THE NEXT STEP!

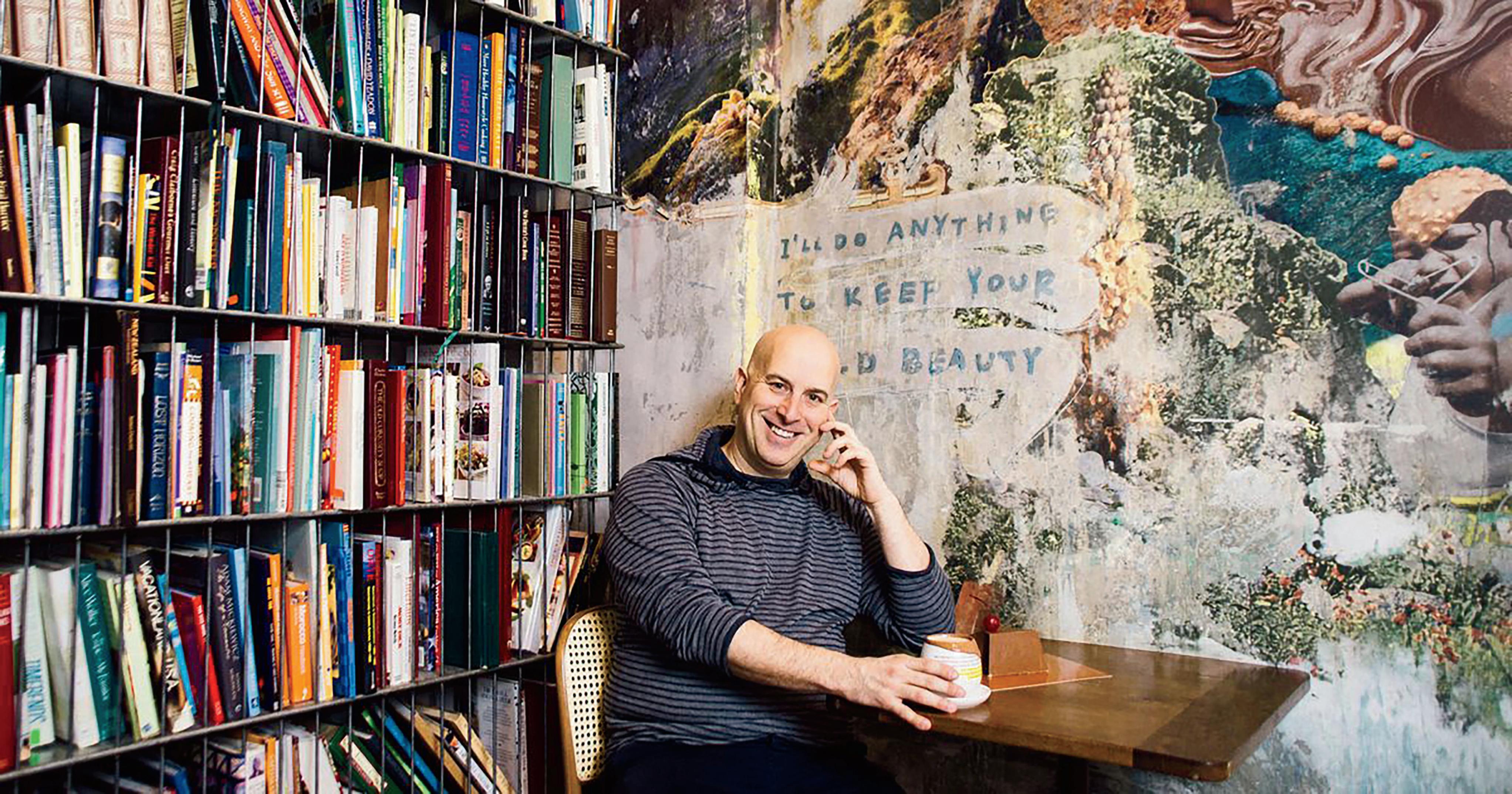

Oded Brenner in front of his new shop, Blue Stripes.

CONTENTS SUMMER 2021

Dogtopia is ready to pamper everyone’s pandemic puppies. PG. 58

QUICK TIPS

6 Start Here This issue is all about the big opportunities ahead. Let’s get started.

8 Six Ways to Get More for Less Limitations can lead to growth. Here’s how six entrepreneurs did it.

10 Build a Great Team The pandemic taught us that strong teams can weather major storms. Here’s how to build them.

12 Reclaim Your Customers Consumers are eager for fresh ways to engage with brands. Take these steps.

14 How to Take Down Goliath The biggest companies can be taken down by the smallest startups. Here’s your game plan.

16 It’s Time for Reinvention Three steps to finding new opportunities and successfully capitalizing on them.

18 Set Your Expectations High This year may still feel uncertain, but your expectations matter more than you know.

FRANCHISE

50 Why This Year Will Be Great for Franchising The industry is uniquely positioned to benefit from a boom.

54 How Many Brands Fit Into One Restaurant? In this case, eight. Here’s a unique way to rethink food service.

58 Preparing for a Big Return How four brands are getting ready for a rush of new business.

64 The 10 Hottest Things in Franchising Our list of this year’s hottest franchise categories, and the brands in each.

80 We Know Less Than We Think The pandemic forced us to reconsider everything. That’s a good thing.

PITCH OUR INVESTORS ON ENTREPRENEURELEVATORPITCH

We welcome founders who have scalable products or services that are ready for investment, and who have a specific plan for how that investment can help them grow. APPLY TO BE ON THE NEXT SEASON ENTM.AG/EEPAPPLY

EDITORIAL

MANAGING EDITOR Monica Im

SPECIAL PROJECTS EDITOR Tracy Stapp Herold

COPY CHIEF Stephanie Makrias

RESEARCH Andre Carter, Eric White INTERN Renna Hidalgo

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Liz Brody, Nate Hopper

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Colin Bryar, Bill Carr, Clint Carter, Chyelle Dvorak, Misty Frost, Richard Koch, Glenn Llopis, Hamza Mudassir, Kim Perell, Stephanie Schomer, Mark Siebert, Melissa Stone

ENTREPRENEUR.COM

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Dan Bova

SOCIAL MEDIA AND CONTENT MANAGER Andrea Hardalo

DIGITAL FEATURES DIRECTOR Frances Dodds

DIGITAL CONTENT DIRECTORS Kenny Herzog, Jessica Thomas

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Matthew McCreary

DIGITAL MEDIA DESIGNER Monica Dipres

DIGITAL PHOTO EDITOR Karis Doerner

NEWS WRITER Justin Chan

EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Chloe Arrojado, Amanda Breen

GREEN ENTREPRENEUR

EDITOR IN CHIEF Jonathan Small

PRODUCT TEAM

AD OPERATIONS DIRECTOR Michael Frazier

AD OPERATIONS COORDINATOR Bree Grenier

CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jake Hudson

VP, PRODUCT Shannon Humphries

ENGINEERS Angel Cool Gongora, Michael Flach

FRONTEND ENGINEERS Lorena Brito, John Himmelman

QUALITY ASSURANCE TECHNICIAN Jesse Lopez

SENIOR DESIGNER Christian Zamorano

GRAPHIC DESIGNER Andrew Chang

unrestricted right to edit and comment.

EDITOR IN CHIEF Jason Feifer

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Paul Scirecalabrisotto PHOTO DIRECTOR Judith Puckett-Rinella

BUSINESS

CEO Ryan Shea

PRESIDENT Bill Shaw

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER Michael Le Du

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER/MARKETING

Lucy Gekchyan

NATIVE CONTENT DIRECTOR

Jason Fell

SENIOR INTEGRATED MARKETING MANAGER

Wendy Narez

MARKETING

SVP, INNOVATION

Deepa Shah

PRODUCT MARKETING MANAGER

Arnab Mitra

SENIOR MARKETING MANAGER

Hilary Kelley

MARKETING COPYWRITER & DESIGNER

Paige Solomon

SENIOR DIGITAL ACCOUNT MANAGER

Jillian Swisher

DIGITAL SALES MANAGER

Jenna Watson

MARKETING ASSOCIATE

Desiree Shah

ENTREPRENEUR PRESS

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Jennifer Dorsey

CUSTOMER SERVICE entrepreneur.com/customerservice

SUBSCRIPTIONS subscribe@entrepreneur.com

REPRINTS

PARS International Corp. (212) 221-9595, EntrepreneurReprints.com

ADVERTISING AND EDITORIAL

Entrepreneur Media Inc. 18061 Fitch, Irvine, CA 92614 (949) 261-2325, fax: (949) 752-1180

ENTREPRENEUR.COM Printed in the USA GST File #r129677027

ENTREPRENEUR MEDIA NATIONAL ADVERTISING SALES OFFICES

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT OF NATIONAL SALES (646) 278-8483 Brian Speranzini

VICE PRESIDENT OF NATIONAL PRINT SALES (646) 278-8484 James Clauss

NORTHEAST ACCOUNT DIRECTOR (516) 508-8837 Stephen Trumpy

ACCOUNT DIRECTOR (845) 642-2553 Krissy Cirello

CHICAGO (312) 897-1002

MIDWEST DIRECTOR, STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS Steven Newman

DETROIT (248) 703-3870

MIDWEST DIRECTOR OF SALES Dave Woodruff

ATLANTA (770) 209-9858

SOUTHERN ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Kelly Hediger

LOS ANGELES (310) 493-4708

WEST COAST ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Mike Lindsay

GREEN ENTREPRENEUR & ENTREPRENEUR, NATIONAL ACCOUNT DIRECTOR Hilary Kelley

FRANCHISE AND BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES

ADVERTISING SALES VP, FRANCHISE Paul Fishback

SENIOR DIRECTOR FRANCHISE SALES Brent Davis

DIRECTOR FRANCHISE SALES Simran Toor (949) 261-2325, fax: (949) 752-1180

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES ADVERTISING Direct Action Media, Tom Emerson (800) 938-4660

ADVERTISING PRODUCTION MANAGER Mona Rifkin

EXECUTIVE STAFF

CHAIRMAN Peter J. Shea

DIRECTOR OF FINANCE Chris Damore

ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE MANAGER Tim Miller

FINANCE SUPPORT Jennifer Herbert, Dianna Mendoza

CORPORATE COUNSEL Ronald L. Young

LEGAL ASSISTANT Cheyenne Young VP, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Charles Muselli

BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATE Sean Strain FACILITY ADMINISTRATOR Rudy Gusyen

Kumon is not your traditional tutoring center. As a franchisee, you’ll guide kids through the many levels of the Kumon Math and Reading Program. Kids stay long-term, even after they catch up, and they often advance to do work that is 2–3 levels above their grade. Plus, most parents enroll all their kids. All this gives you a strong, reliable and exciting business!

THE BIG OPPORTUNITY IS NOW!

The pandemic has been tragic. Dispiriting. Alarming. But for entrepreneurs, it has been something else as well: opportunity. Now more than ever, that opportunity is ready to explode.

That’s what this edition of Startups is all about—looking at the changes entrepreneurs have made throughout this crisis, how they have set themselves up for success, and how you can, too.

How is that possible? There are two ways of looking at what has happened.

The first is adaptability. The pandemic has forced entrepreneurs to make changes they might have never considered, and for many people, that has resulted in innovations, new revenue sources, new ways to serve consumers, and great ideas that last long into the future. The pandemic, in other words, has broken down many entrepreneurs’ barriers—and for the better.

The second is demand. The pandemic has shifted what consumers have needed and wanted, and when they have needed and wanted it. Entrepreneurs could identify new ways to serve people and new habits to accommodate. Later in this issue, for example, you’ll meet the CEO and president of the franchise Dogtopia, who has watched

with interest as people have bought pandemic puppies, pampered them at home, and now seem very inclined to spend money on a higher level of care for their dogs.

As we go forward into an increasingly open world, we will, of course, still be grappling with many unknowns. But we now also have a guide, based on the past year of what has worked well: We can continue to adapt, and we can obsessively understand new demands.

Take it from Michael Joseph, a serial entrepreneur in Boulder, Colo., who launched his takeout-and-delivery business, Scratch Kitchen, in March 2020. What was it like launching during a pandemic? He says it wasn’t much different from launching at any other time—because every entrepreneur will face unexpected challenges and adversity, and the pandemic has just happened to be an extreme example of that. Success comes not from an easy road but, he says, from having a clear vision and a relentless pursuit of it. “It’s just focus, sticking with what you’re going to do, forgetting about the self-doubt—or at least saying goodbye to it—and moving forward,” he says.

We hope this issue of Startups inspires you to do just that. Put the fears aside. Be clear-eyed about the opportunity ahead. And then, like Joseph says, move forward.

JASON FEIFER, editor in

chief

Six Ways

GETTING MORE FOR LESS

Everyone has been forced to cut back in some way— but limitations can lead us to even greater growth. We asked six entrepreneurs: What unexpected benefits have you gotten from change?

1 Excited fans.

“We used to spend thousands of dollars on social media advertising, but we developed a brand ambassador program last year. We enlisted our loyal and enthusiastic customers to help spread the word about our company in exchange for discounts and swag. This cut marketing costs while our customers felt a part of the team.”

—KRYSTAL DUHANEY, CEO, Milky Mama

2 Supplier savings.

“We’ve saved money by providing our suppliers with some certainty. Many suppliers have trouble forecasting demand these days, which created an opportunity for us to play the long game with them. We used our sales projections to order at a higher volume and with longer-term commitments. That helped our suppliers minimize their own volatility, and in turn, they’re lowering our costs—which boosts our margins and ensures that our products are always in stock.”

—MARK MCTAVISH, cofounder and CEO, Pulp Culture

3 Client connections.

“I’m used to wining and dining clients to keep up the connection and positive energy, so not having those touch points made me nervous. I started sending care packages that went over really well—and are cheaper than a fancy steakhouse or bar! I curate for their tastes. For example, I’ve sent everything from face masks for clients that need to travel to some of my favorite California gourmet snacks as a holiday gift. One of the best items was branded socks, because everyone had been at home.”

—GREGG DELMAN, founder, G Three Media

4 Focused sales.

“Before COVID, I never offered appointments at my wig salon. Now I see clients by appointment only; it has increased my conversion rate and lowered my costs. Why? Before, I needed an assistant to handle multiple walk-ins, not all of whom were serious buyers. Now that cost is gone. Women who make appointments are much more likely to buy. Wig shopping is highly personal and often sensitive. It’s much more pleasant to do it in private.”

—LENA FLEMINGER, owner, Lena’s Wigs

5 Flexible working.

“I no longer assume every meeting is best done, by default, in person. Sure, I miss seeing colleagues in person, but we’re all realizing that virtual work unlocks efficiencies and flexibility. In the future, my team will be much more intentional about face-to-face meetings—requiring it only when it makes a significant difference; for instance, to kick off a new initiative or build chemistry in a team.”

—SCOTT BELSKY, cofounder, Behance, and chief product officer, Adobe

6 Maximized downtime.

“When the pandemic hit, we shut down our properties and furloughed nearly our entire hotel-level team, and the corporate team took salary reductions. We used the downtime to integrate more technology solutions for our guests and team—and once we reopened, those solutions boosted guest satisfaction scores, increased efficiency, and improved our bottom line. Our B2B business also jumped: We offer management solutions for independent hotels, and because we kept our team intact, 12 new clients have come to us.”

—ROB BLOOD, founder and president, Lark Hotels

CHANGED FOR THE BETTER

The past year created many changes in the way people build and run businesses—and some of those changes may be permanent. Here are three we’re happy to keep. by MISTY FROST

s we move through 2021, there’s a palpable desire to get “back to normal” as quickly as possible. But in the business world, getting back to normal would be a big mistake.

ANo doubt, last year was tough and tragic. Yet there have undeniably been significant and positive changes in the way we work, learn, and grow as business leaders. So now, as we inch back to whatever “normal” means, it’s important that we cling tight to these three valuable lessons learned from 2020.

1 Embrace flexible schedules.

I’ve toiled at organizations that attempted to encourage at-home offices. One manager’s opinion can impact the entire team and create different policy interpretations across departments, causing frustration among staffers. But now we’re all old pros at working from home!

Since employees showed they could stay productive, more businesses started setting long-term flexibleschedule policies. To succeed, they’ll have to set clear expectations—and understand their teams’ needs.

John Knotwell, the general manager of performancemanagement platform company Bridge, learned this

himself recently. “I had a one-on-one meeting with an employee who shared that working from home with a toddler—whose daycare was closed—was difficult as they tried to manage a typical nine-to-five schedule,” he told me. “I realized that flexible schedules make sense for some roles, and allowing them has led to a more engaged, productive team.”

2 Revamp educational qualifications for hiring.

In 2020, many recognized the value of online learning for the first time. In 2021, organizations that previously prioritized four-year degrees from brick-and-mortar universities may understand that there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution to learning. Trade schools or online training programs can create employees who are as valuable as those with a four-year degree. Some astute employers even offer subsidized or free tuition to employees, a key in recruiting and retaining talent.

Here’s one good example: Grace Health, a medical provider in Michigan, partnered with a healthcare training company to offer at-work learning. (Full disclosure: I’m affiliated with the training company.) When Grace Health announced this, it focused on how it could now provide “debtfree formal education and on-the-job training for staff who want to become medical assistants but have no experience or training.” In other words, it lowered the barrier to entry for those who might have otherwise been left out.

Online learning and professional development also provide viable options

for lifelong learning, and this year has helped more employers recognize the value of different educational paths. This not only broadens the talent pipeline but also can help foster a more inclusive workforce.

3 Commit to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

If 2020 was a year of committing to creating diversity, equity, and inclusion programs for many organizations, 2021 will be the year when statements and expressions of support must translate to meaningful action and change.

Entrepreneurs are realizing that this means using their voice, even if it’s in hot public debates. A small example: Randy Pitchford, founder of video game developer Gearbox Entertainment Company, wrote an open letter to Texas governor Greg Abbott to oppose what he viewed as discriminatory new laws. “Today’s workforce—especially millennials, and especially those working in high-tech industries— overwhelmingly support nondiscrimination protections and seek to live in states that reflect the diversity and inclusion they value,” he wrote.

Employees respond well to this—as evidenced by a recent Glassdoor study, where 76 percent of workers said a company’s diverse workforce is an important factor when they’re deciding who to work for.

In 2021 and beyond, changes like these will only grow—and we’re better for it.

Misty Frost is CEO of healthcare training company Carrus.

RECLAIM YOUR CUSTOMERS

After a year of isolation, consumers are eager for fresh ways to engage with brands. Take these steps to boost your marketing efforts and reignite their trust and love. by

MELISSA STONE

Now is not the time to overlook the power of digital marketing. It’s been a turbulent year for business owners and consumers alike, and to reengage your fans, a personalized approach is key. Gone are the days when marketers could get away with sending a mass “We miss you!” email to inactive subscribers, hoping to lure them back with discount codes. Instead, savvy companies should explore new technologies, target their audience with intention, and rely on analytics to learn more about their audience. Follow these three tips to recapture shoppers’ affection (and dollars).

1 Invest in new technology.

To expedite innovation within your own business, invest in forward-thinking technologies offered by young startups. Earmark 10 percent of your marketing spend as a “test and learn” campaign budget. Once you get the results back, consider reallocating more.

For example, back in 2010, loyalty programs were relatively new. At the time, I was leading digital marketing at Giorgio Armani Beauty, part of L’Oréal. In partnership with 500friends, a customer relationship management tool, we piloted L’Oréal’s first loyalty program within its Luxe division. One key learning? Consumers don’t want to be rewarded for shopping with you just through loyalty points.

Today’s shoppers crave more meaningful engagement; 80 percent want personalization from retailers, and about 31 percent are more loyal to brands that can

deliver that personalization. By testing new technology, we gained valuable insights moving forward.

Think about the gaps in your business (augmented reality, CRM, digital media, etc.) and set up virtual meetings to learn how boundarypushing small businesses might help increase your bottom line. Ask for case studies and analyze how their tools complement your existing technology infrastructure.

2 Experiment with paid social media formats and segmentation.

Shopping on social media is expected to grow 34.8 percent in 2021. While many brands paused their media budgets during the pandemic, of those that did keep their ad units live, women continued to be key influencers (previously purchasing from social and expressing interest in it). Take advantage of various segmentation opportunities to target consumers by gender, age, and interests across

Facebook and Instagram.

You might segment ads to, say, moms of 18-year-old daughters with a select household income living in a select zip code who previously browsed the website. Once you confirm the segmentation (who will see the ads), experiment with the creative (what type of visuals and messaging resonate best) and optimize based on consumer engagement (who clicks which ad unit and when).

One key lesson is determining how best to match the messaging with the target audience. (Copy will look different for, say, teens or moms.) And be sure to experiment with ad formats. Facebook offers augmented reality advertising, Instagram is adding try-on features, and Snapchat recently introduced Local Lenses. These are great testand-learn opportunities to provide interactive experiences from the safety of consumers’ homes—and also to see what resonates with your customer base.

3 Leverage predictive analytics. Once you have your ad campaign set up and results start trickling in, consider predictive analytics. Companies in this field can help forecast who your most inactive customers will be so you can set up campaigns before your customers start shopping with another brand.

For instance, explore which of your customer segments are “lost” (about to stop purchasing) and which are “at-risk” (might shop less with you over the next few months). Data can show you which group might be more price-sensitive, which helps you deliver relevant messages and increase sales.

While the marketing landscape continues to evolve, following these three tips will increase your brand’s revenue and reengage isolated consumers who are once again eager to find trusting relationships with the businesses they love.

Melissa Stone is the founder of Melissa Stone Consulting.

About

Enjoy the perks of owning your own successful business while also making a difference through partnerships, community, education, experience, and only the highest quality products. Our franchise and affiliate model is the easiest entry into the hemp extract industry. We have a proven track record of success with an established network of owners and marketing professionals who support your growth.

Your CBD Store® Fast Facts

Join the Largest Network of Hemp Extract Retail Owners Worldwide

Your CBD Store® began with one woman, one story, and one store. Today, we have countless success stories and over 500 stores nationwide. We believe in providing the most transparent and dependable CBD products that utilize natural plant synergies. That is why we have rigorous standards for quality and consistency and harvest only the highest-quality hemp products, grown in the U.S. We are dedicated to our community; earnestly providing contributions to our local and national partnerships. Our deeply committed focus on customer needs helps us provide an environment where our customers can feel safe enough to show or discuss their concerns in order to obtain relief and ultimately share their personal stories. To that end, our mission remains at the core of everything we do: to empower and help our customers regain a quality of

life so that they too, can illuminate.

At every Your CBD Store, customers enter a comfortable, safe, and inviting environment to learn about hemp-derived products and try samples. With a collection of award-winning products, customers can feel confident making an informed decision on the best cannabinoid formulation for them. Backed by SunMed™’s extensive research, third-party laboratory reports, and customer-driven product development, Your CBD Store continues to offer the most sophisticated hemp-derived products on the market.

Your CBD Store franchisees and affiliates have access to a staff of expert leaders in all areas of business, science, and marketing support. With over 500 stores, franchisees and affiliates can expect a protected territory around their store. To take our support an additional step further,

you can participate in our internal social media platform to engage with and learn from other store owners and their successful strategies and practices.

Owners First is Your CBD Store motto! We invest all our time, energy and resources in supporting you.

HOW TO TAKE DOWN GOLIATH

The biggest companies can still be taken down by the smallest startups. Here are four strategies disruptors use to fight their way up. by HAMZA

MUDASSIR

You think it’s hard getting to the top? Try staying there.

The accelerated churn rate of the S&P 500 indicates that at least half of today’s top U.S. companies will get replaced by new ones over the next decade. That is a mind-boggling market value of $16.8 trillion up for grabs. And the craziest part is who replaces the old market leaders: It’s often companies that, just a few years before, were considered scrappy little startups.

So how does a new company rise to slay a giant? It doesn’t happen by accident. It’s as if the two are playing a game of chess—except the incumbent has been playing the game for years, and the startup is entering halfway through. The startup is at a severe disadvantage. Normal strategies won’t work. It must play by a completely different set of rules.

In my many years of working with successful disruptors, as well as researching the same at Cambridge University’s Judge Business School, I’ve seen a lot of companies lose this game—as well as a lucky few win it. Here are the four moves that I’ve seen have the highest chance of success against Goliaths.

1 Change the basis of competition.

For startups, the rules of the game are rigged. The incumbent has set the terms, and its scale, experience, and tech-

nology are nearly impossible to beat.

Consider every brick-andmortar retailer that went up against Walmart in the 2000s. Walmart’s basis of competition was its ability to sell consumer goods at the lowest possible prices, and it accomplished that profitably because of its remarkable hub-and-spoke distribution model and its large, centralized procurement budgets. Other retailers could not catch up…until Amazon.

Yes, Amazon pursued an e-commerce model before Walmart was focused on digital. But it’s also important to remember what Amazon founder Jeff Bezos didn’t do. He didn’t try to build a better hub-and-spoke model or claim to sell goods at the lowest possible prices. Instead, he chose to compete with Walmart through remarkable customer service and a next-day, deliver-

anywhere model—both of which Walmart could not follow through with in time.

To beat something as big as Walmart, startups need to set their own rules—to build something the incumbent doesn’t have, then make that the thing they’re judged by.

2 Exploit taboos. Every industry comes with its own taboos. These are known as the way things are done, and incumbents consider them to have an almost religious importance. But for the average startup, these taboos are nonsensical. Even better, they are a competitor’s blind spot—and indicate where large incumbents will never look to innovate! Consider traditional banks’ taboos. These institutions long considered their slow, bureaucratic processes to be a source of competitive advantage and, ironically, pride. After all, you could never be too careful when a customer’s money is exchanging hands.

Revolut, an upstart digital bank in the U.K., felt otherwise. By developing a secure technology stack that rapidly did checks and balances with minimal error, the bank’s founders publicly shunned the idea that slow banking was good banking. The implications of this change in mindset have been significant. Revolut has grown to more than 15 million subscribers in five years of launch, achieved a market cap of $5.5 billion, and pushed Europe toward open banking. Meanwhile, traditional banks are struggling thanks to collapsing fees, unhappy

customers, and incomplete digital transformations. If a large bank is toppled by a startup like Revolut, it can blame its taboos. The way things are done was not, it turns out, the way things ought to be done.

3 Optimize for power. When an army invades a new land, it doesn’t sweep in all at once. Instead, it targets places where it can gain power over key resources.

Business conquests are similar. This is what my Cambridge colleague (and former strategy professor!) Kamal Munir identified in his research. He found that successful disruptors deliberately create a series of dependencies, where suppliers, customers, and even competitors end up relying on the disruptor.

For example, as Tesla set out to become a major player in the automobile market, it did more than build electric cars. It also developed a countrywide network of electric charging stations. Now Tesla’s competitors are in a bind: They have to either make their cars compatible with Tesla’s stations or limit their market potential. This will give Tesla an advantage for years to come.

Munir thinks of this as a power move—and it comes at the cost of short-term profits. Tesla founder Elon Musk could have saved much-needed cash and let someone else develop a charging network. But with the support of patient investors, his power move enabled him to set new standards of customer expe-

To beat something as big as Walmart, startups need to set their own rules—to build something the incumbent doesn’t have, then make thatthe thing they’re judged by. the

rience, strike symbiotic partnerships, and change the industry cost and pricing structure. This worldview of disruptive strategy, while deceptively simple, is incredibly powerful and can explain the slew of successes of loss-making disruptors such as Uber, Airbnb, WhatsApp, and others.

4 Simplify—a lot.

Here’s an important truth: Disruption is powered by simplification. Mature companies are complicated. They have a glut of purchase options and upgrades that most customers don’t need and many find too confusing. That’s why a disruptor can use simplification as an opening gambit—doing away with all those options, and offering something simple that solves most customers’ problems. Even more important, this simplification allows the disruptor to run a leaner organization that can therefore lower its prices.

Of course, a startup won’t remain simple forever. Its first customers will be people who are price-sensitive and therefore easily lured away from a competitor. Then

the startup is adopted by mainstream and high-end customers, who no longer see the incumbent’s complex offerings as having additional value. Low-cost airlines are a good example here. Why pay more for mediocre meals, excess baggage, and in-flight movies if you just need to get from point A to point B? Minus the recent economic shock of COVID-19, the most profitable airlines in the world continue to include low-cost, simplified players such as EasyJet, Southwest, and Ryanair. Taking down Goliath is by no means easy. But it is happening more frequently and at a larger scale today than ever before. While these strategies are powerful individually, astute disruptors tend to daisy-chain them together in an unstoppable sequence, over multiple years. So if you’re small today, take heart. With the right plan, even your biggest competitors may be in your reach.

Hamza Mudassir is a visiting fellow in strategy at the University of Cambridge and founder of Platypodes.io.

THE TIME FOR REINVENTION IS NOW

Our world has changed. As people—and as entrepreneurs—we should change, too. Follow these three steps to find new opportunities and capture them with success. by GLENN LLOPIS

We are living in a moment of abundant opportunity.

That might sound unrealistic, or at least untimely, given what the pandemic has put our world through. But the past 15 months have revealed new opportunities in the ways we learn, work, and live. Entrepreneurship is no longer just a business term. It’s a way of life. We have all been forced to reflect on what really matters to us as individuals, as leaders, and as entrepreneurs. Instead of seeing each of these three distinct areas as disconnected parts, now is the time to create one healthier whole. As you set out to reinvent and reinvigorate your life as an entrepreneur, don’t back away from opportunities simply because you can’t predict the final outcome. When you hesitate, it’s harder to gain buy-in from others. Instead, seize those opportunities, and trust your gut and spirit. Need a nudge? Follow these three guiding principles.

1 Broaden your observations.

Don’t see just the opportunities that are right in front of you—look for those that are less obvious. This is why it’s so important to know and trust yourself. It’s easy for someone else’s opinion to misguide your thinking, but when you know what you aim to achieve, it gives you the focus and patience to explore for more.

In the process of seeing the opportunity you were originally hoping for, you may discover others that provide more clarity around your original intentions. For example, when I wrote my first book, it was initially planned to be about my father’s wisdom. When I shared it with a friend who knew someone in the publishing industry, their feedback helped turn it into something more significant, framing my father’s wisdom as lessons on thinking like an entrepreneur and finding innovation in your work. Now, 12 years later, I am a senior adviser to Fortune 500s and entrepreneurs the world over.

2 Adopt a farmer’s mentality.

The wise farmer once said, “You’ll never know which seed is going to grow without planting it first.” The wise entrepreneur knows this lesson well. What’s the point? Keep planting seeds and allow your broadened observations to guide you.

Many in the business world might think this mentality is about creating multiple streams of income (much like the farmer would harvest dif-

ferent types of crops), but the key is to water each seed you plant with focus and intention to not only multiply your opportunities but discover new ways that those opportunities can support one another.

3 Build momentum.

How often have you heard this: “That’s a great idea; you should do something with it.” And then…nothing happens. That’s because creating momentum is critical but also very difficult. Why? Because most people embark on opportunities without knowing their inventory and access to resources. I don’t just mean money—I mean valuable relationships.

Momentum is built through relationships that are willing to test-drive your ideas. These relationships must be earned over time. If you were to ask five people to support the opportunity you are trying to grow, can you say that you have supported them consistently in the past? Have you earned the right to ask people for their support?

Building momentum can come in many forms. But your ability to have cultivated and earned strong relationships is vital to your ability to seize opportunities. Opportunities come and go, but it is your responsibility to share them with others along the way. It will help you be prepared and ready to take action when the moment calls.

Glenn Llopis is the author of three books; most recently, Leadership in the Age of Personalization.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

The year 2021 may feel uncertain, but set your expectations high anyway. Doing so will become your guiding force. by

RICHARD KOCH

Eighteen classes of schoolchildren were tested for their IQs. The results weren’t shown to students or parents. Instead, their teachers were simply given a list of which ones scored highest, along with these instructions: Do not treat these students differently than the others.

What happened next may have taken place in a classroom, but it can light a path for our own adult careers. Here were the results, originally produced in this study in 1965 but repeated many times over: After eight months, all the students were given another IQ test. Among the children not identified as unusually gifted before, there were no notable changes. But among the students who had scored highly before, four-fifths scored at least 10 IQ points higher the second time. A fifth gained 30 points.

How? Even after being told not to treat these children differently, their teachers had set their expectations high. The teachers unconsciously communicated something to the children about their abilities, and they rose as a result.

I’ve studied how entrepreneurs have reached great success, and I’ve found this to be a constant trait. The expectations we have—of others and ourselves— become self-fulfilling. This is perhaps the greatest and most important magic trick in the world, and I find that the most accomplished

people’s expectations can be broken down into five components:

1 Expectations are set much higher than is normal.

2 The entrepreneur isn’t concerned by details but rather with changing the big picture.

3 The entrepreneur is unreasonably demanding of themselves and others.

4 There’s a progressive escalation of expectations over time.

5 The expectations are unique to the individual and can be succinctly expressed.

That last one is especially critical. It means that a leader’s expectations are tied to a specific, understandable mission that only they (and their team!) can accomplish. Look back through history and you can see how great minds worked toward crisp goals. Leonardo da Vinci’s goal: Make “perfect paintings.” Winston Churchill’s goal: Stop Hitler. Jeff Bezos’: Build “Earth’s most customercentric company.”

You may worry that Olympian-size expectations can be a turnoff or drive

others away. They do not, if they’re matched by Olympian achievement.

I experienced that firsthand. I once worked at Boston Consulting Group, one of the largest consultancies in the world, where founder Bruce Henderson was massively demanding. I never heard him praise anyone or anything. He was always driving us to the next big insight. Once, after a business conference we hosted for European leaders, he ripped into us. “I was saying all this three years ago,” he said, as if an ice age had since intervened. “Haven’t you learned anything new since then?” You might imagine that this was de-motivating, but it instead pushed us to work at the boundaries of knowledge. Corporate America listened to us. We felt on the verge of a new discovery every day. So often in life, people see what they expect to see, and that compounds

the expectation, making it real. Look around and ask yourself: What expectations am I setting? Other people’s positive expectations of you will improve your own performance. And unless we have a reputation for bragging—and therefore devaluing our expectations—then the people we work with will be strongly influenced by our expectations. A cycle will begin. Small performance leads will compound over time, growing as our expectations grow.

This is why I tell entrepreneurs to set expectations as high as they can, so long as they truly believe those expectations can be realized. If you want unreasonable success, you must have unreasonable expectations. The ceiling on your future is the most you can imagine and expect.

Excerpted from Unreasonable Success and How to Achieve It (now available in the U.S. from Entrepreneur Press).

MAKING BIG CHANGES IN TIMES OF BIG CHANGE

(OR WHY AMAZON CREATED THE KINDLE )

Entrepreneurs are defined by how they adapt during crises. In this exclusive excerpt from their book WorkingBackwards, longtime Amazon execs Colin Bryar and Bill Carr reveal how the company dealt with massive disruption…and transformed itself as a result.

ADAPTING

Steve Jobs invited Jeff Bezos over for sushi. It was the fall of 2003, which were consequential days for both Apple and Amazon. Only two years earlier, Apple released its first iPod and Amazon turned a quarterly profit for the first time. Now Steve was inviting Jeff, me (Colin), and another Amazon colleague down to Cupertino for a chat.

We arrived and were ushered into a nondescript conference room with a Windows PC and two platters of takeout sushi. Everyone chatted about the state of the music industry while doing some serious damage to the food. After dabbing his mouth with a napkin, Jobs segued into the real purpose of the meeting: He said that Apple had just finished building its first Windows application. He calmly and confidently told us that even though it was Apple’s first attempt to build a Windows application, he thought it was the best Windows application anyone had ever built. He then personally gave us a demo of the soon-to-be-launched iTunes for Windows.

During the demo, Jobs talked about how this move would transform the music industry. Up until this point, if you wanted to buy digital music from Apple, you needed a Mac, which made up less than 10 percent of the home computer market. Apple’s first foray into building software on the competing Windows platform showed how serious it was about the digital music market. Now anyone with a computer would be able to purchase digital music from Apple.

Steve said that CDs—which Amazon sold many of—would go the way of other outdated music formats like the cassette tape. His next comment could be construed as either a matter-of-fact

statement, an attempt to elicit an angry retort, or an attempt to goad Jeff into making a bad business decision by acting impulsively. He said, “Amazon has a decent chance of being the last place to buy CDs. The business will be high-margin but small. You’ll be able to charge a premium for CDs, since they’ll be hard to find.” Jeff did not take the bait. We were their guests, and the rest of the meeting was uneventful. But we all knew that being the exclusive seller of antique CDs did not sound like an appealing business model for Amazon.

Remember, this was 2003. The shift to digital had just begun. No one wanted to get in too early with a product that did not yet have a market. But no one wanted to miss the moment, either, and be unable to catch up. We knew that we’d need to invent our way out of this dilemma by obsessing over what the best customer experience would be in this new paradigm.

Did that meeting with Steve Jobs impact Jeff’s thinking? Only Jeff can speak to that. All we can say is what Jeff did and did not do afterward. What he didn’t do (and what many companies would have done) was to kick off an all-handson-deck project to combat this competitive threat, issue a press release claiming how this new service

would win the day, and race to build a copycat digital music service. What he did do was take his time, process what he learned, and form a plan that revolutionized the company—and did the exact opposite of chasing Apple into the music-selling business.

This is the story of the creation of the Kindle.

We were there to help it happen: Colin started at Amazon in 1998, Bill joined in 1999, and we spent decades as senior executives working with Jeff. In developing the Kindle, we learned a critical lesson in business longevity—and in what it takes to define the change around you.

A FEW MONTHS after that meeting with Steve Jobs, in January 2004, Jeff made his first move. He put Steve Kessel, Amazon’s VP of media retail, in charge of the company’s digital business. This seemed strange at first. Steve Kessel had been overseeing sales of physical books, music, video, and more—a core component of Amazon’s business. The company’s digital media business, meanwhile, consisted of a new “search inside the book” feature, plus an e-books team of roughly five people, which generated a few million dollars in annual revenue and had no real prospects for growth.

But there was wisdom here. Jeff wasn’t making a

“what” decision; he made a “who” and “how” decision. This is an incredibly important difference. He did not jump straight to focusing on what product to build, which seems like the straightest line from A to B. Instead, the choices Jeff made suggested— even then!—that he believed the scale of the opportunity was large and that the scope of the work required to achieve success was equally large and complex. He focused first on how to organize the team and who was the right leader to achieve the right result.

Steve asked me (Bill) to join him in this new division, leading the digital media business team. I was hesitant. But then Steve explained Jeff’s thinking: Amazon was at an important crossroads, and now was the time to act.

Though the physical media business was growing, we all understood that over time it would decline in popularity and importance as the media business shifted to digital. In the beginning of that year, 2004, Apple announced that it had sold a total of more than two million iPods—and the proliferation of shared digital music files online had already prompted a decline in sales of music CDs. It seemed only a matter of time before sales of physical books and DVDs would decline as well, replaced by digital downloads.

Jeff was a student of history and regularly reminded us that if a company didn’t or couldn’t change and adapt to meet shifting consumer needs, it was doomed. “You don’t want to become Kodak,” he would say, referring to the oncemighty photography giant that had missed the turn from film to digital. We weren’t going to

ADAPTING

sit back and wait for that to happen to Amazon.

Conceptually, I understood and accepted this history lesson. What I didn’t get was why Steve and I had to change jobs and build up a whole new organization. Why couldn’t we manage digital media as part of what we were already doing? After all, we would be working with the same partners and suppliers. The media had to come from somewhere, and that somewhere was media companies: book publishers, record companies, and motion picture studios. I already managed the co-op marketing relationships with those companies, so it made sense that we should do this within the same organization and build off the knowledge and success of our strong team. Otherwise, Amazon would have two different groups in the company responsible for business relationships with partners and suppliers.

But Jeff felt that if we tried to manage digital media as a part of the physical media business, it would never be a priority. The bigger business carried the company, after all, and would always get the most attention. Steve told me that getting digital right was highly important to Jeff, and he wanted Steve to focus on nothing else. Steve wanted me to join him and help him create the new business.

A separate digital media organization would prove to be the right thing for the company, and one of the best things ever to happen for my career. I said yes.

NOW WE HAD a mission—to build a business selling dig-

ital books, music, and video. But how? We spent roughly six months researching the digital media landscape and learned some key things. First, music: With piracy rapidly killing the CD business and Apple selling millions of songs on iTunes to millions of iPod customers, the record companies were eager for us to jump in fast so they would have more retailers to deal with—not just Apple. Second, e-books: A marketplace existed already, but it was small, publishers weren’t investing in it, and they only released a small catalog of e-books at the same high prices as hardcovers. And finally, digital movies and TV: Content creators were riskaverse, and they weren’t interested in licensing shows or movies to digital service providers like Amazon.

The music business really seemed to be calling. In December 2004, Jeff, Steve, and I attended Music 2.0, a digital music industry conference at the Hilton hotel in Universal City. We listened to a number of speakers, one of whom was Larry Kenswil, a senior executive at Universal Music, who spoke about the current state of the digital music business, which at that time was divided into two camps. In one camp were services like Napster that facilitated free file sharing. By itself in the other camp was Apple, selling songs to load onto the iPod for 99 cents each. Larry was eager for more big tech companies to enter the business, as that would mean more revenue for Universal Music. He obviously knew that we were in the audience, because he made a few comments pointed directly at Jeff, effectively dissing Amazon for not being in the digital

music space and prodding us to jump in fast.

One of the decisions we had to make in that first year was whether to build a business or to buy a company already operating in that space. We had many meetings with Jeff where Steve and I would present our ideas for our music product or a company we might acquire. Each time we had these meetings, Jeff would reject what he saw as copycat thinking, emphasizing again and again that it had to offer a truly unique value proposition for the customer. He would frequently describe the two fundamental approaches that each company must choose between when developing new products and services. We could be a fast follower—i.e., make a close copy of successful products that other companies had built—or we could invent a new product on behalf of our customers. He said that either approach was valid but that he wanted Amazon to be a company that invents. In other words, as he also emphasized, people like the exec who’d baited him at the digital music conference wouldn’t drive our process. He didn’t want to simply build copycat versions of products like the iPod and the iTunes store, nor did he care about making a PR splash by announcing to the public that Amazon had arrived in the digital business. He chose the path of invention because true invention leads to greater long-term value for customers and shareholders.

My team and I quickly learned that invention is a more challenging path than fast following. The road map for fast following is relatively clear—you simply study what

your competitor has built and make a copy. But there’s no road map for invention. It requires you to bushwhack and forge into uncharted terrain, scout out a variety of possible product ideas, and build the roads yourself.

Jeff zeroed in on the fundamental difference between the digital media retail business and our existing physical media retail business. Our competitive advantage in physical media was based on having the broadest selection of items available on a single website. But this could not be a competitive advantage in digital media, where the barrier to entry was pretty low. Any company, whether a well-funded startup or an established enterprise, could match our offering. In those days, while it took time and it wasn’t easy, any company could build an e-book store or a 99-cent music download store, where they offered the same breadth and depth of books and songs as every other digital download store. We couldn’t meet Jeff’s requirement that our digital business have a distinct and differentiated offering just on selection and aggregation.

The digital world also undercut another one of our advantages. Compared to other retailers, we’d been able to offer consistently low prices in part because of our lower cost structure. (Which is to say, we had no stores.) But that wasn’t a factor in digital. The process and costs associated with hosting and serving digital files were basically the same whether you were Amazon, Google, Apple, or a startup. There was no known fundamental difference that would allow one company to

ADAPTING

gain a competitive advantage and win over the long term by having lower digital media operating costs and passing those savings on to the consumer in the form of lower digital media prices.

Early on, Jeff drew a version of this picture ( fig.1 ) on the whiteboard to make his point clear.

He explained that there was an important difference in the digital media value chain, as well. In physical retail, Amazon operated at the middle of the value chain. We added value by sourcing and aggregating a vast selection of goods, tens of millions of them, on a single website and delivering them quickly and cheaply to customers.

To win in digital, because

those physical retail valueadds were not advantages, we needed to identify other parts of the value chain where we could differentiate and serve customers well. He told Steve that this meant moving out of the middle and venturing out to either end of the value chain. On one end was content, where the value creators were book authors, filmmakers, TV producers, publishers, record companies, and movie studios. On the other end

were distribution and consumption of content. For us that meant focusing on applications and devices that consumers used to read, watch, or listen to content, just as Apple had already done with iTunes and the iPod.

This all made sense. But there was a problem: Our core competencies did not extend to either end of the value chain.

Steve did not let this get in the way. In one of our

meetings, he said that a typical company that wanted to grow would take stock of its existing capabilities and ask, “What can we do next with our skill set?” He emphasized that Amazon’s approach was always to start from the customer and work backwards. We would figure out what the customers’ needs were and then ask ourselves, “Do we have the skills necessary to build something that meets those needs? If not, how can we build or acquire them?”

That’s what led us to our big idea.

SO THERE WE WERE: stuck in the middle, with Amazon’s historic advantages suddenly looking like disadvantages. We had to do more than just

FIG. 1

Authors, Musicians, Filmmakers

serve things that others could serve, too. And although we had started this journey because of digital music, Jeff ultimately decided that there was a bigger opportunity elsewhere. It was e-books.

There were multiple reasons for this. Music may have been the first category to move to digital in the marketplace, but Apple had a big head start, and we hadn’t conceived of a music device or a service idea that was compelling enough to make a big investment in. Video had not gone digital yet, which seemed like an opportunity, but the barriers were just too high. Getting the rights from studios would be difficult, and most consumers didn’t have internet fast enough to

stream massive video files.

But e-books were a different story. Books were still the single largest category at Amazon and the one most associated with the company. Also, the e-book business as a whole was tiny; there was no good way to read books on a device other than a PC (and reading on a PC was definitely not a good experience). Based on the success of iTunes/iPod for music, we believed that customers would want the e-book equivalent: an app paired with a mobile device that offered consumers any book ever written, available at a low price, that they could buy, download, and start reading in seconds.

When we worked backwards from the customers’

needs with digital books, it became apparent that we needed to invent a device ourselves, even though it might take years, and even though we had no experience in hardware. As Jeff would say, “What could possibly be more important than reinventing the book itself?”

I’ll be honest: At the beginning, this didn’t make sense to me. “We’re an e-commerce company, not a hardware company!” I would insist. I thought we should partner with third-party equipment companies that were good at designing and building hardware and stick to what we knew: e-commerce.

I kept telling Steve that he knew nothing about hardware—he wasn’t a gadget guy,

and his ancient Volvo didn’t even have a car stereo!

But Steve countered well. He reminded me that we’d developed and stress-tested many ideas, and it was clear that, to deliver a book buying and reading experience that would delight customers, we needed to build an e-book store and a reader that was deeply integrated with a reading device. Through our research, we knew that relying on third parties, while operationally and financially less risky, was much riskier from the point of view of customer experience. If we start with the customer and work backwards, then the most logical conclusion is that we need to create our own devices.

The second point he made

was that, like any company at a crossroads, if you decide that the long-term success and survival of the company is predicated on having a specific capability you do not have today, then the company must have a plan to build or buy it. If we wanted to ensure a great customer experience that was differentiated on the far end of the value chain, we couldn’t outsource the project. We had to do it ourselves. So we got going, knowing it wouldn’t be easy but that the potential rewards were great.

In September 2004, Steve hired Gregg Zehr, a Silicon Valley veteran who had been a VP of hardware engineering at Palm Computing and Apple. He set up a separate office in Silicon Valley, not Seattle, in

order to tap into the Silicon Valley technical talent pool.

In parallel, two experienced and trusted Amazon engineering VPs established and hired software engineering teams in Seattle to build the cloud or back-end systems.

In April 2005, we acquired Mobipocket, a small company based in France that had built a software application for viewing and reading books on PCs and mobile devices.

At some point, early in the process, a name for the device emerged: Kindle.

By the middle of 2005, it became clear that this project was taking much longer and consuming more funds than we had anticipated. During one finance team review, there was a heated discussion

about the surprising ramp-up in expenses. At some point in the debate, someone asked Jeff point-blank, “How much more money are you willing to invest in Kindle?”

As I remember the scene, Jeff calmly turned to our CFO, Tom Szkutak, smiled, shrugged his shoulders, and asked the rhetorical question “How much money do we have?”

That was his way of signaling the strategic importance of Kindle and assuring the team that he was not putting the company at risk with the size of the investment. In Jeff’s view, it was way too early to give up on the project.

We all know what happened next. The Kindle debuted to the world in

2007, four years after that sushi meeting with Steve Jobs. It sold out in less than six hours. Amazon was never the same.

From Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets from Inside Amazon, by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr. Copyright © 2021 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

911 Restoration has seen astounding growth over the past few years, and much of that success is due to a strong support system for franchisees. Founder Idan Shpizear knows what it takes to build a small operation into a thriving business. After all, he built one of the fastest growing restoration franchises out of $3,000 and a carpet cleaning machine.

Here’s what it means to be a 911 Restoration franchise owner:

Innovative Lead Generation System

“Our goal is to see franchisees succeed,” Idan says. “Through our multi-million-dollar marketing platform, we have grown one-man operations into major regional restoration companies.”

911 Restoration corporate keeps the lead generation growing through the efforts of their expert in-house marketing team. This team has been solely dedicated to the restoration industry from the beginning, developing and optimizing a powerful lead generation structure that generates thousands of calls on a monthly basis. To help franchisees maximize time, the 24/7 customer service team records initial call information and transfers emergencies to branch managers so their crews never miss a lead.

Fresh Start Reputation

Shpizear has been deliberate about establishing a meaningful company culture. As he says, “Culture is where it starts.” Every team member and franchisee stands united behind the Fresh Start philosophy—the belief that every disaster is an opportunity to rebuild better

• Ranked #2 Top Restoration Franchise on Entrepreneur’s 2020 Franchise 500

• Ranked #44 on Entrepreneur’s 2020 Franchise 500

• Ranked #55 on Entrepreneur’s 2020 Top Growth Franchises List About 911 Restoration

911 Restoration Fast Facts

� Business growth via advanced lead generation system & national clients

� Sold 200+ territories

� Proven franchise concept with high profit margins

� Strong brand recognition

� Low investment with high return

than before. Armed with this attitude, franchises and corporate work together to help customers turn crises into new beginnings. Now known from coast-to-coast as the “Fresh Start Company,” 911 Restoration has become the contractor property owners associate with compassionate, client-centered service.

National Accounts

Through the combined powers of a strong marketing system, a unified team, and a trustworthy reputation, 911 Restoration has secured several national accounts. Shpizear reports that the company’s continual growth in this area contributes to the fast success of franchisees. “We actively seek entrepreneurs who have a growth mindset and a desire to make a positive impact,” he says. “When they apply those qualities to the boost they get from our lead generation and national accounts, success comes quickly.”

Adaptability

The recession-proof nature of the disaster restoration industry already offers security for 911 Restoration franchisees. What makes this particular company unique is corporate’s immediate response to unexpected challenges. “We move quickly,” Shpizear says. “When the pandemic hit, we added a sanitization and disinfection focus in our marketing and gave our franchises the support they needed to adjust. When Texas was struck by winter storms, we ensured our franchisees were fully equipped to be the Fresh Start for their devastated communities.”

SIDE HUSTLE

YOUR STARTS NOW

The pandemic triggered a surge of interest in side hustles. Why? Because they’re a good way to test new ideas, earn some extra income, and maybe even blossom into a new full-time career that you’re in control of. But building a lucrative side hustle is no easy feat—so on the following pages, we break down three steps to identify your idea and get it off the ground.

by KIM PERELL, creator of Entrepreneur’s Side Hustle Accelerator

PART 1 FIND YOUR IDEA

Where to begin? Start with this three-step plan.

Aor a hopeful founder? As I’ve coached many entrepreneurs, I’ve found that everyone tends to fit into one of these categories. Shaky dreamers have an idea but not the confidence to move forward. Idea machines have so many ideas they struggle to pick one. Hopeful founders have the motivation but no idea where to start. Each category comes with its own challenges, but the solutions are largely the same: To start a great side hustle, you need to approach it with focus, reality, self-awareness, and a problem-solving mindset. Here are three steps to choosing the right idea.

Get to know yourself. Think about what you’re interested in, what you’re passionate about, and what your strengths are. Brainstorm areas that allow you to leverage those talents and interests. Side hustler Marianne Murphy is a great example of this. She wanted to be an entrepreneur but didn’t know where

of what she knew: She has a marketing background, a full-time job at a hospital, and five sons. That gave her a starting point—a kids’ health product that required great branding.

STEP 2

Identify a problem. The most successful entrepreneurs look for problems

they can solve, not businesses they can start. Once you’ve identified a problem, explore it! Do not collect 10 different ideas and dawdle on which to pursue. Pick one, then talk to people who have the same problem to see if they’d pay for your solution.

That’s what Murphy did. She knew that kids hate brushing their teeth and wanted to see if she could build a better experience— so she wrote a book and later created a toothbrush that plays music to accompany it. It worked for her children, so she talked to friends, family, and preschool moms to confirm they had the same struggles and got them to try her musical toothbrush.

STEP 3

Iterate; don’t innovate. So many people think their side hustle idea has to be a totally unique stroke of genius in order to work… but that’s not true. It’s easier (and less expensive!) to put your own twist on an existing idea.

That was Murphy’s path. She started selling her book and brush under the name The Twin Tooth Fairies. Did it reinvent dental hygiene? No. But it offered something fresh. It’s now sold online at Walmart and Amazon, earning her nice additional income per month.

Side hustle ideas can come from just about anywhere. Look within yourself, out in the world, and in the current market to find a need you can fill, and you just might go from a hopeful founder to a successful one.

HOW THESE SIDE HUSTLERS DID IT

FIND THE OPPORTUNITY IN THE EVERYDAY

“On Valentine’s Day in 2016, my husband of 27 years asked if I’d like a ‘special cup of coffee’ from Dunkin’ or Starbucks. It was so cold outside that I didn’t want to burden him, and I said we could just have coffee at home. As he was pouring me a cup, I glanced down at the caramel candies he’d bought for me and my daughters—and I had that aha moment! ‘I have this crazy idea,’ I said. ‘Wouldn’t it be amazing if I could pick up this candy and drop it into my cup of coffee or tea and it would instantly turn it into something special and delicious, and we wouldn’t have to go out and get it?’

Benz USA’s corporate headquarters in 2016 when I noticed a major need for communication and career development among our multicultural and multigenerational workforce. People were coming from so many different backgrounds, and so I developed a plan for an all-inclusive group that would help employees and leaders connect with each other for growth and development. I pitched the idea to the head of diversity and inclusion, got the green light, then got an executive sponsor and hit the ground running.

CREATE EASE FOR OTHERS

“I work for a company that owns the largest Asian grocery store in Jacksonville, Fla., and we work out of an office inside the store. I see customers shopping all the time, and I started thinking about how much easier their lives would be if they had their groceries delivered to them at home. There are already delivery services out there, but they don’t often work with small specialty stores like ours—and that seemed like an opportunity for me.

That was the beginning of what we now call Javamelts. We had no prior experience in food and beverage, but we were so passionate about the idea—and determined to create a better financial future for us and our three girls—that we decided to just go for it. Now, a few years later, we’ve appeared on QVC and we’re growing steadily on Amazon after recently rebranding to all-natural ingredients. It hasn’t been easy, but I’m showing my girls that it’s worth pursuing the things you believe in.”

—CAROLYN BARBARITE, cofounder, Javamelts

The group facilitated oneon-one meetings and group workshops and even hosted a speed networking event, where we achieved the impossible task of getting company leaders in the same room to meet and greet with employees. Then I realized there was a bigger opportunity here— I could do this at other companies, too! So while still at Mercedes-Benz, I developed a curriculum that teaches the art of connecting with others for success professionally, and then launched a coaching service called Connect. Now I use this curriculum to coach, host workshops, and deliver keynotes internationally.”

—MICHELLE ENJOLI BEATO, founder, Connect

The grocery delivery business is complicated, and I wasn’t in a position to do it all myself. I was working full-time while also going to school full-time. When would I be able to run this business? So I approached my boss, the company’s owner, and asked if she’d be my partner and provide 50 percent of the funds needed to launch this. (Plus, we were saving on overhead costs by focusing on delivery.) She said yes. Now we’re running a delivery service for the store, have created partnerships with local restaurants, business owners, and food bloggers, and in the future, hope to expand our service and build an app for our customers.”

—NALAE KIM, cofounder, Shelf To Curb

PART 2 MANAGE FEAR

Don’t stand in your own way. Follow these four steps to embrace your power.

the past few months talking to people about why they hesitate to start something new, and their answer is often the same: They’re afraid.

I can relate. I’ve built and sold multiple businesses, selling my last company for $235 million, and I was afraid every time—of failing, of rejection, of letting people down. I’m still scared. We’re all scared! The key isn’t to eliminate our fears but rather to learn how to face them and move forward. To do that, I created a simple four-step FEAR process:

eel your fear. Fear is a survival instinct. It protects us from danger and allows us to survive. But our minds often don’t know the difference between an existential threat (saber-tooth tiger!) and a nonexistential threat (embarrassment!). So we need to teach it. Research shows that most emotions last only up to 90 seconds. When

yourself that it’s just that: fear. Not danger. And it’s not permanent.

STEP 2

Embrace your fear. Let’s be realistic: You cannot eliminate fear with logic. It’s with you whether you like it or not. So you can either fight it— or embrace it. I say embrace it. Why? First, because fear

is your friend. It is there to protect you, even if it’s sometimes misguided. And second, if you accept that it’ll always be around, then you can stop wasting time trying to “overcome” or “get rid” of it. Shift your time toward understanding, managing, and (most important) sharing it. Things are much scarier on the inside than they are on the outside! Shine a bright light on your fear. Talk with a friend or write it in a journal. Once you identify your fear, you’re that much closer to owning it.

STEP 3

Act on your fear.

Aristotle believed the cure for fear was to act in virtuous ways, including being courageous. I can tell you from personal experience: He’s right. Action creates further action; momentum creates further momentum. If I feared making sales calls, I made a sales call. If I feared stepping on a stage, I did just that. After one step, we start building the confidence and the courage to take the next. If I ever hesitated, I started comparing the risk of action against the risk of no action. What would happen now—or in a year?—if I didn’t take action? Is that outcome worse than the risk associated with jumping in and building the life of my dreams? I’d rather have an ocean of fear than a mountain of regret.

STEP 4

Repeat.

This isn’t a recipe for making fear go away but a process for us to feel our fears and move forward. The secret is to learn how to turn your fears into fuel for success. Little by little, you’ll become stronger than your fears—until they no longer have any power.

HOW THESE SIDE HUSTLERS DID IT

LEARN FROM YOUR FEAR

“When I decided to pursue my true desire and build a new professional path as an executive coach, my anxiety was through the roof. I felt like such an impostor. I thought, Whywouldanyonewantto hiremeasacoach?IfItell peopleIamstartingabusiness,theywilllaughatme. But I realized that the only way forward—the only way to create change—is to allow and accept a part of the growth process that is intensely uncomfortable. Instead of trying to ignore my feelings of fear, I started paying attention to them. When I noticed my own self-sabotaging thoughts, I’d work to replace them with more encouraging ones. I began taking notes of each little success I was creating and giving myself permission to celebrate every one. When I failed (and it still happens today), it allowed me to switch my mindset from ‘I failed’ to ‘I learned something that will help me be better next time.’ I built tolerance for uncomfortable moments— and that’s necessary to become an entrepreneur.”

—SARA KIMELMAN, founder, Reline Coaching

STUDY YOUR OWN SUCCESS

“I’m a graphic designer, an illustrator, and an artist, and I wanted to create a tribute piece to one of my favorite designers, Milton Glaser, who is best known for creating the I Love New York logo. In his career, he created promotional posters for the Catskill Mountains, which are not far from where I live, and it dawned on me that no one was producing modern posters to encourage regional tourism. I created some for the Catskills and started selling them locally and on Etsy. They’ve been a bigger success than I expected, but it’s easy for impostor syndrome to creep in. It’s not even that I’m afraid to put my work out there; my real fear is that I haven’t learned the formula of my success. So now I’m working to understand it, and to learn how to replicate it. After all, I want this to eventually be my hustle, and not just my side hustle. I’m creating new designs, and I’m hoping they will be as much of a success as my Catskills work. But either way, it will be an opportunity to learn something about what customers want, which will make me stronger as I build this brand moving forward.”

—KELLY ANN RAVER, cofounder, Raver Press

DON’T BUILD IN ISOLATION

“I first had the idea for Cure Hydration, a healthy sports drink, when I was training for a triathlon and struggling to recover from my own workouts. I wanted to explore the idea, but I had a full-time job as the director of marketing at Jet.com, and I wasn’t ready to walk away—or jeopardize my position with the company. I was working 50-plus hours a week at my day job and figured I’d need at least 10 weekly hours to develop my side hustle. Instead of doing it in secret, I went to Jet’s legal counsel and asked for permission to work on the idea. She told me there was no issue, as long as I didn’t build the business while I was at the office. With her blessing, I incorporated the business through LegalZoom and got to work at night and on weekends. It gave me the time to validate my idea and see the steps I needed to take to launch the product. When I finally decided to pursue it full-time, I was confident.”

—LAUREN PICASSO, founder and CEO, Cure Hydration

PART 3 START NOW!

How to begin? The answer is so simple that it’ll sound stupid: Make the decision to begin. Everything stems from a commitment to take the first steps. You can make excuses all day, but nearly half of U.S. workers already have a side hustle. They have struggles, too—but they’re pushing ahead. Here are the steps that helped me when I started my first side hustle at my kitchen table more than 20 years ago, when I was broke, inexperienced, and overwhelmed. They can help you, too.

STEP 1

Ask these questions. It’s important to find a side hustle that is a good fit for your skills and lifestyle. Ask yourself:

• How much time can I dedicate to this? Establish this up front and commit to it.

• How much income do I need to make this worthwhile? This isn’t a goal; it’s a reality check. Be realistic about it, write it down, and refer to it often. You’ll want to know if your time is being well-spent.

• What skills do I have that can make this work? Don’t know? Ask a friend what they think you’re good at. Shoot to create a list of three.

STEP 2

Create a structure. Some people hate structure. Maybe they dream of being an entrepreneur so they can escape the structure of their jobs! But I’m telling you:

Structure is freedom. It’s the ground that you build upon. Here’s how to create it:

• Set a goal. I like to make SMART goals—specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely. Each element is critical. You need goals you can work toward and track your progress on. Once you know this, you’ll start to have a sense of what’s required to get there.

• Create a schedule. If you’re committing 10 weekly hours, put them in your calendar and stick to it.

• Find your tools. There are many platforms and services that can help you launch. Take a look at places like Upwork, eBay, Etsy. Start offering your product or service, and learn your marketplace at low risk.

STEP 3

Foster great relationships. When starting anything new, it’s helpful to surround yourself with people who have walked in your shoes—and even bet-

ter if they are a few miles ahead of you! Search for two kinds of people:

• Mentors. A mentor isn’t a job description; you don’t need people who agree to some formalized role. Instead, build a network of mini-mentors—

friends or former colleagues who have expertise and insights.

• Accountability partners. Find someone who’s on a similar path as you, and buddy up. You can help each other stay on track. When you’re your own boss, it’s helpful to keep up with other bosses.

Now comes the most important part: Instead of questioning yourself or waiting for the perfect moment, it’s time to go. Everything that comes next will help you grow.

DOES YOUR CAREER PATH NEED

Leverage your business experience by joining a team of like-minded, former, corporate individuals who are taking control of their destiny. With a Granite Garage Floors® franchise, you can develop your own business with a flexible daily routine and no limitations on income potential. That’s a career makeover in the booming, pandemic-driven home improvement industry that the family will love—that’s Granite Garage Floors.

• R d Ep xy C S v Bu - Affluent Demographic Focus

• Tu k y Sy - Proven Sales & Marketing Strategies + Digital, CRM, & Support

• S p fi d Op - Repeatable Quoting and Installation Process

• L w Ov d M d - High Margins - Average Job Size $3k+

• Id - Solid Business Acumen - Passionate About Customer Service We Upgrade Garage Floors to Look and Last Like Graniteª

OW

HOW THESE SIDE HUSTLERS DID IT

FIND (FREE) MARKETING

“In February 2020, I launched a line of functional chewing gum, made with plant-based vitamins and adaptogens. I don’t come from a family of entrepreneurs, so I didn’t know what being an entrepreneur should look like. I come from an immigrant family, and I’m 40—so my parents were confused about why I would take focus off a well-paying career to

sell chewing gum, and I felt too old to be a carefree entrepreneur. But I developed the product and had to think smart to get it out in the world. I did some Instagram stalking and found a few people with a solid following who I thought might be interested in Mighty Gum. I cold-emailed them and asked if I could send them some product. They said yes, and when they mentioned it on their social channels, the surge we saw in demand was truly surreal. I’d always underestimated the power of partnering with the right influencer, but it was key to our launch.”

—MATHEW THALAKOTUR, founder, Mighty Gum

DRAW FROM EXPERIENCE

“Just before I graduated college, a part-time consulting gig made me aware of the completely underserved market of tattoo aftercare. I wanted to create a brand to fill that gap, and I brought the idea to my partner, Selom Agbitor. We’d worked together before, drop-shipping women’s swimsuits out of my apartment, and had learned a lot about operating without the hassle of inventory

and creating reliable branding and customer service. Now we felt equipped to take on a bigger project. We formulated our product, spent $600 on ad spend, and recruited our neighbors to help us with fulfillment as orders started to roll in. Our goal was to grow fast enough that we could afford to hire manufacturers by the time we graduated—we’d both accepted full-time jobs, after all. That initial $600 proved money well-spent—it got us off the ground, and from there, orders were reliable enough that we could continue funding increasingly large ingredient purchases and boosting ad spend.”

—OLIVER ZAK, cofounder, Mad Rabbit Tattoo

TEST YOUR PRODUCT