Introduction

Election administration, once an overlooked aspect of government, is now recognized as an essential infrastructure of democracy. Our elections require vigilant attention, skilled talent, and adequate resources to deliver accurate and trusted results.

Increasingly, the usefulness of human-design in government organizations and in the public sector is being recognized. After collaborating with election officials and election experts in 2020 to navigate the challenges of voting during a pandemic, Stanford’s d.school gained a deep appreciation for how design profoundly plays a role in election administration. Election officials are logistical masters, capable of administering elections despite a myriad of constraints. Many of the decisions they make are inherently design decisions—whether it is the layout of spaces, the voter experiences, or the creation of clear graphics, to name a few.

This booklet, developed alongside an exhibit to highlight the role of design in election administration,

showcases the many design decisions election officials make in the months before, during and after an election. The content is organized around five areas where local election administrators have the most influence over elections and the voter experience. Across these topics, we have outlined some compelling design questions, inviting more engagement and involvement from those eager to support effective elections.

Our goal is to celebrate election officials, not only as the logistical experts that they are, but also as invisible designers who strive tirelessly to improve the way they administer elections, all the while overcoming new and increasingly complex hurdles and constraints along the way.

AUDIENCE LENSES

We recognize that different audiences will find distinct value in the content, questions, and examples we have curated. To help guide your reading, we have identified four audiences and have provided provocations to offer distinct perspectives as you engage with this booklet. These suggestions can help you focus on specific areas or highlight relevant questions to consider as you explore the content.

Election Officials

This includes local election officials and staff, as well as others in the election space, like poll workers, state officials, state leaders, and vendors that serve election offices.

• Where are areas of election administration where design has and could play a role?

• What are examples of design improving election administration and the election experience?

• How does a document like this offer a fresh perspective on the complexity of elections?

Professional Designers

Designers currently working outside of the public sector, and those looking to expand their understanding of where it’s possible to use design.

• How does design show up in civic spaces?

• What might it look like to apply your design skills to elections?

• Where might design be able to provide value for democracy?

Design Students

Students currently pursuing undergraduate and graduate degrees in design or who are considering design as a possible career.

• What does design look like outside of physical products?

• What challenges do election officials tackle with design?

• How does design play out in complex, multi-stakeholder spaces?

General Public

Individuals interested in understanding more about elections or are curious about different forms of design.

• What are all the things your election officials are responsible for?

• What types of design are new or unexpected?

• How might citizens play a role in shaping how government functions?

Elections don’t just happen. They’re designed and administered by over 10,000 local election offices across the United States.

ABOUT U.S. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION

To ensure fair, free, and safe elections, officials invest endless hours paying attention to the details of running elections. They consider every aspect of the voting process, raising questions like:

• Where should we place polling locations, drop boxes, and signs?

• What kinds of instructions, ballots, and voting booths serve voters best?

• How can we effectively train poll workers?

And their jobs are only increasing in complexity. Election officials not only have to think about administering the opportunity to vote, but now they must increasingly think about cybersecurity threats, supply chain issues, and ensuring the physical safety of their staff.

The entire election ecosystem is extremely complex and includes numerous entities, evolving requirements, and nuanced state-specific policies. In this section, we discuss the different levels of election administration, give a sense of the diverse skills needed by election officials and discuss how administrative duties occur far beyond Election Day.

How state and local offices administer U.S. elections

Elections are not federally administered: the voting experience and operations are designed and implemented at the state and local level.

State and local agencies are responsible for election administration before, during, and after each election. Voting during elections occurs in

local jurisdictions that are typically delineated by city or county legislation.

STATE ADMINISTRATION

Much of the legislation and oversight for elections happens at the state level.

States have different ways of overseeing elections, as denoted below. Regardless of the governing body, in each state chief election officials and/or the election board or commissions are typically responsible for:

• Creating state election laws and ensuring they are followed by local officials;

• Administering statewide voter registration;

• Creating a testing and verification procedure for voting equipment; and

• Supporting local election officials in their work.

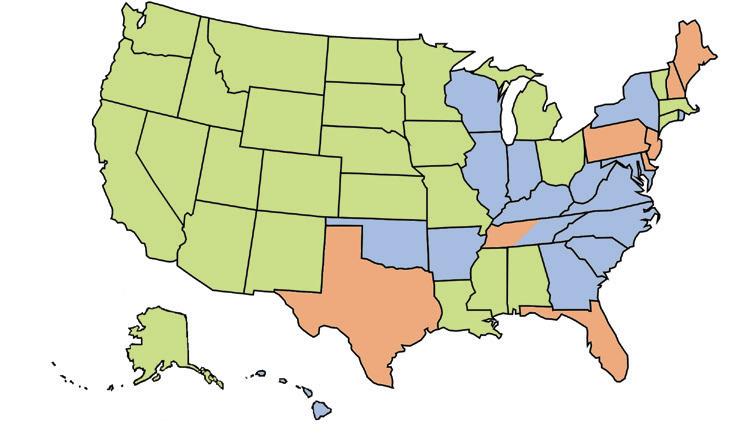

26 states have an elected Chief Election Official

16 states have an appointed Chief Election Official

8 states have an Election Board or Commission or a combination of a Chief Election Official and Board or Commission

LOCAL ADMINISTRATION

Local elections offices are responsible for the on-the-ground operations that voters experience in each election—and this depends on the unique dynamics of each jurisdiction.

There are over 10,000 local jurisdictions in the United States, each independently administering elections, within the bounds of their state’s legislation and guidelines. The size of each jurisdiction varies greatly. Regardless of how many voters are being served, there are election professionals responsible for running each election, including creating ballots, setting up polling sites, collecting and processing ballots, and reporting results. In addition to local election officials, there are also poll workers, board workers,

field rovers, troubleshooters, temporary workers, and full-time employees who support election operations. It takes hundreds of thousands of Americans to conduct elections.

The office size segmentation illustrated below describes the range in size and capacity of local elections administration offices. The original segmentation, which includes five categories, can be found in the 2022 Democracy Fund/ Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials.

SMALL

< 5K VOTERS

Typically one individual working part-time. Most election offices are in this category and one-third do not have a full-time staff member.

MEDIUM

5K–250K VOTERS

Typically 1–2 individuals working full-time with some additional part-time staff.

Two of the smallest jurisdictions are Dixville, New Hampshire with 5 registered voters and Drew, Maine with 24 voters

Carson City, Nevada has 40,000 registered voters. Hunterdon County, New Jersey has almost 100,000 registered voters

LARGE

> 250K VOTERS

Large teams of full-time employees. 8% of such offices support 75% of the voters in the U.S.

The two largest jurisdictions are Maricopa County, Arizona with 2.4 million, and Los Angeles County, California with 5.6 million registered voters

A wide range of competencies are needed in local election administration.

Many voters don’t realize all the skills needed to successfully run an election. Local election administrators’ responsibilities go well beyond providing ballots and counting votes. They must take on a

wide (and growing) range of tasks and duties to run effective elections. These duties are logistical, relational, managerial, and technical—and are undertaken throughout the year.

▲ The Election Administrator Competencies Wheel, created by U.S. Election Assistance Commission, displays the array of competencies elections officials must take on.

Running an election is a year-round endeavor.

A lot goes into planning an election. Starting months before Election Day, election officials are processing candidate petitions, securing polling locations, ordering materials, and hiring and training staff and poll workers. The complex logistics of ensuring that our democracy is accessible and secure requires diligent attention to every facet of the process.

Tasks necessary to run a fair and free election start many months prior to Election Day, and extend beyond. Some tasks are highlighted in the call-outs below, and approximately when they might be done. Design plays a significant role in these selected tasks, and they relate to the chapters that follow.

Starting 200 days before Election Day, officials find and vet polling sites.

Engage voters in the next elections (100 days prior).

Begin to recruit new poll workers (100 days prior).

Review voter rolls, and prepare for new registration (100 days prior).

Finalize ballots and send files for printing (45 days prior).

Prep to receive and process mail-in ballots. (30 days prior).

Install mail dropboxes (21 days prior). Work

DESIGN IN ELECTION ADMINISTRATION

Our election administrators are the de facto designers for the central act of our democracy—the voting experience.

Election officials are our neighbors, our family members, our friends. They are elected, appointed, hired, and enlisted—and they come with many titles: clerk, recorder, registrar, auditor, supervisor, probate judge, assessor, commissioner. Because local

election officials are responsible for a diverse set of operations and voter experiences throughout the year, in practice they must embody design mindsets, approaches, and skills.

▲

The staff of the Elections Bureau, in Doña Ana County, New Mexico (132,379 registered voters in 2024).

Design plays a valuable role in many aspects of election administration.

While most election administrators are not designers in title, there are many design practices they embody and many products of design they utilize in their work—all across a multitude of areas of work in order to administer each election.

DESIGN PRACTICES IN ELECTIONS

Design is a broad field with many sub-disciplines. Six of these disciplines (or practices) that are relevant to elections are highlighted below.

GRAPHIC AND COMMUNICATIONS DESIGN

The visual, graphic, and textual design of artifacts and systems. The intention is to create clear communication and intuitive use.

EXPERIENCE DESIGN

The work of creating a productive and positive experience for people. People’s need can be met through the design of physical space, services, and interfaces.

PRODUCT DESIGN

The design of physical items people may use. Considering the affordances of the product improves the experience of the user.

PROCESS DESIGN

The design of workflows and procedures. This is used to streamline operations and create repeatable and predictable tasks of the process.

INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN

The design of instructional materials and learning experiences. The objective is to create engaging and effective learning.

SYSTEMS DESIGN

The planning and creation of systems that undergird human and societal life. This requires consideration of how experiences, subsystems, and processes work together.

AREAS WHERE DESIGN PLAYS A ROLE

In every jurisdiction, election officials are carrying out many of the same functions—even if there are distinctions in the details. In this book we have focused on five areas where design has played a significant role in local elections administration, and where design can continue to contribute.

Polling Site Selection & Layout

> Where should we place voting sites to maximize access?

> How can we effectively use polling site space to serve voters?

> How can we design polling sites for greater accessibility?

> How can we best guide voters through the voting experience?

Voter Registration & Communication

> How can we design materials that allow voters to register successfully?

> Where can we provide voters with registration opportunities?

> How can we design online registration to serve all eligible voters?

> How can we keep voters informed about elections?

Election Worker Engagement

> How can we attract and recruit election workers?

> How can we design training of election workers to be engaging and effective?

> How can we appreciate and celebrate election workers for the work they do?

Ballot Design & Collection

> How can we help voters easily navigate the ballot?

> How can we design ballots and voting methods that are accessible to all types of voters?

> How can we offer voters ways to successfully return their ballots?

> How can we design secure and efficient drop boxes for ballots?

> How can we design vote-by-mail systems to serve voters and allow efficient processing?

Processing & Reporting the Vote

> How can we design ballot processing for efficiency and accuracy?

> How can we provide the public with transparency into how votes are counted and recorded?

> How can we design systems to transport and process ballots securely?

> How can we set the right expectations for when a race could be called?

> How can we present election results so the public can access and comprehend them?

Polling Site Selection & Layout

Election officials design the voters’ most direct experience democracy when they select where the polls will be located, what specific sites will be used, and how those sites are set up.

For many Americans, voting in person is their primary experience with elections. Voters experience ease or difficulty finding and accessing their polling site, efficient visits or long wait times, and clear or confusing procedures and navigation. Behind these voters’ experiences are design decisions election administrators make in selecting polling sites, ensuring proper access for all voters, and creating layouts of the sites and signage for efficient flow of voters through the ballot casting process.

⊳ A polling site set up in a train station in Virginia.

Where should we place voting sites to maximize access?

Election officials begin designing the voters’ experience when they select where the polls will be located and what specific sites will be used.

Officials have many constraints and design decisions when picking a polling location. One consideration is if the site is accessible—it must have adequate parking, public transportation options, and compliance with disability access regulations. They also look at whether the space can accommodate anticipated voter turnout by analyzing population density, demographic data, and historical voter

turnout. Security and logistical considerations are also taken into account to ensure the safety and smooth functioning of polling places. Overall, the process involves collaboration with various stakeholders, including community representatives and advocacy groups, to make informed decisions that promote transparency, inclusivity, and democratic participation.

Examples of potential polling sites

▲ (top) A former one-room schoolhouse in Story County, Iowa.

⊲ (right) A garage in San Francisco, California.

⊳ (opposite) Su Nueva Laundromat in West Lawn, Chicago, Illinois.

The USC Center for Inclusive Democracy’s “Voting Location and Outreach Tool” is an interactive web-based mapping system that identifies areas within a half mile where voting locations will likely have the most success in serving voters, based on customizable criteria.

The Center for Inclusive Democracy: “Voting Location and Outreach Tool”

How can we effectively use polling site space to serve voters?

The physical design of voting sites impacts the voting experience and efficacy.

Design of the arrangement and flow of polling places play a key role in the voter experience. The placement of materials, the stages of the voting process, and the flow of voter movement throughout the space can impact the time it takes to vote and ultimately the voters’ confidence in the election.

▲ ⊲ The State Farm Arena in Atlanta, Georgia served as an official early voting location for Fulton County in 2020. This huge polling site was created in partnership with the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks team. The arena was configured with hundreds of ballot-marking devices to serve voters.

The flow of voters must be considered to create an intuitive and efficient voting experience. Considering the layout of the site in advance, and providing guidance to poll workers who often set up sites, can significantly improve the in-person voting experience and overall efficiency of a polling location.

A

Tools can be used to help design the layout of the room and the flow of voters throughout the space. For example, the University of Rhode Island’s URI VOTES Polling Location Diagrams tool allows officials to plan layouts and create models of voting environments. These models can then produce simulations of process flows and diagrams to guide the set-up.

URI VOTES Polling Location Layout Diagrams Tool

⊲ A polling site set up in a gymnasium in Guilford, New Hampshire—with layout, signage, and wayfinding to organize and direct the voting process.

How can we design sites for greater accessibility?

All voting sites must accommodate those with physical disabilities and conform to ADA standards.

The vast array of types of places and buildings used, and the temporary pop-up nature of polling sites, present the challenge of evaluating and adapting each polling location.

To the right, an overhead view of a polling place shows accessible routes and maneuvering space, from the U.S. Department of Justice ADA Checklist for Polling Places document.

⊳ A voter checks in at a polling location in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

U.S. Dept of Justice ADA Checklist for Polling Places

How can we best guide voters through the voting experience?

Don’t underestimate signage and wayfinding communications.

The voter experience is impacted by the clarity and confidence in their required actions. Visual and physical communication in the space can greatly reduce confusion, decrease wait times, and reduce the verbal communications load on available site staff. Proper signage throughout polling sites and wayfinding tools (like tape on the ground, posts and barriers, color coding, and notations of different zones for different tasks and different people) are important tools for this communication.

Examples of elections signage

(clockwise from top) Signage for curbside voting in North Carolina; an early-voting site in DeKalb County, Georgia; a voting site in Gwinnett County, Georgia; a drop-off site in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; inside the polling site on primary day in Wisconsin; signage at the voting tabulator in North Carolina; a multilingual “next” sign in Gwinnett County, Georgia.

Voter Registration & Communication

In order to participate in elections, voters must be registered and keep their registration data up to date. Local election officials must also communicate with the voters in their jurisdiction on the information needed to navigate voting procedures and deadlines.

Election officials are in communication with the public throughout the year to engage people in registration, inform voters of upcoming elections, share specific details of where and how to vote, and notify people of many other aspects of elections. Voter registration is a central piece of this voter engagement. Providing opportunities to register, reducing unnecessary complexity, and eliminating errors are all opportunities for good design to shine.

⊳ A drive-through voter registration site in Ohio. Drive-through registration adds another option for voters, in addition to walk-up, mail-in, and online registration.

How can we design materials that allow voters to register successfully?

Government forms can get complicated, and voters can miss mandatory fields necessary to register successfully.

The intentional graphic design of forms—specifically around logical flow, well-defined headings, and clear instructions where needed—can make a big difference in supporting voters. Many of the design principles used for physical voter registration forms apply to their virtual counterparts as well.

The example shown illustrates how a voter registration application can be redesigned for greater usability and accuracy.

ORIGINAL FORM

The Center for Civic Design provides an excellent guide for designing forms.

The Center for Civic Design’s guide

AFTER RE-DESIGN

Left justification for easier readability

Important instructions at the top

Pennsylvania Voter Registration Application & Mail-in Ballot Request

If you answer “No” to either question, you cannot register to vote. Are you a citizen of the U.S.?

Will you be 18 years or older Yes No on or before Election Day?

Form is grouped by numbered sections

Instructions provided in relevant sections

Required and optional sections clearly labeled for accessibility SIDEWALK

Phone and email are optional and may be used to contact you about important information.

address If you do not have a street address or a permanent residence, use the map on the back. Students, see instructions.

(not P.O. Box)

Same as above

If you have a PennDOT number you must use it. If not please provide the last four digits of your Social Security number. See Verifying your identity.

Political party To vote in a primary, you must register with either the Democratic or Republican party.

If your name or address has changed Skip if this is the first time you are registering to vote.

(if

(if known)

Transfer my Annual Ballot Request (By checking the box, you are requesting that you continue to maintain your annual ballot request status when updating your address.) Identification

require help to vote. I need this kind of assistance:

If you check either of these boxes, your County elections office will contact you.

Titles for quick navigation and instructions to support voters. CURB

I would like to be a poll worker on Election Day. I would like to be a bilingual interpreter on Election Day. I speak this language:

Continue to next page. You must sign on the next page.

Separates form from sidewalk and can be colored to indicate required sections.

Where can we provide voters with registration opportunities?

Voting is both an essential right and responsibility that forms the foundation of our democracy. The gateway to voting is registration.

Having ample registration opportunities ensures that all eligible voters can participate in our democracy. It is important to provide proper access to voter registration. Ways to increase registration opportunities include: setting up registration booths in communities, hosting events, and providing navigable online resources.

Many election offices (and other organizations) work to meet prospective voters where they are. For example, shown below, the election office of Coconino County, Arizona sets up a mobile voter registration and polling location at the Grand Canyon to serve local voters—primarily members of the Havasupai Tribe.

▲ A mobile voter registration site and polling location set up at the Grand Canyon (Coconino County, Arizona and Havasupai tribal land) brings the tools to register to vote directly to rural voters who might otherwise have limited access.

⊳ A League of Women Voters registration drive at the Dodge Plaza Supermarket in Dodge Park, Maryland.

Washington DC's Board of Education set up a table for collection of voter registration forms and student election worker applications at Woodrow Wilson High School.

⊲ Vo+ER brings voter registration to healthcare settings through kiosks, QR codes, and provider badges. The program originated in 2019 at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and has expanded to multiple sites.

How can we help eligible voters register online?

Online voter registration can be effectively used to serve eligible voters in rural areas or those with accessibility requirements.

Online voter registration can steer voters to properly complete their application and not allow submission until the form is sufficiently completed. There are many

opportunities for design improvements to ensure that these forms are accessible to voters with disabilities. (Not all states offer online registration to their citizens.)

⊳ A voter registers online at the Travis County voter registrar’s office in Austin, Texas.

⊲ A voter registration promotion from the Tennessee Secretary of State prominently features the website address along with a scannable QR code.

How do we keep voters informed about elections?

Election offices communicate with voters to ensure they are informed and prepared to participate effectively in the electoral process.

Relevant details about upcoming elections, such as election dates, polling locations, and available voting methods are crucial for helping voters plan their participation and avoid confusion, especially when there are changes to polling sites or when new voting methods, like early voting or mail-in ballots, are

introduced. Election officials have adopted various approaches to communicate with voters, especially in response to the challenges posed by changing voter behaviors and the need to engage diverse populations. Effective design in these communications is essential.

▲ Snohomish County in Washington designed a comic book series that they integrated into their general election mailing information, which was an effective way to engage voters.

Direct Mail

Election officials use mailings to ensure voters receive essential information about the voting process directly at their homes. They may send out a variety of materials, including voter registration cards, sample ballots, polling place notifications, and reminders about upcoming elections. Designing these mailings with clear layouts, bold headings, and easy-to-read fonts ensures that the information is easily accessible and understood by all recipients.

Websites

Hosted at the state and local level, websites provide a centralized location where voters can access important information from trusted sources. Some offices have developed interactive websites where voters can enter their address to receive personalized information about their polling place, sample ballots, and

available voting methods. These tools often include features like polling place wait times and directions, making it easier for voters to plan for Election Day. The design of these portals is crucial, often featuring user-friendly interfaces, clear navigation, and multilingual support.

Text Messages

To reach voters directly, some election officials have implemented text messaging campaigns that send reminders about registration deadlines, early voting dates, and Election Day. These messages are often timed to coincide with key dates in the election cycle and can include links to additional resources or information. The simplicity and directness of text messages make them a powerful tool, especially for reaching those who may not regularly check traditional mail or email.

▲ Examples of voter education through text messaging from Nassau County, Florida used to disseminate important details about an upcoming election.

Social Media

Social media can be used to share real-time updates, reminders and educational content. These communications often need to be even more concise and visually engaging, utilizing infographics, videos, or interactive elements to grab attention in a crowded digital space. These campaigns are often designed to be easily shareable, helping to spread accurate information quickly and widely.

Videos

Election officials use videos to inform voters in ways that static images or direct mail cannot. Unlike static materials, videos can combine motion, sound, and visual storytelling to create a more engaging and comprehensive learning experience. For example, a video can demonstrate the step-by-step process of filling out a ballot, showing voters exactly what to do,

which is more intuitive than written instructions alone. Videos also allow for the use of dynamic elements like animations to highlight key information or clarify complex procedures, making them particularly effective for conveying instructions or addressing common voter questions.

Webinars

To engage voters in a more interactive way, some election offices have hosted virtual town halls or webinars where voters can ask questions and receive real-time answers from election officials. These sessions often cover topics such as voter registration, absentee voting, and Election Day procedures. The use of live video and chat features allows for a more personal and direct communication channel, which can be particularly effective in addressing voter concerns and misinformation.

⊳ Hillsborough County in Florida developed a series of informational videos to helpvoters understand the mechanics and administration of elections.

Election Worker Engagement

Election workers are essential to our election process.

Election workers (also referred to as poll workers, election judges, or election volunteers) are at the front lines of our democracy. Typically part-time employees or volunteers, they are recruited and trained to support voting processes during elections including but not limited to: setting up voting equipment, verifying voter eligibility, and providing ballots.

With increased early voting and other unexpected challenges, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, there’s additional demands on, and for, poll workers across the country.

⊳ Poll workers process mail-in ballots in Pennsylvania.

How can we attract and recruit election workers?

Recruiting temporary election workers is a continuous need each election cycle.

While some workers return from previous elections, typically election offices must recruit prior to each election. Offices have launched myriad efforts to recruit poll workers and volunteers. Some offices need to focus on finding enough people to staff each election; others are working to find poll workers with particular skills or experiences.

Many jurisdictions have had success recruiting high school students to be poll workers. Harris County, Texas received an EAC Clearie award in 2020 for its recruiting, retaining, and training of election workers. They have a dynamic student-focused program, with 280 students serving in the last election. They also take the time to thank their volunteers.

▲ An Instagram post from the Harris County election administrator’s office recruiting election workers.

⊳ A tweet from the Harris County election administrator’s office thanking poll workers.

⊳ (opposite) High school students working as election workers in Harris County, Texas.

How can we design training of election workers to be engaging and effective?

By employing thoughtful and strategic design practices in poll worker training, election authorities can ensure that poll workers are well prepared, confident, and equipped to handle the many responsibilities of facilitating a smooth and successful election rather than feeling inundated with information and overwhelmed. Design plays a critical role in conveying complex information in a visually appealing and understandable manner, and in creating engaging training experiences that enhance the learning experience and improves the retention of information.

IT expert for Georgia Votes, Roger Browning trains poll workers on how to use the voting machine in Jasper, Georgia.

Both training in advance and guidance in the moment are critical in supporting election workers. San Francisco’s Poll Worker Manual is a good example of a clear and helpful guide. This is supplemented with a number of helpful videos for specific tasks and issues.

San Francisco poll worker training resources

Job cards specific to roles and a single activity

Each activity is broken into small, defined tasks

Different colors to differentiate items

Illustrations demonstrate tasks within each activity

Clear directions for multiple what-if scenarios

How can we celebrate election workers?

Celebrating election workers is an essential way to recognize and appreciate the hard work, dedication, and commitment they put into ensuring the integrity and smooth functioning of the electoral process.

Some election offices demonstrate their gratitude for their election workers with some or all of the following: social media posts publicly thanking them for their work; encouraging members of the community to write thank-you notes; catered meals on

election day; awards ceremonies recognizing outstanding election workers; post-election potlucks or gatherings to build a sense of camaraderie; and gifting tokens of appreciation such gift cards, pins, or badges.

Examples of ways to thank election workers

⊳ A Poll Worker Appreciation Day event in Forsyth County, Georgia.

⊲ (top) Pins can commemorate each election year and show appreciation for election workers. Pins from San Bernardino County, California shown here.

⊲ (bottom) A poll worker event in Cole County, Missouri. Gathering around food is always a welcome tradition.

Ballot Design & Collection

Whether voting in-person or by mail, the majority of voters cast their votes on paper ballots. Those ballots must be designed for voters to understand and correctly mark the votes of their choice. And for mail-in voting, particular consideration must be given to how to properly collect completed ballots.

Voting with a hand-marked ballot remains the most common way to vote in the U.S. Almost 70 percent of Americans voted this way in 2022, according to Verified Voting, an organization that tracks voting technology. Elections often have many races with many candidates listed for each. Ballots need to be designed well to support voters in casting their votes as intended. (Similarly, electronic voting systems must be designed with clarity.)

With more and more voters opting to get their ballot by mail, we also have to consider how those ballots get returned for counting. All states now have at least some vote-by-mail processes. Some states (eight states and Washington D.C. as of 2024) have all-mail elections, meaning every registered voter is mailed a ballot for each election.

⊳ A voter in Sandwich, Massachusetts deposits his mail-in ballot in a drop box.

How can we help voters easily navigate the ballot?

Good ballot design aids voters in exercising their vote as intended.

What a ballot looks like, what it contains, and how a voter marks their selections can vary depending on what state, or even what local jurisdiction, you live in. While the ballot’s design is often determined by state law, or bound by the perimeters of the

voting equipment, there are some things that an official can still influence, including the final layout, the wording of voting instructions, even the colorcoding of ballot styles.

At the beginning of the ballot, explain how to change a vote, and that voters may write in a candidate.

Use clear, simple language.

Make instructions and options as simple as possible.

Do not include more than two languages.

If possible, summarize referenda in simple language alongside required formats.

Simple language is often shorter,

How can we design ballots and voting methods that are accessible to all types of voters?

Designing ballots that are accessible to all voters is a fundamental aspect of ensuring an inclusive electoral process.

Braille ballots allow blind voters to exercise their right to vote privately and independently. Largeprint ballots aid voters with low vision by providing clear and easy-to-read text with enlarged fonts and well-contrasted colors. Additionally, under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, jurisdictions with substantial numbers of individuals who are limited English

proficient (LEP) must provide voting materials in languages other than English to ensure meaningful access to the electoral process. As a result, many jurisdictions provide ballots in multiple languages, including Native American languages spoken by tribal communities in specific areas.

⊳ A tweet from the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office noting the use of braille and large-print ballots.

For some voters, such as overseas and military voters, time and distance prevents them from receiving and mailing their ballots such that they arrive in time to be counted. The Federal Voting Assistance Program serves such voters to allow them to vote abroad.

Federal law requires that every state provide services for eligible voters overseas, both military and civilian. These voters are often referred to as UOCAVA voters, based on the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (1986). Local election officials play a central role in supporting and serving these voters by providing voting information by mail and electronically;

many states allow overseas voters to return their ballot electronically. This voting population faces the challenges of time and distance in participating in an election—from a submarine traveling the depths of the ocean to the space shuttle circling the Earth—election officials still make sure overseas voters’ voices are heard and their ballots counted.

⊳ A service member browses through the Federal Voting Assistance Program website.

The Federal Voting Assistance Program, a non-politically affiliated organization, informs soldiers about upcoming elections and the election process.

⊲ NASA astronauts can transmit their votes from space, via the Space Center, to the county clerk responsible for casting the ballot. Here, Kate Rubins is shown on the International Space Station where she cast her vote in 2020.

How can we offer voters ways to successfully return their ballots?

An increasing number of voters are receiving their ballots by mail. Those voters need to properly return their ballots, and election offices must securely and efficiently collect those ballots for processing.

There are multiple ways for voters to return their completed ballot, including through the USPS, at their local election office, at a polling place, or at a designated ballot drop-box location. Creating these options, and also conveying specific procedures and restrictions to the voter effectively can impact their understanding of

▲ A voter drops their ballot off in Johnson County, Iowa.

⊲ A ballot drop box located outside of Boston City Hall.

⊲ (opposite page) An official ballot drop box in Olmstead County, Minnesota.

the process and their ability to successfully navigate the requirements. All states allow for completed ballots to be mailed back, but there is variation in when they have to be received. All states also allow for in-person return of ballots, but there is variation in when, where, and who can return them.

How can we design secure and efficient drop boxes for ballots?

Ballot drop boxes have different regulations associated with them. Depending on the state, they may be supervised or recorded through security cameras. The design of ballot drop boxes prioritizes security and efficiency in both ballot drop-off and retrieval.

⊲ An example of a well-designed official ballot box, from Los Angeles County, California.

Sloped edge to protect ballots while being removed in rain

Opening slot designed to be limited only to ballot entry

Angled entry slot to prevent liquid entry

Multi-lingual instructions provided

No grip points or openings for security

Distinct colors used to provide higher contrast for visual accessibility

How can we design vote-by-mail systems to serve voters and allow efficient processing?

There are a number issues to consider in vote-by-mail systems: increasing voters’ understanding and trust of procedures, complying with US Postal Service mail handling requirements, and ensuring election offices can receive and process ballots efficiently. Well-designed return envelopes actually do a lot of work by addressing all of these issues, at least in part.

While it may seem to be of minor importance, the design of return envelopes can make a big difference in the success of voting by mail. Voters sign envelopes to attest to their identity; this signature is matched to signatures on file to verify authenticity. If a voter neglects to sign or leaves out other required

information, the ballot is rejected. Rejected ballots result in voters not having their votes counted, or at least cause additional election office work to cure the ballots (if allowed by state law). A well-designed envelope can drastically reduce voter mistakes and resulting rejected ballots.

Voting-by-mail envelopes are an essential part of the voter experience. Typically, both an outgoing and return envelope are sent by local election officials to eligible voters. Their optimal design not only ensures quick delivery and efficient processing, it also streamlines the voting experience.

An example return envelope prepared by the Center for Civic Design.

Different colors for different envelope types (e.g., Outgoing/ return)

Well-spaced, multilingual Instructions

Sign the voter’s declaration in your own handwriting?

Put your ballot in the envelope?

Revise si…

¿Firmó la declaración del votante con su propia letra?

¿Colocó su boleta electoral en el sobre?

If you are unable to sign, make your mark and have a witness sign below: Si usted no puede firmar, haga una marca y haga que un testigo firme abajo: Witness, sign here Testigo, firme aquí

Voter, sign here in ink. Votante, firme aquí con tinta Power of attorney is not acceptable. No se aceptan poderes notariales.

• Declaro bajo pena de perjurio que esto es verdadero a mi leal saber y entender. Debe firmar en su propria letre. Su firma debe coincidir con la firma en su tarjeta de registro de votante. Votar dos veces en una elección es un crimen.

Date / Fecha (MM/DD/YYYY) Print name / Imprimir nombre te Print your voter registration address / Imprime tu dirección de registro de votante Declaración del votante Yo declaro que: Soy residente y votante en el condado, y la persona cuyo nombre aparece en este sobre. No he solicitado, ni solicitaré una boleta electoral de voto por correo de ninguna otra jurisdicción en esta elección.

• I declare under penalty of perjury that this is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. You must sign in your own handwriting. Your signature must match the signature on your voter registration card. Voting twice in an election is a crime.

• I have not applied, nor will apply for a vote-by-mail ballot from any other jurisdiction in this election.

• I am a resident of and a voter in the county, and the person whose name appears on this envelope.

declaration declare that

Postal and election requirements for layout fulfilled

Intelligent barcodes for tracking

Making ballot envelopes clear and understandable: The impact of plain language on voter signature forms

Making Ballot Envelopes Clear and Understandable by S. Johnson and W. Quesenbery, Center for Civic Design (2021)

Processing & Reporting the Vote

After votes are cast comes the considerable work of transporting, tracking, and counting ballots. Election offices then report the results, first releasing preliminary unofficial results and eventually the official final results.

All cast ballots must be processed: their eligibility authenticated, votes counted and accounted for, and votes included in the results. This must be done securely, transparently, and accurately. Some ballots are counted centrally while others are counted at the polls. Ballot processing can have many stages and should have a documented chain of custody, quality controls, and auditing policies. Finally, the vote counts must be reported. For every election, not just Presidential Elections or elections with a close race, election professionals follow the same procedure to ensure that all eligible ballots are included in the final results. All this is done with the public and media awaiting announcement of the official winners.

⊳ Absentee ballots are opened, reviewed, and processed in a vote center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

How can we organize the stages of ballot processing for efficiency?

Perhaps overlooked by the public, the work to collect and process ballots is a significant undertaking. This system is designed for efficiency, tracking, and security, and has opportunities to continue to improve and adapt to new laws and regulations in each jurisdiction.

Ballots come from various sources, including in-person voting and via mail. Mail-in ballots will be removed from their return envelopes, flattened, and readied to be scanned and counted.

Once cast, ballots undergo a thorough verification process to confirm their legitimacy and compliance with legal requirements. This verification includes

confirming the voter’s eligibility, matching signatures, and ensuring the absence of any irregularities. Following verification, the ballots are counted, a process that can involve manual counting, machine tabulation, or a combination of both depending on the jurisdiction.

⊳ Printouts of the final paper tape, listing results of voting from locations in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Election workers review the results and sign off.

⊲ Bins in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to hold and store absentee ballots. Incoming ballots are sorted and stored until they are scanned, and votes are counted.

How can we design systems to transport and process ballots securely?

Ballots cast in-person at local polling place must be collected, sorted, and transported to central sites for counting. This must be done securely and with a system to record and ensure that security.

The standard way to ensure the security of ballots is a “Chain of Custody.” A successful Chain of Custody provides a documented and unbroken trail that tracks the movement and handling of ballots, from the moment they are cast to the point where they are counted and results are determined. This meticulous process involves a series of carefully recorded steps, often under the supervision of bipartisan election officials, to prevent tampering or

unauthorized access to the ballots. Throughout this chain, ballots are sealed, signed for, and securely transported between different stages, including collection, verification, counting, and storage. By maintaining an unbroken Chain of Custody, election authorities can confidently demonstrate the legitimacy of the results and safeguard against any potential challenges to the accuracy and fairness of the electoral process.

⊳ Cast absentee ballots are delivered to a polling site for processing, by a police officer in Chelsea, Massachusetts.

▲ (clockwise) Tamper-evident seals on voting machines and election materials are removed when setting up a polling site in Virginia; a signed envelope showing Chain of Custody, in Wisconsin; ballots from drop boxes delivered to the Department of Elections in Massachusetts; Chief Deputy City Clerk signs the date and time he emptied a ballot drop box in Michigan.

An example of the Chain of Custody

The transport and transfer of election materials is carefully controlled and documented by local election officials.

The process begins after voters turn in their ballots

Chain of custody record created:

• Label ballot container

• Seal container

• Record: authorized personnel, seal number, location

Ballots are transferred

Ballots are secured Ballots are prepared for transfer:

• Inspect Seal on ballot container

• Record: container condition, personnel name/signature, new location

New chain of custody information is recorded: CHAIN OF CUSTODY IS MAINTAINED

• Authorized personnel

• Container label

• Seal number

• Current location

How can we provide the public with transparency into how votes are counted and recorded?

Engaging with the public during ballot processing is a critical step toward building confidence in our democratic system.

Transparency of election processing necessitates effective observation, but watchers and observers need to understand what they are seeing. Color-coding, consistent use of descriptive icons, and sequencing of stages can help demystify the process. With the growing use of live-streaming as

a way to observe vote counting, the inclusion of proper signage is essential so those viewing online can better understand their elections. Election officials must also design a viewing layout that allows for meaningful observation without compromising ballot security.

There are a number of measures election administrators can design and implement to increase transparency in vote counting, leading to increased trust in elections.

Clear Signage

Directing election observers through the processing center in a streamlined manner ensures that processing continues efficiently while allowing public transparency over the process.

⊲ Yellow tape used to clearly mark areas where ballot observers can watch from at the Salt Lake City, Utah ballot processing center.

Designated Places

Ensuring that the observation is kept separate from the processing maintains the security of the ballots. Observation areas can be integrated into the center by creating designated pathways.

Remote Screenings

Several polling stations set up video cameras at different parts of the processing center, allowing observers to review proceedings in a location that is physically distinct from the processing center.

⊲ Video surveillance records various areas where ballots are located at the Jefferson County elections office on Oct. 21, 2020.

⊳ (opposite page) Election observers in Las Vegas, Nevada watching ballot counting.

How can we set the right expectations for when a race could be called?

Reporting results to the public and media—in addition to official channels—is a critical role of election offices.

Is the election over when the polls close? Absolutely not—not in any state. Although voting has ceased, votes are still being processed, counted, and tallied until all eligible votes are accounted for. On election night, election officials release the unofficial results of what has been counted and tallied at that time. It is standard that additional information is reported concerning the percent of precincts that have come in or the volume of outstanding ballots yet to be counted.

With this information, if the margin of victory appears to be wide enough the media will project who they believe the final winner will be. If the race

is close, projected winners will not be declared by the press until more votes are counted and tallied. Regardless, the only declaration that really matters is the official final result that is reported out by the election officials—which usually occurs with very little fanfare.

While we might want immediate resolution of an election, there are many factors that influence when a race can be called. Every state has laws concerning when the scanning can occur, when those counts can be tallied (accumulated), and when initial, unofficial results can be released. This influences their timetable to report results.

⊳ A graphic of the elections returns timeline from the Pennsylvania Department of State, in 2022. Note how it communicates the dates of the basic sequence to count and report votes.

Different states have vastly different rules and procedures for processing ballots and tabulating votes. Understanding this helps explain why we see election results coming in from different states at very different timelines. The graphic below shows timelines of a number of different states, which

illustrates how the varied laws create different starting lines for states to complete their vote counting. This disparity, in addition to factors such as differing number of ballots cast and the capacity to count votes in each jurisdiction, creates the uneven reporting counts we experience.

⊳ A New York Times graphic shows preprocessing and tabulation for various states for the 2020 Election.

Results reporting gets a lot of attention. A lot. This is where concise, informative design really shines.

Website dashboards, mapping graphics, and historical overlays can convey where a particular race stands, who the eventual winner will be, and who has voted. Not all election offices have websites, and not all elections websites have the capability to satisfy modern information needs as many offices don’t have their own IT staff to support them. In fact, roughly a third of our election offices don’t have a full-time staff person.

The Election Assistance Commission (EAC) supports election offices, including with guidance in reporting results. Below is an EAC guide outlining principles for effective results reporting. The image on the right shows a Yolo County, California reporting page, with many of these principles implemented.

that appears in place of an image on a webpage to help screen-reading tools describe images to visually impaired readers. Learn more: https://www.section508.gov/create/synchronized-media/ Section 508 Compliance - Section 508 is a federal law mandating that all electronic and information technology developed, procured, maintained, or used by the federal government be accessible to people with disabilities. Learn more: https://www.section508.gov/test/web-software/

▲ A guide from the Election Assistance Commission illustrating the many ways an Election Result site can help communicate information to the public. From the EAC: “The election results reported on election night are never the final, certified results. Election officials well know there are various other steps and factors that impact when election results are final. Communicating that information with the public can be a challenge. . . . How election officials display election results can play a key role in facilitating public confidence in election outcomes.”

A Best Practices Guide for Election Results Reporting Websites from the Election Assistance Commission.

▲ A screenshot of an Election Results map from the Yolo County Elections Office (California), using the ArcGIS geographic information system platform.

Conclusion

We hope this booklet has highlighted the critical role that design plays in many aspects of election administration, from the moment a voter registers to the final counting of ballots. As discussed, thoughtful design influences the effectiveness and accessibility of polling site selection and layout, the clarity and impact of voter registration and communication efforts, the engagement and efficiency of election workers, the usability of ballots and the integrity of their collection, and the transparency and accuracy of vote processing and reporting. Each of these areas demonstrates how well-considered design can make the voting experience more intuitive, inclusive, and secure for all participants.

For students studying design, we hope this booklet serves as an invitation to consider how their skills can impact the civic sphere. As they develop their careers, they can explore opportunities to work in public service or collaborate with organizations focused on improving election systems. They can also engage in projects that address real-world challenges in election design, from creating accessible voter guides to redesigning the user experience of voting technology. By applying their talents to election administration, design students can help ensure that the future of voting is not only more accessible and efficient but also more empowering for all citizens.

For designers, we believe they have a unique opportunity to contribute to the improvement of election infrastructure. Designers can collaborate with election offices to create more user-friendly interfaces for online voter portals, design ballots that reduce errors and confusion, and develop communication materials that resonate with diverse audiences. Designers can also work to create systems that are not only functional but also more voter centered. By lending their expertise to this critical area, designers can play a significant role in strengthening democracy.

For election officials, we hope they will see the work they do in a new light—many of their efforts can already be seen as being design work. As we look to the future, it’s crucial to continue integrating and expanding the role of design in election administration. There is still tremendous potential to innovate, improve, and ensure that our elections are as accessible, efficient, and secure as possible. By embracing a human-centered approach and leveraging modern design tools, election officials can continue to create systems that better serve the needs of every voter. Ultimately, we each have a unique role to play in ensuring a safe, transparent, and trustworthy election in the United States. By all working together, we not only ensure successful elections, but also that the democratic process truly engages and reflects the voice and will of the people.

About this book

The “Election Administrators / Election Designer” exhibit and this accompanying booklet were created by Nadia Roumani, David Janka, and Thomas Both from the Stanford University Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (aka, the d.school) in collaboration with senior advisor, Tammy Patrick. The team also included the d.school’s Election Innovation Corp students.

We are sharing this exhibit under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (CC BY-NC 4.0), which enables others to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the work for non-commercial use—other than Sue Dorfman’s photos, for which rights are outlined below.

Image credits

Photographs, unless otherwise noted, copyright © by Sue Dorfman: Sue Dorfman’s photos are shared under Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), allowing people to download and distribute the work, but not commercially, and they must attribute the original work and may not create derivatives.

All photographs are by Sue Dorfman with the exception of those listed below.

The Elections Administrator Competencies Wheel visual created by The U.S. Election Assistance Commission (pg 8).

A sample elections calendar spreadsheet created by The Elections Group (pg 10–11).

Staff picture of Dubuque elections staff, courtesy of Dubuque County (pg 12).

Staff picture courtesy of Doña Ana County Elections Bureau (pg 13).

Design practices icons via The Noun Project (pg 14).

Photo of laundromat polling site, Ryan Donnell, Smithsonian Magazine (pg 18).

Photo of schoolhouse polling site, Ryan Donnell, Smithsonian Magazine (pg 19, top).

Photo of garage polling site, Jessica Christian, San Francisco Chronicle (pg 19, bottom).

Screenshot of the “Voting Location and Outreach Tool”, from The Center for Inclusive Democracy (pg 20–21).

Screenshot of the URI VOTES Polling Location Layout Diagrams tool, from The University of Rhode Island (pg 24).

Image from the ADA Checklist for Polling Place, U.S. Dept of Justice (pg 26–27).

Images of Pennsylvania Voter Registration Application forms, Pennsylvania Department of State, via The Center for Civic Design (pg 32–33).

Photo of voter registration drive, League of Women Voters of Prince George’s County website (pg 34)

Photo of Grand Canyon registration site, Bri Cossavella, Cronkite News (pg 34).

Photo of Vo+er kiosk, Einstein Medical Center, featured in Philadelphia Magazine (pg 35, bottom left).

Photo of Vo+er badge, Dr. Alister Martin and Dr. Ashlee Murray (pg 35, bottom right).

Photo of voter registering, Austin AmericanStatesman (pg 36, top).

Image of voter registration promotion, Tennessee Secretary of State (pg 36, bottom).

Images from Snohomish County Official Local Voters’ Pamphlet, County of Snohomish Elections Office (pg 37)

Images of Nassau County voter education texts, US Election Assistance Commission 2023 Clearie Awards (pg 38)

Images of Hillsborough County voter education video, Vimeo (pg 39)

Photo of election workers, Jen Rice, Houston Public Media (pg 42).

An Instagram post from the Harris County Elections Administrator’s Office (pg 43, top).

A tweet from the Harris County Elections Administrator’s Office (pg 43, bottom).

Images from San Francisco’s Poll Worker Manual, City and County of San Francisco (pg 46–47).

Photo of a Poll Worker Appreciation Day event, Forsyth County website (pg 48).

Photo of election pins, from San Bernardino County Elections tweet (pg 49, top).

Photo of a Poll Worker Appreciation Day event, Cole County (pg 49, bottom).

Sample images from The Center for Civic Design Field Guides (pg 53).

A tweet from the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office (pg 54).

Photo of service member on the Federal Voting Assistance Program website, Defense Visual Information Distribution Services (pg 55, top).

Photo of NASA astronaut, NASA (pg 55, bottom).

Image of Los Angeles County Ballot Box, Los Angeles County Registrar (pg 59).

Images of Franklin County ballot envelopes, via The Center for Civic Design (pg 61).

Chain of Custody icons via The Noun Project (page 67, bottom).

Photo of Election observers, Bridget Bennet, The New York Times (pg 68).

Photo of yellow tape marking areas in the Salt Lake City ballot processing center, Trent Nelson, Salt Lake Tribune (pg 69, top).

Photo of video surveillance monitors, Eli Imadali, Colorado Newsline (pg 69, bottom).

Election Returns Timeline graphic, Pennsylvania Department of State (pg 70).

Graphic of vote processing timelines, The New York Times (pg 71).

Image from A Best Practices Guide for Election Results Reporting Websites, Election Assistance Commission (pg 72).

Screenshot of an Election Results map, using the ArcGIS platform (pg 73).