The Possibility of Good News

Cover: Lucinda Coxon speaking at the One Life event, June 2024. Photo: Oxford Atelier

Editorial: Matt Phipps Design: Laura Hart

Principal’s Message

My predecessor Daphne Park, the so-called ‘Queen of Spies’, famously once listed her hobbies as ‘good talk and difficult places’.

The story goes that it was chancing on this memorable line in Who’s Who that led Somerville’s Governing Body to approach the former MI6 Station Chief about becoming Principal. Here, they told themselves, was someone up to the challenge of steering College through the choppy waters of 1980s higher education.

And yet, is this fondness for ‘good talk and difficult places’ really anything more than an expression of a quintessentially Somervillian attitude? From our College’s earliest days, circumstances dictated that the women who came here were not only intrepid, but keenly aware of both the pleasures and inherent power of good conversation.

In this year’s Magazine, you will see how Somervillians of all ages, backgrounds and beliefs retain that same appetite for ‘good talk and difficult places’. Better still, you will learn how these qualities are enabling our academics, students and alumni to leverage real change across three of the most pressing issues of the day – AI, sustainability and sanctuary.

On AI, we are joined by our Professorial Fellow Steve Roberts and early career academic Dr Yvonne Lu as they discuss the ethical dangers and limitless possibilities of machine learning.

On sustainability, we hear from our alumna Claire Wansbury about the potential of blue-green infrastructure, while Professor Radhika Khosla, Research Director of the Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development (based at Somerville), shares her latest thoughts on how we can – and must – prepare for extreme heat in the UK.

Finally, we are proud to share a series of features encapsulating our past, present and future as a college of sanctuary for displaced scholars. We start with two stories exploring

Somerville’s unsung connection to the kindertransports of the 1930s, including a reflection from Somervillian screenwriter Lucinda Coxon on her experience retelling this story in the recent film One Life.

We also look to our future as a College of Sanctuary by sharing the hopes and dreams of Syrian academic Dr Ammar Azzouz and the captivating research of Oxford EAA Qatar Sanctuary Scholar Muhammed Zeyn.

Given that 2024 marks thirty years since Somerville went mixed, it is also right that we reflect on this momentous event. Helping us we have Sian Thomas Marshall and Dan Mobley, two Somervillians who straddled the divide.

The coming year will be my last as Principal of Somerville. Naturally, I feel regret to be leaving such an inspirational environment. But I also feel immense gratitude and pride. To have been welcomed so warmly, to have spent seven years surrounded by such excellent colleagues and, most of all, to contribute to the continuing legacy of this proud institution is one of the inestimable privileges of my life.

On the evidence here, I have no doubt that the coming year and many more thereafter will be just as fascinating, and just as filled with hope and positive action. They will also be defined by another quality Daphne Park once gave as distinctly Somervillian.

More than courage, she said, more than intellectual curiosity and the desire for excellence, Somervillians possess an abiding belief in the decency of human beings. Long may that continue.

Jan Royall, Principal

News and People

NEWS

The Somerville College Choir toured India in December, performing British Christmas music and working with local charities.

The College marked Refugee Week with a special screening of One Life (2023) featuring a Q&A with the film’s director and screenwriter, and a relative of one of its protagonists (see pp20-23).

FELLOWS AND STAFF

In the New Year’s Honours, our Senior Associate Alexandra Vincent, COO of Oxford’s Humanities Division, was made an MBE for her services to research funding.

In the King’s Birthday Honours, our Senior Research Fellow Professor Rajesh Thakker was made an OBE for services to Medical Science and to People with Hereditary and Rare Disorders.

Professor Colin Phillips, the newly appointed Professor of Linguistics at the University of Oxford, joined Somerville as a Professorial Fellow.

Professor Radhika Khosla, Research Director of the OICSD, received an honourable mention in the Bina Agarwal Prize for Young Scholars in Ecological Economics (see pp12-13).

Our Special Associate and alumna Jane Robinson (1978, English) published Trailblazer, which tells the story of Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (see p33).

Our Tutorial Fellow in Engineering, Professor Noa Zilberman, received an MPLS Teaching Award for Outstanding Research Supervision, and was made a Fellow of the Alan Turing Institute.

In the Vice-Chancellor’s Awards, Dr Claire Cockcroft was shortlisted in the Support for Students category for her work with Somerville Skills Hub, while Dr Shobhana Nagraj, Somerville’s former Junior Research Fellow, received a Highly Commended Community Partnership Award for her team’s campaign tackling child food poverty in Oxfordshire.

Our Tutorial Fellow, Professor Fiona Stafford FBA, published Time and Tide: The Long, Long Life of Landscape (see pp28-29).

Professor Julie Dickson was awarded the Alice Tay Book Prize for Excellence in Legal Theory for her book, Elucidating Law (Oxford University Press, 2022).

CFO of the Bank of England, Afua Kyei (2000, MChem), and centenarian codebreaker Patricia Davies (née Owtram, 1951, BLitt English) were both elected Honorary Fellows of Somerville. Friend of the College, Sir Simon Russell Beale also received an Honorary Fellowship.

ALUMNI

In the New Year’s Honours, Honorary Fellow Professor Julia Yeomans (1973, Physics) was made an OBE for services to Physics; Professor Ann Prentice (1970, Chemistry) was made a CBE for services to British and global public health nutrition; Theresa Wise (1983, Lit Hum) was made an MBE for services to Broadcasting; and Jane Toogood (1983, Chemistry) was made an OBE for services to the low Carbon Hydrogen Sector.

In the King’s Birthday Honours, Professor Alison Wolf (1967, PPE) was made a DBE for services to education, and Lady Suzanne Heywood (1987, Zoology) was made a CBE for services to Business Leadership. Phillida Strachan (2013, MSt Refugee and Forced Migration Studies) was made an OBE for services to International Development, and Susie Dent (1983, Modern Languages) was made an MBE for services to Literature and to Language.

Luca Webb (2019, History), Councillor for Chepping Wycombe Parish Council in Buckinghamshire, was shortlisted for Young Councillor of the Year.

Professor Shân Wareing (1984, English) was appointed the new Vice-Chancellor of Middlesex University.

Professor Caroline Derry (1990, Jurisprudence) was appointed Professor of Feminism, Law and Society at The Open University.

STUDENTS

Final year medic Josephine Carnegie (2018, Medicine) was awarded the Ledingham Prize for Best Performance in Medicine for the clinical finals.

Harry Ledgerwood and Grace Copeland (both 2022, MSt Creative Writing) were shortlisted for the Jon Stallworthy Poetry Prize.

Maitha Al Shimmari (2020, DPhil Engineering) was selected by the Oxford Bodleian Radcliffe Science Library’s EDI Portrait Project which celebrates outstanding contributions of staff or students who promote equality, diversity, and inclusion through their work.

Sawsan El-Zahr (2022, DPhil Engineering) won first place in the Dyson Sustainability Award at this year’s STEM for Britain competition and won the Internet Research Task Force’s Applied Networking Research Prize (ANRP) 2024 (see p9).

Jo Rich (2021, English) performed in The Two Gentlemen of Verona at the Oxford Playhouse, directed by Gregory Doran, former Artistic Director of the RSC (see p26).

Somerville College Cricket Club broke their losing streak with a triumphant win against Worcester College.

Professor Colin Phillips at his inuaugural lecture with Principal Jan Royall and Vice-Chancellor Professor Irene Tracey

Somerville College Choir in India

Somerville’s Commemoration 2024

Somerville’s Commemoration Service this year was held on Saturday 8th June in the College Chapel.

This important event in our calendar underlines the enduring relationship between Somerville and its members, as we commemorate our founders, governors and major benefactors, and especially alumni who have died during the past year. The address was given this year by Dr Jackie Watson, Co-Secretary of the Somerville Association, and the Service can be watched again on the Somerville College YouTube channel.

All Somervillians are welcome to attend this annual Service and we particularly invite close families and Somervillian friends of those who have died to join us. Next year’s Commemoration will take place on 14th June 2025 in the College Chapel.

If you know of any Somervillians who have died recently but who are not listed here, please contact commemoration@some.ox.ac.uk.

Valentine Harriet Isobel Dione ArnoldForster née Mitchison (1948) on 27 May 2023, aged 92, Jurisprudence

Katherine Margaret (Katy) Barratt (1970) on 20 August 2023, aged 70, Mathematics

Margaret Shepherd Barrett née Bacon (1946) on 1 June 2023, aged 95, Medicine

Julia Mary Ursula (Jo) Barstow née Dunn (1955) on 9 April 2024, aged 87, Modern Languages

Susan Elizabeth Bevan (1960) on 8 January 2024, aged 81, Politics, Philosophy and Economics

Pauline Mary Blackman née Taylor (1956) on 5 February 2024, aged 86, Mathematics

Jill Elizabeth Sebert Brock née Lewis (1956), Medicine

Barbara Scott Cairns (1951) on 8 November 2023, aged 90, Mathematics

Christian Agnes Kirkwood Carritt (1946) on 5 July 2023, aged 96, Physiological Sciences

Nora Catharine Cleaver née Marsden (1948) on 13 March 2023, aged 93, Modern Languages

Elizabeth Frances Mary (Liz) Cooke née Greenwood (1964) on 17 August 2023, aged 78, History

Margery Patricia Mary (Patricia) Drinkall née Ellis (1949) on 8 January 2023, aged 93, Modern Languages

Margaret Claire (Maggie) Eisner (1965) on 19 May 2023, aged 75, Psychology, Philosophy and Physiology

Dorothy Mary Evans née White (1963) on 27 June 2023, aged 77, Mathematics

Melanie Jane Florence (1981) on 18 September 2023, aged 60, BA and MPhil Modern Languages

Linden Kuen-Chuan Foo (1960) on 18 March 2022, aged 80, Physiological Sciences

Jean Mary Forshaw née Carpenter (1948) on 27 March 2024, aged 94, History

Penelope Margaret Gaine née Dornan (1959) on 25 February 2024, aged 84, English Language and Literature

Elizabeth Ann (Ann) Gray (1953) on 13 October 2023, aged 89, English Language and Literature

Jennifer Mary (Jenny) Gregson née Hope Simpson (1957) on 15 March 2023, aged 84, Mathematics

Sylvia Nancy Gyde née Clayton (1954) on 23 April 2024, aged 87, Physiological Sciences

Joan Hampshire (1947) on 22 December 2023, aged 94, English Language and Literature

Rosemary Hobsbaum née Phillips (1955) on 29 June 2023, aged 86, English Language and Literature

Cynthia Mabel Howard (1951) on 30 September 2023, aged 91, Modern Languages

Sarah Caroline Le Messurier (Sally) Humphreys née Hinchliff (1953) on 26 February 2024, aged 89, Literae Humaniores

Helen Elizabeth Jones (1969) on 17 December 2022, aged 71, Modern Languages and History

Martha Klein née Bein (1980) on 9 March 2024, aged 82, BPhil Philosophy

Ruth Lister (1944) on 27 August 2023, aged 97, Medicine

Helen Mawson née Fuller (1957) on 19 June 2023, aged 85, Literae Humaniores

Elizabeth Kathleen (Lizzie) McLean née Hunter (1950) on 4 August 2023, aged 91, Physiological Sciences

Hilary Marion Olwen Nightingale née Jones (1948) on 23 January 2022, aged 91, English Language and Literature

Joan Emilie (Joey/Joanie) Philpott née Huckett (1943) on 11 Nov 2022, aged 97, English Language and Literature

Ann Mary Alice Raynes (1951) in 2022, aged 90, Politics, Philosophy and Economics

Vivienne June Cassandra Rees née Farey (1951) on 4 February, 2024, aged 92 History

Cynthea Rhodes née Woffenden (1956) on 13 September 2023, aged 86, Modern Languages

Jane Hippisley Robinson née Packham (1959) in 2024, aged 81, Chemistry

Constanza Romanelli (1948) on 25 May 2023, aged 94, Literae Humaniores

Helen Mary Sackett née Phillips (1948) on 28 March 2023, aged 93, Physics

Ann Acheson Schlee née Cumming (1952) on 1 November 2023, aged 89, English Language and Literature

Patricia Molly (Molly) Scopes née Bryant (1954) on 31 December 2023, aged 88, Chemistry

Caroline Seebohm (1958) on 22 July 2023, aged 82, Jurisprudence

Jane Margaret Sik née Woodland (1965) in Dec 2023, aged 77, Physics

Sandra Pauline Skemp née Burns (1957) on 24 January 2024, aged 85, Jurisprudence

Susan Stokes née Bretherton (1952) on 6 January 2024, aged 89, Modern Languages

Rachel Sheila Cooper Sykes (1943) on 2 Oct 2023, aged 99, English Language and Literature

Urszula Stefania Szulakowska (1970) on 21 July 2023, aged 72, History

Phyllis Margaret Treitel née Cook (1948) on 1 May 2024, aged 94, PPE

Hazel Claire Thomas (1973) on 29 December 2023, aged 69, History

Diana Mary Welding née Panting (1949) on 20 October 2023, aged 92, Modern Languages

Elizabeth Mally (Mally) Yates née Shaw (1949) on 25 June 2023, aged 92, Mathematics

AI: The Good, the Bad and the Beautiful

Stephen Roberts is the Man Professor of Machine Learning in Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science and a Professorial Fellow of Somerville. A thought leader in machine learning, his research focuses on the real-world applications and benefits of advanced theory.

Only ten years ago, the things AI does now would have seemed like magic to most of us. Travelling overseas, we can point our phones at a menu and get an instant translation. Want a poem about your cat? Just ask Chat GPT. The technology may still be a little brittle, but algorithms are already helping to make decisions that affect our lives: the question of whether I get a credit card, for example, or even whether I get interviewed for a job. Read the headlines, however, and you’d be forgiven for thinking AI is the enemy. If it isn’t making our SatNavs drive us into rivers, it’s certainly coming for our jobs.

So, how worried should we be? Well, AI can seem miraculous, but we should always remember, it’s maths, not magic. Most AI in the world around us has been

trained using the data that we give it. That means it’s largely a reflection of us. The real risk, therefore, is not that the machines are coming to get us, but that we might train AI to replicate our worst selves. Certainly, the use of AI is already outstripping legislation and policy and leading to societal changes. Move over Gen Z… It’s time to meet Gen AI.

Generation AI

One of the most prominent forms of AI impacting our lives today are Large Language Models (LLMs). These are programmes that can comprehend and then generate human language, as well as images, audio and software – to name but a few extras. They work by absorbing and processing huge amounts of existing text, and are so energyhungry that only megacorporations like

The

Meta AI will ingest all recorded knowledge from 5,000 years of human civilisation.

OpenAI, MicroSoft, Meta and Google can afford to train them and run them constantly. Annually, they cost more than the GDP of many of the world’s nations. Yet these LLMs often lack transparency. The workings of the new Meta AI, for instance, are a closely guarded secret: this is a profit-hungry commercial operation, after all. We do know, however, that Meta AI contains 400bn ‘tokens’ (the fundamental units of data processed by algorithms), compared to the average

Main image: Kepler 186f, one of the exoplanets discovered through Steve’s algorithms with an earth-like profile - ‘my retirement planet’

of 70bn tokens used by most LLMs and the modest 7bn used by Yvonne Lu’s medical tracking model (which you can read about in the next article). That means Meta AI will shortly ingest all recorded knowledge from 5,000 years of human civilisation. Potentially, that’s a great thing. But done wrong, it could generate false information and confirm the monocultural biases of those currently in charge.

AI for good?

Mitigating these risks is where academic researchers come into their own. AI’s processes are the same ones scientists have always used to make sense of the world. In an academic space, philosophers and scientists can consider the ethics and realities of AI together. Evidencebased arguments can percolate upwards from universities towards government and policymakers. If we get the ethics and the science right, using what I call ‘honest and humble’ algorithms, rooted in trusted evidence, the benefits could be world-changing. Let’s take just two examples: the first from health; the second from astrophysics.

Case Study 1: The Humbug Project

Mosquitoes are notoriously dangerous, responsible for around a million deaths each year. Malaria alone kills more than 400,000 people each year, and viruses carried by mosquitoes –yellow fever, dengue and zika – are increasingly impacting human health. So, what if we could capture the sound of mosquitoes as they try and bite people in their homes? I’m fortunate to be Co-Principal Investigator on Oxford’s HumBug Project, where we’re using an algorithm pipeline to detect and identify different species of mosquitoes from the sounds they make when flying. An app can be installed on budget smartphones, capturing the information for HumBug’s AI to classify, helping to create valuable insight for disease understanding and prevention.

Case Study 2: Deciphering the Stars

The same sort of algorithm pipeline is used for ‘big science’ projects. In astronomy, advances in the technology of observational instruments have given us overwhelmingly vast amounts of data. Analysing it the old way would take humans millions of years. AI can supercharge this process, looking at tetrabytes of data every second. Already, the results have helped us discover habitable planets, observe the microscopic changes that prove the existence of gravitational waves, and even watch as two black holes spiralled around each other.

To conclude, science is already changing with the rise of AI and the era of the algorithm. What matters now is how we choose to use this new intelligence.

If we embrace AI, while staying fiercely vigilant, there is hope it can help us. From increasing crop yield in famine-prone areas to making better medical diagnoses, intelligent algorithms can bring solutions that will change and save lives.

As Dennis Gabor said, “We cannot predict the future, but we can engineer it.”

What matters now is how we choose to use this new intelligence

Professor Roberts filming a lecture for Somerville College, April 2024

Left: The Humbug Project: Participants in the Randomised Controlled Trial in Tanzania.

Right:

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, formerly known as WFIRST, an upcoming space telescope designed to perform wide-field imaging and spectroscopy of the infrared sky. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space

Democratising AI for Women’s Health

Dr Huiqi Yvonne Lu is a health informatics machine learning research fellow at the Department of Engineering Science and a former Junior Research Fellow at Somerville College. Her most recent project looks at the feasibility of using Large Language Models to build healthcare capacity in rural India, thereby reducing health disparities during pregnancy.

It’s reasonable for us to be concerned about AI. But, as an engineer, I believe AI can be a resource for societal good like water or electricity, if channelled correctly.

A good example of this lifesaving potential is the project I recently worked on to train Large Language Models in supporting rural health workers in India, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Global Challenge Program and The George Institute for Global Health.

The problem we faced is that, in the rural Indian states of Telengana and Haryana, a handful of healthcare workers have to travel among hundreds of villages to deliver obstetric care to the women there. Without professional training and hopelessly overstretched, the margin for severe and often fatal error is huge.

We designed the SMARThealth GPT system alongside end users in rural India to offer a chatbot expert that could mitigate these difficulties. Our first phase of system development had two stages. First, we developed and refined our proprietary SMARThealth GPT, building on its reasoning-informed methods. Next, we applied for ethical approval and launched the SMARThealth GPT in India.

of super-user field-testing. This gave the ASHAs access to a whole encyclopaedia of purpose-built medical knowledge, with additional translation features so patient advice could be communicated in the different dialects used in the region.

This first phase went well, and we recently published a research paper reporting our findings at the NeurIPS 2023 Conference.

For the next phase, we plan to combine quantitative analysis of the GPT’s responses in the field with qualitative analysis of survey responses from our eight health workers. Using this data, we’ll refine the prompt designs and add memory and instruction learning. Our goal is to make each new version of the SMARThealth GPT more accurate and more inclusive, until we can close entirely the gap between a clinician’s recommended response and the response given in the field.

The positive effects of AI are limited only by our imagination.

Eight healthcare workers, called ASHAs, were given access to the Smarthealth GPT app and carried out three rounds

From here, we plan to scale this app for use in other countries and continents, supported by The George Institute for Global Health network. Excitingly, this concept could also be spun out for use in different forms of healthcare beyond women’s health.

As with every new technology, the positive effects of AI are limited only by our imagination. My own promise is that I will always apply AI responsibly, building innovations that improve health and equality for all.

The Smarthealth GPT app in use in 2024. Credit: The George Institute for Global Health

GREENING THE INTERNET: Sawsan El-Zahr wins first place in the Dyson Sustainability Award at STEM for Britain

‘Let me just Google that.’ Our response to any query in this day and age is to look it up online –but at what cost, and what can be done about it? This is what Somerville DPhil student and Oxford Qatar Thatcher Scholar Sawsan El-Zahr has been investigating. Her research focuses on reducing the carbon footprint of the internet, examining how carbon-aware routing strategies can drastically reduce emissions.

Sawsan initially explored the difference between energyefficiency and carbon-efficiency of energy routing. Using this data, she then designed a Carbon-Aware Traffic Engineering solution. This will enable Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to reroute their traffic flows efficiently through greener paths.

The project offers huge potential benefits: ISPs will be able to reduce emissions without incurring additional costs, while everyday users will be able to compare and select the most environmentally friendly ISP.

Using Sawsan’s research, policy-makers could also make more informed recommendations on ‘greening’ the internet. With net zero emissions as the UK’s current goal for 2050, this research is extremely relevant and valuable.

The importance of Sawsan’s work has been recognised across the board. Her work has won the Applied Networking Research Prize 2024, been commended as some of the most exciting research in the field by the Internet Research Task Force (IRTF), and has now won first place in the Dyson Sustainability Award at this year’s STEM for Britain competition.

STEM for Britain invites the UK’s foremost early-career researchers to discuss their research with Members from both Houses of Parliament. The event offers entrants a rare opportunity to learn how their research could translate into policy.

Making the Internet sustainable is essential, especially with the growing use of AI

Speaking about her win, Sawsan said, ‘I was so honoured to participate in STEM for Britain and win the first prize, and I hope that the discussions we had about sustainability can impact policy making. I also remember with gratitude that this research would not be possible without the support I have received here at Oxford and especially at Somerville.’

Sawsan’s supervisor, our Tutorial Fellow in Engineering, Prof Noa Zilberman, added: ‘Making the Internet sustainable is essential, especially with the growing use of AI, cloud computing and video streaming. Sawsan’s research is an important step towards a more sustainable Internet, and I am excited to see her work recognised by such an esteemed award.’

Sawsan alongside her fellow winners and competition judges in the Houses of Parliament

INSIDE THE BLUE-GREEN REVOLUTION:

Protecting Our Communities Against Climate Change and Biodiversity Loss

Claire Wansbury FCIEEM (1988, Pure and Applied Biology) is Technical Director at the global engineering firm AtkinsRéalis and the recipient of numerous awards for championing sustainability, including the Society of the Environment’s Environmental Professional of the Year. Here she introduces the concept of blue-green infrastructure and how to embed its lessons in our daily lives.

We are living through a time of intertwined global emergencies of climate change and biodiversity loss. The sheer scale of this complex of challenges can be so daunting we feel it is surely too big for our efforts to make a difference. Some reach the point of suffering eco-anxiety, as fear for the future of our living planet becomes overwhelming.

I am fortunate that my environmental career in the engineering sector has shown me that there is still plenty of scope for us to make a positive contribution, both as individuals and communities. In this feature I share one contribution I made through a recent publication, and some simple ideas on things we can all do to make a difference.

What Is Blue-Green Infrastructure?

Traditionally, when engineering designers have an issue to solve, like flood risk, the automatic choice is ‘Grey Infrastructure’ such as a sea wall. But what if there were an alternative?

Blue-Green Infrastructure (BGI) is the managed network of terrestrial and water habitats found across our urban and rural

landscapes. From green bridges to living roofs, BGI provides a toolbox of methods to improve biodiversity, mitigate extreme heat in our cities and find alternatives to traditional grey infrastructure.

Returning to our flood risk example, then, a BGI response to this issue might be a wetland. This solution could be introduced either instead of or alongside the flood wall to provide a range of additional benefits, such as water purification, carbon capture and local community wellbeing.

Co-editors Dr Carla-Leanne Washbourne and Claire Wansbury with the ICE Manual of BlueGreen Infrastructure

The ICE Manual of Blue-Green Infrastructure

My co-editor Dr Carla-Leanne Washbourne and I were very proud last year (2023) to publish The Institute of Civil Engineers’ Manual of Blue-Green Infrastructure.

Featuring contributions from over 50 world-leading experts, the ICE Manual of Blue-Green Infrastructure will enable engineers and other designers to integrate BGI into their future work. We hope it will also meet the growing appetite from clients to integrate BGI into their projects, and universities to incorporate BGI into their courses.

What You Can Do

I’m fortunate that I can make a difference through my work. But we can all make a contribution in the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss. I suggest you explore opportunities under three headings: learn, act and speak out.

1. Learn

In every company and every country, we need to understand our impacts, risks

and dependencies on nature. We also need to upskill everyone, so we have climate and nature literacy across all decisionmakers and throughout workforces. If you work in a company, it is very likely that exploring the supply chain will reveal both impacts and dependencies on nature, and with those dependencies there are risks to the business if we do not protect the natural world. For organisations, a good start would be investigating the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures.

As an individual, I would suggest a really good read to start is Tony Juniper’s book What Has Nature Ever Done for Us? Also, I would always encourage joining your local nature organisation.

2. Act

Research and reporting on risks isn’t enough unless it is accompanied by action. For companies, you can find inspiration in sources such as the Nature Positive Initiative, Business for Nature and Nature On The Board. For individuals, one action that is really important is to engage with and enjoy nature. Engaging with our natural world helps us understand what we are fighting for, and it also helps with our physical and mental wellbeing.

Engaging with our natural world helps us understand what we are fighting for.

3. Speak Out

It’s great when organisations like the UN and World Wide Fund for Nature make the point that protecting and restoring biodiversity is good business sense. But the power of that message is only truly unleashed when it also comes from the business community. I was delighted last year when the company where I work, AtkinsRéalis (previously SNC Lavalin), signed the Business for Nature ‘Make It Mandatory’ statement, calling on global governments to make firm commitments to deliver a nature positive future. Other businesses can and should follow.

For individuals, a great way to advocate for nature is by joining your local wildlife trust. I am aware that this is not practical for everyone during a cost-of-living crisis. So it’s worth noting that many of these organisations have free mailing lists which you can sign up to for inspiring stories and campaigns to support.

Hopefully, following one or more of these steps will make you feel that you are no longer one person, one voice calling for change. Together, we can be heard.

The ICE Manual of Blue-Green Infrastructure is available now.

The UK’s first heathland green bridge, which is currently under construction and features in the Manual. Credit: National Highways and AtkinsRéalis Ltd

Keeping People Safe in an Ever Hotter United Kingdom

Dr Radhika Khosla is Associate Professor at the Smith School of Enterprise and Environment and Research Director of the Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development at Somerville. She advises the House of Commons on heat resilience and sustainable cooling, and here shares actions governments and businesses should be taking to adapt to rising temperatures.

TIt is time to take the threat of extreme heat seriously.

he world is getting hotter and heatwaves are becoming more frequent and more severe. Recent projections say 2024 is set to be the warmest year yet. As the summer of 2022 demonstrated, despite its reputation for cold and rain, the UK is not immune from bouts of extremely hot weather.

It’s unfortunate that, perhaps due to our cultural fixation with sunny holidays, we can’t help but view hot weather as a blessing. Extreme heatwaves are all too often covered in the media by pictures of people on the beach or enjoying ice creams. But the lived experiences of heat tell a different story, with significant damage to health and productivity.

As the science shows us, extreme heat has important implications for worker safety.

Extreme overheating has serious health risks. In many cases, these include heart attacks and strokes, especially among high-risk groups like the elderly (above 65), the newborn, and outdoor workers. Extreme temperatures also impair cognitive performance and are associated with increased risk of mental illness. Heat and mortality are also significantly linked: during the 2022 UK heatwaves, 2,985 excess deaths were recorded.

Given the clear safety risk that heat presents, particularly to those working and spending time outdoors, steps must be taken for safety during hot weather. Chief among them is staying out of the midday sun – hot countries such as Spain have long adapted to high temperatures by taking a 2-3 hour break in the afternoon when the heat is at its peak. Practices like this might feel disruptive at first, but are essential to reducing heat-related risks. When working in the sun is unavoidable, workers must have access to appropriate clothing, sunscreen and water, ventilation, and be encouraged to take regular breaks in the shade, or ideally a dedicated cooling area.

For indoor workers, the risks presented by extreme heat will depend largely on their access to cooler spaces and cooling systems. Ventilation, air circulation and shading are key. Research shows how measures such as awnings and window shutters can significantly reduce internal temperatures, while ceiling fans can reduce the burden on air conditioning

systems. Very few schools and hospitals in the UK have ceiling fans – this represents an obvious and relatively affordable way to adapt to the coming heat. Trees and vegetation are also proven to significantly reduce internal temperatures when allowed to grow around buildings.

As temperatures rise, the go-to solution is often air conditioning. Indeed, air conditioning already consumes 20% of all electricity on the planet and demand for air conditioners is expected to triple by 2050. This is extremely concerning, especially as our electricity system continues to rely on fossil fuels. Commonly used air conditioners emit climate-damaging gasses and drain large amounts of electricity. Their use leads to increased greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating climate change and resulting in more extreme heat events (which in turn propel demand for air conditioning). A vicious cycle forms, whereby high energy consumption makes people cooler inside, while making the world outside even hotter.

My colleagues and I at the Oxford Martin Future of Cooling Programme have written at length about approaches to sustainable cooling and finding ways to reduce the impact of air conditioners on our planet. The key recommendations are to improve shading, ventilation and circulation within and outside our buildings, while making air conditioners themselves more efficient and sustainable.

As temperatures around the world continue to rise, it is vital that we are prepared to act and build resilience to extreme heat. Heat Action Plans provide one such strategy, and their effectiveness relies on the ability to coordinate action across different parts of government and civil society. Heat Action Plans set out various steps in the event of a heatwave,

including early warnings and mitigation of impact during and after the heatwave itself. This is an effective practice that workplace safety managers can follow, too – having a good plan in place is a great way to reduce the risk that extreme heat represents. In the UK, the Heat-Health Alert Service and Adverse Weather and Health Plan help provide some of these tools.

It is time to take the threat of extreme heat seriously. Our recent study showed how the UK was ‘dangerously under prepared’ for the rising temperatures we face if the world misses its climate targets. Until the Government creates a National Heat Resilience and Sustainable Cooling Strategy, it’s up to organisations, communities and individuals to take the lead in protecting people in an increasingly hot UK.

A version of this article was previously published in Safety Management, the magazine of the British Safety Council.

Ventilation, air circulation and shading are key.

Below: Innovative approaches to sustainable cooling from outside the UK - wind-catcher towers in Yazd, Iran

30 YEARS of Going Mixed

2024 marks 30 years since Somerville College admitted its first male students, a decision that sent shockwaves through the community. But what was lost, and what was gained? We asked two Somervillians from either side of this seismic shift for their thoughts.

SIAN THOMAS MARSHALL (1989, Biology) is the founder of U Pilates, and was a leader of the “Somerville Says NO” campaign which petitioned College regarding its decision to admit male students.

In 1992, we felt pretty good about ourselves. Somerville debaters were dominating the Union. Somerville rowers were Head of the River. Somerville politicians were running OUSU. Then, on 3rd February 1992, the Principal called an emergency meeting and announced that Somerville was going to admit men. The atmosphere in Hall changed instantly. There had been no warning this might happen, and there seemed no reason for

the change. The explanations offered – ‘financial benefit’; ’attracting male professors’ – were far from convincing. We already had great tutors, men and women, and the college seemed wealthy enough to us.

Our “Somerville Says NO” campaign was born within five minutes of that meeting. Within 24 hours we had over 1,000 red and black NO posters in the windows all over college. Soon we were holding a demonstration attended by thousands, and a barn-storming Union debate overwhelmingly carried our motion. When Margaret Thatcher and Shirley Williams came out in support of our campaign, we felt unstoppable.

But here’s the thing: we didn’t hate men. Most of us loved them. So why were we so angry? The fact is, our campaign was never about resisting new influences. It was about preventing the loss of what we already had, and which we knew made our college extraordinary.

Being at Somerville made us feel empowered. Its history inspired us, and our safe and supportive all-female environment gave us the confidence to

enter into and lead all aspects of undergraduate life at Oxford, and beyond.

Buoyed by public support, we took our case to the College Visitor, Roy Jenkins. After deliberating he recommended that the college postpone, rather than rethink, its decision to go mixed. At the time it felt like a defeat. But today, I’m not so sure.

Our goal had been to preserve what made Somerville special. By holding our protest the way we did, acting from the heart and with the best intentions, we made a stand for that distinctive Somerville ethos, demanding that it wasn’t diluted or erased.

If you go back to Somerville today, I think you’ll find it’s all still there: the same distinctive energy, and a student body packed with brilliant, principled young people eager to make a difference.

Perhaps what we ultimately did by going mixed was offer men the chance to share in Somerville’s enduring ethos, and to make their own contributions as proud Somervillians.

Sian Thomas Marshall (centre) in the front ranks of a Somerville Says No protest

DAN MOBLEY (1994, PPE) is Corporate Relations Director at Diageo, a member of Somerville’s Campaign Board and one of the College’s first male undergraduates.

In the autumn of 1992, I was a sixthformer from a Bolton boys’ school who had just crashed and burned through two days of interviews at Christ Church. I was about to head home, tail firmly between my legs, when the note came inviting me to Somerville. It was raining hard, and I remember sprinting across the city and arriving at Lodge feeling utterly soaked and dejected.

But from the moment I crossed the threshold, Somerville felt different. The warm red stone, the green expanse of the Quad – it all felt so much lighter and more open.

That sense of openness carried through to the interview itself. Instead of one forbidding don, here were three tutors who all seemed genuinely interested in talking to me. This was no box-ticking exercise, but a far-ranging conversation about books and ideas. Suddenly I was

It was thrilling to find myself in a place where thinking was encouraged everywhere and about everything.

able to be myself, and convey the real passion I felt for my subject.

A year later, I arrived at Somerville as part of the College’s first ever mixed cohort. It could have gone badly, I suppose. But right from the very first student whom I asked for directions, I never felt anything less than welcome.

The next three years were an awakening for me. After the rigid orthodoxies of a traditional education, it was thrilling to find myself in a place where thinking was encouraged everywhere, about everything.

My friends and I also understood that such freedom came with responsibility. Somerville’s history was all around us, and the courage and quietly incendiary radicalism of the women who carved out this space shaped our own sense of what was possible and what was right.

Speaking personally, I will always be grateful Somerville went mixed, because it welcomed me into a new way of seeing the world that I still call on today. But speaking objectively, I also think the

College in 2024 looks in better shape than ever. Its financial foundations are strong, its new projects in sustainability and sanctuary offer exciting ways to deliver its core values, and today’s Somerville students are simply amazing.

To be clear, none of these improvements are because men came to Somerville. It’s more that, at this unique distance from the event, we can see the decision to go mixed for what it was: a continuation of our College’s best traditions; forwardlooking, pragmatic and with a brilliance rooted in kindness.

Dan Mobley at his 1994

REBELS, VISIONARIES AND FRIENDS: Remembering Somerville’s Earliest Male Allies

For the second instalment in our reflections on 30 years of Going Mixed, we invited Somerville College’s Senior Associate, the author and social historian Jane Robinson (1978, English), to reflect on the small circle of men who became trusted confidantes and helpers in Somerville’s earliest days.

It was never going to be easy. The decision made 30 years ago to admit male undergraduates was so significant, so challenging, that it divided Somerville at every level. According to many, it was a betrayal of the college’s history and ethos; a shameful capitulation to market forces; a slap in the face for those whose commitment to women’s education was total. Others were proud to be associated with an institution courageous enough to break the shackles of the past and move

forward; excited by the prospect of reinvigorated student and teaching bodies; glad that no-one would be excluded in the future simply because they were the wrong sex. On one thing all agreed: after more than a century of being an institution run by and for women, things would never be the same again.

But lost in the furore was the fact that men have played a vital part in Somerville’s story from the very beginning. The 18-member committee formed to oversee its opening in October 1879 included an equal number of men and women. Among the former were two Heads of House and Fellows from five other men’s colleges, as well as a past Mayor of Oxford. Somerville’s first Council was similarly balanced. No matter how strong-minded our female founders were, they recognised the necessity for sympathetic and authoritative men to open doors for them, argue alongside them and vouchsafe their intellectual and moral credibility.

All our male founders were assets to the college, being distinguished academics, innovators and thinkers. The most helpful of them shared an enviably gymnastic ability to keep a foot in both camps – the Establishment and non-conformism –and therefore to act as go-betweens linking respectability to radicalism. They were a little like Trojan horses, effectively camouflaging the college’s startlingly subversive ambition to educate young women at the highest level.

One of the college’s most influential early allies was Thomas Hill Green (1836-82). When Somerville was founded he was a recently-appointed Professor of ancient and modern history at Balliol; a brilliant philosopher; an engaging Yorkshireman with a reputation for social idealism. He vigorously supported the suggestion that Somerville should be non-denominational (unlike Anglican Lady Margaret Hall up the road, also founded in 1879), convinced that our differences should enrich rather than divide us. That conviction informed his commitment to widening access across Oxford for those

Staunch allies: Principal Emily Penrose and Gilbert Murray after the visit of Queen Mary in 1921

disadvantaged financially, religiously or in terms of gender. Our proud claim to ‘include the excluded’ started with Thomas Green.

Another of Somerville’s early champions was Exeter College Classicist Professor Henry Pelham (1846-1907), grandson of an Earl and son of a Bishop. Despite this ultra-conventional background he was remarkably forward-thinking and a passionate campaigner for women’s suffrage. Professor Pelham had a knack for finding practical solutions to apparently intractable problems. He raised awareness and funds for the college by organising outreach events in towns and cities around the country, and advised Somerville’s early academics on how best to present their research to a sceptical academy. His affection for the college community was deep and mutual.

Neither Green nor Pelham are household names; better known is Gilbert Murray (1866-1957), Regius Professor of Greek, an early member of the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief (later

OXFAM), and a leading evangelist for the League of Nations. He was appointed to the Council in 1908 and remained until his death in 1957. A staunch ally and friend of the reforming Principal Emily Penrose, he championed degrees for women and loyally supported the whole community as we reached academic maturity. When a prospective tutor asked his advice on applying for a post here, he didn’t hesitate. Somerville, he said, was ‘more fun than a man’s college because it is new and growing and in

These men were a little like Trojan horses, camouflaging the college’s startlingly subversive ambition.

fact, “not a tram but a bus”’ – with all the free-wheeling possibility that implies.

We should remember these gentlemen and their colleagues with pride this anniversary year, as we celebrate our heritage as a mixed college. But there is one unacknowledged group of men to whom we should be equally grateful. These are the fathers of our earliest students. Eminent medics warned that thinking too much withered the womb, and social commentators predicted demographic disaster if universities were allowed to turn marriageable young women into sere bluestockings. Why would any sane man choose an extravagant, untested and arguably useless education for his daughter over the chance of grandchildren?

Thank goodness the fathers of pioneer Somervillians had the courage to send their girls into the unknown, because between them, they beat down a path that most of us – women and men –have followed ever since, without a backward glance.

The author would like to acknowledge Pauline Adams’s Somerville for Women (OUP, 1996) as a valuable resource for the history of the college from 1879-1993.

Henry Pelham - virtuoso problem-solver

Thomas Hill Green - a pioneer of inclusivity

The opening of the New Council Room in 1934; Viscount Halifax (Chancellor of the University) alongside Helen Darbishire (Principal), Emily Penrose, Mildred Pope, Maude Clarke and Alice Bruce

EVERYDAY EXILE: The City Urges Me to Remember

Dr Ammar Azzouz is a British Academy Research Fellow at the School of Geography and Somerville College. He reflects here on the redemptive power of writing his first book, Domicide (Bloomsbury, 2023), which fuses academic treatise with memoir and testimony.

Among the many trials of being a refugee is the question of identity.

How to think about the future without thinking about cities in ruins?

Who are you when you are forced to leave your city, your family, your homeland? Who are you when you arrive in a country that does not speak your language, or understand what pushed you out? Who are you when you live an everyday exile that shatters your heart a million times, in silence, each day, as you yearn for your childhood home, your mother’s coffee, your former confident self?

It is hard to put into words. I lived in a city called Homs, a calm and peaceful city in Syria. They called it the city of laughter, because

people had a beautiful sense of humour, known around the region. But all this changed in 2011 when peaceful protests were met by the brutality of the Syrian Government, which arrested and killed innocent civilians. One of them was my friend and fellow architecture student, Taher Al Sebai, killed whilst marching in a peaceful protest in my street in October 2011. It was the first time I had lost someone since the start of the revolution in March 2011. But it was not the last.

A month later, I left Syria, alone, for the UK. I have never been able to return. In my exile, I have lived in Manchester, Bath, London and now Oxford – but Homs has never left me. From miles away, I have watched the destruction of my city. Entire neighbourhoods wiped out, bombed and shelled. Our beautiful heritage targeted; our synagogues, churches, mosques, old souks, ancient sites that have stood for centuries, destroyed in minutes. The Syrian Government and their Russian ally have even targeted the bakeries where starving families wait for bread.

The destruction of the city goes hand-inhand with the destruction of its people and communities. From miles away, I have seen the people I love struggling to find medical treatment, unable to get enough food, losing their homes and families. I have collapsed many times after phone calls with people back home – their pain has also been mine.

In all, more than twelve million people in Syria have been displaced from their homes –

Destruction

around eighty times the population of Oxford. According to the UN, over 300,000 people have been killed. Other estimates put the death toll at more than half a million people, because after a certain point the UN stopped counting.

How does one live after this? I don’t know. Even when one arrives at the shores of sanctuary and safety, the memory of everything that has been lost never goes away. There are still feelings of estrangement, as if life no longer has a stable centre. The past never leaves you. It cries every day like a child until you go and hug it. It sleeps for a bit, then it weeps again. For those who survive war, the past is never the past.

I still hold Homs so tight in my heart. The city urges me to remember and, over time, the act of memory has become key to my survival. It is in words that I found a shelter, a home - and the hope that these words might be read and make a difference.

I have filled the years of my exile with writing, drawing, research, and interviews. Last year, Bloomsbury published my first academic book. It is called Domicide, and explores the systematic killing of home in my beloved city of Homs through the testimony of its people, contemporary architectural theory, and global notions of solidarity and resistance.

Like so much else in the last few years, the publication of this book comes with mixed emotions, pride as well as grief. This is the bittersweet paradox of exile: to have found safety, and to have lost so much. In my life now, I wake up every day an exile, and I thank God. I am grateful to find myself in such an open, liberal and free environment. I am grateful for the chance to meet and learn from incredible people here, and be touched by their everyday kindness. Most of all, I feel blessed to be able to write and research at this university, and to use my experiences and expertise to tell the story of my country. Education has played such a meaningful part in helping me rebuild a home in exile. I believe that through education we can build a different kind of tomorrow, a tomorrow that is just, free and dignified for all of us.

And how to think about the future without thinking about cities in ruins? Today, many cities, from Gaza and Mariupol, to Aleppo and Mosul, are waiting for reconstruction yet to come. By continuing to write and research questions of reconstruction, I hope to contribute towards a future in which we see every ruined city rebuilt again.

In words, I have found a shelter, a home, in hopes that these words will be read and make a difference.

‘A Mosque in Homs’, 2010. A drawing of Ammar’s from just before the Syrian Revolution.

The Destruction of the City of Homs, 2016, Deanna Petherbridge (1939-2024). Photography by John Bodkin. Source: provided to Ammar before the death of the artist

ACTIVE KINDNESS: Meet the Somervillian Who Saved Thousands from the Nazis

Somerville College this year marked Refugee Week with a special screening of the 2023 film One Life, featuring a Q&A with the film’s director and screenwriter, and a relative of one of its protagonists.

OI had no idea at all what to do, only a desperate wish to do something.

ne Life tells the story of the kindertransports by which thousands of child refugees from Germany escaped the imminent threat of Nazi persecution from 1938-39. A poignant testament to the power of sanctuary, the critically-acclaimed film also has several fascinating Somerville connections.

One Life was co-written by Lucinda Coxon (1981, English), an award-winning writer for both screen and stage, who reflects on her involvement with One Life overleaf. The film also depicts the famous moment on That’s

Life when Esther Rantzen (1959, English) introduced kindertransport organiser Nicholas Winton to a roomful of the grown-up kinder whom he had saved.

Perhaps most intriguingly for Somerville audiences, One Life features a show-stopping portrayal of Doreen Warriner, whose humanitarian efforts heading the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia (BCRC) were shaped by the Mary Somerville Research Fellowship she held at Somerville College from 1928-31.

Romola Garai as Doreen Warriner in the 2023 film One Life. Credit:Warner Bros

Warriner was born into a Warwickshire farming family at the start of the twentieth century. A first in PPE from St Hugh’s inspired her to begin a PhD at the London School of Economics on German industrial organisation. However, domestic issues forced Warriner to break off her studies and go home, where she worked sporadically until she applied for the Mary Somerville Research Fellowship in 1928.

Under the principalship of Helen Darbishire, Somerville welcomed Warriner with open arms. Most significantly for this story, the College actively supported Warriner’s newfound passion for Czechoslovakia. The Committee not only allowed her to change the subject of her PhD to focus on growing economic unity between Germany and Czechoslovakia, but also allowed Warriner to defer her residency in Oxford for a term in order to continue her research in Prague.

Indeed, under Helen Darbishire’s leadership, Somerville seems to have been at pains to support the young academic. Darbishire not only advised Warriner on how to prepare her thesis for publication, but even advised her on negotiating terms with printers.

Warriner continued her academic research until 1938 and the Munich Agreement, which she saw as a betrayal of internationalism. She abandoned her plans to go to the US on a Rockefeller Fellowship and instead, on 13 October 1938, flew to Prague. ‘I had no idea at all what to do,’ she later wrote, ‘only a desperate wish to do something.’

On arrival, she saw that her initial plans to open a soup kitchen were hopelessly inadequate. She began writing frustrated letters to the Telegraph and Guardian about camp conditions, stressing the need for ‘visas not chocolate’.

So began eleven months of desperate work as Head of the Prague office of the BCRC. Warriner later wrote of this time, ‘Every day the planes were full of the well-to-do going to London, sponsored by their friends and knowing how to push. I felt bound to say something on behalf of the people who could not push.’

And push Warriner did. Alongside Winton and Somervillian MP Eleanor Rathbone, Warriner lobbied the British government tirelessly to grant more visas and change its policy on allowing unaccompanied child refugees.

In all, Warriner is thought to have saved more than 15,000 refugees from the Nazis through these efforts. For this work she was awarded the OBE in 1941 and, posthumously, the British Hero of the Holocaust Medal in 2018.

I felt bound to say something on behalf of the people who could not push.

ONE LIFE SCREENING AND Q&A

In June 2024, Somervillians and friends met for a private screening of One Life. Afterwards, guests attended a Q&A with One Life’s screenwriter Lucinda Coxon (1981, English), director James Hawes and Doreen Warriner’s nephew and biographer, Henry Warriner. We also heard from two Somervillians with a sanctuary background – former Sanctuary Scholar Andrianna Bashar (2022, MSc Digital and Social Education), and our Research Fellow Dr Ammar Azzouz (see pp18-19) – on how to make our community a place of sanctuary for displaced students and academics.

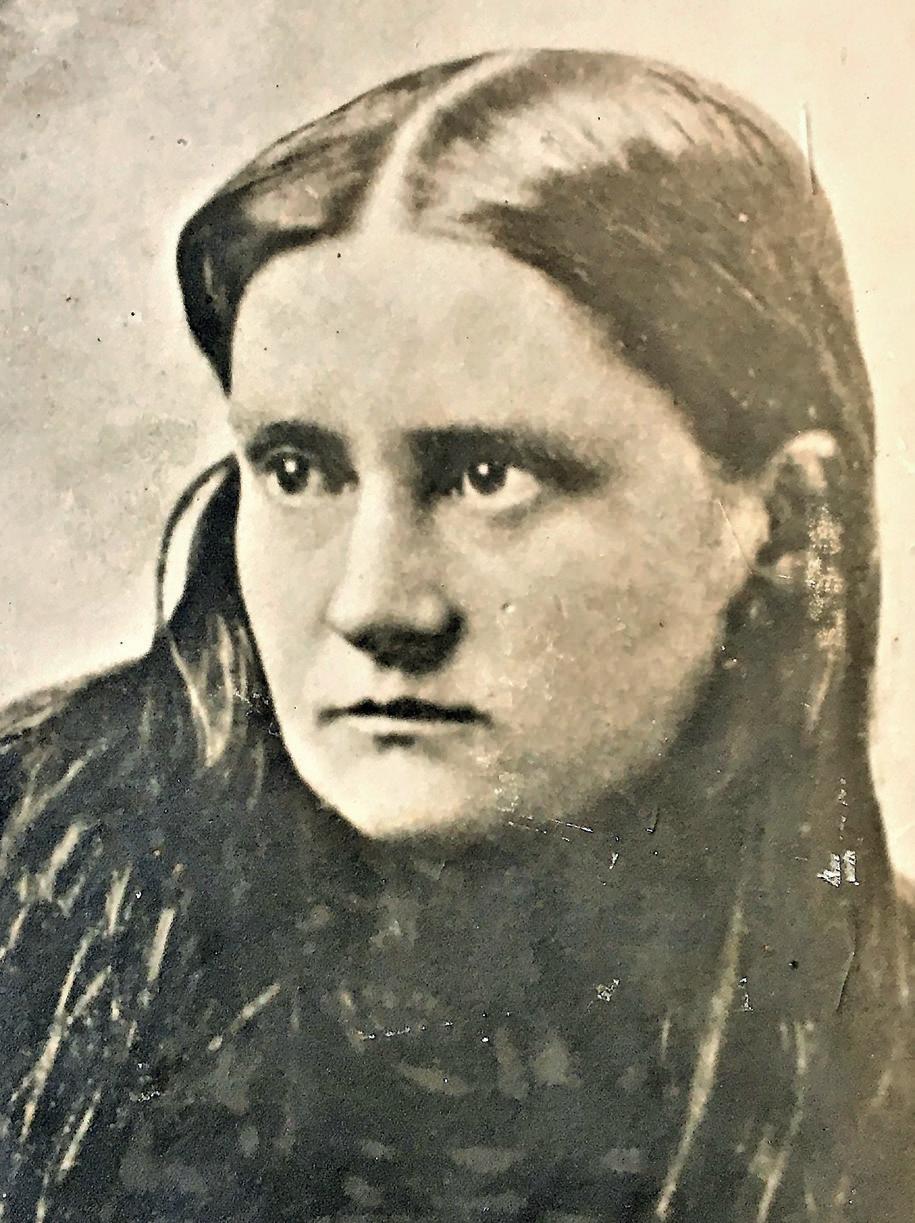

Doreen Warriner

LUCINDA COXON ON Telling Stories That Defy Despair

Lucinda Coxon (1981, English) came to Somerville as a first-generation student with a scholarship and a suitcase full of books. Today she is an award-winning writer for both screen and stage whose credits include the Oscar-winning film The Danish Girl. Here she reflects on her involvement with One Life, the new film about Nicholas Winton and the kindertransport

Iwas first approached to write the film that would become One Life back in 2015. At the time I was just coming off The Danish Girl, which had entailed 11 years of research and writing, plus all the pressure one feels when working with a real person’s story. So my first thought was… am I really going to commit to another historical biography?

Two events in quick succession helped make up my mind. First, I went to a screening of Legend, the film about the Kray Twins. I remember coming out of that cinema feeling so depressed, thinking what is wrong with us? Why are we spending all this time and money romanticising a pair of psychopathic criminals?

Later, as I wandered down into the Tube, I noticed the platform was littered with copies of the Evening Standard, each bearing the same image on the front page. It was the now infamous picture of Alan Kurdi, the little Syrian boy who was washed up in Turkey, drowned. There must have been a hundred images of this little boy all around me.

A great wave of despair and helplessness engulfed me. Then it came to me that I wasn’t entirely helpless. Yes, I might not be able to go out on a boat and rescue people, but I could write about this, and tell the story of someone who fought back against that darkness.

Yes, I might not be able to go out on a boat and rescue people, but I could write about this.

After saying yes to the project my next question was, okay, how do I deserve this? How do I earn the right to tell this story? I started with research – a lot of research. And I asked Nick Drake – a writer I very much admire who has Czech heritage – to co-write. We quickly established a close relationship with Nicky Winton’s daughter, Barbara, and got into the archive. I also began

volunteering with a refugee unit at a local school that was working with young Syrian refugees. Realising that I could make a practical contribution, however small, within my own community was galvanising.

Around this time, I discovered that Doreen Warriner, a key player in the rescue of so many Prague refugees, was a Somervillian. And she wasn’t the only one! Jean Rowntree, a Quaker and teacher was also in Prague, fighting to obtain exit visas for those in desperate need. Eleanor Rathbone, Somerville’s first MP, was similarly passionate and relentless in lobbying the Chamberlain government to admit more people fleeing Nazism.

As I got to know these and other stories, it became clear that our film couldn’t be a single hero narrative. Films invariably revert to this familiar structure, but it rarely reflects reality. Nicky and Doreen – and others like them – were able to achieve what they did because they were connected. Again and again, the story of the kindertransport is that nobody makes it work on their own; you need a network.

I also wanted to highlight that these were ordinary people: teachers and academics, stockbrokers and housewives. People whom nobody thanked at the

time, and indeed whom many saw as a nuisance. We chose to emphasise this ordinariness, smoothing over political ideologies, for example, so that everybody would be able to see themselves in our protagonists.

Driving all these changes was one thought: this film needs to do more than simply move people. Frankly, the story already had that power before we started. I have only to describe the moment on That’s Life when Esther Rantzen introduces Nicky to all the children he once saved, and people are reduced to tears.

There’s a real yearning in the world right now for stories that

elevate decency and push back against despair.

What we wanted was to make a film that empowered people. That said, look, we know everything feels terrible at the moment, and we’re all exhausted from living through this perma-crisis. But look what these people did: see what you can do if you make a contribution, however small, in your own community.

I think it’s significant that One Life was released around the same time as Mr Bates vs. The Post Office – and both productions really gripped the public imagination. Their success suggests to me that there’s a real yearning in the world for stories that elevate human decency and push back against despair.

The contemporary response to our film reminds me of the letter Jean Rowntree wrote to The Times following their obituary for Doreen Warriner. Jean wrote that the quality she most admired in her friend was that, even in the most difficult of circumstances, Doreen always believed in the possibility of good news.

Long may that belief continue.

One Life is out now on all major streaming platforms.

Somervillian guests and friends attend the One Life screening at the Phoenix Picturehouse, June 2024

Panellists at the One Life Q&A held at Somerville in June 2024: (l-r) Sanctuary Scholar

Andrianna Bashar, One Life Director James Hawes, Principal Jan Royall, Lucinda, Henry Warriner, Somerville Research Fellow Dr Ammar Azzouz

CRADLES OF CIVILISATION: From Aleppo to Oxford

Muhammed Zeyn is an Oxford EAA Qatar Sanctuary Scholar. He reflects here on the power of education, and how the migrant experience is reshaping masculinity.

Growing up in Aleppo, I witnessed firsthand the dire state of education in my homeland, where a scarcity of educational institutions meant disempowered youth had become the norm. This motivated me to journey from Aleppo to Istanbul and eventually to Oxford, driven by the desire to make a positive change in myself, close family, community and the world.

During my time in Aleppo, I was acutely aware of the oppression that had become part of everyday life. As circumstances became untenable, I made the difficult decision to depart for Istanbul, a hub of intellectual exchange which would become a second home to me. I pursued a Master’s degree in sociology at Ibn Haldun University, named after the historiographer and sociologist Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) whose work on history, civilization, and sociology has left a lasting impact.

As I delved deeper into my first Master’s research, I became fascinated by the experiences of displaced Syrian men who had sought solace in Istanbul. Through in-depth interviews, I uncovered their compelling stories, shedding light on how forced migration and the loss of home, livelihood, and societal standing can reshape conventional notions of masculinity. Despite facing massive hardships, these men courageously redefined masculinity, embracing virtues such as piety, integrity, faith, compassion, and assuming caregiving roles that transcended rigid social norms.

I was grateful for the opportunity to present my research at conferences in Lebanon, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Austria, contributing to discussions on displacement, masculinity, and identity. This experience not only deepened my appreciation for the power of education but also fueled my desire to continue

my studies. From Istanbul, my quest for knowledge led me to Oxford for a second master’s degree, in migration studies.

I am thrilled to have successfully secured admission to Oxford’s esteemed DPhil program in Migration Studies. The thread that binds Aleppo, Istanbul, and Oxford together is the pursuit of civilisational knowledge, a pursuit that has driven scholars and intellectuals for centuries. Through my studies in migration, I hope to contribute to the understanding and appreciation of the rich tapestry of human experiences, fostering meaningful connections across different geographies.

The thread that binds Aleppo, Istanbul, and Oxford together is the pursuit of civilisational knowledge.

As I begin my DPhil programme, I am reminded that success is not solely measured by achievements but is inextricably linked to embracing growth, cherishing the process, and acknowledging the impact made along the way. As I embark on this new chapter, I am filled with gratitude for the opportunity to contribute to the field of Migration Studies. Somerville College has embraced me as part of its family, offering steadfast support and encouragement. This holistic approach to individual development has been instrumental in enabling me to pursue my academic and personal aspirations.

Men fishing together on the bridge over the Bosphorus, Istanbul

A CAMPAIGN FOR SOMERVILLE

Next year, Somerville College will launch RISE, the largest campaign in the College’s history. RISE will enable us to secure Somerville’s future by galvanising support across four key pillars: Resilience, Inclusivity, Sustainability and Excellence. There will be a great deal more to say about RISE in due course, and plenty of ways to get involved. For now, we hope you enjoy these behind-the-scenes shots taken from the film we made in support of the campaign earlier this year.

NO MUSIC IN THE NIGHTINGALE Reviving Shakespeare’s Least Popular Play

We caught up with Jo Rich (2021, English) following his performance in The Two Gentlemen of Verona at the Oxford Playhouse. Tipped by Guardian theatre critic Michael Billingham as having ‘reclaimed this once unfashionable and unloved play’, the production was directed by Gregory Doran, former Artistic Director of the RSC and Oxford’s current Cameron Mackintosh Visiting Professor of Contemporary Theatre. Jo fills us in on what it was like bringing the play to life, working with Gregory Doran, and his future plans.

This is the only Shakespeare play Greg Doran had yet to direct. What was it like working with him?

Working with Greg was an absolute delight! He was always so careful and detailed in his consideration of Shakespeare’s language, which was inspiring in itself. But it was the way in which he helped us, as student actors, weave our own experiences into the text that really brought the whole production together. My character, Launce, even had his Hinge profile projected on the safety curtain!

The Two Gentleman of Verona is one of Shakespeare’s less popular plays. What might a contemporary audience gain from watching this production?

I think The Two Gents definitely warrants its less popular reception. The plot doesn’t feel polished in the way we expect from Shakespeare’s other plays. However, this has meant that a lot of the beautiful language within it has been overlooked, such as Valentine’s monologue ‘There is no music in the nightingale’.

As an English student, you will have studied a fair amount of Shakespeare. How does performing his work affect your engagement with the text?

It’s a game-changer! I genuinely believe engaging in performance should be a mandatory element in exploring Shakespeare’s dramatic works. Every time I performed Launce’s monologues I found something new. It transformed my own, very personal, perception of the character – which is so valuable in critical analysis.

Every time I performed Launce’s monologues I found something new.

Can you tell us a little about your character, Launce, and his role within the play?

Launce’s role within the play perhaps best sums up his character...he’s irrelevant! Launce genuinely serves no impact on the plot, so he really is just there to make everyone laugh! I think this offers so much flexibility and joy to the way in which an actor might go about portraying him.

You’ve just finished your finals –what next?

More acting! The plan was always to go into acting after my finals. But this experience has definitely helped - following the show I was fortunate enough to be approached by an agency to talk about representation!

A MODEL STUDENT

Mason Wakley (2020, Chemistry) spent part of his last term at Somerville on a personal project: rebuilding Dorothy Hodgkin’s ground-breaking model of the insulin molecule. Sixty years after Hodgkin won the Nobel Prize, he fills us in on the process.

Ihad often noticed Dorothy Hodgkin’s insulin model passing through the Somerville College library, and thought it was a shame it looked so neglected. When I learnt that this year was the anniversary of Hodgkin’s Nobel Prize, it felt like the right moment to bring this slice of Somerville history back to life.

My initial challenge was trying to use the model’s original parts: since they were around sixty years old, the plastic kept snapping. However, thanks to fellow Somerville chemists Georgia Fields (2020), Matt Lurie (2023) and Marshall Hunt (2020), I was able to gather enough donations of old molecular model kits to rebuild Hodgkin’s model.

After putting together the amino acids sequentially, the next challenge was taking something essentially 2D and making it 3D. The Somerville library’s collection of Hodgkin’s research papers proved useful here, but ultimately the fiddly nature of the construction could only be accomplished, through trial, error, and lots of patience! The process reminded me of the complexity and specificity of biology, as well as Hodgkin’s outstanding ability to take confusing crystallographic data and translate it into something meaningful.

In lectures, I’d learnt that Hodgkin began investigating insulin in 1934, the year she was appointed Somerville’s first Tutor in Chemistry. She was fascinated by its wide-ranging effect on the body, but at that point, X-ray crystallography could not handle the insulin molecule’s complexity. It was only in 1969 that Hodgkin and her team were finally able to confirm its structure. This was instrumental in enabling insulin to be mass-produced to treat diabetes.

Being a student at Dorothy Hodgkin’s college has been a real source of pride for myself and my fellow scientists. It’s inspiring that she remains the only British

The process reminded me of Hodgkin’s ability to translate confusing crystallographic data into something meaningful.

woman to have been awarded a Nobel Prize in science, and her breakthroughs in determining the structures of penicillin, vitamin B12 and insulin are foundational moments in chemistry. I also love the fact that she was deeply committed to Somerville and women’s educational rights, using a part of her Nobel prize money to establish the college nursery.

Sharing my love of STEM as a Somerville Access Ambassador has been an important part of my time at Somerville over the past four years. I hope the refurbished model, now on display in the library, can play a part in continuing that work when I’m not around. It feels good to make a small contribution to preserving such an important chapter in the college’s history.

Mason and the reassembled model alongside Dorothy Hodgkin’s portrait in the Somerville College library

The refurbished insulin model

Discovering Britain’s Lost Landscapes

Time and Tide: The Long, Long Life of Landscape is the latest book by Professor Fiona Stafford FBA, Fellow in English at Somerville College. A personal exploration of the landscapes, seascapes and skyscapes of Britain and Ireland, it draws our eye to some of the human and otherthan-human stories that surround us, if only we look closely enough. The following extract is from a chapter about drowned villages and valleys.

In 1994, a booklet was published to celebrate the centenary of a new water supply to Manchester. The text centred on the grand Victorian fountain in Albert Square, but was really more concerned with the radiating lines of pumps and pipes, dams and aqueducts, which brought the miraculous gift of clean water to overcrowded, diseaseridden homes. As Manchester grew exponentially over the course of the nineteenth century, the new textile mills and factories drew in workers from far and near. So rapid was the city’s industrial expansion that the quickly built terraces were immediately over-full, but under-supported. Elizabeth Gaskell’s Manchester novels offer glimpses of families living in cellars, nursing sick children, coughing cotton fluff from infected lungs and navigating the raw sewage in the narrow streets. Fresh water saved thousands of lives. But where

did the clear jet spurting up from the new fountain in Albert Square come from?

The water was piped over fells, under roads, across rivers, down valleys and into Manchester from Thirlmere in the Lake District. Work started in 1890 and within four years, the ambitious, life-changing project was complete. While clean water meant that lives were immeasurably changed for the better in late Victorian Manchester by the arrival of clean water, the effects on those at the northern end of the pipes were more equivocal. The celebratory booklet with its win-win story of boosting the local economy of the Lakes is rather different in tone from Ian Tyler’s book on Thirlmere Mines and The Drowning of the Valley. As soon as the focus is on the old communities and characters who lived and

worked in the valley flooded to form the reservoir, the powerful Water Company tends to be cast as the enemy rather than friend of ‘the people’.

As at Ladybower, the Thirlmere dam cost the lives of construction workers, the livelihoods of local shepherds, farmers, miners and teachers. At Wythburn a hamlet known as ‘The City’ went under, along with the school, The Cherry Tree Inn, and the Parsonage. All that survived of Armboth Hall was the old summerhouse, which still stands empty among the trees, except for the squirrels and wrens. The ancient Celtic or Wath Bridge which spanned the kissing point of the east and western shores vanished as the familiar figure-of-eight lake swelled around the middle.

Delight in Manchester meant despair in Thirlmere. A photograph of Reginald Bewley, taken around 1900, shows the elderly shepherd standing straightbacked, stick in one hand, well-grown lamb under the other arm, staring over the place he had known all his life. His home, Quayfold, survived the initial inundation, but when the reservoir expanded in the First World War it was demolished.

Many visitors to the area drive swiftly past Thirlmere on the A591 between

Keswick and Ambleside, barely aware of the shape of the lake they’re passing. The road passes beneath Helvellyn, whose massive bulk and height, though hidden from view, makes its presence felt. If you have more time, it is worth taking the narrow, winding road along the west side of Thirlmere and scrambling down through the tall beeches and pines to the water’s edge. The contours of the fells haven’t changed much since Reginald Bewley was a boy, the wooded form of Great How is still there, with the high, bare beak of Raven Crag beyond. But there are no cottages along the shore, no cattle drinking in the shallow water, no causeway crossing from side to side.

Last time I was there it was late summer, and the water was low. The rough expanse of grey rocks, dry stones and slate kept the still waves at a distance. A bleaching sheep skull lay beside a pair of pale, slightly contorted branches that must have been stranded when the water level sank. Hard to think that

All that survived of Armboth Hall was the old summerhouse, empty except for the squirrels and wrens.

they were ever alive and covered with green leaves. A strange sense of absence wasn’t helped by the dullness of the day. Under the heavy cloud, the flat sheet and jagged edge of the water seemed utterly drained of life. Not a single boat or solitary angler to be seen. Armboth Hall, which once stood nearby, was famous for its ghostly lights, ringing bells and a black dog haunting the lake below. A murdered bride would occasionally rise from the water, too, and attend a nocturnal feast in the Hall. No black dog on that September day, just a faintly melancholy feeling of vacancy. The only sound came from the stream of cars on the far side of the reservoir.

Time and Tide is published by John Murray and is available now.

“Thurlemeer” hand-coloured engraving by James Lowes, published in Lakes in Cumberland, F Jollie, Carlisle, Cumberland, 1800.

Don’t Rush the Biography!

SHEENA EVANS REFLECTS ON HER EXPERIENCE

WRITING THE FIRST BIOGRAPHY OF JANET VAUGHAN

When I was researching the life of Janet Vaughan, the first question I was asked by most Somervillians was: when were you up? I can’t see your name on the list.