13 minute read

'They Were Bombed by Americans - 20 Years Before Pearl Harbor' Uncovering the Truths of the Tulsa Race Massacre

Archaeologist Dr. Alicia Odewale’s great-grandmother, Polly Curtis, is among the missing people from the Tulsa Race Massacre of May 31-June 1, 1921. Although the official death count was 36 people, historians now say the real number could be over 300. Odewale surmises Curtis could be in any one of 35 previously unknown and unmarked potential mass grave sites she has identified.

“The hardest day in the field was when we discovered a child’s coffin. Families were destroyed, children murdered.” Odewale has not gone back to the site since that day in 2021. She spoke in a January 29 National Geographic Live presentation on the Black neighborhood of Greenwood in Tulsa, OK, and its century of resilience, at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago.

Survivor Eddie Faye Gates was a child at the time and said that his mother saw four men with torches come into their home and set the curtains on fire. They also killed his little bulldog. The family hid in the attic but heard bullets raining down on their rooftop – probably from an airplane.

“Some folks you never heard of anymore,” Gates said in a filmed documentary in the 1990s. “You never forget that.”

Ernestine Gibbs said in the same film that not a building was standing in Greenwood, the 40-block square area of Tulsa that Booker T. Washington had christened “Negro Wall Street.” The mob went block by block, Gibbs said, burning buildings to the ground.

By the time their violence was over, 198 businesses had been destroyed including five hotels, two theaters, 41 grocery stores, six clothing stores, 15 barbershops, 10 laundries, 17 doctors’ offices, two schools, seven churches, a library and a hospital. Destroyed businesses included the 54-room luxury Stradford Hotel – largest in Oklahoma – owned by J.B. Stradford, a graduate of Oberlin College and Indiana University Law School; and the 750-seat Dreamland Theater that showed silent movies.

According to the Red Cross, 1,256 buildings burned and 314 homes were looted, 10,000 people were made homeless, 531 needed surgical care or first aid, and 183 were hospitalized.

The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is one of the nation’s worst acts of racial terror, said Odewale, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Tulsa. But while most people think archaeology is simply the study of ancient pottery fragments, Odewale said the discipline is helping her to define the boundaries of this incident of violence. Black Tulsans no longer call it the “Tulsa Race Riot,” she said, but an attack, a massacre, a pogrom. In fact, “riot” was the term used by whites so that insurance would not pay on claims.

Odewale’s current research project, “Mapping Historical Trauma in Tulsa from 1921-2021,” is re-examining historical and archaeological evidence of the period – from personal survivor stories to old Sanborn maps that tell where businesses were— focusing not on the attack itself, but instead on illuminating a new perspective on the impact of racism and racial violence in America, through the lens of a community that continues to survive against all odds.

“The people calling the shots in 1921 hid the truth, and spun a story about people rioting for no reason and burning down the community,” Odewale told her Chicago audience. “They vindicated the arsonists and banned the story from textbooks. A lot of people worked really hard to keep this out of the public eye and away from people like you. Our job is to make sure it never happens again.”

Indeed, photos of the damage appear to be uncharacteristically deteriorating themselves, from negatives that seem to have melted in the heat. Some photos have been restored, however, and a large collection is in the National Archives.

“The near-total erasure of this horrific event from historical narratives covering this period reveals how politically motivated historical accounts can be,” noted National Archives blogger Bob Nowatzki at the centennial of the massacre. “Fortunately, there are records in the National Archives,...that can help us keep the memory of this event and its survivors alive.”

In Tulsa of 1921, the Ku Klux Klan ran everything in the city, Odewale said. Its roster included everyone from carpenters to oil tycoons, school principals to the city treasurer, the deputy sheriff, the chief of police – and the mayor. After the massacre, KKK membership grew so that it opened chapters for both children and women.

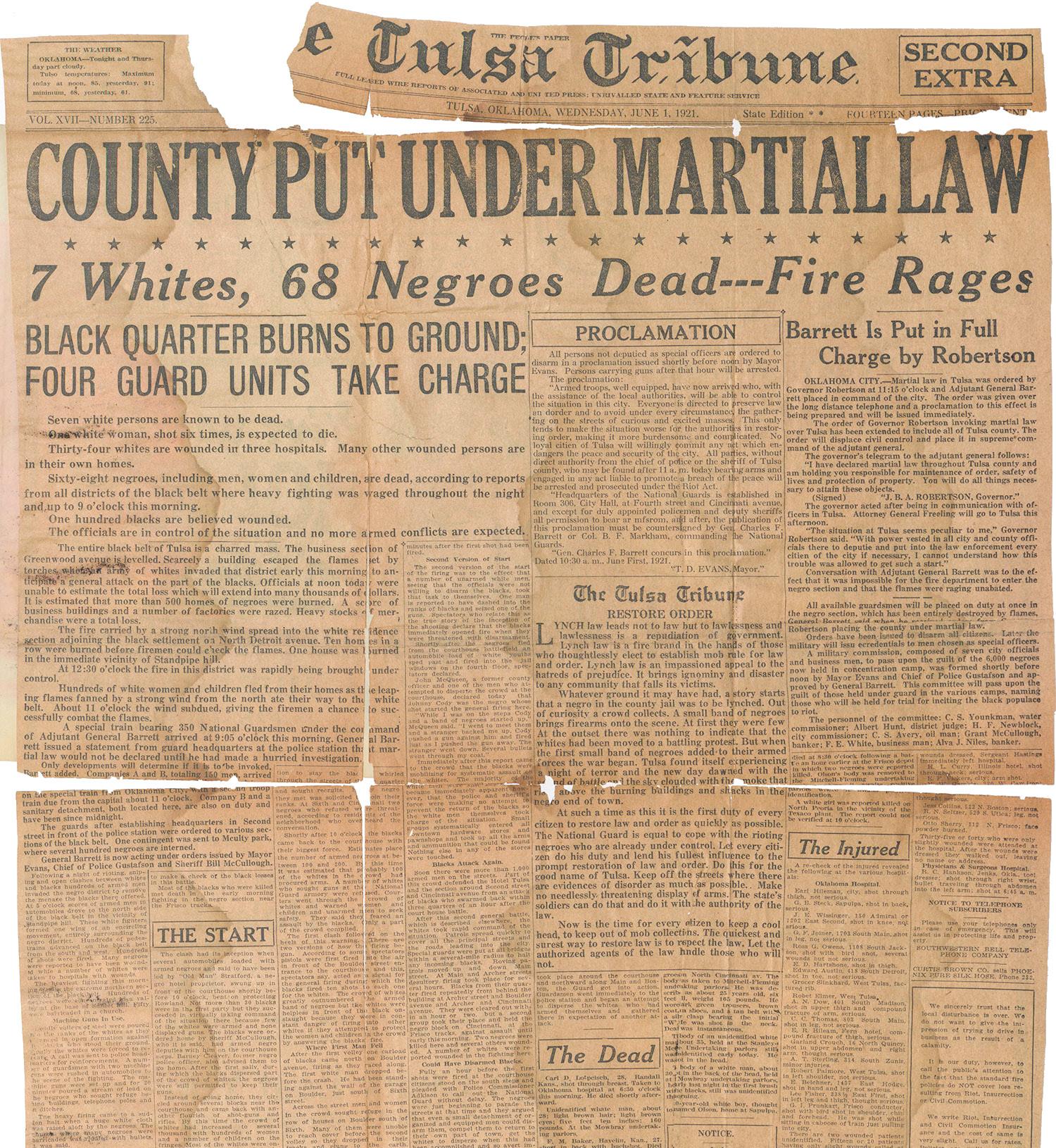

"Front Page of the Tulsa Tribune, June 1, 1921": The Tulsa Tribune was one of the local newspapers that reported the events of May 31 and June 1, 1921. This issue describes a scene from the massacre: “The machine guns were set up and for 20 minutes poured a stream of lead on the negroes who sought refuge behind buildings, telephone poles, and in ditches.”

National Archives photos

The Greenwood District, circa 1917

Mary E. Jones Parrish Collection, Oklahoma Historical Society photo

People didn’t talk about the story for fear they would be killed. However, most people heard about it in high school, or in Odewale’s case, grade school. Don Ross learned about it in high school in the 1950s and was incredulous. His teacher was W.D. Williams, whose parents, John and Lula Williams, had owned the Dreamland Theatre, as well as a garage, a confectionery, and a doughnut shop.

“Teachers are important!” Odewale said, to applause from the Auditorium audience.

Because of Williams, Ross gathered survivor stories and, in the 1960s and 70s, became one of the first journalists to write about the Tulsa Race Massacre. Later, as a member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives, he also created the Tulsa Riot Commission. Because of his actions, Oklahoma became the first state in the U.S. to take down official Confederate flags.

Greenwood stands out as a foremost national incident of racial terror because the entire neighborhood that was destroyed was comparable to Beale Street in Memphis or State Street in Chicago, according to Oklahomapreservation.org. The Brookings Institution went even farther in a blog during the centennial: “Greenwood was likely the richest Black community in the United States, and racist neighboring communities perceived its economic flourishing as an existential threat.”

Ron Carter, who chairs Black Wall Street Chicago, was at Odewale’s presentation, but he questions the Brookings Institution designation of Greenwood as the richest Black community of the 1920s. Chicago’s Black State Street extended from 18th to 47th Streets: larger than Greenwood, but perhaps only 50 percent of its businesses Black-owned. Moreover, the financial impact of numbers running (the policy game that became the Illinois lottery) has not been adequately taken into account in Chicago, because it was both illegal and underground, Carter said.

Part of Tulsa’s prosperity had to do with the state of Oklahoma, which had been Native American territory. Settlement there came with citizenship, freedom and acreage, Odewale said. In the late 19th century, Black people pooled their resources to create all-Black towns in Oklahoma, with their own schools and churches separate from the Jim Crow South, in order to be truly free.

Greenwood had been established in 1906 by O.W. Gurley, a former teacher and postal worker born in Alabama and raised in Arkansas. Believing that the South would never give him any opportunities, he moved first to Perry, OK, and then to Tulsa, where he purchased 40 acres on its North Side and sold lots to other residents and entrepreneurs.

But as Black towns grew, so did the white “sundown” towns where Blacks could not travel after dark. Greenwood was surrounded by six sundown towns, including Tulsa.

1921, according to the Oklahoma Economist blog by the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank, Tulsa had gone through two oil booms to become the center of the petroleum industry and an aviation nexus. Its population had grown from 1,000 in 1900 to 100,000 in 1920; Blacks comprised 10 percent of the population. They may have worked for newly rich white oil barons, but because of the segregated South, they spent all their money in Greenwood.

People running from rubble in the Greenwood District, June 1, 1921

National Archives photos

Man being detained during the Massacre

National Archives photos

The origins of the riot were in downtown Tulsa. African American shoeshiner Dick Rowland, 19 years old, was on the way to the only restroom Blacks were allowed to use downtown, on the Drexel Building’s top floor. Rowland got on an elevator run by Sarah Page, who was 17 and white. What happened next is unclear. The elevator came to an uneven stop at the top floor. He may have fallen onto Page, possibly grabbed her arm and tore her blouse. Or, he stepped on her shoe. She screamed. Rowland ran, which prompted a local merchant to call police.

Later, Page urged that all charges against Rowland be dropped, so people believed they had a relationship, which was illegal at the time, Odewale said.

By midday, Rowland was brought to the Tulsa County Courthouse. Inflamed by a white Tulsa newspaper headline, the police received a call at 4 p.m. from a lynch mob that demanded Rowland be handed over. Police moved him to the top floor of the building.

Simultaneously, up to 40 Black men, many of them World War I veterans with arms, also went to the courthouse to protect Rowland. They were refused, and returned to Greenwood.

At 10 p.m., however, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society, a false rumor hit Greenwood that whites had stormed the courthouse. This time, a larger contingent, perhaps 75 African Americans, returned to the courthouse and were again turned down. But as they were leaving, a white tried to disarm a Black man. A shot was fired and the riot began.

“Over the next six hours Tulsa was plunged into chaos as angry whites, frustrated over the failed lynching, began to vent their rage at African Americans in general.” An unarmed African American man was murdered in a downtown movie theater and carloads of whites began drive-by shootings in Black residential neighborhoods. They set fires at the edge of Greenwood, and as they sat in the all-white cafes, they planned for a dawn invasion. Then, they began looting homes and businesses, before setting them on fire.

Several eyewitnesses reported seeing planes fly over Greenwood, with shots fired and explosives dropped from the air. “They were bombed by Americans – 20 years before Pearl Harbor,” Odewale said.

By the time the National Guard arrived at 9:15 a.m. June 1, most of Greenwood was burning.

“From a 10-room and basement modern brick home, I am now living in what was my coal barn,” C.L. Netherland was quoted in a Harvard blog on the centennial of the massacre. “From a five-chair white enamel barber shop, four baths, electric clippers, electric fan, two lavatories and shampoo stands, four workmen, double-marble shine stand, a porter and income of over $500 or $600 per month, to a razor, strop and folding chair on the sidewalk.”

A photograph of a car filled with men holding rifles is labeled "Searching for Negroes, June 1, 1921." It appears that the photograph has been melted or damaged.

National Archives photo

Displaced Greenwood residents gather at the entrance to the Tulsa Fairgrounds, which became a makeshift refugee camp.

National Archives photo

For the first time outside of a natural disaster, the Red Cross was mobilized to provide relief, from June through December 1921. The Red Cross also supplied half a million feet of lumber, but no extra labor to help residents rebuild. Residents reinforced tents from the Red Cross with side panels or built wood frame shacks with their own hands.

Ten thousand were homeless – roughly Greenwood’s entire population. Several thousand wound up at the Tulsa Convention center, Odewale said. They were given ID cards and were not allowed to leave unless a white Tulsan vouched for them.

Furthermore, the white mayor of Tulsa sent a message to the Tulsa City Commission two weeks afterward in which Blacks were blamed for the violence, according to the National Archives’ Rediscoveringblackhistory.org. Mayor T.D. Evans also proposed displacing Greenwood residents and destroying businesses by building a railroad station and an industrial park there. The proposal was blocked by prominent Greenwood attorney, Buck Colbert Franklin, father of the historian John Hope Franklin.

Greenwood had rebuilt itself by 1925, however, when it hosted the national conference of the Negro Business League, and it was even more prosperous in the 1940s, with 242 businesses.

But from the 1960s to the 1980s, urban renewal by white city planners was again Greenwood’s undoing, according to the Brookings Institution. As detailed in a Human Rights Watch 2020 report that recommended reparations, these policies included eminent domain, rezoning and construction of the Crosstown Highway, I-244, right through the Greenwood business district. This led to displacement and plunging property values, while redlining prevented the injection of new capital into the community. “What I call the second attack on Greenwood. The first was by fire, the second by design,” Odewale said.

Greenwood is still denied a listing on the National Register of Historic Places, she noted, because it was rebuilt with different materials. As a result, it cannot receive tax credits and other investments.

Carter, of Chicago’s Black Wall Street, visited Tulsa in 2011 and noted the historical monuments, but he’s skeptical of commercial development, especially post-COVID. “Is there a future? The only ethnic communities that are pretty strong on the South Side of Chicago are 26th Street/Little Village and Chinatown,” he said.

The Oklahoma Economist blog took a nuanced view of commercial development at the massacre’s centennial. “While the Black Wall Street of the past cannot be recreated as it was and the current economic challenges of the Greenwood area are clear, many local Tulsans are working to rekindle the entrepreneurial spirit and economic vibrancy of Black Wall Street.” Just three of many organizations are Black Tech Street, Tulsa Economic Development Corp. and the Black Wall Street Chamber of Commerce. And John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park was dedicated in 2018, in honor of the University of Chicago professor who defined African American history.

The group is also working on a school curriculum that is both archaeologist- and descendant-led, Odewale said, and she is hoping to reconnect families through the Greenwood Diaspora Project. There were perhaps two descendants who identified themselves publicly at her Auditorium Theatre presentation.

“Mapping Historical Trauma in Tulsa from 19212021,” launched by Odewale and another native Tulsan, Dr. Peter Van Valkenburgh of Brown University, will connect the past and present through a Web GIS portal, embedded with historical maps, photos, census data, and more, that show the shifting shape of Greenwood. Primary data from all over the nation will be available to anyone with internet, she wrote in the Society of Black Archaelogists newsletter in 2020, “which places the tools of analysis primarily in the hands of community members, descendants, students and educators.”

Users will be able to click on the former location of the 54-room Stradford Hotel, for example, and interact with all the maps and photos related to it.

Odewale herself knows the location of an ancestor’s grocery store in 1921, and she has survivor accounts of potential mass grave sites.

“We will keep searching until we bring them all home,” she said at her Chicago presentation.

by Suzanne Hanney & Emma Murphy