2 minute read

How to end chronic homelessness in DC, according to new report

from 04.05.2023

ANNEMARIE CUCCIA Staff Reporter

D.C. could end chronic homelessness by 2030 with over $770 million in new investments, according to a new report by the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) — if the city begins funding programs this year.

Advertisement

An annual survey conducted in 2022 revealed around 1,270 people were experiencing chronic homelessness in D.C., though that number is widely recognized as an undercount. People who are “chronically homeless,” according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition, must have been documented as being homeless for over a year or multiple times over three years, and have a disabling condition that makes it difficult to work full-time.

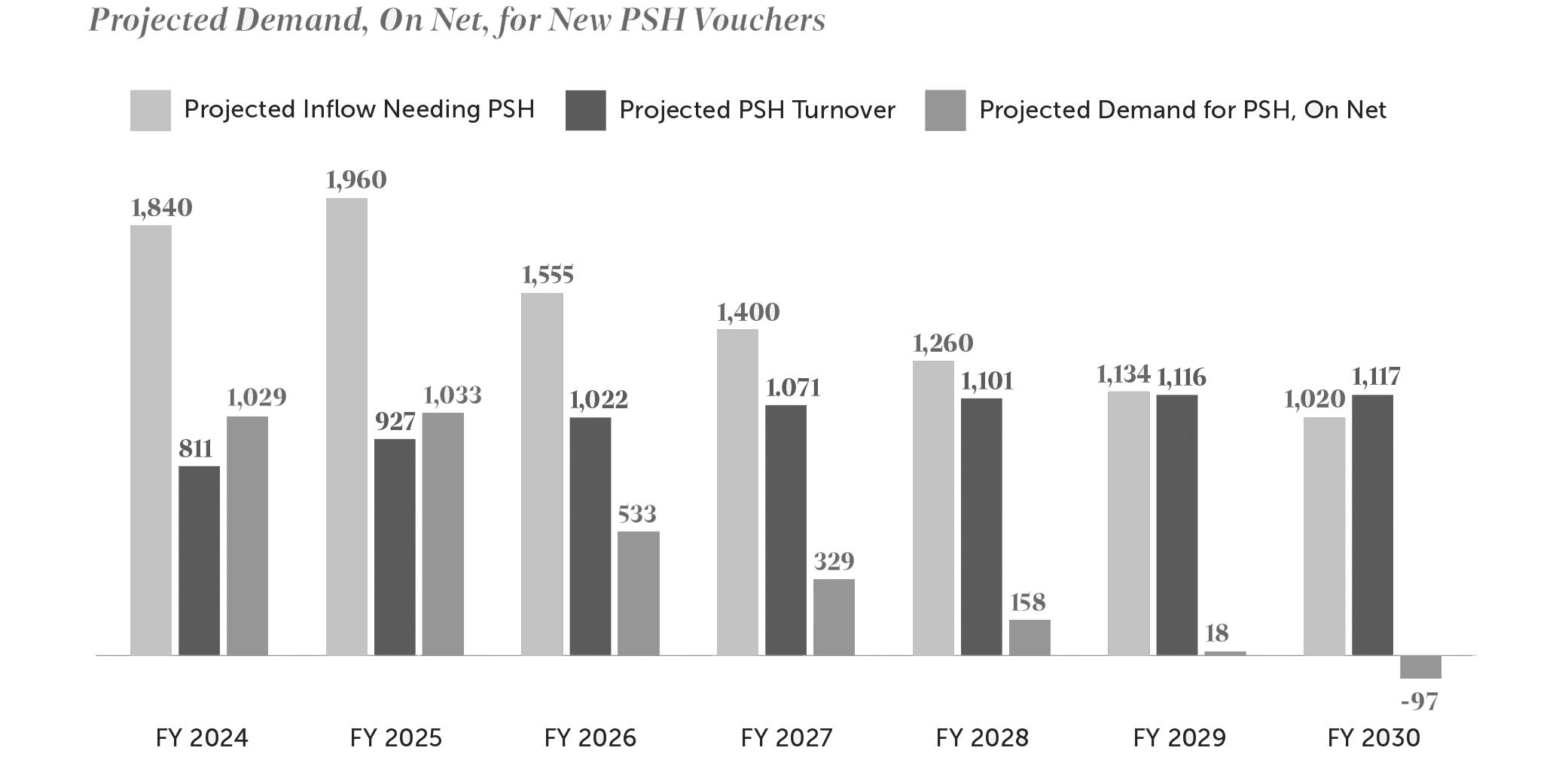

Since people continue to enter homelessness, ending it requires providing housing to both people who are currently homeless, and people who become homeless in the future. Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH), a program that provides people with a housing subsidy and supportive services, is generally seen as the best way to do this. If the city invests more in PSH vouchers over the next six years, the report predicts D.C. will have enough housing vouchers for everyone experiencing chronic homelessness by 2030.

“It’s urgent, because people literally die because they are chronically homeless,” Kate Coventry, the report’s author and deputy director of legislative strategy for DCFPI said at an event promoting the report. “And they die from diseases the rest of us manage and prevent because we’re in housing.”

The $770 million price tag includes in addition to the cost of 3,100 additional PSH vouchers, stipends to hire case managers, and the construction of new PSH-designated apartments. While people using PSH vouchers may rent anywhere in the city, they often struggle to find landlords who accept them, though this practice is illegal.

Coventry based the prediction on two assumptions: one, as D.C. invests in prevention methods, the number of people entering homelessness each year from now until 2030 will decrease, and two, that the turnover rate for PSH vouchers, due to people leaving the program or dying, will remain steady. The $770 million does not include land costs for the new apartment buildings.

For fiscal year 2024, DCFPI estimates D.C. would need to spend $153 million on the initiative, a far cry from the mayor’s current proposed budget, which includes no new vouchers.

The report also includes suggestions for improving the administration of PSH vouchers. Today, applicants can wait up to nine months from when they are first identified as eligible for a housing voucher to when they finally use one to move into housing. If the process continued at the current pace, D.C. might not be able to administer all the proposed vouchers as suggested.

One of the reasons for the slow administration of vouchers is a lack of case managers. To accelerate the process, the report suggests removing social work exam requirements for these positions and providing PSH providers with a hiring stipend.

In addition, the report suggests that the city could also give prospective PSH users free transportation while they're searching for an apartment, and pay security deposits quickly to help people secure a unit. To kickstart other much-needed fixes, the report suggests establishing a 100-day voucher boot camp for agencies who administer vouchers.

The report recommends improvements to the PSH program based on feedback from people who have experienced homelessness. Some recommendations aim to improve the experience of voucher holders overall, by retraining case managers to provide consistent services — panelists at the release event said that while good case managers are integral to the program, the quality varies widely. The city should also gather input from people who live in site-based PSH programs, which garner skepticism due to their resemblance to shelters.

Finally, the report argues the city should examine ways to give more extensive services to groups who need them, such as expanding the Department of Behavioral Health’s oftenfull housing programs and services for people with mental health challenges and exploring opportunities for seniors to use vouchers at nursing homes and assisted living facilities.