SOUTHERN CULTURE ON THE FLY

MORE FIGHT, MORE TOUCH

Load shifted closer to the hand prioritizes feel and recovery. 25% greater strength for increased pulling power.

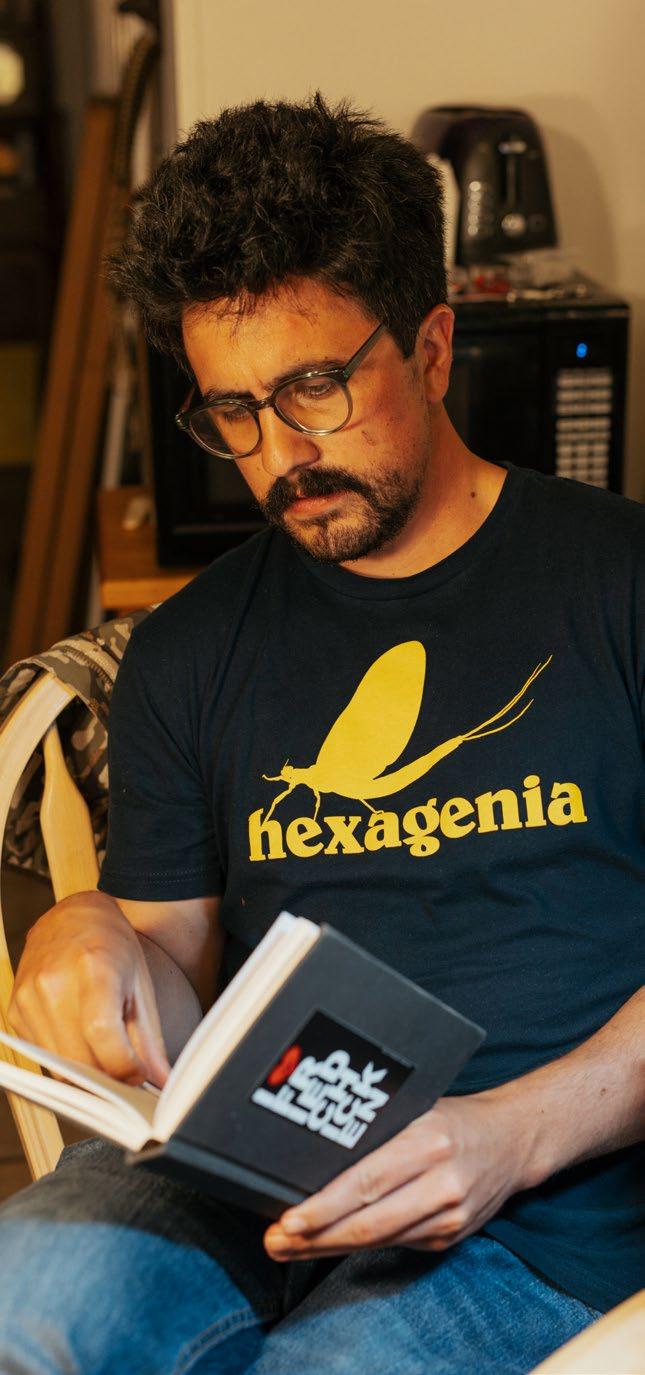

All about Frank. By Frank.

All about Frank. By Frank.

I was born in 1985 in Oklahoma and when I was 7 we moved to Western Kentucky to a rural county 70 miles north west of Nashville, TN. My dad and uncles grew up swimming in the Guadalupe River in Texas visiting family and fishing for speckled trout, reds, and pompano off oyster beds and sea grass while my grandpa was stationed in the Florida panhandle. I grew up seeing photos of my dad and uncles in far off summer places I’d have to find on a map like Lake Of The Woods in Ontario where they would hire out a float plane and catch pike and musky while they wore their

Atlanta Braves baseball caps. I was lucky enough to grow up fishing for smallmouth bass on small water all over the state of Kentucky. Over the last 20+ years I’ve tried to refine my approach to catching smallmouth bass every year in every season. The last 5 years I’ve been chasing musky with my fly rod. It has never gotten old. In my early 20s after working carpentry, construction, and factory jobs I apprenticed for 2.5 years

to become a tattooer. For the last 15+ years I’ve been lucky enough to make all my income on tattooing , selling antiques, folk art, and painting. My work relies heavily on my interest in fishing, camping, kayaking, and hunting so I’m thankful to have a job where i do have enough time to fly fish for smallies, musky (when the water temp is cooler) and stripers almost 150 days every year and be able to hunt hard for deer and turkey season. I currently live and work in Bowling Green, KY with my wonderful girlfriend, step son, and all our animals. I book tattoos and accept painting commissions and can be reached at frank armstrong tattoos at gmail dot com

Photo: lake lanier, samuel bailey, March 2023

Photo: lake lanier, samuel bailey, March 2023

8 drawrers and drawrings

frank armstrong

26 a letter from john 28 haiku

by

32 doing villain shit in GRACELAND

by

photos: gecko

46 looking at ghosts and empties

by

photos: gecko with art by vaughn

62 southern striper open 2023 results

alpharetta outfitters

photos: alan broyhill

64 on the clock by michael steinberg

67 the whaler and the angler

by: dustin schouest

art: tyler hackett

74 salsa saved my life

by: craig haney

photos: sam bailey

the dauphin of mississippi art: drew wilson john agricola the lost dauphin of mississippi cochran

Spring 2023

issue no. 47

Managing editor

John Agricola

Editor at large

Michael Steinberg

Creative Director & Chief of Design

Hank

Ads & Marketing Director

Samuel L. Bailey

Merchandiser

Scott M. Stevenson

Media Director

Alan Broyhill

contributors

Craig Haney

The Dauphin of Mississippi "Gecko"

Dave Fason

Paul Puckett

Mike Benson

Shawn Swearingen

Dustin Schouest

Devin Davenport

Vaughn Cochran

Pat Tragessser

Tyler Hackett

JoEllen Wilson

John Agricola Sr.

Managing editor emeritus: David Grossman

Creative Director emeritus:

Steven Seinberg

copy editor emeritus:

Lindsey Grossman

ombudsman:

Dale the Gamekeeper

general inquiries and submissions: southerncultureonthefly@gmail.com

advertising information: southerncultureontheflysam @gmail.com

cover image:

Frank Armstrong 2023

My career path a glint in my father’s day my 10-year-old father Atlanta Cyclorama. For the 1950s, it must have see the sculptured Confederate troops standing before painted landscape of under siege. It was formative career as an artist of southern themes ranging from Lee to Martin Luther became a real estate family farm into a series He moved away from he wanted me to do passionate about, like But I didn’t know what about, so I too tried art, short while, a curator museum.

Then he took Bahamas, and got my Alabama on faraway bonefish. personality, so, with most given the opportunity no matter what. I imagine fish to be sort of like the drug DMT, where you middle of the trip, bonefishing as revelatory. While trips and world-bending expansion can only take grappling with nature head-on can take you the memories of large encircling themselves chain to the many trips skills up to chase the have never caught that or been certain of God’s are both wrapped in mystery. my ultimate high will be

Knot: Elements

began before I was father’s eye. It began the father got lost in the For a kid at the end of have been enthralling to Confederate and Union before the panorama of a the city of Atlanta formative for his later southern iconoclastic Elvis to Robert E. King, Jr. Then he developer turning a series of subdivisions. art. As I grew older, do something I was art had been for him. what I was passionate art, becoming, for a curator of a small private me to the Grand Alabama ass hooked I have an addictive most things, if ever I would do it again, imagine my pursuit of the ayahuasca-based you seek God in the bonefishing can be just mind-altering drug world-bending consciousness take a person so far, nature and her environs much further. From groups of bonefish in a chasm of daisy trips later building the the solitary hunters, I that double digit bone, God’s presence. They mystery. But someday be reached. If I can

stay in it long enough to get another opportunity. Hell, maybe a permit even… The great distance and expense of bonefishing led to my preoccupation with local Alabama carp. The carp flats experience was so similar that I began losing myself in the imaginative world of a guide’s mind. Soon I was scribbling those ideas in a journal that led me to bang out my experiences on a blog, and as a freelancer for some hip fly fishing lifestyle magazines. But fishing tales are never just about fishing. Once, I wrote a story about taking my girlfriend on a combo trip to Bozeman, Mont. I was there to get certified as a casting instructor, and brought her as a serious step in our relationship. It was a “who are you” trip that amorously morphed into conceiving our first child. We argued most of the trip, and after a sad Outback Steakhouse dinner alone (on my birthday), something changed between me and her. I gave up on trying to certify myself as a casting instructor. I was overpowering my forward cast and causing a tailing loop anyway, so I had already failed the test, and I gave in. I vowed to become a high school teacher, and put childish dreams of pro fisherman aside. “I could be a pro writer though,” I thought. I could write as a side hustle. Then one day my cast instantly improved once I fixed the twoinch creep and the overpowering press of the thumb. Funny how such a small problem can destroy your confidence, knock you off track from chasing your dreams. And at the same time, maybe help you discover them.

Fair notice bonefish. I am still coming for ya! And you can bet your ass I’m going to write about it.

Don't judge the man

Too fat to fit into jet

He loves chicken OR Judge not, lest ye be squeezed into a tiny jet with chicken grease lube.

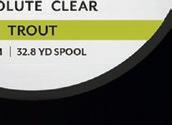

IT TAKES ONLY ONE SMALL CHANGE TO CATCH MORE FISH.

ABSOLUTE TIPPET

UP TO

40% stronger

WET-KNOT STRENGTH THAN PREMIUM COMPETITION

by John Agricola photos: Gecko with art by Vaughn Cochran

by John Agricola photos: Gecko with art by Vaughn Cochran

As I stood in the bar at Blackfly Lodge, I saw a salon style hanging of 20-plus pound permit hung in every corner of the building. From floor to cupola there was the Golden Bear’s Yeti cup, and many other elites that I dare not mention. Golfer Darren Clarke had pictures with four permit from one day, and six for his entire trip. Surely I was due for a permit having fished for 25 years of my life. In Montana, a guide named Cezanne once chided me, “You are too young to catch a permit,” when I indicated that this feat was my dream. Well, I had grown as an angler since then. So the duality of my spirit that felt I had grace on my side urged me to believe in myself. What did a golfer like Darren Clarke have that I did not have as an angler? A lot, actually.

That feeling you get when you think you lost a large sum of money on a bonefish adventure, only to find that you do in fact have the stones to go, even though your father- inlaw is rejecting his new lungs, it is your son’s fifth birthday, and your dad will be transitioning into a home health situation to combat the effects of his Alzheimer’s disease; yes, that feeling is akin to feeling as though your wife may want to get a divorce because she hates your guts and this is revealed with every passing glare made available to you in the halls of my home. One hall is more accurate to the story. To say we have halls plural sounds pretentious as shit. But so does spending copious

amounts of coin on you and your father’s bonefish memories during a recession.

It was going to be the story of my father and I doing one last fishing adventure together in the Bahamian island chain where our love for saltwater fly fishing began. For those who have little taste for expensive bonefish trips, I don't blame you. When my mom found out that I took so much from the money left to me by my grandfather for a bonefish trip, she quickly exclaimed, “You don’t have the money to take a cushy-cushy bonefish trip!” Maybe I don’t, but it seems like some people just don’t understand why other people pay so dearly for memories, and others fight tooth and nail for survival. This isn’t about the carbon expenditure to pursue bonefish, or the catch and release ridiculousness of trying so hard to feed a self-absorbed permit only to put it back after. We all pay fealty to the rules of conservation because, after all, some future schmo will catch this same fish again for their own taste of a permit memory. In this way, tourist endeavors are of paramount importance to the survival of the species we so love to target in transient ways.

My father was hospitalized after he caught covid. It was during his week-long convalescence that I realized he was too frail to make the trip to Abaco. For a while I said screw it altogether, but I couldn’t get the memory investment back, so I started trying my friends wealthy enough to buy it at a discount. Then when

that failed, I tried giving it away. This latter effort was the way. My good friend the Dauphin of Mississippi was able to go, and he even had enough scratch for a plane flight, so that cinched it. We would rendezvous on Abaco island at the preeminent lodge in Abaco— Blackfly.

On the way to the airport my mother called minutes before getting on the plane and told me that my father-in-law was dying, since his kidneys were shutting down. My wife was not speaking to me during this time because she was so royally pissed that I decided to go on my trip anyway. Gecko the photographer was with me, and we were about to board a private plane with our great benefactor, Squire Cobb. If not for Squire, we would not have been given the opportunity to fish at Blackfly because we were not members of this elite bonefish and permit club.

The Dauphin had never cast at bonefish before, and I had never seen a black-tailed devil before, otherwise known as a permit. Squire was responsible for my bonefish initiation a decade ago, and I had always dreamed of pursuing this fish again. Hurricane Dorian had in many ways set the stage for our adventure in that the lodge I used to frequent many years ago had been razed and the people had been devastated by the force of 185 mph winds. Abaco was a new island to me, and this place when we arrived was like no full service lodge I had ever been to. The warmth of the owners was special,

and I had never seen so many permit photographs as I saw in the foyer of the lodge.

As we arrived they made us so comfortable that the whole time I was thinking I did not deserve this trip to fly fishing Graceland. I am reminded of Unforgiven when Clint Eastwood’s character said “deserve's got nothing to do with it.” Gecko suggested before we got on the plane that for a 25-year-old who had not made it financially and a 30-something who was performing a bad Hunter

S Thompson imitation that we are actually the villains in this story. In the center of our bonefish adventure was a constant reminder of how Dorian had affected this place. In the middle of the expanse of the mangroves was a gargantuan 70foot yacht that during the storm had washed into the mangrove jungle with the storm surges. As it turned out, there was an Australian couple who had been stuck on this ship for over three years since the surge. I considered my three-day fishing trip to be a lot different than these people’s trip for the extreme duration of their adventure. They had a dinghy they used to resupply in Marsh Harbor. I tried in my mind to savor every moment of this experience, because in a blink it would be over. I did not have the luxury of being stuck here. After all, my father-in- law was leaving this world.

From day one I tried to catch a permit. The first ray we found flapping its wings with a permit enthroned atop the ray as a remora for crabs kicked up, and this filled my body and shaking limbs with adrenaline, and I overpowered my cast, flinging the tip of the rod off the midsection and at the fish. I knew I might only get one more chance. When I did see another, it went better. Probably in my mind only, because I put it right on the fish. He even tailed up and looked hard at the fly. Then this experience was over. It took 10 minutes before the fish was off his feed and spooked off. To me in the permit game that was an eternity

and 10 minutes of action I never thought I would be blessed enough to get. So as I considered my villainy, I also felt that this was just God’s grace. The sun shines on a dog’s ass every once in a while and on this day I was that blessed mongrel. The next day, I went with Gecko and guide Trevor and we had a proper session. I thought about my family often as I enjoyed all the amenities of a first rate lodge. That does not exonerate my villainy or the choices I made to get here, but as the grayed out ghost of my father’s voice reminded me: “you only go ‘round once, so make it count.” Gecko got the only shot at a permit on day two, and he false casted over the fish and it saw the fly line and totally bugged out. Because we did not have all the time in the world as the Australian mariners had, stuck in the mangrove jungle, we settled in for some bonefish action. Everybody who knows grace understands that it is about as common as a solar flare in a photograph. Bonefishing is like that in many ways because these ghosts of the flats are a “now you see ‘em, and now you don’t” presence. We caught a good number of average sized bones, but we mostly fished for the pinnacle of fly fishing— permit. For these fish they must have smelled the villain on me, because I never saw another one after Gecko blew his fish. As a matter of generosity, I allowed the Dauphin and Gecko to fish together on the last day. I played golf at the Abaco Club, and embraced my inherent villainy.

It was an incredible adventure, and I was on the right side of history in my mind only because the duality of life makes us all villains, but we take hero shots, too. That is the secret. The last day while playing golf with one of the Blackfly owners, he told a story that resonated with me. After telling me about his spiritual journey to become a joint owner of the lodge, he explained that one day a car washer boy came up to him and said, “God told me to ask you if you know the difference between a level and a dimension?” He said that he did not, and the boy said, “You can’t go to another dimension till you let go of the weight in your heart.” When I heard this I was ready to get home and see my father-in-law. He died hours after my return. It is my hope that he found a dimension called Grace-land.

vaughn cochran

vaughn cochran

By The Lost Dauphin of Mississippi

Photos by Gecko

By The Lost Dauphin of Mississippi

Photos by Gecko

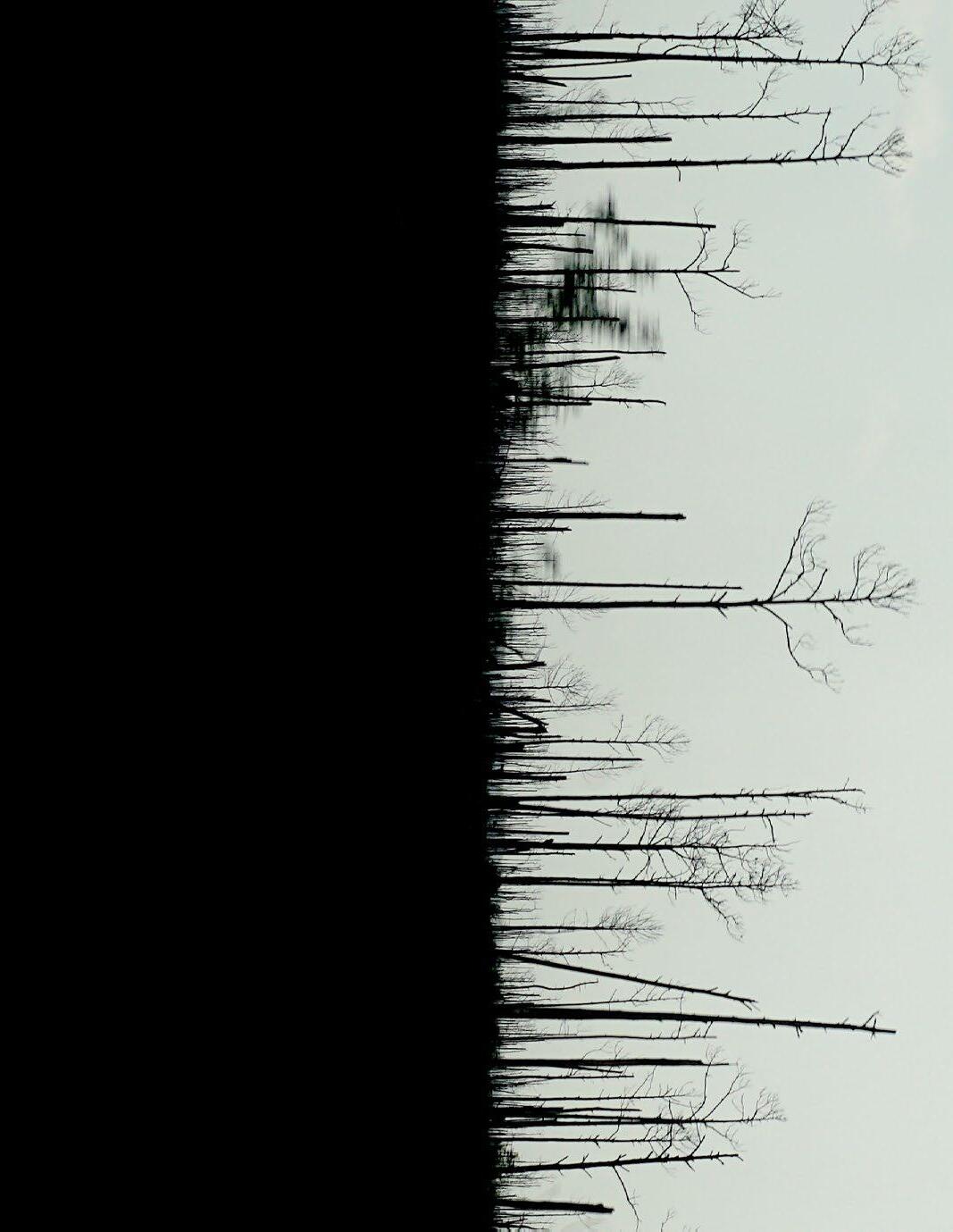

It was a slow day and the sun was beating through my car windshield when John called and said, “Maybe the worst day of my life can become the best day of yours.” After that the phone began breaking up. Staccato signals of constant information about a loose affiliation of millionaires and billionaires, an exclusive lodge, the dying of old men, non-refundable deposits. Once-in-alifetime trip, fit for a king. Bonefish, if I can just get down there. I’d been living like a boy in the bubble, hiding inside my house from floods, forest fires, and the sixth worst air in the United States. Maybe life itself. I had zero dollars in the bank, but that day found out the IRS was sending me exactly enough. My baboon heart screamed.

These are the days of miracles and wonder

This is the long distance call…

I catch the redeye out of San Francisco at 11:15pm to catch the 2:30pm to Abaco the next day. In the morning my traveling companions are ghosts and empty sockets, a planeload of exhausted walking dead. And in 24 more hours I’d be looking at a different kind of ghosts and empties, the shadows of mirror-sided bonefish and the empty mud streaks where they’d just been. But for now there’d been a mixup. The lodge doesn’t know I’m coming. I’m a plus one’s plus one. Lost in the communique.

Day one on the water, we’ve yet to see a bonefish when Kurt stops poling and says, “Three permit at 9 o’clock, 60 feet.” Between the clouds and waves I can’t see them. It’s my first time on a deck fly casting to saltwater. The wind is 17 knots in our face and I’m casting like it’s a trout stream, high and pointless, crumpling into the ocean like a dead paratrooper. Who am I to blow against the wind? Emasculated, I’ve already committed to a new cast thinking I’m short when Kurt tries to get out a “Let it sit.” It’s too late, the line rips slowly off the water, and lands as poorly as before. The permit I never see swim off. “He was on it. Always play it out, strip. Dem tree was lookin’.” The pole crunches again through sand.

I was having this discussion in a taxi heading downtown and the driver, Matthew says, “We got our own way of talking code around tourists. We don’t drive no square-tired cars round here, you know?” He’d seen me Rearranging my position in a notebook On this friend of mine who had a little bit of a breakdown, wading through the mud and muck of everyday life and emotionally riding around on square tires. I said, "Hey, you know, breakdowns come and breakdowns go, so What are you going to do about it? That's what I'd like to know?"

“Catch a permit,” he’d said. “Hell, to even just see one would make the trip.”

And just like that there she was, flaring massive and silver on the black diamond of a stingray’s back. I hadn’t seen the three I missed, or the one John’s fly rod tip flung at, but I will never unsee this one. Looking just like the Vaughn Cochran paintings at the Lodge, just as I’d imagined from McGuane’s The Longest Silence. A bigger rogue wave pulls her off the ray pointing her straight at us as through an aquarium wall. We see the exact moment she spots us, and… gone. John folds into his knees, both disappointed and thrilled for the three casts she engaged him. Seneca said all disappointment comes from expectation. This is a stoic’s game.

He’s a poor boy

Empty as a pocket

Empty as a pocket with nothing to lose

I spent the second day calling our new guide Patrick. He didn’t correct me until I tipped him. “Patrick’s my brother, I’m Derrick.” All day he’d wanted to go in early, for us to just agree that the wind was too much, and that fishing in the rain was a pointless proposition. But we’d struck out through the windy, clouded morning. When the sun came out, Gecko broke the hook off our only heavy shrimp on a fat bone, then I played one too aggressively, no longer super-thrilled to catch a bone, having seen a permit, my eyes peeled for the shadow of a ray. “You gonna mash it up, playing him hard,” Derrick says through his cigarette, and I do. After two long runs, it slips off the rusty hook Derrick let us use. Gecko sees a large triggerfish and casts at him eight times. The boy can cast, but the triggerfish don’t care. “You ain’t gonna land that,” Derrick says, “He ain’t eatin.”

I need a photo opportunity

I want a shot at redemption

Don’t want to end up a cartoon

In a cartoon graveyard

Bonedigger, bonedigger

In the last lagoon before takeout, Derrick watches a private jet flying in. Once, a rich man lost a permit to some mangroves and yelled at Derrick, “You’ve got to go get him!”

To which, in his gangster way, he replied. “I ain’t no fuckin’ diver.” The sun’s finally out, but so is the wind. “I can’t fight this wind.” Derrick says. “It’s too much.” We ask for 60 more feet of poling. He relents. We didn’t know his shoulder was killing him, and hadn't really acknowledged his gray hair until now.

Gecko yells, “Triggerfish! Triggerfish!” Thirty feet at 3 o’clock. I offer him the rod. He waves me off. The trigger hits the first cast then spits. Goes back home. I cast again 10 feet off. It broadsides the fly, and when I set, I hook it from the outside of its lip. “You don’t know how cool this is,” Gecko says. Then we see seven bones with their backs out of the water. Gecko takes up the rod.

This is the powerful pulsing of love in the vein

After the dream of falling and calling your name out

I hadn’t heard about hurricane Dorian, a category five with 185 mph winds that sat on Abaco for two days, trying to erase it from the earth. I was living in New Zealand, and during hurricane season I stay focused on wishing storms to go in any direction away from my family in Mississippi. Katrina was more than enough. Just like the Mississippi coast, you could read the storm’s power in absence of trees and crushed buildings, the human population shrunk from a once high of 80 thousand people, to 14 thousand today. Broken boats strewn from Marsh Harbor to Crossing of the Rocks, the jagged skyline of splintered pines. And the all-important mangroves, the incubators and nurseries of the Atlantic pulled from their clusters, sent to establish in new shallows, regeneration through violence.

“Can you tell an impact on the bonefish population?” I asked. Bones breed in the deep water, letting the currents disperse their larvae.

“Oh Yeah,” Kurt says. “Mainly up north. Population was down. It hurt ‘em. Everything, lobsters, crab, everything use it to live in. To bones, it’s the restaurant.”

I go out with Clint to deep-line snapper for our evening meal. He’s a conchy with roots on the islands going back to the 1600s. He stays on the hustle. “How’d you get into this?” I ask.

“I took a hard left turn 15 years ago. Even my parents could tell I was miserable. So, I divorced my wife, who was a nice lady.” Never mistake comfort for happiness. Now the one-time preacher and cigar-importer-turnedguide runs the most exclusive lodge in Abaco. But the burden of other people’s happiness is relentless work, and there’s a tiredness in his eyes behind the shine. He’s training up a new manager to help transition to his next phase. He once said bonefish were from the Lord, and permit...the Devil. I'm tempted to believe him.

He says, “Well this will eat up a year of my life And then there’s all that weight to be lost…

At night the eight in our party eat together, get a little conversation, drink a little red wine. Tell stories of hooliganry unvarnished and unbecoming. Very little about fish is spoken that isn’t the crispy snapper on Hoppin John. Everything Chef Sam brings us is better than the last thing she brought us, every spoonful a benediction. I said, "Good gracious can this be my luck? / If that’s my prayer book / Lord, let us pray.”

They call it family here and her “Big Mama,” but she is Chef Sam and every night she throws down for the uber-wealthy, stars of stage and screen, a metric fuckton of pro golfers and occasional stray, broke assholes like ourselves. Gecko has four dollars, I, my last $300 on me for tips. John is the living embodiment of a Faulknerian generational freefall, Snopes-cycling the hell on out. But we’ve somehow been received at this table.

They‘ve flown Chef Sam around the world to shadow and dine with famous chefs. If she doesn’t like what they make, she lets them know. Originally a security guard, she started cooking when her husband began going blind, first the breakfast shift and then asking for a shot at dinners when the main chef moved on. Clint, a fine chef himself, hired her and worked with her on the kinds of four-course meals they expected. She more than met the challenge.

“You love Clint?” I ask.

“Like a father,” she says.

Well, the sun gets bloody And the sun goes down

I walk out to a gorgeous sunrise, feeling the broken heart of the last day of summer camp. Kurt is over in a field beside the lodge casting with power and grace as Matthew begins loading bags into the taxi. He’d like to leave five minutes earlier than scheduled, but the Long Wallets need an extra 30. He calls us the Short Wallets, and knows the short wallets would stay if we could. We’ll leave and a new crop of folks with high expectations will arrive. And though we’ll remember these folks and the experience they gave us for the rest of our lives, our names and faces are already ghosts in their minds.

“There’s no doubt about it It was the myth of fingerprints I’ve seen them all and, man, They’re all the same”

THE SKY ABOVE THE SEA BELOW

(29" + 27" + 26" = 82")

I’ve thought about time a lot in recent years, maybe even obsessed about it to unhealthy levels. Perhaps it’s a function of aging, or maybe every angler is in a similar, sorry state of time obsession. My SCOF colleagues remind me daily that I am the elder statesman of the group, so perhaps I’m getting paranoid. I think part of the root of my time obsession is that my actual time on the water, fly rod in hand, is limited. No matter what the job title, we only have so much time, actual real time, in pursuit of the fish we target. Much of my life is spent away from the water, my stored fly rods scattered in my guest room, fly boxes awaiting their promised re-organizing and de-salting. Like everyone else, I have other pressing matters to attend to: job, family, friends, exercise, bills, eating, drinking, special lady friend. All critically important endeavors on some level. My aged and aging high school friends on social media may think I’m always fishing (or so they claim) based on my photos, but sadly, my angling schedule, like most everyone else, must fit into specific blocks of time between other life events. As much as I want to be a trout or permit bum, my angling experiences are limited like 99.9% of us. I’m more of a permit vacationer, writer, and researcher than a permit bum.

I do have a career that provides more access to water than probably most of the public. For example, I take university students to Belize every May for a field course where our field sites adjoin a couple of bonefish flats. But even though I can literally see tailing fish, I have actual duties that limit opportunities to pay those fish proper attention. I throw some flies at dawn and feel quite happy if I

can start my day with a single fish, but soon enough my teaching duties begin, and the fish are left to the conch chunking tourists from nearby lodges. Besides teaching, much of my research mapping mangroves and sea grass for the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust obviously puts me near water and fish. But I’m not necessarily fishing when I’m doing actual fieldwork and collecting data. When I can truly focus on fish, I am on the proverbial clock like everyone else.

At the beginning of an organized, booked fishing trip, it feels as though I have all the time in the world. Five or seven days on a bow, roughly eight hours a day seems like plenty of time to live out my angling dreams of glory. But as we all know, time passes far too quickly on the bow, and with that time, pressure builds.

On day one, I cut myself some slack if I make a shit cast and miss a fish. I tell myself that surely there will be other permit once my fish vision improves and I get my casting act together. Even day two feels carefree. I tell myself, “You’ve caught permit in the past, no worries! Enjoy the scenery.” But by day three, the pressure increases, and I can feel the clock ticking. It never helps if my flats are empty, but the guide regales me with stories of past, huge schools of permit that a previous client casted to for hours at a time without them spooking. I mumble to myself something about hatred for that lucky SOB.

The pressure is worse if the conditions degenerate. Cloud cover, gale winds, rain, all haunt me. Every shot, every possible fish, every shadow, tightens my chest. My chest is tightening just writing these words. And of course “tight fishing” usually doesn’t result

in successful fishing. Rushed, sloppy loops in tropical winds rarely deliver a Bauer’s crab within striking distance of anything.

I often resort to prayer when the pressure builds. I’ve prayed more on the bow of a boat than any other time in my life combined. I’ll recite the Hail Mary, Buddhist chants, anything to any deity. Blasphemous perhaps, but I try to cover my bases with all the great faiths. The last day is the worst if it’s been a slow week. I can feel the guide looking at his watch. I want to shout out, “Give me one more flat, one more shot!” Again, the pressure is obviously much worse if it’s been a slow week. If I’ve caught a permit or tarpon, I’m satiated, I’ve lived my dream. I’m ready (sort of) to go home. If not, the guide’s final command of “reel it in” wrenches my heart.

...where will your Towee take you?

As a kid, when I was asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” I always heard the same cliché answers from my peers: a fireman, a policeman, a politician. I’ll never forget the time I looked my teacher in the eye and gave her an answer I am sure she thought was out of left field. “I wanna work on a whaling ship!” And for my honesty, I was granted a conference between myself, my parents, and a teacher who thought I would one day be on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted.

The truth is, I always felt a connection to the men who manned those small boats, breaking their backs and breathing in equal parts air and salty foam as they tried to get a harpooner at the prow of their skiff close to a beast that dwarfed anything those bastards had ever seen. At a young age, I had seen the made for TV version of Moby-Dick, and read the book when I was in seventh grade. And it wasn’t Ishmael I felt a bond with; it was the anger-bound, fiery, heathen captain of the Peiquod, Ahab. Perhaps it was that youthful angst and drive I had for my few goals, or the hatred I had for societal norms, but I always admired a man who looked death in the eye, and said, “For hate’s sake, I spit my last

breath at thee!”

And I honestly think us saltwater fly fisherman are the memetic descendents of those brave souls who gave the world light, and gave us the first true “fish stories.”

Think about it. The encounters always start the same. Perhaps there is a lull in the air, where full sails wouldn’t even be able to bring a ship any speed. Or maybe there is a chop in the water, with waves so close together that anglers must shout above the din of white caps lapping at the hull of their small boat. Just like those ancient mariners, our boats are tiny, compared to the big ships of our time. Maybe the captain isn’t at the helm of something like the Essex, our skiffs may as well be the same. It is our base of operations from which our adventures go. From the crow’s nest of our poling platforms or coolers, our eyes scour oceans for our hobby’s version of the spouts of breathing whales: tails, flashes, wakes, daisy chains.

On the bow of the vessel is a man with a modern day harpoon; a nine-foot long weapon of bass destruction, with some kind of sharpened metal meant to pierce flesh and scale. Maybe it looks like a shrimp, or a crab, or some abomination against God that somehow gets the job done. Their eyes work with the captain’s, and as the push pole gives the skiff power, a call rings out, akin to the old bell that a look out would ring.

Instead of launching rowboats off davits with the cries of a bloodlusting crew, the angler and captain share clock directions, distances, descriptions— the three D’s that allow our modern harpooner the shot they need.

Whales are not the intended target. No, what this team is after is something way smaller, but just as beautiful. They want to chase the copper sides of the redfish. They are after the reel screaming runs of the bonefish. Some crave the blast beat drum of tarpon jumping repeatedly. And true masochists go after the ever scrutinous and costly permit. Those are our white whales, our holy grails.

Like the oarmen in those ancient skiffs, the captain poles the boat within range. Not too close as to spook the quarry and make them rush away in splashes of foam and black mud, but not so far that the harpooner has to give himself a hernia casting his weighted line back and forth till the fly and leader land where they need to.

While not as explosive as the red sprays of steel meeting blubber, the connection the angler makes with the fish is just as pulse-pounding. It could be the gaping maw of a tarpon inhaling a fly the size of your pinky, or a redfish almost leaping unbelievably out of the water to eat a popper on top, but either way, it will bring the most guttural growls and yells from an excited angler and captain. The reel screams, as line runs out like the extra rope following a fleeing whale as the game tries to fight for survival. And much like in those old voyages, the fly line can wrap around anything. This could include running

lights, trolling motors, arms, and legs. But at least in these new times, the chances of the angler being pulled under and drowning is nil: 10-lb tippet or 20-lb leader usually breaks a lot easier than one-inch thick rope.

Then there is the “ride.” Back in the day, it was called the Nantucket Sleigh Ride. Kayakers love to call it the Cajun Sleigh Ride in this day in age, but it still happens on a skiff. The fish pulls in one way, and the boat will follow, either pulled by the game, or propelled by the captain. The bigger the fish, the more control the captain will need over the vessel, and this could mean using a push pole to get around stumps and trees, or even using the motor to gain ground and line on a tarpon rushing to the deepwater of the ocean.

Finally, the game tires. The whales would run out of oxygen and blood,

being unable to get away from the men chasing it with lances and meat hooks. Whalers bring the whale boat side, much as we fly fishermen get our fish to hand. Unlike the old days, we don’t kill these beautiful creatures. A few pictures are taken. A tag may be placed. Maybe a fin gets clipped for science. And with a little revival, the fish swims away. The old whalers would have the hard labor of bringing the carcass to the mothership, hanging it off the sides, and butchering it to harvest the blubber, oil, and teeth if they got a sperm whale.

And then, once these deeds are done, we go off and do it again.

I’m sure you all know the definition of insanity: doing the same thing time and time again and expecting different results. Maybe we, who chase fish, are a different insane: doing the same thing time and time again but expecting the

same result. I wonder if those old whalers felt they were insane, spending months aboard an old wooden ship, rowing after beasts that could destroy their bodies in one motion, killing them, and doing the dirty deed of dressing them out.

Maybe it was a certain metal album that made me realize these parallels between our whale killing ancestors and us modern day saltwater anglers. It was “The Call of the Wretched Sea” by Ahab. Listening to it, picturing those souls chasing those plankton eating giants while poling my own skiff, I realize how alike we truly are. I heard the phrase once “All harpooners are bastards.” If this is true, call me a bastard for sure, and tattoo it on my arm, for I will always chase my white whale, the fish of the flats.

By Craig Haney

Cover Photo by Thomas Schenider

By Craig Haney

Cover Photo by Thomas Schenider

With a great deal of humility, I confess I am well known among my friends for my prodigious “luck” (not necessarily good luck) while fishing, and also while pursuing less important things. This luck of mine has followed me throughout life for quite some time, and I figured it was with me when I boarded the plane for Bozeman.

My good friend Billy had moved to Bozeman a couple of years earlier and would be my host for the week. A great addition would be my buddy Sam, who had recently moved to Gillette, Wyo., and was coming with his new drift boat.

Once Sam arrived at Billy’s, we wasted no time discussing the myriad of fishing opportunities and decided to try the Madison River the next day. Billy had checked with his buddies, Henry and Doug, and a couple of fly shops earlier that day and felt like the Madison River was a safe bet. The weather forecast was favorable with a high of 73 degrees, cloudy, and little wind. We didn’t realize it then, but the fishing gods were lurking in the shadows waiting to open a can of “Haney Luck” on our trip.

We left Billy’s place early the next day headed for Ennis and Madison River Fishing Company to check again on conditions, and to spend some tourist dollars on flies and other needful things. After buying maybe a half-pound of streamers, articulated and otherwise, we headed to the truck. Suddenly, as if Moses had appeared with a message for me on a stone tablet, I realized I had left my prescription sunglasses on the dresser at Billy’s back in Bozeman. The can had opened ever so slightly and a wisp of my luck had eased out.

MRFC didn’t sell fitover sunglasses, so we went down the street to the Orvis dealer where I found a pair and spent an

additional 50 dollars, which helped the local economy but hurt mine. Getting in the truck, we headed upriver to the Windy Point boat ramp—the day bursting with promise and high expectations.

It was 10 a.m. when we pulled into the parking lot at Windy Point and parked the truck and boat. Quickly assembling our rods and reels, we tied on flies and loaded our gear into the boat and pushed off into the Madison. If I had not been so ready and excited to fish, I might have noticed the wind had picked up and that there were a few dark clouds looming in the distance. Would the name “Windy Point” become a bad omen of my luck still to come? Was the can of Haney Luck in the boat? These questions were on my mind as we started the trip.

Sam is young, strong, and adept at the boat’s oars and soon we were casting streamers to the banks of the Madison. An hour passed without a strike for either Billy or me. Changing streamer patterns did not help and nothing else in our fly boxes enticed the trout either. The wind had picked up considerably and grayish clouds were blocking the sun. As the temperature had not risen since we started on the river, we decided to put on our wading jackets to block the wind and add a little warmth. The wind continued to gain velocity, and the dark Montana clouds grew closer as we fished downstream. I started to wonder if my can of luck had been blown over by the gusting winds and was now leaking. It did not take long for the answer as cold rain started pelting us, stinging our faces and hands, and chilling our bodies. Sam hopefully offered that maybe the wind would blow the rain away and things would settle down, but he did not sound convincing as he struggled with the oars

to keep the boat on track. We soon passed a guide who had pulled to shore with his clients to wait out the hard rain. The body language of the wife in the back of the boat indicated that she was mad as heck and would keep her husband up half the night trying to explain why they did not go to the Bahamas like she had wanted for vacation.

As we traveled downriver, I started shaking as had Billy and it was clear the can of luck had emptied out in the boat and was affecting us. Sam hurriedly scanned the river bank for a place to beach the boat. Before Sam found a place to pull over, Billy and I started shaking uncontrollably due to the cold, driving rain and endless wind. Suddenly, the boat turned right and the sound of the gravel bank scraping the hull was a welcome sound. Quickly finding a hoodie and fleece vest for us, Sam handed us a large jar of salsa and the largest bag of tortilla chips I had ever seen. The two of us were warming up as Sam set his small gas grill on the shore, fired it up and put the sliced elk tenderloin complete with his “magic seasoning” on to cook.

We devoured the salsa and chips as if we had not eaten for days. I never realized how good salsa and chips could taste. Seriously, they were the best I had ever eaten! The salsa and chips soon started warming us from the inside out. Before long, my shivering slowed as visions of grilled elk started filling my head. Sam soon announced the elk loin was ready and handed Billy and me a piece hot off the grill. Like wolves on a fresh kill, we made fast work of the tenderloin, not stopping for bread or condiments.

The rain soon slowed then quit, but the wind was still coming in strong gusts. After filling up on salsa, chips, and elk, we loaded back up and headed downstream

with Sam furiously fighting the wind and current.

Billy and I finally put our rods up in frustration as we continued down the Madison. It was disappointing to quit fishing, but the fish were clearly turned off and the wind made it tough to place your fly anywhere close to where you wanted. The rain finally stopped, although the dark, mean-looking clouds still threatened.

About a half-mile from the McAtee Bridge takeout, a huge rock appeared directly in front of the boat like the iceberg in front of the Titanic. I called out to Sam to make sure he had seen it looming menacingly ahead. He yelled back, “I got it!” and I heard a loud grunt. I was not convinced he had it, but the boat narrowly missed it, moving magically to the right of the rock at the last moment avoiding disaster.

Turning to look at Sam, his big grin told the whole story. The magic was in his strong back and arms. Billy called from the back of the boat, “If I had been at the oars, we would have been in serious trouble!” Billy was probably right as Sam’s extra six inches in height and 100 pounds made the difference, not to forget Sam being 30 years younger than either of us.

Back on track, the ominous dark clouds and strong gusting wind had been replaced with the warming sun as the takeout came into view down river. Somehow, bouncing around in the boat the top evidently secured itself on the can of Haney Luck just before we centered the rock as the trip neared the take-out and dry clothes.

I’ve often heard it said, “If it wasn’t for bad luck, I’d have no luck at all.” That Friday on the Madison River, maybe no Haney Luck would have worked better.

by devin davenport

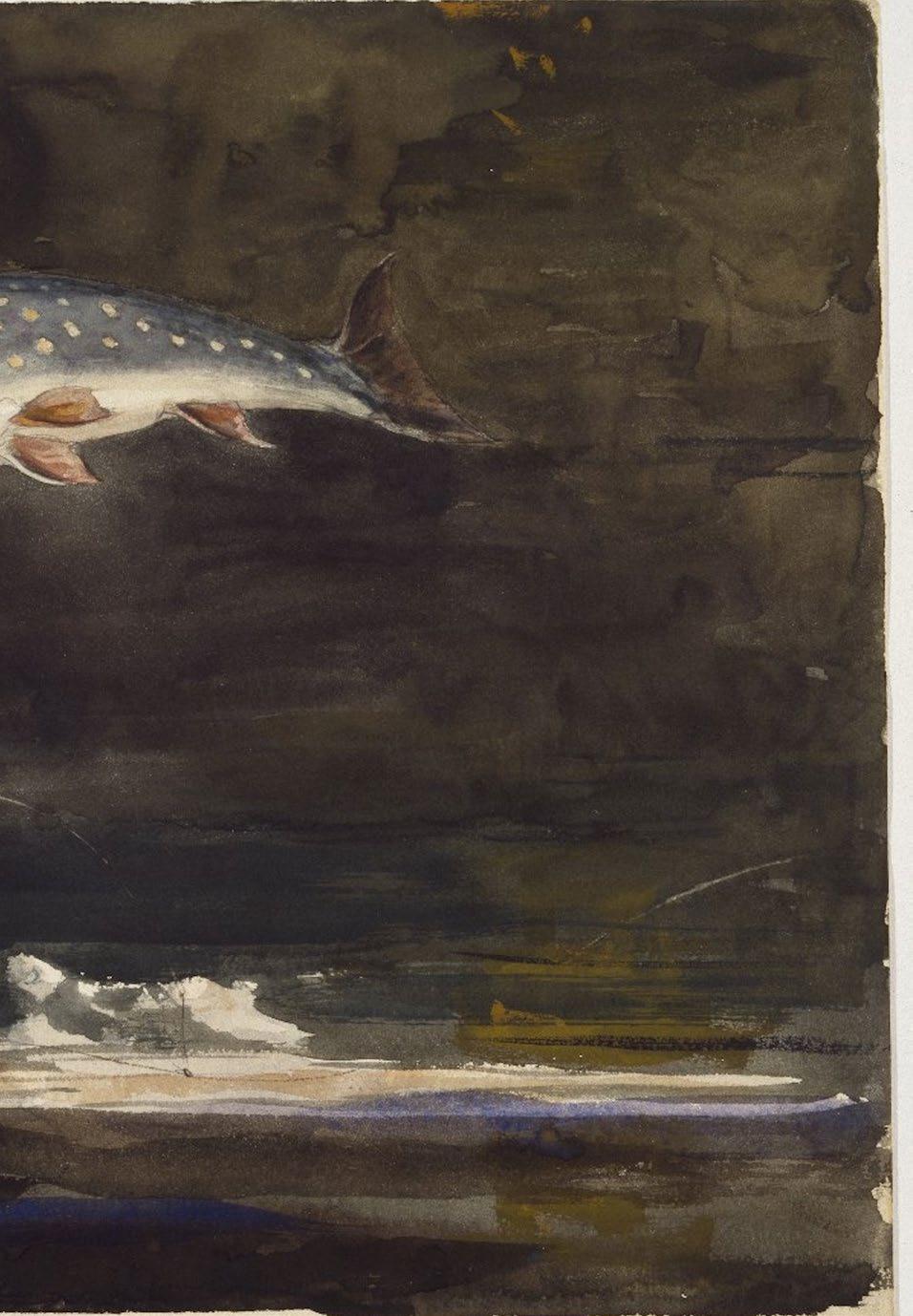

jumping trout: winslow homer 1889

The brook trout is among the most iconic species for anglers in eastern North America. This lovely fish registers as a powerful symbol because of its beauty, imagery in art and literature, and role as an indicator species of the overall health of an environment.

My use of the word “lovely” gives away the reason I hold this small fish in such high regard. There isn't a more striking fish in the East, at least one that’s targeted on a fly. The sides of the brook trout are sprinkled with dots and dashes of red, orange, yellow, and the occasional blue. Its belly—especially in the autumn— turns bright orange, while its upper back is dark green or even black, providing stunning contrasts. The first time I held a brook trout, I thought that an artist had painted all the colors of a fall Appalachian forest on this one small, living palette.

Yet the camouflaged back of this fish makes it almost invisible in a stream. Not until we pull a brookie from the depths of its cool, dark pool can we see and truly appreciate these small masterpieces. Sometimes when I sit near a stream, I almost feel sorry for the hikers who quickly walk by, seemingly oblivious to the beauty of the creatures hiding among the cobbles on the stream's floor. The hikers' lack of attention in turn makes me think more deeply about what I might be missing in nature when I am distracted.

For centuries, the brook trout has inspired artists and writer alike. Its image has graced the canvases of America's best sporting artists, beginning in the 19th century with Winslow Homer's paintings of leaping brook trout. His celebrated watercolor of 1892, A Brook Trout, is one of the most recognizable images of fish in American art. It both depicts the species with accuracy and places the fish in an almost unimaginable aerial pose.

Homer's focus on the brook trout should not be particularly surprising given that, during the 19th century, it was the only salmonid in many eastern

rivers, a prominent setting for his art. The brook trout remains a popular subject today among piscatorial artists like James Prosek, whose vivid watercolors of small brook trout are set among the streams of his native Connecticut; Joseph Tomelleri, whose scientifically detailed work has appeared in more than a thousand publications and whose client list (ranging from Bass Pro to Zebco) makes him perhaps the best-known fish illustrator today; Bob White, whose fish and fishing watercolors always inspire me to start planning my next fishing trip; and Mary Beth Meeks, whose block prints portray a slightly different but equally beautiful rendition of the fish. These individuals are not only talented artists, but also avid anglers who effectively depict the essence of fish and their landscapes. The allure of brook trout and the landscapes where they are found are also reflected in an abundance of literature. Contemporary authors such as James Babb, Chris Camuto, John Gierach, Nick Lyons, Craig Nova, and W. D. Wetherell have written in great detail about the intersection of life and angling for brook trout. Their work has led me to contemplate the role of the brook trout in my own life. Other works focus more on biology and natural history, with Nick Karas's book Brook Trout serving as the standard-bearer for any and everything about brook trout. Before the mid-20th century, the connection between literature and brookies specifically is harder to trace, but trout in general and fly fishing in particular provided fertile waters for a rich body of work. The great naturalist John Burroughs (notably in his essay "Speckled

Trout”) and the writers Theodore Gordon, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Maclean, and Henry David Thoreau all fished in brookie waters.

Beyond the creative inspiration provided by the brook trout is that its presence tells us a great deal about the health of the larger environment. The brook trout is an indicator species for streams, lakes, and watersheds. Because they are most plentiful in largely unspoiled conditions, their association with clean intact environments is another reason the brookie has developed a dedicated following among fly anglers. When I have a brook trout in my hand, I know the water in which I am standing is nearly pristine.

Writer Chris Camuto notes in A Fly Fisherman's Blue Ridge, "Wild trout are a sign the land is doing well." And according to Gary Berti, a former coordinator of the Trout Unlimited Eastern Brook Trout Campaign, "brook trout are the canary in the coal mine when it comes to water quality. . . Declining brook trout populations can provide an early warning that the health of an entire stream, lake, or river is at risk."

The brook trout is also the most widespread species of trout, often described as the only native member of the Salmonidae family found in the eastern United States. This is technically incorrect, because the closely related Arctic char lives in a handful of isolated ponds in northern Maine, Atlantic salmon continue to swim in the waters of several rivers and lakes in Maine and many more in eastern Canada, and lake trout are also found in the deep lakes of New England. The brook trout, however, is the only native salmonid found south of New England, in highland areas such as the Allegheny and Blue Ridge Mountains.

The brook trout's native range roughly spans the spine of the Appalachian Mountains, from northern Georgia to northern Labrador and west to the Great Lakes and Hudson Bay regions. Within this vast geography exists such distinct populations as

"coaster" brook trout in the Great Lakes; "salter," or sea-run, brook trout along the coast of New England; southern and northern strains in the Appalachian Mountains; and unique strains in some of Maine's ponds.

Habitat scale or opportunities correspond with the scale or size of the fish. Even so, it's strange that the small but mature six-inch brook trout I caught in foot-deep clear streams in South Carolina are the same species as the giant 20-incher I caught in the deep-black rivers in Labrador. Geography matters.

Because of stocking efforts during the 19th and 20th centuries, char and trout today are found outside their natural range and overlap with introduced species such as brown and rainbow trout. The brook trout is now widespread in western North America and has become an invasive pest, displacing many native cutthroat trout species. So while conservationists in the East work to protect brookies, those in the West seek to remove them. Their presence and its ramifications became clear to me while fishing in Montana's Lee Metcalf Wilderness Area, far outside the brook trout's natural range. For every native cutthroat we caught, I probably landed 10 brook trout. Although that experience remains special given the sheer number of fish I caught, the memory is somewhat tempered by the knowledge that brook trout don't belong in Big Sky country. The experience would have been more pure had I caught only native cutthroats. The environment in which the brook trout is found is also part of its past and present appeal. To fish for brook trout is often to fish in the last remote and rugged landscapes in the East, "fishscapes" not polluted by the stocking trucks that dump nonnative brown and rainbow trout in most of the East's accessible cold waterways. Part of fishing’s allure in general is the landscape, whether the junglelike mangrove swamps of the tropics or the cold, boulder-laden streams flowing from mountains. The brook trout's home environment—streams in the old hemlock-covered Appalachian Mountains and

silent ponds in northern New England—are some of the most beautiful landscapes in the eastern United States. One inviting feature of these waters is that they do not suffer the same levels of fishing pressure as lowerelevation streams that are more accessible. It’s common to spend a day completely alone while hiking up a brookie stream, even though you may be only a few hours from urban life along the east coast. During most trips to fish for brook trout, my only companions are brightly colored salamanders, birds in the treetops, and an occasional black bear. These streams are not home to large, blandly colored, hatchery-reared fish. Anglers who hike up to cold trickles appreciate the intangibles that nature has to offer: great views from the tops of mountains, the physical challenge of getting to rugged streams, and the chance to catch colorful native fish. When brookies strike at the end of my invisible leader line, the mountain has bestowed upon me a living gift. Today, brook trout in the eastern United States receive more conservation attention than they ever have, from growing numbers of local, state, and federal conservation and restoration projects. The simple yet understandable desire to catch big fish does not drive this interest. Brookies, in most of their range, are not and never will be big fish. I feel a sense of accomplishment when I catch an eight-inch fish in a headwater stream. The love of native fish and their landscapes is the motivation that largely drives the effort to improve and protect the brook trout's habitat. To me, this is a healthier motivation than managing a species and ecosystem solely for producing trophies.

I am not naive about our past or current disruptions to landscapes of native trout. In almost all areas where brook trout are

found, the axe and plow—if not the front-end loader—were close at hand at some point in the settlement of North America during the past three centuries, and nonnative trout have been stocked in every state. Pristine forested landscapes are rare in eastern North America today, including the South, except for a handful of old-growth forests scattered throughout the remote mountains. Nineteenth-century photos of the Green or Shenandoah Mountains show fields growing stumps and stone walls, not the mature forests we associate with these areas today. But wilderness can also be thought of in terms of personal meaning and experience and not just in relation to miles from roadways or thousand-year-old forests.

When I hike and fish a mountain stream, I sometimes like to imagine that its true headwater is in some remote wilderness well beyond my reach rather than my stopping point at the moment. Even if the true headwaters are within reach, I often stop fishing before I reach them so that the stream retains some secrecy in my mind. Wilderness is a place where native species still dominate, where one can find peace, meaning, and some mystery in the natural landscape. These places are the mountaintops, gorges, and remote ponds where colorful brook trout still hover in cool, dark waters. If wild and native brook trout are still out there, wilderness and clean pure water abide. As I look back with a present-day appreciation of how much that first experience of catching brook trout affected me, some lines from Moby-Dick come to mind: "Take almost any path you please, and ten to one it carries you down in a dale, and leaves you there by a pool in the stream. There is magic in it." Indeed, I still find magic in those brookie pools and streams.

Photo Essay by Dave Fason

Photo Essay by Dave Fason

Captain Will Paul

Captain Will Paul

Fully outfitted fly shop guided fishing boat supplies good hangs

It wasn’t long before Miles had us speeding full throttle through the curves of what seemed like a maze of seagrass. Since this was our first time with Miles, he explained we wouldn’t be going too far out as he wanted to assess angling skills by going for smaller, “training wheels-size” fish before we set sights on the big ones. Torie took the stand first. Moving silently near grassy edges, he spotted tails long before we

“Two o’clock, maybe 25 feet.” She cast delicately into the brackish water. “Recast, a bit further. Perfect.

Her line tightened, she set the hook, setting in motion a nice run by the red and the sound of the reel’s drag. She made it look easy. Now came my turn. “Ten o’clock. Get it out there.”

Photos by Patrick Tragesser

Photos by Patrick Tragesser

The first time I saw a wild turkey, I felt I’d seen an alien. I was just a child.

So when I came face to face with the gobbler, I was closer than any non-hunter should ever be to this bird. Scary ugly. Ugly. His protean red, white, and blue head was wrinkled with hairs and iridescent feathers that never quite grew in. Warts and bumps shaping its eyes. He looked intensely at me in my bright green shirt. Frozen still, ice cream dripped down my tiny hands, and then like a real life version of the cartoon roadrunner, it made its “beep-beep,” a sudden sound of a screeching gobble… GOB-Gob-GOBBLE. Instantly the empty woods filled the silent terrain with its crowded sounds, so that all that then mattered was the ole tom’s pitchy, shredded cry. In a flash, it took off through the forest following the hens beyond sight.

The next time I saw wild turkeys, I was riding with a girlfriend on my four-wheeler to the top of the satellite tower that nests atop the highest point in the Dunaway chain. This forested peak anchors the backside of the Gadsden Country Club. Though the gaggle of birds never saw me that day, they flew majestically in a lumbering fashion out and down towards an opening in the dense canopy. Fans pumping up and down, deftly they navigate the old growth hardwoods. With their gnarled and spurred feet tucked under their massive bronze-black bodies, they coasted to a safer field down below.

Like the Appalachians themselves, I have learned, the history of the turkey species is rich in these hills. Local Cherokee Americans unquestionably made them their quarry. After the indigenous were removed, the turkey were nearly wiped out due to unethical hunting practices and our human sprawl. But we began trying to conserve the bird by preserving its habitat and capturing

turkey in nets to relocate them. I have always been a slow learner. I never studied wild game at Auburn, and despite the conservation class my father insisted I take, I had little grasp on why game are where they are. They just were. Unlike the very mountain whose stillness suggests eternity, these ugly birds are today its meandering and soulful inhabitants, ricocheting through the hills and hollows like pinballs put into play by an inadvertent contract worker or, worse still, a thoughtless adolescent on his four-wheeler. From the peak of Hensley where turkeys roost today, one can easily see the mighty Coosa River winding and “essing” through a series of bends, the closest being Whorton’s Bend.

In the 19th century, emigrants from Europe introduced an Asian species of fish known today as the common carp. I have always loved to fly fish, but, like turkey hunting, I picked up fishing for this species very slowly. It took me about five years of being devoted to the sport to achieve a level of skill that allowed me to consistently find these golden ghosts. Fishing on the Gadsden flats, I spent hours among relict roadways now submerged by the damned waters of the Coosa waterway. Much as finding turkey a happy accident, I would never have realized that carp populated these backwaters if I had not been surveying the James Martin Bird Sanctuary for a local engineer. My end-ofhigh-school summer employment intended to be a dose of life’s practical side. Instead, I remember vividly the carps’ allure; largebodied fish gracefully pushing and sliding contrails of escaping muck clouds. It was like the turkey I had witnessed with sticky ice cream hands. These relocated creatures constitute our impressions of the

by Alan Broyhill

by Alan Broyhill

wild, but are actually living accretions of man’s preservation of food source and his ancient agricultural regime. Modeled today from the geological remnants of nearby mountain pinnacles, the carp are happy in the muck of former ag-rows and terraces— timelessly ancient erosion.

I bought a boat that moves in very skinny waters to guide others in catching their first carp on a fly. Though this entrepreneurial dream is not yet financially rewarded, I do still believe in the act of stalking carp by studying their movements, by watching them tail in the mountain mud, and by pushing the boat towards the discolored water irregularities. I am more patient when it comes to searching for the wily and keen-sighted birds in the spring. When I see their tails rise from the placid water’s surface, I move just as if I had yelped a gobbler into revealing his secret spot on top of Henley Mountain.

If ol’ Tom gobbles but refuses to join my decoy party for his ultimate dirt nap, then I am forced to move up on this regal strutting monster. But for the Ugly, his one-and-a-half-inch spurs are his only protection. It is the very same tactic for moving up on a content carp. If it refuses to move or work itself towards me, then slowly and stealthily as possible I move on that prey to get my client close enough to cast his 40 feet of line onto the carp’s dinner plate. For turkey we yelp, cut, cluck, and purr to communicate our love and respect for the Tom in the hen’s language of come hither. For carp we strip it, twitch it, move it, and let it sit.

Sex and food are the tools of communication in these outdoor endeavors. With each, we as sportsmen build upon our mistakes. The mountain on the horizon can be seen hanging forebodingly over the commercial lights of barbeque and car

dealership. Here though, the muck clouds tell us, the anglers, where to find the fish to whom we sight cast. The full-throated thunderous gobble is how we know the mountain is not dead, as the muck would have you believe. Rather the call of this wild turkey lets us know that we are blessed with a living wild relic in a town full of contradictory southern charm.

The house is dark for 11am on a June Tuesday. Already too damn warm. Phone at 18 percent. Too many missed calls. Too long ago to reply now. I roll over, run my hand through thinning and days-greasy hair. Dry mouth. Breath as short as a tippet after a long afternoon. Coffee? No. Hair of the dog. I need to move. Need to get outside.

Sulphurs will be rising. Even with a hatch, the fish are as stubborn as lawyers and the soon-to-be ex. At least trout don’t charge by the hour. The storm clouds are going to pop off as violently as she did when she finally had enough.

Where is that beer?

Tires whine as the truck rolls down the road. I need to eat if I’m going to make it today. Becky is behind the counter, always with a glimmer in her eye, teasing

a fun roll in the hay. She knows just how I like my ham on rye and she isn’t hard on the eyes either.

“Here you go, hon.” Her accent and smile ooze like honey.

The pull off is empty. Leave the waders, take the light tippet. Two beers in the cargo pockets. Flies pinned to the mesh back of the hat.

This valley is tucked away from worldclass trout water where brown trout are wiser with each whip of Buster’s line. But this feeder spring creek that eventually feeds into it is a haven. Full of fish and a respite from the fires of home.

On the almost mile-long trail walk, my sweat smells vaguely of rum. Out of breath again. Need to get back in shape.

The air is still, as if listening to the gurgle of the stream talking as it flows past.

The cool of the creek is a baptism. Washing away the sins of the past. Reborn a trout bum.

The best part is not here, but what’s at the cut bank. What haunts it. Gives you cold sweats just thinking about it.

Time for a beer and reading of waters.

Eager grabs and releases with younger fish help knock off the rust before moving upstream. Limit the false casts. Keep it short. Work what’s in front. Keep moving on.

Time for that second beer. The smaller fish are not what I’m after but I need to dry the fly while enjoying the last of the hops.

Drying the fly and dab of Gink ensures the buoyancy as if it were a real sulphur falling to the water after doing his lifely obligation.

The hatch and the air grow heavier. I cast, all muscle memory, primed by sweat and beer.

A submarine surfaces from the dark below. Red iridescence of the adipose

like a spot light, the slow switch in his tail. Inspects the fly an inch underneath and follows it slowly backwards, dropping out of sight again. Wait, try again. Recast a little further upstream into the swirl of a small eddy.

Slurp.

Arm raised, setting the hook and feeling the solid jaw all in one smooth motion. Working downstream to the clear. The drag sings before his acrobatics.

Feeling that he might be done, he moves to the middle of the stream. Strikes his paddle twice, diving down to the old stump, wrapping the line.

He’s gone with a clap of thunder. No sense tying on another fly. Two old warriors that will be limping home.

The wind picks up, ushering me back to the truck as the heavens open. There is no sting of defeat any longer. No forgiveness either. Only the acknowledgment of each other’s struggle for survival.

photo: Craig Godwin

photo: Craig Godwin

A Photo Essay by Alan Broyhill

A Photo Essay by Alan Broyhill

everglades bear- March 2023, Alan Broyhill

Salty. And Sweet.

What perfect saltwater fly rod dreams are made of.

Scott Fly Rod Company

Handcrafted in Montrose, Colorado

Although many conservation groups deserve headliner status in the Corner, the first group profile (and guest essay) is Bonefish and Tarpon Trust (BTT). I chose BTT to begin this series because I’ve worked with them for many years on sport fish habitat mapping in the larger Caribbean, so I’m more familiar with their work than most any other sporting conservation group. I’m also a flats angler so their mission is also near and dear to my angling heart. Founded in 1997 by a small group of anglers in the Keys concerned with declining bonefish numbers, BTT’s scope has grown to include a research agenda whose geography extends throughout the Caribbean and Gulf, the publication of a fine magazine, and a science symposium held every three years. If you haven’t attended the symposium, you should. It’s the perfect combination of cutting edge scientific information on flats species and habitat, but also includes gear professionals, guides, art, etc. Every flats angler should make a Haj like pilgrimage to the symposium at least once in their life.

In recent years, BTT has applied its scientific research efforts to policy and regulation advocacy in Florida and the Caribbean. Their accomplishments are extensive, ranging from working with Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to implement catch-andrelease-only regulations for tarpon and

bonefish to helping establish six nationally protected bonefish conservation zones in the Bahamas. Again, if you are a flats angler, you need to know about and join BTT. Another important project, juvenile tarpon habitat management, is highlighted below and is described by JoEllen Wilson, BTT’s Juvenile Tarpon Habitat Program Manager. JoEllen oversees juvenile tarpon habitat research projects from South Carolina to the Florida Keys, mapping of juvenile tarpon habitat and education to the public through presentations. The main focus of this program is to create a framework that integrates habitat into marine fisheries management plans. JoEllen has worked for BTT since 2009.

As anglers we are inherent optimists, always believing we’re one cast away from a great fish. The sad truth is that we seem to be past the peak, and our “best catch” stories are more often reminiscing about the good ol’ days of large catches and dozens of shots. Now when we talk about fishing, the fish are fewer and farther between. What changed? Global recreational fish populations are decreasing, and in nearly all cases a main culprit is habitat loss. And to be clear, habitat includes things like seagrass flats and mangroves, but also includes the most important habitat of all—water. Any enlightened angler knows that healthy fisheries require healthy and abundant habitats and clean water. Coastal habitats are in decline due to development, changes in water flows, and excess nutrients and contaminants entering our waterways. These habitat and water quality problems are causing

the populations of our favorite fish, and the fish they eat, to decline. Unfortunately, standard fisheries management focuses on stock assessments, harvest regulations, and closed seasons to regulate fish populations. Absent from marine fisheries management strategy are habitat and water quality. In today’s approach to fisheries management, the solution for fisheries managers seems to be stricter harvest regulations with shorter seasons and tighter slots. This is unsustainable and unfair to conservation-minded anglers. Improving habitat and water quality is how you maintain a productive fishery.

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust (BTT) has

proposed a framework for fisheries managers to include habitat in management plans. The first task is to select a species with large cultural and economic importance to rally the support of anglers. It’s also import to have a sound scientific understanding of the species and its life cycle. Next, identify the habitats that are most at risk for human impacts. Natural habitats should be protected at all costs since they are intrinsically the most productive, and already degraded habitats need to be prioritized for habitat restoration. Now we put the plan into action. We focused on two economically important sportfish. Common snook and Atlantic tarpon, as icons in the fishing

community, are well-studied in the scientific literature, and their juvenile habitats are being decimated at an alarming rate by coastal development and outdated infrastructure. Juvenile tarpon and snook both depend on mangrove-lined tidal creeks and other back bay areas early in their life cycle, and it’s estimated that Florida has lost about 50 percent of its mangrove habitat statewide with 85 percent of mangrove habitat only partially available to juveniles on Florida’s east coast. To identify sensitive nursery habitat locations, BTT partnered with the fishing community to find current locations of juvenile snook and tarpon. Unsurprisingly, two thirds of reported nursery habitats were

classified as impacted or degraded. If the reported sites were natural, we earmarked them for protection through local and state managers. Degraded nursery habitats were then prioritized for habitat restoration using a ranking system developed by BTT, which includes data layers that account for restoration feasibility, species biology, and habitat connectivity. Each potential restoration site is given a score, and BTT has applied for funding to begin habitat assessment and preliminary design for six potential nursery habitat sites in southwest Florida.

Since we’re proposing habitat restoration as a solution, we first needed to

test if restoration could be successful for snook and tarpon nursery habitat. BTT’s habitat restoration research tested three different nursery habitat designs and determined not only is habitat restoration a viable option to combat habitat decline, but also which characteristics of the three designs created the most productive nursery habitat.

Not all restoration requires a complete overhaul to increase habitat, and there are some instances where small connections can make a big impact. BTT is currently overseeing two hydrologic restoration projects in Rookery Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Collier County, Fla. The goal of the project is to restore natural tidal flow to 1,000 acres of salt marsh and mangrove wetland that have been disconnected from tidal flow for decades by coastal development. Simply by restoring those connections, these habitats will increase coastal resilience from storm events and the amount of availability of nursery habitat for snook, tarpon, and their prey.

Other avenues that BTT is pursuing to circumvent the lack of habitat in fisheries management is to work directly with county land use planning agencies to guide development near nursery habitats. BTT is creating a Vulnerability Index (VI), with the intent that the VI is implemented by Charlotte County land use planning in southwest Florida. The VI will overlay juvenile sportfish natural and restorable nursery habitats with current and potential land use to determine which locations are most at risk. (For example, a natural or highly feasible restoration site that is at imminent risk for development would rank high on the VI.) This parcel would be flagged in the county land use planning software. Potential actionable steps could be to send the parcel to review by state resource agencies, move the allotted number of housing units to another developed area, or recommend a development design that is less likely to alter nursery habitat quality.

Conversely, a site that is already developed or has low feasibility for habitat restoration would provide a good opportunity to increase the number of housing units that can be pulled from a more sensitive area. In short, the VI will guide development in a way that reduces impacts to nursery habitats.

By creating and implementing this framework, we intend to revolutionize the way fisheries and habitat are managed and return our fisheries to their glory days. At a workshop hosted by fisheries managers, a well-respected guide said that we needed stricter harvest regulations because habitat loss and water quality are out of our control. Limiting harvest is not the answer to fewer fish—fixing the root cause of the problem is the only way to see our fisheries thrive. Anglers must advocate for habitat and water in fisheries management, because without healthy habitats, we won’t have healthy fisheries.

JoeEllen, photographed by Matt Bunting

JoeEllen, photographed by Matt Bunting

photo by Randy Farber

photo by Randy Farber

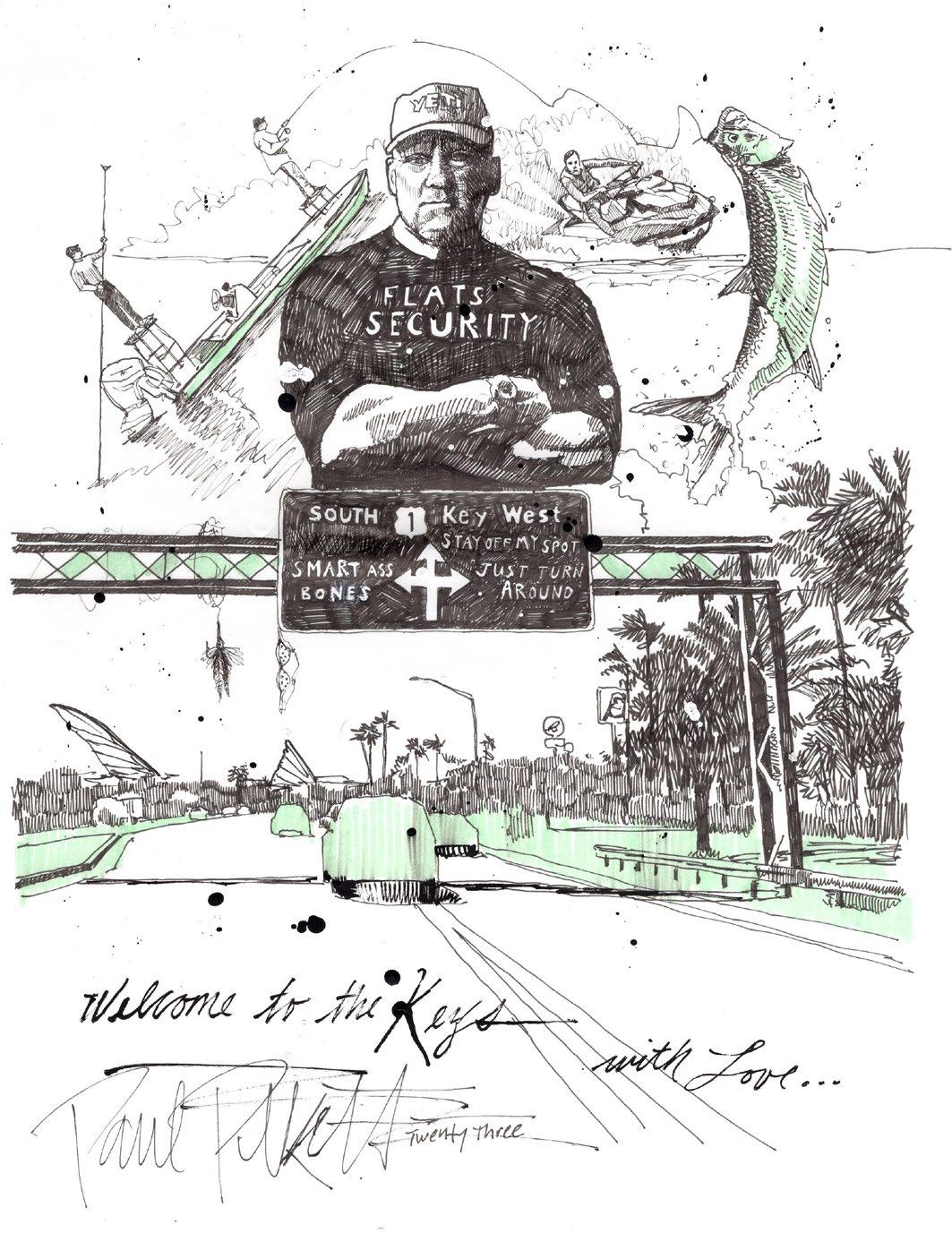

In my early twenties I once made it from Charleston, SC to Key West, FL in 11 hours flat, towing a boat. In an unrelated note, I also had really expensive car insurance. In those days we would leave SC somewhere around 6 or 7 PM and drive through the night so that we could arrive in the keys or the everglades by sunrise and launch the boat so as not to miss a single second of fishable light. I’m pushing 40 now, and I don’t bounce like I used to, so suicide runs are largely a thing of the past, and we have our system down to an art as to when to leave in order to time the traffic in Jacksonville just right. Even that means leaving at an ungodly hour of the morning and ensures that by the time you’ve ran the automotive Thunderdome that is south Florida you and your shotgun man are in various states of delirium. The haze usually starts to clear about the time you exit off the turnpike in Florida City, and you pass under the most famous road sign in the south. Depending on your mood you may take a right into the dark backcountry, or a left and charge across Biscayne to tangle with big smart bonefish. But if you hold straight and continue south, you’ll see them soon enough. The one thing that can flush the tired right out of your system. They’re a little worse for wear these days, but the aqua blue paint is still there, and the feeling it gives is still strong. Those barriers mean you’ve made it. Granted you still have a bit of a drive before you’re crossing the bridges and looking out at the flats to see If anyone is sitting on this famous spot, or that one, but the barriers say you’re there. I know the keys aren’t what they used to be and counting “leans” and “looks” isn’t really the game for everyone. But, despite the crowds, and the better than not chance you’ll get yelled at by a guide guarding his turf. There is still no replacement in my book for that feeling you get after 700 miles of I-95 South when you see those beacons of the keys. The bridges, and blue barriers.