he Firstnnual

M ORE FIGHT,MORE TOUCH

SALT

Load shifted closer to the hand prioritizes feel and recovery. 25% greater strength for increased pulling power.

Birmingham Native Brother Swagler Shoots the Goodnews River, AK 2023-2024

from the Creative Director by

Thursdays Below the Dam by

Larry's on Sardis Lake by cola photos by Logan Kirkland Letter

hank

Michael Garrigan

Shane Behler

Mike Steinberg

photo by Drew Morgan

s.c.o.f

Summer 2024 issue no. 53

SCOFFICE SPACE

Managing editor

John Agricola

Editor at large

Michael Steinberg

Creative Director & Design Chief

Hank

Director of Advertising

Samuel Bailey

Merchandiser

Scott Stevenson

Media Director

Alan Broyhill

contributors:

Charlie Hicks

Wes Frazer

Josh Broer

Colin Sutherland

Flip McCririck

Peter Taylor

Capt. Sam Glass

Paul Puckett

Casey Callison

Seth Fields

JD Miller

Capt. Matt Simpson

BJ Poss

Luke Bissett

Nick Williams

Daniel Roberts

Sam Sumlin

Managing editor emeritus: David Grossman

Creative Director emeritus: Steven Seinberg

copy editor: Lindsey Grossman

ombudsman: Shad Maclean

general inquiries: southerncultureonthefly@gmail.com

advertising information: sam@southerncultureonthefly.com

cover image: Craig Godwin and Teddy Guevarra

back cover image: Alan Broyhill

by

photo

Alan Broyhill

FAILURE is not an option

ABSOLUTE TIPPET

40% stronger UP TO WET-KNOT STRENGTH THAN PREMIUM COMPETITION

A letter from John, the managing editor

Dear SCOF illiterati,

I am not writing for any other reason than to say I appreciate you sloven bastards that sneak glances at our most recent issue while you are on the clock. Nay I would say this has always been the SCOF way. This is why our theme is a play on Mike Judge’s Office Space. Ergo the title of this issue: Scoffice Space. Stealing dimes of your concentration is like buying dimes from the street vendors for exotic transporting to other realms, or doing an enhancement of your fishing with a cheap buzz in mind. This is also the SCOF way.

But it is not enough. Maybe our analytics standards are too high. But your “community” flare will expire if we cannot pick up the pace of your consumption for our yarns of formerly oriental rugs we unraveled in the hope of finding residue of that diesel fuel I like to call bath salts. Just kidding. Or am I? No, we don’t use bath salts anymore. But we are afraid by our numbers that you all don’t read anymore. This is a challenge. You should take it as such. Go click around in this new issue. Click some hyperlinks. Look at the beautifully curated issue with all the pretty drawings and photos from the aesthetics department.

Or don’t. I don’t care. But do go click around to satiate your ennui at work. Someone should pay for our work and it might as well be your asshole boss. This is the true nature of a community equipped for the long haul. Stealing from the one that feeds your fishing habits is the American way. Dime bags for everyone, except your boss. He or she gets nothing.

Sincerely,

John Agricola Lead Managing Dirt Bag

photo by Logan Kirkland

Haiku

by hank

I cast, cast, cast, cast, Again and Again, and then you catch a musky

by

photo

JD Miller

Cold Chicken

Fby Dallas Hudgens

ried chicken is a culinary masterpiece. It transcends social class and could solve many of our cultural differences if push came to shove. It can be found anywhere and everywhere served to you on a plate, inside a bucket, box or a styrofoam container. Hot and crispy, fresh from the frier with flaky salt scattered over the golden pieces like savory jewels.

It’s always been a cornerstone in my nostalgic food arsenal but has recently become my favorite boat snack. Not only does it taste good, but it’s easy to transport and dispose of. It also helps that my love of cold fried chicken is almost at the same level as fresh.

I’m lucky enough that many, if not all, of the gas stations around me double as a country store and serve fried chicken for lunch and dinner. Only one, that I’ve seen, has figured out what to do with their leftover chicken from the night before, and they just so happen to be en route to one of my favorite little smallmouth rivers.

The bells ding as you open the door and the smell of coffee, biscuits and frier grease envelop you, sticking to your clothes for at least 15 minutes after you leave. At the front of the store, by the register is an open-faced cooler with pre-made chicken salad, sliced fruit, and white waxed lunch bags. On them, written in black Sharpie “1 breast, two wings, $3.78”. What a deal. Three pieces of chicken for less than $4. I grab a bag and set it on the counter next to a sleeve of Reese’s cups, for health. Walking towards the door my step feels quicker

and my shoulders light, the fried chicken effect.

The river I’m heading towards this morning is well known in the area, but not for fishing. It’s more of a geographical waypoint. It cuts through the heart of the county twisting and turning through farms, mountains, and parallel to highways. If you’re a trout fisherman, used to working upstream in tight quarters you’ll feel right at home on this water. Except there is no trout in this warm water. Smallmouth, red breast bream, and the Virginia Tarpon aka Fallfish, call this water home.

Fallfish, found from the VirginiaNorth Carolina border up the east coast to the Hudson Bay, are regarded as trash fish. Look ugly, taste bad, you get the point. There is a slight resemblance to tarpon, with their large silvery scales, which explains the tongue-in-cheek nickname.

They’re a good indicator on the health of a stream and river. Good numbers would mean good water, and the river I’ll be fishing today is full of them. It’s not if you’ll catch them, but how many.

I don’t have a shuttle, so I paddle my kayak upstream, working this river the same way as if I were chasing brook trout in the mountains. I target pools and runs while avoiding dead water. I throw my yellow popper at the base of, next to, and finally the beginning of a seam. On my last cast a 10” smallmouth smacks my fly and I pull it in. It was a good sign that the popper might be the hot fly today. I should’ve known better.

The next thirty minutes I had zero bites, not even a look, and when that happens on a smallie stream I tie on my tried and true, a kreelex.

The next several hours I put on a masterclass on how to catch fallfish. It had been a while since I’d last caught one and was reminded how undervalued they are as a sport fish. Strong takes and an initial hard run remind me of how largemouth fight.

After a morning of catching one smallmouth for every five fallfish my stomach caught up with me and a break was needed. A bend in the river with a little sandy bank looked inviting so I pulled my kayak over and sat in the sand. Next to me lay my rod and my waxed paper sack of cold fried chicken.

Two wings and a breast. I ate the wings first thinking of them as an appetizer, saving the breast for my main course. My hands, freshly cleaned in the river, still had a hint of fishiness that added to the experience.

With the chicken gone and my butt firmly planted in the sand, I roll cast my fly out in the pool in front of me. It wasn’t in the water for two seconds before I saw a flash of silver and my kreelex vanished. No stripping, no jigging, just letting the fly fall.

With a belly full of chicken, and a handful of Reese’s cups, it was time to begin paddling downriver and back to where I launched.

Walking or paddling my way back to the truck is where I get most of my thinking done. Problems get solved, anxieties are alleviated, and epiphanies occur. Most, if not all would agree, that this next thought is not an epiphany, but hell, it makes sense to me.

Fallfish are the cold fried chicken of Virginia fishing. Prevalent, undervalued, and scratches the itch when you’re

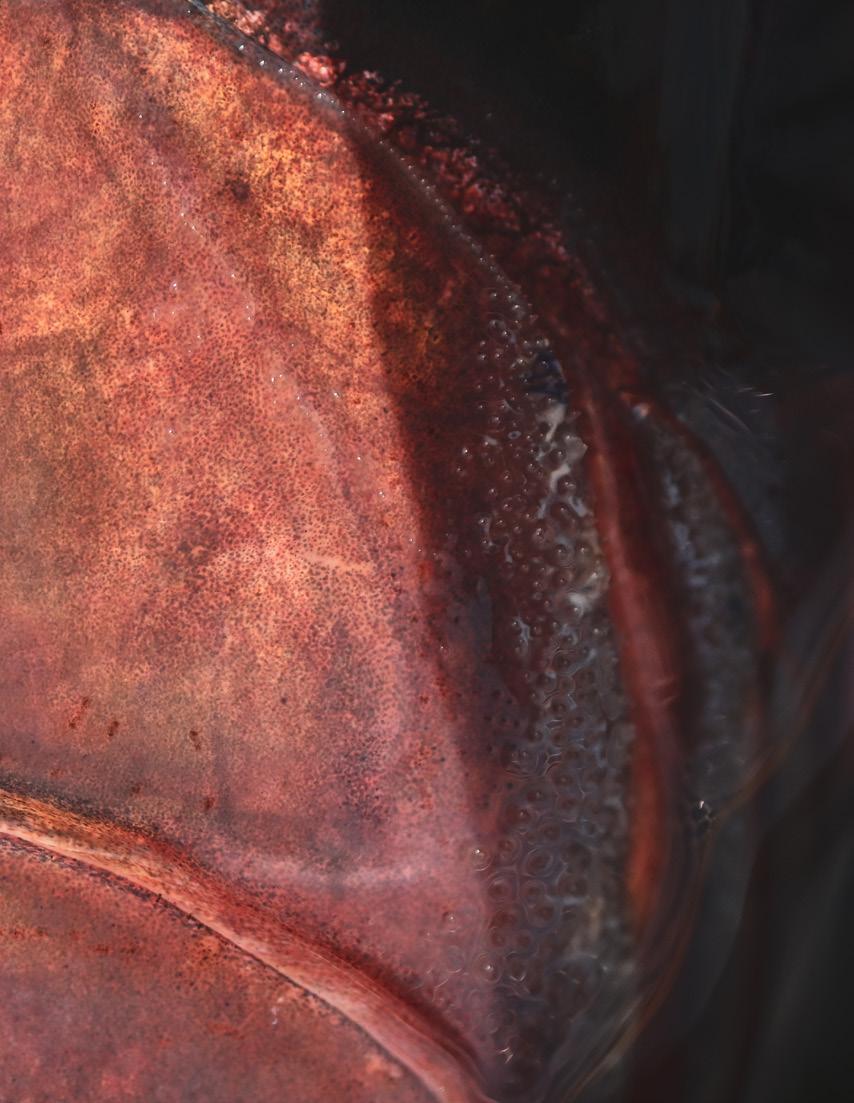

FALLFISH

a photo essay by

DOMINIC LENTINI

BUY SCOF MERCH

MERCH

...START A MOON COLONY

Presented By

Sage Experiences offers a curated suite of destinations that pairs world class fishing with state-of-the-art tackle. We are thrilled to present this exciting new destination demo program designed to offer guests an elite travel experience.

farbank.com/sage-experiences

Andros South Lodge

South Andros, Bahamas

Coyhaique River Lodge

Coyhaique, Chile

Estancia Rio Pelke

Rio Pelke, Argentina

Rapids Camp Lodge

Katamai National Park, Alaska

Bamboozled with Southeastern Anglers

by Cola photos by BJ Poss

Some fishing trips are divinely appointed, wrapped in both purpose and serendipity. What I mean is simple: Though planning was needed from both me and our guides, it felt like we were given the trip we were meant to experience—a gift of fate. Guides

Dane Law and Garner Reid of Southeastern Anglers have cultivated a steady clientele at a special Kentucky fishery on the Cumberland River, a powerful, wide river framed by rolling Appalachian mountains and steep bluffs. Its bedrock is limestone, layered with karst formations that jut deep into its aqua green depths. But to experience their shoreside hospitality and stunning Southern fly fishing, I had to set aside my longstanding “exile” from the Gadsden Fly Fishing Club.

Years ago, before my foray into Southern Culture on the Fly, I kept a blog chronicling my journey as a fly fisherman. My departure from the club was swift and final after I wrote about how misguided it seemed for a club to value camaraderie over conservation. Walking away meant leaving some good people behind. It wasn’t the club I missed, but the few members who shared my passion for the sport. When I heard Garner Reid would be presenting on his home waters, I decided it was worth attending. Garner, who reps for Tidewater Sales with clients like Orvis, Scientific Angler, and Sitka, has built his guiding career since 2008, taking clients out for trout, striped bass, and smallmouth.

We’d met a few years ago in Atlanta at a trade show—an unremarkable meeting among many, though I’d sensed a quiet confidence in him. When I got the club’s email about Garner’s talk, I decided to break my fly club fatwa and go.

Dane Law was there, too. I remembered him from a decade ago, when he presented solo to the club. Dane founded Southeastern Anglers almost 30 years ago in the early to mid-90s, and his expertise in fly angling was readily apparent when you spent time around him. He was a friend of Frank Roden, and that endorsement was enough for me. Roden, a fly shop owner in Gadsden, had been a mentor to me, sharing his beloved carp flats and patiently guiding my purchases over the years. About six years ago, I bought two bamboo rods from Roden: a Heddon Black Beauty and a 1937 Granger by Wright & McGill. Recently, I’d also inherited my great-grandfather “Big Daddy’s” Hardy rod from the same era, a cherished relic with his name embossed on it and the Hardy crest on the reel seat. The Hardy rod had been refurbished in Chattanooga, bearing Hugh’s name and hometown of Gadsden instead of its original markings. I took all three rods to Roden’s shop to fit them with fresh reels, choosing balanced floating lines with Roden’s guidance. My goal was to make this trip a combination of showcasing the Cumberland and fishing with rods that hadn’t felt water or the weight of a fish in generations. In Greek, telos means “purpose.” Every object and being has one. I felt the Hardy rod’s purpose— the reason it was crafted—hadn’t been

fulfilled since my great-grandfather chased willow fly hatches in Guntersville back in the 1940s. Its unused potential seemed almost detrimental to the rod’s soul. After all, a rod built to bend to a fish’s weight deserved to do so, and this trip felt like an invitation to fulfill that purpose.

I invited a few friends I’d met through the magazine. Frank Armstrong and BJ Poss would make long journeys to converge on Burkesville after Halloween. We’d never met in person, but I admired their work in past issues. Frank, a tattoo artist with a deep connection to fishing, had just guided a friend to a 46-inch musky near Bowling Green, Ky. BJ, on the other hand, favored alpine brook trout when he wasn’t making wine in Virginia, a skill he’d learned on New Zealand’s South Island. But fate had other plans: Hurricane Helene forced us to reschedule for the only date Southeastern Anglers had left before the next issue’s deadline. I drove four hours after trick-or-treating with my son, wanting to experience Halloween with him before the trip.

When I arrived, BJ shared my curiosity about fishing bamboo. We’d both read the late great writer John Gierach’s book On Bamboo before the trip. It was both an homage to the writer who celebrated bamboo and a cautionary tale. Gierach’s advice about not leaving a wet rod in its sock might have saved me from mildew. He also dispelled the myth of bamboo’s fragility—he claimed it was sturdy enough for fighting big fish, and I needed that reassurance.

As we gathered in the parking lot, Dane eyed the bamboo rods with mild skepticism. BJ asked what rods people typically used. “Not bamboo,” Dane said

with a sidelong glance. Gierach had warned of Dane’s possible wariness, “Guides don’t like the liability of heirloom rods, knowing a break might feel catastrophic to a client.” I reassured Dane, “Look, I won’t see a broken rod as a tragedy. I’ve got extra tips, and fishing with bamboo is my ‘Trojan horse’ here.” What I meant was that my humanity—my story—was woven into that rod. Fishing with it connected me to my great-grandfather and my father, who’d kept the rod safe for me one day to hold. I wanted to feel the rod’s soul, perhaps to understand my own.

Southeastern Anglers’ jet boats had ample rod holders for our three bamboo rods, one for each of us. But as the day began, I sensed that this river held as much mystique as the rod itself. Casting a hopper and stonefly dropper, I bounced the nymph off bedrock, making small mends and subtle twitches. Soon, I had a beautiful rainbow trout, iridescent and nearly 17 inches. Frank Armstrong landed a few more from the boat. It felt like I’d known him and Garner forever. Garner, a Cartersville native and Missoula guide transplant who’d honed his craft at Cohutta Fishing Company, spoke of how the South and its striped bass had drawn him back home to Reliance, Tennessee.

Frank Armstrong’s presence on this trip was more than just friendship. His talent as a tattoo artist was his telos, and I knew few people as skilled with a fly line. After fishing, I’d planned to get a tattoo from him honoring my father, despite my dad’s skepticism about tattoos. I wanted a box turtle design, inspired by my dad’s spirit animal, and his final words to me: “Don’t get in a hurry.”

Then, serendipity struck. A turtle bit Frank’s stonefly, doubling over the Orvis Helios 4 Garner had equipped. Though it might have weighed 10 pounds, the rod held strong. Secretly, I was relieved Frank wasn’t using my bamboo rod. By lunchtime, we’d landed several 16- to 18inch fish. Over fried chicken and biscuits, Dane and Garner hatched a plan to head further downriver to an imposing rock wall. It was our “Hail Mary” move. Sure enough, I caught another 17-inch beauty, closing the day on a high note.

The Hardy rod had fulfilled its purpose, and, in a way, so had I. I came to this river to feel a connection—to the past, to family, and to my own journey. And I left reminded of the lesson my father, and that old Hardy rod, both taught me: to savor the moments and never be in too much of a rush to do anything.

Bluegrass and Brimstone

by BJ Poss

You’re Frank Armstrong. You’ve buttoned up the field camouflage wool overshirt to the butterfly resting at the base of your neck. It will get all it can handle in the late fall breeze. You drive past your pull-off once because there’s a pick-up coming the opposite way, and you’re weary of unnecessary interest in what may lie beyond the tree line. You’re due in Georgia tomorrow for an expo, but the illusion of sunk cost in five previous days on the water is weighing on you. 10,000 casts- is that over a lifetime? A week? River? Year? Best not to chance it.

Ought to turn around and hit the road now; Atlanta is every bit of three hundred miles from Bowling Green, and a proper helping of hot wings would do you good. You can almost hear the tattoo machine buzzing to break out of the Pelican cases of tattoo equipment in your trunk. The warm car is cozy, and if you fiddle around much longer, you’re liable to slip into the notion of not freezing your ass off for the next twelve hours and hit the road. But miles and frostbite be damned, you stuff the Mama Turney‘s pecan pies in your jacket pocket and offload the kayak from the roof of your car.

It’s one of those dreary days that your dad always says is "when the water gets full of musky." You have a hard time discerning if it’s just morning fog or a light mist, the kind that’s good for sitting in a dive bar, but after a few hours on the water, that plate of hot wings will sound like the obvious choice. Your fingertips are already starting to glow as you pull a folded-over sinking line through the guides of your 10 wt.

The river is steady with an oak-ish gleam, the same one as the watered-down nightcap on your bedside table. There are two downed trees about a hundred yards off the bank; they must’ve fallen in last night's storm. You can make out a passage between them just big enough to fit your kayak, but they’d be a day buster if you were in a raft. There’s good water just on their other side. The only worry is that the underwater structures have tumbled around enough that the three-footer you caught on a crankbait the other day might have found a new hole.

You launch and paddle past the downed trees, which makes for a delightful cove. The cover gives you solace that if the pick-up did, in fact, see you turn off and find your parking spot, he’d figure you had gone downriver and be off your scent.

You fight the urge to throw on a chartreuse streamer that you’re sure will land some smallmouth, likely a good one, and tie on an articulated orange bouquet, turkey tailfeather and all. Before throwing it, you flip it around your palms for a bit, survey the weight, and let all its bits fall in contrast to the fading spearhead buried in the back of your hand. You liken the fly to more of a watercolor than a needle gun. It’s almost downright sweet that a toothy thrasher of piss and vinegar takes to something so delicate.

Being born into a family of artists often leads to chasing inspiration. Your mind wanders from the fly and you consider (again) moving to Nashville. You could up your rate if you were to work in one of those shops near downtown. Bachelorette parties are lined up for matching thin lines, wobbly walk-ins, and the chance that, at any point, your next customer could be in the news for a strong, public conviction

about Morgan Wallen’s brand of country. But for every fiddle player they’ve got downtown, they’ll never match the sound that hits a West Kentucky river at daybreak. You float to the middle of the river and cast the bouquet tight to the bank. You work the line in short spurts, slow enough that something to take notice but not so lazily that it’ll sink and snag a log. Once your casting is dialed, you move upriver and around the bend to where you got the crankbait musky. It had taken a good four days of thankless casts, but now you know they’re in there forever. The fly rod musky would damn near complete your things to do on this river, but it’d only open your window of things to master.

You get up to your hole and rip off a decent cast. When it comes up limp, you water load it five feet to the left, just under an overhang. Strip, strip, wiggle, strip, wiggle, and there she goes. A good thud takes your fly upriver, and your chest churns tight. You don’t know for sure that it’s what you’re after, but it could be. You play it back to open water. It’s heavy as it is angry, but you begin to think it may be a false idol. Nothing but another trophy smallmouth; its bottom was dark like it’d been bathing in a mud pit and hadn't washed up for supper.

On you go, you cast until it’s time to take a late lunch on a stone island. Your arm is growing tired of the weighted line and circling your rod tip in the river. You let the fly spend time below the kayak, watching how it flutters in different water columns. You assess depth like a needle tracing your outline of a smoking cowboy skull on a customer's inner arm. The deep sections are met with some pushback, where the river doesn’t want you to go, so you pull up in the column to achieve the

smooth lines, occasionally dipping back down when necessary. You feel for the river and its displaced timber, the smallmouth bass with a streamer stuck in its jaw, and your client getting willfully wounded in the name of permanence.

You pull the Atlanta Braves hat over your face and lay in the sun, peeking over a dreary sky. Your father wore the same one when he traveled to Canada to chase musky. You think of the fiberglass 5 wt that he leered from the dusty corner of your childhood garage; you think of the deer hair popper that was always tied to a knottedup leader. Before you’re settled too deep into the stone bed, you get up and rig up a floating line with an olive Dahlberg Diver Toad.

You cast from the island to stretch your legs; the plop of the fly is reminiscent of fishing for bass with your dad on grassy ponds. You lose yourself in the melodic casting. The whipping of the plastic line quiets your heartbeat like the buzzing of the needle gun. You assess your line and retrieve and not much else.

You’re casting with your dad now. And his dad beside him casting too. You for musky, your dad for bream, and grandfather for crappie. You can hear them talking. There are these pulses of threads and veins between the three of you that you can’t get rid of. It goes even beyond them. It goes to your great grandad in the fifties, going straight from the oil rig to catch Guadalupes.

The toad is popping towards you, it’s barreling down I-24 past East Nashville and everything steering you from a Kentucky shoreline, it’s got four generations of Armstrong pulling on it, it’s the sixth day on the water, it’s the something-thousandth cast, it’s violent splash- and it’s gone.

Check out Frank Armstrong’s work and art @frankarmstrongtattoos on Instagram; you can purchase prints or book a tattoo appointment in Western Kentucky/ Middle Tennessee.

The Premier Fly Shop in Blue Ridge, GA

we auction off page 69 of every issue for charity.

The winning bidder gets to put whatever they want on the page (an ad for your niece's etsy, an embarassing picture of your friend, your ex's banana pudding recipe, etc.) and pick the charity.

SHOP THE SCOF STORE

Cowboy Bones

by JD Miller

The golden ghost, the freshwater bonefish, Oklahoma/Arkansas bonefish, blue-collar bonefish, redneck bonefish, hillbilly bonefish, trumpet-mouthed trout, pond pig, mud marlin.

Carp come with a host of nicknames bestowed upon them by the angling community, some obviously given in love and admiration, while others, maybe not so much. They are all great monikers in my book, but my personal favorite is the cowboy bonefish. It’s most likely my favorite due to my personal affection for cowboy culture, or maybe the undeniable parallel of characteristics like grit, toughness, tenacity and bullheadedness that are inherent to both the essence and the identity of the cowboy and, come to find out, the carp.

This was my first rodeo. Seriously. As shocking as it may be to the readers of this refined, genteel publication, never before had I chased carp on the fly— on purpose, that is. More than a time or two, I’ve fallen victim to a common case of mistaken identity, chasing down my amalgamations of feathers that were undoubtedly predestined for the jaws of my preferred quarry, smallmouth bass.

But, never had I gone out with the specific goal of targeting carp with “the fairy wand,” which is how my conventional bass fishing friends lovingly refer to my fly rod. Not that I had anything against going after carp, although I was raised in a house of learned doctors vehemently against the practice of actively fishing

for “trash fish” (not really on the doctor part, but you gotta use a Step Brothers reference when you can. “Don’t touch my drumset!”). It looked like a good time. But it just so happened that when I had the time to fish, bass were always numero uno en la cabeza. Maybe it was all the buzz on the socials about the Great Southern Brood XIX—which would reach its western limits in my stomping grounds—that got me eager to jump on the carp train. Or maybe I had just always been a little carp-curious. Whatever the reason, I was ready to climb on the back of the proverbial cyprinus carpio bull and hang on with the fervor and determination of a young JB Mauney. It was time to cowboy up. Let ‘er buck.

A good friend and frequent fishing buddy of mine who I’ll call Cole (because that’s his name), has lived a double haul away from an impoundment in eastern Oklahoma for a few years now. He presented the opportunity more than once to chase carp in a shallow cove of the lake, practically on his back porch. In fact, on more occasions than I can count, he has brought up an actual “tailing bonefish on the flats” type scenario reminiscent of Andros Island, or as close as you can get to Andros in Okie-land, USA. I, of course, didn’t fully believe him, so I had to find out for myself. It took a minute, as the responsibilities of life, especially as you get older and have offspring, tend to get in the way of these types of activities. We finally connected for a few hours on an early summer evening after I got released from the nine-to-five prison for my first true carp rodeo. Carpe diem.

On the hour-plus drive from work to my buddy’s place on said summer

evening, I writhed with anticipation. I felt as if I were an actual bull rider getting “mentally right” for my eight-second dance with death. Short jumps, side to side, repetitively shifting my weight from my right foot to my left foot, then back to my right again, shaking the nervousness out of my body by coaxing it down from my shoulders through my forearms and finally out through my wiggling hands and fingertips — I was ready to tango. As I visualized sliding on top of the beast already loaded in the chute, nodding my head, and then hanging on for dear life through the ensuing twists and turns that would surely follow, I realized that I didn’t truly know what this experience would hold in store for me. Was the hype real? Was this place an undiscovered Bahamian flat in Oklahoma? Would the fish be there like Cole said? Would they eat? Would these fish live up to their bonefish comparison? Would I be able to make the shots necessary to feed ‘em? And if I did…would it change me? Would I become a carp addict and start spurning other species along with my mainstream fly fishing buddies because they didn’t understand, because they simply “just don’t get it?” Would I start seeking them out closer to home, peering into the murky waters in and around the municipality of greater Tulsa? Loitering near random bridges, wading through audacious bums, hypodermic needles, and swimmer’s itch just to connect with ole slimy sweet lips? These were all burning questions that I needed extinguished as I pulled into Cole’s driveway. We only had a few hours of daylight left, so we exchanged quick pleasantries, bumped fists, and headed to the lake. As Cole’s SmithFly — which he had expertly equipped with a redneck

platform (cooler) and push pole (PVC pipe) — splashed in the water, I took my place at the bow, my guide atop the cooler. As if to complete my pre-ride ritual from the drive out, I whispered 10 Hail Marys and pointed up to the Big Man as a gesture of thanks and hopefully, good luck. I was ready.

My first rodeo did not go as planned. The next few hours were humbling. We came. We fished. The carp conquered. Or, to continue with this rodeo/cowboy metaphor: We got bucked off, hard. The carp threw us high and far, and once we smashed into the dust and mud, they trampled us to boot. Fishing was tough. Like Tuff Hedeman tough. As far as I know, I never put my fly within three feet of ole sweet lips and it wasn’t because they weren’t there, it was because we couldn’t see them. We couldn’t see them, that is, until we could. To clarify, we saw them quite clearly in the form of wakes moving at breakneck speed away from the SmithFly, as Cole tried his darnedest to pole us silently over the flats. So, the fish were there, but they weren’t playing. It was frustrating to be so close yet so far away at the same time. They seemed to be living up to their apparitional nickname more than their western sobriquet. Whether it was piscatorial phantasm or plain old cowboy stubbornness, the carp went uncaught.

Now I could sit here and list a bunch of reasons as to why we didn’t get it done: the carp weren’t feeding like they should have been, the fish weren’t shallow enough so we couldn’t see them tailing, Cole was blessed with so much redneck ingenuity that God made him a shitty guide to balance things out, too windy, not enough wind, I forgot to wear

my lucky drawers, there was a banana within 100 miles of the raft, the list could go on, and on, and on. But cowboys don’t make excuses. They get up, dust themselves off, ignore whatever injuries they may have sustained (including the damage to their pride) and climb back onto the beast. I was quickly learning that I was going to need some of that carpcowboy stubbornness myself to get the job done. I vowed right then and there that I’d be back to the rodeo grounds someday, and for my second go-round, I would return with experience gained and a determination to be the bull rider, not the rodeo clown –– my lip packed with Copenhagen and my soul with conviction.

Hope you’re good enough.

Accept the challenge.

Request approval from spouse.

Book dates a year out with favorite guide. Pray for good weather, hungry fish, and adequate performance.

Try to forget about the trip.

Remember the trip. Pray again.

Feel guilty for praying about fishing. Quell premature excitement.

Practice casting in the yard.

Answer your neighbor’s questions.

Decide that a lawn is nothing like a flat.

Hope you’re good enough.

Watch Billy Pate make it look easy.

Allow yourself to be excited.

Don’t let it show.

Watch Tarpon.

Text your buddy to confirm plans.

Wish away summer squalls.

Pack your bag.

Travel south.

Arrive at the coast. Text the guide.

Procure boat snacks at Duren’s.

Notice tourists unloading snapper at the marina.

Ponder if you picked the wrong quarry.

Find a decent place to eat that doesn’t have a long wait.

Eat something you won’t regret in a few hours.

Check into motel.

Pack essentials, but not too much.

Determine which time zone your phone is showing.

Set alarm for 5:00am (eastern).

Hope you got the time zone right.

Set another alarm just to be sure.

Watch JAWS!

Remember it’s just fiction. Attempt to fall asleep.

Wake up.

Meet guide at 6:00am. Make small talk to reduce jitters.

Board the skiff.

Eye the rod.

Ride during the sunrise.

Inspect the clouds.

Scan for rollers.

Arrive at the flat.

Stand with shaky knees. Watch guide position the skiff.

Grab the rod.

Mount the platform. Battle nerves.

Watch and wait.

Spot cruising tarpon. Control heartbeat.

Analyze angle.

Cast the rod.

Hope you’re good enough.

Tarpon Self-Talk by

Tarpon Self-Talk

by Drew Morgan

caddie shack

Dear Jon: A Love Story of Sorts

Henry Hooks photos by Tall Tails Media

Okay, I lied. Not a love story. Unless you’re in some sort of strange, masochistic, hierarchical, demanding entanglement. Because that's what this is… a demand.

Open your dad’s favorite social media: Zuck’s brainchild. Go to the greatest gift that man has bestowed upon his people: Facebook Marketplace. Adjust your search radius for as far as you're willing to drive to not be a boatless nobody, and type these words: “jon boat.” Feel free to be more specific if you’re overly concerned about total length and beam width and whatever other buzzwords those nerds are throwing around these days. Then every day for two weeks, like it's your job, scour that data-stealing virtual estate sale. If it looks pretty in the listing, it aint worth your time. Some redneck already got his calloused paws all over it and you can bet your ass it's a Porsche paint job on an ‘01 Saturn. Trust me, and this is the only time I’ll say this, be patient. Good things come to those who spend every waking moment on Facebook Marketplace. If it looks like it's been sitting in a garage for twenty years and grandpa just passed, jump on it. If it looks like an angry wife has finally had enough, it's lowball time. If it looks like a very fortunate Mexican bricklayer just purchased a house from a recently “rehomed” old man and that old man just happened to leave all of the contents of his garage in the selling of his home, and that Mexican man lists a boat full of junk with a trailer and a motor for $700, then

"Good things those who waking marketplace"

things come to who spend every waking moment on facebook marketplace"

give me a call because ain’t no way it happened twice.

Now, I am well aware of my fortune in this particular matter, in having found a ‘diamond in the rough’ as they say. But I am not the first, nor will I be the last in the long and rich history of Marketplace scores. I came across a rather forlorn listing of a boat full of garbage on a decrepit trailer with the simple description, “Bassboat.” I saved it, and somewhat forgot about it as my saved folder was piling ever higher with the leftover scraps of former fishing glory. One morning, as I woke to my daily ritual of scrolling mindlessly through the junk of those who share my zip code, I figured, what the hell, let's pay another visit to that single photo listing. For a sticker price of 700, it couldn’t hurt. I shot the owner a message requesting more photos and what I got back was like opening a mangled oyster to reveal its pearly prize. Beyond the first few photos of the average looking boat was one blurry snap of a pristine 15 horsepower Mercury two stroke. Hoping my anticipation did not translate to my fingertips, I cautiously typed, “Is the motor included for 700?” Without skipping a beat came the reply, “Yep. I don't know much about boats, sorry, I don't know if it works or not.” Bingo. Gametime. Touchdown. Whatever. I was about to own a boat.

I took cash (and my firearm, like a good American) to my new best friend’s house, knowing that it would take a cannon sized hole in the bottom of that boat to convince me to walk away. In fact, I was so committed, I bought two different sets of trailer wheels at the poor man’s Home Depot (Harbor Freight) before I got there so that I would have no trouble rescuing my maiden from the clutches of her ill-informed inheritor.

The motor was even more stunning in person. It seemed like it had lived its whole life in that garage, unsoiled by the defilements that had come to so many of its counterparts. The boat would certainly do the job that I had planned for it, and the trailer simply needed one of those pairs of wheels I had so fortuitously purchased. I said how about $650 just for fun, he said okay, we signed a bill of sale, and I drove off, cringing at every pothole that rattled the bones of my soon to be partner in crime.

Now comes the fun part and the return to the demands. First, gut that aluminum bucket to the hull. Vacuum the wasp nests out from under the benches that remain, give it a good pressure washing, and scrape the years of boat registration stickers off of the bow. As you stand back to admire your blank canvas like some grizzled Van Gogh with a PBR in hand, you might catch yourself with visions of personal best browns dancing across the not yet painted gunnel. Bad news pal, you’ve got a long way to go.

I reached out to the city and asked if I could have a few of their larger street signs that had been retired from service. These worn out aluminum sheets would be perfect for fabricating a floor and casting deck, and best of all, they would be free. I got a call from the head honcho asking a few too many questions about my plans with said signs, but eventually, he obliged, and I found myself melting the skin off my fingertips as I threw signs out of the scalding dumpster in the back of the shop.

Collin and I dedicated an entire weekend to building the floor and casting deck. Naively, I assumed this would be an exorbitant amount of time to spend

on cutting 14 feet of metal. Let’s just say that not a single component of a late 60s Polarkraft is square, straight, or level in any way. I spent my weekend playing measure twice, cut ‘till it fits. Eventually, after a few beers, lots of hose water, and a nearly cleaved finger, the shell was done. Now, as someone who was running on a dubiously tight budget, I was not about to send off for a custom boat decking from the big dogs. So, Mr. Bezos’ brainchild got some love and two rolls of eva foam boat flooring arrived at my door two days later. These rolls were also accompanied by cans of paint and marine primer to complete the makeover. Sanding, grinding, washing, stripping, washing again, sanding again, and washing yet again was no small task. No sooner had the sun vaporized the last drop of moisture from the interior than I was painting. Double coated, touched up, and finally, left to bake. Floor was cleaned, stripped, and adhesive sprayed. I had made templates out of posterboard for the foam flooring, but like everything else on this godforsaken hunk of metal, it was far from perfect. However, it set me up just well enough to finish the fine details with the flooring in place. It was, at last, resembling the image I had conjured in my mind so long ago. Following the addition of some smaller trinkets like oarlocks, an anchor, and cooler mounts that had been acquired and/or purchased over the course of the build, she was taking on the look of a proper vessel. All told, I had spent less than $3,000 on the entire project. If I was not planning on ripping up and down the White River, eliminating oars would have pushed that number far closer to $2,000 than I would care to admit to my wife.

At this point, all that remains is the christening of your fair lady and shoving off into the deep. If you are a man of few words, then let it be so. If you are more of the eloquent type, invite your friends and neighbors for the momentous occasion. At this point, you are on your own, as no man should command another what to say. But just in case you were curious, mine went something like this:

Dear Jon,

May your rivets hold fast and your hull never know pain. May your oars steer true and your motor run mightily. May your deck always be stable and your cooler always be full of cold beer. May fish flock to your gunwale like moths to a flame, and may you be a source of joy for all the rest of your days. And when the days get long and life gets in the way of our time together, no matter how many weeks go by, I know one thing will be as true as it ever was: I will see you soon.

The Surly

PROUD LARRY'S ON

ON SARDIS LAKE

by cola (aka Trey's Daddy) photos by Logan Kirkland

Proud Larry's on Sardis Lake

by Cola

(AKA Trey’s Daddy) photos by Logan Kirkland

Trey’s daddy went to school at the University of Mississippi back in 2013 and 2014. It was about a decade after the late great southern grit lit author, Larry Brown, had passed on to the other side. Trey’s Daddy had known Brad Watson before Brad passed on, not to mention the number of folks who knew Airships author Barry Hannah that Trey’s Daddy had known personally over the last decade of writing short stories and nonfiction stories. Trey’s daddy was the worst kind of husband and father. Always leaving the boy during inopportune times like when the kid had an early morning soccer game on Saturday. As this dereliction of duty happened the weekend Trey’s daddy’s buddy, Jason, had offered to go with him to Lafayette County, Mississippi, and help him conquer what he thought was an interesting bass lake. Trey’s daddy figured his buddy had enough electronics from Garmin to Livescope to find fish anywhere and on any given lake. Trey’s daddy was wrong about this fact.

He knew that he might be wrong. He often was mistaken about his own abilities. But Trey’s daddy knew he had lived a rich life a decade ago in Mississippi, and though he was not licensed to teach in the school system, he could teach Jason about the cultural heritage of the land of Ole Miss. Jason built houses for a living, but invested an important amount of his time into foolin’ with largemouth bass. Trey’s daddy was a carp angler and sometimes would accompany Jason for bass in and around Guntersville Lake, and

yet Trey’s daddy was nostalgic about the land he left a decade ago.

Trey’s daddy and his buddy Jason left Gadsden early Friday morning. Trey’s daddy’s momma would pick Trey up from school on this day. On the highway through Jasper, the men discussed how Walker County, Alabama was like the Netflix series Ozark without the water, but Smith Lake was close enough, they discussed. Jason insinuated that it was a difficult place to live and that bodies sometimes went missing in cavernous holes from the mining trade there.

Jason knew enough about Alabama cultural histories, and he was curious about other places, but sadly he had gone to Auburn. Trey’s daddy went about explaining synopses of William Faulkner books ranging from Absalom, Absalom!, to As I Lay Dying to Go Down Moses,

Trey's Daddy's Buddy Jason

specifically explaining the dichotomies of “wilderness” and “culture” that “The Bear” represented. Trey’s daddy even checked the stories he told against ChatGPT to make sure he had not misremembered anything. He finally described The Sound and the Fury and checked it against the computer. Jason would never enjoy Faulkner, Trey’s daddy realized as he got through reading about arcane subjects like passing for white, rape, incest, and generational decay.

Trey’s daddy remembered how he had so loved the music scene in Oxford, from the North Mississippi Allstars he saw play at Proud Larry’s that drunken night with his friend, Leslie. Or the numerous times he hung with Jake Fussell after sets at Lamar Lounge. He decided to play Cedric Burnside and tell of the Turner family picnic he had visited early in Trey’s daddy’s time in Senatobia, Mississippi, when he and some classmates ate goat sandwiches on white

bread and ate moonshine soaked gummy bears while Sharde Thomas, Otha Turner’s granddaughter, continued his tradition of Revolutionary War era fife music. When Trey’s daddy realized Jason was not familiar with blues music, he switched Spotify to an R.L. Burnside playlist for good measure. But Trey’s daddy really wanted Jason to understand why we had come four hours from great bass fishing in Guntersville to a Tennessee Valley Authority impoundment in Mississippi that was known to most as a Crappie Lake. Trey’s daddy assumed there would at least be as many bass on Sardis Lake as there were on Neely Henry Lake in Gadsden. And the cultural analogs were certainly rich enough to try for an article. It dawned on Trey’s daddy that Larry Brown was a lot like Jason. Brown had been a mechanic, and a firefighter in Oxford before forcing himself into learning to write by treating the practice

Trey's Daddy

of writing like any trade—something that could be learned. Building suspense was a practice not unlike framing a door in a home. So, Larry had practiced the cadence and rhythm of good storytelling. Trey’s daddy knew this because he had listened to A Miracle of Catfish, Larry Brown’s posthumously published novel on an audio book on his phone. So the two knuckleheads driving Jason’s Tundra and Ranger boat to Abbeville listened to 25 chapters of A Miracle of Catfish by Larry Brown on audio book.

If they were in the truck they were listening to this masterpiece that weaves various families together around the building of a catfish pond in a man named Quartez’s farmland. Trey’s daddy had heard this story before he came to Oxford, and may have falsely presumed that fishermen are alike in every sub-region. This is only true in part. As Jason and I scanned the Martian landscape that was Sardis Lake, the water revealed a drought was upon

the people near the Mississippi towns of Pontotoc, Water Valley, Holly Springs, and Abbeville (where we were staying). Trey’s daddy and Jason turned down the narrator’s voice as they approached Hurricane Landing in Abbeville. It was mud flats for miles with flooded timber everywhere. At full pool, surely this place held bass. The lake had dissipated from 16 miles long to 8 miles long. The Abbeville ramp was unusable, so Trey’s daddy and Jason went towards the Lower Lake by the big rip rapped dam. Surely there are bass on those exposed rockworks. Trey’s daddy and Jason saw characters from A Miracle of Catfish all around them. But there is one important thing about Trey’s daddy’s plan that needs to be considered. He assumed a TVA lake would have bass. The men covered every situation available to them, and Trey’s daddy threw streamers and poppers on floating line, intermediate, and full sink line. The turbidity of the water was extra silty

because no trees were present to block light wind through the desolation. The men looked around them and realized this dream was not theirs. In the sub-region of North Mississippi, people trawled, and then setup over the top of schools of crappie, and watched as they hammered fish all day. They caught some white bass and a few Proud Larry’s, but this was a crappie lake with a rich cultural heritage enveloping the forests and farms outside the town of Oxford.

After fishing the first day, Trey’s daddy ate some delicious gas station catfish filets and squirted ketchup all over them. In A Miracle of Catfish, Jimmy’s daddy’s family drama was set in Yocona, Mississippi. We passed beautiful AirStream trailers fit for kings up and down the Purple Heart Memorial Highway. The Two Rivers Landfill was out of sight, out of mind, but for the sign. The barren desert landscape was viewed from the launch, and so Jason interrogated two cops sitting on the side of the road where the other put-in was, and they obliged his questions. On the way to the ramp with water, the men passed kudzu covered oak trees. It became very clear that just as in Brown’s book about miracle catfish, it hadn’t been raining here. The pond would never fill up if an act of God did not bring rain.

Trey’s daddy and Jason ate like squires on the Oxford Square after day one of fishing. McEwan’s served them delicious steaks and Chilean sea bass. They drank and stuffed their faces for the consolation that was a good meal. When they got home, Trey’s daddy wanted to surf the dating landscape in Oxford, so he pulled up Ashley Madison to look around at the beautiful belles Mississippi was known for, and then his battery died and

he fell asleep. Still they would fish again the next day. Once beaten again at the end of day two, a man called Trey’s daddy who said he was the head of a cartel, and that Trey’s daddy owed him 4,500 bucks for wasting his girls’ time. The cartel leader pressed further that he didn’t want to involve Trey’s Daddy’s family in Gadsden. The man promised to send 12 men to beat the money out of him. Trey’s daddy said to the cartel leader, “You won’t need 12 men, one would probably suffice.”

Then Jason grabbed the phone from Trey’s daddy’s and said, “Look what you are doing is illegal. It is called sextortion and we will call the police.” He hung up on the man and blocked the number.

Trey’s daddy limped home to see Trey and Trey’s momma, but as he listened to Larry Brown’s narrator, a story was told that rang with a certain veracity that transcended the truth Trey’s daddy had observed in himself. In it, two businessmen from Oxford who did not know shit about shit wanted to have a fish fry. They had gone down to the Tennessee River that fed the lake, and put in a few gallons of Red Panther Cotton Poison, killing miles and miles of fish because they wanted to have a fish fry. Trey’s daddy didn’t know Larry Brown, but this story may have not been too different from a lake that was cleaned out to become strictly a crappie lake. Just because a couple of assholes from town wanted to have a fish fry, and wanted to catch fish without fishing.

next issue February 24th, 2025

Dear Reader,

When I first started as the creative director for SCOF, I wanted my job to be like painting. With broad strokes and fine marks, I wanted to paint these virtual pages with the resemblance of the anglers I met and fished with, the places we fished, and the fish we caught. I wanted to fill the canvas with a vision of the best angling life I could imagine. This magazine would bear the likeness of Southern culture thanks to my brush. But I had a realization recently while making actual paintings that my job at SCOF is different. I’m holding the mirror while y’all paint yourselves.

Therefore, I deserve no credit for the image taking shape here now: a masterpiece of brotherly love, heroism, and spirit. Since the hurricanes, y’all have donated over $30,000 in relief funds for fly shops and guides, and many thousands more to others. You’ve collected tons of supplies and delivered them to people in need. You’ve donated trips, gear, and time that nobody can give back to you. Some of you may be tired of hearing about it, and I know many will refuse congratulations. Nevertheless, I want to tell you who benefitted from the fly shop and guide relief fund so that you might be able to know the size of the hands patting you on the back.

In Rosman, North Carolina, Jess Whitmire’s fly shop and taproom were severely damaged in the storm. In the days after, she and her guides were at the town hall coordinating supply deliveries, wellness checks, and offering shelter to people who spent weeks without power. They’re back on the water again, trying

to make up for lost time, and leading the way for other outfitters. Their Forks of the River Festival, a massive fundraising event for other outfitters on November 2, was a huge success.

In Elk Park, Greyson Stafford’s boat sat for weeks under four feet of silt in the shop garage because he has been running chainsaws, backhoes, supply trucks, and clean-up crews. He canceled the rest of his guide trips for the year and closed his fly shop, Deep South Co. Outfitters, to help full-time with the devastation in his county. We sent Greyson a check from our relief fund and linked him with folks who offered to repair or replace his boat for free.

In Canton, Doug McElvey canceled all his trips for the fall and turned his fly shop, Mountain Fly Outfitters (which just opened last year), into a community center where supplies were staged from the floor to the ceiling. Food trucks and bands have been playing nonstop for weeks to bring some business and joy back to the region. Luckily, they’ve recently been able to get a few folks out on their private water, which was destroyed and completely inaccessible during their prime time. Your relief money will help Doug keep his young but impactful business alive.

In Hendersonville, another young fly shop took a big hit. Hendersonville Outfitters somehow kept the lights on during the storm, and became a charging port for everyone in the community. In what should have been a peak sales month, Dave Bergman suffered big losses as a result of closures and outages, having to completely restock their private water. Hopefully, their second anniversary next

August will be sweeter thanks to your donations.

In Boone, the High Country Guides volunteered for weeks after the hurricane, canceling all their trips. They ran supplies, wellness checks, and rescue operations in multiple counties, leveraging their large network of clients and friends to make a big impact on their community. To cover some of their costs from the two weeks of cancellations after the storm, we sent them a check, too.

In Burnsville, North Carolina, Kyle Burnett was the first responder. Risking his own life to save his neighbors, he personally rescued dozens of people from Bowlens Creek, Pensacola, and Cat Tail. He coordinated an effective disaster response long before the helicopters ever showed up. He is still helping rebuild his neighbors’ homes while his peak guiding season at Southern Drifters floats away. You can donate to his GoFundMe at this link.

All this work to ease all this suffering has revived an old kind of Southern spirit I think—one that has always dwelled in hard places like the mountains. Eberhard Arnold called it “the ungrudging spirit of brotherliness in work. Work as spirit and spirit as work – that is the fundamental nature of the future order of peace…” The storms have passed, and election season is over. It’s Thanksgiving soon. The warring tribes will rest and feast together, but the future is work. Let’s keep painting our picture of peace together in the spirit of SCOF.

Community!

Hank

HELENE RELIEF FUNDS STILL

SHOP THE SCOF STORE

Thursdays Below the Dam

by Michael Garrigan

It only takes about a week into my summer vacation before I lose track of the days. Without a bell schedule to follow or bathroom passes to sign or essays to grade, the days simply, beautifully, naturally blend together into a series of slow mornings on the porch drinking coffee and long evenings sitting around a fire with whatever-I-want-to-do in between. Each day is a Saturday. Each day is a day I have to decide to not fish. Each day is a merging of hours spent doing whatever I want. Each day is a day I don’t have to bust kids for vaping in the bathroom. The only indicator I have of any sort of work week is when I ask a buddy to head to the river to fish or hang out and they, usually with a slight snide air of annoyance, remind me that they have to go to work that day. Because of this, I tend to spend a lot of time alone on the river kayaking or wet wading.

However, a couple of years ago, my buddy ended up with some extra time off after putting in a crazy amount of field work the previous fall. He’d text me the night before and ask if I wanted to meet at daybreak the next morning on the river to fish for smallies and carp. Yes, I always said, because of course I wanted to do that. It wasn’t until the fourth or fifth time that I realized it had become a bit of a routine, and I began to look forward to it every week through July and August. Unfortunately, years later and he’s still working a crazy amount of hours. But that means he can still take random

days off when work slows down in July and August. These off-the-cuff random Thursdays below the dam have become a yearly route for us and something I look forward to every summer. We quickly decided on Thursdays, because it’s a nice break in the work week for him and way easier to take off than a Friday or Monday. We’d never plan it more than a day out in advance because of, you know, life stuff like work and family. The dam is perfectly halfway between our houses and, since the mornings are the best, we’re usually off the water by lunch and have enough time to get back home to do any adulting things we need to take care of.

The Susquehanna River is big. It’s a slow meander chalked by a few dams that pool it into deep lakes. However, there are plenty of miles of islands stretched thin with silver maple, sycamore, and knotweed connected to each other by long ledges of rock and shallow riffles. By August, I can practically wade across the entire thing depending on where I access it. On particularly hot days, I love to kayak out to one of the islands and then wet wade to the point where the river is about to lift me off its bottom. However, down below the dam, the river is unique, it’s different, it changes dramatically. A big concrete wall does that to moving water. The dam’s release is a deep one-consonant-note offering that drowns out the entire world. Within that constant thrumming, if you listen closely, you can hear the river’s first language walking the slick quartz bones of stream bottom stained white with Egret guano. In order to get to the good fishing, we follow purple loosestrife knowing it

grows out of hardness, trying not to slip into still pools of cymbal-choked rainwater. We listen for sirens that blare when they’re about to release a bunch of water, hoping we have enough time to get back to the bank before the river rises too much and we’re stuck on an island for who-knowshow-long. We’re careful not to wade too far because the current is much deeper and faster in the main channel. Jon boats cruise up to fish the deep runs, but because of perfectly geologically placed ledges, they can’t get into the smaller backwater channels that we like to fish. The only way to get to where we fish is to rock hop three quarters of a mile across the river on slick diabase rock or kayak a few miles up from the nearest boat ramp against the current. It’s the perfect place that keeps most people away from itself.

Carp come easy down here. They find deep pockets of water eddying behind boulders where they lazily cruise in swirling current and inhale the crayfish that get tossed, flailing and confused, into their tiny worlds. Some days we just post up on a rock and take turns casting to carp with glass rods and whoop as loud as we can when we hook one as they bend our rods all the way down to the cork, knowing no one will hear our exclamations of joy over the traffic above us on the bridge. Carp usually make me feel like a fool on this river because they can easily scoot and dart off into the big, deep pools, but here, they make me feel like I actually know what I’m doing. Smallies find the sharp ledges that jagger into fast riffles, and lie in the deep water right below where they can munch on hellgrammites and minnows getting washed down from the dam. Some days we just chuck streamers upstream and jig them down through these pools and

land bass after bass and even sometimes channel catfish. Some days we just put on black poppers and wait for the violent inhales once the ripples of the cast fade. Some days we catch so many smallies that we lose count. Some days we don’t even begin to count.

Our walks back to the car are always during the hottest part of the day, when the sun is bleaching the hibiscus white with its glare. We don’t mind, though, because even as the river warms and we sweat through our hats, we stay buoyant with the morning’s easy joy. I’ve come to see these Thursdays below the dam as somewhat of a sacred time. When I’m stuck in the relentless routines of a school year in November and March and I haven’t fished or seen a buddy in a few weeks or months, I can think back on these moments as reminders that it’s always a good idea to reach out and find time to fish with friends. Not all fishing trips have to be long or in some epic place to be meaningful. Before these morning meetups, I was convinced that every fishing trip had to entail months of planning or long text threads about which river to fish and when to meet up and which flies we should bring. Sometimes you just have to find a piece of water halfway between each other and a few hours you both have off and fish with someone who reminds you why you started doing this thing in the first place.

East Tennessee's Lesson in Reality

by Shane Behler

It was a wedding in Bristol, Tennessee, that prompted the trip. I had heard tales about East Tennessee’s famous tailwaters, the South Holston and Watauga rivers, for years. I’d listen enraptured when other anglers delved into wistful stories about the rivers and the bruising browns and acrobatic rainbows that called them home, and I knew that one day I would have to experience East Tennessee’s trout fishing for myself.

The wedding finally provided the perfect excuse to do so.

At the time, I was in a blissful period of unemployment, with one job just behind me and another slated to start in two months. Bearing my employment status in mind, I booked a campground for 14 dollars a night and drove up to Tennessee on a Tuesday morning with four days to spare before the wedding.

The first thing I learned upon arriving was the fishing is completely and utterly subject to the whims of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the bureaucratic deity charged with regulating dam releases. When the TVA is generating power, the South Holston and Watauga brim to the lips of their banks, and wade fishermen such as myself scatter from the heightened flows like coveys of flushed quail. Generation schedules are posted only a day or so in advance—and can change at any time—making it impossible to form concrete plans. When I showed up on Tuesday, the TVA was generating all day on the South Holston. Foolishly, I gave it a whirl anyway, having come all this way

and eager, almost desperate, to get in the water.

High expectations lead to poor decisions. I took one step off the bank and was nearly swept away. I scuttled back to shore and safety and brought my expectations earthward. It was a half-hour drive south to the Watauga.

Traversing the country roads that parallel the river, I could tell that the Watauga, too, was high, but it looked a little more manageable than the South Holston. I pulled off the road at a bridge that spanned the river as it swept into a quarter mile-long pool. Hayfields covered the left bank, and a wooded bluff stood guard over the right. The sweet smell of cow manure drifted on the breeze. Clouds tumbled over the surrounding mountains, and a light rain began to fall. A pretty scene.

I walked along the bank, staring into the pool’s dark waters, wondering at the secret lives of the trout that I hoped resided in the inky depths. No fish were rising to provide any clues. I continued down to the pool’s tail out, where the river braided itself through channels and grasscovered islands. I tied on a stonefly nymph with a tungsten bead the size of a pearl and caught a foot-long wild brown trout on my third cast. Expectations inflated once more.

For an hour-and-a-half, I picked apart the seams and slicks of those riffles and runs and could not repeat my initial success. I went back up to the pool, thinking I’d swing a streamer through the current at the pool’s head, when a single rise broke the soft water’s glassy surface. The trout sucked down a lone caddis on the periphery of my casting range with an assurance that could only mean a sizeable

fish. I immediately lengthened my tippet and tied on my favorite caddis pattern. The cast was long and the drift tough, but I gave it my best shot. The first caddis pattern and four subsequent ones failed to raise the trout again. Or maybe it was just my poor drifts. Regardless, another fishless hour slipped away.

By now, the long shadows of evening cloaked the river. A few smaller fish had started to rise to the scattering of caddisflies trickling off the water. I managed to catch several of these palmsized rainbows while biding my time in the hope that a more intense hatch would ride the wisps of daylight, bringing the larger trout to the surface with it. But those hopes went unrealized. Except for the few caddisflies, the insects continued their cryptic underwater lives.

I pulled myself from the river under a gathering darkness, still desiring something from it.

Over the next two days, rain was persistent and sunshine rare. I bounced between the two tailwaters at the mercy of East Tennessee’s demand for electricity. The younger class of the trout population proved far more gullible than the older, bigger fish. But there was evidence of the latter’s existence: that first rise on the Watauga, another singular rise on the South Holston that displaced an improbable amount of water, and a long, wide figure that darted away from my wading boots. I initially thought that fish was a striped bass that had run upriver until it turned in the current and revealed its golden flank. I wanted to catch one of those big trout. Badly.

The fishing would have been amazing if I had been blue lining the

many creeks tumbling off the mountains. But when catching eight-inch trout from waters prowled by others that could easily eat a fish that size, with every hookset that doesn’t progress into heavy, slashing headshakes, disappointment comes knocking.

By Friday, I was beginning to think the mildewy smell of wet gear had impregnated my car’s interior. I feared that my tuxedo (woefully stuffed into a duffle bag tucked behind the passenger seat) would absorb the atrocious odor, and that I’d be even more of a wretched presence on the dance floor than usual come Saturday. But this was of minor importance as I left the campground that morning. The TVA had granted a three-hour window without power generation on the South Holston. I had to meet the others in the wedding party that afternoon. The pressure to connect with one of those big trout had increased. I hiked down the gravel trail along the South Holston’s bank for the final time as breaths of chilled fog spilled off the river. I shivered through the haze and stepped into the head of a run.

The South Holston is known for its summer-long sulphur hatches. As delicate as jasmine flowers, these yellow mayflies blossom from trout streams on warm evenings. In the best of times, their hatch can be a nightly occurrence you can set your watch to. However, in artificially cooled tailwaters such as the South Holston and Watauga, the hatch can last from sunup to sundown, providing day-long dry fly fishing opportunities—a trout fisherman’s nirvana. This is what I had been hoping for out of East Tennessee.

Maybe it’s a trick of evolution—bright colors contrast on dark, rainy days— or maybe it’s just undignified for such a

creature to show itself in dreary weather. Whatever the case, the only sulphurs I had seen so far on my trip, which was timed with what was supposed to be the peak of their emergence, were forlorn singles that drifted by alone, looking sad and lost.

But now, as I peered through the river fog, I could see rises dimpling the surface. No, it wasn’t sulphurs that the

fish were feeding on—that would have been just too perfect—but minute, black caddisflies. I dug through my fly box and found a somewhat adequate-looking imitation, tied it on, and convinced a few small brown trout to take the fly.

I was starting to feel pretty good, having matched the hatch, catching these inexperienced little browns. I momentarily

forgot about my vain desire to trick, hook, and land a big trout. Isn’t it a funny thing that we measure our angling selves by our ability to do this? What changes about a trout when it grows beyond that arbitrary 20-inch mark? Maybe it becomes a little more selective, more challenging to catch, and sure, bigger fish fight harder. But with every “big” trout I’ve caught, the fight itself is really more harrowing than anything, fraught with the constant worry of losing the fish and the existential dread that inevitably follows such a loss. Maybe big trout aren’t all they are cracked up to be. And then one rose along the far bank, exposing the full glory of its length as it sipped down a caddis, and all those mollifying thoughts about big trout being

overrated vanished as the rise rings lapped into the current. I waded past the small trout I had been casting to and perched myself on a shelf of bedrock in the center of the river, all the while watching the water where the trout had finally shown itself. For five, ten minutes, I waited, unmoving, trying to will the fish to rise again. It didn’t, so I cast anyway. I changed flies and casted again. And again. And again.

LYDIA IS COOL. LYDIA WEARS SCOF MERCH. BE LIKE LYDIA.

photo by alan broyhill

HOW TO GYOTAKU

PRESENTED BY IKO PRINTS

Conservati

ion Corner

One Flat at a Time

By Dr. Professor Mike

Anyone who has fished in popular angling destinations for more than a few years has no doubt noticed changes. Some of these changes are “normal” and even seasonal such as storm damage in the tropics. Others, such as rampant development, are not so normal. COVID-19 gave a brief reprieve from the impacts of new development and fishing pressure, but that was a brief reprieve. Of course, our industry needs growth to sustain our favorite guides, fly shops, lodges, and magazines, but it’s a tricky balance. How much growth is necessary to sustain our economy without destroying the very resources we value? It’s a difficult equation to solve. And we, the fly angling community, aren’t the only ones who use and visit flats, reefs, beaches, mangroves, rivers, and lakes.

Since 1992, I’ve spent most of my fly fishing budget and time in Belize. I started angling around Ambergris Caye, the past and present center of the fly fishing industry in the country. Needless to say, I’ve seen some changes. There are more lodges and guides on Ambergris Caye than any other region in Belize. When I first arrived in San Pedro (the main town on the Caye), there were no cars and no paved roads, only sand. Other parts of the small country have seen less intense development, but change related to tourism growth has impacted the entire country.

It’s easy to get discouraged when one sees a newly dredged area for a hotel or the line of huge cruise ships waiting to unload their passengers, but this pressure has also galvanized the fly

angling community into action. In fact, I’d argue there are few if any other countries where the fly angling community acts as such a powerful watchdog group as in Belize. This advocacy is the result of a combination of committed guides and lodges, with support from Bonefish Tarpon Trust. Fortunately, much of Belize’s best flats angling is housed in any number of marine reserves, so there is a conservation infrastructure, but that doesn’t eliminate all development (some of which is based on vague land leases and outright payoffs to the right officials). But again, given the economic importance of flats angling, questionable development is a tough secret to keep.

One such example was a proposed development on Angelfish Caye in Belize, also known as Will Bauer Flat, found inside the South Water Marine Reserve. This project was fought tooth and nail by the Belize Flats Fishery Association, a fly fishing and conservation advocacy group made up largely of fly fishing guides. Although the proposed development dubbed itself an eco-resort and was relatively small, the impact on the overall flats ecosystem, and its bonefish population specifically, would have been devastating as a result of dredging and boat traffic. Fortunately, through direct action and even confrontation, which generated a great deal of media attention and one arrest (Eworth Garbutt, the group’s president), the proposed development was killed, and the caye and its flats remain intact.

This victory for the fly fishing community in Belize, while geographically small, does have larger ripple effects. Belize isn’t alone, of course, in terms of development pressure. The Yucatan,

Bahamas, Florida, and similar tourist destinations all face incredible pressure. But as was demonstrated in this case, a unified industry can influence development trajectories (i.e. kill proposed projects) to protect the resource. Sure, it’s not a large proportion of the total habitat, but in the face of intense national development pressure in Belize and elsewhere, every single flat is incredibly valuable and irreplaceable. Successful and sustainable fisheries conservation doesn’t have to be at the national scale, it can also start at the very local level – one flat at a time.

BENCH PRESS

Jiggy Shrimp

by Joey Presson

WHAT U NEED

• Finn coon

• Small dumbbell eyes

• Ahrex size 4 jig hook

• Ep Foxy brush

• Ep .5 in tarantula brush

• Crystal flash

• Mono shrimp eyes

• Sili legs

• All colors optional!

step by step

Step 1: make a thread base to lay down material.

Step 2: tie in dumbbell eyes at the bend of the hook eye and bring thread back just past the hook point.

Step 3: pull a small clump of Finn coon and pluck the longer gaurd hairs out before tying in and removing the excess fibers from the tie in point.

Step 4: tie in mono shrimp eyes.

Step 5: tie in a strand of crystal flash doubled over and trim just a bit longer than the length of the Finn coon.

Step 6: tie in foxy brush and wrap back up to the hook point and secure. Use finger brush to get brush loose and trim to clean it up.

Step 7: add two rubber legs doubled over so there’s two legs on each side of the hook shank.

Step 8: tie in tarantula brush and wrap half way up the rest of the hook shank. Secure with enough brush left over to finish wrapping the rest of the hook.

Step9: add a singular sili leg to go crossways out of the shrimp body.

Step 10: wrap tarantula brush the rest of the way up the shank and secure behind lead eyes

Step 11: trim tarantula brush to clean up the fly a little bit and trim the legs to all matching length. Add weed guard (optional) and seal head with UV resin