CHAOS BETTER

2. GROWTH

We are called to spiritual freedom by which we surrender fretfulness and anxiety in order to be available to God in the present moment. - SSJE Rule of Life

in this issue Awake focal practice as a path Patience and the crucible of life Know Limits Anxiety opening up to God The Brakes learning

to

what

hard:

very real chaos

us,

chaos that challenges us can become

growth. about the series Summer 2024 Volume 50 • Number 3 SSJE.org/cowley GROWTH cover CHAOS

a circle of seats, welcoming guests

a make-shift altar. When we

the chances

changes of life, in all their chaos

complexity, we can find the Holy One

our midst.

confict resolution On The Hard Road CHAOS BETTER tries

sit with

is

those places where we are struggling, whether on a personal, interpersonal, or global level. It recognizes and offers ways to navigate the

within

between us, and around us – and it asks how the very

the place for our most profound

BETTER A fallen tree becomes

and Brothers into fellowship around

embrace

and

and

in

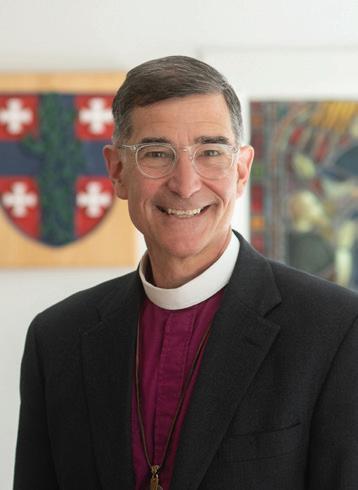

My dear friends,

To be alive in this planetary moment is to be subject, on a daily basis, to grinding and relentless pressures. Some are tied to historic shifts of such magnitude that we feel helpless to effect change. Some confront us hourly with reminders of the fragility and complexity of living in our own skin.

But in reading my Brothers’ words in this issue of Cowley, I am reminded of the ways that frm (even painful) pressure can also form, reform, mend, and heal. The frm pressure of the potter squeezes, compresses, and hollows. In massage, physical therapy, and other healing arts, the practitioner finds her way to the source of the patient’s ailment by pressing, pushing, and prodding the places that hurt most. Certain kinds of pressure applied consistently, lovingly, over time, change us for the good.

This is the role of pressure in the spiritual life. The Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner wrote: “We are pressured from within to become more. The Spirit invites us

to evolve; to respond graciously to the changes that God may be inviting us to embrace.”

In this vision, the Spirit is intimately present to who and what we are in this moment. At the same time, the Spirit exerts a dynamic force – a pressure – urging each creature forward into God’s future, a further unfolding of its purpose. Unlike the day-to-day economic or social pressures that bear down upon us from the world, or even the internal pressures of our own psyche, the pressure exerted upon us by the Holy Spirit is always creative, generative, and life-giving beyond what we can anticipate or imagine.

St. Gregory of Nyssa, a bishop and theologian of the fourth century, was captivated by the question of what drives this forward momentum in the spiritual life. Gregory uses the word progress, epektasis in Greek, in a very particular way. He takes his cue from Phillipians: “I do not consider that I have made it my own. But one thing I do: forgetting what lies behind and straining

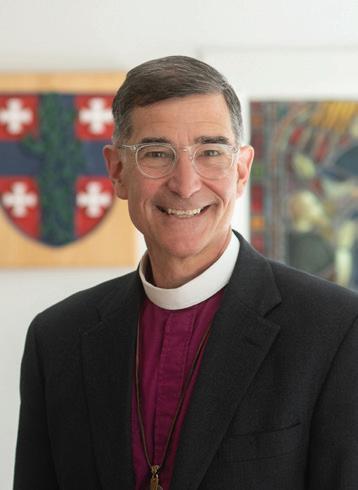

A Letter from the Deputy Superior

forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus.” For Gregory, this “straining forward” is our dynamic response to the Spirit’s pressure from within.

Gregory’s vision didn’t stop with earthly life. He envisioned an eternity in which the soul will always keep searching for greater fulfillment of its desire. Beyond the restless dissatisfaction that often propels our earthly desires, the soul’s desire under the Spirit’s creative pressure is transformed. At each new moment that it grasps its desire, the soul discovers its desire has expanded to let in a further vista of God’s breathtaking beauty. Our capacity to evolve – to respond to the invitation to change – becomes as infnite as the goodness, truth, and beauty of God are infnite.

We are pressured from within to become more – but we need not become perfect. The unfolding of our purpose is never fnal. God wants more and more of us, and in

A Letter from the Editor

You’ve seen arches. There are arches in SSJE’s logo, on this magazine. Strongbuilt structures of support, ingenious ancient developments of architecture and engineering, classic, enduring, open. But the working principle of an arch isn’t as still as it appears. Each stone comprising the curve of the arch is wedged against its fellow stones, exerting pressure down from gravity and out toward its neighbors. There’s tension, there’s friction, there’s force. The archway, the building, the order, isn’t a static accomplishment of the past; it’s happening now. Real pressure and strain aren’t impediments to the strength of the arch, they’re necessary components.

This issue of Cowley is arranged around the idea that, as chaos unfolds, as we fnd ourselves in the midst of diffculty, we are pushed into action, some sort of response. Maybe it’s small, maybe it’s revolutionary, but as we encounter disorder, as we feel embattled by concerns around us, that very diffculty is the material out of which we build something new, something sturdy and lasting. Brothers in this issue have written in various ways, not on how they’ve achieved perfect, uneventful calm, but of how they’ve built, and you may build, new order, structure, meaning, and growth out of the struggles of life. As you read and pray with us in this issue, I encourage you to refect on your own struggles, not as failings or obstacles, but as the resources God has given you to grow and to build something new.

With these pages, we invite you to:

Reflect on your own struggles, not as failings or obstacles, but as the resources God has given you, to grow and to build something new.

Awake

Focal Practice as a Path

Keith Nelson, SSJE

Awake, awake to love and work! The lark is in the sky; The felds are wet with diamond dew; The worlds awake to cry Their blessings on the Lord of life, As He goes meekly by.

Singing these verses in our monastic service of morning prayer – in an indoor chapel, from a printed page – evokes memory, imagination, and desire ( “Not Here for High and Holy Things,” words by George Anketel Studdert-Kennedy). I remember the many early morning walks I have taken; I imagine the worlds around me on every side full of crawling, flying, burrowing creatures, continually drawn into being by the breath of their Maker; I yearn for yet further, deeper relationship with God’s world as its beings sing their million-throated witness to Life in its fullness.

But when the hem of my habit is drenched with the same diamond dew; when I have responded to the relentless song of the first robin by rousing myself out into the enfolding half-light of dawn; when my own ears have heard the blessings cawed and warbled into the clinging mist before the work of human worship has even begun; it is then that I know, by the Creator’s grace, the heart of the hymn of creation. My boots flecked with grass, my beard slick with the fine spring rain, singing a hymn becomes more than an aid to memory, imagination, or desire. My mouth is full of praise that has become my own because it has also become the world’s praise resounding through my voice, returning to its Source.

Praying morning prayer daily; singing a familiar hymn with devotion; getting out of bed because that first enthusiastic robin is singing her heart out; lingering to witness the primeval moment the sun breaks the tree line and the world is, once more, gifted with light…

Even if our own list would differ substantially, we know intuitively that these activities share an underlying kinship.

Though small in themselves, they orient us toward the focal concerns of our lives: the things that matter most and give meaning and value to all else. Giving ourselves to their patterned observance, we give ourselves to God: the generous source and grateful recipient of our prayers, praise, attention, and wonder. They are, in the phrase of Albert Borgmann, focal practices. 1

A focal practice is an engagement, a habit, an activity that we take up frequently – daily or at least weekly. It requires attention, effort, and skill honed over time. This combination of qualities means it may at times feel burdensome, a task that demands more of us than we can summon when our schedules demand convenience or our hungers urge us to instant gratification. But when, with patient fidelity and love, we take up the arduous task, it yields a deep satisfaction and fulfillment of purpose that is often hard to describe. Traditional spiritual disciplines such as scripture study, contemplative prayer, and liturgical worship clearly form a time-tested repertoire of focal practices. But many other activities fulfill the same purpose and can easily become prayer with the right inward orientation: playing an instrument; tending a fire; baking bread; learning the birds in our ecosystem by sight and sound. Indeed, these were the daily practices of premodern humanity, among whom the classic spiritual disciplines first blossomed. To live on this earth with a purpose that rendered the struggle and pain worthwhile meant ordering one’s life around focal things. Focal practices safeguarded the centrality of those things.

Borgmann is a philosopher of technology and a Christian. His notion of focal practices is set within a larger project: advancing a vision of responsible engagement with technology in ways more closely aligned with matters of ultimate concern.

I have found the notion of focal practices helpful on many levels. The term accurately describes most of the activities embedded in the rhythms of monastic life. These include the Daily Office and Eucharist; monastic customs and spirituality around the labor of our hands; our practices of eating and table fellowship; our traditions of hospitality; our disciplines of learning and study; our cultivation of skills for ministry such as preaching and spiritual direction; and the vast treasury of practices

1 Borgmann’s classic text is Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life: A Philosophical Inquiry.

that enrich our personal prayer. We have focal practices for almost every aspect of life!

But we – like everyone in contemporary North American society – are just as susceptible to what our Rule calls “the din of noise and the whirl of preoccupation” that come with a technology-saturated culture.

During a stretch of bleak, gray weather in February when the sun hasn’t appeared for days; when I respond to the chapel bell with dogged obedience rather than light-footed joy; when the preaching of God’s word tastes uninspired and flavorless in my mouth; when I feel lonely or unloved, threadbare or tested by the vows I professed with such ardor; then it is easy to find me checking my email for the fifteenth time in a single day; watching a third or fourth or eighth consecutive YouTube video about the absolute best method to free-range chickens; wondering with needless anxiety why a friend hasn’t texted me; or slogging away at a spreadsheet on the Sabbath. Irritable, listless, estranged from my body, the moment of awareness creeps upon me: This is not Life.

It is then that the creator Spirit – through my focal practices – drives me out into the wilderness, or just the nearest city park or stretch of riverbank, to rediscover my human creaturehood in a world of things. I stare down my own inertia and acedia; I muster patient fidelity and love. I ask for help. I take up the arduous but Life-bestowing task. By the Spirit’s grace I engage again with Life. It’s not a magic recipe. I don’t always respond as swiftly or wholeheartedly as I ought. No matter – the God who gives Life far more than I desire it always stands at the ready with another opportunity to return.

Though I’m a monk, I am learning (like all of us) that if I am to be critically engaged with technology, I must hold its use in proportion alongside the focal practices by which God brings me back to Life.

Irritable, listless, estranged from my body, the moment of awareness creeps upon me: This is not Life.

The Baptism of Our Lord, depicted in an icon from Agape Farm.

The Baptism of Our Lord, depicted in an icon from Agape Farm.

What I have found most enriching about Borgmann’s work is the idea that critical engagement with technology, as Christians, compels us to take up counterpractices. These weave us back into right and balanced relationships with material things in their irreducible goodness. Devices are not the enemy. They are simply so powerful, and their means of operating upon us so advanced, that we require a highly intentional context of counterpractices to flourish if we are to pursue the good life, and the godly life, in their midst.

While all focal practices engage us intimately with a world of things, I want to share just one that has been particularly instrumental in my own life of loving relationship and reciprocity with creation. If creation is the “material expression of God’s love,” this has been a counterpractice safeguarding my love for creation as an ultimate concern, in a world that routinely reduces creation to inert matter or expendable resources.2

There is a stream that meanders its way through our western woods on the land surrounding Emery House. In one place not far from its union with the Merrimack, the water reliably tumbles over a series of rocks. For a season I made it my discipline to visit this place daily, and its presence drew from me a focal practice that blossomed into an astonishing, intimate relationship. I visited shortly after sunrise. I let the sound of the stream enter me, tumble over the rocks of my thoughts, saturate my intentions. It took time and patience, but I came to feel that the stream herself was teaching me what to do, how to be, in a relationship of mutual presence. When I felt the stream within me, I gently began to shake a rattle. For me this established a connection in the language of sound with the gurgling of the water, the song of the birds, and the rays of morning sunlight. The stream began to sing, or rather I began to hear her song, and this hearing gave me a song to sing in return. Through the harmony of these songs, my song and hers, it was as though I began to hear the eternal Song – the Word – sounding forth from that sacred niche of God’s creation (John 1:1-4). The song of the Creator sings with the voice of every creature. That song is always unfolding – it was long before me, and will be long after me – the song by which the cosmos is sustained. In farewell, I would cross the stream, dip my hands in her waters, and cross myself, as I would with water from a baptismal font.

While going about my day at Emery House, I would often think of the stream, continually flowing out there in the western woods, no matter what I was up to. The stream flowing in the darkness while I slept and dreamt or lay awake sleepless. The stream flowing in the morning and at sunset while I chanted in chapel. The stream praying without ceasing, inspiring me to make my own attempt to do the same. It is a sacrament of the God who is “living water, gushing up to eternal life” and the “river of life” flowing out from the heart of God (John 4:14; Revelation 22:12). All this may sound like the work of a wistful, overactive imagination,

2 The material expression of God’s love” is theologian Norman Wirzba’s concise defnition of creation.

or perhaps a metaphor run riot, overflowing the banks of reason. But I promise you it is real – at least as real as the words on this printed page or screen. I have come to believe that a stream, this stream, can desire my admiration, my song of love in response to its own sounding song. This reciprocity completes something in me. It is a part of how I am being saved, how I am being made whole. I believe this reciprocity completes something in the work of co-creation, to which Christ calls us to participate. Just as it is part of how I am being made whole, I believe it also is a small part of how creation is being made whole, gathered into the heart of God’s mysterious purposes.

Our ancestors in Christ spontaneously and intuitively cultivated relationships of mutual presence with wild creatures. Countless stories of the saints show us a pattern. It unfolds in the places they called home: the deserts and caves of ancient Syria-Palestine; along the harsh, seaside cliffs of Ireland; and deep in the forests of Russia. In the tales left by their disciples, we encounter servants of Christ befriending lions and jackals, blackbirds and hares, bears and birch trees. Many were monastics, souls worn smooth as river rocks by the ebb and flow of what I would call their focal practices. But this pattern is also intrinsic to the worldview of the Biblical authors. The psalmist cries, “Let the sea make a noise and all that is in it, the lands and those who dwell therein” and “Let the rivers clap their hands and let the hills ring out with joy before the Lord, when he comes to judge the earth” (Psalm 98: 8-9). Jesus urges us: Consider the birds of the air. Consider the flowers of the field. Listen , he urges the Pharisees: if my human followers were silent, the stones themselves would shout (Luke 12:24; Luke 12:27; Luke 19:40). This kind of consideration, this kind of listening, is the fruit of attention and devotion lovingly offered – moment by moment, day after day. Lifetime after lifetime, these have been the habits of the saints. In generous hands, they hold them out to us, their heirs in Christ’s Body.

In other words: this stuff isn’t just for monks wandering around in the woods, or for nuns in caves. It’s for all of us. However distant or disconnected our lives may feel from the restorative power of God’s creation, Life is as near to us as the closest patch of clover and its diamond dew under our bare feet. Life is as near to us as the flour, water, and yeast that yields its supple heft to the pressure of our palms, longing to become bread. Life is as near to us as the sweat that spills from pores and the breath that heaves in lungs as we push through that final turn in the trail toward home.

When we commit to God as our ultimate concern, a deep satisfaction and fulfillment of purpose awaits us. A world of things becomes a cast of collaborators in God’s breathtaking design. It takes practice. But through it, we come to know a foretaste of life that is Life indeed.

Soul Friend (adapted from the Book of Kells, c. 800 A.D.)

Created using plant-based inks produced at Emery House (2024) Keith Nelson, SSJE

atience

the goodness in waiting.

P

and the crucible of life Find

Curtis Almquist, SSJE

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “patience” as “the calm abiding, a quiet and self-possessed waiting for something”; however the etymology hints at the normal context, which is often very difficult. “Patience” comes from the Latin patientia, which is a “quality of suffering” – suffering with calmness and endurance, what the scriptures call “long-suffering.” And suffering you often are when you are forced to relinquish your desires, or when you are left to wait without recourse. Patience is oftentimes not pretty and may feel vapid; sometimes there is a storm before the calm. It is one thing to wait in eagerness for something delightful we anticipate will unfold. It is another thing when we must be a patient patient because we are not in control over suffering – our own suffering or that of someone else whom we carry in our heart.

Here is a disclaimer. Sometimes we should not be patient. Some things we encounter in life are urgent, and we must act now.

But in the normal gestation of life, we must often wait. Without our learning patience, we will miss being present to a great deal of life. Life entails so much waiting. When the answer is not forthcoming, when something is not being resolved, when the door is not being opened, when someone is not acquiescing, when we have lost any sense of controlling some circumstance, we may experience a certain anguish or anger. To experience the fullness of our life, we must learn to wait well. Saint Francis de Sales advises, “What we need is a cup of understanding, a barrel of love, and an ocean of patience.” 1 Patience is a quality of waiting.

Patience does not come easily to most of us, for several reasons. Our ego, how many of us grandstand our own importance on the stage of life, can be a great impediment to patience. What I want, and when seems right, when I am entitled. It took me many years to distinguish the adoring love I experienced amongst my own family-of-origin from

1 Saint Francis de Sales, O.M. (1567-1622) was Bishop of Geneva.

my true place in the world. For some of us, the context of learning about patience has very little to do with us, personally, and everything to do with others. They have their place, their needs, their hopes and desires. I must wait my turn. Sometimes there are many people in line ahead of me. The Jesuit priest, Anthony de Mello, describes the necessary shearing of the ego that can happen as we grow older: “Before I was twenty, I never worried about what other people thought of me. But after I was twenty I worried endlessly about all the impressions I made and how people were evaluating me. Only sometime after turning fifty did I realize that they hardly ever thought about me at all.” The stage on which many of us learn about patience is discovering we are seldom THE STAR and more often the extra. We have an important and unique part in life, but so does everyone else. We must learn, listen, and become patient in the waiting.

Having to wait may prove to be a crucible to your soul, burning away what does not belong. You will not always get what you think you want in life. Jesus describes himself as “the gate” and “the door,” and sometimes he bars the way (John 10:1-9). As I reflect back on my own life, I teem with relief and gratitude for so many things I thought I wanted but was denied. (In my younger years I was nicknamed “Curtis Armtwist.”) I realize now that had this-and-that or such-and-such have happened, I would have ended up in a very different place.

Sometimes, by God’s grace, we are denied our dearest hopes. T. S. Eliot writes of how we often want what proves to be the wrong things, and how “the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting. Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought: so the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.”2 Patience can even mean learning to be grateful for the doors that did not open before you, and, therefore, the new direction in which you turned which has brought you to where you are.

2 T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) in Four Quartets: East Coker, III, 11. 23-8.

When you are in the dark, God is not in the dark.

Finding the goodness in waiting, in slowness, is quite countercultural; however our having to wait may turn out to be a great kindness of God towards us. The scriptures consistently refer to us as “children of God” (not “adults of God”). Children are not developmentally ready to know everything at once. There is a progression in our capacity to know, which God knows. The apostle Peter awakened to this realization. He writes, “Beloved, while you are waiting, be at peace… and regard the patience of our Lord as salvation” (2 Peter 3:9, 15). Our experience of having to wait may, in actuality, be God’s experience of waiting on us until we are ready for more. Take heart. Simone Weil, the great French spiritual

writer and political activist of the 1940s, writes how “waiting patiently in expectation is the foundation of the spiritual life.”3

Here’s one more benefit. Adding the phrase “patient waiting” to your soul’s vocabulary may be a helpful intervention to the onset of anxiety. There is a freedom that can be gleaned in your being powerless to know the future. God knows. God knows what you do not know, and God knows that you do not know. In the beginning of creation, God creates an interchange of light and darkness to fill each of our days. It is as true for the sky as it is for the soul. We can only bear so much light. Light can be as blinding as darkness. The eyes of your heart will be enlightened with as much light as you can bear.4 When you are in the dark, God is not in the dark. The psalmist writes of God: “Darkness is not dark to you; the night is as bright as the day; darkness and light to you are both alike.”5 If you are in the dark about something, your waiting invites patience for the dawning. The dawn will come in the fullness of time.

Waiting patiently is not a limp submission. Waiting patiently is an active presumption that God is at work in our life in ways beyond what we could ask or imagine.6 When you have no choice but to wait, open your eyes and open your heart to what you otherwise might have missed. You do not have what you are waiting for – what is next – but you do have what is now. Don’t cut in line. Be present to what is now, even if it is full of struggle. You will find the companionship of God’s real presence in the waiting, which is the fruit of patience.

I waited patiently upon the LORD; he stooped to me and heard my cry. He lifted me out of the desolate pit, out of the mire and clay; he set my feet upon a high cliff and made my footing sure.

– Psalm 40:1-2

3 Simone Weil (1909-1943), whom T.S. Eliot described as “a woman of a kind of genius akin to that of the saints.”

4 “The eyes of your heart,” an evocative phrase of Saint Paul in Ephesians 1:18

5 Psalm 139:11. See also 1 John 1:5

6 See Ephesians 3:20-21

“As someone with a neurodivergent condition, I often find it challenging to quiet my mind for prayer. A strategy that has worked well for me during meetings is ‘doodling.’ Creating doodle art not only quiets my mind but also helps me focus and retain information. I’ve discovered that this technique is equally effective for centering prayer and meditation. Here is an example of my prayer in doodles.”

Ink (2024) – Jim Woodrum, SSJE

catchthelife.org

If you’re curious and you think there’s a vocation toward which God is leading you, nudging you, encouraging you and pushing you, then a weekend or a week, or even a year out of your life, is worth it to check it out.

– James

Know Limits

Lain Wilson, SSJE

Lain Wilson, SSJE

Heat radiated off the pavement as I cycled past tree-dotted lawns. The temperature had already reached ninety degrees, and it was still climbing. My breathing was labored, tunnel vision had set in, and my thoughts were focused on just getting around one more bend in the road. One hundred more feet. One more rotation of the pedals.

This was just outside of Belmont, in northeast Mississippi, during a heat wave in August 2021. I was three days into a bike trip south on the Natchez Trace Parkway when I hit my limit.

I mean this in a very literal way. I could not make myself move forward. You may not have had a physical experience like this, but I imagine that you will have experienced something similar in another part of your life. Commitments piling up with not enough hours in the day to address them, no matter how hard you work. The red numbers staring at you on your budget sheet, with no possible way to close the financial gap. Demands on your time and attention from family or friends that you emotionally cannot meet. Your story is your own, but I would bet that something like this is, or has been, a part of it.

For myself, I’m not sure that I had felt something like this before. I had run races and rowed competitively for years, and I had always felt that I was putting myself out there fully, emptying the tank in the final stretch. I had always thought that I had nothing more to give, nothing more to offer. That day in Belmont showed how wrong I was. That day stripped away the false pride of accomplishment and self-sufficiency. It uncovered

my underlying fear of failure, of weakness, of admitting defeat. Who was I, if I had to ask for help, if I knocked on the door for a glass of water, if I called for a ride to our rest stop? Who was I, if I couldn’t do what I set out to do?

We all face and experience limitations in different ways. They can be temporary walls to be overcome or fixed boundaries, narrowing and constraining the possible. They can be imposed upon us unwillingly or chosen by us as part of our discipline or vocation. In each case, though, our limitations challenge us to discover and to explore the world that they define. Although they may cloud our vision of the boundless horizon, our limitations open new opportunities for setting our sights before us. They invite us, in the words of poet Waldo Williams, to inhabit “a broad hall found between narrow walls.”1

Two of my favorite stories about what opportunities limits afford come from the Hebrew Bible, back-to-back in the book of Exodus (Exodus 17:8-13 and 18:13-27). First we read how Moses has led the Israelites out of Egypt. They have crossed through the Red Sea, into the lands of a neighboring tribe called Amalek, which has attacked the Israelites at Rephidim. Exodus tells us that when Moses holds up the staff of God in his hand during the battle, the Israelites prevail; when his arms lower, Amalek prevails. During the fighting, Moses’ arms grow tired. Hitting his limit, he requires the help of others, Aaron and Hur, who hold his hands steady through the rest of the day.

Yet even with this support – and this victory – Moses’ struggles are far from over. The Israelites don’t just encounter hostility from outside but quarrel among themselves as well. Immediately following the victory at Rephidim, Moses’ father-in-law Jethro visits the camp and sees Moses’s unceasing labors as judge over his people. “Why do you sit alone,” Jethro asks, “while all the people stand around you from morning until evening? . . . What you are doing is not good. You will surely wear yourself out. . . . For the task is too heavy for you; you cannot do it alone.”

In each of these stories, we witness Moses coming up against his own limits – physical for sure, and probably also emotional and rational. He has always had God with him – speaking and working through him. But in the face of his own frail humanity – the weight of his arms, the feeling of responsibility, the need for rest – he must learn to trust in the strength of others, on the small, quarrelsome people for whom he has risked his life.

This lesson is a constant struggle for me. Being upheld and supported by others can feel, in an incredibly irrational way, like cheating. I can tend to feel that I’ve gotten to where I am through my own efforts, by the sweat of my brow, and that what I am given to do is mine to do. I

1 From his poem “Pa Beth yw Dyn?” (What is man?), translated by Rowan Williams in his collection The Other Mountain (Carcanet, 2014).

am responsible for this task, and I’ll do it. In the name of responsibility, I perpetuate the sins of pride and self-sufficiency – but this self-sufficiency ends up meaning that I’ve isolated myself. When I imagine the two stories with Moses, I wonder whether I would’ve accepted help, or if my own sense of pride would have led my arms to fall and my army to be defeated. I wonder whether I would’ve run myself ragged trying to mediate disputes, sure that this was my job to do.

I’m sure you have a version of this that is your own, that accounts for your own values and personality and circumstances. Maybe pride isn’t your problem, but fear, despair, anger, resentment, helplessness, overwhelm . . . the list goes on. Just as each of us faces a story of limitations that is uniquely ours, so too is our response.

What emotions do you notice when you reflect on your own limitations? How do you find yourself responding?

Being made aware of our limitations can invite an awareness of the darker sides of our nature. My pride and fear urge me to avoid or to paper over my limitations. But once I realize these limitations will always be with me – and that, like Moses, my failure to acknowledge them doesn’t just affect me, but also those around me – I can begin to understand my limited life in a new way.

Take the vows that constrain the monastic way of life. Choosing – even embracing – limitation in the form of vows of poverty, celibacy, and obedience is, for me, about reckoning with those darker urges that press me to hide away my weakness and vulnerability. The vows challenge me to bring all this into the light and, in doing so, reflect that light back onto other areas of my life. They dare me to embrace the freedom of a limited life.

Religious vows are one radical way of embracing this freedom. You may have a different way, but each path is about living our lives intentionally with the committed belief that what limits us can become a source of hope and joy. That we are able to live more deeply, more richly, more

mindfully when we shut down some of the infinite array of options and choose to live a more limited life; when we live in a “broad hall found between narrow walls.”

Not all of us, of course, get to choose our limitations. Not all of us get to establish our own boundaries. Many of us face clouded horizons and narrowed pathways due to forces beyond our control: race, class, poverty, ability. It can be difficult, even insulting, to be told to embrace that limitation. I get it. But is it possible, even there, to find freedom?

I trust it is, because, ultimately, God is with us there. We can recognize and name and own up to our limits, but it is God who meets us there and who abides with us in our vulnerabilities. When Moses asks who he is to lead the Israelites out of Egypt, this is God’s answer: “I will be with you” (Exodus 3:12). This same God comes to us in Jesus, who not only aligned himself with the low, the outcast, the marginal, but was these things: he “emptied himself, taking the form of a slave” (Philippians 2:7, 8). And even now, in our own marginalized and disempowered state, Jesus promises to remain with us: “Remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age” (Matthew 28:20). And all this, not despite our limitations, but because of them: “God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). It may not make our limitations more bearable, but the truth is that God meets us there because God embraced those same limitations. In Christ, these very limitations become the instrument of our transformation.

This is the reality I am trying to live into, here and now, in the Monastery: an embrace of my limitations, both those I was born with and those I have chosen. But even more than that, this life means recognizing that I have been invited, all along, to know and name and embrace all the ways in which both my abilities and my limits have made me uniquely me.

I felt failure and frustration and shame and bruised pride when I couldn’t go around one more bend in the road that sweltering day in Belmont, when I couldn’t go one hundred more feet, when I couldn’t complete one more rotation of the pedals. I felt my limitation in a new, gut-wrenching way. And in doing so, I came to know something new, and something true, about myself: a unique, finite person, loved unconditionally and free to live richly, deeply, and mindfully in my own broad hall between narrow walls.

I have been invited to embrace all the ways in which both my abilities and limits have made me uniquely me.

On the surface, I appear to be a calm, collected monk.

Anxiety

Opening Up to God

Jack Crowley, SSJE

The first time I had a panic attack it felt like I was having the worst case of heartburn imaginable while simultaneously trying to breathe through a tiny straw. I was sitting at my desk in my dorm room during my junior year of college. I remember it was a beautiful fall day, and I had the window open. I was struggling to finish a paper when suddenly it all hit me.

My memory of that first panic attack is blurry, but I remember coming out of it laying on my bed looking out the window. I just kept begging myself to breathe deeper and deeper. My hand was on my chest, feeling my heart pounding away.

I have had a long, winding journey with anxiety. I’m in a much more stable place in my life now, but I still need to work on my anxiety on a daily basis. It is something I normally do not like to talk about, but in my last five years as a monk, I’ve been overwhelmed by the number of people I’ve talked to who have experiences with anxiety. I do believe we are in the midst of a mental health epidemic, and it does not help us to stay silent about our experiences. I do hope what I say can be of benefit to someone.

When I tell my friends and loved ones that I deal with anxiety on a daily basis, they are often surprised. I know on the surface I appear to be a calm, collected monk. One thing I have learned in my experiences with

Sometimes the most anxious person in the room is the last person you would suspect.

anxiety is you never really know how anxious someone is. Sometimes the most anxious person in the room is the last person you would suspect.

Because our appearances never tell the whole story about ourselves, it is important we open up to those closest to us about how we are feeling and doing. This is especially important when we are not doing well. I find even a brief conversation with a friend about something I’m anxious about can alleviate my anxiety tremendously.

One of the worst parts about anxiety is that it can fester. Anxiety can grow and grow inside of ourselves ad nauseum. We can have a tendency to tell ourselves to buckle down and think our way through what’s concerning us. We can also tell ourselves that we don’t need to talk to anyone else about what’s on our minds or that we don’t want to bother them. We may also fear that if we really open up to those around us about how we feel deep down, they may think of us differently.

Consider how you felt the last time someone close to you opened up to you about what was bothering them. If your experiences have been anything like mine, it was probably an intimate experience. You really got to know the person even better, and your relationship grew as a result. Next time you are hesitating to open up to a loved one, consider what benefit it can be to be the other person and your relationship with them.

The same goes with your relationship with God. Try talking to God about your anxiety. I do it all the time. Frequently throughout the day, I will say, “God, I am really anxious about ____, please help me out with it”. I will often repeat some version of this prayer many times until I feel like it has soaked through my anxiety, and I can think and breathe clearer.

I often find that anxiety can cut off my relationship with God. In times of great stress or anxiety, I will forget to ask God for help, thinking

that I need to solve everything myself. This is a dangerous pitfall of self-reliance.

I also find it helpful to reflect on how Jesus dealt with anxiety. It’s too easy to forget that Jesus was fully human, which means that he dealt with everything that goes with being a human being, including anxiety.

Think of Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane. I always have this uncomfortable yet intimate feeling whenever I reflect on Jesus’ mood at Gethsemane. I imagine Jesus being anxious over what was about to happen, yet simultaneously trying to communicate with his Father. We frequently have this image of Jesus being permanently calm, cool, and collected, yet it’s clear at Gethsemane that he was going through turmoil.

When Jesus asks his Father to “let this cup pass” from him, it is an incredible moment of vulnerability and anxiety from Jesus. On the one hand, Jesus is so anxious that he is trying to get out of the situation that he is in. On the other hand, he goes on to accept his Father’s will for him, and is faithful to the trust that it will be for the greater good.

We are often in similar situations in our lives, times when we say to ourselves, “Oh God, I’d rather be doing anything else or be anywhere else than right here and now.” It’s incredibly difficult to then accept our situation and ask God for help in making our way through it.

Yet we will keep coming back to these moments again and again in our lives. One thing I have learned in monastic living is that there is no escape from anxiety. Yet there is a way of faithful living through anxiety. Anxiety is a part of our lives, and we have no choice but to learn how to pray with it.

The Brakes

Learning Confict Resolution

Jim Woodrum, SSJE

Jim Woodrum, SSJE

“Oh, That I Had Wings Like a Dove”

I didn’t experience healthy examples of conflict resolution growing up. My parents were not happy in their marriage, and while there was no physical violence, wars of words were an everyday occurrence. Bullying was prevalent all through my primary and secondary education, with antagonism coming from both peers and teachers. Apparently if you wanted to motivate someone to behave and perform the way you wanted them to, there was no method more powerful than invoking fear and shame. You’re lazy. We’re just trying to learn how to live with you. You need to grow up. Why can’t you get your act together? These phrases I’ve heard and experienced my whole life.

Maybe this is why I have always had difficulty with conflict resolution. Throughout my life, I’ve wondered why there appear to be so many others who engage in conflict and emerge unscathed.

What about you? If you are like me, you may know the experience of having been bullied as a child and/or adult. You may have been singled out for ridicule based on your looks, your clothes, your interests, or your intellect. Perhaps you have been at the receiving end of verbal abuse from a teacher, mentor, employer, or someone whom you held in high

esteem. Maybe you have felt dismissed by a friend, family member, or spouse, and have felt unworthy of love, respect, or dignity.

According to an article published online by Psychology Today, verbal aggression not only damages a child’s self-esteem, but also has been found to alter the development of a child’s brain. Studies show that emotional pain affects the same part of the brain as physical pain, and that verbal aggression can be internally absorbed by the body. Author Peg Streep summarized the science this way: “Words are powerful—they can lift us up and beat us down, soothe us or wound us.”

To be honest, my tendency when I feel threatened is to exit the scene as quickly as possible. Among the rotation of Psalms that we Brothers pray during Morning Prayer at the Monastery is Psalm 55. Its subject is conflict, and I feel similar to the Psalmist when we chant their words: “And I said, ‘Oh, that I had wings like a dove! I would fly away and be at rest. I would flee to a far-off place and make my lodging in the wilderness. I would hasten to escape from the stormy wind and tempest.’”

This passage often takes me back to a memory from early high school. It was customary at band camp to dress the freshmen up in silly outfits one evening at dinner and then to rehearsal directly after. I remember being made to wear a tutu, wig, tiara, and make-up. I felt nothing but shame and humiliation. My fight, flight, or freeze response kicked in, and I chose to run as fast as I could. After a brief search, I was eventually found in my room by an upperclassman who calmed me down and talked me into participating in the initiation with my peers. But I’ll never forget that my initial reaction was that I was in danger, and rather than confronting it, I ran.

This insight to “flee” has carried over into my adulthood. I can attest to many instances throughout the years when, in a state of distress over some internal conflict in our community, I’ve fantasized about “switching communities” – which would be a life-sized version of the “flight” response. In truth, most of us belong to more than one community at a time, and it can be tempting in the face of conflict to simply imagine leaving. We might be prone to wonder: what would it be like if our immediate community (where we may be experiencing conflict more acutely) and our “outer” communities (where relationships may feel easier or less dangerous) switched places? Would being surrounded by different people assuage the intensity of conflict that we experience within our current inner circle?

Since becoming a monk, I’ve learned that this fantasy is inspired by a principle called acedia , which the desert monastics nicknamed “the noonday demon.” Acedia is the idea that the grass is greener in other pastures and that, by remaining in our current situation, we are missing out on all that would heal and complete us. While periods of discernment about a change in circumstances might sometime be warranted, usually, the process of healing and completion can often be found – through

God’s grace – exactly at the place that is the current source of our pain. Leaving would rob us of that chance.

And yet, if we are going to stay, we need to learn strategies for how to engage in conflict well. In an increasingly fast-paced and volatile world, where everyone is talking and no one is listening, learning strategies for self-awareness and the strengthening of the “brakes” of our minds is crucial.

I want to share some strategies that have proved helpful for me, and which we all—especially those of us who profess Jesus Christ (the prince of peace ) as Lord—can employ to strengthen our brakes and foster an atmosphere of safety within us and around us. I hope that these strategies will allow us to experience grace-filled resolutions at the source of conflict. Maybe even to be among the peace-makers in our own orbit.

First, it is crucial that we practice a healthy awareness of our bodies, which helps to facilitate how we experience the world around us, especially when we are in a place of uncertainty. Regardless of braintype, everyone is equipped with the reptilian brain response of fight, flight, or freeze. Unless you have well-honed self-awareness skills, limbic responses can exacerbate conflict through misunderstanding and miscommunication. When teaching neurodiverse children and adults about their ADHD brains, Psychiatrists Edward Hallowell and John Ratey use the metaphor of having a Ferrari engine for a brain that is ill-equipped with bicycle brakes. The key for those folks—and the rest of us—is to learn strategies that strengthen the brakes.

When I recognize a limbic response in my body resulting from a situation of disagreement with another person, especially someone in my innercircle, I try to reorient my response to one of curiosity rather than aggression. Curiosity helps me to investigate my feelings by asking a standard set of questions: “What do you mean when you say…..?” “Could

The process of healing and completion can often be found exactly at the place that is the current source of our pain.

you tell me more about that?” By asking the person questions from a place of curiosity, I am better able to determine why I am experiencing anxiety. Is what I thought I heard accurate, or did I misunderstand? Are the feelings I am experiencing in the present situation authentic, or are they tied to either a past situation or preconceived anxieties about the future? Limbic signals received during a disagreement or conflict with someone close to us can feel like—and therefore remind us of— past trauma. But that does not mean that trauma is occurring in this present moment. This truth recalls a slogan used in the room of 12-step recovery: “Feelings are not facts.” I have learned that it is more accurate to approach feelings as theories, which—just as in a scientific laboratory— need to be tested quantitatively. Once we determine their accuracy, then we can respond with the intention of preserving the dignity of both us and our perceived adversary.

A second call to awareness stems from the covenant that we enter into at our Baptism, and which that we reaffirm liturgically throughout our lives as Christians: “Will you strive for justice and peace among all people, and respect the dignity of every human being?” We answer: “I will, with God’s help.” Communities of belonging require, in a sense, that we share a particular vulnerability with each other. To be vulnerable is to let down our guards; to expose our hearts with the assurance that they will be

handled with reverence and care. This does not mean that accidents will never happen and that our hearts won’t be injured or even broken. What it does mean, hopefully, is that our hearts will be handled with the intention of care and respect. Taking part in an intentional community presupposes that we will do the same with the hearts of those who form that community with us. I am always struck by the passage in the third chapter of the epistle of James: “For every species of beast and bird, of reptile and sea creature, can be tamed and has been tamed by the human species, but no one can tame the tongue—a restless evil, full of deadly poison. With it we bless the Lord and Father, and with it we curse those who are made in the likeness of God.”

We’re all made in the image of God and, through our Baptisms, we have been joined one to another as children of God; we are called to let that identity guide us, in moments of conflict, towards words that uphold the dignity of one another. I recall a time when I was in a particular state of anxiety about a disagreement with someone and was having trouble viewing that person compassionately. I was worried about an upcoming difficult conversation, and didn’t have high hopes for it ending amicably. My spiritual director said something that was a great help and has served me well many times since. They said: “When you sit down together, begin with a prayer and know that Jesus is in the room with you both. As you proceed with the conversation, be aware of God’s presence and then ask yourselves, ‘What does Jesus want for the both of you at the outcome?’”

Forgiveness and reconciliation do not necessarily require resolution , but they do require empathy, compassion, respect, and dignity, which should help to forge a path forward. Disagreement doesn’t have to lead to estrangement—which is too easy to forget when we are experiencing intense feelings and emotions. The key is to recognize each other’s willingness to be vulnerable and to work out the source of tension together in a safe atmosphere.

Sometimes, to create a safe atmosphere, it may be helpful to have a facilitator join you. If it’s agreeable, ask someone else to listen and guide your conversation with the goal of helping you both reach a dignified solution. We need to foster a safe environment in which we can see each other’s wounds and then mutually salve them for healing.

Third, recognize that it’s okay to be angry. The visceral experience of anger is not an enjoyable one, but it is necessary, especially in the face of injustice (whether our own or that of another). Being angry is not itself a sin, but how we deal with and entertain that anger is what can potentially lead to sin. If our anger leads us to a place of vengeance and retribution, then it is probable that we’re in murky waters. But is it also possible that our anger could lead us toward a grace-filled resolution and healing?

In this book Self Discipline, an early member of our community, Fr. Arthur Hall SSJE, points out that Jesus experienced the full array of emotions

in his humanity that we do—and this includes anger. Yet, Jesus shows us the proper handling of anger through his example. Take this scene in the gospel of Mark:

Again, he entered the synagogue, and a man was there who had a withered hand. They watched him to see whether he would cure him on the sabbath, so that they might accuse him. And he said to the man who had the withered hand, “Come forward.” Then he said to them, “Is it lawful to good or to do harm on the sabbath; to save a life or to kill?” But they were silent. He looked around at them with anger; he was grieved at their hardness of heart and said to the man, “Stretch out your hand.” He stretched it out, and his hand was restored.

In Jesus’ example, we see that his anger led to healing and wholeness, rather than to fear, shame, or retribution. First, we acknowledge that we are angry, and then we need to think how that anger can be used constructively for the betterment of all involved, rather than for destruction. If we can practice this locally, in our one-on-one relationships, it is possible that we could begin to learn to do this more fully on a societal level as well.

I have to admit that I am far from perfect in employing the strategies mentioned above. Sometimes, my brakes fail and I have to approach my colleague, friend, Brother and say, “I’m sorry. I ask for your forgiveness. Could we press the reset button and begin again?” The cure to my instinct to flee the scene is instead to stay put: to approach the other with humility, to acknowledge lessons learned, and to ask to begin afresh.

The ancient monastic teaching around stability advises that, as long as a safe environment has been fostered, we must stay grounded at the source of our pain, to work through our differences, so that any breech may be healed. We have to remember that Jesus is God Emmanuel –which means “God with us.” What does Jesus want for those who are engaged in conflict? Healing and wholeness. He teaches us to stay. And we can know that he stays with us.

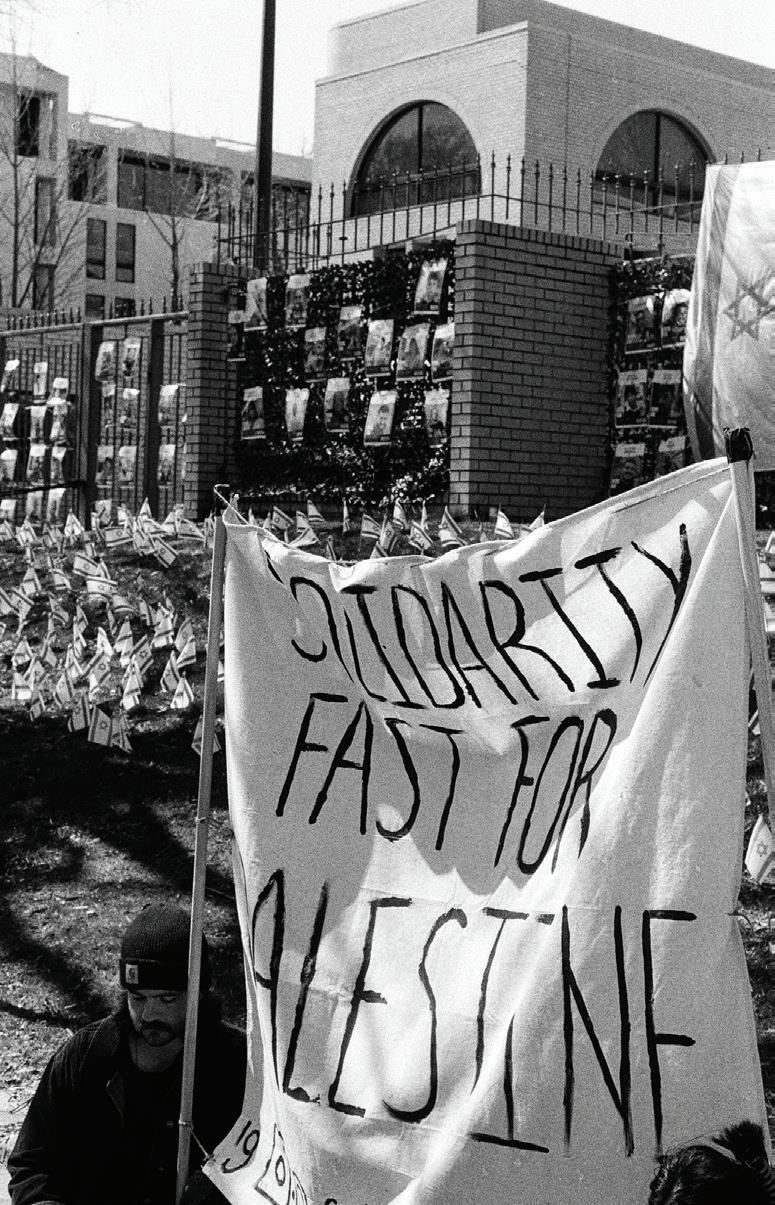

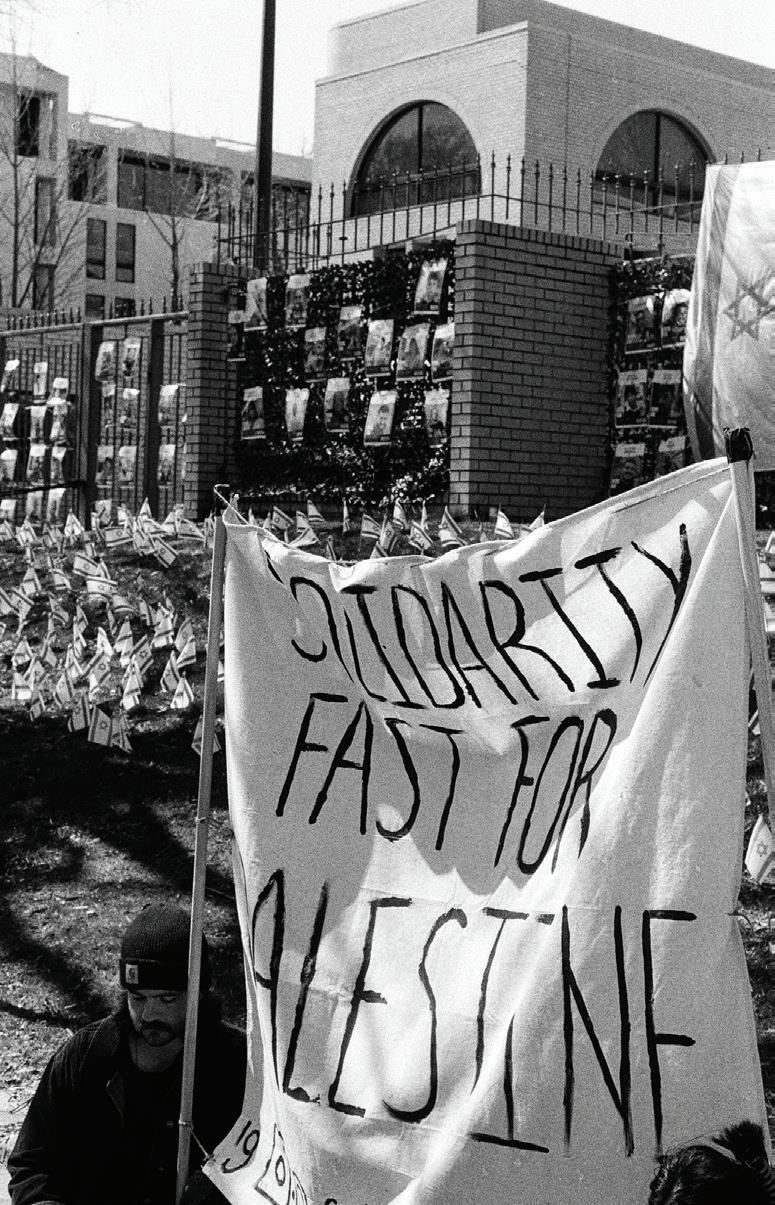

A Word with the Fellowship

The Brothers of SSJE pray regularly for the cessation of war, the safe return of captives, and just and lasting peace for the Holy Land. We spoke with Christian Calawa, a regular worshiper at the Monastery, about a recent experience of prayer and fasting for peace in Gaza that he helped organize.

Can you describe for us the basic outline of the fast?

The week was a 5-day fast with a core group of people down in D.C. Some people had to come and go, but there were five of us who went without food for five days. There were a lot of people who joined remotely, largely in New England and some outside of New England and the East Coast. They joined in prayer twice a day, on a Zoom meeting that was structured. It was all very interfaith. We went from spiritual breathing exercises in the Ayurvedic tradition, to Compline, to other forms of prayers. But a lot of this was born out of a feeling of helplessness, a feeling that this world is very big and a lot larger than we’re able to engage with meaningfully in the way that we want to – that feeling being one of paralysis, and acceptance, and trust and belief that prayer is meaningful action, that prayer is not a passive thing to a God who is absent; that our prayer and intercessions are real and worthy of time. This is way we can participate as members of the faith community. It largely ended up being Christian.

We were down in D.C., and we spent one day each in front of big D.C. institutions: the White House, the Capitol building, the Israeli embassy, the Holocaust Museum, the Washington National Cathedral. Each day, the prayer was pointed toward the institution we were sitting outside of. There was prayer for wisdom, prayer for peace, prayer not to be bound by the normal political order that would often be slow or ineffective or managerial, prayer for meaningful action. That included all different forms; we weren’t very prescriptive on what prayer meant or what we wanted it to mean. I think allowing space for people to pray for deliverance, for justice, for aid, things both practical and impractical, that ultimately the God who is sovereign over all of this would be in control, that good may come out of the seemingly endless

darkness – was surrounding a lot of this.

Why fasting? Why did that feel like the appropriate response?

Fasting met this intersection of traditional political action and religious devotion that a lot of us found very intriguing, and which brought with it some potential downfalls as well. We were inspired by Dorothy Day, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Gandhi –these social movements that are very much praised, that were rooted in a personal decision of piety that was then public facing – mixed with the devotional call to fasting found in the religious life, which is the emptying of oneself and relying solely on manna that is from heaven and not from earth. The intersection of those things felt very true to this cause and spoke to a lot of the powerlessness that we feel as we asked what would sharpen our resolve in this tradition of political nonviolence, combined with spiritual devotion in the immediacy of need for God found in just being hungry, and all of the things that happen to the body that correspond to that, all the strange desires that come about from being hungry. Fasting really hones your sense of needing to rely on Christ in a way that does not depend on your own will or your own strength. There’s a recognition of weakness that I think is really important when coupled with political engagement, a humility that does not come from strength.

It felt good to go and protest, and I’m glad we did. But the orientation of that action in oneself always has

to be, if honestly taken account of, toward the God we love and serve.

How does religious belief connect with poilitical engagement?

An engaged church community can be a real force against hopelessness and despair, both here and abroad. One of the people who was fasting remotely contacted us, and they had contacted family members that they had in Gaza, and they reached out to them and told them about the fast that was going on, and the remote faster told us that the person in Gaza just told everybody, and they all prayed for our movement, and were overjoyed that there was real attention and care being brought out. It was a surprisingly emotional moment, where I think a lot of the orientation had been, “What can we do for Gaza? What can we do about our church’s complicity in sending money and weapons?” But that script also being reversed, not only can we bless the people in Gaza, but they can bless us back, and give us real strength for the rest of that day. That was the fourth day, when we were all very hungry and counting down the hours until we could eat again. That that mutual exchange was so life-giving and affirming of a love that speaks far beyond any of our immediate actions.

Read the full interview and see images online.

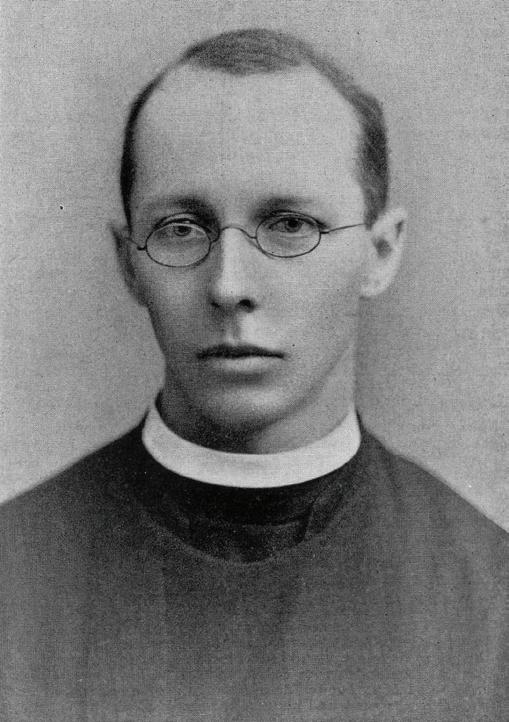

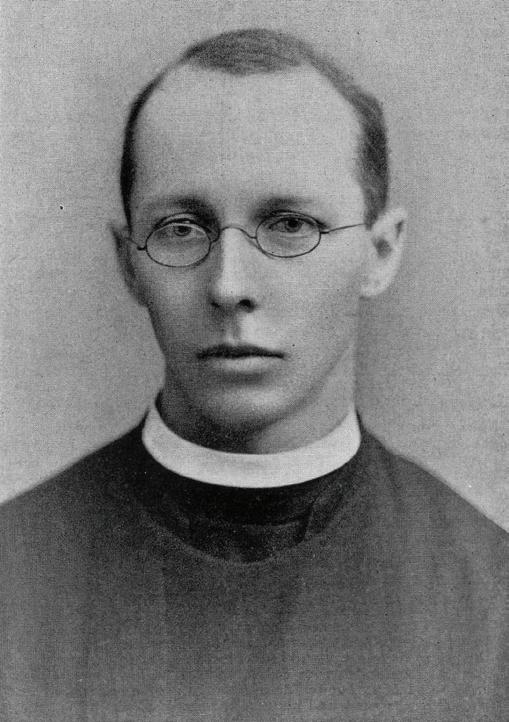

Father William Hawks Longridge, SSJE (1848-1930)

It was about 5:15 in the morning, and I was in the shower. There was shampoo in my hair, and my eyes were closed. I was busy imagining an argument with a Brother, which probably wouldn’t even happen.

The argument was over dried fruit. You see, I had been getting the impression that a particular Brother of mine didn’t think I was replacing the dried fruit often enough. (This all happened back when I was a postulant, and my job was to be the pantry monitor. One task of being the pantry monitor was making sure our supply of dried fruit in the pantry never ran out.)

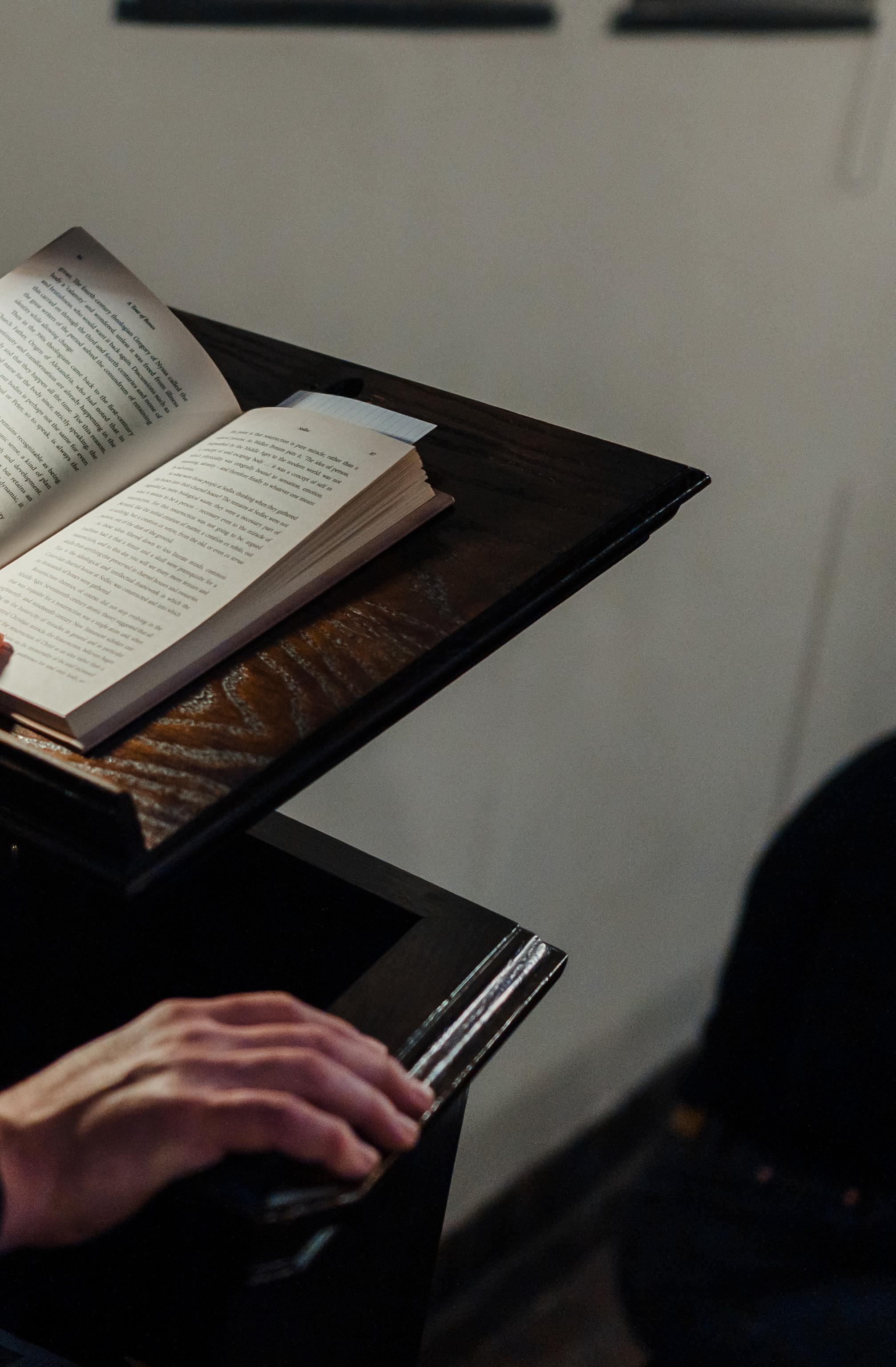

The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola have exerted a profound infuence of the spirituality of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist. Father Benson, our principal founder, used them as a model for his own retreat addresses to the community, and for decades, the Society required novices to complete them as part of their discernment of a religious vocation with SSJE. Even today, SSJE Brothers rely on the wisdom and insights of St. Ignatius, especially in their ministries of retreat-leading and spiritual direction.

Now, this particular Brother, in my experience, was the biggest consumer of dried fruit in the whole Monastery. One day, that Brother walked over to a piece of paper we kept clipped to a cupboard in the pantry. That piece of paper had a list of tasks the pantry monitor was supposed to do. I noticed my Brother giving the list a long look, then looking at me, then looking back at the list. Finally, he walked over to me and said that refilling the dried fruit was on the list of tasks for the pantry monitor. Then he walked away. It was a simple enough exchange.

And yet, there I was the next morning in the shower, unable to stop thinking about what I should have said to him or what I would say if he mentioned something about the dried fruit again. I can’t remember how long this went on or how it resolved, but here I am, about five years later, and I still remember that moment.

There is no denying the fact that life in a community can be tough. Back when I was an inquirer, it seemed like every single Brother warned me about the difficulties of life in community. Of course, I believed them, but there’s a massive difference between hearing about something and actually experiencing it firsthand. Try to imagine thirteen men of all different ages and backgrounds living together in one large house. They all share their meals together, run a church collectively, operate a non-profit business as a team, and sleep in bedrooms the size of walk-in closets. Most of these men have committed to doing this for the rest of their lives. This may sound like heaven, hell, or purgatory to you. I would say it’s a little bit of all three!

In truth, we have Father William Hawks Longridge to thank for the strong connection between SSJE spirituality and Ignatian spirituality. After his death, Father Longridge was described by Father H.P. Bull, the Superior General of SSJE at the time, as “a sensitive scholar, shy and retiring by nature, with a slight stutter in his speech” who, nevertheless, had a “great spiritual influence” on many people, especially students. He had a lifelong devotion to The Spiritual Exercises and drew on them in his retreats and writings. In 1919, he published his greatest work: a new translation of the original Spanish text of The Spiritual Exercises with a detailed commentary on them, as well as an English translation of the Directorium , a manual of instructions for retreat directors. Some questioned whether “the study of a Catholic book by an Anglican pen could prove a success,” but upon its publication, its value was immediately recognized by many, including by the Society of Jesus itself. One Jesuit wrote, “whoever takes the trouble to peruse even only the first page of the Introduction will at once realize that this English clergyman has sought to understand the high spirituality of [The Exercises].” Ten days before his death, a Jesuit friend wrote to Father Longridge to tell him that “your perfect book has been recommended by a Congregation of all the Society [of Jesus] for general use, and it will be used by all with remarkable proft to the whole Society [of Jesus]. God bless you for what you have done.” Father Longridge’s translation became, for several decades, the standard translation used by the Jesuits.

Life in a community can be challenging, but it is also incredibly rewarding. Living at SSJE with my Brothers has been one of the most profound experiences of my life. In particular, life in community has taught me I

On The Hard Road encountering Jesus along the way

Hard as it is to believe: this is resurrection: feeling loss and disorientation, long talks of grief, and receiving a stranger’s compassionate presence.

Luke Ditewig, SSJE

Luke Ditewig, SSJE

We never thought life would be like this, never considered we could lose so much. Death keeps shattering our plans and expectations with loss. Everything is upended. The world feels doomed, and things don’t make sense anymore. What will happen next?

It’s hard to believe he’s gone. We’ve been together so long.

The doctors said there’s not much they can do.

If I lose this job, I don’t know how to keep supporting them.

We can’t go back. We have to find a way here.

Our words of disbelief and grief today could echo back, nearly unchanged, those spoken two thousand years ago, when two grieving companions talked together on the road to Emmaus. They shared their grief at losing Jesus, their friend, whom they expected would save them, but who was betrayed, killed, and buried. They talked of the body missing, and people supposedly seeing angels.

As these two walk to Emmaus, Jesus comes walking alongside them. They don’t recognize the one they love. The man asks about their conversation, sees and hears their sadness, and then shares about his own suffering, speaking through the language of scripture.

Hard as it is to believe, this is resurrection: feeling loss and disorientation, long talks of grief, and receiving a stranger’s compassionate presence. Easter does not come with quick fixes or easy answers. There are times when we do not even see that Jesus is here, alive, with us: Jesus came to Mary as she visited the tomb, and she supposed him to be a gardener; he came to a frightened community gathered behind locked doors; to a group out fishing for whom he provided breakfast; and to these two friends, on the way and linked in sad talk.

This is still true: Jesus comes where we are now, amid difficult emotions,

perplexing questions, as we walk and eat. Frederick Buechner wrote: “Jesus is apt to come into the very midst of life at its most real and inescapable moments. … He never approached from on high, but always in the midst, in the midst of people, in the midst of real life and the questions that real life asks.”1

One way to see Jesus is to stop and look back. Ignatius of Loyola taught that reflecting and then giving thanks is a key way to pray. I see Jesus more easily by looking back. In the past day or more, for what are you most thankful? Perhaps a kind word or gesture, a fear unmanifested, a beauty glimpsed, a memory recalled. “How did you receive love? When were you most fully alive?”2 Sometimes it’s only after an experience that we can see what it truly held and meant for us. When the two disciples finally recognized Jesus in Emmaus, they were then able to remember their “hearts burning within” while Jesus spoke to them on the road. Recognition comes later. We have to stop and look back to not miss it.

To see Jesus, we often have to seek company. If you feel blind and weighed down in grief, you are not alone. Many of us feel the same. Like the two companions on the road, speak your grief to compassionate friends and strangers. Pray even when God feels absent. Jesus is present alongside us including when we do not see him.

Pray your pain. If you’re wanting help with words, about half of the psalms are honest examples. Start with Psalm 13 and Psalm 102. Lament is a cry of pain and a cry of trust. It is stark and boldly real about pain and suffering, and it assumes being heard.

Lament is not just for Lent or Holy Week but for life. Even God grieves! In Genesis 6, God “grieved in the heart” at how people behaved. Jesus wept over Jerusalem and at the tomb of his friend Lazarus. From the cross, Jesus cried out with words from Psalm 22, trust and question in tender, wrenching symmetry:3 “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Lament is our ancient prayer and part of being human.4

Consider this: How do you know when children are upset? They flail, cry, hit, stomp, and resist. How do children look when at ease, trusting? They slump, lean into us and objects, hug back, and rest.

1 Frederick Buechner. (1966) The Magnifcent Defeat. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

2 Patrick D. Miller, “Heaven’s Prisoners: The Lament as Christian Prayer” in Lament: Reclaiming Practices in Pulpit, Pew, and Public Square. (2005) Eds. Sally A. Brown and Patrick D. Miller. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, p16.

3 Ibid, 21.

4 Prayers for pain and trust adapted from InterPlay, an improv movement and storytelling community practice.

As a child of God, I find that one way I am praying is like a child: with my body. I hit the air with my fists, then slowly push and pull as with a heavy object. Tensing arms and clenching fists, I curl or twist and stay in that tension offering my constricted self. This is a way of praying, expressing the pain.

Then I let go and relax, leaning against a wall or lying on the floor, letting my whole weight be supported. Taking deep breaths, I trust God holds me fully. I also stand with my arms outstretched and tilted back imagining I am floating in the ocean, or alternately tilted forward as if floating on a cloud. These are ways of expressing and feeling trust.

Music beckons the body to move, to dance, to express sighs too deep for words. Pray with music that prompts such tensing and hitting pain or such floating trust – or find music that invites both. Children of God, pray your confusion and pain, what is hard to bear. Ask for grace to trust and move in such a way that you can feel free to express and receive what is true for you.

Psychiatrist Curt Thompson encourages us to not deny our losses or diminish them by trying to compare our experience with someone else. Your grief is real, and it is yours. Thompson suggests writing down each day at least one thing you have lost or are losing. Then also name a couple things for which you are thankful. In this way, pray both grief and gratitude.5

A tree with a large broken limb hanging down inspires both these moods of prayer in me. I let one arm bend, droop, twist, and hang, feeling the weight of what is broken and hurts. I then raise the other arm upward like healthy limbs in gratitude. Like the tree, I experience both realities at the same time and thus pray weight and wonder, grief and gratitude.

Jesus persistently comes to us, with us, alongside us – including when we do not see him. Not in dazzling power, but in the glimmering presence of shared stories, Jesus walks and eats with us. Pray your story wherever you are in its unfolding, perhaps with movements, shaking pain or floating trust. Jesus is with us, grieving with us, listening with love, and gently fanning our soul’s faint embers into flame.

5 Curt Thompson. (April 21, 2020) Blog: “Infammation of the Heart.”

the rest of my life

an interview about vocation

A journey toward meaning, purpose, and home.

Lucas Hall, SSJE

Q: Take us back to the beginning: when did you first start to have a sense of a monastic vocation, and what was it that was drawing you?

I first started going to an Episcopal church in college. I was very eager to learn more and go deeper, so I met with the priest there regularly, usually at least once a month, to ask him a bunch of questions (and leave with a bunch of books). Eventually, I approached him and said that I was interested in talking about – well, I didn’t call it this, but – vocational discernment. He was the one who suggested a monastic vocation to me, based on some of the things he’d been hearing from me and seeing in me over the previous months. And while it didn’t immediately click, something about it planted its roots in my brain.

I was thinking about it every day. Finally, after a few months, I sent that priest an email and said, “I think I need to meet with you again, because – to my surprise – this idea is just not leaving. I think about this every day now.”

I will also say that I remember even being a kid and not having much of a religious context, yet being fascinated by monks or monk-like figures that I encountered in pop culture. I loved the Jedi in Star Wars. I loved the book series, Redwall, about woodland creatures living in Redwall Abbey, a monastic setting in a forest in England. I remember I really loved watching the Disney film, the animated Robin Hood and seeing Friar Tuck. So as a child, I had these Jedi warrior monks and these monastic woodland creatures whom I just loved. I found them so fascinating, even though I had no broader context for it. But, it’s interesting that even though this vocation certainly started explicitly when I was in college, there was also just something attractive about it for me, in the ways I encountered it, from an early age.

Q: Was there any resistance or reluctance, or was your sense of being called to this more an experience of eagerness?

Oh, there was fear. I visited a few different communities, and there was definitely some fear and trembling each time. When I came on visits here, to SSJE, I very purposefully asked each Brother I met with, “How did you get here?” I was trying to wrap my head around how a real person ends up in this situation. Trying to see the people here as real people was a major part of being able to see myself here.

I came to the Monastery when I was twenty-four, which was pretty young. I was asking, “Am I too young? Maybe this could be right in the future, but maybe not now?” I was raised with the expectation that you’re not going to stay in the same career all your life. You’re not going to live in the same place all of your life. And so there was some real fear for me around the awareness that I could be starting a path that ends up with me moving here and doing this for the rest of my life. That was scary. Yet as I considered my options, I did a lot of thinking about whether I was attracted to those options as they were, in themselves, or whether I was attracted to the idea of having options. And ultimately it was the latter. I realized that question of “options” was more of an impediment to me choosing something I wanted, rather than the actual freedom it seemed like. I realized that what I really wanted was this.

Q: Once you arrived, was it different than you’d anticipated?

I think everyone goes through some disillusionment when they first come here. That sounds bad, but the removal of illusion is a good thing (it’s just a painful thing). It might be disillusionment about the community;

it could be disillusionment about specific individuals; it could be disillusionment about yourself. I certainly had all three.

Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, has written several books about the spirituality of Benedictine monasticism. In one of the introductory chapters of The Benedictine Way he talks about how monastic asceticism is directed to an end: to teach people to rely on God. Being troubled or disillusioned is kind of a necessary part of that. And that includes being disillusioned with yourself.

You know, I didn’t magically become an expert at the contemplative life or something. Some days I still struggle with very basic things that I think I should have moved on from by now. But that’s also led to changes in me; there’s real growth. Those very challenges that push against the romantic image you might have in your head are directed, in the end, to growth in love of God and love of neighbor. It’s pretty basic stuff – not just for the monk, but for the Christian – but it’s what’s most important.

Q: What advice would you give to someone at the beginning stages of discerning a possible vocation to monastic life?

Ask God! Involve God in your decision-making. Don’t just try and guess at God’s will, but actually pray about it.

Discernment also involves talking with people who know you – whether that’s on a personal level, with your friends and family, or in a pastoral way, as when I talked with my priest. One of the most important conversations I had when I was inquiring into this life took place with a friend of mine who was raised as a Muslim and who was basically nonreligious in his day-to-day life. I had no deep spiritual common ground with him, and he had no context for this way of life, but when I told him, “I’m thinking of becoming a monk,” he said, “Yeah, I can see that.” He knew me. Listening to the input of others, both the people around you and of course, God, can be a very good way of testing what you feel might be a call.

Q: How has life changed on the other side of life vows?

In monastic life, there are these very tangible stages, where you know that in a few months or in a few years, there’s a new decision to make. But after life vows, there isn’t a next stage. That feels a little weird initially, because it’s sort of like, “Okay, now what? Now what do I look forward to?” But quickly, that feeling was replaced with sense of a lot of freedom to act. I’ve chosen a solid foundation, and I can act from that foundation now. I feel a lot of freedom to do that because it’s now secure in a way it wasn’t before.

After life vows, you’re on a lifelong timespan, and there’s a lot more freedom in the imagining of what could be real in your life here. I’ve come more and more to realize that my desire to have other options

actually can be an impediment to me freely making the choices I want to make. And so I have found – in actually making that choice and locking it down – a real sense of freedom. I have the rest of my life to figure out the structure or structures that make my prayer happen, and facilitate my relationship with God, and facilitate my ability to love others – all of those things I feel so deeply called to do. Now I have the time and space, the community and the place, in which to do that life’s work. “Now what?” I ask myself. And, you know, that’s, that’s an exciting question for me, because there are lots of possibilities, and I have the rest of my life to find my different answers.

“Now what?” I ask myself. And, you know, that’s, that’s an exciting question for me, because there are lots of possibilities, and I have the rest of my life to find my di erent answers.

In addition to creating works of visual art across multiple media (including many photographs that grace these Cowley pages), Br. Luke creates candles that he invites people to use in prayer.

Wax (2024) – Luke Ditewig, SSJE

The LEGACY SOCIETY of SSJE

To paraphrase a section of SSJE’s Rule of Life, “our purpose as a Society is to bring people into closer union with God in Christ, by the power of the Spirit…” At the time of SSJE’s founding, Fr. Benson saw the Society’s mission fields as being both at home and abroad. Today, through the internet, it takes but a second to reach our neighbors next door or our neighbors worldwide, thereby bringing the Monastery to your kitchen table, your car, or wherever you are called in your daily life.

Legacy Gifts help us adapt to the needs and opportunities of the mission field now and in the future. Fr. Benson likely never imagined the opportunities the internet could provide us on the mission field. No doubt the future holds opportunities we cannot imagine. Whatever the medium is, our core mission, like God’s Word, will remain unchanged yet ever new. Please consider remembering SSJE in your will. Doing so will support our ability to carry forth on the mission field in whatever direction it may take.