The South Side Weekly is an independent non-profit newspaper by and for the South Side of Chicago. We provide high-quality, critical arts and public interest coverage, and equip and develop journalists, artists, photographers, and mediamakers of all backgrounds.

Volume 10, Issue 5

Editor-in-Chief Jacqueline Serrato

Managing Editor Adam Przybyl

Senior Editors Christopher Good Olivia Stovicek Sam Stecklow Martha Bayne

Arts Editor Isabel Nieves

Education Editor Madeleine Parrish

Housing Editor Malik Jackson Community

Organizing Editor Chima Ikoro

Immigration Editor Alma Campos

Contributing Editors Lucia Geng Matt Moore Francisco Ramírez Pinedo Jocelyn Vega Scott Pemberton

Staff Writers Kiran Misra Yiwen Lu

Director of Fact Checking: Sky Patterson Fact Checkers: Siri Chilukuri, Grace Del Vecchio, Lauren Doan, Ellie Gilbert-Bair, Christopher Good, Savannah Hugueley, Kate Linderman, Zoe Pharo and Emily Soto

Visuals Editor Bridget Killian

Deputy Visuals Editors Shane Tolentino Mell Montezuma

Staff Illustrators Mell Montezuma Shane Tolentino

Layout Editors Colleen Hogan Shane Tolentino Tony Zralka

Webmaster Pat Sier Managing Director Jason Schumer Director of Operations Brigid Maniates

The Weekly is produced by a mostly all-volunteer editorial staff and seeks contributions from across the city. We publish online weekly and in print every other Thursday.

Send submissions, story ideas, comments, or questions to editor@southsideweekly.com or mail to:

South Side Weekly

6100 S. Blackstone Ave. Chicago, IL 60637

For advertising inquiries, please contact: Susan Malone (773) 358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com

For general inquiries, please call: (773) 643-8533

Last week’s midterm elections led to a number of key victories for Democrats in the state and beyond, including several candidates the Weekly covered this year. Jonathan Jackson will be taking over from retiring Rep. Bobby Rush in the 1st District after beating more than a dozen other candidates in the primary. Delia Ramirez, who the Weekly wrote about ahead of the primary, will be the representative for the new majority-Latinx Illinois 3rd District.

Alexi Giannoulias, who detailed his plans to the Weekly in June, will take Jesse White’s place as Secretary of State. In Cook County, Fritz Kaegi easily secured reelection as Assessor despite a campaign by real estate interests to unseat him, and Amendment 1, otherwise known as the Workers Rights Amendment, will be added to the state constitution, enshrining the rights of workers to collectively bargain and preventing the passage of right-to-work laws in the future. Other notable wins include Tammy Duckworth’s re-election as Senator and J.B. Pritzker as Governor. Republicans gained at least one seat in the State Senate, but lost at least four seats in the State House.

At the national level, Democrats have retained control of the Senate with key victories in Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Arizona, and a Senate run-off in Georgia will determine the margin of control. Republicans have made gains in the House, however, and as of publication look to be within reach of a majority there. The midterm elections seemed to surprise some pundits who were predicting a “red wave” but problems with the accuracy of polling underestimated that people would turn out to vote blue, with many pointing to abortion as a key factor in that support.

As soon as Democrat wins in Congress became evident, Rep. Jesús “Chuy” García, a Lightfoot ally up until Election Day, announced his candidacy for mayor of Chicago. He previously forced former Mayor Rahm Emanuel into a runoff in 2015. Cook County Commissioner Brandon Johnson announced his run weeks earlier than Chuy with the endorsement of the Chicago Teachers Union, followed by SEIU, and said he wouldn't back down. Both candidates have a history of strong progressive support and their combined candidacy has the potential to divide their base geographically or along racial lines. Despite the recent withdrawal of North Side candidate Ald. Tom Tunney from the race, there are fifteen candidates currently in the ring, including incumbent Mayor Lori Lightfoot. They include alderpersons Sophia King, Ray Lopez, and Roderick Sawyer, activist Ja’Mal Green, and former Chicago Public Schools CEO Paul Vallas. Municipal elections are in February 2023.

On November 4, the Gene Siskel Film Center, located at 164 N. State, kicked off the 28th Black Harvest Film Festival, an annual celebration of Black film and the African diaspora. Festival-goers can enjoy feature films and short film collections, special events, and conversations with actors and directors.

In-person viewings and events are scheduled through November 21, followed by virtual showings through November 27. Mars One, a 2022 film in Portuguese with English subtitles, follows a lower-middle-class family in Brazil, amidst the election of the far-right Jair Bolsonaro, as they struggle to keep their family together while grappling with identity, ambitions, and economic pressures. Redbird is about a rodeo rider in Oklahoma with dreams of doing his passion full time. And the Sisters in Scene short films explore topics like Black femininity, isolation, and coming-of-age. If you miss seeing any of the films in person, tickets and passes can also be redeemed for virtual screenings Nov. 21-27. After hosting the first ever, fully virtual festival in 2020, the film center created a hybrid experience in 2021 and 2022.

This year’s celebration is in honor of the late Sergio Mims, a film journalist, historian, and co-founder of the festival. Mims, who passed away this October was a Hyde Park resident and attended Kenwood Academy as well as University of Illinois Chicago. For more information, go to siskelfilmcenter.org/blackharvest

schenay mosley: a new era

The Chicago musician and educator talks about creating a different sound.

kia smith 4

swervin’ through food deserts

Rapper G Herbo teams up with Dion’s Chicago Dream to alleviate food insecurity. chima ikoro 6

the journey of an asylum seeker

South Chicago nursing student Estafany tells the story of her family’s immigration journey. monet thornton .................................... 8

el recorrido de una solicitante de asilo Estafany, una estudiante de enfermería en South Chicago, cuenta la historia de inmigración de su familia

monet thornton 9

review of king david and boss daley: the black disciples, mayor daley and chicago on the edge

Professor Lance Williams traces the stories and conflicts of two powerful Chicago leaders. bobby vanecko

the exchange

....................................... 11

The Weekly’s poetry corner offers our thoughts in exchange for yours. chima ikoro, lucy walsh 15

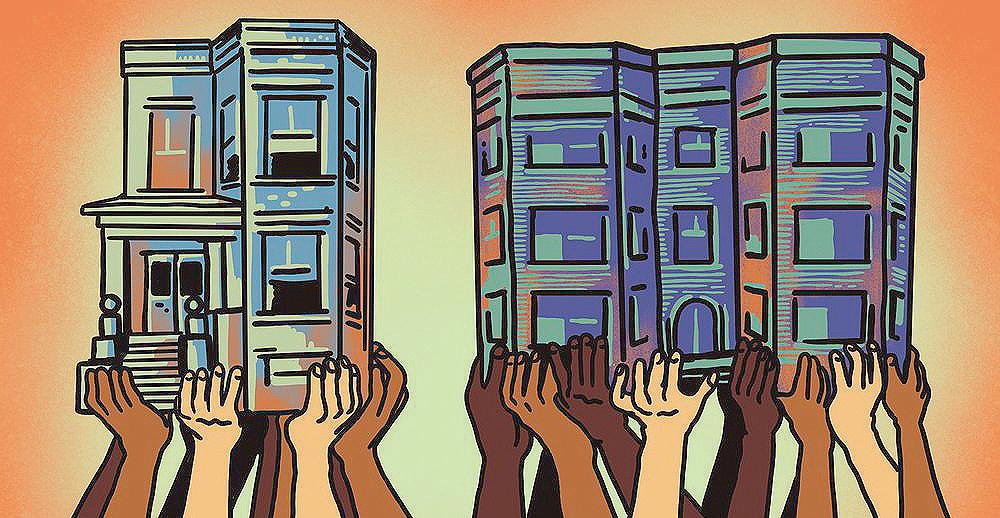

chicago housing cooperatives, explained How are housing cooperatives different from communes and who are they for?

jhaylin benson, grace del vecchio, annabel rocha, sonal soni, jerrel floyd, city bureau

.............................................. 16

the case of tony robinson Incarcerated for twenty-five years, new evidence suggests innocence. invisible institute staff 18

calendar Bulletin and events. zoe pharo 21

Cover photo by Kevin MaresThe Chicago musician and educator talks about creating a different sound.

BY KIA SMITHThe 2022 version of Schenay knows exactly who she is.

Schenay Mosley is a multiinstrumentalist solo artist, as well as a backup singer for Smino and his Zero Fatigue collective. The Dayton, Ohio native is also an educator and activist who uses her gifts to give back. In short, she’s a Jack(ie) of all trades.

In an interview with the Weekly, we got to learn more about Schenay’s artistic journey, her experience in the Chicago music scene’s 2010s renaissance, a recent appearance on Jimmy Fallon, and what keeps her going.

For more information and updates on Schenay, follow her Instagram @schenaymosley. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you speak to the work you’ve done teaching people how to make art?

Schenay: I’ve always been an activist— especially in high school [at Stivers School for The Arts] as a peace ambassador. I’ve always protested and given out supplies to people in the hood.

In my adult life, I was a part of the Mike Brown and George Floyd protests. I’m a teacher as well. I teach children and adults piano and vocals, both privately and at Phil Circle Music School. I’ve always loved teaching and giving back to the community somehow, and I’m working on building my own school.

How did you realize you wanted to be an artist? What moment—or moments— set in stone that you actually are one?

My mom gave me a keyboard when I was around four years old because I used to tap on tables all the time. I started producing around eleven or twelve because my cousin would use our computer and speakers in our basement, and when he was done, I would go down there and mimic his beats and produce my own stuff. I was getting pretty good, and I told my dad, “I wanna be an artist.” He was like, “You wanna be an artist?” and I was like, “Yeah.” He said, “Well, you know artists only make like ten percent. You wanna be a songwriter?” And I was like, “I wanna do that, too—but I wanna be an artist.” And basically, I’ve been crafting myself since I was a child.

But when I had the realization that “I’m really doing this,” I was in my 20s. I had a band and we used to perform at The Shrine, we had our own nights there. It wasn’t until we saw success as a band that I was like, “Wow. We’re really doing this.” Unfortunately, the band broke up, but that’s when it clicked: Like yo… we were poppin’!

Can you describe the feeling of doing something that makes you happy, and living and working towards your purpose?

It feels great. I don’t see me doing anything else. I do see me doing other things, like movie scoring, and other things in my field.

I don’t have to just be an artist because I love music. I love everything about the arts and entertainment industry, it’s fun.

I do feel like I can do more, through—I feel like I have more to give. I can go to higher levels, and I’m ready to push the boundary and see how far I can go. I’ve done some cool things—I ain’t famous or

BY THOUGHTPOETbehind the scenes.

The other cool stuff I’ve done, besides being in a band called She which later changed its name to Highness Collective, was backup singing for artists. I was also playing keys for artists: I’ve done a Lion Babe show, and I’ve sung with Adam Ness, who gave me solos in his show. From then on, I started singing backup for Smino, starting in 2016.

Can you describe the process you go through when you create your music?

nothing, but I’ve done some cool stuff. I want to continue to do more cool things on a bigger scale.

If someone was like, “put me on to Schenay,” what would you show them or have them listen to?

I’d have them listen to my music. I put out an EP called Lotus (2018), but I took it off streaming services ‘cause I didn’t like it, and I wasn’t going to pay $250 to renew it. I’ll eventually put it out there through DistroKid. But my Silk Ca$hmere EP, that’s the one I’d put them on to, that’s the one where I was deep in my R&B bag. I don’t have an album out or anything because I’ve been working

I get in the mode of: I wanna make a project. Then I think, what is it going to be about? With this project that I am currently working on, I went through a break-up. I was with my ex for six years, and it kinda got nasty the last two years— it was just not a healthy relationship. And it wasn’t always bad, but it was getting bad. This project is basically me expressing my feelings and processing my emotions, and then healing and moving on.

Then I develop a sound. This is the image I want for this project. This is the sound I want for this project. This is what I’m going for. I’m like Sade, it takes years for me to do stuff. But I’m trying to learn how to work faster, because I do everything. I produce, but I do work with other producers like Renzell and a group called Don’t Trip out of L.A. I just kinda center everything around the vibe of the project.

How did you get involved with Smino and Zero Fatigue? What has your experience been like since joining the team?

My friend Loona mentioned that he

“silk cotton cashmere,” and I said: “I like that!”

For this next project, I’m kinda expanding upon that—but the sound is a bit more futuristic, a bit more experimental. Still vibey, but I want to expand the sound, expand the minds, test the limits of what I can do.

Do you find it challenging to pinpoint the genre of music you make? If someone was to say Schenay is a [blank] type of singer, how would you fill in that blank?

I just tell them alternative R&B. That’s like the blanket term. I like different stuff. I always say, if James Blake and Solange had a baby, that’s me. James Blake is very experimental, yet it’s not [so] experimental where you don’t know what’s going on. Solange is very vibey, but also intense. The band that I was in,

everyone else.

Now, I do not care. I feel that because of TikTok and other things, the way things are progressing, people are now open to hearing whatever in 2022 going into 2023. As long as it’s cool, people will listen. Of course, you have your little hits, viral stuff. But I feel like people are searching for something different, something that feeds them, something that’s not ordinary, but still makes sense.

Who was Schenay ten years ago in comparison to Schenay now?

Schenay now knows exactly what she wants; she knows exactly what to do. She knows exactly how to move. She’s not afraid anymore. Schenay, back in the day, used to overthink everything. Now I’m like, “Girl, you is tripping. It’s not that deep.” Back then, I had visions for things. I wanted a certain type of art, I wanted a

You’ve mentioned numerous times that you’re working on a new project, when can we expect it? What can we expect next from Schenay?

This next project gonna be fire! The visuals and images are gonna be a bit darker, more sexy and sensual, but with a dark futuristic twist to it. I’m gonna drop singles first, but you can expect the project to drop at the top of the year. ¬

Kia Smith is a lover of words and digital storyteller. She previously wrote about the Silver Room Block Party for the Weekly Keep up with her on Twitter and Instagram @KiaSmithWrites_

BY THOUGHTPOETneeded a singer. So I went to the first rehearsal, and he was like, “You like the missing link!” And I was like, “Bet!”

And then that was it… He was a fan of our group [Highness] before we even knew who he was.

How has that transformed you as an artist? What have you learned along the way, as far as the business side of music?

I’ve definitely learned to make sure your paperwork is straight. And I’ve definitely learned that business is business. Make sure you’re ethical, and have multiple funnels of income to fund your music.

What was the inspiration behind the Silk Ca$hmere EP, and why the title?

With that EP, I was on my “grown and sexy.” When I thought of the sound of the project, I thought of the way it felt—like silk cashmere, a really soft, warm, sexy, sensual vibe. The money sign in it is pretty random. I always liked money. I was at the store and I saw this sweater that said

we called ourselves “omnisoul.” The basis of everything was soul music, but we dabbled in everything: rock, a little bit of this, a little bit of that.

With navigating the independent and mainstream music industry, have you ever felt pressured to stick to a more recognizable R&B sound? What is it like operating in this alternative R&B space?

A few years ago, I was pressured to sound like everyone else. My Lotus EP was very different, and I don’t know why, but I was nervous having that out. I made every song on there, I produced everything on there. I feel like if it was released a few years from now, people would get it. But yes, I was pressured to sound like

certain type of aesthetic. So I felt like I couldn’t do it if I didn’t have the money or resources to do it. I wish I would’ve done it back in the day anyway.

Now I’m tapping back into that creativity I had as a teen: “Just go do it. Let’s just make some cool stuff and not overthink it.” Now that I’m an adult, I know how to make things refined. Schenay now knows exactly what the hell she wants to do.

What advice would you give an aspiring artist who wants to share their gift but is too afraid to do so?

Just do it. When it feels good in your gut, that’s when you know. When you can play it without cringing, when you’re excited to share it with others, that’s when you know you’re ready.

“I feel like people are searching for something different, something that feeds them, something that’s not ordinary, but still makes sense.”

–Schenay Mosley

BY CHIMA IKORO

BY CHIMA IKORO

Chicagoans are no strangers to the idea of combining efforts to feed their neighbors. When Chicago Public Schools (CPS) halted free meal distributions at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, restaurant owners, activists, food banks and community groups took matters into their own hands and found ways to break bread across the city. Other initiatives like Market Box began as a pandemic mutual aid response but continue to provide fresh food to households across the South Side. It goes without saying, many Chicagoans are well-acquainted with finding a way to provide what is needed on their own. Dions Chicago Dream is a prime example of these efforts.

What Dion Dawson started two years ago as a way to address a lack of consistent access to quality fresh food has blossomed into an organization that has distributed over 200,000 pounds of produce to date. Now, he’s partnering with G Herbo and the rapper’s mental health initiative, Swervin’ Through Stress, in order to broaden their impact on the residents of the city they so proudly call home.

The Weekly sat down with G Herbo and Dion Dawson to discuss the intersection of mental health, music, influence and remedying food insecurity. What seem to be unrelated at face value have proven to work well together to improve the quality of life. “Food insecurity goes hand in hand with stability and safety,” G Herbo said.

“You know, I come from poverty for real. So I understand without the proper nutrition or the proper support system in general it breeds violence, it breeds anger. It breeds no self-discipline—if you don’t have food, where I come from, the first instinct is to go out and take, to go steal.”

Proudly representing Over East and

the South Side of the city, G Herbo is more than familiar with the struggles of the communities he’s making an effort to serve. This familiarity is what prompted the creation of Swervin’ Through Stress, geared toward helping young people struggling with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In light of his current success as a musician, there’s no better time to address the challenges faced by young people coming out of the violent and inequitable circumstances he was raised in.

“I think it’s important for artists to do philanthropy work. I think other than entertainment, rap music and hiphop is the biggest platform when it comes to influence—I think we have the most influence on the youth. And with philanthropy work, it shows kids, ’nah, that’s not cool, this is the right thing to do.’” G Herbo said. “I know, for a fact, things won’t get better in the city unless you empower the youth.”

Dion admires artists like G Herbo, who make something of themselves and still

return to find solutions for the issues their communities continue to face. “There’s no denying how many people he inspires with his story. There’s no denying how many people he’s touching through his music, there’s no denying that he’s a Chicago kid, like all of us,” Dion said. “When you’re looking at Swervin’ Through Stress, which is just starting to really get its groove, he found something that related to him and his story, which is about the mental health aspect, and we have food, and we know both of those go hand in hand.”

G Herbo similarly draws a clear line between mental health advocacy and access to food, and further connects the two to the cycle of violence. “Mentally, when you’re hungry, you just feel like you on your own and nobody cares. You develop that [thought] throughout the world. When you feel like you’re on your own, you treat people as such, you treat people like you don’t care for them since you feel nobody cares for you,” he said.

The rapper cites that violence is

worsened by a lack of unity and support between community members who may not understand the impact they can have on the next person. “Nobody really shows support to one another or make anybody feel like, ‘Hey, I’m here, you could just talk to me, and then if I can help you in any way, then I will,’” he said.

The uptick in crowdfunding and mutual aid efforts in the past couple of years have shown what is possible when people put their minds, time, and money into projects that provide for those in need. Dion and G Herbo believe in the importance of doing one’s part and making use of the resources available. In Dion’s case, this has also included creating those resources in order for his organization to have an impactful reach.

“I never fundraised before I started my org. But what I saw was even the big international organizations, they petition monthly donors, they go out and find different ways to raise money. And so the only thing I did was, I don’t shy away from having to raise money,” Dion said.

The fight to remedy the disparities that have their shared communities in a chokehold is not just for the sake of philanthropy—it’s personal. “I love my city. I love the neighborhood that I grew up in and I want to make those environments safe. I want to make those environments positive. I want to make sure the kids become the best version of themselves like I did. I was just a diamond in the rough,” G Herbo said, adding that without God and his own fearlessness and sacrifices he made, he would not have made it.

But he wouldn’t wish that experience on others. “It shouldn’t have been like that for me. I should have had all the resources to just be great, period. I shouldn’t have had to do those things and endure a lot of the

things that I endured growing up, just to get here today,” he said.

The harsh reality is that many young people are forced to develop survival tactics as a result of their environments, and the situations they encounter are not mild; it’s life or death.

“Philanthropy is important for me because these kids shouldn’t have to lose their innocence at such a young age,” G Herbo said, “They should automatically have the resources that they need to go out and be successful, to have a good day through school, to strive, to go to college to go do whatever it is that they want to do in life, and I think people like myself, with providing those resources and those opportunities for the kids, it makes life that much easier.”

He still hopes for changing resources for his community despite being fortunate enough to have left those circumstances behind. “It’s important for me because I have kids. I don’t want my kids to grow up with certain advantages that other kids like myself didn’t have,” G Herbo said. “My kids should not have more advantages than the regular African-American child that’s growing up in the inner city and these poverty stricken neighborhoods that I grew up in. And that’s just me being real.”

When Dion spoke of the intersection between influencing youth and philanthropy, he implores others to focus on their own individual contributions, rather than comparing themselves against each other. “I think we have to understand that not everybody can do what Herb does, and not everybody can do what I’m doing. But they can do their part,” he said. “It’s about motivating people to think beyond where they are.”

There’s no debate that a lack of access to fresh and healthy food decreases both quality of life and life expectancy—and in Chicago, this primarily affects Black and brown communities on the South and West Sides. According to an NYU study published in 2019, of the 500 cities surveyed, Chicago has the widest life expectancy gap between communities: a difference of thirty years between Streeterville and Englewood. When discussing the effects of food insecurity, it may be easy to overlook the domino effect these scarcities can have on the overall health and well-being of a

community.

Dion himself is from Englewood, where a Whole Foods closed this week despite being opened in order to combat the food desert it was built in. In his opinion, this is a perfect example of the importance of community- owned and run projects that are not only effective, but sustainable as well.

Through what the organization calls Dream Deliveries, one thousand dollars provides a household with a year’s worth of fresh produce. The quality of the food, which is arguably better than what you may find in the grocery store, comes directly from a wholesale grocer.

“Initially when we started Dream Deliveries, we took a map of the bottom ten percent average household income neighborhoods and then superimposed a map of food deserts in the city. We canvassed and enrolled,” Dion said. “After that, it has been word of mouth.”

The organization has minimized enrollment through their website with the intention of being considerate of older residents and community members who don’t have consistent internet access. “Once our waitlist is under fifty homes, we will open sign-ups online,” he said. Currently, the waitlist has 397 households.

Dion stresses the importance of the impact being more than just a story, and he looks to the numbers of families served as a marker of that impact. “This is not Herb and his team thinking or hoping we’re doing it, this is them knowing that we’re doing it,” he said. According to Dion, by the end of November, the organization will reach 500 homes and over 2,600 residents weekly, while distributing 18,000 pounds of food across twenty-five Chicagoland

do that shit. Because nobody would expect an org that started with no money to be a million dollar organization two years later, they wouldn’t expect us to start with one community fridge and end up with five delivery vehicles, [and] nine employees.”

The catalyst of his organization, Dion’s Dream Fridge, was launched in September 2020, and is located on the corner of 57th and Racine in Englewood. The community fridge is open Monday through Friday from 9am to 4pm, and is stocked daily with fresh produce and water.

Having recently dropped a project, titled Survivor’s Remorse, G Herbo has had his hands full with music video releases, traveling, and all that comes with being an artist. Still, he finds time for what he deems necessary and important. Losing sleep is a reasonable sacrifice in his opinion because “people make time for what they want,” the rapper said. “And this is one of those things that’s important to me.”

A memory G Herbo holds dear is that of his aunt volunteering to serve the community since he was a child. Whether it was a local youth center or the Boys & Girls Club, no matter where they moved she made it a point to be involved. “She still does it to this day—the kids love her. And a lot of these kids don’t have that sense of unity and family at home, so the only place they get it is at school and in these extracurriculars.”

“It’s a lot of beautiful things that come from it,” G Herbo said of the South Side. Although hardships can easily become the focal point of one’s experiences, he shared how growing up in these neighborhoods also made him better. “Us not having much, but still trying to stick together, you know, that’s where people learn loyalty.”

“It was important for me that nobody dictate where we are going and what we do,” Dion said. “All of our delivery vehicles and our Sprinter [vans] and our twenty-foot truck, we own it. And when we’re talking about our staff, not getting around paying them, because we’re also creating a problem if we have people working or volunteering in food justice, and they’re not even taking care of themselves.”

neighborhoods monthly.

When it comes to problems as complex as food insecurity, Dion has witnessed that there is no linear timeline to solving this issue. “A lot of the progress that was made in food justice, over the last decade or so, was wiped out because of the pandemic and the problem got worse,” he said.

“I never ever, ever, ever, ever use the word ’goals’—whatever we say we doin’, we

As for Dion, the sky’s the limit as to where his dreams can go. The partnership between Dion’s Chicago Dream and Swervin Through Stress plans to bring 50,000 pounds of fresh produce to residents across Chicago. “I’m like South Side Weekly, man! If I’m breathing, I’m doing this shit. If I’m breathing, I’m putting numbers on the board,” he said. ¬

To learn more about this collaboration, visit dionschicagodream.com and follow G Herbo on Instagram @nolimitherbo.

“I come from poverty for real. So I understand without the proper nutrition or the proper support system in general, it breeds violence…”

–G HerboPHOTO BY KEVIN MARES

South Chicago nursing student Estafany tells the story of her family’s trek through Central America, Border Patrol facilities, and the U.S. asylum system.

BY MONET THORNTONChicago has welcomed over 3,600 Latin American asylum seekers in recent months. Much of the news coverage has centered around how the City and other organizations are meeting short-term needs via donation drives and what it will take to provide long-term stability. Yet while it is vital to uplift these efforts, the individual stories of immigration can get lost in the mix.

The South Side Weekly was able to connect with a student living in the South Chicago neighborhood who immigrated to the United States in 2019. Estafany, originally from Honduras, graciously shared her and her family’s story of immigrating to the United States with the Weekly.

Estafany grew up in San Pedro Sula, Honduras with her mom, dad, and younger sister. One of her fondest memories growing up was celebrating New Year’s Eve with her family. She enjoyed a tradition of spending the evening with friends at the park and then running home right before the new year rang in. She would join her family at home where they would pray together as a family and share with family members the wonderful things she wished for them in the new year.

These lovely traditions were overcast by rampant violence, police corruption, and crackdowns on freedom of expression in Honduras. According to the Human Rights Watch, “violent organized crime continues to disrupt Honduran society and push many people to leave the country.” Estafany and her family were some of the people who elected to leave Honduras due to the ongoing violence in the country.

Estafany said the journey from

Honduras to the United States took a total of nine days. She began her journey on May 2, 2019 in San Pedro Sula, in northwestern Honduras. The first stop her family made was in Corinto, Honduras, approximately a two-hour bus ride from San Pedro Sula. Corinto sits directly on the border with Guatemala. There, Estafany was able to comfortably make it through customs with her passport and knew “she wouldn’t have any problems with Guatemalan authorities.”

Once in Guatemala, it took two days for Estafany and her family to reach La

that [the] people who lived there would hand us over to Mexican authorities.”

In the following days Estanfany’s family rode in buses across more than ten cities before finally arriving at the MexicoArizona border. In Mexicali, Mexico Estafany’s family turned themselves over to United States border authorities.

The family was taken to the Yuma, Arizona Border Patrol station where they immediately had to hand over all of their belongings and were separated by gender. The women in the facility were all on one side while the men were kept

asthma attack, they would not have access to adequate care to help her.

According to Estafany, there were fewer than five bathrooms available on her side of the facility, which housed around one hundred women. This was a major sanitary concern as none of the migrants were able to brush their teeth or bathe. Some of the migrants had been there for over a month without any access to hygiene products.

Everyone at this facility was waiting for their information to be collected. Estafany said that the officers would come outside to call people’s names and collect personal information for their asylum application. But it was easy for people to miss their names being called due to language barriers and the mispronunciation of names, leading officers to move down the list.

Técnica, a small village that sits on the Rio Usumacinta, the river border with Mexico. Her family stayed at the Técnica Peten, an agricultural and archeological cooperative that also serves as lodging for migrants looking to go into Mexico.

It was at this point in her journey that Estafany began to fear that her family would be deported back to Honduras. Once in Mexico, Estanfany said that “we [slept] in a hotel … we were very afraid

on the other. All of the migrants at this facility were housed outside and were given a small thermal blanket to protect them from the rain and cold. At night, Estafany would join her and her sister’s blanket to give her sister more warmth.

In addition to subjecting people to difficult housing conditions, the facility lacked basic healthcare and hygienic services. Estafany’s sister had asthma and was worried that if her sister had an

Estafany’s family also found out that the officers wanted to send them to the hieleras—or ice boxes. Hieleras are infamous facilities where immigrants are in freezing rooms with only small blankets. In 2016 the federal district court in Tucson, Arizona released photographs of the Tucson Border Patrol facility which showed people sleeping on wooden benches and concrete floors, and one shows several men sharing one thermal blanket.

The hieleras had worse hygiene conditions than the facility Estafany and her family were staying in. One person testified that in their room, “there was one sink but no soap or towels. Most people had spent time in the desert and were very dirty, but it was impossible to wash your hands or clean yourself … the conditions became disgusting with so many people packed into a cell this way.”

Estafany and her family have had the opportunity to get to know many of their neighbors and were shown their generosity. Many of their neighbors have helped her family by providing clothes and food, and Estafany says their generosity and grace have helped her focus on her studies.

Her family were not moved to the hieleras because of her sister’s asthma and the likelihood of an asthma attack.

Once Estafany, her sister, and her mother gave their information, they were able to make contact with her aunt who lives in Chicago. Their family’s stay at this Border Patrol location was relatively short-lived—they stayed there for three days and two nights before flying to Chicago on May 11, 2019. Without having a relative who already lived in the States, Estafany said that “the decision to immigrate to the United States would not have been an option.”

Estafany and her family have established themselves in the South Chicago neighborhood, where she says her family is “very comfortable.” But it took a lot of acclimating to get to this point. She pointed out that learning a new language, American culture, and the change in climate were her biggest struggles in settling in Chicago. Despite all the change, Estafany said that she was grateful that she had her family to lean on while they were going through it together.

Since coming to Chicago, Estafany has enrolled in the Basic Nurse Assistant (BNA) program offered at the South Chicago Learning Center, a satellite campus for Olive-Harvey College. Estafany looks forward to completing the BNA program to “help my new community and be able to contribute a good deed to the country.” Estafany and her family have had the opportunity to get to know many of their neighbors and were shown their generosity. Many of their neighbors have helped her family by providing clothes and food, and Estafany says their generosity and grace have helped her focus on her studies.

Estafany and her family were granted permanent asylum in the United States in November 2020. The process of applying for asylum was not easy and required Estafany’s father to reach out to an organization of lawyers who helped immigrants coming into the country. Seeking asylum does not begin and end with turning yourself in to border authorities. Individuals seeking asylum must first submit an application for asylum, which must be completed within

the first year of the asylum seeker(s) entering the country. In the next stage of the process, the credibility screening, border officials determine whether or not an individual has a credible reason to seek asylum in the U.S. An individual has a credible reason to seek asylum if they are “seeking protection because they have suffered persecution or fear that they will suffer persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a social group, or political opinion”. If deemed not credible, removal proceedings begin, and the asylum seeker(s) can appeal their case through the Board of Immigration Appeals.

Estafany’s family was fortunate to have their case for asylum approved by United States Customs and Immigration Services. As of 2021, approximately sixtythree percent of asylum seekers are denied their cases and are inevitably deported back to their home country. According to the American Immigration Council, “in many cases, missing the one-year deadline is the sole reason the government denies an asylum application.” Navigating the immigration system is nearly impossible without the assistance of a lawyer that is experienced with asylum cases.

Estafany’s experience is just one example of a simple reality: it is not easy to pick up and move to an entirely new country. In Honduras, her family faced rampant violence that urged them to seek a better place to raise their family. They trekked by bus across Central America, lived in overcrowded and unsanitary Border Patrol facilities, and had to navigate the immigration system to solidify their place in this country. Their battle continues as her family is currently trying to secure their residency permit. All the while, Estafany is studying at the South Chicago Learning Center to become a Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA) amidst a healthcare worker exodus. Their resilience and bravery are values that Estafany has embodied and looks to spread throughout her community in the future. ¬

Monet Thornton (they/them) is an AfricanAmerican Studies teacher living in Bronzeville.

Estafany, una estudiante de enfermería de South Chicago, cuenta la historia del viaje de su familia por Centroamérica, las instalaciones de la Patrulla Fronteriza y el sistema de asilo estadounidense.

POR MONET THORNTON TRADUCIDO POR JACQUELINE SERRATOChicago ha recibido a más de 3,600 solicitantes de asilo latinoamericanos en los pasados meses. Gran parte de la cobertura de noticias se ha centrado en cómo la Municipalidad y otras organizaciones comunitarias satisfacen sus necesidades urgentes a través de campañas de donación y lo que se requiera para brindarles estabilidad a largo plazo. Sin embargo, aunque es vital reconcer estos esfuerzos, las historias personales de los inmigrantes se pueden perder en el ruido.

El South Side Weekly pudo conectarse con una estudiante que vive en el vecindario de South Chicago que emigró a los Estados Unidos en 2019. Estafany, originaria de Honduras, amablemente compartió la historia de inmigración de su familia a Estados Unidos con el Weekly

Estafany se crió en San Pedro Sula, Honduras con su mamá, papá y hermana menor. Uno de sus mejores recuerdos de niña es cuando celebraba la víspera de Año Nuevo con su familia. Disfrutaba de la tradición de pasar la noche con amigos en el parque y luego correr a casa justo antes de que comenzara el año nuevo.

Se reunía con su familia en casa donde oraban juntos como familia y compartían entre ellos las cosas maravillosas que anhelaban en el año nuevo.

Estas hermosas tradiciones se vieron opacadas por la violencia desenfrenada, la corrupción policial y la represión a la libertad de expresión en Honduras. Según la organización internacional Human Rights Watch, “el crimen organizado violento continúa afectando a la sociedad hondureña y empujando a muchas personas a abandonar el país”. Estafany y su familia fueron algunas de las personas que eligieron huir de Honduras debido a la violencia en su país.

Estafany dijo que el viaje de Honduras a Estados Unidos tomó un total de nueve días. Comenzó su viaje el 2 de mayo de 2019 en San Pedro Sula, en el noroeste de Honduras. La primera parada que hizo su familia fue en Corinto, Honduras, aproximadamente a dos horas en autobús. Corinto se encuentra en la frontera con Guatemala. Ahí, Estafany pudo pasar la aduana cómodamente con su pasaporte y sabía que “no tendría ningún problema con las autoridades guatemaltecas”.

Una vez en Guatemala, Estafany y su familia tardaron dos días en llegar a La Técnica, un pequeño pueblo que se encuentra en el Río Usumacinta, el río fronterizo con México. La familia de Estafany se hospedó en la Técnica Petén, una cooperativa agrícola y arqueológica que también sirve de hospedaje para los migrantes que buscan entrar a México.

Fue en este punto de su viaje que Estafany comenzó a temer que su familia fuera deportada a Honduras. Una vez en México, Estanfany relató, “[Dormíamos] en un hotel… teníamos mucho miedo de que [las] personas que vivían ahí nos entregaran a las autoridades mexicanas”. En los próximos días, la familia de Estanfany recorrió en autobuses más de diez ciudades antes de llegar finalmente a la frontera con Arizona. En Mexicali, México, la familia de Estafany se entregó a las autoridades fronterizas de Estados Unidos.

La familia fue llevada a la estación de la Patrulla Fronteriza de Yuma, Arizona, donde de inmediato tuvieron que entregar todas sus pertenencias y fueron separados por género. Todas las mujeres ahí estaban en un lado mientras que los hombres estaban en el otro. Todos los migrantes de esta instalación fueron alojados afuera con una pequeña cobija térmica para protegerlos de la lluvia y el frío. Por la noche, Estafany juntaba su cobija y la de su hermana para que ella estuviera más calientita.

Además de someter a las personas a condiciones de vivir difíciles, el lugar carecía de servicios básicos de salud e higiene. La hermana de Estafany tenía asma y le preocupaba que si tuviera un ataque de asma, no tendrían acceso a la atención adecuada para ayudarla.

Según Estafany, no había ni cinco baños disponibles en su lado de la instalación, donde se albergaban unas cien mujeres. Esta fue una gran preocupación sanitaria ya que ninguno de los migrantes podía lavarse los dientes o bañarse. Algunos de los migrantes habían

estado ahí por más de un mes sin acceso a productos de higiene.

Todos en esta instalación estaban esperando a que se procesara su información. Estafany dijo que los oficiales salían para llamar a las personas y recopilar información personal para su solicitud de asilo. Pero era fácil que las personas no escucharan sus nombres debido a las barreras de idioma y la mala pronunciación de los nombres, lo que llevaba a los oficiales a brincarse nombres en la lista.

La familia de Estafany también se enteró que los oficiales querían enviarlos a las llamadas hieleras. Las hieleras son instalaciones infames donde los inmigrantes se encuentran en cuartos congelados con solo cobijas pequeñas. En 2016, el tribunal de distrito federal de Tucson, Arizona, publicó fotografías de las instalaciones de la Patrulla Fronteriza de Tucson que mostraban a personas durmiendo en bancos de madera y pisos de concreto, y una mostraba a varios hombres compartiendo una cobija térmica.

Las hieleras tenían peores condiciones higiénicas que el establecimiento donde se alojaban ellas. Una persona testificó que en su cuarto “había un lavamanos pero no había jabón ni toallas. La mayoría de las personas habían pasado tiempo en el desierto y estaban muy sucias, pero era imposible lavarse las manos o limpiarse... las condiciones se volvieron repugnantes con tanta gente amontonada en una celda de esta manera”. Estafany y su familia no fueron trasladadas a las hieleras debido al asma de su hermana y la probabilidad de que tuviera un ataque.

Una vez que Estafany, su hermana y su madre dieron sus datos, pudieron contactarse con su tía que vive en Chicago. La estadía de su familia en este sitio de la Patrulla Fronteriza fue relativamente corta, permanecieron ahí tres días y dos noches antes de tomar un vuelo a Chicago el 11 de mayo de 2019. Sin tener un familiar que ya viviera en los Estados

Unidos, Estafany dijo que “la decisión de emigrar a los Estados Unidos no hubiera sido una opción”.

La familia se ha establecido en el vecindario de South Chicago, donde dice que su familia está “muy cómoda”. Pero necesitaron acostumbrarse para llegar a este punto. Señaló que aprender un nuevo idioma, la cultura estadounidense y el cambio de clima fueron sus mayores dificultades para establecerse en Chicago. A pesar de todo el cambio, Estafany dijo que estaba agradecida de tener a su familia en que apoyarse mientras navegaban todo juntas.

Desde que llegó a Chicago, Estafany se ha inscrito en el programa de Asistente de Enfermería Básica (BNA) que se ofrece en el Centro de Aprendizaje de South Chicago, un campus satélite de Olive-Harvey College. Estafany espera completar el programa de BNA para “ayudar a mi nueva comunidad y poder aportar una buena obra al país”. La familia ha tenido la oportunidad de conocer a muchos de sus vecinos y les han demostrado su generosidad. Muchos de sus vecinos las han ayudado brindándole ropa y comida, y Estafany dice que su generosidad y gracia la han ayudado a concentrarse en sus estudios.

Estafany y su familia recibieron asilo permanente en los Estados Unidos en noviembre de 2020. El proceso de solicitud de asilo no fue fácil y requirió que el padre de Estafany se pusiera en contacto con una organización de abogados que ayudaba a los inmigrantes que llegaban al país. Buscar asilo no comienza ni termina con entregarse a las autoridades fronterizas. Las personas que buscan asilo primero deben presentar una solicitud de asilo, que debe completarse dentro del primer año de la entrada del solicitante al país. En la siguiente etapa del proceso, la evaluación de credibilidad, los funcionarios fronterizos determinan si una persona tiene o no una razón creíble para buscar asilo en los EE.UU. Una persona tiene una razón creíble

para buscar asilo si “busca protección porque ha sufrido persecución o temen sufrir persecución por motivos de raza, religión, nacionalidad, pertenencia a un grupo social u opinión política”. Si se considera que no es creíble, comienzan los procedimientos de deportación y los solicitantes de asilo pueden apelar su caso a través de la Junta de Apelaciones de Inmigración.

La familia de Estafany tuvo la suerte de que su caso de asilo fue aprobado por los Servicios de Inmigración y Aduanas de los Estados Unidos (USCIS, por sus siglas en inglés). En 2021, aproximadamente al sesenta y tres por ciento de los solicitantes de asilo se les negó sus casos y fueron inevitablemente deportados a su país de origen. Según el Consejo Estadounidense de Inmigración, “en muchos casos, el incumplimiento del plazo de un año es la única razón por la que el gobierno niega una solicitud de asilo”. Navegar por el sistema de inmigración es casi imposible sin la ayuda de un abogado con experiencia en casos de asilo.

La experiencia de Estafany es solo un ejemplo de una realidad simple: no es fácil eligir y mudarse a un país completamente nuevo. En Honduras, su familia enfrentó una violencia desenfrenada que las empujó a buscar un mejor lugar para criar a su familia. Viajaron en autobús a través de Centroamérica, vivieron en instalaciones de la Patrulla Fronteriza sobrepobladas y sucias, y tuvieron que navegar el sistema de inmigración para solidificar su lugar en este país. Su batalla continúa mientras tratan de obtener su permiso de residencia. Mientras tanto, Estafany sigue estudiando en el Centro de Aprendizaje de South Chicago para convertirse en Asistente de Enfermería Certificada (CNA, por sus siglas en inglés) en medio de un éxodo de trabajadores de la salud. Su resiliencia y valentía son valores que Estafany ha demostrado y que busca difundir en su comunidad en el futuro. ¬

Monet Thornton es profesorx de estudios afroamericanos que vive en Bronzeville. Esta es su primera nota para el Weekly

BY BOBBY VANECKO

BY BOBBY VANECKO

Gangs exist where poverty exists and that’s been true in Chicago for more than a 100 years,” tweeted Lakeidra Chavis, a Chicago-based reporter for the Marshall Project, in January 2022. Chavis was writing to criticize current Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s proposal for a new law that would allow the City to sue gangs and seize the assets of anyone the Chicago Police Department (CPD) alleges is in a gang, because the law would directly worsen Chicago’s obscene levels of poverty and precarity that produce the violence in the city. However, Chavis also made the important point that Chicago gang history stretches much farther back than many Chicagoans may realize.

In a new book King David and Boss Daley: The Black Disciples, Mayor Daley and Chicago on the Edge, coming out in December, author and Northeastern Illinois University Professor Dr. Lance Williams traces the life stories of two of Chicago’s most powerful leaders: Black Disciples “King” David Barksdale and “Boss” Mayor Richard J. Daley. While Williams notes that the two never met in person, and many Chicagoans may not think of them together, Barksdale and Daley were on directly opposing sides of many of the city’s political battles throughout the 1960’s. Barksdale and Daley were both leaders of their own powerful organizations: Barksdale had the Disciples, later the Black Gangster Disciple Nation, while Daley had the Hamburg Athletic Club, and later the city’s entire Democratic machine, including the CPD.

As Williams writes in the introduction: “Behind the poverty, crime and violence, this story is about the struggle for power between two men of violence, one with a chance and a historical opportunity and one with a chance and nothing else. In the end, it is a story about the inevitable conflict between right and wrong. Black and white. And the Black inner city and City Hall.”

Through a variety of historical archives, government documents, firsthand interviews, and personal experience, Williams has created a masterful document of history that is an essential read for anyone interested in the city’s past and future. The book contextualizes the pressing issues that Chicago faces today, from the racialized structural violence that is the perpetuation of segregated ghettos and concentrated poverty offset by concentrated wealth, to the interpersonal violence that manifests in shootings.

Williams weaves the book’s narrative between the lives of Barksdale and Daley, but the story in terms of Chicago’s gang history starts with the Irish and other white ethnic gangs that were formed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These Irish gangs arose as a byproduct of the poverty and discrimination that Irish immigrants originally faced in Bridgeport— “Chicago’s first slum,” as Williams puts it— until the Irish assimilated into whiteness by

becoming police officers and politicians, among other establishment, status quomaintaining careers.

In the early to mid 1900’s, these white gangs played an essential role in Chicago’s machine politics, often using violence or the threat of violence to turn out or suppress the vote and to reinforce the city’s racial segregation. Daley was elected president of the Hamburg Athletic Club in 1924 at twenty-two, and he had been a member of the group since his early teen years. He was seventeen in 1919, when the Hamburgs were heavily involved in the deadliest antiBlack race riot in Chicago’s history. Williams portrays the events that started the race riot in tragic detail—including the death of Black teenager Eugene Williams at the whitesonly 29th Street Beach, and the police collusion and inaction that contributed to the chaos that reigned in the city for weeks.

Chicago’s history with Black street gangs generally started later into the twentieth century, and those groups were

often first created as a form of protection from attacks by the city’s white gangs and the police. In fact, some of the city’s racist white gang members became police officers later in life, as they aged out of the gang—part of the city’s Democratic Machine and its infamous patronage politics, a system where city jobs were exchanged for political support.

Both the white gangs and the police played, and continue to play, a key role in reinforcing the city of Chicago’s racial boundaries. To this day, the city remains one of the most segregated and heavily policed in the world, with more police per capita than almost any other US city other than New York. Yet Mayor Lightfoot and many City Council representatives advocate for even more police as a solution to the city’s violence and the poverty that produces it.

David Barksdale was born to Virginia and Charlie “Rainy” Barksdale, Jr. on May 24, 1947 in Sallis, Mississippi. The Barksdales were sharecroppers in Mississippi, and they were not able to afford to move to Chicago until 1958—three years into Mayor Richard J. Daley’s first term. The Barksdale family first moved to Bronzeville, the city’s Black economic and social hub, until large parts of it were cleared as part of the city’s “urban renewal”—or as Williams writes, “Negro removal”—which displaced the family to Englewood, to make way for the new expressway that, like the projects, was built to segregate Black and white Chicagoans.

David Barksdale had a rough and impoverished childhood, and he was kicked out of his house by his father when he was just fourteen as a result of his disobedience. David was known early on in his life as a great boxer, and he was never afraid to defend himself when challenged. Barksdale was first sent to the “Audy home,” the city’s jail for children, at the age of just sixteen.

As the city’s population of poor Black people grew, so did the police budget and

presence in those neighborhoods, which led to youth like David being frequently criminalized, harassed and arrested by the CPD. There was an eightfold increase in Chicago’s Black population from 1910-1940 during the first Great Migration, and the city’s white power structure was determined to protect their segregated turf and wealth. Throughout the middle part of the century, Chicago’s Black population grew again from 8.2 percent to 32.7 percent. At the same time, from 1945 to 1970, the city’s police budget grew 900 percent and the CPD more than doubled the number of cops on the streets.

Black youth growing up on the South Side knew not to trust in or talk to the police, which remains justifiably true to this day. Williams details the robbery, extortion, harassment, torture, frame-ups, abuse, racism, shootings, and straight-up murders that Chicago police perpetrated on the city’s Black communities throughout the entire period of the book, from before 1919 to around 1972.

In the early 1960’s, David Barksdale started to lead around a group of youth from his neighborhood called the 65th Street Boys, in order to protect himself and his

friends from racially motivated attacks— such as the 1957 murder of Black youth Alvin Palmer by white gang member Joseph Schwartz in Englewood. Chicago police and politicians were doing nothing substantial to stop these racist murders and assaults, and in some cases actually colluding with white gangs in facilitating and covering up the attacks, so Black youth like David had to figure out a way to defend themselves.

In 1963, after Barksdale’s time in the Audy home where he encountered other gangs, he and his friends decided to create a more structured gang called the Devil's Disciples. The group did not become the powerful Black Gangster Disciple Nation until years later, when they grew and merged with Larry Hoover’s Supreme Gangsters during the peacemaking that was encouraged by the Black Power movement. However, in the early days of the Disciples (they quickly dropped the “Devil” from the name, largely because David didn’t like it), they proved themselves to be among the best boxers in all of the South Side. They had to be, in order to defend themselves against rival Black gangs like the Blackstone Rangers, and white

gangs determined to defend their territory, including the Chicago Police Department, in Williams’ words.

The most crucial parts of the book take place in the 1960’s during the Chicago Freedom Movement with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the Black Power Movement, and the Illinois Black Panther Party. This is where the conflict between “King David and Boss Daley” becomes the most pronounced.

Williams writes: “Mayor Daley had always been concerned about Black street gangs. But his concern wasn’t about them killing one another in their endless gang wars, nor was it about them terrorizing their communities. The mayor’s biggest concern was that Black street gangs like the Disciples had now added branches numbering several thousand and were starting to show signs of political and economic awareness.”

Daley’s own gang had moved from fighting in the streets to politics and power, and now he was worried the “young, tough Black males could be dictating who their Alderman would be if he didn’t stop them.” Daley felt especially threatened by

the Black Panthers, “a more sophisticated, if smaller group” who were perceived to be even more dangerous than the gangs due to their revolutionary politics. Williams writes, “The Disciples and the Black Panthers had set up a free food program in the ghetto and had opened a health clinic that was superior to those of his own health department.”

Consequently, in 1967, Daley and the CPD leadership created the “Gang Intelligence Unit” to disrupt the political organizing of the Disciples, Stones, Panthers, and other like-minded groups. Daley’s next move was to hold a conference to attack the Black gangs in the eyes of the voting public. As Williams observes, however, “the meeting never acknowledged that youth crime was mainly a product of the evils in society like poverty, discrimination, and other unrighted wrongs. There was no mention of any of the positive efforts of these groups, like their attempts to have truces, job training, civil protest, and the like. They never offered solutions to help guide young people seeking constructive opportunities. It only focused on their socalled criminal activities. The mayor and the city agencies present never discussed its

responsibility to aid such groups.”

Williams writes that, once Daley had sufficiently demonized the Black gangs, CPD ramped up their repression— especially when it came to the Black gangs’ political organizing. Several of the city’s largest gangs had called truces—such as the Lords, Stones, and Disciples (LSD) coalition—and they had done so in order to fight their real enemies in the city’s primarily white power structure, instead of fighting themselves. This was simply unacceptable to the CPD, who fought to sow discord between the gangs, in order to make it easier to incarcerate gang members and to justify the CPD’s own exorbitant funding and demand even more money from the city. As prominent Blackstone Rangers leader Mickey Cogwell told a reporter from the Atlantic in 1969: “the [CPD’s Gang Intelligence Unit]—black men—use the Rangers and the rivalry between us and the [Disciples] to make their work more important to the system."

When Barksdale and the Disciples started a free breakfast program with the ultimate goal of ending poverty and hunger in Englewood, and leading protests against

police brutality and discrimination— alongside their former rivals—Daley and the police ramped up the repression even further. Williams details the police attacking and breaking a strike when Barksdale and the LSD coalition protested against racial discrimination in hiring at city construction sites. Through subordinates, the Daley administration even denied that there was such discrimination in hiring, just like they denied the fact that there was slum housing in the city of Chicago when Martin Luther King Jr. came to town to protest those very slums. Substandard, overpriced housing, and a lack of building management services still affects many communities on the South and West sides today.

However, despite Daley and the police’s demonization of Black gangs, many people in Chicago’s Black communities knew their real enemy—and it wasn’t their sons, cousins, nephews, grandsons, and other family members who were associated with gangs. Even when someone was killed by another person within the community, blame often fell on city leadership for creating the conditions that produced the violence, which remains justifiably true to this day.

Williams writes about the murder of Katie Stallworth in the Robert Taylor public housing projects: “The people of the projects knew that a person murdered Stallworth, but they blamed the ‘white power’ structure of Chicago, from the mayor’s office to the elected officials who had seen fit to designate certain areas in which to concentrate public housing. From the beginning, there was talk of the projects being the means to contain the Black population. It was widely known that wherever there is a dense concentration of people in a limited area filled with smoldering resentment, frustration, and despair, such crimes such as this and others will continue to happen.”

When David Barksdale and the LSD coalition continued to press on with their civil rights activism alongside the Black Panthers, the police escalated their repression even further. Even though the gangs had called truces, their growing politicization made them dangerous to the discriminatory status quo, so the CPD attempted to break up those truces—despite the fact that they were fostering peace for a time. As Professor Toussaint Losier has written elsewhere, “the

LSD coalition represented an attempt not only to win living wage employment and broader social transformation but also to work through each gang’s internal divisions by pursuing a vision that placed Black Power over gang empowerment.” However, Daley and the rest of City and police leadership did not want any social transformation along the lines of what the Black Power movement advocated. Consequently, Daley’s protege, Edward Hanrahan, became Cook County State’s Attorney in order to continue to go after the Black gangs and the Black Panthers, and he was given his own CPD unit to do so.

Most infamously, working with the FBI, State’s Attorney Hanrahan’s CPD unit murdered Illinois Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton and Peoria chapter founder Mark Clark on December 4, 1969. The same day as this assassination and subsequent coverup, prominent LSD leader and Black P. Stone Nation member Leonard Sengali was arrested for a crime that he did not commit and pressured to testify against fellow LSD members and other civil rights activists. Bobby Gore, spokesman for the Conservative Vice Lords

and another LSD leader, was similarly arrested on murder charges despite claiming innocence. Several other LSD members and Black Panthers were similarly arrested on fabricated and trumped-up charges and pressured to testify against each other.

Black Gangster Disciple Nation leader Larry Hoover was later arrested and sentenced to 100-200 years in prison for murder, contributing to the fracturing of the Nation into the Black Disciples and the Gangster Disciples—which was made worse by David Barksdale’s death from kidney failure in 1974, and still persists to this day.

By 1972, Mayor Daley, State’s Attorney Hanrahan, and the CPD had defeated the Black gangs and the Black Panthers, at least in terms of their ambitions for political power and civil rights gains, such as the ending of poverty and segregation in Chicago’s Black communities. The Black gangs still persisted—as they do today, despite the persistent efforts of CPD to eradicate them—but the gangs fell into different rivalries and factions amidst the decades of worsening violence, poverty, disinvestment, deindustrialization, gentrification, privatization, school

and mental health facility closings, and continuing police brutality and mass incarceration, among other factors.

The “War on Gangs” approach to interpersonal conflict still persists to this day in the city of Chicago, because it was continued by subsequent mayors such as Richard M. Daley, Rahm Emanuel, and now Lori Lightfoot. As Bella Bahhs has written for the Triibe: “Today, when violence in Black and brown Chicago neighborhoods is categorized as ‘gang related,’ it absolves the city officials from taking responsibility for constructing racial ghettos and designated pockets of poverty.” Policing and mass incarceration are then presented as the only possible response to interpersonal violence, because structural change—such as ending poverty and segregation—is unthinkable to the people in charge of maintaining the discriminatory and violent status quo.

These are all the policies that make up the “organized abandonment” of racial capitalism and the “organized violence” that it takes to enforce capitalism’s inherent racialized inequality, in the words of abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore. These apartheid structures created gang wars

and cycles of violence that are exceedingly difficult to resolve—especially with the easy availability of guns in America, the world’s leader in arms dealing, military and police spending, and incarceration. Tragically, these cycles of violence will likely persist as long as the conditions that produce such violence still govern the City of Chicago and the country: including entrenched segregation, poverty, widespread police abuse and incarceration, and widespread availability of guns.

Williams has written an essential document of history that explains how Chicago got to where it is today. Whether you are interested in political history, gang history, or just the city in general, King David and Boss Daley: The Black Disciples, Mayor Daley and Chicago on the Edge is one of the best books out there. While it is a tragic story filled with lots of death and oppression, it is also a story of perseverance and ingenuity in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, and it deeply resonates today. Black youth and especially Black “gang members” continue to be the most demonized population in the City of Chicago, and that fact can be traced directly

to the events portrayed in this book.

Several decades of heavy-handed policing and mass incarceration have proven to be completely unable to eradicate gangs or resolve the problem of interpersonal gun violence. As Williams and others have written for the Chicago Reporter, Chicagoans should “reconsider the ‘war on gangs’ strategy that has been Chicago policy since it was declared by Richard J. Daley in 1969.” There will only be peace when the people in charge of the city of Chicago, and the nation, make transformative structural changes to how the city and country operate; such as passing the PeaceBook ordinance, ending poverty and segregation, and divesting from the massive policing, incarceration, and military budgets to facilitate investment in true community resources like education, housing, healthcare, and much more— including Reparations for the historical and present harm caused. ¬

Bobby Vanecko is a contributor to the Weekly, and is the great-grandson of Richard J. Daley. He previously wrote about this family connection in 2020.

The Exchange is the Weekly’s poetry corner, where a poem or piece of writing is presented with a prompt. Readers are welcome to respond to the prompt with original poems, and pieces may be featured in the next issue of the Weekly.

“Street Cleaning” is a myth. i know this, because i hosted a show and at that show, my friends partner brought us snacks and stuff for the green room, things from Trader Joe’s. Fruit Snacks. Drinks I went and picked this stuff up from her before the show and then i brought it to the venue and i put this stuff in the green room and unpacked everything, lined it up all neat, put a few in the performers dressing rooms. i didn’t really eat any though so at the end of the show, when we were packing up to leave i grabbed a few things, one of those things was a can of pineapple juice it was the last one. everyone said it was great, and that i deserved it, the last one. so i put it in my bag. and went to my car. and drove home and parked on my block. and while i was juggling all the things i had my pineapple juice rolled out of my bag onto the sidewalk. and then slipped slightly under my car and it was December and the ground was gross and i was exhausted and it was like midnight and i was really looking forward to drinking it and i’m an environmental studies minor so before you say shit to me about littering i was carrying so many things so i left it. there. and slammed my car door closed with my butt and went inside. yesterday. i happened to park in the same spot. mind you, it’s March. the can of pineapple juice was flat as Florida rusted. still at the edge of the curb just beneath the sidewalk unmoved. so i would like to contest every ticket i’ve received for parking on a street that y’all claim you’re about to “Clean.” this is not a poem. this is a draft letter to the Mayor's office please let me know if it sounds good. thanks.

Featured below is a reader response to a previous prompt.

Distract me with your intoxicating ambiance. Bury me in your flaws and inspire me with your strengths.

Color me with kisses and let your whispers wash over me.

Until your stories and secrets are as familiar as my own, And the outline of your body is engraved in me like stone.

So that I don't notice your tangled roots suffocating me when they crave for more Or the treatment you give when you're feeling poor.

Our love changed like the seasons And we part with our own reasons

This time together has been wrung dry. Even if our hearts resist the goodbye.

Please leave me to heal, tucked away in my room So one day a new love can bloom.

Chima Ikoro is the community organizing editor for the Weekly

This could be a poem or a stream-of-consciousness piece. Submissions could be new or formerly written pieces. Submissions can be sent to bit.ly/ssw-exchange or via email to chima.ikoro@southsideweekly.com.

BY JHAYLIN BENSON, GRACE DEL VECCHIO, ANNABEL ROCHA, SONAL SONI, JERREL FLOYD AND CITY BUREAU

BY JHAYLIN BENSON, GRACE DEL VECCHIO, ANNABEL ROCHA, SONAL SONI, JERREL FLOYD AND CITY BUREAU

This story was originally published by City Bureau on November 2, 2022 and copublished by the Chicago Reader.

For the last century, housing cooperatives have provided residents of major American cities increased opportunity for homeownership— especially for low-income and lowermiddle-class residents for whom homeownership may not be financially feasible.

Some of Chicago’s first co-ops were created in South Shore, a community that in recent years has seen a sharp uptick in evictions. Community members have pushed for an increase in affordable housing as well as policies and programs to help South Shore residents remain in the neighborhood.

In July, the city approved a pilot program that will provide loans and grants to condo and co-op owners living in multi-unit buildings in South Shore and whose homes need repairs. The pilot program was created after years of pressure from local leaders, housing advocates and residents who feared displacement and wanted housing protections ahead of the Obama Presidential Center’s opening. Though the program is a welcome resource, many of the organizers’ demands have yet to be fulfilled.

City Bureau reporters surveyed more than a dozen South Shore residents about their views and feelings on housing coops, as we explore whether they could play a bigger role as an affordable housing solution. We learned that there is a lot of confusion about what co-ops are. Below

How are housing cooperatives different from communes and who are they for?ART BY DAVID ALVARADO FOR CITY BUREAU

we answer some of the most common questions. Later this year we’ll publish a more in-depth report on co-ops in Chicago.

From the outside, they look like any other home in Chicago. They can be townhouses, a collection of buildings or a large apartment complex with hundreds of units. A housing cooperative is essentially an entity that “owns real estate, consisting of one or more residential buildings” according to the International Cooperative Alliance, an organization that helps raise awareness about cooperatives around the world.

From the inside, housing co-ops may look different. The financial structure and agreements between residents regarding responsibilities, building maintenance and use of common areas can be targeted to the needs of the members. Some co-ops are organized to support people based on their income level, background, political ideology or immigration status.

Many co-ops face obstacles that can stem from different members having different visions for the space, or financial challenges raised by needed renovations and updates.

While there are several different financial models for establishing a housing co-op, zero equity, limited equity and market rate co-ops are some of the three most common models in Chicago.

Zero equity: Individual members of the co-op do not have any ownership in the property. Instead, ownership is handled by a group usually outside of the actual co-op building. So typically the members will not make a profit if they decide to leave the coop.

Limited equity: Individual members only own a portion of their unit in the building where the co-op is located. The other portion is owned by the cooperative as a whole. This structure is typically seen as an option for people of limited income to reach a form of home ownership, while also helping them build wealth.

Market rate: The units in the co-op can be sold at market value, with each member owning the entirety of the unit. When selling the unit, members receive full market value. This model provides an alternative route to home ownership for

those who cannot go the traditional route.

Limited and zero equity co-ops were created to make housing co-ops more accessible to lower-income people and families. By limiting or eliminating the value increase on the property, the co-op members ensure that their cost of living remains the same or nearly the same.

on the budget together and might divide maintenance work. Every decision also takes both individual and collective benefits into account, and each member has an equal say in the co-op’s housing guidelines. There are also opportunities for members to take part in leadership positions, like on a committee or the board of directors.

How is this different from a commune?

outsource a building manager to handle administrative work or other duties around maintaining the space. But you are their boss.

The first housing cooperatives in Chicago were built in the 1920s, situated along the northern and southern shores. Many were owned by upper-middle-class white residents who wanted to enjoy home ownership at a cheaper price and “handpick” their neighbors, as a 1927 Tribune article stated. In contrast, one of the biggest selling points for cooperatives in recent decades is their potential to accommodate residents of a variety of economic standings (zero equity and limited equity co-ops in particular meet this need).

The down payment, or “initial share” payment, varies depending on the co-op and whether they are market rate, limited equity or zero equity. Co-op members do pay monthly fees, which are used for the mortgage, property taxes, shared utilities and repairs. But those fees tend to be lower than those incurred by homeowners. The average, initial-share fee for a one-bedroom affordable housing co-op is roughly $4,600, and about $12,000 for two- or threebedroom units, according to a Chicago Mutual Housing Network 2004 report, the most recent available. However, some coops receiving federal subsidies may require the equivalent of a deposit or a month’s rent.

What decisions can you make in a cooperative? How much say do you have?

Housing cooperatives embody democratic principles, according to “Cooperative Housing Toolbox: A Practical Guide for Cooperative Success” by the Northcountry Cooperative Foundation. Co-ops might use different governance models, but most have individual members, a board of directors and committees, and they primarily use the “one member, one vote model.”

In most housing co-ops, members collectively decide on policies, approve new members, and choose whether they want a management company. Members also work

Similarities: Both communes and housing cooperatives are types of communal living where a group of individuals typically live in a shared house or property.

According to the Foundation for Intentional Communities, both communes and housing cooperatives may use a cohousing model. Chapeltown Cohousing explains that in this approach, communities often include both private dwellings and shared facilities, like a common house or garden, and they foster neighborly connections. Some housing co-ops operate with shared living spaces whereas others only have separate and private units.

Differences: Unlike housing cooperatives, communes may combine each member’s income for additional shared expenses like groceries. People who live in a commune may also share work responsibilities like cleaning, cooking meals, and childcare.