Preface

Introduction

Section One: Values that transcend strategy Community Equity Wellbeing

In 2018, I visited a middle school in Northern California to try out an exercise created by the Stanford d.school called “Shadow a Student.” It is what it sounds like, which is to say, I spent eight hours following a sixth grader through her school day.

In her afternoon math class, the teacher matter-of-factly interrupted our computations to announce that we would practice an “active shooter drill.” Suddenly, I found myself huddled on the floor in a corner of the classroom with children crouching around me. The teacher barricaded the door with a homemade device he had constructed from two-by-fours. Fear was palpable. Even though we knew it was “just practice,” the answer to the question “...practice for what?” hung in the air around us.

Our bodies returned to our desks and our math worksheets, but our minds—or at least mine—did not.

I reached out to the person I knew with the most experience designing safe schools: Barry Svigals, whose firm had worked with communities to design many educational environments including the new Sandy Hook Elementary School that was built after the horrific shooting that occurred there in 2012. I was struck by Barry’s holistic approach to designing for safety.

Months later, as our K12 Lab was launching a few fellowships to dig into some of the stickiest challenges facing K-12 education, I asked Barry who he might recommend as a fellow to come dig into reimagining school safety with us at the d.school. To my surprise, he responded with his own 44-page application for the role. He was selected and joined us in 2020.

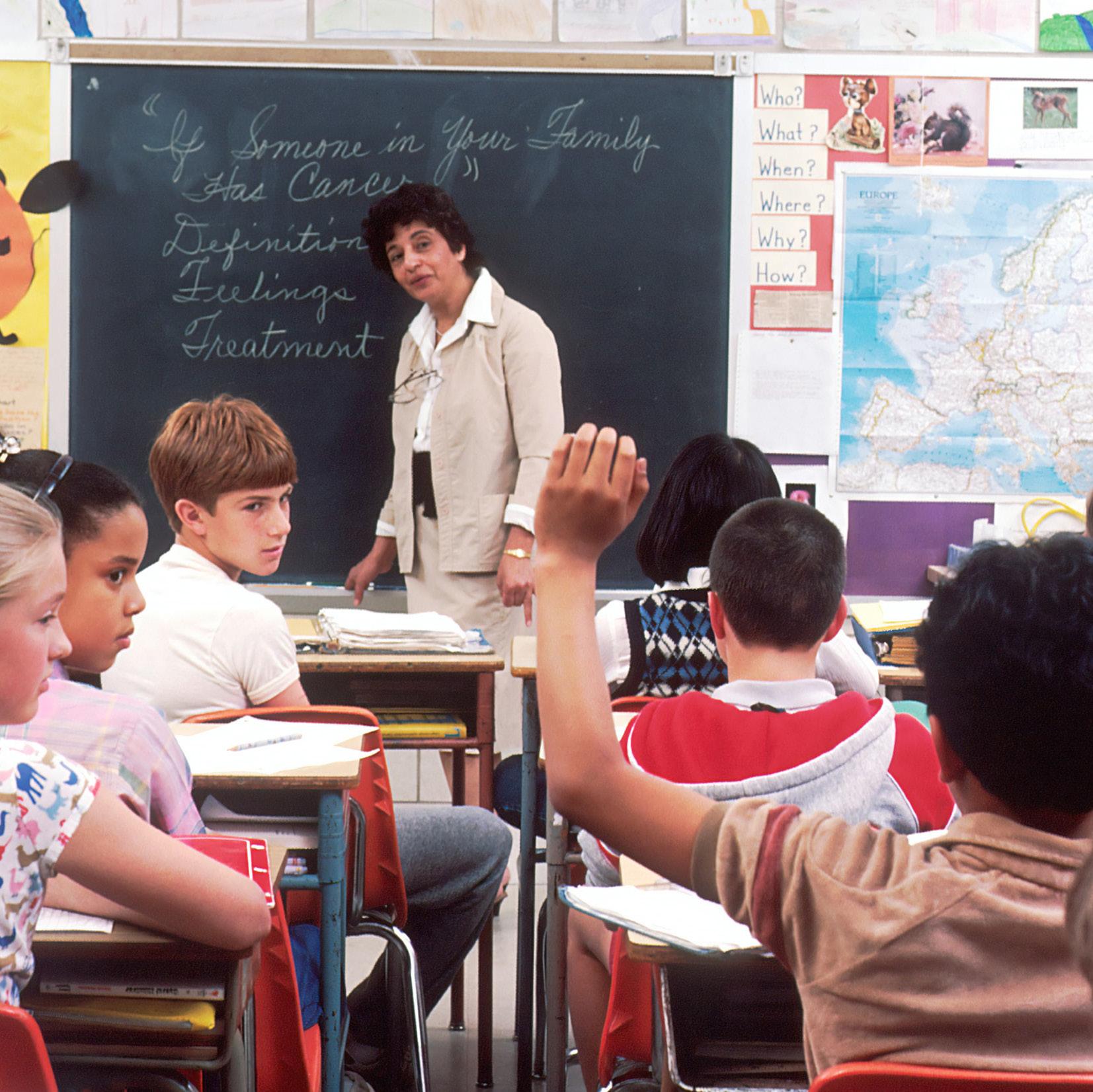

Over the last two years, through statistics, articles, and interviews, we have been intensely immersed in studying school safety together. We created a course which united graduate students at Stanford and middle school students in Oakland.

We created prototypes of physical and conceptual interventions for schools, such as “heatmapping” activities to identify spaces in schools that need redesign, studentled design and construction of archways to designate special spaces within facilities, and Post-Its that can be used to expand how school teams think about school safety. This book is the culmination of these efforts.

Barry decided to shift from running an architecture firm to focus all of his attention on holistically addressing school safety in ways that celebrate creativity, diversity, joy, and wellbeing. We have been tremendously inspired by him and we have learned a lot from and with him. We are excited for you to have the chance now to do so alongside us. Together, we can make schools that are safe, fun, and equitable. What could be more important? What could be more rewarding? sam seidel

Director of K12 Strategy + Research Stanford d.school

It is a rare gift to recognize a real need in the world and then have the privilege to respond to it. Sam’s call in the summer of 2019 was that gift and privilege.

Sadly, I have witnessed how narrow definitions of “safety” have led to an array of unintended consequences, threatening the very aim of caring holistically for all students. I have seen schools which are more like prisons; policies that inadvertently punish rather than guide; concerns for wellbeing that fail to see deeper suffering; and trauma and systemic prejudice. Sam’s proposal to reimagine school safety, a topic so burdened by fear and misunderstanding, touched the wish I have had for all of my career:

to create places for children where they will be delighted to learn. Ours became an exploration to fundamentally shift the focus from fear to joy.

Wonderfully, the d.school was the most remarkable and propitious environment in which to pursue this exploration. At the core, I am grateful to have had sam as a beloved colleague, sharing his passion for the journey we had together. With seriousness and unbridled good humor, he taught me new dimensions of an essential tool: learning how to learn. I was in awe of his skills as an educator, facilitator, and all-around inspiration.

The generosity of his friendship and expertise was yet another gift I couldn’t have anticipated.

But beyond that, the team in the K12 Lab and the whole family of others at the d.school opened me to levels of empathy and collaboration I never knew existed. So our efforts were supported and nourished by this extraordinary environment of intelligent, creative and caring people. The importance of this fertile territory cannot be overstated. It inevitably spawns ideas, prototypes, and solutions

which are born of real human values and correspond to real human needs. They become the seeds of true social transformation.

Finally, the next phase of this endeavor must include you. There are no definitive answers here, although we hope to have pointed to a clear direction. Rather, the offerings in this book need to be informed and animated by your own knowledge and care for learning. Most importantly, this endeavor needs your whole-hearted participation. As sam said, together we can make schools that are safe for all, while holding close the joy, delight and love of learning.

Barry Svigals, FAIA Partner Emeritus Svigals+Partners, Architecture+Art

What is the conversation and why do we need to change it?

Not too long ago, conversations about school safety immediately conjured up incidences of extreme violence: the active shooter, the locked-down classroom, students huddled in corners under desks.

With the pandemic, the focus quite understandably moved from guns to a deadly virus. Conversations that had been about bulletproof glass and metal detectors shifted to discussions about plexiglass around desks and protocols for social distancing.

Although seemingly different, both of those conversations share a similar perspective...They are too narrowly focused. A much larger and deadlier problem exists.

1

These two points of data are particularly striking:

It is 200 times more likely that a student will take their own life than have it be taken by another.

Pre-pandemic over 160,000 students stayed away from school each day for fear of bullying. 2

Schools must feel safe as well as be safe.

Mental health problems and bullying seriously threaten student safety. More of us need to be involved to work together to address this crisis that simmers beneath the headlines highlighting extreme and extremely rare acts of violence in our schools. This is the conversation we need to change. While we need to value traditional safety features and protocols, we must see them in the larger context of a school’s and a community’s — wellbeing.

This is the conversation we need to change.

Who is responsible for school safety?

Superintendents, principals, administrators, and security personnel

School superintendents, principals, and other administrators try to make the most of limited resources, incomplete guidance, and often conflicting messages from their own school communities about what the priorities should be. It’s a daily struggle. They are trying to make the right decisions and can benefit from the guidance, support, and involvement of their whole school community.

Parents obviously care deeply about the safety of their children and at the same time will have their own individual views of what makes a school safe. While having the best interests of their own children firmly in mind, they are not necessarily related to the larger view of the needs of the school community as a whole. Often they might be even further removed from conversations about “best practices” and exposure to perspectives on what makes school “safe.”

Teachers are on the front lines of school safety. They have their own experiences, perspectives, and opinions about what makes a school safe.

Finally, our students, who are on the receiving end of all school safety policies, are in some ways the real experts on what makes a school feel safe, yet the adults rarely consult them.

Everyone plays a crucial role in making schools safe.

This guide is intended to explore how we might develop a new common understanding of school safety with the benefit of these different lenses.

Who is this guide for? It’s for you, and it’s for me. It’s for parents, teachers, students, administrators, and everyone invested in safe schools. It’s for all of us. Because we can’t do it alone.

Each of these is inseparable from the others. They form a foundation for school safety that is truly sustainable and woven holistically into the fabric of the learning community.

This guide is organized into two sections. The first identifies the big ideas and values that might inform how we approach school safety, and the second illuminates the strategies that bring those big ideas and values to life.

Throwing the net wide and far to enliven a dynamic and inclusive school community.

Promoting an enlivened sensitivity to all students, assuring that we leave no one out, we actively invite everyone to participate, and we openly acknowledge unique needs and concerns.

Caring for the whole student, understanding that when students lack a sense of wellbeing, learning is cruelly diminished.

How we can design the school environment, select products, and train people to address our particular safety needs – always in the context of supporting the quality of the learning environment.

The Place for Safety

School buildings and grounds are the most visible dimension of a safety plan, but they are not the whole picture.

Technology and Systems

Use of security products must be integrated with all other strategies to be effective. More is not necessarily better.

People and Protocols

Training, personnel capabilities, and protocols must effectively align with the overall educational mission of the school and must promote wellbeing.

Before we begin to understand how the whole school community might be engaged in school safety, we need to acknowledge the elephant in the room, something that has often derailed the best of intentions and clouded the vision of those hoping to make rational, informed decisions: fear.

Once you have it, it is very difficult to avoid its effect on how we might live freely and happily in the world. We need to find ways to transcend our fears. Part of the aim of this guide is to offer ways in which that might happen. Primary among them is to remember to hold close what we most deeply wish for our students: to discover and rediscover the joy of learning.

Fear is the taste of a rusty knife.

John Cheever, American Novelist

The primary aim for all educators is to enhance the quality of learning in our schools. Sadly, this goal can be marginalized in our earnest attempts to make schools safe. In addressing our fears, we can put aside the fundamental aspirations we have for schools, solving a narrowly focused problem of physical safety while leaving behind the overarching need for schools to feel safe as well as be safe. Nourishing the wellbeing of all students is essential, serving a fundamental purpose: allowing a joyful experience of learning.

Let’s

How do our safety efforts compromise or enhance the quality of the learning environment?

What does “safety” mean in the school environment?

How do we decide our safety needs and priorities? Who should be involved in making those decisions?

How do we know which solutions will be most effective?

What is the process for making intelligent and strategic decisions about safety?

Are we considering the diverse needs of diverse students?

Is safety the same as security?

Are we investing in what we care most about?

$3 billion School Safety Products

$700 Million Social and Emotional

“Safety” vs Wellbeing

Given the above statistics, we clearly need to refocus and see school safety in the broader context of the social and emotional lives of our students, teachers, and families.

Making decisions to ensure our schools are safe is perhaps the most difficult task administrators face Each community has its own perceived threats and a wide spectrum of opinions about which are most important. Further, there is a lack of coherent advice as to which safety features are actually effective. And the context for these decisions is continually evolving. To appreciate the dynamics of addressing school safety, we need to ask questions that will animate our search for a better understanding.

It is crucial to understand more fully the need we are trying to address. In 2019, throughout the entire United States, there were eight fatalities due to extreme violence, and just four of those who died were under the age of 18. During that same time there were 6,488 suicides among 10 to 24-year-old students. During the pandemic, threats of suicide dramatically increased, and on the return to school, experts predict it will only worsen. Fixated on rare acts of extreme violence, we spend nearly $3 billion on school safety products—and less than $700 million on products and programs addressing Social and Emotional Learning (SEL).

Programs that focus on the wellbeing of all students serve to identify and address issues of students who may be depressed or disaffected and thereby more prone to extreme antisocial behavior.

No single element of a safety strategy can be separated from the others, or, most importantly, from the everyday life of the school – they should all work together. The roles of security resource officers, school nurses, social workers, school psychologists, teachers, students, and administrators must be integrated into any comprehensive safety program. This should include members of the community at large, such as neighbors, business owners, and elected officials. Comprehensive safety programs take advantage of inherent synergies. Enhanced learning, community development, and robust safety go hand in hand.

We are all responsible.

What is at stake is our most valuable resource: the creative minds and hearts of our children so they might become engaged members of our communities. We all share the responsibility to care for their learning environment and we must answer the call to work together to meet the unique challenges of the communities in which we live.

Let your voice be heard and make a joyful noise!

We are all in this together.

The development of any school safety initiative grows out of community engagement. All decisions should be considered collaboratively by a broad cross-section of both school and neighborhood communities. They are inextricably connected. The complex and emotional issues of school safety can only be addressed if we understand how those relationships can be mutually nourishing.

Our schools must serve all our students.

With respect to school safety, understanding the diversity of student experiences is the key to solutions that will be effective and sustainable. When considering any strategy or program, we need greater sensitivity for those who are marginalized or feel that they are disregarded or unfairly treated.

The ability to learn is founded upon a sense of wellbeing.

Without this, the quality of our educational environment profoundly suffers. This means that our students and teachers must both be safe and feel safe. Beyond health, wellbeing is the commitment to a much wider embrace: the joy of learning.

The three primary interdependent elements that assure a safe and vibrant learning environment are: Community, Equity, and Wellbeing

Community, equity, and wellbeing are the foundation for creating schools where learning can thrive.

To be useful, community engagement needs to include a broad range of constituencies. Those voices should especially include students and teachers, but also school bus drivers, custodians, cafeteria workers, and office staff. Surprisingly, although they are the most directly affected by policies of wellness and safety, their input, if included, often comes after policies have already been developed. The earlier they have a place at the table, the better.

In days past, all schools were “community-based.” Smaller communities and even some cities only employed educators who lived there. This meant that teachers, principals, custodians, and others were engaged community members and residents. In many cases, students and their parents knew them outside of school, which led to informative communications between staff and families. In many districts, we have lost this intimacy with the shifting to hiring from outside the local community. An essential element of school safety involves planning for ways to re-engage families outside of the school day. One such way may be allowing teachers to dedicate time to simply chat with students and parents about their families, communities, local events, etc. This can build back local connections.

If you start the conversation with stakeholders, you’ve already improved school safety.

Joe Erardi, former superintendent of

schools, Newtown, CT

Every community is unique.

Each state, district, and school has its own particular opportunities and challenges – no one size fits all. However, asking the right questions can create a durable and sustainable foundation upon which the safety of your community rests: the responses will contain recommendations and actionable strategies to enliven your particular school community, nourishing learning and creating a climate of safety.

voices

The recipe is a very tricky but doable one. It is a mixture of what's best for the students, care and understanding, and student input.

Zokyah, senior, LaGuardia Community College

Citizens of the World Hollywood Elementary School

Los Angeles, CA

Lyric Architects

Sometimes, chain-link fencing becomes a significant design feature of schools. This is an example of what inventive and creative minds and hands can do to transform the prison-like to the home-like, nourishing the school community in the process.

“From Mountains to Sea” is a chain-link mural project created for the Citizens of the World Hollywood Elementary School. Students were answering the question: What do you love about nature?

As part of Lyric’s pro-bono design work, Siobhán Burke collaborated with artist Yana D. Schwartz to create a warm and welcoming environment at

the main entrance to CWC. A 60-foot-long chain-link fence offered the opportunity to create a vibrant vertical “welcome mat” for the students, building a sense of dignity, respect, and positivity as they entered school grounds each day.

As members of the parent community, Siobhán and Yana engaged with the school principal to pursue a number of beautification projects that fit three objectives:

To work with students and art teachers through the arts curriculum in providing input on beautification concepts.

To create built projects that serve as models for resilience.

To reflect on the meaning of “community” and celebrate the nature of the Los Angeles environment in all design processes.

Students reflected on their favorite things about Los Angeles through a pictorial questionnaire. A theme recurred among the hundreds of responses received: LA’s awe-inspiring landscape. Hiking up to the Griffith Observatory, the seasonal blooms, the vibrant sunrises and sunsets, and beach excursions became the key inspirations for “From Mountains to Sea”. Embracing the school ethos of multiculturalism, the design was inspired by historical textile art, using weaving and crochet techniques to create colorful imagery with ribbons and textured ropes. Over the course of five days, volunteers learned to crochet rope, weave ribbon, and use zip ties. The project came to fruition in nine months.

The quality of the process equals

North Dorchester High School

Hurlock, MD

Hord Coplan Macht, architects

When presented with the need to replace their aging school facility, the North Dorchester High School community embraced the challenge. With limited funds, the community’s participation and approval were critically important, resulting in a series of community design workshops and meetings that encouraged active participation and buy-in.

“This process allows the design to become theirs. If you get people to feel comfortable playing, the result is a true community resource.”

Scott Walters, Hord Coplan Macht K12 design principal

Creative “tools for play” brought together the wide diversity of community participants. “Aspirational

Visioning” yielded the Guiding Principles for all decisionmaking. “Building Blocks” exercises, mini design “critiques” and an “architectural taste test” invited lively and in-depth contributions from the community.

“Every school should be a beacon in the community. Therefore, it is imperative to have the community involved in the design process. Through active engagement, we can all feel a responsibility for our students and their learning environments.”

Peter Winebrenner, Hord Coplan Macht principal Wellbeing at the heart of holistic design

The newly renovated and enlarged school that emerged from this robust community engagement process takes its inspiration from the notion of a balanced life – integrating mind, body, and spirit. The “mind” is represented by the academic spaces; “body” by the physical, nutritional, and emotional wellbeing of those who use those spaces; and “spirit” by the pursuit of the arts.

“A Place to Belong: The new school represents a resource that is truly for, with, and by community. The students have a tremendous level of ownership and a deep sense of belonging.”

Janine Kotob, Hord Coplan Macht associate architect

photos: Patrick Beaudouin

Putting students and teachers at the heart of school safety accomplishes multiple objectives, including buyin, acceptance, and successful implementation of new protocols.

There could be either a weekly or monthly sort of event where students and teachers discuss what needs to change and what’s going on so as a whole community they can decide the next course of action…

Ramses, sophomore, MetWest High School

“Every school safety plan must be based on partnership and relationship. Have all the voices be part of the conversation and respect those voices.”

Joe Erardi, former superintendent of schools, Newtown CT

There is an important opportunity to bring other voices into the conversation, that are not typically included. Along with students and teachers, collaborations should include custodial staff, front-office administrators, cafeteria workers, parents, neighbors, and local business owners, all of whom have a stake in the life of the school. This wider embrace of a school community will provide a long-term benefit in stimulating reciprocal relationships that nourish the social ecology of a community.

The inclusion of different constituencies assures that solutions are broader in their scope and more likely to be hard-wired to real needs they’re designed to serve. This, in and of itself, becomes a cost-effective strategy, aligning school objectives with social and built solutions that will be more readily accepted and appreciated, last longer, and better serve the entire school community.

While there is surely an advantage to building upon lessons and strategies from other communities, the very process of discovering the unique opportunities of your own community will be invaluable. This discovery process might point to local resources that could contribute to safety and quality of life at the school. Outreach for parent involvement, teacher home visits, local business partnerships, neighborhood awareness, and community educational programs all honor the rich social ecology of any school.

Playworks

Oakland, CA

Playworks is a not-for-profit organization that has spent two decades re-imagining how play in schools might be seen as an essential element of childhood development and become more directly integrated with learning in the classroom.

Jill Vialet, its founder, began to imagine how new safety protocols for COVID-19 might be playfully considered, simultaneously enlivening the school environment and keeping it safe. “Thinking as game designers opens up a whole new territory with four simple components: Goals, Rules, Restrictions, and Acceptance. Note, this is not the same as “compliance.” It requires a process that engages the students in a way that recognizes and creates the context for the co-creation of games addressing safety necessities and at the same time entirely changing the feeling of being safe.”

“At the heart of this whole conversation is the question of how we translate what is required in this moment into rules — the critical word in this sentence being how. One of the things that has been made abundantly clear in all our years of running Playworks is the importance of how things feel. Paying attention to that, above all else, has been our single best predictor of success.” Playworks published a workbook that provides a rich variety of games to ensure students feel empowered to participate in their own safety, both in being safe and feeling safe!

“One of the things that has been made abundantly clear in all our years of running Playworks is the importance of how things feel.”

Jill Vialet, founder of Playworks

“For

schools to be successful in creating the conditions that contribute to school safety, they are going to need students’ assistance through self-regulation. That is, in the end, the only way this thing works.”

Jill Vialet, founder of Playworks

Involve your students in safety protocols. Get them to play.

Ramses, sophomore, MetWest High School

students

teachers administrators custodial staff

front-office staff

cafeteria workers

parents neighbors business owners and...?

In many schools, collective involvement in school safety happens organically over time. It may begin with a core “School Safety Team” which would include the key staff directly charged with safety: principal, school resource officer, chief facilities officer, local law enforcement, and first responders. In addition, because school climate plays a crucial role in the overall feeling of safety in a school, social workers, school psychologists, and school nurses become essential members of this core group.

Most importantly, community collaboration needs to include the students.

Clearly not everyone can be included in decision-making, but as an “Advisory Committee,” a representative group of students, parents, teachers, and community participants can be creative in considering resources, barriers, and opportunities that an administrator group might not see. In assembling a committee, it’s important to consider the fact that safety is not only a concern of everyone within a school, but that its effectiveness relies on the overall strength of the community at large and how it can care for the school in multiple ways.

There's nothing more powerful than a community that discovers what matters to it.

Margaret Wheatly

At the Columbus Academy, the very fact that there is an advisory team expresses a fundamental message: everyone has a stake in the safety life of the school.

What community action looks like

It’s important to acknowledge that for decades some communities have not been afforded the resources they need to serve students. In such contexts, brainstorming new approaches can feel futile. If a community does not have what it needs to implement current programs, is it advisable to generate new safety solutions? There must be a significantly greater societal investment in education to fully enable the initiatives needed at local levels. At the same time, there are stunning examples of what can happen even in resourcelimited districts inspired by the dedicated will to create positive change.

As part of the program for the reconstruction of schools in New Haven, Connecticut, this project used a process of community inclusion that was established for the very first school and then used for all the subsequent projects. It created what was eventually called the School Based Building Advisory Committee (SBBAC). Its intent was to include a broad crosssection of the community, encouraging a sense of ownership and responsibility as well as encouraging creative input.

The SSBAC included parents, community leaders, local business owners, and teachers. The premise was that any school is a “community” resource and might offer reciprocal relationships to strengthen collaboration among the affected constituencies mentioned above. These stakeholders would then be able to benefit from and contribute to the educational life of the school.

Although Columbus Family Academy was an elementary school, the gym facilities and sports fields were designed for after-hours use through the organization of entry points and security access. A meeting room allowed parents to gather, take classes, and volunteer for supporting roles, giving them a place to come to within the school. The City agreed to move a bus stop closer to the front of the school for easier transportation for parents and students. A plaza was created at the front of the school for the use of weekend food trucks that supported activity on the commercial street and integrating community life with the school. Vandalism, which was a problem with the previous school before renovation, virtually disappeared.

You don't need a new building project to invite a wide cross-section of your community to care for the overall vitality of learning. Most importantly build upon what already exists. Make the most with what you have.

Woodruff

“School administrators who believe they can create and orchestrate a safety plan on their own are in trouble. It has to be developed around partnership and relationship, has to be around parallel thinking with public safety and school safety, around a commitment from both the police chief and the superintendent to include the whole school community collaborating on putting together a thoughtful, meaningful plan.”

Joe Erardi, former superintendent of schools, Newtown, CT

student voices

You can create a student committee whose job is to communicate to the other students during their free time and ask them about their feelings on the policies and rules…This will ensure that everyone's voice will be heard.

Zokyah, senior, LaGuardia Community College

CT

At the time the architects began the process of designing the replacement school in Newtown after the tragic shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School, the community was still deeply traumatized and fearful. At the same time, local leaders realized that the new school needed to point to the future. It needed to be a home for learning where students would not be burdened by fear but rather inspired by delight – delight in learning. Signs on every office door in Town Hall carried this message. “We are Sandy Hook. We choose love.” It cannot be overstated that taking this stand required tremendous courage.

Consequently, as the design process began, the Community Advisory Committee began every gathering with something that would reconnect its members to their most heartfelt reasons for working toward a new school. At the very first meeting, members were asked by the design team to bring in five images of things they loved about their home, their neighborhood, and their town. Each person was asked to speak about why they had chosen each image. So began a three-hour meeting during which, one after another, people spoke about what they loved, and those assembled were filled with what they heard. Everyone knew in their hearts that the spirit of the new school needed to express that love. It was a deliberate strategy to conquer fear by an ever-present reminder of our most cherished wish for our children: that they might learn in an environment free from fear and inspired by joy.

It was a reminder of what needed to be cared for… and what might be lost.

Although most communities thankfully will never have to confront such devastating losses as Newtown did, each administrator carries the knowledge of those events and others perhaps closer to home. Can we remember the Sandy Hook Community Advisory Committee’s example? They chose love.

Consider

the power of simply beginning our meetings about school safety with each person expressing the love they have for their school, a wish they have for their children, and a moment of joy they have felt for learning.

All safety and wellness strategies need to be considered through the diverse lenses of each school’s diverse student body. Although pursued with the best of intentions, attempts to “solve” safety issues can carry with them unintended consequences stemming from a limited perspective that does not visualize all students’ needs. Recent events have reminded us that unconscious bias is an aspect of being human. How might we unveil and recognize those biases so they do not adversely affect our decisions about school safety and beyond? These are often difficult conversations, and it takes courage to have them. At the same time, it is important to clearly understand which particular populations within your school might be affected by bias and how we might respond with greater empathy.

Students of color are three times more likely than white students to attend a school in which security staff outnumber mental health professionals.

In schools with security resource officers, the number of incidents of disorderly conduct are four times greater than in schools without them. Arrests are three times higher.

Miriam A. Rollin, JD, “Now is the Time to Remake our Schools with Equity in Mind,” in Better Conversations, July 15, 2020

student voices

It’s hard to tell if a student does not feel welcomed. Sometimes people are just naturally shy. A sign would probably be if they seem sad when sitting alone or tries to shrink into themselves when walking in the halls. Another sign is if the student gets stiff or nervous around a certain group of people.

Ramses Moreno, sophomore, Metwest High School

Not all students will see safety measures in the same way. Black and brown students’ experiences with armed law enforcement officials will generally have been different from those of fellow students who are white. Similarly, studies have repeatedly shown that administrators, teachers, and security personnel do not uniformly enforce safety protocols: Black and brown students, and students who are disabled or neurodivergent, all face more stringent discipline than their white, able-bodied, and neurotypical peers. Rules and protocols requiring masks, distancing, and hygiene are difficult to enforce in the best of circumstances, so it is not difficult to imagine how biases might come into play in demanding conformance to new school regulations.

Students from communities that have been victimized by police may find armed school security officers terrifying. It is essential to think critically about safety approaches: Who will a measure keep safe? Who will it endanger? Who will feel secure, and who will feel at risk?

Part of our historically myopic approach to school safety stems from the failure to understand that being safe and feeling safe are two different dimensions of the same issue. In our research, we found a number of well-intentioned “solutions” that, while attempting to protect students, actually made them feel less safe. Metal detectors are a good example of solutions with “unintended consequences.” As cited in “Education Dive” in November of 2020: “Cameras and metal detectors can create a prison-like atmosphere.”

Black and brown students and families may be even more sensitive to these sorts of “safety” features, as they fit into a decades-old reality about the school-to-prison pipeline and are far more often deployed in schools serving Black and brown communities.

While metal detectors may provide a visible response to concerns about school safety, there is little evidence to support their effectiveness at preventing school shootings or successfully detecting weapons at schools. Students in schools with metal detectors, which typically are schools with greater proportions of students of color, are more likely to perceive violence and disorder and less likely to feel safe than students in schools without metal detectors.

WestEd Justice and Prevention Research Center Report

Some questions to consider:

How are you eliciting and honoring the perspectives of the most marginalized members of your community?

How might the following circumstances influence your safety plans? Consider sexual orientation, racial demographics, socioeconomic status, languages spoken and literacy, citizenship status, and history with the criminal justice system?

Do policies for adherence to new protocols treat students equitably?

“We need to stop pretending that security measures like metal detectors and K-9 dogs and strip searches – all of which happen in schools, whether or not they’re legal – are actually making kids safer. Research has shown that when police are present, teachers and school officials will contact them for increasingly minor behavior, and security measures do not make schools safer.”

Subini Ancy Annamma, associate professor, School of Education at Stanford University

McCarver Elementary School

Tacoma, WA

Creating a safety plan is about forging partnerships, not only with students, but also with a family, a community organization, a city agency. In the process of building a school, you are building those linkages. For example, the Tacoma Housing Authority incentivized family stability by providing housing assistance. This was part of making this school.

Within the building, opening up the existing architecture invited the community at large into spaces that had previously been closed off. Providing a communitybased, open environment allowed the building to breathe. We created “McCarver Square” by opening up the old auditorium and adjacent hallways. At the same time, should a security incident occur, there was a way to compartmentalize public spaces to secure them. Most importantly, in the end, the school administrators, teachers, and students felt that this openness established a heart for the school that was essential and shouldn’t be compromised.

We try to have the architecture inspire positive relationships between people. It’s not only about a functioning

building per se but about how, dayto-day, the school community might interact and feel connected to one another. That’s the first step toward school safety.

We need to talk about scale, about there being just too many kids. Unfortunately, we are often dealing with a system where there are massive elementary, middle, and high schools. The question is, how do we foster relationships where we might not know the names of all the students? We do this by creating clusters of students who maybe then are able to form stronger relationships, by breaking down a school of 3,000 to 3,500 students into clusters of 400 students. This frees up creativity so the teachers can engage the students at a deeper level.

You need a clear vision of how the school might serve their educational goals. Security can be addressed within that vision, not compromising learning, but creating design solutions that support it.

“A joy-based reimagining of schooling will involve more human-to-human interaction, collaborative learning, less or no homework, very few assessments that are continuous in nature, and group assessments that feel less burdensome. A joybased reimagining of schooling is one where we replicate spaces that center students of the global majority (BIPOC) and let go of anything that continues to marginalize, exclude, and harm them.”

Dr. David E. Kirkland, “Guidance on Culturally Responsive- Sustaining School Reopenings,” Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, New York University

Do your safety plans affect every student in the same way?

How might they possibly exacerbate existing emotional trauma and depression? These are among the questions that should be foremost in the minds of all educational designers planning for a return to school.

As with security measures in the past, we need to remember that students will differ in how they receive the enforcement of any strategy.

Sensitivity to the social and familial circumstances of students must also be a part of any safety plan, whether in response to Covid-19 or violence within the school. Student involvement is essential. Allowing students to voice their experiences will not only help them feel more a part of the solution, but will also foster empathy and understanding among peers.

We need to look at the positive opportunity: How might you alleviate underlying distress and actively contribute to the well-being of all students? If this goal is clear and explicit, challenge your protocols to create safety solutions that actively enhance learning and well-being for everyone.

ASCEND TK-8 Oakland Elementary School

Oakland, CA

Once each year, ASCEND TK-8 elementary school invites the whole community to its Expo. Families visit the school to see the students’ work on themes chosen around social justice. These themes provide the students with emotional space to explore, in their own ways, issues that affect them both individually and collectively. Classes throughout the semester facilitate discussions among members of the diverse student body – conversations about their experiences in school, at home, in their community, and in the world.

Students and teachers brought in local police to engage in small-group conversations about school safety. They talked with parents, teachers, and staff. They developed both an empathy for one another as well as an understanding of what they might do in life to address inequities and prejudice. If only every school had such a program.

“Families were part of the original design team of the school and are the experts in our community. On a regular day, our lobby is filled with parents who stay to meet with one another and support kids. Our students regularly engage in fieldwork outside the walls of our building. It’s critical that kids are able to connect the learning happening in school and have application in their own lives. Relationships and knowing each other’s names and stories are foundational in transforming how we do school.”

Jeffrey Embleton, MFA, director of outdoor learning, ASCEND TK-8

Cherry Creek School District Day Treatment Center, Aurora, CO

In reviewing data from the 2018-19 school year, the staff at Cherry Creek School District noticed something alarming. The District was seeing a sharp uptick in suicide and threat risk assessment: compared to rates from four years prior, suicide assessments were up more than 50%, and threat assessments were up more than 300%. This was happening despite the District’s annual investments in mental health resources.

This facility will combine the programs of a PK-12 school with those of a clinical mental health facility. Serving students in grades 4 through 12, the facility will support three student populations, broken out according to their mental health needs. The “severe” population includes students who are coming out of full-time clinical environments; the “moderate” population includes students who can safely be offered more independence; and the “transitional” population are those students who are moving back into regular, full-time schooling.

The facility’s unique program acknowledges a critical gap between our country’s education and healthcare systems. Students who fall in this gap are too often the same students reflected in District data on suicide risk and threat assessments. The District hopes that this facility offers a model to other school systems across the country, providing substantive support to students struggling with mental health issues

“While

most students will never face an active shooter environment, they will all face the various stresses of the typical school environment, which can often lead to anxiety and other issues.

The District’s new day treatment center will offer the most at-risk students a bridge for them to safely transition

from a clinical environment back into their home school.”

Jessica Blanford, principal, MOA

The state of public education is merely one facet of the overall inequity facing these tribal communities. In addition to poor education, tribal communities face poverty, poor access to healthcare, economic underinvestment, cultural erasure, extensive bureaucracy, a lack of infrastructure (from roads to broadband access), and – for many of these communities – geographic isolation that exacerbates all the above factors.

“The overall issues of equity are impossible for us as architects to solve. However, there are equity issues relating to education and culture where we can have a big impact. The schools we have designed for tribal communities emphasize educational and cultural equity, and it’s been wonderful to see these facilities make a difference for their communities, especially towards the continuation of cultural ways of life.”

Jack Mousseau, principal, MOA ARCHITECTURE

In 2012, a new PK-12 facilities handbook for the Bureau of Indian Affairs addressed some of these inequities, including inconsistent and poor-quality learning environments, bureaucracy surrounding the development of a new school, and the effects of cultural erasure, which have limited the spread of Native American languages and cultural practices.

The design of facilities for tribal communities can mitigate cultural erasure and is therefore an essential aspect of school design in these communities. The school program described in the handbook includes

a space specifically dedicated to the practice and teaching of tribal culture. The design guidelines embrace flexibility, providing opportunities to weave cultural elements and references throughout the facility, from signage and exhibits to the overall building form, and exterior materials. The handbook resists viewing Native American tribes as a monoculture by recognizing the vast differences among tribes.

The critical takeaway from the experience of working with these marginalized communities is that the consideration of equity (or the lack thereof) should be part of every facility planning and design process. While planners and architects alone cannot turn the tide on overall issues of equity, we can have a significant impact in expanding the conversation during the design process to include cultural equity.

Todd Ferking, AIA

National K-12 design leader and principal DLR Group, Seattle, WA

We need to be clear that when we’re talking about equity, we’re not simply talking about race. It’s all kids, all students. That means kids with disabilities, that means kids that are high achieving, or low achieving, or struggling at home.

We do need to focus more on kids who are not in the top 10, who experience prejudice, who might simply feel alone. How do we engage the kids who are struggling, who don’t have a family support system, and who are going on the wrong path? It’s all the more important that we create architecture where students can feel included.

What’s striking is that the strategies we can put in place for those kids are in fact what ALL kids need. In so many ways, connected, personalized education is what everyone needs.

In leveling the playing field, we’re also elevating it.

This has to do with safety because it’s fundamentally about reducing the anxiety of kids who, in many schools, suffer from being in an institutional and uninspiring environment, who feel distant from adults. That anxiety comes out. It’s bound to. The more we can meet those basic needs of being human, the safer an environment becomes. We can meet simple needs, like a clear orientation, a sense of scale, light, air, and visibility. We can create a lovely space that people just want to be in. Then they feel cared for, respected, connected: they feel they belong.

The building is strengthening relationships among students but also among all who belong to the school community. It’s infused in the architecture. Most of these strategies that support these relationships are invisible, but they are crucial.

Glass and visibility make the school safer by enhancing surveillance; more importantly, they help people feel connected to one another.

“Discrimination is seen as a problem by one third of all students who were interviewed. It was not seen as a problem by over 80% of the school safety staff.”

2021 State of School Safety Report Safe and Sound Schools

How might wellbeing be seen differently by different students? Perhaps for some, mental wellbeing comes through silent meditation, while for others it comes through loud laughter with friends. How do we show respect for diverse – and at times conflicting – experiences of wellbeing?

Some other questions to consider:

Do we offer support services that can adequately respond to the diverse needs of the students?

How might community processes and restorative justice practices help strengthen the school culture?

How might we honestly evaluate our efforts to honor the diversity of our student body?

In order for schools to both be and feel safe, strategies for safety must include all the students. If any part of the community feels marginalized, wellbeing and safety for everyone will suffer.

Safety is most often thought of as “hardening” the school’s architecture, adding “safety features” such as surveillance devices, providing security personnel, and improving emergency protocols. As we emerge from a global pandemic where public health has dominated, we recognize such features as important, but we also understand that a definition of safety that fails to include the emotional lives of our students has serious consequences.

If students do not feel safe, they are not safe.

The most damaging unintended consequence of our overwhelming focus with preventing physical harm, either by violence or infection, is a diminished investment in programs that support the overall wellness of the student body.

All safety plans should include a range of building enhancements and robust protocols. However, a safety strategy will be more effective and sustainable when it means an investment in coordinated programs for both safety and wellness.

Are investments in the “hardening” of school buildings to protect from intruders disproportional to investments in programs that address social emotional learning?

Counterintuitively, although mass shootings remain extremely rare, they receive the lion’s share of attention in school safety conversations. We can plan for those events that are possible, but we need to direct more attention to more probable threats.

Considering everyday security issues, extreme cases of violence are clearly far less likely than many other threats. On a daily basis, school administrators are faced with a full range of threats to the essential wellbeing of their students including disengagement, bullying, substance abuse, and anxiety and depression.

“Just as health is more than the absence of illness, feeling safe is more than the absence of [violence]. Feeling safe is also grounded in feeling supported, engaged and at least some of the time, feeling joy.”

“There isn’t a safety plan of any credibility that does not include social emotional learning.”

Joe Erardi, former superintendent of schools, Newtown,

CT

Jonathan Cohen, Ph.D., co-president, International Observatory for School Climate and Violence Prevention

Part of the NYU/Steinhardt School of Education, Metro Center has created one of the most comprehensive guides to re-opening schools after the pandemic. Although written in the spring of 2020, its messages remain essential for all those committed to equity in our schools.

“It would be a mistake to imagine the school reopening process absent an acknowledgment that something fundamentally has taken place in our world, that the thing that interrupted life for millions of Americans afflicted vulnerable populations in ways disproportionate to more privileged populations. In acknowledging this, we provide this document—a set of suggestions and topics to think about—for humanizing the school reopening process.”

“How might we decide, determine, re-imagine, and recreate through an equity lens? How might we interrogate how our own experiences and positionalities have impacted and continue to impact our navigation through crises, whether and to what extent are we in alignment with students’ intersectional needs and responsive to their culturally textured experiences? Each decision we make should involve one simple question: ‘How will this impact our most vulnerable populations?’ They are the case study, the barometer, from which we navigate the space.”

“How might we decide, determine, re-imagine, and recreate through an equity lens?”

Students are the eyes and ears of the school, and not just during the school day. We know about things that affect school life, 24/7, even when they occur outside of school hours or off school premises. Teachers and administrators should consider the concerns we have as just as valid as other adult groups, such as parents, because we often feel the least safe in a place that we are meant to feel the most comfortable in. By working collaboratively, students can be an invaluable way of assessing which concerns to address first and how impactful new policies are.

CAMDEN LARSEN student leader, South Dakota

While I’m disheartened by the disparities in perceptions of school safety, I am glad to see a broad understanding that mental health is a top priority. Students face more and more pressure every year it seems, but they aren’t necessarily getting the skills and resources they need to handle it all. Schools with strong, supportive mental health resources are just as important as having strong, supportive building foundations.

JULIE CAILLE

parent advocate,

Washington

www.safeandsoundschools.org/ resources/state-of-school-safety-reports/

The 2021 report is the fourth published by Safe and Sound Schools. It includes surveys compiled by Boston University School of Communication that communicate a number of powerful messages.

Mental health is primary: Among all groups surveyed — school staff, public safety staff, administrators, students, and parents — the most concerning safety threat was mental health disorders.

For students, the threat of active shooters concerned them less than did mental health problems and bullying.

Not all are equally safe: 50% of students feel their school does not have a distinct safety plan for their fellow students with special needs.

Survey participants saw a disconnect between students and school officials: a third of students saw discrimination as a problem, compared to less than 20% of the public safety staff.

40% of students do not agree that their school is able to address bullying and/or violence, while almost all of the school staff, public safety staff, and school administrators feel they do.

Student respondents worried most about these five threats:

Mental health 16%

Bullying 14%

Active shooter 14%

Discrimination 13%

Sexual assault 8%

Bullying remains a prevalent concern, with nearly half of students, parents, and public safety staff responding that this is a problem in schools. Bullying and its associated impact on mental health continue to deserve attention. These problems have likely been exacerbated by feelings of anxiety and isolation arising from the disruptions to healthy social connections during COVID. School administrators, faculty, and school-based mental health professionals should provide opportunities for students to engage in active, ongoing discussions and skill building about healthy relationships and mental health to prevent bullying and provide support to those experiencing it.

AMANDA NICKERSON, PhD,P director, Alberti Center for Bullying Abuse

Depending on how the pandemic evolves this fall, schools may need to help parents find ways to connect to the feelings of loneliness, anxiety and depression they feel. These are also issues for students, making mental health support more important than ever. All groups know threats to mental health exist and need to clearly understand the pathways for accessing resources and to be reassured that their feelings are valid and taken seriously.

School staff, public safety staff, and school administrators indicated that mental health problems (e.g., depression, suicidality, and impulses to self-harm) are the most concerning safety threat at their schools. This is consistent with 2019 and 2020 findings.

Mental health issues are now regularly being recognized, in public and private sectors, as a major underlying cause of aggressive or violent behaviors. Addressing these issues is, perhaps, our greatest area of opportunity: we can bring all constituents together, especially

students and parents who have demonstrated willingness to help identify problems with and gaps in school protocols. It is critically important that school leaders take them up on the offer.

Perhaps the most telling finding from this year’s State of School Safety Report is the disconnect between school administrators and the two most important groups they serve –the students and their families. This perception gap has persisted during the four years since Safe and Sound Schools started this annual research program. While school communities have made many strides toward making schools safer, this survey reiterates that school leaders must do a better job of providing ongoing opportunities for students and parents to share their perspectives regarding school safety. School leaders should make a concerted effort to engage student and parent leadership and dialogue to address school safety concerns and identify solutions. This would be a great goal to include in a 2021-2022 school improvement plan!

Kevin Gogin, director of safety and wellness, San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD)

student voices

To be safe you are protected by all violence and negativity. To feel safe, you feel comfortable in the environment and community. You feel like you belong and feel free from any fear and worries. By feeling safe you feel as if you’re in your safe place, a place where you can be and be yourself.

Emilio, first-year, Unity High School, Oakland, CA

Our collective wish would surely be that our students attend schools which not only are safe, but feel safe. As Kevin Gogin, the San Francisco Unified School District Director of Safety and Wellness said, safety means that “every student can bring their full selves to school.” This can only happen if we re-imagine “safety” as a matter of wellbeing. In the wake of school shootings or the threat of a deadly disease, this is not an easy path to follow.

Fear makes it all the more difficult.

Joe Erardi former superintendent of schools, Newtown, CT

I always ask: How well do you know your most complex students, teachers, or community members?

All of this is around safety. The SEL [social-emotional learning] dimension is the proactive part of school safety. Unfortunately, it’s seen by many school administrators as the most difficult, not because they don’t know where to go, but because it’s so difficult to fund, if you’re putting in bulletproof glass or security cameras. It’s a one-time expenditure and you’re all done. The SEL piece is personnel, and ongoing expense being amortized over many years. However, the fact is, it’s never done. While those one-time costs may have relative importance, they must be part of a broader understanding of what school safety really is.

I’ve been really privileged to consult to about 20 different school communities in Connecticut. They have come to me to discuss issues around safety. When I recommend to a superintendent a monthly meeting with the lead public safety officials in their community and the pushback is, “Well, once a month is too often; how about if we do it quarterly?” If that’s truly how you feel, I’m probably wasting my time in your district, because if you’re not willing to spend the time, it’s not worth it. If superintendents don’t embrace the commitment, if they’re not in the front of the plan, there is no plan. It’s not something you can delegate.

You might delegate a whole bunch of things, but if you’re delegating school safety, if you’re sending that message out to your school community, then how important is it really?

When we would have our district safety committee meeting, the meeting was chaired by the chief, by the superintendent, by the director of security. Around that table were different stakeholders, school board members, parents, administrators, local police, transportation, food service; anyone and

everyone who was a part of the plan was around that table. They showed up every month, because I was there, the chief was there, and if we sent in a rain check, they wouldn’t show up. There is no way you can buy your way out of school safety. There is much more than that.

Hardening of schools is the easiest to understand. But it comes down to being proactive or reactive. School administrators are comfortable with school safety as a product you can put in place right away. SEL is a longerterm solution, but one that is emphatically proactive.

There is no way you can buy your way out of school safety.

We begin by holding close the three elements of all successful strategies for school safety: Community, Equity, and Wellbeing.

From that, three interrelated dimensions emerge as we design the school environment, select products, and train people to address our particular safety needs – always in the context of supporting the quality of the learning environment.

The school campus—the building(s) and grounds—is the most visible dimension of a safety plan. Designs that emerge from collaborative community engagement can be more effective and sustainable while also being strategic targeted investments. Most importantly, if seen holistically in the context of educational goals, they can also support the quality of learning.

Security products need to be integrated with all other strategies in order to be effective. Considering every decision in the context of the architecture and the personnel will allow the design team to select the most appropriate solutions for the school’s particular needs. More is not necessarily better.

Knowing what to do, when, and how requires an understanding of the two previous dimensions. Training, personnel capabilities, and protocols can then allow building strategies and electronic systems to effectively align with the three key elements of the school’s educational mission: nourishing community, advancing equity, and promoting wellbeing.

The recommendations in this section were developed in collaboration with Phil A. Santore, vice president, Ross & Baruzzini, safety consultants for the new Sandy Hook Elementary School.

The three essential elements of all successful strategies for school safety are:

Community, Equity, and Wellbeing

student voices

School safety policies are meant to help students, but if a student does not agree with them it can affect them. It can affect them in a positive way or negative way depending if they agree or disagree with the policies.

Isabel, 9th grader, Holy Names High School

Security does not equal safety. Moreover, more security is often mistaken for more safety. In fact, a security product is merely one among many tools for creating a safe environment. Being secure and feeling safe are not the same thing. This is essential to understand when reviewing protocols, products, and services to enhance “safety” in your school.

When a traumatic event occurs in our own school or in another, the natural reaction for all of us is to immediately do something that we think will make our school more secure. This is when we all must take a deep breath and step back to see the whole picture.

While security products are components of an overall school safety program, a balanced and inclusive process allows schools to develop strategies and protocols and to incorporate products and services that support the educational life of a school as a whole. Besides being more effective, this approach can help us avoid unintended consequences that might actually do more harm than good.

Collaboratively conceived, safe strategies begin with understanding the ABC’s of a sound and successful program for a safe school.

The first step is to develop and set achievable integrated goals. Although this work typically begins with an inner circle of administrators and security personnel, it should include a broader constituency from the outset. Expanding the circle will provide a more holistic perspective.

Beware of any product that promises to solve all your safety problems.

After Columbine, and each subsequent highly publicized school shooting in the United States, schools have focused on methods to “harden” themselves as targets through increased security measures: surveillance cameras, metal detectors, and positioning armed police officers on campus, known as school resource officers. Since 2000, the U.S. government has distributed nearly $1 billion to schools across the country to fund school resource officers.

But accumulating research has shown that the conspicuous security, including the presence of school resource officers, has little to no effect in preventing school shootings, or reducing casualties.

Opening as much as possible to the natural environment surrounding the school was essential for the wellbeing of the children.

Sandy Hook Elementary School Newtown, CT

Svigals + Partners, architects, New Haven, CT

In creating the architectural environment, begin with the question of how we can support and nourish learning while at the same time providing a protective building and surrounding landscape. At the new Sandy Hook Elementary School, a number of design features serve multiple goals, invisibly addressing safety issues while enhancing the educational environment. At the front of the school, a rain garden captures water from the roofs to irrigate plantings that enliven the front of the school, and students learn about the local species that grow in the shallow swale. Three bridges cross the swale at key entry points, one at the Pre-K entrance, one at the main entrance, and a third at the entry to the cafeteria and gym, large spaces for school and public events. These bridges are a metaphoric expression of the small bridges in the town across the Pootatuck River that runs through it. From a safety perspective, the swale serves as a barrier across the entire front of the school with the bridges channeling visitors to controlled entrances where they would be easily visible.

Opening as much as possible to the natural environment surrounding the school was essential for the wellbeing of the children. Another safety strategy aimed at preserving those views to the outside for smaller children while restricting views into the classrooms. This was accomplished by taking advantage of the existing grade that descended at the back of the school, raising the classroom wings higher. This permitted us to build windowsills that from the outside were higher above grade and didn’t compromise views from the inside.

The established guidelines of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) provide a starting place for creating a sound school safety plan, but it can’t end there. Many security/safety issues can be addressed through design strategies without significant security expenditures.

Some examples:

1 Creating designated parking zones.

2 Not designating the parking spaces for security resource officers so their absence isn’t broadcast.

3 Dedicating specific entries and exits.

4 Utilizing natural and man-made landscapes to set boundaries.

5 Locating high-density occupied areas away from exposure to potential threats.

6 Partitioning the interior of schools to create both secure and non-secure environments such as for after-school activities and community usage.

7 Installing secure doors, frames, and associated hardware. Additionally, a planner might discuss whether to install hardened glazing and windows in discrete locations where their value can be clearly established.

Wickliffe Progressive Elementary School

Upper Arlington Schools, Upper Arlington, OH

Perkins & Will, architects

For Wickliffe Progressive Elementary School, set to open for the 2020/21 academic year, the design team challenged the notion that a school could not be safe and simultaneously inviting, flexible, and learning-forward. In fact, the “Guiding Principles” developed with the community at-large required both. Working in concert with district administrators, school board members, school building team members, and local first responders, the team devised several strategies, one of which compartmentalizes entire sections of the school in the event of an emergency. For example, entry doors to multi-grade-level “pods,” accessed through a welcoming (but secure) library, are automated to close when called upon, providing a safe harbor for those students.

As a result, the internal workings of the pods thrive on transparency and flexibility, making learning visible and allowing each learning studio to connect to a “commons” space via glass overhead doors. This type of connection is also true for each pair of adjacent learning studios. Teachers anticipate that the default overhead door position will be “open,” with full-on collaboration happening most frequently; but they know that when desired, they can create more traditional classrooms. Students and teachers will also enjoy the two small-group spaces accessible from the commons, as well as embedded learning resources and instructional support. In keeping with the district’s strategic focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion, each pod contains several gender-inclusive toilet rooms.

Part of the problem with addressing school safety is the proposition that it's either safety or education that comes first.

This is a false dichotomy.

Is your school entrance welcoming?

“Heavy fortification at a school's perimeter, in the form of a walled enclosure, is not only anathema to the openness and freedoms we associate with education, but it is—ironically, perhaps—a psychological indication that the situation is in fact unsafe.”

Julia McFadden, AIA, associate principal, Svigals + Partners, architects

And…remember the importance of outdoor educational and recreational spaces. They shouldn’t be compromised by aggressive enclosures or limited access.

All too often, outdoor spaces are overly protected with fences or ignored, deemed non-essential when planning security and safety strategies. Outdoor educational spaces need to be readily accessible as they offer an invaluable connection to our natural environment. Electronic communications can help control access, giving teachers and staff flexibility in allowing students to enjoy these spaces.

Beyond being cost-effective, the overarching benefit of this “both/and” approach is that the creativity of the architects can be engaged in solving multiple problems simultaneously by creating security “features’’ that actually contribute to the vitality of the learning environment.

While visual access is essential for nourishing the life of any school community, it is also a safety feature.

Glazed spaces can be open and visible and still provide a “forced entry” resistive protocol. While open visibility may be seen as a challenge, properly designed it can provide for visual communications which enhance the life of the school while acting as a deterrent to adverse behavior. When intruders or students know they can be seen, they are less likely to engage in threatening activities and providing visibility allows everyone to see potential threats from both within and outside.

Robert Benson Photography

Natural Disaster Response, Puerto Rico

DesignEd4Resilience, Mystic, CT

Safety is found in the collective power of all of us.

In colonized and disaster-affected Puerto Rico, resilience came to mean more than bouncing back to face it all again. Instead, DesignEd4Resilience (DE4R) helped to unite and support educators, youth, and community leaders deploying People, Place, Purpose, Process, and Positivity to address community challenges and drive change. DE4R brought together local organizations and networks to amplify local strengths with community-led design thinking and to catalyze the regenerative resilience that was already there. School and community worked together to learn with purpose and belonging so that demands and changes could proactively disrupt corruption and replace it with fairness, enable coherence over chaotic fragmentation, and feed learning communities that heal, celebrate culture, and restore civic courage.

Design Labs and Simposio Co-Creando collaborations are resulting in new community and youth-designed challenge-based curricula in economic and environmental sustainability, disaster readiness and resilience, food security, flourishing life design, celebrating people and culture, and more. They are creating multi-generational community resilience and learning hubs, in both secure buildings and community gardens. Youth and their adult allies are cocreating nano-solar-powered hand washing and agroecology stations, solar refrigerated lockers to keep medicines and breast milk cool no matter what, family journals, better evacuation plans, mobile (mental health) Fun Stations, and earthquake-proof houses that can also float. They are asking, what if the purpose of learning at all levels were to bring people together to celebrate strengths, and address challenges that matter? Resilience and safety go hand in hand.

student voices

In the year after [Hurricane] Maria, all I could do was draw. I just drew and drew. Design

Lab has given me my voice back. Now I know I have ideas that can help.

Yaría, age 16

All technology systems, including electronic security, should be integrated and interoperable. This approach provides the highest level of data management of a facility and offers informed situational awareness for immediate response or action. And! It is also less costly.

Phil A. Santore, security consultant, Ross & Baruzzini

“My school is able to maintain digital security and safety.”

A quarter of the students disagree with this statement. As the highest users of technology, it would be beneficial to include them in cybersecurity discussions. They may recognize vulnerabilities of which the staff are unaware.

Safe and Sound Schools, 2021 State of School Safety Report

Security systems should typically involve the following:

1 IT data backbone (provided by the school district)

2 Communications/telephone systems

3 Public address and/or mass notification system

4 Integrated Security Management Systems (ISMS) including electronic access control, intrusion detection monitoring, video surveillance system, and visitor management system.

5 A shelter-in-place protocol to rapidly respond to a potential exterior or partial interior threat. An integral component of the ISMS, it depends on the interoperable functionality to monitor and control multiple system elements simultaneously. Most technology is readily available and off-theshelf. It is not new or exotic.

6 A plan to manage medical and similar emergencies. Electronic security and related systems can help staff identify and act on data gathered by these systems, such as:

a Electronic temperature monitoring (staff and students)

b Pre-screening apps for smart devices

c Running logs of visitors and their health dispositions

d Visual records from video surveillance systems

7 IT and network systems as a tool for emergency rescue and recovery (ERR). All related components of security systems (such as video surveillance, access control, and intrusion detection systems) should operate on a survivable IT backbone. This will ensure availability in natural disasters such as tornadoes, floods, and other natural threats.

When these systems are designed with school climate in mind, they can be an effective tool to enhance the life of the school while providing a safer environment.

Understand the level of ability and commitment of security staffing available to manage, monitor, and respond to incidents.

Training is key and should especially extend to teachers who are on the front line. Protocols can be creatively conceived to both reinforce the security of the school and also enhance the feeling of safety. If designed with wellbeing in mind and a sensitivity to how any protocol affects the emotional lives of teachers and students, the school can both be safe and feel safe.

School safety policies are important because if a student does not agree with a policy it can affect their mental health and take an affect with their behavior and performance.

Ariana, 9th grade, Cristo Rey De La Salle

Joe Erardi, former superintendent of schools, Newtown, CT

A major oversight in school safety planning is failure to include student voices in the conversation. In Newtown, we met with every senior English class. It had nothing to do with senioritis because every senior was on point and in part of the conversation we asked what we did well and what we didn’t do well, and it was amazing that through the lens of the learner we were able to build a better plan in the following year. The important piece is to include the student voice.

Unfortunately, the student voice is many times forgotten or is undervalued. That’s when your safety plan suffers.