HONI SOIT

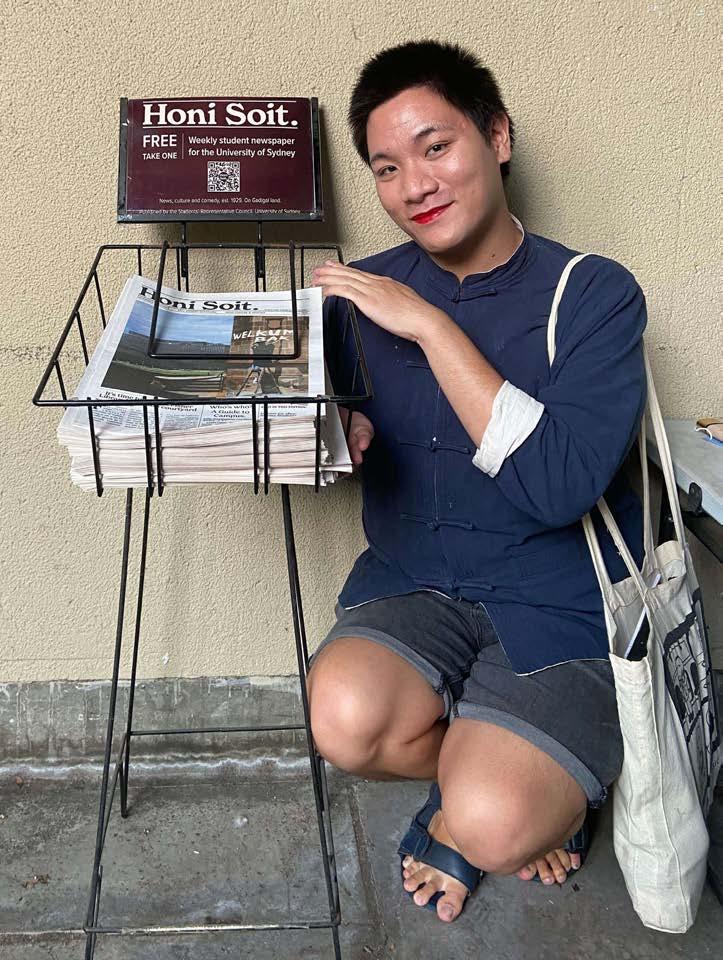

Vale Khanh Tran

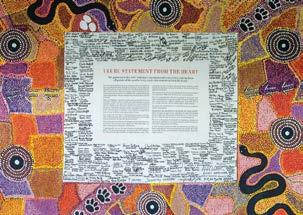

Acknowledgement of Country

Honi Soit operates and publishes on Gadigal land of the Eora nation. We work and produce this publication on stolen land where sovereignty was never ceded. The University of Sydney is a colonial institution. Honi Soit is a publication that prioritises the voices of those who challenge colonial rhetorics. We strive to continue its legacy as a radical left-wing newspaper providing students with a unique opportunity to express their diverse voices and counter the biases of mainstream media.

In This Edition...

Bumming Ciggies

Persian Rugs

Crip Walking

SRC Casework

History Bites

Messages from Friends

This edition is not a SPILL edition of Honi Soit, nor is it one of mine. This edition is Khanh Tran’s. To put it simply, I would not be an editor for Honi Soit without them. For me (and many others), they were a mentor, a friend, and someone who lit up every room they walked into. Sometimes, even before they reached the door, I’d smile because I could hear them coming with the clip-clop of their iconic sandals. They were incredibly intelligent and an investigation master. After frequently asking silly questions like “what is a GIPA”, Khanh never showed an ounce of judgement. Instead, they had a sense of patience and teaching that I’ve truly never seen from anyone else. Khanh embodied everything I wish to be in this life. They were exceptionally kind, generous, courageous, and consistently had other people at the forefront of their minds. They were a true inspiration for activism on campus and beyond. Their passing is a true loss for anyone who knew them, or knew of them.

With this, I’m proud to dedicate this edition of Honi Soit to them. They were staunch in their politics, which is fitting for the theme of this edition, ‘Burn it All Down’. This edition is a compilation of people who are angry at the government, societal norms, and at the narratives created by mass media. I hope you enjoy reading, and I urge you to take a moment to remember Khanh Tran, one of USyd’s brightest lights.

In love and memory,

Ellie Robertson

Sophie Bagster, Martha Barlow, Calista Burrowes, Samuel Garrett, Sidra Ghawani, Ramla Khalid, Luke Mesterovic, Ella McGrath, Haresh Palanirajah, Lilah Thurbon, Khanh Tran

Editors

Annabel Li, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Lotte Weber, William

To Khanh, from Charlotte

There aren’t enough words to describe the rarity of Khanh Tran, but as an Honi Soit editor, the very thing Khanh so passionately excelled at being, we will try.

Since I started at USyd two years ago, the iconic name, ‘Khanh Tran,’ has appeared in almost every Honi Soit, their investigative articles keeping Honi above the ranks of a measly student newspaper, and instead a reputable, fascinating source of journalism. Such is why I elected to be Khanh’s editor for the year, shooting my hand up as soon as their name was mentioned. I knew their work would be some of the most riveting pieces I’d ever get to read and to my luck, edit.

Khanh and I started texting a mere three weeks ago, and I’d say they were the most rewarding three weeks of my life. Khanh was and still is, the master of investigations. They were the strongest magnet, always the first to reel in every new piece of juicy goss. And while everything went to Khanh first, to their kindness, it then went to me.

Almost every day, I had the pleasure of receiving a message from them, informing me of the latest university scandal or offering a kind heads up about SMH offering free subscriptions for USyd students. I remember having an off day last week, but my spirits lifted after seeing a notification from Khanh excitedly telling me about an internship to apply for. I just remember thinking, how kind, to not only deem me as their editor, but a friend.

You will forever be missed. But we are comforted knowing that every time we step into the Honi office, your spirit warms the room, courses through our veins and guides us into continuing your legacy of damn authentic journalism. When we see a pigeon soar through the air, we’ll think of you, and whenever we open a newspaper we will remember you, for your legacy lives on in every heart you touched, every message you sent, and every article you wrote.

Khanh, I am at peace because I know that you have found eternal paradise with the Lord. In times like these, I remember Isaiah 41:10, ‘Do not fear, for I am with you; do not be dismayed, for I am your God. I will strengthen you.’ I pray for your family and closest friends, that Christ may give them strength.

They say that sometimes people pass young because God needs more angels in Heaven, and Khanh, I know your wings are shining the brightest.

Love from Charlotte, your editor. I miss your messages every day.

Khanh made our USyd community vibrant. They were incredibly dedicated, intelligent, and loved by all that crossed their path. It is an honour and a privilege to have known and worked with Khanh.

Khanh was woven into the social fabric of the university, of Honi Soit and the SRC, to the extent that their passing feels like something we took as a constant has been taken away. Just this week, Khanh had been working, with Charlotte Saker and Luke Mesterovic, on an article investigating the University’s investments into weapons companies. Their dedication to Honi, to mentorship and advocacy, knew no bounds. Khanh is someone who was so loved, so kind, and so important to so many — this is more than a loss. It is devastating to a community of students.

Purny Ahmed, Emilie Garcia-Dolnik, Mehnaaz Hossain, Annabel Li, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Lotte Weber, Will Winter

Rumour Has It...

Art by Ellie Robertson

Vale Khanh Tran.

Thank you and vale Khanh Tran, 1996–2025

Former Honi Soit editor and reporter, disability activist, USyd student, and our friend Khanh Tran died on 25 February, 2025. Khanh poured more into Honi than possibly any other person in the paper's 95-year history. From the date of their first byline in April 2020, to their last in March 2025, Khanh wrote more than 140 articles, a body of work that collectively set the agenda and purpose of this paper.

Khanh told stories with care and innate curiosity, allowing anyone who picked up Honi to be brought into the fold of campus life. Their interest in our university’s history was explored with characteristic morality, bringing forward previously untold truths and making campus accessible to everyone by archiving lesser known lore.

Without Khanh’s fight for a campus Disabilities Space — which started with a 2022 article and didn’t stop until they won — no such place would exist. Now, it is only apt that the space be named in their honour. This was arguably their greatest passion and most proud achievement.

"Khanh and Honi were lucky enough to find each other. And we are all so lucky that they did."

But there is so, so much for Khanh to be proud of.

We edited Honi with Khanh in 2022, after a particularly arduous election campaign during lockdown. During these months of campaigning, Khanh’s passion for a brave, inclusive student publication became clear. Honi had given them so much — a place to cultivate their interests, a community — and they wished to return the favour, to help set the tone of its history.

Khanh lived so many storied lives before landing in the Langford Office, down in a mouldy basement on City Road. It seems like some act of fate — and they were a dedicated person of faith — that after growing up in Vietnam, studying in Scotland, and eventually moving to Australia, Khanh and Honi were lucky enough to find each other. And we are all so lucky that they did.

Mama Bear is how Khanh described themself.

Uniquely calm and unwaveringly loyal, Khanh never struggled to be a dedicated and generous editor. They remained kind and patient with each of us, even though editing Honi inevitably puts pressure on the relationships between its editors.

We recall a heated argument about our ticket's colour scheme early on, in which Khanh appeared steadfastly neutral, only to reveal they were red-green colour blind. This characterised so many of our

Honi fights — Khanh: serene, unflappable and never a pugilist, there to remind us never to get too cynical and to focus on what matters.

Not once did they raise their voice with us. It was only years later that we heard tales of them ever shouting—at a UTS student councillor in Vietnamese, because “it was a more direct language”.

Khanh’s reliably warm and irreplaceable presence at each pitch meeting, layup, and drink at the pub will be sorely missed, even the time when everyone else ordered beer, and they ordered Frangelico.

Khanh was always in your corner, even when you weren’t.

They gave without ever asking for anything in return, whether it was shouldering more than their share of the workload, or gifts from overseas.

Khanh also worked harder than anyone we know. But when it came to Honi, it never seemed like work for them. Their relationship with Honi was reciprocal: it drove them and they drove it.

This drive was indispensable to our editorial team. Khanh’s willingness to write every news story and draw an abundance of art allowed the rest of us to pursue our passion projects and longform pieces — which, of course, Khanh somehow still found the time to do.

Most of us would stumble into the office late on a Sunday morning, fresh off the bender. Meanwhile Khanh would somehow always be there first, drinking a weak mocha with extra chocolate, laying up news to the Breath of the Wild soundtrack.

From the start of layup at 9am to the 5am finish line, when the rest of us were falling like dominoes, Khanh was still going. None of us could have edited without them. All we can hope is that they knew how we felt.

Khanh was generous in all respects, and that extended to their staunch activism at the University. Reflecting on their activism, we are struck by how rarely they focused on their own struggles, even though much of their politics was personal. They supported and championed solidarity, and believed so genuinely in celebrating difference in order to build a collective.

In their first editorial as editor-inchief, Khanh expressed this through their reverence and pride for their Vietnamese heritage:

“Wherever you are on your own adventure, storms will come by and attempt to force us to surrender. Strength, however, lies in numbers and complements the individual as a Vietnamese proverb goes:

Một cây làm chẳng nên non, ba cây chụm lại nên hòn núi cao.

One tree is but an infant but three make the highest mountain.”

Khanh’s connection to Vietnam was palpable, and something they shared generously. They frequently reminisced about their time writing for Saigoneer, and brought their encyclopedic knowledge and passion for Vietnamese food, scholarship, style and society to Honi.

Their boundless generosity manifested in many other ways, too. They were an ardent internationalist and felt strongly about justice for international students. This permeated their approach to Honi, from breaking news, to their feature articles, to the multilingual section.

Khanh could strike up a conversation with anyone. They instinctively befriended everyone from bartenders, to parents, to the chief adjudicators of the world debating championship, with whom they bonded over a shared affection for the Jesuits. They were never insular.

Their unmistakable signature style encapsulated this: full of colour and rarely weather-appropriate. They were vivid: lipstick perfect, nails painted (in the Honi office, probably), always looking straight into the camera even if you were trying to get a candid shot. When it comes to jorts, people say lesbians did it first. They’re wrong—it was Khanh.

But while they were so generous and outward-focused, Khanh also had a deep and often mysterious inner life, uniquely enigmatic in what they let on about themselves. For months we knew more about their encyclopedic knowledge of the Mecca catalogue than of their life preHoni, and by God did they have stories to tell.

Khanh was also a spiritually rich person. Having spent time as a Catholic seminarian and as a theology student at Heythrop College and Aberdeen, they had accumulated a mental trove of theology and a profound sense of faith. They wrote movingly on the complexities of queer religious life and the varied ways Christianity is interpreted around the world. They believed strongly in the value of learning and thinking about faith. In their first editorial, Khanh quoted from a poem written by Soeur Mai Thanh during her novitiate: “Release the kite and bend the endless wind”. They added: “As a Christian, I also rely on my faith to help bend that endless wind.”

For Khanh, activism and journalism went hand in hand. They were an allrounder when it came to the causes

Cake for Honi (Carmeli Argana, Christian Holman, Amelia Koen, Roisin Murphy, Sam Randle, Fabian Robertson, Thomas Sargeant, Ellie Stephenson and Zara Zadro) remember their friend and fellow 2022 Honi Soit editor, Khanh.

they jumped head first into; increasing accessibility for disabled students on campus, ending exploitative private student accommodation, and increasing support for international students throughout Covid. They marched for the protection of queer and transgender rights, picketed alongside university staff during negotiations for better work conditions, and supported the encampment in protest of the University’s ties to Israel.

Honi Soit was Khanh’s greatest weapon. Their many investigations into managerial wrongdoing, and the groundbreaking articles that came out of their digging, are testament to that. And it was during their term as an editor that they appreciated firsthand the power of investigative reporting.

Among all the causes they fought for, the Disabilities Room is perhaps their proudest achievement. On 24 April, 2022, they published an article that detailed the years-long battle for a disabilityfriendly space on campus. It exposed the bureaucratic failures that had led to USyd being the last of the Group of Eight universities to implement a fit-forpurpose disabilities space. What started as a simple question and a few conversations with fellow activists became the spark to reignite a long-stalled campaign.

At the next SRC meeting in May, councillors voted unanimously in favour of a motion calling for a disabilities space.

When the USU Board and its portfolio holders changed hands in July, their article became a pivotal resource for early development of USU’s Disability Inclusion Action Plan (DIAP). In following meetings with USyd’s own DIAP Steering Committee, student representatives consistently pointed to Khanh’s article as a way to pressure the University to act immediately. With all eyes on the campaign, the University finally approved a $50,000 funding application for the implementation of a disabilities space that had been sitting on the backburner for a year.

Today, the Disabilities Community Room sits in Manning in its full glory. It has a dual structure, with a quiet zone designed to accommodate students with sensory needs, as well as a larger zone for socialising. From the weighted blankets on the lounge to the tea station on the counter, every corner of the room carries Khanh’s touch.

Outside of disability activism, Khanh was relentless in their critique of tertiary education, usually with an eye on standing up for marginalised communities. Khanh, for example, was an ever present voice for oft-neglected international students, a champion of causes aimed at improving their everyday lives. Among other things, Khanh wrote on the decreasing affordability of student housing, international student working conditions, and the campaign

for international student concession Opal cards.

Most recently, Khanh spearheaded an exposé of ANU’s investments in companies listed by the United Nations as operating in illegally occupied Palestinian territories. Khan published these findings in Honi at the height of pro-Palestine encampments taking place on university campuses internationally, providing additional fuel to protests occurring in Australia.

"Khanh, we’re so grateful we could find a home in you. We hope you found a home in us, a place to be your authentic self."

Yet Khanh’s Honi legacy far eclipses what is mentioned here – it is memorialised in the hundreds of articles and artworks dotted through Honi over the last four years. One only has to trawl through the website and print editions to get a glimpse of Khanh’s contributions.

In one of Khanh’s earliest Honi pieces, a dedication to an old friend of theirs, they wrote:

“As overstated this may be, hope does exist. No matter how arduous the circumstances, reach out, speak to someone, a trusted friend. Get involved in queer circles and find a home in your community.”

Khanh, we’re so grateful we could find a home in you. We hope you found a home in us, a place to be your authentic self.

Coming together in the Langford Office to write this obituary, where Khanh spent more time than any of us, holds such weight. As time passes after editing Honi, the feeling of gratitude for the experience only grows and, selfishly, it has been an immense privilege to work together one final time in the place that meant so much to us, most of all Khanh. During the year we edited, there wasn’t a single occasion when one of us would come down and not find Khanh typing away. This time they aren’t here.

Editing Honi, things seem to become habitually quantified in 10s. There are 10 editors, 10 seats to book for dinner, 10 people to share a file with, 10 tickets to buy for Heaps Gay, 10 names to list off to make sure you’re not forgetting anyone. Often you get stuck on nine and wonder who you’ve missed, before realising you haven’t counted yourself.

Now we will only have nine seats to book for. But we will always count to 10.

Australian universities adopt contentious IHRA definition of antisemitism

Ella McGrath reports

On February 25th, Australia’s 39 public universities agreed to unilaterally endorse a contentious new definition of antisemitism.

The definition was drafted by leaders of Australia’s largest universities, the Group of Eight (Go8), in consultation with the federal antisemitism envoy, Jillian Segal. Universities Australia (UA) convened on Monday and agreed to implement the definition nationwide.

This comes after a series of recommendations from the parliamentary Inquiry into Antisemitism at Australian Universities were released last month, among them the need to adopt a “clear definition” of antisemitism that “closely aligns” with the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition.

Since its inception in 2005, the IHRA definition has faced global backlash from academics and activists for problematising criticism of Israel.

Public furore over the IHRA definition has prompted the creation of alternate definitions such as the Jerusalem Declaration, which draws a clear distinction between antisemitism and legitimate criticism of Israel and the crimes against humanity that the state has perpetrated against Palestinians.

Pursuant to the IHRA definition, the new UA definition states that “criticism of Israel can be antisemitic when it is

Interview

grounded in harmful tropes, stereotypes or assumptions and when it calls for the elimination of the State of Israel or all Jews or when it holds Jewish individuals or communities responsible for Israel’s actions.”

“All peoples, including Jews, have the right to selfdetermination. For most, but not all Jewish Australians, Zionism is a core part of their Jewish identity, substituting the word ‘Zionist’ for ‘Jew’ does not eliminate the possibility of speech being antisemitic.”

In a press release, the Australia Palestine Advocacy Network (APAN) slammed the definition as ”McCarthyist.”

“This move manipulates genuine concern about antisemitism to silence political dissent, shield Israel from accountability and shut down Palestinians and their allies.”

The Executive Council of Australian Jewry (ECAJ), a leading Jewish advocacy group, has not yet commented on the UA definition, but endorsed the Inquiry’s recommendation to draw from the IHRA definition.

However, the Jewish Council of Australia (JCA), a newer representative body that

formed in early 2024 for a more pluralistic representation of the Australian Jewish community, has called the definition “dangerous, politicised and unworkable.”

Dr Naama Blatman, a Jewish-Israeli academic who researches and lectures in settler-colonialism in Israel and Palestine, said that the definition “could very well be weaponised to silence the work of academics in this area, including my own.”

Mohamed Duar, a spokesperson for Amnesty International Australia said in a statement released on Thursday, “by adopting this definition, universities will be characterising peaceful protest as a punishable offense. This sets a chilling precedent where students exercising their political rights are vilified and silenced.”

“If universities are truly committed to combating racism, they must adopt a comprehensive, rights-based approach, one that protects all students without eroding fundamental freedoms and rights.”

Universities across the globe have seen a suppression in Palestine activism swiftly after adopting the IHRA definition of antisemitism.

After taking up the IHRA definition in 2021 against the backdrop of the Sheikh Jarrah crisis in Palestinian East Jerusalem, universities across the UK saw the banning of fundraisers and events related to the Palestinian cause.

Following President Donald Trump’s executive order against antisemitism to enforce the IHRA definition in 2019, American universities were subjected to legal action related to student actions supporting Palestinian human rights. At the time, the definition was rejected by one of its authors after observing the “chilling effect” of its application on campus.”

The University of Melbourne was the first tertiary institution in Australia to publicly adopt the controversial definition in 2023. Macquarie University and the University of Wollongong had already quietly adopted the definition in 2021.

Conversing with the Courteeners

Ellie Robertson cavorts with the Courteeners.

Courteeners are an indie-rock band from the United Kingdom (UK). They have smashed records in the UK with their debut album St. Jude becoming the album with the longest gap between its release and becoming number one on the UK charts; it went to number 4 in 2008 (the year of release), and to number 1 in 2023 (its 15th anniversary). The band are doing their debut tour in Australia in March 2025. Here, Ellie Robertson (ER) talks to the lead singer of the Courteeners Liam Fray (LF) about music through the generations, starting out small, and perspectives on writing.

ER: Hey, thank you so much for having me [yadda yadda]. You guys have been around since 2006, with your first album being released in 2008. I was born in 2003, grew up in Scotland, and the Courteeners were a staple of mine and all my friends’ playlists throughout our teenage years straight

through into our twenties now. I think that’s just incredible. Did you ever think, in the early days of releasing music, that you would become such an integral part of the UK indie-rock culture? And through generations too?

LF: No, not at all, you know. Not at all. It’s so nice that you say that. Scotland has such a massive part of our story, very early gigs we’ve done at ABC, King Talks, the Barrowlands [famous Scottish pubs]. We were really welcomed with open arms by Scotland, so they made it easy for us to play.

In terms of being part of it, I think because I was such a fan of bands growing up. It was like people mentioned all the Manchester stuff, but I was a fan of the Americas, Interpols, Years and Years, and Walkland. Obviously the Strokes and the White Stripes, and I’d be reading NME. I

worked at a shop on Wednesday with my mark because that’s when it came out and I’d buy the magazine. I’d devour it from cover to cover. I thought we might release a couple of singles, so when we got up with a deal and an album, we just had never thought about it. It was as if each next thing came, there was no grand plan.

We were all just friends from school and from a really young age. It’s never like, you know, we didn’t go to music college and we didn’t have any grand plans. It was just like getting in my garage and seeing what happened. It was the most stereotypical, organic friends in a garage you can imagine. So to be here nearly twenty years later is, well… it’s a bit of a miracle, and it’s also a bit of a blessing.

ER: It’s a crazy story, honestly. I was looking into the story of the band, and being friends since ten years old is a crazy

long time to stay friends.

LF: Michael, the drummer, his family lived next to some of my family, so we’ve been friends in school since four or five [years old]. It’s a long time. And you go with each other like family. The band is almost secondary to our friendship. The songs are really important to us, but if the band was off tomorrow, we’d still be hanging around. Not that it will, but you know.

ER: If we’re talking a bit about your love of bands and everything as well, I kind of see UK indie-rock as a very distinct style of indie. It’s very different and identifiable as quite separate to the style of indie in Australia or the US. How did it feel to realise that you were able to reach such a broad audience overseas as well, whilst having that niche? Did you ever see this becoming a reality?

University of Sydney announces amendments to the Campus Access Policy

Mehnaaz Hossain

reports.

The University of Sydney has announced amendments to the Campus Access Policy 2024 (CAP).

In an email to staff and students on the 27th of February, Provost and Deputy Vice-Chancellor Annamarie Jagose outlined amendments made in response to 111 community feedback submissions received in October 2024. Jagose noted a “reduction in the complaints and expressions of unease that had marked the previous semester” after the implementation of the CAP.

Jagose flagged multiple amendments in her email, including the removal of the 72-hour notice requirement for demonstrations.

Organisers are still required to notify the University of a demonstration “no later than when first communicated to people other than organisers”.

The ban on outdoor megaphones has also been lifted, with the amendment allowing them for “crowd management” but not to “harass or harm others”.

The CAP still maintains the ban on megaphones indoors and the rule that “any stall, booth or similar structure will require a space booking so that we can avoid clashing claims to the same space.”

In 2024, during the Gaza Solidarity Encampment, the University wielded the Inclosed Lands Protection Act 1901 (NSW) against protestors to revoke “permission… to be on our lands”. Following the amendments, individuals may now request a review from the VicePrincipal of Operations.

In the CAP document itself, further amendments can be found. Section 2.4, titled ‘Unacceptable Activities’, explicitly outlines an “exception for weapons permitted by law”.

This is in conjunction with Section 2.7(4) (b), which allows campus Protective Services to “require any user to provide… photographic identification” if they do not have staff or student identification. Previously, Protective Services requested only “name and address”.

by Anthony-James Kanaan

USyd establishes new scholarship in honour of 1965 Freedom Ride

Emilie Garcia-Dolnik and Imogen Sabey report

On the 26th of February, the University of Sydney (USyd) announced a new scholarship commemorating the 60th anniversary of the historic Freedom Ride.

The Freedom Ride was a protest, led by USyd student Charles Perkins, to fight for equal rights and opportunities for First Nations students. The Freedom Riders travelled regional NSW whilst documenting the segregation, inequalities, and injustices present in the communities they visited. The scholarship formally commemorates the 60th anniversary of the return of the bus to the USyd Camperdown campus.

A commemoration event was held on the 26th of February with the original Freedom Riders present.

The event included a panel with Jim Spigelman, Gary Williams, Professor Ann Curthoys, and Brian Aarons, chaired by Mark Scott. The panel discussed how the legacy of the Freedom Riders lives on.

Interim Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Services and Strategy) Professor Jennifer Barrett commented that “This scholarship is about more than financial support — it is recognition of the courage and impact of the original Freedom

Riders. It is also about empowering those who might follow in their footsteps.”

The Freedom Ride 60th Anniversary Scholarship for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students will provide $8,500 each year to two undergraduate students for the duration of their degree.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students from New South Wales who are experiencing financial hardship are eligible to apply for the scholarship, which will be awarded based on academic merit. A personal statement describing the applicant’s financial position and how the award will support their studies is required to apply for the scholarship.

The scholarship will be awarded by a selection committee, with at least half of its members identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Eligible students can apply from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander scholarships page on the university website.

LF: Again, no, not at all. And I take real joy in that we only very, very recently — on this record, really — have been on the radio. We’ve been on [the radio], but not mainstream radio, we’ve had a bit of backing here and there, but compared to some of our peers, we weren’t backed as much as they were. We’ve done well in the UK, but overseas, if we did 200 tickets in Munich, I’d have been like “200 people have seen us in Munich? That’s amazing.” It’s never been like “we need to be doing arenas” or “we should be doing these big outdoor shows.”

There was never any of that. That’s the dream, isn’t it? Pack your bag, get on a plane, go and hang out with some other people, see some of the world. When I say that’s the dream, I mean that’s the dream of a ten year old boy, not necessarily someone who’s in a band, because you still don’t think it’s going to happen.

You’re in the band, and you play, and you’re not thinking, “we’ll go to Australia next year. We’ll go to America next year.”

I write quite everyday stuff, but I suppose also, by turn, that means it kind of appeals to everybody as well. It’s quite lucky for me because, I wouldn’t say it’s selfish, but I don’t have to think too hard about writing because… it’s just me, I guess.

I think people really identify with that as well. That’s the kind of book that I like reading, [books by] lyricists like Shannon Bonett and Laura Marling. They were able to write about themselves, but it takes you somewhere else.

ER: I guess that also feeds into that intergenerational thing as well, especially growing up in the UK. The culture is the same as my Mum and Dad’s, like it stays that way throughout the ages. I think, particularly where I was from, we have a similar culture to Manchester as well.

LF: There’s so much in music where you’re passing it down as well. Whether it be your parents listening to it, or my older sister, like she would pass me her CDs and records, and that’s a real connector. Some

people have it in sport, where your old man will take you to the football or whatever.

For me, it was always music. My mum would give me Motown records and Beatles records. I’ve got nieces and nephews now that I might get to listen to The Strokes or the DMA’s. But I’ll be passing on the stuff that I’m into.

That’s a real love thing. If I love someone like that to share it, that’s what it’s about. It’s sharing the memories.

Art

Photo Credit: USyd

The Season of the Bitch Notes on Beauty in Extremity & The Shape Shifting Woman

Sophie Bagster confesses she’s a witch.

There’s this Frank Sinatra song called Witchcraft. Have you heard it? It’s one of the 4,999 songs saved on my Spotify: a seemingly never-ending digital chasm of sonnets and soliloquies. A sly tune. A real New York mythology. Perhaps then, it was by luck, or sheer coincidence that it came on shuffle this morning on the bus. A black-and-white filmic commute: thirty-five(ish) strangers and myself witnessed a ritual of sorts. An incantation on the 422. Between the bodies of the standing passengers sat a woman with rollers in her hair, squinting into a compact mirror, applying thick black liner to her waterline. She was dressed for a meeting. It was what Pagila refers to when she says that femaleness is a sequence of circular returns beginning and ending at the same point, “....[a] woman’s centrality gives her a stability of identity. She does not have to become but only to be.” Some form of habitual presentation of the self: the shifting of one’s shape. A domesticated witch: a tedious practice, a liminal ritual for passengers of all ages to gawk at.

People watched. I watched. Not once did the woman look about herself, only touching her lips with a liner the shade of blood. Men, both young and old observed, as if the carefully learnt practice of makeup was a private affair they should not be seeing. The ‘getting ready’ as an intimate pastiche: to look beautiful perhaps only dulled by the act of watching it happen. The magician with no secrets. The ‘morning ritual’ sublimely amalgamated with the terror of the morning commute, a private-turned-public appendage. I was a woman on the 422 watching men watch a woman. Sinatra whispered in one ear “... it’s witchcraft, wicked witchcraft!” whilst Pagila cooed in the other “...[her] centrality is a great obstacle to man, whose quest for identity she blocks.”

Whose quest for identity she blocks. It’s witchcraft.

I thought of Roald Dahl’s Witches: the beautiful womanturned-hag. I thought of spineless (digital) sexism à la One Wipe And It’s All Over, and, Take Her Swimming On The First Date. We are both expected to be and praised as shapeshifters, and yet it is the idea of the shapeshifting that causes agitation and faux desire for the natural. The foreign body in the blow-up doll. The witch.

bulk-bought ‘witchy’ T-shirts [polyester]. She is a printed travel coffee mug that says “We Are The Granddaughters Of The Witches You Couldn’t Burn.” She is mass-produced pop-culture tarot cards and “love spells” bought on Etsy. She is Whimsygoth, and she is spending her hard earned cash on Amazon carts of moon and star iconography. She is me, at fifteen, putting hexes on crushes who didn’t like me back. ‘Please make his hair fall out. Also, I would really like it if he texted me back’.

The “Modern Witch” is the neurosis of manifestation with perhaps a very real, almost childlike need to be different.

Individual. Powerful, brimming with mystique. A subtle cringe. The idea of reclamation is only weakened by commodification. “Witchcraft”, in this sense, is something one must purchase in order to be. We do not fear the witch because a lot of us identify with her through this consumerist narrative. We do not fear the witch because we have cut her down into bite-sized twenty second videos.

But she does still exist, between the synapses of beauty and fear.

The law of conversion energy is a natural law many understand. Energy, as it exists, cannot be created or destroyed, but transferred, changed, willed into one form or another. If energy can only be transferred, not destroyed, and fear is what breeds hate according to Averröes, then it can be argued that we never truly stopped fearing the witch. I will argue that this fear, rather, ruminates between women and disguises itself as hatred. Transferred energy, from one extreme into the other. What is unknown about women is at first feared, and then hated.

When ‘bitch’ won’t suffice to belittle a woman, ‘witch’ adds a supernatural element of which there can be no common male equivalent.

The witch is a saturated image, in lieu of Sollee. She is tangible history, myth and semiotics. She is both wicked and desired. She is maimed, romanticised and feared. Her history, as Federici puts it, is “primarily a history of women.”

Thanks to the incessant popularity of attention-span-shortening apps the witch is perhaps no longer a figure to be feared, but a symbol of commodity, sucked up into the maelstrom of fast-fashion aestheticism. She is Witch-Tok. She is Temu

Wolf, back in the 1990s revolutionised us with the words we had on the tip of our tongues but couldn’t spell out for ourselves: “...[women] are taught to see other women as competition, based on physical and sexual appeal.” Was it not Abigail who was bound to obsess over the destruction of her female counterparts? The “witch” of a woman who is hated is most commonly the woman with power. And, the more power a woman has, the more hated she is for having that power. The thing with power and beauty is that they are often running in opposition to one another: one may find that as she gains power, the standard for a ‘successful woman’s’ beauty has changed right before her eyes. Stories of PhD graduates receiving breast implants as rewards for their studies and air hostesses losing their jobs due to age and physical appearance are two of a macrocosm. When the witch is feared, she is accused and killed. When the “Modern” witch is feared, she is stamped out by something more impervious: a shallow death, a daydream of a death.

It goes a little something like this:

It begins with a trial. A conversation, if you’d like. An allegation usually brought forth by elusive evidence only. No need for palpable conviction. Not all accusations will be believed, and yet a large majority will go under anyway. This is followed by a thorough poking and prodding of the body to look for ‘evidence’. Are there any moles? Is this a normal, healthy body? Is the skin firm with good elasticity? How does the woman react to this scrutiny? It was usually here when the confession slipped out, a colloquial but maddening ‘I am guilty, sinful, deranged and evil’. And then? By majority agreement, the body comes under the torture, the horror, the immaculate-near-death of unconsciousness: a heaven-sent slumber. Finally, the pain will end. At last, one can rejoice in the freedom of being born again: pummeled a million times by unseen instruments at the hands of the men who made us. No special training is required for this execution, it can be performed by any registered practitioner.

This is not a burning at the stake, but the domestic and process for undergoing liposuction. Or breast-enhancement. Or, really, most kinds of cosmetically elected surgeries. This is not a self-infliction accusation either, but one that is learned from hatred. To be beautiful is to suffer and to have power is to be a witch, and the only suffering that “stamps out” the witch is a rebirth into the ground, from which a new woman emerges. Nobody wants to look like, or be a “witch” in this sense, in the same way that in the 1960s nobody wanted to be a “feminist”—considering the visual stereotype of a masculine and unfeminine woman. The market invents a witch… an overhanging image of the “hag,” an older, fatter and undesired woman who ‘Could Be You Too Unless You Do Something About It Now!’ There is lots of money to be made from the imaginary witch.

The modern day burning at the stake has more to do with choices and thoughts about the body than any other: it is those choices that cause agitation, hatred and something like confusion: it is exactly what the woman on the bus this morning was subject to. Everybody wants the girl until they see her skin shed.

We are living in not only a Surgical Age, but a time in which the choices about our bodies are in the hands of others. This runs deeper than the cultural, unspoken push for a beauty that is surgically constructed to stamp out the flaws - the witches mole - it runs right into the original waters of all men and women, Pagila’s “umbilical which leashes [us all].” Here, perhaps the fear and hatred boil down into another: control emerging from the broth. The ability to accuse women - or anybody else - in order to benefit a political campaign, personal and social status is a witch hunt. It is about control. Control that masks fear and hatred and love. Federici says “the body is a battlefield where social relations are inscribed,” that the persecution of the witch is nothing but a reflection of deep-rooted misogyny and fear of women’s autonomy. Our autonomy is our power. Both cosmetic surgery and laws against our bodies seek to dissolve this autonomy: conceal its unbridled joy in a doggy shock-collar.

Why would we want to be witches when our only two options seem to be a celebrated commodity or a hated power?

Because, despite all of this noise: the witch is still a shapeshifter. She is nonconforming woman in her power, unbound by digitalism and the Iron Maiden. She is both moon and menses: an etymology of measurement, the month by which we count a cyclic rebirth. She is sitting with rollers in her hair on the 422. She is my mother; emerging from her closet a candle-lit, comfy witch free from her work heels and email inbox. She is the shared moles between my sister and I. She is the microcosm that mirrors the macrocosm. She is my friend, syncing her bleeding with mine. She is hidden in books and celluloid stories and grocery

stores. She checks her mailbox. She waters her plants. She, at once, is a magical woman.

When I told my first big-girl boyfriend I was a witch, he asked “why?”

I thought about it. There was a lot I could say. Maybe that I had grown up with it? Raised by a woman who taught me feminine strength. A small town with witchy bazaars and an ennui almost as dry as the drought that it made you sit for hours in the only bookstore reading the horoscope compatibilities between you and the crushes you had at age of fourteen. Because I had gone through puberty with girls who believed in the radical possibilities of the hex and the intricate collecting of crystals; lining them up on the window sill and placing them in your bra (when you are old enough to fill it out). I had experienced a myriad of incredibly intense female friendships bound together by twine and sage, promise and hatred. Diary entries that started with “there is magic….I know it.”

“Why are you a witch?”

“Because I believe in feminine magic.”

There’s an excellent scene in Bell, Book and Candle (1958) where a small coven of NYC-dwelling witches take refuge in an underground bar. One of them says “...I sit in the subway sometimes. On buses, or the movies, and I look at the people next to me and I think ...What would you say if I told you I was a witch?”

Art by Ellie Robertson

Burning the bookstores, igniting the story: Why oppressors fear words more than weapons

They came for the books as though they were weapons. Stormed the bookstores as though they were arms factories. Confiscated the pages as though the ink on paper could be detonated.

But that is the mistake every occupier makes.

Stories do not die when you burn them. They slip through the cracks, hide between margins, and smuggle themselves across borders. They whisper their way into history, into memory, into the hands of the next generation.

When Israeli forces raided Palestinian bookstores in Jerusalem earlier this month, tearing books from shelves and arresting their owners, they were not just targeting words. They were trying to erase a people. To erase a people, you do not need to bomb their homes or massacre their families. You need only erase their stories.

Colonial powers have always understood this.

The Spanish burned Indigenous codices to erase the history of the Americas before rewriting it in their own language. The British criminalised Irish literature in an attempt to sever a nation from its own voice. The Nazis piled books into flames, terrified that ideas could dismantle their regime. Now, in 2025, Israel raids Palestinian bookstores in Jerusalem, confiscating literature as though a poem is more dangerous than a gun.

To them, it is.

I know this war intimately.

I carry a Palestinian hawiyah, an ID card that Israel would rather not exist. A document that is, in itself, an act of defiance. In claiming this little piece of paper that Baba got me when I was younger, we chose to recognise our Palestinianness, despite people’s efforts to talk us out of it. A simple document trumped my Australian identity. From that very day, I could no longer travel to the other parts of Palestine; to my own home. A single bureaucratic decision turned me into an exile.

Isn’t that what this has always been about?

Erasing the proof. The maps. The names. The land deeds. The archives. The books.

What happens when a nation’s history is confiscated from the shelves? When their poetry is no longer printed? When their literature disappears? If the story is not written, does the world assume it never happened?

This is how they burn it all down—not just by setting books on fire, but by arresting those who bring us the truth, by rewriting history to cast themselves as the victim, by fabricating a story that absolves them of their crimes.

Bassem Khandakji knows this better than anyone. He, too, was meant to be erased. A Palestinian writer, who is locked away in an Israeli colonial settler prison, stripped of his freedom, buried behind walls designed to suffocate voices like his. But they still failed.

From his cell, he wrote a novel, A Mask the Colour of the Sky. A book so powerful it escaped his prison before he did. It won the 2024 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, an honour that should have meant a triumphant book launch, a literary tour, a moment of celebration. Instead, he remained in his cell. Another nameless prisoner to the world. Another body behind bars.

This is how they try to control the narrative. They arrest the authors and rewrite their endings.

What they do not understand is that stories are not confined by borders, by prison walls, or by military occupation. They slip through cracks. They cross checkpoints. They outlive regimes.

That is why they fear them.

If literature was not dangerous, why have all colonial empires sought to control it?

Why does Israel flood the world with propaganda films, fabricating its own mythologies, while banning Palestinian authors from publishing their works? Why do they erase Palestinian villages from maps, forcing an entire generation to learn geography through exile? Why do they criminalise books, poems, even simple phrases?

Because storytelling builds humanity, and humanity dismantles oppression.

Literature forces you to step into another’s shoes. To see through their eyes, to grieve their grief, to love what they love. That is why the best stories outlive their time periods. They become trans-temporal, resisting the confines of history because they are no longer bound to the moment they were written in.

As a child of the diaspora and a Palestinian writer, I have always yearned to make a difference. Growing up, I had little access to books about kids like me, Palestinians with my experiences. This absence fueled my desire to create a literary world that resonated with the stories of many.

Backtrack to Year 12, when I was deciding on the form of my English Extension 2 major work, I struggled. I wanted to write non-fiction: an essay dissecting the erasure of Palestinian identity, the distortion of history, the way maps had been rewritten to scrub us from existence. I wanted to fill the pages with facts, with evidence, with unshakable proof that could leave no room for doubt.

But something felt wrong. It wasn’t enough. Facts can be ignored. Statistics can be manipulated. Data can be dismissed.

But stories? Stories cling to people. They haunt them. They follow them home.

A character you cannot look away from. A life that, for just a moment, feels indistinguishable from your own.

That is what storytelling does: it forces you to step inside a world you would have otherwise never entered. It makes oppression personal. It gives the numbers names, the statistics faces, the history a heartbeat.

And so, instead of a thesis, I wrote a short story.

Jaseena Al Helo empowers storytelling.

A world where a Palestinian girl held onto the last remnants of her family through the books they left behind. A story about memory, about grief, about refusing to be erased. Because fiction is never just fiction: it is a testament, a reclamation, a form of resistance that lingers long after the last word is read.

That is why Israel fears our literature. It is never “just a book.” It is a link between past and present, homeland and exile, the living and the martyred.

And for Palestinians (especially those in the diaspora), stories are how we find each other.

We are scattered across continents, our land fragmented beneath checkpoints, our history deliberately distorted. But, when we read the same books, recite the same poems, tell the same stories, we stitch ourselves back together. My Tayta’s lullabies, my Baba’s stories of Jaffa, my own writing… they all belong to the same narrative. Our narrative is one that Israel has spent decades trying to erase.

When a Palestinian child in Chile picks up Men in the Sun, they are connected to a Palestinian elder in a Lebanese refugee camp who read it decades before them. When someone in Australia reads Returning to Haifa, they unknowingly continue the legacy of someone in Gaza who had to smuggle that same book across a border. When a reader in the United States immerses themselves in Samah Sabawi’s Cactus Pear For My Beloved, they are sharing in the resilience of a family from Gaza. When a European enthusiast delves into Sonia Nimr’s Wondrous Journeys in Strange Lands, they traverse the rich landscapes of Palestinian folklore and history. No matter how much land they take from us, they cannot take this.

They can rewrite the maps but not erase the stories that came before them.

They can desecrate the land, but they cannot undo the generations who built it.

They can ban the books, but they will never silence those who write them.

Storytelling is how we keep our Asl.

Our origins. Our roots. The thing they will never have.

As Mahmoud Darwish once wrote:

“Every beautiful poem is an act of resistance.”

Kullu qaseedatin jameelatin hiya fi’l muqawama.

If words were powerless, they would not be banned. If poetry did not threaten power, it would not be criminalised.

That is why they burn them.

That is why they will always fail.

I am a radical feminist and I am burning my bra

Lilah Thurbon’s bra is literally on fire right now, ouch!

One of the great tragedies of the modern feminist movement is that its members do not want to burn their bras. In fact, being a bra-burning, radical feminist is often used as a pejorative to describe women who approach their feminism with the militancy it rightly deserves but rarely receives.

This use of the phrase makes sense when you uncover the history (or lack thereof) of bra burning. The association of feminists with bra burning can against the Miss America Beauty Pageant in New Jersey. No bras were actually burned in these protests; rather, women threw lipsticks, high heels, and lingerie into a “freedom trash can” to protest the patriarchal and white supremacist beauty ideals promulgated by the pageant.

being of secondary importance to more ‘serious’ ideological questions of class, and are frequently detached from discussions of race. This leads to the further marginalisation of women of colour and dismissal of the intersectional nuances of patriarchal oppression. Individual men are frequently perpetrators of misogyny, from gendered exclusion and sexist behaviour to sexual violence. Many resist accountability, and from personal experience, women and gender minorities often leave left-wing spaces because of this.

But the question remains as to why. Surely, a political movement with politics grounded in compassion and a theoretical focus on collective liberation has an incentive to fight for the feminist cause, and male leftists an ideological reason to unlearn misogynistic behaviour?

I think the root of this problem lies in the current state of sexual politics, and that this explains the continued subordination of women across the traditional left-right political spectrum.

has lost its bite.

The wave of liberal feminism that characterised the 2010s was framed through the rhetoric of maximising choice. Its ultimate goal was giving women the required amount of political power to make the choices they thought best actualised their preferences. What women were actually choosing was largely beyond the scope of feminist criticism, which led to the mainstream acceptance of things like sex work, pornography, conforming to patriarchal beauty standards, and opting into being a house wife as valid “feminist” choices.

Choice feminism is still the version of feminism most subscribed to by the average left-leaning person, largely because it does not ask anything of its followers. So long as the patriarchy does not obstruct you from making choices, you’re empowered to live in any way you so choose.

requirement that they are sexually available to men; ripe for purchase in exchange for money, a marriage contract or some other guarantee of social security.

Feminist liberation requires women to challenge both the capitalist commodification of sex and the patriarchal dehumanisation of women as sex objects, both of which are contingent on women making themselves less sexually available to men.

The myth of burning bras reportedly comes from a comment made by a journalist covering the Miss America protest – “Men burn draft cards and what next? Will women burn bras?”

This connection with the Vietnam War protests goes deeper than the fiery symbolism. Many of the women who participated in the Miss America protests were not specifically feminist activists, but rather young radicals who came up through the anti-war and civil rights movements. One of the organisers, Robin Morgan, cited the failure of left-wing men to advocate for feminist issues as the catalyst for action on women’s liberation.

“We thought the male left were our brothers [but] discovered that was not really the case when we talked about our own rights.”

Nearly 60 years on from these protests, left-wing men still often fail to extend their solidarity to women. Feminist issues are often viewed as

When Kate Millett wrote Sexual Politics in 1970, she argued that heterosexual sex is one of many ways “outright force” is used to uphold patriarchy. Women are subordinated and men conditioned to be dominant by the patriarchal structures that shape the ways in which we engage with sex, and it was a failure of the sexual revolution that such structures were never meaningfully challenged. Millett’s observations are of great modern relevance. The relationship between sex and patriarchal oppression is most obvious on the right, where women are expected to be sexually available, and thus subservient, to men as wives and mothers. Especially with the rise of the far right and a potent wave of religious extremism, sexual and reproductive labour are increasingly viewed as the primary value of women in a conservative ideal of society. However, the way that sexual politics play out on the left is perhaps more interesting, and provides insight into why the modern feminist movement

The more politically engaged camp of leftists would probably reject the association of liberal feminism with the left. This is fair – things like beauty culture and homemaking are frequently criticised by the left for being oppressive, and liberal support of them unresponsive to the broader coercive structures that exist under capitalism. But this same criticism is often missing from leftwing discourse pertaining to sex.

Radical feminist criticisms of the sex industry, that it exploits and commodifies women’s bodies and reproduces patriarchal conditions of male domination, are frequently dismissed. Discourse is stifled as we’re labelled as ‘SWERFS’ (sex workerexclusionary radical feminists), or ill-fitting analogies drawn between the economic coercion of sex and any other economically coerced and intrinsically exploitative physical labour under capitalism. The same happens in conversations about pornography.

These responses erase not only the sharply gendered nature of the sex industry, but also the necessity of sex more generally in maintaining patriarchy as a hierarchy. Women are objectified by the patriarchal

Right-wing men react badly when women don’t want to have sex with them, infamously so. But, leftwing men are also not exempt from impeding feminist progress. They too are capable agents of the patriarchy in their relationships with women. The sexual politics that play out in the personal sphere in left-wing contexts are conveniently obscured. So long as women who threaten to disrupt the patriarchal status quo can be easily dismissed as ‘bra-burning, radical feminists’, the modern feminist movement is damned to repeat the failures of the sexual revolution.

Andrea Dworkin was as right as she was provocative when she said that “the left cannot have its whores and its politics too.” It’s time to stop placating men who purport to be our allies and defending the choices of women that are antithetical to feminist liberation. Feminists must add some real fuel (and brassieres) to the fire – the only path forward for real liberation and to resist the patriarchal violence of the far right is a radical one.

Share this article with a lady who could stand to shed her bra.

Art by Emilie Garcia-Dolnik

A Brief History of the Institute Building Termite War

Within the Institute Building’s gleaming, palatial exterior lies the carnage of a years-long war with a hidden enemy almost too small to be seen — termites. Over the better part of the last decade, University facilities staff and teams of pest exterminators battled with hordes of termites that caused devastating damage to the building’s southwestern wing. New documents and photos reveal the extent of termite damage to the now-closed southwestern wing of the building, and the secret story of the battle to hold the insects responsible.

In late 2018, pieces of ceiling plaster inside the Institute Building began falling to the floor. Spurred by the alarming decay in the building’s condition, a structural engineering inspection found water in the building’s walls, ceilings, and floors. But it was a look below the carpet that horrified the inspectors.

An enormous nest of termites was within the third and fourth floors of the building, home to an army that had burrowed through the hardwood floor joists and was eating its way through the heritage building. In a report, the inspector noted that based on the “severity of the damage... it seems to be the termite entrance gate into the building.”

Building occupants were left with only one option — a full-scale retreat. The inspector immediately recommended that access to the third and fourth floors be restricted due to the structural floor damage and ordered an extensive inspection of the entire building “to identify the extent of [the] termite invasion.”

A key vulnerability in the fortress that is the Institute Building is the abysmal state of its waterproofing. Water damage is a notorious feature of the building, and a key risk factor for termite invasion. The building’s heritage listing also hampers effective defensive measures, with repairs made more complex and expensive given that structural repairs must be concwealed beneath the building’s exterior.

By September 2019, a Rentokil battlefield inspection found live termites on the second, third and fourth floors of the southwestern wing, with “severe structural damage” and water damage around the termite mothership. For the first time, the inspectors unmasked the enemy they were fighting, naming the invaders as dreaded coptotermes termites.

Coptotermes is known as the most economically destructive genus of termites on the planet and is responsible for up to a billion dollars’ worth of damage around Australia each year. According to University of Sydney termite expert Maxim Adams, “coptotermes colonies typically establish in the bases of tree trunks or the subfloors of houses, then progressively tunnel through any wood they can find.”

Rentokil’s report noted “extensive fungal decay” from water seepage under the termite-ridden wing of the building and recommended improving the disastrous subfloor ventilation. Part of the reason the termite hordes had managed to overrun the building in such short order was the failure of the buildings “termite shields” — metal barriers designed to reduce termite movement — which the report found

to be inadequate and in urgent need of replacement.

A host of other issues compromised the building’s natural defences against incursion: downpipes were unconnected to drains and filled by overhanging trees, and the building’s concrete slab sat too low to the ground, allowing the sixlegged siege engines to roll right into the building’s foundations.

Together, these failings made the building a soft target at “very high” risk of future infestation. The building’s human defenders decided to get serious. Rentokil recommended installation of a chemical soil treated zone, termite monitoring systems, drilling of trees to inspect for colonies, repair of the termite shields, fixes to drainage and biannual termite inspections “to determine presence or otherwise of live concealed termite activity.”

Yet despite the recommendations, structural engineers from Taylor Thomson Whitting (TTW) consultancy wrote in a November 2022 dispatch that despite Rentokil’s call to arms three years earlier, no remedial action had been taken. Only temporary props had been installed to stop the third floor from collapsing, yet it still “deflect[ed] significantly when walked on.” Water damage had become severe, with an “extremely high” risk of further termite attacks.

TTW engineers recommended an inspection of the entire building by a termite specialist “to identify the extent of termite invasion especially to the structural timber joists… It is recommended to carry

out treatments to eradicate the termites and to protect the building.”

Thankfully, the end of 2022 finally brought with it the end of the termite colony. “There are no more termites,” declared waterproofing experts in a January 2023 building report. The University was left to pick up the pieces from half a decade of termite takeover, beginning with “the extreme stench of stale water and rotten wood” in the building’s roof. Inspections revealed that a woeful lack of rooftop waterproofing around the building’s stonework and gutters had caused water damage that assisted the ravenous termites for years.

To this day, most of the Institute Building’s derelict southwestern wing remains sealed. Termite inspectors slowly pace through the building every few months, tapping walls to check that termites have not returned to the scene of one of their greatest campus conquests. An uneasy peace has settled over City Road, but how long it will hold is anyone’s guess. And inside the building’s southwestern wing, dozens of rooms still lie empty in quiet disrepair, victims of the University’s hungriest residents.

The anatomy of the University of Sydney’s opaque $4.92 billion endowment

Charlotte, Khanh Tran and Luke Mesterovic unearth USyd’s controversial investments.

The University of Sydney continues to invest significantly in controversial sectors, including more than thirty fossil fuel and mining companies, gambling firms, and five arms manufacturers, a joint Honi and Education Action Group investigation has found.

Sydney University is Australia’s wealthiest university by a wide margin with an endowment worth $4.92 billion – a figure three times the size of rival Melbourne University. It is twice the endowment of all constituent universities, including specialist institutions, of the UK’s University of London combined.

This fund is separated into three pools: a long-term, medium-term and short-term pool.

These investments have generated enormous wealth for USyd, peaking in 2021 when its endowment surged by a record $990 million in 2021 and made a gain of $490 million in 2024. However, according to a University spokesperson, the University’s endowment includes funding from sources such as philanthropy, investments, and grants, which are subject to regulations and restrictions that prevent their use for general operating costs. In 2023, while the University’s total operating income was reported at $351.8 million, once these restricted funds were excluded, USyd experienced an underlying loss of $9.4 million.

Refusal to disclose full values of investments marks a dramatic turn from the past

In response to SRC Education Officer

Jasmine Al-Rawi’s freedom of information application, the University refused to disclose the monetary value of its investments, citing “commercially sensitive” data about contracted fund managers and companies.

Instead, the University only released data on each investment’s weighting in proportion to 30% of the portfolio, alongside heavily redacted reports from its Chief Investment Officer.

“Release of this information could place those companies at a competitive disadvantage and could damage the University’s reputation as a customer of financial and investment services,” The University’s freedom of information team said.

“The value of the investments is also confidential information. Disclosure of this information, which includes significant inputs to investment planning, deliberations and decision making, would reveal information that reflects confidential planning and analysis processes and university strategic thinking and was not intended to be made public.”

However, Honi can confirm that in

previous years, USyd disclosed full details on its investments held in private equity funds, including the financial value of investments held by external fund managers when previous editorial teams requested on multiple occasions across 2022 and early 2023.

When approached on this discrepancy, a University spokesperson said that while the Archives and Record Management Services Team that while USyd can release information “at a very high level”, it cannot do so “at more granular levels” as opposed to higher value figures, claiming that this would “breach the contract we have with fund managers”.

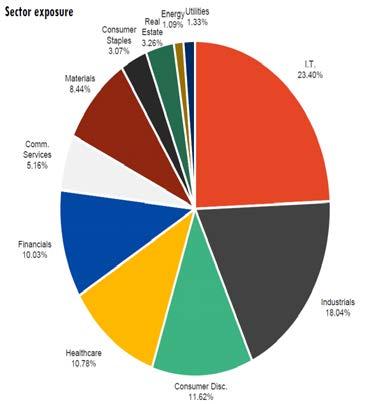

Breaking down USyd’s investments

As of 2024, the University of Sydney’s endowment covers a wide range of areas. The largest concentration (23.4%) of investment lies in technology, with a considerable number of shares in semiconductor manufacturers including Morris Chang’s Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) – one of the world’s biggest semiconductor producers.

According to USyd’s 2024 Investment Report, a major factor in last year’s $490 million windfall is an “unusual repeat of 20%-plus returns for the U.S stock market”. Internal data seen by Honi reveals that U.S investments (43%) constitutes the University’s largest overseas shares by a wide margin, ahead of domestic shares (23.5%).

Another significant area of investment is in fossil fuel, critical minerals and mining industries, comprising 35 companies or 10.8% of USyd’s portfolio. Major conglomerates spanning Rio Tinto, BHP, and Shell are all represented with BHP ranking consistently in the top five amongst USyd’s investments.

Please Note Cameco Corp, Newmont Corporation, Northern Star Resources Ltd, Firefly Metals Ltd, Atlantic Lithium Ltd, Evolution Mining Ltd and Pilbara Minerals Ltd are “invested in green and precious.”

Samuel Garrett investigates.

The University also holds a strong interest in gold and lithium mining with ties reaching mines across nearly all continents. Among its highest holdings is Western Australia-based Red Hill Minerals which mines gold, base metals and iron in the Pilbara regions. Through Perseus Mining, USyd also derives revenue from gold operations in Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire.

As reported by The Guardian’s Henry Belot last year, USyd continues to maintain investments in the gambling industry.

Other controversial names include UnitedHealthGroup and Kingspan. US-based UnitedHealthGroup is most famously known for its insurance business, which drew public attention to the company’s high health insurance denial rate following former CEO Brian Thompson’s death.

Kingspan, an Ireland-based major insulation producer, was sharply rebuked by the Grenfell Inquiry’s Final Report in September 2024 for creating a “false market” for cladding on tall buildings over 18 meters. The Report found that there was a “deeply entrenched and persistent dishonesty on the part of Kingspan in pursuit of commercial gain coupled with a complete disregard for fire safety”.

University of Sydney investment complicit in “flagrant violation” of international law in Gaza

Yet the most controversial of USyd’s investments rest in its shares in five international arms manufacturers: Airbus, Woodward, Safran SA, MTU Aero Engines and Allient Inc. However, according to the University Spokesperson, these companies ‘mainly produce engines for aircraft.’

Please note that The University “‘rejects any suggestion the University has been involved in the conflict in the Middle East through our investments or in any capacity.”

United States-based Woodward drew intense criticism in May 2024 when an analysis by Palestinian journalist Alam Sadeq corroborated by the New York Times confirmed that a GBU-39 fragment made by Woodward was dropped in Rafah (Gaza) by the Israel Defence Force (IDF).

The attack, which resulted in displaced Palestinians “burnt alive” in tent camps, attracted condemnation from across the world from Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, France, Spain, Germany and the United Nations (UN) Secretary General as a grave violation of international law.

Multiple UN Special Rapporteurs, including USyd’s own Professor Ben Saul, signed a joint press statement calling out Israel’s attack a “flagrant violation of international law” that defied the International Court of Justice’s

provisional order based on the Genocide Convention in the same month.

This confirms for the first time that a company that Sydney University invests in is directly involved in Israel’s war in Gaza. And by extension, evidence that USyd’s investment is complicit in war crimes.

It is important to note that according to a university spokesperson, USyd is no longer affiliated with Woodward.

The University “held stock in the company for about nine months through a mandate, meaning it was held as a direct position but managed by one of the international equities managers.”

‘The University purchased stock on February 10th, 2023 and sold it on June 28th, 2024, investing $1.62m, which was 0.054% of the University’s Long Term Portfolio at the time of investment,’ said the spokesperson.

“The exposure to this segment relates to very specific components and not the wholesale manufacture of weapons. There was no exposure to cluster munitions, which is the current University exclusion for the defence industry.

The great bulk of Woodward’s business is focused on energy conversion and control solutions for the aerospace and industrial equipment markets. Part of the investment manager’s sustainability thesis for the company related to enabling the transition to net zero through developments in energy efficiency technologies and driving innovation in aerodynamic efficiency.

The stock was sold primarily due to meeting the manager’s price targets at the time.”

Nevertheless, German aerospace firm MTU Aero Engines is known for designing the engines for Merkava tanks – a class of military vehicles used extensively by the IDF in Gaza, Lebanon and Syria – in addition to parts for Israeli naval ships. According to the FOI documents, USyd began investing in MTU from 30 June 2024 onwards.

According to Bloomberg, share prices of French arms manufacturer Safran SA have skyrocketed in recent years thanks to a “wartime boom”, with shares at a 5-year high as of 21 February 2025. Safran’s equipment has been used in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya in addition to other conflicts.

All five arms companies that USyd invest in enjoy record high share prices at the time of writing, meaning that the University will have received handsome dividends.

Outside of these five, the University historically invested in Austal, a major builder of Australian naval ships until the company was dropped after March 2023.

Woodward and Safran’s direct involvement in Israel’s war in Gaza and fierce criticisms from humanitarian organizations will likely force USyd to confront enforcement of its 2022 Investment Policy, which compel it to “identify and respond to human rights abuses” and adhere to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal.

Responding to these revelations, Australian Palestine Advocacy Network President Nasser Mashni urged Sydney University to “stand for justice and human rights” and divest from Woodward and other arms companies.

“When bombs used to massacre displaced Palestinians in a tent encampment in Rafah can be traced back to a company the University profits from, there is no excuse for inaction,” he said.

“By maintaining ties with weapon manufacturers complicit in the slaughter of Palestinians, the University of Sydney is betraying its students, staff, broader academic community and its ethical responsibilities.”

The University declined to comment on Woodward’s involvement in Israel’s attack on displaced Palestinians in Rafah.

USyd’s ties with opaque private equity funds raise concerns

Sydney University also allocates substantial funds to opaque private equity funds and asset managers such as KKR and Warburg Pincus.

KKR, one of the world’s largest private equity firms, has come under fire for leveraged buyouts that resulted in mass layoffs, wage reductions, and allegations of asset stripping, along with investments in fossil fuel infrastructure that conflict with the university’s climate goals, namely to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

“As of July 2024, Warburg Pincus had a 4.5% exposure to energy companies. The fund was committed to in 2015/16 before commitments were made to divest from fossil fuel companies. Warburg Pincus XII is a closed ended, illiquid vehicle which cannot be sold but will gradually return capital as underlying investments are sold. The University investment team has not recommitted to Warburg Pincus since that fund.”

Adding another layer of controversy is the university’s engagement with French banking giant BNP Paribas since September 2024. Despite its history of legal and ethical challenges, including billions in fines for sanctions violations and financial dealings with oppressive regimes. Notably, in 2014, BNP Paribas violated US sanctions by processing nearly $9 billion in illegal transactions for Sudan. The bank allegedly concealed transactions to bypass US restrictions, enabling the Sudanese government to fund mass murder and torture, despite being under sanctions for human rights abuses in Darfur. The University has stated that “BNP Paribas is USyd’s new custodian, providing safe custody and reporting services to the University.”

The University defends its investment strategy by claiming that its endowment is aligned with principles of responsible governance. Yet this lack of transparency makes it difficult for stakeholders, including students, staff and the public to accurately assess the ethics of the university’s investments.

Given the vast scale of USyd’s wealth, the community deserves more than a selective and opaque disclosure that prioritises commercial interests over the public’s right to transparency. As a public institution, the University must commit to revealing the full value of its investments, allowing the community to assess whether USyd upholding its environmental and ethical responsibilities, or diverting its wealth in the opposite direction.

The University spokesperson has published a statement: “Last year we established a working group to receive and provide feedback on our investment policies to ensure they reflect our commitment to human rights, including consideration of the position of defence- and security-related industries in our Investment Policy and our Integrated Environmental, Social and Governance Framework. The group is close to concluding their deliberations, and their independent report is due to be finalised soon before being presented to the Senate Finance and Investment Committee prior to it being tabled and discussed at the University Senate.”

Disclaimer: Luke Mesterovic is a current SRC Education Officer.

Read full article online. Rest in Peace Khanh Tran.

Ashes to Ashtray

I’ve never taken up smoking. When we were younger my brother and I, at my parents’ encouragement, would relentlessly bully my uncle into quitting via a whole manner of creative tortures: “No Smoking” signs recreated from Magnetix as he walked in the door; graphic stories about a man tragically dying of lung cancer with accompanying visuals of tar-blackened lungs and yellowed fingers; pressing our faces against the window in mock hysterics as he smoked a solitary cigarette by the firepit, coughing loudly and dramatically holding our noses as he came back inside. It worked, eventually. He doesn’t smoke anymore. (He claims hypnotherapy helped him quit. I maintain it was the Lego display).