4 minute read

DID YOU KNOW ...

... The Flow of the Rio Grande is Only 20% of its Pre-1900 Levels?

by the CHAPS Program Team at UTRGV

The Río Grande has shaped the landscape of the Rio Grande Valley for millions of years, playing both constructive and destructive roles in its formation. In the last few million years, the river has evolved from a raging river into its current style—a slow, meandering waterway that winds through its broad floodplain. Below Falcon Dam, the river flows over bedrock, following a south-to-southeast direction. Near Roma, the river sharply veers eastward toward the Gulf of Mexico, a journey of 190 km (120 miles) as the crow flies. Over this distance, it becomes a meandering river with a channel length of 420 kilometers (260 miles).

THE RIO GRANDE IS A MEANDERING RIVER

Meandering rivers are among the most dynamic and visually striking features of fluvial landscapes. From Roma, elevation 50 m above sea level, to its mouth on the Gulf of Mexico, the Rio Grande transitions into a meandering river due to its very low gradient, only 12 cm (5 inches) per kilometer between Roma and the Gulf.

In its natural state, pre-1900, river flow was irregular but had spring and summer river risings sufficient to support riverboat navigation from Brownsville to Roma. However, in the 1890s and thereafter, New Mexico and Colorado irrigation projects appropriated the upper river’s base flow, and only occasional flood waters passed into its lower reaches. The construction of eight large dams on the Rio Grande and its main tributaries, including Elephant Butte Dam 1916, American Diversion Dam 1938, Falcon Dam 1954, Amistad Dam 1968, etc., further decreased water flow, reducing it today to just 20% of pre-1900 levels.

THE RIO GRANDE BECAME THE INTERNATIONAL BORDER IN 1848

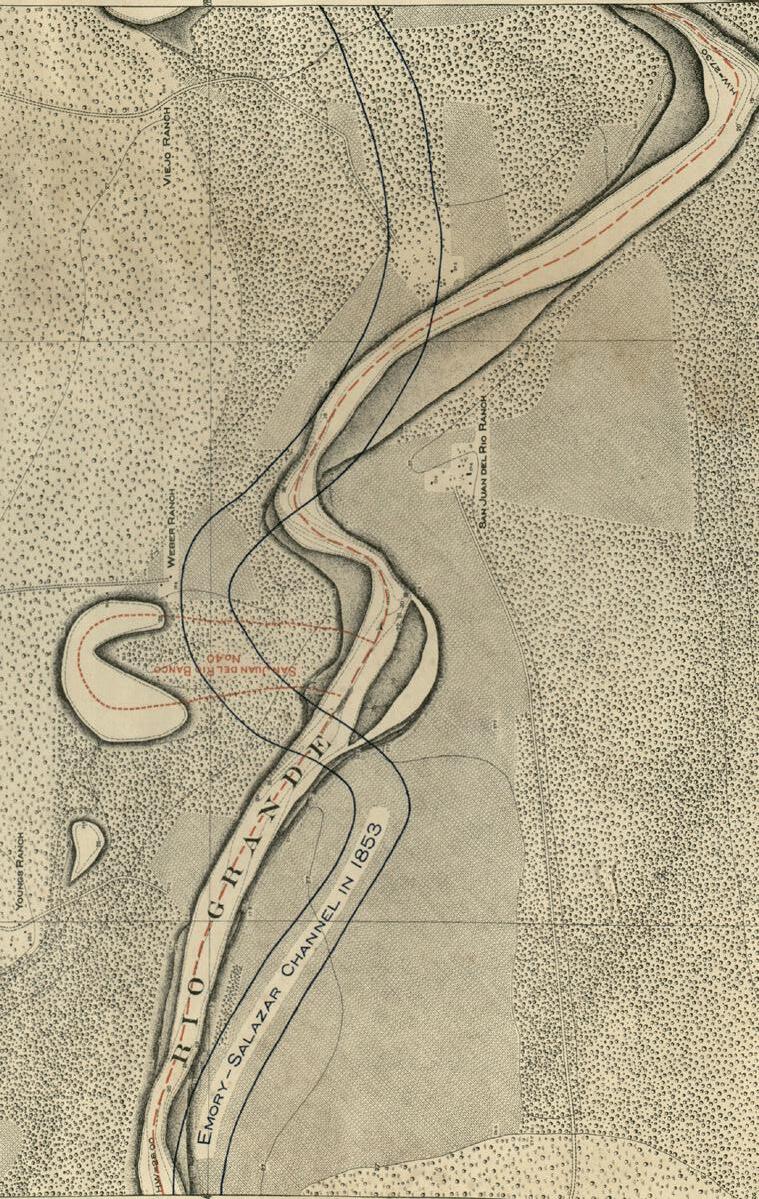

The Rio Grande was designated as the international border under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. Government commissioners William Hemsley Emory from the United States and José Salazar y Ilarregui from Mexico conducted a joint survey of the river’s 1,200-mile stretch between Texas and Mexico to formalize this boundary. By 1853, the survey established the river’s center as the official international boundary, referring to it as the Emory-Salazar Channel.

However, the border was highly dynamic due to the nature of the Rio Grande’s alluvial delta. Storms and hurricanes caused the river to meander, creating resacas and oxbow lakes and altering the channel, shifting the physical border. In 1884, an international treaty acknowledged these natural changes, and in 1889, the International Boundary Commission was established to implement the treaty and manage boundary disputes caused by the river’s shifting course.

STEAMBOATS ALONG THE RIO GRANDE

During the Mexican-American War, steamboat captains and entrepreneurs like Richard King and Mifflin Kenedy operated steamboats along the Rio Grande. Operating as conduits for the US Army, a trip on a steamboat from the mouth of the Rio Grande to Camargo took six days to travel over the shallow, sinuous river. The US Army launched more than forty-two steamboats to operate on the Rio Grande between Brazos Santiago and Camargo. Only one steamboat, the Major Brown, made it all the way upriver to Laredo.

As we see the struggles occurring along the Rio Grande with regard to water flow, or lack thereof, it is important to see how human-land interaction has played a role in not only the shifting river but in how the reduced volume and force of flow will affect our lives and livelihoods in the very near future.

Ancient Landscapes of South Texas – The Rio GrandeUTRGV’s CHAPS Program