JAnuAry 2023

2023 Chair’s Perspective Perspective on Long Haul COVID: Is This Related to PANS (Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome) in Children?

Gaslighting and Health Care

JAnuAry 2023

2023 Chair’s Perspective Perspective on Long Haul COVID: Is This Related to PANS (Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome) in Children?

Gaslighting and Health Care

When your patients need the best possible specialty care, AHN has physicians with world-class expertise — like our new medical oncologist.

Dr. Rosenblum offers some of the most advanced treatments and techniques, to ensure patients have the best possible outcomes.

Rachel Rosenblum, MD

Medical oncologist

Location: AHN Cancer Institute 314 East North Avenue, Level 1 Pittsburgh, PA 15212

Specialties : Treatment of thoracic malignancies, including lung cancer, thymoma, and mesothelioma

To refer your patient, call 412-578-HOPE (4673). Most

2023 Chair’s Perspective .......5

Peter Ellis, MD

Editorial....................................6

• I Am My Relationships. Deval (Reshma) Paranjpe, MD, MBA, FACS

Associate Editorial ..................8

• Perspective on Long-Haul COVID: Is This Related to PANS (Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome) in Children?

Are There Specific Treatment Options?

Anthony Kovatch, MD

Editorial ..................................12

• Silent Sentinel

Richard H. Daffner, MD, FACR

Perspective ............................16

• Gaslighting and Health Care

Timothy Lesaca, MD

Foundation Featured Grant

Recipient ................................18

• Strong Women, Strong Girls

Society News .........................20

• Pittsburgh Ophthalmology Society

58th Annual Meeting and 43rd Ophthalmic Personnel Meeting slated for March 10,2023

Society News .........................21

• 43rd Annual Meeting for Ophthalmic Personnel

Society News .........................22

• Clinical Update on Geriatric Medicine

Society News .........................23

• December 1 Monthly Meeting

Featuring Sunil Srivastava, MD

ACMS Welcomes 2023 President......................24

Materia Medica ......................25

• The Updated CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Pain: Increased Patient-Centered Guidance

Karen M. Fancher, PharmD, BCOP

Open Letter to the Editor.......29

Legal Summary.......................30

• What to Do When Under Investigation

William H. Maruca, Esq. and Nathan Huddell, Esq.

Navigating Your Career in Medicine ...............................34

ACMS Meeting Schedule ......36

Oakmont Moon

Malcolm P. Berger, MD

Dr. Berger specializes in Neurology

2023

Executive Committee and Board of Directors

President

Matthew B. Straka, MD

President-elect

Raymond E. Pontzer, MD

Secretary

Keith T. Kanel, MD

Treasurer

William Coppula, MD

Board Chair

Peter G. Ellis, MD

Term Expires 2023

Michael M.Aziz, MD

MicahA. Jacobs, MD

BruceA. MacLeod, MD

AmeliaA. Paré, MD

Adele L. Towers, MD

Term Expires 2024

Douglas F. Clough, MD

Kirsten D. Lin, MD

Jan B. Madison, MD

Raymond J. Pan, MD

G.Alan Yeasted, MD

Term Expires 2025

AnuradhaAnand,MD

Amber Elway, DO

Mark Goodman, MD

Elizabeth Ungerman, MD

Alexander Yu, MD

G. Alan Yeasted

Bylaws

Raymond E. Pontzer

Finance

William Coppula, MD

Nominating

Raymond E. Pontzer

Medical Editor Deval (Reshma) Paranjpe (reshma_paranjpe@hotmail.com)

Associate Editors

Douglas F. Clough (dclough@acms.org)

Richard H. Daffner (rdaffner@acms.org)

Kristen M. Ehrenberger (kehrenberger@acms.org)

Anthony L. Kovatch (mkovatch@comcast.net)

Joseph C. Paviglianiti (jcpmd@pedstrab.com)

Andrea G. Witlin (agwmfm@gmail.com)

ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF

Executive Director

Sara Hussey (shussey@acms.org)

Vice President - Member and Association Services

Nadine M. Popovich (npopovich@acms.org)

Manager - Member and Association Services

Eileen Taylor (etaylor@acms.org)

Co-Presidents

Patty Barnett Barbara Wible

Recording Secretary

Justina Purpura

Administrative & Marketing Assistant Melanie Mayer (mmayer@acms.org)

Director of Publications Cindy Warren (cwarren@pamedsoc.org)

Part-Time Controller

Elizabeth Yurkovich (eyurkovich@acms.org)

Corresponding Secretary

Doris Delserone

Treasurer

Sandra Da Costa

Assistant Treasurer

Liz Blume

OFFICES: Bulletin of the Allegheny County Medical Society, 850 Ridge Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15212; (412) 321-5030; fax (412) 321-5323. USPS #072920. PUBLISHER: Allegheny County Medical Society at above address.

The Bulletin of the Allegheny County Medical Society is presented as a report in accordance with ACMS Bylaws.

The Bulletin of the Allegheny County Medical Society welcomes contributions from readers, physicians, medical students, members of allied professions, spouses, etc. Items may be letters, informal clinical reports, editorials, or articles. Contributions are received with the understanding that they are not under simultaneous consideration by another publication.

Issued the third Saturday of each month. Deadline for submission of copy is the SECOND Monday preceding publication date. Periodical postage paid at Pittsburgh, PA.

Bulletin of the Allegheny County Medical Society reserves the right to edit all reader contributions for brevity, clarity and length as well as to reject any subject material submitted. The opinions expressed in the Editorials and other opinion pieces are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Allegheny County Medical Society, the institution with which the author is affiliated, or the opinion of the Editorial Board. Advertisements do not imply sponsorship by or endorsement of the ACMS, except where noted.

Publisher reserves the right to exclude any advertisement which in its opinion does not conform to the standards of the publication. The acceptance of advertising in this publication in no way constitutes approval or endorsement of products or services by the Allegheny County Medical Society of any company or its products.

Annual subscriptions: $60

Advertising rates and information available by calling (412) 321-5030 or online at www.acms.org.

COPYRIGHT 2023: ALLEGHENY COUNTY MEDICAL SOCIETY

POSTMASTER—Send address changes to: Bulletin of the Allegheny County Medical Society, 850 Ridge Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15212.

First and foremost, Happy New Year to all.

Earlier this year, as President of ACMS, I posted an update to let all of you know that we had hired Sara Hussey as our new Executive Director. I also outlined goals for the year. This note is to let you know how we did and what we are looking forward to in 2023.

To start, Sara has had a wonderful first nine months as Executive Director. We have been more than pleased with her performance, responsiveness and support of the Board and its mission. Some accomplishments include rebuilding our office staff (which was down to just Sara and Nadine as full employees in early March 2022). Sara has hired two new full-time staff members, Eileen Taylor—Manager of Membership and Association Services, and Melanie Mayer—Marketing and Administrative Assistant. Additionally, as of Jan. 3, she has brought in Elizabeth Yurkovich to serve as the ACMS Part-Time Controller.

This team is already working together admirably to provide services to our members and drive initiatives. Sara has successfully restructured the organization to eliminate distractions from our core mission of providing support to physicians of Allegheny County. She has completed work with your Treasurer and Finance Chair, Dr. Keith Kanel, to revamp financials and reporting to allow transparency and understanding. She has stepped in to take a leadership role in the ACMS Foundation to raise its profile and support its mission in the county.

The above list of accomplishments is not exhaustive but suffice it to say that your Executive Committee of the Board of Directors is delighted with progress to date.

We are now confident that we have the team and organization to pursue key initiatives of the ACMS in the coming year. Those initiatives include opportunities to streamline the management we provide to our affiliated associations such as the American College of Surgeons Southwestern PA Chapter, Greater Pittsburgh Diabetes Club, and others. We will review the current format of the monthly Bulletin to ensure it is maximally aligned with our mission of physician support, education, and awareness. We will initiate a local advocacy program to address issues of importance to our members from a county perspective and, of course, strive for an increase in membership in the ACMS by proving it to be a valued resource for all physicians of Allegheny County.

Thank you for your continued support as we strive to make the organization an asset to the physicians, patients, and welfare of the county.

If you have questions or wish to participate in our efforts, please feel free to reach out directly to me or to Sara at the ACMS (shussey@acms.org).

Sincerely,

Peter Ellis, MD Chair of ACMS Board, 2023

Many years ago, my best friend from sophomore year of college told me a vignette about his Dad that has stayed in my mind. His father was almost a mythic figure who demanded excellence in everything and everyone; he was a teacher, an ex-monk, and a perfectionist who was coding long before the Silicon Valley boom. Given this intimidating set of facts, I was heartened to learn that the man was also famous for his warm } bear hugs. The pearl that I took away from the vignette was his Dad’s one line self-description, namely: “I am my relationships.”

Think about that for a moment.

“I am my relationships.”

Last month, Franco Harris suddenly passed away, leaving a shocked, stunned and grieving city and football nation which had been preparing for the celebration of retiring his number and instead found itself mourning his loss.. Franco Harris was a national football hero, but he was also our local champion in every aspect of life, not just football. As I waited in line outside Acrisure Stadium in the bitter cold and

snow to pay my respects to his family at the visitation, the thousands of strangers I queued with were exchanging stories. Every single person I met had a personal story about Franco---brief but lovely conversations they had had, jokes they had told each other, Franco paying for a complete stranger’s taxi or lunch with the characteristic kindness that was in Franco’s molecular makeup.

The man was everywhere and showed up in the true sense of the phrase for everything and everybody. He was everyone’s Dad and brother and son and friend who came to awards ceremonies, ribbon cuttings, panels, big charity events, and little neighborhood celebrations. He showed up to raise awareness for good causes in the bad parts of town. He lent his star quality and mythic presence to so many good works that it would likely take another lifetime to catalogue.

One man recounted spending a magical day as a child with Franco. His elementary school class team had raised the most money for charity, and their reward was a Gateway Clipper Cruise with Franco Harris. “He was so famous that he could have chosen to be anywhere in the world with anyone more important—but the fact that he chose to

spend his day happily engaging with a bunch of elementary school kids on a Gateway Clipper cruise tells you everything about the kind of man he was.”

Another woman remembered Franco coming out mid-pandemic to a vaccination drive in Clairton and encouraging others to sign up to get vaccinated in a climate where fear and distrust were rampant and disease was spreading. His calm presence and kind energy doubtless saved lives in downtrodden communities as well as the larger world-- heroes are always in short supply, and Franco was certainly a hero and role model.

Franco turned our city into a family, and bridged divides. His own family shared him with us; he had a personal relationship with tens of thousands of individual people in his lifetime, perhaps more. Like Mr. Rogers, no one could find a single negative thing he ever said or did; how many people like that do you know in your life? Here was a man who had fame and fortune and remained grounded, genuine and good. Here was a man who spent his postfootball career helping everyone he could in the largest and the smallest of ways-- from chairing and supporting the

Pittsburgh Promise Foundation which has funded post-secondary education for over 11,000 Pittsburgh Public School graduates, to never saying no to signing autographs and taking selfies with fans.

Franco the legendary athlete will live forever in the history books and television archives as having carried out the greatest football play of all time. But Franco the man was even more than that. Franco Harris was his relationships; he will live forever in the hearts all who met him personally.

After hearing the stories of my fellow mourners, it was clear that if Franco Harris had never played a day’s football in his life (let alone been a Steeler of renown or pulled off the Immaculate Reception), Pittsburghers would still have lined up for hours to pay their respects. That’s the kind of man he was. His like truly will not pass our way again.

In the end, Franco took the express elevator to heaven, after living an extraordinary life of leadership

comprised of service, humility and kindness. Gone far, far too soon.

We can remember him and honor his legacy by being servant leaders, by steadily helping our fellow man without fanfare or self-aggrandizement, and above all by caring for each other in ways large and small. In the end, that’s all that any of us really are.

Stay warm and be well, and be kind to each other and yourselves.

Due to the uncertain state of the art at the present time, this editorial on long-haul COVID reflects the views of the author and not those of the ACMS nor the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Many nights we prayed

With no proof, anyone could hear

In our hearts a hopeful song

We barely understood

Now, we are not afraid

Although we know there’s much to fear

We were moving mountains

Long before we knew we could, whoa, yes

There can be miracles

When you believe!

—from the song “When You Believe” from the Disney musical “The Prince of Egypt” (1998)) —written by Stephen Schwartz

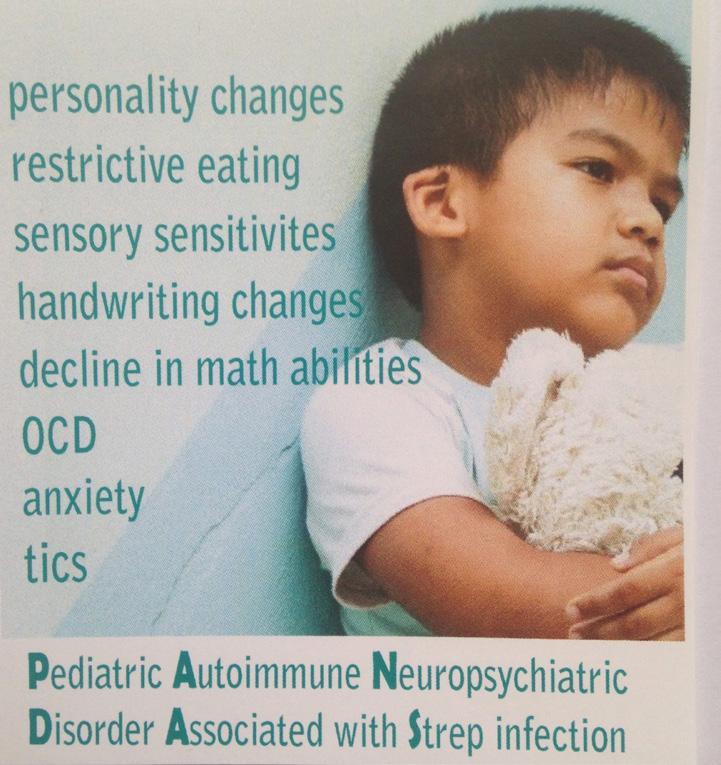

Since its iteration in 1998 by Susan Swedo and colleagues (1) at the National Institute of Mental Health, PANDAS (Pediatric

Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Strep Infection) has been the subject of great enthusiasm, healthy scientific skepticism, and academic polarization. Although widely accepted that the

syndrome comprising an abrupt onset (“thunderclap presentation”) of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, unexplainable acute anxiety, tic disorder, and/or severe food aversion, in children greater than 3 years of age and adolescents is a legitimate clinical entity, lack of a proven pathophysiologic paradigm, as well as lack of conclusive efficacy of treatment modalities (prolonged antibiotic therapy, immunesuppressants) in double-blind studies, makes management largely anecdotal. We have previously reported on the presentations (2), as well as on the work-up (3) for this entity.

of the art in unlocking the mystery of potential childhood autoimmune disorders in genetically-at-risk individuals, including those with Autism Spectrum Disorder, is still in its infancy. The reiteration of the same symptom complex in 2010 expanded to children without an antecedent streptococcal infection, PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome), has fostered inclusiveness, but has made the targeting of treatment modalities more nebulous.

Personally, as a general pediatrician who has cared for these patients with debilitating symptoms, including many on the autistic spectrum, over the past 2 dozen years of controversy, I have by default chosen the path of “belief” and aggressive management until the dawn of certainty. However, I believe this mission statement from the NIH Center for Biotechnology Information (4) should be our guide:

As with any condition under scrutiny, there are staunch supporters and there are detractors. The state

“Given the severe and debilitating nature of the symptoms and clear effects on family and child functioning, identification of evidence-based, effective therapies and understanding the incidence, prevalence, and biological basis of this syndrome are necessary. These goals can only be achieved by cross-institutional collaboration, deep clinical phenotyping from prospectively collected data

through collaborative registries, and well-conducted investigations of underlying biological mechanisms in this cohort.”

Amen.

When issues are nebulous, it is easier for inquiring mind to speculate. I think this is the case with the persistence of certain symptoms in the wake of documented and appropriately-treated COVID-19 infection: long-haul COVID (the colloquial term), otherwise known as long-dwell COVID or post-COVID syndrome.

Characteristically, the clinical presentations of this disorder are heterogeneous and the symptoms wax and wane. It is postulated that the inciting infection (regardless of the degree of severity, including asymptomatic infection) is followed by prolonged shedding of COVID-19 virus RNA (persistent antigenemia) which produces low CD8 cell counts. This cascade appears to be more common in infection with the delta strain (10.8 percent) than with the omicron strain (4.5 percent).

This diminution in CD8 (“killer T-cells” or “cytotoxic T-cells”) compromises the ability of one’s immune system to fight off intercurrent infections of all kinds. This is similar to the diminution in CD4 (“helper T-cells”) characteristic of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infections.

As many as one-third of those infected with COVID-19 develop the long-haul syndrome, and, in an unfortunate 10 percent of them, the symptoms persist beyond one year. The distribution of complaints is consistent:

Fatigue, especially following exertion: 33 percent Brain Fog (a common feature reported by children with PANS): 30 percent Lability of Mood (beyond what would be anticipated in a teenager): 16 percent

Myalgias, especially in those with a positive HLA-B27 profile, associated with immunologic dysfunction: 20 percent

Shortness of Breath: 28 percent Neuropathy, especially peripheral neuropathy with burning as a cardinal symptom: 20 percent Tachycardia, including classic POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome): 18 percent Gastrointestinal symptoms, both upper and lower tract: 44 percent Chronic loss of taste and smell (> 9 months): 5 percent

Note: Anxiety is widespread and is difficult to differentiate as a symptom of the causative disturbance versus a consequence of the frustration surrounding a protracted condition with no solid cure to date. The “thunderclap presentation” of irrational anxiety and severe obsessive-compulsive features characteristic of PANDAS/PANS has been reported in only a small handful of long-haulers.

The scientific literature has documented an increased incidence of the onset of Type 1 Diabetes in the wake of COVID-19 infection.(5) A report hot off the presses in the Journal of the American Medical Association highlights a nationwide increase in the volume of adolescent and young adult patients requiring services for eating disorders since the onset of the pandemic (6); it is noteworthy

that anorexia with food aversion is a cardinal feature of PANDAS/PANS.

The pathophysiology of longhaul COVID had been the subject of intense research efforts for the past 1½ years. Similar to that of PANS, the mechanism that is coming to light involves persistent shedding of COVID RNA which targets circulating monocytes (which have the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier}; the stimulation of inflammatory cytokines--any of a number of substances, such as interferon, interleukin, and growth factors, which have an affect on other cells of the immune system---causes derangement of function and can disrupt the blood-brain barrier.

The targets of this “cytokine storm” are the cytotoxic T-cells (CD8 cells) which are generally diminished, thereby compromising the body’s ability to ward off other infections, especially the viral infections which remain dormant (but capable of reactivation) in the human body for life: EpsteinBarr virus, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes simplex virus, Varicella-Zoster virus. Some believe that Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease bacterium, should also be in this category.

The evolution of knowledge seems to be following in the footsteps of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and research has been spearheaded by immunopathologists, notably those who participated in that epidemic in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Clinics for the overall assessment of adults and children are populating the map, especially in the greater Pittsburgh area.

Select research groups are recruiting subjects for investigations by

Continued on Page 10

multidisciplinary teams to expedite the accumulation of data; one such center at UCSF is developing a profile of the inflammatory cytokines which serve as the “fingerprints” of long-haul COVID (the so-called Long-hauler Index). This parameter, along with CD8 levels, can be monitored to gauge the status of recovery and success of therapy. “We are writing papers as fast as we can!” reassures head researcher Bruce Patterson of the Chronic COVID Treatment Center (www. covidlonghaulers.com); fortunately, the technology of today allows rapid publication of results.

The COVID research community is bent on not falling prey to the same prejudice that hampered understanding of other conditions (fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome) just because the etiologies are not clearly understood and therefore are disregarded as “psychosomatic.”

Questions loom: How does an individual become a long-hauler? (Allergic individuals seem to be more at risk for any potential autoimmune process). Are we treating acute severe COVID infection aggressively enough and long enough to reverse the consequential immune dysregulation? Are we adequately boosting the immune system surrounding infection and treating potential comorbidities like Vitamin D deficiency, Vitamin B12 deficiency, and dysbiosis? The configuration of the gastrointestinal microbiome has been found to influence the likelihood of the development of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in a genetically-susceptible individual(7); perhaps, other random epigenetic factors may be at play.

If we use the recommendations currently in place for managing PANS, immune modulation is paramount. Only severe COVID-19 infections or cases in individuals at high risk for progression (elderly, immunocompromised, pre-existing conditions) require an antiviral medication like Paxlovid; the milder or subclinical infections which predominantly trigger the long-haul complications are not candidates for the same antiviral therapies. The issue is not inhibiting COVID-19 virus replication in the acute stage, but the undetectable persistence of the virus and its chaotic repercussions on a vulnerable immune system. It is not known whether antiviral therapy can inhibit persistent viral shedding when long-haul symptoms are first appreciated, especially in children. Vigilance for reactivation of previous infection, as mentioned above, is essential.

As concrete immune-modulating recommendations are being formulated, researchers have posited that measures like oral steroids and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) may play a role. A course of steroids--systemic, then oral for a prolonged period, is the mainstay of management for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C);a complication of COVID with pathologic features similar to Kawasaki disease, another condition requiring immune modulation (IVIG, high-dose systemic steroids) to quiet a “turncoat” immune system. While the etiology of Kawasaki disease remains elusive after decades of worldwide investigation, it has nonetheless served as a prototype for managing MIS-C.

The conviction by the experts (unpublished recommendations) is that low-dose oral steroids (a dose as low as 5 mg twice per day) is superior to the conventional high dose of 30 mg twice per day with a taper, and will emerge as the standard treatment of choice for patients with long-haul COVID, following in the footsteps of experience with MIS-C, Kawasaki disease, and PANS. IVIG will likely be indicated if relapses occur in spite of oral steroid therapy. Immune boosting will continue to be an important adjunct. Supporting the mitochondria and the complex immune system in general during these periods of oxidative stress surrounding treatment is crucial to success. Dr. Richard Frye, a researcher on mitochondrial dysfunction and autism spectrum disorder, presents this caveat:

“You need to prepare the body for treatment to get a good response. If there is not a good response you might need to take a close look at other factors.”

Specifically, this involves treating or suppressing reactivated co-infections. The waters can become quite murky, especially with the added burden of managing the various specific somatic complaints, especially anxiety.

Recommendations regarding duration of these treatments will be a work in process. One obfuscating factor in judging the efficacy of any therapy is that the symptoms relevant to the immune system can be spontaneously reversible over time due to the principle of “tolerance.” This was highlighted by a recent study in the Lancet which showed that, although there was no effect of coenzyme Q10

on patients with long-haul COVID (essentially ruling out mitochondrial dysfunction as its primary cause), there was significant spontaneous remission of symptoms in both the study and the placebo groups after 20 weeks of observation. (8)

Preventing infection by full vaccination is the only bona fide way of eliminating this scourge, which 67 percent of adult patients have reported affects performing the activities of daily living (ADLs). Vaccination given after identification of infection by a positive test can accomplish only a modest reduction (15 percent) in the risk of developing the sequela.

No two long-haulers are alike. Everybody agrees that there is no “magic bullet.” My experience with PANDAS/ PANS in children and the love and devotion of their parents has taught me one thing quite well:

There can be miracles

When you believe

And as the old song goes: “When the odds are saying you’ll never win, that’s when you’ve gotta have heart”

The author wishes to thank Dr. Ned Ketyer for his editorial assistance, as well as Diana Pohlman, Executive Director of the PANDAS Network--a national nonprofit representing children afflicted by PANDAS and PANS---for her guidance on current research regarding long-haul COVID.

1. Swedo, SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, et al: Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections: Clinical Description of the First 50 Cases. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(2):264-271

2. Kristi Wees, MSc and Anthony L Kovatch, MD: PANDAS: Strep’s Enduring Threat to the Brain. http://www.thepediablog. com/2018/01/11/mind-on-the-run-41/ http://www.thepediablog. com/2018/01/12/mind-on-the-run-41/

3. Kristi Wees, MSc and Anthony L Kovatch, MD: PANDAS : A Diagnostic Conundrum. http://www.thepediablog. com/2018/04/04/mind-on-the-run-46/ http://www.thepediablog. com/2018/04/05/mind-on-the-run-47/

4. Colin Wilbur, MD. Et al: PANDAS/ PANS in Childhood: Controversies and Evidence. Paediatric Child Health 2019 May; 24 (2): 85-91

5. Ellen K. Kendall, BA1; Veronica R. Olaker, BS1; David C. Kaelber, MD, PhD2; et al: Association of SARSCoV-2 Infection With New-Onset Type 1 Diabetes Among Pediatric Patients From 2020 to 2021 JAMA Network Open. 2022; 5(9):e2233014 September 23, 2022

6. Sydney M Hartman-Munick, et al: Association of the COVID-19 Pandemic With Adolescent and Young Adult Eating Disorder Care Volume. JAMA Pediatrics, November 8, 2022

7. Joseph C Kovatch, DO: “Epigenetics: The Microbiome and Diabetes” Dr Kovatch is currently a resident at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, PA. http://www. thepediablog.com/2017/09/07/ epigenetics-the-microbiome/

8. Hansen, Kristoffer S, et al: Highdose Coenzyme Q1 Therapy Versus Placebo in Patients with Post COVID-19 Condition: A Randomized, Phase 2, Crossover Trial. Lancet: November 02, 2022

“If you want a friend in Washington, get a dog.”

—President Harry S. Truman

He sits next to my desk watching me. Always watching, never making a sound, even when I greet him each day, or ask his opinion. He is my silent sentinel. He is an artist’s recreation of my favorite dog Flaps (Fig. 1). The real Flaps (Fig. 2), who died in 1981, was a most gentle creature who was devoted to me and to my sons. Flaps tolerated all the things young children often do to pets, and when he’d had enough, he would get up and go into another room. After he was gone, I had often joked that I should have taken his body to a taxidermist. However, that was too macabre. Thirty years later, while visiting our in-laws in Boca Raton I happened upon an art store1 in the Town Center Mall that was dedicated to whimsical portrayal of animals. They had a display of papier-mâché animals with a poster telling the public that they could create life-sized versions of our favorite pets. I negotiated a price, sent pictures and details of Flaps’ size and six weeks later my silent sentinel arrived in a big box. From a distance he looks like a real dog. He even surprised my granddaughters when they first saw him.

My wife, oldest son Marc, and I met Flaps in 1970 while I was in the Air Force, when I went to do an insurance medical examination on a man who bred Weimaraners. He wanted to sell me a dog, but I wasn’t interested in that breed. “Well,” he said, “I have another dog you might be interested in.” He showed us six-month-old Flaps, a Schnauzer – Sheepdog mix, who greeted us with a wagging tail and his winning “smile”. It was love at first sight. I had recently earned my private pilot’s license and with his floppy ears, we all agreed to name him Flaps (who incidentally liked flying with me in small planes).

My silent sentinel Flaps has many advantages over the real Flaps. He doesn’t bark; he doesn’t shed; he doesn’t chew; he doesn’t need to be fed; he doesn’t need “house training”; he doesn’t need to be walked; and, of course, he will never need to be taken to the veterinarian. On the other hand, he will never greet me with his wagging tail or his smile. And he can’t be cuddled.

Anthropologists estimate that our relationships with dogs began around 40,000 years ago during the Ice Age when a fearless, but friendly breed of wolves began living with our ancestors. Ice Age humans generated a surplus of meat and bones after a successful

hunt. The wolves soon became trained participants in the hunt and were quickly adopted into the human tribes. In exchange for unconditional love, all they asked of us was that we feed them and treat them kindly2. In addition to unconditional love (see Truman’s quote above), they offer us loyalty, a modicum of protection, a willingness to be helpful (e.g., service and comfort dogs), and a willingness to please their humans.

I have owned seven dogs throughout the years. This has given me the opportunity to make some observations on their behavior that I’d like to share. First, their “smile” (Fig. 2). Dogs, like most canids share with primates well-developed facial muscles that allow them to show their emotions – joy, sadness, fear, anger, guilt. (Cats, the other popular companion animals, cannot and just stare at us.)

Dogs are pack animals. In the ideal situation the dog sees his/her owner as the leader of the pack. Years ago, my son selected a very active Golden Retriever puppy, who turned out to be the Alpha Dog of her litter. We soon discovered that she resisted being trained. So, how does one identify the Alpha Dog? Within any pack, there is a hierarchy. The Alpha (male or female) is often the most active and can be seen leading the pack in their activities. Below the Alpha there is a caste system of High and Low dogs. High dogs hold their heads up, with their ears raised. Their tails, important for non-verbal communication, are also held high and readily wag. Low dogs, on the other hand, keep their heads low. Their tails are down, and often between their hind legs.

Dogs communicate through their bark as well as through their tail. The tone of the bark is a function of their size, not their emotions. When encountering a barking dog, the tail is the key to interpreting what the bark means. A barking dog with its tail wagging usually indicates a friendly greeting. The dog is happy to see you. Occasionally, because dogs are funloving, a fierce bark with a wagging tail can be interpreted as, “I bet I scared you. Ha ha!” On the other hand, a barking dog with its ears raised (and perhaps piloerection) and a tail pointing straight out without wagging is angry and is saying, “Keep out of my turf.” Finally, a barking dog with its tail between its legs is afraid of the intrusion.

My neighborhood in Mt. Lebanon is a favorite area for walkers and runners because it is nearly completely flat. As a result, we have many dog walkers. Over the years I’ve been able to observe canine social interactions. Most of the dog walkers have only one animal, some have two. In most cases, when two single dogs meet, they go wild seeing another of their kind. The barking and tail wagging suggest they are saying, “Hey, wanna play? Huh? Let’s have some fun.” On the other hand, when one dog meets a pair of dogs, the single dog does the “dance” described above, while the pair stay calm, as if to say, “Oh well, it’s just another dog.” My theory is that because dogs are social animals, they really like having another canine partner with whom they can interact when their humans are not around. (We go off to work or to school for a good part of the day). In the years

before we moved to Pittsburgh, we had two dogs, who kept each other company (and usually out of trouble).

Dogs are also capable of mourning the loss of an owner or companion dog. This was illustrated in the 2009 movie “Hachi”, a story about an Akita. In the movie, the dog accompanied his owner every day to the commuter train station to see him off to work. The dog would return in the afternoon to greet his owner upon his return. When the owner died at work, the dog would still go to the station every day in the hope of greeting his returning owner. According to the story, this continued for ten years until the dog died at the station while waiting.

My family and I observed this behavior in Flaps when his long-time companion, Murray died. Murray was a Beagle – Doberman mix, whom I rescued as a puppy from an abusive household. Murray was a low dog, whom I named because of her uncanny resemblance to a medical school classmate of mine who was a “sad sack”. The only time I saw her “smile” was when we entered her in a contest for saddest dog. She lost. After she was gone, Flaps went from room to room in our house looking for his companion. He wouldn’t eat for two days, during which time he would look at me sadly as if to ask, “Where is she?” In response, I’d cuddle him and gently say, “She’s gone (to the ’Great Fire Hydrant in the Sky’).

Flaps also had a paternal sense of duty. Murray, after giving birth to a litter of his puppies, initially refused to nurse them and would walk away from them. Flaps would pick the puppies up

Continued on Page 14

From Page 13

and drop them on Murray to nurse. To assure that she wouldn’t get up again, he put one of his front paws on her. She got the message.

Tradition holds that cats and dogs don’t get along and fight like – well, cats and dogs. Two weeks before Christmas, the year that Murray died, our doorbell rang. When my younger son, accompanied by Flaps opened the door, they were greeted, not by a person, but by a gray kitten that had been left on our porch. I knew Flaps had a kind personality, but I had no idea how he would respond to a cat. His first reaction was to lick the kitten. He welcomed his new playmate with a wag of his tail. During the time we had the cat, they only had two negative interactions. The first occurred on the first day at feeding time – the big event in Flaps’ day. We fed the kitten first and then put out Flaps’ bowl. Before he came charging in to eat, the kitten began sniffing at the dog food. When Flaps saw the kitten he stopped abruptly, walked up to her, and gently pushed her away from his bowl before gobbling down his dinner.

The second incident occurred several days later. Any time Flaps heard my voice, he would wag his tail. That evening he was lying in our den and the kitten was lying behind him.

On hearing my voice, his tail began wagging. The kitten, on seeing this object moving did what most cats would do and began swiping at his tail with her front paws. Eventually, she skewered the tail with her claws. Flaps let out a yelp and jumped up to see what was tormenting him. He was surprised to see that the source of his discomfort was his little buddy. The kitten was equally surprised to find that her “toy” was attached to a large dog. They stared at each other for a few seconds before Flaps gave the kitten a lick and then they both curled up together and fell asleep.

So that’s the background story of my Silent Sentinel. Whenever I sit down at my computer, I greet him. And when I leave, my final words are, “See you later old friend.” He doesn’t respond as he continues his vigil. And yes, I do know he’s not a real dog.

1. Pavo Real, 6000 Glades Road, Boca Raton, Fl 33431 (www.pavoreal.com)

2. Norman T. Want Dogs of war? Dogs are love! Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Apr 21, 2022.

Dr.Daffner is a retired radiologist, who practiced at Allegheny General Hospital for over 30 years. He is Emeritus Clinical Professor of Radiology at Temple University School of Medicine.

We are fortunate to have over 2,000 local physicians, residents, and students as part of the ACMS membership. We are grateful for the range of expertise that exists within our membership community and we want to help you share that

5837 Solway Squirrel Hill

5837 Solway Squirrel Hill

The 1944 classic psychological thriller film Gaslight tells the story of the fictional character Paula and her new husband Gregory, who goes about the task of isolating her and leading her to believe that she is insane. He accomplishes this by dimming and brightening the gas lights in their house and then insisting that she had been imagining it. The objective was to compromise her sense of self and environment, leading her to accept his distorted reality and doubt her sanity. In more recent terminology, “gaslighting” is a colloquial term used to describe the manipulative strategies of abusive people in intimate interpersonal and institutional relationships. (1)

Although gaslighting has been considered a psychological syndrome, in many ways it is fundamentally a social phenomenon. Although engaging in abusive mental manipulation certainly has aspects of psychological interplay, it occurs because of social inequities. Perpetrators of gaslighting utilize gender-based stereotypes, social inequalities, and institutional vulnerabilities against their victims. Gaslighting tactics can damage the victim’s sense of reality, independence, identity, and social support. (2)

Gaslighting occurs within powerimbalanced personal relationships. Although often recognized in domestic violence situations, it can occur in other types of interpersonal relationships.

Barton and Whitehead devised the term ‘gaslighting’ in a 1969 Lancet article that conceptualized involuntary hospitalization as a form of abuse. (3) The term was later popularized in a 2007 book by psychotherapist Robin Stern in which she explained gaslighting as a phenomenon of mutual participation between perpetrator and victim. Although Stern wrote that gaslighting was gender-neutral, her case studies all involved a male partner as the gaslighter and a female as the target. The best measurable data currently available offers evidence that gaslighting is a common characteristic of domestic violence. (4)

Whereas, psychological theories suggest that gaslighting occurs in an isolated dyad, the sociologic hypothesis assumes a more complicated etiology, with the primary origin evolving from power imbalances, and a secondary requirement of a close interpersonal or institutional relationship binding the victim and perpetrator. Consequently, the victim cannot readily or easily dismiss the gaslighting efforts. Trust and coercive interpersonal tactics bind the victim to the perpetrator. The sociologic hypothesis of gaslighting suggests that it exists in the presence of pervasive inequalities of allocation of social, political, or economic power. (2)

The social concept of gaslighting in the context of health care also reflects

a broad power dynamic and institutional inequality. Medical gaslighting is a symptom of a larger problem within health care, which being the continued privilege of biomedical expertise overriding and sometimes invalidating the interpretation of actual individual experiences. (1)

Central to the relationship of gaslighting and health care is the concept of ‘biopower’ established by French philosopher Michael Foucault. Biopower refers to the regulatory technologies of institutions used to govern human life. He describes the ways that health messaging promotes a specific and idealized image of health and of the body in which people conform and aspire to achieve. Medical gaslighting can be seen as an extension of ‘biopower’ within health care. An example might include a health care provider’s premature interpretation of a patient’s physical symptom as being solely of supratentorial etiology. (5)

Philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler authored the concept of ‘performativity’ as the process by which social norms are constructed through repetitive informal practices. Performativity suggests that social reality is not canon, but is instead continually created and reinforced through language, gesture, and symbolic social cues. Butler also wrote of performativity and autonomy as being ‘code-constructed’ in

the therapeutic relationship. This concept has applicability in the doctor-patient relationship, in the sense that biopower as established by institutional norms is maintained through performativity. (6)

In contemplating the interactions between patient and doctor during a clinical appointment, the social norms that might allow for medical gaslighting now become clearer. The doctor begins the appointment typically by asking in some manner what is the patient’s concern. At that point, the doctor’s power is briefly suspended, allowing the patient to bring forth his or her personal observations. The doctor, representing the ‘biopower’ of the institution of medicine, is empowered afterwards to pronounce what is real and what is not. Operating from the hierarchical construct that science is the final verdict, the doctor can make an interpretive pronouncement of reality for which the patient has limited options to refute. In the context of Butler’s research, this relationship is performative. Within a performative interaction, there is opportunity for resistance, which would not be without potential negative consequence to the patient, depending upon the doctor’s reaction. Within these performative interactions, resistance is uncommon regardless of the patient’s individual experiences, considering that the nature of the visit involves the doctor establishing the questions, the timeline, the sequence of events, and the examination. At that point, the patient has limited paths for resistance. (7)

Although the terminology of medical gaslighting is contemporary, it is not a new concern, as claims of invalidation, dismissal, and disregard of patient health concerns, particularly of female, ethnic minority, LGBTQ+, and underprivileged patients, are of long-standing concern.

Gaslighting is a function of power dynamics, and medical gaslighting is an example of how power dynamics operate within the health care institution. Butler’s theory of performativity allows for renewed insight into the ways that the biopower of modern medicine is reified as the authority in healthcare relationships, yet her research also provides an opportunity for understanding when and how these relationship dynamics should be challenged and balanced by individual experiences. In addition, the applicability of these insights can apply to other potential examples of gaslighting within the health care community, as in the relationships between administrators and employees, supervisors and supervisees, physicians and nurses, and medical specialists and primary care providers. (8) In conclusion, gaslighting is unique, and is differentiated from other forms of interpersonal misconduct within health care, as it does not involve public humiliation, specific threats, or obvious insults. The destructive effects of all forms of gaslighting can be malignantly devastating to all aspects of life. Gaslighting is intrinsically subtle and intimate. These characteristics make even more dangerous.

(1) Sweet, P. L. (2019). The sociology of gaslighting. American Sociological Review, 84(5), 851-875.

(2) Ferraro, Kathleen J. 2006. Neither Angels nor Demons: Women, Crime, and Victimization. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

(3) Barton, Russell, and J. A. Whitehead. 1969. “The GasLight Phenomenon.” The Lancet 293(7608):1258

(4) Stern, Robin. [2007] 2018. The Gaslight Effect: How to Spot and Survive the Hidden Manipulation Others Use to Control Your Life. New York: Harmony Books

(5) Foucault, M. (1998). The history of sexuality--The will to knowledge, Volume 1, 1976. Trans. Robert Hurley. Penguin.

(6) Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

(7) Sebring, J. C. H. Towards a sociological understanding of medical gaslighting in western health care. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2021; 00:1–14.

(8) Fraser, S. The toxic power dynamics of gaslighting in medicine. Can. Fam. Physician Med. Fam. Can. 2021, 67, 367–368

The mission of Strong Women, Strong Girls is: “To empower girls to imagine a broader future through a curriculum grounded on female role models delivered by college women mentors, who are themselves mentored by professional women ”

Outcomes: For the 2021-2022 school year, this program served 576 girls with the support of 279 college mentors. They provided programming at 38 sites across Allegheny County, including 30 schools (public, private, and charter) and eight community centers.

The ultimate goal of the SWSG program is to champion the aspirations and potential of girls through increased confidence, positive relationships, and socio-emotional support. Mentees take surveys with SWSG in the Fall and Spring semesters. Surveys are based on the 6Cs of Positive Youth Development (Caring, Character, Confidence, Competence, Contribution, and Connection), which is a widely recognized research framework to assess children ’ s development. Mentees positively endorsed many items on the survey, and some of the highlights include:

• 98% of mentees think that they can learn from people who are different from them

• 100% of mentees indicated a sense of belonging at SWSG and indicated they care about how other mentees and mentors in the program feel (evidence of belonging and positive relationships within the program); believe that doing things to help others is important to them; they stand up for what they believe in; and feel proud of their talents that are different from others.

• 92% of mentees enjoyed school some or all of the time. To

Founded in 1960, the Allegheny County Medical Society Foundation has extended the reach of physicians into the community through grant giving to local organizations.

The mission of the Foundation is: A Advancing Wellness by confronting Social Determinants and Health Disparities. This mission works to fulfill an overall vision of a healthy and safe Allegheny County.

Throughout the ups and downs of the past few years, the Foundation’s work has become even more important in supporting local non-profit organizations.

The desire to give back to the community is an inherent trait of those who become physicians. In past year ’s the ACMS has hosted an annual gala to help raise funds to support the Foundation. Due to COVID-19, just like many other organizations, the ACMS had to forego the inperson gathering. While we look forward to hosting a Foundation fundraising event in the near future, the work of the Foundation continues on. Please consider how you can personally help support the Foundation and, in turn, continue to support a healthy region.

Contact the ACMS team to learn more about how your organization can help support the ACMS Foundation.

As physicians, you know that it takes a village to keep the community healthy and safe. Please consider a donation to the Allegheny County Medical Society Foundation.

Your donation will help the Foundation fund local non-profits in future grant cycles, and will help further the mission of the ACMS Foundation.

Donations can be mailed to: ACMS Foundation

850 Ridge Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15212

Scan this QR Code to Donate via Qgiv:

The Pittsburgh Ophthalmology Society, under the leadership of President Marshall W. Stafford, M.D. is pleased to announce the 58th Annual Meeting and the 43rd Meeting for Ophthalmic Personnel is scheduled for March 10, 2023. Both meetings will take place at the Omni William Penn Hotel in Pittsburgh, PA. We look forward to offering an engaging and robust experience for attendees and exhibitors in a welcoming environment in which to learn and gather.

Registration begins January 26, 2023 with POS members and ophthalmic personnel attendees receiving information by email and mail.

The Society

is honored to welcome Leon W. Herndon, Jr., MD, as the 42nd Annual Harvey E. Thorpe Lecturer. He is a Professor of Ophthalmology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina. He is a member of the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) and was

a member of the first class of the Leadership Development Program. He has authored over 100 peer-reviewed papers, lectured nationally and internationally, and has participated in several research projects related to glaucoma. He currently serves as Chief of the Glaucoma Division at the Duke University Eye Center where he has trained 84 clinical fellows. Dr. Herndon has been recognized for his service in the community by receiving the Senior Achievement Award from the AAO and the Dedicated Humanitarian Service Award. He is the recipient of the Distinguished Medical Alumnus Award from the UNC School of Medicine and was the Surgery Day Lecturer at the American Glaucoma Society Annual Meeting in 2019. He was named to the 2021 Newsweek America’s Best Eye Doctors list (#27). He is founder of the North Carolina Glaucoma Club, and the chair of the Glaucoma Clinical Committee of the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons as well as Vice President of the American Glaucoma Society.

Participating distinguished guest faculty include:

Philip Custer, MD, FACS— Professor, Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, John F. Hardesty, MD, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Tom Oetting, MS, MD—Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Iowa; Chief of Ophthalmology at the Iowa City VAMC Iowa City, IA

Michelle Pineda, MBA Risk Management Specialist, Ophthalmic Mutual Insurance Company (OMIC).

José Alain-Sahel, MD— Distinguished Professor and Chairman; The Eye and Ear Endowed Chair

Department of Ophthalmology; Director, UPMC Eye Center University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Pittsburgh, PA. Dr. Sahel is a clinicianscientist conducting research on vision restoration focusing on cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying retinal degeneration, and development of treatments for currently untreatable retinal diseases. He co-authored over 660 peer-reviewed articles and 40 patents. Dr. Sahel is recipient of numerous awards including the Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB) Trustee Award, Alcon Research Institute Award for Excellence in Vision Research, Grand Prix NRJNeurosciences-Institut de France, Foundation Fighting Blindness

Llura Liggett Gund Award, CharpakDubousset Award, Médaille Grand Vermeil, Ville de Paris. He was elected to the: Academia Ophthalmologica Internationalis, Académie des Sciences-Institut de France, German National Academy of Sciences

Leopoldina, National Academy of Technologies of France, Association of American Physicians and American

Ophthalmology Society. Dr. Sahel is Honoris Causa doctorate of University of Geneva and held the Technological Innovation Chair at the Collège de France (2015-2016). He is a member of several Editorial Scientific Advisory Boards, including Science Translational Medicine.

The 43rd Annual Meeting for Ophthalmic Personnel, presented by the Pittsburgh Ophthalmology Society (POS), will run concurrently with the POS Annual Meeting Friday, March 10, 2023. Application to IJCAHPO has been submitted for attendees to earn a maximum of 7 credit hours.

For more information on the Annual meeting please visit the POS website at www.pghoph.org or contact Nadine Popovich, Administrator at npopovich@acms.org or to 412.321.5030 x110.

Course directors Pamela Rath, MD; Avni Vyas, MD; Cari Lyle, MD; and Zachary Nadler, MD, PhD; have prepared an exceptional educational offering for Ophthalmic staff.

Highlights of the course include presentations on Glaucoma, Cornea, Oculoplastic, and a refractive session to include a hands-on component. The conference provides exceptional educational opportunities for ophthalmic personnel in and around the region and continually attracts well-respected local faculty, who present relevant and quality instruction through numerous breakout sessions. Thank you to POS members who accepted the invitation to present lectures.

On-line registration begins January 26, 2023, www.pghoph.org. Contact Nadine Popovich, administrator, for details and more information at npopovich@acms.org.

The 31st Annual Clinical Update in Geriatric Medicine will be held virtually on March 23 - 24, 2023. Presented by the Pennsylvania Geriatrics Society − Western Division (PAGS-WD), UPMC/ University of Pittsburgh Aging Institute and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Center for Continuing Education in Health Science, the conference provides an evidencebased approach to help clinicians take exceptional care of elderly patients. The virtual offering includes an outstanding agenda of lectures and panel discussions, including live question-and-answer sessions, vendor halls and opportunities to engage in conversations with speakers, exhibitors, and fellow attendees.

With the fastest-growing segment of the population comprised of individuals more than 85 years of age, this conference is a premier educational resource for health care professionals involved in the direct care of older people. As the recipient of the American Geriatrics Society State Achievement Award for Innovative Educational Programming, the Clinical Update attracts prominent national and international lecturers and nationally renowned local faculty. Continuing Medical Education credits are available to participants.

Back by popular demand, a Geriatric Cardiology Expert Panel will be part of the agenda. Featured faculty include Daniel Forman, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; Chair, Geriatric Cardiology, UPMC, Director, Cardiac Rehabilitation VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, Deirdre O’Neill, MD, MSc, FRCPC, Assistant Professor, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine University of Alberta, Alberta, Canada, and Eiran Z. Gorodeski, MD, MPH, FACC, FHFSA, Director of the Advanced Heart Failure & Transplant Center, Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, University Hospitals Health System, Section Head of advanced heart failure in the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, and Professor of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University. All three physicians will participate in a live, rapid-fire question-and-answer session.

To view the complete conference agenda and details on registration, please visit: https://dom.pitt.edu/ ugm/. Registration begins late January. Members of the PAGS-WD receive a discount when registering. To check on your membership status, please contact Eileen Taylor at etaylor@acms.org

Several e-invoices have been mailed to members. Contact Nadine Popovich, administrator, to confirm the status of your membership or to receive an invoice. Membership dues support the society’s educational programs throughout the year. Ms. Popovich may be reached by email: npopovich@acms.org or by phone: 412.321.5030 x110.

l to r: S. Taylor, MD, FACS (PAO President,); M. Stafford, MD (POS President); J. Knickelbein, MD, PhD; S. Srivastava, MD (Guest Faculty); M. Errera, MD; A. Eller, MD; S. Fox, DO; J. Brown, MD (POS Secretary); L. Tiedemann, MD

A record crowd attended the December 1st POS meeting held at the Allegheny Room of The Riversto welcome guest faculty Sunil Srivastava, MD, Fellowship Director, Vitreo-Retinal Fellowships, Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland, OH. Thank you to Jared Knickelbein, MD, PhD for inviting Dr. Srivastava and to the following co-sponsors of the program: BioTissue, DORC, and Genentech.

He presented two interesting lectures: Surgery in the Uveitis - How to maximize outcomes and Uveitis Update 2023, each of which stimulated an excellent question and answer session with the audience.

Matthew Sommers, MD, Resident at the University of Pittsburgh Eye Center, presented an interesting case for commentary by Dr. Srivastava.

The ACMS is pleased to announce that Dr. Matthew B. Straka has been elected as President for the 2023 membership year. Dr. Matthew Straka is an otolaryngologist-head & neck surgeon who is a native of the Pittsburgh region and returned for residency at UPMC. He went on to join into practice with his father, Dr. John Straka. After almost 20 years of private practice working in a single specialty group covering West Penn Hospital, Heritage Valley Sewickley, and St. Clair Hospital, he has more recently navigated the transition to employment within the Allegheny Health Network system. He provides comprehensive otolaryngology care with expertise in endoscopic sinus and skull base surgery, and currently serves as surgery department chairman at Heritage Valley Sewickley. His wife, Dr. Michelle Straka, is a women’s imaging radiologist with Weinstein Imaging Associates.

As President of the Allegheny County Medical Society, Dr. Straka’s primary objective is to help physicians of Allegheny County recognize the value of membership through local advocacy efforts. This includes tackling current and future issues that affect the ability of physicians to provide efficient and thorough care for patients. Dr. Straka says, “The issues we face, as physicians, continue to change as health care evolves and we need to ensure our medical society is here to support our currents needs, and anticipatory and proactive in anticipating the things that will come our way in the future. It’s often not easy to measure what return you get on your membership dues, but I can say for certain that the ACMS can accomplish more for our physicians, and the patients they serve, with robust membership.”

Sara Hussey, ACMS Executive Director says: “The Allegheny County Medical Society is excited to have Dr. Matthew Straka leading the helm as the President of the Board of Directors in 2023. Dr. Straka has a passion for membership engagement and local physician advocacy. As ACMS President, he will work closely with the ACMS team and the executive

committee on increasing the visibility of the medical society and its members. Dr. Straka will also have the support of an energized Board of Directors, which includes a blend of knowledgeable seasoned physicians, as well as several newly elected and energetic early career physicians. We look forward to an exciting and successful year under Dr. Straka’s leadership.”

In the United States, pain is one of the most common reasons that adults seek medical care.1 Acute pain is typically sudden in onset and may occur from injury, trauma or medical treatments such as surgery.2 Acute pain is normally time-limited, usually lasting for less than one month. In contrast, chronic pain is defined as pain that typically lasts more than three months or past the time of normal tissue healing.3 Up to 15 percent of adults in the United States have current localized or widespread chronic pain that has persisted for at least three months, and the overall prevalence of common musculoskeletal pain conditions such as arthritis, headaches or back pain has been estimated at 43 percent of adults.4

Chronic pain can have clinical, psychological, and social consequences, including limitations in activities, decreased mental health, loss of work time or productivity, social stigma, and reduced quality of life.5,6 Chronic pain often cooccurs with behavioral health conditions, including mental health disorders and substance abuse disorders. Patients with chronic pain are also at increased risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors.6 Therefore, it is imperative that health care providers have the training, education, guidance and resources to provide appropriate, holistic, and compassionate care for a patient in pain.

Prescription medications are an integral part of improving function and quality of life for patients with chronic pain. Opioid agents are frequently prescribed and can be an essential component of pain management, but there is potential risk and evidence of long-term benefit is limited.6-8 In response to the opioid crisis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released “Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain” in 2016.5 This guideline included twelve recommendations for prescribing opioids for chronic pain based on best-available evidence at that time. Publication of this guideline resulted in accelerated reductions in potentially highrisk and overall prescribing of opioids, as well as with an increase in the prescribing of non-opioid medications for chronic pain.7 However, several misapplications of this guideline also occurred, including rigid applications of dosing and duration thresholds by insurers and pharmacies as well as rapid opioid tapers and abrupt discontinuation without collaboration with patients. Such inflexible interpretations contributed to undertreated and untreated pain, acute withdrawal symptoms, and psychological distress of patient with pain.7 These unintended effects drew attention to the need for an updated guideline that reinforced the importance of flexible, individualized, and patient-centered care. As a result, the “CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain – United States, 2022” were developed

and released on November 4, 2022.6 The document is publicly available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/rr/ rr7103a1.htm.

The 2022 guideline is intended for health care providers who prescribe opioids for adult patients with pain.6 The document expands guidance for acute pain as well as for subacute pain (lasting one to three months), in addition to updating evidence for the treatment of chronic pain. In this update, recommendations on use of opioids for acute pain and on tapering opioids for patients already receiving opioid therapy have been significantly expanded. The recommendations made by the guideline are meant to apply to patients in outpatient settings such as clinician offices, clinics, and urgent care centers as well as to patients being discharged from hospitals, emergency departments and other facilities, but not to patients who are actively hospitalized or in an emergency department or other observational setting from which they might be admitted to inpatient care.6

The guideline stresses that clinicians should consider the full range of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments for a patient in pain.6 Noninvasive, non-pharmacologic treatments such as exercise and psychological therapies have been associated with improvements in both pain and function, which can be sustained after treatment and are not associated with serious harms. Non-opioid medications, such as the

Continued on Page 26

From Page 27

selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, pregabalin and gabapentin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are all associated with small to moderate improvements in certain types of chronic pain and function, but there are classspecific adverse effects for each agent that must be considered. However, this does not imply that patients are required to sequentially “fail” all non-pharmacologic and non-opioid therapies before proceeding to opioid therapy.7 Further, the guideline acknowledges that there is an important role for opioid therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe acute pain when NSAIDs and other therapies are contraindicated or are unlikely to sufficiently control pain.7

The guideline makes twelve voluntary recommendations and groups them into the following four domains:6

1. Determining whether to initiate opioids for pain

2. Selecting opioids and determining opioid doses

3. Deciding the duration of initial opioid prescriptions and conducting follow-up

4. Assessing risk and addressing potential harms of opioid use

The guideline also highlight the addition of five new guiding principles to inform implementation of the recommendations and support appropriate, individualized care.6,7 These principles are particularly important in improving patient care and safety:9

1. Acute, subacute, and chronic pain all need to be appropriately assessed and treated, regardless of whether opioids are part of the treatment regimen.

2. The recommendations within the guideline are voluntary and are intended to support, not supplant, individualized, person-centered care. The clinician’s flexibility to meet the needs and clinical circumstances of a specific patient is of the utmost importance.

3. A multimodal and multidisciplinary approach to pain management that addresses the physical health, behavioral health, long-term services and supports the well-being of each patient is vital.

4. Special attention should be given to avoid misapplying the guideline beyond its intended use. Likewise, implementing policies purportedly derived from the guideline might lead to unintended and potentially harmful consequences for patients.

5.Clinicians, practices, health systems, and payers should all vigilantly attend to health inequities; provide culturally and linguistically appropriate communication, including communication that is accessible to persons with disabilities; and ensure access to an appropriate, affordable, diversified, coordinated, and effective nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic pain management regimen for all persons.

The guideline recommends that nonpharmacologic and non-opioid therapies are maximized as appropriate for the specific patient and condition prior to considering an opioid agent.6 Practitioners are reminded that non-opioid therapies are at least as effective as opioids for many common types of acute pain, subacute, and chronic pain. If it is determined that an opioid is indeed appropriate, clinicians should discuss with the patient the known risks and realistic benefits of opioid therapy. In patients with

subacute or chronic pain, clinicians should also work with the patient to establish treatment goals for pain and function, as well as consider how opioid therapy will be discontinued.

If opioid therapy is deemed appropriate, the guideline recommends starting with immediate-release products rather than extended-release or long-acting formulations.6 If the patient is opioidnaïve, clinicians should provide the lowest effective dosage regardless of whether the pain is acute, subacute or chronic. If the patient’s pain is subacute or chronic and opioids are to be continued, a careful evaluation should be undertaken prior to increasing the dose. Doses should not be increased above a level that is likely to yield diminishing returns in benefits relative to risks.

In a patient who has received opioid therapy for a long duration (such as for one year or more), practitioners should use caution when changing the dose.6,7 If the benefits outweigh the risks of continued opioid therapy, providers should work closely with the patient to optimize nonopioid therapies while continuing the opioid therapy. If the benefits of opioid therapy no longer outweigh the risks, other therapies should be optimized, and the opioid should be gradually tapered to lower doses in collaboration with the patient. Tapers of 10 percent per month or slower are more likely to be tolerated than rapid tapers, and in a patient who is struggling to tolerate a taper, clinicians should maximize non-opioid treatments for pain and address behavioral distress.

In individualized cases, opioids may be tapered and discontinued entirely.6 However, the guideline cautions that opioid therapy should not be discontinued abruptly

and higher doses should not be rapidly reduced unless there are warnings of an impending overdose or indications of a life-threatening issue.

If opioid therapy is deemed appropriate for the treatment of acute pain, the guideline recommends that clinicians should prescribe a quantity that is not greater than needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids.6 If opioids are required for subacute or chronic pain, the guideline recommends that practitioners evaluate the risks and benefits of opioid therapy with the patient within one to four weeks of starting opioid therapy or dose escalation. The guideline further recommends that providers regularly evaluate the benefits and risks of continued opioid therapy with the patient.

Practitioners should evaluate the risk of opioid-related harms and discuss this risk with the patient before initiating and periodically during the continuation of opioid therapy.6 Practitioners should also work with the patient to incorporate strategies to minimize risk into the treatment plan; one such strategy may be to offer naloxone.

When prescribing opioids for any type of pain, clinicians should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using the appropriate state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data.6 Prescribers and pharmacists should be especially cognizant of whether the patient is already receiving opioids or combinations of medications that would place the patient at high risk of an overdose. Specifically,

caution should be used when prescribing concurrent opioids and benzodiazepines, and the concurrent use of opioids and other central nervous system depressants should be carefully considered.

If opioids are prescribed for subacute or chronic pain, the benefits and risks of toxicology testing should be considered.6 Such testing could assess for prescribed opioids, as well as other prescribed and non-prescribed controlled substances. However, if such monitoring is used, it should not be used in a punitive manner but in the context of other clinical information to inform and improve patient care. Interpretation of the results should be supplemented with other assessments, including discussions with patients, family, and caregivers, clinical records, and PDMP data.

In a patient with opioid use disorder, practitioners should offer or arrange treatment with evidence-based medications.6 Detoxification without medications is not recommended due to an increase risk for resuming drug use, overdose, and overdose death. Clinicians should also avoid dismissing patients from care.

Multimodal therapies require coordination of many different health care providers and may not be readily available to patients in rural or underserved areas. These therapies may also be timeconsuming, slow to take effect, and costly if not reimbursed by a patient’s insurance.6,7,10

In contrast to the 2016 guideline, the 2022 guideline emphasizes general principles rather than recommending explicit doses or dosage limits of opioid therapy.7 This was done to discourage the misapplication of such thresholds as inflexible standards, but as a result, the guideline lacks specific information. The guideline does provide data related to

dosages within the supporting text, but this information is only meant to inform clinical decision-making.

The guideline expressly states that it is does not address the use of opioids when prescribed for opioid use disorder, nor does it make any specific recommendations regarding the treatment of opioid use disorder or other substance abuse disorders.6

Finally, it should be noted that the guideline specifically states that it is intended to apply to patients 18 years of age or older with pain in situations other than sickle cell disease, cancer-related pain, palliative care and end-of-life care.6,7 The appropriate management of pain in children, adolescents, and these other complex clinical situations is even less defined, and prescribers are cautioned that these recommendations should not be extrapolated to these populations.

The 2022 CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Pain makes recommendations that are based on systematic reviews of the scientific evidence.6 The guideline reflects considerations of both benefits and harms, patient and clinician values and preferences, and resource allocation. Additionally, the guideline highlights the importance of the provision of personcentered care that is built on trust between the patient and provider. Practitioners are reminded that the guideline’s recommendations should not be applied as inflexible standards across all patient populations, but instead are meant to improve communication between the clinician and patient about the benefits and risks of treatment with opioids. Ultimately, the guideline and its guiding principles are intended to be used as a clinical tool to

Continued on Page 28

From Page 29

empower clinicians and patients to make informed, individualized decision related to pain care together.

Dr. Fancher is an associate professor of pharmacy practice at Duquesne University School of Pharmacy. She also serves as a clinical pharmacy specialist in oncology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center at Passavant Hospital. She can be reached at fancherk@duq.edu or (412) 396-5485.

1. Chou R, Hartung D, Turner J, et al. Opioid Treatments for Chronic Pain. 2020. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.

2. Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. 2020. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.

3. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl. 1986;3:S1-226.

4. Hardt J, Jacobsen C, Goldberg J, Nickel R, Buchwald D. Prevalence of chronic pain in a representative sample in the United States. Pain Med. 2008;9(7):803-12. doi:10.1111/j.15264637.2008.00425.x

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1

6. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain - United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(3):1-95. doi:10.15585/ mmwr.rr7103a1

7. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. Prescribing Opioids for Pain - The New CDC Clinical Practice Guideline. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(22):2011-2013. doi:10.1056/ NEJMp2211040

8. Frieden TR, Houry D. Reducing the Risks of Relief--The CDC OpioidPrescribing Guideline. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1501-4. doi:10.1056/ NEJMp1515917

9. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines at a glance. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/ healthcare-professionals/prescribing/ guideline/at-a-glance.html . Accessed December 21, 2022.

10. The issues with the CDC guidelines on opioids for chronic pain, according to AAPM’s director. Clinical Pain Advisor. Available at http://www. clinicalpainadvisor.com/opioid-addiction/ the-issues-with-the-cdc-guidelines-onopioids-for-chronic-pain/article/524976/. Accessed December 21, 2022.

We read the series of OpEds in the ACMS Bulletin regarding abortion care with great interest. Unfortunately, they were presented on equal footing; one article espoused the scientifically informed opinion of the medical community and the other did not. This type of false equivalence undermines the widely held position of premier physician organizations in our country, that abortion is essential healthcare (see attached policy statements below). While we respect the opinions of our colleagues who themselves do not perform abortions, we stand ready to challenge them by all professional means, should they breach the standard of care leading to the death or harm of one of their patients.

Sincerely,

Michael M Aziz, MD, MPH, FACOG

James R. Latronica, DO, FASAM

Jocelyn Fitzgerald, MD, FACOG, FPMRS

Devon Ramaeker, MD, FACOG

Marta C. Kolthoff MD, MA FACOG, FACMG

Alexandra Plisko, MD, FACOG

Carly Zuwiala, MD, FACOG

Noah Rindos, MD, FACOG

Policy statements by organization:

Christina Megli MD, PhD, FACOG

Pnina Dean, MD

Cynthia L Anderson, MD, FACOG, FABFM

Lauren Giugale, MD, FACOG

Grace Ferguson, MD, MPH, FACOG

Jennifer Celebrezze MD, FACOG

Tajh Ferguson, MD, FACOG

Jay Idler, MD, FACOG