‘Education for today and tomorrow’

‘Education for today and tomorrow’

Iam delighted to introduce this term’s Teaching & Learning bulletin, which recognises the efforts of the energetic and innovative ECT community at St Dunstan’s College.

Year 1 ECTs have completed a literature review on a topic linked to their chosen area of focus. Year 2 ECTs took this slightly further and used published research to shine a spotlight on a particular conundrum they may have with a particular group. Collectively, their studies cover a range of topic from metacognition, to questions around curriculum, to strategies that support positive behaviour for learning.

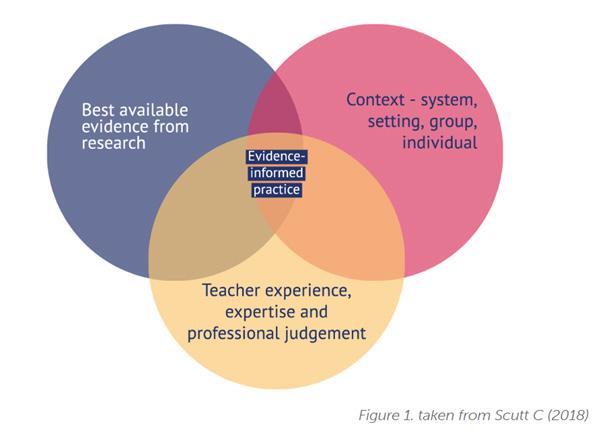

Our school vision for Teaching & Learning is one that is evidence informed. This includes not only evidence from published research (of which our ECTs make great use here), but also evidence from our own context in an academicallyselective, coeducational setting in south London, as well as evidence from our own experience, expertise and professional judgment.

The projects summarised in the following pages are a wonderful demonstration of all these roots of evidence coming together to enhance the experience of students and teachers in the school. This emphasises our school-wide journey of continuous improvement, knowing that we are building on the foundations of already excellent pedagogy.

A huge thanks to our ECT community and their mentors who supported them in these projects.

Each ECT will present their project at our inaugural ECT symposium, taking place in the Great Hall on the 24 of April from 1:30 pm. All staff are welcome to attend, as and when they are free that afternoon.

We will also be joined by the Director of Training from ISTIP, Amy Cooper.

Helen Riddle

Each ECT will present their project at our inaugural ECT symposium, taking place in the Great Hall on the 24 of April from 1:30 pm. All staff are welcome to attend, as and when they are free that afternoon.

Simone Arajian

Interdisciplinary planning and the benefits it can offer

Anna Biggs

Misconceptions: predicting them and overcoming them in Science lessons

Joseph Yu

I Touch, therefore I am: Object-based Learning

Zen Ng

Understanding praise and using it to increase engagement

Sophie Mitchell

Do it Now tasks - purpose and pitch with a lower set Maths class

Logan Blair

Promotong mastery through formative assessment

Ella Tournes

How does the structure of groupwork improve learning scores for Collaboration in a Year 9 class?

Luke Golding

To what degree does the atmosphere at the start of each lesson impact the overall quality of the classroom environment?

Charlotte Lucas

How does guided and timed practice aid revision or impact exam confidence?

Sian Reece

Reasons to become and examiner

Molly Pridmore

Making feedback effective

References

What is interdisciplinary planning?

Interdisciplinary planning involves intentionally integrating connections between the contents of different subjects for an improved understanding of the core problem. This differs from multidisciplinary education, which involves increased content being delivered from different subjects. By structuring programs to link both the contents and the concepts, full interdisciplinarity can be achieved, creating multi-skilled students.

By structuring programs to link both the contents and the concepts, full interdisciplinarity can be achieved, creating multi-skilled students.

What are the effects of interdisciplinary planning on literacy and student engagement?

This approach, when implemented across various subjects, has seen great effects in both pupil engagement and the improvement of literacy. It can aid students in forming a deeper and more analytical understanding of taught subjects, as well as allow connections to be formed across the subjects, which aims to promote clarity in the content. Research also recognises the benefit of this approach to the psychological development

of students which will in turn have positive impacts on their engagement. They can feel the satisfaction of applying knowledge from one subject into another independently, as well as improving understanding of the core content.

Michaelmas Box project:

• Percentage loss

• Timbers & sustainable material sources

Lent Pocket Puzzle:

• Crude oil & polymers

• Considering the 2D shape objects obtain in a space

Structures:

• Forces

• Natural and man-made structures

• Plan opportunities to create connections with other subjects

• Collaborate with other departments to sequence taught material within and across the years

• Keep taught content context-specific to avoid repetition

• Literacy can improve by students encountering terms in different disciplines and from different contexts

However, interdepartmental planning is vital to avoid setbacks. For example, teaching trigonometry in Design Engineering for a project before students learn the content through Maths can increase confusion and stress in students. Instead, the project can be taught after the students cover the chapter in Maths, increasing clarity and ability to independently apply the skills to solve the questions in both subjects.

• Revised from Year 7

• Revisited in Lent through Maths – Fractions, Decimals & Percentages

• Revisited in Lent through Geography - Energy Sources

• Revised from Year 7

• Revisited in later in Y8 through Physics Interdisciplinary education through practice

This table suggests some ways in which the Year 8 Design Engineering curriculum offers interdisciplinarity.

Misconceptions can arise in several ways:

• We form ideas based on everyday experiences

• We have an incomplete understanding

• We talk about things anthropomorphically

• Something seems logical

• We depict things in a certain way

• Everyday words with a specific scientific meaning can be confusing

Questions for teachers to consider:

• What particular areas of content are your highest priority for overcoming student misconceptions?

• How can you make planning to uncover and address misconceptions, routine?

• Where might you find opportunities to collaborate with colleagues to support effective planning for misconceptions?

• What can be put in place to help revisit and reinforce key concepts over time, particularly with content that is only in the curriculum every few years?

Key takeaways:

• Misconceptions can lead to errors that can build over time and impact further learning.

• Teacher knowledge of misconceptions and explicitly planning to uncover and address them is vital for supporting student learning growth.

• Many misconceptions are well known, and welldeveloped tools and resources are often available to support teachers to address them effectively.

1. Research/Anticipate - Consider common misconceptions before you teach

2. Diagnose/Address - Uncover misunderstandings and build on the ideas that children bring with them

3. Assess/Review - Revisit key ideas and make links with other topics

• Do It Now: Use DIN as an opportunity for interleaving. This provides opportunity to revisit concepts from last lesson, a week ago or a month ago, and to build connections across the curriculum. Create opportunities for learning across topics to return to specific ideas or misconceptions

• AfL: Use a variety of strategies for promoting higher order thinking skills, especially openended engagement activities and key questions. Make sure the activities you use clearly match your SLOs. Will the activities and key questions you have selected adequately address students’ misconceptions?

• Use examples & non examples when providing definitions: At the start of a new topic consider previous topics students will have covered. Use students’ prior knowledge to define whether they should start with definitions or examples. If students have no prior knowledge, then it is better to start with examples. If students have prior knowledge, then starting with definition is more efficient

• Mix up representations: When planning lessons, provide students with opportunity to draw out equations using shapes, names and formulas. Seeing the equations side-by-side will help students to better grasp concepts. Encourage students to transform information from one format into another e.g. text to flow chart, bullet points to mind maps or summarizing a paragraph in 10 words.

• Spot the error: Encourage students to rewrite the error correctly

“Cognito, ergo sum” (Descartes) encapsulates the importance of thinking and skepticism in classroom learning. But aside from conventional textual, oral and visual sources, the significance of tactile sensation in one’s awareness of existence and learning process is often overlooked.

Object-based learning provides students with tangible objects with which to interact, facilitating a deeper and more concrete understanding of abstract concepts. In History, for example, the concept of patronage in the Middle Ages could be taught through illustrated religious manuscripts. Through investigating the materiality and provenance of the manuscript, pupils would be able to understand how wealthy individuals or institutions commissioned works of art to demonstrate their wealth, power, and piety.

By engaging multiple senses, such as touch, sight, and sometimes even smell or sound, object-based learning also helps cater our teaching to diverse learning needs. It is particularly pertinent to SEND pupils. Having a tangible object to explore and process before introducing texts would help pupils attach meanings back to the semantics (words). Tangible objects also ensure whole-class active involvement in the learning process, fostering curiosity, motivation, and a sense of ownership over their learning.

“By engaging multiple senses, such as touch, sight, and sometimes even smell or sound, object-based learning also helps cater our teaching to diverse learning needs”

Furthermore, object-based learning can diversify the way we teach core subject skills. For example, when teaching source skills in History, artefacts have advantages over written sources because they often carry no conscious testimony. As the objects offer no easy answer to their provenance, teachers can guide pupils to question, analyse, draw connections and interpret these sources.

Common Challenges and how to overcome them:

• Obtaining a diverse range of objects for learning can be challenging, especially if schools have limited budgets

or lack access to relevant museums or collections. Educators need to think creatively to overcome this challenge. Podesta (2012) found it useful to construct a box of laminated pictures of artefacts and shredded paper to imitate the process of excavation. The nature of the replica gives the opportunity for teachers to add or remove specific information, such as historical facts, notes from archaeologists, to construct a framework for pupils to investigate the historical objects.

• Teachers should also integrate objects into the existing curricula to ensure that the use of objects enhances rather than detracts from the curriculum. Rather than teaching with objects in stand-alone lessons, teachers should aim to build an entire enquiry around objects and assess student learning. Indeed, the benefits of active involvement in experiences could only be realised if it was followed by reflection, conceptualisation, problem-solving, and experimentation (Kolb 1984). It is imperative that teachers complete this cycle, such as through write-ups to assess whether students could utilise the meanings they created from objects (e.g. Bird et al 2020: 42).

Summary

The experience of touching or feeling physical sensations is fundamental to our understanding of ourselves and our surroundings. I propose that as educators, we should not suppress our pupils their tactile sense, and instead should encourage and facilitate pupils to think through objects.

This summary is also available on Joseph’s personal blog: https://josephgregoryyu.wixsite.com/meetjoseph/blog

The problem: Multiple studies show decline in motivation, attendance and academic engagement as students move from primary to secondary. Some studies indicate that 40 - 60% of high school students are chronically disengaged.

One solution: Positive relationships with caring adults foster a sense of belonging and are the biggest factor in lowering dropout rates. Praise, when used appropriate and effectively, can be a useful tool in creating these safe spaces for students.

The question: How does research suggest we use praise?

However, praise can also have detrimental effects. Here are some ways of using praise effectively to support extrinsic factors which will developing intrinsic motivation in the long run:

Praise should be sincere and congruent with the child’s actions or achievements.

“I noticed how you helped your classmates with their projects. That was very kind.”

Emphasize the process rather than innate ability.

“I’m proud of how focused you were during your study session.”

Praise should be immediate and unexpected, serving as an occasional bonus rather than an expected outcome.

“Your attention to detail on this project paid off.”

Avoid dishonest praise, as insincerity can lead to dismissal of praise by the child.

“You’re a great student!” (When the student knows they didn’t perform well)

Avoid praising for attributes that may be perceived as fixed or immutable by the child. Avoid comparison.

“You’re the smartest in this class.”

Avoid overly predictable praise, as it may lead to the expectation of praise for every action.

“You always do such a good job on your assignments.”

Summary: Genuine praise, focusing on effort rather than innate ability, given occasionally and unexpectedly, boosts motivation and nurtures a growth mindset in students. This leads to an enhanced sense of belonging. Dishonest or attribute-focused praise may have negative effects.

I had been working hard at getting a low ability Maths set get settled at the beginning of the lesson and wanted to investigate the impact that the length of the starter had on the rest of the lesson after having a few focussed lessons with an extended starter. However, upon purposefully varying the length of the starter I found that this wasn’t the deciding factor on the rest of the lesson and so started to look into what it might be.

As Barton articulated there are three main purposes of a Do it Now task:

• To assess prerequisite knowledge

• To act as a retrieval opportunity

• To act as a settler

This is supported by Sherrington (2024) who identifies some of the main problems with Do it Now tasks. In his discussion, he affirms that a starter needs to be positive and builds confidence for the students. He also sets out that it shouldn’t be too long, as if the lower ability students don’t finish they already feel behind.

With Maths in particular, prior knowledge is important as it is a hierarchical subject; students are unlikely to be able to move on if they are struggling initially to solve equations.

1 Basic multiplication problems leading to percentages

2 Algebra questions extremely similar to ones completed in a recently.

3 Retrieval practice on fractions

Barton (2022) emphasises that if students know they are going to need this knowledge to help them access the rest of the lesson they are more likely to pay attention.

Based on this research, I made a few changes to my practice specifically with a Lower School lower ability set. These students continuously struggle with Maths and use common avoidance tactics to not participate.

Therefore, I implemented the following changes and noted down the observed impact (refer to table below):

• Do it now tasks tested the very basic knowledge that students needed for the lessons. When looking at negative numbers these questions went back to the basics of -5-8 to ensure that any misconceptions were addressed at the beginning.

• The starters are also pitched so that even the students who take longer can complete the majority; with optional extension questions available.

The following table summarises the lesson by lesson changes I made and the observed implications.

This starter was pitched very low as a fill in the blank task

Mid-level difficulty

Answers slowly put up on the board for students to self-check. Students were also informed the purpose of the starter was to check our knowledge was still accessible for a task next week.

Students were confused by the low level being tested and found this a topic which they wanted to talk to each other about.

Students got on with this work well however did ask if the lesson was going to be on algebra.

Students worked on these questions very well and the rest of the lesson was very focussed and settled.

I found that letting students know the purpose of the starter helped them to get on with it if it wasn’t relevant to the following lesson. I also found that pitching the starter at a medium to high level, with scaffolded support such as hints of certain answers revealed helped to keep students confident and engaged.

We know how to craft useful formative questions, allow students to have thinking time, and adjust our lesson trajectory based on students’ responses. But how do we promote students to actively participate in a teacher’s toolkit of questioning?

From the student perspective, there are two goals of participation: boosting ego or aiming for mastery. Ego-associated participation is rooted in a comparison to other students. Mastery-associated participation seeks achievement through deeper cognitive strategies. We should aim to promote mastery, which arises when teachers evaluate progress, provide opportunities for improvement, and vary their questioning methods.

1. Teacher poses a question: During a History lesson, the teacher asks, “Who can tell me the date when World War II ended?”

2. Student raises hand quickly: Sally eagerly raises her hand before others have a chance to think, hoping to be the first to answer.

3. Teacher selects Sally: The teacher acknowledges Sally’s enthusiasm and says, “Excellent! World War II ended on 2 September 1945.”

4. Class reaction: Sally beams, enjoying the recognition of being the first to answer correctly.

1. Teacher poses a question: During a Biology lesson, the teacher poses, “How does the introduction of an invasive species impact native biodiversity?”

2. Students think and respond: Students are allowed time to reflect, then write their extended answers.

3. Teacher supports Timmy: The teacher identifies Timmy, a student who may be reluctant to participate. They discuss his thought process and highlight strengths. When errors are found, the teacher provides clear instruction for improvement.

4. Class reaction: Timmy shares, “Invasive species disrupt ecosystems, threatening native biodiversity through competition and predation.” The teacher responds, “Connecting the dots across topics is really paying off!”

To lay the foundations of promoting mastery, students need a clear pathway toward reaching expected learning outcomes. How can we do this?

• Ensure students’ efforts are emphasised, as it prioritises their responsibility in their learning.

• Avoid minimising student effort by making comments that stray into pity, demonstrating over-the-top praise, or offering unsolicited help (n.b., remember students who may not voluntarily seek help!)

• Students develop a stronger motivation when they believe that their success is due to their own effort – praise the effort rather than the outcome.

How to use formative assessment to promote mastery

Once students complete a task, show a thumbs up, or write on a mini whiteboard, teachers can provide varying degrees of individualised feedback:

• In doing so, it is less effective to compare students’ responses, as it reduces the impact of a student’s own efforts.

• Instead, in your circulation of the room, aim to pinpoint target students and their accuracies and errors, clarifying alternative approaches to improve their skill.

• By seeing how their efforts improve learning, the student’s expectation for success is boosted, enhancing the masteryassociated participation cycle.

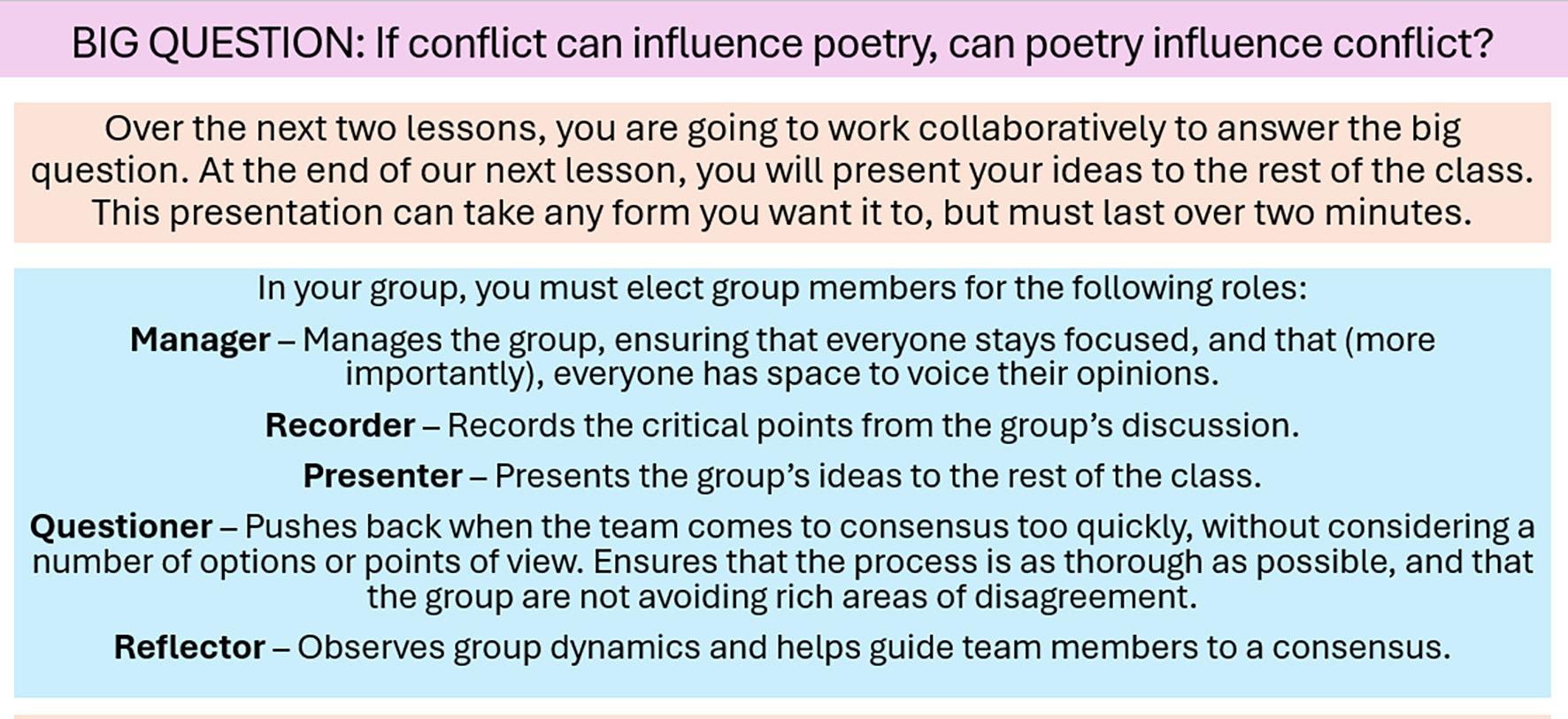

It is no secret that groupwork, when used ineffectively, has the propensity to engender a lack of engagement, accountability, and productivity in pupils. However, research suggests that, when groupwork is employed ‘optimally’, pupils can make an additional 6 months’ worth of progress on top of any given academic year. This seems like an obvious win, but what constitutes ‘optimal’ groupwork? How, as teachers, can we devise groupwork tasks that facilitate pupils in collaborating proactively and productively?

In surveys I conducted about the characterisation of effective groupwork, the word ‘structured’ was used by staff and students alike. To further my understanding of what ‘structured’ groupwork looks like in practise, I looked at Adam Boxer’s podcast, WUCTL, and the EEF. All three sources seemed fairly consistent in their characterisation of ‘structured groupwork’: the ideal group-size is between three and five; each member of the group must be given a specific role that they are held accountable for (see attached resource); sequencing and metacognition is crucial. Howe, on the TES Podagogy about Groupwork, asserts that effective groupwork does not come from a group of like-minded individuals who work harmoniously; the efficacy of groupwork in fact lies in thorough, well-managed group disagreements. This led me to the conclusion that groups should be teacher-selected to ensure a mixture of abilities and collaboration learning scores.

I also discovered that groupwork is generally more effective when it is enquiry-led: pupils are asked to come together to solve a problem, rather than complete a task. For this, I looked to KCL’s Accelerated Cognition Programme, inspired by Vgotsky

and Piaget. To devise the task, I adopted Piaget’s sequence of concrete preparation, social construction, cognitive conflict, then metacognition. Pupils were given a problem to solve in the form of a ‘big question’ but were encouraged to self-direct their research and discussions wherever possible.

Overall, I found that enquiry-led, structured groupwork has a positive impact on those receiving a 2 for collaboration in a Year 9 sample group of nine pupils:

• Across the series of lessons, the sample of pupils improved their learning scores by 0.7.

• Those who self-elected as Managers or Presenters all improved by 1 learning score on average

• However, those who elected themselves as Reflectors or Questioners did not improve at all.

• Interestingly, none of the sample group elected themselves as Recorders – those who did had an average learning score of 3.8.

• Student voice surveys indicate that 56% of the sample pupils felt more engaged compared to previous groupwork tasks, and 44% just as engaged. 56% felt more productive, 22% as productive as normal, and 22% less productive.

• Those who self-identified as being less productive had not self-elected as ‘Managers’ or ‘Presenters’.

The next steps in my action project will include analysing how more purposeful distribution of student roles impacts collaboration learning scores. I am also looking forward to applying more purposeful oracy structures after reading Didau’s ideas on the topic.

To what degree does the atmosphere at the start of each lesson impact the overall quality of the classroom environment?Luke Golding

The study stemmed from observations with my Year 9 class, where settling has previously taken longer compared to other groups I teach. Comprising 19 students, the class has a notable ratio of 17 boys to 2 girls, many of whom share close friendships. It makes an interesting class dynamic, inevitably friends sit beside one another, prompting mini conversations at the very offset of every lesson.

As students enter, they are instructed to get their equipment and book out and begin their Do It Now task. I have found the atmosphere from the bustling Maths corridor often seeps into my classroom, especially when the entire year group floods the narrow space. It can be noisy, with students catching up and laughing jovially, and teachers correcting behaviour and uniform. I am eager to transition my students from the corridor into the classroom to engage them mathematically at the outset of each lesson. This works simultaneously with clearing the corridor, helping to free narrow space to make passing easier.

Marzano’s “Classroom Management That Works” supports practical strategies for teachers to create an optimal learning environment. Marzano emphasizes clear expectations, positive relationships, and engaging instruction to foster student success. By implementing evidence-based techniques, educators can effectively manage behaviour and enhance academic achievement, promoting a positive classroom culture. At the regional ECT training seminar this year, Chris Moyes emphasized the importance of beginning with the end goal in mind. To establish a conducive learning environment throughout, it should be established at the very beginning of each lesson.

Begin with the end goal in mind. To establish a conducive learning environment throughout, it should be established at the very beginning of each lesson.

During Lent 2, I experimented by standing at the door, greeting the very first students to arrive, then closing the door once the first few were in. I then stood inside the classroom, visible through the door’s glass, greeting remaining students as they entered.

By closing the door earlier, it allowed for the very first students to attempt these questions in a quieter environment. The change to the beginning of each lesson appeared small yet provided valuable insight. Moyes also encouraged ECTs to “spotlight and not floodlight” when implementing routines, focusing on one change at a time.

This adjustment in routine significantly enhanced the learning atmosphere and underscored the significance of the Do It Now task.

Punctual students were more inclined to complete the task promptly, fostering a culture of timeliness. The classroom became notably tranquil, fostering an environment more conducive to learning or, at the very least, devoid of disruptions.

Those who arrived later (but still on time) were seen checking their watches and asking, “Am I late?”. An observation that highlighted the clear expectations that conversations ceased at the door and work began upon entry. This subtle change minimized the need for reminders to focus on the task, allowing me to concentrate on welcoming other students as they arrived.

While the initiative proved advantageous for my students, it risks detracting from my effectiveness in fulfilling broader school responsibilities, such as facilitating behaviour in corridors. Striking this balance presents a challenge, which I am committed to overcoming as I develop my pedagogical approach.

The Effective Education Fund’s (EEF) seven-step model offers a structured approach to scaffolding and support students in refining their revision techniques. Central to this model are key elements such as activating prior knowledge, independent practice, and modelling. I implemented these strategies to support exam preparation, focusing on their impact on student engagement, performance, and student self-reflection.

The decision to adopt this approach stemmed from the need to provide structured revision sessions, particularly for Year 11:

• Each week, students were challenged to complete timed exercises aimed at replicating exam conditions, with the target of reaching 20 marks in 20 minutes.

• This strategy not only familiarised students with the time constraints of their final exams but also aimed to demonstrate the attainability of target scores (50% for a Grade 7 in Mathematics).

• By gamifying the revision process, students were motivated to actively participate, fostering a culture of enthusiasm towards revision.

• Students were given immediate feedback and subsequent lessons in the week were planned to target key misconceptions and help students further their understanding.

Initial assessments revealed an average score of 12 out of 20, which steadily increased to 16 in subsequent weeks. Moreover, these improvements were reflected in mock exam results, with significant grade advancements. One student progressed from a Grade 3 in December to a high Grade 6 in March and there was a positive trend in results for all but one student.

The incorporation of immediate feedback and self-reflection facilitated a shift in students’ attitudes towards their own learning, with selfreflection becoming a routine practice and students challenging themselves to think about where they would get the marks next time.

Students responded positively to the structured revision sessions, expressing a sense of accomplishment as their scores progressively improved. Students said the use of timers not only simulated exam pressure but also helped them with the resilience needed to perform under such conditions. The immediacy of feedback further enhanced their learning experience, fostering a culture of continuous improvement.

Adapting this approach for a class with a mix of foundation and higher students required careful planning to address individual misconceptions effectively. By tailoring questions to each student’s level, the initial portion of each lesson was dedicated to identifying and addressing specific challenges. While the implementation was facilitated by small class sizes, scalability can be achieved through selfassessment utilising mark schemes. As long as each student is given the same amount of time, to achieve a similar number of marks, any questions from any topic could be used.

In education, the pivotal role of preparing students for assessments is undeniable. As teachers, we are driven by the mission to empower our students with the skills and knowledge needed to excel academically. However, upon delving into the world of examining, I was met with a sobering reality: the average examiner boasts a decade of examining experience alongside over two decades of teaching expertise.

As an Early Career Teacher (ECT) with just under three years of classroom experience, this stark contrast initially left me grappling with self-doubt and apprehension. Despite the daunting odds, and with much encouragement from senior members of my department, I was propelled to embrace the challenge head-on. After all, in a department like Drama, where the commitment to both academic excellence and nearprofessional co-curricular output is omnipresent, what harm could one more commitment do? It’s just another dramatic twist in the plot of my teaching journey. Two years on, I’m glad to say my commitment to examining is still going strong, and I want to share the main take-homes that have shaped my pedagogy within the classroom.

Subject knowledge undoubtedly serves as the bedrock of effective teaching, laying the groundwork for students’ academic growth. However, it’s imperative to recognize that an understanding of the examination framework is equally indispensable for students to achieve the coveted top band marks.

A striking example of this necessity surfaced when seasoned professionals, even actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company, struggled to attain Band 3, akin to a C grade, in the Eduqas A Level exam. This revelation underscores the pivotal role of comprehending the intricacies of exam papers, now deemed fundamental to all Component 3 written assessments. Through meticulous examination of examination requirements, I’ve come to realize the paramount importance of shaping subject knowledge within the context of an exam setting.

An understanding of the examination framework is indispensable for students to achieve the coveted top band marks.

Metacognition, the ability to reflect on and regulate one’s own thinking processes, is a potent tool proven to enhance learning

outcomes. Through my experiences in examining, I’ve come to appreciate the importance of focusing on the learning process rather than solely fixating on the end result. This realization has prompted significant adjustments in my teaching approach. Rather than relying solely on exemplar materials, which students may cling to like security blankets, I now prioritize a deep understanding of the specification. This shift encourages students to engage more deeply with the subject matter rather than simply mimicking past examples.

Rather than relying solely on exemplar materials, which students may cling to like security blankets, I now prioritize a deep understanding of the specification.

Additionally, I’ve implemented ‘blind marking’ workshops aimed at fostering metacognitive skills among students. These workshops prompt students to reflect on their own learning processes as well as others, set personalised goals, and monitor their progress.

As a result, students have become more empowered, gaining a clearer understanding of the characteristics of top-tier work, often exemplified by Band 5 standards.

Confidence, often underestimated yet profoundly impactful, is crucial for teachers, especially ECTs navigating the treacherous waters of the classroom. Admittedly, grappling with imposter syndrome, particularly when venturing into uncharted territory with a new course, has been all too real. However, reflecting on my journey, I’ve noticed a significant shift, especially in my second year of teaching. This transformation owes much to the eyeopening experiences gained from visiting other centres, where I’ve gleaned insights ranging from play selection faux pas to the introduction of other contemporary practitioners into our SOLAs. Armed with newfound confidence, I’ve felt the confidence to steer away from initial plans to tailor exercises to my students’ unique needs. This adaptability has started to become second nature, and I’m pleased to report that that these days the once-omnipresent spectre of imposter syndrome rarely lingers at my studio door.

I’m pleased to report that that these days the onceomnipresent spectre of imposter syndrome rarely lingers at my studio door.

Research indicates that providing effective feedback to students can result in 8 months of additional progress, surpassing the impact of any other intervention. However, incorrect feedback can impede students’ progress. Currently, feedback consumes more of teachers’ time than necessary; studies suggest that ideally we should dedicate twice as much time to planning as to marking.

• Whilst marking work, make notes on common mistakes or misconceptions. Take photos of excellent work to provide peer examples.

• When the students receive their books back discuss the common errors and encourage the students to identify these errors in their own work. When they correct their work, they are fostering self-regulation.

• Talk through the piece of excellent work showing why and how it is excellent. Can students then develop their own work?

• From this could you set a question that addresses the issues raised, covering similar ideas but with a different focus. This allows the student to immediately practice again and improve.

• Ensure students have very clear success criteria, such as an exemplar piece of work for comparison.

• Give prompts to shape meaningful feedback such as: “Have they mentioned social, economic and environmental factors?”

• Once the student has given feedback ask them to reflect on their own work – is theirs more or less successful than the piece they looked at? Why? This combination of peer feedback and self-assessment allows a deeper reflection.

Students colour code their partner’s work against the success criteria scrutinising what is:

• Excellent (Keep it)

• Information that is not relevant to the answer (Bin it)

• Areas that require further development (Build it)

• This nudges students to be more considerate when writing. It can also work well as an individual self-reflective strategy

Teacher review:

• Mark errors in student work simply by placing a dot in the margin near the mistake. The student then needs to locate and correct the error. This encourages self-review and practice.

Bonus method: Modelling metacognition:

• During live modelling in class, verbalise metacognitive strategies. Share your thought processes aloud such as “I am not sure where to go next with this… I am thinking if I maybe try…” This should encourage the students to reflect on their work more frequently reducing the amount of feedback required.

Longfield, J. (2015) Lesson Plan with Misconception/ Bottleneck Focus. Teaching Academy. 27. https:// digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/teachingacademy/27

Millichamp, T. (2024) 8 ways to improve understanding with examples and non-examples, Education in Chemistry, p. 26.

Rosenbrock, M. (2023) Teacher planning – working with student misconceptions in STEM, Teacher Magazine. Available at: https://www.teachermagazine.com/au_en/ articles/teacher-planning-working-with-studentmisconceptions-in-stem (Accessed: 12 March 2024).

Using ‘do nows’ and quizzes to review misconceptions (2020) YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=0x19zPY1mqw (Accessed: 12 March 2024).

Joseph’s blog: https://josephgregoryyu.wixsite.com/meetjoseph/blog

Ashby, R. (2017). ‘Understanding historical evidence: teaching and learning challenges’ in I. Davies (ed.) Debates in History Teaching (2nd Edition). London: Routledge.

Bird, M., K.A. Wilson, D. Egan-Simon, A. Jackson and R. Kirkup. (2020). Touching, feeling, smelling, and sensing history through objects: new opportunities from the ‘material turn’. Teaching History 181: 40-48.

Chatterjee, H.J., L. Hannan and L. Thomson. (2015). An Introduction to Object-Based Learning and Multisensory Engagement. In: H.J. Chatterjee (ed.), Engaging the Senses: Object-Based Learning in Higher Education. Abingdon: Ashgate Publishing. Pp. 1-20.

Conway, R. (2019). Cunning Plan. Teaching History 177: 42-45.

Kouseri, G. (2019). Eliciting Historical Thinking: The Use of Archaeological Remains in Secondary Education. Public Archaeology 18(4): 217-240.

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Novak, M. and S. Schwan. (2021). Does Touching Real Objects Affect Learning? Educational Psychology Review 33: 637-665.

Podesta, E. (2012). Helping Year 7 put some flesh on Roman bones. Teaching History 149: 8-17.

Trapani, B. (2019). Who can tell us the most about the Silk Road? Teaching History 177: 58-67.

Urban, A. (2023). Interactive Artifacts and Stories: Design Considerations for an Object-Based Learning History Game. Tech Know Learn 28: 1803–1813.

SOPHIE MITCHELL

Barton, Craig (2022) Available at: Choose the purpose of your Do Now… and tell your students! -

Tips for teachers

Sherrington, Tom (2024) Available at: 10 things: Common problems with Do Now Activities. – teacherhead)

LUKE MITCHELL

Marzano, Classroom Management That Works

MOLLY PRIDMORE

Reference: Enser Making every geography lesson count (2019)

Charity number: 312747