13 minute read

Reminiscences of Sargachhi

Sri Ramakrishna said, “Oh no! This also is a path; but it is akin to entering a house through the backdoor [traditional houses had a backdoor for the scavenger to enter and clean the privy].”

I have witnessed true devotion at my premonastic home — it’s not something artificial or contrived. We had the tradition of worshipping Govindaji [Sri Krishna] at home. Right from daybreak, the womenfolk were busy with the service of Govindaji. One person would be plucking flowers, another would be making a garland, and someone else would be cleaning the utensils. It seemed Govindaji was living in the house — exactly like a revered elderly relative residing at home; everyone was alert to taking the utmost care of him. This is called worship.

Advertisement

Just see what a great scholar Swami Vishuddhananda Maharaj is! [8th President of the Ramakrishna Order] And yet he constantly keeps calling on the Mother. Swami Shantananda too is experiencing great bliss by calling on the Mother.

You will learn many things about jnana yoga in the Panchadashi. But you will see that finally only three ideas have been discussed — the five sheaths, the Charioteer or the Atman, and the three states of being (avastha-traya). Liberation can be attained by discrimination about the five sheaths. The sadhaka has to reject these sheaths intellectually. For example, he discriminates thus: hunger, pain and injury belong to the body, strength and weakness are felt because of the vital force, irritation caused by abusive words pertains to the mind, and so on. He has to reject all these as not his real self. This intellectual exercise is a part of jnana yoga. (A patriot was conversing with Maharaj.) Maharaj told him: “You have been angry because you were humiliated, and you have resorted to going on a hunger strike. Now you take a resolution: ‘I will go on a hunger strike against my own nature. I will mercilessly stamp out every bit of temptation arising out of lust, anger, or greed.’” Swami Vivekananda cried himself hoarse about the need of applying the heart in all dealings. He travelled throughout India but couldn’t find a feeling heart anywhere. When the heart is present, head and hand will come by themselves. Of course, we sometimes come across a kind of heart that flares up all of a sudden, like when love overflows towards a particular person; this is dangerous, instinctive love. Perhaps at the very next moment it may become violent and tear the throat of the beloved. A true follower of Sri Ramakrishna is bound to be a patriot. Once, Swami Abhedanandaji was very ill. But even in that condition, he sent for Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose; and when he came, Abhedanandaji got up to embrace him. If a follower of Sri Ramakrishna or Swami Vivekananda is not a patriot, then know for certain that he is not their follower.

6.2.61

Question: Is there any danger if I give up the process of discrimination and follow just the path of devotion?

Maharaj: Just as chanting the name of Hari is compulsory for the Vaishnava mendicants, you cannot become a sannyasi without constantly discriminating about the five sheaths. How is it possible? I am such-andsuch, I am the son of so-and-so, I am this or that of the university — how will you forget all these without discrimination? Those who are brought up with dignity and luxury at home cannot give up that identification; they somehow bring up their pre-monastic identity and revel in their own superiority. You can succeed by following the path of devotion; but it takes a long time, and there is a risk of falling prey to various dangers on the way. Our monastic life seems to be like swagriha sannyasa, i.e., rooted in familial background, unable to overcome its identity. A Bengali has become a sannyasi and he will mix only with Bengalis; also he will not learn any other language. In a speech at Madras, someone referred to Sri Ramakrishna as a Bengali saint!! (To be continued. . .)

International Peace in the Light of Indian Philosophy

SWAMI DURGANANDA

(continued from the previous issue. . .)

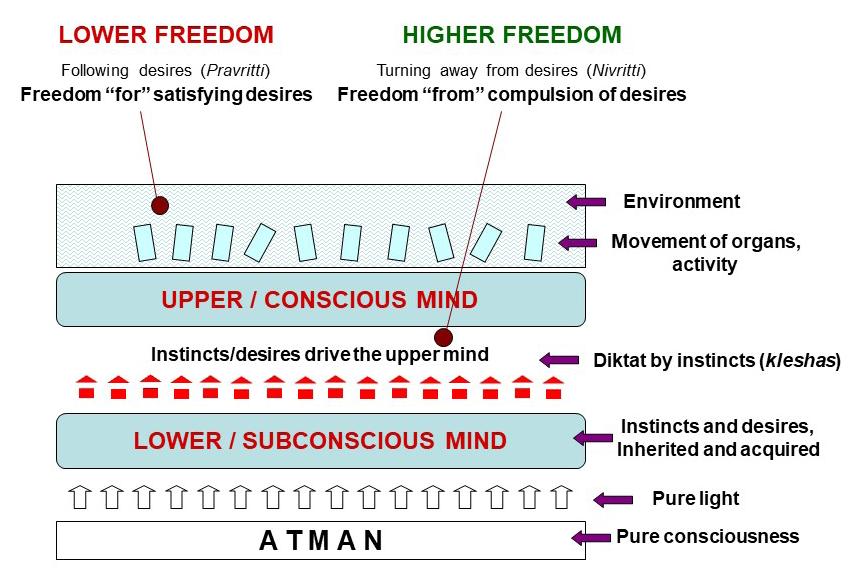

Two types of freedom

According to Indian philosophy, every experience leaves a mark in the mind. This ‘mark’, called the samskara (which is like a memory), is in two parts: 1) names and forms (nama-rupa) located in upper mind, 2) desires in subtle form, called vasanas, corresponding to the names and forms, located in lower mind. Vasanas are connected with names and forms and it is this connection that is troublesome. For instance, eating a cake or even seeing it will leave in the mind a ‘mark’ of 1) name and form of the cake, and, 2) the vasana (desire) to eat again. When one sees cake again or even hears the word ‘cake’, formerly deposited name and form activates the corresponding vasana. The vasana, which is like a seed, sprouts into the desire or impulse to eat the cake again. Eating the cake based on this desire completes the vicious circle. This cycle keeps life moving. Operational energy to the sprouting of the impulse of the vasana is provided by the individual’s life force (which is a part of the universal life force) and is delivered to the vital andthe mental levels of the individual by metabolism—this is the reason why a person’s desires and impulses increase when he is healthy and diminish when he is sick or lacking in vital energy.

Pravritti and Nivritti

The sum total of individual samskaras deposited in this life together with those that are inherited from parents is called the karmashaya, which may be translated as ‘instincts’. The instincts, roughly the same as the ego, include good and bad tendencies such as altruism, love, greed, desire, caprice, jealousy etc. They constantly drive the mind according to their own character. Man has very little control over this mechanism. He then seeks external freedom to vent out these promptings and drives—the action that may be described as dancing to their tune (Fig. 4). This external freedom to act in compulsion to the force of the impulses is called the lower freedom in Indian philosophy. It is like the freedom given to a drunkard (by the society) allowing him to drink. It allows you to do what you like or want. A person then acts to relieve the stress built from desires and impulses. This gives the pleasure of gratification which is sometimes likened to the satisfaction coming from scratching an itching skin.11 It is this freedom that almost the entire West has been preoccupied with and has been their highest achievement. Such an action is called pravritti (indulgence, lit., going in the direction of desires) in the Indian tradition. It must be noted, however, that in Indian classical literature, pravritti includes only ‘righteous behaviour, practice of truth, with cleanliness of body and mind. Enjoyment with fraud and deceit or injury or wanton behaviour is not pravritti, whatever else it may be.’12

Thus, pravritti is the freedom ‘for’ the satisfaction of desires. This is the freedom most people are obsessed with almost all of their time. The higher freedom, in contrast, is nivritti (lit., turning away from desires, or the freedom from the compulsion of desires). It is the freedom ‘from’ impulses themselves. It is like the freedom from addiction. It Fig. 4 Two types of freedom for individual or society (third thesis) is the freedom from the prison walls and the tyranny of body and mind the other hand, though better, is very difficult to itself. It detaches you from your deeply achieve because one cannot just ‘wish away’ ingrained likes and dislikes and frees you to do desires and instincts. What then is the way out? what is beneficial (called shreyas) as opposed The solution is to purify the karmashaya itself to what gives satisfaction or pleasure (called (the content of which, as mentioned before, preyas). This freedom allows man to be truly consists of the good and the bad instincts). free, releasing him from the grip of instincts Then pravritti(indulgence) will not be harmful. and freeing him to do good to himself and to This purification can be done by any one of the society.13 Without this inner freedom too these two ways: 1) removing the bad instincts much external freedom can even be harmful. An or at least keeping their impulse under control unencumbered mind, free of impulses, by training and effort, 2) sublimating the bad misconceptions, perversities, and fears is a instincts. In the first method one acts on the factory of peace and progress. Control of impulse of the bad samskaras and controls instincts is thus the answer to the question how them. In the second method, their impulse is justice, liberty etc., can live together and not kept intact, but this impulse is turned from bad encroach on each other. to good rather than striving to tame it.

Fig. 4 depicts pictorially the two types of It must be noted that in the other, the freedom and how the subconscious mind Nivritti method, one does not so much toil over dictates the conscious mind. The conscious removing or sublimating the bad instincts, mind, in its turn, operates the organs. Atman is rather, he strives to attain freedom from them the ultimate source of energy and light for mind by sheer will. It is for this that detachment as well as for the vital and physical functions. (vairagya), and dispassion are practised.

The purification Society has a Karmashaya

Pravritti (acceding to desires or This article offers the view that exactly as karmashaya), which is the same as craving, individuals, societies (or nations) too are usually degenerates into uncontrolled and instinctive behaviour. Nivritti (withdrawal), on (continued on page 40...)

A Problem in Geography

GITANJALI MURARI A fictional narrative based on incidents from the childhood of Swami Vivekananda. “An estuary is formed by a river or a freshwater body joining the sea or ocean,” the teacher turned from the blackboard, “can anyone give me an example of an estuary?”

Hari raised his hand, “Chilika lake, sir.”

“I’m quite certain that Chilika lake is an estuary,” the teacher said coldly.

But Naren wouldn’t give up. “Sir,” he said, holding up a book, “it says so here…should I read it out?” The teacher snatched the book from Naren and glanced at the cover.

“This is not a textbook from the syllabus,” he said angrily, “how dare you bring it to class? Hold out your hand, you little show-off,” and he hit Naren’s open palm with a stick several times. Naren didn’t flinch. He clenched his jaw to stop himself from crying out.

Pranab Sen glared at him, “Admit you’ve made a mistake.” Gritting his teeth, Naren shook his head, “Please read the book, sir and then tell me if I’m right or wrong.”

In the pin-drop silence of the classroom, Naren picked up his bag and left. As soon as he was out of the school, he began to run, tears trickling down his cheeks. Bursting through the front door of his house, he called out, “Ma, where are you?” Surprised to hear her son’s voice, Bhuvaneshwari Devi came out of the kitchen. “You’re home early,” she exclaimed but noticing his distress, became concerned, “What’s the matter Naren?”

A flood of words poured out of him. While his mother applied ghee on his injured hand, Naren narrated the entire story. When he finished, she asked, “Naren, are you absolutely certain you haven’t made a mistake?” “Ma, that’s what it says in the book baba got for me.”

That evening, just as the family gathered for prayers, a servant hurried up to Bhuvaneshwari Devi and whispered in her ear. She came out into the courtyard. Pranab Sen rushed up to her and with hands folded said in a low voice, “I’m sorry to disturb you at this hour but I couldn’t keep away.” Bhuvaneshwari Devi smiled graciously, “How may I help you?”

“I’ve come to apologize...you see, I’ve been quite unfair to Naren…today, in class…” Pranab Sen hesitated. “Naren told me everything,” Bhuvaneshwari Devi said gently, “would you like to meet him?” The teacher nodded. Naren was sent for and at the sight of Pranab Sen, he became worried. “Naren,” the teacher began, “you are right about estuaries and lagoons…I read your book and looked it up elsewhere too…instead of encouraging your spirit of curiosity, I raised my hand on you...please forgive me.” Without a moment’s hesitation, Naren ran up to Pranab Sen and hugged him.

Bhuvaneshwari Devi smiled. Leaving the two to chat, she went inside the worship hall.

Have faith in yourselves, and stand up on that faith and be strong. — Swami Vivekananda

ISSUE 10 ISSUE 36

Series 5: Understanding India - through Swami Vivekananda's eyes

This series is a presentation of a set of lectures that Swami Vivekananda gave over three years, as he travelled from Colombo to Almora (January 1897- March 1901). In Issues 22-27 & 29-35, we have covered his lectures at Colombo, Jaffna, Pamban, Rameshwaram, Ramnad, Paramakudi, Shivaganga & Manamadura, Madura and Kumbakonam.

focus in this issue: My Plan of Campaign - 1

From Kumbakonam, Swami Vivekananda went on to Madras, where he addressed a packed audience at Victoria Hall. His speech here is a long one, and we will be presenting it in four parts − Part 1: Setting the Record Straight, Part 2: Some principles of reform, Part 3: A survey of reform in India, and Part 4: Swami Vivekananda's plan of action. In this issue we will cover Part 1 and Part 2.

Part 1: Setting the Record Straight

1.1

SWAMI VIVEKANANDA ON THE EFFORTS OF THE REFORM GROUPS OF INDIA TO HINDER HIS PROGRESS

– Swami Vivekananda faced tremendous difficulties, before, during, and after his speech at Chicago in the Parliament of

Religions. – While some of the difficulties were due to the fact that he was an unknown Indian presenting a radically new vision of life to the Western world at the height of its power, many of the difficulties were caused by so called reformers. – In this talk Swami Vivekananda discusses three groups of reformers – (i) The Theosophists, (ii) The Christian

Missionaries and (iii) The Reform Societies and sets the record straight on the role of these reformer groups in hindering his progress. – In all these cases, he demonstrates how these reformers help only when it serves their own interests, and not when it is actually needed or goes somewhat contrary to their ideas or agenda.

>Continue overleaf

“We hear so much tall talk in this world, of liberal ideas and sympathy with differences of opinion. That is very good, but as a fact, we find that one sympathises with another only so long as the other believes in everything he has to say, but as soon as he dares to differ, that sympathy is gone, that love vanishes.”

Designed & developed by

ILLUMINE

Knowledge Catalysts