8 minute read

Urban Regeneration

01

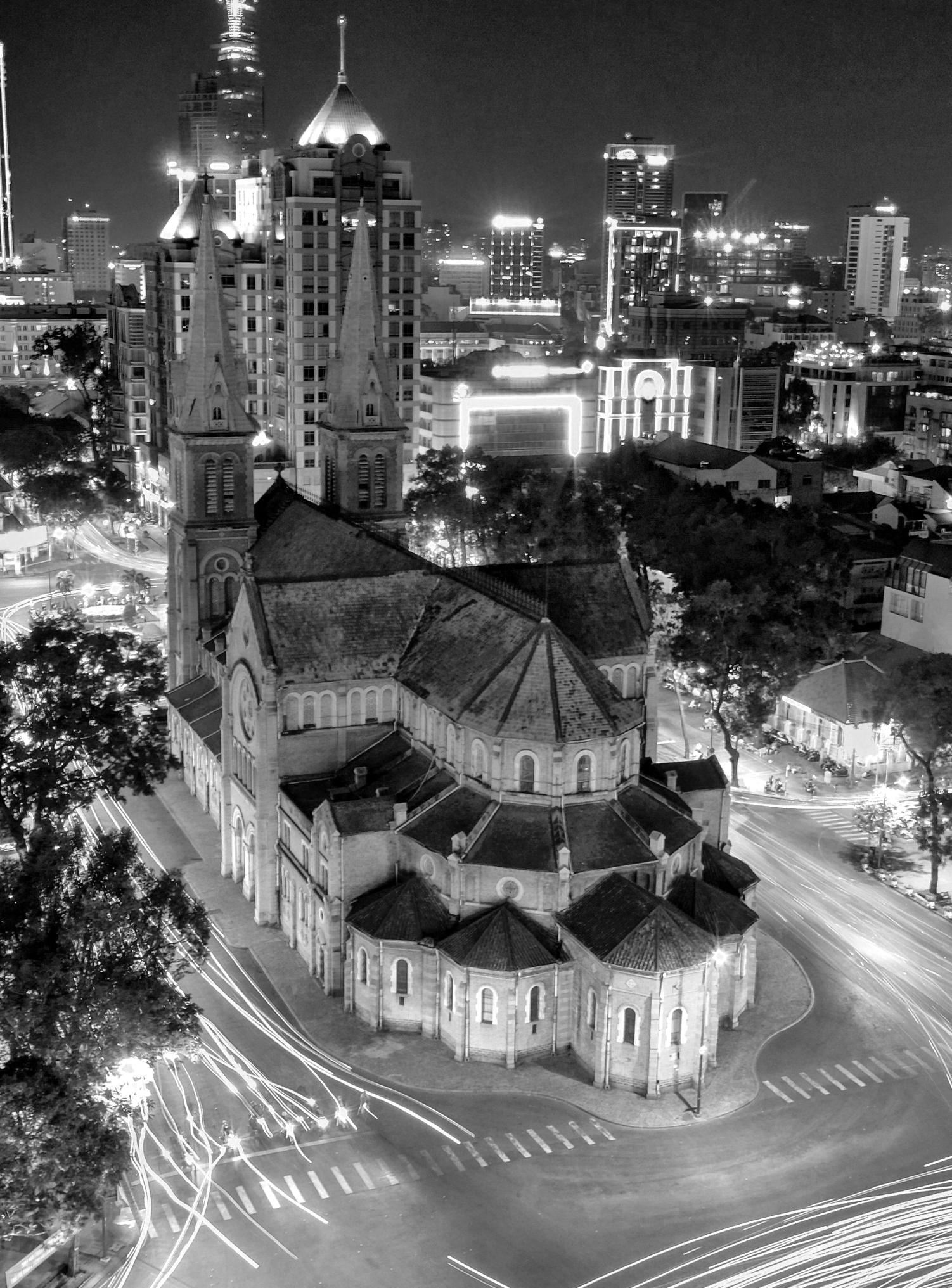

Credit: flickr.com Thibault Sergent

Advertisement

URBAN REGENERATION

a way forward for ASEAN Cities Sustainable Development

B | The UNESCO Creative Cities Network

C | Heritage Preservation and Economic Development in the ASEAN Countries

In preparation for the workshop, the team studied District 4’s urban history and present condition. A puzzling contradiction immediately emerged: that the richness of values by the spontaneous development of District 4 urban fabric conflicted with the current trend of high-rise and highly dense urban areas throughout Ho Chi Minh City and its surrounding areas, a development that has been done – very often – at the expense of the local identity and its established culture.

Many areas of this little island in the former Saigon remain quite original. Their character is determined and defined by the locals and the majority of buildings that remain were developed by the district’s first inhabitants. Despite this history and cultural richness, change is inevitable. District 4, like the rest of Ho Chi Minh City, is an area in flux. Therefore, to preserve its originality without sacrificing its livability, we propose the implementation of several sustainable and place-sensitive projects in a collaborative setting with academics, industry partners, and innovative and eager students. A brief digression on factors affecting urban development at the global and Asian level can help to better put local facts in the right perspective.

The Broad Context: Urban Development in Asia.

As argued by Brian Roberts and Trevor Kanaley (2006, p. 17), “urbanization, or the spatial concentration of people and economic activity, is probably the most important social transformation in the history of civilization since man changed from being nomadic hunter-gatherer and adopted a more settled, subsistent agricultural way of life.” As human beings have progressed into the globalized era of the post-ideological age (Žižek, 1997), modernization and urbanization seem to be an inevitable phenomenon. This claim is encapsulated by Edward Glaeser’s Triumph of the City (2012), through which he articulates that an urban center is an engine fueling economic growth, educational opportunities, social cohesion, and the development and allocation of human capital. Although much research on urbanization has historically focused on the global north, and in particular highlights those cities most impacted by the Industrial Revolution and the 21st century digital technology boom, the world’s contemporary urbanization growth is best explored in a global south context, particularly in Asia.

The UN World Cities Report has predicted an outstanding growth scenario where the population in Asia is estimated to grow from 3.78 billion in 2010 up to 5.26 billion in 2050. Other sources investigating urban populations forecast a growth of around 70% over the next 25 years to more than 2.6 billion people living in cities or megacities, meaning that an additional billion people will be migrating from rural to urban environments; “this transformation will involve major change for Asian societies with new forms of housing, employment, consumption, and social interaction for individuals and communities” (Roberts & Kanaley, 2006, p. xi). Thus far, the transformation of Asian societies has resulted in a significant reduction of poverty and increased living standards, but at an unprecedented social and environmental costs. Hanoi, for instance, is consistently ranked among the world’s most polluted capitals due to the high volume of vehicles, construction, energy consumption, and factories located there (Vuong, et al, 2021).

As acknowledged by Roberts & Kanaley (ibid, p. xiii), “the projected continuation of the urbanization process will further strain the sustainability of Asian cities unless major improvements in city governance and management, and massive programs of infrastructure investment are implemented. The continuation of present practices and levels of investment could well see the sustainability of many Asian cities undermined, periodic urban environmental crises, and the gradual erosion of quality of life for the majority of urban populations”. Fortunately, adjustments to HCMC’s master

Credit: unsplash.com Arkady Lukashov

plan (with a view towards 2040 and 2060) are prioritizing these concerns, as announced by Nguyen Van Nen, the Secretary of the HCMC Party Committee; “the city has set a goal by 2060 to become an international trade and financial center in the AsiaPacific region. It aims to have an attractive working environment with diverse culture and heritage conservation and a scenic river system. Sustainable urban infrastructure and climate-change adaptation are among the goals set by 2060” (VietnamNews).

Within this framework, it can well be argued that development in Asia, and Vietnam in particular, is therefore tied to the growth of sustainable cities. Economically dynamic cities will continue to be the main drivers of production and trade, which provide the basis for rising standards of living and supporting populations, but only if careful planning will take into account their spatial and cultural dimensions. quality of public spaces, which negatively impacts inclusiveness and social relations among inhabitants.

The physical decadence of some buildings and open spaces is an inevitable consequence of the above and can be seen in the empty, derelict, poorly maintained, misused, or ill-transformed buildings and spaces of downtown. This presents a negative feedback loop that can be potentially reversed. On the other hand, the former Saigon port and the “spontaneous neighbor” presents an interestingly complex and varied scenario of buildings and people, where different functions correspond to a vibrant combination of people, histories, and cultures.

Balancing these strengths and weaknesses with opportunities and challenges, we offered the project’s students thematic targets to address:

Our team worked on the former industrial port of Saigon at a range of scales spanning the global, precinct, and site-specific levels. Heavy traffic in the city center demonstrates the lack of a comprehensive mobility strategy which should include both pedestrian pathways/spaces and smart public mobility interventions. This in turn has negative effects on the presence and the 1. Creative and cultural ecosystem 2. Conservation 3. Public realm 4. Accessibility and connectivity

Credit: unsplash.com Tran Phu

B. THE UNESCO CREATIVE CITIES NETWORK

To inform their approach, we advised the team to consult the mission of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN), imagining that Ho Chi Minh City might eventually join as a member. As stated on the organization’s official website:

“The UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN) was created in 2004 to promote cooperation with and among cities that have identified creativity as a strategic factor for sustainable urban development. The cities which currently make up this network work together towards a common objective: placing creativity and cultural industries at the heart of their development plans at the local level and cooperating actively at the international level."

We instructed the students that, should Ho Chi Minh City eventually join the network, it would foster partnerships across motivated public and private sectors, in addition to civil society, to:

• strengthen the creation, production, distribution and dissemination of cultural activities, goods and services;

• develop hubs of creativity and innovation and broaden opportunities for creators and professionals in the cultural sector; • improve access to and participation in cultural life, in particular for marginalized or vulnerable groups and individuals;

• fully integrate culture and creativity into sustainable development plans.

The workshop organizer and promoter of Heritage Preservation & Economic Development in ASEAN, Arch. Luigi Campanale, believes that the principles of the UNESCO Creative City Network could be combined into the most modern urban design approach of Smart City, creating the opportunity to implement innovative technologies to preserve urban area identity and to increase the overall quality of life through environmentally friendly and more culturally oriented cities.

Credit: unsplash.com Ban Hoang

The Heritage Preservation and Economic Development (HPED) series offers a very simple observation: the commonplace juxtaposition between past and future in Asian cities is no longer acceptable. It has led to loss of architectural and cultural heritage values on the one hand, and to wild and ill-planned urban development insensitive to the cultural, architectural, climatic, and social specificities of its specific contexts on the other.

New urban development in Asia looks more or less the same: high-rises and shopping malls have substituted old patterns of streets, lanes, and squares of the cities of the past. Such development patterns have deteriorated a unique sense of place and led to a universal and dull vision of modernity. Nevertheless, it is already evident that the growth in most Asian cities in the past decades cannot be limitless: the transportation, infrastructure, health, social, cultural, and economic issues caused by the “sprawling city’, endlessly spreading into agricultural land, is not sustainable. It is thus crucial to study good practice for sustainable urban development in Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asian countries have a specificity of their own in providing a rich variety of heritage buildings belonging to the local

Credit: flickr.com Trang Le

Credit: shutterstock.com Vietnam Stock Image and colonial past. Following decades of decay and demolition (especially of colonial era buildings), citizens and authorities in Southeast Asian countries have recently reached a new conscience on the importance of their architectural past.

The HPED event aims to further raise awareness on the importance of preserving this past. Southeast Asian cities have strong traditional qualities in terms of beauty, social, economic, functional integration, and complexity that should be recognized and served as powerful sources of inspiration for new development. In other words, past, present and future can blend seamlessly along the timeline and from all points of view, contributing functional, architectural and aesthetical value. We believe that this could be a highly effective approach for future urban development, offering many competitive advantages, such as:

• cultural and social identity of a community which has its ancient roots;

• reduction of transportation and infrastructural costs;

• ease of urban “smart city” management; energy efficiency; • economic development as traditional mix-used buildings will create local jobs and new economic activities;

• cultural driven tourism development.

Preserving heritage translates to a better quality of life for everyone, and this is why we believe that the architectural past of a nation should not only serve a romantic memory but also a hopeful promise of the future economic and social development of a country.