5 minute read

What’s the best way to protect the environment?

from 04.05.2023

WILL SCHICK Editor-in-Chief

Trey Sherard is intimately familiar with the cascading effects of environmental pollution.

Advertisement

For years, a chemical manufacturer called Chemours Co. had been dumping a substance known as “Gen X” into the Cape Fear River near Sherard’s hometown in Wilmington, N.C., a stateappointed investigation revealed. The chemical agent is known to cause cancer and affect the “development of offspring” and affect a person’s fertility, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. It contaminated the drinking water, endangering the health of hundreds and thousands of people, such as Sherard’s sisters and close friends who live in the region, making it the subject of numerous state-backed enforcement actions and reviews.

People across the country have shared similar stories about chemical contaminants seeping into their communities. In the past decade, a Bloomberg Law report revealed that thousands of people have filed lawsuits against companies for introducing dozens of known harmful agents.

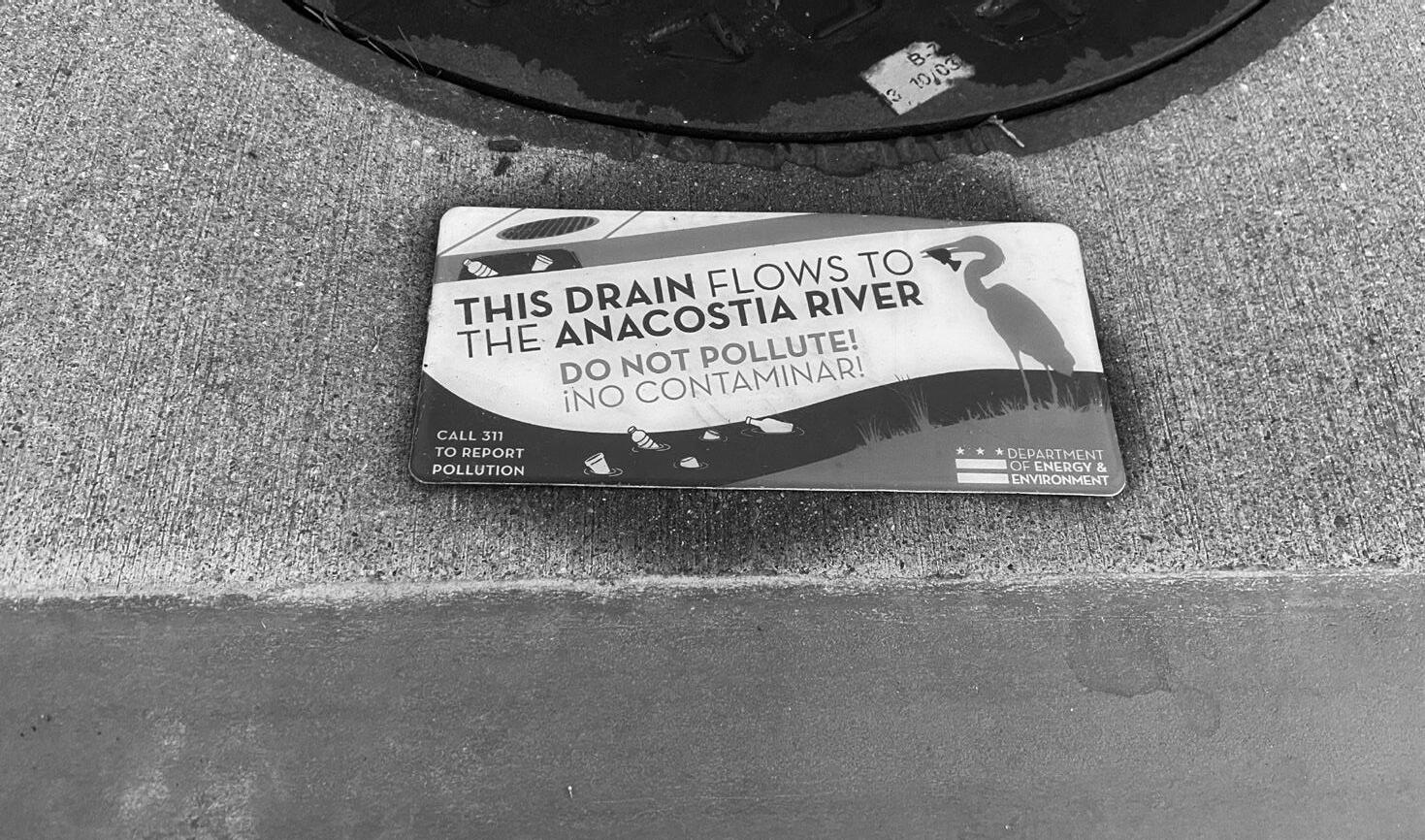

With a degree in marine biology, Sherard has spent the past 11 years combating threats to a waterway located a few hundred miles north of his hometown: the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C. where he serves as its riverkeeper. During this time, he learned a great deal about other harmful substances known as PCBs and PFAS and other chemicals found in high concentrations in the river basin.

This past fall, Sherard received a phone call from D.C.’s Office of the Attorney General that alerted him to a new action it was taking against a company it believed to be the source of another harmful contaminant called “chlordane.”

It had just filed a lawsuit against a company called Velsicol Chemical Ltd., which for years manufactured and sold a household pesticide containing the chemical compound shown in some studies to cause cancer. According to the lawsuit, the product was used widely in households throughout the region to treat termite infestations. The area surrounding D.C. is considered a “moderate to heavy” termite infestation zone, according to a 2021 map produced by the U.S. Dept. of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.

Since river systems overlap vertically and horizontally with the environment surrounding them, toxins that find their way into the river can also get into wildlife and the people who consume them, according to Sherard. Over the years, the Anacostia River has seen many toxic contaminants enter its waters. A recent joint water quality study presented by the D.C. Department of Energy and Environment, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Maryland state government found “toxic impairments” of arsenic, copper, zinc, DDT and chlordane in the Anacostia River, which has an outsized impact on the region’s predominately African-American subsistence fishers.

In announcing the local lawsuit, then-Attorney General Karl Racine alleged that Velsicol Chemical knew the harmful effects of its product yet marketed and sold it anyway and caused widespread damage in some of the city’s most vulnerable communities. The filing mirrors similar action taken by authorities in states across the country, including Tennessee and Maryland.

Sherard’s excitement with the new lawsuit, however, was tempered. For him, the lawsuit is a symptom of a much bigger problem: lax U.S. environmental regulations.

A bigger issue: thinking beyond the substance

Under the Toxic Substances Control Act, the U.S. government follows a simple process for regulating chemicals. It forbids the manufacture and distribution of known harmful agents. While this may sound like a practical strategy – banning the production and sale of chemicals known to cause harm – it has one critical downside. Some environmental researchers see it as a less effective means of preventing the spread of never before seen harmful chemicals.

According to Sherard, under this formula, by the time substances such as chlordane are discovered to cause harm, it can feel as though the damage is already done.

“It very much favors chemical developers and manufacturers. They’ve got all these other cousins, so that when they finally get enough attention to be regulated, they introduce the formula to the next one,” he said.

Dr. Rashad Ahmed, an environmental economist at Trinity College, agrees that environmental regulations tend to fall short.

“Unfortunately, in many cases, the science and innovation is ahead of the regulations. So materials are invented, products are being used, and then oops, years afterward, [people say] ‘Oh, you know what? That was bad,’” she said.

For example, for many years, the chemical DDT was widely used as an insecticide in the United States due to its costeffectiveness and long-lasting effects on the environment. However, it was not until years later that regulators realized the chemical’s permanence was an environmental hazard.

From Ahmed’s point of view, the problem has less to do with regulations and more to do with economics. In a free market, there’s a phenomenon that is known as an “externality.” These occur when someone incurs a cost or obtains a benefit from a shared resource without paying for it, such as when a company pollutes a river without paying for it. It is the basis for most environmental pollution problems in today’s society, she said.

Even as regulators can try and hold bad actors responsible, it takes time to determine the exact scope of damage they have

caused, according to Ahmed..

In search of solutions: Do they do it better in Europe?

Across the Atlantic, however, the European Union follows an entirely different approach to managing chemical risks with a policy known as Registration Evaluation Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals, or REACH. This policy requires producers to first present evidence that the chemicals are safe before they can be manufactured and distributed.

A government chemist – not authorized to speak to the media– said that comparing both U.S. and European approaches directly to each other can be complicated. There are challenges with trying to regulate everything, he said. And even with a proactive approach such as the one used in Europe, there are some cases where there are no alternatives and companies have no choice but to use harmful chemicals.

One such example is strontium chromate, an anti-corrosion substance used on aircraft that is rated as highly toxic by both the European Union’s REACH policy and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Even though the substance is rated as harmful by both bodies, they permit it since there is no other viable substitute, according to the chemist.

Ahmed agrees that every regulatory approach has its own faults since neither can fully prevent the spread of harmful products. And some proactive regulations could create another set of unintended problems.

As an example, Ahmed said U.S. policymakers had attempted to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from cars by implementing new fuel efficiency standards for cars, known as Corporate Average Fuel Economy or CAFE.

Manufacturers can manipulate this structure by selling even more vehicles with fuel-efficient standards, that may end up having the opposite effect.

Consumers have a voice

Although regulations tend to fall behind innovation, Ahmed said that consumers still have a large sway with companies that bring products to the market. In some places where consumers have been vocal, companies have reacted to the interests of consumers who have shown more active interest in purchasing green products.

However, this also has its own complications Ahmed pointed out that many companies may apply “green-washing” marketing techniques intended to deceive consumers into believing that their products are environmentally friendly when they are not.

While Ahmed does not have a simple solution for this issue, she believes it is important for everyone to recognize they have a role in this.

“When you do this kind of analysis and try to figure out what we need to do, don’t forget the kind of institutional environment we have: the corporations that are trying to maximize profit, all these kinds of things do have an influence, but evidence shows that as consumers, we also have a voice in the story.”