Honi Soit operates and publishes on Gadigal land of the Eora nation. We work and produce this publication on stolen land where sovereignty was never ceded. The University of Sydney is a colonial institution. Honi Soit is a publication that prioritises the voices of those who challenge colonial rhetorics. We strive to continue its legacy as a radical left-wing newspaper providing students with a unique opportunity to express their diverse voices and counter the biases of mainstream media.

In This Edition...

Behind Closed Doors

Budget 2025-26

Eat the Rich

Pay Inequality

Sexy Serial Killers

In conversation with

Moz Azimitabar

Interviews

SRC Casework

Puzzles

‘Smooth criminal’ is the embodiment of all things politics, society, and the arts.

This edition covers a broad basis of issues in carceral systems: the lives devastated, the voices silenced, and importantly, how carceral and settler-colonial violence is resisted.

We hope you will take away reflections on how the current carceral systems must be dismantled and hope for a world that doesn’t lock children up.

In this week’s feature, Jack Glass investigates just how fucked up

our carceral system is here in socalled Australia.

Our editors are also back from the budget lockup in Canberra! In this edition our very own Charlotte, Imogen, and Mehnaaz break down the 2025 Federal Budget for you.

Within these pages, Ellie Robertson analyses our criminal justice system, Lilah Thurbon reasons why the age of criminal responsibility should be raised, Audhora Khalid urges us to listen to First Nations voices, Hamna Khan reflects on Eid and the Lakemba Night Markets,

Dirsten is a third-year architecture student exploring how art and the built environment can give a voice to the unseen and unheard. Growing up in the Philippines, I was surrounded by art, music, dance, and performance — but rarely in architecture. It is my responsibility to design spaces that uplift the human experience rather than conform to the rigid concrete structures of capitalistic consumerism.

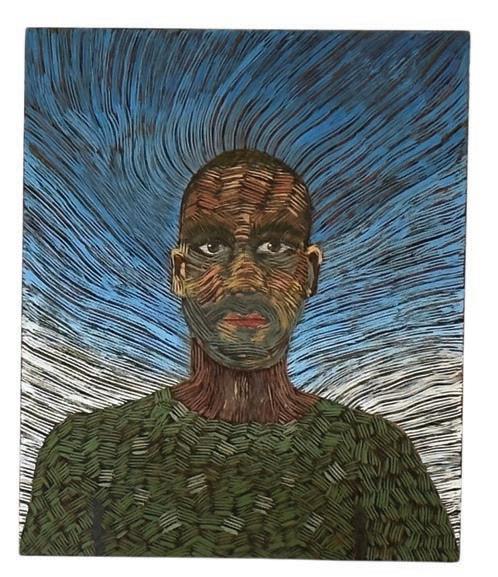

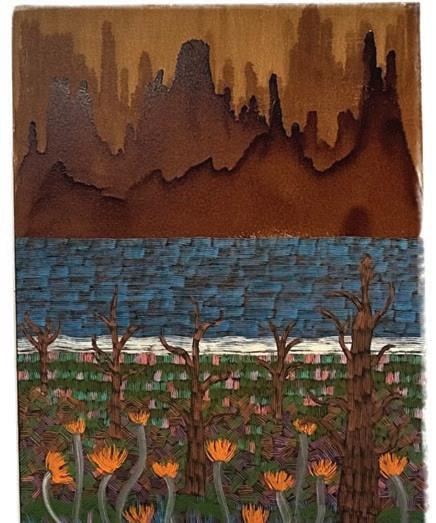

Emma Georgopoulos warns us of the danger of glamourising murderers, and Emilie GarciaDolnik and Annabel Li dive into the art of refugee Mostafa ‘Moz’ Azimitabar.

Enjoy this week’s edition of Honi!

Love and solidarity, Honi Soit

Follow on instagram for more: @dirawsten @tenjxd

Editor-in-Chief

Editors

Purny Ahmed, Emilie Garcia-Dolnik, Mehnaaz Hossain, Annabel Li, Ellie Robertson, Imogen Sabey, Charlotte Saker, Lotte Weber, William Winter, Victor Zhang

Martha Barlow, Calista Burrowes, Valerie Chidiac, Avin Dabiri, Ethan Floyd, Emma Georgopoulos, Jack Glass, Audhora Khalid, Hamna Khan, Emily O’Brien, Ilham Qadri, Phoebe Rosser, James Fitzgerald Sice, Jessica Louise Smith, Thea Swinfield, Lilah Thurbon

Crossley, Celina Di Veroli, Hamish Evans, Leanne Rook, Anu Khulan, and Norn Xiong.

Please direct all advertising inquiries to publications.manager@src.usyd.edu.au.

To Will Thorpe and Honi Soit, I read Will’s letter to the editor in last week’s edition and felt as if I was finally breathing fresh air. The way that artificial intelligence has infiltrated academia is undeniably concerning.

In particular, the way it has seeped into the discipline of Digital Cultures is frightening. In almost every one of my ARIN1001 tutorials last semester, students were filling their Padlet submissions with ChatGPT outputs. I have seen students (who likely just don’t know better) citing ChatGPT as a source of information in presentations and formal assignments.

Worst of all, I believe that artificial intelligence has infiltrated Digital Cultures from the top down. For assignments in ARIN1010, the assessment guidelines appear to have been generated using a large language model. The spelling is Americanised, with z’s where there should be s’s.

The use of emojis is uncanny. They ‘strongly encourage’ the use of AI tools for assessments and suggest you read the ‘AI use guide’, which also appears to be AI generated. In contrast, the 2024 assessment guidelines for ARIN1001 had Australian English spelling, no use of emojis, and had the written tone of a human being.

If my suspicions are correct, where is the artificial intelligence declaration? Academic integrity, anyone?

The University must do better than this.

Evie Gawlas

Dear Honey,

So I’ve noticed lately that when I try to involve myself in conversations with classmates and peers or even cause anyone random really... they have to weave into the conversation that “I have a girlfriend” or “My Girlfriend...” Huh???? Orrrr sometimes even I get “My Boyfriend...” too, When I’m straight!

What is that all about? Is that me? Do I do this to people? Or is it other external factors?

Do people think I’m getting the wrong idea and shut it down? Or Are guys feeling guilty talking to a girl if they have a girlfriend? Or am I not attractive at all? Am I that bad that people have to reject me subtly on the the spot?

And Hold up! Why can’t I just talk to people without them thinking I’m hitting on them? Like come on!!!! 99% of the time I don’t have those intentions anyways! Why on earth do people assume that I’m hitting on them? I’m just a really overly nice person! It’s just apart of my personality! I’m a ENFP on the 16 personalities test, deal with it! Yes, I message too much, I like stories too much, I’m too invented [sic] in people I talk to but I actually care! And if your [sic] really going to think that I’m hitting on you, just to put you into perspective... your [sic] not that special, everyone I meet is equally just as special! I give that same about of generous attention to literally everyone, ask my friends! they know me! And it’s kind of a problem if I’m honest! I’m too agreeable, and too nice and am a bit of a pushover!

Maybe I just want a lot of validation? Maybe people aren’t used to really nice people and are suspicious of them? Maybe I cant read social cues as well as I thought and maybe I am too nice and might suggest something more without realising it? But maybe this is all just my confirmation bias?

What do you think Honey?

With an Abundance of love, Miss Involuntary Pick Me

Dear Miss Involuntary Pick Me,

If your flirting skills were as good as your proofreading, you wouldn’t be having this issue.

It is not a weakness that people mistake your kindness for flirtation. You should weaponise that. Get free drinks at the bar, avoid paying your fine for not tapping your opal card, bat those little eyelashes, and get past security at the bank. One day, people will think you just want to be friends, and that will be the true sting. And, if you weren’t already [sic] of it, I’d suggest enjoy it. You’res [sic], Honi [sic]

Art by Ellie Robertson

SUDS Presents: Call of the Void 1st-5th of April at 7pm Flight Path Theatre Banana Farm EP Launch w/ Jude Pescal Friday 4th of April at 7pm Oxford Art Factory Gallery

Calliobel’s “Blue Eyed Dragons” Launch Saturday 5th of April at 6:30pm Lord Gladstone Hotel

USyd F1 Society: Japanese Grand Prix Watch Party Sunday 6th of April at 2:30pm Royal Hotel Darlington

Later in the year... Student Journalism Conference 15th–18th of August at USyd

More details coming soon!

Martha Barlow reports.

CW: Images and discussions of femicide, deceased persons, and domestic and sexual violence.

Just three months into 2025, 14 women have been murdered. On Saturday 15th March, Sherele Moody, founder of Femicide Watch and the Red Heart Campaign, called a series of rallies around the country with a simple demand:

The rally was passionately and sensitively chaired by activist Ela Akyol. Between speakers she led chants, shared anecdotes, and highlighted the three demands of the rally: to educate young boys at the school level on how to treat and respect women, reform on Domestic Violence Orders, and abundant increases in funding for domestic violence services. The tone of the rally was sombre and intimate, with most attendees sitting down in order to truly listen to the words of each speaker. In front of the speakers was a spread of photos — each bearing the name and face of the 117 women killed in Australia in the last 14 months.

The first speaker was Lorna Munro, a Wiradjuri and Gamilaroi poet and artist. She began by emphasising how it is impossible to talk about violence against women without addressing the foundational violence against First Nations women that this country is built on. She shared that Aboriginal women are 64 times more likely to be victims of domestic violence than white women, and that the roots of this violence lies within colonial institutions. Illustrating this, she pointed to the work of Aunty Irene Watson, a professor at the University of South Australia, whose research traces the role of police and churches in destroying Blak matriarchies, and howthese institutions taught men to shame, abuse, and humiliate Aboriginal women. She ended with a call to action to stand in solidarity with Aboriginal women, because “the colony is afraid of solidarity.”

Next to speak was Hannah Thomas, the Greens candidate for Grayndler. She began by reiterating that one woman is killed every four days in this country, and that these never make headlines, especially when the victim is a woman of colour. Thomas noted that for every woman that is killed, far more are controlled, isolated, and abused. She shared the story of a woman she knew, Tabitha, whose abuser had recently been released on parole. Tabitha was repeatedly refused relocation by housing services and politicians, and turned away by the services she begged for help. Her story shows that the priorities of the government are all wrong, Thomas said. There is no reason why in a country as wealthy as Australia, victims should have to fight for scraps of safety. She urged the government to take further, meaningful action on violence against women instead of investing money in submarines and defence projects.

Azz Fahmi, a community organiser and

human rights advocate, spoke next. She opened by expressing a wish that we didn’t have to have these rallies, and emphasising that every woman killed is a person, not just a number. Expressing her frustration at the lack of attention given to the issue of domestic violence and femicide, she stated that men only care about this issue when it happens to their own sisters or mothers. Having worked in refugee services, she shared her experiences of overcrowded and underfunded shelters and services, and how the conditions or risk of being turned away from these often forces women back to their abusive partners. She spoke of this issue being exacerbated in Muslim communities, especially for recent immigrants and refugees who often do not speak English and lack the culturally sensitive services to help them. She spoke of the specific intersection between violence against women and Islamophobia, sharing that 79% of victims of Islamophobic violence in the last year were women and girls. She closed by noting that politicians only care about the economy, so perhaps framing the issue in terms of its economic impact will make them listen. To that end, she shared that the government spends around $26 billion a year on domestic violence, including services, health care, and lost work. There are also long term issues for children who witness or experience family violence, as they are more likely to suffer from mental health issues and be involved in crime. She thus reiterated the core demands of the rally, for better funded domestic violence services.

Akyol then took a moment to speak about the two ‘types’ of victims; ideal and cautionary. Ideal victims are typically white, professional, university educated, and far more likely to have her death reported in the media. The life of the cautionary victim, on the other hand, does not carry the same weight. She is poor, or a woman of colour, or a sex worker, and if her death is reported on, the media will dredge up bikini photos or irrelevant details of her life to suit whatever narrative they are trying to create. All forms of violence that women face need to stop, she concluded. Every woman killed should have their life honoured.

Next to speak was Meaghan Dolezal, an artist and domestic violence survivor. She spoke of the structural factors contributing to femicide, noting that it is not “random or inevitable,” but the direct result of a system that devalues women’s lives. She stated that the consequences of violence do not fall on all women equally, and that it is up to those who are privileged, white, and economically stable to speak up for the ‘imperfect’ victims. Our duty, she concluded, is not to take up space, but to create it.

Next to speak was Viv, a sex worker and community organiser. She shared that she was choosing to speak as herself, not her sex work persona, because she had experienced more violence in her personal life than she ever had as a sex worker. Viv emphasised how normal male violence has become, and that we need to disrupt this normalisation. It is not normal, she emphasised, to fear for your life, fear your partner, to plan escape routes, to feel unsafe in your home. She spoke about how

her experience as a sex worker helped her reclaim her life, teaching her boundaries, consent, and how to demand respect. She spoke to the need to destigmatise sex work, to value the lives of sex workers, and stop victim blaming. She encouraged everyone to start challenging the normalised violence against women by using the hashtag ‘#NOTNORMAL’. She ended with a powerful call to attendees that it is up to us to build the community that we want; that we all have something to offer, whether it’s cooking skills, graphic design, art, money, or simply time.

The final speaker was Eleyna Simich, a human rights advocate with a focus on First Nations rights. The microphone stopped working as she spoke, so she encouraged everyone to gather round closer, making the moment of silence she opened with all the more powerful. Eleyna spoke of the way the media handles femicide, and how this has conditioned us to blame victims. She stated that violence can happen in any home, and that every woman deserves to live in fear or violence, or be blamed for their own death. She emphasised that it is up to us, and we all have the power, to create a world where no woman’s death is ignored or twisted. She ended by sharing the details of an organisation called Escabags, who create escape bags for people fleeing domestic violence.

After the speeches, Akyol encouraged everyone to stick around, talk to each other, cry, and heal. Despite setbacks, including supermarkets refusing to donate supplies and the police saying that hosting the rally by the ANZAC memorial was ‘disrespectful’, the rally was a powerful and heartbreaking tribute to the women behind the statistics, and an important reminder to say their names.

Purny Ahmed reports.

The latest NSW Bureau of Health Information (BHI) Quarterly Health Report, for the October-December 2024 period, has revealed that NSW Ambulance is struggling under the pressure of increasing demand, resulting in worsening response times.

The latest numbers from the BHI are record-breaking, with data indicating that NSW Ambulance managed 291,463 incidents and 391,370 responses, the highest number of any quarter since 2010.

The data has also presented worsening response times for P1As (high acuity and priority incidents) with only 62.6 per cent receiving an ambulance response within the clinically recommended timeframe of 10 minutes.

The president of the Australian Paramedics Association NSW (APA

NSW), Mr. Brett Simpson, commented, “The Government loves to complain about the cost of healthcare but refuses to invest in community-based solutions that provide patients early access to the care they need, keeping them out of the back of Ambulances and out of Hospitals.”

Mr. Simpsons added: “What this shows is that increases in staffing are not a silver bullet. If we can’t get the right care to our patients at the right time, then they will get sicker and sicker until their only option for care is an emergency department.”

“We are calling on the State and Federal Government to stop buck passing and start working on solutions. It’s not just better for our patients, it’s better for your budgets.”

James Fitzgerald Sice reports.

The University of Sydney (USyd) is among several Australian universities at risk of losing crucial research funding due to recent policy changes introduced by the Trump administration.

The Australian National University (ANU) was the first to publicly acknowledge the termination of nearly $1 million in funding for its terrorism and targeted violence research, deemed misaligned with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s priorities.

This move is part of a broader initiative affecting institutions such as Monash University, the University of Melbourne, the University of New South Wales, and the University of Western Australia. Affected researchers have received a comprehensive 36-point questionnaire from U.S. federal agencies, probing their involvement in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives, alignment with U.S. gender policies, and financial ties to countries such as China, Russia, Cuba, or Iran.

The administration’s focus on combating “woke gender ideology” has been cited as a rationale for these funding suspensions. Researchers have been informed that

projects perceived to promote such ideologies may not align with current U.S. government priorities, leading to temporary funding pauses.

Although no explicit funding cuts have been reported at USyd yet, growing concerns persist within the academic community about potential ramifications for ongoing and future research projects.

National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) USyd Branch President Dr. Peter Chen emphasised the union’s stance against political interference in research funding.

“The NTEU would like to hear from any researchers affected who have not yet reached out to us. The longstanding position of the NTEU is to reject political interference in research funding, especially where that funding has been allocated on the basis of expert assessment and review. We call on the leadership of the University to act to ensure research continuity in the case of any loss of funding support,” he said.

The Group of Eight (Go8), which represents Australia’s leading researchintensive universities, have expressed grave concerns about the implications of

these funding freezes. Go8 Chief Executive Vicki Thomson highlighted the potential impact on critical research areas.

“We are extremely concerned about the broader implications of the Trump administration’s policy, not only for the future of health and medical research, but especially regarding defence collaboration,” Thomson stated.

“Go8 universities are deeply engaged in collaborative activities with the US, especially through our defence initiatives and the AUKUS alliance.

“Our universities have enjoyed a longstanding relationship with the US and for every one of our members, the US is the largest research partner by far.”

She noted that Go8 universities collectively received approximately US$161.6 million in grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) during the 20202024 financial years, accounting for 88 percent of all NIH funding to Australian universities in that period.

She added, “Coming on the back of changes to Australia’s international education policy, which props up our university research effort, we are at a

critical juncture. Australia must double down on getting a seat at the table to access the world’s largest research fund, Horizon Europe. Associate membership to Horizon Europe – the EU’s €95.5 billion flagship research and innovation programme –will not only deliver important economic and social benefits, it will strengthen the Australian-European partnership.

“It’s now more important than ever that we get back to the negotiation table on the stalled Australian-European Free Trade Agreement” Thomson said.

A USyd spokesperson told Honi: “We’re carefully monitoring developments and working closely with the sector as we seek to understand potential implications for our research. We deeply value our international research collaborations and would manage any instances on a caseby-case basis in line with our codes and policies as required.”

As the situation unfolds, Australian universities are calling for urgent intervention from both the Australian and U.S. governments to clarify funding eligibility and safeguard research collaborations critical to national and global advancements.

On Thursday 20th March, Palestine Action Group (PAG) held an emergency rally at Town Hall after Israel broke the ceasefire and massacred over 400 people in one night.

Chair Josh Lees began with chants calling out Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Australian PM Anthony Albanese, and US President Donald Trump. Lees also chanted demands for Israel out of the West Bank, Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria.

Lees acknowledged that the protest was occurring on stolen and unceded Aboriginal land through genocide and invasion by the same government which supports Israel’s genocide. He described Tuesday’s bombing as “one of the worst massacres in the 16 months of genocide”, additionally preceded by a weeks-long blockade on the Gaza strip.

Lees explained that Israel did not intend to honour phase two or three of the ceasefire deal, and that the White House meeting between Netanyahu and Trump fantasised about a Palestine without Palestinians.

“This is what Israel has been doing to the Palestinians since 1948… spelled out by Israeli leader after Israeli leader for decades [and] Zionist leaders before,” Lees said.

Lees denounced the complicity of world leaders who provide cover for Israel and send shipments of weapons and bombs.

He spoke to the University of Sydney (USyd) management’s attempt to suspend an transgender international student after accusing them of writing pro-Palestine slogans on a white board, which would

then result in their deportation.

Lees also explained that PAG is launching a constitutional challenge against the antiprotest laws being passed in NSW with their first appearance in court on the 8th of April. This is in addition to the Greens and a few independents repealing them in parliament.

Lees also criticised the law which would see police issue move-on orders for anyone protesting near a place of worship, and face arrest and criminal charges. He said that “no place in Sydney has no place of worship” including Town Hall, where St Andrew’s Cathedral is situated.

Lees reiterated the broad coalition of climate, LGBTQI+ activists, and union movements’ support, saying that “if we can’t defeat them in the court or parliament, we will in the streets” and that “we will defy if we have no choice.”

Greens Senator and Deputy Leader Mehreen Faruqi greeted the crowd with Ramadan Mubarak and spoke to protesting last Ramadan when Labor had failed to condemn Israel and frozen UNRWA funding. Faruqi added that this year, Albanese and Wong “could not even bring themselves to denounce Trump’s plan to ethnically cleanse Gaza.”

She continued, “I thought surely there would be a red line for Labor, where they would wake up from their morality stupor… Palestinians had a few weeks of respite and I’m sure Labor patted themselves on the back.”

With reference to Albanese and Wong’s statements dabbling in “both-sideism”, Faruqi said, “I know I’m not supposed to

swear when I’m fasting but I know Allah will forgive me — what the actual fuck.”

She also identified Islamophobia as rife in the community, given the recent threats of a Christchurch-like attack towards two mosques.

Faruqi concluded by saying that Labor and Liberal only understand the language of votes, reminding voters that “these two parties will never see us as equals unless they are forced to, and we will force them too”.

Students for Palestine organiser and USyd Education Officer Jasmine Al-Rawi began by asking, “how many videos of dead children have to be shared around… how many more protests do we have to have to make our government listen?”

As Israel continues to raid the West Bank, arrest and torture Palestinian prisoners, and continue the genocide, Al-Rawi reiterated that Israel is able to act with full impunity. She noted that “Israel’s bombing is accompanied by a repression of activists in the West”, speaking to Mahmoud Khalil at Columbia University who “has been made an example of in the US”, as his arrest and possible deportation are due to “simply opposing US policy”.

Al-Rawi continued, “What we want is justice for Palestinians…they deserve to rebuild their homes in Gaza, the West Bank and across Palestine.”

Ahmad Abadla, a Palestinian from Gaza and activist at Palestine Justice Movement explained that the “Zionist regime never had any interest in ceasing fire” and it “does not attempt to hide its lust for more Palestinian blood and land.” He continued

by saying that Zionist ideology, “which our government and universities say should be protected from criticism” is “inspired by Nazism and Fascism”.

Abadla called out Albanese for saying Australia shares common values with Israel, arguing that the similarity lies in the “racism, Fascism and Zionism”, and that this is especially appalling coming from “someone who once rallied for Palestine”.

“These so-called politicians don’t even flinch when they see children massacred at the hands of their peers… Palestinians are not only being killed and genocided in Gaza but the truth has been killed there, here and everywhere,” Abadla concluded.

NSW police and riot squad were present, lining up between the protestors and the light rail platform. Police attempted to move the crowd to stand in the public square but due to a large turnout, the crowd spilled across George St.

The Adhan was also called and dates were offered to protestors breaking fast.

At the conclusion of speeches, Lees declared Palestine Action Group’s intent to return to more frequent protests, for which the crowd indicated its support. Lees said the next protest will not be on Sunday 30 March — which also marks Palestine Land Day — so as to not clash with Eid al-Fitr.

The next protest will be held on Saturday 29 March at Hyde Park, in addition to the Stop War on Palestine march from Sydenham Station to Albanese’s Marrickville office in Marrickville.

Photography by Valerie Chidiac

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following article contains the names and details of deceased people.

“I have not been given bottled water and have to drink the water from above the toilet. The water is warm or hot. This is disgusting and the sink is often filled with sick and other people’s saliva. The toilets are blocked and stink. (...) You can not get away from the smell.”

“When using my puffer I am meant to rinse my mouth after every use, I am sometimes not able to do this, as the only source of water [is] shared by up to 20 people between the three cell areas.”

These are the words of two Aboriginal women, Deanna and Simone, who submitted affidavits to the Alice Springs Local Court in February 2025. They were held as prisoners in the

To deal with prison overcrowding, new laws are being introduced to make it easier to contract private and interstate guards. New prisons and work camps in Holtze and Katherine are being planned. Reducing the number of people who are incarcerated is not on the political agenda, only increasing the capacity of the system is.

In Queensland, the number of children being held overnight in watch houses meant for adults increased by 50 per cent between 2022-3 and 2024-5. The New South Wales government has tightened bail laws for young people and limited the number of officials who can make bail decisions, meaning people will have to wait longer before they can be released. It appears to be the case that the competition to be the most ‘tough on crime’ will be an important feature of all Australian elections in the coming years.

Despite all this, many people forced to spend nights in conditions like those of the Alice Springs watch house have not been convicted of a crime at all; 40 per cent of prisoners in the country are awaiting a conviction or sentence. Increasingly, many of them, like Deanna and Simone, are women. Incarceration rates for women are at the highest that they have ever been,

watch house of the local police station for multiple months. The cells in the watch house are small, designed to hold people for only a few nights while they are under temporary arrest.

The prison system in the Northern Territory is broken: one in every hundred people in the Territory are in prison. Watch houses that are not fitfor-purpose are being used as overflow facilities. The newly elected Country Liberal Party’s policies will continue to worsen the crisis significantly. They have lowered the age of criminal responsibility to 10, made it more difficult to be granted bail, and given police more wide-ranging powers to enforce court orders.

and are rising quickly. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety estimates that 7090 per cent of women in prisons are victim-survivors of family, domestic, or sexual violence.

As has been the case for more than half a century, Australian First Nations people are the most incarcerated group of people in the world. They are 17 times more likely than nonFirst Nations people to be in prison in Australia.

In many ways, our society is becoming fairer, more equal, and more humane. Our prison system is not; and that is despite the fact that it has been a

recurring issue in Australian politics for decades. Why have a litany of Royal Commissions and law reform reports gone unheeded? Why has a harrowing series of tragedies not prompted change? Why has extensive media reporting on the broken state of Australian prisons not led to a corollary policy response?

The extent of discrimination and frequency of abuse in prisons in Australia is staggering, even when compared to countries like the United States. However, this is not inevitable. Being ‘soft on crime’ may be politically unpopular, but protecting human rights — especially of people who are unwell, unconvicted, young, or themselves victims of crime — need not be. It is easy to avoid thinking about what it actually means to send someone to jail, but it is imperative that we do. Without deep reflection on the state of our prison system and the way in which it has evolved, it is difficult to imagine reform occurring.

Although punishment in Australia plays a prominent role in our historical and political imagination, we have a selective memory. Children in primary schools are taught, in detail, about our convict past. They are taught that convict labour fueled the development of Australia’s agrarian economy in the first half of the 19th century. Often, they are even taught about the mistreatment of white convicts. For example, government approved school textbooks describe the use of harsh physical punishments, like public flailings and whippings, for convicts who refused to work or tried to escape.

In the 20th century though, our collective memory goes dark. Public punishments and open air prisons were replaced with the high walls of the modern penitentiary. The depictions of criminals serving their punishment that populated much of early Australian written and visual media disappear. It is not by chance that this coincided with a rapid increase in the Indigenous prison population.

Since the publication of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish in 1975, the way the modern prison system conceals physical, corporal punishment from the public eye has become well-studied. Visible punishments like public whippings created sympathy and admiration for convicts, and made the punisher, rather than the punished, appear as violent or primitive. Removing prisoners from populated areas and sequestering them in austere, walled environments created a scenario in which humanitarians and progressives supported horrific abuse as long as it was labelled as rehabilitation.

This is even more true in Australia,

where the prison system has always been highly segregated by race and class. Roebourne Gaol, in the Pilbara region in Western Australia, had separate cells for ‘Natives’, ‘Whites’ and ‘Coloureds.’ Women, who are often invisible in the history of imprisonment, were given more meagre rations than men. Cells that housed women at Fremantle prison in the 1970s were declared to be “much too small for accommodating any males.”

The records of prisoners’ experiences that do survive are nearly entirely white and male. As historian Mark Finnane put it, “there remains a long period (c 1900-1960) when the administration and the experience of Aboriginal imprisonment is little known.”

Even in general, there are very few popular historical works that renarrate Australian history from a First Nations perspective. Equivalent works from other countries, like the New York Times’s The 1619 Project, which centres slavery and racism as the dominant organising forces of American history, benefited from there being far more archival material to draw on in the United States than there is in Australia.

For example, the idea that the mass incarceration of African Americans in the United States was driven by the attempts of Southern state governments and businesses to substitute the labour of enslaved peoples with that of prisoners is an increasingly popular and politically powerful one. Shane Bauer’s American Prison, a book that argues for this thesis, was bought widely, and was cited by both Barack Obama and the New York Times Book Review as one of the best books of 2018.

Of course, it is true that slavery and forced labour played a comparatively more significant role in the history of the United States prison system than in Australia. However, the link between slavery and prison in Australia is important and rarely discussed. There is a reason that states with lower white convict populations like South and Western Australia imprisoned more Indigenous Australians earlier in time.

For example, Rottnest Island, off the coast of Perth, was the site of a prison and forced labour camp where Indigenous Australians were held. Over the period between 1838 and 1931, one in every ten prisoners that were imprisoned there died, some as a result of disease outbreaks, some as a result of torture or summary execution. Mostly, prisoners were sent to the island when they refused to partake in forced labour elsewhere in Western Australia. A series of “Protection” or “Welfare” acts in the state enslaved Aboriginal people in

the pearling industry, on farms, or as domestic servants. According to historian Neville Green, those who refused to work elsewhere were sent to Rottnest, forced to quarry salt and limestone, where the punishments for non-compliance were brutal. Western Australian Governor Arthur Kennedy himself explained that, partly, the logic of the island prison was that without it, people in Perth would see Indigenous prisoners “chained and manacled in the most inhumane manner.” The institutionalised racial segregation in the prison system had the convenient effect of foreclosing any sympathy that white, urban populations may have had for enslaved Aboriginal people.

The gratuitous, violent, and psychologically abusive treatment of Aboriginal people in custody has never stopped. It has been facilitated by enduring colonial logic and attitudes amongst those who organise and work in Australian prisons. John Roy Stephenson, a man who worked in Australian prisons between 1930 and 1970, wrote a memoir recounting his experiences. Many of the interactions described in the book reveal the satisfaction he felt in exercising unchecked power over Aboriginal prisoners at the Stuart Creek Prison in Townsville. Having unilaterally and summarily convicted a group of prisoners of their third minor offences committed in custody, Stephenson took delight in informing them that the punishment would be an additional fourteen months of hard labour, and that, under the Queensland Prisons Act, they had no right to appeal the decision that he had made. In his own words, the subsequent resentment the prisoners felt towards him “pleased [him] mightily.”

Why has our prison system been so unaffected by progressive thinking that has, in many other ways, changed our society for the better? It is true that much of the prison reform that is needed in Australia may not be politically palatable. However there exist many policy changes that would still be both popular, and make the lives of prisoners better. Ahead of both the 2008 and 2012 elections, Obama endorsed certain popular, reformist criminal justice policies, like reducing the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offences. The so-called “smart on crime” policies that Eric Holder’s Department of Justice implemented in 2013 were widely supported. They included expanding compassionate releases and moderating sentencing guidelines for minor drug crimes. Perhaps an equivalent Australian policy would be abolishing our privately run prisons.

The largest prison in Australia is the Clarence Correctional Centre in Grafton. It is owned and operated by Serco, a British multinational defence, health, and criminal justice contractor, listed on the London Stock Exchange.

Private prisons have not been a political flashpoint in Australia, but polling suggests that a large majority of Americans oppose the privatisation of prisons. It is hard to imagine the same would not be true here, especially given that most of

our private prisons are run by foreign companies. Private prisons are also more expensive for the taxpayer: Serco has previously been embroiled in controversy for overcharging the British government for criminal justice services. In addition, private prison operators are shielded from public accountability. Large portions of the contracts between them and state governments are redacted. In the United States, many of those contracts include ‘occupancy guarantee’ clauses, whereby governments are required to pay fees to prison operators if the inmate population falls below a certain number. It is unlikely that arrangements like that exist in Australia; but even if they did, we would not know about them.

Most Australians consider private prisons to be a uniquely American phenomenon, however, it is Australia that has the most privatised prison system in the world. In 2018, 18 per cent of prisoners in Australia were held in private prisons, compared to only 8 per cent of prisoners in the US. What we do know, though, is that, according to a 2018 report produced by Queensland’s Crime and Corruption Commission, there is comparatively more violence and corruption in private prisons than public. Anecdotally, prisoners report that commissary goods are more expensive in private prisons, visiting hours or phone calls are harder to arrange, and complaints fall on deaf ears more often.

Governments taking control back from private prison operators would likely be both politically popular and meaningfully improve the lives of 18% of prisoners in Australia. Some states are starting to do this; the New South Wales government recently decided to not renew its contract with GEO Group Australia for the management of the Junee Correctional Centre. However, it needs to happen more quickly. There are other reforms of this nature, like giving prisoners basic workers’ rights or making the market for healthcare provision in prisons more competitive, that would not kill the election chances of a party supporting them.

The reason these reforms have not happened is a lack of empathy and consideration for prisoners. The history of prisons in Australia is one of turning a blind eye to the experiences and voices of those in them. Whether by entrapping them on an island or behind closed walls, the effect has been to dehumanise and abstract the lives of those we imprison. This problem continues today. Media reporting on prison usually takes the form of either: a) reporting on deaths in custody and serious incidents of abuse, which are often portrayed as aberrations; or b) reporting on high-level, abstracted policy issues like rising incarceration rates. These are both important and necessary forms of reporting that must continue. However, more attention should also be given to the frequent denial and violation of basic rights that happens daily in Australian prisons.

For many prisoners, chronic pain, thoughts of self harm, and the threat of sexual violence are facts of life. By not describing these issues in plain terms, we allow them to continue. We allow many Australians to conceive of imprisonment as mostly humane and justified; as fulfilling its function of taking away certain freedoms in a precise and orderly manner in order to rehabilitate criminals and protect the rest of society. Realising that a sentence of imprisonment is a sentence to unchecked and horrific abuse is the first step to reform.

A study conducted by advocate and lawyer David Heilpern in 1998 estimated that roughly a quarter of prisoners in the country had been sexually assaulted in prison. Young and gay prisoners are especially at risk, and many victims will contract sexually transmitted diseases. When people in Australia are sentenced to imprisonment, much of the time, they are being condemned to the lifelong trauma, paranoia, dissociation, and amnesia associated with being the victim of rape.

For example, 50 per cent of prisoners in Australia have a disability. According to a Human Rights Watch report, compared to prisoners without disabilities, they are more likely to be assaulted, and are more likely to be placed in solitary confinement. Many of them do not receive adequate healthcare. Their medications are often stolen by other prisoners, who sometimes force them to regurgitate tablets after they have taken them. Mentally ill prisoners are especially at risk. In Australia, forensic patients, who are deemed not fit to stand trial for criminal charges laid against them, are still often sent to prison. Other jurisdictions like New Zealand prohibit this, and rightly so: if someone is so unwell that we cannot hold their criminal actions against them, they are surely too unwell to be placed into one of the most distressing environments one could dream up. Often placed in solitary confinement for more than 22 hours a day, and faced with indeterminate wait times to access healthcare services outside of prison, many prisoners self harm or take their own life. Coronial inquests and royal commissions have regularly drawn attention to these problems, but little progress has been made. Prison guards are often former police, military, or security officers, and do not have remotely enough training to deal with mentally ill inmates. Prisoners speaking to Human Rights Watch recounted how they were ignored and abused by guards while in solitary confinement. “I was sobbing, they didn’t respond. They opened up the grate [in the cell door] and laughed at me. I swallowed batteries in front of them,” one said.

There is also a crisis of sexual assault and violence in Australian prisons. It is chronically underreported in the media, and difficult to research.

In 1991, then New South Wales Minister for Corrective Services Michael Yabsley commented that prison rape was both “inevitable” and a useful “detterant factor” against offending. Despite much public outrage over the comments at the time, no substantive reforms have been made since then to reduce sexual violence in prisons. In the United States there is the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003, which established a “National Prison Rape Reduction Commission” aimed at increasing support for prisoners, reporting of assaults, and awareness of the issue. There is no state or federal equivalent policy in Australia.

Our national ignorance of prison is shameful. State governments are in the process of sending even more people, including many children, to jail. In some places in Australia, more than one in every hundred people are in prison. We have an obligation to understand what that actually means, to listen to the stories of prisoners, and to broadcast their experiences.

We must reckon with the fact that human beings in prison are subjected to the most deplorable crimes every day and that most of the time, no one cares or intervenes. If voters and politicians are intent on incarceration being the panacea for our many social maladies, then they should at least be honest about its consequences.

Welcome back to another federal Budget! At the forefront of everyone’s minds and at the ‘front and centre’ of the Budget is the overwhelming cost of living crisis. Let’s take a deep dive into how the Labor government has aimed to mitigate the effects of increasingly expensive groceries, give renters some relief, combat energy bills, cheapen medicines, strengthen Medicare, and protect workers. This year’s budget has some positive elements, but is still underdelivering on Albanese’s promise of a “fair go for Australia”.

Australia has been under the Labor government for the better part of three years, up to their fourth budget. With the federal election coming up, Labor has only $1.5 billion allocated between 2025-2026 for “decisions made but not yet announced”; comparative to previous allocations of up to $10 billion, this suggests Labor has made the strategic decision to slow-rollout almost all their election policies before or during the Budget.

Labor plans for “all 14 million taxpayers” to receive another (tiny) tax cut in 2026 and 2027, on top of the tax cuts that have been rolling out since 1 July 2024.

Observing new personal tax rates, the main changes are in the $18, 201 - $45,000 wage bracket which experienced tax rates of 16 per cent from 2024-2025 and 2025-2026, which are to reduce by one percentage point to 15 per cent from 1 July 2026 and then 14 per cent from 1 July 2027.

The average tax cut is expected to be around $43 per week in 2026-2027 and around $50 per week in 2027-2028.

Labor aims to offset “dangerous bracket creep”. Bracket creep occurs when wages are adjusted to account for inflation. When people in lower thresholds move up, they end up in a higher tax bracket which is not offset by their new wage. Consequently, people end up having less purchasing power.

These new tax cuts mitigate this by lowering average tax rates for all taxpayers, namely low and middle income earners. With tax cuts, workers on average are expected to pay $30,000 less tax from 2024-2025 to 20352036, relative to 2023-2024 tax settings.

creep and skirted around the question. He repeated that although it is a “modest cut, in combination with other policies it will benefit Australians”. It is an absolute shame that Labor has latched on to marginal tax cuts and refused to deliver appropriate cost of living mitigation for the millions of vulnerable Australians on Centrelink.

The Government has not increased rates of Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) for renters. Greg Jericho, Chief Economist at the Australia Institute, tells Honi that “We still seem very much stuck in the 1980s and 1990s belief that renters aren’t a big part of the voting public.” This rings true in the face of the Budget’s lacklustre energy towards renters rights, which decrees that it is “moving towards limiting rental increases to once a year” through A Better Deal for Renters, with no concrete measures, performance indicators, or financial statistics to solidify neither the claim nor the process. Alongside no increase in financial assistance, there is also no proposed cap on excessive rent increases, with the ACT being the only jurisdiction in Australia which caps rent increases to a maximum of 10 per cent above the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for Canberra.

This Budget severely lacks any proposed reform or financial alleviations for student accommodation, which is notably expensive and unstable as private companies hold a monopoly over the commercial student accommodation sphere and prices have increased significantly post-COVID.

As housing and renting prices continue to increase, renting is no longer a step towards home ownership but often a permanent housing situation for millions of Australians.

The Labor party should aspire to provide policy that ensures renter’s stability and quality of life, if they want to lock in the ‘renter vote’ this election.

Honi found it frustrating that the tax cuts are applying to all voters equally, instead of being scaled by income and targeted to low-income earners. When questioned by journalists as to why these tax cuts have been implemented when the budget is absent of any measures to increase Centrelink payments (such as JobSeeker and Youth Allowance) Chalmers stated that the tax cuts are to solve the problem of bracket

The Labor Government has promised $1.8 billion to extend energy bill relief to the end of the year for every household and small business, on top of the nearly $5 billion of bill relief being delivered so far. Households and small businesses will receive two $75 rebates off their electricity bills through to 31 December 2025.

The Labor Government will provide $2 billion to recapitalise the Clean Energy Finance Corporation to invest in renewable energy, energy efficiency and low emissions technologies. The Government has already provided funding for this measure starting from 14 February 2025.

Mehnaaz Hossain and Charlotte Saker report.

Let’s See How Well They’ve Done…

Our Beloved PBS

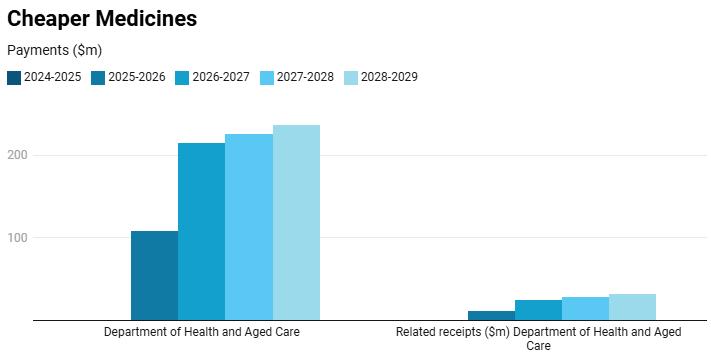

Labor has promised $1.8 billion to list more life-changing medicines on the Pharmaceutical Benefits scheme (PBS).

The Government will provide $784.6 million over four years from 2025-2026 with $236.4 million per year ongoing, to lower the (PBS) general patient co-payment from $31.60 to $25 starting 1 January 2026. This measure extends from their plan to secure cheaper medicines from 2023 and 2024.

Labor will also allocate $690 million to lower the cost of PBS-listed medicines from $31.60 to $25, which the Coalition has also agreed to uphold.

Does our Government Even Medi-care?

The Labor Government promises $7.9 billion to increase GP bulk-billing in Australia. They plan for 9/10 GP visits and 4,800 practices in Australia to be fully bulk-billed by 2030. This is the largest single investment in Medicare since its creation in 1984. The Coalition has promised to match the Budget spending on bulk billing, meaning this policy will benefit all Australians regardless of the federal election outcome.

The Government also aims to spend $657.9 million to open another 50 Medicare Urgent Care Clinics, bringing the total to 137 nationwide, with an additional $1.8 billion to fund public hospitals.

Starting on the 1st of July 2024, the Government will increase the Medicare levy low-income thresholds by 4.7% for singles, families, and seniors. This change will ensure that over one million Australians on lower incomes remain exempt from paying the full Medicare levy or are subject to a reduced levy rate.

Patient experience is still likely to be subpar; the critical GP shortage, which the Labor Government has failed to address on a structural reform level, has resulted in understaffed clinics and overworked GPs. Also in the realm of healthcare, dental remains completely inaccessible as it lies outside Medicare; this remains an urgent issue which Labor has yet to propose a concrete solution for. And despite critical psychiatrist shortages due to medical union strikes, this years Budget — to Honi’s severe disappointment, albeit not our surprise — was utterly absent on any policy to combat the mental health crisis.

The government aims to help consumers get a better deal at checkouts. Labor is boosting funding to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission by $38.8 million to challenge deceptive pricing practices in the supermarket and retail sector. Finally!

They are providing $2.9 million to support fresh produce suppliers to enforce their rights under the Food and Grocery Code of Conduct. The government has

mandated the code and introduced multi-million dollar penalties if supermarkets breach the code.

I feel a zap through my veins every time I tap my card and see those ridiculous surcharges. Society’s over-reliance on card transactions is costing us. I buy an $8 sandwich, and suddenly I’m being charged $8.34. Give me my 34 cents back, this stuff builds up! Seems like the government will do something about it, but at the moment it’s a promise of planning and preparation, as opposed to actual implementations.

The government is “prepared” to address excessive card surcharges by banning debit card surcharges, subject to further work by the Royal Bank of Australia (RBA) and safeguards to ensure both consumers and small businesses can benefit from lower costs.

The government will collaborate with state and territory governments to ban unfair trading practices and strengthen regulators’ ability to act against businesses that fail to uphold consumer guarantees under Australian Consumer Law.

Beyond tax indexation, there is little change to welfare. Treasurer Jim Chalmers has claimed that “tax relief for working people, strengthening Medicare, cheaper medicines, energy rebates, and slashing student debt” are the government’s main avenues for boosting social support. However, it’s clear that while there is plenty on cheaper medicines and Medicare, information on Centrelink is scarce. The Budget notes that Services Australia is expected to grow in response to rising demand, driven by an ageing population, shifting demographics, and new support measures like paid parental leave, which has resulted in a 35% increase in Medicare and Centrelink claims since 2012. What we do know is that between 2023 and 2024, Services Australia staff completed 1.2 million Centrelink claims and Medicare-related activities — yet the detail beyond that is limited.

To help close the gap amongst First Nations Australians, the government is investing $1.3 billion over six years from 20242025. This adds to previous investments that deliver services and infrastructure for First Nations Australians, including the Northern Territory remote housing agreement and the $706 million Remote Jobs and Economic Development Program. They are also giving $3.4 million over three years from 2025-2026 to establish a place-based business coaching and mentoring program for First Nations businesswomen and entrepreneurs.

Albanese’s government is also boosting Indigenous Business Australia’s Home Loan Capital Fund by $70.9 million over two years from 2025-2026 to increase home owning opportunities for First Nations people.

Additionally, the government is reducing the costs of 30 essential products, including milk, fruit, vegetables and nappies in stores in remote First Nations communities to improve food security and ease the cost-of-living crisis.

The government plans to provide $842.6 million over six years from 1 July 2025 towards Northern Territory Remote Aboriginal Investment. They aim to improve health, safety and education outcomes. 2024 had a similar budget of $4 billion to improve overcrowding in remote area housing in the Northern Territory and $2.4 billion toward education, health and jobs. Labor is simply continuing on from that.

Non-compete clauses are contractual terms which restrict employees from engaging in competing activities — such as pursuing higherpaying work in the same industry — after their employment ends, which restricts their financial mobility and autonomy. This Budget is removing non-compete clauses which more than 3 million Australian workers are covered under, in industries such as childcare and construction. It will apply to workers earning less than the high-income threshold in the Fair Work Act, which is $175,000. This is spurned by the Treasury’s Competition Review being informed of the misuse of noncompete clauses with vulnerable people, including minimum wage workers being sued by former employers for switching jobs.

Allowing workers to maximise their earnings will also result in a “4 per cent wages benefit” of approximately $2,500 per year for the average worker.

This is a proposal that is disappointingly most likely contingent on re-election; following consultation and passage of legislation, the reforms will take effect from 2027, “operating prospectively to give businesses and workers time to adjust”. Labor has had the political capacity to enact these changes — particularly given they are enforcement-related as opposed to strictly fiscal — in the last three years. The announcement of electioncontingent benefits for workers under the high-income threshold, many earning minimum wage, only towards the end of their term, reads as an electorally strategic move rather than a genuine economic solution for workers from a so-called workers rights party. Overall, Labor has promised some degree of relief for Australians. However, this Budget ignores crucial policy areas and staunch measures to significantly reform key issues — such as growing cost of living pressures on the working class, the GP shortage, mental health and excessive rental increases — are shamefully absent. This year’s budget is filled with incremental measures, leaving room for the Labor party to, in the lead up to the 2025 federal election, dangle policy in front of us like a carrot.

Read full article online.

In the 2025-26 budget, the Albanese government has taken vanishingly few measures to directly and effectively relieve students who are under stress due to the cost of living crisis, international student caps, and HECS-HELP debt. When it comes to education, Jim Chalmers seems to be in a creative drought; he’s used ctrl+C a few too many times in this year’s budget and it really shows.

The government has declared it will slash national collective student debt by 20 per cent with effect on the 1st of June 2025, before indexation is applied.

This is set to wipe $16 billion from outstanding student HECS-HELP loans. The government has not announced any measures to address the increased cost of tuition itself, an impact of the Liberal government’s Job Ready Graduates package and a direct cause of the current HECS debts which have ballooned to $74 billion dollars in outstanding national debt. However, this measure is not new: the government announced it in December 2024, and has not adjusted the measure in this budget from what had previously been released. The government has also decided to lift the repayment threshold for graduates from $54,000 to $67,000.

In a decision that Honi would call questionable, the government has announced that by 2050 it aims to have 80 per cent of the working population with a tertiary qualification. This is an increase from 77 per cent, the current rate: a spokesperson for Jason Clare, The Minister for Education told Honi that this increase was “ambitious target”. The budget aims for “a rise on the previous year” and was unchanged from Chalmers’ last budget. The measure seems counterproductive for the government given the crippling HECS debts that 3 million students have incurred as a result of degrees undertaken, which have led to the Labor government repeatedly wiping portions of student debts. In past years, the government cut indexation rates from 7.1% in 2023 to 4% in 2024, but this has clearly not had the desired effect on the student populace.

Rather than removing the changes to HECS fees that were introduced by Scott Morrison in the 2021 Job Ready Graduates program, Chalmers has decided to put a bandaid on the gaping wound of student debt as a substitute for making education affordable — or better yet, free. Chalmers, as someone who would have benefited from free university as enacted throughout the 1970s and 1980s, has a curious method of addressing affordability of tertiary education. This is only the latest in a series of attempts by both Labor and Liberal governments to fix the problem of students’ tuition fees. But to make up for it, Chalmers will do his best to make sure more and more students get sucked into the financial haemorrhage of HECS-HELP loans.

Thanks a lot!

Angus Fisher, the USyd Sydney Representative Council President, commented, “The 20 per cent cut to HECS debts is a huge win for students… What this shows is the power student unionism has in pushing the

current government to do good, as this was a result of the SRC and NUS being involved in the accords process.”

He added, “In future, student unionists can further push this government to do even better for students, for measures like free education, fully paid placements, and supporting student housing. What is certain is under a Dutton Liberal government we don’t get this policy and weaken the power of student unionists. Students should be putting the Liberals last.”

A spokesperson for Jason Clare said to Honi that “We have listened to students’ concerns and we have reduced HELP and other student debts by over $3 billion by changing the way that HELP and other student loans are indexed.”

They continued, “The Government will also provide additional Needs-based Funding for academic and wrap around supports to help students succeed, including scholarships, bursaries, mentoring, and peer learning. Universities will receive demand driven Needs-based Funding aligned with the number of students they enrol from under-represented backgrounds to deliver this.”

For international students, the Labor government has twisted itself in knots trying to exploit students for cash and simultaneously reduce their alleged pressure on Australian housing. While enforcing a strict student cap that will have significant effects on international students, who comprise 46 per cent of enrolments at the University of Sydney, the government has also announced a performance target to increase the number of students enrolled in offshore education and training delivered by Australian providers from the rate in 2024-2025. International students are encouraged to study with Australian tertiary institutions, boosting our economy, only so long as they do not take up limited housing resources.

Chalmers has introduced medical training opportunities for First Nations students, focusing on primary care, namely general practitioners. The government is using this measure to increase representation of First Nations individuals in the medical field, implementing $35.6 million over four years to introduce 100 new medical Commonwealth Supported Places (CSPs) for First Nations medical students. These places will be introduced from 2026 and continue annually, and will be raised to 150 CSPs from 2028. While this sounds like a good measure, it isn’t exactly new. The same measure had been previously introduced and targeted specifically at First Nations regional students, which then expanded to include First Nations students from metropolitan areas. These students will be allocated CSPs through a competitive process moderated by the Department of Health.

The government has also announced a measure to establish 100,000 permanent free places at TAFE, starting from 1st January 2027.

But the Treasury has grand plans for tertiary education. Firstly, they intend to establish a so-called Australian Tertiary Education Commission, which will apparently “guide tertiary education reform over the long-term.” The ATEC will start operating in an interim capacity from 1 July 2025,

and permanently from 1 January 2026, but performance measures have not been announced for this yet, which indicates that this shiny new measure has no real substance. The performance measures will not be developed until after ATEC has been permanently established, which would be a little unfortunate if ATEC did not run as smoothly as the Treasury hopes it will. Secondly, the government intends to create a new “Managed Growth Funding system” that will “guarantee a place” to low-SES and disadvantaged students. This system grants universities the ability to negotiate for a higher amount of funding through which to allocate CSPs. Comparatively, the current system has a ‘maximum basic grant amount’ (MBGA) which means that, although domestic students are entitled to CSPs, the university can choose to reject an enrolment application rather than exceed the MBGA. The MBGA is a specific amount of money that the Treasury distributes between universities which they then use to allocate CSPs. The MBGA will be ousted in favour of a system that theoretically awards grant money based on the number of students enrolled at a university. That grant money is now a negotiable figure, based on an over-enrolment buffer where “a small proportion of additional students” can receive CSPs in addition to the allocated figure. For a measure that is supposed to “reform” our education, it seems wholly unremarkable.

Meanwhile, Chalmers has copied many measures that were already mentioned in previous budgets, as well as completely overlooking issues of importance to the tertiary education sector. The National Student Ombudsman, which was announced in the 2024-25 Budget, has been re-declared in this year’s budget, for no apparent reason other than Chalmers’ deep desire to appear to create change while sticking with his old and familiar policies. The NSO’s role is to investigate student complaints regarding issues which include sexual assault, racism and homophobia. It began accepting these complaints in February 2025, so Chalmers has tried to pull the wool over our eyes by marketing it as something new. Nice try.

Last but not least, the Labor government has wiggled AUKUS into the tertiary education portfolio too. The government has propelled a Nuclear Powered Submarine Program, using “education pipelines” to “support the nuclear workforce.” In a continuation of policy from 2024-2025, the government aims to allocate CSP funding specifically so that students can “support sovereign workforce development” by studying in this program. In 2024 all of the CSP allocations for this program were achieved. While the USyd community have continuously condemned AUKUS, this program seems like a wildly ill-judged attempt to use students as resources for a program that many students vehemently oppose.

This year’s budget is by no means impressive, nor can it be called original. Chalmers has reiterated a host of measures that had already been announced in the vain hopes that his lacklustre treatment of the tertiary education sector, and introduced a few measures which might see some changes for students. Can we call it a good budget? Nope. But will we be here again in October for a second budget after the election? A solid maybe.

Ellie Robertson is a reoffending hater of the system.

Disclaimer: The use of the word ‘offender’ is used in the assumption that the incarcerated people being discussed in this article were deemed guilty. Of course, this is not always true when it comes to our criminal justice systems. However, for the case of the article, I have used this word to ensure it reads well, and is streamlined in wording.

The criminal justice system (CJS) has been a system that has existed in many forms for thousands of years. The way in which both sentencing and punishment have changed throughout time begets much curiosity from criminologists. One place in particular that has caused debate amongst experts and amateurs alike is the prisons based on Scandinavian Exceptionalism. It has bred many discussions on the relationship between these styles of prisons and how they can be implemented into Western society for a less retributive space. It can safely be said that there are both benefits and limitations to implementing a Scandinavian-style form of justice into Australian prisons, but the main intersection of how the government deals with socio-economic problems, such as homelessness and poverty, is a crucial factor in the issues that would arise.

‘Scandinavian Exceptionalism’ is known to focus on reformative and positivist ideas surrounding punishment.

From its open-spaced architecture to personalised treatments for prisoners, these styles of prisons focus on the ways in which the incarcerated can get back on track to being integrated into society. The actual architecture of the prisons is able to adapt the experience of those criminalised and alter the effects of their punishment in many ways.

According to a study by Yvonne Jewkes, there are two types of architectures: of harm, and of hope. In Western society, retributive foundations of punishment are set at the forefront of priority when it comes to punishing offenders, and prisons are built on the basis of an ‘architecture of harm’. This design implements a space of dehumanisation and degradation, putting forward the ideology that offenders do not deserve to be treated like humans and don’t deserve a comfortable life. These spaces consist of characteristics such as no windows, concrete walls, uncomfortable surfaces, and constant surveillance, leading to an immense feeling of surveillance that provides offenders with enough fear of suffering to supposedly prevent them from reoffending. In contrast to this, the ‘architecture of hope’ is the creation of open-spaced rehabilitative punishment based on the equality of all.

Scandinavian Exceptionalism tends to create a space where offenders are able to express their hobbies and interests in much more hospitable and comfortable conditions. Focusing on the rehabilitation of the offenders theoretically provides them with the skills and experience to reintegrate back into society or their community. Because Scandinavian countries have some of the lowest recorded crime rates in the world, it gives rise to questions surrounding the implementation of those values into the Western world and how it would affect the CJS in that space.

Incorporating a humane prison system in Western society would be a very big process as our societal views collectively show a desire for more retributive punishment; people want offenders to be treated with the ideology of “an eye for an eye” to ensure there’s some form of justice for the victims. The factors between Western society and Scandinavian countries that differentiate the effectiveness of this Exceptionalism consists of issues like overpopulated prisons, the higher levels of offending and reoffending, overrepresentation of minority groups in prisons, and the relationship between homelessness and offending rates. These factors stem from systematic issues that are supported by the CJS in the Western world.

Specifically looking into the issue of homelessness, a widely debated issue amongst criminologists is the prominence of how poor living conditions and the lack of support for homeless people correlate with crime rates. As a general statement, a humane prison may assist in some aspects of the re-offending rates, however it would be a much more beneficial action to sort the issue from the root cause of the problem. A study regarding the relationship between accommodation and reoffending in 2012 showed that approximately 60% of the participants (offenders who have been incarcerated) said that having support in the aspect of accommodation or living situation would assist in the prevention of reoffending. This statistic proves that there is an underlying issue with which prisoners link their reoffending with the homelessness crisis.

When offenders leave their time in incarceration, it is on their record permanently; records that both landlords and workplaces have access to. With this criminal record, it becomes difficult to find a home to rent or a job to be able to assimilate with ease. This is a reflection on how Western societies, and their perspective on retributive justice, view

a person with previous involvement in the justice system. Found in a study consisting of reoffending incarcerated people in 2012, 64 per cent of the participants reported that the factor of safe and affordable accommodation and living support would be beneficial to ensure a decrease in reoffending rates. At a very low 20 per cent reoffending rate compared to Australia’s 53.1 per cent as of 2022, Scandinavian countries seem to have characteristics in their rehabilitative punishment that work in filtering out disparity and treating prisoners as equals, to allow them to continue living with basic human rights after their sentence.

The ideal situation when speaking of the Scandinavian Exceptionalist perspective is that the Western CJS would incorporate this approach to punishment to reflect the positive impact it’s had on places like Norway. Nevertheless, there are various issues that prevent the change from taking place. In 2022, the imprisonment rates in Australia were at a high number of 200.9 people per 100 thousand adults; this means approximately 330 thousand were incarcerated in 2022 alone. With huge-scale imprisonment, Australia’s overpopulation in prison is almost too overwhelming to alter or change wholly without complete abolishment of the policing and punishment system. Therefore, the problem of insufficient support for homeless people, specifically looking at ex-prisoners, needs to be funded and focused on by the Government as a measure to see progression in the decrease of reoffending rates.

The issue with Australia’s current measures is that instead of going down the route of subsuming some beneficial aspects of Scandinavian Exceptionalism, there has been a defunding and abolishing of support systems for homelessness after returning to society. A small-scale example of this can be seen in the termination of the Reintegration of ExOffenders (REO) program, subsidised by Housing Tasmania. With 19 per cent of male and 15 per cent of female prisoners having no accommodation arrangements within weeks of the run up to their release, it forces these ex-offenders to reoffend as a means of survival.

Many prisoners will reoffend simply to get some form of accommodation. To illustrate, Tony Bull (an ex-prisoner) who has been periodically in prison throughout his life, stated “It doesn’t take too long before, you know, you’re looking at prison as being a better option”. This idea of reoffending to have a roof over your head produces a speculation on the notion that having nicer and more humane prisons in a time of an economic crisis would do the opposite as the Scandinavian countries have seen. Norway in recent years has only seen six in ten thousand people per year homeless, compared to Australia’s 48. Accompanied by this very low figure of homelessness, it is understandable that Norway (and other Scandinavian countries) have lower reoffending rates as at least one issue surrounding the welfare of citizens has somewhat adequate policies and support surrounding it.

Incorporating the Scandinavian Exceptionalist characteristics into our Western CJS runs the risk of a potential increase in (re)offending. This is because the current retributive prison systems are used as a means of deterrence to those who are thinking about committing crimes. If the prisons were known to have open-spaced living, good food, time, and space to pursue hobbies and a means of living more comfortably in a place free of judgement, there is a possibility that people living in worse conditions — especially in the recent housing crisis — will commit crimes to be taken away from poor living conditions and poverty. The way to resolve this in prisons and the state of reoffending is not to avoid giving prisoners basic human rights, but to ensure that the greater population has better access to livable conditions to avoid reoffending in the first place. The problem we’re facing is not the offenders themselves, but the lack of care and support given by the government in the face of a cost-of-living crisis.

Clearly, the incorporation of Scandinavian Exceptionalist characteristics in Australian prisons would assist in decreasing reoffending rates, when it is accompanied by more adequate support for low socio-economic groups. Scandinavian Exceptionalism can be impactful in lowering Australia’s high reoffending rates, but this can only be achieved in a place where governments put heavy focus on funding and fixing the root causes of the high crime rates.

With more funding and a strong focus on ensuring that Australia’s prison systems are rehabilitative, the Australian government has to, first, approach new policies to fully support vulnerable groups, not only have knee-jerk reactions when crimes occur.

system.

Not long after the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, when average-income Australians were still facing the concentrated economic repercussions of lockdown while millionaires almost doubled their income, American politician and activist Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) wore a white gown with the red bold letters “tax the rich” to the Met Gala. After disrupting the annual event celebrating the elite and uber-wealthy, Ocasio-Cortez released a collection of “tax the rich” merchandise; tees, mugs, stickers and tote bags, all made by unionised workers yet ostensibly profiting her political campaign. It received both controversy and praise. Some criticised AOC for her distasteful hypocrisy. Others praised her for bringing awareness to such political issues in elitist spaces. She was critiqued and celebrated. To me, this signifies the inevitable contradictions of glorifying anticapitalist rebellion in our capitalist economy.

Mark Fisher, in his novel Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative?, describes the process of absorbing activism into the system it critiques as circulatory. In Fisher’s Capitalist Realism theory, he explores capitalism as a totalising structure which commodifies rebellion, until activists feel as if there is no escape from the larger system at play. He quotes a phrase attributed to Frederic Jameson and Slavoj Žižek, which summarises the cynical disillusionment with the commodification of anticapitalism: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

This probes the question: can glorifying anti-capitalist rebellion prove to be transformative in an age of endless commercialisation?

When Luigi Mangione was arrested for allegedly shooting the UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in late 2024, netizens were quick to sympathise with his struggles dealing with the American healthcare system, as news headlines labelled him the ‘anti-capitalist crusader’. Gen Z, in particular, heroise Mangione with the viralised hashtag ‘#FreeLuigi’.