21 minute read

HCMC Smart & Creative District

A. DISTRICT 4: HISTORY & CULTURE

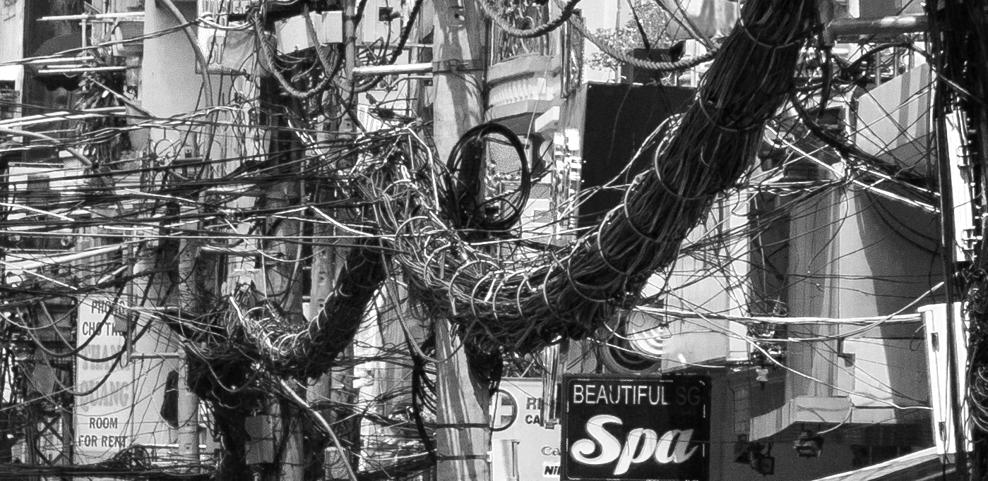

District 4 is the smallest district in Ho Chi Minh City and is located between District 1 to the north and District 7 to the south. It is, in effect, an island, surrounded by the Sai Gon River, Kenh Te Canal and Ben Nghe River. New developments have sprung up on the north side of the district, facing the financial area of District 1, and next to the Cau Mong, a historic bridge designed by Gustave Eiffel. Residential and office developments follow the Kenh Te Canal. A deeper exploration into the district reveals a collection of densely populated hems.

Advertisement

Excluding the port area, the urbanisation of District 4 is a relatively recent occurrence. Up until the late 1950s, much of the current area designated as the Khanh Hoi Ward was marshland. The streets Ton Dan and Doan Van Bo were developed, but behind these were individual residences, not the tightly packed alleyways that are found today. The port facing the Sai Gon River was the most developed area at this time. While a port has existed here since the 17th century, it was the French who expanded it to run the length of the district.

Neither the French and later the Americans were interested in the other areas of the district. It was left to the many migrants coming up from the Mekong Delta. Using their knowledge of land management, they gradually occupied and developed the district in their own way. It is this bottom-up approach rather than a master planned development that makes these alleyways and the life contained therein unique to the city.

This impromptu development, however, meant that very little formal authority and regulation existed, and thus District 4 eventually became overrun with criminal activity and developed a gangland reputation. Truong Van Cam, more commonly known as Nam Cam, was one the highest profile mafia bosses in Vietnam, and was based in the middle of District 4, on Ton Dan Street. By the mid 1990s, he had established extensive gambling, money laundering and prostitution rings, and was able to dominate the district. By ordering the murder of a fellow gangland leader, Dung Ha, he triggered the downfall of his empire. He was executed in 2003, and the city authorities cleaned up District 4, giving it new life.

Redevelopment is now an emerging phenomenon in these narrow spaces. As families expand in size through marriage and accrue more wealth due to increased economic opportunities, there is an interest in rebuilding or adding extensions to homes. Many of the dwellings in District 4 are now

Credit: unsplash.com Giang Duong

Credit: sna-architecture.com Luigi Campanale

four or five stories high, and are beginning to show expressions of wealth, such as the instillation of elaborate metal gates to the properties. However, many of the homes in the hems remain simple. They are functional in design and often single story. A few homes have kept small garden spaces, which are often very lush. These tend to be occupied by the district’s elderly residents.

The economy in District 4 reflects that of the country. There is a high number of self-employed and family operated businesses. The geographical implications of limited access means that many of the residents work locally within the district. During the day, many of the houses dedicate their ground floor family room to small service industries like corner shops or cafes. These revert to family rooms at the end of the afternoon, and then transform into motorbike storage units overnight. Another important economic infrastructure is the network of wet and street food markets, the most unusual one being the Doan Van Bo market, which stretches from the Calmette Bridge, to just before the Tan Thuan 2 Bridge, which follows the banks of the Sai Gon River. A smaller market can be found on Hem 200 Xom Chieu. This market has developed a reputation for high-quality home cooked food, and one many foodies visit to find traditional meals.

The neighbourhoods of District 4, initially meant for smaller communities, have developed into complex and rich cultural mazes interwinding communal life, leisure activities, trade, religious ceremonies, street food consumption, and transportation, all only meters apart. Make-shift badminton, hacky sack, and chess playing in alleyways are also a common sight.

From 2000 to 2018, the Vietnamese government instituted a movement called Uniting Society Through a Cultural Life (toan dan xay dung doi song van hoa). This movement was intended to foster participation and socialization through cultural and sporting activities, irrespective of social status. The movement resulted in significant changes for District 4, including a building of a public children’s playground in Ward 5 and Ward 16, Khanh Hoi Park Square, Khanh Hoi Park Water Fountain, Van Don Sports Club and Khanh Hoi Stadium. These infrastructures have encouraged and supported myriad indoor and outdoor activities, with lease premises for private function and services in auxiliary areas.

In the 2020 - 2025 term, The People’s Committee of District 4 aims to improve on economic, cultural and social development through urban embellishment, poverty reduction and building a smart city. Despite these initiatives, it still feels as though District 4 has developed alongside Ho Chi Minh City rather than intergrate with it. The area’s physical separation from District 1 and 7, and the development of bridges which serve to bypass the area rather integrate with it. However, the geographic barriers and local-based life of this district has greatly contributed to the preservation of its sense of community and informal heritage.

B. OUR APPROACH TO REGENERATION

Our approaches to the regeneration of the port area in Ho Chi Minh’s District 4 are developed from an unusual point of view: the guided, but untested and idealized viewpoint of university students working in intense, short-duration study groups. Is it a utopian fantasy to entrust the future of the city to decisions made in this way? With our inexperienced design teams, we clearly cannot target immediate and operational objectives. But by asking the young people today, who will soon be adult leaders tomorrow, to design a city-space they would like to inhabit, we can encourage a participatory process in enlightened city-thinking and city-making.

Credit: unsplash.com Di An H This appears especially important when we approach the functions of heritage in planning and design. How do younger people experience the past? How do they value that experience? What could be the imagined evolutions for material and less material traces of “the past”? What models do they find for the community adoption and participation of heritage in the contemporary city? What traces of the present do they wish to leave to future generations?

One heritage of Doi Moi that we have all seen is the remarkable series of housing towers rise up along the city’s waterfronts. While these constructions form aspirational visions today for certain populations, they will continue to create long-lasting impacts on the face and character of the city. The more iconic works will no doubt appear in the near-future as a lasting heritage of Ho Chi Minh’s socialist-led entrance into, and development through, international capital markets. As the city moves further now into the 21st century, Ho Chi Minh City will certainly embody a fresh aspiration: to serve as a model for sustainable urbanism in the Southeast Asian region. Seen from this angle, we ask our novice town planners: is it possible to arrive at robust functional alternatives to the enormous middle- and elite-class housing estates that have characterized the city’s riverfront construction from 1990 to 2020?

We understand that considerations of land value appreciation and increased population density form vital and enduring foundations for urban development. These goals are evident in the land- and riverscapes produced by Ho Chi Minh City’s vast housing estates of the past 30 years. They are well-understood in a shared, globalized world system that has mastered price valuation as a measure transcending national difference. In urban models throughout Europe, Africa, the Americas and Asia, it is easy to find regional and world capitals in which similar ambitions have produced analogous skylines. We are familiar with their remarkable engineering and financial consequences and, as importantly, with the problematic heritage of those decisions: elite populations partially withdrawn into vertical concentrations of class distinction – a city composed, in part, of detached islands of privilege settled against, and seemingly impermeable to, a spreading horizontal dimension of increasing ecological deterioration and social disorganization, that same horizontal dimension that, over time, welcomes a daytime-only population of “servant underclasses” living in distant and disadvantaged perimeters beyond the developing centre.

We envision an imaginative path to sustainable alternatives. With a view to both past and future heritages, can the port areas of District 4 be seen as an opportunity to experiment alternative urban attitudes - that might lead to places, processes, events, and occupations whose legacy would be an aspirational symbol of a more - and not less – sustainable neighbourhood? A more – and not less – cohesive city? In the projects ahead, we ask our young

Credit: unsplash.com Alena Kuznetsova designers to imagine, responsibly, what their decisions might leave to the future. We ask them to allow that heritage to evolve, as naturally as possible, from the legacies of a diverse Vietnamese identity deeply rooted in rich human interactions with the natural and urban landscapes. To focus nearby in space, on the characteristics of the site itself, and further away in time, on historic and idealized views of Vietnam’s own economic, social and cultural cohesion.

Our two key heritage considerations may be stated as follows:

• On the existing site, do we find capital assets – formal heritages of architectural structures and urban functions - that, as historic traces, can help stimulate new developmental attitudes?

• In the country’s long history of urban culture and rural-urban exchanges, are there transmitted forms of tradition, routine, and know-how – diverse and informal heritages of a

Vietnamese identity – that are likely to stimulate the vibrant core of an urban project?

The answers to these questions form the main thematic lines of inquiry and development for the four projects that emerge.

C. FORMAL HERITAGE AND INFORMAL HERITAGE

Ben Nha Rong (Ho Chi Minh Museum) perfectly fulfils the role of symbol and function for formal heritage on the site. It unambiguously conserves the structural past of the political and economic nation. Built by the colonial French in characteristic architectural style to mark Saigon’s principal commercial port, it has been converted into a museum for conservation and display of the revolutionary education and development of Ho Chi Minh (the man), modern Vietnam’s founding figure. The Ben Nha Rong is unique on the site as the sole architectural element of historical exception and distinction. Its role in the long territorial and spiritual history of Vietnam, its properties as a place of nation-founding, and its testimony to the intercultural and colonial heritage of Saigon must, without any ambiguity, be recognized and preserved by future developments at the port. status is not, however, limited to existing international organizations, sanctioning expert interpretations and accepted universal histories. Many aspects of heritage creation remain, informally, in the public domain. Individuals and groups freely recognize and protect parts of their own past that they consider essential to a sense of community belonging.

These characteristics became evident in our groups’ walks along the riverside in District 4 and through the narrow hems of its neighbourhood streets. As a collective design team, we choose to highlight and examine four approaches to informal heritage. Each of the four selected identities maintains a central role in the productive relationship that Vietnamese people establish with their exceptional landscape through the long historical period.

Official international organizations like UNESCO have, over the past fifty years, contributed importantly to the definition and protection of natural and built places of exception. They have, through time, enlarged their own definitions of heritage, extending notably from “material signs” to include intangible cultural heritages that may be transmitted in the public domain as practice, belief, skill, and tradition. The recognition and cultural integration of heritage

Credit: unsplash.com Giang Duong

THEME 01: THE CITY OF MAKING THEME 02: THE CITY OF WATER

THE CITY OF MAKING

02

THE CITY OF WATER

03

THE CITY OF STREET & FOODS

04

THE CITY OF SPORT

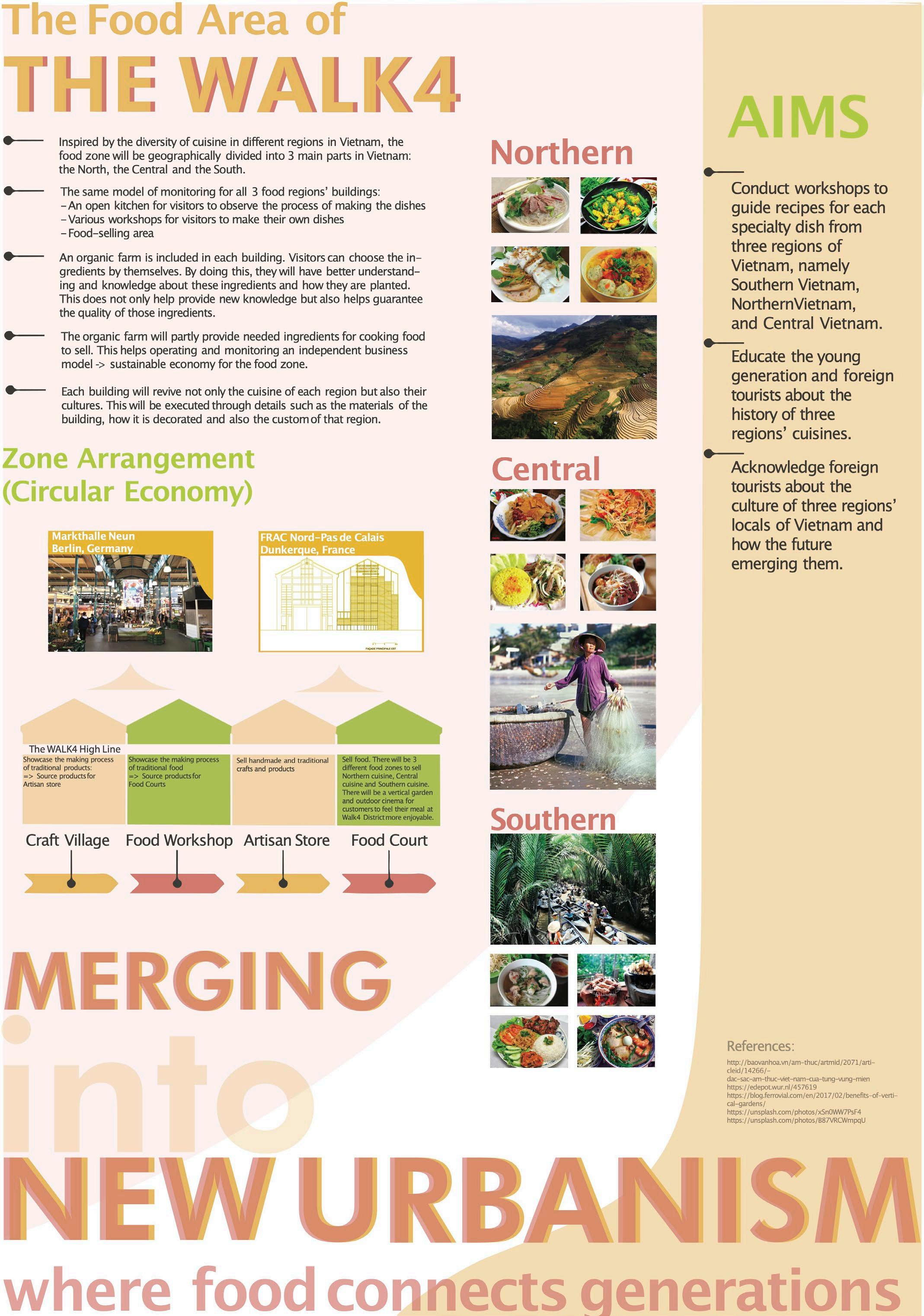

01. THE CITY OF MAKING

The hems of District 4 are activated by a typically Vietnamese ecosystem of dense, informal arrangements between small shops, street businesses, food preparation, outdoor marketplaces, mechanical workshops for making and repairing. The hems demonstrate the rich social heritage that permits large urban centres in Vietnam to maintain the customs, goods and convenience of rural village life. The City of Making binds physical and behavioural patterns of closeness to the intergenerational transmission of know-how. It leverages these into creative knowledge through new tools for communication, sharing and fabrication.

Quan Nguyen Yen To Hanh Phan Duyen Duong

02. THE CITY OF WATER

The relation of Ho Chi Minh City to its rivers, streams and nearby seaside is not only an essential figure for understanding the city, but can be seen as a striking example of the productive relationship that has tied, for millennia, the Vietnamese people to waterways and coastlines throughout the country. Linked, but not limited to contemporary uses for transportation, food, health and leisure activities, the City of Water must be understood first, in relation to the river’s foundational role (city site) and second, as an emblematic image of the city’s sustainable future (management of water quality with potential water level variations of magnitude).

Linh Nguyen Linh Luu Long Nguyen Quyen Ngo

C. FORMAL HERITAGE AND INFORMAL HERITAGE

THE CITY OF MAKING

02

THE CITY OF WATER

03

THE CITY OF STREET & FOODS

04

THE CITY OF SPORT

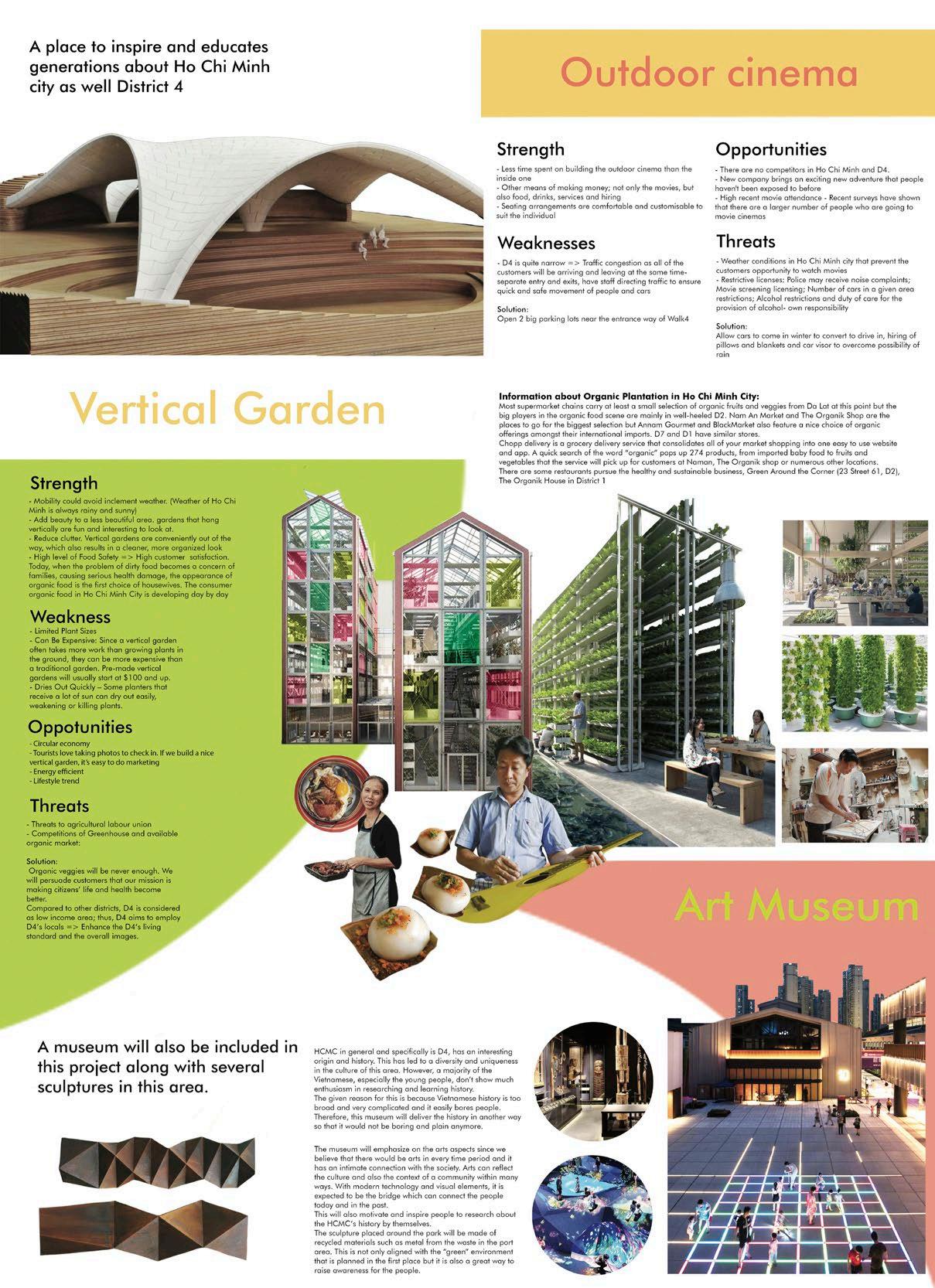

03. THE CITY OF STREETS & FOODS

No resident of, or visitor to, Ho Chi Minh City can ignore the remarkable variety and liveliness of its street life and street food. The city’s warm weather invites year-round occupation of street fronts and sidewalks for daily festive enjoyment of eating and drinking together. The City of Streets and Foods celebrates Vietnam’s formidable history cultivating food sources from land and water with the rich culinary arts that accompany that culture.

Dung Nguyen Han Nguyen

Thy Phan Van Anh Tran

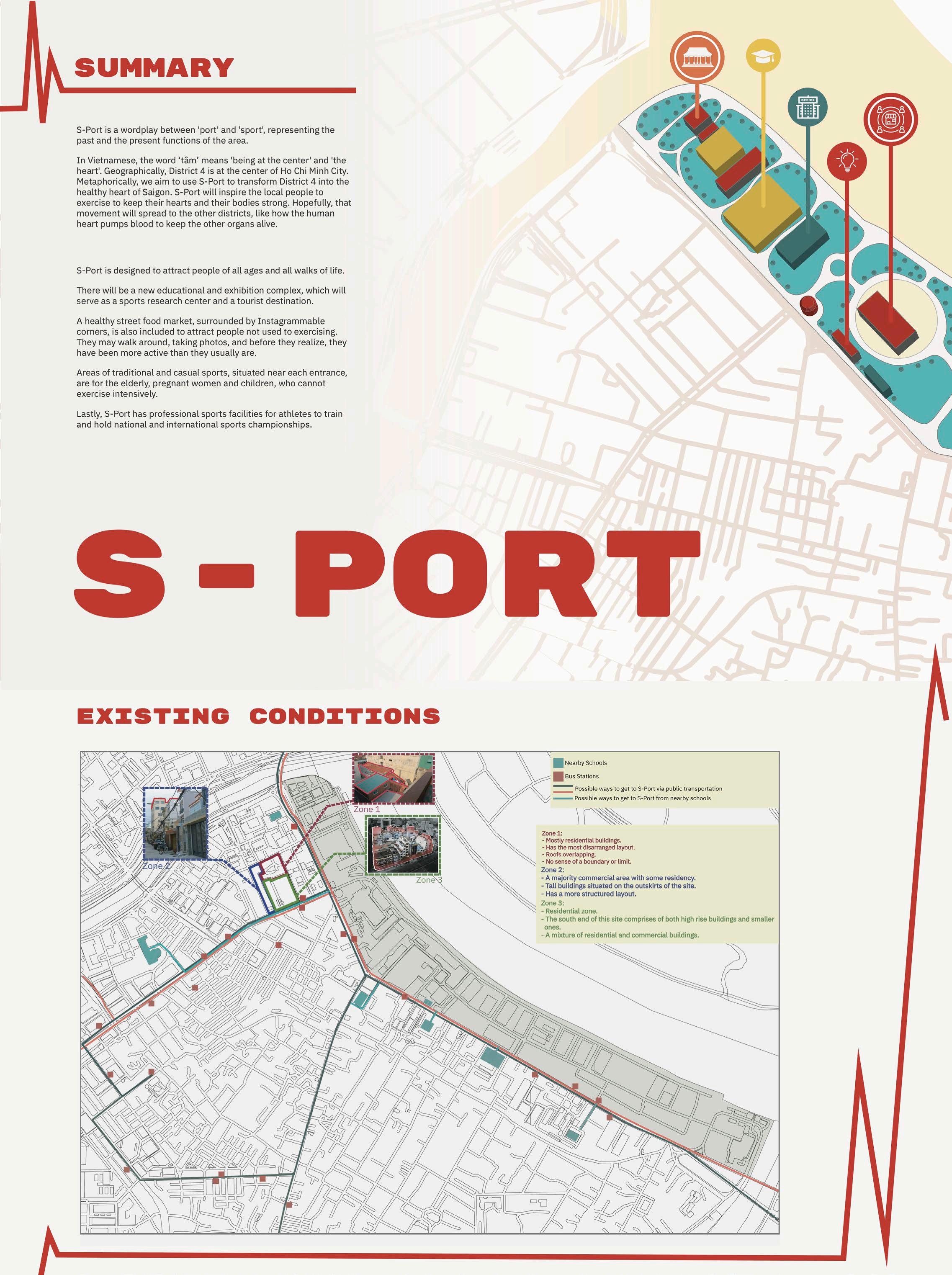

04. THE CITY OF SPORT

The Vietnamese people have lived and laboured out of doors for centuries. With an exceptionally young and increasingly prosperous population today, Ho Chi Minh City has become a city of outdoor sports and activities. From a formidable past built of lifetimes of physical effort to provide for basic goods, The City of Sport establishes a permanent urban theatre for healthy movement, casual encounter, and lively entertainment.

Trang Do Nguyen Vo Nguyen Dang Tran Luong

D. OUR CONCEPTS: SUSTAINING A SENSE OF PLACE

As District 4 becomes an increasingly attractive area for development, its heritage, informal and formal, and unique communal practices and traditions must not only be preserved, but nourished. In recent years, the area’s mafia-den reputation has faded from memory and interest in this area has renewed, with the most prominent discourses concentrating on its colourful local markets, thriving foodie scene, modern collaborative working spaces and vibrant locally operated cafes. We believe our proposed concepts for the District 4 waterfront area address the national strategy for the creative industries, contribute to the development of Ho Chi Minh City as one of Asia’s economic tiger cubs, and preserve formal and informal heritage. Most importantly, these concepts do so without sacrifice the district’s well-established sense of place.

Credit: unsplash.com Sandip Roy Place is among the most complicated words in the English language. Too often the word is used to designate the geographical location of an object or to identify where it belongs, such as with the phrase “it is in its proper place.” The term is also widely used to describe felt phenomenon, such as when someone utters “this is a remarkable place.” A cultural geographer named Tim Cresswell provides a broad, yet comprehensive interpretation of the term; for him, places are “locations imbued with meaning that are sites of everyday practice” (2009, p. 173).

With regards to the concepts proposed, this final interpretation of the word is the most suitable, as it accounts for the essence of place. Warranting consideration to everyday practices, even those considered mundane and marginal, enables us to witness how District 4, as a place, for a lack of a better term, happens, manifested by existentially binding practices (Malpas, 2006). Three interconnected considerations are needed to elucidate the notion of place as happening.

First, to eschew place as any fixed spatial point or feeling, it is beneficial to understand place much like the unveiling of a horizon, wherein a world temporarily gathers around an inhabitant. The use of the term horizon is vital, as a horizon exists in perpetual flux, always permitting new entities into its perceivable bounds, and therefore avoiding any stasis. Situate yourself as walking across Cau Mong, the colonial era pedestrian bridge connecting District 4 to District 1. As you enter the district and encounter various things, like hawkers selling handmade goods, cyclists riding on bike paths, children playing in parks, monks exiting a pagoda, or young folks sipping "Vietnamese milk coffee" in street side cafes, you may recognize how each collectively contributes to establish an atmosphere, and how your understanding of District 4, as a place, evolves as more things are permitted inside the horizon’s permeable boundary.

Second, each encounter with these things may manifest as an opportunity for meaningful engagement. As you walk, take note of how you are solicited by a range of possibilities – initiating a conversation, sitting for a coffee, or strolling through the park. As you move through the world and find yourself pulled by such opportunities, you are invited to distinguish how the things populating that enticing environment are not imbued with any inherent or stable character, but rather adopt their character and thus importance by way of their mutual constitution with the environment therein, and how they are stitched together by a referential nexus. A city park, for instance, may assume more meaning for you if capable of temporarily offering reprieve from Saigon’s unrelenting sun. In this instance, the park appears as instrumentally important. For the district’s residents, however, the park may be where they regularly meet to gossip or play games with comrades. This city park, if a recursive component of their daily life, has come to assume existential importance and is therefore critical for their self-realization (Wrathall, 2011).

Credit: unsplash.com Polina Rytova

The recognition of places imbued with existential importance, made clear by the solicitation of interconnected things, hints at the final point: the topology of place, which if broken down etymologically suggests “the saying of place.” This aspect of place speaks to an inhabitant’s acknowledgement and appreciation of how their own involvement, their motivation, pre-reflective responses to the solicitations of everyday life, allows for a sense of place to emerge, be nurtured, and shared amongst other inhabitants. David Seamon refers to these quotidian routines with familiar strangers as a place ballet, “an environmental synergy in which human and material parts unintentionally foster a larger whole with its own special rhythm and character” (Seamon, 1980, p. 163). The significance of such is the establishment of fellowship and belongingness to each other, sustained by everyday practices and routines. This interpretation of place is imbued within the presented proposals. These concepts sought to retain District 4’s formal and informal heritage, primarily through the preservation and refurbishment of built structures, and yet what seems to be best preserved is the district’s unique form of engagement, productivity, solidarity, and community – its sense of place. We recognize that the purest form of preservation, and consequently most authentic homage, is to foster new communally oriented, existentially important practices that support and nourish those already established. The City of Water, a concept celebrating the city’s aquatic heritage, providing opportunities for learning and leisure through a sustainable and economically advantageous approach, all while encouraging communal engagement. The variety of outdoor activities are especially pertinent to mention, as they grant spaces for people to interact in a variety of ways – physical activities, meditation, or play. The concept’s central square, designed to appeal to families and couples, offers an enriching space for people to congregate after work.

The City of Making, which aims to achieve accessibility, collaboration, conservation, inclusion, inspiration, and sustainability, provides opportunities for a variety of artisans, both modern and traditional, to develop and promote their talents in a supportive environment, one well suited to foster and sustain camaraderie amongst participants. Moreover, this concept is inclusive, as it's often about what constitutes a maker.

The City of Streets and Foods fosters communal engagement by way of collaborative farming and horticulture, as well as by ensuring the produce remains within the district. To better encourage that engagement, both from within and outside District 4, the concept proposes a pedestrian high line. This elevated walking path permits a fluid connection between internal and external stakeholders and the food-oriented

offerings embedded within the concept. Additionally, the outdoor cinema provides space for families, couples, and friends to congregate in the evening hours, thus guaranteeing clientele for the food grown and prepared on site.

The City of Sports is inspired by not only the UN sustainability goals, as articulated in the concept, but also the distinction that sports, as identified by Pierre de Coubertin, the father of the contemporary Olympics, permit the sharing of interests and values, the teaching of social skills, the overcoming of differences, and the opening of avenues for vulnerable and marginalized communities. This concept positions District 4 a place where people develop a healthy lifestyle and nurture a sense of belonging through physical activities.

Nurturing practices that foster meaningful engagement is critical for any city enduring rapid development and transformation. Too often these existentially-binding practices are disregarded, and consequently with them belonging, community, and ultimately a sense of place. The focus of this project, through the proposed concepts, is perfectly suited for implementation in District 4, as it aligns with the practices already embedded therein, and capable of uniting new performances, talents, and voices with those already flourishing. Finally, this approach, with its emphasis on community, can demonstrate Ho Chi Minh City’s progressive commitment towards urban regeneration, and thus be a model for future developments in the ASEAN region moving forward.

Credit: unsplash.com Daniel Bi

Disclaimer: The analysis of the site mentioned in this paper is based on the public available information which might not be updated and partially in contrast with other documents that we have not been able to review at the time the paper is published