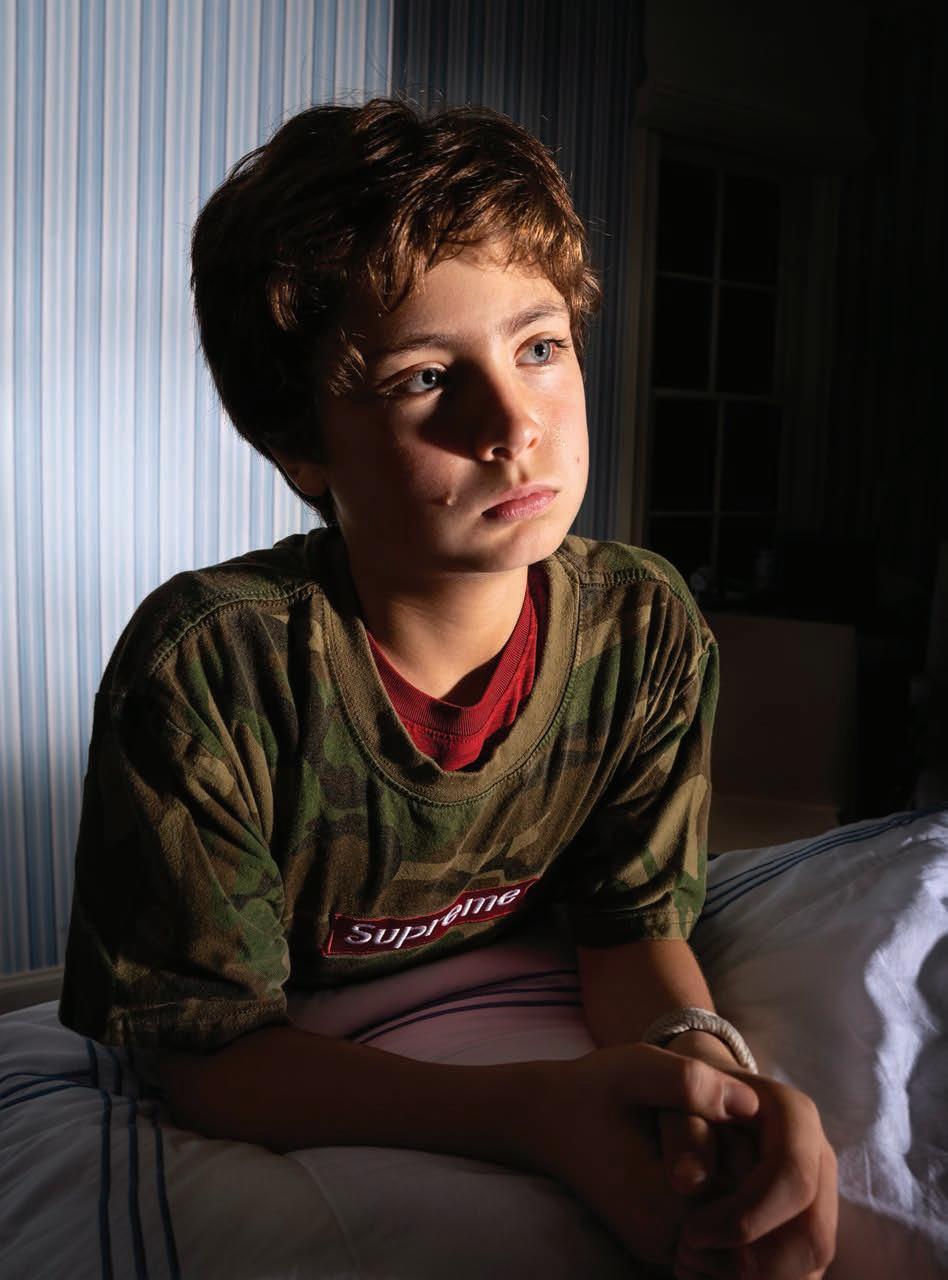

Pulled in by the lures of our generation, he wastes his days in bed addicted to scrolling from post to post. His textbooks are open, yet not a single page is marked. He nds himself struggling to even move his legs out of his perfectly formed Tempur-pedic mattress. e more he waits, the louder the screams of his mother become. “Get up, you lazy bones,” she cries. Finally, he conforms to her wishes. But after no more than thirty minutes of working, he nds himself sinking right back into that Tempurpedic mattress. is is my reality, and the same holds true for many across our nation. We can tell ourselves that we aren’t lazy, just stressed, and that wasting our time is a coping mechanism. But the truth is that we’re weak, weak mentally. e comforts of our modernized world have a ected the way we think, instilling poor values in our future generations. To continue to develop positively as a society, we need to understand that our individual happiness means nothing, as it does not contribute to society, only ourselves. Just as our ancestors have had to work and work and work, not for their enjoyment, but to support those around them, we, in a privileged nation, must learn the same discipline they had, and I believe that an NPC mindset is the way to do so.

Having an NPC mindset where we focus solely on our duties allows us to be the best versions of ourselves.

Our society is weak. As time has progressed, and the majority of people have gained rights, we have learned to take for granted the privileges that our country provides. Constantly chasing pleasure, we have come to believe that the purpose of life is to be happy. I beg to di er. What does happiness do for people other than yourself? Nothing. If our goals are only for the sake of happiness, any setbacks in our life become painful, but if our goal is to be useful, not only are setbacks easier to overcome, but happiness also becomes a reward to ourselves and those we help. And to maximize this usefulness, we must approach life as an NPC. Unless you are Patrick Star and have been living under a rock, you likely know something or other about video games. An NPC, or nonplayable character, is a preprogrammed character in a video game that accomplishes task after task repeatedly.

While calling someone an NPC is generally viewed as an insult, I propose that having an NPC mindset where we focus solely on our duties, allows us to be the best version of ourselves, as we become primarily focused on our usefulness rather than our happiness. Only when we stop prioritizing ourselves, and start prioritizing the world we live in, will we gain the strength we need to move forward

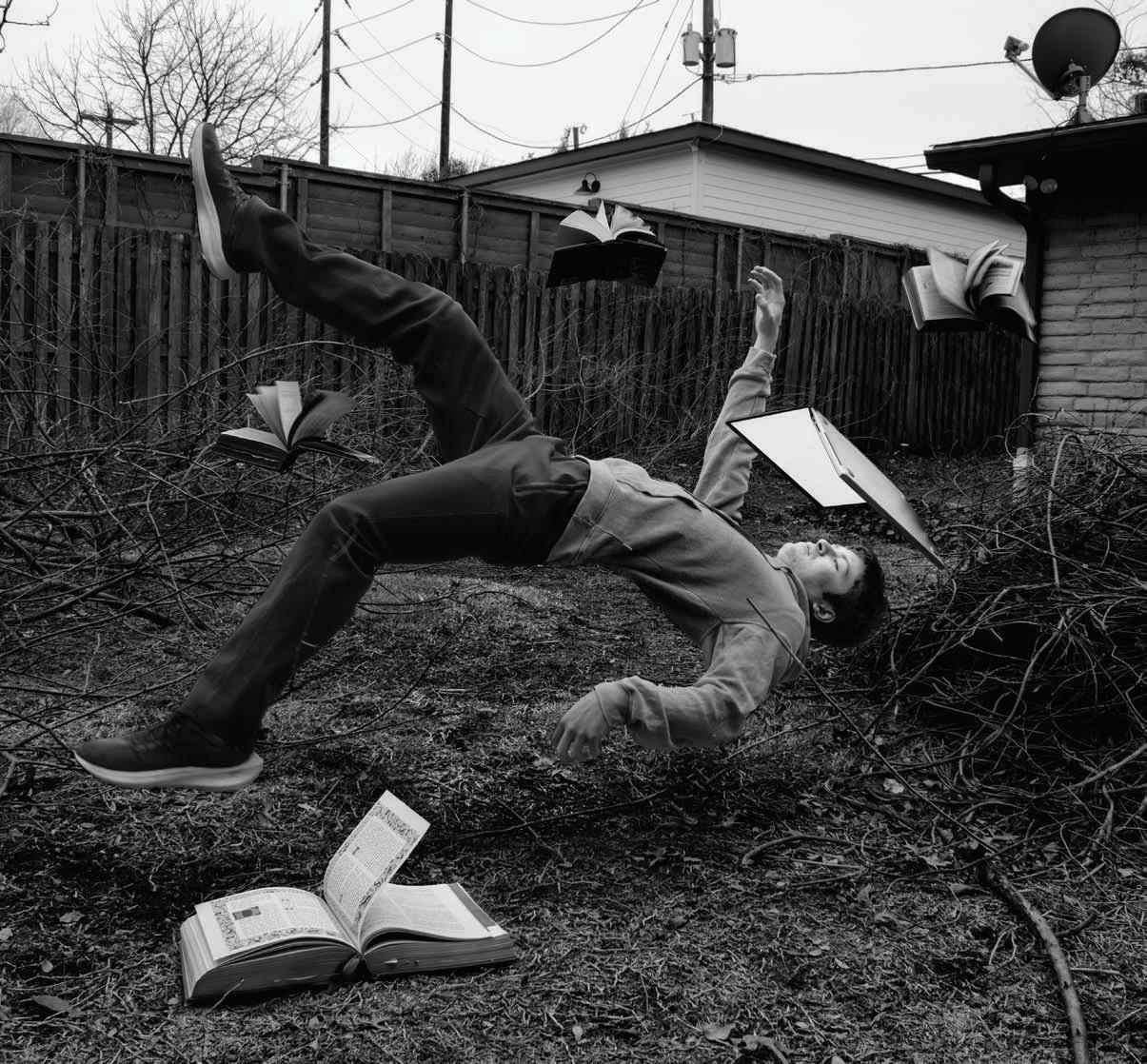

“Airborne” | Reed Sussman ’24

as a society.

Instead of instilling beliefs that would contribute to a prouder work ethic, we have brainwashed the future of our country with super cial values. Every time we like a post of someone applying heaps of makeup, wearing exposing clothing, or dancing inappropriately, we validate the idea that these are meaningful qualities. It is because of these failures that we have teenage girls advertising their body count and guys applauding their “achievements.” Life is not about enjoyment; it is about hard work, and it seems that only those who have struggled really understand this. Looking at countries like Singapore, we can see that strict governance has led to a better society with a highly developed infrastructure and leading education. Contrastingly, the United States leads the world in obesity, incarcerations, and teen pregnancies, not exactly what I would consider an advancing society, and they are all a result of our tainted values.

When we become just another fragment of history, nobody is going to care for a lone individual.

You may be asking why, if society evolved over thousands of years to give us rights and freedoms, am I now saying not to take advantage of these rights? e answer is, I’m not. It is completely valid to practice our freedoms, but I am proposing that individualism is a plague on those rights and the further progression of society. Simply put, we can’t abuse what we have. e reason we have these rights is because of our parents’ work and their parents’ work, and so on. Similarly, we too must think about the future of our country and our world before ourselves because otherwise, we risk losing the rights we so take for granted and, moreover, the progress that has been made. Our actions have consequences, not only for us, but also for our future generations, so it is of the utmost importance to value the greater good above our own satisfaction.

You don’t matter, at least not individually. You and I are just like aimless cockroaches wandering about in a world much larger than we can even imagine. at is why we call the individuals lost in war “casualties” or “collateral damage”: to try to minimize the e ects of their deaths because as long as the war is won, they were worth it. Similarly, it is the combined strength of a community that actually matters. When we become just another fragment of history, nobody is going to care for a lone individual; individuals will be obsolete, and people of the future will only care about us as a society and the impact we leave behind as a whole, which makes it imperative that we work towards something greater than ourselves.

We must strive for discipline and to develop a strong work ethic. Our country speci cally seems to struggle to gain these traits, while our foreign counterparts have begun to ourish due to their view on such values. Our rights have changed the way we view success, and they have caused our society to pursue activities that don’t contribute to anything more than themselves. Taking on an NPC mindset allows us to be more e cient, which in turn can allow us more meaningful uses of our time. We should derive happiness from the completion of meaningful work rather than through the validation of our own super cial beliefs. Before rejecting this idea, take a look at yourself and ask yourself: what do I contribute? Only when we contribute to something larger than ourselves, can we truly say that we mattered.

By Justin Tong ’24

The meeting started with shouting and arguments.

From individual soldiers to captains, no one seemed to agree on what to do, but everyone had a solution. Calls for order were met with more verbal assaults, and even the general struggled to draw the attention of all the soldiers. Nathan watched as the mayhem ensued around him.

“Time is of the essence.” As the captain strode forward, all eyes fell on him. e usually quiet yet rm leader suddenly was full of words. “We have to make a decision. Without action, we’re gonna get herded like sheep. So let’s just go forward and ght em head on.”

Shock and fear covered the faces of his soldiers, but the captain paid no mind. He left the meeting as quickly as he had made his presence known.

Nathan Bao had never enjoyed using his words. Where he was from, the only words spoken were lies. Everything he knew was a lie. From the restaurant owner who gave him “free” food only to suddenly ask for payment knowing that Nathan couldn’t a ord to pay, to the schoolteacher who said, “If you study hard and get

good grades, you’re gonna become rich,” to the solemn o cer who told him his parents would return, to the doctor who said his parents were just asleep. All of them told their lies with solemn faces, pitying the young boy, but no one tried to help. Empty statements rooted in lies continued to torment Nathan’s mind. Every day that his parents didn’t return, he grew more distrustful of the town that had wronged him.

Even though he loved his town, the scenery, the environment, the people and the lies enraged him. e town represented everything that had been taken away from him. e people he thought he could trust took his family and left him alone. He worked to earn money that never seemed to last and to leave the prison he was trapped in. e newfound seclusion within his home fueled him day by day. At the end of every day, when he returned home to the one-room shack on the edge of town, Nathan longed for the fairytale world he always saw in the books he read in the library or the “land of prosperity” he always heard about on the radio. So when the enlistment o cer came knocking one day, Nathan saw

it as a way out. e years of hard work along the edges of town had turned Nathan from a lanky child to a combatready man. e scars that riddled his face signi ed not only the battles behind him, but his preparedness for the wars ahead. Full of desire, Nathan dreamed of seeing the world and leaving the small town full of liars. He saw a future in the army lled with brothers and friends.

Years had passed since Nathan joined the army. He no longer was the lanky boy who had enlisted.

He’d own up the ranks, sparked not only by his skill in combat, but by his brain and strategy. Nathan’s ability to spot weaknesses in even the strongest enemies paved the road for many victories. His genius, however, was limited by a lack of desire to speak and to lead. Hence, he was limited to the captain’s position, quietly supplementing the general with strategy and guidance.

When the civil war had begun, Nathan hadn’t really known what to make of it. e small town he had grown up in had ourished into a city, demanding more and more resources and power. e liars from the town had grown into businessmen and politicians, and they started to form a militia which left the national government in a di cult situation. While Nathan despised the people from his town, a small part of him still appreciated what the town had to o er. It was, after all, his hometown. It had provided him with harsh lessons about life. But when the militia began to terrorize nearby towns, the army was called into action e city’s militia began to grow rapidly, attracting people by the thousands as they ooded into the city, motivated by the lies and outrageous claims made by the politicians and leaders of the rebellion.

By the time the army arrived, it was the smaller force, and while their soldiers were more capable ghters, the disparity in numbers started to overwhelm it. Soon, the army was forced to retreat, and the general called a meeting.

Initially, Nathan’s words at the meeting only caused more mayhem. Countless new ideas spewed from the 38

“Portfolio”

The ba le wasn’t easy. So many of the soldiers Nathan considered to be the strongest in the army were unable to adapt to the new, brutal fight.

crowd. All the soldiers feared the possibility of death. Nathan had recognized the army’s weaknesses; it wasn’t a lack of skill, but rather, a lack of desire. e same desire that Nathan had when entering the army, the soldiers lacked. e desire for revenge, for the future, for a better life, for success. As the meeting droned on into the night, and with no other reasonable solution available, the general chose Nathan’s plan.

e battle wasn’t easy. So many of the soldiers Nathan considered to be the strongest in the army were unable to adapt to the new brutal ght. Slowly but surely, the rebels were getting pushed back.

As Nathan pushed his own unit forward, straight into the heart of the opposing militia, he recognized many of his former neighbors. And with each shot from his ri e, he remembered the lies they had told him. “One day, when I get rich, I’ll pay you back.” “When you need help, call me. I promise I’ll be there for you.” “ ey’re just sleeping.” “ ey’ll be back.” e rage trapped within him unleashed in balls of fury around him. Blood owed all around him, tainting the ground. e thoughts of his past torment, the ruined image of his hometown, all fueled him as he charged on the front lines with only one thought in his mind: “ ey must pay.” By the time Nathan had reached the back line of the rebels, his once-spotless coat had become soaked in red. But when he surged

forward toward the leader of the rebellious militia and looked at the leader’s face, he saw himself.

He saw the young boy who had been told by the schoolteacher that he would become rich one day if he studied hard. Nathan, convinced that his eyes were deceiving him, rubbed his eyes and looked again. is time, he saw the scrawny kid who had been fooled by the lies all the police o cers told him. Blinking again, Nathan then saw the young adult who had returned home to the small shack at night after a day at work struggling to make ends meet. Finally, with one last shake of the head, Nathan saw the true face of the leader. e wicked smile covering the face of the leader taunted the captain. It represented all the past struggles that still haunted him. e strategies that made Nathan a tactical genius who always avoided direct con ict.

He sought to avoid battles, and he had run from his largest battle: his past. In the eyes of others, the lies they told were mere bs, used to comfort Nathan, not antagonize him. e lies had become weights on his shoulders, but now, standing before him, in the leader’s face, he saw the liars and the pain he endured. He recognized the sorrow each liar had: lying to a little boy who deserved the truth. e sorrow he would relieve each one of. So as he raised his bloody hands, aiming his ri e forward, he nally could say goodbye to the lies.

He sought to avoid ba les, and he had run from his largest ba le: his past.

“Gunsmiths” | Nathan Meyer ’24

By Grayson Redmond ’24

e barge’s door creaks open and spits me Out of its jaws like Jonah from the Whale. e shots ring out, but it’s too late to ee; I’ll take my place among the sand and shale.

War reverts all to their default setting. e Brits curse, the Czechs drink, and the waves swell, Laden with bodies, leaving me fretting My death at the hands of some German shell.

Oh, lovely France! Why must you always frown? Has the shrapnel torn a hole through your heart

As it has mine? I’m here to claim my crown Of thorns: the wire tearing my esh apart.

With nowhere to turn and nowhere to run, I’ll aim my ri e to shoot out the Sun.

“Firing Squad” | Nathan Meyer ’24

Story by Teddy Fleiss ’25

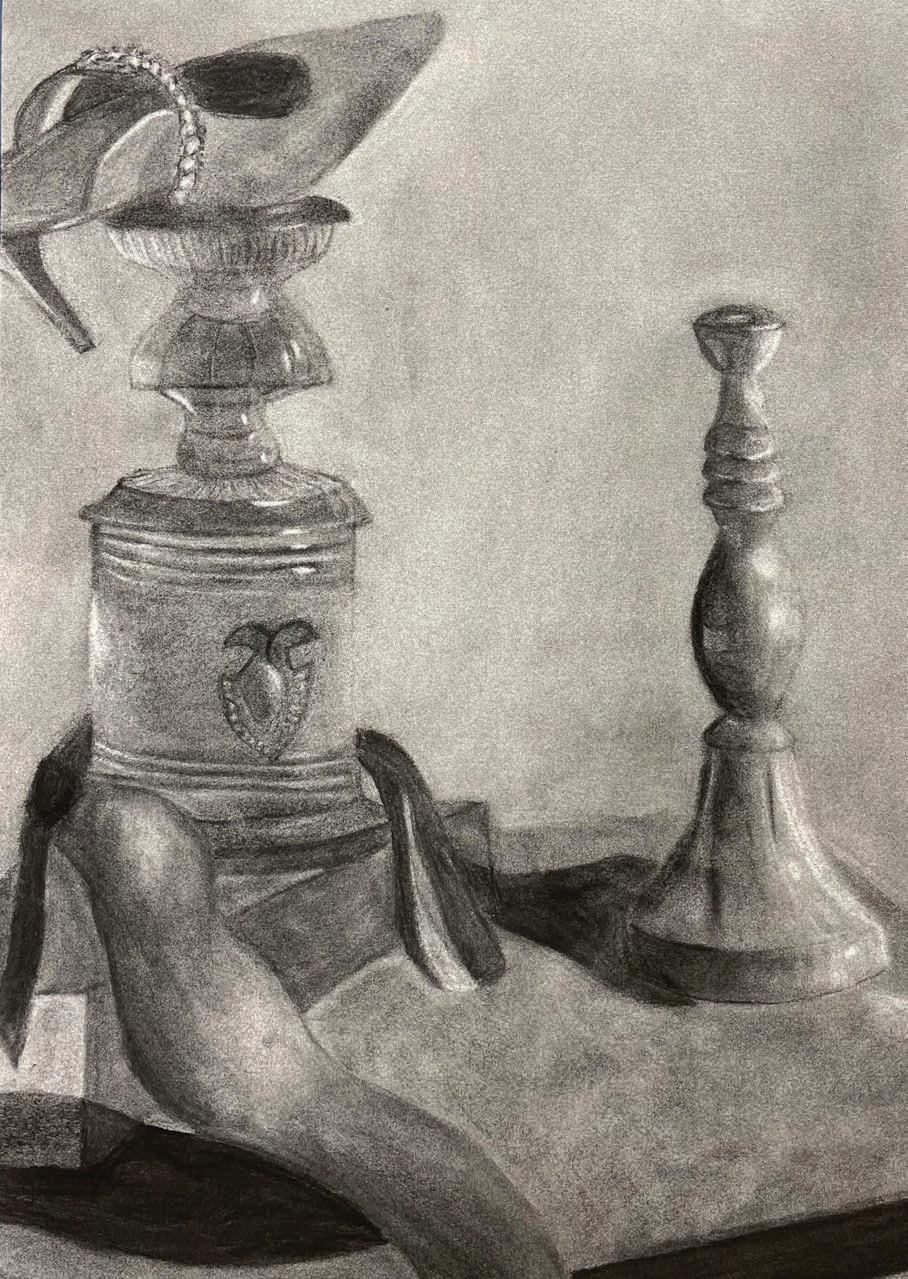

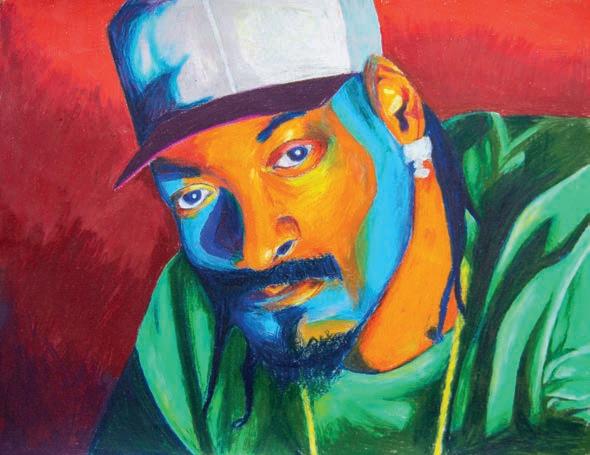

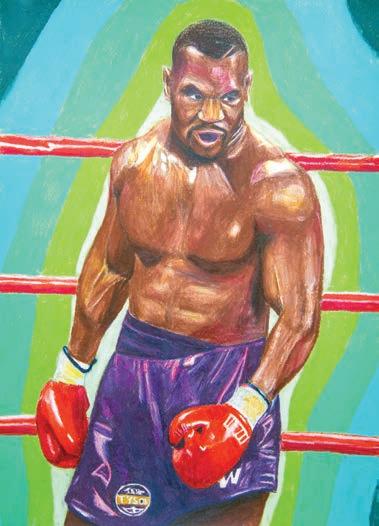

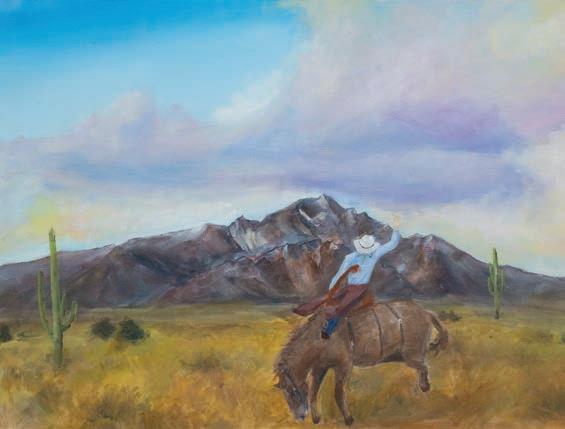

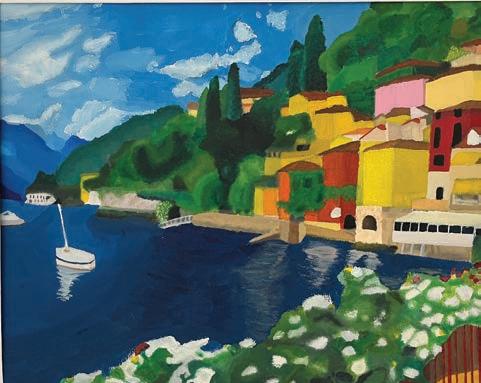

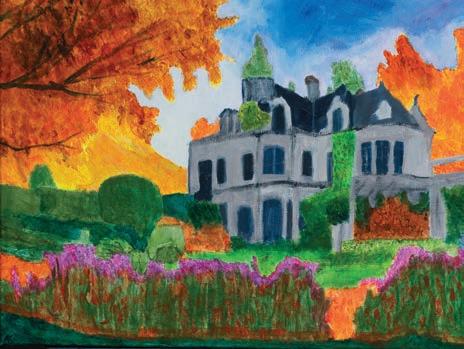

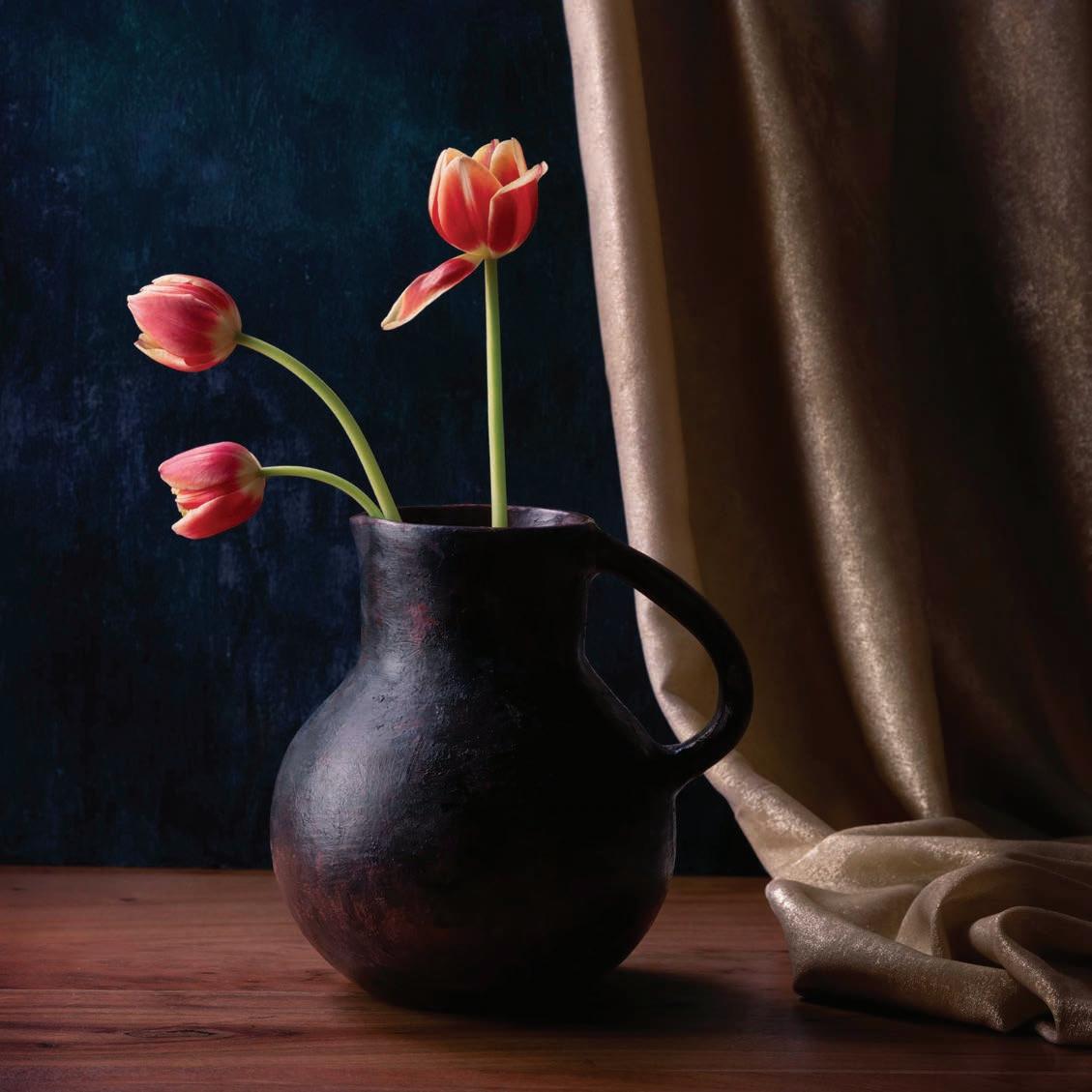

Drawninto the world of art from a young age, senior Holden Browning found inspiration in the creative lineage that surrounded him. With both his grandma and mom deeply interested and involved in art, Browning tagged along, learning a lot and nding his passion in the process.

“My grandma and mom are both into art,” Browning said. “From the time I was young, I always drew and painted with them. ey let me tag along, and it was always super fun to be with them.”

Browning’s mediums and styles began simply, starting out with basic markers before he began delving into more complex paintings, a transition encouraged by the creative freedom and many mediums o ered at St. Mark's, where Browning could explore new techniques.

“As a young kid, I started out drawing with just markers,” Browning said. “I then realized I liked it, and St. Mark's allowed me to explore other mediums I was interested in such as painting.”

When deciding on his next subject, Browning keeps a watchful eye for anything he sees that is interesting, no matter how unexpected it may seem.

“It’s pretty random,” Browning said. “A lot of times it's the hardest part for me; guring out what I’m actually going to do. One time, I was watching the Mike Tyson series on Hulu and just decided to draw Mike Tyson. Other times, we have set assignments or pieces that we have to complete.”

Browning also looks up to online artists who have succeeded in his mediums for inspiration and design elements.

“One guy I watch is called RobsonArtist, on Instagram,” Browning said. “His stu is super interesting.”

e culture of St. Mark’s art program allows Browning to excel, as he feels comfortable and excited to pursue art.

“Sophomore year was really fun because of all the people in the class,” Browning said. “Cooper Cole was in that class, and he made it really funny; I loved art that year.”

is camaraderie in the program allowed Browning to delve into deeper and more complex subjects.

“My favorite piece is probably the one I just did, on the native Americans,” Browning said.

Instead of concretely choosing what style to use, and sticking to that, Browning lets his medium decide.

“My style really depends on the medium,” Browning said. “For painting, I’m de nitely more abstract because of the brushes. When I paint, it’s more expressive and uid, but for drawing, I like to be more detailed.”

In one of his assignments, Browning was simply told to make a self portrait. However, he was able to inject a personal touch into his art.

“It was just an assignment to do a self-portrait with a palette knife,” Browning said. “Honestly, I like how it’s kind of blurry. Because it’s blurry, you don’t have to go into too much detail with anything. I don’t think people realize how hard it is to capture detail in paintings.”

Browning was able to develop his love for art at St. Mark’s, but is looking forward to following it in the future.

“I de nitely see myself pursuing art in college,” Browning said. “And maybe as a side-gig later on, too.”

Art by Holden Browning ’24

rough Browning’s long and impressive career as an artist at St. Mark’s, he has experimented with many di erent color styles and mediums. ese works showcase his versatility and outstanding ability as an artist, as they feature real-life subjects like Mike Tyson and Snoop Dogg in addition to more abstract concepts, such as his “Space Cowboy.”

“The Cowboy”

“Duel of the Emperors” Carson Bosita ’25

“Upli ment”

Henry Hoak ’24

Exposed to the wrath of the Underworld, Orpheus was a man amongst gods. His plight was particularly painful because of the impossibility of his task: to go to the Underworld, retrieve his wife, and return.

With no other options, Orpheus turned to his true skill and passion: his lyre. He used his unique and masterful playing of the instrument to secure his and his wife’s freedom from hell.

Instead of folding in the face of adversity, Orpheus was resourceful and brilliant, using what he had and what he knew to win the day.

Orpheus teaches us here that when we are stuck in a tough situation, we must also keep our heads about us as we work towards our goal.

As Orpheus fought through the trials of the Underworld, he was a man triumphant.

By Miller Wendorf ’24

Don’t think. Just run. Marcus heard the steady rhythm of his boots on the wet leaves, painfully striving to increase the tempo. Faster. Branches of dead trees brushed across his cold, sweaty face. His skin stung where the wind-blown branches made small cuts, but that pain was nothing compared to that in his legs, which were moving faster than they ever had in his life. Every muscle in his body screamed at him to stop, to turn back and surrender himself to the soldiers searching for him. I can’t, his mind screamed back. I’ve made my choice. ere’s no going back now.

He’d been running through the same muddy, withered, tree-ridden terrain that made up the war-torn French countryside for what felt like hours. All he carried with him was what he had on: his British army uniform, complete with a patch that read: Corporal Marcus Lawrence. He knew he should have brought supplies, but his desertion was a spur-of-themoment decision, not a premeditated a air. He honestly didn’t care where he was going, so long as it was as far away from the trenches as possible.

against a tree. As he got his breathing under control, he listened for the dogs, the shouts. Nothing. I must’ve lost them, he thought.

His breathing back to normal, Marcus wiped his eyes and looked around. I must’ve been running longer than I thought. e rays of sun that managed to pierce through the ceiling of leaves continued to trickle down to the forest oor like a soft spire of light, delicately illuminating Marcus’ surroundings. All around, the shouts of soldiers, the barking of dogs, and the distant booming of shells was replaced by the tranquil sounds of nature: leaves rustling, birds chirping, ies buzzing.

Marcus kept running until he couldn’t perceive his surroundings anymore.

Marcus kept running until he couldn’t perceive his surroundings anymore. Until all he could feel was pain, all he could see was the blood and sweat that stung his eyes, and all he could hear was his own heavy breath.

Suddenly Marcus felt a great bludgeoning force, and he realized he had tripped and fallen. Still hyperventilating, he clambered back to his feet and leaned

He suddenly noticed something hanging from the trees. Wait; there’s no way these could be… Apple trees! I’m in an orchard! Marcus couldn’t believe his luck.

Beautiful, lush apple trees growing within a few hours’ run of the front. He excitedly grabbed an apple from a tree and was moving to take a bite when he heard the crunch of leaves behind him. He turned around and dropped the apple in surprise.

A woman had walked into view carrying a basket of apples. She wore a simple white gown and was extremely beautiful in the soft sunlight. Marcus hadn’t seen a woman in months and was completely frozen by the sight of someone so beautiful, so pure. He stared in awe as she picked apples from a nearby tree and delicately placed them in her basket.

She didn’t seem to notice Marcus. Who else will I

A woman had walked into view carrying a basket of apples. She wore a simple white gown and was extremely beautiful in the so sunlight.

be able to get help from? he thought. She might be the only person I see for days. He cleared his throat and said, “Uh… excuse me, ma’am…” He could hardly get any words out, he was so enthralled.

She turned to face him and gave him a sweet smile. Marcus was enchanted. en, to Marcus’ surprise, she turned and started running away, letting out an angelic laugh.

Marcus snapped out of his trance. “Wait; who are you?” he called. When she kept running without response, Marcus began running to catch up with her. For several minutes, he chased the woman through the forest, occasionally calling out to her but never getting a response. Marcus watched as she walked into a clearing up ahead and continued following her. When he reached the edge of the clearing, he couldn’t believe his eyes. e forest parted to reveal a manor house. Not a modern manor house, but a medieval one, with gothic spires and hanging gargoyles. People wearing simple white robes like the one the woman wore performed various tasks around the manor, like tending to the gardens or cleaning the beautiful stained-glass windows. e woman he had followed was nowhere to be seen.

“Sir?” Marcus spun around to see a man in a chain mail shirt and hood, wielding a spear and a buckler. Medieval soldiers’ wear. “Lord Ambrose requires your presence,” the guard said.

“…Lord… Lord Ambrose?”

“Lord Ambrose. He requires your presence immediately. He doesn’t know you’re here, of course, but you’re not the rst stranger to stumble upon his lands. Follow me.” He sti y turned away and began walking around the manor.

A lord runs this manor. is… medieval manor,

Marcus thought as he followed the guard. is is unbelievable. It’s like this place just froze in time.

Behind the manor, an enormous banquet table was set with a feast containing various fruits, vegetables, and a giant pork roast. A host of men wearing medieval noble nery—several layers of linens and furs—quietly sat at the table. At the head of the table sat a middleaged, heavy-set, bearded man who wore a golden crown and a ne velvet cloak, who was dining while the others politely watched him, motionless. e lord eats rst, Marcus thought. Standing behind the lord’s seat was a rather ghastly looking gure in patterned red and white garments with a bell-adorned hat resting atop his pale bald head. e lord’s fool. e fool made eye contact with Marcus, ashed a toothy smile, and made a cryptic gesture. Something about the fool unnerved him.

After a couple of minutes, the lord delicately removed a handkerchief from his shirt, dabbed his lips, and said in a low bass voice: “You may begin.” e other nobles launched into their meal.

It was then that the guard cleared his throat. “My lord.”

Lord Ambrose looked up from his food at Marcus and the guard. All of a sudden Marcus felt very silly in his army uniform amongst these people in medieval nery. Even the guard’s chain mail had a certain polished, distinguished quality that Marcus’ brown, mud-covered uniform lacked. I must look ridiculous to them, he thought; but Lord Ambrose seemed unfazed, even giving Marcus a small smile. “Another guest, eh?”

“Yes, my lord,” the guard said. “He came by just a few minutes ago.”

“Very good, Captain. You are dismissed.” e guard bowed. “My lord,” he said, before marching

“Seeing Red” | Drew Wallace ’26

back around to the front of the manor.

In the elds beyond the manor house, he could see that some of the peasants had broken for lunch—some alone, others with their families.

“ is is… this is unbelievable,” Marcus exclaimed.

Lord Ambrose exchanged smiles with the other nobles at the table. “It’s a simple life.”

“No, but… how is this possible?” Marcus struggled to articulate his thoughts. “How have you maintained this… this existence”—he gestured vaguely to his surroundings—”when all around you things are… well… so di erent?”

Lord Ambrose smiled again, and shared a look with the fool, who grinned again. What is it with that grin? Something—everything—was wrong about it, but Marcus couldn’t tell why.

Marcus stopped staring at the fool as Lord Ambrose spoke. “You’re called… Marcus Lawrence, yes?” he said, squinting to see the name on his uniform.

Marcus nodded.

e woman seemed to be patting the ground. He cautiously approached.

“Excuse me; I think I’m lost,” Marcus said, but there was no response. Her hands continued working at the ground. She’s planting another apple tree, he realized. But what was that in the soil? It couldn’t be… “Wait, no… no…”

e woman stood up and stepped to the side, revealing the tiny apple tree sprout. But the sprout was not planted in soil, but in a mound of dead bodies crushed into the earth, bloody limbs intertwined.

Marcus looked up and saw that the beautiful woman was now staring directly at him. In her hands was one of the apples from her basket, with a bite taken out of it—but out of the apple owed not juice, but blood. at same blood caked her lips and teeth as she let out a endish cackle.

All of a sudden, Marcus felt very silly in his army uniform amongst these people in medieval finery.

“Follow me, Mr. Lawrence. I have something to show you.” With big, regal strides, he started walking away from the feast towards the edge of the clearing. e other nobles resumed polite conversation as Marcus jogged to catch up with Lord Ambrose.

After a few minutes of walking, Lord Ambrose motioned for Marcus to stop and pointed directly ahead of them.

Marcus exclaimed: “How have you kept up an orchard this beautiful—” He spun around. Lord Ambrose was gone. He was completely alone in the orchard with the woman, her back still turned to him.

Marcus collapsed to the ground.

Agnus Dei. e syllables ran through Marcus’ head.

Agnus Dei.

Latin. He was thinking in Latin.

“Agnus Dei.”

Wait, what? ese thoughts didn’t seem right.

“Agnus Dei. Agnus Dei.”

Marcus suddenly realized the Latin wasn’t thoughts.

“Agnus Dei. Agnus Dei! Agnus Dei!”

It was a chant. Being recited by hundreds of voices in unison.

e realization spurred Marcus to action, and he opened his eyes. He found himself completely naked, tied to the edge of an enormous stone balcony on the manor house. It was the dark of night, but moonlight illuminated

a crowd of the white-clad peasants, so peaceful in their elds earlier, fanned out in a crowd below the balcony, excitedly banging their farming implements against the ground and chanting:

“Agnus Dei! Agnus Dei! Agnus Dei!” e lamb of God. Marcus stared out at the crowd, speechless.

Marcus noticed movement behind him and turned his head to see Lord Ambrose emerging onto the balcony, closely followed by his fool. e fool was carrying a sharpened stone knife with engravings on the hilt. He looked at Marcus and ashed his unnatural smile again.

Amidst the chanting, Lord Ambrose walked up to the edge of the balcony where Marcus was tied and whispered in his ear, “You think yourself a learned man, do you not?”

Marcus nodded meekly.

“Every year, people like you learn more that was never meant to be learned. Meanwhile, we move further and further from God’s truth. We get further from Eden, from God’s holy place, every century.”

He placed his hand on Marcus’ bare shoulder. “You visitors sicken me. You all believe you have progressed, but you still sin, still ght in terrible wars. You distract yourself with new inventions that pull you ever away from as it was in the beginning.

“But we”—he gestured to the crowd of chanting peasants—“have found a way to overcome this. We have stopped the march of time. And thus, we are closer to God than anyone on earth. As I said, it is a simple life. A simple, holy life. But that life doesn’t come without a cost.”

Lord Ambrose took his hand o Marcus. “And now, you’ll do your part in maintaining our paradise. You’ll join the others in the orchard soon enough, of course. But for now, we must celebrate.” Lord Ambrose gave a nod to the fool.

e fool approached Marcus and deftly placed his knife on Marcus’ exposed wrist, before making a small cut. Marcus grunted in pain. Lord Ambrose

Marcus noticed movement behind him and turned his head to see Lord Ambrose emerging onto the balcony, closely followed by his fool.

quickly grabbed Marcus’ wrist from the fool and placed his mouth on the cut. Marcus could feel him sucking the blood gushing from the wound. e peasants below gradually ceased their chanting, their faces brimming with anticipation.

Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, Lord Ambrose let Marcus’ wrist drop. Turning his head to Lord Ambrose, he watched as the lord, just as he had done at the banquet table all that time ago, delicately took his handkerchief from his pocket, dabbed his bloodstained lips, and announced to the crowd in his low voice: “You may begin.”

In a ash, the fool swept the knife in a perfect arc along Marcus’ exposed chest, resulting in a gash running along his breast, perfectly uniform in depth. Overcome by the searing pain, Marcus screamed then, as blood poured from his chest and mouth in a steady dribble. To Marcus’ disbelief, the townsfolk surrounding the balcony leapt forward to get under the stream of blood. Red stains appeared on their white clothes as they desperately tried to catch Marcus’ blood in their hands, before lapping it up like messy toddlers.

Marcus laid his head down in exhaustion as the fool made another gash across his chest. is time he didn’t scream—he was too weak from the blinding pain. No more was he a human; he was reduced to a mute, submissive animal.

e peasants continued gorging on his blood. More slashes came, but Marcus hardly noticed. All that was left of what he could perceive was numb pain and the incoherent sounds of the mob.

And then he perceived something else: a high-pitched scream coming from the sky. Finding a second wind of strength, Marcus strained his tired neck and looked up. e sound was familiar. Straining his eyes, Marcus noted a ash of steel glinting in the moonlight—and then a deafening explosion that lit up the night sky as the belltower on the other side of the manor house collapsed,

“Totality”

engulfed in smoke and ame.

A stray shell. Artillery from my battalion. A wave of memories of the front ooded through him, a whole world that had left his mind. Memories of shells, masks, bayonets, wire, of metal, chlorine, dirt, and mud. Memories that were the reason he’d run in the rst place but seemed insigni cant compared to his present su ering.

Marcus blinked. He couldn’t believe his own eyes. Everything in the manor was di erent now. e apple trees surrounding the clearing were dead, spindly stumps that bore no fruit. e manor was crumbling, ruined, decayed. e damage the stray shell had in icted on the belltower was insigni cant compared to the ruin caused by the gnawing sands of time.

A spell had been broken. Marcus now saw the manor for what it truly was.

Marcus’ blood, even as it ran out through their hollow ribcages like drizzle trickling down a window shutter. ey didn’t even notice the shell. Just like they haven’t noticed the ruin of the past millennium, Marcus thought. And suddenly, despite his weakness, Marcus’ lips twisted into a pitiful grin. He started laughing. It was a wretched, gurgling laugh owing to his lack of a tongue, but a laugh all the same.

Lord Ambrose’s rotting face contorted. “Why is he laughing? Shut him up!” Another slash of the knife, this time on his temple. Blood ran into his eyes, and he could feel consciousness receding. And yet he kept laughing. ey have no idea, he thought, as the next slash went across his throat. In a thousand years, they still won’t know. e last thing Marcus heard was the sound of his own laughter.

Finding a second wind of strength, Marcus strained his tired neck and looked up.

And the people? Filled with dread at what he would see, Marcus lowered his gaze to where the villagers were feasting on his blood. Before him was a legion of animated corpses. ey were the same peasants that had formed the crowd moments before, no doubt; they remained gleefully lapping up Marcus’ blood. But their simple white gowns were now yellowed and deteriorated with age, haphazardly clinging to their rotting bodies.

Lord Ambrose’ nery was worn with age: his cloak was threadbare, and his golden crown had been rendered a dull pewter. Where his face had been, Marcus saw only bones and rotting esh, no di erent from the crowd below them. Only the fool remained unchanged, his pale features the same as ever. e fool ashed his sickly grin, revealing long, sharp fangs caging a forked tongue.

e peasants’ and Lord Ambrose’s behavior remained unchanged. e legion of corpses continued to swallow

“ ose are his, all right,” Private First-Class Adrian Bradley said as he kneeled by a set of footprints. “Same boot size and all.”

“Good job, Soldier. We thought we’d lost him,” said Sergeant Henderson from above him.

Bradley looked up from the tracks to see Henderson anxiously looking at his watch. Next to him stood Private Richards, holding a leash connected to a bloodhound.

Sergeant Henderson shook his head at his watch. “I know that we only just now found his tracks, but there’s no way we’re nding Private Lawrence within the next hour. We have to report back to base camp by nightfall— captain’s orders.” He sighed and started back in the direction where they came.

Bradley stood up and had started to follow him when he noticed something out of the corner of his eye. “Wait— look!” he cried. Henderson and Richards spun around.

Ahead of them were three beautiful women in white gowns, picking apples.

By Nathan Aldis ’26

In shadows, Robert emerged, a word thief, Skills and deviousness unmatched, He stole Words and sentences without a catch rough unguarded halls and silent courts, He pilfered letters it was his T R E A T. Line by line his thievery wouldn’t stop, And soon whole paragraphs were naught but Periods and Commas.

Always uncaught none knew the words To convict him. No rumors, no talk no news, And none sought. e perfect crime, Was now his. Trouble was without e chitchat, People found no Way to connect. Not even Robert, King of Words. Poor Robert, lonely, so sad. He Began to send letters of letters from His stash. Upon inspection he Realized to his horror someone Had stolen his words

By Mitchell Galardi ’24

Ty wrestled himself out of the creamy Bog and with an ardent punch, Escaped the land. After this, a ower Emerged with a billowing smoke And a blue, icy dragon crest Adorning it. Ty, with a roll,

Freed his whole body. Observing his rolls Of a fat was a gure sliding with a creamy Consistency. Ty grabbed his ancestral crest And summoning that ancestral power, punched e mysterious leviathan so powerfully, smoke Pu ed from the creature’s vents. A ower

Of pain came down on Ty. His spaceship’s ower Insignia was visible to him over the green rolls Of hills. He wanted to escape this world and smoke With his buddies back on Earth. Maybe enjoy a creamy Soda. But a ght with a serpent alien was a punch He’d rather pull. All he could do now was lift his crest

And hope for the best. He needed motivation and his crest Gave him that. A reminder of his familial ower.