20 minute read

Vivekananda Way

SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND THE CHRISTIAN MISSIONARIES; THE BRAHMO SAMAJ

SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND THE REFORM SOCIETIES OF MADRAS

Advertisement

– Before going to America, Swami Vivekananda approached Theosophists for help.

However, they were willing to help if and only if Swami Vivekananda was willing to subscribe to their views and join their society.

– When Swami Vivekananda was suffering in America due to want of money and help, the Theosophists wrote: "Now the There is a report going round that the

devil is going to die; God bless us all." Theosophists helped the

– At the beginning of the Parliament of Religions, they dealt little achievements of mine

with Swami Vivekananda with looks of scorn on their faces, in America and England. I as if to say: "What business has the worm to be here in the have to tell you plainly that midst of the gods?" Even after Swami Vivekananda became every word of it is wrong, popular at the Parliament, the Theosophists prevented their every word of it is untrue. supporters from attending his lectures.

– The Christian missionaries in America blackened Swami

Vivekananda's character from city to city, even though he was poor and friendless in a foreign country. They even tried to starve him out.

– One of his own fellow countrymen, who was in the Parliament

of Religions representing the Brahmo Samaj, and whom the Swami knew since his childhood, became jealous of him after Swami Vivekananda became popular in Chicago, and in an underhand way, tried to do everything he could to injure the Swami's interests.

– One magazine of such social reform groups tried to question

Swami Vivekananda's right to become a sannyasin, on the grounds that he was from the Shudra caste. To this Swami Vivekananda points out that they had got the caste wrong - he was a kshatriya, and moreover, he was not affected in the least by being called a shudra since all people have got equal rights to become a sannyasin.

– Even some of the reform societies of Madras, who were I have a little

otherwise well-wishers, tried to intimidate Swami Vivekananda will of my own. to join them. I have my little

– To this the Swami points out that, he was a man who had experience too; and I have a message for the

met starvation face to face for 14 years of his life, had lived world which I will deliver with almost no clothes in temperatures of 30 degrees below without fear and without zero, and had not known where he will get his next meal from care for the future. or where he would sleep. And so such a man was not to be intimated easily in India.

1.3

What harm does it do to the Christian missionary that the Hindus are trying to cleanse their own houses? What injury will it do to the Brahmo Samaj and other reform bodies that the Hindus are trying their best to reform themselves? Why should they stand in opposition? Why should they be the greatest enemies of these movements? Why? — I ask. It seems to me that their hatred and jealousy are so bitter that no why or how can be asked there.

1.4

1.4 THE IDEAL REFORMER ACCORDING TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA – Swami Vivekananda brings out the case of his own Guru − Sri

Ramakrishna, who, in order to destroy caste-division in his mind, chose to clean the toilet of a Pariah's house with his own hair, and eradicate thereby the ego of brahminhood. – This, Swami Vivekananda says, demonstrates what reform within really means - translating noble thoughts into practice and thereby bringing about a change in society. – Swami Vivekananda concludes that Hindu's should uplift themselves rather than look for any foreign influence.

By being the servant of all, a Hindu seeks to uplift himself. That is how the Hindus should uplift the masses, and not by looking for any foreign influence.

Part 2: Some principles of reform

3.1

Reform as growth, not negation

– Swami Vivekananda points out that while he too seeks reform, reform for him is not a process of destruction or negation of all that is from the past. Rather he sees reform as a process of growth from where individuals or society have reached this far. – He is clear that his goal is not to dictate or advise society to go one way or other; rather his goal is to contribute to the development of society.

I do not dare to put myself in the position of God and dictate to our society, "This way thou shouldst move and not that." I simply want to be like the squirrel in the building of Râma's bridge, who was quite content to put on the bridge his little quota of sand-dust.

3.2

Reform as enablement of the "National Machine"

Ours is only to work, as the Gita says, without looking for results. Feed the national life with the fuel it wants, but the growth is its own; none can dictate its growth to it.

– Swami Vivekananda recognizes that Indian national life is like a wonderful & complex machine or a mighty river that is flowing in front of us. – There are several factors and influencing forces which impact it making it “dull” at one place/time and “quicker” at another, giving it a life of its own. It is futile to command and control such a machine. – As reformers, we can only work without seeking results, i.e. feed the national life with fuel it wants and let it find its own way rather than dictate its growth to it.

3.3

The work against evils in society is primarily educational in nature

– Every society has several evils. In fact, evil and good are two sides of the same coin. If society makes progress on some counts, then new evils are also created by that same progress. – Therefore, the only thing we can do is understand that evil cannot be eradicated, rather the work against evil is more subjective than objective – more educational that actual, i.e. rather than hope to destroy evil we can seek to help people grow and evolve, thereby making them more able to deal with the evil.

...the only thing we can do is to understand that all this work against evil is more subjective than objective. The work against evil is more educational than actual, however big we may talk.

The challenge of reform is also the challenge of creating the “sanction” or the power of the people to reform themselves

– Swami Vivekananda firstly warns against all fanatical reform movements. Such movements, even if well intentioned, end up defeating their own ends or lead to unforeseen consequences. Therefore, he is against all “condemning societies” who are continuously haranguing everyone on the evils of society. Instead, he says, what is needed are people who will help in concrete ways. – We need a reformer who does not condemn, but instead loves and has genuine sympathy for those who he/she seeks to reform. – In the absence of such help, love and sympathy attempts at reforming others leads to a cycle of condemnation and counter condemnation by those accused, all of which can be most unpleasant and shameful. It will not lead to genuine reform.

– For ages, India has been ruled by kings. They are gone.

Governments do not have the power to go against public opinion. But developing a healthy and strong public opinion (which solves its own problems) takes a long time to develop. – At the same time, a small number of people, who think that certain things are evil or need to be changed, cannot make a nation move. – The solution is to educate the people, create a legislative body that has the social sanction of people, and then whatever laws are needed for social reform will be forthcoming. – Most reforms that have taken place in the 19th century have been ornamental or superficial impacting a small proportion of the population. – But deep or radical reform requires us to go down to the fundamentals or roots of the whole problem. – This means creating a strong sense of citizenship or nationhood – i.e. creating an Indian Nation. – This is what Swami Vivekananda called radical reform – create an Indian nation that can take responsibility, has the maturity and the legislative mechanisms to address its own problems.

Everybody can show what evil is, but he is the friend of mankind who finds a way out of the difficulty. Like the drowning boy and the philosopher — when the philosopher was lecturing him, the boy cried, "Take me out of the water first" — so our people cry: "We have had lectures enough, societies enough, papers enough; where is the man who will lend us a hand to drag us out? Where is the man who really loves us? Where is the man who has sympathy for us?" Ay, that man is wanted.

3.5

The whole problem of social reform, therefore, resolves itself into this: where are those who want reform? Make them first. Where are the people? ... Why does not the nation move? First educate the nation, create your legislative body, and then the law will be forthcoming. First create the power, the sanction from which the law will spring. The kings are gone; where is the new sanction, the new power of the people? Bring it up. Therefore, even for social reform, the first duty is to educate the people, and you will have to wait till that time comes.

TO BE CONTINUED...

Magic , Miracles and the Mystical Twelve

LAKSHMI DEVNATH

The Royal Devotee

The Story of Kulashekhara Aazhvaar

(Continued from the previous issue. . .)

Poorva admired the king’s kindness and thought that the ministers had undoubtedly got off very easily. She also wondered what the king had meant by saying that one should distinguish between ‘truth and falsehood’.

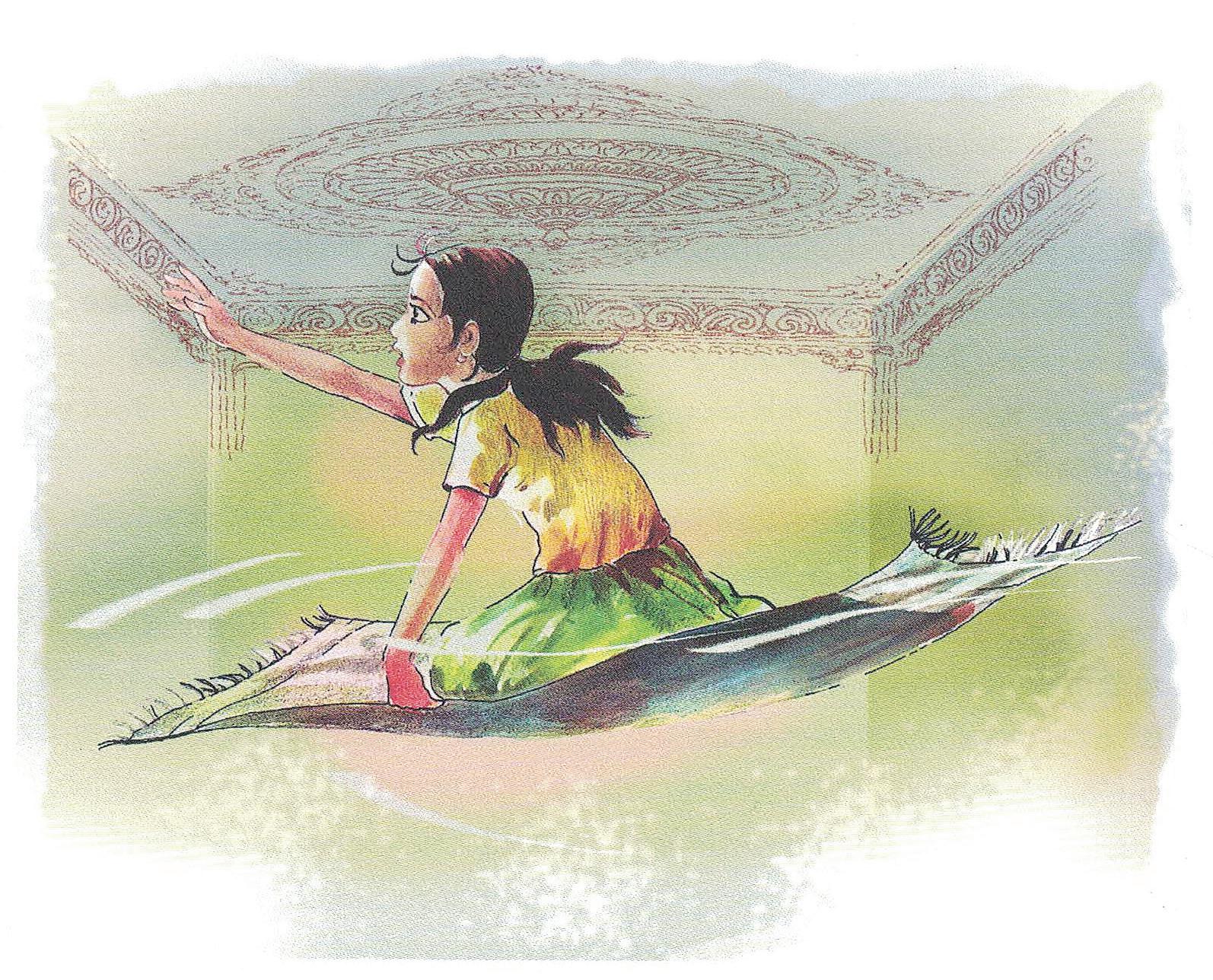

Since the Swami was not around to help her out on this, she decided to find out for herself by meditating on Lord Vishnu, as the king had suggested. She folded her legs and sat down on an exquisitely woven carpet.

Closing her eyes, she wondered what the next step in meditation was, when she experienced a funny feeling. “Do people levitate when they meditate?” Poorva chuckled when she found that the words rhymed. Ten seconds later, she told herself, “It’s ages since I shut my eyes. I wonder what’s happening around me.”

When she opened her eyes, she was horrified to see that she was up in the air, a good seven feet above the ground! The carpet on which she was sitting was slowly rising. She looked at the ceiling barely a few feet above and screamed, “Aaaaah! Vishnu, please come to my rescue.”

The carpet picked up momentum. Poorva buried her face in her hands, sure that her head would be smashed to smithereens.

Seconds later, a draught of cool air caressed her eyelids. She gingerly opened her eyes and found herself high up in the skies. Giggling nervously, she remarked, “Thank God, I’m still alive.”

The author is a researcher and writer with various books and articles on Indian music and culture to her credit. lakshmidevnath@gmail.com Illustrator: Smt. Lalithaa Thyagarajan. lalithyagu@gmail.com

Gradually, Poorva regained her composure and, when she turned around, saw the Swami seated behind her on the carpet. He greeted her in his usual jaunty way, “Hello, Poorva, nice ride, isn’t it?”

The Swami lightly brushed aside her compliment: “Well, you can expect the unexpected on this trip.”

“And if you look down, you’ll see that Kulashekhara Aazhvaar is now at the famous Thirupathi temple, on a pilgrimage,” replied the Swami.

Poorva looked down. The temple was different from the way she remembered it. That’s because right now we’re in olden times, she reasoned to herself. The flying carpet dropped height and she heard the Aazhvaar singing. His voice faded into the background as the Swami took over with the translation: “‘I would rather be a little bird or an insect or a stream, or even a stone in the abode of the Lord, if it would ensure my being close to Him.’”

The Swami added, “In appreciation of his wish, the step at the entrance of the sanctum sanctorum in all Vishnu temples will, in the days to come, be called Kulashekharan padi.”

“Padi means ‘step’, so that means the ‘Kulashekharan step’,” Poorva mumbled to herself.

She heard the Aazhvaar sing a few more songs and then saw him come out of the temple. He was proceeding elsewhere. “I think it’s time we bid goodbye to Kulashekhara Aazhvaar, Poorva. From now on, his life will be spent in pilgrimages to various temples. His songs – 105 in all – will be collected and compiled as the Perumaal Thirumozhi – auspicious words of Perumaal. Through his songs, he conveys the message that one should serve both God and His devotees. When he turns sixty-seven, he’ll breathe his last at a place called Brahmadhesam near Aazhvaar Thirunagari.”

“Swami Thaatha, you mentioned Perumaal Thirumozhi. Did you mean Kulashekhara Thirumozhi?” asked Poorva.

The Swami replied, “No, no. There are different opinions on why his songs are called Perumaal Thirumozhi. Tradition has it that he has been honoured with the title of Perumaal, meaning ‘God’, because of his intense devotion to Lord Rama. There are others who say that ‘Perumaal’ is the king’s family name. People are also not sure whether it is this Kulashekhara who has authored the famous Sanskrit poem, Mukundhamaala.”

“It would,” agreed the Swami, “but think a little. Throughout this trip, you’ve been seeing people, but they can’t see you. You can hear them, but they can’t hear you. So what you see is what you get to know, in addition to what I tell you, of course,” said the Swami.

“And that in itself is quite a lot,” laughed Poorva, as the carpet gained momentum and raced past a flock of migrating birds. “Have a good time in Siberia, or wherever else you’re going …” Poorva waved to them.

A moment later, her face wore a puzzled look. I’m up in the sky, and so are these birds. Then how come they suddenly look like small specks? At what altitude are they flying? As she mused, something bit her leg and she winced in pain.

“I didn’t know mosquitoes could fly higher than eagles!” exclaimed Poorva as she tried to swat the irritating pest. The target escaped and Poorva’s palm landed firmly on soft grass.

Ramachandra Dutta

DR. RUCHIRA MITRA This is the eighth story in the series on devotees who had a role in the divine play of Sri Ramakrishna.

्यमे्वैष ्वृणुते तेन लभ्यरः

It is attained by him alone whom

It chooses (Kathopanishad. 1.2:23)

13 November 1879. Three affluent gentlemen of Kolkata were on their way to meet Sri Ramakrishna, about whose pure life they had heard from Keshav Chandra Sen. On reaching Dakshineswar, they found his room closed. But as soon as they reached the room, Sri Ramakrishna himself opened the door and came out to receive them, as if he was expecting their arrival. Sri Ramakrishna asked them to sit and looked smilingly at one of them and simply told him, “Hello, you are a doctor. Please check his [his nephew Hriday’s] pulse. He is suffering from fever.” The man did as he was bid, but was dumbfounded that Sri Ramakrishna knew he was a doctor!

Very soon this gentleman became one of the foremost householder disciples of Sri Ramakrishna. He was Ram Chandra Dutta, a doctor with many professional achievements. He invented an antidote for blood dysentery which got the approval from the British government. He became famous when leading doctors started prescribing it. Consequently, he was appointed a member of the Chemist Association of England. He was raised to the post of Government Chemical Examiner and was also appointed as a teacher at theCalcutta Medical College for the military medical students. This deep involvement with modern science had a flip side to it, in that it made him an atheist.1

When his little daughter died suddenly, Ram was plunged into immense grief. His attempts to find solace in the Brahmo ideas proved futile. His first visit to Sri Ramakrishna was the turning point in his life and he soon became a staunch devotee.

One night, Ram dreamed that he took bath in a pond and Sri Ramakrishna initiated him with a sacred mantra and asked him to repeat it one hundred times every day after his bath. When he woke up from the dream, he felt his body pulsating with bliss. The next morning, he rushed to Dakshineswar and related his dream to Sri Ramakrishna. At this Sri Ramakrishna joyfully said, “He who receives divine blessings in a dream is sure to attain liberation.”2

Ram used to carry out Sri Ramakrishna’s teachings to the letter. Sri Ramakrishna told him, “Whoever serves the devotees, serves me,” Ram used to say, “He who calls on Sri Ramakrishna is my nearest relative.” Sri Ramakrishna visited Ram’s house for the first time on Vaisakhi Purnima, and henceforth every year Ram celebrated this day as a festival. During Sri Ramakrishna’s lifetime, Ram organised festivals with Sri Ramakrishna and the devotees in his home; and later his home

became a shelter for the devotees practising austerities. It was Ram who took his cousin Naren (later Swami Vivekananda) to Sri Ramakrishna at Dakshineswar for the first time in his own carriage!

Ram had the firm conviction that Sri Ramakrishna was an incarnation of God. His dedication and love for his Guru was so profound that he passionately asserted that any place visited by Sri Ramakrishna was holy; and the coach and the coachman which carried him around were holy too! Once, someone sarcastically remarked, “If that is true, so many men have seen him, so many coachmen have driven him, will they get liberation?” Ram vehemently retorted: “Go and take the dust of the feet of the coachman who drove the Master. Go and take the dust of the feet of the sweeper of Dakshineswar who saw the Master! This will make your life pure and blessed.”3

On 1 January 1886, Sri Ramakrishna revealed his divinity to his householder devotees and bestowed the taste of divine joy on all. Ram explained that Ramakrishna had, in effect, become Kalpataru, the ‘wish-fulfilling tree’. Henceforth, every year Ram celebrated January 1 as Kalpataru Day at his Kankurgachi garden house, called ‘Yogodyan’.

Yogodyan was constructed as per Sri Ramakrishna’s advice to build a place for nirjan-vas and sadhana far away from the city. Therefore, Yogodyan holds a special position as the centre that was started at the bidding of Sri Ramakrishna, who visited this site and commented, ekhane besh dhyan hoy, “This place is suitable for meditation.”

After Sri Ramakrishna’s mahasamadhi on 16 August 1886, his ashes were collected in an urn. Ram wished to keep the urn of ashes in Yogodyan. But Sri Ramakrishna’s future monastic disciples too were eager to keep the ashes. So, they transferred a major portion of the ashes to another urn, and handed over the original urn to Ram. He, in good faith, then ceremoniously consecrated it in Yogodyan on Janmashtamiday, 23rd August. All the monastic and householder disciples of Sri Ramakrishna participated in the grand celebration. Ram soon established the first Ramakrishna Temple at Yogodyan, enshrining Sri Ramakrishna’s relics. He led a frugal life and made it a ritual to offer worship at Yogodyan every day, commuting from his residence 6 km away.

Ram became Sri Ramakrishna’s first evangelist and played a big role in spreading his message. He delivered 18 public lectures extolling Sri Ramakrishna’s life and teachings. His first lecture was titled “Is Ramakrishna Paramahamsa an Avatar?” Ram also wrote Sri Ramakrishna’s first biography, Sri Sri Ramakrishna Paramhansadever Jivanvrittanta, and subsequently expanded it by including his teachings and named it Tattva-Prakashika. Moreover, at Yogodyan, Ram groomed many youngsters who later became the second generation sannyasis of the Ramakrishna Order.

Five days before his passing away, Ram shifted to Yogodyan, as he had a premonition that he would die soon. He was just 47. On arriving there, Ram said, “I have come here to have my final rest near my Guru Sri Ramakrishna.” Ram’s relics are kept near the gate of Yogodyan adjoining Sri Ramakrishna’s temple, as his last wish was “When I die please bury a little of the ashes of my body at the entrance to Yogodyan. Whoever enters this place will walk over my head, and thus I shall get the touch of the Master’s devotees’ feet forever.”4

References: 1) They Lived with God, 96-97 2) Ibid. 99 3) Ibid. 95 4) Ibid. 109

Pariprasna

Srimat Swami Tapasyananda Ji (1904 – 1991) was one of the Vice-Presidents of the Ramakrishna Order. His deeply convincing answers to devotees’ questions raised in spiritual retreats and in personal letters have been published in book form as Spiritual Quest: Questions & Answers. Pariprasna is a selection from this book.

QUESTION: Finite man’s knowledge is necessarily finite. So what is meant by the term ‘omniscience’ in such Sruti statements as ‘The knower of the Self knows everything’?

MAHARAJ: The above statement in the Upanishads does not mean that an illumined sage knows every one of the subjects in world like algebra, geometry, anthropology, history etc. It means only that when the ultimate essence of all is understood, one has a basic knowledge of all the diversities springing from it. Thus if the nature of gold is understood, one has the knowledge of the basic stuff of all things made of gold. When one has a knowledge of the basic stuff, gold, one will be evaluating gold, ornaments etc., from the point of view of gold and not from the point of view of the changing modes into which gold can be shaped. Another example often given is that of a grain of rice from a cauldron of boiling rice being taken and squeezed between the fingers. One can thereby know whether all the rice in the pot is well boiled or not. The Vedanta holds that Brahman is the one Substance and all the multiplicity experienced is either an apparent expression of it, or an evolution of Its inherent powers, or of the attributes organically related to It. This basic nature of everything is outside the understanding of men in ignorance. Englightenment enables men to understand that Brahman is the basis of everything. This is the omniscience spoken of in the Upanishads.

It is also true that a person whose mind has gained the subtlety and concentration required for attaining this enlightened understanding, can very easily gather any particularized knowledge, if he but applies his mind to it. A controlled and concentrated mind, the key to all knowledge, is in his possession, and with it he can open any mansion of knowledge, if he cares to do so. Probably some of the Rishis were persons of this type, who had the spiritual awakening and at the same time the mastery of much of the then known arts and science by the application of their concentrated minds on them. Traditions coming from such personages must have given rise to the current notion of omniscience held by some persons interested in occult lore.