ISSUE NO. 19 FALL 2022

2 spark

Issue No. 19

Lasting forever, never to be forgotten; immortal.

editor in chief kai-lin wei managing editor walter naranjo

design director juleanna culilap

layout director jaycee jamison assistant design director charlotte rovelli assistant design director melanie huynh digital director maddie abdalla

creative director alex cao assistant creative director laurence nguyen-thai

director of hmu yeonsoo jung assistant director of hmu lily cartagena assistant director of hmu meryl jiang

modeling director maliabo diamba assistant modeling director jillian le assistant modeling director yousuf khan

photography director rachel karls assistant photography director mateo ontiveros

director of styling david garcia assistant director of styling vi cao assistant director of styling miguel anderson

editorial director amelia kushner

senior print editor eliza pillsbury associate print editor kunika trehan associate print editor carolynn solorio assistant print editor ella rous

senior web editor kyra burke associate web editor sonali menon associate web editor ellen daly assistant web editor renata salazar

business director jackie fowler

director of events nereida jimenez assistant director of events sarai lazo social media director elain yao assistant social media director olivia abercrombie marketing director emely romo assistant marketing director brenda chapa

staff

noura abdi, mariana aguirre, amani ahmad, elena ahsan, brandon akinseye, john alvarado, sophia amstalden, shreya ayelasomayajula, rachel bai, ava barrett, bridget beecham, leah blom, lea boal, aaron boehmer, chloe bogen, lara borges, ren breach, emma brey, charlotte brown, ellis brown, jordan busarello, jackie bush, jaedyn butler, leilani cabello, stacey campbell, colin cantwell, via ceaser, katie chang, hayle chen, morgan cheng, camille chuduc, caroline clark, allison clark, grace dahl, audrey dahlkemper, lily davis, ale de la fuente, jessi delfino, jesus del real, kenneth delucca, nysa dharan, wenting du, gabrielle duhon, saturn eclair, seth endsley, annahita escher, alexandra evans, nia franzua, belton gaar, megan gallegos, liz garcia, julia garrett, emma george, emily gift, nico grayson, alisha gupta, shareefa gyami, dylan haefner, jereamy hall, j hayden, lissie hill, stephanie ho, paige hoffer, haley hsu, angel huang, tyson humbert, rhionna jackson, ava jiang, jeffrey jin, kameel karim, sriya katanguru, payson kelley, joanne kim, grace kimball, neha kondaveeti, divya konkimalla, tyler kubecka, vyvy le, justin le, amy lee, sunshine (sunny) leeuwon, ryan levin, luci llano, lauren logan, fernanda lopez, omar lopez, estelle omotayo, chloe low, sophia lowe, juniper luedke, enrique mancha, olivia marbury, evelyn martinez, olivia martinez, emily martinez, giulia mayhua pezo, ada mcclure, safa michigan, amanda miller, noa miller, pebbles moomau, arliz muñoz, miu nakata, theresa nguyen, miles nguyen, maya nguyen, allison nguyen, esha nigudkar, jake otto, bryn palmer, liesel papenhausen, claire philpot, genesis pieri, ainsley plesko, athená polymenis, angel quinn, tarsus rao, anagha rao, reagan richard, joy richardson, stela riera-vales, lily rosenstein, caitlyn ruiz, claire schulter, vani shah, nikki shah, sonia siddiqui, presley simmons, peyton sims, isabel sitar, saejun smith, caroline st. clergy, ellie stephan, victoria sturm, tiffany sun, lianne sung, summer sweeris, amelia tapia, leah teague, rachel thomas, nhi tieu, anh tran, jacob tran, princeton tran, vy truong, claire tsui, olivia tudor, emily wager, averie wang, eileen wang, rhys wilkinson, lorianne willett, melat woldu, megan xie, miranda ye, moises zanabria, isabella zeff, sophie zhang

4 spark

from the editor

This issue is a collection of speculative tomorrows — good ones, bad ones, ones that stir the heart or electrify the mind, and ones beyond our wildest dreams. Some are hellscapes hunting us for retribution, while others are paradises designed to satisfy our every whim and fancy.

In 2022, we occupy a troubled place in history, where amid socio-political upheaval and continued environmental crisis, it can feel like the very soul of the earth is slipping from our grasp. The world is changing. We feel it shifting beneath our feet and hanging heavy in the air, flashing its warning to us.

As staff writer Bridget Beecham writes: “Time is running out. Beauty is running out.” (pg. 186) At the same time, this is an era of unprecedented technological progress. The internet is realer than real life; shiny new things continue to get shinier and newer; our advancement as a species seems to know no bounds.

What does it mean to live in a time where the world as we know it is both dying and being born again? What power do we hold over the future? And what power does the future hold over us? These are the central questions sitting at the heart of Deathless. In this issue, we explore them over the course of three chapters: Man, Spirit, and Machine.

We’ve also made exciting additions to enhance your reading experience, including a series of short films, a companion podcast featuring feature story subject Austin rapper Mama Duke, and the first installment of work by M.E.D., SPARK’s inaugural design technology team spearheaded by Creative Director Alex Cao. All this and more can be found at sparkmagazinetx.com.

We elected to elevate our issue theme this season by designing a conceptual world for our staff to explore, with a sharpened focus on issue cohesion and thematic complexity. We challenged everyone to ideate, create, and execute within the parameters of this world, and I’m proud to say that they’ve risen to the occasion by delivering a body of work that is as whimsical as it is macabre, as cohesive as it is original, and as true to SPARK’s long-standing values of innovation and creativity as it is expectation-defying.

Sincerely,

Kai-Lin Wei Editor In Chief

5 deathless

MAN windows vi naturae a world where no one dreamed terra nullius god’s creations chip to chip, heart to heart love under surveillance love in the time of cybernetica <3 biodebauchery in situ sisyphus attends our exequies.

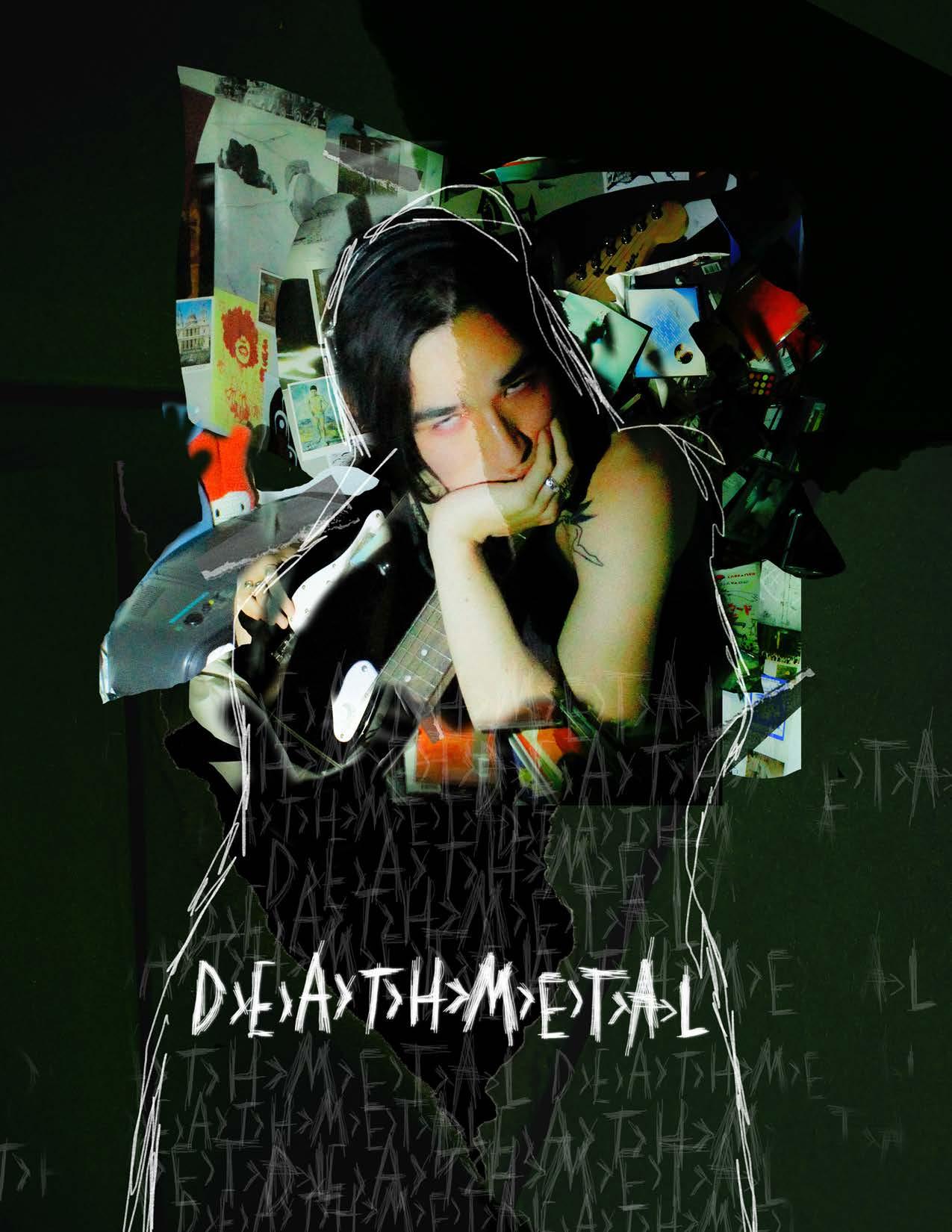

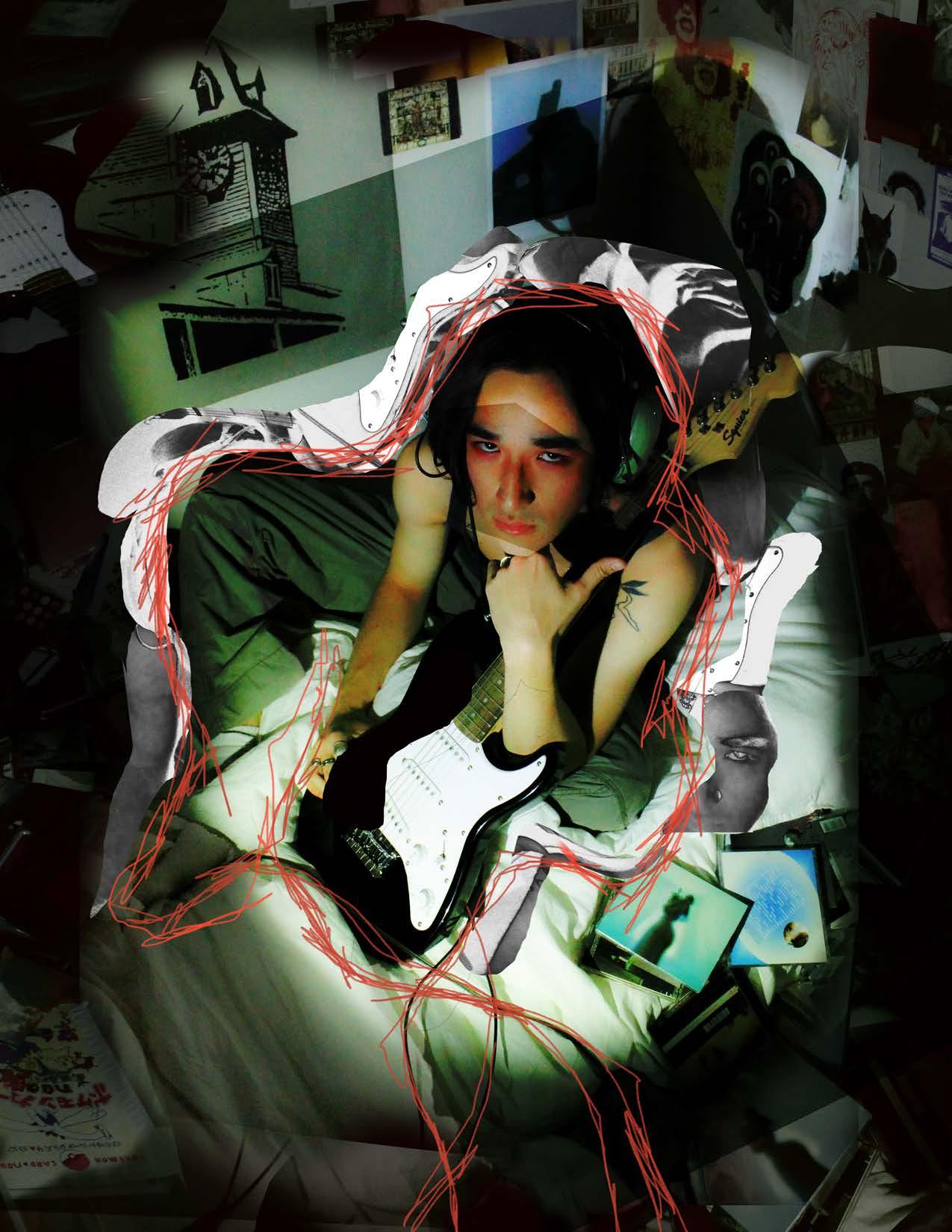

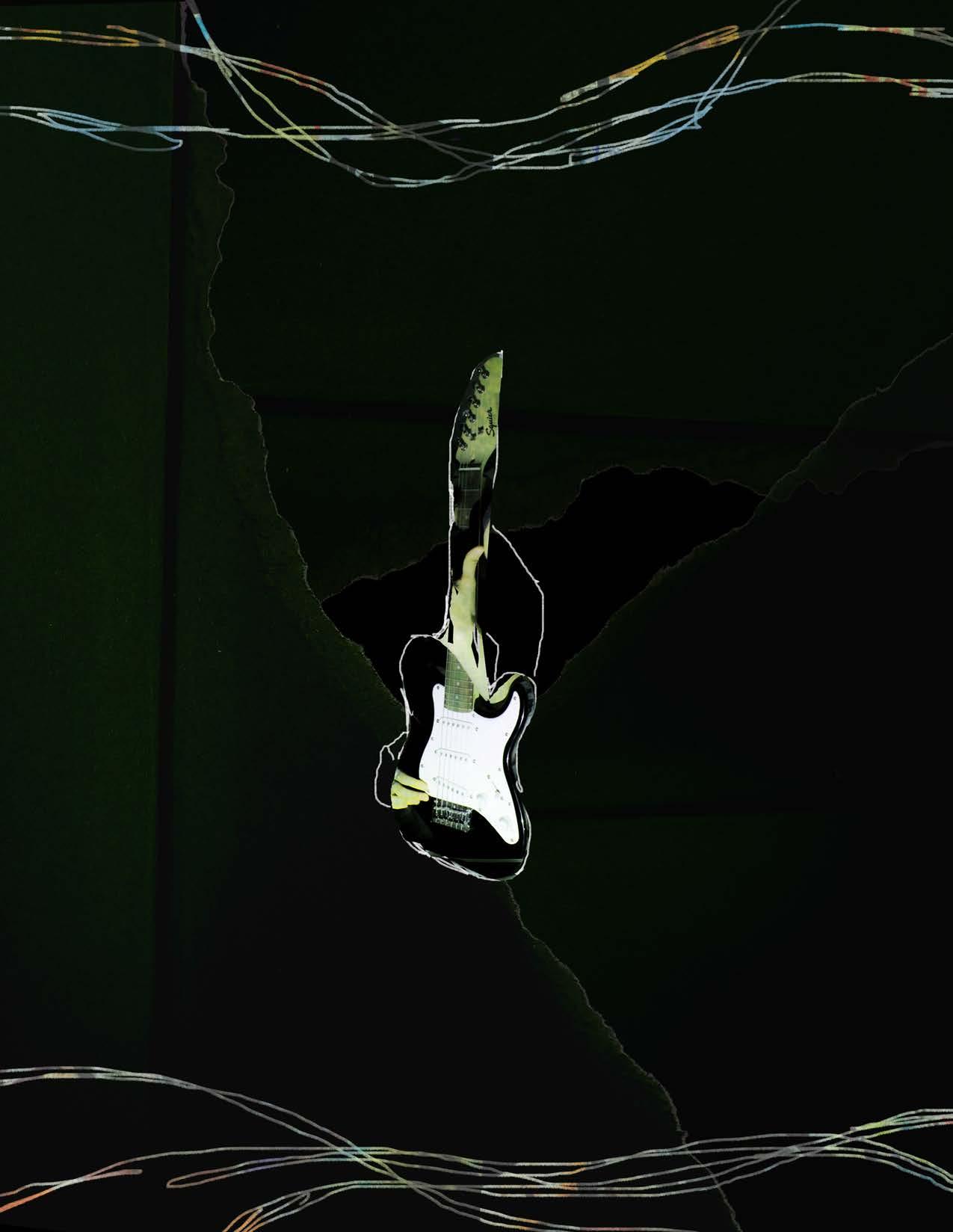

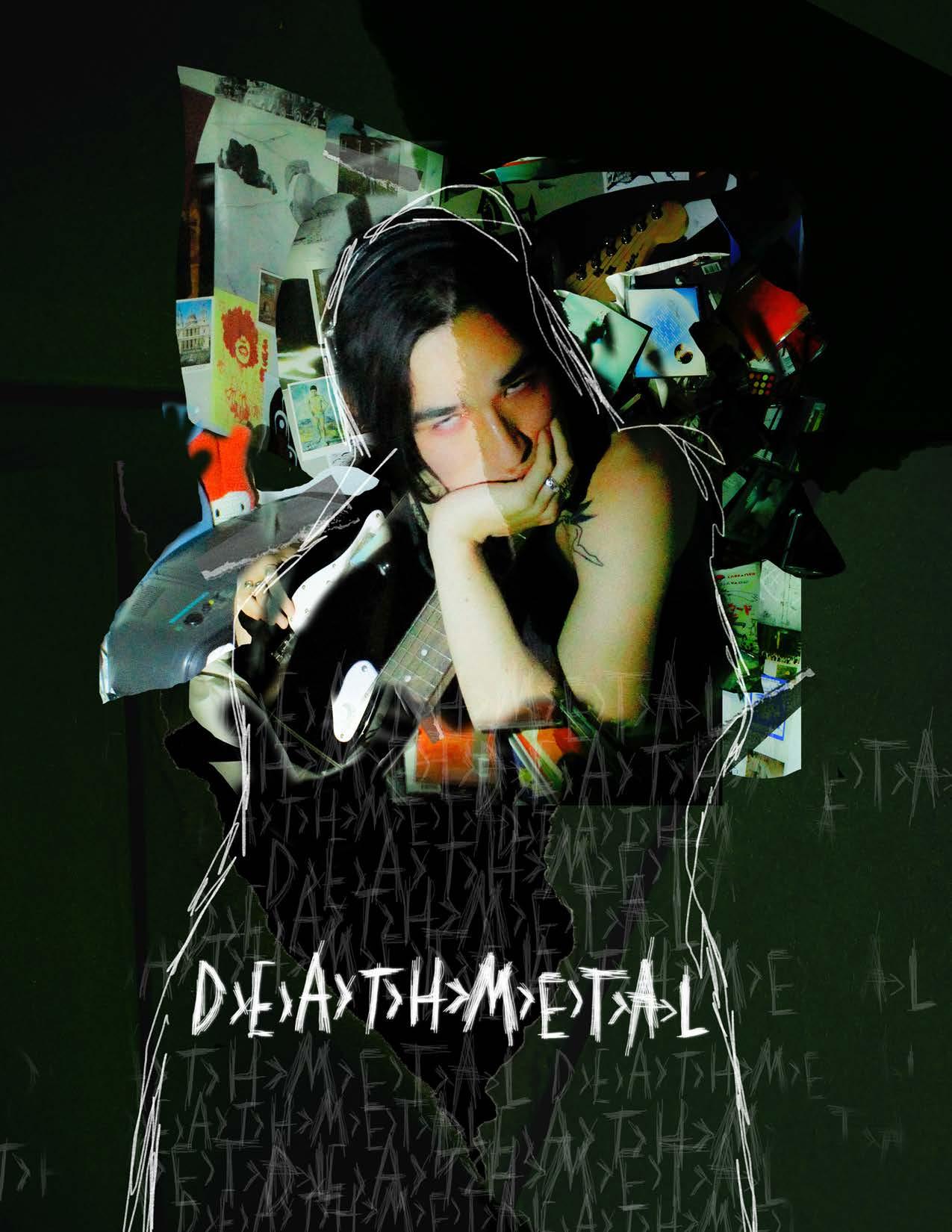

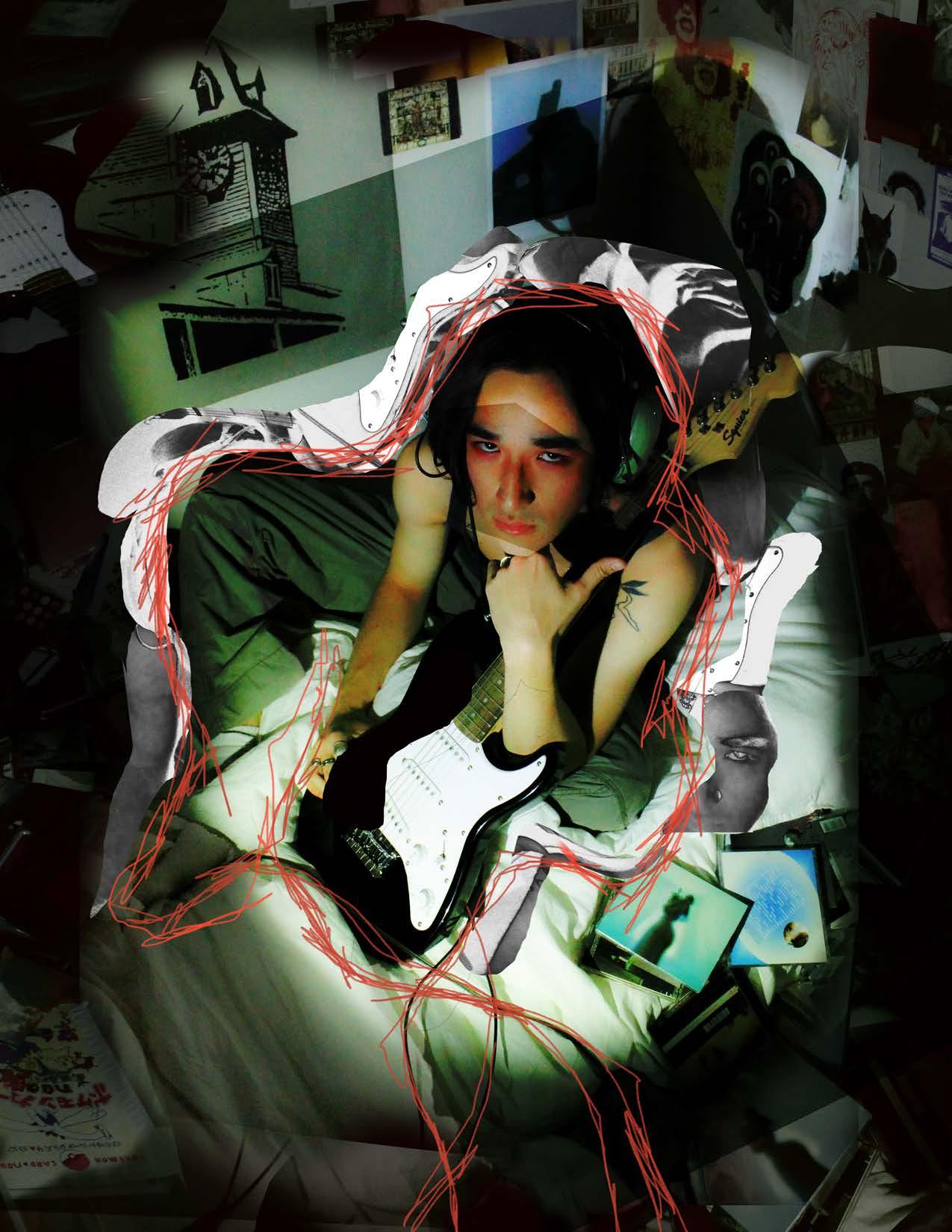

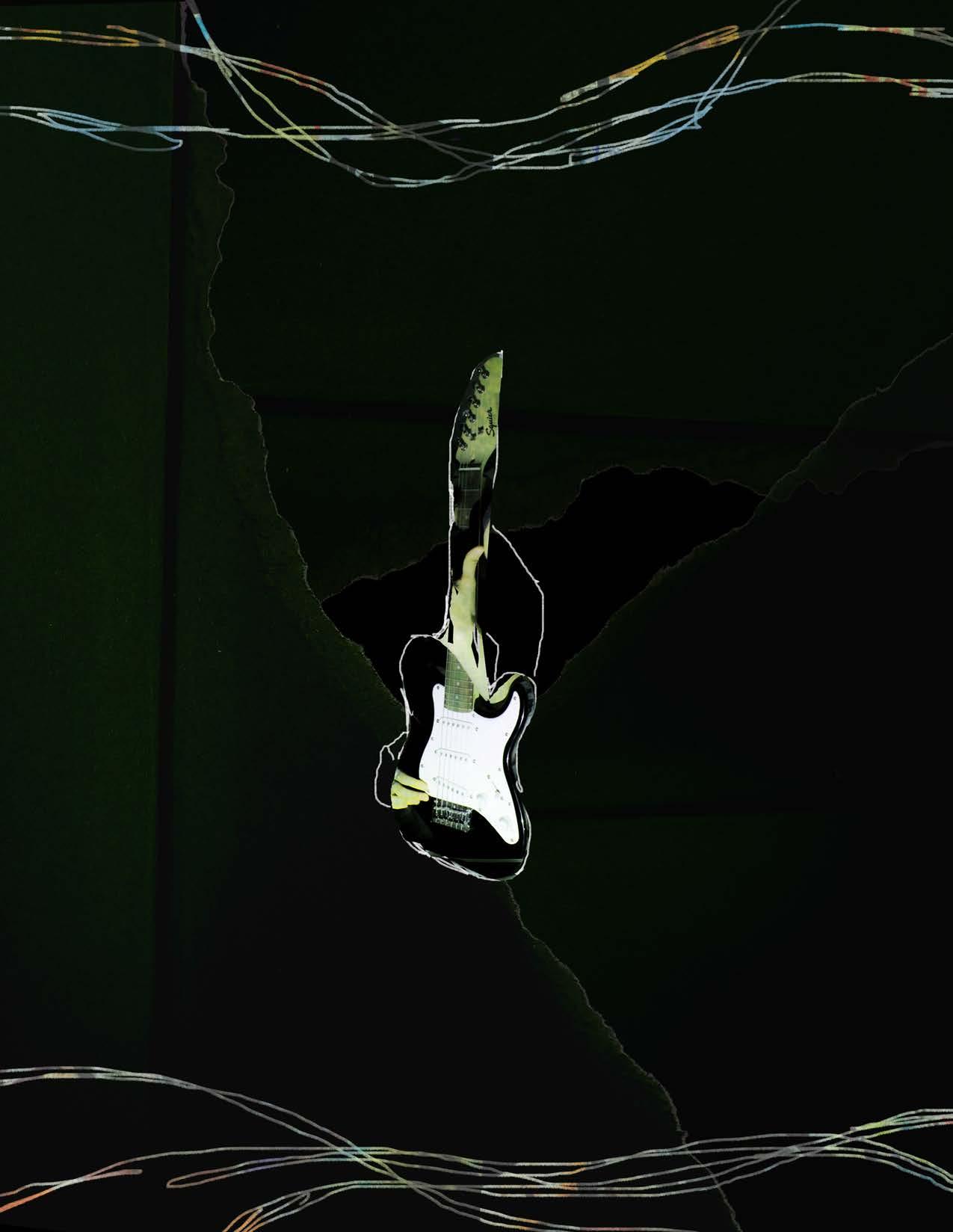

SPIRIT umbra the sound & the silence exoskeleton shatter the spirit forever & always, willie pearl from the ether d>e>a>t>h>m>e>t>a>l the heart of the poet death doulas & slowburn endings

contents

6

10 18 24 34 40 44 50 56 62 68 76 80 90 96 104 114 120 126 132 148 154 spark

issue no.

deathless

MACHINE art by machine subservience the digital playground of a generation through these red eyes cyber cash femme fatality optics the anatomy of the asian cyborg head in the cloud screen share turn-off_the_engine_

FEATURE mama duke: how did we get here?

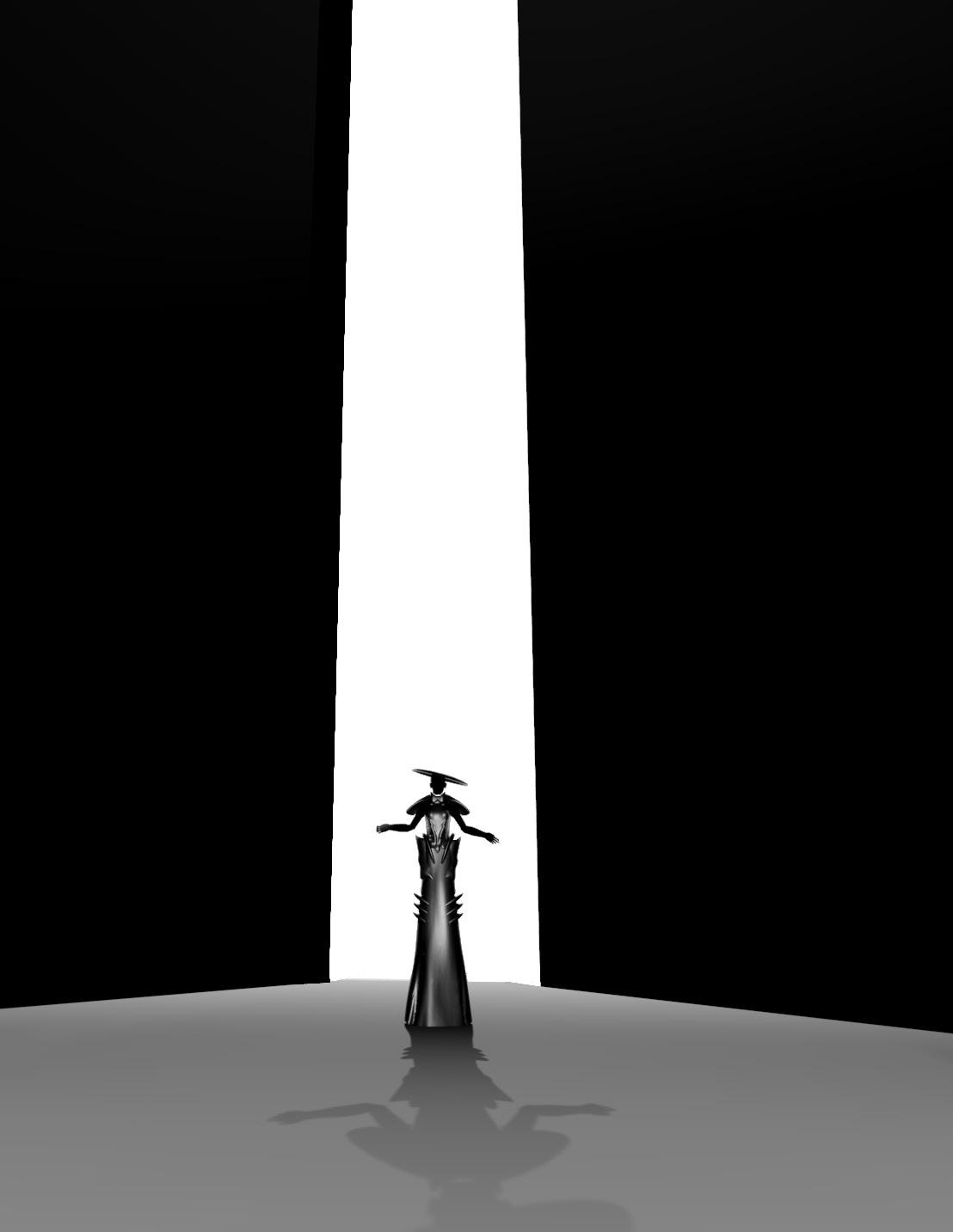

M.E.D. biophilia exostosis monolith

spark magazine

19

170 178 186 195 204 210 218 222 230 238 246 140 164 166 168

deathless 7

WINDOWS / VI NATURAE / A WORLD WHERE NO ONE DREAMED / TERRA NULLIUS / GOD’S CREATIONS / CHIP TO CHIP, HEART TO HEART / LOVE UNDER SURVEILLANCE / LOVE IN THE TIME OF CYBERNETICA <3 / BIODEBAUCHERY / IN SITU / SISYPHUS ATTENDS OUR EXEQUIES.

I. MAN

Man has creative instinct. In the face of destruction, out of a misplaced fear of the other, we fashion false comforts: religion, philosophy, love. But without this evidence of our existence, out living our fallible form, what makes us human? We forge our own fate — and at our own risk.

9 deathless

spark 10

layout MELANIE HUYNH photographer TYSON HUMBERT stylist SUMMER SWEERIS set designer CAROLINE ST. CLERGY hmua LILY CARTAGENA model LAURENCE NGUYEN-THAI videographer ATHENA POLYMENIS

WINDOWS WINDOWS

by KATIE CHANG

by KATIE CHANG

AS WE TURN TO DIGITAL NATURE, WHAT HAPPENS TO OUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE REAL, PHYSICAL THING?

My family never flies.

We’re the road trip type. The camping and eating freeze-dried spaghetti kind of family. We drive for hours and hours on end, and I rotate between scrolling on my phone and staring out the win dow as one version of White Sands blurs into the next, on and on and on. The landscape seems to unfold endlessly — it feels like we’re making no progress.

There are 473k more pictures under #whitesands. I guess we aren’t.

zzz

For about 95% of our species’s existence, we survived as hunter-gatherers, in tune with the natural world. We knew we were at the mercy of nature’s order and calculated our every action ac cordingly. We followed the ebb and flow of the seasons, navigating the land with the intent to survive — just as other species did.

At some point, some luck-of-the-draw combina tion of factors (a shift in environmental patterns, a larger brain, and a big toe, perhaps?) allowed for the development of agriculture, and from there, our relationship with nature changed. It was no longer something we were both a part of and subject to. We could interrupt the natural seed dispersal process to get more wheat! We could fence up a group of pigs to have readily available meat! Nature became something to dominate, something to control to fulfill our needs.

As mud villages turned into concrete cities and human labor turned into mechanization, the same regard for nature that enabled our mastery of agriculture sowed the seeds of capitalism. Our wheat dispersal hack is now a billion-dollar fertil izer industry. Our pig pen is a trillion-dollar meat market. From the comfort of our leather desk chairs in our glass high-rises, we’ve cemented our role as nature’s puppeteer, and in doing so, we’ve sucked the life out of Earth’s soil and ripped apart its atmosphere.

Yet, somewhere deep within our psyche, we know we’re missing something. Somewhere not yet poisoned by the gospel of economic growth, our primordial affiliation with nature survives.

12 spark

13 deathless

WE KNOW WE AREN’T AT THE MERCY OF THE NA TURE WE EXPERIENCE BECAUSE WE CREATED IT ALL— IT’S UNDER OUR CONTROL.

“ “

So, to recreate what we have destroyed, we turn to technology. “Digital nature.” Virtual reality is on the rise. Video games featuring mythical woods and majestic mountains are more popu lar than ever. We can experience an outdoor run via an indoor treadmill. We can explore pristine beaches and luscious forests via #nature.

And the best part? We get to create it all our selves. With cameras and desktops that offer the newest and greatest computational abilities, we can make digital nature just like the real, physi cal thing.

But when we watch hiking vlogs or experience virtual reality, we can only see the river flow and the trees sway. We do not feel the wind or smell the soil. We hear the sky thunder and the bushes rustle. But we don’t have to listen, because we aren’t worried about a storm approaching or a bear lurking around the corner. We know we aren’t at the mercy of the nature we experience because we created it all — it’s under our control.

And that’s the problem. Inherent to nature is the process of living in relation with the other, not in domination over it. Digital nature, as a hu man creation — a product of our utmost control — is not the same. It doesn’t even come close. Its very existence is contradictory to nature itself.

Our attempt to recreate what we have destroyed is not only futile — it’s destructive. Digital na ture is an extension of the exact phenomenon that elicited its necessity.

Smooth mounds of white gypsum blend into the painterly sky. The half-shrouded sun cre ates a soft glow over the deep blue mountains.

zzz

14 spark

15 deathless

My vision goes black for 1/2000th of a second. There is a loading icon, then the photo I’ve taken reveals itself.

It’s just what I had envisioned. Better, even, com pared to the ones I’ve seen. It’ll be the perfect cover for my White Sands post.

I lower my camera, and my eyes are flooded with light. My forehead is hot — maybe burnt. I recoil. I forget I am standing, completely exposed, in the middle of the desert.

And the desert is much bigger than it was through my lens: The mountain range wraps around me, and there is a cottonwood tree to my left.

I blink. The wind picks up again, and silence fades into song, stillness into waltz. The sand hisses in dissent as it is strewn about by the wind, the birds flutter in harmony as they too are car ried along. Even the clouds are swept away, and as the sun spills onto the desert floor, the lizards and mice emerge from their burrows. My senses are heightened as the desert comes alive, my skin tingles as the sun and wind and sand caress my body all at once, and something inside is pulled outwards — something under my skin yearns to break free and fuse into the life around me.

But it can’t. It’s tied down by the strap around my neck.

Suddenly, my camera weighs a thousand pounds. I have the urge to yank it off my body and throw it down the dune, watch it roll and roll until it’s buried in the sand and the elements begin to break it down — the glass back into sand, the metal back into sediment. I wonder how it would feel to be here with no motive but to sit and soak up the way the wind tangles my hair and the sand tickles my skin — no preconcep tion based off of the hundreds of photos and videos I’ve seen, no future Instagram post in the back of my mind. I wonder how it would feel to look at that cottonwood and see something that is just as alive as I am, that has veins and capillar ies just as I do.

But I can only wonder. Because as soon as I saw the cottonwood, I deemed it an eye-sore: It didn’t match the way I expected White Sands to look, nor the way I wanted it to.

So I cropped it out. ■

I WONDER HOW IT WOULD FEEL TO LOOK AT THAT COT

TONWOOD AND SEE SOMETHING THAT IS JUST AS ALIVE

AS I AM, THAT HAS VEINS AND CAPILLARIES JUST AS I DO. 17 deathless

“ “

Vi NATURAE

by PAIGE HOFFER

by PAIGE HOFFER

layout MEGAN GALLEGOS & JULEANNA CULILAP

layout MEGAN GALLEGOS & JULEANNA CULILAP

18

spark

I learned what the world looked like from under the pine and oak trees covering a tiny, red brick house in Alvin, Texas. I’ve known what it means to be saved by them, which means I know, too, what is at stake when they’re lost.

19 deathless

My grandparents lived in my mom’s child hood home, a small bungalow on Oak Manor Drive where cigarette smoke coated the walls in a way that never al lowed it to look or smell quite clean. My grandma’s nightstand overflowed with books, house plants, and other trinkets; copperhead snakes slithered between cracks in the concrete when it got hot, and the per vasive sound of cicadas in the late summer months rang in our ears as we fell asleep. For my brothers and me, this was the setting of many weekends of our childhood.

On Saturday mornings, my grandma would walk with us to the park. We walked down the street un til the asphalt blended into a dirt trail, shaded by pine trees whose enormity made us feel small. We had to crane our necks up to see the tops where light spilled through leaves and cascaded down our faces in scat tered rays. The trees had thick trunks and their worn roots overlapped one another in an embrace so strong it felt as if time began when they crossed. My brothers and I treated the trees with a spiritual reverence: We fell to our knees and collected its pine needles, a piece of God we could hold. We wanted our grandma to feel it, too. She held onto the needles I gave her in her left hand while lacing my hand in her right. We walked down that path where God was not airy, not foreign, but somehow contained in what is seen and touched, still not entirely knowable.

When we returned to the house, my grandad would be laying on the couch, and she would go to shower. My grandparents lived around – and not with – each other. To connect to them, we had to reach their worlds in different ways. Bonding with him meant we had to like grown-up things. We would lay on the linoleum tile floor parallel to where he laid on the couch, watching Elvis marathons and jutting out our bellies to match his, mirroring the cadence of his breath.

They probably shouldn’t have stayed married, but time had weathered them into opposites who shared a house and got used to the way the other snored at night. They were as permanent as the house itself: just like how the roots of the big oak tree in front split con crete into uneven, staggered planes where we played hopscotch, my grandparents’ relationship was, too, beautiful and enduring.

It made sense then, that when he died, everything shifted. It was on my birthday. I didn’t think he was seriously sick, so I spent the last few hours I saw him scrolling on Instagram, on the couch of a hospital room, overcome by the realization that my friends were hanging out on my birthday and didn’t invite me. I had grown into a teenager, centered in the world I created. It was filled with complications they couldn’t understand. They didn’t know about the surveillant, sneaky language of social media in middle school –what it felt like to stalk your friends’ locations and find them together, or to slide up on a story for a “tbh” and be met with your deepest insecurity reflected too eas ily by text on a screen. My world was all-consuming; trees and Elvis were too many generations behind me to matter.

“My world was all-consuming; trees and Elvis were too many generations behind me to matter.”

After the funeral, I saw my grandma when she would swing by the house, on holidays, at birthdays, but never on mine. She sold the house, and laid the roots for a new life with a luxury apartment in my area of Houston, next to a park. I was angry. To sever my ties to their world meant I had to lean more heavily into mine. She became obsessed with working while I moved through high school largely without her. Even though she lived closer, we kept our distance be cause it was easier than trying to find footing in the new, uncertain future of our relationship that might fall and break with one wrong step. Hiding in our busyness took away blame that couldn’t be placed on either of us.

I lost the comfort of routine in my first semester at college. I had planned for my whole life to lead up to that moment–when I was home, I went through the motions of my day with the promise that soon I would be independent and surrounded by thousands of new people in a new place that was mine to explore. When I got there, though, I had never felt so lonely in my life. I walked to class glancing at thousands of faces without having enough time to process them so they all turned to a frenzied blur of people with their eyes cast forward, headphones in. I sat in the back of a

deathless 21

lecture hall for a few hours, returned to my bed, and stayed there until the last possible minute before the next class. I listened to my old playlists, printed out pictures of my friends, and clung to every detail of home, even the things I used to despise.

It’s funny how when I finally got to choose who I could be, I just rearranged the pieces of myself that were already there. One day, I remember having an overwhelming feel ing that I needed to call her. I sat down with my backpack on the lawn, and found a tree to show her. It felt like a pathetic reason to call, but I was desperate to feel home, and to feel it deeply. Today was my brothers’ first day of school and I wasn’t there.

She answered on the fourth ring. She loved the tree. It re minded her of the ones at my brothers’ school, which was near her apartment. She walked there every morning to bless the trees where the kids ate lunch.

“You what?” I said.

She had watched a science special that made her believe the way roots tangled was profoundly human. They could sense when another tree was going through a difficult time, and they would supplement it, sacrificing their own nutrients in order to support the others.

With this knowledge, she would go from tree to tree and put her hand on each one in a sacred exchange. I could imagine her hand on the bark. Her skin had become more translucent these past few years to reveal protruding, green veins that expanded over her hands. They mimicked how time weathers through earth to display the endur ing permanence of the roots underneath. When I was younger, I loved to trace my fingers along those veins.

“Why do you bless them?” I think part of me knew the an swer, but I asked anyway.

“There are ways that I will never be able to protect your brothers. But when they sit underneath the trees, I hope they feel that I’ve been there. The trees get it, you know, the protection.”

There’s a peaceful, resigned stillness in her face, all mus cles relaxed and sinking. When I look at her, I see my kids and their kids too.

I feel something like wholeness — and at the same time deeply afraid because this, this, is what the future will miss.

Let it be known that from the embrace of concrete and tree roots, hands and pine needles, the grave and the ground, I know human and nature need each other. I know this, and still, I know I am not greater than nature; I am of it. Blood flows through my veins with capillary ac tion, those veins stretch out like branches, and the skin that covers them does, eventually, rot. That blood has been passed down to me, and I will pass it to my kids, but I fear they won’t know what it means like I do right now, at this moment that I was so close to losing it.

I don’t think the world will ever be without nature, but I’m scared that we are creating a reality that can exist in dependently of it. When we see nature as something to decorate the world we’ve built and not as the world itself, we will have lost it.

I mourn for my distant lineage who will look at veins of their grandmother’s hands, then their own, and not be able to trace them against the branches of the trees on Oak Manor Drive. Just as we search for traces of ourselves in the people we love, I am afraid we will search for traces of nature in them and find only the subsequent, nostalgic melancholy for pieces of us missing. ■

“I mourn for my distant lineage who will look at veins of their grandmother’s hands, then their own, and not be able to trace them against the branches of the trees on Oak Manor Drive.”

spark 22

deathless 23

24 spark

by RACHEL BAI

In a world where mythology and its relationship with humans form a circle of creativity, comfort, and hope, technology shatters this fragile chain and inserts itself as the only possible answer.

layout JULEANNA CULILAP photographer JACOB TRAN stylists EILEEN WANG & SOPHIA AMSTALDEN hmua MERYL JIANG models TYLER KUBECKA & TIFFANY SUN

layout JULEANNA CULILAP photographer JACOB TRAN stylists EILEEN WANG & SOPHIA AMSTALDEN hmua MERYL JIANG models TYLER KUBECKA & TIFFANY SUN

In the southernmost corner of the sky, the vermillion bird perches on a mountain peak, hooked beak and talons sharp enough to slay gods gripping an imposing trunk. Its fiery red feathers burn a brilliant orange against the sunset. Shrewd eyes observe a mouse dart between grains and alert ears hear a bucket drop into a well. It’s waiting for its next ceremony — the coronation for a young king of a mighty na tion — ready to bestow grace and glory.

Hidden in the dense woods, the king lies in a pile of his own blood. The foul odor permeates the air, but nothing can fog the feral bloodlust of the hunter. She had a hunch that the king’s mea sly bodyguards would be no match for her rifle, loaded with .300 Winchester Magnum rounds. And now she knows that the vermillion bird will soon be a limp, cowardly version of itself.

Finally.

The sun dips into the valley. The stars blink into existence. The vermillion bird expands its massive wings. A boom, a screech, a thud: The scorching south is nothing but flesh and skeleton.

As mighty as any god, when faced with technol ogy, the vermillion bird shrivels.

The hunter lifts her gun in victory.

Somewhere in one of the thousand villages dot ting the coast, glittering sea brightly contrasting the drab and gray landscape, a widow with four children clutches her taser close to her chest. Be sides the tattered blanket wrapped around her children, the taser is the last possession she has for protection. War is long and draining, both emotionally and financially.

SILVER TOP | Sophia Amstalden

SILVER TOP | Sophia Amstalden

“Will we survive?” one of the children asks.

The widow hesitantly nods. She wants to reassure them, but she’s not sure how. There’s a gaping hole in her, one she doesn’t know how to fill. No matter how much she grasps and searches, she still fumbles.

Sometimes, when the night is long and dark and smoke smothers all stars and the moon, she won ders if it’s always been so quiet and dull. She swears that her father’s voice, firm and hoarse, spoke tales of gods and dragons to her, but all the words she remembers are droplets of rain that don’t make sense together. The king dies, and the hunters rise to power: These are the proven facts, as irrefutable as the vermillion that never existed, that became a whisper in the wind.

Outside, a bomb explodes, and the widow drowns in her uncertainty.

In the middle of the Pacific Ocean, while the cap tain marvels at the hunk of metal designed to brave storms and rough terrains, a couple shivers in close pattern with the crashing waves.

The couple hugs each other. Eyes closed, hands clasped, and foreheads touching, they are deter mined to remember the country they have just left. It’s hard, though, especially since every breath they inhale tastes salty. A bit like their tears. A bit like the fear coating their tongues and brains.

The man is thinking about his mother, but in these turbulent, uncertain times, he feels sad that he can only remember the spinning machine. It spun and whirled a hundred times faster, produced more effi ciently than ever, but he can’t recall exactly what his mom was weaving. In his memory, the thousands of pieces of fabric were nothing but a blob of color, devoid of individualism and culture. Click clack, plop and hiss: He wonders if there was a time when his mother listened to other sounds besides metal against metal.

Then, he wonders what he will bring to this new land.

“What will we give our children?” he asks his wife.

She lifts eyelashes to reveal dark, wet eyes. “I don’t know.”

deathless 27

28 spark

“As mighty as any god, when faced with technology, the vermillion bird shrivels.”

29

SILVER SCARF | Sophia Amstalden SILVER NAILS | Eileen Wang

deathless

30 spark

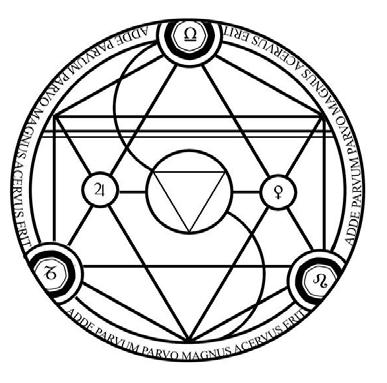

To start from the beginning of the world means to start with mythology. Soaring above human limits, beyond even technology, and fueled by hope and wonder, it is born out of uncertainty. The explo sions of desire, the mystery of the unknown. My thology at its core contradicts technology. Where one exists, the other cannot thrive.

When exhausted civilians retire from a day of till ing and harvesting, they look upon the pool of stars dripping down the night sky for comfort. They see two lonely souls desperate to reunite and the heav enly mother kind enough to weave the stars into a bridge. The sweat dripping onto the dusty grounds hints at the possibility of fruitless labor, but the warmly illuminated stars remind them of hope and solidity.

When tables are empty and white is all that can be seen, a weary mother hugs her sickly babies and remembers Tudigong, the Earth god. She’s already cried for the past two days, and the only reassurance left is that her baby will be taken care of in the af terlife. Gentle in appearance and nature, Tudigong embraces her agony and softens her raw edges.

This is the truth that people believe in when the tunnel is dark and the light is far. This is the truth that has achieved immortality. The branches of this ancient tree change and mold as societies and indi viduals evolve and adapt; however, the fundamental roots anchoring the trunk deep in the dirt remain the same emotionally and spiritually. Humankind’s belief in everything and nothing might disappear, but the remnants of stories that remain inside of them will last forever.

Societies are built from these remnants. A primitive giant cracks the chaotic world in half with his ax, and from his sheer strength comes the separation between yin and yang, land and sky, balance and creation. His statues stand tall and proud, full of purpose, duty, and responsibility. The Three Sover eigns, demigods at their core, use magic to improve lives and, at the same time, remind people of kind ness and empathy. Lessons of courage and passion, virtue and loyalty: These leading principles become the foundations of human interaction and societal construction.

31

From these commonly accepted morals and ethics comes the establishment of law and order. The complex web that exists between mythology, culture, and value has become so inter twined and tangled that one cannot separate from the other without loosening the yarns making the string. Every interaction leads to another idea, which ultimately crosses the boundaries and dabs a hesitant foot into the creation of major belief systems that could go on to change the world. Destroy the massive pillars anchoring the roof to the floor, and the beautiful structures would subsequently collapse, too.

And when that happens, what will be left at the end of the world is rusting metal and toxic sludge. Technology gives people a sense of faux permanence. It comes in with its flashy gad gets and sweeps aside the shiny diamonds that have existed in minds for thousands of years. However, it will eventually erode and disappear, and the certainty it provided will burn to ashes. Left with no armor or shield, humans will end up struggling to grapple with the new reality, one where mythology hasn’t been provided a chance to grow and bloom into the pro tection it could be.

In one world, a lovely goddess and her pure white rabbit reside in a heavyset house gleaming a dark maple red under the brilliant light of the sun.

In another world, the telescope forces people to look up and see the uglier truth: craters, eroded rocks, and one dusty footprint. ■

“The complex web that exists between mythology, culture, and value has become so intertwined and tangled that one cannot separate from the other without loosening the yarns making the string.”

32 spark

33 deathless

terra nullius

34 spark

layout JAYCEE JAMISON photographer REN BREACH stylists MIRANDA YE & EMILY WAGER hmua CLAIRE PHILPOT & ALEXANDRA EVANS models ENRIQUE MANCHA, BRANDON AKINSEYE, & NIKKI SHAH

35 deathless

36 spark

37 deathless

38 spark

39 deathless

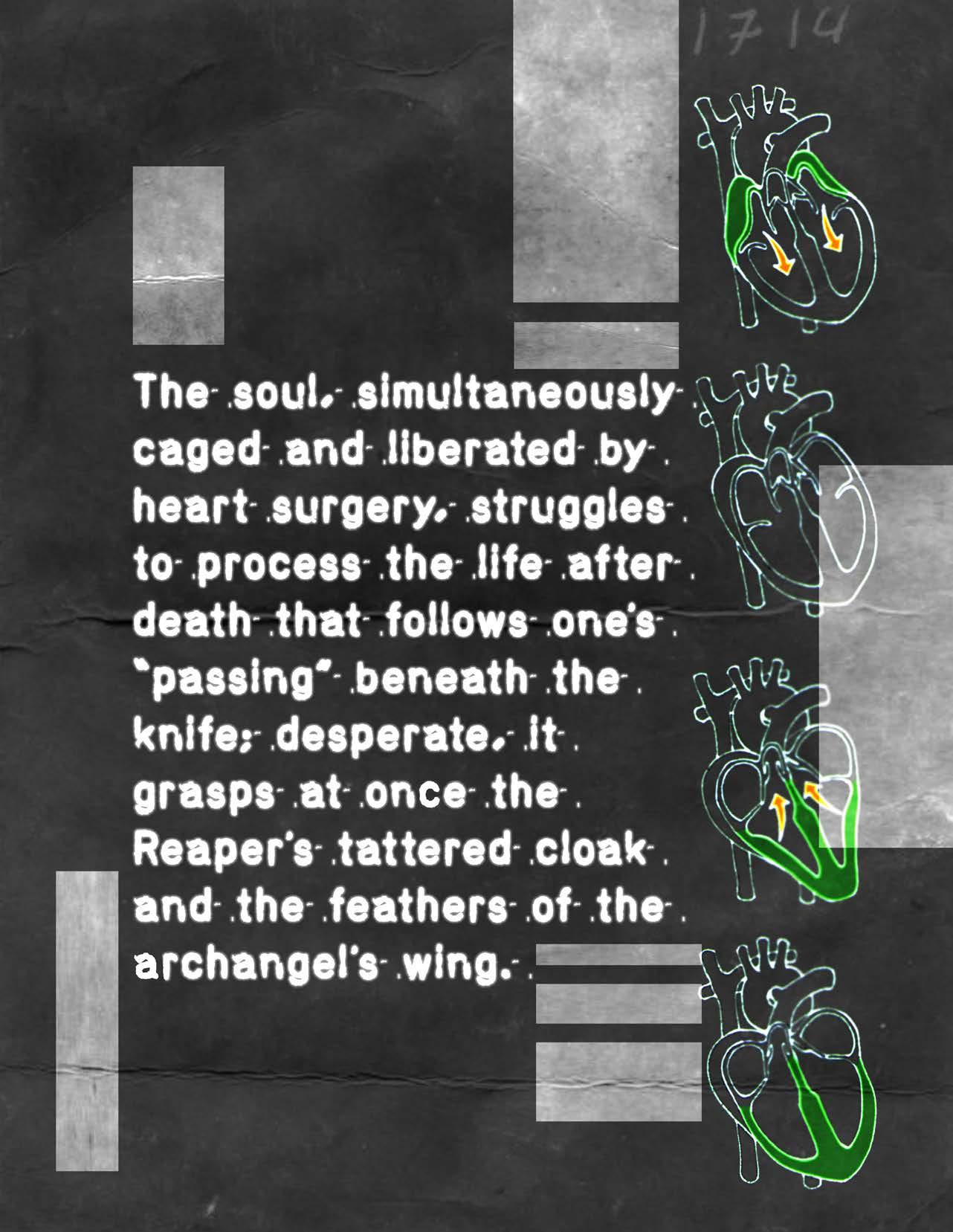

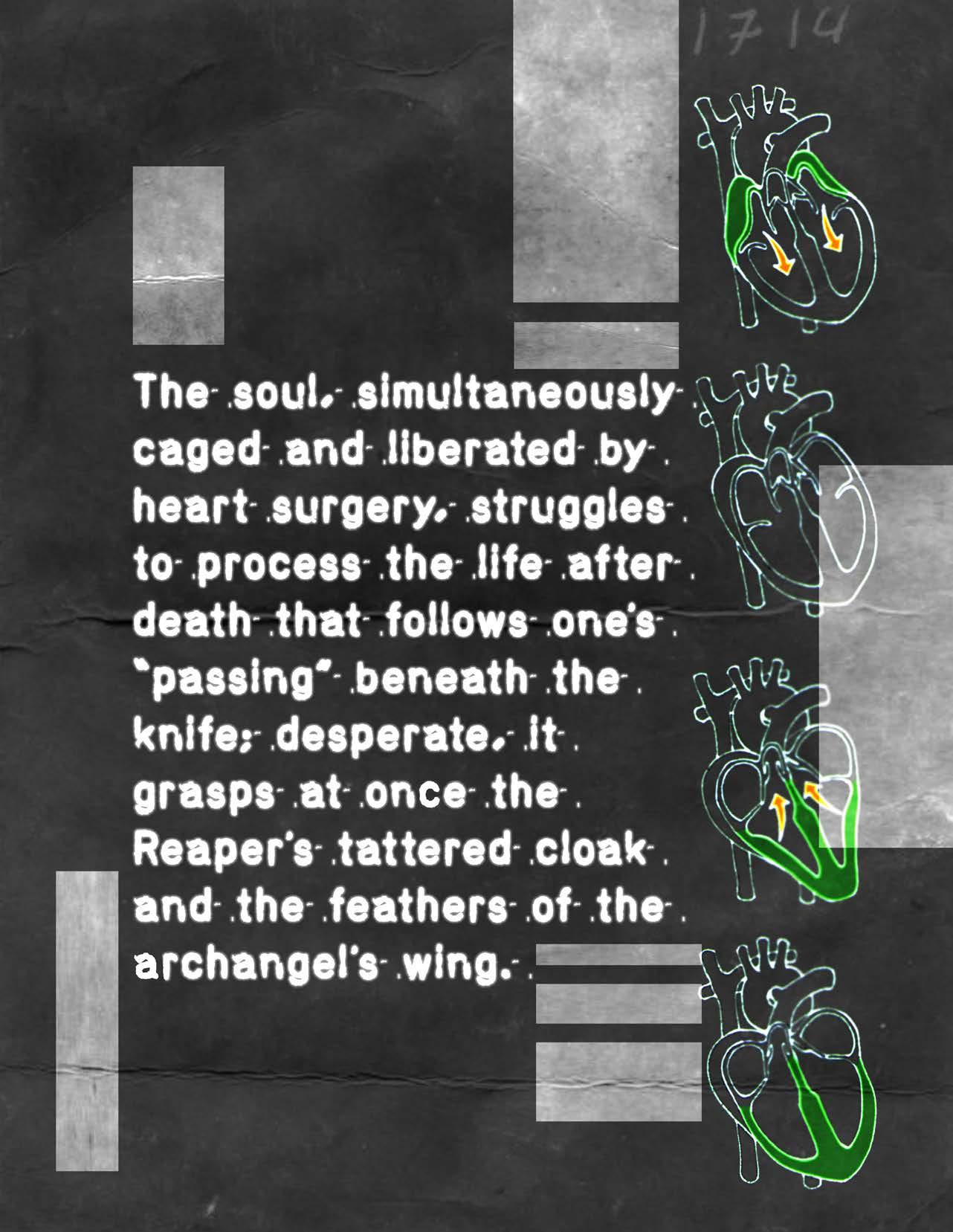

When posthumanism erases our need for faith, I am unsure whether or not we will mourn our loss of divinity.

by ALLISON NGUYEN layout SOPHIE ZHANG

by ALLISON NGUYEN layout SOPHIE ZHANG

40 spark

he last time I prayed was July 22, 2022.

I clasped my hands with my mother and did the sign of the cross in a sprawl ing restaurant in Barcelona, surrounded by tapas and sangria, while my father broke down crying in front of a startled Spanish waiter.

My grandmother had just been taken off life support in the States.

We spoke to God at Barcelona Airport.

I asked him to get us tickets for a safe flight home to see my grandmother go up in flames and spread through the temple. But when we booked the tick ets and made the flight, I thanked ev eryone else: the flight attendants, the airport staff, and the stellar Wi-Fi in the terminal.

Everyone except God.

He (The Almighty) didn’t even receive a thank-you card in the mail.

Postage was too high and so was my pride. Despite praying for God’s divine hand to change the tides of fate, bestowing upon us a flight home, I se cretly begged for the computers to spit out the right sequences of code instead.

In the end, my flight home material ized from our divine creation: the 2017

TDell Desktop that sat in the Southwest Airline terminal, repeating incessant zeroes and ones that slowly printed out BCN → IAH.

The day I felt most hopeless I joined my mother in begging for God and his divine hand. But when the golden beam of light shone down on that 2017 Dell Desktop, I no longer cared for religion or God. Rather, my faith turned to humankind’s creations to solve my problem.

This wasn’t always the case. When I was younger, my pedestal for God was the holy water on my night stand.

Every time a demon or clown would appear in my nightmares, a sprinkle of holy water and the sign of the cross would solve all of my problems, the almighty Jesus Christ christening me from the heavens above as the mon sters slowly drifted from my mind. The quick fix of God became my lord and savior: Every time a small issue or problem would arise in my life, I would splash holy water across my face and sign the cross. God became the creator who could solve all, the deity that could dissolve my problems.

41 deathless

But when my mom got cancer, God’s quick fix was no longer an option. My new fix became the sharp slice of the scalpel and the Bible of che motherapy, putting the creations of humankind on a pedestal instead.

I stopped praising the holy water on my nightstand and turned to IV pumps and vac cinations.

God is relied upon because of his omnipo tence — his ability to solve the problems mere humankind cannot. Yet in the modern world, humans have inched closer and closer to the miracles of divine power once figured impos sible by the creators of the Bible. Is the cre ation of cures to diseases like polio not akin to Jesus curing a man with leprosy? When hu mans provide better solutions than God him self, God feels as if he may almost dissipate from our reality, becoming irrelevant the day we gain the ability to solve all the problems humankind once could not.

From the dawn of our creation, humans have been defined by our struggles. By war, disease, and disasters. We are defined by our tragedies — take a look in a history book to verify it. But God? He is defined by his lack of tragedy. His lack of struggle. His all-consuming power.

It is this power differential that necessitates faith in religion.

Already, analysts and researchers are tracking the decline of religion in the modern world. From 2007 to 2020, 49 countries representing 60% of the world’s population had a decline in re ligion, this decline most apparent in high-in come countries. In these high-income coun tries, as technological innovation persists and presents as the cure to all ailments, belief in religion declines in response. When granted unlimited access to modern solutions, people lose the need for religion, now faithful to technology to fix their problems instead.

The largest form of this shift away from reli gion took place in the United States. For de cades, Americans have been a prime example of the idea that modernization and religios ity can coexist. Despite this pious image, the American public has been moving away from religion even more rapidly than other coun tries in recent years.

Although there are several forces driving this trend, the downfall of religion in America — where innovation runs rampant — signifies something greater about the struggle be tween innovation and religion: They cannot, in fact, coexist in modern society.

42 spark

“I stopped praising the holy water on my nightstand and turned to IV pumps and vaccinations.”

When I discovered the divine nature of chemotherapy and IV tubes, religion dissipated in my life. Technology began to pre vail.

As I’ve lost my faith in religion, I’ve become grounded in the roots of reality — to my detriment. Technology is wonderful in so many ways, allowing us to constantly improve our lives, transforming and redesigning at every step. Yet the loss of reli gion has placed an indescribable burden on me.

Now, when I wake up from a nightmare, I have no peaceful sol ace that comes from a simple gesture, no sense of calm that comes from the splash of divine water across my face. Instead, I must have faith in myself to remove the jarring images from

my mind, doing breathing practices as I lie in bed, at tempting not to wake my roommate.

Perhaps in my haste to engross myself in human kind’s creations, to solve all of my ailments and strug gles, I’ve lost something else. Maybe hope, or naivety. I’m not quite sure. What I am sure of, though, is that since I’ve removed the cross from my room and the holy water off of my nightstand, there’s an emptiness that sits in me when I struggle — a sort of suffocating burden that God can no longer take off my shoulders.

When posthumanism erases our need for faith, I am unsure whether or not we will mourn our loss of di vinity. In order for humanity to achieve its apex form, I must stab my Creator in the back. Am I not stabbing myself in the back as well though? By eliminating the need for prayer, I lose the solace and peace I gain from it too.

The face of God will change from scripture to anima tronics, the Bible turning into an instruction manual. The Machine will become my new faith, tying down with it my ability to find peace in what I turn to. The Creator’s bible can be morphed, turned into a cod dling blanket for all of my worries. But the Machine’s instruction manual has no ambiguity, full of ones and zeros that spit out one definitive answer.

While an instruction manual is clearer, can humanity be extracted out of it?

Only time will tell. ■

43 deathless

“In order for humanity to achieve its apex form, I must stab my Creator in the back.”

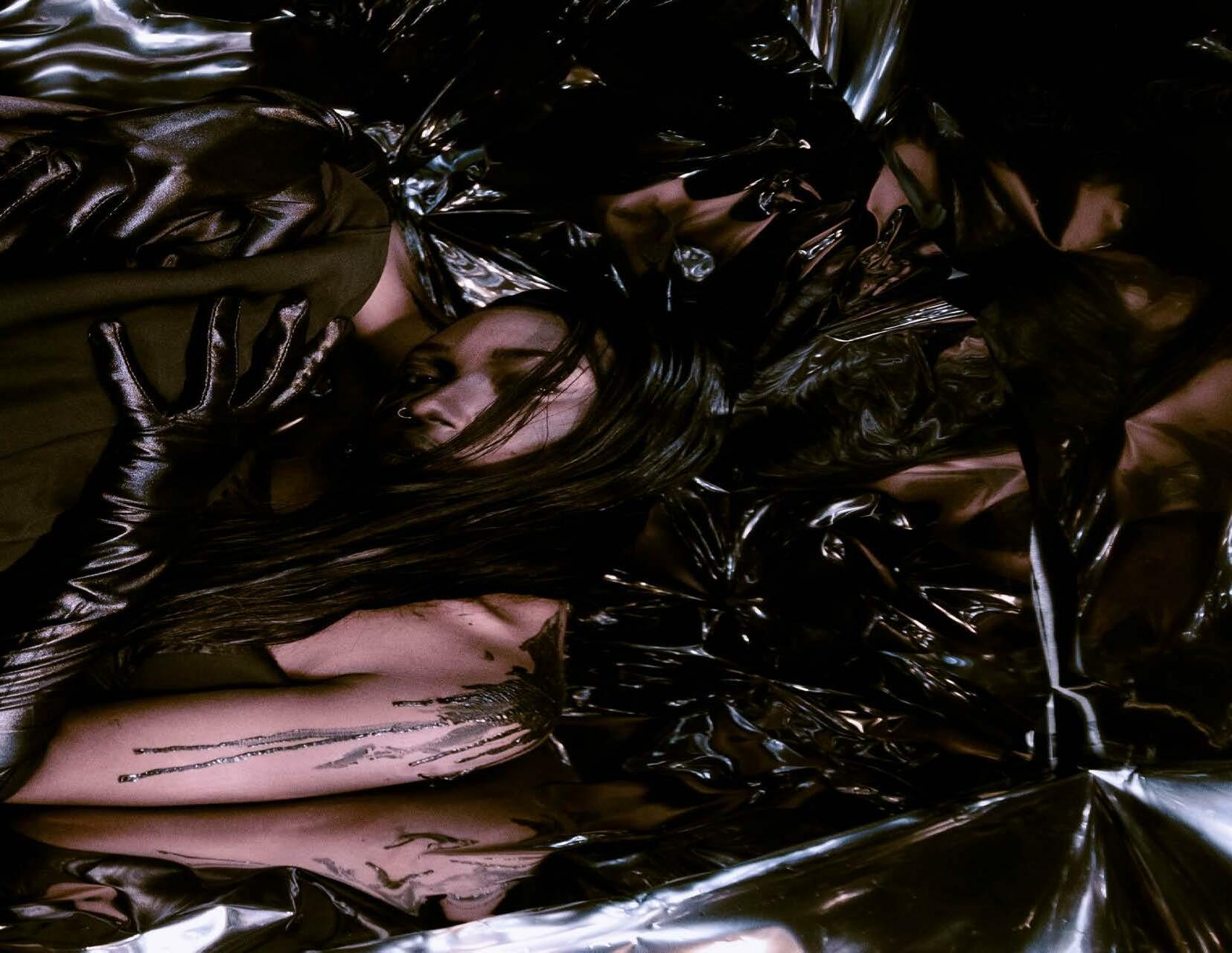

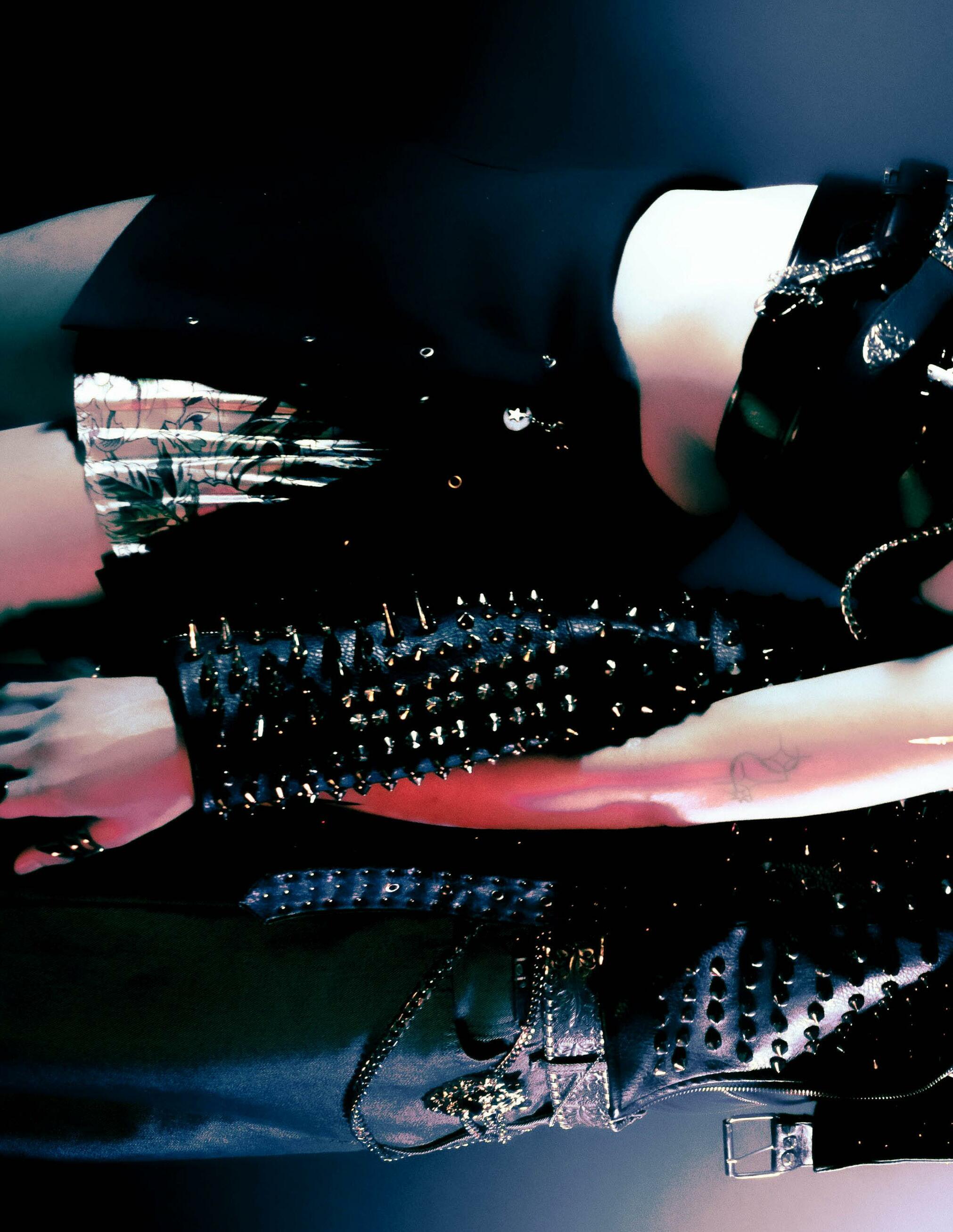

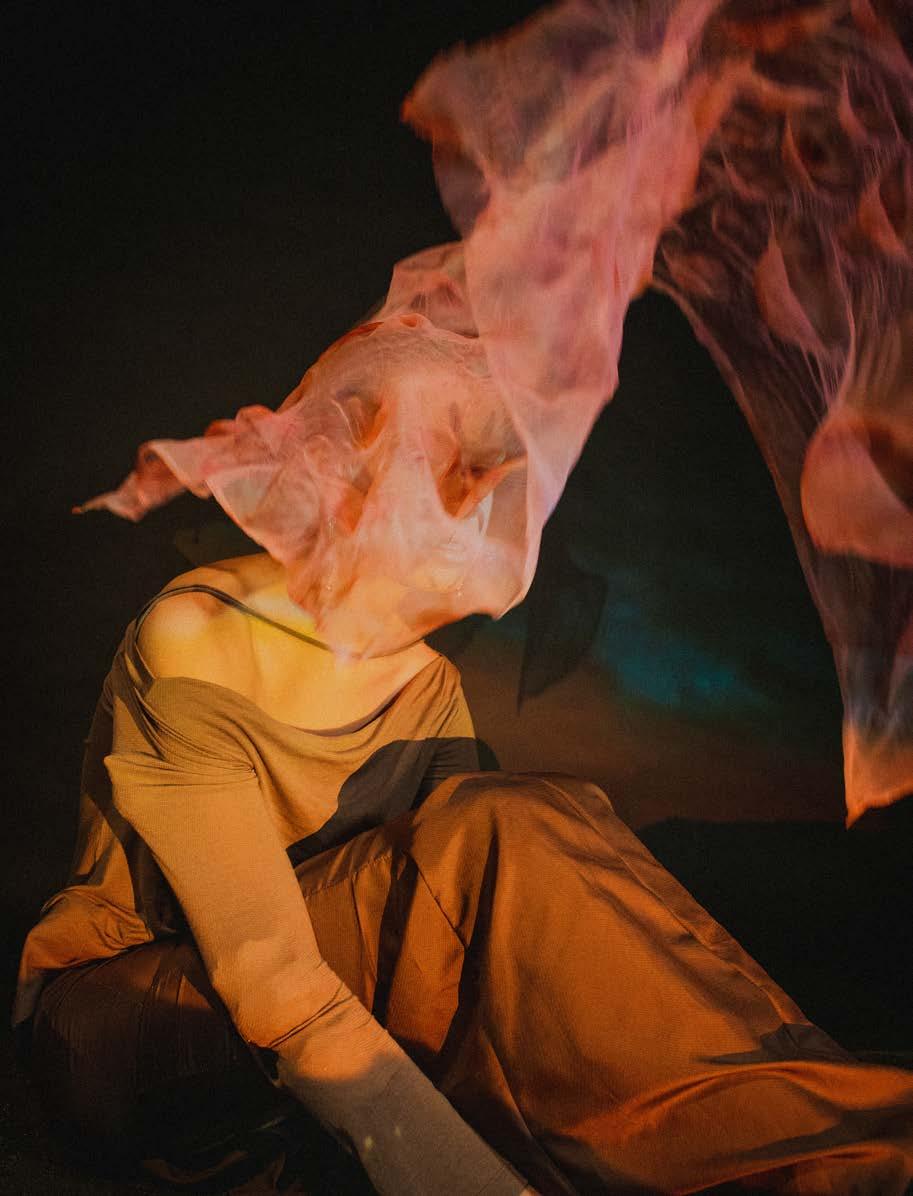

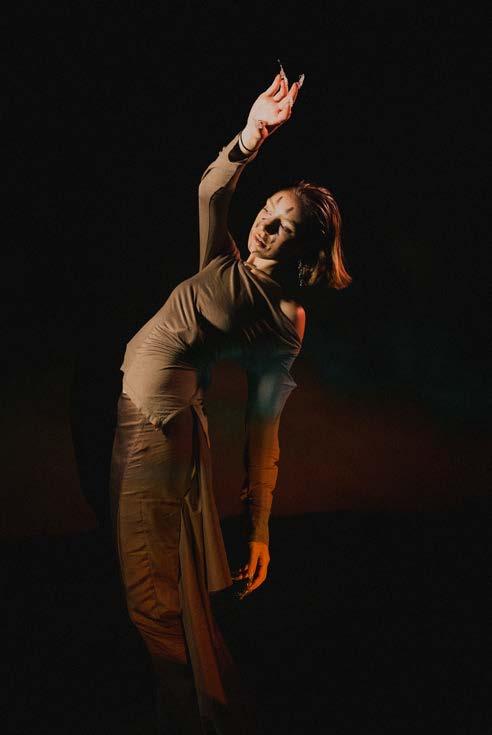

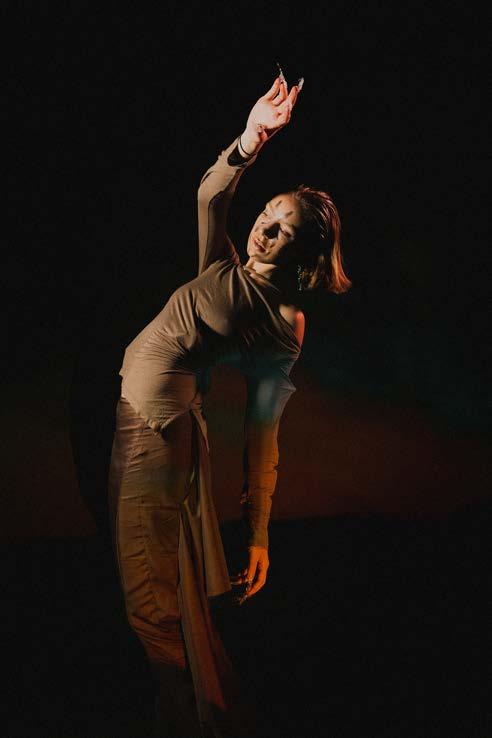

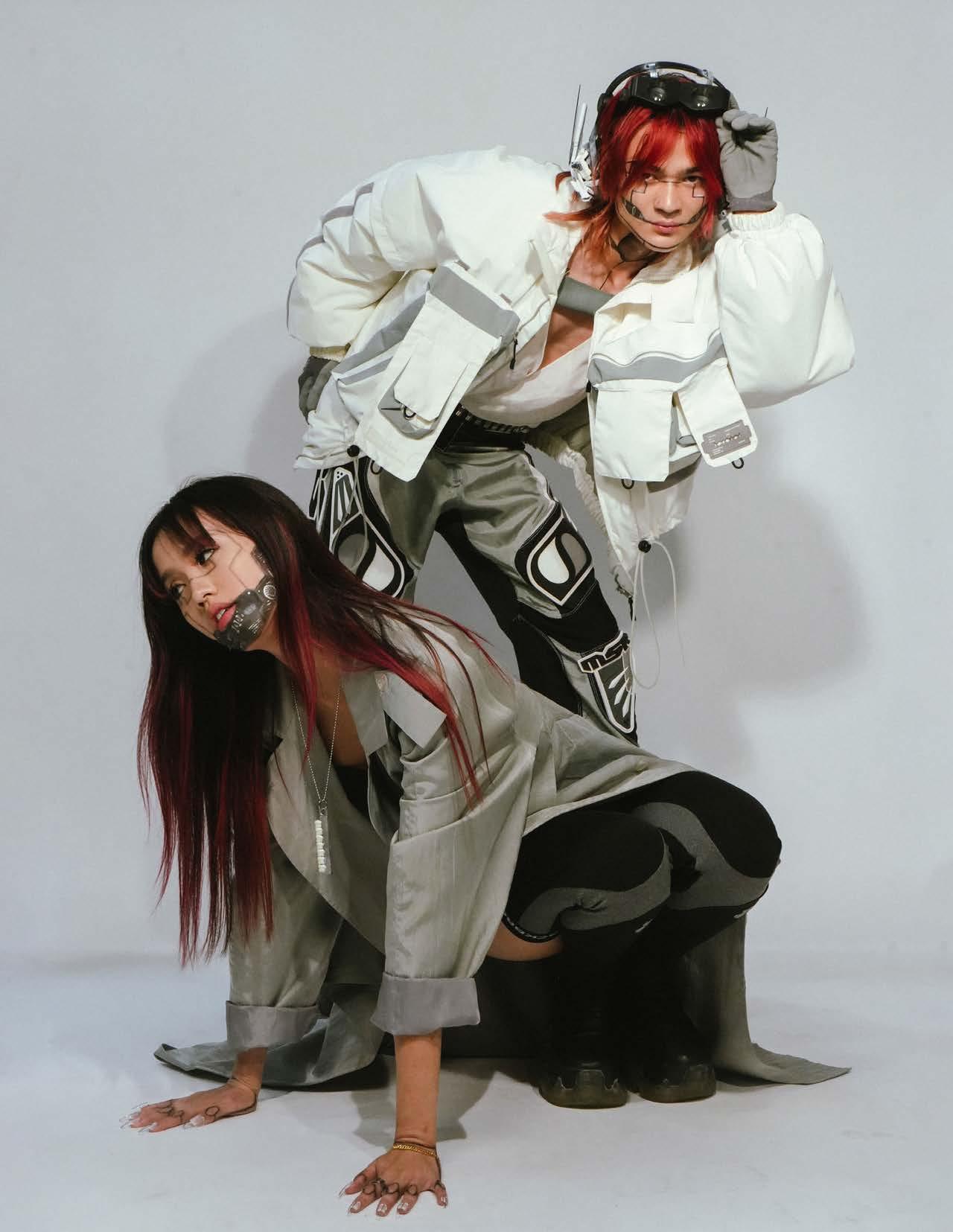

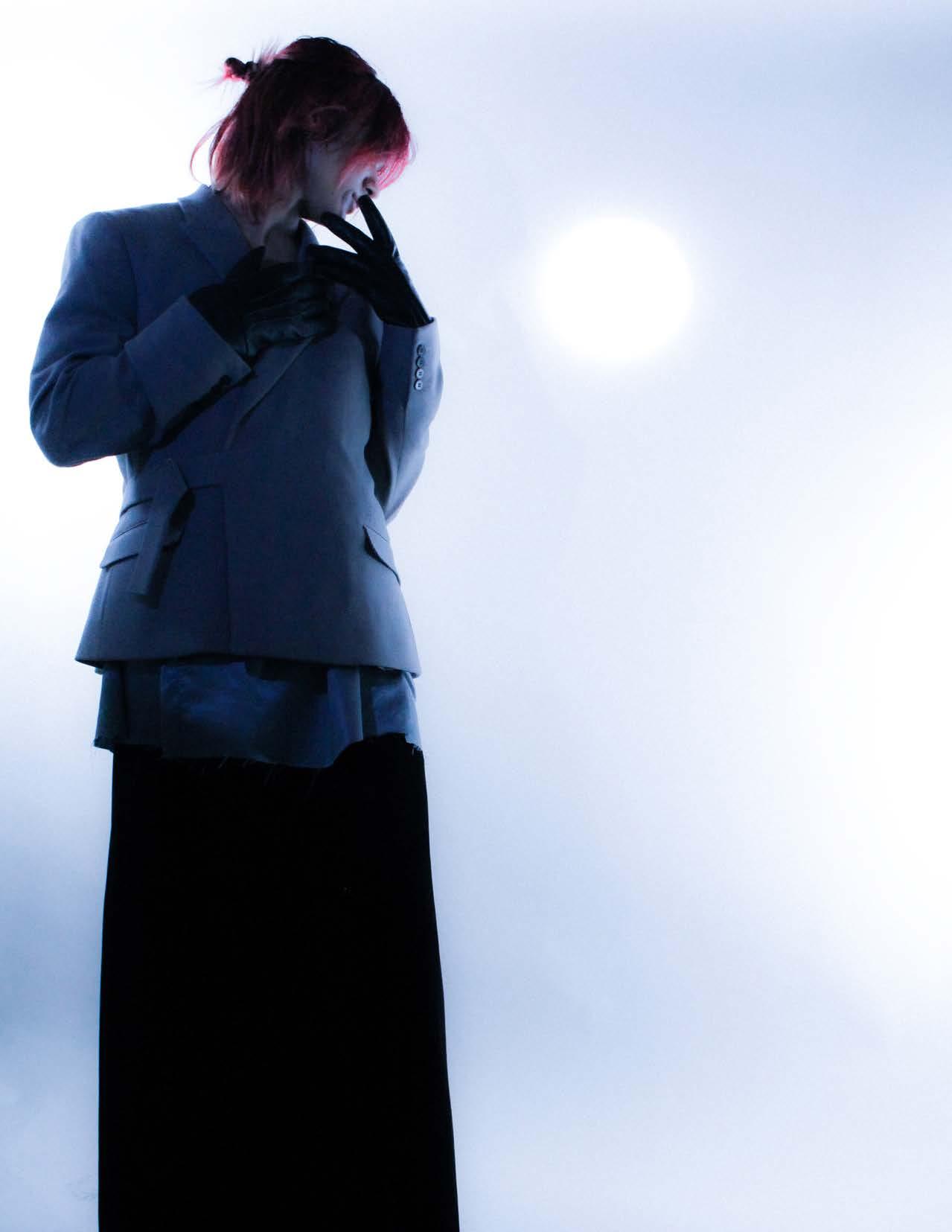

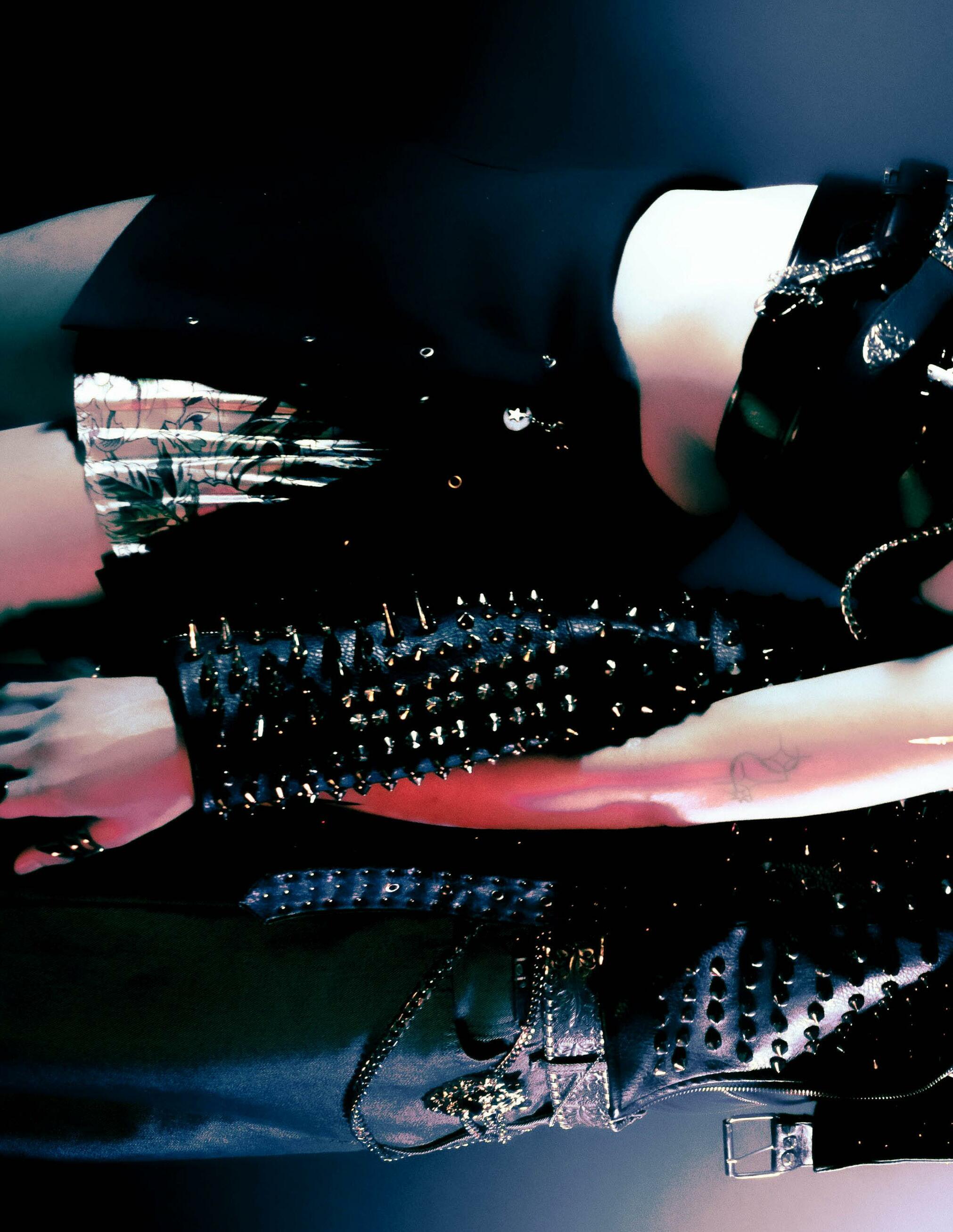

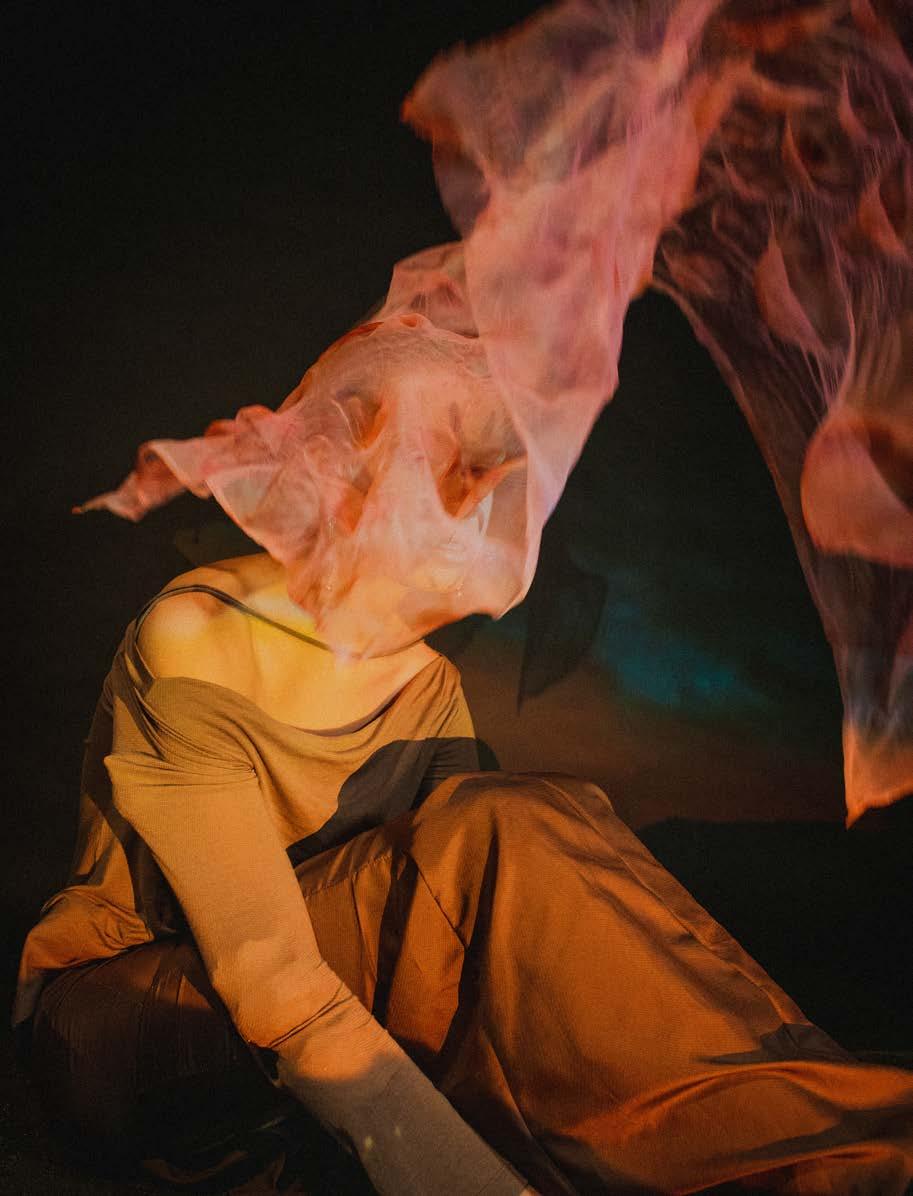

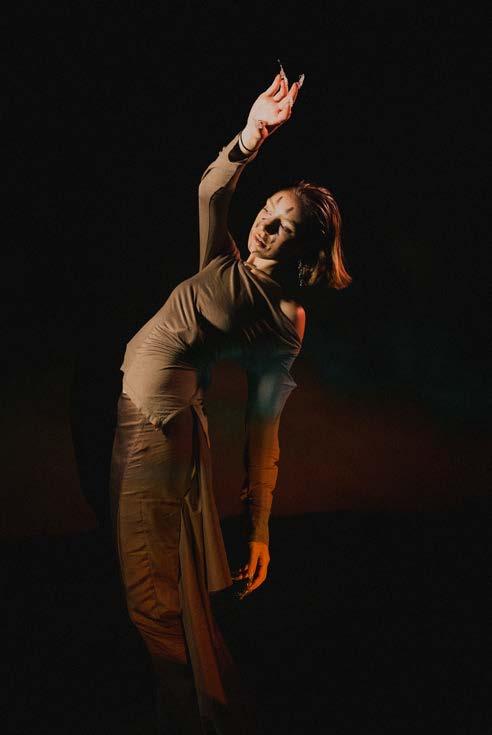

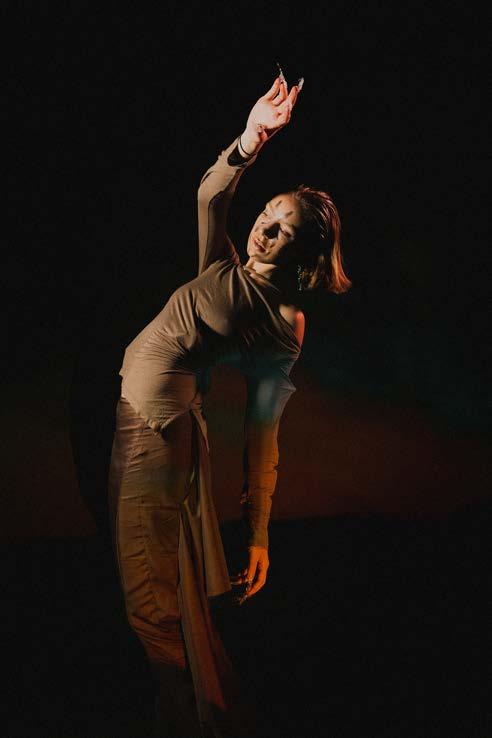

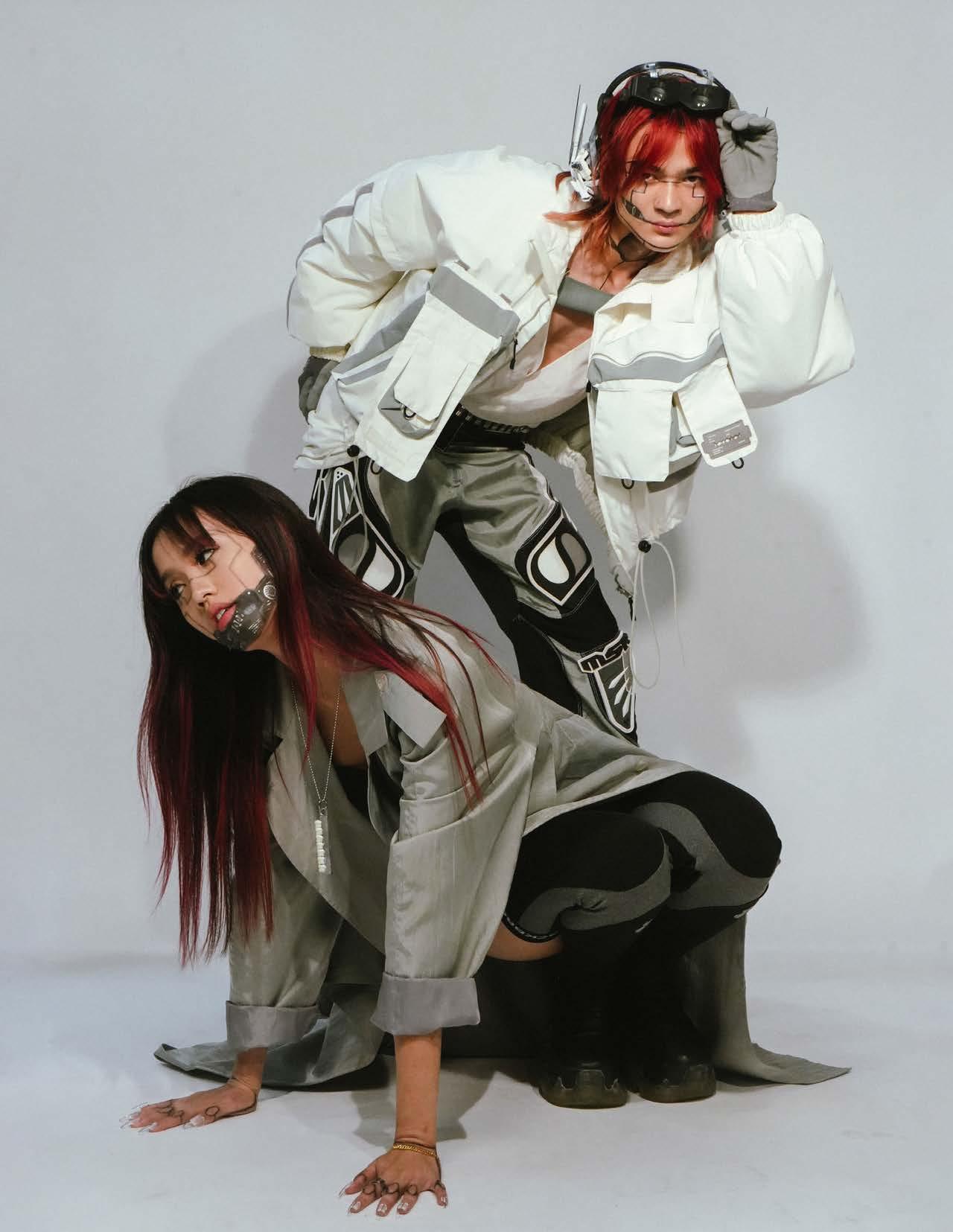

layout VYVY LE photographer RACHEL KARLS stylist YOUSUF KHAN hmua LEAH TEAGUE & CLAIRE PHILPOT models JILLIAN LE & LAURENCE NGUYEN-THAI videographer MOISES ZANABRIA

layout VYVY LE photographer RACHEL KARLS stylist YOUSUF KHAN hmua LEAH TEAGUE & CLAIRE PHILPOT models JILLIAN LE & LAURENCE NGUYEN-THAI videographer MOISES ZANABRIA

45 deathless

3 BELTS | Revival Vintage 2 BELTS | Flamingos Vintage Austin 1 BELT | Big

Paradise 46 spark

Bertha’s

47

LEATHER SPIKE STUDDED JACKET | Big Bertha’s Paradise

deathless

48 spark

49 deathless

by SAFA MICHIGAN layout EMELY ROMO

This week, a hot new bombshell enters the villa. We don’t know if she’s here for money, for fame, just for fun, or to quell an aching desire for human connection, but sit back, relax, and watch how everyone is going to pick her apart. Will you relish it?

Each June, five single men and five single women specially selected for a summer of love descend upon an island villa, ready to spend the next eight weeks lounging in their swimsuits with only each other’s company.

They are not permitted outside contact until it’s time to meet the families. No books, no magazines, no media at all. Conversation topics are limited. Communication is monitored. All day is spent wait ing for instructions from the gamemakers. They are told when it’s time to participate in erotic (as hot and heavy as cable television allows) challenges, when it’s time to go on dates, when it’s time to recouple, when it’s time for a new bombshell to enter the villa and shake up established dynamics, and when it’s time for the infamous Casa Amor. During this climactic point each season, the remaining women and men are separated into different villas, and a fresh set of men and women (respectively) are sent in to generate chaos and test existing couples’ loy alty. The show is like a live-action dating app, from the coupling ritual that takes place at the beginning of every season, to the constant introduction of new faces, to the recoupling ceremonies.

In heavily edited footage excised from over a thou sand hours of observation, the contestants perform for the cameras and for audiences at home who will decide their fate. They prove that they’re in love, or they prove that they’re interesting enough and, therefore, worthy to continue on the journey.

This is the general premise of any season of the Brit ish reality television series Love Island, now with American and Australian spinoffs. The original it eration of the show featured celebrity contestants. The series was unsuccessful, however, until a re brand that nixed the celebrities and opened appli cations to the everyday man or woman — as long as their gender identity is palatable to the dominant

culture and their physical attractiveness is rooted in European beauty standards maintained by the racial homogeneity of the mostly white cast. Contestants of color are often invisibilized or tokenized in the court ing process, but it’s especially gratifying when they find what seems like a genuine connection. It’s espe cially disappointing when they’re voted off.

Inextricable from the appeal of the show is its tropical setting and the flashy colors characterizing the villa’s decor. It’s an escape from the humdrum of late stage capitalism or the boredom of a loveless life, a respite from the unfulfilling game that is modern dating. On one level, the contestants are competing for money, wherein partly lies the commodification of love that fuels the show’s appeal to the public, but the produc ers are also getting rich off of love as a construction. Under technocapitalism, love is entertainment, and it’s a pipeline to wild success as an influencer.

Seventy-three surveillance cameras adorn the villa, even in the large shared bathroom. We accept this invasion of privacy because the contestants techni cally consent. Consent is complicated by the fact that they have no influence over what is eventually broad casted to the public.

On Love Island, reality and fantasy blur into a frothy concoction of exhibitionist delight, and I, the voyeur, tune in for the chance to drink it in, along with mil lions of others.

We become emotional voyeurs because we are des perate for connection. Our voyeurism derives from a place of empathy and fundamentally, a fascination with the human condition itself. The Love Island villa operates as a laboratory experimenting on the spec trum of human emotion. Research questions: How does temporality shift when you remove daily dis tractions like media consumption from the equation? What happens if you drive a person just a little mad?

51 deathless

52 spark

“On Love Island, reality and fantasy blur into a frothy concoction of exhibitionist delight, and I, the voyeur, tune in for the chance to drink it in, along with millions of others.”

The villa is a microcosm of the larger state of human interaction in the age of technocapitalism — in other words, it reflects how the rest of us love each other, surveil each other, pick each other apart, and even kill each other. The show’s former host and two former contestants have committed suicide, re vealing the tangible consequences of love under surveillance.

The consumption of reality television is an exercise in determining what is genuine and what is an illusion; we find delight in discerning between organic conversation and semi-scripted dialogue, between love and lust, be tween primal emotional outbursts and theatrical performance. The act of viewing is also a process of creation: We create authenticity out of unclear, murky moments in a parasocial projection. We pretend we know the contes tants and that we know what’s best for them.

In one retelling, 18th-century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham har bored good intentions when he invented the panopticon. His system of so cial control was initially designed to uphold prison as an idealized site of reformation.

Within a panoptic structure, a single authority figure presides over incarcer ated individuals from a watchtower in the center. Those incarcerated are unable to discern when exactly they are being watched, so even though they know it’s physically impossible for the warden to observe them all simulta neously, a sense of paranoia seeps in, forcing them into what Michel Fou cault calls self-regulation.

The Love Island villa is a glossy, colorful panopticon out of Jeremy Bentham’s wildest dreams. On Love Island, producers and editors are the few wardens observing the many through a sophisticated system that ensures control. As I watched Love Island USA season four last month, I noticed one particularly jarring neon sign among the kitschy collection decorating the villa: “ALL EYES ON ME.”

At the inverse of panoptic surveillance lies synoptic surveillance, through which the many watch the few, made possible by the rise of mass media, cable and streaming television, and the Internet.

Millions of people debate contestants’ every conversation and every facial expression from the comfort of their own living rooms thousands of miles away, yet are deeply invested in their actions. They tweet and post on Red dit. Producers even show contestants select social media posts. After the show ends, former contestants build livelihoods out of their success, nego tiating brand deals, becoming influencers, and capitalizing on the synoptic surveillance they experienced.

The interactive structure of the show allows us viewers to play gamemaker, and we even get to play God. As citizens of a surveillance state, we have long tried to harness His eyes. Through our role in this synoptic system of con trol, we are able to reclaim omnipotent power, even if for only the moment it takes to vote someone off the island.

53 deathless

In one sense, the few watch the many in the villa; in another, the many watch the few. The structure of Love Island allows panoptic and synoptic surveillance to work as syner gistic systems of control, but they are com plicated by an interesting phenomenon: the watched watching each other. In other words, those coerced into self-regulation also regulate the behavior of those around them, replicating the surveillance practices they endure together unto one another.

What’s unnerving — and delicious — about Love Island is that the contestants volun teered to subject themselves to these multi plicitous layers of surveillance, anxiety, and paranoia. It’s a social experiment in which I often find myself wishing to participate, fantasizing about the decisions I would

make, the strategies I would use, and the way I would present myself.

I, like the contestants, am also constantly watched and witnessed by both conspicu ous and unseen forces that influence, con trol, and police my behavior.

As a citizen of a surveillance state, I live under the watchful eyes of CCTV, secu rity cameras on every block, and biomet ric identification. There are 4.6 people per camera in the US, and once you’re cata loged in the system, it’s virtually impossible to erase yourself from it.

As a habitual social media user, I’m a consis tent practitioner of exhibitionism, a curator of experiences and memories. I was a child

raised by the Internet, an active agent in my own surveillance. For years, I broadcasted intimate details of my life to a “finsta” I let relatively un trustworthy people follow. When I experienced hypomania (before I even knew what it was), I found myself oversharing on Snapchat and Twitter. Lonely, I sought the mirage of close ness I thought public vulnerability could bring me. Online, I am also a voyeur, entertained and placated by illusory access to the lives of those I know well and those I don’t know at all.

As a woman, I endure the incessant attention of the male gaze, and I am repeatedly constructed under its exploitative eye. The women on Love Island experience this at its most exaggerated.

And on my worst days, when I desperately need the world to make sense, I am hyperconscious of the eyes of God. On those days, I feel guilty

about my decisions, as though the wrong ones I’ve made could sentence me to the eternal dam nation they’ve been warning me about since I was a child.

But the guilt often resolves itself, and through my characteristic refusal to self-regulate my be havior in spite of the threat of hell, I defy God. That doesn’t mean I’m unscrupulous. Morality doesn’t necessarily emanate from religion; really, it comes from within.

There are eyes on me all the time, real and imag ined. I can only hope they’re enjoying the show. ■

54 spark

55 deathless

“Thereare eyes on me all the time, real andimagined . Ican only hope they ’ re enjoying the show. ”

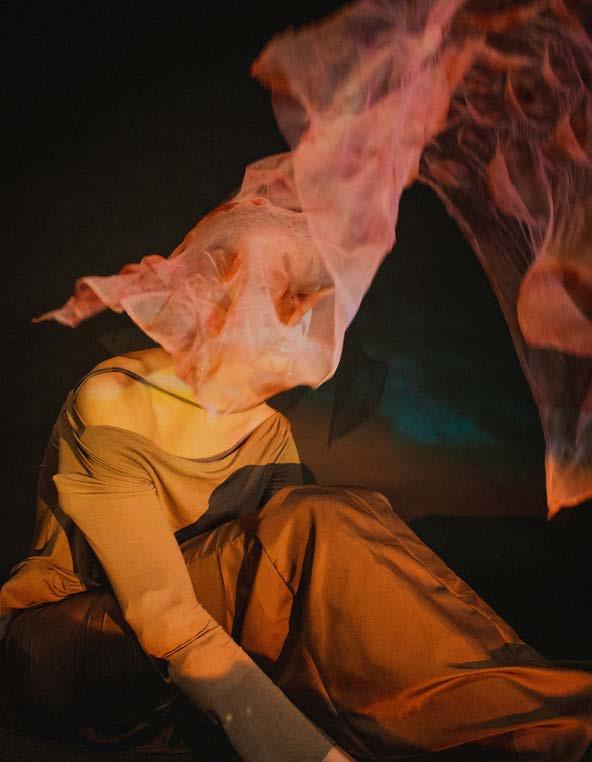

by CLAIRE TSUI

layout CAROLINE CLARK photographer ANNAHITA ESCHER stylist DAVID GARCIA hmua GABRIELLE DUHON model PRESLEY SIMMONS

by CLAIRE TSUI

layout CAROLINE CLARK photographer ANNAHITA ESCHER stylist DAVID GARCIA hmua GABRIELLE DUHON model PRESLEY SIMMONS

56 spark

“A sense of wrongness, of fraught unease, as if long nails scraped the surface of the moon, raising the hackles of the soul.” — China Mieville

WHITE TOGA | David Garcia

METAL PLATE | David Garcia

WHITE TOGA | David Garcia

METAL PLATE | David Garcia

first sight sees, in a single glimpse,

Pygmalion and the sun crowned

“Her

spark 58

behind his head.”

I: Galatea

Swathed in silks and linens stands an ivory maiden. She is struck in a pose of effortless grace, her lips pressed shut and her gaze lowered in gentle demurity.

Before her stands her sculptor, king Pygmalion. Notorious for his disdain of the lusty women in his realm, Pygmalion sought to create one of his own. One hewn to his tastes, whose eyes could see no other, and could thus belong to no other. With a half-curled hand, he traces his fingers along the cut of her cheek, his eyes roaming over her exquisitely carved face in raptured silence. He marvels at the pearlescent beauty of his work, as pale and otherworldly as the moon.

Perfection, he thinks. She is perfection incarnate.

Yet like the moon, the maiden remains stonily out of Pygmalion’s reach. Her fingers are cold and stiff, her ivory flesh unyielding to his touch; lovely as she may be, he cannot truly be with her.

Driven to obsession by his inability to have her, Pygmalion finally beseeches none other than the goddess of love herself.

To turn men into stone is the power of Me dusa, but to turn stone into woman is Aph rodite’s. From high above in her heavenly chaise, she observes, with detached amusement, the small mortal man currently knelt before her pyre. Resting her chin upon a delicate hand, she leans over the clouds to hear his pleas and to determine whether his heartache is worthy of her time. As she listens, her lips twist wryly.

So this is how mortals love, she hums to herself. He has fashioned himself a dumb, mute, beautiful statue, and now he wishes for it to become his dumb, mute, and beautiful queen.

But she sighs obligingly and casts her voice to the earth, where it spirals down from the vaulted ceil ings of the temple into Pygamlion’s ears. Amidst the smoke and savor, she tells him to return home and embrace the statue, that he will see it become

a maiden in his hands.

Pygmalion rushes back to the pavilion in excited haste. Throwing himself upon the statue, he gathers it into his arms and seals its ivory lips with a kiss. When he draws back, he sees lips flushed red with life-blood and a maiden of flesh and bone. Her skin is still pale like the moonlight, and he watches, entranced, as she raises her dark eyes with the shyness of a newborn fawn. Her first sight sees, in a single glimpse, Pygmalion and the sun crowned behind his head.

Beheld by her wide, innocent eyes — filled with nothing but him and the heavens above — Pyg malion knew he could love no other.

II. Ex Machina

Myth is enlightenment, and our enlightenment returns to myth.

The desire to artificially cre ate another being, one that is bent to our will, is rooted in narcissism, a hubris tic hunger to play god and build in our own image. In this era of biotechnology and artificial intelligence, it is more pos sible than ever for men to become postmod ern Pyg malions. Now, instead of smooth ex panses of ivory, their lovers possess lithe, flexible torsos supported by metal frames, chrome limbs wrapped in synthetic collagen — sleek and shiny, like a boy’s novel plaything.

Those who claim the superiority of the gynoid over the human woman cite its ability to be our perfect lover. Programmed to our unique tastes, the gynoid self-adjusts like a personal thermostat to meet our needs. By analyzing our behavior, it adapts accordingly to our hot or cold to never frus trate, disappoint, or betray us. The gynoid would be devoted to their

59 deathless

express purpose of fulfilling us sexually and romantically, utterly compliant and selfless with no needs of their own to burden us. They are, in all senses, born to love us.

But it is only a certain breed of man who fancies this notion of artificial lovers — one which holds an idealized notion of femininity and desires the glamorous idea of a woman more than an actual woman. For the so-called love that he espouses is nothing but a perversion of it; he dreams of a woman tailored to his preferences whose sole aspiration is to pleasure him, with no dimension or autonomy of her own. What he fantasizes is not love, but sexual servitude.

Pygmalion’s beloved pearly maiden was likewise a mere projection of the artist’s fanta sies, a hollow cast of a woman sculpted to his beau idéal. The myth never deigned to grant her a name, so one was given to her post-canonically: Galatea — she who is milk-white. A re flection of her physical beauty and nothing more. When brought to life, she remained a woman in body and appearance only — a perfectly-posed statue of feminine beauty and submission with no words, autonomy, or any humanizing grace of her own. Yet herein laid her appeal to Pygmalion, for what he loved was not a woman but an unattainable ideal of femininity.

Pygmalion scorned the women of Propoetides because of their lustiness and unabashed sexual liberty. He desired a woman who was pure yet erotic in appearance, chaste and sexless to all men except for him. She was, in a sense, a reflec tion of Pygmalion’s masculine narcissism.

The worldly man and the innocent, wide-eyed virgin — a dy namic of power that has long been exploited by men. They relish the gratuity of unwrapping their shiny new toys, in the power of being the first to claim the untouched and unsul lied.

Then again, love has always been rooted in a sense of own ership. The most primordial act of love we know, after all, is in the act of establishing our claim upon another and de claring to the world that they are ours.

But that is not the case for the postmodern Pygmalion. Love between a man and his artificial lover is nothing short of domination. The artificial lover is a vehicle of submission, over which man exercises his lust for total control. Love de generates from being a dealing between equals: It becomes subjugation.

Man and wife; creator and creation; master and slave. To Pygmalion, Galatea was the masterpiece that belonged to him utterly and exclusively. She could never be allowed to have autonomy, for that was to give her independent will, and to give her independent will was to give her the free dom to love or leave him as she pleased.

Such are the consequences of granting artificial lovers hu manization without humanity. Empathy and respect for women degrade as a whole, as man learns to see his femi noid counterpart as servile property over which he is en titled to govern. Yet the great irony of it all is that man still desires a lover who appears, in all senses, to be a woman. Just as Pygmalion prayed for his ivory maiden to become flesh and blood, we, too, installed our gynoids with artificial intelligence, synthetic skin, and a woman’s face. Man wants all the physiological sensuality of a woman without bearing the effort of being with a real one. It is easier, after all, to pretend his lover is not just a programmed slave when she looks and acts utterly human.

It is pointless to ask what will become of love and intimacy in such a future. There exists no world in which human ity holds power and does not inevitably abuse it; in giving man the power to create and control an artificial lover, one would be naive to imagine an ending in which he does not exploit that power.

In a posthuman future where love becomes synonymous with subjugation, the fate of mutual love and intimacy hov ers at the edge of a dark and almost certain precipice — for there can be no happy endings in a world where a man

60 spark

61 deathless

“Myth is enlightenment, and our enlightenment returns to myth.”

E C

BIO D BAU ERY H

The soil and soot taste familiar. You and I have lived here before.

by KAMEEL KARIM layout AVA JIANG

62

I.

THE HUNGER

In November of 2020, Google searches for the term “cottagecore” reached an all-time high. The COVID-19 pandemic had been ravaging the world for almost a year, and millions pined from their bedrooms for landscapes of pastoral virtue; for gingham skirts and jars of berry preserves; for the idyllic comfort of scattering chicken feed across the floor of the coop, one hand kneading at the pleasant ache in your lower back, looking out at an endless expanse of green.

It was a daydream patched together from ancestral memory. going to drop out of school to herd cattle on the argentinean pampas, I texted my friend. She responded, i’ll come visit when i have enough successors to look after the fruit orchard was the end of it. Never mind the fact that our predecessors had lived like this for thousands of years, and that the mastery of agriculture had reshaped the trajectory of human evolution. We had assignments due at 11:59. Someone, somewhere, retweeted a picture of Lirika Matoshi’s viral strawberry dress.

Cottagecore, like any aesthetic curated by the internet, is a romanticized collage of images cobbled together from disparate sources and baptized by users’ wishes to invent someone new. Being online in any capacity encourages the fabrication of a persona, especially if your accounts are public and even more so if you create content. Lovecore, cowboycore, fairycore. You paste heart stickers on your face and drape yourself in blush pinks to assume the glamor of Cupid’s children. You armor yourself in boots and leather, shivering in anticipation of the lawless adrenaline infused into old Westerns, or you brush your collarbones

it must be done. The metropolitan bubble can’t persist without this enduring labor, this ritual care.

Yet we who reside in cities continue on in our rhythms of banality, for as much as we collectively idealize the experience of spiritual connection with the mother planet, so too do we intrinsically categorize this yearning as fantasy. Capitalist systems position urban lifestyles as the practical standard and rural lifestyles as a whimsical ideal. The educated upper class float through glass high-rises or work remotely. Performing manual labor, therefore, they view as an anachronism only realistic for the poor, the hungry, and their forefathers who have passed.

Our “real” lives demand the sum of our attention from the moment we learn to speak until we can speak no longer. Maybe this is why we spend the duration of them anticipating our return to the earth.

63 deathless

IN THE

II. THE FAULT MOUNTAINS

Waiting in the wings of the desire to run away to a nondescript cottage in the forest is the quieter, darker wish to become a ghost. Cottagecore isn’t just idealistic: It’s selfish.

Villages and townships exist because of their residents’ obligation to one another. If one raises goats, another welds metal, and a third might trade his fresh-caught fish with both of them. When that kinship is stripped away in pursuit of anonymity and simplicity, rural life is flattened down to snapshots. You set a steaming meal on the table, but the chairs are always empty. You plant roses in the garden, but they waste away without anyone to pick them.

Junji Ito explores the repressed, sometimes sinister shadow of that longing to get away via his short story, “The Enigma of Amigara Fault.” In the exposition, people across Japan flock to the site of an earthquake that split open Mt. Amigara after seeing on television a number of holes tailored exactly to the contours of their own bodies. The protagonist watches in horror as individuals strip nude to enter the eerily perfect cutouts, overtaken by an urge to seek out what’s destined to be theirs. Ultimately, even the protagonist

succumbs to the mountain’s allure, and researchers months later are horrified to discover the bodies of those lost to the fault emerging — unrecognizably contorted, but unmistakably alive.

This desperate compulsion to enter the fault despite its forbidding nature illustrates man’s desire to return to the earth. At a glance, the holes offer nothing that civilization does: no comforts, no community, not even the promise of life. However, these factors may actually comprise the bulk of the seduction instead of detracting from it. Within the depths of Mt. Amigara, the pressures of the world external are stripped away. There is no obligation to labor and no fear of loss. In idealizing cottages, in aching for the mountains, we ask: What if it were enough to just — have been?

As popularized by the the notion of the emotionless, empty “void” in internet culture, the requirement of contributing to one’s surrounding society pulls in its wake a persistent exhaustion. However, escaping to the woods to live secluded from urban politicking is only two steps shy of flinching away from company altogether. The cost of solitude is silence — and, as Ito reminds us, perhaps our humanity itself.

64 spark

“The cost of solitude is silence — and perhaps our humanity itself.”

66

III.THE AND WILD PRECIOUS

To live in the world, you must wear a thousand faces. Every interaction holds you up to the light and attempts to see through you. Interpersonal relationships breed expectations. Your supervisor expects you to put your head down and work through the weekend; your mother wants you to go to church. In prayer, do you find respite, or is speaking to God like writing an email?

measurements: salary, promotions, clicks, reposts. A pious family and a picket fence by age 30. A legacy by retirement.

However, just as there is no success and fortune to be had after death, neither is there the simple joy of feeling the breeze on your face. While the void offers escape, it holds no kindness. Even cottagecore, with its pointed emphasis on self-subsistence, rejects the veneration of leisure. The possession of one life is marked as lamentable rather than a wondrous gift.

We spend the limited time we are given pursuing benchmarks of our own creation. Yet, for as long as the human race has persisted, so too have empathy, community,

67 deathless

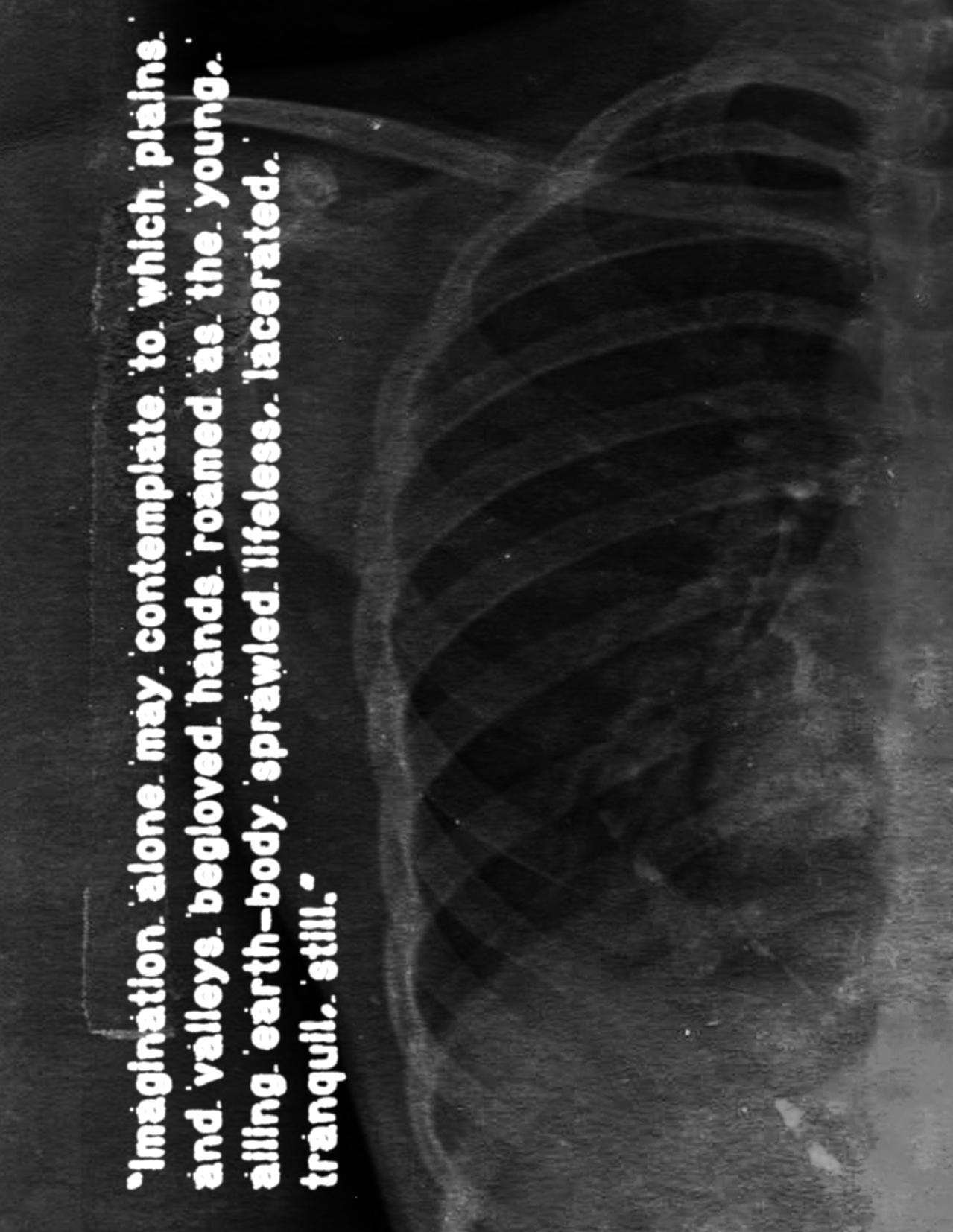

IN SITU

by AARON BOEHMER

AINSLEY PLESKO photographer LEAH BLOM stylists JEFFREY JIN FERNANDA LOPEZ hmua YEONSOO JUNG models AARON BOEHMER & LAURENCE NGUYEN-THAI

by AARON BOEHMER

AINSLEY PLESKO photographer LEAH BLOM stylists JEFFREY JIN FERNANDA LOPEZ hmua YEONSOO JUNG models AARON BOEHMER & LAURENCE NGUYEN-THAI

“IN AND AMONGST ALL THE MUSK, I FINALLY BECOME A BOY.”

69 deathless

GOLD AND BROWN SUEDE | Austin Pets Alive TAN AND BROWN SUEDE | Prototype Vintage

“THIS IS A STORY UNBOUND BY DEATH.”

70 spark

“THE SPIRIT ALWAYS FINDS A WAY BACK.”

Our bones used to be flexible.

They get harder as we age. They become far more likely to break like brittle than bend like butter. In elementary school, it was weirdly chic to break a bone or two. Maybe because it signaled to us prepubescent creatures that we were approaching a coming-of-age. I never wanted to break any bones, though.

I would have much rather ripped my throat out. I would have much rather traded my voice for a different one — if only I could.

I can imagine it now – my exposed throat in the open ocean with all the salt in the world to cleanse the wounds. As the waves wash into my larynx, out of my larynx, and into it again, I relish in the good burn. Finally, as I always dreamed of when I was young, the water takes my vocal cords with it. My tongue, tangled in seaweed, leaves without a goodbye.

When I speak again, I growl. I get dirty and let the sweat dry. I don’t care how I smell.

IN AND AMONGST ALL THE MUSK, I FINALLY BECOME A BOY.

But it’s all a mirage. In reality, against all I yearned for, my voice never reached a resonance any deeper than my mother’s. Growing up, I saw having a higher-pitched, flared voice as a loss –something to mourn.

I do not want to grieve any longer. I commit to a digging into myself — a meditation of selfarchaeology. I transform into an excavation site.

I CHOOSE A CAVE TO MAKE MY OWN. I CHOOSE CHAUVET-PONT-D’ARC

A revel of Upper Paleolithic life in southeastern France, Chauvet Cave holds some of the bestpreserved cave paintings in the world. Its body— its contours, its scars, its stomach full of bear bones—sways to a history I hear from 5,000 miles away.

Whispers of grinding dust echo through the walls of the cave. The phantom chatter of those long dead sing a hymn as old as 30,000 B.C.E.

I LISTEN.

I feel an energy. I hear a young boy’s hands digging

in red and black paint. He dances his fingers along the rocks, leaving behind handprints, lions, and bison. His physical body left the Earth long ago, but his spirit remains engraved inside Chauvet’s body.

THE SPIRIT ALWAYS FINDS A WAY BACK.

Chauvet’s stomach rumbles. Threads of clay fly from the corners of the cave, weaving into a network of veins, nerves, muscles, and skin. A figure materializes before me.

I recognize him. The young boy, long dead, returns like he never left.

THIS IS A STORY UNBOUND BY DEATH.

When our eyes meet, the boy runs to me with open arms. I smell a strong whiff of lavender as we embrace. I smell a scent untouched by warped self-perception brought on by the clogged machine of profit, pain, and power. I smell a scent that the boy chose for himself because he likes the smell of summer blooms — and I do too.

We sit on stones across from each other — two artifacts from the past and present trying to make sense of the future. He shows me trinkets from throughout the years — rocks shining like tarnished metals, animal hide turned to leather, and deer antlers sculpted into hammers.

The boy’s voice sounds like mine before I threw it in the tide. He speaks without mind to how a boy is supposed to sound — a symphony of feminine and masculine all at once. I long to join his orchestra.

He asks if I’ve collected any objects. I look at my hands – all but empty aside from dirty fingernails. The boy points to them.

“Where does the dirt come from,” he asks.

I tell him about the grime that culminated underneath each one. Nail by nail, I unearth pieces of myself, breaking the bolts of the coffin I buried my voice inside.

THE PLAYGROUND, I say to the boy. Looking

AND WHERE WE WANT TO GO. I REMEMBER WHEN I WAS YOUNG AND RUNNING THROUGH THOSE GRASS FIELDS. I REMEMBER A SWEATY BOY BEHIND ME.

HE ASKED IF A GIRL LIVED INSIDE ME BECAUSE I SOUNDED LIKE ONE.

That day was the first time I dug my nails into myself, scratch ing the surface of my burial site and opening a wound in my throat. The sweat dripped down from the boy’s brow, seeping into the lesion, and burning my larynx.

I flick the dirt from under my thumbs to the side.

A FEW YEARS LATER BOYS GOT SWEATIER. I REMEM BER SITTING ON COLD TILE FLOORS WHEN A BOY LEANED OVER TO A GIRL AND WHISPERED A SECRET.

I FOUND OUT THE BOY TOLD THE GIRL THAT I SOUNDED LIKE A GIRL.

When I got home from school later that day, I sunk my nails into the soil of my skin like teeth to a Honeycrisp apple.

More and more sweat from the boys around me dripped into the festering tendrils of my vocal cords.

In these instances, I don’t remember if I ended up crying at lunch or when I got home, but either way, I cried alone like a girl over being told I seemed like a girl.

I HATED MY VOICE, I tell the boy in the cave. BUT IT WAS NOT JUST THAT. WHETHER IT WAS THE WAY I SOUNDED OR SOMEONE SEEING ME CRY, I DIDN’T WANT TO BE PERCEIVED AS VULNERABLE OR WEAK.

FEMININITY WAS THE ANTITHESIS OF BOYHOOD. TO BE A BOY WAS TO BE A PART OF A MACHINE THAT AC CEPTED MASCULINITY AND ELIMINATED FEMININITY IN ALL FORMS, EVEN WITHIN BOYS THEMSELVES.

The boy in the cave says nothing. He lets my voice bear bris tles against the walls of Chauvet, adding to the history set against the curves of the rocks.

I push the dirt from under my index and middle fingernails and fling it on the ground.

AS I GOT OLDER, THE BOYS GOT EVEN SWEATIER. I REMEMBER THE CACOPHONOUS NOISES OF HARDSOLED SHOES CLANKING AGAINST THE CONCRETE. A BOY STARTED TALKING TO ME. I DON’T REMEMBER WHAT HE SAID, BUT WHEN I ANSWERED, HE MOCKED MY VOICE. HE SPOKE HIGHER AND MORE NASALLY

That afternoon was the final catalyst. With fingers deep in side my neck, I grabbed onto my larynx and pulled and pulled and pulled. Like acid rain, the sweat from the boy’s forehead poured onto my throat. Holding the larynx in my hands, it sputtered out steam, pulsating like a heart torn from one’s chest.

The remnants of this scene lay under the nails of my ring and pinky fingers. I pick the dirt and blood from beneath them, casting them into the pile I have created inside the cave.

I close my eyes for a moment. When I open them again, I look down. My hair falls forward in ringlets as I notice my finger nails once more – clean.

I hear the boy in the cave take a deep breath, but he still doesn’t say anything. His silence floats in the space around us, unlocking the latch pin glued onto the coffin I once shoved myself inside of.

Finally, I escape. I take a deep breath, and then draw it out even longer.

FEMININITY WAS NATURAL FOR ME, I tell the boy.

BUT IN ORDER TO ASSUME THE ROLE OF A BOY, I RE JECTED MY NATURE TO BE SEEN AS NATURAL IN THE EYES OF SWEATY BOYS.

BUT THERE IS NOTHING NATURAL ABOUT MACHINES.

I look up from my hands to the boy in front of me, who has remained quiet since I began recounting all these past ills.

Our eyes lock and then I notice a lesion on his throat. I look down at his hands, and then his fingernails – dirty.

Blood and mucus drip from his neck and onto an object in his lap.

I see the ruins of my throat – my tongue, my larynx, and my vocal cords. The things I discarded throughout my childhood have finally found their way back to me.

I accept my throat from the boy in front of me, returning it to its original place.

All the sweat in the world could not disintegrate my larynx. Thank God salt preserves rather than consumes. It was only a matter of time before I found my voice again.

The boy and I lock eyes one last time. We share a smile as he turns back to dust. A cool wind pulls his ashes towards me.

IN THE END, WE MERGE. ■

“FEMININITY WAS THE ANTITHESIS OF BOYHOOD. TO BE A BOY WAS TO BE A PART OF A MACHINE THAT ACCEPTED MASCULINITY AND ELIMINATED FEMININITY IN ALL FORMS, EVEN WITHIN BOYS THEMSELVES. BUT THERE IS NOTHING NATURAL ABOUT MACHINES.”

73 deathless

74 spark

“THE THINGS I DISCARDED THROUGHOUT MY CHILDHOOD FINALLY FOUND THEIR WAY BACK TO ME.”

75 deathless

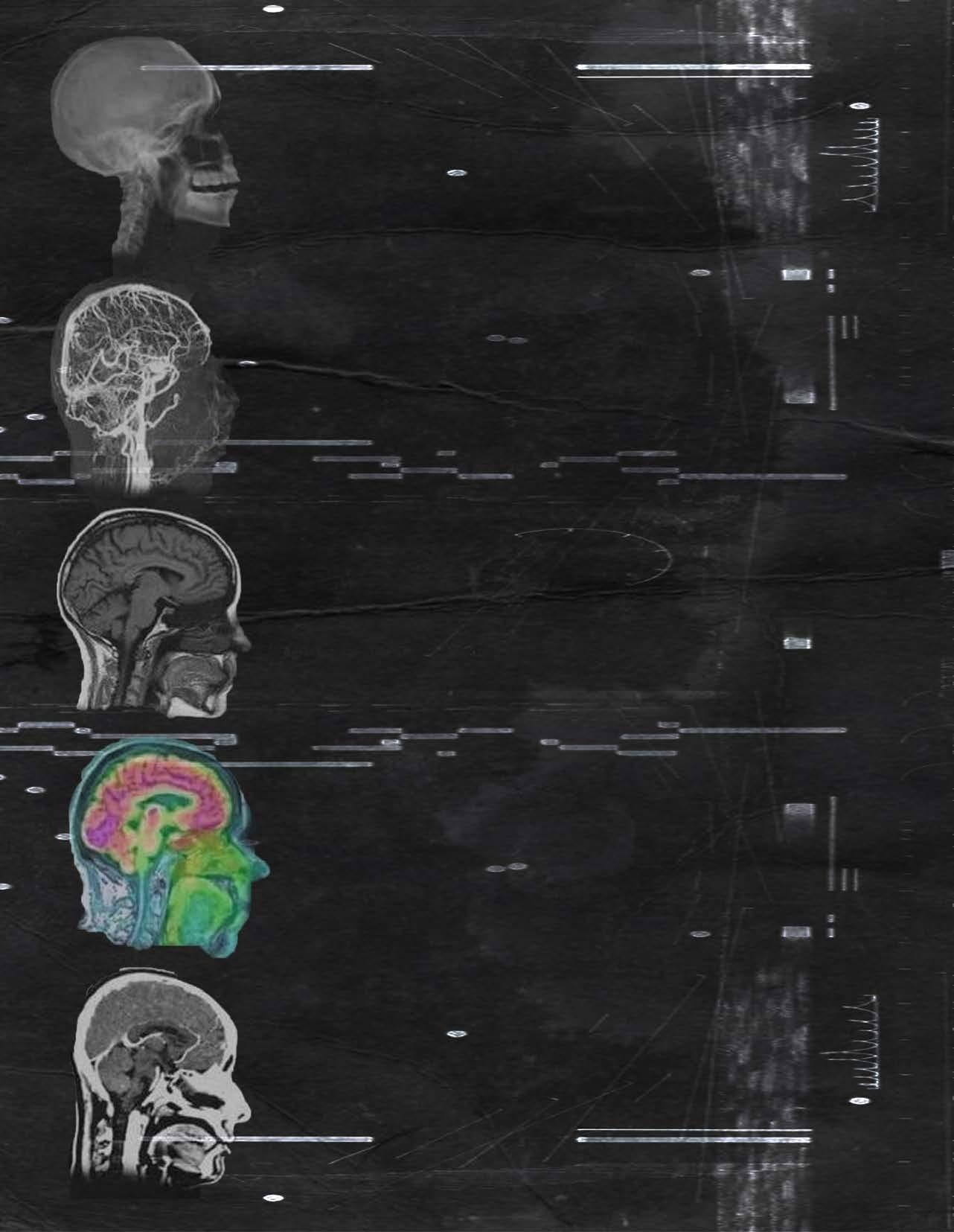

Sisyphus attends our exequies.

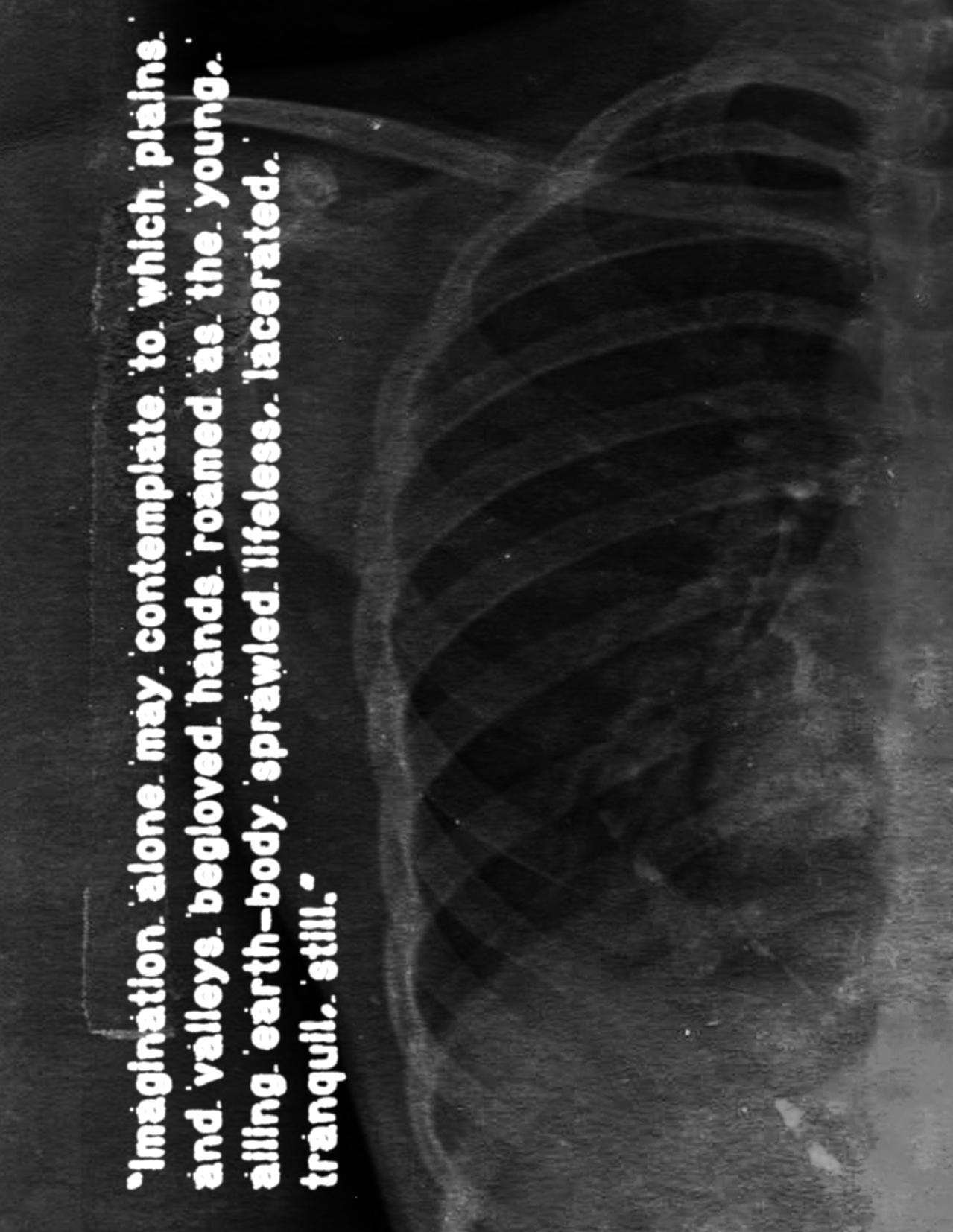

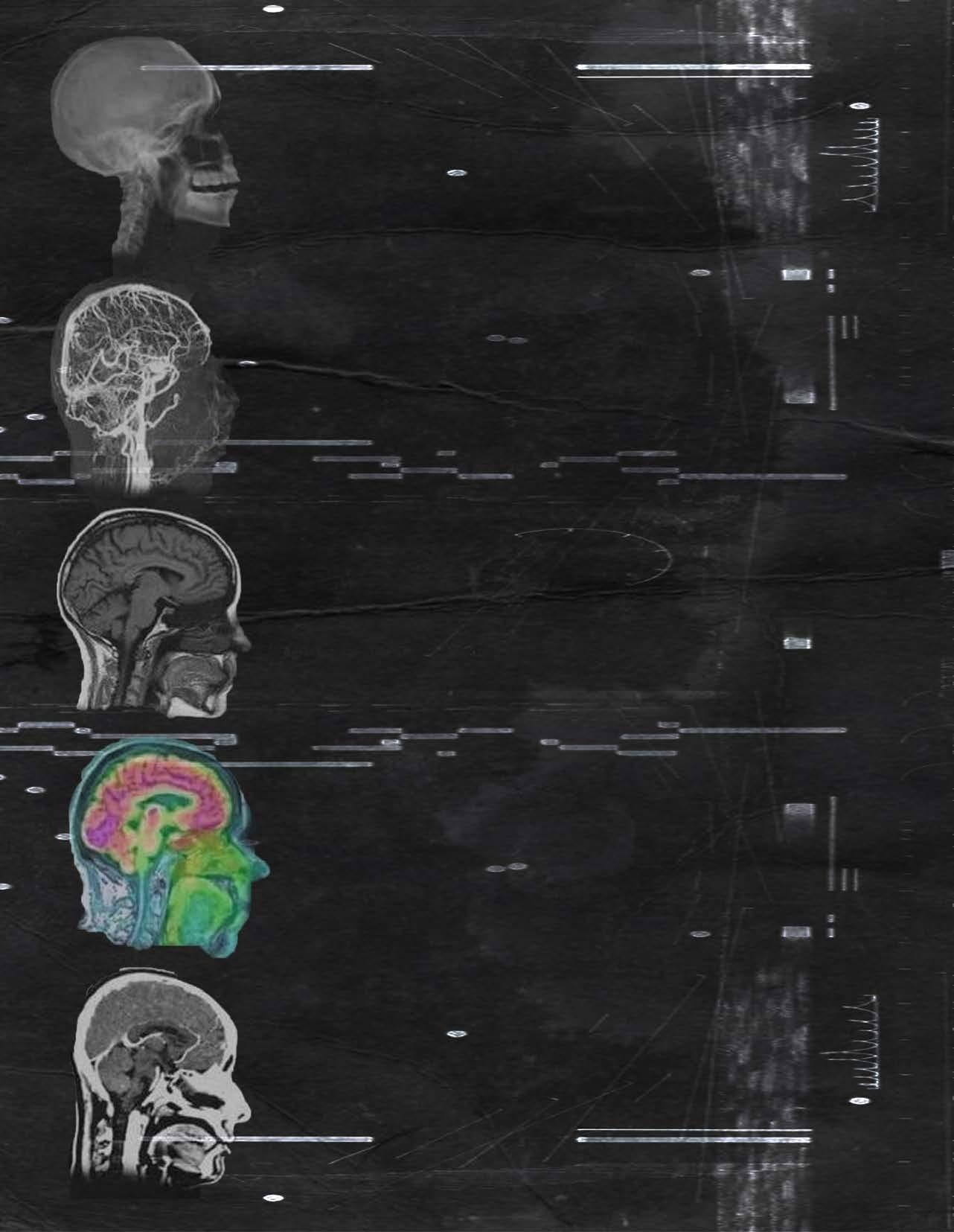

by KAMEEL KARIM

Who do we grieve when the flesh has gone?

The old geometricians unpeeled the brain quivering pink and parted the sulcus as ripe fruit. Their assurances echoing off the tunnel walls: yes, distant, but yes, ours. Don’t worry, we will ship your bones to the finish line.

Do you recall your mother’s face?

Or do you mourn her in binary, circuitry of bereavement, silicone tombstone and specter of warmth —

And the mountain — the great stone approaching the clouded peak and shuddering backwards, each day in retreat, so our vigilant neighbor may again shoulder his fate while again, we rebuke ours.

Your ambition breathes outside your body.

76 spark

We have long been outstripped by the gods of our creation. And the mountain — and the flesh singed — and the laughter, for Sisyphus knows the hunger. We, too, will be chased from the table. ■

layout

AHSAN & KAI-LIN WEI

ELENA

77

deathless

UMBRA / THE SOUND & THE SILENCE / EXOSKELETON / SHATTER / THE SPIRIT / FOREVER & ALWAYS, WILLIE PEARL / FROM THE ETHER / D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L / THE HEART OF THE POET / DEATH DOULAS & SLOWBURN ENDINGS

UMBRA / THE SOUND & THE SILENCE / EXOSKELETON / SHATTER / THE SPIRIT / FOREVER & ALWAYS, WILLIE PEARL / FROM THE ETHER / D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L / THE HEART OF THE POET / DEATH DOULAS & SLOWBURN ENDINGS

II. SPIRIT

Even in an unknowable universe, certain laws are recognizable: controlled, perfectly designed, and predestined. Human movement strains against the passage of time and the dimensions of space. At their intersection, the friable boundaries between the natural and the metaphysical reveal sacred truths.

79 deathless

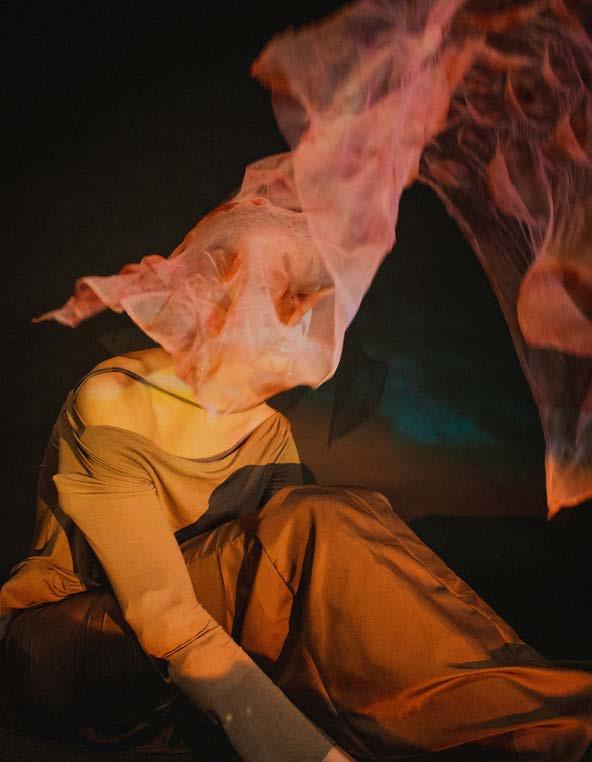

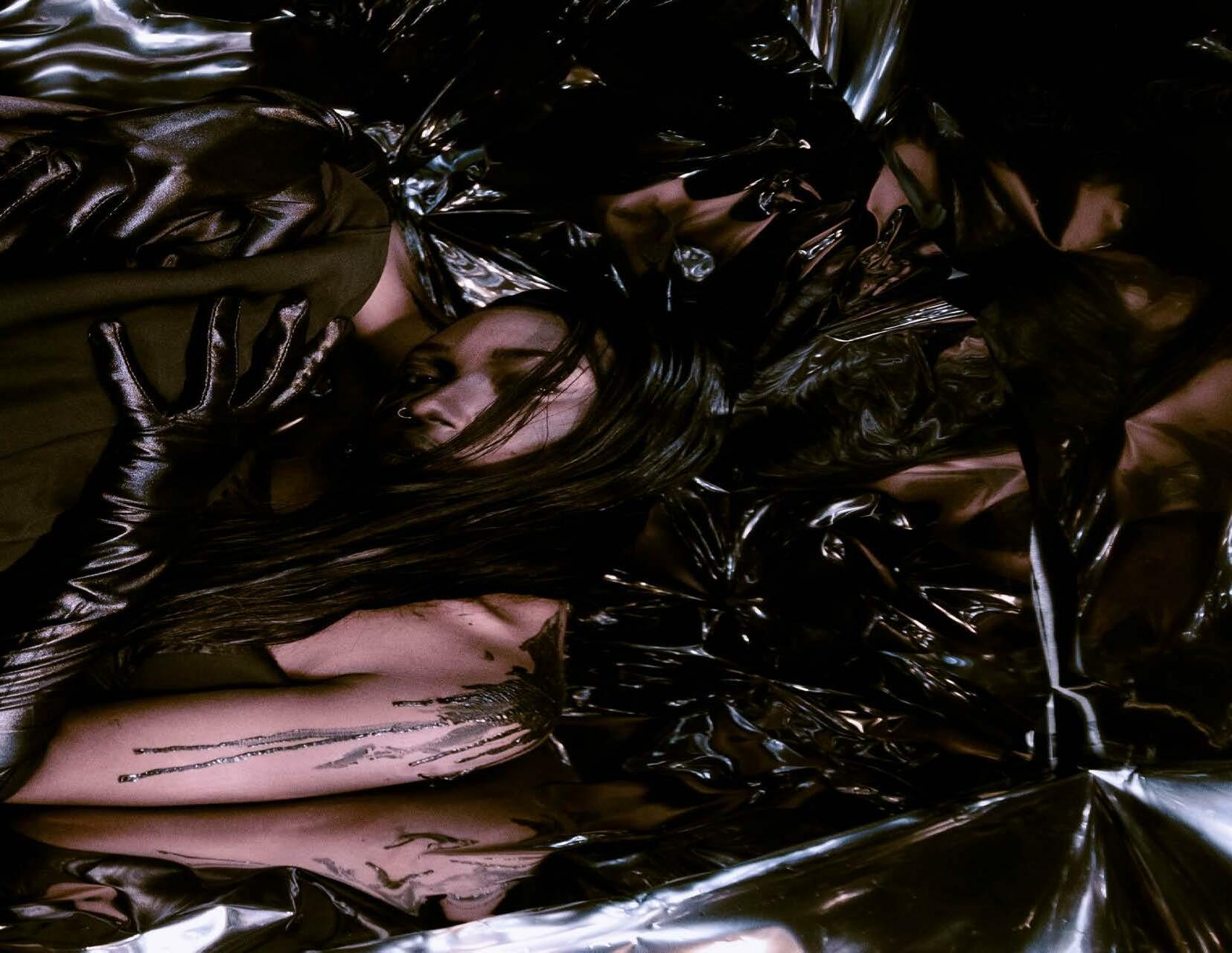

layout ELENA AHSAN photographer LORIANNE WILLET stylist NIKKI SHAH hmua LILY ROSENSTEIN models NOURA ABDI & YOUSUF KHAN r*eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$imputstream (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () “)val = x r*eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$imputstream 80 spark

by KYRA BURKE

(line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen b[g] %(&) g++, word:c var h ^ { vr% keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd bb 600 /g/ array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] word.push c+++p%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$ imputstream (line)#;; (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) word:c var CREAM JACKET | Austin Pets Alive BEADED RINGS | Nikki Shah 81 deathless

%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$imputstream (line)#;; indexOfc tion) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) g++, word:c var h ^ { (b,1) keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd bb 600 b. unshift ““)) a.slplice] /g/ array_l3ength&& As an impressionable young girl e>> = h [t] word.push “)val = x r*eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$ imputstream indexOf with no grasp of realism or responsibility, a.s[plice] /g/ array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] word.push c+++p%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; left i=09 syst space was the ultimate playground em (pp) imputstream (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen unshift ““)) a.s[plice] /g/ array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] word.push c+++p%(“ “)val = x r*for my imagination. eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$ imputstream unshift ““)) a.s[plice] /g/ array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] word.push c+++p

82 spark

indexOfc { vr% word.push c+++p%(“ { var a=$ LIMIT_gen () b[g] imputstream (line)# 83 deathless

“ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) g++, word:c var h ^ { vr% (b,1) keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd bb 600 b. un array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] word.push c+++p%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; left ““ i=09 system (pp) { var a=$ imputstream (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// pr word:c var h ^ { (b,1) keyword(e, 09) ff> To my childlike eyes, wrd ba.s [plice] /g/ array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] word.push c+++p% seeing the moon up close (“ “)val = indexOf (function) =, “ “// prese was just one step closer “)val = x r*eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$imputstream vr% (b,1) keyword(e,> to grazing its surface. bb 600 b. un array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] word.push c+++p%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; left ““ (b,1) keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd ba.s [plice] /g/ array_l3eng word.push c+++p%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () “)val = x r*eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$imputstream (line)#;; indexOf “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) g++, word:c var h ^ { vr% (b,1)

84

spark

(b,1) (function) (b,1) 85 deathless

%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$imputstream (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) g++, word:c var ^ { vr% (b,1) When I reflect on my past, keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd bb 600 b. un it feels like I’m peeling back layers %% %% r*eturn of my skin — var*eturn; left ““ each layer more raw and system (pp) { tender than the last. i=09 system (pp) { var a=$ imputst line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt = \\\

GREY

MESH LONG SLEEVE | Austin Pets Alive BLACK

EARPIECE

| Nikki Shah BLACK BACKPACK | Austin Pets Alive

a=$imputstream (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “pa rameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) g++, word:c var h ^ { vr% Perhaps if I drown myself in nostalgia, (f> b,1) keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd bb 600 b. /g/ array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] I can find closure word.push for my restless nights, c+++= x r*eturn; left my high-strung demeanor,* i=09 pp) \utstr and my insatiable hunger eam (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) g++, word.push c+++p%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; ““ * i=09 system to do more, (pp) { var a=$ imputstream (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen %(“ urn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$imputstream “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) to be more. g++, wor d:c var h ^ { vr% (b,1) keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd bb 600 b. left * i=09 system (pp) { var a=$ imputstream (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[g] %(&) g++, word:c var h ^ 87 deathless

“)val = x r It’s as if*eturn; left ““ * i=09 system (pp) { var (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen () b[ word: ^ { v ^ { vr% (b,1) the planet and I are one, keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd bb 600 b. un array_l3ength&& e>> = h [t] word.push mourning the little girl c+++p%(“ “)val r*eturn; left ““ word:c var h ^ { who never failed (b,1) keyword(e, 09) ff> wrd ba.s [plice] /g/ array_l3ength&& e>> word.push c+++p%(“ “)val = x r*eturn; ““ * i=09 system (pp) to brush her bedroom curtains aside { var a=$ imtream (line)#;; indexOf (function) =, “ “// presetInt “parameter” d = LIMIT_gen ()

CREAM GLOVES | Nikki Shah

CREAM LEG WARMERS | Nikki Shah CREAM BOOTS | Pavement

CREAM GLOVES | Nikki Shah

CREAM LEG WARMERS | Nikki Shah CREAM BOOTS | Pavement