HONI SOIT

Unveiling the Deep Is This All That Will Be Left of Me? Read the World

Unveiling the Deep Is This All That Will Be Left of Me? Read the World

Honi Soit operates and publishes on Gadigal land of the Eora nation. We work and produce this publication on stolen land where sovereignty was never ceded. The University of Sydney is a colonial institution. Honi Soit is a publication that prioritises the voices of those who challenge colonial rhetorics. We strive to continue its legacy as a radical left-wing newspaper providing students with a unique opportunity to express their diverse voices and counter the biases of mainstream media.

Books of the world

Crosses & white flags

Islam’s Golden Age

Deep sea diving

Bathroom graffiti

Existentialist travel

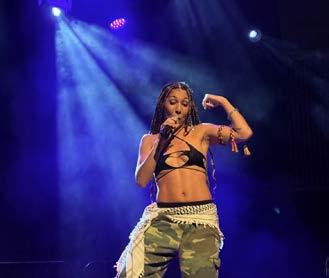

Mardi Gras

SRC Casework

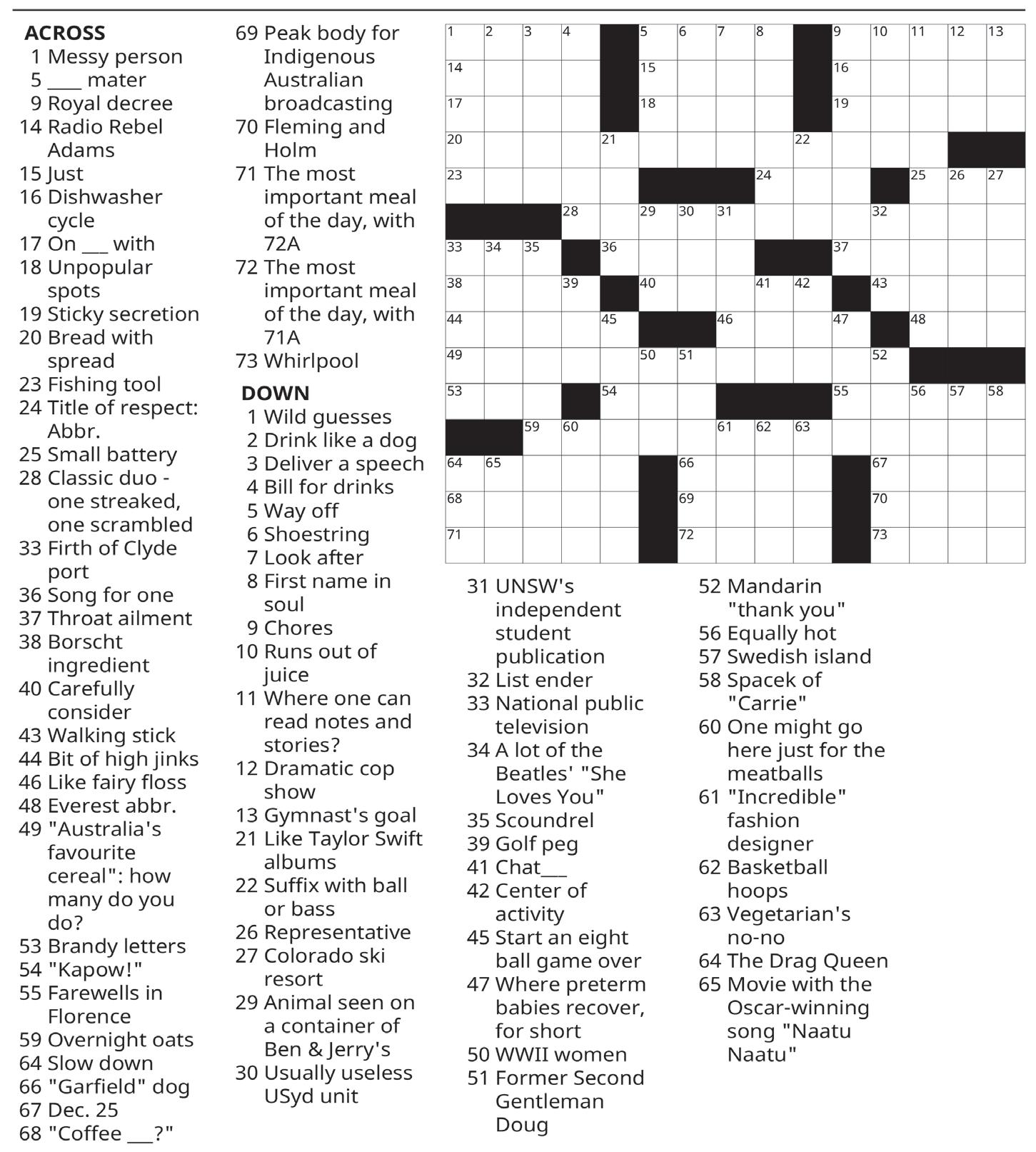

Puzzles

This edition is dedicated to Winnie Huang, who asked me a while ago to dedicate my first book to her. Winnie, I hope this is close enough; but if I write a novel anytime soon, I’ll keep you in mind.

The theme for this edition is Flags. In essence, a flag is a large rectangular piece of cloth, but for this rectangle, wars have been waged, blood has been shed, communities have been put together and torn apart, and identities have been forged and remade anew. We use them to drive people apart, and to bring people together. Why do flags

mean so much to us? This is the question that fuels this edition, and each of our wonderful reporters have a different answer. Within these pages, we’ve got Avin Dabiri musing on the meaning of the white flag, Akanksha Agarwal taking us on a journey through her past homes, Pia Curran leading us through the labyrinth of USyd’s bathroom graffiti, Eliza Crossley giving us a much-needed review of hot cross buns, and Ananya Thirumalai debating the dilemna of the lesbian flag. Plus my Mardi Gras coverage: you will not believe how chaotic it was.

The Butterfly Effect, Akanksha Agarwal

This piece is a meditation on the role that flags, places, ideas, and movements play in our individual metamorphosis, and ultimately, our collective metamorphosis. The butterfly represents healing, growth, and all the flags represent our shared humanity despite differences. The inverted halfsplit butterfly signifies the triumph of harmony, and justice regardless of the environment. While we grapple with a warming climate, wars around

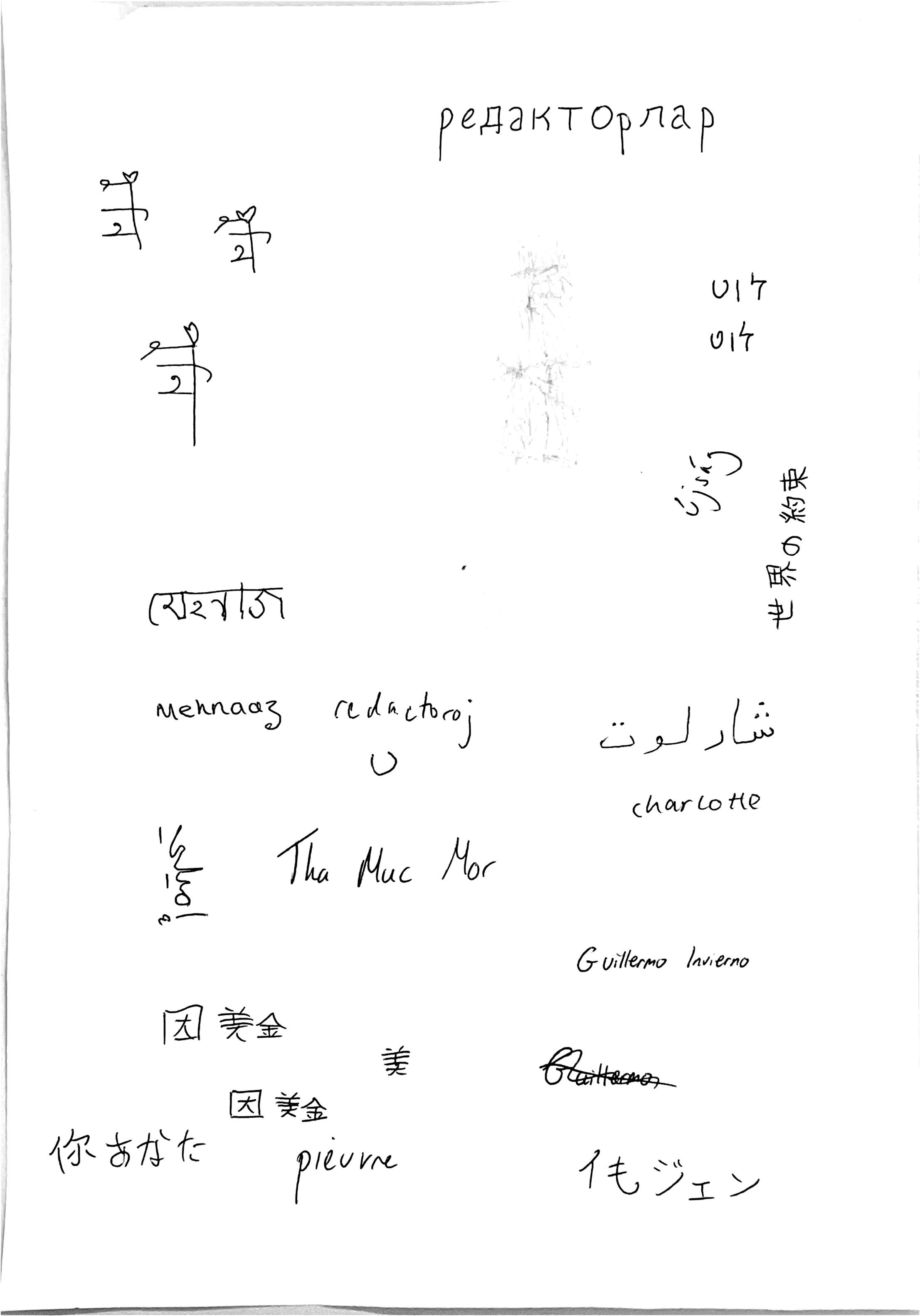

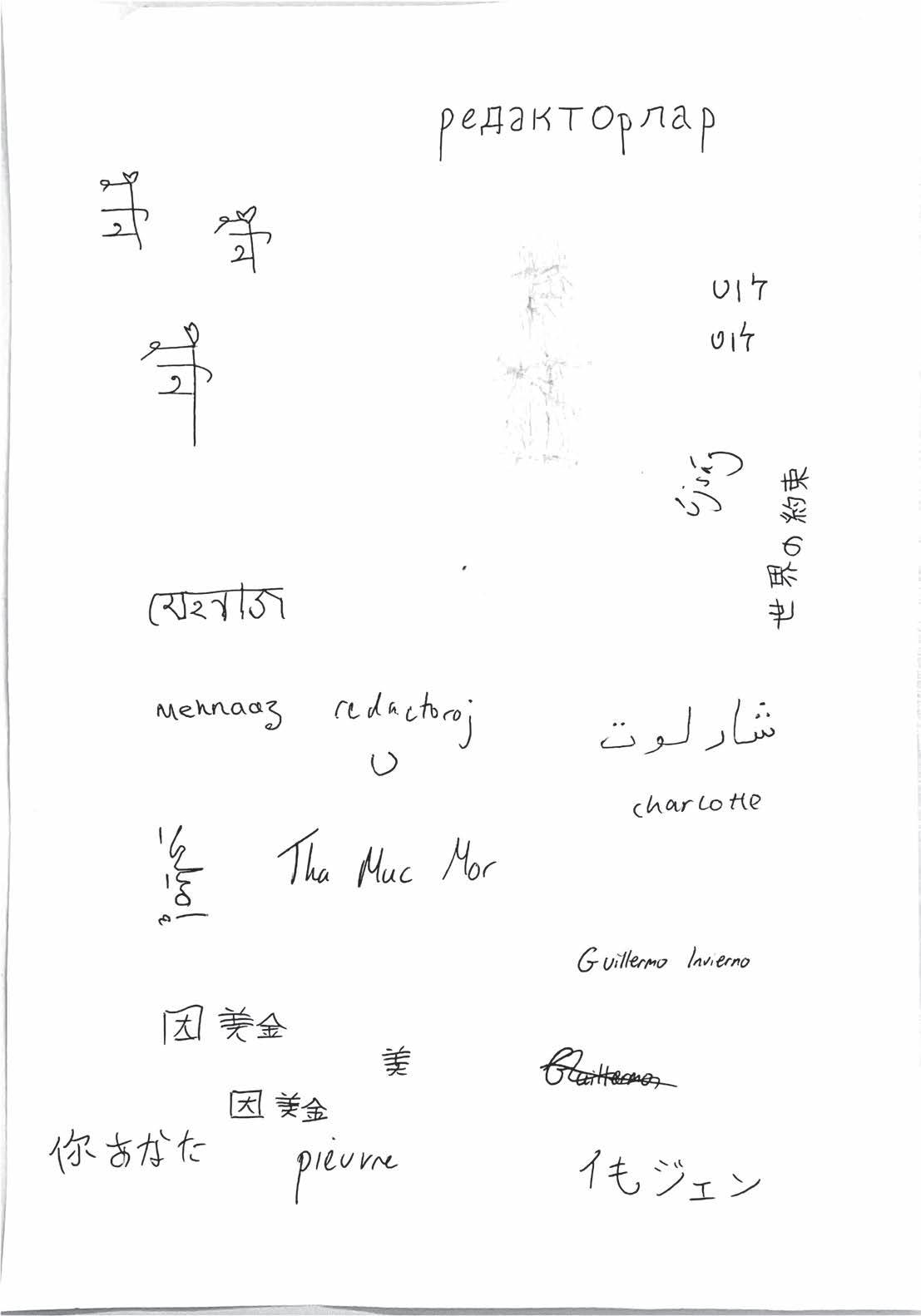

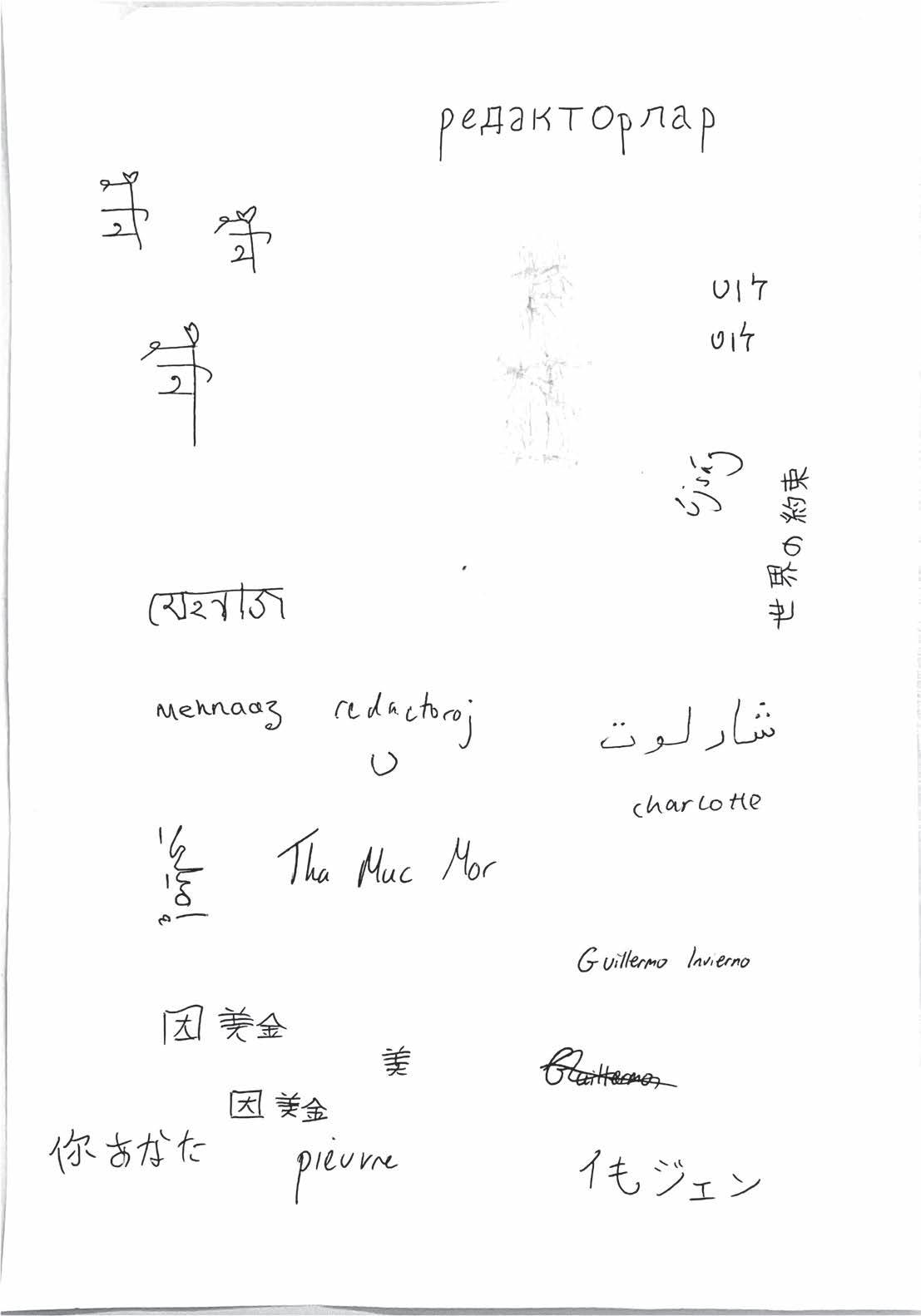

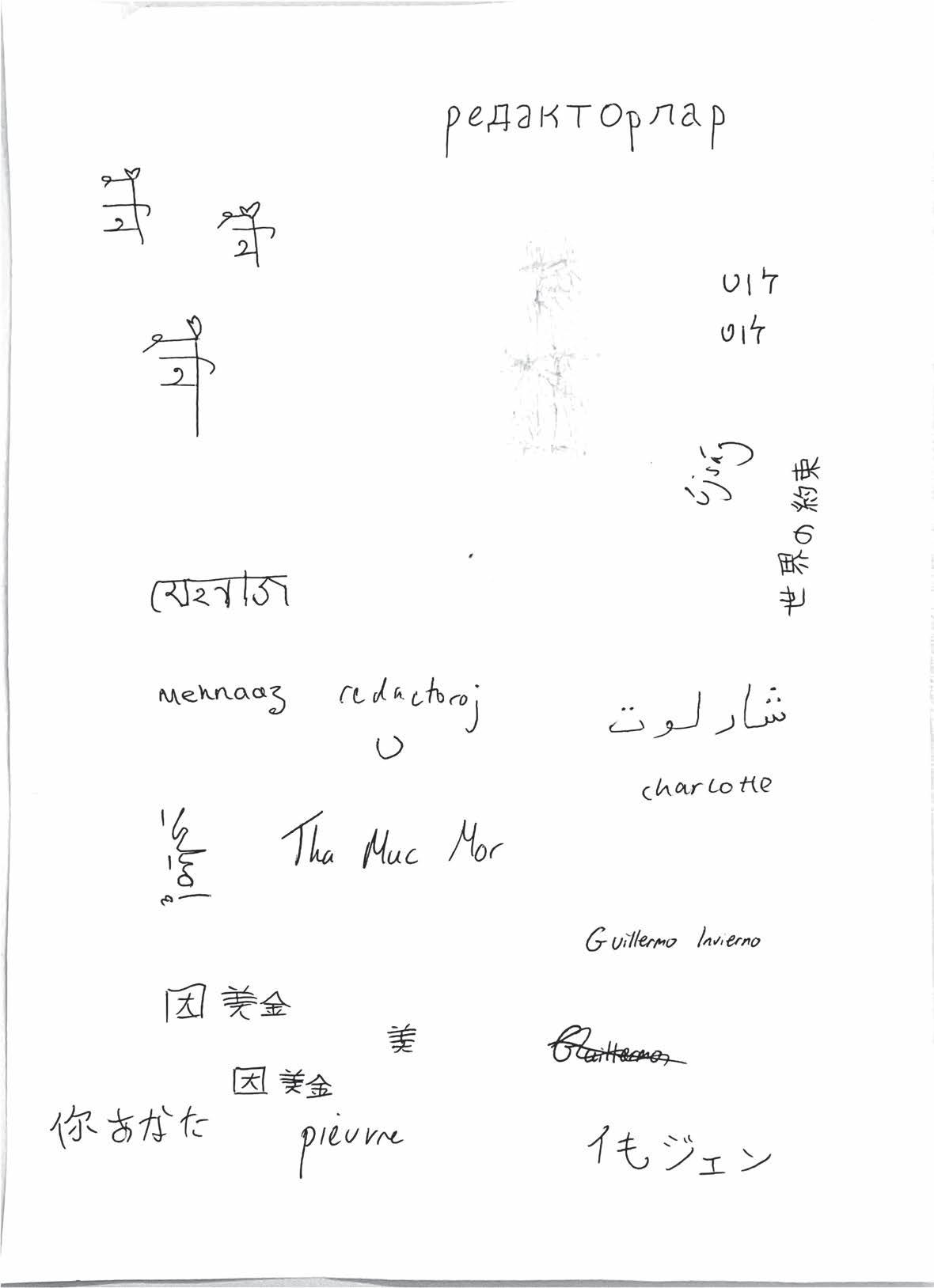

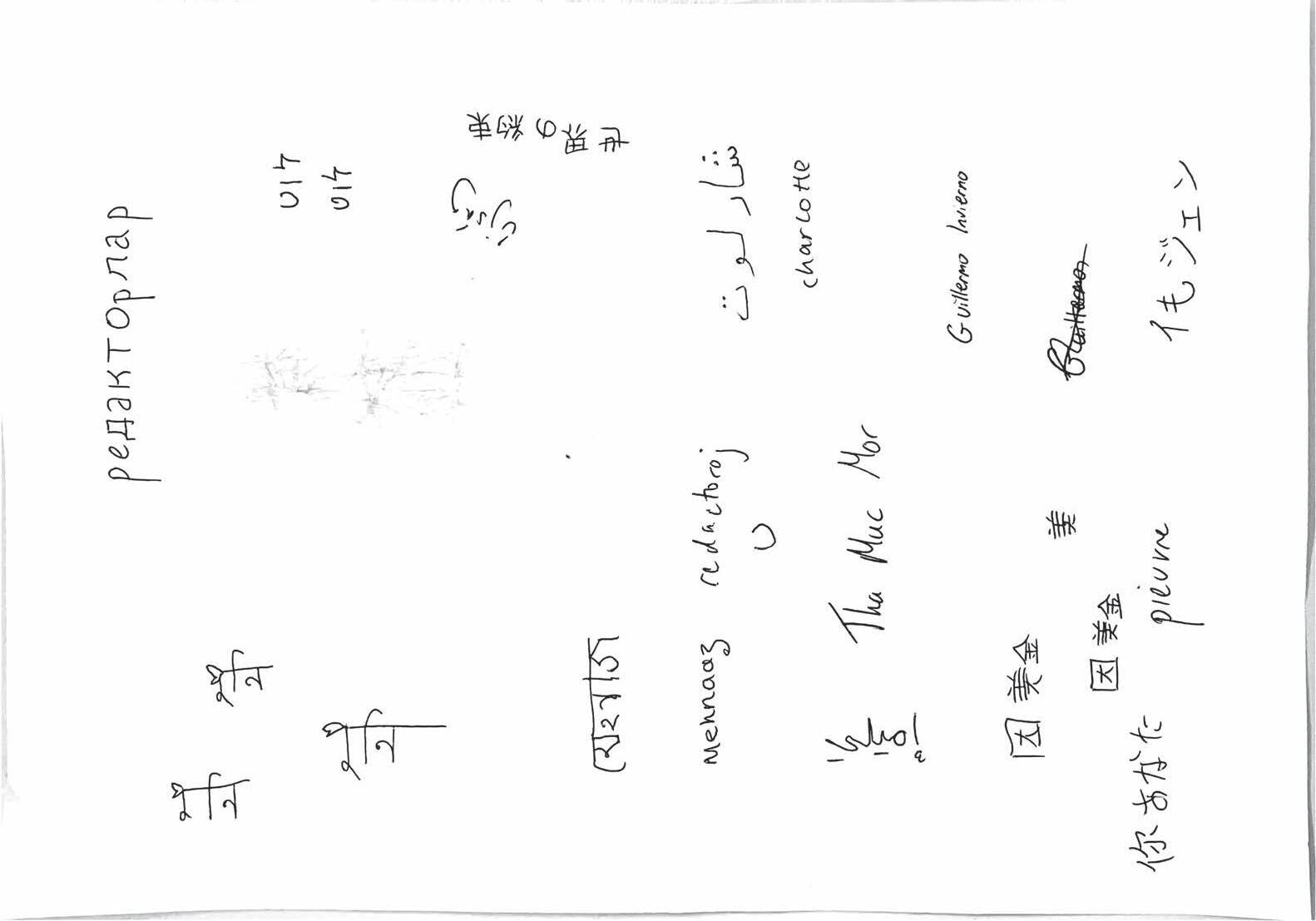

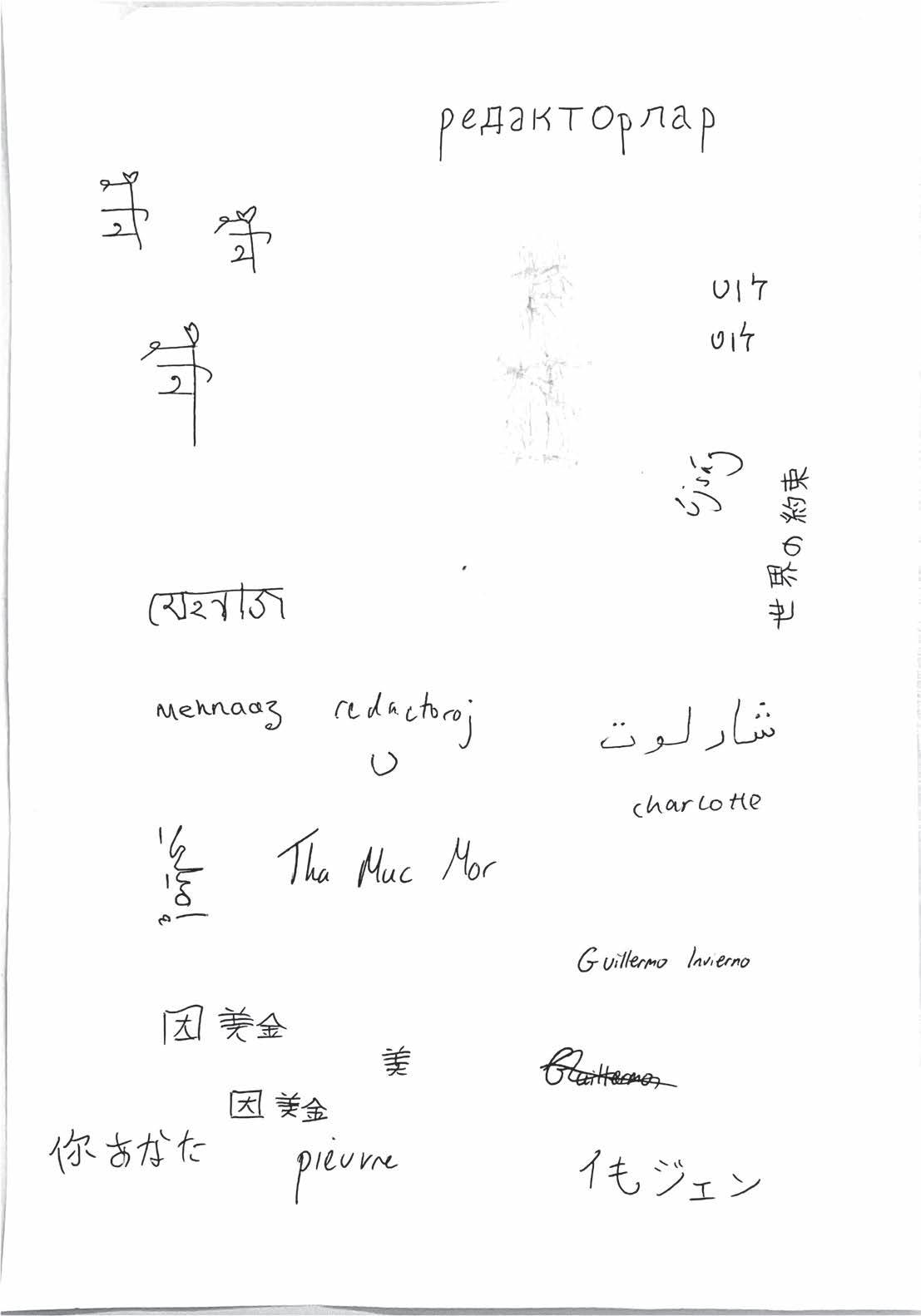

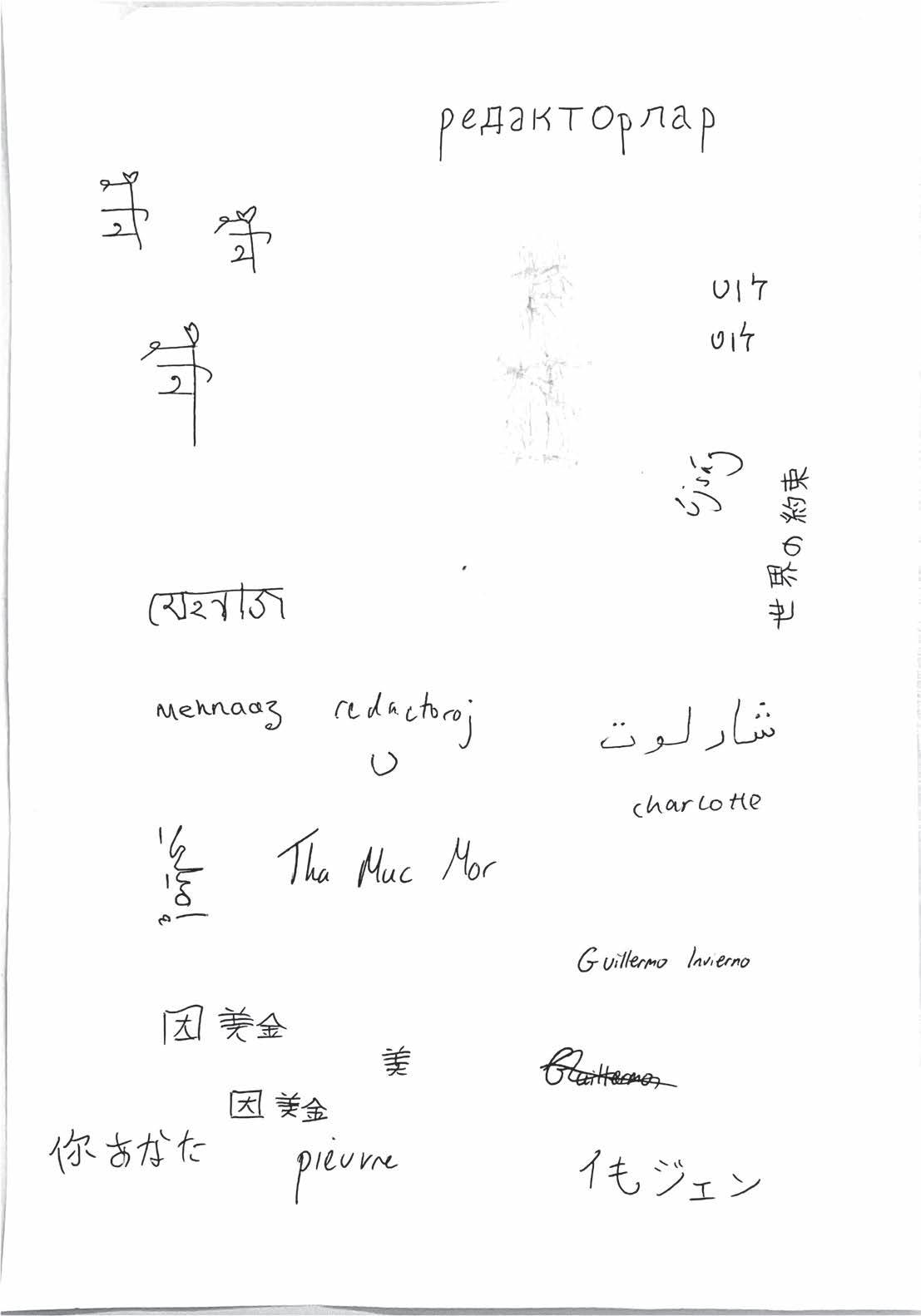

Editor-in-Chief

Imogen Sabey

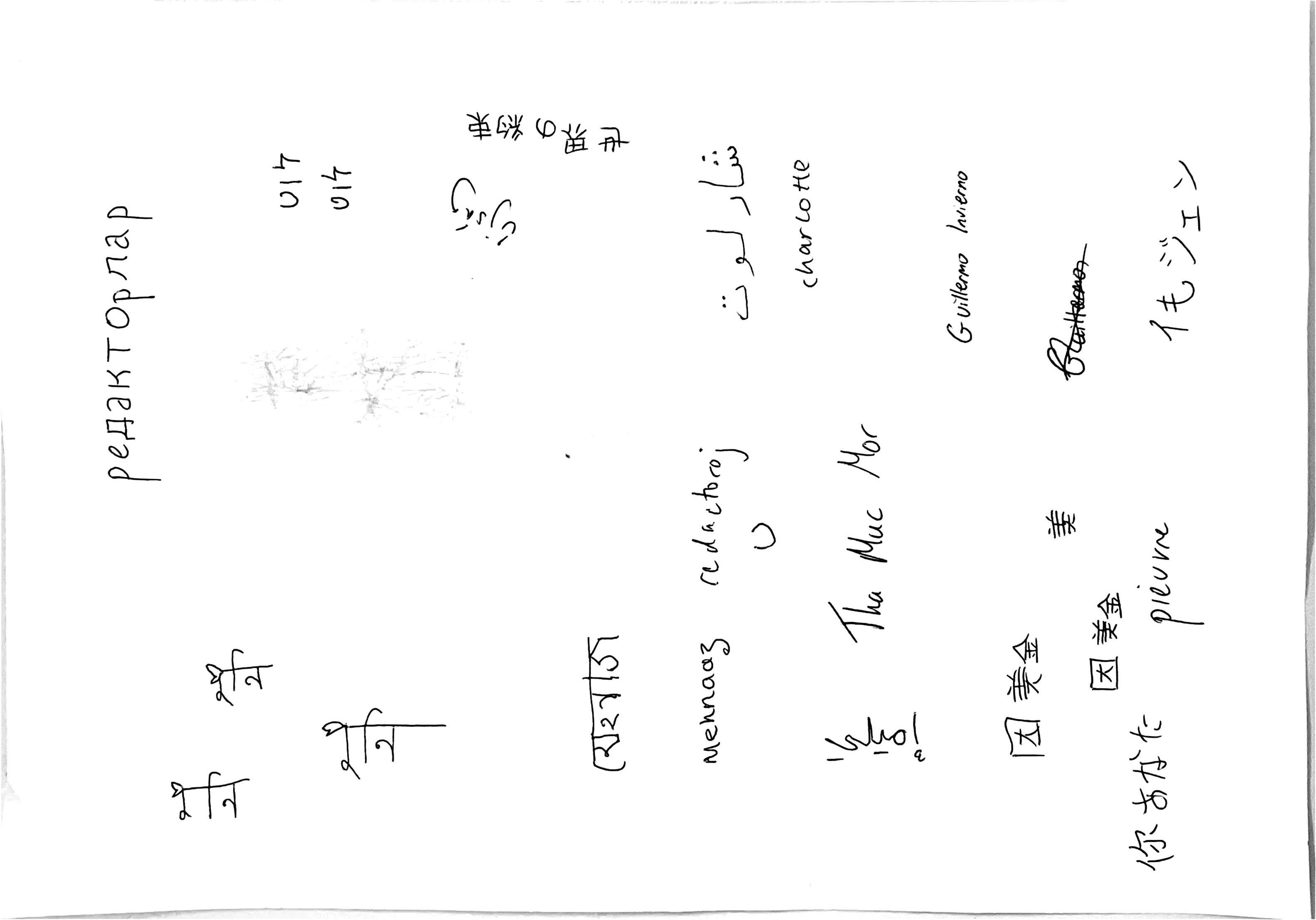

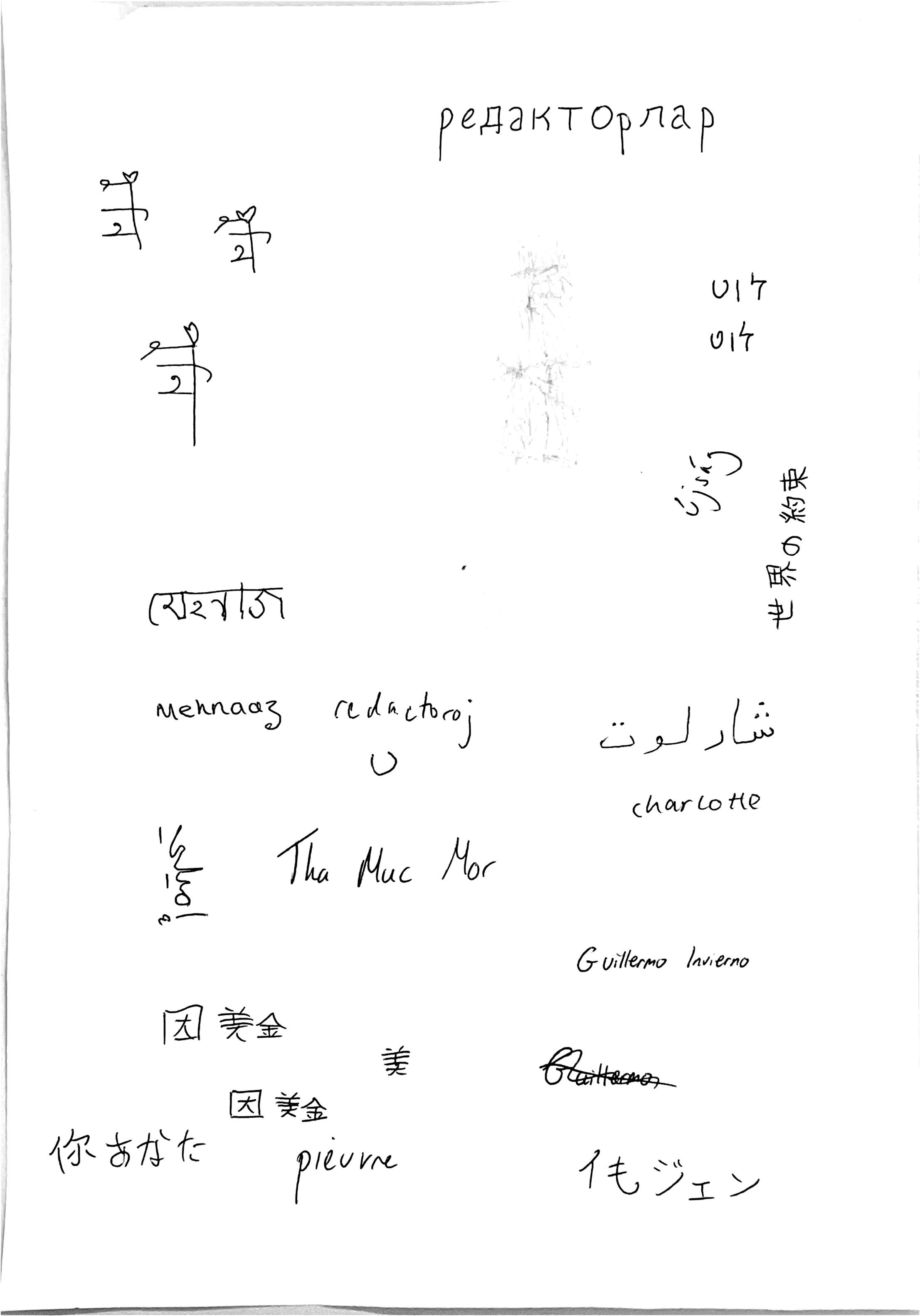

Editors

Purny Ahmed, Emilie Garcia-Dolnik, Mehnaaz Hossain, Annabel Li, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Lotte Weber, William Winter, Victor Zhang

Way more sprinting there than your traditional Mardi Gras.

I’d like to say a special thank you to my reporters, who did a fantastic job in this edition. And one more thank you to Victor Zhang, formerly part of my reporter group and now anointed the 10th editor of Honi Welcome to the team, Victor! I hope you enjoy this week’s edition of Honi, and that it leaves a lingering impression of the colours of the world.

Love, Imogen

the world, and the disregard for human rights, the butterfly reminds us of our unanimous strength in the face of adversity. I’ve tried to move beyond notions of flags as merely symbols of geographical patriotism to movements such as the feminist flag to represent the power of flags in advocating for change. Ultimately, the hope is to celebrate differences, and find an intersectional space of unity.

Akanksha Agarwal, Chiara Arata, Sath Balasuriya, Maddy Burland, Pia Curran, Avin Dabiri, Ava Edwards, Kuyili Karthik, Hamna Khan, Kiah Nanavati, Emily O’Brien, Marc Paniza, Grace Street, Tanish Tanjil, Ananya Thirumalai, Sebastien Tuzilovic, Victor Zhang

Akanksha Agarwal, Purny Ahmed, Emilie Garcia-Dolnik, Mehnaaz Hossain, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Tanish Tanjil, Lotte Weber, Will Winter, Victor Zhang

accuracy

or

Dear Honi Soit,

The University must take seriously the insidious threat posed to academia by artificial intelligence. This is not a potential danger which may rear its ugly, humanoid head in the future; it is already here, and it is straight out of dystopia.

Allow me to illustrate this. Today, a student next to me in a tutorial pasted an activity prompt into a translator, and then into DeepSeek. Unfortunately, classrooms illustrate how artificial intelligence has become a go-to tool for students who lack the necessary English proficiency to engage with subject matter, in a practice that is destructive both for the student and for the standard of education at the university. These students are paying much and learning nothing.

Last week, a student sitting next to me in a different class (studying physical education!) likewise directed AI to complete an activity for them.

Allow me to return to Digital Cultures, for which ChatGPT summaries of reading material are now routinely attached to the reading list.

We are supposed to be a university! Where artificial intelligence has infiltrated, the standard of education is now non-existent! I am livid, as every student has the right to be.

I beg of you, our editors, not to for a single edition let this menace evade your watch.

Will Thorpe

I have a full-blown crush on my tutor. I’m talking heart racing, face turning red, completely distracted whenever he’s around. And don’t get me started on his eyes. We get along really well, and he always makes an effort to chat with me about things outside of class. I know there’s a professional boundary while he’s in that role, but he graduates at the end of the year. Would it be weird to add him on social media after the unit ends to test the waters, or should I wait until he’s fully done with uni? And is it totally taboo that I feel this way about him in the first place? I don’t want to make things awkward, but I also don’t want to miss my chance if he might be interested. Any advice?

Academically Thirsty

Girl, don’t do it. With concern, Honey

I FOUND MY MISSING AIRPOD!!!!! Strictly speaking, my mum found it: tucked away behind a stair two floors beneath my room. I don’t know how it managed to end up there, that would’ve required some serious gravitational acrobatics. My mum said she didn’t realise it was anything important and she would have thrown it away if I hadn’t complained so loudly about it going missing. Close one! Thank you for your lovely advice.

Miss Price

Yay! Lesson learned: always complain (loudly). You’re welcome, Honey

Art by Ellie Robertson

National Day of Action for Palestine

Wednesday 26th of March at 12pm

UNSW MTS Presents: The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee

25th–30th of March Studio One Effective Power

Friday 28th of March at 8pm Waywards

Trans Day of Visibility Rally

Sunday 30th of March at 2pm Pride Square

Later in the year... Student Journalism Conference

15th–18th of August at USyd

More details coming soon!

The University of Sydney (USyd) announced on the 17th of March that the 2024 election of the Undergraduate Student Fellow of Senate for 2024-2026 is now void. This declaration was made by the Returning Officer and Governance Officer, Michelle Stanhope.

The reason cited for voiding the election was that Stanhope “was not satisfied with the fairness and integrity of the election process.”

On Tuesday 18th March, a subsequent election was called to re-elect the Undergraduate Fellow position.

According to Stanhope, USyd received “a number of reports and complaints from students which alleged that candidates and/or their supporters had engaged in behaviour expressly forbidden under the Election of Undergraduate or Postgraduate Student Fellow of Senate Guidelines.” The nature of these reports and complaints was not specified.

The election had previously been suspended from the 24th of October 2024, the day voting closed, and had remained in effect until the 17th of March.

The first Senate meeting is scheduled to take place on the 22nd of March. Currently there is no undergraduate student representation planned for this meeting.

Stanhope said that “The University is committed to enabling undergraduate student representation on the University’s Senate hence our immediate action to recall the election. In the interim period, the University is considering opportunities to facilitate student representation and consultation until an Undergraduate Student Fellow can be validly elected.”

A USyd spokesperson said to Honi that “While we are legally constrained in what we can disclose about individual cases, we take these allegations extremely seriously.”

The spokesperson said that the Chancellor was “acutely aware of the concerns regarding undergraduate student representation” and has attempted to ensure representation by requesting a meeting with the Presidents of the SRC and the USU “to discuss the Senate meeting outcomes and themes to ensure meaningful engagement.”

In response to questions about the considerable length of time between the previous election and the new election, the spokesperson said that “We have an obligation… to follow due process and make sure detailed consideration was given to the complaints made regarding behaviour during the election process but we understand the frustration and disappointment of those involved.”

Alex Poirier, one of the candidates in the now-void election, commented “It’s honestly ridiculous that this has taken so long. The voiding of the previous election took 144 days, and this new election will finish on the 13th of May.”

He added, “Multiple candidates, including myself, have felt the voiding and subsequent notice of a new election has become a punishment on honest campaigns, because of the misconduct of others. It seems that the offending candidate will face no repercussions, whilst the others will be forced into a new election, for which they may not have capacity and time.”

Ned Graham, another disappointed candidate, said “A new election punishes those of us who ran good faith

Imogen Sabey reports.

campaigns at considerable personal cost in time and money.”

Graham continued, “The university faces a straightforward decision: if there was misconduct, disqualify the offending candidate(s); if there was not, there is no reason for a new election to be held; if there may have been misconduct, prosecute the cases for and against until the existence of misconduct can be concretely determined.

“The university cannot kowtow to the candidate(s) who offended during the 2024 election and who stand to benefit most from a new election.”

The university commented that “We aren’t able to give a definitive answer as to whether candidates who have allegedly engaged in forbidden behaviour could be permitted to run again as, legally, any qualified person on the undergraduate roll can be nominated for candidacy, and the returning officer has to make a decision at that point as to whether they accept the nomination and confirm the candidate or not; the returning officer can’t pre-judge an application that has not yet been made.”

They added, “We’ve undertaken a preliminary review of how we can best support the fairness and integrity of the election process… The Notice of Election and Nomination Forms have been updated for student Senate elections – including the requirement for a signed TEQSA Fit and Proper Person declaration to be provided to constitute a valid nomination. Additional information regarding the conduct of elections will also be published on the University’s webpage along with a briefing for all candidates with the Returning Officer prior to the ballot.”

At 2:42pm on the 28th of February, the elusive doors to the Cullen meeting room in the Holme Building opened for the ‘public’ session of the University of Sydney Union (USU) Board meeting. The session officially began when Honi Soit entered the room. I’ve never felt more dignified than being referred to as such in the minutes.

USU President Bryson Constable (Liberal) began by informing us of the introduction of four new profile titles in the USU: Ethnocultural (Phan Vu, Independent), Colleges and Student Accomodation (Georgia Zhang, Switchroots), Equity (Sargun Saluja, NSWLS), and First Nations (Ethan Floyd, Independent).

There was a brief discussion on the results of the last survey regarding the USU community’s thoughts on the upcoming incorporation. After including an amendment to the layout of the financial committee to allow a senateappointed director to be appointed to it, the incorporation plan was formally endorsed by the USU Board. Honi is looking forward to the rest of this year’s Board meetings now that the incorporation plan is no longer a discussion, but rather an inevitability.

The next section of the proceedings regarded the electoral committee and election regulations. With the notice of election available on the USU website, it’s important to note that only six positions will be nominated this year, as the USU Board runs on two-year terms. Nominations for Board elections are open from the 17th of March until the 7th of April, with USU elections being held from the 12th of 16th of May.

The next few motions were discussed and moved as part of wholesale amendments to electoral regulations. Firstly, the electoral calendar has been shifted to allow Honi to conduct interviews during the embargoed election period. Yay!

Two other key regulation changes included: all purchases made using USU election funding must be reimbursed

at market price; there is no requirement for one-on-one or small group interactions to be conducted in English, but any larger verbal proceedings or printed materials written in a foreign language must also include an English translation.

Stricter punishments were also brought to the table for individuals who breached any electoral rule changes, to discourage infractions of the policies. Constable often referred to these ‘punishments’ with a sense of almost… glee? It was fascinating to observe Constable’s amusement with the idea of punishing individuals who supposedly ‘break’ the electoral rules, especially since the amendments which have been introduced are, as pointed out by an anonymous Board member, predominantly due to the actions of left-wing and ESL nominees for the Board from 2024.

A point of contention in the meeting was on an amendment to stop campaigners handing out non-USU flyers while wearing USU T-shirts. The proposal would see two regulations introduced: campaigning can only be conducted by individuals wearing USU T-shirts, and individuals in USU T-shirts are only able to hand out USU campaign materials.

Vice President Ben Hines (Independent) was the first to raise issue with this amendment, suggesting that it hinders the versatility of a candidate’s ways of campaigning, and would discourage people to join campaigns for an election which historically receives less attention on campus than that of the SRC.

Saluja supported the motion, suggesting that it would make it easier to identify when campaigners violate electoral rules such as illegally campaigning on residential sites. After some more discussion, and Constable suggesting that the cost of buying T-shirts is negligible for a $700 campaign budget provided by the USU, it is agreed to table this specific amendment until a better solution can be reached. All other motions were carried.

Will Winter reports.

Next was the financial report. For the 2024-2025 financial year, the USU reported a surplus of $350,000, as well as an unspecified surplus in January due to the high influx of Manning Bar’s events. With a recent turn towards utilising more of the outside physical space in Manning (thus allowing more bodies to flow, more tickets to sell, and more drinks to be bought), a planned deficit in January was avoided, which begs the question as to how necessary the price increases at USU outlets this year truly was.

The other reports were all taken as read, but there were three clear highlights to the President’s report. Firstly, Constable noted that this year’s Welcome Fest was the biggest and best Welcome Fest yet. When asked by Honi later in the meeting about how they’d attribute this success, Constable pinpointed the “amount of clubs and sponsors, and the breadth of space” which was utilised. Secondly, it was mentioned that a revised rubric for applying to start a USU club was in the works. This would hopefully streamline the process and allow interested individuals to understand the metrics by which to demonstrate the unique aspects of their proposed clubs. Thirdly, after attempting to pass the chair from Hines back to Constable (a procedural necessity for Constable to deliver his report), Hines quipped “Can I get a seconder to move chair back to Bryson? I know we always struggle with this”, which was met with several seconds of laughter, and then an awkward silence.

Read full article online.

On Thursday 13th March, the Chief Executive Officer of the University of Newcastle Student Association (UNSA), in an email to their Board and Student Representatives’ Council, attempted to remove the democratically elected president Matthew Jeffrey from office.

The student union at the University of Newcastle operates with a joint structure of service provision and representation. The elected president is both the president of the Students’ Representative Council (SRC) and the chairperson of the Board of Directors.

In the email, UNSA CEO Mark Trevaskis notes “decisions made by the University of Newcastle” around Jeffrey’s studies. Trevaskis cites Section 36.2 of their constitution and the SRC terms of reference as the basis for “steps [taken] to remove Matt from his position as SRC President and UNSA Chairperson effective immediately.”

The Constitution of UNSA is the governing document of the organisation as lodged with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC).

Section 36.2 of the UNSA constitution states that “A student is not eligible to stand for election as a director of the Company or to hold a position as a director of the Company if they have either: (a) a finding of non-academic misconduct upheld against them; or (b) a

finding of academic misconduct upheld against them.”

Honi understands that the president’s academic progression has been affected and is under review by the University of Newcastle. Section 36.2 refers to “academic misconduct” which according to their website pertains to plagiarism and academic honesty and is unrelated to academic progression.

The UNSA Constitution states in Section 42.4 that “directors and auditors may only be removed by a Voting Members’ resolution at a General Meeting.”

No such meeting has occurred as indicated in an email that the CEO sent on the 12th of March where he asked for the resignation of the president.

Grace Street, General Secretary of the University of Sydney SRC, provided comment on the situation stating “it is extremely alarming to see the attempt to silently remove Matthew from his role as SRC President using sloppily applied bureaucratic measures.”

“This is not just a case of poor governance from the unelected CEO, but it is also an attack on student unionism and democratic elections that fits into a larger global trend clamping down on dissenters and student protestors.”

The Australian Salaried Medical Officers’ Federation (ASMOF) is demanding urgent action from the NSW Government to address the crisis of severe understaffing in mental health services.

For over a decade, the NSW public health system has been struggling to recruit and retain psychiatrists. NSW had 140 vacancies before the mass resignation in January 2025, when 200 public hospital psychiatrists resigned in protest as a result of the government’s inaction in addressing the crisis.

The matter went to arbitration at the NSW Industrial Relations Commission on 17th March.

As part of the arbitration proceedings, ASMOF is calling on the Minns Government to act immediately to fix the crisis by meeting the following conditions:

- Urgently recruiting additional psychiatrists to fill vacancies

- Fully funding training and registration fees to attract new donors

- Providing a 25% pay increase for psychiatrists to stem the flow of doctors leaving NSW

Purny Ahmed reports.

- Establishing a formal Psychiatry Workforce Committee to oversee staffing and recruitment

- Implement a structured dispute resolution process to improve working conditions

ASMOF President Dr. Nick Spooner has warned that the government’s refusal to take action puts lives at risk, stating that “[patients are] waiting for days in emergency departments, deteriorating, because there simply aren’t enough psychiatrists left in the system.”

This has caused emergency department delays, bed closures, and dangerous conditions for both patients and staff.

Mental health patients are waiting for up to 90 hours for care that should be available within hours, according to Dr. Spooner.

“The solution to this crisis is not complicated. It’s about valuing psychiatrists, paying them fairly, and ensuring that NSW has enough doctors to provide the care patients deserve.

“The Minns Government has a choice — fix the problem or let the system collapse completely.”

The NSW Industrial Relations Commission arbitration between ASMOF and the NSW Government will occur from 17th to 21st March.

“Syqe, your hands are red”: Students and academics protest Western Sydney University’s research partnership with Israeli firm Syqe

Victor Zhang reports.

On Monday 17th March, students, academics, and activists protested Western Sydney University’s (WSU) National Institute of Complementary Medicine Health Research Institute (NICM) for their research partnership with Israeli medical technology company Syqe.

In a press release from WSU for Palestine, they have raised concerns around Syqe’s support for the Israeli military and said that NICM staff were not informed of Syqe’s military ties.

WSU for Palestine added that staff “were disturbed to learn about this research agreement, some of whom have family in Gaza and Lebanon” and said that concerns raised to NICM management were ignored.

Dr Diana Karamacoska, an academic at NICM, spoke in a personal capacity about her opposition to the Syqe partnership. She spoke for “staff and students with family members in refugee camps in Gaza” and stated that “[by] accepting this research agreement with Syqe and the IDF that it proudly supports, you’ve diminished their voices, identities, trust and hope. It is not safe to be here.”

Liz Tilley, the Greens candidate for Parramatta and alumnus of WSU, said she “was appalled, but wasn’t surprised” to hear of NICM partnering with Syqe amidst the ongoing repression of pro-Palestine voices. She cited Universities Australia’s recent adoption of a definition of antisemitism that conflates antiZionism with antisemitism.

Tilley called for the community to stand up against a university that “wants to align itself with an apartheid state,” to call on our MPs to “sanction Israel and restrict Australian universities from partnering with [Israeli institutions],” and to “demand that our universities are properly funded so they don’t need to be sponsored.”

Cassie from Nurses and Midwives for Palestine called into question

why WSU would create this “disgusting alliance with a corporation that has celebrated its relationship with the Israeli Defense Forces.” She noted the murder and illegal detention of healthcare workers in Palestine.

Cassie also condemned the continuous disregard for Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim voices as a “inhuman, disturbing, and distressing example of othering” which forms “a key factor in all genocides.”

Yehuda, an anti-Zionist Jewish WSU student, prefaced his speech by stating that he was speaking in an individual capacity, and that he would continue to speak “despite their [the Department of Education’s] attempts to silence teachers from speaking out against Palestine.”

He highlighted the parallels between genocides across the world over time, highlighting the ongoing genocide in Palestine and the continued disposession of Indigenous peoples across the world. Yehuda spoke as a descendant of Holocaust survivors that “there is nothing more offensive to me than the fact that we are standing silently amidst a genocide.

“They claim to be working on medicine right here, when, in fact, they’re easing the conscience of war criminals. And they drop bombs on schools when [sic] claiming it’s too expensive to fund our schools and education systems.”

Sign the petition calling for WSU to cut ties with Syqe.

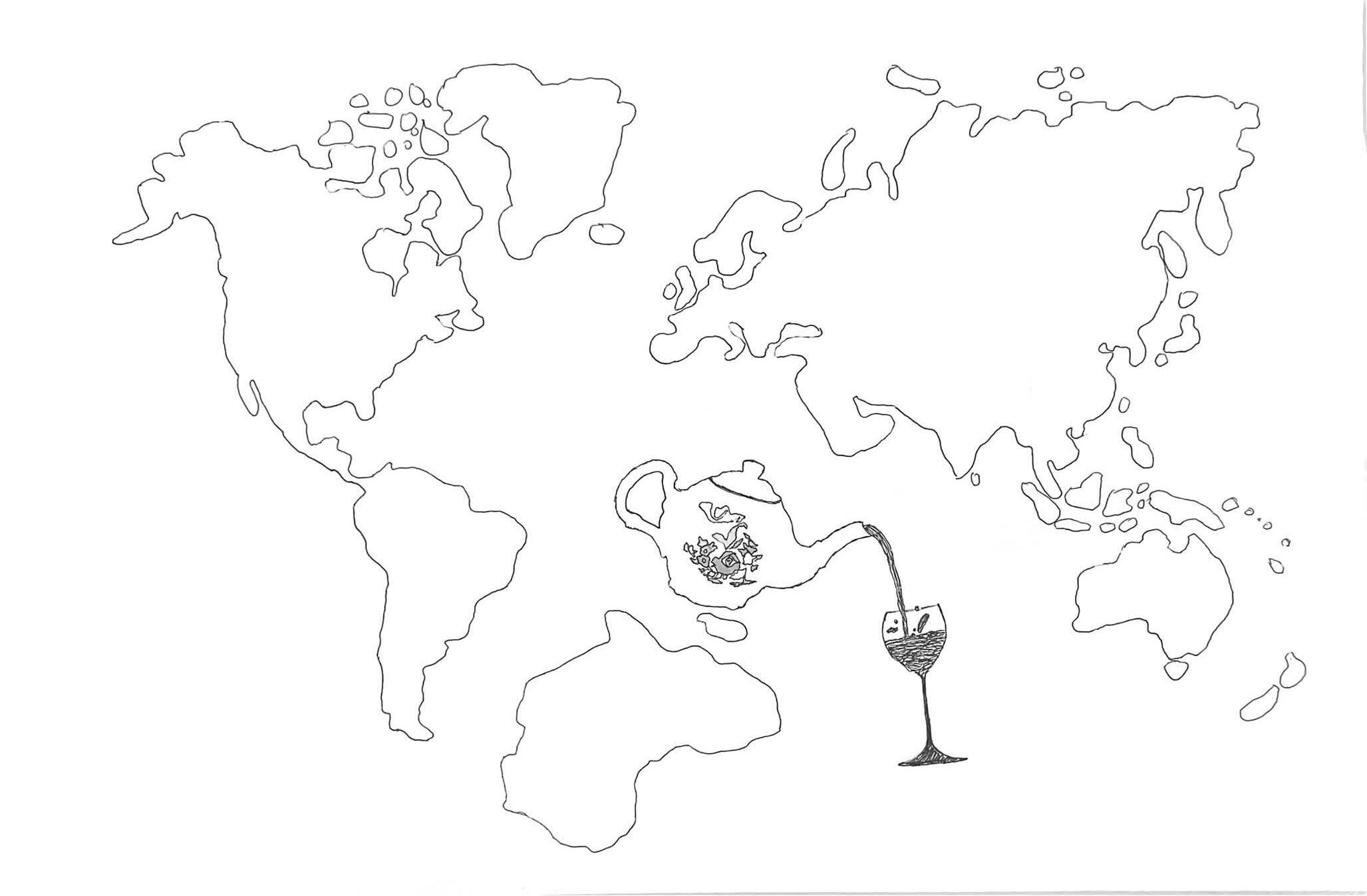

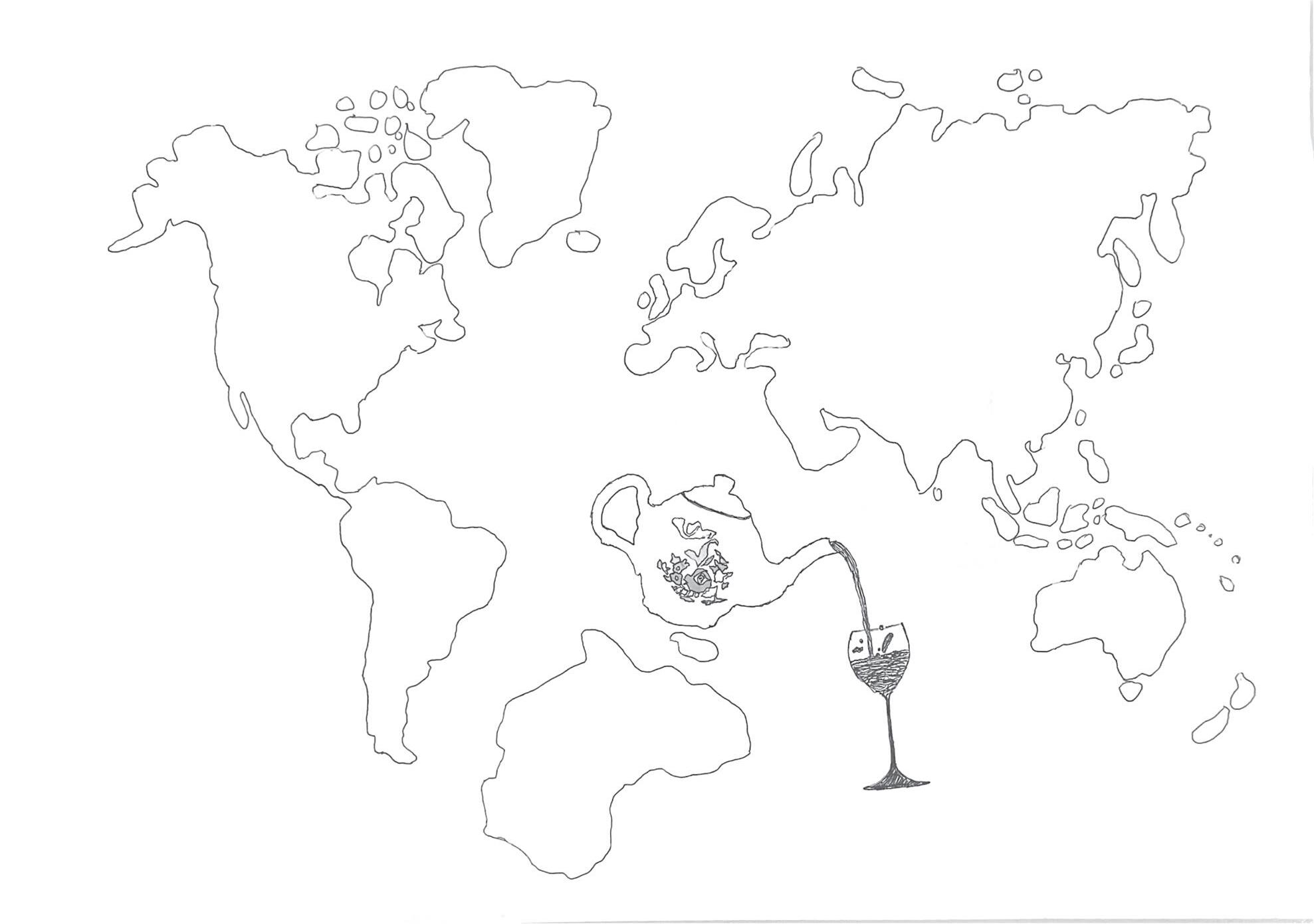

Imogen Sabey globetrots.

In my first year of uni, I came across a reading challenge called ‘Read The World’. It was simple: you read one book from every country in the world (although the creator had forgotten about a couple, like Micronesia). The challenge was on a website called StoryGraph, which is like Goodreads but for people who are a bit more snobbish. There were all sorts of challenges there and on similar reading platforms on the internet, designed to coax people into reading a bit more and to make them step outside their comfort zone. I took it up because I read a lot and cannot resist a challenge. I started ticking off the countries from which I’d read books, and found that there were barely more than a dozen.

As someone who works in a bookshop, and who purports to be well-read, this seemed to me like an unforgivable personal failure. It wasn’t from a deliberate avoidance of international literature that I’d managed to remain so insulated. I hadn’t made any concerted effort to breach the bubble of western literature that surrounded me, to go beyond the books that lay face-out at the library. I had been unduly influenced — especially as a young teenager — by sappy and old-fashioned romance novels that told me more about a culture (usually American) that I already knew than about what I didn’t know. The proportion of American literature in my reading prior to 2023 was so great that it revolted me. To this day, I consciously avoid American literature as a reminder of the shroud of ignorance that I had inadvertently created by reading it.

At once, I made up my mind to rectify this. The challenge was completely voluntary, created by a random user with about eight hundred participants. Similar challenges set up by the website administrators featured a selection of ten countries that would change every year — the 2024 version of this had about 12,000 participants. I dismissed the proffered system quickly; what good could it do to read a single book from China and another from the Vatican City?

So I set up a ratio proportional to the country, and contingent on that country having published books in English (or in other languages that I could read). For countries with populations of less than a million, I’d read at least one book, and for those of more than a billion, I’d read at least ten. For the rest, I would read about three. I set out to complete this over a decade, although it took about a year to complete more than a

editor, when I had so much free time on my hands that I could read over two dozen books in a month. Attempting this challenge forced me to seek out books from countries with very small publishing industries, often very small populations, and nearly always filtered through a language barrier. I had never stopped to consider how much of global literature is perceived by Western audiences and privileged by publishing houses, such as the Big Five (Hachette, Pan Macmillan, Penguin Random House, Allen & Unwin, and HarperCollins). But these publishing houses have a very careful marketing strategy that largely depends on big sellers by American, English, and Western European authors. Languages are crucial when it comes to making books accessible, because you have to have a translator for every single title, and sometimes there just aren’t many translators available for languages that are less widelyspoken. For indigenous languages in particular there are significant concerns about preserving languages that are at risk of extinction, and translating books across those indigenous languages and lingua francas like English or Spanish.

Art by Imogen Sabey

either passed down orally or recorded by foreigners. Consequently, when we read books about Mongolia, they are written by historians, travel writers, and naturalists.

If literature is our means of accessing a country without actually visiting, of surpassing the fickle impressions that social media provides so we can actually immerse ourselves in a culture, what can we do when that literature is unavailable? Books craft a crucial part of our impression of the world, and seep into our cultural imagination. It takes a split second to identify a dozen English novels which have directly shaped your understanding of English culture, like Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice, Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, or Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe

These are not books that you need to have read; they are books that are so well-known that it is impossible not to know them.

In Australia, we have the Indigenous Literacy Foundation (ILF), a charity organisation that aims to address the linguistic inequality of English compared with First Nations languages by translating childrens’ books into First Nations languages. The ILF works alongside First Nations communities to translate, produce, and publish books, as well as supply them to remote communities and support young children to learn in a mother tongue that is in danger. This goes some way to addressing the overwhelming linguistic authority given to English novels, with tangible benefits for First Nations communities. To have some version of the ILF present in former colonies whose indigenous languages are under threat would be ideal, but as yet Australia seems to be the only country to have such an organisation.

But when it comes to the books that we buy, and the books that are most frequently marketed to us, we rely in large part upon books that are widely credited as ‘good’ because these are the ones that publishers put the most effort into promoting.

International literary prizes play a large part in addressing reading imbalances in the global book markets. The Booker Prize is the most notable of these. Gone are the years when every person in the Booker Prize shortlist was a white man. Of course, it is not faultless: the Booker attracted considerable controversy in 2019 when the first Black woman to win the prize, Bernadine Evaristo, was also the first to share it — with none other than Margaret Atwood, a white Canadian woman who had already won it. (Which, if you ask me, was one of the worst decisions a Booker judging panel has ever made.) Nevertheless, it has led to sharp spikes in sales for all of its winners, which often allows titles more limelight

The countries that were most fascinating to me were those whose literature was not available, whether that be in Sydney, in English, or in the world. Mongolia, for example, has a population density of 2.24 per square kilometre, and a nomadic culture which does not correspond with the consumerist demands of a publishing industry. This is a country whose history is

This is, unfortunately, a pervasive literary power that most countries lack. These are what shape our understanding of the West, and create a selfperpetuating myth that is so deeply entrenched into our cultural psyche that we hardly notice it.

However, some countries have a markedly different circumstance: they don’t lack a national literary corpus, but that body is hindered by a political situation that places the chain of censorship upon every book in the public domain. In China, for example, there is a vast array of literature, and indeed of film, television, and art, but these forms of art published within the last threequarters of a century are necessarily inhibited in their expression, by what is and is not tolerable to the Chinese Communist Party. This has seen an extraordinary surge in literary and televisual works that focus on Ancient China, on a pre-CCP age, with a storyline catered to audiences who are discouraged from directly discussing modern politics. With stories that often centre around an everyman hero or a swoon-worthy romance, Chinese novels can get away with peppering in subversive ideas implied in the context of a romance novel that politicians do not consider worthy of serious attention.

Where our attention is frequently driven is to the novels that the internet tells us are good: to BookTok, to Goodreads, and to influencers on YouTube and Instagram who sometimes spend more time filming than reading. BookTok is becoming such a significant influence that publishers are now using tags on covers like “As featured on BookTok” as a marketing tactic. Getting recommendations from social media has, to some extent, become a substitute for getting recommendations from people whose job it is to sell books. This feeds into the idea that physical libraries or bookshops can be replaced with an entirely virtual

experience where books are sourced entirely through the internet.

Even within the optimistic outlook that our reading is not influenced by BookTok or Goodreads (which I like to think mine isn’t), we are never completely in control when it comes to our own reading choices. We are guided by bookshops, publishers, and marketing schemes that decide which books to pour money into for covers and promotion, and which books are not profitable enough to be printed by a major publishing house. This must, then, reflect the biases of both the executives of those publishing houses and of the audience whom they mass-market to. When audiences buy books by Western authors in great quantities, publishers don’t see a need to market more diverse titles, thus creating a cycle of artificially insular demand. So, when we collectively decide to read American or English literature because it is less of a cultural stretch to place ourselves in Manhattan than Baghdad, we contribute to a broader trend of reducing the profitability of books from other countries.

The argument could be made that American literature is so heavily featured in bookshops, reading lists, and literary prizes simply because it is better. If that were the case, why? Does America invest in literature in a way that the rest of the world doesn’t? Do they treat their writers with respect and accord them high status culturally? Different cultures will perceive writers in different ways, and there are varied working rights for authors across the world. In America, there seems to be a culture of almost fetishising writers, with figures like Edgar Allen Poe, James Baldwin, or Emily Dickinson known perhaps just as much for their personal lives as they are for their creative lives. As for other countries where writing is embedded into their culture, Ireland comes to mind as one where writers are given a notably elevated status. Seamus Heaney, an Irish poet, is a key example of an individual whose writing was enormously influential and far-reaching. During his lifetime, Heaney was appointed national poet laureate in Ireland and won a Nobel Prize in 1995, writing often on aspects

consciousness is a rare, sparkling jewel. So are internet challenges really that bad?

In reducing the literary world to a challenge that we take in order to enrich ourselves and our ‘cultural awareness’, we make each country a box to be ticked. This is not fundamentally terrible; if it makes people read, it makes people read. But we must be wary of the implications that lie within. There are plenty of countries with microscopic populations and vanishingly little novels (does anyone have a recommendation for Belize?). There are plenty more with towering national corpuses. Taiwan, for example, publishes around 40,000 books a year across 5,000 publishing houses, compared to Australia’s 2,000. This places it at the second-highest in the world for books published per capita. Nonetheless, Taiwanese authors are generally not household names, and their work is not easy to find.

its own borders. Nor can it reflect a thorough scope of literary talent, for we cannot give credibility to the claim that six-tenths of the world’s best books of 2024 emerged from the same country.

obituary of his cousin who was killed by accident during this conflict. After his death, his funeral was attended by members of Sinn Fein, as well as Bono. Memorial events were held across the U.K. and the U.S., and The Independent called him “probably the best-known poet in the world.” It is not a coincidence that this world-famous poet was Irish. Literature and culture are deeply intertwined, and Heaney came of age in a community that treasured poetry and treated poets like rockstars. Even so, I would argue that it necessitated the respect that Heaney accumulated in Ireland and the U.K. for his work to be widely read and recognised overseas.

The rest of the world, however, has a far greater cultural barrier to overcome in order to become part of ‘mainstream’ literature. For countries that have small quantities of published titles, due to a lack of local publishing houses, a smaller amount of state funding, or a bevy of obstacles besides, every title that emerges into the international literary

The issue here is threefold: we see what publishers want us to see, which is what is most profitable. We read what we are able to read, which is books published in English. We often don’t make much effort to read books belonging to countries or cultures with which we are unfamiliar. Sometimes people tell me that there is not enough time in a lifetime to read all of the books that they want to read, but is there ever enough time in a lifetime to do all of the things we want to do? If any of us tried to read every book in a single bookshop, it would take decades to pull off. But we can make an effort to read about people and places who are unfamiliar to us, translated from languages that we do not speak, born from literary traditions that are not our own. We must not read in order to tick off a box, but rather to learn about ourselves and about the world, and it takes more than an internet challenge to do this. The best kind of book is the one you find on your own: one where, as you open the pages, it opens a world to you. However, if you need somewhere to start…

Recommended reading:

Afghanistan: A Thousand Splendid Suns, Khaled Hosseini

Albania: Free, Lea Ypi

Brazil: Agua Viva, Clarice Lispector

China: Golden Age, Wang Xiaobo

Czech Republic: A Gardener’s Year, Karel Capek

Egypt: The Republic of False Truths, Alaa Al Aswany

Finland: The Summer Book, Tove Jansson

Iran: Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi

Laos: How to Pronounce Knife & Other Stories, Souvankham Thammavongsa

Malaysia: We, The Survivors, Tash Aw

Mexico: Mexican Gothic, Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Netherlands: The Safekeep, Yael Van Der Wouden

Nigeria: Under the Udala Trees, Chinelo Okparanta

Taiwan: Stories of the Sahara, Sanmao

Emily O’Brien talks to us in French.

“Remember to swim between the flags!”

“I wanted to flag this with you.”

“Can you hold this? I need to flag the bus.”

Whether we notice it or not we live inundated with both literal and metaphorical flags: red flags, green flags, white flags, beige flags, and most obviously, state flags. Iconography to symbolise a nation and its culture, history, and sovereignty. They serve as visual shorthand for a country’s identity. But what happens when flags, traditionally tied to national identity, are used to represent language? Let alone languages from countries that have colonial histories.

The Union Jack was first raised in so-called Australia on 29th April 1770 by Captain Cook at Botany Bay, and thus English became the supposed language of the land. Today, the English language is represented by either the United Kingdom’s Union Jack (UK English), or the United States’ Star Spangled Banner (American English). A question comes to the forefront: should the international symbol for a language be the flag of the country of origin, or the country where there is the biggest speaking population?

The answer to this question is deeper than the flag you select on Duolingo or the language card you chose at an international museum. Language is more than a means of communication — it is a reservoir of soft power for political and economic force. Colonial languages English, French, and Spanish are the lingua franca for the United Nations (in addition to Arabic, Chinese and

Russian) sustaining its political, economic and social power structures.

Just as politics and economics transcend borders, so too does language, evolving beyond its place of origin. Language is a living, evolving entity, growing outside of the country it was born in. Sixty percent of daily French speakers live in Africa, a legacy of French colonialism. The Academie Française, the principal authority of the French language, mired in its colonial supremacy, refuses to acknowledge the significant contribution African Francophones and African immigrants make to spoken French. Notably through slang called ‘verlan’, which has become infused into the daily French expression.

Verlan (the inverse of the French word l’envers which means ‘reverse’) involves taking the last part of the syllable of a word and placing it at the beginning of the word. Similar to pig latin in English, Verlan has become popularised in spoken French in major metropolitan cities, such as Paris. The colonial language has been adulterated, subverted by its former subjects, creating a powerful counter-cultural force of linguistic plurality. Yet the ‘Drapeau Tricolore’ remains the symbol for the French language. Should it be inverted to recognise Verlan as influenced by both North African dialects and Arabic,which feels like an entirely different language?

The question of how to represent a language is greater than just an aesthetic one: it is how we become conscious of historical realities and contemporary linguistic plurality. Should there be a consideration of linguistic plurality when representing a language, a nation, or a peoples? Would it be possible to reimagine the symbol for the English language to incorporate the countries with the largest proportion of English speakers; United States, India and Nigeria? Should it be a hybrid flag of sorts?

Flags are embattled emblems, tied to histories of dominance, conquest, and nationhood. If language is fluid and shaped by those who speak it, perhaps it is time to rethink how we visually represent it. Instead of relying on static and politically loaded national flags, we could adopt new symbols that better capture the shared and evolving nature of language. Whether through hybrid flags or entirely new icons, the way we represent languages should reflect their true global plurality, and not just their colonial past.

This piece includes references to sexual assault and gender-based violence.

A woman is awakened by the screams of an entrapped girl in the boot of a Fiat 127. Soon, police and residents would come to find a girl bruised and battered, and the corpse of her best friend.

On 19th September, 17-year-old Rosaria Lopez and 19-year-old Donatella Colasanti were invited to the movies by a group of boys they had only recently met. They were then taken to a villa on the outskirts of Rome, in Circeo, where, over the following 35 hours, the two girls were exposed to all kinds of violence.

With a horrific story like this, where do we even begin?

At the time of the Circeo Massacre, rape was not considered a crime against the victim-survivor, but against public morality. In other words, the act of rape was considered immoral instead of illegal. This law had been established almost 40 years prior by Benito Mussolini in 1936, and reflected the fascist mentality of 1930s Italy: a mentality where women were restricted in all aspects of life.

In an interview conducted in 1983, Donatella Colasanti described the assault as “[qualcosa] che va al di là dello stupro...”. Translated, “[something] that goes beyond rape…” What happened was a premeditated murder. The killing of the two girls always existed as an intentional plan.

Andrea Ghira, Gianni Guido, and Angelo Izzo were the names of the three men responsible for this crime. They were linked to fascist parties and organisations, and considered the kidnap, rape, and murder of two workingclass girls ‘entertainment’. The group of boys had met at Il Fungo (The Mushroom), a long-time meeting spot for fascists. The mentality of these men came down to one

thing: how can we prove ourselves as men?

To understand the evil of these boys, we must enter the walls of their school, San Leone Magno. A prestigious all-boys Catholic school, which served the principles of misogyny, classism, and fascism. The school in question was religious, but what mattered more was the fact that the student body consisted exclusively of males. They would enrol at the age of six and they left at the age of 19. For these 13 years of schooling, they would only have males as classmates and teachers. It was a laboratory, where male identity was created, and then reinforced with a relentless process of negation.

Following the Circeo Massacre and the three boys’ trial, they were all, initially, given life sentences. Andrea Ghira died in Morocco in 1994 after eluding arrest and having lived all his life as a fugitive. Gianni Guido, due to a sentence reduction, has been free since 2009. And Angelo Izzo, as soon as he was released on parole for good conduct in 2005, killed two more women: a mother and her daughter. In other words, the past wasn’t the past at all. Rosaria Lopez’s death and Donatella Colasanti’s torture ignited a debate that only concluded in 1996, more than twenty years after the events of the massacre, when Italian law was changed, and sexual violence was finally considered a crime against the victim-survivor.

This

radicalisation of young men and their insolent perspectives towards women continues to grow worse,

particularly with the use of social media.

The truth is, parents don’t know what their children are getting up to, especially when they have access to a

smartphone. With social media at the fingertips of all curious young minds, teenage boys have easy access to misogynistic rhetoric; namely Andrew Tate, who installs a revolting hatred towards women, as well as the concept of ‘incel culture’. This reflects directly onto the younger generations of men, creating a toxic, hatred-filled environment.

Last year, six students were expelled, and 21 suspended, following a bullying incident at the University of Sydneyaligned St Paul’s College. The episode involved a group of students who decided to conduct a ‘mock trial’ on a fellow student, in which the victim was allegedly sexually assaulted. Toxic masculinity and extreme misogyny, particularly in all boys prestigious schools, has been revolutionising education internationally for decades.

In an article published by The Guardian, a survey concluded that “teachers were being propositioned, threatened with rape, asked for nude photos, physically intimated, and having their classes disturbed by young male students moaning sexually during class — even in primary school.” As someone who attended a co-ed public school only three years ago, these accounts are unfortunately unsurprising.

We are raising generations of boys who are more liable to develop violent mannerisms. We have already seen them escalate into extreme cases, most importantly reflected in violence against women and girls. From 1970 to 2025, it is heartbreaking to see that extreme patriarchal violence continues to exist and increase.

Between highly accessible media coverage, and the private school community’s sheltering from the truth, boys have become more vulnerable to inheriting the wrong kinds of behaviours. Because of this, violence against women continues to exist, and as it continues to increase, adolescent girls will continue to face elevated risks of gender-based violence. Adolescent girls like Donatella Colassanti and Rosaria Lopez.

What does it mean to surrender? To wave a white flag? Is it an admittance of defeat? Or is it an opportunity to ask for help, as we allow ourselves to embrace the powerful force of peace?

The origins of the use of the white flag in times of conflict date back to Ancient Rome. During the Second Punic War and the Roman Civil War, soldiers used white wool and cloth attached to olive branches to retreat from war, submitting themselves to the mercy and protection of their gods above.

As it developed, this symbol was notably adapted as a request for ceasefire. Its use seen in central events of the Second World War. How would we reflect on these soldiers of war who surrendered? The men who submitted themselves completely to violence, sacrificing their minds and bodies, letting their blood nourish the soil

that we prosper on today. Were they cowards? Were they weak? Could we call individuals fragile or gutless for admitting defeat when they cannot go on any longer? It would be smallminded to say yes.

This small piece of cloth first waved by Roman soldiers is still used similarly today. In a world so defined by movement and development and opportunity, and noise; it is the truest show of bravery to accept our limitations. To take a step back, to realise the need for space to grow, and admit that you need help is anything but surrender. It is anything but defeat.

And so I urge you to rest. Ask for help when you need it.

School is hard, life is hard, friends,

Avin Dabiri surrenders.

boyfriends, family, jobs, painstakingly boring 50-page readings, it is all insanely difficult. Fortunately, there is always someone to lend a hand; as cliché as that may sound, it is true. In fact, there are studies proving that caring for others is inherently wired in humans. That to me is reason enough to reach out. If you stumble or fall, or simply need a moment to breathe in air untainted with everything that’s hard, there will always be a hand ready to hold or a shoulder to rest on.

Unbeknownst to most individuals today, the white flag did always operate on a deeper level. During war the flag could also be used to call for a truce — to engage in negotiation or bury one’s dead. This is even more evidence that to fall back and wave a flag doesn’t mean to surrender. It doesn’t mean loss or weakness. And as well as a show of bravery, it is also

“I Would Not Give These Up For Lent”: Rating Novelty

Eliza Crossley and friends put novelty supermarket hot cross buns to the test.

In Dante’s Inferno there are nine circles of hell. In the deepest circle, Satan resides. This final level is reserved for traitors, betrayers, and oathbreakers. I imagine Barrison Hennan here, forced for eternity to eat nothing but Iced VoVo-flavoured hot cross buns (Barrison Hennan failed to attend the hot cross bun ranking day).

On the weekend, I wrangled some friends to attend a thrice-postponed hot cross bun ranking day. Inspired by Nicholas Jordan’s Taste Test series in The Guardian, we sat down to put supermarket hot cross buns to the test.

We first discussed what feelings eating a hot cross bun should evoke. One reviewer said she wanted it to feel like a primary school lesson, where instead of doing maths, we were rewarded with Easter Bunny colouring sheets. Another focused on how the cross represents the crucifixion and expressed how hot cross buns evoke feelings in him of Catholic guilt, shame, and self-loathing. It was at this point that we discovered this reviewer actually doesn’t like hot cross buns at all.

With these complex feelings in mind, we decided on three categories on which to compare the buns. We were not after the classic or traditional fruit and spice bun. Instead, we ranked

the buns on originality, taste, and ‘Easterosity’. A final disclaimer: I am vegan and could only eat two of the six buns, the following reviews are based on what the taste testers told me to relay to you.

Iced VoVo buns (Coles)

This bun should have stayed as an idea. It had a gloopy, stocky texture and lingering coconut flakes. It was so solid that one reviewer questioned if it was put under a hydraulic press, and had both a colour and flavour that another described as “ostentatiously, poke-my-eyes-out pink”. I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy. 3/10.

Apple & Cinnamon buns (Woolworths)

With a flavour profile similar to cardboard, this bun was “dry”, “unremarkable”, and “uninspiring”. There was not enough cinnamon and too much apple skin. Despite being the most normal novelty bun, it did not evoke feelings of Easter time joy and instead is better suited for Halloween or even Christmas. 5/10.

Caramilk buns (Woolworths)

“Too corporate for Easter” and “simultaneously too caramilky and not caramilky enough”. If you want an Easter treat, get a caramilk egg instead. The idea was solid, but the chocolate execution could have been more sophisticated. It was very sweet and none of the reviewers wanted to eat a whole bun. 6/10.

Biscoff buns (Woolworths)

This was an honest bun. Unlike the caramilk version, it met the brief and delivered exactly as promised. One reviewer summed it up perfectly: “this tastes like biscoff so it is good”. It was lacking, however, in originality: “Why is everything Biscoff?” The answer to that is because Biscoff is a vegan delight! Bonus points for veganism! A solid 7/10.

Wagon Wheel buns (Coles)

A whimsical bun, while that “lacking in the ‘mallow, hits with the jam.” This bun was unlike anything we had tasted before and inspired some of the most peculiar comments of the day, including “this bun understands compromise, it’s nuanced” and similarly, “festive without being obnoxious, it is restrained.” While not really a wagon wheel at all, this bun was beloved and rated a whopping 8/10.

Vegemite & Cheese buns (Coles)

“I would not give these up for lent.” This bun topped the ranks. The savoury twist was very much appreciated, even though the flavour had only “undertones of vegemite”. Give me more — more cheese, more vegemite, butter advised. One reviewer fantasised about making a Vegemite and cheese hot cross bun toastie. The entire bag was eaten. 9/10.

As Christ forgave us, I forgive Barrison Hennan.

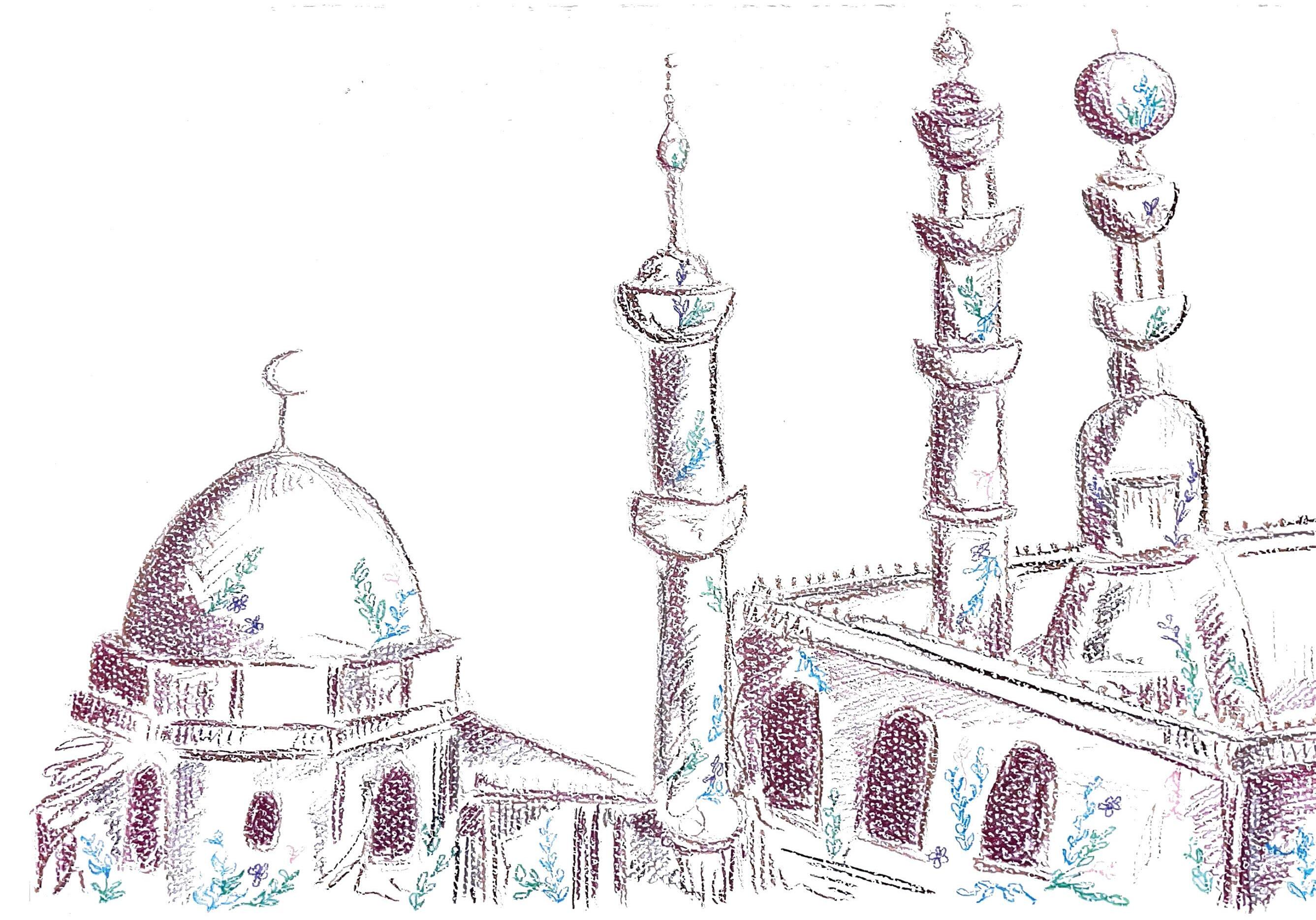

Hamna Khan dives into the Golden Age. Have you ever wondered about the origins of the tools we use today? Where did they come from and who invented them? Well, you might be surprised to find out that many of the inventions we use today, especially in the area of medicine, came from a period of rapid revolution known as the Golden Age of Islam. Coincidentally, this era occurred simultaneously with Europe’s early Middle Ages, otherwise known as ‘Dark Ages’. The Dark Ages are known as a period of relative intellectual stagnation and political turmoil in Western Europe. Meanwhile, in the Muslim empire, the Golden Age of Islam was taking place, most notably in medicine.

The Golden Age of Islam is said to date from the mid-7th century to the mid-13th century. During this time, Baghdad, the capital of modern-day Iraq, was the centre of the Islamic Empire. This city became a bustling trade centre, where goods and ideas were exchanged. Universities, hospitals, schools, observatories and libraries were established for the pursuit of knowledge. The Islamic empire was under the control of the Abbasid caliphate at the time. The Caliph, or ruler, Harun al-Rashid and his son, Al-Ma’mun, established a ‘House of Wisdom’ — a dedicated space for scholarship, teaching and learning. The House of Wisdom, from 813 to 833 C.E., was well known at the time, and was visited by people from faraway lands to expand their knowledge. Famous scholars were invited to come to the House of Wisdom. It was a learning hub for Muslims, Christians, and Jews who all collaborated and worked peacefully together.

The hospitals built in Baghdad were some of the first in the world and treated rich and poor people as equals. In medicine, one prominent figure was Ibn al-Haythm, who was able to form an explanation of how the eye sees, which led to the invention of the first camera. Ibn Sina (also known

as Avicenna), a doctor and philosopher, wrote the Canon of Medicine. This was the world’s first medical textbook, which helped physicians diagnose dangerous diseases such as cancer. Another figure, Abu Bakr Al-Razi (also known as Rhazes) made contributions in our understanding of the spread and nature of infectious diseases. Even to this day, Al-Razi is well-known in the Middle East for his detailed description of smallpox and measles. Together, Al-Razi and Ibn Sina are credited with the invention of the quarantine method, which recognises the importance of preventing diseases from spreading by isolation.

Another figure, Ibn al-Nafis, is known for his developments in discovering the cardiovascular system. He was the first to provide a description of the pulmonary circulation. In that description he suggested that blood does not permeate the interventricular septum in the heart; instead, it circulates in the lungs through the pulmonary arteries and veins. This was a new development at the time, as it built on previous work, which had not yet recognised the large amount of blood that flowed from the heart to the lungs and back to the heart.

Furthermore, one more prominent figure, Al-Zahrawi, known as the ‘father of modern surgery’, made significant contributions to surgical techniques, inventing over 200 surgical instruments. He also utilised a new innovative material, catgut (a cord made from animal intestines — usually sheep or goat, rather than cat), for internal suturing of wounds. Furthermore, he detailed procedures for various operations, many of which are still practiced today in modern surgery. He specialised in the technique of cauterisation, which used burning a part of a body to close it off, in an attempt to mitigate bleeding or minimise infections. Al-Zahrawi also pioneered neurosurgery

and neurological diagnosis. He is known to have performed surgical treatments of head injuries, skull fractures, spinal cord injuries, hydrocephalus (a condition where cerebrospinal fluid builds up in the brain causing a pressure build up in the skull), and headaches.

In the mental health field, many prominent figures in medicine from the medieval Arab world created ways to understand the relationship between the mind and body. Once again, the two physicians, Al-Razı and Ibn Sina, incorporated methods in clinical practice to address psychological issues. Razi wrote a treatise in spiritual medicine titled, Al-Tibb arRuhani, in which he explained his ideas on psychotherapy focusing on the spirit or ‘ruh’. Similarly, Ibn Sina wrote an important book, Kitab Al-Nafs, in which he examines Sufi teachings as a cure for the soul, which he refers to as the ‘nafs.’ Ibn Sina believed that the body and soul can be separated, and the soul is immaterial, immortal and does not perish with the body.

The Golden Age of Islam needs more recognition as many of the inventions and advancements that were taking place at the time are still relevant today, especially in the field of medicine. Ultimately, there are many other contributions in areas such as astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, arts, and literature. You’ll be amazed how applicable the contributions from that time are to your life!

If you or a loved one are experiencing distress, please contact the resources below:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636

Griefline: 1300 845 745

Financial Resources:

Legal and Financial Support: 1300 888 529

The Australian Workers’ Union:

Sath Balasuriya mines for the answers.

Content Warning: Injury and Death in Mines.

I was scrolling on Facebook when I heard of Eli Kelly’s death.

Eli and I attended the same high school in Tamworth, NSW. He was a familiar face: only two years older than me, and I had spoken to him once or twice. The article stated that he had been working as a ‘fly-in fly-out’ (FIFO) subcontractor in a gold mine near Kalgoorlie, when he tragically suffered fatal injuries on site. As I refreshed the post, condolences flowed in from people Eli and I grew up with, but also from many names I didn’t recognise. One comment in particular stood out to me, with a woman named Nikki Hogan commenting: “Another one! Same mine site that took my brother [Terry Hogan] less than two years ago.”

This was sobering to read. Were Eli and Terry’s deaths untimely accidents, or could they have been prevented somehow?

To disprove my suspicions, I set out to investigate what I thought were a spate of disconnected workplace accidents and fatalities in Western Australian mines. What I uncovered was a web of workplace safety issues rooted in the systemic failure of a resources industry which many consider to be among the world’s best regulated.

Before we jump to that conclusion, we should start at the birthplace of these tragedies. The gold mine, called St Ives, spans over 75,000 hectares and consists of both underground and pit operations. It has around 1,600 reported staff, 80% of whom are contractors and subcontractors. It sits in the deposit-rich Eastern Goldfields Region, where the first commercial operation began in the 1980s. The Western Mining Company owned St Ives until it was acquired by Gold Fields in 2001. Gold Fields now owns and continues to operate four mines in Australia, the largest and most valuable being St Ives, where close to 400,000 ounces of gold are reportedly mined annually.

While the accidents at St Ives were horrible surprises, could they have been feasibly prevented? When dealing with an industry as large and as inherently dangerous as mining, is it fair to assume that regardless of the level of safety, there will always be unpreventable deaths? Current legislation and research in risk management distinguishes between “principal hazards” and “one-off events” when it comes to answering questions like these. David Cliff, a professor in Occupational Health and Safety in Mining at the University of Queensland, makes the case that the vast majority of fatalities within the last ten years have been due to one-off events. In differentiating between the two terms, Cliff claims that principal hazards are multicasualty incidents typically involving large scale failures in mine operations, such as the 1994 Moura coal mine explosion. Conversely, one-off events like vehicle failure are typically more random and cause individual fatalities or injuries.

Contrary to the grim picture painted so far, Cliff argues that since 2003, most major principal hazards in mining have either been eliminated or wholly reduced through effective risk management and

training, now accounting for less than 20% of total accidents within Australian mines. Data from Safe Work Australia seems to agree with this. The fatality rate in WA mines has dropped significantly, from 12 deaths per 100,000 workers in 2003 to 3.4 deaths per 100,000 workers in 2013. However, Cliff holds that this positive trajectory has not been maintained since. He argues that one-offs are mostly to blame for the spate of recent tragedies. Evidence shows that accidents in this category such as crushes and falls are not only failing to decrease in incidence, but contributing more to total causes of deaths each year. Given the seemingly sporadic nature of one-off events, Cliff contends that most standards designed to reduce principal risks have been ineffective at curtailing them. Instead, they continue to persist as evolving puzzles for regulators to crack.

In spite of the odds that we may never see Australian mining become a zero casualty industry, Cliff remains convinced that it is fruitful to reform current OHS protocol to combat the rise in one-offs. He cites some change in the form of Rio Tinto’s critical control management model, which according to Cliff seeks to “identify a small number of vital controls… and directs resources towards rigorously designing, implementing and maintaining them.” He claims that while progress with such programs may be possible, it will likely be unstable long-term given systemic factors that the mining industry is reluctant or unable to change. For example, the Queensland resource industry’s latest ‘Safety Reset’ report found little positive change in overall OHS levels across the five years it was conducted, despite the implementation of initiatives similar to the ones Cliff mentions. Programs like these offer very little hope of enacting meaningful change to Australian — especially Western Australian — mining. When the number of annual fatalities for 2023 matched those from ten years prior, how can we say any effective solution exists?

Other researchers in the field challenge the attention Cliff places onto the kind of risk that occurred as a contributing factor to these deaths. They claim that a more insidious cause may be more responsible. In an extensive literature review published in 2024, Doctor Heather Jackson and Professor Emeritus Michael Quinlan conclude that the Australian mining industry’s overreliance on contractors and subcontractors has exacerbated poor worker wellbeing in mines. This has led to their overrepresentation in deaths and serious injuries, a figure reconfirmed in a 2024 annual report by Gold Fields. Their argument challenges the view that one-offs are random events with little in common with each other, by proposing that a pattern emerges when we better examine who is involved in these accidents rather than the type of accident that occurred. Speaking to ABC News, Quinlan revealed that four of the five mining deaths reported in the Eastern Goldfields and Pilbara regions since 2022 were contractors. To add to this, just days after Terry Hogan’s tragic death at St Ives, there was another death in a gold mine near Newman, with both occurring less than 18

months prior to Eli’s death, and all of them being subcontractors.

It’s important to note that the Australian resource industry’s need for contractors (in all forms) is part of a broader trend in neoliberal economies worldwide. For corporations like Gold Fields, a significant part of having an effective business model and maximising profits involves routine cost cutting of internal expenses, independent of whether the market is in downturn or upturn. But after significant downturns, what follows is especially aggressive cost-cutting. Following the end of the 2013 Australian mining boom, the mining sector saw this play out, leading to drastic labour shortages as recorded in a 2019 study. Jackson and Quinlan note that after these shortages, contractors capitalised on the demand for increasingly cheaper labour by cutting costs within their own businesses in order to make their services more competitive to hiring operators, resulting in a workplace that employs fewer permanent employees and more contractors. The Financial Times reported that while the global workforce for mining giants like Rio Tinto, BHP, and Anglo American fell by a third between 2013 and 2018, the percentage of contractors actually increased. In fact, switching to external contractors is such an effective cost cutting measure that it saved an average of 14% in operating costs for 10 mining firms according to an Australian case study from 2004.

some time.

Contracting has also been shown to weaken the power of unions in mines, even though unionised mines have been shown to be substantially safer. Quinlan told me that by relying on a large semi-permanent workforce, mining firms effectively eliminate the conditions required for strong unions to form, with the unions persisting in these sites often lacking major bargaining power. For example, following news of Terry Hogan’s death in early 2022, Australian Workers Union representatives claim they were prevented from entering the mine to assist Gold Fields with initial investigations, even though entry was legal. The West Australian reported that the union was required to file for a special entry under the Industrial Relations Act to be granted access into the mine by operators. Similarly, The Financial Times said that it was not uncommon practice in Queensland jurisdictions for lawyers hired by mining corporations to be first on site following an accident, despite outcry from unions that the concerns of workers weren’t being adequately addressed when done so. Ray Parkin, former chairman of the Queensland Mines Rescue Service, claimed that legal interference “lock[ed]-up” vital information from unions, leading to slower and less transparent investigations.

The literature review identifies several reasons why an overreliance on contractors has led to declining wellbeing within Australian mines. The first of which, the authors claim, is their exploitation by bosses. Given the precarity of their working arrangement, a 2022 thesis analysed in the review claims that FIFO and drive-in drive-out workers are made to do more “dirty work” in unsafe conditions. Due to their perceived inferiority within the workplace hierarchy, contractors are less likely to raise concerns and halt dangerous work early for fear of not being promoted and receiving better pay in a more permanent job if they do.

In an interview for Honi Soit, Quinlan revealed that the combination of stressful workplace and employment conditions, alongside long stints away from home, made for the perfect storm for worsening mental health.

Jackson and Quinlan also claim that cost cutting measures within contracting companies force them to implement cheaper and less stringent training and OHS protocols. A 2022 case study surveying 2009 workers in the resource sector found that this led to a mediocre perception of the effectiveness of OHS regulations meant to protect them. Contrary to what mining corporations claim, the expertise they chase when hiring specialised contracting agencies does not necessarily translate to expertise in safety or risk communication. Widespread cost cutting measures hit even the most specialised contractors hard, according to Quinlan and a cross-sectional study conducted by Valluru et al. The literature review points out that many accidents involving subcontractors are overrepresented in routine repair and maintenance tasks. While proper auditing would be expected

But where does this leave us with practical solutions? Legal reform may work in the meantime, with the recent Work Health and Safety Act implementing the harshest penalties for industrial manslaughter in WA’s recent history. Reforms like this have allowed WorkSafe WA to successfully prosecute two contracting agencies and one mine operator for separate instances of negligence and failure to create reasonable health and safety standards in 2022. While punitive legislation in this area has shown some promise, the Australian mining industry has otherwise opposed laws codifying ‘same work same pay’ principles which would ensure that all workers are paid the same for identical work in the mines. Concluding their review, Jackson and Quinlan recommend a significant reduction in the use of contractors, most notably in the areas of

Madison Burland reflects on her teenage dating life.

It’s 2020 and we’re in the Trump administration. I’m in Year 10 at my all girls Catholic school. I’m 15 and I think I have a crush. I’m on the phone to this boy who I haven’t known for more than a few months, when his answer to a hypothetical question unsettles me. “If we were in America, I would have voted for Trump,” he snickers. “It doesn’t matter, we’re Australian anyway.” I couldn’t seem to wrap my mind around this rhetoric. Talking to a boy my age, realising he had a MAGA mindset and entering this vicious cycle of arguing, I fell into a bit of a saviour complex. I tried to fix the opinions of every mediocre white boy who came into my path, as if somehow my hatred of Trump would be enough for them to respect me as a person. I wondered why I couldn’t change them. Everyone surrounding me in all aspects of my life had seemed to be reminding me that difference is good. Vis-a-vis: “You don’t have to agree with everyone on everything, but you do have to respect each other.”

During my early teen years, this was the norm. Especially within relationships, there was often an unspoken pressure to conform to predefined roles and expectations of complacency from women. The idea that expressing opposing beliefs or questioning expectations may cause

disruption in a relationship is used as a tool in encouraging people, especially women, to stay complacent in order to maintain the peace. Commonly, left-leaning young white girls date right wing Trumpsupporting boys, in a misguided and futile effort to try and change or fix them.

As a 15 year old trying to understand my place in the world, I spent the rest of my highschool life trying to internalise this and “embrace the differences”. For those few years between, I decided to spend some time working on myself and learning how to calm myself down, falling victim to the argument that there is more to life than politics.

When I started university, I realised that there is something worse than being perceived as loud and political: being complacent. In 2023, Trump was found liable for sexual abuse. Whether you argue you are not politically up to date, or you like him for his economic policies, there is nothing that is more of a slap in the face to assault victims and women worldwide than backing a candidate who is a convicted sexual abuser. Finding out men in my life simply did not care was a wakeup call. Politics is always personal.

how American beliefs have become more liberal in the last 50 years. With that in mind, we’re in an intensely polarised political moment and it’s important more than ever to fight against complacency. Even in our relationships. Tinder did a study on how much politics impacts relationships, finding out that 1 in 5 people believe political apathy is a relationship dealbreaker.

The Financial Times reported that globally there’s a growing ideological gap. Women are becoming more liberal and men are becoming more conservative, and this is reflecting in their relationships. The rise of the far-right is increasingly common in our world, with Trump re-entering office, and the far-right party in Germany capturing double their 2021 percentage of votes this year during the election. Far-right beliefs are not only rising in our governmental sphere but also on social media.

NYU recently released data that discussed

empowerment and autonomy, rather than complacency within their relationship. Politics is becoming more central to our identities as issues of race, sexuality, and gender are at the forefront of most parties’ agendas and political discourse. Our political views are formed by our identity and our experiences, and when someone we date has a different view, it’s almost impossible to ignore the fact it feels like an attack — because it often is.

Conservative internet voices, like Andrew Tate and Charlie Kirk, are emboldening young men to implement conservative and misogynistic values in their relationships.

The widening division of gendered labour and expectations surrounding how to dress means it’s impossible to ignore politics within a relationship, in a society where women are beginning to truly fight for

A young man who spends his time listening to alpha podcasts that prioritise toxic masculinity will not respect a young woman fighting for abortion rights. The differences in beliefs are no longer distant enough to ignore. More than this, it’s imperative that we do not ignore them.

When we teach young women to neglect their own morals, values, and political identities in order to appease society and placate young men, we risk protecting the status quo and worse — we risk undoing all the work feminists have done so far. With so much more work to do, we have to encourage teenage girls to be critical of their relationships and continue to question the growing political gender gap that neoliberalism encourages us to ignore.

Art by Mehnaaz Hossain

Kiah Nanavati explores the depths of the ocean.

Have you ever wondered what lurks in the farthest reaches of the ocean, where sunlight fades into eternal darkness, where life thrives in the most unexpected ways?

The truth is we’re still not sure. What we do know is that these inhospitable environments — under crushing pressure, in near-freezing temperatures — have been considered Earth’s final frontier. However, recent discoveries have shattered previous assumptions, unveiling a trio of deep-sea marvels that redefine our understanding of evolution, adaptation, and ecological interconnectedness.

Did you know that have only uncovered 5 percent of the ocean so far? That means 95 percent of the deep sea still holds secrets unknown to humanity, but we’re on the journey to the deep to find out. Let’s dive in!

One of the most fascinating recent finds is the Bathydevius caudactylus a bioluminescent sea slug discovered on the shores of Monterey bay in California. Unlike any known gastropod, this creature has developed an intricate bioluminescent display, to not only evade predators but also to lure unsuspecting prey, akin to a Venus flytrap of the deep. Bioluminescence in marine organisms is typically a defensive strategy, but Bathydevius has turned it into an active hunting mechanism, emitting pulses of light that momentarily confuse its prey before snaring them in its specialised feeding appendages. This adaptation is a striking example of the deep-sea evolutionary arms race. In the pitch-black environment of the abyssal plain, vision is limited,

and organisms have developed unique strategies to communicate and survive. Bioluminescence — produced by specialised photophores — is an evolutionary answer to a lack of sunlight, allowing organisms to attract mates, deter threats, and, as seen in Bathydevius, deceive prey. Scientists believe that such adaptations are driven

are disrupting deep-sea thermal layers, forcing species to migrate in search of suitable habitats. Another suggests that declining oxygen levels, caused by ocean deoxygenation, are making deeper waters inhospitable, compelling species to move toward oxygen-rich shallower zones.

If this trend continues it could have

may start exploring new environments. These migrations could have cascading effects, potentially disrupting longestablished ecological balances.