fall/winter

Leaning Into Complexity + Schechter Stands with Israel

The Schechter Song

וימורמב םולש השוע , ונילע םולש השעי אוה

לארשי- לכ לעו

May the One who makes peace in the heavens, make peace for us and all of Israel.

fall/winter

Leaning Into Complexity + Schechter Stands with Israel

The Schechter Song

וימורמב םולש השוע , ונילע םולש השעי אוה

לארשי- לכ לעו

May the One who makes peace in the heavens, make peace for us and all of Israel.

As I write to you now, we are midway through a school year like no other.

We returned to school in September with the exuberance and promise we always feel when we see the planning and preparation of the summer go into action. We welcomed new students, families, faculty and staff as we looked forward to settling into the rhythms of fall.

As with every day of every year, we show up to school ready to teach, learn and change. We show up to pray, celebrate chagim, to speak Hebrew and live and explore our Jewish identities. We show up to listen and share, to be there for each other and be part of klal yisrael. We also show up by being present, engaged and passionate.

On October 7, our world was turned upside down. The attack on Israel shattered our innocence and anything we could have expected for the year ahead, but we are a strong community and we stand tall. In the wake of the war,

we showed up to support each other, to mourn, to volunteer and to come together to find our way in and through this moment.

I am in awe of our community. I could never possibly acknowledge every joy or triumph, every act of kindness or devotion because there is simply so much effort and goodness all the time from every person, youngest to oldest. My gratitude is limitless at the extraordinary faith we have in each other, and what we achieve as a community.

Schechter Stories is a window into the masterful work by our faculty and staff, the eagerness of our students, the diligence of our parent volunteers and the exceptional accomplishments of our alumni. When you read the pages ahead, I trust you will swell with the same pride and appreciation for Schechter that I do when I show up to school every morning.

Rebecca Lurie, Head of School

Rebecca Lurie, Head of School

fall

Leaning

Writing

Stephanie

Contributing

Heidi Aaronson ’96, P’24, P’27

Diana Levine P’27, P’30

Ken Marcou Image & Media

Stephanie Fine Maroun

Design

Joel Sadagursky

Printing Puritan

We

schechter stands with israel hachnasat orchim: schechter parent association

looking back, looking forward annual campaign meet jeremy kadden, senior development officer

In the calm of an early morning this past October, before the first class of the day and before the bustle of students moving through the hallways, 13 faculty members met in the Wells Avenue Campus teachers’ lounge to make challah. The precise step-by-step technique of measuring and mixing flour, yeast and water, then returning hours later to knead the dough, was a familiar process for some, and a first for others.

The inspiration for the gathering came from Rabba Amy Newman, Grade 6 Jewish Studies Teacher. “I started thinking about this idea after October 7, when the war started in Israel. Making challah is a mitzvah, and there is this concept of bringing more mitzvot to the world. I wanted to dedicate this activity to the safe release of the hostages, for the safety of the Israeli soldiers, to people in danger in Israel.”

Despite the jam-packed schedule at school, Rabba Newman plotted out each stage of the challah baking so that it fit into natural breaks during the day: assembling the dough before morning drop-off, kneading it for seven minutes according to the recipe, then stowing it in the refrigerator to rise; teaching classes; returning at lunchtime to braid the dough; leaving after school with the chilled dough to bake at home. During the day, the comforting smell of the rising dough floated from the teachers’ lounge out into the hallway where it mingled wonderfully with the foot traffic.

In the weeks following the attack on Israel, students settled into an implicit, almost organic agreement not to talk about the war every day, yet there are faculty members who have children or relatives serving in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

“It is quite complex for teachers to keep life as normal as possible at school right now,” Rabba Newman says. “The act of getting your hands into dough, especially among company, is therapeutic, and when your hands are busy you can talk more freely. There is so much beauty and value in a community of professionals connecting this way. One teacher’s phone rang while we were kneading the dough and it was her son, who is a soldier, calling from Israel to say he is all right. We teach best when our whole selves are cared for and connected.” Setting up the ingredients is fast, and the first test run dovetailed neatly with the school day, so the group plans to continue, perhaps bringing the activity to students at one point.

“Everything has changed,” says Rabba Newman. “Our Jewish lives are now divided

into before and after October 7. We are the adults who have to help kids process and understand this new reality. We have to be honest about what is happening, and protect them from things they shouldn't see. We also have to allow them to be sad, and to take care of them and their sadness. The kids embraced the new Israeli students who arrived almost every day as if it were normal. Our students do understand, though, that this is not normal and that their new Israeli classmates are here because they were not safe at home. Our students are responding in the best possible way.”

From the baking of challah to a school day’s routines, the community will continue to draw sustenance from conversation and camaraderie, and being together.

One teacher’s phone rang while we were kneading the dough and it was her son, who is a soldier, calling from Israel to say he is all right.

What if we wrote a song that is always in the process of being written?

dR . JoNah hasseNFeldAs members of Schechter’s educational leadership team, Dr. Jonah Hassenfeld, Director of Learning and Teaching, and Rabbi Ravid Tilles, Director of Jewish Life and Learning, are daily collaborators and thought partners, helping to execute the school’s vision for stellar teaching and meaningful Jewish practice. Unbeknownst to some, they are also the synergistic duo behind a number of homegrown hit songs at Schechter.

For instance, Rabbi Tilles’ dramatic weekly podcast, Parsha Stories, opens to a different theme song for each book of the Torah, written and performed by Jonah, right down to catchy rhymes about the Parashat Hashavua itself. To explain Schechter’s stance on kippot, they penned a song, “Keep on Keeping It On.”

This past summer, the concept of a school song surfaced. The writing of the song

ultimately yielded a parallel experience, namely the intellectual self-examination of what it means to create a school tradition. Traditions usually develop organically and may not be recognized as such in their nascency. The goal here, however, was to launch a ritual from scratch that would connect one Schechter student or community member to another in spite of the passage of time or each individual’s unique Schechter experience.

Rabbi Tilles and Jonah describe their artistic rapport. “I usually present Jonah with a Jewish theme or moment at school for which I need him to compose original music on his guitar. I’ll tell him the tone I’m going for, and he is such a talented musician that he can compose music that is completely original. We do a lot of vibing back and forth until we’ve got the right spirit for the song.” The lyrics are always memorable and 100

percent Schechter, customized to express or introduce exactly what the occasion needs.

“Music is a mechanism that binds,” explains Rabbi Tilles. “We spend a lot of time thinking about things, in general, so we had to consider what a Schechter nigun, or tune, should sound like. What’s the difference between an anthem or a college fight song?”

Jonah recalls, “We wrote a lot of lyrics and just were not satisfied with them. There were lyrics about Jewish learning and values, but it was impossible to know where to stop or what not to include because everyone takes away something different from their Schechter experience. Then we had this interesting idea. What if we wrote a song that is always in the process of being written? Once we landed on that concept, it took no time at all. We had gotten to the heart of what we wanted. We had a beat, a background, but it was otherwise flexible,

freestyle, and modeled on this concept of a living song.”

The song is composed of one stanza—At Schechter Boston, we’re indivisible—and always begins with the same second line as an introduction:

At Schechter Boston, our hearts are full. At Schechter Boston, we’re indivisible.

Then, the song departs from the expected, almost functioning like a call and response as each participant, singer or audience member pipes in with a unique, personal line that rhymes loosely with “indivisible.” The song is designed to be an evergreen, oral tradition because the opening single stanza will always be true, but each person who contributes a refrain draws from personal associations with Schechter as a student, teacher, community member, alumnus or alumna.

Part of the song’s inherent enjoyment is the iterative, group dynamic. Quite quickly, participants seize on a line that feels right for

them, sometimes instantly constructing a new word in order to make their contribution rhyme with “indivisible.” There is laughter and nostalgia, many moments of awwww and mutual understanding, and plenty of anticipation for the next creative verse:

Making sure our numbers are factorable, At Schechter Boston, we’re indivisible. We want our tefillot to feel spiritual, At Schechter Boston, we’re indivisible.

We’re excited to learn about the 8th-grade musical,

At Schechter Boston, we’re indivisible.

In seventh grade, we fly to D.C., the capitol, At Schechter Boston, we’re indivisible.

“Ritual is important,” notes Rabbi Tilles. While it may seem a bit time-bending to engineer a ritual, Jonah and Rabbi Tilles used the summer, along with faculty and staff meetings before the start of school, to test drive The Schechter Song as they pondered the right way to roll it out to the larger community and especially students.

“We actually acted it out during Hanhallah (school leadership) meetings with the Board of Trustees, with faculty and staff so that we really knew the steps of having people catch on. We prepped and planted a few people each time to help get it started, but everyone else caught on and chimed in enthusiastically with fantastic results.”

Friday morning on the Wells Avenue Campus, Grades 4-8 come together for Ruach Minyan which Rabbi Tillles describes as somewhere between tefillot and a rock concert, but precisely the sort of bongo-infused, highly spirited community davening experience that has students jumping up to lead and swaying arm in arm. The Schechter Song made its debut with the students at Ruach Minyan, the perfect marriage between a weekly tradition and a new tradition.

“We knew from the beginning that the song could feel corny, but it had to be the right amount of self-aware corny. It had to be serious, funny, sincere, but not overly sincere. We were worried about hearing crickets with

the older kids.” Just the opposite happened. “Two students got up first and belted out a line together in front of 300 of their peers. The kids have really leaned into it which is so exciting. We now use it as warm-up music on Fridays,” Jonah says.

As it becomes an established part of school culture, The Schechter Song will be heard more and more frequently. The intentionality behind its fluidity and personalization remains core to the song’s transcendence and ability to stand the test of time. Perhaps there will one day be a fixed rendition of the nigun that exists alongside the improvisational versions and which can be sung in unison. Perhaps there will be an opportunity to record verses at home or from overseas to be spliced together in a delightful mash-up. Each person brings a unique stamp to the song, as unique and special as Schechter itself.

In the Wells Avenue Art Studio, Grades 6-8 Art Teacher Shoshana Rosen hooked sixth-graders early in the year with a unit she describes as “incredibly active, challenging

and kinetic.” The multi-week undertaking was based on a real New York City project called Tantamount that was started by a group of artists in 2005.

“Tantamount refers to creating a duplicate of something and stretching common materials to redesign an object. The original artists would go out and choose something like a water bottle, then make a copy of it out of recyclables,” Shoshana explains. She showed students several examples of artists such as Lucy Sparrow who constructed a bagel shop out of felt, ceramicist Katharine Morling who creates porcelain models, and the art collective Dosshaus that renders their work out of cardboard.

Shoshana employs an approach called Teaching Artistic Behavior in which the room is set up in studio centers. “We do

traditional lessons and techniques, but rather than having everyone painting at the same time, for instance, it's more about having kids see the room as their own art studio and navigating the space on their own, understanding where sculpture materials are, where hot glue is, where tools for carving the cardboard are or where to find the sewing machines.” Students learn how to fashion the armature or skeleton for their piece or how to use engineering to make a functional sculpture.

Stepping into the art room means taking on studio habits which begin with observing deeply and include engaging and persisting especially when a project is taking a long time to complete. Students learn to stretch and manipulate textiles, cardboard and other objects, and quickly realize they can create anything.

Jewish day school is more vital, more life-sustaining,

leaning into complexity The sacrosanct mission before us at Schechter is to embody and deliver the education that young Jewish people need in order to go forth every day with pride and wisdom, resilience and inquisitiveness. It is a formidable task to imbue students with the habits of mind that will guide them throughout their lives, and to infuse in them a personal Jewish identity so consequential and unshakable that they stay Jewish even when life experiences might tarnish their sense of security.

By its very nature, Jewish education requires active dialogue, dynamic partnership and respectful dissent. The Jewish value of asking questions is liberally fed by the enormous diversity in Jewish beliefs and practices among our community members. We lean into the complexities of teaching our students to consider multiple perspectives and extrapolate nuanced information whether they are in social studies or Jewish Studies, circle time or science.

We lean into the Schechter Be’s, ensuring that our students will be known, belong, be engaged, be inspired and be prepared. The last “be,” is arguably the most complicated for while it certainly means remembering to bring your

homework to class, “being prepared” also refers to developing the emotional and intellectual skills to respond to the unpredictable, to sit with uncertainty or to be suddenly asked to help. The concept of being prepared is inherently open-ended, perhaps even unsettling in its non-specificity.

In a matter of hours, the abstract of “being prepared” became a reality beyond the scope of anything we could have imagined. We exist within two realms now as Jews: before October 7, and after October 7.

Our community wore black and white to school on Tuesday, October 10. We had not expected to dress this way that day. We had not expected to gather on each campus in a state of anguish, disbelief and fury. We had not expected to lower the Israeli flag in front of each campus to half staff. We had not expected to explain to our children why teachers were openly crying in the hallway or why we rolled out yards of paper on folding tables so that students could write messages of support for Israel. We did not expect that Never Again had suddenly, shockingly, sickeningly become Again.

At Schechter, we resist the idea that we are always planning for the future and teaching students how to make choices, Jewish or otherwise, in the future. The upending reality of the war has made it clear that the future is always now. We owe our students an educational experience that is relevant to the world they inhabit and that can also stand the test of time. After all, our students are Jewish now, and they think and do and act now

As Jewish adults, we are keenly aware that we have to be survivalists. We must strive for the closest proximity to normal life possible for our students in a way that is positive, rational, determined and joyful. Our students still need to learn math, share their opinions about this week’s Torah portion, kick back during recess and decide how they would like to finish their projects in art.

Truthfully, we cannot know everything that lies ahead, and we will have to figure out some things as we go along, but we are meeting the complexity of this moment because we know exactly how to do it: stay strong and stay together, love each other and love Israel, and show our children that we keep going.

In Kindergarten teacher Emily Beck’s classroom, there are 15 chairs. All of them are blue, except one which is purple, and therein lies both a symbolic and practical example of the nuance and complexity of Kindergarten. “A lot of people like purple and want to sit in the purple chair,” Emily begins, “so the students suggested I remove it, and replace it with another blue chair, because it was creating too much conflict.” Naturally, that would have been the easy thing to do.

The purple chair remains in Emily’s classroom, however, and it is not going anywhere. It pops right out, different and imperfect in a sea of little blue chairs. “Symmetry is not always healthy for children,” Emily explains. “When everything is exactly the same, children do not have the license to experiment and make a mess or take risks.”

Emily took a step back in the first weeks of school to see how the coveted purple chair would play out among her students. Some students advocated for themselves and quickly recognized the opportunity for compromise—You had a turn yesterday, and I would like to sit there today —while others found it harder to relinquish the chair or handle the disappointment of sitting in a blue chair. “Learning to manage conflict and disagreement is one of the most important things that I can teach my students. We came up with a system, and did a turn and talk, so that students could suggest their own ideas.”

Emily often uses classroom elections to demonstrate sophisticated concepts such as democracy, compromise and negotiation. During class votes, she creates ballots with

visual representations of the options and sets up cardboard partitions so that students can cast their votes privately, free from the influence of their friends. “In one of our elections,” Emily recalls, “a student complained that he wanted to vote with his friend in order to tell the friend how to vote. We talked about the fact that you cannot tell someone how to vote. In a democracy, there is a range of opinions. Sometimes your idea wins and, other times, it does not.

“Ultimately, we’re problem-solving,” Emily says. “We have jobs in the classroom. Some of the jobs happen every day like line leader while others, like classroom greeter, might not if no one visits our room, for example. I have had students who were absent on the day of their duty and asked me if they could make it up. I thought hard about that because I could make the duties flexible, but I decided that they would have to wait until we cycled through their turn again. I feel very strongly that part of my job is to teach kids how to manage their emotions.”

Like their kindergarten counterparts, older students are finding their way vis-à-vis academic work and social dynamics, their Jewish identity and place in the world. Students are exposed to a multiplicity of opinions in classroom discussions or in the back-and-forth volley of small group hevruta-style learning. At the same time, there is also an incoming barrage of outside news and current events, and the drumbeat of social media that inevitably pierces students’ consciousness on some level.

The lightning speed changes in technology prompted Dr. Jonah Hassenfeld, Director of Teaching and Learning, Dr. Jenn Curren, Grade 6 Social Studies, Grade 6 Head Advisor and Middle School Social Studies Curriculum Coordinator, and Alexa Grasfield, who teaches Grade 7 Social Studies and Grades 4-5 Media Literacy, to develop curriculum around the challenging media landscape. They adapted Stanford University’s Civic Online Reasoning for high-schoolers to be appropriate for this age group.

Being media literate requires the critical analysis, active sleuthing and questioning that are native to Jewish learning. “This fits

Learning to manage conflict and disagreement is one of the most important things that I can teach my students.

emily beck, kiNdeRgaR teN teacheR

in so well with Jewish education,” Alexa says, “because we equip students with the tools to ask questions, consider information, construct arguments and support or challenge evidence.”

Ultimately, Alexa defines the goal as giving students a roadmap to the internet and information gathering so they can operate rationally and productively with a reasonable dose of skepticism. “Students are accessing media at younger and younger ages. We want our students to be digital detectives who are able to investigate the information they find online, and use the internet responsibly, safely and effectively. They should be able to parse through difficult sources and understand the reliability and trustworthiness of what they are consuming.”

Several framing questions guide Alexa’s Media Literacy class: who are the people giving us this information? What evidence can we find to support the information both from the original source and other sources? What do other sources say both about the author and the complexity of the issue? Is the author an expert on the subject, and can we trust an anonymous source? Students need to be able to evaluate the purpose of the content they consume. Is someone trying to sell them something or sway their opinion? Interspersed throughout the course are internet basics such as how to search for material or understand the difference between a website and web browser, or if a website is legitimate.

The Grade 7 social studies curriculum pivots around a yearlong inquiry question that both requires students to deploy and hone investigative methods as they examine a complex question in American history: what are the ideals on which the United States is built, and in what ways have we been successful or failed? With her students, Alexa focuses on skill development including annotating texts, note taking, reading and analyzing primary sources all of which can be used in any subject at school and in life.

In each unit, students cover a different period of time by looking at government documents from the United States, Israel and other countries around the world. Alexa recalls the seventhgraders’ discussions on slavery during colonial America. “There is the paradox of liberty. This

country was founded on equality, freedom and individual rights, yet the horrors of slavery still happened. One of our big focus areas was to tackle the nuances of this country’s founding ideology of religious freedom by looking at examples and deliberating the ideals that may or may not exist today. For instance, the Puritans came here for religious freedom and founded Plymouth colony, but you had to be a Puritan to live there.”

Alexa says, “I have found that students have a lot of opinions on the U.S. and what this country does and how it functions. We talked about how constructive criticism is a great tool for sharing your opinion and what you think should be done differently rather than just complaining.” As students progress through sophisticated concepts, knotty historical contradictions and multi-faceted chapters in history, they are not expected to develop definitive answers. Instead, they pore through enough readings and analysis of historical texts to make a claim and offer supporting evidence to prove their positions.

The current Schechter students are pretty wonderful. We talked about their responsibilities to help the [Israeli] students who had just arrived. They just got it.

m aya Za Jde, gR ade 3 geNeR al s tudies teacheR aNd team lead FoR gR ades

Robust social/emotional curriculum is baked into every aspect of life at Schechter in service of understanding each student’s personality, learning style and needs. Faculty and counselors partner with each other in and out of the classroom and they meet with students whether in circle time with Pre-Kindergarteners or during biweekly one-on-one meetings with Middle Schoolers. They talk about life, the weekend, friendships, school and the uniquely shocking events of October 7.

Grades 4-8 Mental Health Counselor Jenny Kaplan, Grades 4-8 Counselor Jamie Hirsch, and Hallie Boviard, Pre-Kindergarten-Grade 3 Mental Health Professional, describe the first days and weeks at school after the war began. Hallie recalls helping students deal with seeing their teachers cry. “It was important for kids to understand that the adults who keep them safe are hurting, and that’s okay. Many students had a heightened sense of awareness, and we also recognized that some children would know more than others.” The counselors add that while students witnessed teachers having hard moments, they also saw faculty modeling support for each other by jumping in instantly to cover a class or comfort a colleague.

Jenny references the Schechter Be’s, saying, “Students will be known, belong, be engaged, be inspired and be prepared. We live these words every day at Schechter.” Jamie concurs, “This is not just a lesson or idea that we cram for or suddenly put together to address kids’ fears and worries about Israel. We build towards this all the time. It is so important to hold space for conversations. We need to give the kids the long term ability to process information in a safe setting and to be self-advocates.” Hallie sat with one young student who wanted to draw rainbows. “This student was having a tough day, so what might just look like pictures of rainbows is actually a way to get through something without having to talk or make eye contact.”

On October 10, Lower School students sang HaTikvah with their grades while first-graders joined in a read aloud of Wemberly Worried by Kevin Henkes in order to brainstorm how to manage emotions, discomfort or find outlets for feeling better. Similarly, second- and third-graders convened to express their thoughts, concerns and questions about the unfolding situation in Israel.

For older students, Jamie and Jenny cite the specially designed programming by Rabbi Ravid Tilles, Director of Jewish Life and Learning, and the tekes (ceremony) convened by Dr. Jonah Hassenfeld on Tuesday, October 10 during which they read Tehillim, and recited prayers for the State of Israel, the safe return of the hostages and El Maleh Rachamim for those who perished. They also sang HaTikvah and Oseh Shalom. Yakov Dov, Grade 8 Hebrew and Jewish Studies Teacher and Israel Study Tour Coordinator, recounted his memories of the Yom Kippur War, giving students a firsthand account of living in Israel during wartime. Following the tekes, Jonah walked students through a program contextualizing the crisis. Students posed contemplative and earnest questions such as, “How was Israel founded?” “Where is Gaza?” “What is Hamas?”

School leadership had drafted an immediate response to shepherd students, and yet the reactions and emotions of the students themselves would guide much of the coming days. How would our students comprehend the emotional closeness, but physical distance of Israel, and hold fast to the joys of Jewish life in face of horrors

committed against the Jewish people? As students contended with this overwhelming moment and its inherent confusion, stress and sorrow, they did so buoyed by the unconditional support and safety that anchor everyday life at Schechter.

Grade 3 General Studies teacher Anna Gurvis reflects, “On the first day back to school, we made a rule that students would not talk about any graphic information they heard outside of school. I explained that some kids would know more than others and that only the teachers would share information. One student wanted to journal about the war, some students were frightened and wanted to be reassured that they were safe at school, and others were terrified because they had a very clear sense of everything going on.”

Anna’s colleague, Maya Zajde, Grade 3 General Studies teacher and Team Lead for Grades 2-3, looks back on the students’ genuine readiness to accept and befriend the Israeli students who began enrolling in Schechter in the early weeks of the war, some days on a moment's notice. “We were able to give the new students a sense of normalcy and security which they could not get in Israel because of the war,” Maya says. Schechter eventually opened its doors to 36 Israeli children at every age and grade level throughout the school.

Maya explains that the goals for the Israeli students were adjusted with priority given to their social and emotional comfort. “Many of them were very excited about academics and facing the challenge of being uprooted and starting a new school, but we really just met them where they were. The current Schechter students are pretty wonderful. We talked about their responsibilities to help the students who had just arrived. They just got it.”

Anna also commends her students’ openness and ability to parse through emotionally heavy material sensitively and thoughtfully. “Third aNNa guRvis, gR ade 3 geNeR al studies

graders are increasingly able to be problem-solvers, but they still want and need adults to lean on.” With her class, Anna read Even Superheroes Have Bad Days by Shelly Becker. “We used the book to talk about how everybody gets what they need. Kids want to know why someone gets a different type of chair in the classroom or more time on a project or different homework. Complex discussions happen all the time,” she says.

Further, Anna believes that studying Jewish texts at the young age of our students promotes critical thinking skills that apply to everything they do. “When we read, we do something called a comprehension check. What happened? Is this new information or was it part of a previous chapter? Can you make self-connections? We interact with text at a deep level, so by the time we get to our unit on characters, for instance, we are able to discuss traits and make detailed predictions about certain characters and why or how they act the way they do.”

Anna outlines several new integrated literary units on the Wampanoags, colonial life and the American Revolution. The goal is for students to learn how to write about nonfiction, and to view information from multiple perspectives as if they were a Native American woman or man, or a Tory versus Colonialist. Third-graders scripted a news broadcast about different aspects of Wompanoag life and, separately, colonial life. In small groups, they assumed the roles of interviewer or an expert interviewee. “This ties into Jewish Studies and our focus on empathy through the story of Joseph for which they maintain a Yoman Yosef (Joseph’s Diary) in which they log entries in Hebrew. They truly inhabit the concept of empathy,” emphasizes Anna, as the journaling exercises place students squarely in the mindset of Joseph or a citizen during the American Revolution.

“Everything needs to be in a real world context or else it is less engaging for the kids,” Anna continues. “Every year, for instance, we do a fall election unit depending on whether city, state, local or national governmental campaigns are happening.” Anna creates a slideshow with pretend candidates whose policies are composites modeled after real politicians, then students debate the mock candidates’ platforms. “We make voter registration cards and a ballot box so that they can simulate the entire process.

I want them to understand that every vote counts and they have a voice. This is life homework.”

We often refer to “the portrait of a graduate,” when we envision the eighth-graders who will soon move on to the larger world. These oldest students of ours, still just 12 or 13 years old, personify the hearts and minds we shape and nurture during their time at Schechter. Dr. Kim O’Donnell teaches Grade 8 Language Arts and an elective, “Propaganda and Persuasion,” both of which cover a range of intense and nuanced topics and books. Her classroom is often the scene for spirited deliberations and high-level discussions, namely the perfect microscope for seeing the breadth of our students’ identities, opinions and maturity.

A paperback copy of Justina Ireland’s Dread Nation, dog-eared and laden with Post-It notes, lies on the corner of every eighth-grader's desk. Through the lens of a zombie apocalypse set during the Civil War, the book addresses the legacy of slavery through the eyes of a formerly enslaved girl, now freed and forced to fight zombies in an alternate reality. “This is really heavy, serious material,” Kim shares. “We also read Chains by Laurie Halse Anderson, set during the American Revolution, about an enslaved girl who is trying to win her freedom by spying for the Patriots. In the novel, the main character finds people who are sympathetic towards her enslavement, but no one is willing to take a stand for her. There is such overlap among social studies, Language Arts and Jewish Studies. We draw students’ attention to the tough concept of being empathetic towards a character or a real person, but not being willing to stand up for them.”

Kim continues, “We will be reading To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee and also Night by Elie Wiesel which dovetail with the Holocaust curriculum in eighth-grade social studies. We tackle very complex questions about identity and what it means to be free, and then we connect this concept of being an upstander versus a bystander back to our Facing History and Ourselves curriculum. The kids get very involved expressing their thoughts and jumping into discussions, not just because it’s class, but because they have ideas they want to share.”

In her classes, Kim frequently turns to fishbowl discussions, one of the teaching techniques used by Facing History and Ourselves. The process begins with four to six kids in the middle of a circle engaged in open conversation, with other students listening from the perimeter. After the first group has had a few minutes to make contributions, new people move into the center. Kim explains that students listen quietly and just tap their desks when they want to enter and respond. “I start by giving the kids prompts about what we’re reading or questions they have. Sometimes I sit back, observe and perhaps answer a historical question, but the students run the discussion. It just flows.”

Kim marvels at the students’ ability to communicate respectfully with each other. “They build on each other’s comments and allow each other to have a chance to speak or disagree, but do so in an appropriate way. They pull things out of the books we’re reading and point out larger themes that blow me away. These types of discussions help them think deeply about a variety of topics and develop interpersonal skills that they need in the world.” Kim credits the bedrock sense of community at school as one of the main factors enabling students to be so comfortable speaking in front of groups about weighty subject matters.

“As a Havurah advisor and especially during one-on-one meetings with students, I can gauge how the kids are doing. Right after the war, some students had questions about the political or military aspects of the war, but most seemed to prefer the security of the familiar school routine and not talking about the atrocities in Israel. In recent years, we have had lessons on slurs and antisemitism because there are so many incidents. On the first day back after October 7, I thought, ‘OK, I am going into school, and I can ask my own questions, too’. Everything felt awful, but I was part of this community. I had not known what to expect or how my students would react. I have colleagues with children serving in the IDF and this is so hard for them, but we have so many systems and infrastructure in place that we were prepared. Fortunately, and unfortunately, we can handle this.”

In Kim’s “Persuasion and Propaganda” elective, the spotlight is on the internet, the complexities of social media, advertising and media literacy. After the assault on Israel, faculty members urged

students to step away from social media as much as possible with its graphic and pervasive coverage of the war. In the weeks that followed, the exponential rise in antisemitic attacks created an additional layer of disturbing content. Schechter’s “Wait ‘Til 8” initiative, which encourages parents to delay giving their children smartphones until they are in eighth grade, had perhaps never been more urgent.

[The first day after October 7] I had not known what to expect or how my students would react. I have colleagues with children serving in the IDF and this is so hard for them, but we have so many systems and infrastructure in place that we were prepared.

dR . kim

o’doNNell, gR ade 8

l aNguage aR ts

The elective begins with Aristotle’s rhetorical triangle which supposes that a speaker’s ability to persuade an audience depends on the speaker’s ability to capture listeners’ logos, ethos and pathos. Next, the course covers different types of propaganda techniques and persuasive appeals. “We start with U.S. history and look at the manipulation of photographs during the Civil War and the emotion of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. We move to World War I and the rise of Nazi Germany and how Hitler used propaganda to dehumanize Jews,” says Kim.

One component of the elective is helping students discern the veracity of memes and videos or images that go viral. “How do we know we are not looking at fake news? How do we distinguish between what is persuasion and what is simply information? We analyzed things like Super Bowl commercials and other ads for stereotypes,” Kim relays. “The kids really grasped the rhetorical triangle and were able to recognize the different factors at play. We have done a lot of visual analysis looking for symbols, slogans, figuring out who is the intended audience.” Against the backdrop of the war, antisemitism and the turbulence of social media, the “Persuasion and Propaganda” elective offers students a blueprint for dissecting and evaluating the often perplexing world around them.

“When we talk about having our kids be prepared,” says STEM Coordinator Dr. Amanda Strawhacker, “one of the most important things we can do is give them messy problems. We do not tell our students that there is a right answer and a wrong answer, and that they will figure it out if they work hard and keep trying the same thing over and over again.”

Amanda pushes into classrooms, partners with faculty members and often meets with students in small groups for which she designs a variety

of experiences around robotics, problem-solving, math, logic and puzzles. “It’s so important not to think of school as silos such as I’m walking into social studies class now so it’s time to think about civics and history or I’m in Jewish Studies now so it’s time to talk about morals and making Jewish decisions or I’m in math so I am thinking about algorithms,” Amanda reflects. “The world doesn't happen in silos. Kids have to have a sense of confidence that allows them to navigate when things are not clear.”

Amanda presented a group of third-graders with a popular abstract conundrum. They started with a cube that is made of smaller 3x3x3 cubes and were tasked with totaling all the cubes. Easy: 27. Then, Amanda posed a more complicated riddle: if we paint the outside of this cube, then throw it on the ground and the 27 pieces break into a million pieces, how many pieces have one side painted, two sides painted, three sides painted or do any of them have all the sides painted or none of the sides painted?

“Right away, the kids approached the question from many different angles and were totally invested,” Amanda recalls, relishing the circuitous trial and error of the students’ process. “I loved the moment when one student asked if he could use a calculator. We don't let them use calculators, but I said yes, and the student immediately recognized that neither a calculator or Google or anything else would solve the puzzle. He just had to work his way to the algorithm.” The students then tried coding the answer and were again sidelined.

For Amanda, the getting stuck, the challenges, the mistakes, the starting over and the unfamiliar are all at the core of the exercise. “I remember the kids saying to me, ‘You’ve done this before, right?’ They were shocked when I said no.” Amanda holds that offering authentic experiences is exactly what the students need. “Sometimes they resist initially and say, ‘I don’t want to do this. It looks hard.’ Great, I say, because if you get it right the first time, there is no meaning in it.”

At every turn, Amanda values integrating real world solutions into the curriculum. She points to Pirkei Avot 2:16: You are not obliged to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it. “I always tell my students that I’m glad they care about multiplication and division, but can they use those skills to think about water

conservation? Can they develop solutions that will make our lives better and limit consequences and harm? These are the questions we should be asking. They do not have to come up with the answers, but they should be coming up with the best approach to figuring out the answer.”

Amanda continues, saying, “There is so much confidence-building in recognizing that the world around us was created by humans. I want them to understand why it’s not so simple just to fix something. A lot of effort goes into fixing things, and there is a lot you have to learn which can feel frightening when we think about the real world. It's a disservice if we don't offer kids a place to explore those really complicated emotional responses.”

There are manifold parallels between grappling emotionally with the war and these STEMfocused activities centered on deciphering and designing, stumbling and regrouping. Amanda describes the Makerspace at the Wells Avenue Campus as a safe place in which “[students] mess around with robotics, take things apart, put them back together, print out and cut 3D files.” While Amanda recalls that students were largely quiet about their feelings after October 7, she observed profound therapeutic value for them in being physical and using their hands, so she followed their lead. “We were in such early, wounded stages, that the kids just threw themselves into whatever challenges I could give them.”

One sixth-grader independently fashioned peacethemed bracelets with the 3D printer, sold them and donated the proceeds to a humanitarian organization in Israel. “I’ve seen lots of kids around school wearing bracelets. It's another manifestation of empowering kids and showing them that what they make in the world matters,” says Amanda. “I don't think we would see that at a school that didn't offer so many opportunities for self-directed learning, problem-solving and exploration. It also demonstrates that everyone can do something. You might wonder what a bracelet does to change the fate of hostages in Gaza, but you can't think that way because then there's no point doing anything. I just don't see that disillusionment in the kids. I'm constantly humbled by them because they bring so much every day.”

Just next to the Makerspace, the Wells Avenue Campus Music Studio bursts and buzzes with sound, song, music and individuality. Grades 4-8 Music Teacher David Schockett ‘03 characterizes music at Schechter as so much more than a class that it is best described as a department. He teaches five different curricula, directs four different bands, and is collaborating with Eugenia Gerstein, Music Teacher and Director of the Music Enhanced Learning Program, to reshape the choir program. To David, complexity, no limits and open-ended interpretations are the essence of his teaching philosophy.

“I don’t make sets of rules and directions. What music is good? Well, I can’t define that for someone,” David says. When he introduces a new term, he tells his students, “I am going to start using this word. I am not really going to tell you what it means, but we’re going to talk about the family of things this word could belong to and how it could mean many things.” For some students, the intangible and abstract are challenging. David explains to his classes that he will lay out the

technical parameters they need to accomplish in an assignment, but he otherwise offers no direction about how they should complete their work.

“Some kids have a really hard time with this. I resist the notion that everything comes from the teacher until it’s free time and only then do students do what they want. Some students who are more experienced with creative thinking run with it. Other students sit with me and say, ‘What do I do?’ I tell them that I don’t know how to come up with something. You just try. You try stuff, and you see what happens. How do you try stuff? Well, by trying stuff.”

For all five grades David teaches, he focuses heavily on the concept that descriptions of music simply cannot be encapsulated in words. He relays to his students that a three-week unit on jazz will not make them experts, but will give them a foundational understanding to delve further if they are interested. “When we study rhythm, I explain that I cannot list all the ways to describe rhythm. I suggest some examples, but the kids have to come up with more. We do a lot of genre studies, but how do you describe what the blues sound like? I ask questions like that, knowing full well that there is no answer. Everything refers to everything else, and the second you name something, you change it. Genres are almost never defined by the people who actually make the music in that genre. No one wakes up one day and says, ‘I'm going to create progressive rock today.’ They were just doing their thing, but the people who write about the music are the ones who say, ‘How can I talk about this? How can I put this into a box?’ As soon as you put it into a box, the box changes. The next generation of musicians now has this thing called prog rock which is usually an oversimplified idea of what this thing actually is.”

David recounts a new assignment from this past year in which fourth-graders learned how to read notes in treble clef. He believes that knowing how to read music is one of the best ways to be able to write music. Students were directed to create a short melody that they would record, then perform themselves using Garage Band in the Music Studio. Next, however, David charged the students with writing down a new melody, then giving it to a classmate to read and perform.

“I told them there were no rules, but to write any melody they wanted of at least five notes. I jump

from kid to kid because they all have different experiences with this. One student might write really complicated sheet music, but the rhythms don’t work. Others might be stuck on the fictional idea that they don’t play the piano, so I tell them to put one finger on a piano key and press, and they realize that’s all it takes to start. Another kid will have a brilliant melody, but have trouble making the shapes of the notes on paper.”

David shares that one response would be to standardize the entire assignment and simply dictate the sequences of steps, but he always returns to the strategy of expecting students to demonstrate certain skills and produce a concrete outcome in their own way. “It’s openended, it’s hard and I just can’t tell a student how to get there or what it will look like.”

Jewish learning inherently requires looking at multiple opinions and viewpoints which forces students to get to the core of a topic.

daN savitt, gR ade 7 Jewish s tudies, gR ade 8 beit midR ash

Sharing as many possible ways of looking at an issue is central to Dan Savitt’s teaching method. As the Grade 7 Jewish Studies teacher and Grade 8 Beit Midrash teacher, Dan routinely introduces his students to thorny moral topics such as medical triage and the prioritization of one life over another. “My philosophy of teaching is that knowing information is not necessarily as important as knowing how to find resources,” he says.

Through hevruta-style learning, students are paired with a peer to examine rabbinic texts, gather evidence and debate their positions. “Jewish learning inherently requires looking at multiple opinions and viewpoints which forces students to get to the core of a topic.” In the unit on triage, students consider how a doctor might choose who lives or dies. Some hevruta partners are required to defend triage, while others must show that triage is not necessary and that, for instance, medical attention should be delivered on a first-come, first-served basis.

“Understanding Biblical texts as p’shat versus drash, namely contextual meaning versus more interpretative meaning, does not imply that one interpretation is more correct than the other, but it shows the students that there are different ways of studying text,” shares Dan. “This complexity allows for polyvalence or multiple meanings that can be gleaned from the same text. It’s also important

for me to slow the kids down so that they read for depth, and fully understand the words and value of what they have read. Some kids are able to make these leaps more easily than others, but mostly it comes with time.” Dan adds that framing text study in ways that are relevant to the students’ lives and world is a uniquely powerful way of showing how the practices of Jewish learning can be applied to the exploration of any topic.

The hallmark of Schechter’s social studies curriculum is its inquiry-based approach to student learning. Jenn Curren explains, “Our purpose as faculty members is to leave questions open for the students’ interpretation. As teachers, we really have to think about the sources we give students so that there is the opportunity for them to encounter evidence and draw their own conclusions. Sources cannot be tailored so that students can only arrive at one outcome. To make this experience a true research investigation for the kids, we are constantly making sure that the content is debatable enough to generate discussion.”

An overarching goal for sixth- through eighthgraders is to be able to defend their opinions in writing and student-led discussions. As Middle School students delve into increasingly demanding content, they are faced with real-life examples that are far from straightforward or concrete. Jenn shares that a guiding principle of social studies education is that, as students age and mature, they grapple with material that poses challenges that are more difficult, personal and emotionally intense. Younger students, however, begin with topics that are more distant from their own community and less powerful.

One of the most ambitious subject matters that Jenn’s students tackle in sixth grade is comparative religion through the examination of Judaism, Christianity and Islam from their divergences to their similarities. “Students are usually very curious about the differences, which might be related to the political atmosphere at the time,” Jenn observes. For the last two years, she has taken her sixth-graders to visit a synagogue, church and mosque or invited religious leaders to speak at Schechter. These visits included a chance to tour the buildings and talk with

religious leaders directly. “At this age, not all students can speak to the significance of finding commonality among religions or have the worldly understanding of how religion can drive conflicts. Their maturity will grow, however, as they study slavery and racism in seventh grade and the Holocaust in eighth grade,” she adds.

Jenn recalls several years ago when a group of students spontaneously began arguing about whether slavery or the Holocaust was worse. She recounts that some students rejected comparing the Holocaust to anything in history while others pushed back and suggested that an African American person might not agree. Ultimately, Jenn and the other social studies teachers read the book Vessels of Evil by Laurence Mordekhai Thomas, which compares slavery and the Holocaust, and provides additional facts and context. “It helped us as teachers be more prepared to frame this discussion for students the following year,” says Jenn. “Kim O'Donnell and I came away with this idea that it is useful to think about similarities of how and why things are evil and to draw connections among different historical time periods to learn, but it is not useful to say that one is worse than another because you don't gain any new or profound understanding from that.”

During meaty classroom debates, Jenn and her colleagues, Alexa and Kim, found that emotions, energy, and potential misunderstandings can run high among students. “The key idea in a class in which students partake in very difficult, charged conversations is that we teach them to assume the best of intentions from their peers and to correct mistakes and misunderstandings when they occur. We can only discuss challenging topics in an environment that is psychologically safe for the kids. They need to understand that if they share an opinion that is frustrating for others or make a mistake, they can talk it out, move on, and still be friends. This is a school in which we have the infrastructure for kids to try out ideas, be vulnerable, and seek out additional evidence in order to come to an understanding.”

The colleagues developed a short, optional form for students to keep on their desks during class. Students can respond to blanks on the form such as: “When someone said in class, I felt , and I want to address it, not let it go.” They hand

in the forms anonymously after class, which helps teachers to pinpoint moments that were especially complicated or to work through conflicts in which one student felt a peer had made comments that were unfair, racist or otherwise off-putting.

Jenn continues noting that social studies topics are often challenging from a moral and political standpoint. “One of the things I appreciate about teaching at a Jewish day school is that there are moral texts and principles that I can use as checkpoints. There are moral lines that are consistent to some degree within our community. As someone who studies history and social studies and values the Torah as a sacred text, I am driven by the beautiful concept that all humans are inherently valuable and that human life is valuable.”

This is a school in which we have the infrastructure for kids to try out ideas, be vulnerable, and seek out additional evidence in order to come to an understanding.

dR . JeNN

cuRReN, gR ade 6 social s tudies, gR ade 6 head advisoR

aNd middle school

social s tudies

cuRRiculum

cooRdiNatoR

Themes around kindness and caretaking are ingrained in the psyche of our school and in our expectations of how we interact with each other and the larger world. The messiest example of this lesson is best displayed by the Barn Babies visit to Gan Shelanu and the accompanying feathers, fur and dander. Preschoolers have an opportunity to pet little animals, and also to feel what it is like to be a veterinarian or treat an animal respectfully. Trena Norton, Parparim Lead Teacher at Gan Shelanu, sets up a mock veterinarian’s office for students so that they can handle pretend medical equipment, and imagine checking an animal’s heartbeat with a plastic stethoscope.

As part of her role at Gan Shelanu, Trena crafts a yearlong schedule of diverse visitors and interactive programming which is intended to expose and introduce the preschoolers to different people, jobs, living creatures and customs. The robust list includes a Thanksgiving puppet performance, a presentation on Native American awareness, a rainforest reptiles show, visits from community helpers and touch-a-truck experience. Trena is also working with a Sri Lankan friend who will stage a traditional dance for the children.

At the same time, Judaism and Israel come to life vividly at Gan Shelanu through Hebrew stories and songs, holiday celebrations and the full-scale transformation of the preschool into a mini Israel in April. “We take an imaginary plane trip, and

every classroom is completely revamped to be a part of Israel.” Trena says. “One room is Jerusalem, another is Tel Aviv or the desert. Younger toddlers pretend to milk goats and cows on a kibbutz or pick fruit at an orchard. We spend a full month ‘in Israel’ and also learn about Israeli artists.”

Gan Shelanu’s library boasts a rich collection of Jewish and Israel-themed books as well as those about other countries and cultures. To illustrate diversity and differences to such young children, teachers rely heavily on multiple stimuli such as books, visuals, tastes, smells, stories that depict different types of people, hands-on learning and play. “This age group does not necessarily have the words for what we are learning, so our work as educators is to implement as many ideas and play-based activities as we can,” says Trena.

At the heart of all these lively programs and multi-sensory experiences is the opportunity for preschoolers to be first-hand participants in how other people or creatures live and work. Similarly, Emily Beck approaches the idea of perspective with her students through a mini unit on community.

“We list different communities that we are part of,” Emily says as she lays out this concept for the class. “There are many interlocking circles. We have our class community, our school community, a family community, maybe a shul community, maybe a sports team or a dance group.” Emily and her students explore that even within the kindergarten or Schechter community, there are many different ways that people are Jewish.

“The kids and I have a lot of conversations about the importance of being curious and tolerant of the wide variety of religious differences, and how to make it comfortable for other people to do what works for them,” Emily shares. “We talk about the parshat hashavuah and also make analogies about how people choose what to wear to school or what kind of music they like, and that we also get to choose what our kind of Judaism looks like.”

The weekly parsha is always a powerful and relevant mirror to the real world for Grades 2-3 Jewish Studies teacher Orly Bejerano as well. “We focus on keva and kavannah which mean the regular things we do and the words we pray, and the meaningful things we say and intend. The ‘regular’

is to come to tefillot and to focus, to put aside all the distractions, the news, whatever is going on at home or school. Then, there is the kavannah, which I explain to the kids, strengthens us as a community. We are a community of second-graders, of Schechter students, of Massachusetts residents and of all the Jewish people in the world. The circle gets bigger and bigger.”

After October 7, Orly adapted her morning routine with students. “When we say the Amidah, we turn to the east, towards Jerusalem, not only so that we can have a better day, but so that Israel can have a better day. We turn to the sun, to the light, because we want a better world. Now, we have added לארשי תנידמ םולשל הליפת (Prayer for the State of Israel) without explicitly discussing the war.”

Then, in December, Orly had a sudden, harsh realization: Hanukkah would arrive as would the word “המחלמ” (war) when she talked about the Maccabees in class with her students. Usually, Orly’s class plays the card game War, but she stopped short. “How could we do that with the Israeli students in my class who are here because of the war? Some of their parents are fighting in Israel. Some have parents who are doctors and went to Israel to help. We have to refer to the war to discuss the miracle of Hanukkah, but I immediately focused more on miracles.”

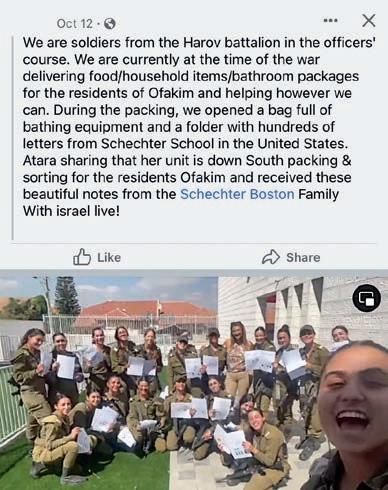

Orly is steadfast in telling her students to be the light, to make good choices and to do so with dignity. “I tell them that, sometimes, there are bad forces who are against Jews, but we stay positive and defend ourselves with honor. Every week, we write letters to Israeli soldiers and receive heartwarming responses from them. The younger students do not have the same understanding of the war or antisemitism that the older kids do, but they are in a safe Jewish environment at school so they see their Jewishness as something strong.”

The school year is half over already now, but there is much ahead. We are months from the

beginning of the war, but in the infancy of this unwelcome post-October 7 existence. Even the oldest students at Schechter have not lived through a period when Israel was at war, but perhaps, as Rabbi Tilles says, “we throw around the word ‘unprecedented’ too often.”

“I was teaching Kohelet to eighth-graders,” he recounts, “and we came to this well known line— there is nothing new under the sun—basically, that saying anything is unprecedented is a falsehood. I began to understand it, and I think we depended on this concept a lot when we came back to school after October 7. This is unprecedented in our lifetimes, but it is not the first time that the Jewish people have faced existential dread. I feel that I can say with confidence that in our students’ lifetime, no matter when that is in their youth or their teenage years or their adulthood, but definitely in our students’ lifetimes, they are going to face unprecedented realities that we cannot possibly predict.”

There is the kavannah, which I explain to the kids, strengthens us as a community. We are a community of second-graders, of Schechter students, of Massachusetts residents and of all the Jewish people in the world. The circle gets bigger and bigger.

oR

So we come back to this concept of training our students for the unknown. “We can't do that,” Rabbi Tilles says, “because Kohelet is telling us to expect the unexpected. Sometimes we don’t want to do this hard work because it’s exhausting, but the fruit of the labor is worth it, and there is no alternative, not for the teachers or the students. It takes a lot to demystify complexity and untangle the knots, but you cannot avoid it. Our responsibility as educators, and specifically Jewish educators, is to develop Jewish habits of mind in our students which is a way of thinking. This is how they learn perspective and how to be ready for the unforeseeable.”

It is true that we have seen some of this before, and that there is so much we cannot predict, but we are strong. We evaluate and reevaluate ourselves and our program again and again to make sure that what we do is in service of our goals and purpose. Can a purple chair or rabbinic text study or a discussion about the Civil War provide students with the foundation to lean into complexity now and throughout their lives?

Well, it’s not quite as simple as that because life isn’t simple, but in a word, yes.

a N iN tervie W W ith:

If it were not for advice from his mom, and some egg drop soup, none of this might have happened to Sam Levenfeld.

Sam was midway through his sophomore year at Indiana University. It was time to declare a major, but he had come home feeling adrift and uninspired. “My Mom and I were spitballing and she said, ‘You’ve always liked to have people over, cook, entertain, so how about culinary school?’”

Hmmm, thought Sam, plenty of people like to cook and entertain, so culinary school seems like a stretch, but some of Sam’s friends from Schechter, Gabi Remz ‘06, Ben Chartock ‘06 and Joel Newberger ‘06 had recently come over to hang out, and he had made them egg soup which they had loved (and still famously talk about as “that time you made us the delicious egg drop soup”).

These days, the only difference—and a remarkable, storybook one it is—is that when Sam’s friends stop by to eat, and they still do, they are walking through the doors of K’far, Laser Wolf or Jaffa Cocktail & Raw Bar, three of the trendiest, hotter-than-hot, line-outthe-door restaurants in New York City where Sam is the now Head Chef. His meteoric rise in the restaurant industry all the way to this trendy trio in Brooklyn can be attributed to

his unfailing eagerness to learn, a willingness to start from scratch and, of course, the fortuitous conversation with his mother.

“We went down to Rhode Island to check out Johnson & Wales,” Sam recalls. “I didn’t know anything about it, but it looked pretty cool. I had lost interest at Indiana, and there was something in me that was not going to let that happen again. From the beginning, culinary school just gave me the structure I needed. I fell in love with the regimen as much as the cooking. Even after all these years, there is just so much I adore about being in the kitchen.”

Mornings began at 7 a.m. sharp with a crisply ironed chef coat and a clean shave. “One teacher would run a credit card up our faces to test for stubble,” chuckles Sam as he relates the rigor and the quirks of the daily drill. His lack of experience proved to be an unexpected benefit because his approach was one of complete humility and no preacquired bad habits.

“I was totally honest about having to learn everything from how to hold the knife to tons of terminology. It lit a fire under me.” Sam recognized that consistent practice would yield tangible results quickly. “Practicals” entailed making a number of dishes that

would be rated by the teacher. Broken sauces and the proverbial fallen soufflés were the impetus to stick with the repetition. Soon enough, Sam was in a groove and making consistent progress, ultimately graduating magna cum laude with a B.A. in Food Service Management.

Being a chef involves more than cooking, explains Sam. “I was really interested in the accounting classes. It’s funny because you typically spend eight to 10 years on the line cooking, just trying to get better before being promoted. Then one day, someone says, ‘OK, you’re ready for management,’ but if you have only ever worked the pasta station, you have no idea how to deal with staffing, missing deliveries, ordering and budgeting. Johnson & Wales gave me a well-rounded understanding of the restaurant industry.”

By junior year, Sam was working at a small company, Fireworks Catering. Under the tutelage of a seasoned chef and amidst preparing hundreds of gourmet sandwiches, Sam relished his first paid job. Next, he moved to Red Stripe, a modern French brasserie. He was immediately smitten by working in an open kitchen which has remained his preference to this day. “It’s completely different,” he points out, “because you can see into the dining room and watch

It’s actually the best compliment when people say something tastes just like grandma made it. You can connect with people through food on a very deep level.

people enjoying the food that you’re cooking. The diners can also observe you, so nothing is hidden. It helps you develop really good habits and self-awareness.”

Despite being hooked by the frenetic pressure of serving 400 people on a weekend night, fixing mistakes in real time and acclimating to the non-stop rhythm of a busy kitchen, Sam’s next stop in Providence was at Metacom Kitchen, a three-staff restaurant owned by a single chef.

“There was an emphasis on ingredients and molecular gastronomy, so I was making fluid gels and using a freeze-dryer which was completely new to me. The chef was incredibly talented, and he took me under his wing. I had time to think about what I was making, and not just how we would serve 400 people. The chaos of Red Stripe and the balance of Metacom taught me about different parts of the kitchen.” Sam notes that many restaurants have a narrow template to follow because guests have expectations about the cuisine and menu, but the intimacy of Metacom afforded him the opportunity to propose menu items and to experiment.

After nearly six years in Providence, Sam yearned for a more expansive restaurant

scene, so he accepted a trial at a worldrenowned, 3-star Michelin restaurant in Chicago. “You work a shift or two, so the chef can see how you move in the kitchen, your knife technique, how you get along with other people.” He snagged a plum spot on the kitchen line-up staff, but instead of feeling that he had reached the “pinnacle of everything,” Sam lasted two months in the withering, dog-eat-dog environment.

“I had heard rumors about this restaurant being abusive, but it was worse than I expected,” he remembers. “People would scream directly in your face, tell you you’re not good enough. If you turn around, someone would take your apron or steal your knives or your cutting board. No one was working together. The people who had been there longer and were higher up, looked worn out. I wanted to be a great chef, but not like that.”

A mere three weeks later, Sam landed at Momotaro, a Japanese restaurant in Chicago which is part of the Boka Restaurant Group, one of the most successful such groups in the United States, and for which Sam still works. Starting as a salad cook, he imagined that chopping vegetables would be, well, chopping vegetables, usually a comparable task regardless of the cuisine. Japanese

techniques turned out to be completely different.

“I started all over again with new terms, even just the way to use my knife. The environment was awesome, so I was really growing. All the cooks just pushed each other to be better. I developed a great relationship with my Sous Chef who became one of my mentors by showing me, not telling me, what to do. Every day, he greeted every person who worked at the restaurant by name, and made them feel important. He was always measured. I knew that was what I wanted to be like. I followed him across the street to open another restaurant in the group, Cira, where I started at the bottom again as a salad cook and eventually worked my way up to Sous Chef.”

As Sous Chef, Sam was steeped in management and financials from Excel spreadsheets to coding invoices and calculating food costs, staffing and scheduling. “For example,” Sam says, “if you get a delivery with meat, stuff for the bar and produce, there are formulas to determine how much to charge to food or liquor costs. Where can you spend less? How many people do you need per shift? It tied back to what I had learned at Johnson & Wales, and then the head chef went on vacation for three

weeks and I was in charge of everything. It taught me that I was ready to put it all together.”

Sam knew he had made it to the next tier of the restaurant world, but he had another plan in mind: cooking in a zero-pressure falafel shack on the beach in Tel Aviv for six months, maybe longer, just to be in Israel.

“My Executive Chef at Cira put me in touch with the well-known Israeli chef, Michael Solomonov, who I work for now. He had some suggestions for me, then the second wave of COVID-19 hit, and Israel shut its borders.” The Israel dream had been shattered yet, conversely, this was the moment “things got really good,” Sam recounts. “Chef Mike asked if I wanted to move to Brooklyn to work at Laser Wolf, a restaurant he was opening. Not exactly the beach in Tel Aviv, but it felt right to me.”

From the moment Laser Wolf opened its doors for dinner atop the Hoxton Hotel, it was a hit. The Israeli-style shipudiya or skewer house boasted an open grill in the center of the restaurant, big-hearted hospitality, a panoramic view of the East River and an unusual prix fixe starting with perfectly executed, unlimited salatim. Sam recalls the surprise at being reviewed by the New York Times only three months after opening—unheard of!—but the team had earned the accolades.

Just a few months in, Sam was promoted to Executive Sous Chef which primed him for his next role as Head Chef at sister restaurant

Sam often thinks about the role Schechter has played in his life and career. “Schechter taught me how to treat people.”

K’far, the new lobby-level all-day café in the Hoxton. Just several floors down from Laser Wolf, he took on the stress of ironing out start-up logistics.

Sam explains that designing a menu means preparing and tasting everything first. “You have to teach the cooks how to make everything because they're the ones who actually cook it, night in and night out, for the guests. I was doing all of that, but I was never really on the line or the grill station making food and I missed it. Once things were running smoothly, the most important thing to me was to get back there with the cooks. Giving them pointers, helping them when it’s busy, giving them time to taste and develop new skills is so much better than crossing your arms and saying, ‘Do this, do that.’ How much more does it mean to someone if you actually show them how to do it?”

Then came the third establishment at the Hoxton, Jaffa Cocktail & Raw Bar, the “rulebreaking, anything goes” cousin to kosherstyle Laser Wolf and K’far. In under two years, Sam had skyrocketed from Sous Chef at Laser Wolf to Head Chef at K’far and Jaffa under the Director of Operations. “There are so many days that ‘imposter syndrome’ can eat you up. I’ve had a lot of support and guidance, but there are days I just have to figure it out.”

Sam often thinks about the role Schechter has played in his life and career. “My education was so solid. I learned to write and speak well and, as a chef, you think critically all the time. I use my Hebrew and educate people about Israeli and Jewish

cuisine. It’s not just putting chickpeas on a plate and calling it Israeli. Growing up, I thought our Ashkenazi chicken soup and matzoh balls were Jewish cooking, but it’s a melting pot. We’re telling a story by spinning the menu with influences from Yemen, Iraq, North Africa. There’s no shame in doing a traditional recipe well, and I don’t want to be so innovative that the food is unrecognizable. It’s actually the best compliment when people say something tastes just like grandma made it. You can connect with people through food on a very deep level.”

Sam offers a frank assessment of his time at numerous restaurants. “To the core, Schechter also taught me how to treat people. I’ve seen people be abused, I've been abused, and I just won't let that happen to anyone else. Since I've been in charge, I haven’t yelled or raised my voice once. There are appropriate ways to discipline people by pulling them aside for a real conversation so you're not embarrassing them. Everyone deserves dignity. If you ask someone to take out the trash, you’d better do it, too. There are so many immigrants and marginalized people in this industry. Knowing people from different backgrounds is the best part of the job.”

sam is unpretentious when he says, “I’m not here by accident. There are hard days, but it feels good.” He loves it all: the view from the swanky Brooklyn rooftop, the electric synchronicity of good teams, the high-level strategy. From the beginning, Sam has not only been open to an uphill learning curve, but has been energized by it. He has embraced the step-by-step methodical process of getting better at his craft, just patiently and simply getting better, day after day, year after year.

After all this time, Sam espouses the same awe and appreciation for being the Head Chef at three ultra-celebrated restaurants as he did when he was starting at the bottom, more than once, learning to do his best fine julienne in the back kitchen.

aN

iN tervie W W ith:

Student Council President at Schechter.

Volunteer for Gateways: Access to Jewish Education while at Newton South High School.

Summa cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Washington University with a B.A. in Biochemistry and a Minor in Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies. Recipient of the Harriet K. Switzer Leadership Award and the Shepley Outstanding Senior Award.

Speaker of the Student Union Senate and undergraduate representative to the Washington University Board of Trustees.

Research Assistant at Washington University School of Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital and Lurie Children’s Hospital.

First-year student at Stanford School of Medicine. Yes, there’s more.

One of a handful of medical students admitted to the ultra prestigious Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program at Stanford, which includes belonging to a cohort of students in different schools at the university who benefit from professional leadership development, interdisciplinary collaboration and a full scholarship for the entirety of their study.

Gaby’s star power is consistent and palpable with a wow factor list of impressive accomplishments and recognition. Her medical school journey may have just begun, but Gaby acknowledges the inspirations that have long guided her, both knowingly and in retrospect. In her affable, straightforward way, she recalls, “I was interested in medicine early on. I knew I liked science. I knew I liked working with people and my dad's a doctor, so I got to see firsthand the impact a physician can have on patients and the community. I went into high school and ultimately college with this interest, but I don't think it was until I got into clinical settings through volunteering and shadowing, started doing research in a lab, advocating for students through student government, and working as a teaching assistant for some biology courses, that I realized medicine was truly the best way for me to combine all my interests in clinical medicine, research, teaching and advocacy.”

The culmination of Gaby’s interests and determination posit her right where she should be. “Medicine is the way that I will be