SPIRES

Copyright 2022, Spires Magazine

Volume XXVIII Issue I

All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from Spires and the author or artist.

Critics, however, are welcome to quote brief passages by way of criticism and review.

This publication was designed by Jordan Spector and set into type digitally at Washington University in St. Louis.

Typefaces used are Kings Caslon, designed by Dalton Maag Design Studio, and Montserrat, designed by Julieta Ulanovsky. Caslon was originally designed by William Caslon.

Spires accepts submissions from undergraduate students around the country. Works were evaluated individually and anonymously. Spires is published biannually and distributed free of charge to the Washington Univeristy community at the end of each semester. All undergraduate art, poetry, prose, drama, song lyric, and digital media submissions (including video and sound art) are welcome for evaluation.

spiresmagazine@gmail.com spires.wustl.edu facebook.com/spiresintercollegiatemagazine instagram.com/spiresmagazine_wustl twitter.com/spires_magazine

Maggie Baumstark Genesis 1 [Redacted]

Kaleb Bryan We will keep you alive in us.

Lilly Chipman Agarita Jelly

Isabella Thompson Ritual Nostalgia

Fatma Omar October 3rd

Mia Huerta [mother]

ART

Nathaniel Kolek Lounge of Lizards

Andrew “A.J.” Takata Outsider Mac Barnes H.T. 02/23/2021

Omeed Moshirfar 7/9/22

Rachna Vipparla reaching for help

Annette Zhao one hundred dumplings

Christiana Sinacola To Ask the Ocean

Maureen Diehl seasonal reflections Maya Tsingos Little anarchies

Mac Barnes

B.S. 07/20/2021

Gabrielle Buffaloe Professor Katelyn Allen Luck

Adrian Oteiza Mirror Image Rachna Vipparla rainy day

Temi Ijiesesan Playground

Washington University in St. Louis ‘26 Digital Illustration

FRONT INSIDE COVER

FRONT COVER BACK INSIDE COVER BACK COVER

Madison Fang

The Never-Ending, Part 1 Washington University in St. Louis ‘24 Print

Madison Fang

The Never-Ending, Part 2 Washington University in St. Louis ‘24 Print

Madison Fang

I Am Eating, Jessica Washington University in St. Louis ‘24 Digital Illustration

Anna Bankston

Amy Hattori

Hanah Shields

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Alexis Bentz

Lara Briggs

ART EDITOR

Campbell Sharpe

LITERARY EDITOR

Mahtab Chaudhry

LAYOUT EDITOR

Jordan Spector

TREASURER

Olivia Salvage

PUBLICITY DIRECTOR

Kimberly Buehler

Jeffrey Camille

Shelby Edison Kate Gallop

Jaime Hebel Rosie Lopolito

Sophie Ma

Mikki (Michaela) Marcille Sophia Marlin Keya Nagula Caroline Sarris

RL (Rachael Lin) Wheeler Grace Woodruff

Dear Reader,

With life slowly returning to normal, Spires Magazine was able to return to campus traditions to promote an issue for the first time in three years. From painting murals to providing tea and scones to students on campus, our staff was ready to do whatever it took to spread the word about our beloved publication. Club fair was exciting—we were able to watch new students discover the magazine for the first time, flipping through copies and taking them home to show their roommates and friends. We had many veterans on staff this year, yet remain thrilled with the addition of new faces and voices to the Spires team. With every new staff member comes the opportunity for new opinions and nuanced viewpoints surrounding our submissions. It is thanks to our incredible staff and all of our wonderful writers and artists that the Fall 2022 issue has been so carefully crafted.

This semester’s round of submissions elicits themes of family and generational conflict, mental health, spirituality, and the natural world. We were so honored that our undergraduate writers entrusted us to engage with these personal and often difficult topics impacting our generation, and we hope this edition provides solace and a sense of community for those who have experienced these themes in their own lives, or a sense of empathy and artistic connection for those who have not. Our desire as editors is that you find the pieces in this issue to be as impactful and moving as we do.

With a new executive board taking over this semester, Spires staff fondly remembers the dedication and leadership expressed by previous editors-in-chief, Brianna Hines and Lexie von Zedlitz. As our new team works together, we begin to imagine exciting new plans for future endeavors of the magazine and explore the possibilities of expanding its creative expression and outreach. Thanks to the dedication of our executive team and editorial staff, we have explored new avenues to broaden both the logistic and creative boundaries of our publication and platform.

We are thrilled to share the skilled submissions from talented artists and authors in this edition of Spires, and as always it has been an absolute privilege to review the creative works of undergraduate students all across the country. With each edition of the magazine, we continue to be impressed by the work of our staff members and the imagination of our contributors. We hope our readers are just as enthralled with these extraordinary pieces.

Sincerely,

Anna Bankston, Amy Hattori, and Hanah Shields Editors-in-ChiefI was formed from the rib of my mother’s irises, tube-fed cobalt and Mozart.

I crawled out in soot and attempted-tears because I saw the world smoking and anguishing in growing pains and so I thought me too.

I was born whole, save my fingertips: unpressed charcoal tributaries cool embers from a future fire I would try to light. But Mom, you held them to your lips and called them stardust.

Ashes to ashes, supposedly. I’ve always hated the name Adam.

A serpent of my own skin wiping the juice from the corners of my mouth a damn good piece of fruit sickly sweet fingertips rinsed in the reflection pool of someone who looks tip-of-the-tongue familiar but too much of a stranger to know.

Mom, do you recognize me?

What color are my eyes now?

For 7 days and 7 nights the Ocean was given a hack-job C-section called Pangea and a scar that never quite healed called me.

and when the Good Light washed over me on the fourth day and I could see the sheen of my serpentine skin feel the headache of the sapphire trying to flee my eyes taste charcoal fingerprints on the skin of this goddamn forbidden fruit

I learned how to cry.

MAGGIE BAUMSTARK

WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS ‘25

Oh da ono! Real brok’ da mout’!

Thank you, Aunty.

It’s night during the eternal summer. Floodlights caked in mosquitos brighten the driveway. Here, at Aunty’s house on the edge of Hilo, Coqui frogs – what Aunty calls “so ‘nnoying,’’ chirping their who-wheet in the bushes and grass by the hundreds, thousands, an invasive species, foreign, haole – are my favorite. We both came to this island from our homes for different reasons. We’re both outsiders.

I scoop a second helping of the curry and rice for Aunty. It’s reassuring to see her eat enough at her age. Color returns to her sagging skin. It’s the first meal I’ve cooked since Mom left to make Grandpa’s funeral arrangements.

Oh, thank you, son!

I’m your grandnephew.

Oh, das right. When did Grandpa die?

Your grandpa, or Jimmy?

Yeah, Jimmy.

Jimmy is my grandpa, your brother. He’s been dead for two weeks.

Oh, das right. You still go school?

Yes, Aunty. Where?

On the mainland, Aunty. Those mainland ac’ funny kine yeah? What does that mean?

They ac’ funny kine, you know?

Oh. No, they’re not weird, they’re my friends. This food good, ya?

Thank you, Aunty. *

It’s the beginning of the summer. I’m home in California and Mom is eight months away from her “regular” visit to her father, Grandpa, and Aunty Michi, his sister. Mom hangs up her $200 Samsung J3-6 smartphone that she hates because it’s slow and unreliable, but the one time she might have hoped that the receiver was broken again and she misheard something the phone was clear: Grandpa, heart attack, bathroom, ambulance, hospital, unconscious, Hawai’i. Mom – who grew up in Hawai’i with Grandpa – becomes more pidgin by the second.

Want come with? Try pack bag.

*

The English name Great Grandpa Charles gave Grandpa was Stanley, after the brand of tools. Stanley tools were the finest tools one could buy, so he named his kid after a shiny box. But Aunty always called Grandpa “Jimmy,” short for his Japanese name Hajime – meaning beginning, origin, or first. When I was young, I learned about him through triannual phone calls from California. The start of my pilgrimage to Grandpa was school and funds permitting, or if my six-year-old-self was being a brat that day. I was scared that I could never understand what he was saying, English, Japanese, or Hawaiian pidgin. When I was 18, a blood clot meant the amputation of Grandpa’s right leg and he was confined to a wheelchair in the narrow house. My last memory of Grandpa when he was alive was a ninety-year-old man rolling himself forward a half inch at a time – he didn’t want to be pushed – transferring to the couch, performing his physical therapy with a one pound dumbbell, reading the newspaper cover to cover, and falling asleep. We watched TV in the living room together. When I watched Futurama, he would doze in his seat, but when I switched to Sean Hannity, he would sit up and stroke his chin. We didn’t say a word.

*

It’s da kine day, a day you photograph for a postcard. Mom is making funeral arrangements with Aunty in the office, and I stand on the shore. The waves are turquoise and the sky never felt so grand. I can pride myself on not having haole feet – needing rubba slippas for hot sand. Perhaps here, what my ancestor King Kamehameha the Great (who almost certainly isn’t related to me but Mom believes so) felt on a day like today, I can understand the words and phrases around me. And yet, Hawaiian pidgin – what it means to be “local” – slips away from me like the sand when I clench my toes. Pidgin is a badge with a volcanic sheen to wear with pride against the haoles, the tourists, the colonizers. When you’re used to the bulldozing of the jungle and birds for golf courses, skyscrapers vomiting oil into the bay, timeshare land owners complaining about tourists “taking up all the space,” where the betrayal of Queen Liliuokalani by the American military was not forgotten, making fun of haoles behind their back is the only thing you have left. But when I use pidgin it’s a broken slippa’, syllables clogging my mouth, pronunciation that brands you a haole.

It’s sunny and Grandpa died today. Hilo rains as often as you blink, but, today, where a dramatic rainy day of mourning in the hospital would have been fitting, the sun shines. He never regained consciousness after his heart attack. Mom is dry-eyed. When a haole expresses sympathy, they might say, That’s very unfortunate, I’m sorry to hear that. When a local expresses sympathy, they might say, Wow! BUMMAHS, man! I try not to laugh because Grandpa is dead. Grandpa is dead and all I can think about was when, years ago, Mom forced Cousin Emily and my sister Catherine to attend Kamehameha School where they indoctrinate children into indigenous Hawaiian life. The school is a cultural revival of a people exploited for centuries by colonizers, but, in practical terms, it meant they bussed Catherine to the east side of the island at 4:30 AM so they could be the first ones to greet the sun god. While they were standing, Emily intentionally locked her knees and fainted so they could leave sooner. Today was the sun god’s revenge.

*

Grandpa has been dead for two weeks and Mom asks me to caretake for Aunty. I am 19 years old. *

It’s past my bedtime but, for once, I’m happy. I have to sleep early because Aunty wanders in the night and becomes distraught if she catches me awake. There’s no Internet reception at Aunty’s house, but there is cable TV, and I watch network-curated Hawaiian features with Tomoe brand spicy arare rice crackers in one hand and Kona iced coffee in the other. It’s the South Park episode “Going Native” where Butters “returns” to his white Hawaiian family. Or as they say Hawai’i – pronounced ha-’vai-i. The family eats “traditional Hawaiian foods” such as drive thru saimin noodles. They live in “traditional dwellings” such as paved, gated communities. And most importantly, these “native Hawaiians” look down on haoles, because how could they themselves possibly be haole? Butters’ family doesn’t realize there’s a word used only by haoles to refer to a longtime foreign resident, kama’aina.

It’s the first time I’ve laughed that summer. Few methods of appearing haole are as swift as thinking you can pronounce Hawaiian words. South Park is making fun of the people who overpronounce Hawaiian words, who believe they are the descendants of tribal royalty, who believe they are Hawaiian because they vacation there once a year. It’s making fun of me. And then I was angry, because I knew even though I was fifth generation Japanese Hawaiian, all the blood on the island couldn’t replace experience or a tongue. What hurts isn’t that I am different, but that I

almost could have been the same. The Coqui frogs chirped in the night – outsider, outsider. And then I laughed again.

*

It’s the day of Grandpa’s funeral. It’s halfway through the summer and the rest of my family arrived from California a few days ago, Mom, Dad, Casey, and Catherine. Nothing about it seems natural. Mom is all smiles as she greets locals who came just for her. Look, this is my seventh grade teacher! She taught my English class. And this is Aunty Cathy she looked after you kids when you were manini. And this is…

I can’t – cannot, as locals would say – understand the words. The pidgin Mom unloads onto the guests forms a mist around the casket. Grandpa looks like a stranger. We hold a colorful funeral. Casey is wearing his National Guard dress blues, Catherine is wearing a scarlet dress with flower print, and I’m wearing the aloha shirt Dad wore for his wedding rehearsal 30 years ago. Dad wants my siblings and me to stand in front of the open casket so he can take a picture. We all think that’s a bad idea.

Mom pulls Casey and me aside and whispers: the other four pallbearers are Grandpa’s golf friends, so they’re all ninety year old, five foot tall Buddha heads. Well, fuck! we reply.

Try find way to carry the weight, she says, because I’m not sure how much his friends can help.

After the service, we take our places, I at the back corner, Casey on the opposite front corner. We lift the casket. We almost immediately drop it. Grandpa was a small man, but this casket must weigh 250 pounds. The six of us shuffle and huff our way out of sync to the hearse. We’re terrified of dropping Grandpa on the ground. I try not to laugh. I imagine what Grandpa would say if he knew this was how his funeral would go. Then I realize I don’t remember the sound of Grandpa’s voice. We shove Grandpa into the hearse and I’m ready to thank the old gods that hearses had the foresight to place a wheeled ramp inside the trunk so the casket slides smoothly into the car rather than us lifting and dragging until we could slam the door shut. Grandpa’s golf friends look dangerously tired. Their exhausted groans talk about try go Cafe 100 when this pau, yeah?

Memories, stories about Mom or him or Aunty, about Great Grandpa Charles, are all sealed in that mahogany box. The coffin’s varnish has a volcanic sheen. I look at Casey and he gives me the same look back.

It’s the day my family arrived and we spend the afternoon at the beach. The funeral is tomorrow, but the ocean is calm. Mom, Dad, Casey, Catherine, and I kneel by the tide pool because the honu – sea turtles – swim right up to you to nibble on the sea grass. We sit three feet away and watch them graze against the lapping waves. Dad takes photos of us with the turtle but does not include himself in the picture. Mom watches the other local kids lower on all fours, squint at the turtle, get bored, and run off. Casey digs at the sand with his extra-large rubba’ slippa’. Catherine records a video for her boyfriend. No one says anything, neither English nor Japanese nor pidgin nor disjointed memories. Yet I can understand everyone perfectly.

When I bend down in fajr, I half expect to see white shoes in my periphery. Better yet, white feet that glow from an internal, infinite source and I half expect it to walk over once I give my peace. It is kind to wait till I finish but could you not wait at the door?

My olive oil mat is not big enough to prepare for death and my room with a constant draft that I must wrap myself from. Could you not wait at the door, shoes off and face patient? Could you not wait for me to fold my mat and change into a better dress. I could not fit myself into six rak’ahs and the last passage was rushed.

I don’t believe I even asked for you to come so soon but now that you are here you must wait for it to stop raining.

Don’t you know souls dampen on their way to the sky? And look at my sheets, they have come undone and my desk still holds yesterday’s oatmeal bowl.

In truth, I did not want you to come so soon, could you not have sent a letter? I got off the phone with my mother with the usual “peace be with you” and my father’s “bless you” and my sister’s “the paper is due tomorrow I need your help” and my brother’s “we have to get dinner soon” but I did not call my cousin.

(mother wake up!) mother wake me— i think behind puffy eyes. no,

[mother] mother

Let me sleep in hazes of groggy Half-conscious states, you crowd my vision like the blossoms of orange & lilac bougainvilleas that we walked through ages ago. you still feel the same, the soft warm welcome of golden metal curls; you hate their frizziness, their obvious repel, but something must snap back on your small person. mother come closer, do not leave— i reach out with chubby hands, gripping at your linen shirt of our homey mondays. buried in your bosom, my snotted sniffles of heartbreak dissipate, a feverish cold tastes of sweet orange syrup, monthly aches of my small bones find refuge in the cushions of your warmth, and it still smells of moroccan oil and coconut. night fall rushes faster in these parts of the world, january bites harder. sing me to sleep, in soft lullabies of wispy snow, and rhythmic comings and goings of the wet tires on the road. if i close my eyes and cry hard enough, the swishes of tires sound like summer petals dancing by.

I’d never been to rural Pennsylvania before you brought me, but you were right, it is beautiful.

It is far emptier now, at least far more than it was before, on account of your absence today. Under fair blue skies, with the Susquehanna winding around this church like a cradle. You always said you’d bring us out, show us the river, show us the hills, show us your home.

It is far emptier now, at least far more than it was before, on account of your absence today. There’s one extra spot in the call now, the party goes on, everybody wants to talk about it. You always said you’d bring us out, show us the river, show us the hills, show us your home.

So, we do what you no longer can. We were out in those hills; we would keep you alive in us.

There’s one extra spot in the call now, the party goes on, everybody wants to talk about it. How desperately we wish you could see this place, how much we missed your company. So, we do what you no longer can. We were out in those hills; we would keep you alive in us.

On some fire-lit evening in Appalachia, we relived the years we’d been gifted to have with you.

How desperately we wish you could see this place, how much we missed your company. You were always the rock of the group, the one we could lean on, and even now, you still are.

On some fire-lit evening in Appalachia, we relived the years we’d been gifted to have with you.

I’d never been to rural Pennsylvania before you brought me, but you were right, it is beautiful.

KALEB BRYAN MISSOURI UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ‘25We will keep you alive in us.

you wake up early one Sunday, and then you remember that you don’t have to go to Church.

at first, you relish this freedom— you sit in the sun and text your brother, who isn’t so fortunate, and you drink your tea slowly.

but later, when you call your brother and everyone else is in the car, and you are not, you realize that you might actually miss it, the ritual of Sunday morning:

forgetting to set an alarm the night before and waking up late, listening to music in your room so loud that your sister trudges upstairs to tell you she can hear Billie Joe Armstrong hollering through the ceiling, getting dressed last minute and leaving no time for tea or cereal or anything other than a breakfast bar you throw in your bag as you stumble through the door, trying to fasten the buckles on your heels as you go because in the background, Dad is yelling and in the bathroom, Mom is purposefully stalling (because you can’t).

sitting in the car as the tension in the front is drowned out with the gospel music that Dad always turns up too loud, so loud that Mom always reaches over and punches it off, as your younger sisters in the backseat tap away at cloudy, sticky iPad screens, humming along to the now quieter sound of voices congregating in a soulful choir.

sitting in the car, in the middle, with your temple to the window and your ears blocked with the pop-rock soundtrack of someone else’s teenage years, imagining yourself a real rebel— she leaves her father’s house at sixteen and lives in the woods and the grocery store isles and the mall parking lot, smoking despite her asthmatic lungs and

breathing, free of the expectation that binds your ribcage — and then imagining yourself pious, obedient in a white frock, hands folded and head bowed, as the highway landscape— the exposed red-brown-beige striations of sediment and the fluorescent blue of plastic tents poking through the blurred verdant foliage — rolls into and past your narrowing field of view.

sitting in the sanctuary, on a chair, but imagining yourself seated under vaulted ceiling on a pew, the perpetually cold wood from the old Methodist cathedral, years before the modern upgrades: comfort and plush, a carpet under your feet, a windowless, Nondenominational fortress that contains loud music and strobe lights, worship repackaged as a rave, dressed up in trendy concert attire and top-of-the-line equipment

(someone somewhere is watching the livestream of the service and sobbing to the performance, wishing to witness it in person, while you are sitting in the sanctuary just behind the tripod feeling nothing except annoyance when your dissociation ends, and you are reminded of where you are).

but you don’t really miss that, do you?

you don’t actually miss the pew, or the cold sanctuary, stuffed with robes and tradition and solemn prayers to a bored entity on the other side of the stained-glass.

you don’t miss the arguments on the drive or the belly-deep dread or the condemnation from the see-through plastic pulpit or the desperate attempts to preserve a dying faith via the language and look of your generation.

you don’t miss it. you just miss having something to do.

you miss being a child and getting snapped at for mouthing the gospels instead of singing them. you miss turning the pages in your King James Version Bible. you miss stretching and ripping your tights out of spite. you miss memorizing the Psalms.

you miss being old enough to appreciate the drive home, when Dad isn’t annoyed, and Mom is happy again, and the iPads are dead, and you are laughing so hard that you don’t even realize you forgot to put your music on.

you miss sitting with Mom on her bed and talking, complaining with her about the service, and about everything and everyone but the two of you.

you miss closing your bedroom door and swapping out Green Day for Paramore and performing the entirety of Brand New Eyes for your stuffed animals.

you miss lying on the carpet, staring up at the phantom glow stars glued to the stucco of your youth feeling at once five and twelve and seventeen.

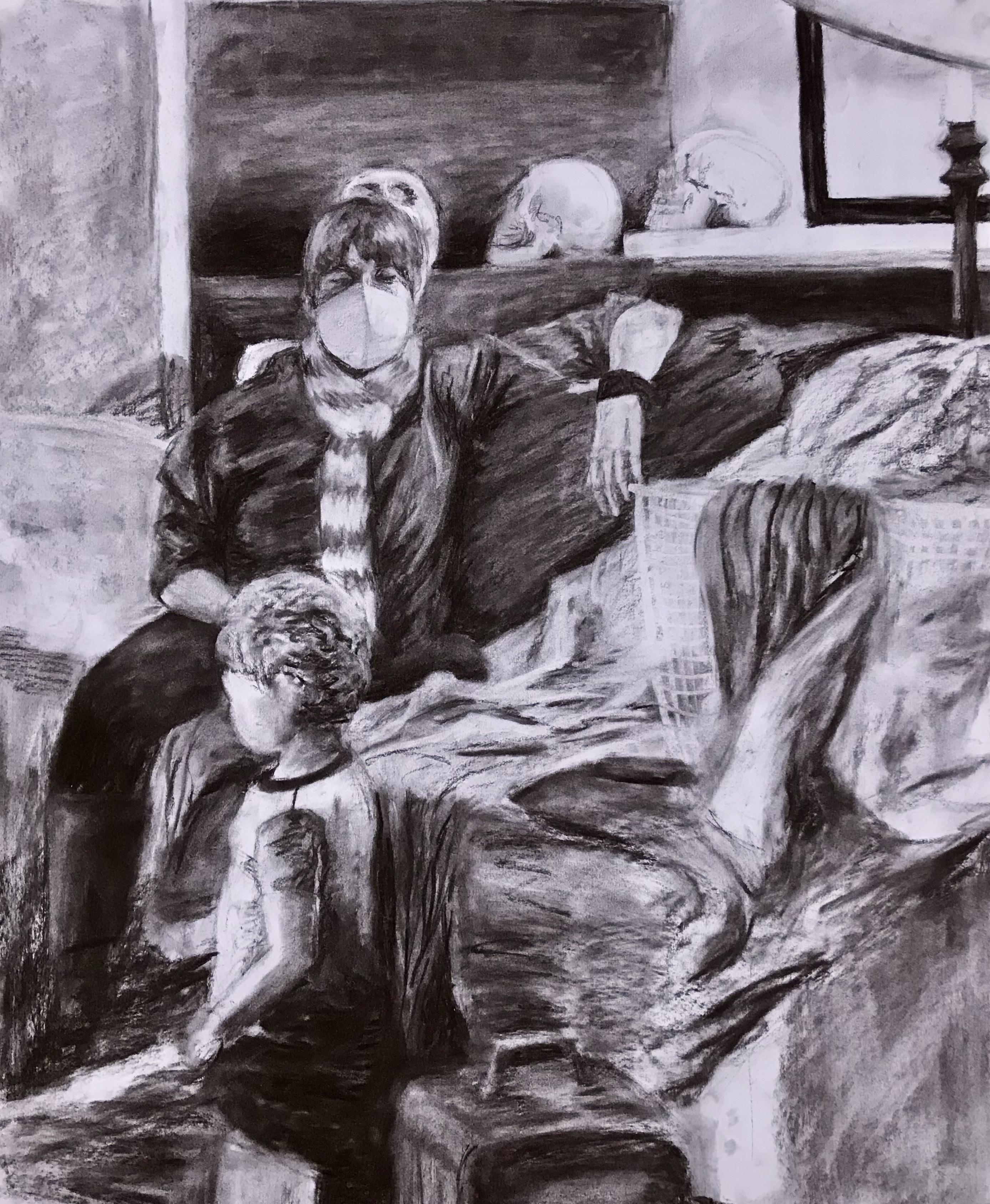

ISABELLA THOMPSON Professor GABRIELLE BUFFALOE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY ‘23 CHORCOAL ON PAPER

Professor GABRIELLE BUFFALOE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY ‘23 CHORCOAL ON PAPER

My neighbor has lived in the same apartment for 21 years. The whole time

he has owned the same furniture: the same faded table the same cracked chair the same corner mirror.

During his solitary dinner my neighbor can see his whole life before him laying in the yellowed image of a mirror stained with grease and snow.

I look at his mirror from my own apartment across the street. Its yellow image appears from the dark–like a lighthouse.

The new apartment next door is dark. In the black window, I catch a glimpse of my own yellow room. My face stained with grease and snow.

“Just as dogs don’t change character, men are dogs for one another.”

-Albert Camus, A Happy DeathADRIAN OTEIZA BROWN UNIVERSITY ‘24

KATELYN ALLEN UNIVERSITY OF DENVER ‘23 SCREEN PRINT

Ships named after women went farther. The captains knew it, the first mates took it to heart, the barkeep had a thorough understanding, the schoolteachers taught it in lessons, and the mayor hung it on a plaque in her office. Throughout the town, this was an undisputed doctrine: ships named after women went farther.

If you had a letter bound for loved ones off the coast, you put it in the mail sack set to ride the Adriana. You could bet your life on the warped and slippery bow of Cassiopeia, but no one with a shred of common sense would step foot on the sanded, stained, and sealed dock of The Starliner. Even the cobbler’s 8-year-old son had more business after he snitched a can of shoe polish and christened his rowboat Estella.

Tiin loved the ships, but she hated the town. Tiin was named after her mother, who was named after her mother, and so on and so back until the branches of the tree that gave the first Tiin her name stick a fig in your mouth and tell you to go home. The mother of the very first Tiin had buried her husband on one end of the country and carried her newborn daughter to the other. Her husband died before they’d decided on a name, and so, naturally, the child had to choose one herself. They walked and walked, her mother speaking flower names, blessings, and curses, but still her daughter looked ahead. Weeks, then months, passed like this until her mother plopped beneath a fig tree and pointed at the fruits, “Look, darling, tiin.” And Tiin laughed. To honor the tree that helped the first Tiin choose her name, her mother bought a house in the town below it where Tiin after Tiin was born. And there they stayed.

Named after so many women, it should not have been a surprise that the only thing Tiin longed for, the only thing she spoke of, was going far away. She told it to the ship captains and the first mates when they came in to dock. She repeated it to the barkeep every night as she mopped the floors. She announced it to her schoolteachers each morning, and, when the mayor awarded her with a distinction at graduation, she said, “Thank you, but I won’t be needing this when I leave.”

And Tiin told it to the ocean. Right at daybreak, when the water held neither sunlight nor starlight, and the first minnow hadn’t woken up, that is when Tiin leaned

forward, shut her eyes, and whispered, “I want to go far away.”

If you want nature to grant your wish, you must be the first thing that asks. To ask a tree, you must beat out the birds and squirrels. Generations of mothers bowed before the fig trees and made their prayers, each time rooting their daughters more firmly to the soil that stained their knees. The first Tiin owed the tree her name, so she could not leave. The second woke early one morning to ask the tree for true love. She met him at the fruit stall and he walked her home every day for 67 years. The third spoke a dream of music into the silence, and the bark gifted her with nimble fingers. Time after time, mothers and daughters knelt before the tree for beauty, guidance, or revenge, and so they could not leave.

The ocean is more powerful but far more difficult to ask. Unfortunately for Tiin, the ocean hears the sky, land, and sea, and every morning some bird or barnacle butted in before Tiin got a chance to speak. Tiin knew she couldn’t ask her mother’s beloved fig tree. The trees could never go farther than their roots; it had to be the ocean.

And that morning, Tiin asked first.

“I want to go far away.”

“Tell me why.”

She was tall, far taller than Tiin had expected. Kneeling before the Ocean, Tiin took in everything from the tips of her dark blue toes to the sea glass in her hair and the pearls around her ears. The Ocean spoke again, “Tell me why.”

“The world,” Tiin began, “I need to see it. I’ve outgrown the one I have.”

The Ocean gazed at Tiin for long enough that her knees began to ache. “If you come with me, you will never be allowed to return.”

Tiin stood, “I’d rather owe the water than the dirt.”

“It is not merely owing. There will be give and take.”

“Take me then.”

The town searched everywhere for Tiin. Well, they searched everywhere they knew. The mothers of mothers took Cassiopeia and Adriana and even paid a full day’s fare for the use of Estella. They

pulled back the tide and stripped the sea bed, but still, they could not find her.

People say she drowned. Others think she eloped. And some believe she was never really a girl to begin with. Only some of it is true.

Ships named after women went farther, but what they didn’t realize was that women named after mothers went farthest of all.

CHRISTIANA SINACOLA UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ‘24

umbrellas are for beating the ripe red berries off the April-sweet agarita bush until they leap and scatter across the waiting tarp, dotting it like the precious dropped periods of a sentence, rewritten we carried our spoils back to the cabin where with eager hands I sorted through the unwanted treasures—

three-pronged leaves little lost snails snippets of stems —until we were left with only the bitter berries, to be relinquished into just-boiling water where they popped louder than your hunting rifle calloused hands pass to me wooden stirring spoon your turn, you say gunshot or steaming pot— the liquid was red either way

1. i can eat one hundred dumplings for three weeks my mom kneads the dough like she is punishing the flour and cleaves one hundred balls of sitting ducks unsuspicious that she will come down on the dough like Demeter on the harvest to pluck a gold nugget-sized meatball one hundred times her hands cast an alien spell with meat and dough until a flower arrangement of flour is presented on a dish and copied until she wipes the sweat from her face drowsy from wrapping one hundred dumplings

2. one hundred dumplings crafted in the shape of tender ears are carried in a womb of steel and oil nine hours of one hundred frozen dumplings melting until only vague molds remain until we arrive in a city too over-kneaded to be eaten my mom gingerly separates the softened mounds with a mother’s instinct like she is mapping out the slope of her child’s nose and wrinkles in her miniature fingers to form one hundred dumplings once more

spent all summer dreaming of a London flat looking out of windows pretending to be a woman whose yellow wallpaper drives her mad wondering about this time next year will we have boyfriends & will they love us back? are our dreams so crazy or are others’ just that sad? because you can’t help but think that we should all want big things & I just hope that the grass is always this green because I thought this was only in the magazines I clipped in art class making portraits of a world that doesn’t ask if there’s a way to stop competing without being lazy

I wake on a summer morning, too tired to go on.

When I inform my father, he nods. I’ll get the car.

The sky is blue and painful like a swimming pool.

We drive to the ocean. Sandwiches, iced tea, then to the station for buffalo soft serve.

Ice cream is a good last meal, though my sister disagrees. But you are allowed to be right in these circumstances. I will admit there are things I am hesitant to leave behind:

My dog. My back porch, and the red hummingbird feeder.

The brown rocks at the bottom of the creek, the ones that look like small moons, and the crawfish that hide beneath.

Our voices in spring melting easily into the morning.

Chamomile tea, when in my blue porcelain mug.

Dewy glasses of lemonade that leave my hands dripping. Broth, lemon juice, and stunning green parsley. Evenings I remember with a screen of dust, the golden blurred grime of medieval paintings.

The river that runs through the forest like a tear, secret and true, the shadows of fish in the murky water.

Then the misery, and the freedom that comes despite it.

The little anarchies, like last night, leaving my light on until dawn like a child.