The publication of Growing Strong, and all of WoCo’s work, takes place on unceded Gadigal Land. This land was stolen through a process of violent colonial- ism, and settlers are beneficiaries of the ongoing processes of violence and dispossession that begun on this land 237 years ago. The process and ef- fects of colonialism are ongoing, and our activism is incomplete without prioritising First Na- tions voices and causes. This requires decolonis- ing how we think and act, which is a constant process of listening, unlearning and challeng- ing colonial systems and hierarchies. We honour and respect the resistance, knowledge and strength of First Nations people, and commit to supporting genuine decolonisation, liberation and land back.

Hello, and thank you for picking up this year's edition of Growing Strong.

This year’s edition is guided by the theme of global feminist liberation, and our belief that solidarity is the key to liberation. During a time in which far-right politics are on the rise, it is more important than ever to stand together to resist systems of power. We are seeing unprecedented crackdowns on free speech and activism both within our university and in broader society, and in the face of this, we must raise our voices even louder.

In this magazine you will find analysis of Australian border politics, historical recounts of feminist revolutionaries, deconstruction of women in the military, discussions of the ongoing Stolen Generations, misogyny in the healthcare system, reflections on finding community and rebuilding identity after experiencing sexual violence, and more. We are incredibly proud of all our contributors and the variety of voices and perspectives we have captured this year.

A special thank you to our editorial team, and to the 2025 Sexual Violence Officers Lucy Sullivan, Saskia Morgan, Grace Street and Ishbel Dunsmore.

In love and rage, Your 2025 Womens Officers, Martha Barlow and Ellie Robertson

The University of Sydney Women's Collective is an autonomous feminist organising space open to women and gender minorities. Our feminism is centred around fighting patriarchal structures and gendered forms of oppression, especially where these intersect with capitalism, colonialism, racism and queerphobia. We organise around issues including ending rape on campus, abolishing the colleges, reproductive justice, First Nations justice and Palestinian liberation.

Front cover: Ethan Lyons Back cover: Saskia Morgan Editors: Sophie Bagster, Martha Barlow, Emilie Garcia-Dolnik, Ishbel Dunsmore, Ramla Khalid, Saskia Morgan, Ellie Robertson, Simone Scohel, Grace Street, Lucy Sullivan, Tanish Tanjil

Writers: Sophie Bagster, Martha Barlow, Emilie Garcia-Dolnik, Kayla Hill, Rand Khatib, Tara Marocchi, Lani Mulcahy, Ellie Robertson, Simone Scohel, Grace Street, Lucy Sullivan, Lilah Thurbon, Nessa Zhu

Artists: Lucy Sullivan, Sophie Bagster, Nessa Zhu

2. Burn The Colleges

4. The Carceral Pacific: Resisting Border Imperialism in Australia

6. Is BPD the New Hysteria?

8. Abante, Babae!:” A Brief History of Women’s Resistance in the Philippines

9. LIKE A DOG WITHOUT A LEASH: Feminist Anger for Change, Not an Aesthetic for Profit

10. In conversation with Johnathan Binge

13. Who Gets Justice?

14. Moan of Arc: I Die for Speaking the Language of Angels

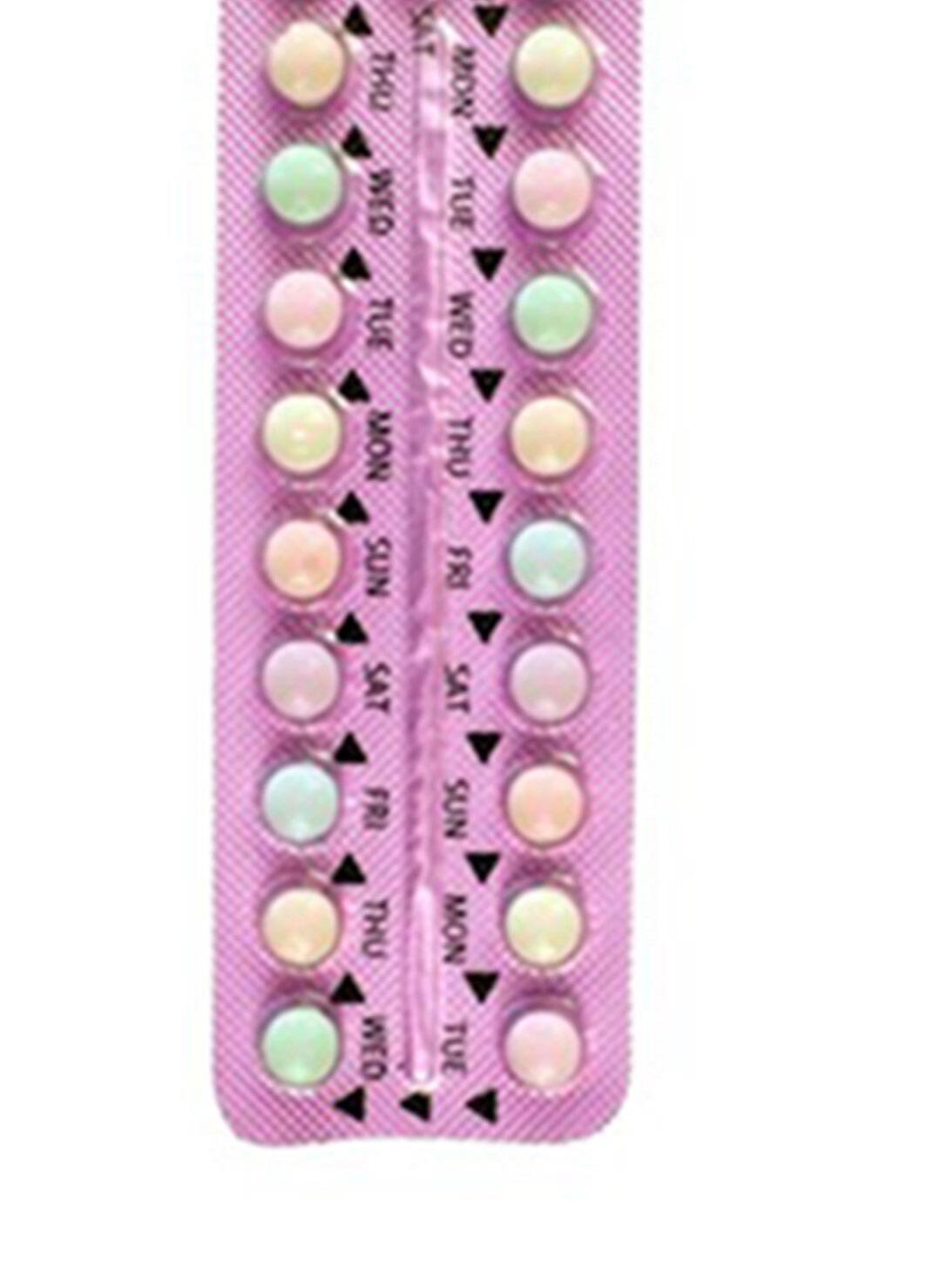

18. THe politics of the contraceptive pill

20. Purplewashing and the Girlbossification of the IDF

22. Into the archives: a history of women in the CPA

24. Only Love can Liberate Us

25. Untraditional Justice

26. Why so (un)serious?

28. Resources

29. WoCo Library

Martha Barlow and Ellie Robertson add fuel to the fIre

The University of Sydney is associated with 6 residential colleges which, for a fee of $26,000 to $43,000 per year, house almost 2000 students. The oldest college, St Paul’s, was established in 1856 at a time where only the wealthiest men attended university. Since their founding, the colleges have been responsible for perpetuating a well documented culture of horrific violence, bullying and misogyny that continues today. The colleges exist under confusing and outdated constitutions and acts of state legislation, and are primarily governed rent-free by various churches, giving them legal independence from the University. This means they are entirely self governed and have the freedom to create their own policies and responses to sexual violence.

The Broderick Report, published in 2017, found that college women are 6 times more likely to experience attempted or completed rape than non-college women, that 1 in 4 women had experienced sexual harassment at college, and that fewer than 1 in 10 victims made some kind of formal report. It also found that 1 in 8 completed or attempted rapes happen in Orientation Week. The AHRC’s Changing the Course’ Report found that at least 12% of all campus sexual assaults occurred within a college setting, however, this report was widely criticised for using inaccurate methods that lowered the actual numbers.

The groundbreaking 2018 Red Zone Report documents instances of bullying and sexual assault dating back to the 1930s. In 1958, “freshers’ were forced into hazing rituals involving being chased, bashed, burned with silver nitrate, bathed in tar and mud, and being blindfolded and dropped 30 miles from Sydney with no way home. from In 1977, the body of 18 year old Annette Morgan was found on the grounds of St Paul’s, with the post-mortem revealing she had been raped and strangled. The perpetrator was never found. Reports from the Women’s College include drunken men wandering naked up and down the halls and running around masturbating. Colleges have used misogynistic slurs and rape jokes to advertise social events, written and sung songs encouraging and making fun of rape, made Facebook groups for men to boast about sexual encounters and slut shame women, and carried out dangerous hazing rituals that force excessive drinking and have resulted in hospitalisations.

Whilst we would like to believe, and many do think, that this culture no longer exists, internal reforms have done very little to actually change the deeply entrenched culture of misogyny and elitism within the colleges. In 2023, St Andrew’s College was uninvited from attending inter-college Welcome Week events due to misogynistic and homophobic behaviour. The same year, a student had their ear bitten off during a college event. In 2024, just a few weeks later copies of the Red Zone Report were torn up at a Students’ Representative Council meeting. St Paul’s expelled 6 and suspended 21 students for a “prank” involving humiliating and sexually degrading a student.

Interviews with college students reveal that the effectiveness of internal reforms has only gone so far, even

in the women-only colleges. Two students we interviewed from discussed how they had begun to see more frequent punishments and less social pressure to participate in hazing and other college “traditions,” but that these behaviours still exist.

Amy (fake name), a student at Sancta Sophia, said whilst she felt the hazing culture at Sancta had largely disappeared, the other colleges are still “fucked.” She discussed the kind of community she found at Sancta, where the older girls gave presentations on consent, sexual pleasure and survivorhood, but that there is ultimately a sense of separation between Sancta and the other colleges. She described the general sense of revulsion they feel towards the other colleges, noting a sense of solidarity amongst the women at Sancta in how they travel in packs at college parties and warn each other of “Drew’s boys” to avoid.

Sarah (fake name), a former member of the Women’s College, conversely shared how even though the Women’s College purported to take sexual violence more seriously, the elite leadership structure made it difficult to separate themselves from the other colleges. Many of the girls had boyfriends at Paul’s, meaning that if a perpetrator was particularly well connected or liked, the students at Women’s would try to silence the (often younger) victims. She acknowledged that this culture of silence is also driven by a sense of fear; “because it forced them to recognise that they too might be unsafe in the colleges they called home.”

Even with mechanisms in place for reporting and punishing, Sarah explained, the culture within the colleges is still far too embedded. The seemingly “smaller” incidents constantly go unnoticed because they are just so ingrained. She explained that the sense of loyalty cultivated by the colleges is like no other, that the experience separates you so much from the real world that the normal rules of social interactions just feel like they don’t apply.

So whilst more expulsions and education seems to be a step, celebrating these too greatly ignores the fact that there are still structures in place allowing and encouraging this behaviour. In their elitism and structural separation the colleges encourage isolation, loyalty and silence. Punishment can only come once there has already been a victim. To truly put a stop to this, action must be proactive and preventative, rather than solely punitive. This is why reform will never be enough. This is why we argue for abolition.

What abolishing the colleges does not mean: knocking them down, actually burning them to the ground, taking housing away from students.

What it does mean: Abolishing the structure of the colleges, and replacing them with safe, actually affordable student housing.

The abolish vs reform debate is an exhausting one. Ardent college defenders are happy to accept reforms as enough, such as harsher penalties for perpetrators, mandatory consent training, and changing the name of O-Week to

Welcome Week to, according to the Broderick Report, “signal a shift towards induction and welcome, and away from the problematic connotations and expectations of the past.” Yet, the culture still remains. Year after year we hear stories of more hazing, bullying, misogyny and sexual violence coming from the colleges.

We acknowledge that many of these reforms have been made in good faith, driven by staunch and passionate advocates both within and external to the colleges. Many are off the back of vital reports such as the Red Zone Report, which was absolutely instrumental in bringing to light the culture within the colleges. However, many were also made by colleges in order to deal with the increasing PR problem they find themselves faced with. Ultimately, slow reforms that do not address the underlying structure do nothing except marginally improve conditions for students each year whilst saving the reputations of the colleges. This is why we say abolish.

In fact, any worthwhile change will always seem scary. This is the attitude that locks us into oppressive systems and makes us unwilling to confront reality; it all just feels too hard. When you are the beneficiary of systems of power, any attempt to dismantle that power can feel like a personal attack. It feels like something is being taken away from you. Why push for radical change when you had such a great time at college? Why do these stupid feminists always ruin all the fun?

But the Abolish the Colleges campaign has never been about taking things away. We want students to be housed. We want students to be safe. It is a campaign that envisions a positive future out of the ashes of the current system. One of inclusivity over elitism, community over hierarchy, accountability over silence. The unfortunate reality of feminist campaigns is that their strongest advocates are written off as killjoys, as manhating feminists, driven by spite and anger to take something away from those in power. It is never considered that our anger is justified, that the joy we seek to kill is the kind built off violence and discrimination against women.

If your instinct is defensiveness, we ask you to consider the trade off. To consider what has been taken away from the countless victims of sexual violence within college walls. How the college system has taken away people’s safety, trust, friends, networks, housing, and, sometimes, their lives. Is your boys club so precious that it is worth taking away all this from victim-survivors?

The carceral-colonial state is the antithesis to a feminist ethics of care across demarcated borders. The fortification of Australian borders and manifest regimes of violence, namely through off-shore and on-shore detention centres for refugees and asylum seekers, is a pervasive reminder of the status of socalled “Australia” as a colonial nation. Indeed, to Walia (2021) and within the discipline of border studies, the border is configured as a ‘key method of imperial state formation, hierarchical social ordering, labor control, and xenophobic nationalism.’ Hyper-security, militarisation, policing, as well as arbitrary violence and cruelty, are endemic to Australian border policies, where the quest for white nationhood renders marginalised bodies into targets for normalised state violence.

“Migrants are scapegoated and legitimised as threats within the Australian consciousness, with manifest implications of human rights abuse and normalised state violence.

Concurrently, Australian Feminist Foreign Policy, as operationalised within the WPS Agenda, represents a shallow attempt to obscure this violent Australian presence in the Pacific. Resisting border imperialism is integral to feminists worldwide, where militarised borders become the physical manifestations of the partitions between us.

The history of Australian migrant detention policy is an ongoing narrative that generates violent xenophobia and community vilification to legitimise the violent incarceration of refugees and asylum seekers. The insidious mandatory detention policies of Australian governments since Keating in the early 1990s have bolstered a militarised conception of ‘national security,’ where migrants are scapegoated and legitimised as threats within the Australian consciousness, with manifest

implications of human rights abuse and normalised state violence. Subsequently, under the Howard government, these policies became the ‘Pacific Solution,’ and detention centres were constructed internationally on Christmas Island, Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Nauru. While the policy would briefly suspend under the first Rudd government, it would be reinstated under Rudd’s second term in 2013, where Rudd infamously announced that no person seeking asylum by boat would ever be allowed to settle in Australia. Federal elections held in the same year saw Tony Tony Abbott successfully campaign on a ‘stop the boats’ slogan. Consecutive Liberal and Labor would offer amendments to these policies without their dismantling, despite continual criticisms from global human rights organisations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. It is worth noting the continued use of on-shore detention centres, such as the Villawood Immigration Detention Centre, whose inhumanity and entrapment are well documented, notably by Safdar Ahmed in Still Alive.

The Refugee Council of Australia notes the hundreds of millions of dollars paid by Australia annually to both Nauru and PNG to operate these detention centres, effectively creating a monetary incentive for these countries to incarcerate. Australian foreign relations fostered through a ‘cash-for-migration control’ approach are indicative of an encroaching Australian power in the Pacific predicated on the proliferation of colonial apparatus. The carceral archipelago represents distant outposts of the imperial power centre, where racialised communities become legitimate targets of state violence to bolster ethnically homogenous conceptions of national

security. Behrooz Bouchani, a Kurdish-Iranian journalist and former detainee of the Manus Island Detention Centre, configures detention as operating within a kyriarchal framework, that is across the intersections of race, gender, and class. The system of cruelty, to Boochani, is enacted to punish refugees and asylum seekers, and also maintain control over migrant and marginalised communities. These offshore detention centres operate as the new Australian frontier, where hypersurveillance techniques and the violent exercise of power can be inflicted and tested against vulnerable populations. It is important not to extricate these policies from the history of Australian border politics. It is within these militarised border policies that the White Australia policy continues, and the quest to transform so-called Australia into a white nation persists. Carcerality, in all its manifestations, is inextricable from coloniality.

In 2021, the Australian government released its second National Action Plan (NAP) on Women, Peace, and Security. The document represents the implementation of the UN’s WPS agenda, and ostensibly signifies a prolonged commitment to protect human rights, promote women’s participation in decisionmaking processes, prevent conflict, and support women and girls in relief and recovery efforts in Australian foreign policy. The NAP is predominantly targeted towards the broader Indo-Pacific, seemingly glorifying Australian international presence as a benevolent endeavour, as well as disguising the cruel realities of Australian presence in the Indo-Pacific. The document, as such as such, only signifies a commitment to a colonial conception of feminist foreign policy, where an encroaching Australian power can lay presence in the broader Asia-Pacific under the guise of “feminism,” without actively committing to peace through demilitarisation or to better human and migrant rights in the domestic sphere. These two governmental policies in reality thus operate together to fortify the colonial state. Of course, the Australian presence is overwhelmingly linked to the military, where the defence department ‘operationalises the priorities’ outlined in the

NAP. Australian presence in the Pacific is then militarised through both the operation of the WPS agenda and through offshore detention policy.

Eradicate the Border, Decolonise your Feminism

“These offshore detention centres operate as the new Australian frontier, where hyper-surveillance techniques and the violent exercise of power can be tested against vulnerable populations.”

Within Feminist Foreign Policy (FFP), the dissolution of the border is the ultimate end goal. In a world governed by an ethics of care, there will be no need for such hyper-securitised and militarised fortifications of the nation-state. While enacting these insidious policies against asylum seekers, Australian leaders espouse rhetoric of anti-racism and ‘tolerance,’ failing to recognise violent racism as endemic to Australian culture. Ghassan Hage warns against white liberalism, conceptualising ‘multiculturalism’ as a tool to both disguise regimes of cruelty and violence, such as offshore detention policies, as well as normalise and glorify the colonial state as bastions of ‘tolerance.’ Dismantling this colonial state means rejecting these shallow concessions and advocating for liberation in the dissolution of the fortified and militarised border regime. It is incumbent upon all feminists to rebel against borders everywhere and the attempts to eradicate human rights to movement, freedom, and asylum; from Mexico to Palestine to so-called Australia.

Sources:

1. Walia, Harsha, et al. Border & Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism. Haymarket Books, 2021.

2. “Offshore Processing Statistics.” Refugee Council of Australia, 16 Oct. 2024, refugeecouncil.org.au/ operation-sovereign-borders-offshore-detentionstatistics/7/.

3. Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Defence;. “Gender, Peace and Security at Defence.”, 9 Sept. 2024; defence.gov.au/defence-activities/ programs-initiatives/gender-peace-securitydefence.

To be a woman accessing healthcare is to be caught in a double bind: defined by your body, and yet dismissed because of it. ‘Attention-seeking’, ‘dramatic’, ‘emotional’ — conceptualisations of women’s madness cycle through the centuries, and yet these labels stay at the forefront.

One of the most enduring examples of this is the diagnosis of hysteria, a condition that was widely accepted and deployed throughout the 19th century. However, the roots of hysteria stretch back much further. As early as 1900 BC, figures like Hippocrates and Plato in Ancient Greece identified the ‘wandering uterus’ (hystera) as the source of a variety of ailments in women. This concept evolved over time, famously with witchcraft and satanic possession between the 15th and 17th centuries, further entrenching the association between women’s bodies and their supposed irrationality.

This shift allowed hysteria to become weaponised as a convenient tool for men to explain away anything they found unmanageable in women as attributed to their ‘natural hyperfemininity’. Symptoms ranging from extreme emotions, anxiety, and depression to somatic manifestations such as fainting spells and paralysis were all disregarded as they were simply exaggerated versions of what women were assumed to be by nature: emotional, dependent, and unstable.

Academics now recognise hysteria as not an explosion of women’s individual flaws or psychological maladies, but more of a reasonable reaction to the oppressive structure of society that they were attempting to resist — better explained as pathologies of society. This reframes hysteria as more than just an ‘extinct’ diagnosis, where such labels have historically and continue to be used to police and reinforce narrow ideals of women’s behaviour.

Although hysteria was taken out of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1980, its legacy of gendered pathologisation of emotions continues. Most striking is in the overdiagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) in women, with 75% of those diagnosed being female, according to the DSM-IV-TR. This significant disparity raises questions about there being genuine biological or sociocultural differences

between men and women that contribute to this imbalance. The research base for studies that assess gender differences in BPD are (unfortunately, but not surprisingly) scarce, but generally suggest the skew to be due to sampling bias or diagnostic bias rather than any ‘natural’ divergences.

A 2024 review found that there was likely a bias in diagnostic thresholds; “inappropriate and intense anger” was considered more ‘pathological’ for women than men, despite being more frequently reported in men. This is to say that compared to men, the occurrence of such anger was characterised as psychologically abnormal ‘for women’ and a ‘symptom’ of something more malingering. This isn’t limited to BPD either. A review of 77 chronic pain studies observed that women’s pain is frequently psychologised, where reports of pain are construed as ‘hysterical, emotional, and malingering’ in comparison to the usual description of men as ‘stoic’.

As long as psychological strain is interpreted to be feminine-coded and ‘lesser’ in relation to somatic conditions, the tendency to pathologise and medicalise women’s mental states will continue. This escalates in the context of discussion on BPD, which is characterised by instability across multiple domains; affect, relationships, self-identity, and impulse control. The prevailing theory on its development — emotional dysregulation deficit — suggests BPD arises from the interaction of biological vulnerability and an invalidating parental environment. Within these complex interactions, abuse and neglect consistently emerge as significant risk factors, with sexual trauma identified as the single biggest predictor of a diagnosis of BPD. To clarify: abuse alone is neither necessary nor sufficient for the development of BPD.

Subject to prominent and continuing discourse for the past couple decades is the large overlap between BPD and complex PTSD (cPTSD). cPTSD comes as a controversial diagnosis in being defined by prolonged exposure to ongoing trauma as opposed to a singular traumatic event as in PTSD. Although supported by a large body of peer-reviewed research, it is only included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) and has yet to be added to the DSM despite various attempts. Whilst most individuals with BPD also fit the diagnostic criteria for cPTSD, the reverse is not true.

The symptomatology overlaps between cPTSD and BPD include experiences of poor emotional regulation, self-harm, suicidality, and high levels of interpersonal problems and stress. A troubling pattern emerges: women who meet the criteria for cPTSD are frequently misdiagnosed with BPD. Emblematic of gendered medical attitudes, what results is a reality where women are punished for their trauma responses as evidence of ‘inherent instability’.

This all perpetuates the same dynamics that historically upheld hysteria as a diagnosis — a tool for discrediting women’s experiences.

In cases where a diagnosis of cPTSD is more appropriate, women are misdiagnosed at higher rates with BPD than cPTSD. The treatment of survivors is significantly influenced by the imposition of a diagnosis or label. cPTSD involves more traumafocused therapy approaches, where the survivor is validated on how they feel about their experiences. On the other hand, BPD therapy focuses more on impulsivity, improving interpersonal relationships, and moderating difficult emotions.

Even in cases of correct diagnosis of BPD, treatment is rife with invalidation that can result in epistemic injustice for the survivor. Meaning, a personality disorder suggests that the individual may be unaware of, for example, maladaptive tendencies. The diagnosis itself can degrade the credibility of a patient’s personal experiences as clinicians are more likely to undermine a patient’s authority in a way that goes against therapeutic aims of collaboration. This isn’t based on guidelines, but instead the deep social stigmas attached to BPD diagnosis surrounding being ‘unstable’ and ‘crazy’.

This labelling is further harmful as it suggests that the problem lies within the survivor’s personality rather than a result of their traumatic experiences. In the case of survivors of sexual violence, the status quo of dismissing women’s concerns is upheld by labelling them as ‘dramatic’ and ‘manipulative.’ Patients who are already in a position of vulnerability are unlikely to challenge a clinician even if they believe they are being misdiagnosed, as they are construed to not be as trusted as a treatment professional.

Addressing the systemic inequalities that lead to women being overdiagnosed with BPD and arguing that diagnosis can hinder the treatment and recovery of patients is not to invalidate or claim that the diagnosis of BPD has zero value. It is rather to draw attention to the psychiatric labelling and pervasive stigma that deem the individual as ‘damaged’, shifting responsibility onto the survivor instead of addressing the systemic denial of experiences of sexual abuse

experienced by women and girls.

Standing as the ‘default’ diagnosis for women perceived to be too angry for society’s standards, a BPD label can reduce the complexity of trauma to something unchangeable, pathologising survivors in their methods of resistance and interpretation of their experiences. If we continue to dismiss distress as a symptom of a psychological condition mainly attributable to women rather than a realistic response to harsh realities, we continue to deny the appropriate treatment and agency of those who have already been silenced.

To be a woman accessing healthcare is to be placed within another double bind: to be punished for expressing too much emotion, yet dismissed for not expressing it the ‘appropriate’ way. If you’re angry, you’re simply crazy.

Philippine women’s resistance has forever been tied to organisation against Spanish, Japanese, and American colonisation. West and Kwiatowski configure this resistance as against the ‘incursion of foreign male domination of ethnic-cultural communities in an attempt to maintain sovereignty and leadership roles.’ Within the Philippine public consciousness, female ancestors are imagined as strong resistors to colonial conquest. In ‘The Historical Construction of the Filipino Woman,’ Quindoza Santiago argues that the Spanish caused the direct ‘downgrading of Indigenous politicalscientific-cultural order [which] wrought a deep form of subjugation on women’s experiences and the expression of these experiences,’ as well as the ‘complex ramifications of patriarchy over the whole archipelago.’ It is within this context that Women’s resistance first emerged and continues to operate today.

Gabriela Silang is perhaps the most notorious female nationalist leader in the history of the Philippines. Following the death of her husband, revolutionary Diego Silang, Gabriela assumed her husband’s role as commander in attempting to liberate Ilocos from the Spanish. On September 20 1763, Gabriela and her troops were executed by hanging in Vigan by Spanish imperial forces. The legacy of Gabriela Silang is deeply interwoven within Women’s activism in the Philippines today. Resistance to both patriarchy and colonialism proved continuously necessary by a growing Philippine nationalist movement that sought to sideline women’s issues. Women continued to organise against the Japanese in WWII, against Martial Law by the Marcos presidency in the 1970s, and for law reforms stemming from the Spanish imperial order. Today, women’s issues are tabled in the name of Gabriela Silang, by the GABRIELA Women’s Party and the GABRIELA grassroots alliance of over 200 organisations across the Philippines.

GABRIELA: The National Alliance of Women’s Organisations

GABRIELA, the national alliance of women’s organisations in the Philippines, formally recognises 7 key issues as the focus of its campaigns: (1) Sex trafficking and prostitution; (2) Domestic Violence; (3) Rape, Incest and Sexual Abuse; (4) Sexual Harrassment; (5) Violence as a result of political repression; (6) Sexual discrimination and exploitation; and (7) Reproductive healthcare. Its political scope, however, also targets ‘land reform, militarism, and forced transnational migration’ through the creation of ‘mutual support networks to challenge interpersonal

violence, while simultaneously building a left movement against capitalism and US Empire,’. According to Chew in ‘Bringing the Revolution Home: Filipino Urban Poor Women’, “Neoliberal Imperial Feminisms,” and a Social Movements Approach to Domestic Abuse.’, the forefront of the party’s work remains the analysis of class, ethnicity, race, and gender. Modern Filipino politics are consistently defined by fortifications of a masculinist and militarised state, with Chew arguing the state has leaned towards carceral feminisms, overlapping ‘inseparably with neoliberal development and neocolonial militarisation.’ As a result, GABRIELA’s community organising principles and survivor-centred mode of operation thus ‘transcend carceral feminist remedies.’ remaining an integral community-led force for feminist liberation in Philippine society.

In 2000, GABRIELA established its own political party, the GABRIELA Women’s Party, broadening its scope to include national and legislative advocacy. Within its history, the party has openly opposed US military bases, criticised sex tourism, and protested against police and military abuses. It too ‘points to the US neocolonial domination of the Philippines as an underlying, but often ignored, factor in exacerbating interpersonal gendered violence.’ Since its inception, the party has seen successes in drafting, and passing legislation against trafficking, and violence against women and children. Unfortunately, other proposals against neoliberal development and militarisation, notably against mandatory military training for youth in the context of South China Sea disputes, have not garnered congressional approval. Resistance against violent colonial masculinisms continues

“Abante, Babae!” A Brief History of Women’s Resistance in the Philippines

Emilie Garcia-Dolnik leads the way

for the GABRIELA Women’s Party and the activists campaigning for feminist liberation across the Philippines. Over the past few years, GABRIELA party members have stood at the forefront of campaigns for the legalisation of divorce, as well as the decriminalisation of abortion. Today, the party has over 100,000 members across the Philippines and diaspora.

The legacy of Gabriela Silang persists today in the landscape of women’s resistance in the Philippines. Against an increasingly militarised and masculinist world, GABRIELA activists on the ground are constantly organising and adapting to challenge colonial conceptions of the nation-state, especially those that exclude women and permit an advanced and continued state of violence against the body. Endemic to this resistance has been an innate understanding of the inextricable relationship between feminism and decolonisation; a relationship that remains especially relevant for feminists everywhere, and that cannot be severed without transnational solidarity for liberation.

Glossary: Abante = tagalog for movement/ progression forward Babae = Girl/Woman.

Just like Le Tigre’s hit song “Hot Topic” from 1999 shouting out feminist artists that have inspired them, feminist anger remains on the tip of our tongues and on the tips of our pens. Audre Lorde has written poetry and spoken at length about feminist anger being used to respond to racism, and it has been a feature and goal of many womenfronted punk bands for decades. Feminist anger is a privilege and a force for change, but in 2025 it seems to be evolving into something profitable and directed away from systems of oppression. We need to get back to the roots of feminist anger – taking it for ourselves and using it to work towards the liberation of all.

Like many underground movements that challenge systems of oppression, women-led punk has been co-opted. It seems that nowadays the media feeds us the narrative that feminist anger is fun and aesthetic, but only in small doses and targeted towards a man that has personally wronged you. A common depiction of this is the heteronormative, Western trope of the girlfriend getting revenge by hitting the expensive car of her shitty ex. Feminist anger has been identified as a threat to bear the will of capitalistpatriarchy by deforming it, rendering it fetishised, commodified, and redirected away from oppressive systems and towards individuals.

So, today it feels almost harder to attain feminist anger, for it has now been repackaged and sold as feminist hatred, as to maintain the status quo. Audre Lorde made this distinction between anger and hatred in a keynote presentation in 1981 “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism.” She says, “...this hatred and our anger are very different. Hatred is the fury of those who do not share our goals, and its object is death and destruction. Anger is a grief of distortions between peers, and its object is change.”

their lyrics are?

Mannequin Pussy’s 2024 ‘I Got Heaven’ tour has received high praises, following on from an excellent album of the same name which features the extended metaphor of being an unleashed, unpredictable dog who will bite when it wants to. Kimberly Kapela recounts that in their Chicago 2024 show, MP’s frontwoman Marisa Dabice spoke to the audience about unleashing their anger and about the ongoing genocide against Palestinians. This was followed by their classic discography with songs like the antipolice anthem “Pigs Is Pigs." Their musical processes themselves also go against the capitalist grain of massconsumerism, with full creative autonomy, breaking aesthetic boundaries, and featuring

The riot grrrl feminist punk movement - beginning in the early 1990s - took this in its stride, tackling topics of gender, race and class with the iconic spoken and shouted lyrics in stripped-down and fastpaced songs of punk. Riot grrrl is made unique by its underground subculture and feminist networks that brought women together in an environment to express and assert themselves to combat the male-dominated nature of punk.

This is not to say that feminist anger should be policed and only allowed if productive, but that we should be aware of the difference. Men, of course, are awarded the privilege of being allowed to have imperfect, unproductive, and harmful anger. However, we have a duty to do more. Lorde speaks at length about white women needing to use their anger to stand in solidarity with women of colour, whose rage is often labelled as “useless” and “disruptive.”

This is what is largely missing in the mainstream and what I am searching for in 2025. I check off the contemporary womenfronted punk bands I like the most – Mannequin Pussy and Destroy Boys – to see how they square up compared to riot grrrl and Lorde’s work. These two are known for their punchy name flagging feminist values and songs featuring feminist rage, but I needed to know: do they put their money where

Similarly, Destroy Boys have also used their tours to create community and facilitate safety with a “no boys allowed” pit and to platform Mental Health First Oakland, a local non-profit promoting an anti-carceral response to mental health crises. Their frontwoman, Alexia Roditis, has also been vocal about Palestine and protest on their social media, saying “get out of your comfort zone for two hours and go to a fucking protest please” and offering a private acoustic show to those attending pro-Palestine protests.

They provide a good glimpse into what using your platform and privilege to allow others to express themselves and express their anger looks like, and the responsibility to channel that anger into something that works towards our collective liberation, rather than something to go viral on social media and make a profit.

That’s putting your money where your

My name is Rand Khatib, I’m a member and previously the convenor of the Women’s Collective. I chose to interview the raw and inspiring Johnathan Binge after hearing him speak about his experience with the Care system. As feminists organising on stolen lands, we should recognise that bla(c)k women and families experience the violence of patriarchy in a unique way - often veiled to white australia. I hope this interview (which can be viewed in full via the QR code) can shed some light on one such experience. I urge you to further hear first-hand from local truth-tellers by showing up to actions, like the protest each year on Invasion Day on 26 January or the rallies marking ‘Sorry Day’ on 27 May. You can also find more information via Grandmothers Against Removals, the Kinchela Boys Home, the Blak Caucus, Aboriginal Legal Service, Mudgin-Gal Women’s Place and many more Aboriginal self-determined organisations.

This conversation was recorded on unceded Bidjigal land, where ongoing resistance to colonisation commands our attention and action. First Nations readers should be advised that this article contains references to colonial violence.

HAD BEEN TAKEN FROM OUR MOTHER”

2021: Johnathan performs at the Invasion Day protest in Naarm, photo by Ben Tarlinton

My name is Johnathan Binge. When I do music, people call me Caution: different ways, different people.

I’m Gamilaraay, Dunghutti and Gumbaynggirr. I was born on Country in Moree NSW and I’m currently living in Naarm.

Read the full interview - scan the QR code here!

Johnathan, can you tell us what the Stolen Generations are? Did they ever end?

The Stolen Generations were a systematic set of policies made to punish black parents in various ways. Essentially, it was the forced removal of young ones from their parents and that started a little bit before and continued on through when ‘white australia’ policies were being enacted... The Stolen Generations are continuing because the same policies that created institutions like, in my Pop’s sake, the Kinchela Boys Home would eventually lead and feed into child protection services that still systematically strip black babies from their families to this day.

more young Blackfullas and black babies are being taken from their families today than said time period of the Stolen Generations

2013: Johnathan (13) and his three younger brothers (7, 6, and 4) were separated from their mother at this age.

We had been stripped away from our mother, taken from her for a while. She would end up committing suicide and then, when I chose to continue the stuff I was doing as a young person, which weren’t very good things, eventually my younger brothers and I were [forcibly] split from each other.

What was out-of-home care like?

What I will say about the out-of-home care system is they exist solely to further serve to uphold colonial rule, and within that comes policing young black bodies and young peoples’ bodies in general. The way out-of-home care units are set up is cut and paste, and the layout is planned to ensure full supervision of the young people residing there; they act as compounds where the outside world is made to feel separate and closed off. Small things like the doors being deadlocked at times. At certain points in the night, depending on what’s happened through the day or what worker is running nights in the unit, you were limited to plastic cutlery and drawers would be locked with a key as punishment.

How does the theft of children from black families feed cycles of trauma?

It just feels like a revolving door. We grow up with the stories of our people being taken. You grow up knowing that these things happened and, especially to the outside world, essentially gubbas, who have this prevailing [view] that the Stolen Generations were so long ago and would never happen in today’s time, let alone to a young Aboriginal person. Then it does happen...

Why does the system exist in this way? Why is this happening to me? Am I an inherently bad person like they say I am? That’s something I was left to battle for a long time. I fear it is something that young people today are still fighting with — those feelings of abandonment, those feelings of persecution, the experience of oppression when it comes to police rule over young peoples’ bodies and autonomy. Not just the police but the workers that you grow to have unsure relationships with. The people you interact with on a day-to-day. You have to question: what is their intent?

It’s inhumane to have young people go through this and live through this sort of mental state.

What do you think the solutions look like both short-term, immediate support, but also long-term systemic change?

Addressing systemic change within a community, and making sure people are housed and fed... Long-term solutions — fucking land back. Mob have the solutions, we’ve had these solutions for thousands of years. We just have to uphold our sovereignty and stay working within that power.

How can activists support to keep black babies in community and support the fight for land back?

Being engaged within community is an important thing. Understanding who is within your immediate community, especially who you work with —black people, mob, BIPOC. You need to understand who is there and what their needs are. Just as you would go out and put your body on the line to stop arms going out to apartheid israel, you put your body on the line to make sure these kids aren’t being taken from their parents and families.

Some mutual aid accounts you can contribute to...

Mutual aid goes back to the way mob operate. Simply put: meeting the needs of individuals in your community. It’s such an innate way for us to take care of each other that comes with compassion. It’s a call back to the strength in community days where the needs of the people are met by the people. It comes solely out of love.

For any other young person that has ever gone through the system. I know how fucking disgusting it is and how hard it is to pull yourself out of that. I’m sorry that it’s been left up to you to pull yourself out of that... It goes back to the strength of our community and making sure we’re in touch with our people, that’s for mob specifically.

The term, “girls supporting girls”, has gained popularity through social media in the past decade, allowing women to come together. Whilst the term seems almost juvenile, it asserts the importance of unconditional female unity and protection, and demonstrates the incredibly monumental power of media within movements. However, as it has become something of a buzzword, it tends to focus on smaller, interpersonal instances of solidarity rather than building genuine allyship to dismantle patriarchal structures that isolate women and pit us against each other.

An example of this isolation is the societal response to sexual violence, where women are frequently disbelieved whilst their perpetrators are protected. The inevitable victim-blaming that occurs whenever tragedy and assaults are forced onto women renders women equally afraid and traumatised of the “after” as they are during the event. Victim-blaming takes on dozens of faces - it can be the media glorifying the male perpetrator as a “good bloke” whilst labelling the woman “promiscuous” or “mature for her age,” the legal systems asking, “what were you wearing?” and “how much were you drinking?” When women are asked, “why did you stay?”, it’s a failure to consider the financial and safety factors that prevent a woman from leaving their abusive partners and seeking help. This particular isolation is further increased through the fear of doubt from those they are seeking help from, and a fear of repercussions from their abuser. The questioning, speculation and gossiping, the “he said, she said” overwhelms the voice of the survivor. Rather than hearing their story, only the voices of everyone else are heard.

It is a level of scrutiny and shame that we do not ascribe to other crimes. When someone is stabbed, or robbed, no one is asking, “why were you there?” Sexual violence is the one crime that forces a barrage of blame and questioning onto the victim rather than the perpetrator. The Westminster system we have in Australia encloses us in a rigid framework that allows little space for change and progression without monumental reform, preventing a legal system that reflects the values of larger society and addresses concerning issues properly. Currently, the level of victim blaming and lack of justice is an inevitable experience that is so deeply entrenched within our society and reinforced through the carceral legal system that upholds patriarchal values, allowing men to avoid serious consequences and women to face trepidation and doubt, rather than achieve adequate justice. Furthermore, the impacts

of victim-blaming are intensified through the enduring experience of women of colour, and the amount of justice and attention brought to their cases are largely disproportionate compared with white women. Whilst the carceral legal system frequently fails survivors, white women are still more likely to at least have their cases make it to court. The term, “missing white woman syndrome” encapsulates the disproportionate representation. The term, penned by AfricanAmerican journalist Gwen Ifill, recognises that white, upper-middle class, attractive women receive more attention from the media whilst women of colour are underrepresented. Despite being an American term, it is incredibly applicable to settler-colonial countries with a large white population like Australia, the UK, Ireland, Canada and South Africa. It is a system upheld through patriarchy and racism, further dividing women through the suggestion one particular woman is worth more than another.

The current liberal feminism movement centres white cis women at the forefront, pushing women of colour, non-binary people and transpeople into the background. This decentering prevents collective justice for all women. In the media, ongoing and consistent spotlight is given to white women whilst BIPOC women are left unnamed. For example, the #MeToo movement, whilst prolific and monumental, failed to bring equal awareness to all women, and instead focused largely on wealthy, elite white women. Whilst this “girls supporting girls” trend is beneficial in creating unification, it exists on a superficial level, and instead lacks the ability to implement progression and active change, rather, that is dependent on reform and revolution.

Whilst the idea of “girls supporting girls” covers personal instances of feminism like not shaving our armpits, it alone lacks the radicalness that is necessary for feminism to achieve further change and the radicalness that relies on intersectionality and the collective support and efforts of everyone. It is up to all women and girls to support each other and to support other minorities if we expect to dismantle the patriarchy and ensure consistent and enduring equality for everyone. There needs to be more space for BIPOC women, non-binary people, and trans-people, and the narratives of survivors need to be retold authentically and wholly. Rather than emulating base-level trends of feminism, there needs to be urgency placed instead on ending the system that upholds racist, patriarchal standards and a lack of justice for women.

“Is a woman steering her high horse, with desires of her own, likeable? Only if she steers her horse off a cliff. She is allowed to be exceptionally skilled at dying.”

- Deborah Levy, Real Estate

Playwrights Notes:

All stage directions are in italics. This is not a play for looking - the female body innate for doing rather than being done to. Eyes closed. The director should be aware of avoiding a patriarchal staging of the feminine experience. Give in. This is a memoir (for now) for now.

ACT I (the first, the only)

Backstage, the DIRECTOR adjusts the script.

Lights up on THIS GIRL. She stands centre stage: an antique-store-meets-junk-yard. Everything is labeled, cluttered, clunky. The actor should be cautious of her movement: as to not break anything on set. There is nothing else. She moves with the words: it is somatic, mechanical, it’s a personal essay (she’s never written one). She sits; she stands. She is everywhere; eternal.

THIS GIRL

It begins, at first, with the acute cortisol. Yes, that’s right. The fight or flight hormones, à la epinephrine. Adrenaline, if you’d like: the angel of the bloodstream. The pair are thorough anesthetists and madly in love with one another: they like to fuck in the mesolimbic system while nobody’s looking. The reward system. The pleasure centre. The word is unclear, it’s sticky and only vaguely familiar. It sounds a lot like romance and feels like an open wound: the one between the legs. Filled with mud, cement. A slit, a cavity, pit, trench, a depression - a capital ‘H’ Hole. It’s a silent rage, a pussy sounds like a quiet thing. Is there liberation from out of these depths? To not have to be anything but the Hole if it is mine - which it has and always will be - I should be able to give it freely and willingly. On my own accord. Full of control, a permanent revolution. There need be no room for pleasure when there is control

CONTROL (THAT GIRL)

I’m here now, darling

A beat. The girl pauses: the space is still empty.

The body is moved by somatic forces nothing short of spectral, the hyper of the sexuality only referring to the agitation of the host: this is a haunting of sudden desire. Do you believe in ghosts?

She turns directly to the audience: an empty auditorium. Sounds from backstage. The DIRECTOR is somewhere, we cannot see him but we know he is-

THIS

There are Google-able symptoms. Just to double check. Do I often feel out of control? Reckless? Trouble sleeping? Am I suddenly receptive to the sexual potential of everyone I pass in the street, opening to me as if upon the meeting of my resistance and his tenacity birthed a third act? A possibility of control sprung from a destructive conception? I have become wet earth for these ideas, they take root in me, grow wild, choke me. Can you picture it?

A GIRL stands centre stage. No, she’s in the wings. There’s a woman in the wings who is covered in oil paint - or is it mud? Thick, lacquered upon her skin. Can she breathe? I’m not sure. You could ask her-

THE DIRECTOR

No, I believe she is to have wings, not to stand in them-

THIS GIRL (hesitantly)

I receive an email with the subject BAD-TIMES and delete it immediately. The body is a weapon of mass destruction and tonight it lands on a small village called Hinge

The girl finds a full-bodied male MANNEQUIN. It is naked. It has been onstage the whole time, you just didn’t want to notice it. The pair move closer to one another: a hunt.

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP

Where should I put my-

THIS GIRL Hands? My waist

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP

You have an immaculate-

I find, after a while, the suitors all melt into one giant Inner West film boy. He likes Deftones and long walks on the beach. Seventeen sets of eyes: he’s made of angles, all elbows and happy-to-see-me’s. It’s easy. It’s like cardboard. It’s like brushing my teeth

CONTROL (THAT GIRL) Spit, swallow, release

A beat. This is memoir. This is not in the script.

Silence, the auditorium remains empty. She looks back at the DIRECTOR in the wings, mouthing to him. He pushes his glasses further up his nose (you cannot see it). THIS GIRL and the MANNEQUIN begin a highly stylised and animated kind of intercourse. The MANNEQUIN moans are pre-recorded and echo through the entire space. After a while, they sound like crying.

And then I wonder…how many people I can teach to slow dance and thenI reinvent myself. I call her Moan of Arc. Moan of Arc lies on the couch. Moan of Arc stares at the ceiling. Moan of Arc feels…nothing. It feels good. I wield my sword. I take it to the grocery store. I buy oranges and lube. I drink myself through a box of Earl Grey and don’t touch myself once. I wince when others do: I shut them up with my body, shut up shut up shut up. Lay down. I go through the motions. Spit, swallow, release

She turns back to the DIRECTOR.

THIS GIRL

(pretending to be an essayist)

What does it mean to manufacture yourself? From out of the darkness came the slow and sultry anesthetists: the sudden desire to be mechanical. To be nothing at all. A rage akin to E.T.A. Hoffmann’s slight adoration with automata in his short stories that births Olimpia, an automaton with human eyes. Was it she who was programmed to only shout “Ah! Ah!” or was it the hero, Nathaniel who was wired to believe that this was what we called depth? That the object of his affection is not even a Real Girl, that her humanness was set like amber inside of her: he cries “...oh, inanimate, accursed automaton!” Did he think that he could touch it if he lifted her sheet metal skirt? The inside of her as the only thing worth conquering. The masculine need to colonise. She was a robot: designed and destroyed at their hands

A beat. Everything goes silent.

THIS GIRL

This- this happened to me

A stage flat falls behind them.

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP

Happens to everyone, don’t stop now-

THIS GIRL

I want to ask for my body back-

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP

Seems you already have one

THIS GIRL No, I-

CONTROL (THAT GIRL)

You’re carrying the guilt of living like a souvenir

THIS GIRL

This was not how it was written, it’s supposed to be-

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP Liberating?

THIS GIRL Yes

CONTROL (THAT GIRL)

You saw yourself in that mirror and you didn’t think that, did you? Do you remember what you thought you were?

THIS GIRL

A painting-

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP

A spider, you thought you were turning purple. Not like the romantic nudes…something grotesque A beat. The DIRECTOR rubs his hands together. THIS GIRL tries to find him behind the curtain. She’s yelling.

THIS GIRL

Line? Can we start again? I need a break

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP

Soph-

THIS GIRL

It’s Moan of Arc! A beat.

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP

It’s opening night

The pair look out into the audience. The auditorium remains empty. THIS GIRL is exhausted and yet she dances against her will: a string puppet.

THIS GIRL (erratic)

The diagnosis is clear; it is four times more likely to result in diagnosable PTSD than combat! The war on the body! And upon survival? We are not veterans, we are not honorable or Fighting The Good Fight. Who said that?

MANNEQUIN SITUATIONSHIP

I think it was Rebecca Solnit-

CONTROL (THAT GIRL)

Slow down

THIS GIRL

Will I die in battle trying to write about the war?

THIS GIRL stops dancing. Just like Olimpia:her mechanical body housing the only humanness she ever had. The DIRECTOR gets up from his chair, gathers his notes and exits through the fire escape.

CONTROL (THAT GIRL)

Don’t you see yourself? Your armour? You are wet earth: soft and wild. You scratch and scratch at open wounds and what? Can you see me? A winged creature

THIS GIRL looks out into the auditorium to find herself sitting, looking back at her. THAT GIRL is wrapped in an armor made of petals. She begins to dance again. This time it’s full of purpose, swing: smashing objects around her: tabletops and lamps, tchotchkes. Numerous stagehands come and dismantle the set while THIS GIRL dances. The fabric breaks. The house lights come on. The audience (if there were any) get up and leave. The curtain draws and still: she dances.

R R

You need to stop pumping your body full of toxic, artificial hormones! Those pills cause cancer and blood clots and infertility, you know. And the doctor who prescribed them, he doesn’t really care about your health. Wasn’t it awful, how he dismissed your concerns? And do you know how much money he takes from Big Pharma?

The medicine you need is food. Eat for your cycle. Try pilates. Heal your hormones. Find your divine feminine energy the government doesn’t want you to tap into. Track your ovulation, and for the love of God, don’t vaccinate the happy little accident you wind up stuck at home with after ditching your IUD. Isn’t having a family just so much more fulfilling than a stressful career that sends your cortisol through the roof? Best leave that to our husbands so we can stay home with the kids like mother nature clearly intended - don’t question it, it’s just biology!

Oh dear, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Don’t you just feel fabulous coming off birth control? ***

The birth control pill poses a dilemma for the modern feminist movement.

On the one hand, its invention and proliferation was nothing short of revolutionary. The pill gave women unprecedented levels of bodily autonomy, and the right of women to control their own fertility was soon understood as an essential precondition to feminist liberation.

However, the pill has also become a signifier of medical misogyny and broader feminist opposition to the patriarchal and profit-driven medical establishment. It’s often prescribed as a cure-all for any condition female-bodied patients present with by (often male) doctors who dismiss the severity and legitimacy of their concerns. It also carries with it a plethora of side effects ranging from depressive episodes to weight gain to sporadic bleeding to headaches to sore breasts.

And so we arrive at an inconvenient crossroad. The pill has been undoubtedly good for feminist liberation as a mechanism by which women could regain control of their reproductive and sexual labour and fight back against exploitation. However, its impacts are far more complex for women as individuals navigating a healthcare system that repeatedly and painfully fails them.

It’s because of this convoluted legacy that the feminist movement often fails to deliver a coherent critique of the pill. Especially in a world where abortion access is increasingly under attack in a global nose dive back into the pits of social conservatism, why would you want to risk deterring people from taking birth control when their lives are quite literally on the line?

However, such an uncritical, hard line is perhaps an unstrategic one, for the reason that it requires the feminist movement to ask millions of the people it purports to represent to deny their own (frequently negative and sometimes traumatic) lived experiences. Not only does this cause people to disengage because they feel excluded and contradicted, but it leaves open the opportunity for criticism of hormonal contraception to be co-opted by the right. And this is precisely what has happened.

If the algorithm has reason to believe you’re in possession of a uterus, odds are you’ve probably come across videos from ‘natural’, ‘crunchy’ or ‘clean living’ influencers. They’re probably wealthy, conventionally attractive white women with designer homes, and preach the benefits of living free from the ills of modernity, like synthetic hormones and pasteurised milk.

These accounts centre their content around improving women’s health, and sometimes they do give helpful advice. Eating unprocessed, whole foods, watching your stress levels and taking pilates classes are probably very good for your health. But, mixed into the wheat there

is inevitably chaff. And boy is there a lot of it. These creators tend to be vehemently opposed to all forms of hormonal birth control on the basis that it has undesirable side effects. And while they’re able to effectively identify a problem - that women frequently take the pill and feel badthey dangerously misdiagnose its cause.

According to the narratives crunchy influencers promulgate, the pill’s negative side effects are not due to the medical research gap that sees women’s health conditions marginalised and under-researched, but rather due to its artificiality.

This is problematic for a few reasons. The first is that it’s analytically lazy and intellectually dishonest to suggest that for something to be good it must be natural. In fact, some unnatural things seem quite good. Like sewage systems, traffic lights or the hit 1997 album “Eternal Nightcap” by The Whitlams. And some natural things are uncontroversially awful. Like cancer, or the sepsis that would infect a broken leg without medical intervention.

Secondly, and more importantly, it’s dangerous because it fosters a fear of conventional medicine, for that too is unnatural. Not only can this deter women from taking the contraceptive pill when it could be in their best interests to do so, but it also demonises other life saving medical interventions responsible for high standards of health in places where they’ve been widely adopted. Vaccination against preventable diseases, pasteurised milk that’s treated to kill potentially deadly bacteria, chemical sunscreens that reduce the risk of skin cancer - all of these treatments are subject to frequent and deeply unscientific fearmongering.

However, the denigration of the contraceptive pill by the ‘crunchy’ movement is only partially explained by their devotion to the natural. Criticism of the pill slots into a second broader theme that is present in a lot of ‘crunchy’ content - a conspiratorial distrust of authority - because it’s a product of Big Pharma.

While not all ‘crunchy’ content ventures into this rhetorical and ideological similarity to the far right, much of it does. It’s a particularly predatory strategy, as it preys on the very real fears women have of being mistreated by doctors and the medical establishment while isolating them in conservative echo chambers that frequently intersect with the far right. In this sense, it’s a potent breeding ground for radicalisation. The ‘organic’ and ‘natural’ quickly becomes the ‘pure’ and ‘traditional’, and disillusionment with misogynistic doctors is often replaced with conspiracy theories that undermine trust in all established knowledge.

The ‘trad wife’ movement encapsulates a worrying end point to this pipeline. Influencers like Nara Smith and Hannah Neeleman are aesthetic endorsements of traditional gender roles - stay at home mothers who are perfectly satisfied with their perfect children and entirely devoted to their husbands. Always implicitly, and often explicitly, this content endorses a condition of dependency manufactured by conformance to traditional feminine roles. Any woman who wasn’t also making a living broadcasting this lifestyle on social media would be completely reliant on her husband and devoid of any capacity to easily become independent due to her lack of income, education and resumé.

However, the misogyny and bigotry doesn’t stop there. These women tend to also espouse right wing and reactionary attitudes towards LGBTQIA+ issues, are proudly anti-feminist and promulgate dangerous conspiracy theories about government overreach that undermine democratic infrastructure.

The discourse surrounding the birth control pill is, like most social issues, complicated. However it’s abundantly clear that the feminist movement can’t afford to be derailed by its failure to engage with the material reality of millions of women. Denying the negative experiences of women who have taken the pill in furtherance of a larger political project is not only devoid of compassion, but also deeply unstrategic. You need only look at how the movement is haemorrhaging political capital to the far right when it comes to women’s health. We must advocate for the importance of universal access to discreet contraception like the pill while simultaneously validating the pain sometimes caused by its prescription. Better training for doctors, comprehensive research into women’s health conditions and increased funding for their treatment must become mainstays on the feminist agenda, for the position right now is untenable.

Since the State of Israel’s “establishment” in the 1948 Nakba, it has remained one of the only countries in the world to mandate conscription for women. Eligible women are conscripted at the age of 18 to serve for 24 months alongside their male counterparts, and are entitled to serve in almost all combat roles.

This is often framed through a lens of “female empowerment,” with Israeli news websites boasting an ever increasing number of articles about record numbers of enlistment of women in combat roles, celebrations of all-women squadrons and first-inhistory promotions to high level commander roles. The IDF website posts articles addressing how they are tackling gender issues within the military. Archives recount the journey to equality as one marked by all the typical battles of women in certain industries: legal battles and high court challenges, introductions of quotas, breaking the glass ceiling, and so on. The potentials of social media have also been realised, with accounts like GirlsDefense and GunWaifu posting over-edited, carefully posed photos of young women in Israeli military uniforms, using sex alongside liberal visions of female empowerment to sell the myth of Israel to the world.

All of these serve an essential narrative that is necessary for the normalisation of Israel and, to a greater extent, all settler-colonial projects; that it is a progressive,

modern, democratic state, and that Palestinians in turn are backwards and oppressive to women. In order to justify the elimination of Palestinians, it is essential for Israel to erase the Palestinian identity by generically referring to Palestinians as ‘Arabs’, using racist stereotypes to turn Palestinians into a monolithic threat against social progress.

This “purplewashing,” i.e. nations weaponising feminist rhetoric and a facade of care for women’s rights to disguise their harmful and discriminatory practices, has been central to Western interference in the Middle East for years. For Israel, the inclusion of women in the military is presented as a step toward inclusion and equality, when in reality, it serves only to boost Israel’s military capabilities, and in turn oppress Palestinians further.

Purplewashing of war is not a new phenomenon. Greenburg (2023) traces this history in the role of the US in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, documenting how female soldiers were often sent in to perform humanitarian and outreach work, building schools and hospitals in order to garner support for the US occupation. During the Iraq war George Bush openly spoke about how his war was essential to the rights and freedoms of women in Iraq. To them, the only solution to the diagnosed problem is military intervention.

Naber and Zaatari (2014) pick up a similar argument, noting that women’s, and increasingly queer rights are at the epicentre of discourse surrounding Israeli and US intervention in Palestine. They argue that Palestine is seen as a centre of terrorism, with women and queer people requiring liberation from these oppressions by heroic soldiers, when ultimately this interventionist strategy is itself responsible for halting social progress. The hypocrisy becomes cyclical. Israel creates the conditions that halt social progress, then justifies its further attacks and violence on Palestinians by the fact that they have not made the social progress that Israel has prevented them from making in the first place.

This is an incredibly flawed vision for “women’s liberation” for several reasons, primarily because it

Khalida Jarrar, Palestinian politician recently released from Israeli “administrative detention.” She was held in inhumane conditions without trial.

ignores the suffering and activism of women within Palestine and robs them entirely of their agency. It falsely erases the role of Palestinian women in their own liberation, instead painting them as either sitting around and passively waiting for freedom to come, or generically labelling them as terrorists. It also blames the conditions of Palestinian society on Palestinians who have been suffering under constant violence and occupation, ultimately suggesting that militarism is somehow the path to liberation, instead of its main obstacle.

It creates a situation in which Israel claims to be championing women’s rights in Israeli society, when in reality they are creating some of the most uniquely devastating conditions for women we’ve ever seen. Whilst Israel boasts its record numbers of women in combat roles, over the course of the genocide 67 children a day are being killed in Gaza, women are using strips of tents in place of pads and tampons, 60,000 pregnant women are facing the prospect of giving birth with no hospitals, medication or clean water, and miscarriages have increased by 300%.

In light of this, it is impossible to justify this narrative of female empowerment. It is a lie to sell the state of Israel to the world; to justify support from Western nations and downplay the devastation of militarisation through narratives of security and counterterrorism, and convince the world that not only is it okay to occupy and ethnically cleanse an entire population for 75+ years; it’s actually empowering!

The hypocrisy becomes all the more apparent when trawling through the archives or the “Women in the IDF” playlist on the IDF’s YouTube channel. Such sites proclaim the milestone that the 2006 invasion of Lebanon was the first time since the 1948 “war” that women participated in combat roles alongside men, conveniently ignoring the thousands of casualties and refugee crises caused by the Nakba and subsequent occupations and invasions. They use nebulous terms of “fighting terrorists” and “protecting national security” to obscure that these achievements are steeped in blood.

Israeli scholarship attempts to find a feminist justification for engagement with the IDF by positing various liberal feminist positions on militarism: 1. that women are entitled to serve in the same military and combat roles in order to achieve full equality within Israeli society, 2. that women have the power to alter the masculine culture of the military by joining as full participants, or 3. the gender essentialist argument that women joining an inherently masculine and patriarchal institution such as the military contradicts their “inherent” feminine virtues of nurturing, peacemaking and life protection.

All these positions, much like the “female empowerment” narrative, are fundamentally meaningless because they still legitimise the IDF as a foundational element of the state of Israel, and to a greater extent, militarisation as a path to liberation. Thus, even beyond the context of Israel, feminist discourse surrounding the role of women in the military, particularly Western militaries, will always be somewhat futile as it fails to envision a world beyond militarism. Without an anti-imperialist and anti-colonial position, “feminist” discourse will always fall short because it pretends to contemplate how the military can create a better world for women, when in reality the only question it answers is to what extent should women be complicit in genocide and war crimes?

Purplewashing is at its core an attempt to legitimise and reform a genocidal institution from within. It creates a two-tiered version of feminism, in which Israeli women are allowed to have aspirations of gender equality and equal citizenship, whilst Palestinian women must constantly fight for their survival. There can be no semblance of gender equality in an apartheid state built on racism, genocide and violence, and true feminist liberation for Palestinian women can never coexist with the IDF.

On October 30th 1920, an estimated group of thirteen to twenty-six men and women from different socialist and labour-aligned groups across Australia gathered at the Australian Socialist Hall in Liverpool Street, Sydney, at the then headquarters of the Australian Socialist Party. Inspired by the success of the Bolshevik-led Russian Revolution of 1917, this small group of “restless, cosmopolitan, resourceful (and) impatient” (Macintyre, 1999) revolutionaries had been aiming for some time to establish a Communist Party in Australia (known as the CPA). It was this group of revolutionaries who aimed to establish a project that would “bring about the unified action of all who stand for the emancipation of the working-class by revolutionary action” (Macintyre, 1999). Though the party’s founding congress consisted predominantly of men, notable women who attended the congress were British-born suffragist Adela Pankuhurst, novelist Katharine Susannah Prichard, lawyer Christian Jollie Smith, and vocal anticonscriptionist Alice Marcia Reardon.

The question of women’s involvement and role within the CPA is a long and often contradictory history. Women played a large role within the Party upon its foundation, but also made up only 12 to 13 percent of the party’s very small membership. In Russia, the Bolsehviks engaged practically with the ‘women’s question’, and implemented several revolutionary social and political reforms in Russia that were far more advanced than any other country at the time - i.e the 1917 decree that granted women legal equality with men. This included the right for women to hold office and the right to vote. In Australia, the CPA also concerned themselves with the question of the emancipation of women, but saw no use in engaging in “separatist” movements that were detrimental to the CPA’s objectives in uniting the workingclass. Instead, women of the Party had the task of organising “special work among women,” who would carry the message of the Party to “women workers” and the wives of male factory workers. Later, several women of the party established a women’s central committee, known as the Militant Women’s Group. This group would later go on to organise the first International Women’s Day public meeting in 1928, and involved themselves in several workers’ disputes in the mining and timber industries. In 1927, The MWG published a pamphlet titled “Woman’s Road to Freedom.” Quoting German Marxist and women’s activist Clara Zetkin, the pamphlet urged women to become involved with the class-struggle alongside their male comrades for the overthrow of capitalism.

By 1929, the increasing Stalinisation of the CPA was well underway with the emergence of Soviet hardliners like J.B Miles and Lance Sharkey. The Party then decided that the efforts of the MWG could be carried on in the ‘Workers International Relief (the WIR), where women of the MWG could meet the needs of women and children involved with the WIR. From this period onwards, the CPA’s definition of ‘work amongst women’ was moulded into the Stalinist archetype of what a woman’s role should be within the Communist Party. This was a traditional sexist stereotype that was already largely normalised within Australian society, which confined women to the role of wife and mother. The

implementation of these attitudes that defined the role of women in the CPA until the mid-1960s allowed the Party to develop dual political and social practices with women. Some women of the Party were encouraged to maintain the role of wife and mother, while other Party women who engaged in official positions, such as being an organiser, were told not to have children.